1. Introduction

Pediatric neuroimaging plays a pivotal role in diagnosing and managing neurological conditions affecting children with cancer. As technological advancements, particularly in artificial intelligence (AI), continue to reshape medical practices, it becomes imperative to assess the evolving landscape of AI applications in this specialized field. Children present unique challenges due to ongoing brain development, distinct pathologies, and the necessity for child-friendly imaging protocols. Clinicians often face practical challenges such as limited imaging time due to patient discomfort and the need for sedation, which can impact image quality and diagnostic accuracy. From an AI expert’s perspective, technological limitations include the scarcity of large, high-quality datasets specific to pediatric populations, which hampers the development of robust AI models.

Patients and their families are central to this discussion. Improved diagnostic tools can lead to earlier detection, less invasive procedures, and more personalized treatments, significantly impacting patient experiences and outcomes. Therefore, integrating AI into pediatric neuroimaging is not just a technological advancement but a patient-centric imperative.

This review aims to address the scarcity of comprehensive assessments focusing on the intersection of AI, neuroimaging, and pediatric cancer, providing an understanding of the current state, potential applications, and limitations in this evolving field. In the landscape of pediatric neuroimaging, this review stands apart by directing its focus toward a specific and critical realm — AI applications in neuroimaging for pediatric cancer. While existing reviews offer comprehensive insights into general pediatric neuroradiology [

1,

2,

3,

4], our manuscript takes a distinctive approach, homing in on the unique challenges and advancements within the realm of catastrophic conditions in pediatric patients. This focus allows us to unravel intricacies, highlight advancements, and identify opportunities that are particularly pertinent to the complex landscape of pediatric cancer.

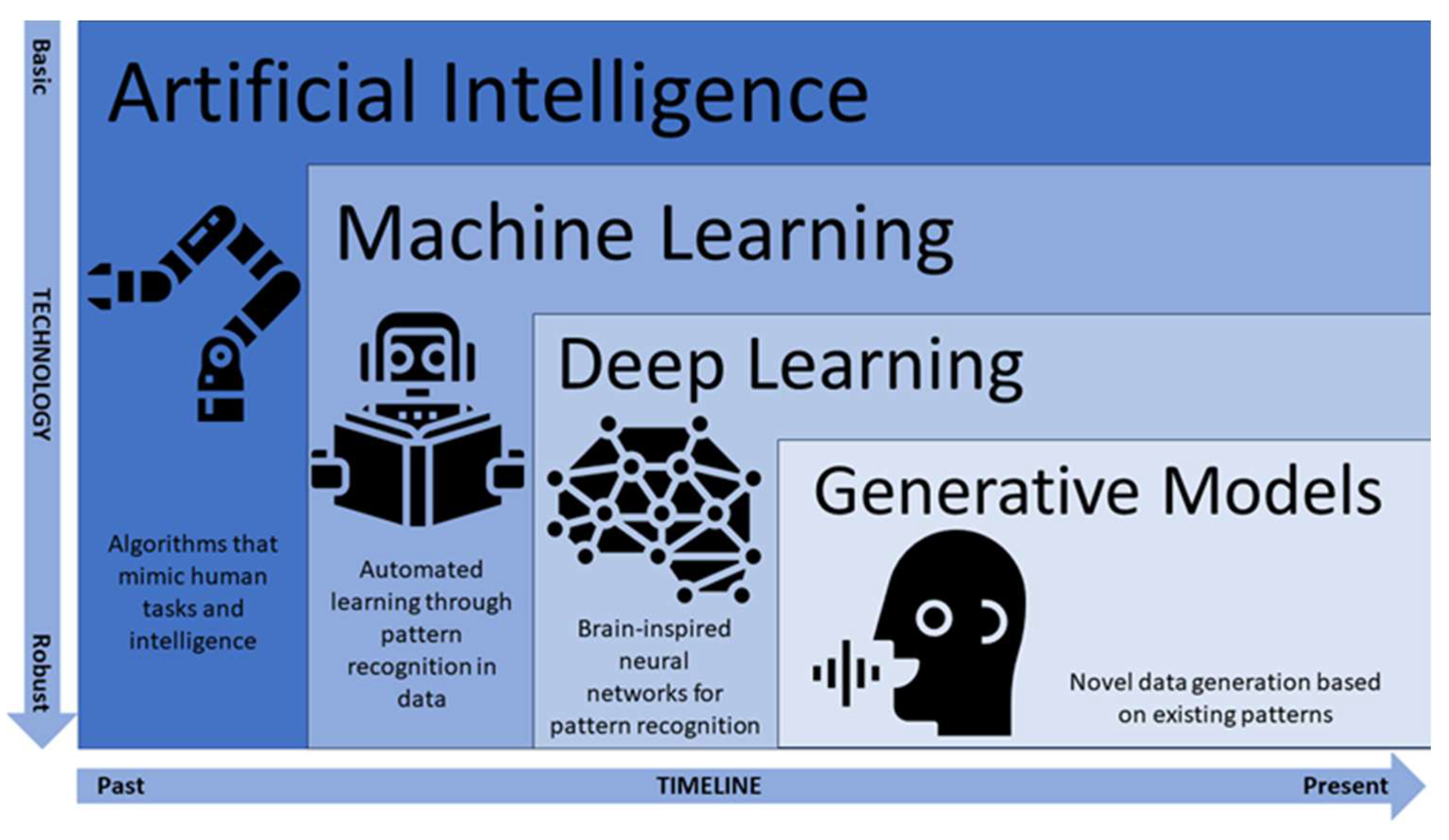

AI refers to the computational automatization of tasks that mimic human intelligence. AI may even surpass human intelligence in areas such as memory storage, working memory capacity, parallel multitasking, steadfast decision-making criteria, pattern and recognition, among others [

5]. Machine learning is a sub-branch of AI that enables a computational, automatized system to learn, make decisions, and adapt itself to perform new tasks based on newly imputed data without being explicitly programmed for those new tasks [

6]. The predictive accuracy of the machine’s algorithm can then be assessed by comparing the outputs produced to actual outcomes obtained with a new data set that was not used for training [

7]. Machine learning can be categorized as supervised, unsupervised, reinforcement learning, or evolutionary. In supervised learning, algorithms are trained on labeled data for which the input and corresponding output are provided, and the goal is to learn a mapping between inputs and outputs [

8]. This category includes classification, regression, and time series forecasting. In unsupervised learning, algorithms are trained on unlabeled data, and their goal is to discover patterns and structures within the data without specific guidance [

9]. This category includes clustering, dimensionality reduction, and anomaly detection. In reinforcement learning, agents interact with an environment and learn to take actions to maximize a cumulative reward, which guides them toward achieving specific goals [

10]. This category includes model-based, model-free, and deep learning. As a more recent type of machine learning, deep learning incorporates artificial neural networks that simulate the learning process and structure of the human brain (

Figure 1). In evolutionary learning, the concepts of natural selection are represented in code to iterate a population of “organisms” to obtain an optimal solution. The steps involved in evolutionary learning are parent selection, progeny generation, and population evaluation [

11].

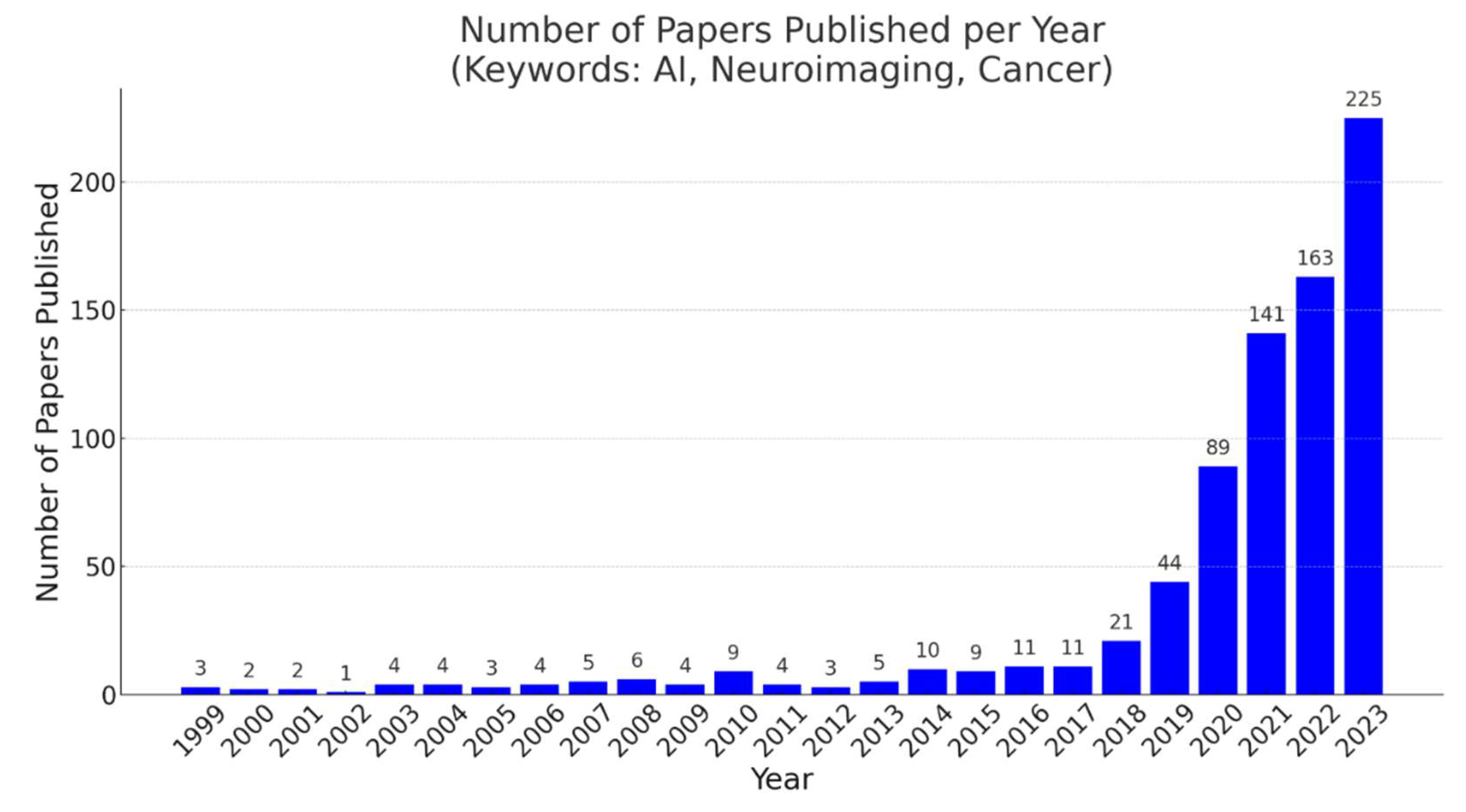

The use of artificial intelligence in pediatric neuroimaging has increased in recent years (

Figure 2). Some common deep learning algorithms applied in neuroimaging include convolutional neural networks (CNNs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and autoencoders. CNNs are deep learning approaches consisting of multiple neural layers [

12]. When a volume of a sample, for example, three-dimensional (3D) images, is used as input data to train a CNN, the developed network is a 3D-CNN. Recently, 3D-CNNs have been used to identify patterns in neuroimaging data [

13]. AlexNet, with deeper and stacked convolutional layers [

14], and GoogLeNet, with 22 layers developed by Google researchers [

15], are CNN models commonly used in object detection and image classification. Moreover, the residual neural network (ResNet), which is also a CNN architecture containing deeper layers that learn residual functions with reference to the input layer [

16], has gained popularity in image recognition after AlexNet and GoogLeNet. Conversely, GANs can be especially applicable when the training data is limited, because they can create new data resembling the training data. A typical GAN has two components: a generator (a neural network that learns to generate data) and a discriminator (a classifier that can tell how “realistic” the generated data are). Autoencoders are effective at reconstructing images because they are feedforward neural networks that are trained to first encode the image then transform it to a different representation and eventually decode it to generate a reconstructed image. Autoencoders are a special subset of encoder–decoder models with identical input and output domains.

Neuroimaging is a branch of medical imaging that maps the brain in a non-invasive manner to understand its structural, functional, biochemical, and pathological features. Neuroimaging has led to significant advances in diagnosing and treating neurological abnormalities. Some neuroimaging modalities are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (which includes functional, structural, diffusion, angiographic, and spectroscopic imaging), electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), positron emission tomography (PET), and computed tomography (CT). Functional neuroimaging refers to imaging the brain while participants perform set tasks to study task-related functions of the brain, rather than its structure.

Recently developed deep learning algorithms can perform object segmentation and recognition in a short time with high accuracy. These algorithms offer the advantages of saving time and optimizing the use of resources. As a result, AI has gradually been integrated into daily medical practice and has made considerable contributions to medical image processing. The realm of neuroimaging has seen substantial integration of AI across various domains encompassing a wide spectrum of functions. This widely encompassing AI use spans improving radiology workflow [

17], real-time image acquisition adjustments [

18], image acquisition enhancement [

19], and reconstruction tasks such as bolstering image signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs), refining image sharpness, and expediting reconstruction processes [

20]. AI has also found applications in noise-reduction efforts [

21], postprocessing of images, predicting specific absorption rates [

22], prioritizing time-sensitive image interpretations [

23], predicting and classifying types and subtypes of brain lesions based on molecular markers [

24,

25], and tissue characterization [

26,

27,

28], as well as in anticipating treatment responses [

29,

30] and survival outcomes [

31]. Importantly, these AI applications serve to elevate the efficiency of individual neuroscientists and physicians, optimize departmental workflows, enhance institutional-level operations, and ultimately enrich the experiences of pediatric patients and their families.

As AI has demonstrated considerable usefulness and potential in neuroimaging, applying AI to pediatric neuroimaging for cancer could have a significant impact on patient outcomes and healthcare. AI holds immense promise in elucidating and addressing challenges in pediatric neuroimaging. Pediatric cancer encompasses many severe and life-threatening conditions that affect children from infancy through adolescence. This disease is characterized by its devastating impact on a child’s overall health, development, and well-being [

32]. Children with cancer may experience chronic pain, physical disabilities, cognitive impairments, and disruptions of their normal growth and development [

33]. The pediatric cancer addressed in this review include craniopharyngioma, low-grade glioma (LGG), and medulloblastoma.

Pediatric cancers and their treatments are often associated with cognitive impairment. Craniopharyngioma is a common, mostly benign, congenital tumor of the central nervous system that typically causes disturbances of the visual system [

34]. Although pediatric patients with craniopharyngioma display intact intellectual functioning, impairments of memory, executive function, attention, and processing speed have been observed [

35,

36].

Gliomas, which develop from the glial cells of the brain [

37], are categorized into four grades: grade I and II gliomas are classified as low-grade gliomas (LGGs), whereas grade III and IV gliomas are classified as high-grade gliomas (HGGs) [

38]. Neurocognitive deficits in children with LGGs can range from memory impairment and attention problems to decreased processing speed, depending on the location of the glioma [

39].

Medulloblastoma is a malignant, invasive embryonal tumor that originates in the cerebellum or posterior fossa and spreads throughout the brain via the cerebrospinal fluid [

40]. Survivors of medulloblastoma exhibit a decrease of 2–4 IQ points per year over time [

41], in addition to deficits in attention, processing speed, and memory.

The unique characteristics of the developing pediatric brain introduce complexities that necessitate tailored approaches for accurate diagnoses and effective treatment strategies. This review aims to explore the evolving landscape where AI intersects with pediatric neuroimaging, emphasizing the distinctive considerations and challenges inherent to the pediatric population. As we delve into the intricacies of AI applications in pediatric neuroimaging, it is crucial to recognize that this field necessitates a multidisciplinary understanding. Clinicians, neuroimaging specialists, and AI experts converge to navigate the complexities posed by the developing brain.

Our objective is to provide insights accessible to AI experts, neuroimaging specialists, and clinical practitioners alike. The convergence of these domains is pivotal for fostering collaborative solutions that enhance the understanding and treatment of pediatric neurological conditions. By establishing this common ground, we aim to propel the field forward, leveraging the potential of AI in pediatric neuroimaging to improve diagnostics, treatment planning, and outcomes for our young patients.

This review is organized into the following sections: challenges in pediatric neuroimaging, AI for improving image acquisition and preprocessing, AI for tumor detection and classification, AI for functional neuroimaging and neuromodulation, AI for selecting and modifying personalized therapies, and AI applications for specific pediatric diseases, followed by a discussion and conclusions.

2. Challenges in Pediatric Neuroimaging

Navigating the landscape of pediatric neuroimaging is inherently fraught with challenges, each intricately tied to the unique characteristics of the developing brain. AI emerges as a transformative ally, offering tailored solutions to overcome these hurdles and enhance diagnostic precision and treatment efficacy in pediatric populations. Pediatric neuroimaging faces a substantial challenge due to the scarcity of comprehensive datasets specific to this demographic. AI interventions can play a pivotal role in overcoming this limitation through innovative techniques like transfer learning, enabling models trained on larger datasets to be fine-tuned for pediatric applications. Collaborative efforts for data sharing among institutions and research centers further amplify the potential for developing robust AI models.

The diverse and dynamic nature of pediatric brain development introduces a layer of complexity in image analysis. AI algorithms, particularly those equipped with advanced learning capabilities, hold the promise of deciphering intricate patterns associated with different stages of brain maturation. This adaptability ensures that neuroimaging analyses remain attuned to the nuances of evolving pediatric neuroanatomy.

For pediatric neuroimaging to truly benefit patient care, AI applications must extend beyond research settings to real-time clinical relevance. AI-driven tools can expedite data analysis, aiding in early detection, diagnosis, and treatment planning. The development of closed-loop systems, guided by real-time functional imaging data, showcases the potential of AI to dynamically adapt neuromodulation strategies, ensuring personalized and efficient interventions for pediatric patients.

Combining neuroimaging and neuromodulation with AI could be used to mitigate and redress cognitive deficits, as an emerging approach to targeted modulation of the neural network underlying the cognitive deficit. Neuromodulation can be invasive, as with deep brain stimulation (DBS) and spinal cord stimulation, or non-invasive, as with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Neuromodulation can be used to treat neurological abnormalities, such as chronic pain [

42,

43] and tinnitus [

44]. The development of real-time acquisition and display of functional data has enabled functional neuroimaging to be used in neurofeedback studies [

45,

46]. Neurofeedback permits participants in functional imaging studies to self-regulate their neural activity by presenting neural data in real time [

47]. Therefore, neurofeedback, like brain stimulation, enables neural activity to be used as an independent variable when brain activity and behavior are studied. The demonstration of successful neural self-regulation has led to neurofeedback being used to control external devices through brain–machine interfaces [

48].

A major challenge in pediatric neuroimaging is the variability in brain structure, function, and chemistry across ages due to rapid brain development during childhood and adolescence. The developing brain undergoes quick structural and functional changes over time, which presents unique challenges in pediatric neuroimaging. An example is the rapid change in the myelination of brain white matter in early childhood. Pediatric brains are not merely scaled-down versions of the adult brain; there are age-dependent loco-regional variations. Therefore, accurate interpretation of age-related differences requires careful consideration of age-appropriate image acquisition and analysis methods [

49]. The brain changes in shape and white/gray matter composition until the fourth decade of age [

50,

51] as the brain matures. When the brain matures through infancy, new sulci are formed, and older sulci deepen. Fractional anisotropy (FA) values on diffusion MRI increase with developmental age, reflecting the maturation of white matter tracts [

52]. Additionally, the poor gray–white matter myelination contrast in patients younger than 6 months affects the quality of conventional automatic segmentation [

53].

Imaging metrics of normal brain development involve identifying myelination and gyrification patterns in individuals or in a specific population and comparing them to the patterns in the brains of controls of the same age [

54,

55,

56]. Accordingly, age-specific templates and atlases are essential to account for variations in brain morphology across different developmental stages [

57]. Spatial normalization for MRI is based on a standard template that defines a common coordinate system for group analysis. ICBM152 and MNI305 are among the most used templates for adults; however, MNI305 is suboptimal for normalization and segmentation of pediatric brain images because of the previously discussed age-related changes [

57]. Some pediatric templates are available, such as the custom age templates produced by Template-O-Matic [

58] and neonate templates [

59,

60]. However, there is a lack of corresponding atlases for those templates. The Haskins pediatric atlas [

61] labels 113 cortical and subcortical regions, but only 72 brains were used in its development. Longitudinal imaging studies that track brain development over time are essential for understanding neurodevelopmental trajectories and for identifying early signs of neurological disorders. Longitudinal studies provide valuable insights into the dynamic changes in the developing brain and offer opportunities for early interventions [

62].

Another challenge in pediatric neuroimaging is the small sample sizes of the currently available pediatric data. Large sample sizes are essential for robust statistical analyses and generalizability of results. However, recruiting sufficient pediatric participants for neuroimaging studies can be challenging because of consent issues, logistical constraints, and the potential impact of imaging on young patients. Multi-site collaborations and data-sharing initiatives could help address this challenge and enhance the power of pediatric neuroimaging studies [

63]. Integrating data from multiple neuroimaging modalities, such as structural MRI, functional MRI, and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), can provide a comprehensive view of brain development and connectivity. Combining multimodal data enables researchers to examine brain changes at both the macroscopic and microscopic levels, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the developing brain [

64].

The concept of multi-institutional data sharing in the realm of healthcare and medical research is indeed complex and multifaceted. It involves exchanging sensitive information across different organizations, which inevitably gives rise to a range of legal, ethical, and privacy concerns. From a legal standpoint, sharing medical data across institutions often requires navigating a complex web of regulations and compliance standards, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe. These regulations are designed to safeguard patient privacy and data security, making it imperative for institutions to ensure that any data-sharing practices are in strict compliance with these legal frameworks. There are significant ethical considerations surrounding multi-institutional data sharing. These encompass questions related to patient consent, data ownership, and the potential for unintended consequences. Institutions must grapple with issues such as obtaining informed consent from patients for data sharing, ensuring that their rights are respected, and addressing concerns about how their data will be used, especially in research contexts. Moreover, privacy concerns are paramount when sharing medical data. Patient information must be de-identified and protected rigorously to prevent data breaches or the identification of individuals. Striking the correct balance between sharing data for the common good of medical research and preserving individual privacy is a critical ethical challenge. The notion of federated learning holds promises as a potential solution to these barriers [

65]. It operates on the principle of decentralized AI training, whereby machine learning models are developed collaboratively across multiple institutions without the need to centrally pool sensitive data. Instead, the models are trained locally on each institution’s data, and only aggregated model updates are shared, thus preserving data privacy. However, it is important to note that federated learning is still an evolving concept and that it faces its own set of challenges, including technical complexities and standardization issues.

Another concern is the quality of the data recorded from children. Young children may have difficulty remaining still during neuroimaging sessions, leading to motion artifacts in the acquired data. Motion can degrade image quality and compromise the validity of results. Innovative motion correction techniques and child-friendly imaging protocols are needed to mitigate the impact of motion artifacts on pediatric neuroimaging data [

66].

Research involving pediatric populations also raises ethical concerns, particularly regarding informed consent and the vulnerability of child participants. Balancing the potential benefits of neuroimaging research with protecting the rights of children is crucial. Ethical guidelines and careful consent procedures must be implemented to ensure the well-being and privacy of pediatric participants [

67].

AI holds great promise for enhancing the interpretability and utility of pediatric neuroimaging data. Methods such as automated image analysis can aid in identifying subtle brain alterations associated with neurodevelopmental disorders and can facilitate early diagnosis and personalized treatment strategies [

68].

Deep learning neural networks, such as CNN, have proved successful in automatically segmenting infant brains and delineating gray–white boundaries in neonates [

53]. The use of deep learning in segmenting individual cortical and subcortical regions of interest (ROIs) based on features such as local shape, myelination, gyrification patterns, and clusters of functional activation is a promising field for exploration. AI can also be applied to tumor detection, segmentation, and categorization.

Furthermore, AI-based neuroimaging techniques facilitate the integration of multimodal data that combine structural and functional information from various imaging modalities. This fusion of data can enhance the overall understanding of complex neurological conditions in pediatric catastrophic disease patients and survivors and promote a more comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment [

69].

3. AI for Improving Image Acquisition and Preprocessing

The optimization of image acquisition and preprocessing is crucial in neuroimaging, significantly impacting the accuracy and reliability of subsequent analyses. In this section, we delve into the challenges and advancements related to these processes, highlighting the pivotal role of artificial intelligence.

There are multiple challenges and risks associated with pediatric image acquisition, such as motion artifacts, reduced tolerance to scanning durations, and the need for age-specific protocols. AI has emerged as a valuable tool to address these challenges. Automated motion correction algorithms, guided by machine learning, enhance the quality of acquired images by mitigating the impact of motion artifacts, particularly prevalent in pediatric populations. The most critical challenge in this context is scanning time, as most children are unable to stay still, are prone to moving, and cannot bear long scan durations. Owing to the need to re-scan motion-corrupted data, imaging can be a lengthy process. In a pediatric setting, general anesthesia is commonly used to decrease the risk of motion artifacts appearing in the images and in consideration of patient throughput, comfort, and cost. However, ionizing radiation exposure and the side effects of contrast agents have always been a major concern, including among children and their parents. Obtaining high-quality images, ideally with high contrast, good spatial resolution, and high SNRs, is critical to ensure accurate diagnoses and suitable treatment plans. Accordingly, reducing the dose of contrast agents may mean sacrificing image quality and decreasing SNRs.

In addition to the challenges faced during image acquisition, limitations are also encountered in image reconstruction. For example, MR images are acquired in the Fourier or spatial-frequency domain (also known as k-space); hence, image reconstruction is important in transforming the raw data into clinically interpretable images [

70]. An inverse Fourier transform operation is required to reconstruct an image, which is collected based on the Nyquist sampling theorem [

71]. However, because of the considerations regarding minimizing scan time, optimizing patient comfort, and ensuring safety in pediatric populations, only a limited number of measurements are acquired by the scanners, which leads to difficulties in solving the inverse transform [

72]. The fundamental physics, practical engineering aspects, and biological tissue response factors underlying the image-acquisition process make fully sampled MRI acquisitions very slow [

70]. Furthermore, patient motion, system noise, and other imperfections during scanning can corrupt the collected raw data.

AI plays a relevant role in preprocessing steps, encompassing image denoising, normalization, and registration. These processes are essential for creating a standardized and comparable dataset. AI algorithms contribute significantly to noise reduction, enhancing signal-to-noise ratios and subsequently improving the accuracy of downstream analyses. Registration and normalization are critical steps in aligning imaging data across individuals or different imaging modalities. In pediatric neuroimaging, challenges arise due to the dynamic changes in brain anatomy during development. Conventional methods may struggle with the anatomical variability present in pediatric populations, necessitating advanced solutions. Accurate registration and normalization are fundamental for creating population-based templates and atlases, facilitating a common spatial framework for analysis. AI-based registration algorithms, capable of adapting to the unique anatomical features of pediatric brains, contribute to improved spatial normalization, ensuring more precise comparisons across subjects [

73].

3.1. Accelerating Image Acquisition

In MRI, compressed sensing (CS) is used to accelerate scanning and reduce the resources required by acquiring MR images with good in-plane resolution but poor through-plane resolution [

74]. CS assumes that suitably compressed under-sampled signals can be reconstructed accurately [

75] without the need for full sampling. However, this technique limits interpretation to single directions and can introduce aliasing artifacts [

76]. A deep learning–based algorithm called synthetic multi-orientation resolution enhancement (SMORE) has been applied to adult compressed scans in real time to reduce aliasing and improve spatial resolution [

74]. A similar approach can, perhaps, be applied in pediatric MRI to reduce scan time and improve image resolution. Moreover, applying GANs has been shown to improve the SNR of images [

77]. Combining GANs with fast imaging techniques in pediatric neuroimaging could lead to faster image acquisition for children who are unlikely or unwilling to remain still for an extended period. These methods may even reduce the need for general anesthesia and/or sedation [

3].

3.2. Reducing Radiation Exposure or Contrast Doses

A deep learning model based on an encoder–decoder CNN has been applied to generate high-quality post-contrast MRI from pre-contrast MRI and low-dose post-contrast MRI [

78]. The study showed that the gadolinium dosage for brain MRI can be reduced 10-fold MRI while preserving image contrast information and avoiding significant image quality degradation. For CT, deep learning has great potential for image denoising based on its use in realizing low-dose CT imaging for pediatric populations. Chen et al. [

79] trained another encoder–decoder CNN model to learn feature-mapping from low-/normal-dose CT images. This model improved noise reduction when compared with other denoising methods. A deep CNN model using directional wavelets was effective at removing complex noise patterns for low-dose CT reconstruction [

80]. An autoencoder CNN, which was used to train pairs of standard-dose and ultra-low-dose CT images, could filter streak artifacts (i.e., artifacts appearing between metal or bone as a result of beam hardening and scatter) and other noise for ultra-low-dose CT images [

81]. Furthermore, it is possible to interpolate data from one modality with a neural network trained on data from a completely different modality. Zaharchuk [

82] trained a neural network with simultaneously acquired PET/MRI images to improve the resolution of low-dose PET imaging. These developments in deep learning show promise in terms of moving pediatric neuroimaging toward imaging with low or no radiation exposure.

3.3. Removing Artifacts

Accelerated MRI techniques such as CS and parallel imaging offer significant reductions in scan time. However, reconstructing images from the under-sampled data involves computationally intensive algorithms, thus posing a notable challenge because of the high computational costs incurred. Lee et al. [

83] proposed deep ResNets that are much better at removing the aliasing artifacts from subsampled k-space data when compared with current CS and parallel reconstructions. Their deep learning framework provides high-quality reconstruction with shorter computational time than is required for CS methods. In addition to accelerating reconstruction, AI approaches can correct artifacts, such as those arising from MRI denoising [

84] and motion correction [

85,

86] during image acquisition and reconstruction. Singh et al. [

87] built two neural network layer structures by incorporating convolutions on both the frequency and image space features to remove noise, correct motion, and accelerate reconstruction. Deep learning–based approaches have also been investigated to reduce metal artifacts [

88,

89] that are common in CT imaging.

4. AI for Tumor Detection and Classification

In children with cancer predisposition syndromes, surveillance screening increases the chance of early tumor detection and, therefore, the survival rate [

90]. Deep learning algorithms may help in identifying imaging protocols to achieve optimal accuracy for early cancer diagnosis [

91]. Soltaninejad et al. [

92] used CNN for automated brain tumor detection in MRI scans. CNNs have been used to detect and characterize tumors [

93] and to find associations between genotypes and imaging tumor patterns. Machine learning has also been used to classify pediatric brain tumors [

94,

95,

96].

CNNs have the potential to identify the best model for categorizing pediatric brain abnormalities by combining brain features extracted from different mathematically derived measures, such as the spherical harmonic description method (SPHARM) [

97], the multivariate concavity amplitude index (MCAI) [

98], and Pyradiomics [

99]. Moreover, CNNs can help in identifying the best approach for feature selection in pediatric brain data, such as a superpixel technique based on a simple linear iterative clustering (SLIC) method [

92], combining spatial distance, intensity distance, spatial covariance, and mutual information.

4.1. AI in Tumor Segmentation

Early detection and precise classification of brain tumors are important for effective treatment [

100]. The two main types of classification that can be performed based on brain images are classification into normal and abnormal tissues (i.e., whether a tumor is detected in the brain image) and classification into different classes of brain tumor (e.g., low-grade vs. high-grade) [

101].

Segmenting tumors with AI methods has recently attracted much attention as a possible means of achieving more precise treatment. AI accomplishes brain tumor segmentation by identifying the class of each voxel (e.g., normal brain, glioma, or edema). Two main AI methods have been reported in the literature: (1) hand-engineered features used with older classification methods (e.g., support vector machine [SVM] classifiers) and (2) deep learning using CNNs. CNNs and their variations can self-learn from a hierarchy of complex features to perform image segmentation [

102,

103].

4.2. AI in Tumor Margin Detection

Many brain tumors exhibit a distinctively infiltrative nature, which often results in poorly defined tumor margins. Compounding this challenge, the edema surrounding these tumors frequently manifests imaging characteristics similar to those of the tumor itself, further complicating the accurate delineation of the true tumor boundary. The precise identification of this boundary holds immense significance, as it serves as a guiding principle for neurosurgeons aiming not only for gross total resection but also for margin-negative surgery, which is a critical factor in significantly enhancing patient survival rates.

To address this complex issue, advanced MRI techniques and PET have been employed in attempts to refine the delineation of tumor margins, albeit with varying degrees of success. More recently, AIs based solely on MR images or on a combination of MRI and PET data have exhibited potential for substantially improving the accuracy of true tumor margin detection [

65,

104,

105]. This innovative approach represents a significant leap forward in the field of neuroimaging, with the promise of new avenues for enhancing the precision of brain tumor surgery and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

4.3. AI in Tumor Characterization

As high-throughput computing facilitates converting multimodal medical images into mineable high-dimensional data, there has been increased interest in using radiomics and radiogenomics to detect and classify tumors. Radiomics refers to studies or approaches that extract quantitative high-throughput features, which are usually invisible to the naked eye, from radiographic images [

106,

107], typically with the use of different machine learning techniques to attribute quantitative tumor characteristics. Radiomics has multifaceted applications, with one of its primary roles being tumor diagnosis and classification. By elucidating distinct radiomic signatures, it empowers radiologists to augment diagnostic accuracy and timeliness, in addition to predicting disease trajectories, thereby enabling tailored treatment strategies. By tracking changes in radiomic features over the course of treatment, it can play a pivotal role in evaluating therapeutic efficacy and making timely adjustments when indicated. In oncology, this capability is of paramount importance for optimizing patient outcomes. The true promise of radiomics lies in the realm of personalized medicine, as it integrates imaging data with clinical parameters, genomics, and other patient-specific variables. This convergence provides the foundation for precision medicine by tailoring treatments to individual patients, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes while mitigating adverse effects.

Radiogenomics uses such radiographic image features to detect relationships specifically with genomic patterns [

108]. Machine learning–based radiomics offers critical advantages in treating brain tumors that are genetically heterogeneous, and it can provide better predictions by linking genomics to extraordinarily complex imaging phenotypes. For example, predicting a tumor genotype noninvasively and preoperatively can help estimate the chance of survival and the treatment response [

109]. By applying a radiomics model to preoperative MRI, it has been possible to predict key genetic drivers of gliomas [

110,

111,

112,

113].

Applying deep learning in radiomics is helpful in assessing higher-order features to improve the accuracy of prediction of brain tumor progression. Deep learning–based radiomics models have been applied for predicting survival [

114,

115] and for classifying the molecular characteristics [

112,

116,

117] of brain tumors. Taking advantage of the 3D nature of MRI data, Casamitjana et al. [

118] and Urban et al. [

119] showed that a 3D-CNN could perform well for brain tumor segmentation. In addition, by reusing pre-trained models to learn a similar task (i.e., transfer learning) in deep learning, Yang et al. [

120] predicted glioma grading from pre-surgical T1-weighted, contrast-enhanced images for 113 patients, using the high-performing GoogLeNet and AlexNet softwares. A CNN-based classification system can be used to segment and classify multi-grade brain tumors [

121].

4.4. Radiomics and Radiogenomics for Specific Pediatric Brain Tumors

In the realm of diagnosing and treating pediatric brain tumors, the 2021 World Health Organization classification of central nervous system tumors has underscored the pivotal role of molecular classification. These tumors are currently characterized by using molecular markers. However, the techniques required for such molecular subgrouping, encompassing immunohistochemistry and genetic testing, are often not consistently available and are associated with significant delays, even in well-equipped healthcare settings. These delays introduce complexities into patient care, affecting various aspects ranging from prognosis and surgical strategies to treatment choices and participation in clinical trials. Given this pressing need for a more efficient approach, machine learning methods hold great promise for rapidly and accurately predicting molecular markers in pediatric neuro-oncology practice.

4.4.1. Posterior Fossa Tumors

Posterior fossa tumors represent a challenging group of central nervous system tumors that primarily affect children. Timely and accurate diagnosis is pivotal in determining the appropriate course of treatment. However, the current gold standard for definitive diagnosis necessitates invasive procedures involving tissue collection and subsequent histopathological analysis, which can be burdensome and risky, especially for pediatric patients. Machine learning has emerged as a promising avenue for non-invasive diagnosis, having demonstrated its ability to attain exceptional diagnostic accuracy with an impressive area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUROC) exceeding 0.99, on par with that of experienced pediatric neuroradiologists, in distinguishing among the three most prevalent posterior fossa tumors: astrocytoma, medulloblastoma, and ependymoma [

122,

123]. Using sequential classifiers, radiomics analysis achieved an impressive micro-averaged F1 score of 88% and a binary F1 score of 95% for the classification of WNT-subgroup medulloblastomas and an impressive AUROC curve of 0.98 in distinguishing between group 3 and group 4 medulloblastomas [

124]. These techniques have the potential to make tissue biopsies unnecessary in the future and to lead to better treatments [

125].

4.4.2. Craniopharyngiomas

Craniopharyngiomas have notoriously diverse shapes and types, with corresponding differences in their pathogenesis and malignancy. Manual diagnosis of craniopharyngiomas is time-consuming, and inconsistencies in the results are common [

126]. Such limitations can be overcome by using deep learning methods. Prince et al. [

127] applied deep learning models for CT, MRI, and combined CT and MRI datasets to pinpoint parameters for identifying pediatric craniopharyngioma. They demonstrated high test accuracies and exceptional improvement in the performance of their baseline model. Therefore, AI may help to improve the accuracy of diagnosis. Machine learning has also been used to predict postoperative outcomes in craniopharyngioma [

128,

129].

Mutations in the BRAF and CTNNB1 genes in craniopharyngiomas were predicted by applying radiomics and machine learning to MRI data [

130]. An SVM model identified 11 optimal features with radiological features and was used to predict preoperative craniopharyngioma invasiveness [

131].

4.4.3. Low-Grade Gliomas

As the diagnosis of low-grade glioma (LLG) is clinically challenging, AI has been applied to LGG radiomics research. An SVM achieved better performance in predicting glioma grading when compared with 24 other classifiers [

124]. However, GoogLeNet was reported to perform better than AlexNet in predicting glioma grading from preoperative T1 MRI [

120]. Hybrid approaches also achieved high accuracy in classifying LGG subtypes [

24,

132]. Another approach used a custom deep neural network and MRI data to classify brain tumors as meningiomas, gliomas, or pituitary tumors and subsequently to categorize the gliomas as grade II, III, or IV [

133]. Machine learning techniques using diffusion parameters have been used to predict the progression of optic pathway gliomas [

134].

4.4.4. High-Grade Gliomas

Among the various subtypes of pediatric-type high-grade gliomas, machine learning techniques have found their most extensive application in characterizing diffuse midline glioma H3 K27–altered [

40]. This particular tumor typically affects central brain structures that are nearly always non-resectable, resulting in a high fatality rate. Different machine learning techniques have been developed to predict this specific tumor marker with very high accuracy [

135,

136,

137,

138]. Radiomic analysis based on MRI data also shows promise in predicting progression-free survival among pediatric patients diagnosed with diffuse midline glioma or diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma [

139]. By employing diffusion and perfusion MRI parameters, a novel capability has emerged by which to delineate three spatially discrete tumor microenvironments that could potentially serve as predictive markers for patient outcomes [

140].

4.4.5. Ependymomas

By leveraging radiomic features extracted from T2-weighted MRI and post-contrast T1-weighted MRI through machine learning approaches, it becomes feasible to differentiate between MRI phenotypes corresponding to two distinct types of posterior fossa ependymoma and to identify high-risk individuals within these groups [

22]. Radiomic features can also differentiate supratentorial ependymomas from high-grade gliomas [

141].

4.5. Hybrid Models

Improving the quality of the input data and carefully selecting the most pertinent features are both crucial steps in training AI models to achieve optimal performance. Conventional types of machine Learning algorithms, such as the SVM and K-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithms, are capable of quantifying and visualizing latent information contained within images [

126,

142]. Meanwhile, most recent deep learning algorithms, such as CNN, AlexNet, and GoogLeNet, excel at extracting features to derive comprehensive deep or high-order features [

143]. Hence, hybrid models that use both methods may work better in complex cases with multi-source, heterogeneous medical data. This concept was put into practice through a recent development for classifying brain tumors, leading to improved classification accuracy. In the model, a modified GoogLeNet was employed to extract deep features that were subsequently used to train SVM and KNN classifiers [

144]. By combining radiomics and deep features extracted by a CNN from medical images and selecting the optimal feature subset as input for an SVM, Ning et al. [

145] demonstrated that integrating radiomics and deep features can be used to grade gliomas. Li et al. [

146] used AlexNet to extract features and an SVM for classification to achieve high classification precision for glioblastoma multiforme diagnosis. Raza et al. [

147] proposed a hybrid deep learning model by changing the last five layers of GoogLeNet to 15 new layers, thereby obtaining performance that was better overall than that of other pre-trained models.

5. AI for Functional Imaging and Neuromodulation

Functional imaging is used in brain tumor studies in two major ways: for preoperative mapping and to assess postoperative outcomes. In preoperative mapping, functional imaging helps surgeons to understand the spatial relations between lesions and functional areas and enables surgical planning that reduces long-term neurological deficits [

148]. One retrospective, propensity-matched study found that patients with LGG who underwent preoperative fMRI subsequently underwent more aggressive surgeries when compared with other patients [

148]. Although these surgeries did not significantly change the survival outcomes, non-significant trends of higher postoperative functional improvement were observed in those patients who underwent preoperative fMRI and aggressive surgeries. Postoperative functional imaging studies investigate the functional brain changes sustained by survivors of brain tumors with the goal of improving treatment regimens to reduce cognitive inhibition. For example, one fMRI-based study of pediatric patients with medulloblastoma found evidence of long-term effects of prophylactic reading intervention, including significantly increased sound awareness [

149]. Notably, a longitudinal study of medulloblastoma survivors revealed that support vector machine classification of functional MRI data indicated a progressive divergence in brain activity patterns compared to healthy controls over time, suggesting delayed effects of cancer treatment on brain function [

150]. Alterations in brain regions involved in visual processing and orthographic recognition during rapid naming tasks were correlated with performance in tasks involving sound awareness, reading fluency, and word attack, highlighting the dynamic nature of post-treatment neurofunctional alterations. Additionally, a functional imaging study showed that adults who had experienced childhood craniopharyngioma exhibited cognitive interference processing abilities on a par with those of the control group, as fMRI of these survivors showed no compensatory activity within the cingulo-fronto-parietal attention network when they were compared to the control group [

151].

Traditional deep learning models often lack transparency, making it challenging to understand which features contribute to their classification decisions. The eXplainable Artificial Intelligence fNIRS (xAI-fNIRS) system is an innovative approach that addresses the issue of explainability in deep learning methods for classifying fNIRS data. This is achieved by incorporating an explanation module that can decompose the output of the deep learning model into interpretable input features [

152].

The goal of neuromodulation is to restore normal neural function in areas affected by neurobiological abnormalities or to facilitate compensatory mechanisms by stimulating alternative neural networks. Once an association is established between a functional neurobiological pattern and a neurocognitive alteration in pediatric catastrophic disease survivors, neuromodulation becomes a potentially relevant and promising strategy for intervention. In the context of pediatric catastrophic disease survivors, who may experience long-term neurocognitive deficits due to the disease or its treatment, neuromodulation offers several potential applications in neuroplasticity promotion, symptom management, cognitive enhancement, and personalized medicine.

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures, and it can occur in pediatric patients with cancer, such as LGGs [

153]. The association between epilepsy and these conditions is often related to the location of the underlying disease within the brain and its impact on neural circuits. Dystonia is a movement disorder characterized by involuntary muscle contractions that cause repetitive or twisting movements and abnormal postures. Dystonia can occur in children with thalamic tumors, particularly when the tumor directly affects or compresses the thalamus or nearby brain structures involved in motor control [

154].

For epilepsy, DBS is applied to the anterior thalamic nucleus to decrease brain excitement, which in turn decreases the frequency or duration of seizures [

155]. For dystonia, DBS of the cerebellum has improved dystonia by reducing the severity of spasms and improving posture and pain relief [

156]. Therefore, neuromodulation is a treatment option for a wide range of movement and brain disorders.

With regard to neuromodulation, AI enables faster data collection and monitoring, which can aid in early diagnosis, treatment, patient monitoring, and disease prevention [

30]. Machine learning can analyze large datasets to improve the efficiency of neuromodulation. A reinforcement learning paradigm intended to optimize a neuromodulation strategy for epilepsy treatment found a stimulation strategy that both reduces the frequency of seizures and minimizes the amount of stimulation applied [

157]. Closed-loop DBS systems can use neural activity to find patterns in symptoms and produce parameters in real time to alter the stimulation and prevent tremors [

158,

159].

Even though there has been extensive research on using AI in neuromodulation, only a very small subset of this research has pertained to pediatrics. However, a machine learning technique to monitor and predict epileptic seizures in pediatric patients has been reported [

160]. The application of scalp EEG data to create a treatment prediction model for vagus nerve stimulation in pediatric epilepsy, using brain functional connectivity features, has also been reported [

161].

Incorporating AI into the data collection and monitoring stages of neurofeedback offers the potential for early detection and precise non-pharmacological management of neurological conditions. AI facilitates the analysis of extensive patient data, enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of neurofeedback processes. Hence, there is a need for additional research to explore comprehensively and expand the use of brain–computer interfaces that incorporate AI [

162]. Incorporating AI into neurofeedback holds promise for unlocking fresh avenues by which to enhance substantially the effectiveness of these therapeutic approaches for neurological disorders [

162].

6. AI for Selecting and Modifying Personalized Therapies

Personalized medicine is the future of oncology, and AI plays a crucial role. Personalized therapies reduce unnecessary side effects and improve quality of life. AI-driven treatment plans can enhance patient experiences by focusing on therapies with the highest likelihood of success. In recent years, there has been a surge in clinical trials exploring diverse immunotherapy approaches, with several agents gaining approval from regulatory authorities such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, the outcomes of immunotherapy treatments have been variable, and this variability is often attributed to the absence of precise diagnostic tools for identifying patients who are likely to respond to specific therapies. To address this critical challenge, the integration of machine learning–based techniques hold great promise. Radiomics-based techniques have shown promise in predicting CD3 T-cell infiltration status in glioblastoma [

163] and in predicting the survival of patients receiving programmed death–ligand 1 inhibition immunotherapy [

164].

7. AI in Monitoring Treatment Response

Monitoring the response of pediatric brain tumors to therapy can pose challenges, particularly because of the intense inflammation that may occur in the early phases of treatments such as radiation therapy and immunotherapy. This inflammation can be transient, often improving over time—a phenomenon referred to as pseudoprogression. Importantly, pseudoprogression shares imaging features with true tumor progression, making it crucial to distinguish between the two, as their clinical management strategies differ significantly. Although advanced MRI and PET techniques have been applied to address this issue in pediatric neuro-oncology, it remains a challenge. Encouragingly, machine learning techniques have been deployed to differentiate between these two conditions, demonstrating promising success in this endeavor [

165,

166].

8. AI in Predicting Survival for Patients with Pediatric Brain Tumors

Despite extensive research, some pediatric brain tumors still carry a grim prognosis, with overall survival often being less than 2 years from the time of diagnosis. The molecular characterization of these tumors was a significant leap forward, offering clinicians valuable prognostic insights. However, considerable variability persists within specific tumor subgroups, and a universally applicable tool for accurately predicting survival in all patients with pediatric brain tumors remains elusive. Machine learning–based techniques present a promising avenue, particularly when it comes to predicting survival at the time of diagnosis and especially for tumors that are not amenable to surgical resection. A substantial collective effort is now focused on leveraging machine learning to develop predictive tools for these challenging cases. For instance, one notable approach involves a subregion-based survival prediction framework tailored for gliomas using multi-sequence MRI data, achieving an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.98 in predicting survival outcomes [

161]. By using radiomic features derived from T1-weighted post-contrast imaging, progression-free survival can be predicted with concordance indices of up to 0.7 [

167]. Similarly, a multiparametric MRI-based radiomics signature, integrated with machine learning, demonstrated strong potential for preoperative prognosis stratification in pediatric medulloblastoma, achieving an AUC of up to 0.835 in the validation set [

168].

9. AI for Transparent Explanations in Cancer Neuroimaging

Research on explainable AI (XAI) for pediatric cancer neuroimaging is still limited, though recent efforts have focused on developing XAI models for neuroimaging in cancer populations, with opportunities to adapt these models for pediatric cases. These models aim to improve brain tumor detection, localization, and classification while providing interpretable results for clinicians. Recent research by Ashry et al. investigates the use of deep learning for automated recognition of pediatric Posterior Fossa Tumors (PFT) in brain MRIs [

169]. They explored CNN models, including VGG16, VGG19, and ResNet50, for PFT detection and classification, using a dataset of 300,000 images from 500 patients. The study also analyzed model behavior using Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), and Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE). Results indicated that VGG16 was the best model compared to VGG19 and ResNet50. Rahman et al. (2023) proposed a lightweight CNN with Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) visualization, achieving high accuracy in brain cancer detection and localization [

170]. The importance of XAI lies in its ability to visualize model features, improve interpretability, and enable human-machine interactions that are crucial for clinical adoption [

171]. Recent developments, such as NeuroXAI, a framework implementing multiple XAI methods for MRI analysis of brain tumors, demonstrate the potential of XAI to enhance transparency and reliability in neuroimaging, facilitating the adoption of AI models in clinical practice for cancer diagnosis and treatment planning [

172]. Another study explored the Adaptive Aquila Optimizer with XAI for effective colorectal and osteosarcoma cancer classification, combining Faster SqueezeNet for feature extraction, adaptive optimization for tuning, ensemble DL classifiers for diagnosis, and LIME for interpretability [

173].

10. Discussion

AI has the potential to transform medicine by enabling the analysis of large quantities of patient data to provide faster, more accurate diagnoses and to reduce the need for invasive procedures. AI can also help healthcare providers to optimize clinical workflows by automating repetitive tasks and reducing the administrative burden on clinicians.

A limitation of current work on using AI for neuroimaging applications in pediatric cancer is the lack of large datasets, as AI models require a substantial amount of data to learn. One way to overcome this limitation is to encourage collaboration and data sharing among laboratories across universities, research organizations, hospitals, and other healthcare institutions. This can be achieved by developing standardized protocols for data collection, processing, and analysis, as well as by establishing data sharing agreements that ensure data privacy and ethical use of data. An alternative approach to address the problem of limited datasets is transfer learning, in which pre-trained models from other domains or populations can be fine-tuned for use with smaller pediatric datasets. Another limitation of pediatric neuroimaging is the lack of standardization in imaging protocols and quality control measures across different research laboratories. If non-standardized datasets are combined in an AI model, such differences can decrease the accuracy and reliability of the model.

There are several knowledge gaps concerning AI for neuroimaging applications in pediatric cancer. First, although AI models have shown promising results in diagnosing and predicting outcomes of some pediatric neurological diseases, such as brain tumors, there has been only limited research on the generalizability of these models across different patient populations.

Second, there is a need for more research on the interpretability of AI models in pediatric neuroimaging. Interpretability of AI models is critical, especially in healthcare applications such as pediatric neuroimaging. Although AI models may provide accurate predictions, the black-box nature of some AI models can be a concern, as it may limit the ability of the user to understand how the model arrives at its decisions or predictions, thereby potentially limiting their clinical utility. Developing methods to explain the logic behind AI model predictions would help to improve their transparency, trustworthiness, and scientific contribution [

152]. Third, there is a need for more research on integrating AI models into clinical practice. The development of AI models is only the first step in their implementation into clinical workflows, and more research is needed to determine how these models can be integrated into clinical decision making and how they can have an impact on patient outcomes.

Explainable AI is paramount in pediatric neuroimaging for several reasons. In clinical applications, understanding the decision-making process of AI models is crucial for gaining trust among healthcare professionals and facilitating seamless integration into diagnostic workflows. Moreover, in cancer, where decisions can have profound implications, explainability ensures that clinicians and researchers comprehend how AI arrives at its predictions or classifications. The application of AI in pediatric neuroimaging demands a high level of interpretability. This transparency fosters a collaborative environment between AI tools and healthcare practitioners. As we navigate the future of AI in pediatric neuroimaging, emphasis should be placed on furthering the development of explainable AI techniques. This not only aligns with the growing demand for transparency in AI applications but also positions pediatric catastrophic disease research at the forefront of responsible AI implementation.

In summary, therefore, the current challenges in applying AI to neuroimaging in pediatric cancer are data availability, technical variability, interpretability, ethical considerations, and integration with clinical practice. Moreover, regulatory issues concerning safety, privacy, efficacy, and ethics related to the use of AI in pediatric neuroimaging raise specific challenges in different countries.

Ethical concerns such as data privacy, bias, and transparency also need to be addressed in the development and implementation of AI models for pediatric neuroimaging. It is essential to ensure that these models are developed and validated in an ethical and responsible manner to avoid potential harm to patients and to maintain public trust in AI applications. As AI becomes more prominent in neuroimaging, it will be necessary to establish guidelines and ethical frameworks for its responsible use in patient care and research.

AI can facilitate the integration and analysis of multimodal neuroimaging data from various sources and research centers [

174,

175]. Collaborative efforts with AI-based tools can accelerate discoveries and improve data sharing within the scientific community.

AI can help identify novel biomarkers associated with various neurological and psychiatric conditions by analyzing large datasets of functional imaging data. These biomarkers could aid in early diagnosis and personalized treatment strategies. Advanced AI algorithms can predict the progression of neurological disorders and their response to specific neuromodulation treatments. This predictive capability can help clinicians to make more informed decisions about patient care and long-term management.

The use of AI for pediatric neuroimaging is a rapidly growing field. Some of the key areas of focus for future developments in this field include large-scale data collection, multimodal integration of neuroimaging modalities (such as MRI, fMRI, resting-state fMRI, MRS, DTI, fNIRS, EEG, and MEG), early detection of pathologies, real-time neuroimage processing and analysis, personalized treatment planning, prediction of treatment outcomes, longitudinal neuroimaging analysis, and the theoretical explanation of pathological phenomena.

When studying brains that were previously affected by solid tumors, the approaches used should consider 1) mass effect, with reference to displacement and compression indices; 2) edema, with reference to morphometry, density, and composition; and 3) maps of tissue damage, in terms of volume, morphometry, density and structural/functional connectivity. Density can be extracted from T1 MRI images, whereas composition is derived from PET scans. Structural connectivity analysis may consider diffusion imaging features extracted as voxel-based measures, such as the apparent diffusion coefficient, fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, radial diffusivity, and axial diffusivity, and tensor-based measures, such as tensor connectivity maps. AI can further refine and enhance the analysis of functional imaging data, such as fMRI. Advanced AI algorithms can extract more precise information from complex brain activity patterns and lead to better insights into brain function and connectivity.

AI can enable closed-loop systems in which real-time functional imaging data is used to adapt and optimize neuromodulation in real time. This dynamic approach can ensure that stimulation parameters are continuously adjusted to suit the changing state of the brain, making treatments more efficient and effective. AI can be used in designing and optimizing neuromodulation devices, such as DBS systems. AI-driven simulations can assist in developing more precise and targeted stimulation paradigms. Moreover, AI can assist in identifying the most effective neuromodulation techniques for individual patients, based on their unique brain activity patterns. By considering patient-specific features, such as neural network connectivity, AI can optimize treatment parameters for better outcomes.

11. Conclusion

Although AI has seen significant advances in its application to neuroimaging in adult populations, its implementation in children with cancer has been limited by several factors, including the scarcity of available datasets and the unique challenges of applying adult-focused AI methods to pediatric populations. The limited number of pediatric neuroimaging datasets poses a significant challenge in training AI models specifically for children with cancer. AI algorithms rely heavily on large, diverse datasets to learn patterns and make accurate predictions. Additionally, the neuroimaging characteristics of children are different from those of adults because of ongoing brain development, size differences, and diverse neurological conditions that may manifest differently in pediatric patients. Therefore, direct translation of AI approaches from adult neuroimaging to children might not be feasible without appropriate adjustments and validation. Conversely, AI models trained on a restricted pool of pediatric data might be less effective than those trained on larger and more comprehensive datasets derived from adults.

To address these challenges and to foster the development of AI in pediatric neuroimaging, there is a need to build larger and more diverse pediatric neuroimaging databases. Collaboration among institutions and data sharing initiatives are essential to ensure the responsible and effective use of AI in pediatric populations. As collaborations and data sharing initiatives begin to standardize pediatric data collection, the development of AI approaches tailored specifically to pediatric applications will increase significantly.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in writing and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Keith A. Laycock, PhD, ELS, for scientific editing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pringle, C.; Kilday, J.P.; Kamaly-Asl, I.; Stivaros, S.M. 2022. The role of artificial intelligence in paediatric neuroradiology. Pediatr. Radiol. 52(11), 2159–2172.

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; 2023. Deep learning in pediatric neuroimaging. Displays 80, 102583.

- Martin, D.; Tong, E.; Kelly, B.; Yeom, K.; Yedavalli, V. 2021. Current perspectives of artificial intelligence in pediatric neuroradiology: an overview. Front. Radiol. 1, 713681. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Khalvati, F.; Ertl-Wagner, B.B. 2024. Artificial Intelligence in the Future Landscape of Pediatric Neuroradiology: Opportunities and Challenges. American Journal of Neuroradiology.

- Russell, S.; Norvig, P. 2016. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 3rd ed. Pearson.

- Helm, J.M.; Swiergosz, A.M.; Harberle, H.S.; Karnuta, J.M.; Schaffer, J.L.; Krebs, V.E.; Spitzer, A.I.; Ramkumar, P.N. 2020. Machine learning and artificial intelligence: definitions, applications, and future directions. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 13, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Bini, S.A. 2018. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, and cognitive computing: What do these terms mean and how will they impact healthcare? J. Arthroplasty 33(8), 2358–2361. [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. 2009. The Elements of Statistical Learning. Springer. ISBN: 978-0387848570.

- Bishop, C.M. 2006. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer. ISBN: 978-0387310732.

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G.; 2018. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction (2nd ed.). MIT Press. ISBN: 978-0262039246.

- McCall, J. 2005. Genetic algorithms for modelling and optimisation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 184(1), 205–222. [CrossRef]

- Valueva, M.V.; Nagornov, N.N.; Lyakhov, P.A.; Valuev, G.V.; Chervyakov, N.I.; 2020. Application of the residue number system to reduce hardware costs of the convolutional neural network implementation. Math. Comput. Simul. 177, 232–243. [CrossRef]

- Mzoughi, H.; Njeh, I.; Wali, A.; et al. 2020. Deep multi-scale 3D convolutional neural network (CNN) for MRI gliomas brain tumor classification. J. Digit. Imaging 33, 903–915. [CrossRef]

- Lu, D. 2022. AlexNet-based digital recognition system for handwritten brushes. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Cyber Security and Information Engineering (ICCSIE ‘22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 509–514. [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; et al.; 2015. Going deeper with convolutions. In 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Dong, Y.; Gao, L.; 2019. A new ensemble residual convolutional neural network for remaining useful life estimation. Math. Biosci. Eng. 16(2), 862–880. [CrossRef]

- Ranschaert, E.; Topff, L.; Pianykh, O. 2021. Optimization of radiology workflow with artificial intelligence. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 59(6), 955–966. [CrossRef]

- Ravi, K.S.; Nandakumar, G.; Thomas, N.; Lim, M.; Qian, E.; Jimeno, M.M.; Poojar, P.; Jin, Z.; et al. 2023. Accelerated MRI using intelligent protocolling and subject-specific denoising applied to Alzheimer’s disease imaging. Front. Neuroimaging 2, 1072759.

- Bash, S.; Wang, L.; Airriess, C.; Zaharchuk, G.; Gong, E.; Shankaranarayanan, A.; Tanenbaum, L.N. 2021. Deep learning enables 60% accelerated volumetric brain MRI while preserving quantitative performance: a prospective, multicenter, multireader trial. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 42(12), 2130–2137.

- Chen, Y.; Schönlieb, C.B.; Liò, P.; Leiner, T.; Dragotto, P.L.; Wang, G.; Rueckert, D.; Firmin, D.; Yang, G. 2022. AI-based reconstruction for fast MRI—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Proc. IEEE 110(2), 224–245. [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, R.D.; Zhang, Y.; Callahan, M.J.; Perez-Rosselli, J.; Breen, M.A.; Johnston, P.R.; Yu, H. 2019. Improving low-dose pediatric abdominal CT by using convolutional neural networks. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 1(6). [CrossRef]

- Gokyar, S.; Robb, F.; Kainz, W.; Chaudhari, A.; Winkler, S. 2021. MRSaiFE: An AI-based approach towards the real-time prediction of specific absorption rate. IEEE Access 9, 140824–140834.

- Dyer, T.; Chawda, S.; Alkilani, R.; Morgan, T.N.; Hughes, M.; Rasalingham, S. 2022. Validation of an artificial intelligence solution for acute triage and rule-out normal of non-contrast CT head scans. Neuroradiology 64, 735–743. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Yan, L.F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.C.; Han, Y.; et al.; 2018. Radiomics strategy for glioma grading using texture features from multiparametric MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 48, 1518–1528. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wong, S.W.; Wright, J.N.; Wagner, M.W.; Toescu, S.; Han, M.; Tam, L.T.; Zhou, Q.; Ahmadian, S.S.; Shpanskaya, K.; et al.; 2022. MRI radiogenomics of pediatric medulloblastoma: A multicenter study. Radiology 304, 406–416.

- Chiu, F.Y.; Yen, Y. 2022. Efficient radiomics-based classification of multi-parametric MR images to identify volumetric habitats and signatures in glioblastoma: a machine learning approach. Cancers (Basel) 14(6), 1475.

- Khalili, N.; Kazerooni, A.F.; Familiar, A.; Haldar, D.; Kraya, A.; Foster, J.; Koptyra, M.; Storm, P.B.; Resnick, A.C.; Nabavizadeh, A. 2023. Radiomics for characterization of the glioma immune microenvironment. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 7, 59.

- Park, J.E.; Kim, H.S.; Goh, M.J.; Kim, N.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, J.H. 2015. Pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma: assessment by using volume-weighted voxel-based multiparametric clustering of MR imaging data in an independent test set. Radiology 275(3), 792–802.

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, J.; 2022. Artificial intelligence for prediction of response to cancer immunotherapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 87, 137–147.

- Patel, U.K.; Anwar, A.; Saleem, S.; et al. 2021. Artificial intelligence as an emerging technology in the current care of neurological disorders. J. Neurol. 268, 1623–1642. [CrossRef]

- Fathi Kazerooni, A.; Saxena, S.; Toorens, E.; Tu, D.; Bashyam, V.; Akbari, H.; Mamourian, E.; Sako, C.; Koumenis, C.; Verginadis, I.; et al. 2022. Clinical measures, radiomics, and genomics offer synergistic value in AI-based prediction of overall survival in patients with glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 8784. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Muzny, D.M.; Reid, J.G.; Bainbridge, M.N.; Willis, A.; Ward, P.A.; Eng, C.M.; 2013. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of Mendelian disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 369(16), 1502–1511.

- McCarthy, M.L.; Ding, R.; Hsu, H.; Dausey, D.J. 2018. Developmental and behavioral comorbidities of asthma in children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 39(4), 293–304.

- Müller, H.L. 2014. Craniopharyngioma. Endocr. Rev. 35, 513–543.

- Fjalldal, S.; Holmer, H.; Rylander, L.; Elfving, M.; Ekman, B.; Osterberg, K.; Erfurth, E.M. 2013. Hypothalamic involvement predicts cognitive performance and psychosocial health in long-term survivors of childhood craniopharyngioma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98(8), 3253–3262. [CrossRef]

- Jale Ozyurt, M.S.; Thiel, C.M.; Lorenzen, A.; Gebhardt, U.; Calaminus, G.; Warmuth-Metz, M.; Muller, H.L. 2014. Neuropsychological outcome in patients with childhood craniopharyngioma and hypothalamic involvement. J. Pediatr. 164(4), 876–881.e4. [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, L.M. 2001. Brain tumours. N. Engl. J. Med. 344(2), 114–122.

- Alksas, A.; Shehata, M.; Atef, H.; Sherif, F.; Alghamdi, N.S.; Ghazal, M.; Abdel Fattah, S.; El-Serougy, L.G.; El-Baz, A. 2022. A novel system for precise grading of glioma. Bioengineering (Basel) 9(10), 532. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering9100532. PMID: 36290500; PMCID: PMC9598212. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyer-Jamora, C.; Brie, M.S.; Luks, T.L.; Smith, E.M.; Baunstein, S.E.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; et al.; 2021. Cognitive impact of lower-grade gliomas and strategies for rehabilitation. Neurooncol. Pract. 8(2), 117–128. [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; et al. 2017. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 114(2), 97–109.

- Speville, E.D.; Kieffer, V.; Dufour, C.; Grill, J.; Noulhiane, M.; Hertz-Pannier, L.; Chevignard, M.; 2021. Neuropsychological consequences of childhood medulloblastoma and possible interventions. Neurochirurgie 67(1), 90–98. [CrossRef]

- Deer, T.R.; Mekhail, N.; Provenzano, D.; Pope, J.; Krames, E.; Leong, M.; Levy, R.M.; Abejon, D.; Buchser, E.; et al. 2014. The appropriate use of neurostimulation of the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system for the treatment of chronic pain and ischemic diseases: the Neuromodulation Appropriateness Consensus Committee. Neuromodulation 17(6), 515–550. [CrossRef]

- Krames, E.S. 2014. The role of neuromodulation in the treatment of chronic pain. Anesthesiol. Clin. 32(4), 725–741.

- Piccirillo, J.F.; Kallogjeri, D.; Nicklaus, J.; Wineland, A.; Spitznagel, E.L.; Vlassenko, A.; Rodebaugh, T.L. 2019. Low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to the temporoparietal junction for tinnitus. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 145(8), 748–756.

- Rana, M.; Gupta, N.; Dalboni da Rocha, J.L.; Lee, S.; Sitaram, R. 2013. A toolbox for real-time subject-independent and subject-dependent classification of brain states from fMRI signals. Front. Neurosci. 7, 170. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Dalboni da Rocha, J.L.; Birbaumer, N.; Sitaram, R. 2024. Self-regulation of the posterior–frontal brain activity with real-time fMRI neurofeedback to influence perceptual discrimination. Brain Sci. 14, 713. [CrossRef]

- Sitaram, R.; Ros, T.; Stoeckel, L.; et al.; 2017. Closed-loop brain training: The science of neurofeedback. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 86–100. [CrossRef]

- Wolpaw, J.R.; 2013. Brain-computer interfaces. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 110, 67–74. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52901-5.00006-X. PMID: 23312631. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blockmans, L.; Golestani, N.; Dalboni da Rocha, J.L.; Wouters, J.; Ghesquière, P.; Vandermosten, M. 2023. Role of family risk and of pre-reading auditory and neurostructural measures in predicting reading outcome. Neurobiology of Language 4(3), 474–500. [CrossRef]

- Slater, D.A.; Melie-Garcia, L.; et al.; 2019. Evolution of white matter tract microstructure across the lifespan. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 2252–2268.

- Pfefferbaum, A.; Mathalon, D.H.; Sullivan, E.V.; et al. 1994. A quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study of changes in brain morphology from infancy to late adulthood. Arch. Neurol. 51(9), 874–887.

- Barkovich, A.J.; Raybaud, C. 2012. Pediatric Neuroimaging, fifth ed. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

- Wang, L.; Gao, Y.; Shi, F.; Li, G.; Gilmore, J.H.; Lin, W.; Shen, D.; 2015. LINKS: Learning-based multi-source integration framework for segmentation of infant brain images. Neuroimage 108, 160–172.

- Kim, S.H.; Lyu, I.; Fonov, V.S.; Vachet, C.; Hazlett, H.C.; Smith, R.G.; Piven, J.; Dager, S.R.; McKinstry, R.C.; Pruett, J.R. Jr.; Evans, A.C. 2016. Development of cortical shape in the human brain from 6 to 24 months of age via a novel measure of shape complexity. NeuroImage 135, 163–176.

- Dalboni da Rocha, J.L.; Schneider, P.; Benner, J.; et al. 2020. TASH: Toolbox for the Automated Segmentation of Heschl’s gyrus. Sci. Rep. 10, 3887. [CrossRef]

- Maghsadhagh, S.; Dalboni da Rocha, J.L.; Benner, J.; Schneider, P.; Golestani, N.; Behjat, H. 2021. A discriminative characterization of Heschl’s gyrus morphology using spectral graph features. In: 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), pp. 3577–3581. IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Fonov, V.; Evans, A.C.; Botteron, K.; Almli, C.R.; McKinstry, R.C.; Collins, D.L.; the Brain Development Cooperative Group. 2011. Unbiased average age-appropriate atlases for pediatric studies. NeuroImage 54(1), 313–327. [CrossRef]

- Wilke, M.; Holland, S.K.; Altaye, M.; Gaser, C.; 2008. Template-O-Matic: A toolbox for creating customized pediatric templates. Neuroimage 41, 903–913.

- Kazemi, K.; Moghaddam, H.A.; Grebe, R.; et al. 2007. A neonatal atlas template for spatial normalization of whole-brain magnetic resonance images of newborns: preliminary results. NeuroImage 37, 463–473.

- Shi, F.; Yap, P.T.; Wu, G.; et al.; 2011. Infant brain atlases from neonates to 1- and 2-year-olds. PLoS ONE 6, e18746.