Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is one of the top global public health and development threat.1 It is estimated that bacterial resistance to the different classes of the antibiotics was directly responsible for 1.27 million global deaths.2 Unfortunately, with the wide spread of antibiotic use, the emergence of multidrug resistant pathogens as well as reduced the efficacy of many potent antibiotics were witnessed.3 Further the medical care cost was greatly increased due to the overuse of antibiotics and treating the infections caused by the resistant bacteria.4 The worldwide problem of antibiotic resistance made the need for the antibiotic stewardship evident.5 Hospital associated infections caused by the antibiotic resistant bacteria were estimated to cost billions of dollars each year.6 Fluoroquinolone antibiotics class are bactericidal medications.7 The mechanism of action of fluoroquinolone antibiotics is through the inhibition of DNA gyrase leading to the block of the bacterial DNA synthesis.8 This class of antibiotics shows potent activity against the infectious bacterial agents which cause urinary tract infections (UTIs) and lower respiratory tract infections inside hospitals globally.9 Non genetic basis of the bacterial resistance to fluoroquinolone antibiotics include that bacteria can be walled off within an abscess cavity 10 or be in a resting state (non-growing).11 Bacteria under certain circumstances can survive as protoblasts that are insensitive to the cell wall-active antibiotics.12 The presence of foreign bodies such as catheterization and artificial valves makes successful antibiotic treatment more difficult.13

Genetic basis of bacterial resistance include either chromosome mediated resistance,14 transponson mediated resistance15 or plasmid mediated resistance.16 Fluoroquinolone antibiotics resistance occur due to either modification of the DNA gyrase in pathogen 17or the export of the antibiotic from from the infectious agent through multidrug resistant pump.18 The aim of the present study was to detect the genes responsible for the bacterial resistance to some selected fluoroquinolone antibiotics in different hospitals in Egypt as well as the identification of the causative resistant organisms using the third generation high throughput sequencing technique.

Patients and Methods

Priority was given in the current study to all pertinent institutional, national, and international regulations dealing with the use and care of persons. All study procedures involving human participants have been approved by Cairo University's Ethical Committee for Human Handling (ECHCU), located in the Faculty of Pharmacy (permission number FKZ460/2023). The research aimed to reduce the pain experienced by human subjects. With informed consent, the use of human subjects or samples in studies was authorized. The World Medical Association's rule of ethics for human research, the Declaration of Helsinki, was followed in the conduct of the current investigation.

Screening experimental research work.

The study was consummated at Cairo University's pharmacy faculty in Egypt between February 2023 and November 2024.

Two hundred urine samples from adult male and female patients with urinary tract infections (30–56 years old, weighing approximately 70 kg) were randomly collected in sterile urine bags. Additionally, 200 nasal respiratory swabs from patients infected with lower respiratory tract infections (18–52 years old, weighing approximately 70 kg) were randomly collected from hospitals in various locations in Egypt (Menia, Sohag, Cairo, Sharkia, and Behira). Before being processed, the obtained samples were kept in sterile containers at 4 ̊°C.

All chemicals were purchased from Algomhuria chemical company, Egypt. All chemical reagents used in the present study were of analytical grade.

Table 1.

List of instruments.

Table 1.

List of instruments.

| Instrument |

Model and manufacturer |

| Autoclaves |

Tomy, japan |

| Aerobic incubator |

Sanyo, Japan |

| Digital balance |

Mettler Toledo, Switzerland |

| Oven |

Binder, Germany |

| Deep freezer -80 ̊C |

Artikel, USA |

| Refrigerator 5 |

Whirlpool, UK |

| PH meter electrode |

Mettler-toledo, UK |

| Deep freezer -20 ̊C |

Whirlpool, UK |

| Gyrator shaker |

Corning gyrator shaker, Japan |

| 190-1100 nm Ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer |

UV1600PC, China |

| Light( optical) microscope |

Amscope 120X-1200X, China |

This was performed using the culture on nutrient agar plate19 at 37 ̊C, pH 7.4 and incubation for 24 hours. Afterwards, subculturing on blood agar,20 Cetrimide agar21 and Mackonkey agar22 plates was done at pH 7.3, 35 ̊C and incubation lasted 18 hours. Finally the primary identification of the causative agents was achieved using Gram staining as well as biochemical reactions.

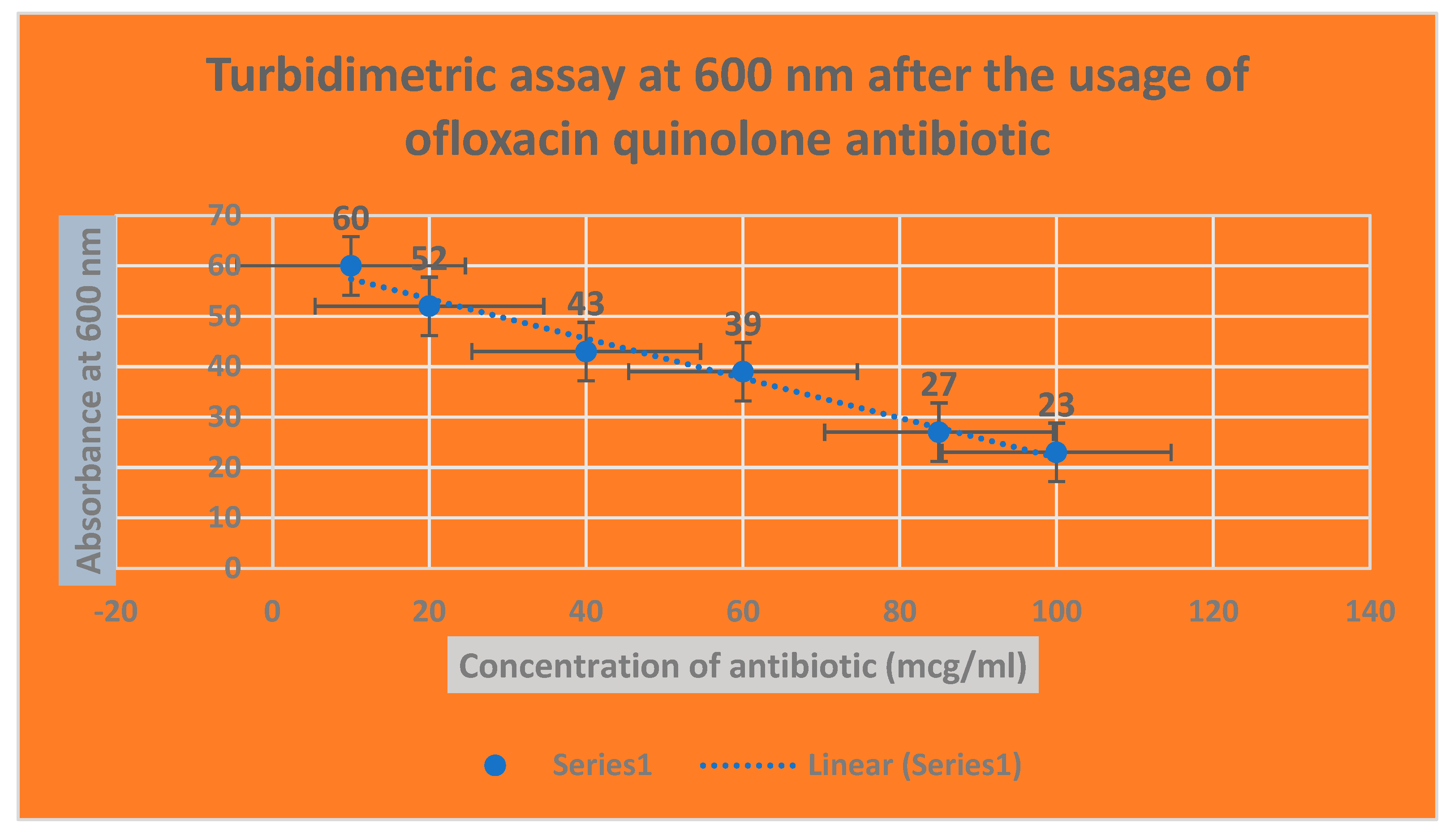

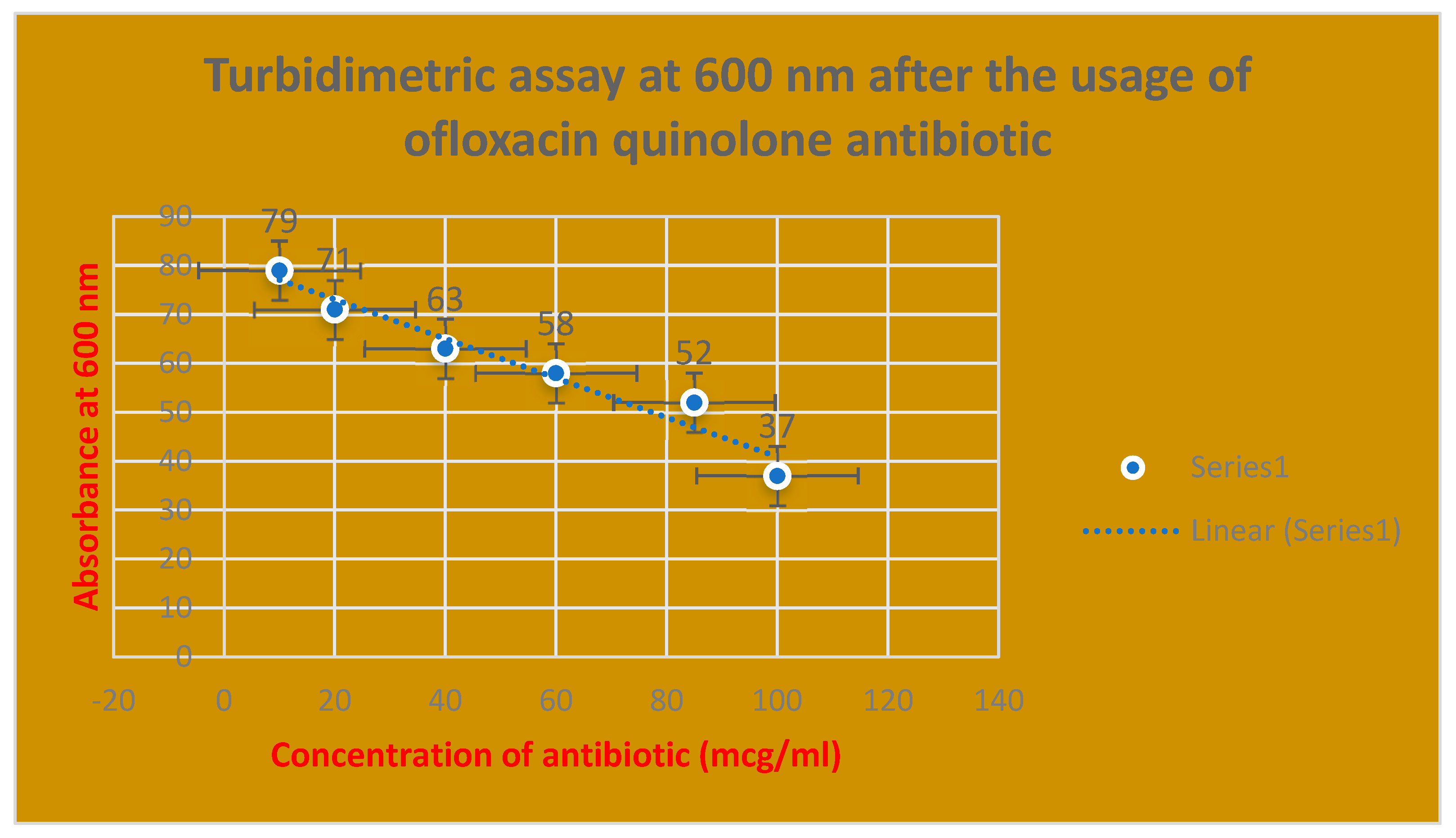

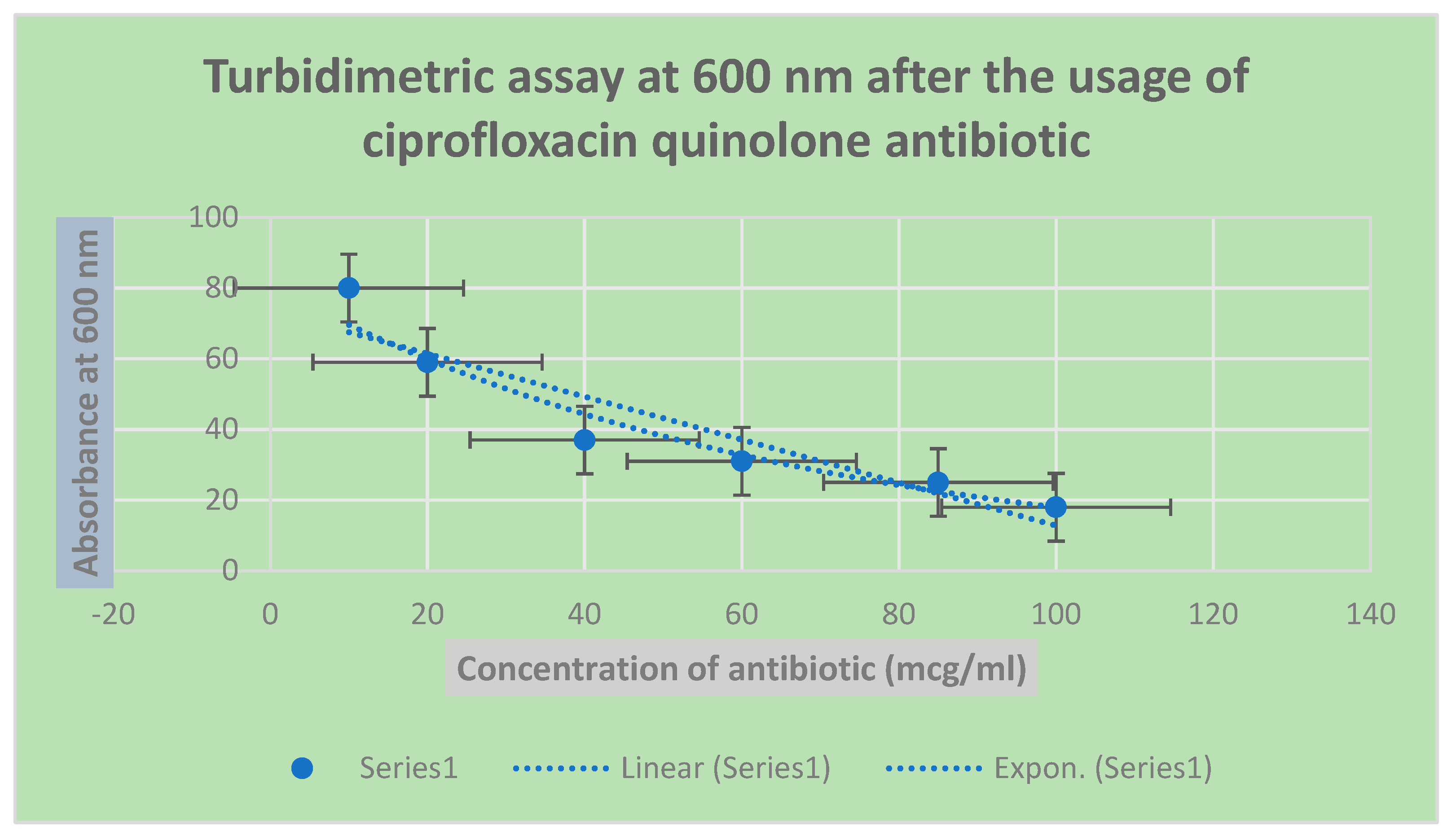

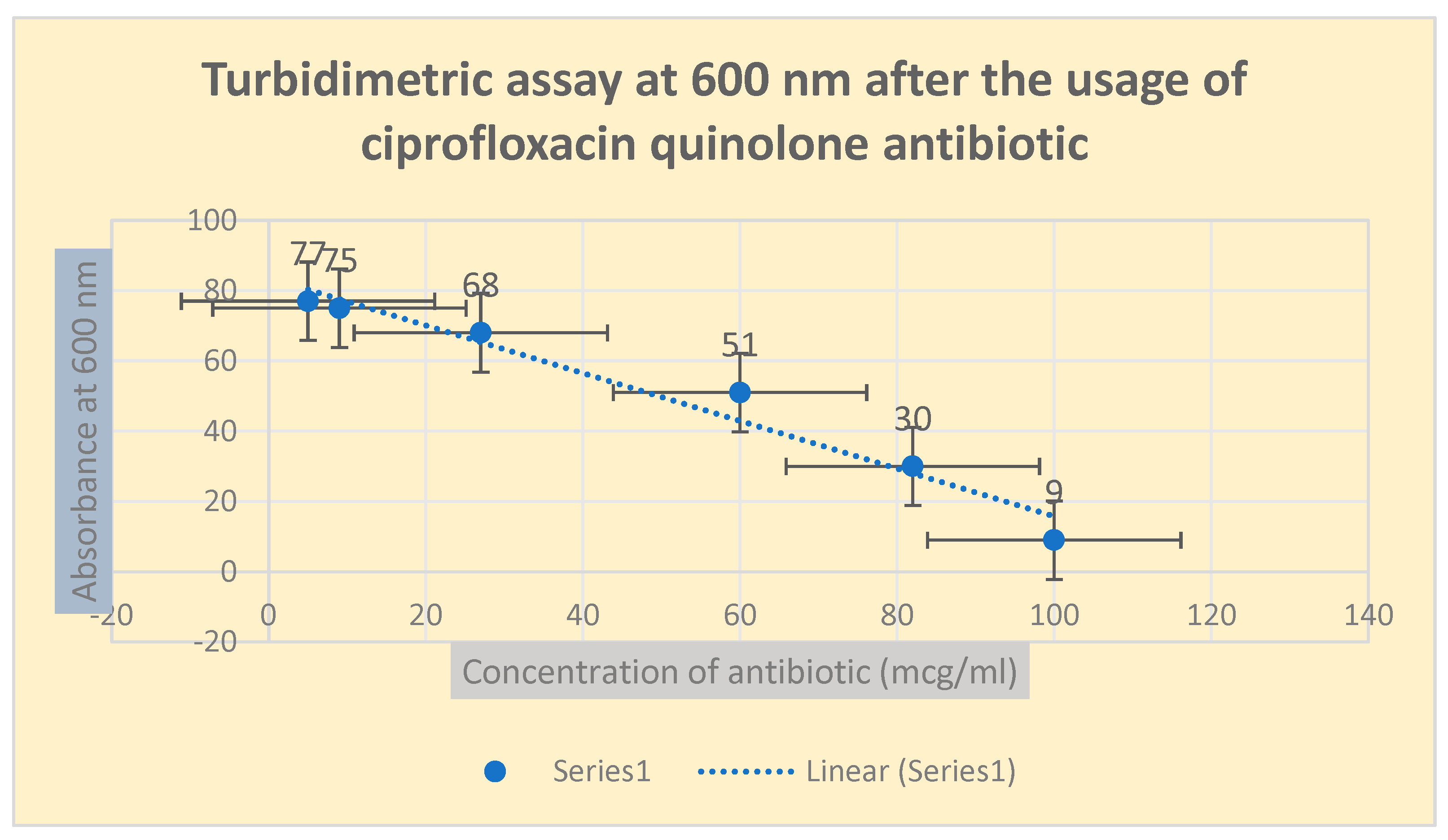

This was performed using turbidimetric assay at 600 nm wavelength. The results were confirmed using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) quinolone broth dilution technique. Ticoplanin glycopeptide was used as a standard antibiotic in both experiments.

One hundred ml cultures of resistant bacterial isolates were maintained in slants of tryptamine-soy broth, then were incubated at 35 ̊C for 18-24 hours. A series of 5 ml volume test tubes containing different concentrations of the test antibiotics ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin ( 10, 20, 30, 50,70, 85, 100 µg/ml) in a nutrient broth liquid mixture inoculated with 1 ml volume of 100 cfu/ml of the test infectious agents were prepared. Incubation of the test tubes containing the mixture at 37 ̊C for 8 hours was followed later. The growth of infectious agents inside the test tubes was noticed through the detection of visible turbidity using

UV spectrophotometer at 600 nm wavelength.23

A stock solution of nutrient broth containing 1 g buffalo tissue digest blended with 3.5 g beef extract in 500 ml distilled deionized water was prepared aseptically in 1 liter volumetric flask. This was followed by dispensing a series of 10 ml volume test tubes with the previous prepared stock solution where each test tube contained 9mg/ml nutrient broth.

100 cfu/ml inoculum of each infectious agent was added separately to each test tube of the previously prepared serious test tubes.

Later, 1ml of different concentrations of ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin antibiotics (10, 20, 30, 40, 80, 100 µg/ml) was added separately to each test tube containing the infectious agents along with the control tube.

Afterwards, the series of the test tubes and the control tube were incubated at 37 ̊C, pH 6.9 ± 0.2 for 18-24 hours.

The presence of turbidity was determined visually in the test tubes then compared with that in the control tube to estimate the MICs and the occurrence of different the antibiotic resistance patterns.24

This was carried out using the third generation of high throughput sequencing PacBio technique in PacBio sequencer. The procedure was performed according to PacBio RS II kit with catalog number PacBio RS II purchased from Pacific Bio-sciences company, USA.

These were done using BLASTn and Clustal omega softwares.

These were achieved applying SWISS-DOCK software.

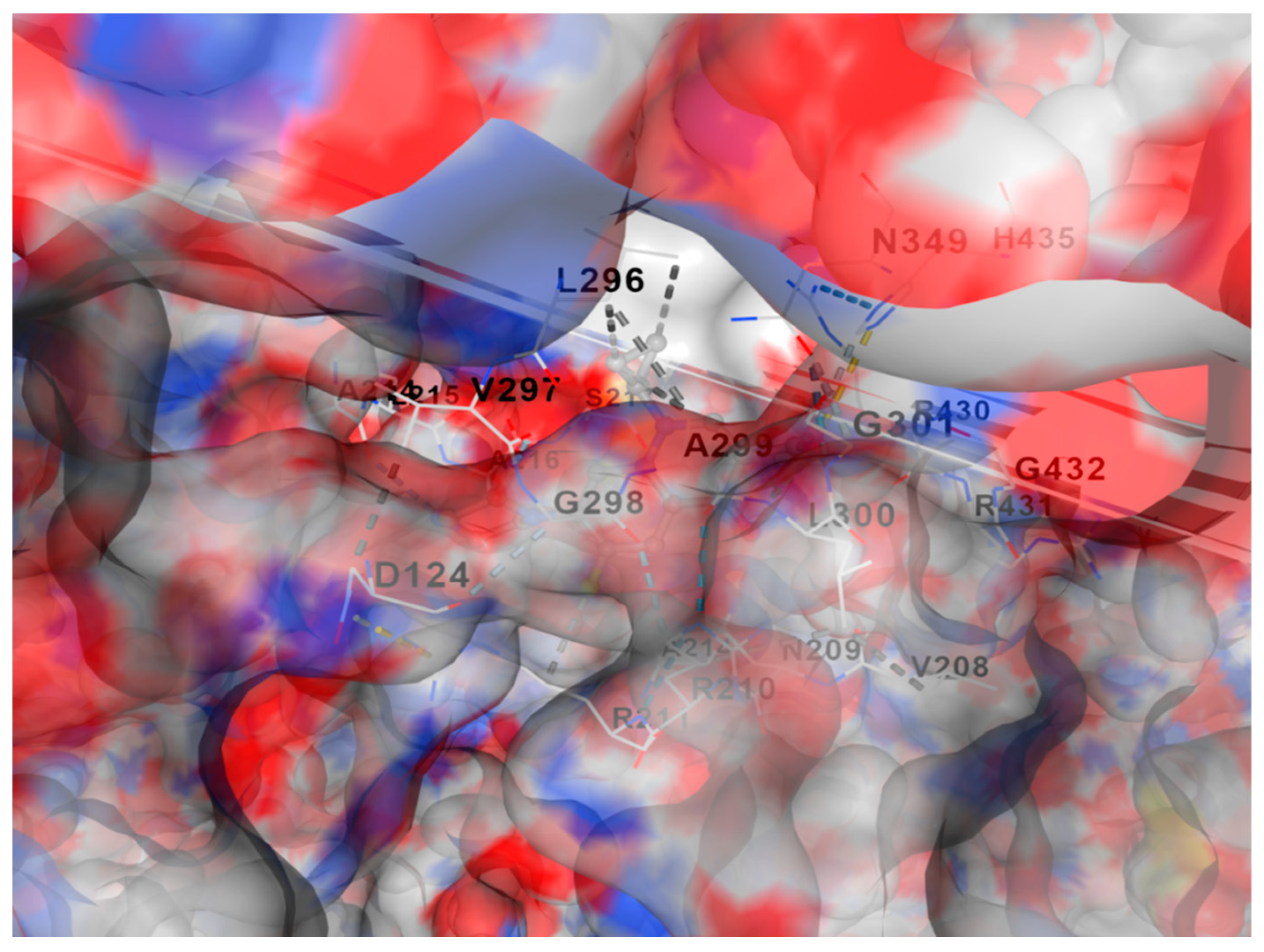

Figure 1.

shows molecular docking of DNA gyrase with fluoroquinolone antibiotic generated using SWISS-DOCK software. Free delta energy reached approximately -7.7 Kcal/mol.

Figure 1.

shows molecular docking of DNA gyrase with fluoroquinolone antibiotic generated using SWISS-DOCK software. Free delta energy reached approximately -7.7 Kcal/mol.

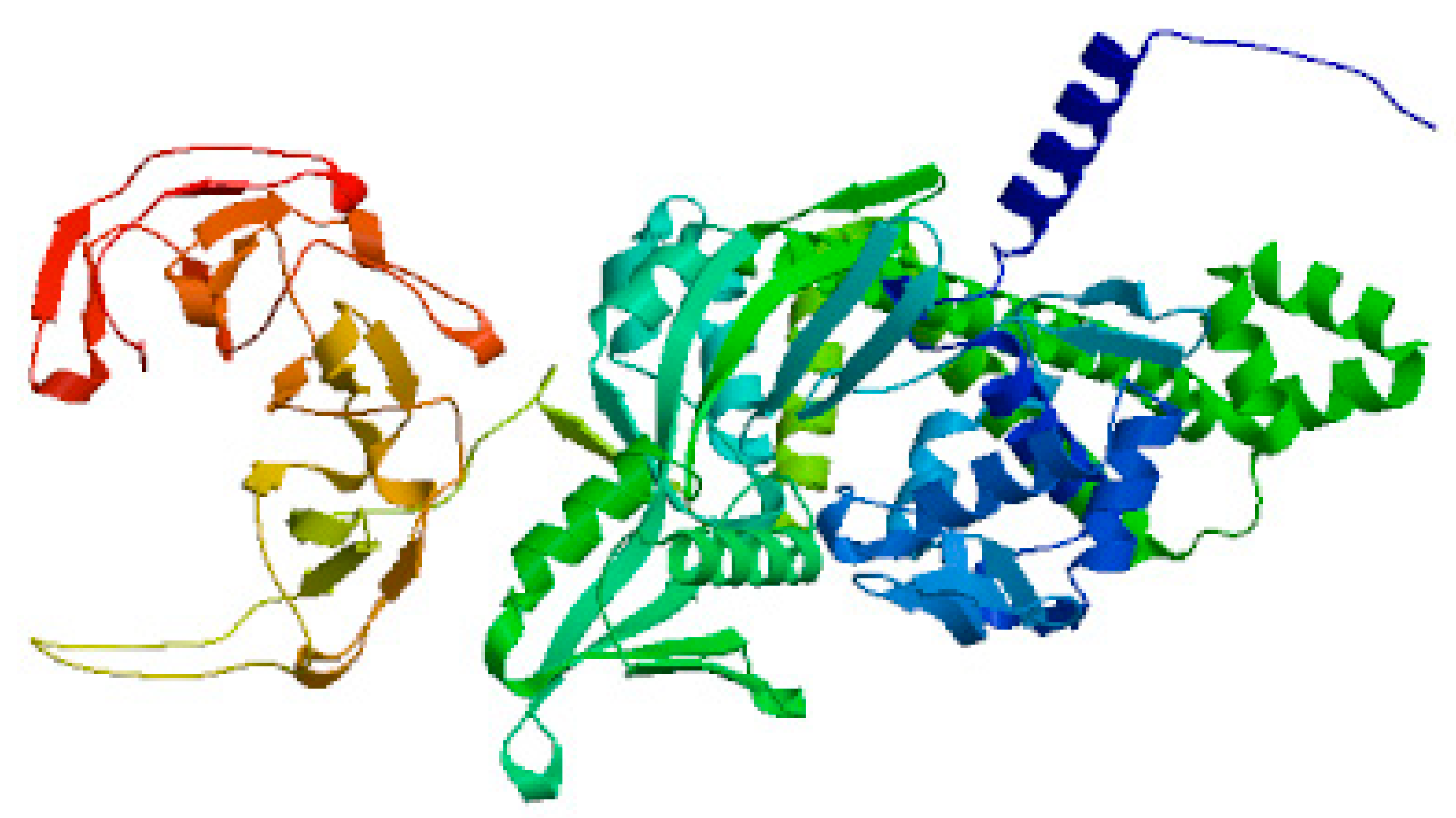

Figure 2.

demonstrates 3D structure of DNA gyrase B generated using SWISS-MODEL software.

Figure 2.

demonstrates 3D structure of DNA gyrase B generated using SWISS-MODEL software.

Figure 2.

demonstrates 3D structure of DNA gyrase A generated using SWISS-MODEL software.

Figure 2.

demonstrates 3D structure of DNA gyrase A generated using SWISS-MODEL software.

Biostatistics

All cultures were conducted in triplets. Their presentation was by means and standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (p value≤ 0.05) was used as means for performing statistical analysis. The F statistical test was used in the present study.

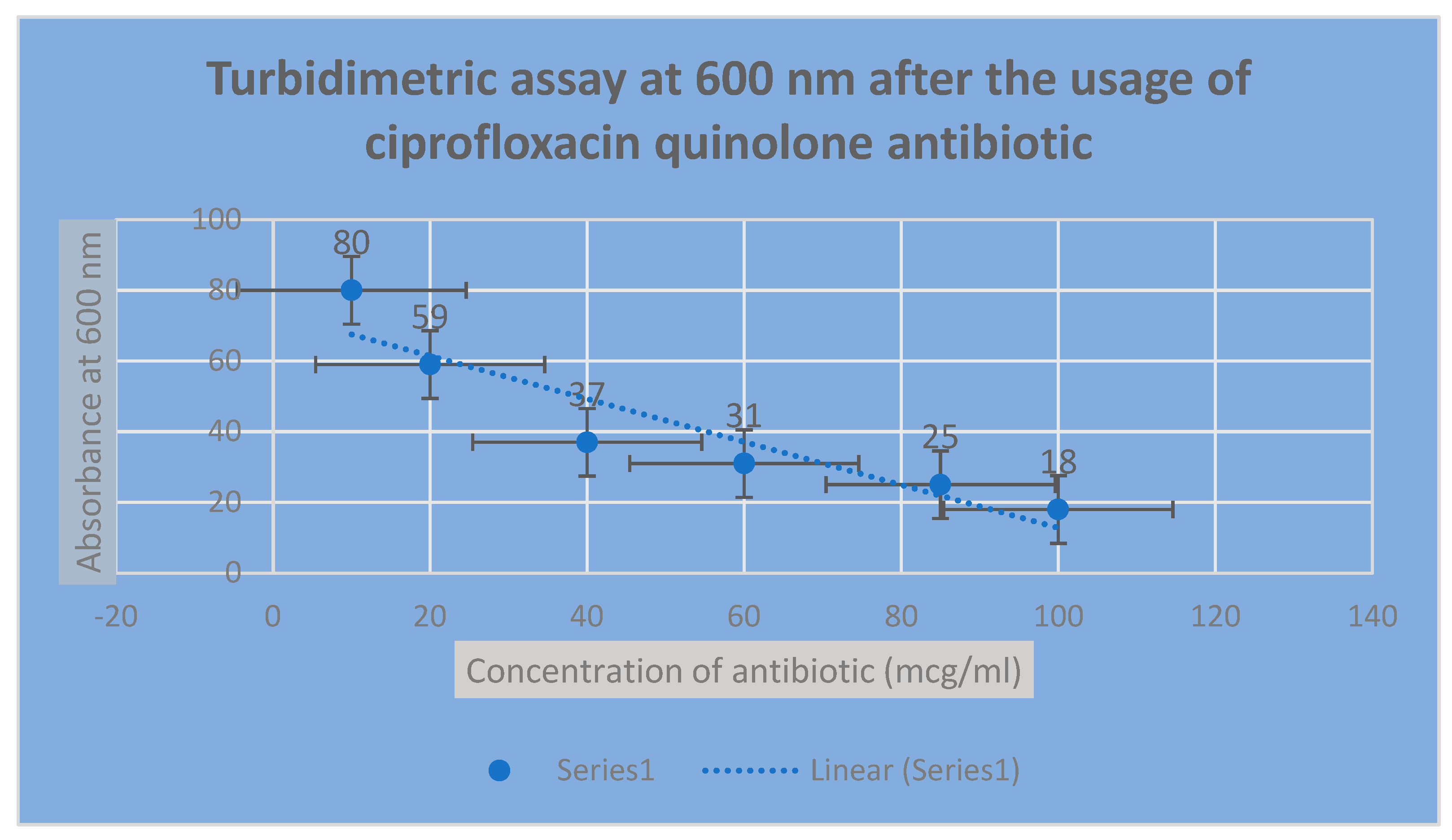

Figure 3.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Pseudomonas aeurognosa through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 3.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Pseudomonas aeurognosa through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

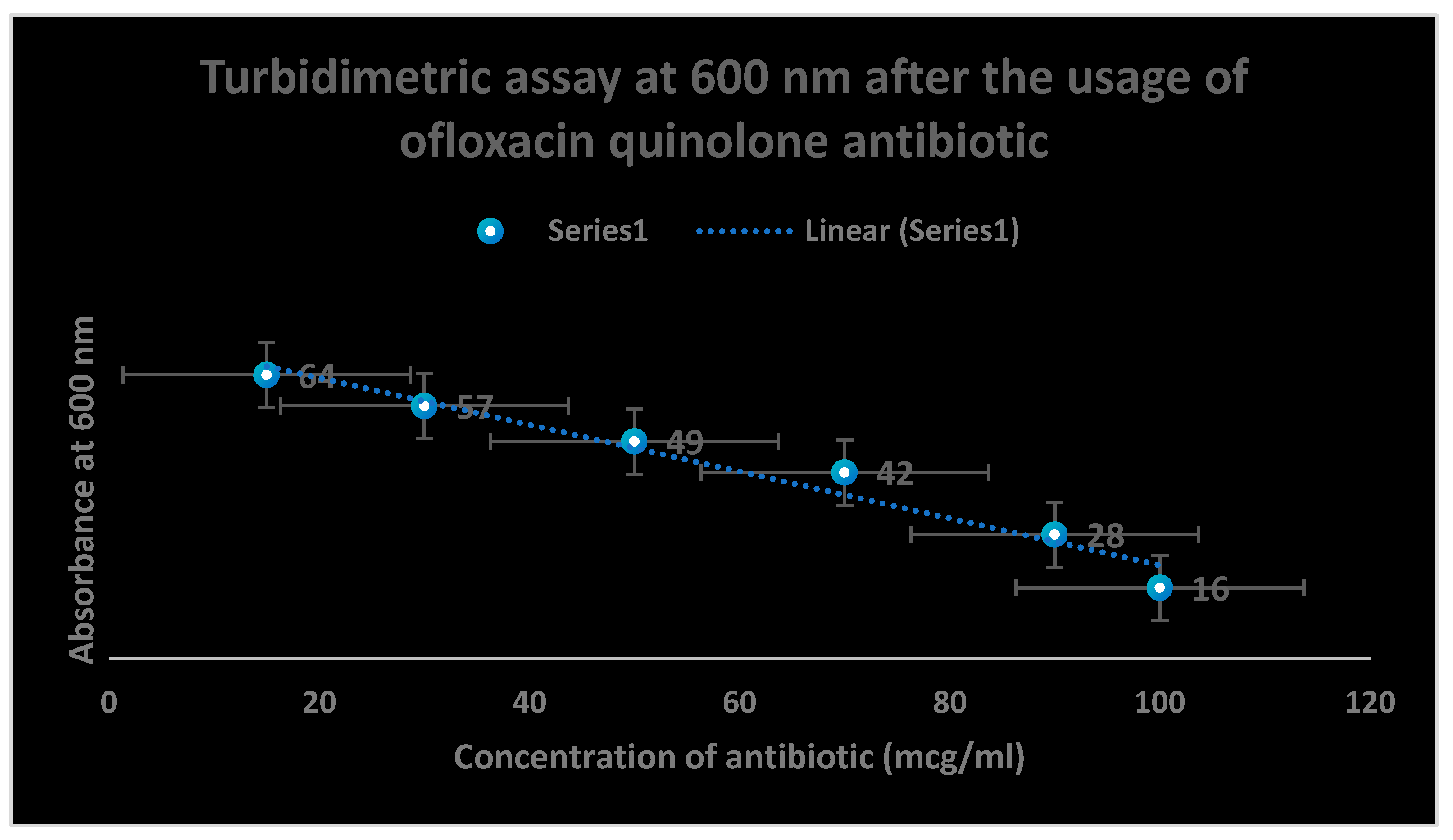

Figure 4.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Pseudomonas aeurognosa through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 4.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Pseudomonas aeurognosa through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 5.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Serratia marcescens through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 5.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Serratia marcescens through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 6.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Streptococcus pneumonae through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 6.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Streptococcus pneumonae through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 7.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Serratia marcescens through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 7.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Serratia marcescens through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 8.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Streptococcus pneumonae through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Figure 8.

It shows the determination of bacterial growth of Streptococcus pneumonae through turbidimetric assay at 600 nm.

Results

Among 200 respiratory and urinary samples collected from patients infected with lower respiratory tract infections and urinary tract infections, 53 participants showed microbial resistance to ciprofloxacin fluoroquinolone antibiotic; while only 19 candidates demonstrated bacterial resistance to ofloxacin antibiotic.

Morphological characterization using Gram staining and biochemical reactions revealed that Pseudomonas aeuroginosa was responsible for 43 % of the bacterial resistance patterns to the test antibiotics; but Serratia marcescens bacterial isolates contributed to 30% of antibiotic resistance. The remaining of resistance form (27%) was attributed to Streptococcus pneumonae.

Molecular detection of the infectious bacterial isolates showed that Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain GPS containing GPS resistant gene encoding DNA gyrase subunit B, Serratia Marcescens strain GSM containing GSM resistant gene encoding DNA gyrase subunit B and Streptococcus pneumonae strain TAP containing TAP resistant gene encoding DNA gyrase subunit A were the major resistant bacterial isolates to fluoroquinolone antibiotics (ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin).

Broth dilution and spectrophotometric turbidimetric techniques indicated that only 72 human volunteers were observed to demonstrate microbial resistance to ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin antibiotics. No resistance was shown to ticoplanin glycopeptide as a standard antibiotic. Minimum concentrations of ticoplanin standard antibiotic was less than 50 µg/ml; while for the test fluoroquinolone antibiotics were detected to greater than 100 µg/ml.

Table 2 and

Table 3 shows the sensitivity of the test antibiotics to the infectious agents.

Molecular docking emphasized that the occurrence of a mutation in either DNA gyrase I or DNA gyrase II in the bacterial infectious agents was the major cause of resistance to the test fluoroquinolone compounds.

Figure 1 shows molecular docking of DNA gyrase with fluoroquinolone antibiotic generated using SWISS-DOCK software. Free delta energy reached approximately -7.7 Kcal/mol.

Figure 2- demonstrates 3D structure of DNA gyrase A generated using SWISS-MODEL software; while

Figure 2 demonstrates 3D structure of DNA gyrase B generated using SWISS-MODEL software.

Discussion

The present study aimed at the detection of the bacterial isolates resistant to fluoroquinolone antibiotics (ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin).

Additionally, the resistant genes responsible for the fluoroquinolone antibiotics were identified molecularly.

Gram staining, morphological characterization along with the biochemical reactions and the third generation high throughput sequencing technique using PacBio sequencer were utilized to detect the potent resistant bacterial isolates to the test antibiotics.

The major bacterial isolates along with their fluoroquinolone resistant genes were detected to be Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain GPS containing GPS resistant gene encoding DNA gyrase subunit B, Serratia Marcescens strain GSM containing GSM resistant gene encoding DNA gyrase subunit B and Streptococcus pneumonae strain TAP comprising TAP resistant gene encoding DNA gyrase subunit A.

The major resistant bacterial isolates were screened for their abilities to resist the fluoroquinolone antibiotics using the broth dilution technique. MICs of the test fluoroquinolone antibiotics (ciprofloxacin ad ofloxacin) were shown to be greater than 100 µg/ml; while for the ticoplanin glycopeptide standard antibiotic were less than 50 µg/ml.

The pattern of antibiotic resistance was confirmed through the observation of turbidimetric spectrophotometric experimentation at 600 nm wavelength.

Molecular docking in the present study emphasized that the occurrence of a mutation in either DNA gyrase I or II in the bacterial pathogens was the origin of the pattern of antibiotic resistance versus the the test fluoroquinolone antibiotics (ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin). In a comparison with a S Bhatt, S Chatterjee 2022 study , the mechanism of bacterial resistance to fluoroquinolone antibiotics in this previous study was shown to be multi-factorial including genetic mutation and changes in drug entry and efflux.25

Abbreviations

MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration.

Funding

This study was funded by the single author, Prof. Mohammed Kassab.

Conflict of interest/ Competing of interests

There is no conflict of interest; as well as no competing of interests exist.

Ethical statement

Priority was given in the current study to all pertinent institutional, national, and international regulations dealing with the use and care of persons. All study procedures involving human participants have been approved by Cairo University's Ethical Committee for Human Handling (ECHCU), located in the Faculty of Pharmacy (permission number FKZ460/2023). The research aimed to reduce the pain experienced by human subjects. With informed consent, the use of human subjects or samples in studies was authorized. The World Medical Association's rule of ethics for human research, the Declaration of Helsinki, was followed in the conduct of the current investigation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

This study was performed completely by the single author, Prof. Mohammed Kassab.

Data availability and material

Datasets and material used and/or analyzed in the present study are deposited in GenBank at NCBI with accession numbers: PQ329324, PQ329325 and 329326.

Acknowledgement

The Cairo University and the Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University are acknowledged for their support.

References

- 1. Lewis G, Juhasz A, Smith E. Detection of antibacterial-like activity on a silica surface: fluoroquinolones and their environmental metabolites. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2011 Aug;19(7):2795-801. Epub 2012 Feb 5. PMID: 22311580. [CrossRef]

- 2. Sidhu H, Bae HS, Ogram A, O'Connor G, Yu F. Azithromycin and Ciprofloxacin Can Promote Antibiotic Resistance in Biosolids and Biosolids-Amended Soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2021 Jul 27;87(16):e0037321. Epub 2021 Jul 27. PMID: 34085858; PMCID: PMC8315170. [CrossRef]

- 3. Sukul P, Spiteller M. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics in the environment. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 2007;191:131-62. PMID: 17708074. [CrossRef]

- 4. Adachi F, Yamamoto A, Takakura K, Kawahara R. Occurrence of fluoroquinolones and fluoroquinolone-resistance genes in the aquatic environment. Sci Total Environ. 2013 Feb 1;444:508-14. Epub 2013 Jan 3. PMID: 23291652. [CrossRef]

- 5. Jeong HS, Kim JA, Shin JH, Chang CL, Jeong J, Cho JH, Kim MN, Kim S, Kim YR, Lee CH, Lee K, Lee MA, Lee WG, Shin JH, Lee JN. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance and mutations in the gyrase and topoisomerase IV genes in Salmonella isolated from 12 tertiary-care hospitals in Korea. Microb Drug Resist. 2011 Dec;17(4):551-7. Epub 2011 Aug 10. PMID: 21830947. [CrossRef]

- 6. Tamang MD, Nam HM, Kim A, Lee HS, Kim TS, Kim MJ, Jang GC, Jung SC, Lim SK. Prevalence and mechanisms of quinolone resistance among selected nontyphoid Salmonella isolated from food animals and humans in Korea. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011 Nov;8(11):1199-206. Epub 2011 Aug 30. PMID: 21877929. [CrossRef]

- 7. Yu F, Chen Q, Yu X, Pan J, Li Q, Yang L, Chen C, Zhuo C, Li X, Zhang X, Huang J, Wang L. High prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinant aac(6')-Ib-cr amongst Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates from hospitalised paediatric patients with diarrhoea in China. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011 Feb;37(2):152-5. Epub 2010 Dec 15. PMID: 21163630. [CrossRef]

- 8. Crémet L, Caroff N, Dauvergne S, Reynaud A, Lepelletier D, Corvec S. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants in ESBL Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates over a 1-year period in a French hospital. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2011 Jun;59(3):151-6. Epub 2009 May 29. PMID: 19481883. [CrossRef]

- 9. Minarini LA, Poirel L, Cattoir V, Darini AL, Nordmann P. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants among enterobacterial isolates from outpatients in Brazil. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008 Sep;62(3):474-8. Epub 2008 Jun 13. PMID: 18552340. [CrossRef]

- 10. Yang H, Chen H, Yang Q, Chen M, Wang H. High prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes qnr and aac(6')-Ib-cr in clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from nine teaching hospitals in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008 Dec;52(12):4268-73. Epub 2008 Sep 22. Erratum in: Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009 Feb;53(2):847. PMID: 18809939; PMCID: PMC2592877. [CrossRef]

- 11. Jiang Y, Zhou Z, Qian Y, Wei Z, Yu Y, Hu S, Li L. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants qnr and aac(6')-Ib-cr in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008 May;61(5):1003-6. Epub 2008 Feb 25. PMID: 18299311. [CrossRef]

- 12. Briales A, Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Velasco C, de Alba PD, Rodríguez-Baño J, Martínez-Martínez L, Pascual A. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants qnr and aac(6')-Ib-cr in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Spain. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012 May;39(5):431-4. Epub 2012 Feb 22. PMID: 22365240. [CrossRef]

- 13. Hassan WM, Hashim A, Domany R. Plasmid mediated quinolone resistance determinants qnr, aac(6')-Ib-cr, and qep in ESBL-producing Escherichia coli clinical isolates from Egypt. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2012 Oct-Dec;30(4):442-7. PMID: 23183470. [CrossRef]

- 14. Ibrahim D, Awad A, Younis G. Prevalence and characterization of quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from retail raw beef and poultry meat in Egypt. J Adv Vet Anim Res. 2023 Sep 30;10(3):490-499. PMID: 37969807; PMCID: PMC10636088. [CrossRef]

- 15. Aworh MK, Kwaga JKP, Hendriksen RS, Okolocha EC, Harrell E, Thakur S. Quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli at the interface between humans, poultry and their shared environment- a potential public health risk. One Health Outlook. 2023 Feb 28;5(1):2. PMID: 36855171; PMCID: PMC9976508. [CrossRef]

- 16. Yang F, Zhang S, Shang X, Wang L, Li H, Wang X. Characteristics of quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from bovine mastitis in China. J Dairy Sci. 2018 Jul;101(7):6244-6252. Epub 2018 Mar 28. PMID: 29605334. [CrossRef]

- 17. Ni Q, Tian Y, Zhang L, Jiang C, Dong D, Li Z, Mao E, Peng Y. Prevalence and quinolone resistance of fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in 6 communities and 2 physical examination center populations in Shanghai, China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016 Dec;86(4):428-433. Epub 2016 Jul 12. PMID: 27681363. [CrossRef]

- 18. Hrovat K, Seme K, Ambrožič Avguštin J. Increasing Fluroquinolone Susceptibility and Genetic Diversity of ESBL-Producing E. coli from the Lower Respiratory Tract during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024 Aug 23;13(9):797. PMID: 39334972; PMCID: PMC11428890. [CrossRef]

- 19. Yoon JH, Lee SY. A double layer agar plate method results in an improvement for enumerating Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus exposed to nutrient deficiency and refrigeration temperature. Food Microbiol. 2022 Oct;107:104085. Epub 2022 Jun 21. PMID: 35953179. [CrossRef]

- 20. Ridder MJ, Daly SM, Hall PR, Bose JL. Quantitative Hemolysis Assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2341:25-30. PMID: 34264457. [CrossRef]

- 21. Aleem M, Azeem AR, Rahmatullah S, Vohra S, Nasir S, Andleeb S. Prevalence of Bacteria and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Hospital Water and Surfaces. Cureus. 2021 Oct 13;13(10):e18738. PMID: 34790487; PMCID: PMC8587521. [CrossRef]

- 22. Leite G, Rezaie A, Mathur R, Barlow GM, Rashid M, Hosseini A, Wang J, Parodi G, Villanueva-Millan MJ, Sanchez M, Morales W, Weitsman S, Pimentel M; REIMAGINE Study Group. Defining Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth by Culture and High Throughput Sequencing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Feb;22(2):259-270. Epub 2023 Jun 12. PMID: 37315761. [CrossRef]

- 23. Arabski M, Wasik S, Piskulak P, Góźdź N, Slezak A, Kaca W. Analiza dyfuzji antybiotyków z zelu agarozowego metodami spektrofotometrii i interferometrii laserowej [Analysis of antibiotic diffusion from agarose gel by spectrophotometry and laser interferometry methods]. Polim Med. 2011;41(3):25-32. Polish. PMID: 22046824.

- 24. Mohammadzadeh T, Sadjjadi S, Habibi P, Sarkari B. Comparison of Agar Dilution, Broth Dilution, Cylinder Plate and Disk Diffusion Methods for Evaluation of Anti-leishmanial Drugs on Leishmania promastigotes. Iran J Parasitol. 2012;7(3):43-7. PMID: 23109961; PMCID: PMC3469171.

- Bhatt S, Chatterjee S. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics: Occurrence, mode of action, resistance, environmental detection, and remediation - A comprehensive review. Environ Pollut. 2022 Dec 15;315:120440. Epub 2022 Oct 17. PMID: 36265724. [CrossRef]

Table 2.

It shows the susceptibility of infectious agents towards ofloxacin antibiotic using the broth dilution technique:.

Table 2.

It shows the susceptibility of infectious agents towards ofloxacin antibiotic using the broth dilution technique:.

| Infectious agent |

MIC (µg/ml) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

164 |

| Serratia marcescens |

107 |

| Streptococcus pneumonae |

138 |

Table 3.

It shows the susceptibility of infectious agents towards ciprofloxacin antibiotic using the broth dilution technique:.

Table 3.

It shows the susceptibility of infectious agents towards ciprofloxacin antibiotic using the broth dilution technique:.

| Infectious agent |

MIC (µg/ml) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

151 |

| Serratia marcescens |

145 |

| Streptococcus pneumonae |

126 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).