Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

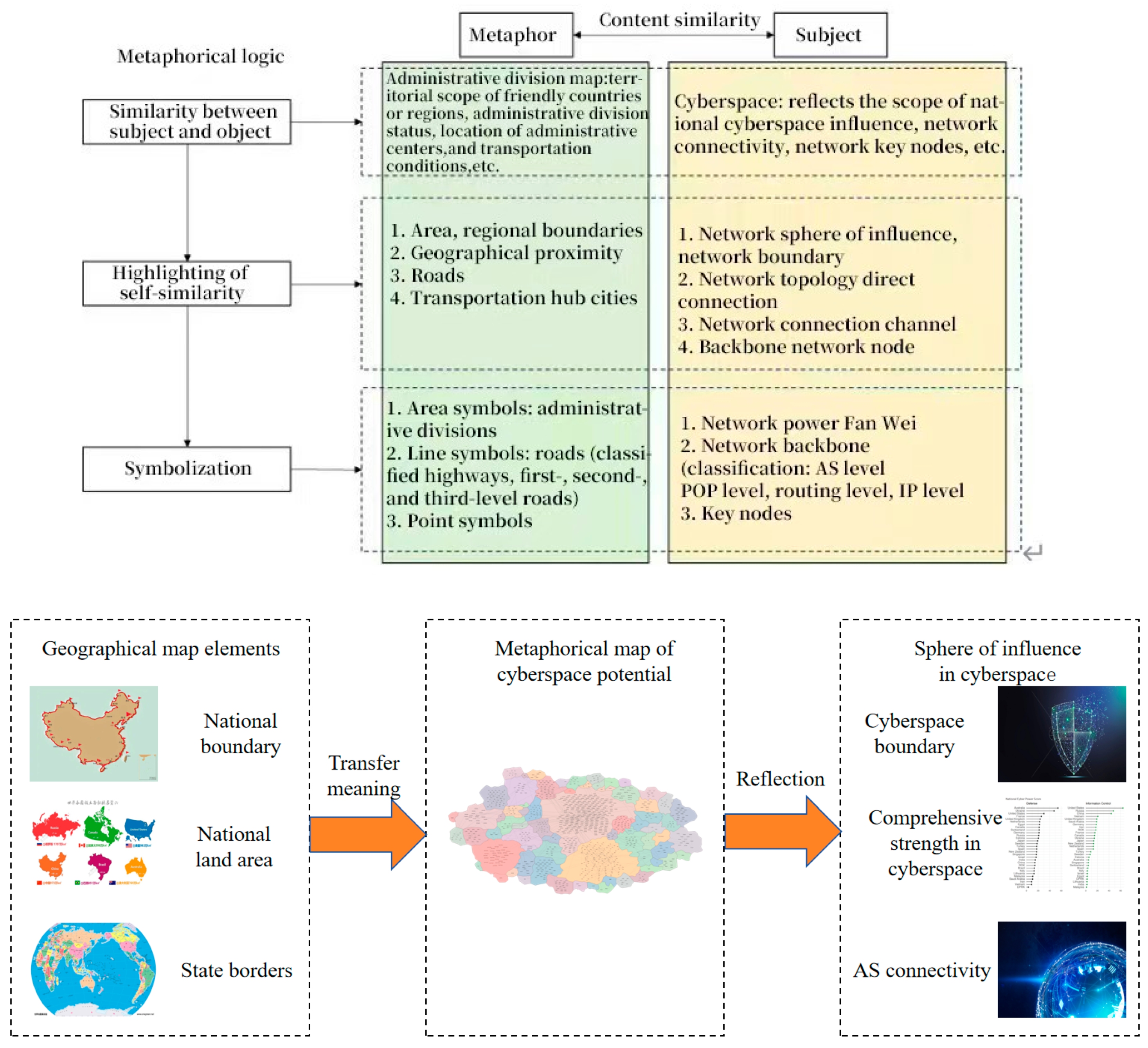

2. Research Approach

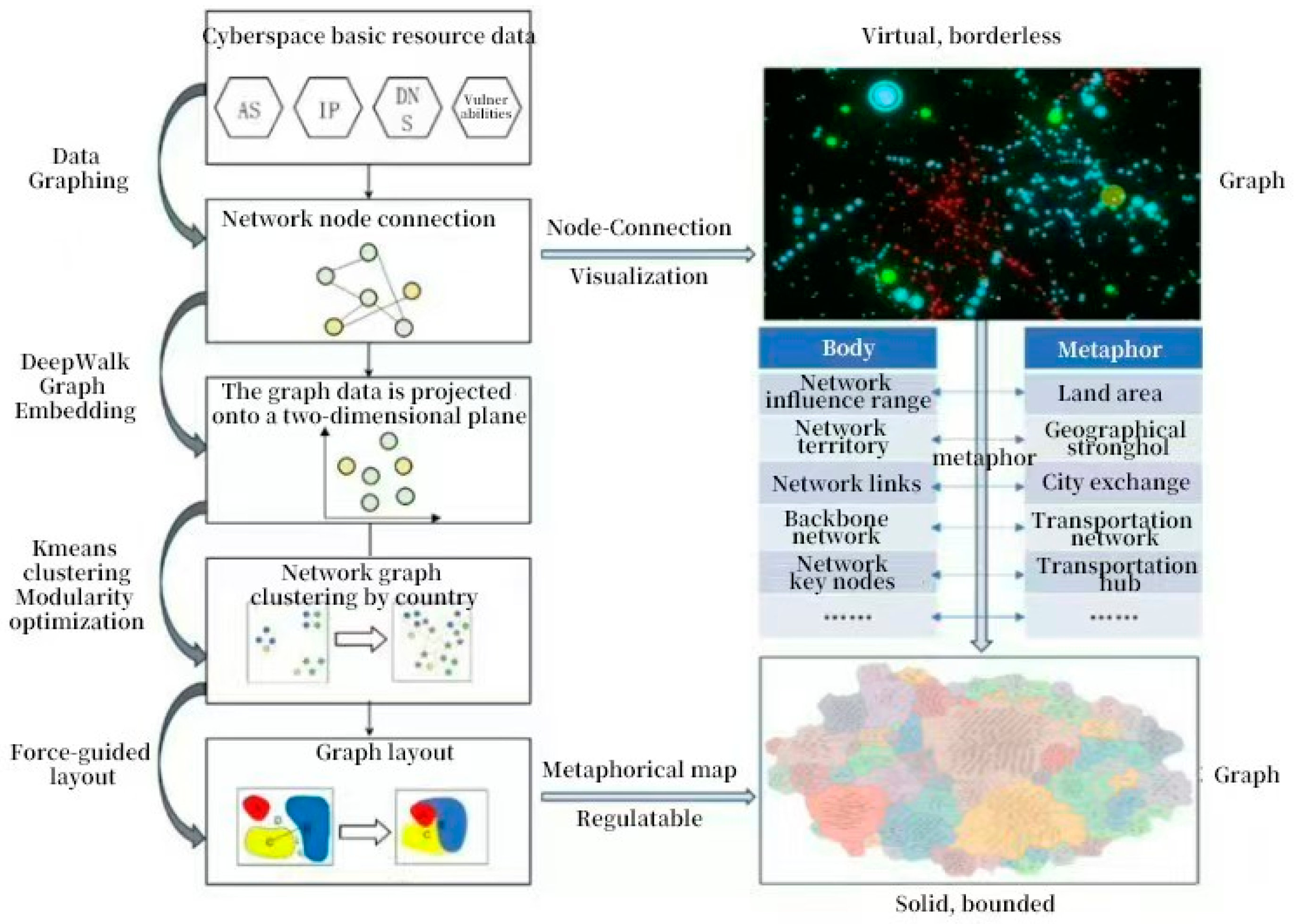

3. Materials and Methods

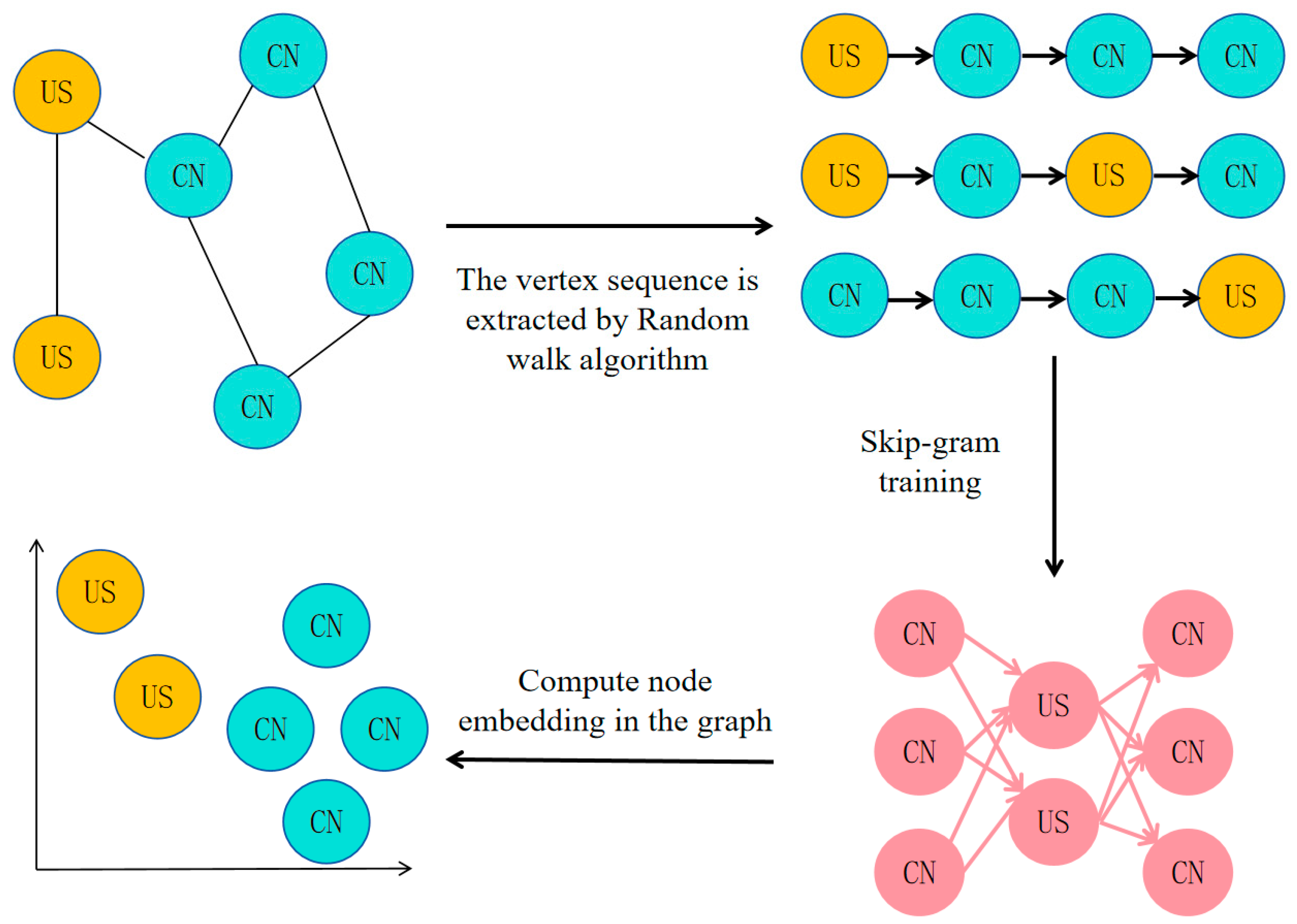

3.1. Graph Embedding in Cyberspace Data

| Algorithm 1: AS Connection Data Graph Embedding |

| Input: AS connection graph G (V, E) |

| Window size ω |

| Output dimension d |

| Number of paths starting from each node γ |

| Length of each path t |

| Output: Matrix representing hidden information Φ∈R∣V∣×d |

| 1. Randomly initializeΦ |

| 2. Construct Hierarchical Softmax |

| 3. Perform γ random walks for each node |

| 4. Shuffle the nodes in the network |

| 5. Generate random walks of length t starting from each node |

| 6. Update parameters using the skip-gram model with gradient methods based on the generated random walks |

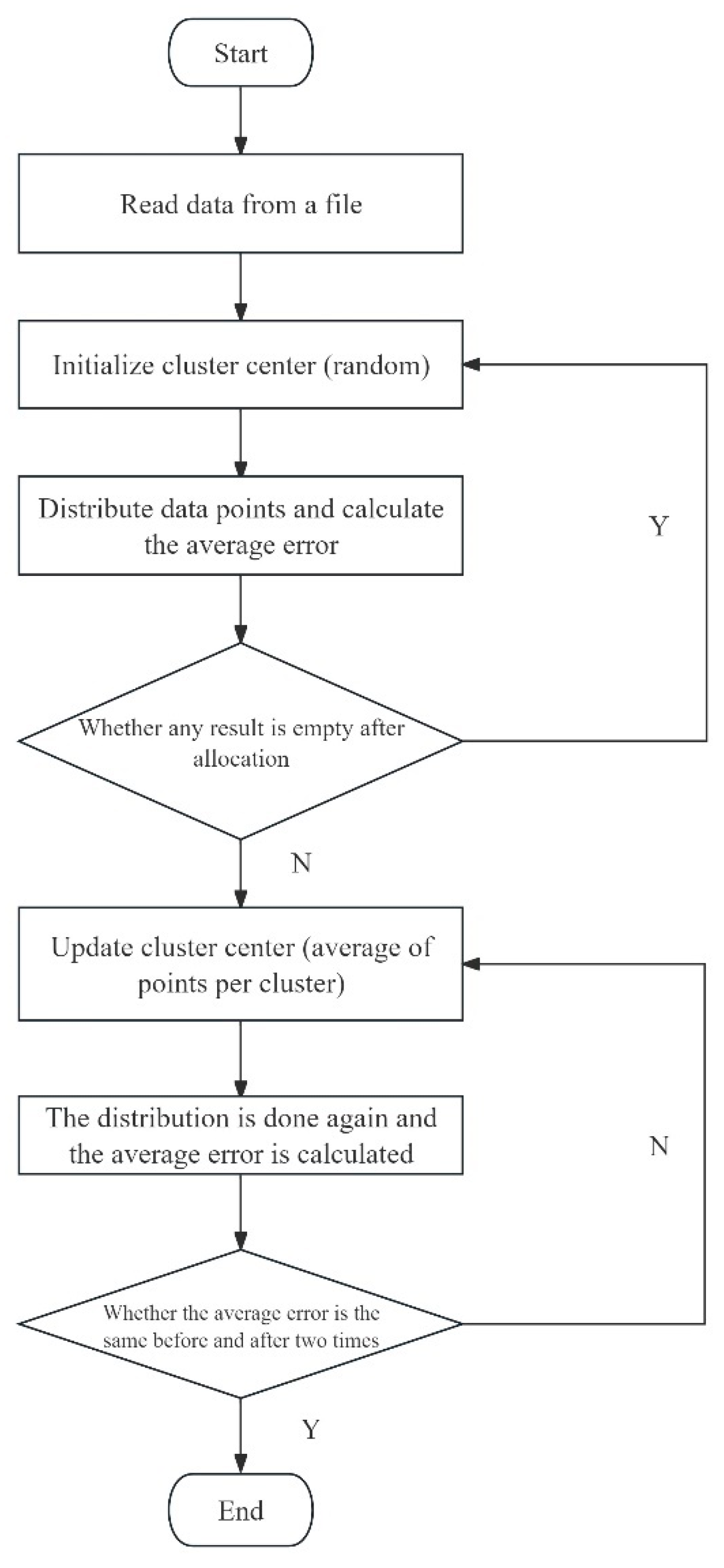

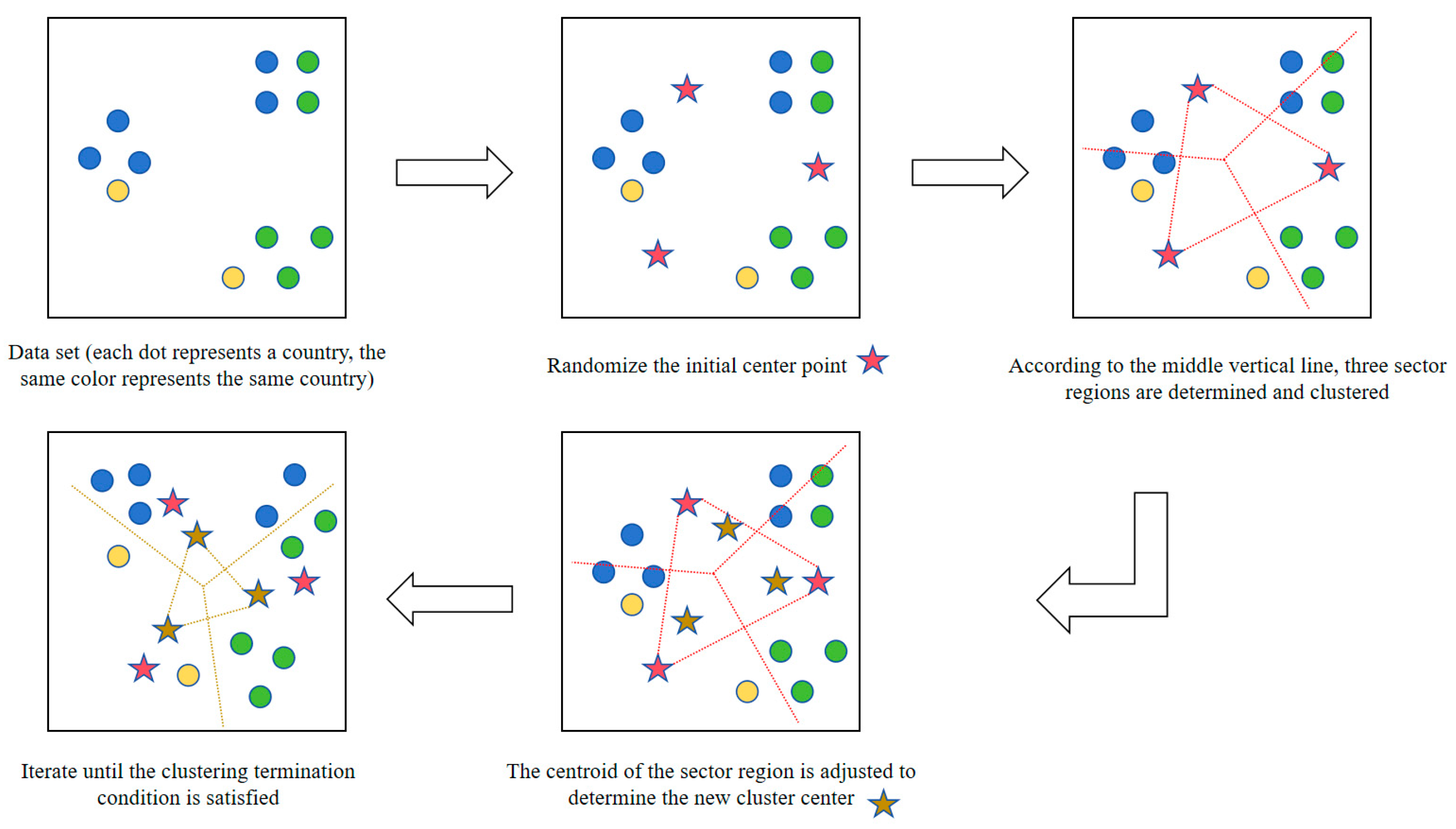

3.2. Cyberspace Graph Clustering Algorithm

3.2.1. Country AS Clustering Based on K-means

3.2.2. National Node Modularity Optimization Algorithm

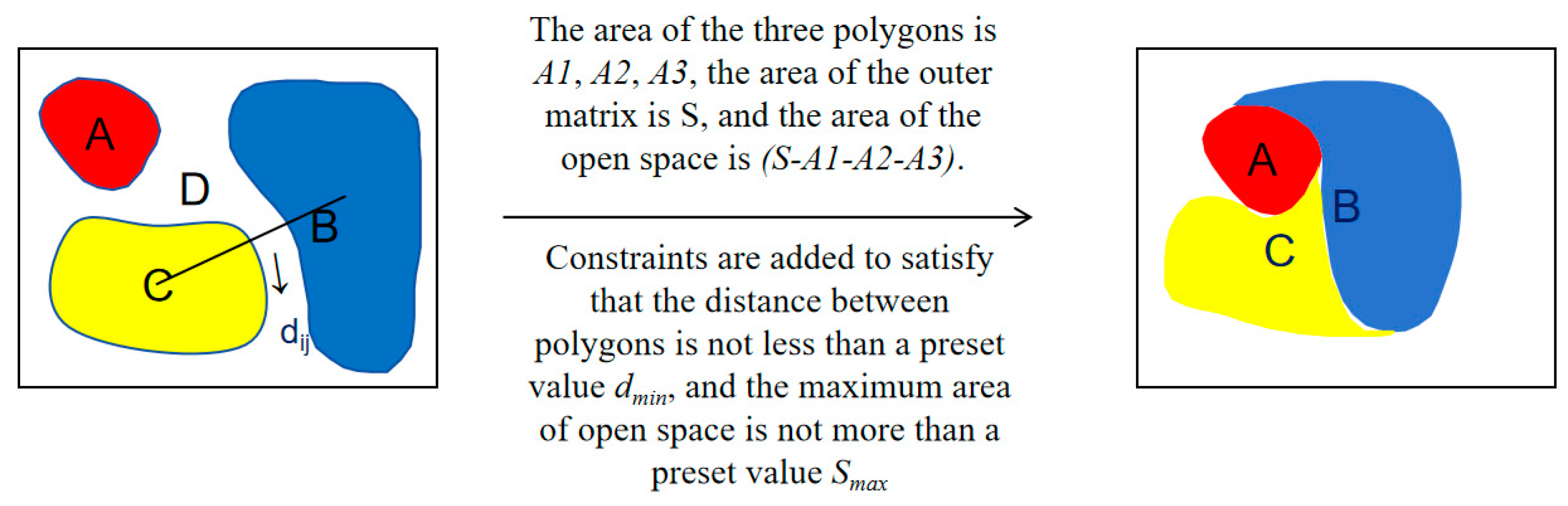

3.3. Spatial Layout Algorithm of Comprehensive Cyber Potential Indicators

3.3.1. Construction of the Cyber Potential Indicator System

3.3.2. Force-Directed National Network Potential Map Layout

- The minimum distance between polygons is no less than a preset value dmin;

- The maximum area of vacant land does not exceed a preset value Smax;

- The area of each polygon after updating the coordinates must equal its original area.

4. Experiment and Discussion

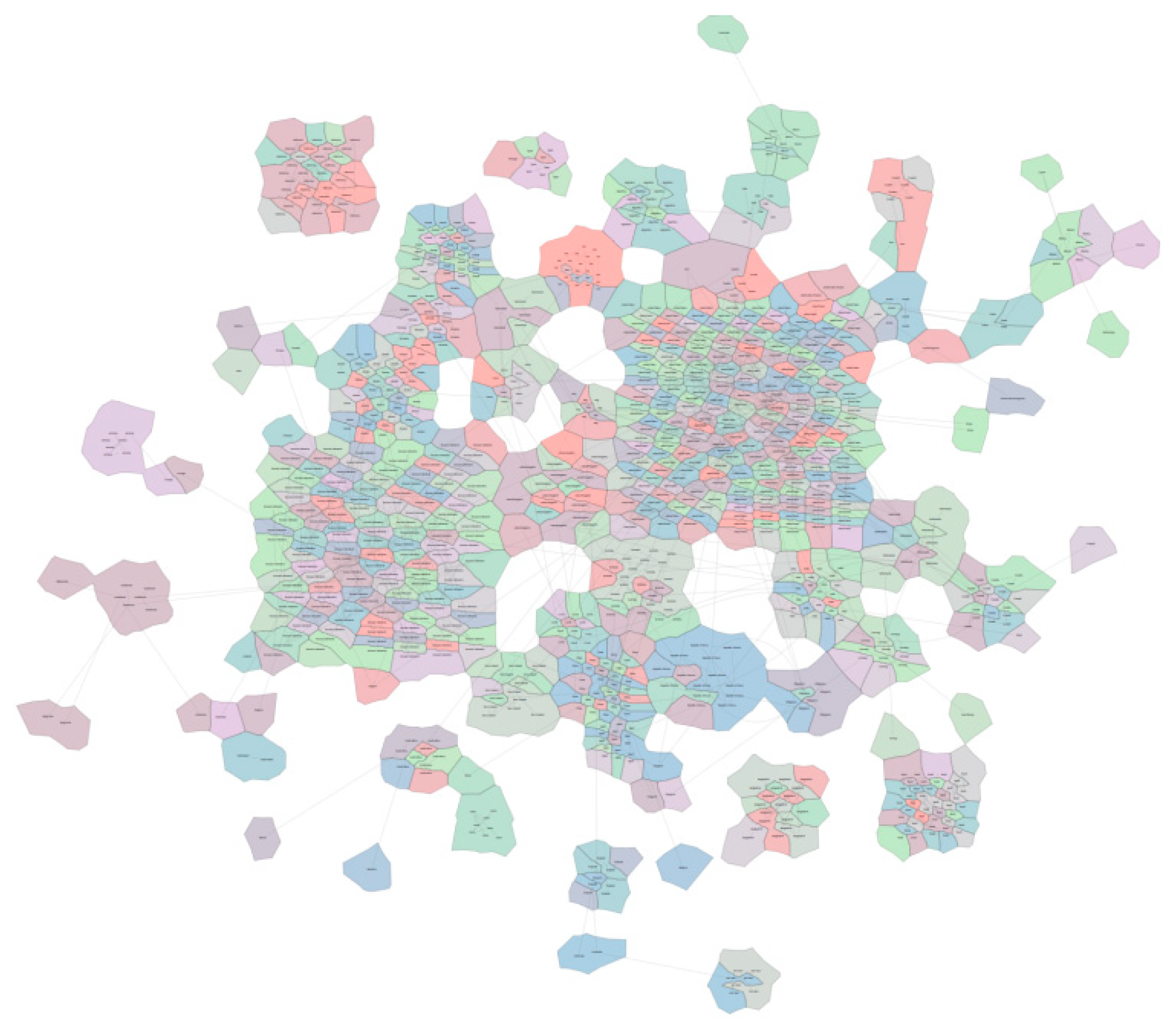

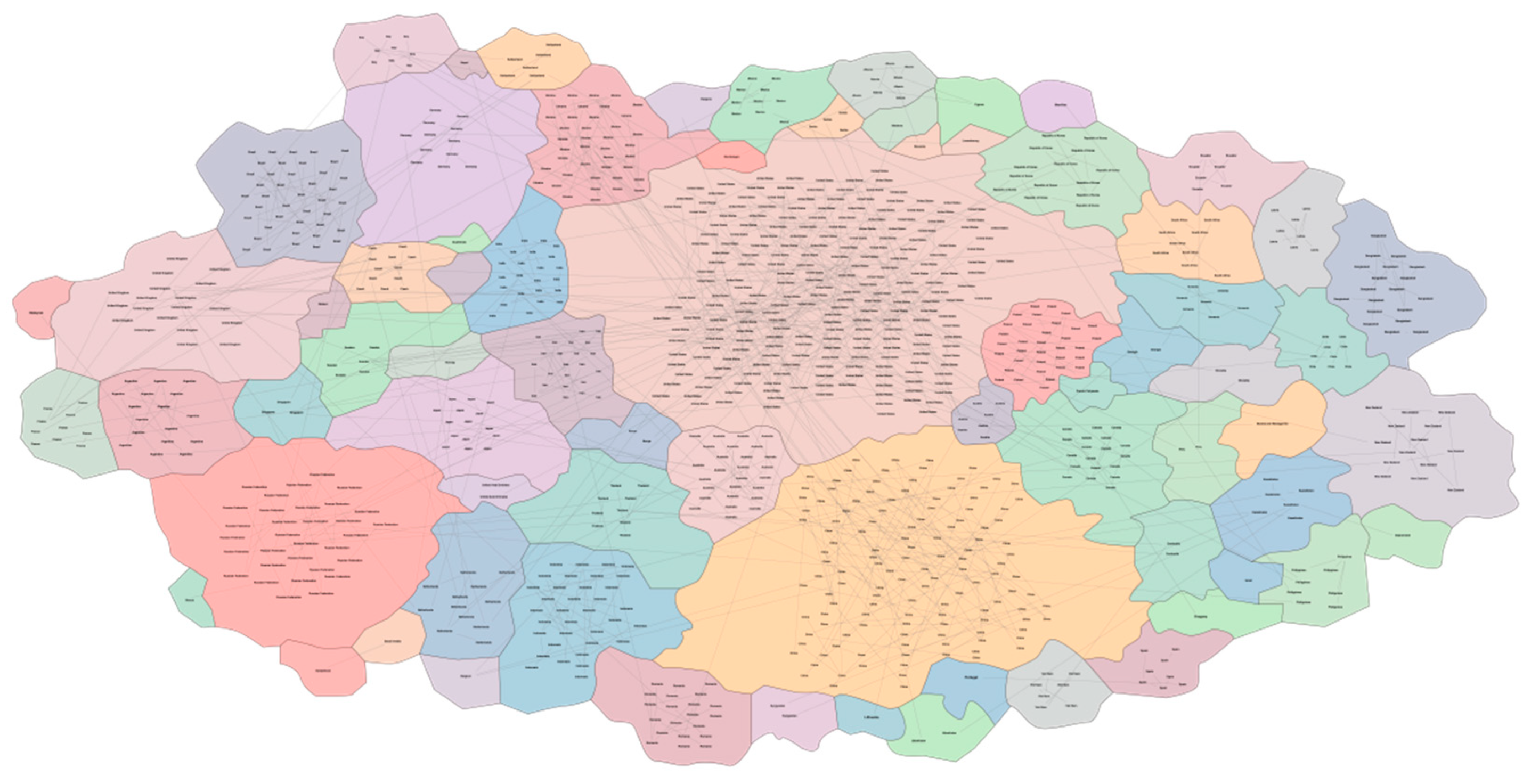

4.1. Experiment on Building a Cyber Potential Metaphor Map

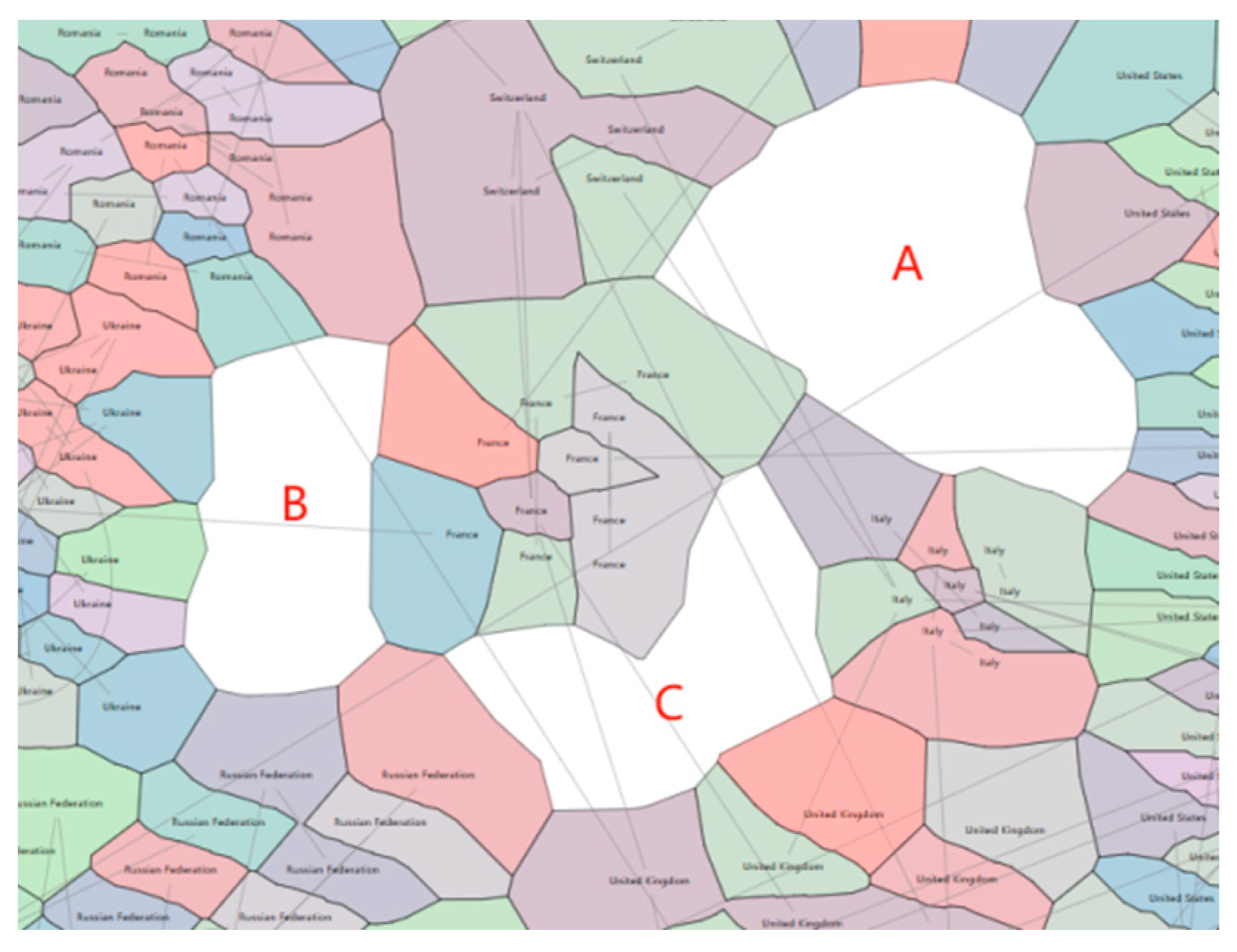

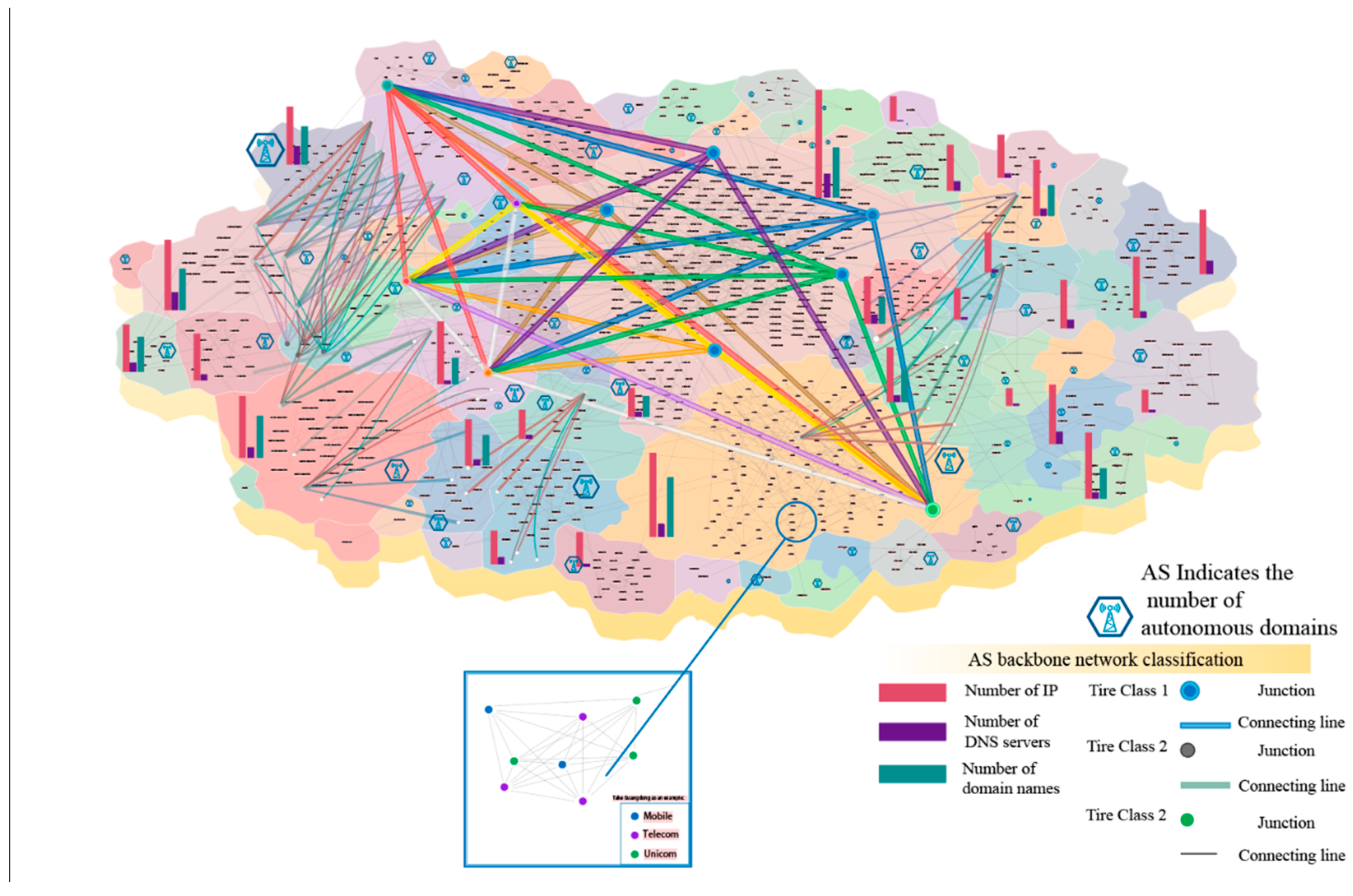

4.3. Visualization Results of Cybers Potential Metaphor Map

4.4. Experimental Analysis

4.4.1. Analysis of Cyberspace Sphere of Influence and Links

4.4.2. Thematic Information Expression Based on the Cyber Potential Basemap

5. Conclusions and Prospects

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, Q.S.;Luo, X.Y.; Zhao, H.P. Cyberspace map tightly coupled with geographical space. J Cyber Sec 2018, 3, 63–72. [CrossRef]

- Tsou, M.H. Mapping cyberspace: Tracking the spread of ideas on the internet//25th International Cartographic Conference; Paris. Available online: http://icaci.org/files/documents/ICC_proceedings/ICC2011/Oral Presentations PDF/D3-Internet, web services and web mapping/CO-354.pdf.2011.

- Tsou, M.H.; Kim, I.H.; Wandersee, S.; Lusher, D.; An, L.; Spitzberg, B.; Gupta, D.; Gawron, J.M.; Smith, J.; Yang, J.A.; et al. Mapping ideas from cyberspace to realspace: Visualizing the spatial context of keywords from web page search results. Int J Digit Earth 2014, 7, 316–335. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.Y.; Tsou, M.H.; Clarke, K.C. Revisiting the death of geography in the era of Big Data: The friction of distance in cyberspace and real space. Int J Digit Earth 2018, 11, 451–469. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.A.; Tsou, M.H.; Spitzberg, B.; et al. Mapping spatial information landscape in cyberspace with social media. CyberGIS Geospatial Discov Innov 2019, 71–86. [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.X.; Taneja, H. Reimagining internet geographies: A user-centric ethnological mapping of the World Wide Web. J Comput Mediated Commun 2016, 21, 230–246. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Chi, F.; Wang, R.; Han, B.; Wu, S.F.; Han, R.L. Comparison of realistic geo-space and virtual cyberspace in China. Sci Geogr Sin 2008, 05, 601–606.

- The Internet Map[EB/OL], 2024-05-21. Available online: http://internet-map.net/.

- Holmquist, L.E.; Fagrell, H.; Busso, R. Navigating cyberspace with cybergeo maps//Proceedings of IRIS, 1998; Vol. 21.

- Chen, S.; Li, S.H.; Chen, S.M.; Yuan, X. R-map: A map metaphor for visualizing information reposting process in social media. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 2020, 26, 1204–1214. [CrossRef]

- Wise, J.A.; Thomas, J.J.; Pennock, K.; Lantrip, D.; Pottier, M.; Schur, A.; Crow, V. Visualizing the non-visual: Spatial analysis and interaction with information from text documents. Proceedings of the Visualization 1995 Conference; IEEE Publications, 2009; pp. 51–58. [CrossRef]

- Xin, R.; Ai, T.H.; He, Y.K. Visualisation and analysis of nonspatial hierarchical data of gasper map. Acta Geod Cartogr Sin 2017, 46, 2006–2015. http://xb.chinasmp.com/EN/10.11947/j.AGCS.2017.20160596. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, G.; Fu, Z. Nonlinear Least Squares Phase Unwrapping Based on Topographic Slopes. Geogr Inf Sci 2013, 15. [CrossRef]

- Qi, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Li, Q.X. Metaphor representation of resource nodes in cyberspace based on local Moran index and PageRank algorithm[J]. QiK. Geogr Inf Sci 2024.

- Voo, J.; Hemani, I.; Cassidy, D. National Cyber Power Index 2022[R]; Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard University: MA, 2022.

- In Global Cybersecurity Index 2021[R]; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, 2021; 16. Global Cybersecurity Index 2021[R]; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, 2021.

- Network Readiness Index [Report][R].Commonwealth of Virginia: Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2015.

- In Cyber Power Index[R]; Economist Intelligence Unit, Booz Allen Hamilton: Chicago, 2011; 18. Cyber Power Index[R]; Economist Intelligence Unit, Booz Allen Hamilton: Chicago, 2011.

- Su, C. Study on International Law of Cyberspace Governance[D]; Heilongjiang University: Harbin, 2021.

- Leetaru, K.; Wang, S.; Cao, G.; Padmanabhan, A.; Shook, E. Mapping the global Twitter heartbeat: The geography of Twitter. First Monday 2013. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.L. Metaphor and Cognition; Peking University Press: Beijing, 2004.

- Women, L.G. Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2008.

- Ventalon, G.; Erjavec, G.; Tijus, C. Processing visual metaphors in advertising: An exploratory study of cognitive abilities. J Cogn Psychol 2020, 32, 816–826. [CrossRef]

- Su, S.L.; Wang, L.Q.; Du, Q.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Kang, M.J.; Weng, M. Fundamental theoretical issues of metaphorical map[J/OL]. Geogr Inf Sci 2022, 1–13.(2022-12-29).

- Wu, C.; Chen, M.; Zhou, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, W. Identifying the spatiotemporal patterns of traditional villages in China: A multiscale perspective. Land 2020, 9, 449. [CrossRef]

- Li, A. Study on Combination and Transfer Between High-Speed Railway and Urban Rail Transit[D]; Beijing Jiaotong University: Beijing, 2011.

- Zhang, L.; Wang, G.X.; Jiang, B.C.; Zhang, L.T.; Ma, L. A review of visualization methods of cyberspace map. Geom Inf Sci Wuhan Univ 2022, 47, 2113–2122. [CrossRef]

- Gansner, E.R.; Hu, Y.; Kobourov, S.G. Gmap: Drawing graphs as maps. Graph Drawing: 17th International Symposium, GD 2009, Chicago, USA, Sep 22–25, 2009. Revised Papers 17; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 405–407.

- Gansner, E.R.; Hu, Y.; Kobourov, S. GMap: Visualizing graphs and clusters as maps IEEE Pacific Visualization Symposium (PacificVis); IEEE Publications, 2010; Vol. 2010; pp. 201–208. [CrossRef]

- Gansner, E.R.; Gansner, E.R.; Kobourov, S.G. Visualizing graphs and clusters as maps. IEEE Comput Graph Appl 2010, 30, 54–66. [CrossRef]

- Kobourov, S.G.; Pupyrev, S.; Simonetto, P. Visualizing graphs as maps with contiguous regions. Eurovis (Short Pap), 2014.

- Mashima, D.; Kobourov, S.G.; Hu, Y. Visualizing dynamic data with maps. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 2012, 18, 1424–1437. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Kobourov, S.; Huroyan, V. Browser-based hyperbolic visualization of graphs 15th Pacific Visualization Symposium (PacificVis); IEEE Publications; IEEE Publications, 2022; Vol. 2022; pp. 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Ferrara, E. Graph embedding techniques, applications, and performance: A survey. Knowl Based Syst 2018, 151, 78–94. [CrossRef]

- Perozzi, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Skiena, S. Deepwalk: Online learning of social representations. Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2014; pp. 701–710. [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Leskovec, J. node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2016, 2016, 855–864. [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, 1967; Vol. 1; pp. 281–297.

- Newman, M.E.J. Fast algorithm for detecting community structure in networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 2004, 69, 066133. [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006, 103, 8577–8582. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y. Discussion on the Interaction Between Geo-potential and Bilateral Relations——Take China and the United States INTHE 10 ASEAN Countries as an Example[D]; Yunnan Normal University: Kunming, 2021.

- Sun, H.J. On division of weight and weighting approach. J Dongbei Univ Fin Econ 2009, 04, 3–7.

- Wang, X.M. Analysis of Geo-potential on Countries Involved in the South China Sea Disputes[D]; Liaoning Normal University: Dalian, 2015.

- Altman, E.I. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J Fin 1968, 23, 589–609. [CrossRef]

- Fruchterman, T.M.J.; Reingold, E.M. Graph drawing by force-directed placement [Software]. Softw Pract Exp 1991, 21, 1129–1164. [CrossRef]

- Global National and Regional IP Address Segments[EB/OL], 2024-05-21. Available online: http://ipblock.chacuo.net/.

- Index Mundi[EB/OL], 2024-05-21. Available online: https://www.indexmundi.com/.

- What is an IP address? How Does It Work?[EB/OL], 2024-05-21. Available online: https://www.fortinet.com/resources/cyberglossary/what-is-ip-address.

- Clark, D. The design philosophy of the DARPA Internet protocols. Symposium Proceedings on Communications architectures and protocols, 1988; pp. 106–114. [CrossRef]

- Ramdas, A.; Muthukrishnan, R. A survey on DNS security issues and mitigation techniques International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICCS); IEEE Publications, 2019; Vol. 2019; pp. 781–784. [CrossRef]

| Key Factor | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Cyberspace technical strength | Number of national IPs and ASN quantities. |

| Cyberspace security capability | Number of vulnerabilities in the national network. |

| International cooperation and diplomacy | Number of AS connections in the country. |

| Economic strength | Gross domestic product (GDP), trade volume, and foreign exchange reserves. |

| Military strength | Number of armed forces personnel and military expenditure as a percentage of GDP. |

| Population size | Population size |

| Technological level | Number of scientific journal articles, patent applications, education penetration rate, and high-tech industry export value. |

| Primary Index | Weight | Secondary Index | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyberspace Strength | 0.7 | IP number | 0.54920074 |

| AS Indicates the number of autonomous domains | 0.05655169 | ||

| Number of DNS servers | 0.04153054 | ||

| Number of domain names | 0.14566287 | ||

| Internet penetration | 0.11279529 | ||

| Number of secure Internet servers | 0.05280177 | ||

| Number of vulnerabilities | 0.0414571 | ||

| Overall Strength | 0.3 | GDP | 0.73004571 |

| Land area | 0.26995429 |

| Index | Unit | Time |

|---|---|---|

| IP number | Pct | 2023.7.25 |

| AS Indicates the number of autonomous domains | Pct | 2023.7.25 |

| Number of DNS servers | Pct | 2023 |

| Number of domain names | Pct | 2023.7.24 |

| Internet penetration | Percentage | 2021 |

| Number of secure Internet servers | Per million people | 2020 |

| Number of vulnerabilities | Percentage (1-%) | 2023 |

| GDP | Millions of dollars | 2022 |

| Land area | Square kilometer | 2023 |

| Country | Abbreviation | National Power Index |

|---|---|---|

| America | US | 0.840193361497829 |

| China | CN | 0.474704594839867 |

| Russia | RU | 0.239512198050437 |

| Germany | DE | 0.229205405352285 |

| Britain | GB | 0.210031567851877 |

| Brazil | BR | 0.182482279811081 |

| Canada | CA | 0.177795046596043 |

| Japan | JP | 0.165668826464713 |

| Australia | AU | 0.15929862114969 |

| France | FR | 0.14068317053891 |

| Ranking | Network Comprehensive Strength | NCPI Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | America | America |

| 2 | China | China |

| 3 | Russia | Russia |

| 4 | Germany | Britain |

| 5 | Britain | Australia |

| 6 | Brazil | Netherlands |

| 7 | Canada | Korea |

| 8 | Japan | Vietnam |

| 9 | Australia | France |

| 10 | France | Iran |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).