Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Grape Pomace

2.3. Phenolic Extraction

2.4. Total Phenolics

2.5. Oligomeric Procyanidins

2.6. Phenolic Characterization by HPLC

2.7. In Vitro α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase Inhibition Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

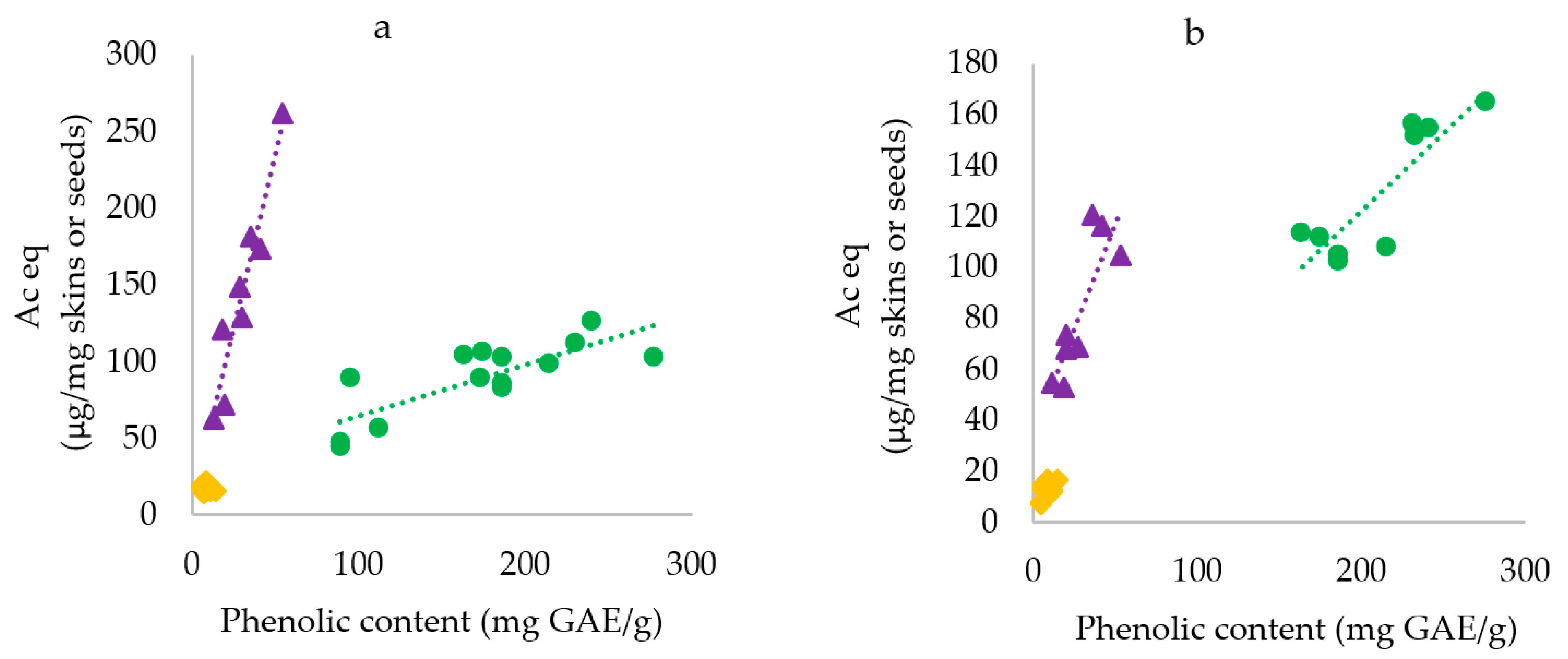

3.1. α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition

3.1.1. α-Glucosidase Inhibition

3.1.2. α-Amylase Inhibition

3.2. Characterization of Food-Grade Extracts of Red Grape Skins

4. Discussion

| Compound/plant | Solvent | µg Ac eq/µg | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| catechin | < 0.047 | [13] | |

| epicatechin | < 0.047 | [13] | |

| procyanidin B1 | < 0.047 | [13] | |

| malvidin 3-O-glucoside | 3.99 | [10] | |

| cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | 0.26, 0.46, 0.52 | [9,10,11] | |

| delphinidin 3-O-glucoside | 3.46 | [10] | |

| petunidin 3-O-glucoside | 3.12 | [10] | |

| quercetin | 0.22, 0.09 | [12,13] | |

| quercetin 3-O-glucoside | 0.28 | [14] | |

| kaempferol | 0.093 | [13] | |

| kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | 0.12, 0.16 | [13,14] | |

| Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) | fruit, 0.2% formic acid in water | 2.0 | [9] |

| Rowanberry (Sorbus aucuparia) | fruit, 0.2% formic acid in water | 1.3 | [9] |

| Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) | fruit, 0.2% formic acid in water | < 0.2 | [9] |

| Cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus) | fruit, 0.2% formic acid in water | < 0.2 | [9] |

| Blackberry (Rubus grandifolius) | fruit, 80% methanol, 7% acetic acid | 0.4 | [11] |

| Blackberry (Rubus grandifolius) | fruit, 80% methanol, 7% acetic acid | 0.4 | [11] |

| Blackberry (Rubus grandifolius) | leaves, 80% methanol, 7% acetic acid | 0.5 | [11] |

| Blackberry (Rubus grandifolius) | leaves, 80% methanol, 7% acetic acid | 0.6 | [11] |

| Red cabbage (Brassica oleracea) | edible part, 70% methanol | 5.8 | [30] |

| Red cabbage (Brassica oleracea) | edible part, 70% methanol | 8.3 | [30] |

| Red cabbage (Brassica oleracea) | edible part, 70% methanol | 5.4 | [30] |

| Red cabbage (Brassica oleracea) | edible part, 70% methanol | 6.6 | [30] |

| Red cabbage (Brassica oleracea) | edible part, 70% methanol | 4.3 | [30] |

| Coffee (Coffea arabica) | ground roasted beans, water | 1.7 | [31] |

| Mushroom (Grifola frondose) | fruiting body, 95% ethanol | 4.5 | [29] |

| Grape (Vitis vinifera) | red skins, 60% ethanol | 5.2 ± 0.1 | this study |

| Compound/plant | Solvent | µg Ac eq/µg | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| catechin | 0.0021, 0.043 | [15,16] | |

| epicatechin | nd | [15,16], [17] | |

| cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | 0.020, 0.044 | [11,18] | |

| quercetin | < 0.027 | [19] | |

| kaempferol | < 0.028 | [19] | |

| PA, mDP not specified | 6.1, 1.2 | [20,21] | |

| PA mDP 1.35 %G 5.43) | 0.28 | [22] | |

| PA mDP 6.97 %G 13.27) | 6.77 | [22] | |

| Rowanberry (Sorbus aucuparia) | fruit, 0.2% formic acid in water | 0.2 | [9] |

| Hibiscus (Hibiscus deflersii) | aerial parts, water | 0.6 | [32] |

| Hibiscus (Hibiscus calyphyllus) | aerial parts, water | 0.3 | [32] |

| Hibiscus (Hibiscus micranthus) | aerial parts, water | 0.2 | [32] |

| Dogwoods (Cornus mas) | fruits, 60% ethanol extract | 0.8 | [33] |

| Dogwoods (Cornus alba) | fruits, 60% ethanol extract | 0.7 | [33] |

| Elderberry (Sambucus nigra) | edible part, 50% ethanol | 8.34 | [35] |

| Saffron (Crocus sativus) | stigma, water extract | 1.98 | [34] |

| Saffron (Crocus sativus) | tepal, water extract | 2.32 | [34] |

| Coffee (Coffea arabica) | ground roasted beans, water | 1.49 | [31] |

| Red pepper (Capsicum annuum) | edible part, 70% ethanol | 8.42 | [36] |

| Grape (Vitis vinifera) | red skins, 60% ethanol | 2.0 ± 0.1 | this study |

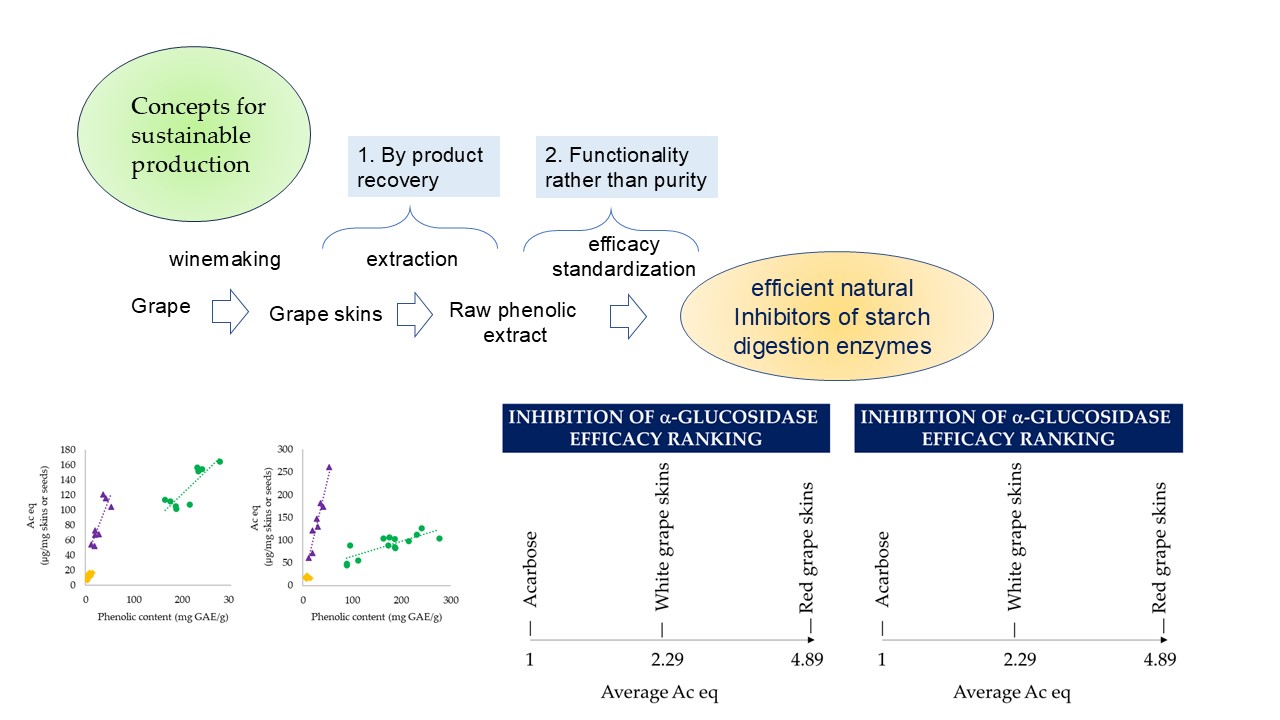

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, L.; Miao, M. Dietary polyphenols modulate starch digestion and glycaemic level: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 4, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosak, C.; Mertes, G. Critical evaluation of the role of acarbose in the treatment of diabetes: Patient considerations. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2012, 5, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisneros-Yupanqui, M.; Lante, A.; Mihaylova, D.; Krastanov, A.I.; Rizzi, C. The α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition capacity of grape pomace: A review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 16, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taladrid, D.; Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Martin-Cabrejas, M.A.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Bartolomé, B. Grape pomace as a cardiometabolic health-promoting ingredient: activity in the intestinal environment. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Sun, S.; Canning, C.; Zhou, K. Antioxidant rich grape pomace extract suppresses postprandial hyperglycemia in diabetic mice by specifically inhibiting α-glucosidase. Nutr. Metab., 2010, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Hogan, S.; Li, J.; Sund, S.; Canning, C.; Zheng, S.J.; Zhou, Z. Grape skin extract inhibits mammalian intestinal α-glucosidase activity and suppresses postprandial glycemic response in streptozocin-treated mice. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato-Schwartz, C.G.; Corrêa, R.C.G.; de Souza Lima, D.; de Sá-Nakanishi, A.B.; de Almeida Gonçalves, G.; Seixas, F.A.V.; Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Bracht, A.; et al. Potential anti-diabetic properties of Merlot grape pomace extract: An in vitro, in silico and in vivo study of-amylase and-glucosidase inhibition. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapwarobol, S.; Adisakwattana, S.; Changpeng, S.; Ratanawachirin, W.; Tanruttanawong,K.; Boonyarit, W. Postprandial blood glucose response to grape seed extract in healthy participants: A pilot study. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2012, 8, 31, 192–196. [CrossRef]

- Boath, A. S.; Stewart, D.; McDougal, G. J. Berry components inhibit α-glucosidase in vitro: Synergies between acarbose and polyphenols from black currant and rowanberry. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xi, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W. Pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside as a novel α-glucosidase inhibitor for improving postprandial hyperglycemia. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinola, V.; Pinto, J.; Llorent-Martínez, E. J.; Tomás, H.; Castilho, P. C. Evaluation of Rubus grandifolius L. (wild blackberries) activities targeting management of type-2 diabetes and obesity. Food Chem. Toxicol, 2019; 123, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.-H.; Ha, K.-S.; Moon, K.-S.; Lee, O.-H.; Jang, H.-D.; Kwon, Y.-I. In vitro and in vivo anti-hyperglycemic effects of Omija (Schizandra chinensis) Fruit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12(2), 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Deng, Z.; Ramdath, D. D.; Tang, Y.; Chen, P. X.; Liu, R.; Liu, Q.; Tsao, R. Phenolic profiles of 20 Canadian lentil cultivars and their contribution to antioxidant activity and inhibitory effects on a-glucosidase and pancreatic lipase. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şöhretoğlu, D.; Sari, S.; Barut, B.; Özel, A. Discovery of potent α-glucosidase inhibitor flavonols: Insights into mechanism of action through inhibition kinetics and docking simulations. Bioorg.Chem. 2018, 79, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Kong, H.; Chitrakar, B.; Ban, X.; Gu, Z.; Hong, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, Z.; Li, C. The substitution sites of hydroxyl and galloyl groups determine the inhibitory activity of human pancreatic α-amylase in twelve tea polyphenol monomers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmazer-Musa, M. A. M.; Griffith, A. J.; Schneider, M. E.; Frei, B. Grape seed and tea extracts and catechin 3-gallates are potent inhibitors of a-amylase and a-glucosidase activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8924–8929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeswurm, J. A. H., B. Claasen, M. P. Fischer, and M. Buchweitz. 2019. Interaction of structurally diverse phenolic compounds with porcine pancreatic a-amylase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11108–11118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, G. T.T.; Kase, E. T.; Wangensteen, H.; Barsett, H. Phenolic elderberry extracts, anthocyanins, procyanidins, and metabolites influence glucose and fatty acid uptake in human skeletal muscle cells J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 2677–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Sun, W.; Xing, Y.; Xiu, Z.; Zhuang, C.; Dong, Y. Dietary flavonoids and acarbose synergistically inhibit α-glucosidase and lower postprandial blood glucose. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8319–8330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Song, L.; Wang, H.; Huang, D.A. High-through put assay for quantification of starch hydrolase inhibition based on turbidity measurement. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011; 59, 9756–9762. [Google Scholar]

- Ostberg-Potthoff, J.J.; Berger, K.; Richling, E.; Winterhalter, P. Activity-guided fractionation of red fruit extracts for the identification of compounds influencing glucose metabolism. Nutrients, 2019, 11(5), 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Luo, L.; Wang, J.; Sun, B. In vitro evaluation of the anti-digestion and antioxidant effects of grape seed procyanidins according to their degrees of polymerization. J. Func. Foods 2018, 89, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Goot, A. J.; Pelgrom, P. J. M.; Berghout, J. A. M.; Geerts, M. E. J.; Jankowiak, L.; Hardt, N. A.; Keijer, J.; Schutyser, M. A. I.; Nikiforidis, C. D.; Boom, R. M. Concepts for further sustainable production of foods. J. Food Eng. 2016, 168, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, D.; De Faveri, D. M.; Spigno, G. Grape marc phenolics: Extraction kinetics, quality and stability of extracts. J. Food Eng. 2010, 97, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrali, D.; Barbarito, S.; Lavelli, V. Encapsulation of grape seed phenolics from winemaking byproducts in hydrogel microbeads – Impact of food matrix and processing on the inhibitory activity towards α-glucosidase. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 133, 109952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonassi, G.; Lavelli, V. Hydration and fortification of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) with grape skin phenolics—Effects of ultrasound application and heating. Antioxidants, 2024, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelli, V.; Sri Harsha, P. S. C.; Fiori, L. Screening grape seeds recovered from winemaking byproducts as sources of reducing agents and mammalian α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitors. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-N.; Shin, J.-G.; Jang, H.-D. Antioxidant and antidiabetic activity of Dangyuja (Citrus grandis Osbeck) extract treated with Aspergillus saitoi. Food Chem. 2009, 117(1), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yong, T.; Xiao, C.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, C.; Xie, Y. Pyrrole alkaloids and ergosterols from Grifola frondosa exert anti-α-glucosidase and anti-proliferative activities. J. Func. Foods, 2018, 43, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsędek, A.; Majewska, I.; Kucharska, A. Z. Inhibitory potential of red cabbage against digestive enzymes linked to obesity and type 2 diabetes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 7192–7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitiku, H.; Kim, T. Y.; Kang, H.; Apostolidis, E.; Lee, J. Y.; Kwon, Y.I. Selected coffee (Coffea arabica L. ) extracts inhibit intestinal α-glucosidases activities in-vitro and postprandial hyperglycemia in SD rats BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yousef, H.M.; Hassan, W.H.B.; Abdelaziz, S.; Amina, M.; Adel, R.; El Sayed, M.A. UPLC-ESI-MS/MS Profile and antioxidant, cytotoxic, antidiabetic, and antiobesity activities of the aqueous extracts of three different Hibiscus species. J. Chem. 2020, 6749176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swierczewska, A.; Buchholz, T.; Melzig, M. F., Czerwinska, M. E. In vitro a-amylase and pancreatic lipase inhibitory activity of Cornus mas L. and Cornus alba L. fruit extracts. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 1, 249–258. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellachioma, L.; Morresi, C.; Albacete, A.; Martínez-Melgarejo, P.A.; Ferretti, G.; Giorgini, G.; Galeazzi, R.; Damiani, E.; Bacchetti, T. Insights on the hypoglycemic potential of Crocus sativus Tepal polyphenols: An in vitro and in silico study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzi, M.; Cavi, D.; Majki, T., Zengin, G.; Radojkovi, M. Could elderberry fruits processed by modern and conventional drying and extraction technology be considered a valuable source of health-promoting compounds? Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134766. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Sotto, A.; Vecchiato, M., Abete, L.; Toniolo, C.; Giusti, A. M. L. Mannina, Locatelli, M.; Nicoletti, M., Di Giacomo, S. Capsicum annuum L. var. Cornetto di Pontecorvo PDO: Polyphenolic profile and in vitro biological activities. J. Func. Foods, 2018, 40, 679-691. [CrossRef]

| Sample | α-Glucosidase Inhibition | α-Amylase Inhibition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I50 mg skins/mL | µg Ac eq/mg skins | I50 mg skins/mL | µg Ac eq/mg skins | |

| Red skins | ||||

| DO 01 | 0.77ab ± 0.03 | 130cd ± 7 | 0.24a ± 0.02 | 118e ± 3.9 |

| BA | 0.68ab ± 0.04 | 148de ± 12 | 0.44ab ± 0.01 | 68.3c ± 5.3 |

| FR | 0.38a ± 0.02 | 261f ± 21 | 0.29ab ± 0.00 | 105d ± 0.9 |

| CR | 0.58ab ± 0.03 | 173e ± 13 | 0.26a ± 0.03 | 116e ± 3.2 |

| NE | 1.39b ± 0.29 | 72c ± 8 | 0.42ab ± 0.02 | 70c ± 3.5 |

| NR | 1.66c ± 0.26 | 62b ± 13 | 0.55b ± 0.02 | 55b ± 1.9 |

| GR | 0.83ab ± 0.05 | 121cd ± 10 | 0.57b ± 0.00 | 52b ± 1.5 |

| DO 02 | 0.55ab ± 0.03 | 181e ± 10 | 0.25a ± 0.01 | 118e ± 2.3 |

| White skins | ||||

| MO | 5.51ef ± 0.28 | 18.1a ± 0.1 | 2.23d ± 0.18 | 14.0a ± 1.1 |

| AR | 4.62d ± 0.08 | 21.6a ± 0.4 | 1.77c ± 0.10 | 16.9a ± 0.1 |

| ER | 5.36e ± 0.54 | 18.8a ± 0.1 | 1.85c ± 0.11 | 16.2a ± 0.9 |

| MT | 6.42g ± 0.10 | 15.6a ± 0.1 | 1.82c ± 0.01 | 16.5a ± 0.1 |

| CH | 5.88fg ± 0.44 | 16.7a ± 0.6 | 2.26d ± 0.24 | 13.1a ± 1.4 |

| NA | 6.45g ± 0.29 | 15.5a ± 0.7 | 2.44d ± 0.30 | 12.4a ± 1.5 |

| RI | 5.69efg ± 0.20 | 17.1a ± 0.6 | 2.38d ± 0.12 | 12.6a ± 0.6 |

| Parameter | |

|---|---|

| delphinidin-3-O-glucoside | 34.5 ± 1.4 |

| cyanidin-3-O-glucoside | 14.9 ± 0.6 |

| petunidin-3-O-glucoside | 44.4 ± 1.8 |

| peonidin-3-O-glucoside | 17.9 ± 0.7 |

| malvidin-3-O-glucoside | 93.4 ± 3.7 |

| malvidin-p-coumaroyl-glucoside | 17.9 ± 0.7 |

| quercetin 3-O-glucoside | 29.7 ± 1.2 |

| quercetin | 27.2 ± 1.1 |

| kaempferol | 5.2 ± 0.2 |

| procyanidin B1 | 6.6 ± 0.3 |

| catechin | 37.3 ± 1.5 |

| procyanidin B2 | 10.3 ± 0.4 |

| epicatechin | 17.5 ± 0.7 |

| oligomeric procyanidins | 3180 ± 130 |

| total phenolics (GAE) | 5490 ± 220 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).