Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Post Traumatic Growth

1.2. Theoretical Concepts

1.2.1. The Lifeworld

1.2.2. Social Identity Approach

1.2.3. Redemption Narratives

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participant

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

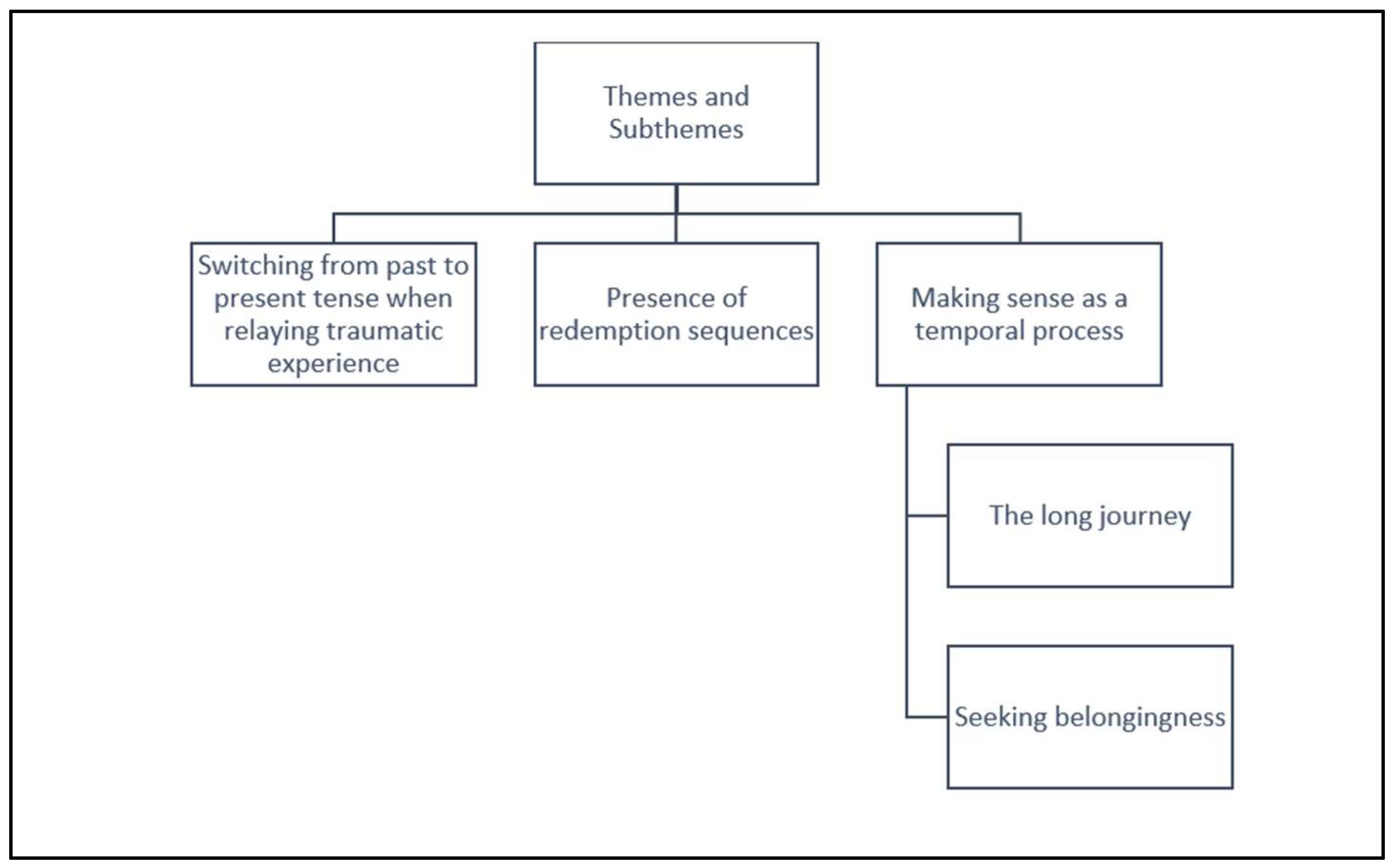

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Switching from Past to Present Tense When Relaying Traumatic Experience

3.2. Presence of Redemption Sequences

3.3. Making Sense as a Temporal Process

3.3.1. Subtheme – The Long Journey

3.3.2. Subtheme –Seeking Belongingness

3.4. Strengths and Limitations, Implications, and Directions for Future Research

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, E.; Squires, P. Rethinking Knife Crime: Policing, violence and moral panic? 2022, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Browne, K.D.; et al. Knife crime offender characteristics and interventions—A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2022, 67, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.; Walklate, S.L. Gendered objects and gendered spaces: The invisibilities of ‘knife’ crime. Current Sociology 2020, 70, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haylock, S.; et al. Risk factors associated with knife-crime in United Kingdom among young people aged 10–24 years: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R. UK: The reality behind the ‘knife crime’ debate. Race & Class 2010, 52, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, E. Youth Knife Crime in London and Croyden: A Data and Literary Analysis. Contemporary Challenges: The Global Crime, Justice and Security Journal 2022, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, E.; Sinclair, P. Devastating after effects: Anti-knife crime sessions, in Impact evaluation. 2019, The Flavasum Trust.

- Harding, S. Getting to the point? reframing narratives on Knife Crime. Youth Justice 2020, 20, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; et al. Promising approaches to knife crime: An exploratory study. 2022, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation: Manchester.

- Squires, P. The knife crime ‘epidemic’ and British politics. British Politics 2009, 4, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, D.E. Time to stop twisting the knife: A critical commentary on the rights and wrongs of criminal justice responses to problem youth in the UK. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law 2009, 31, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, B.; et al. The rising burden of penetrating knife injuries. Injury Prevention 2021, 27, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, L.; Harinam, V.; Ariel, B. Victims, offenders and victim-offender overlaps of knife crime: A social network analysis approach using police records. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, G. Fear and fashion: The use of knives and other weapons by young people. Working with Young Men 2004, 4, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnakota, D.; et al. Exploring UK Knife crime and its associated factors: A content analysis of online newspapers. Nepal J Epidemiol 2022, 12, 1242–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, J.-J.; et al. Injury by knife crime amongst children is associated with socioeconomic deprivation: An observational study. Pediatric Surgery International 2023, 39, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S. A reputational extravaganza? The role of the urban street gang in the riots in London 2012 [cited 2022 November 2021]; Available from: https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/publications/cjm/article/reputational-extravaganza-role-urban-street-gang-riots-londo.

- Foster, R. Knife Crime interventions: ‘What works’? 2013, The Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research: www.sccjr.ac.uk.

- Ramshaw, N.; Dawson, P. Exploring the impact of knife imagery in anti-knife crime campaigns. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2022, 17, paac045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVie, S. Gang Membership and Knife Carrying: Findings from the Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime. 2010.

- Traynor, P.R. Closing the ‘security gap’: Young people, ‘street life’ and knife crime. 2016, University of Leeds: White Rose eTheses Online.

- Clement, M. Teenagers under the knife: A decivilising process. Journal of Youth Studies 2010, 13, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlatidou, A.; et al. Understanding Knife Crime and Trust in Police with Young People in East London. Crime and Delinquency, 2021.

- Deuchar, R.; Miller, J.; Densley, J. The Lived Experience of Stop and Search in Scotland: There Are Two Sides to Every Story. Police Quarterly 2019, 22, 416–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.A.; Walklate, S. Excavating Victim Stories: Making Sense of Agency, Suffering and Redemption, in The Emerald Handbook of Narrative Criminology, J. Fleetwood; et al., Editors. 2019, Emerald Publishing Limited: ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mmu/detail.action?docID=5900353.

- Sethi, D. European report on preventing violence and knife crime among young people, D. Sethi; et al., Editors. 2010, World Health Organization: London.

- Bullock, K.; et al. Police practitioner views on the challenges of analysing and responding to knife crime. Crime Science 2023, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, F.; et al. Public Health, Youth Violence, and Perpetrator Well-Being. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 2015, 21, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haegerich, T.M.; Dahlberg, L.L. Violence as a Public Health Risk. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 2011, 5, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, K.M.; Rogers, K.B. Beyond the Rape “Victim”–“Survivor” Binary: How Race, Gender, and Identity Processes Interact to Shape Distress. Sociological Forum 2020, 35, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, S.A.; et al. Social Identity, Health and Well-Being: An Emerging Agenda for Applied Psychology. Applied Psychology: An International Review 2009, 58, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Claire, L.; He, Y. How Do I Know if I Need a Hearing Aid? Further Support for the Self-Categorisation Approach to Symptom PerceptionAbstract. Applied Psychology 2009, 58, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Pill, R.; Jones, A. Medication, chronic illness and identity: The perspective of people with asthma. Soc Sci Med 1997, 45, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickreme, E.; et al. Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: Challenges, opportunities, and recommendations. Journal of Personality 2021, 89, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S. What Doesn’t Kill Us: A Guide to Overcoming Adversity and Moving Forward. 2013, London: Piatkus.

- Kinsella, E.L.; et al. Post-traumatic growth following acquired brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 2015, 6, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G. Posttraumatic growth: Theory, research and applications. 2018, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY.

- Muldoon, O.T.; et al. The social psychology of responses to trauma: Social identity pathways associated with divergent traumatic responses. European Review of Social Psychology 2019, 30, 311–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, A.J. Fictional father?: Oliver Sacks and the revalidation of pathography. Medical Humanities 2013, 39, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, H. Astronomers of the inward: On the histories and case histories of Alexander Luria and Oliver Sacks. Studies in East European Thought 2022, 74, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, O. Luria and “Romantic Science”, in The Cambridge Handbook of Cultural-Historical Psychology, A. Yasnitsky, R. van der Veer, and M. Ferrari, Editors. 2014, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. p. 517-528.

- Hemingway, A. Lifeworld-led care: Is it relevant for well-being and the fifth wave of public health action? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being 2011, 6, 10364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todres, L.; Galvin, K.; Dahlberg, K. Lifeworld-led healthcare: Revisiting a humanising philosophy that integrates emerging trends. Med Health Care Philos 2007, 10, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, P. The lifeworld—Enriching qualitative evidence. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2016, 13, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C.; et al. The New Psychology of Health : Unlocking the Social Cure. 2018, Florence, UNITED STATES: Routledge.

- Vargas, G.M. Alfred Schutz’s Life-World and Intersubjectivity. Open Journal of Social Sciences 2020, 8, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D. Social identity and intergroup relations, in APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Volume 2: Group processes. 2015, American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, US. pp. 203-228.

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of inter-group conflict., in The social psychology of inter-group relations, W.G. Austin and S. Worchel, Editors. 1979, Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA.

- Turner, J.C. Social categorisation and the self-concept: A social cognitive theory of group behaviour, in Advances in Group Processes, E.J. Lawler, Editor. 1985, JAI Press: Greenwch, CT. p. 77-122.

- Praharso, N.F.; Tear, M.J.; Cruwys, T. Stressful life transitions and wellbeing: A comparison of the stress buffering hypothesis and the social identity model of identity change. Psychiatry Research 2017, 247, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, J.; et al. Turning to Others in Times of Change: Social Identity and Coping with Stress, in The Psychology of Prosocial Behavior : Group Processes, Intergroup Relations, and Helping, S. Stürmer and M. Snyder, Editors. 2009, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Haslam, C.; et al. Life Change, Social Identity, and Health. Annual Review of Psychology 2021, 72, 635–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, O.T.; et al. Social cure and social curse: Social identity resources and adjustment to acquired brain injury. European Journal of Social Psychology 2019, 49, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, J.; Williams, R. Children and young people who are refugees, internally displaced persons or survivors or perpetrators of war, mass violence and terrorism. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012, 25, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; Josselson, R.; Lieblich, A. Identity and story: Creating self in narrative. 2006: American Psychological Association.

- McAdams, D.P.; McLean, K.C. Narrative Identity. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2013, 22, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. The Stories we Live by: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self. 1993, New York: William Morrow & Company.

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. 1978, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- McAdams, D.P. “First we invented stories, then they changed us”: The Evolution of Narrative Identity. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture 2019, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live By. 2006: Cambridge University Press.

- Dingle, G.A.; Cruwys, T.; Frings, D. Social Identities as Pathways into and out of Addiction. Front Psychol 2015, 6, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, K. Case Study Research, in Research Design and Methods: An Applied Guide for the Scholar-Practitioner G.J. Burkholder; et al., Editors. 2019, SAGE Publications Inc: Thousand Oaks, United States.

- Smith, J.A. Flowers, and M. Larkin, Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. 2009, London: SAGE.

- Nizza, I.E.; Farr, J.; Smith, J.A. Achieving excellence in interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): Four markers of high quality. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2021, 18, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, S.; et al. Navigating the Terrain of Lived Experience: The Value of Lifeworld Existentials for Reflective Analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2013, 12, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillemer, D.B. Momentous events, Vivid memories. 2009: Harvard University Press.

- Singer, J.A.; et al. Self-Defining Memories, Scripts, and the Life Story: Narrative Identity in Personality and Psychotherapy. Special Issue: Personality Psychology and Psychotherapy 2012, 81, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderveren, E.; Bijttebier, P.; Hermans, D. The Importance of Memory Specificity and Memory Coherence for the Self: Linking Two Characteristics of Autobiographical Memory. Frontiers in Psychology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; Bowman, P.J. Narrating life’s turning points: Redemption and contamination, in Turns in the road: Narrative studies of lives in transition. 2001, American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, US. p. 3-34.

- Bauer, J.J.; McAdams, D.P.; Pals, J.L. Narrative identity and eudaimonic well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 2008, 9, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; et al. Stories of commitment: The psychosocial construction of generative lives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1997, 72, 678–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; et al. When Bad Things Turn Good and Good Things Turn Bad: Sequences of Redemption and Contamination in Life Narrative and their Relation to Psychosocial Adaptation in Midlife Adults and in Students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2001, 27, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, S.A.; et al. Taking the strain: Social identity, social support, and the experience of stress. British Journal of Social Psychology 2005, 44, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; et al. Identity and Emergency Intervention: How Social Group Membership and Inclusiveness of Group Boundaries Shape Helping Behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2005, 31, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, S.A.; et al. Social identity, social influence and reactions to potentially stressful tasks: Support for the self-categorization model of stress. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress 2004, 20, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, J.U.; et al. Making support work: The interplay between social support and social identity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2014, 55, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, K.M. “If I Was a ‘Real Man’”: The Role of Gender Stereotypes in the Recovery Process for Men Who Experience Sexual Victimization. The Journal of Men’s Studies 2020, 28, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A.R.; et al. The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 1996, 351, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.; Tronick, E. Intersubjectivity: Conceptual Considerations in Meaning-Making With a Clinical Illustration. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 12, 715873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formanowicz, M.; Bulska, D.; Shnabel, N. The role of agency and communion in dehumanization—An integrative perspective. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2023, 49, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; et al. Narrative coherence, psychopathology, and wellbeing: Concurrent and longitudinal findings in a mid-adolescent sample. Journal of Adolescence 2020, 79, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhoot, A.F.; et al. Making sense of traumatic memories: Memory qualities and psychological symptoms in emerging adults with and without abuse histories. Memory 2013, 21, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.E.; Berenbaum, H. Are Specific Emotion Regulation Strategies Differentially Associated with Posttraumatic Growth Versus Stress? Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 2015, 24, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boals, A.; Murrell, A.R. I Am > Trauma: Experimentally Reducing Event Centrality and PTSD Symptoms in a Clinical Trial. Journal of Loss and Trauma 2016, 21, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, C.; Truchot, D.; Canevello, A. What promotes post traumatic growth? A systematic review. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 2021, 5, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C.; et al. The Importance of Social Groups for Retirement Adjustment: Evidence, Application, and Policy Implications of the Social Identity Model of Identity Change. Social Issues and Policy Review 2019, 13, 93–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, N.; et al. Exploring social identity change during mental healthcare transition. European Journal of Social Psychology 2017, 47, 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.B.; et al. Social identity in people with multiple sclerosis: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Social Care and Neurodisability 2014, 5, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conneely, M.; et al. Understanding Identity Changes in Psychosis: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2020, 47, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C.; et al. Maintaining group memberships: Social identity continuity predicts well-being after stroke. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2008, 18, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R.S.; et al. The man who used to shrug—One man’s lived experience of TBI. NeuroRehabilitation 2020, 47, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M.; et al. The role of psychological symptoms and social group memberships in the development of post-traumatic stress after traumatic injury. British Journal of Health Psychology 2012, 17, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y. With a little help from my friends: A follow-up study on the contribution of interpersonal characteristics to posttraumatic growth among suicide-loss survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2019, 11, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).