Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

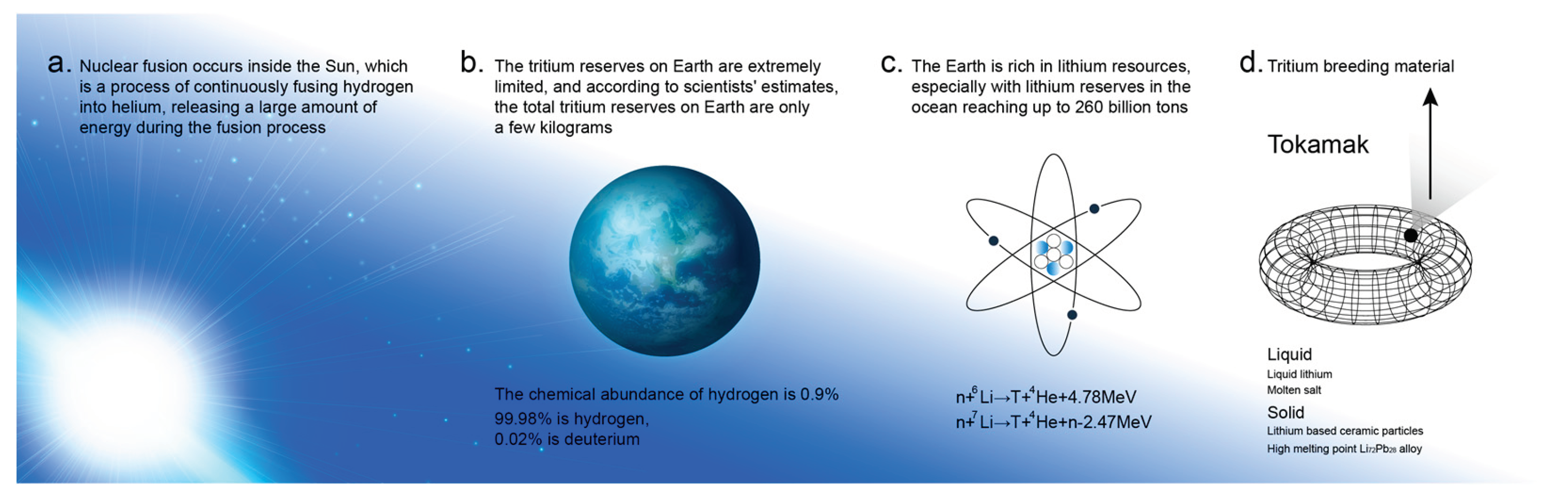

1. Introduction

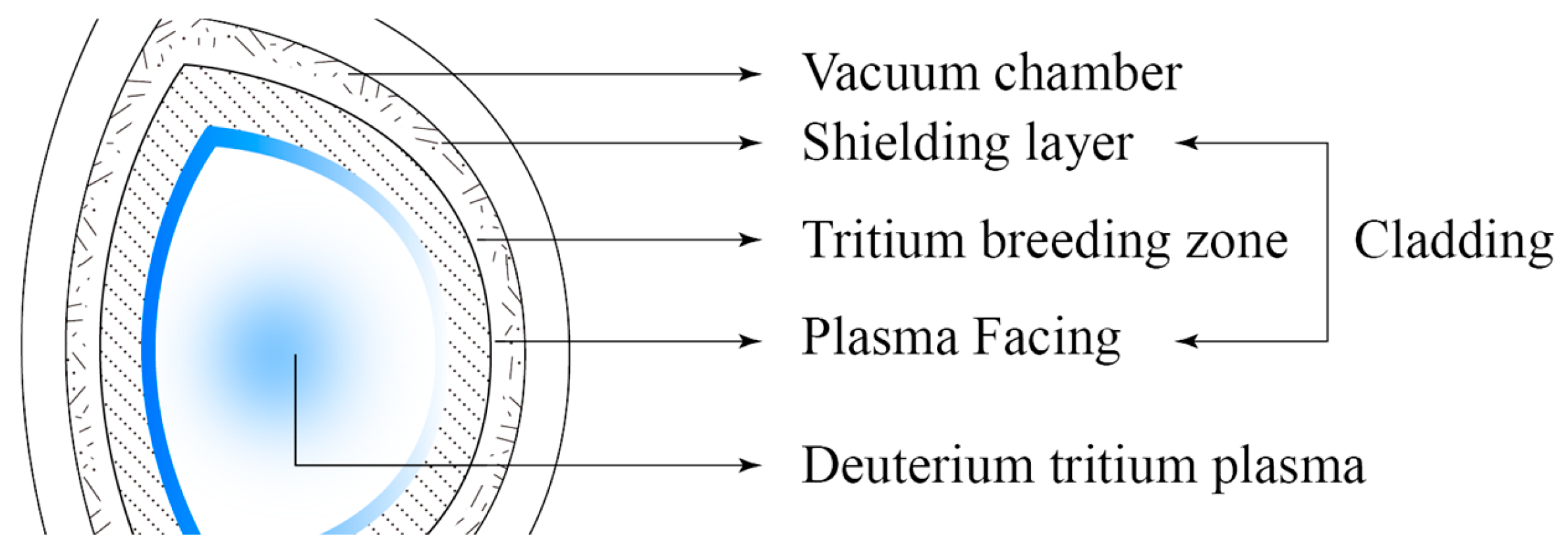

2. Tritium Breeding Material for Fusion Reactor Cladding

- Fusion core is the core part of fusion reactor to produce energy. In order to protect the core from external interference and damage, cladding is needed to provide insulation, isolation and protection to prevent the core from being affected by external factors;

- The fusion reaction is a high-temperature and high-pressure reaction. By adjusting the temperature and pressure of the cladding, the speed and intensity of the fusion reaction can be controlled to ensure the normal operation of the fusion reactor;

- The cladding of a nuclear fusion reactor can play a role in collecting energy, and the generated energy is collected and converted into electricity or other forms of energy output through pipes and devices inside the cladding;

- Through the control system and equipment inside the cladding, the fusion reactor can be monitored and adjusted to ensure its stable operation.

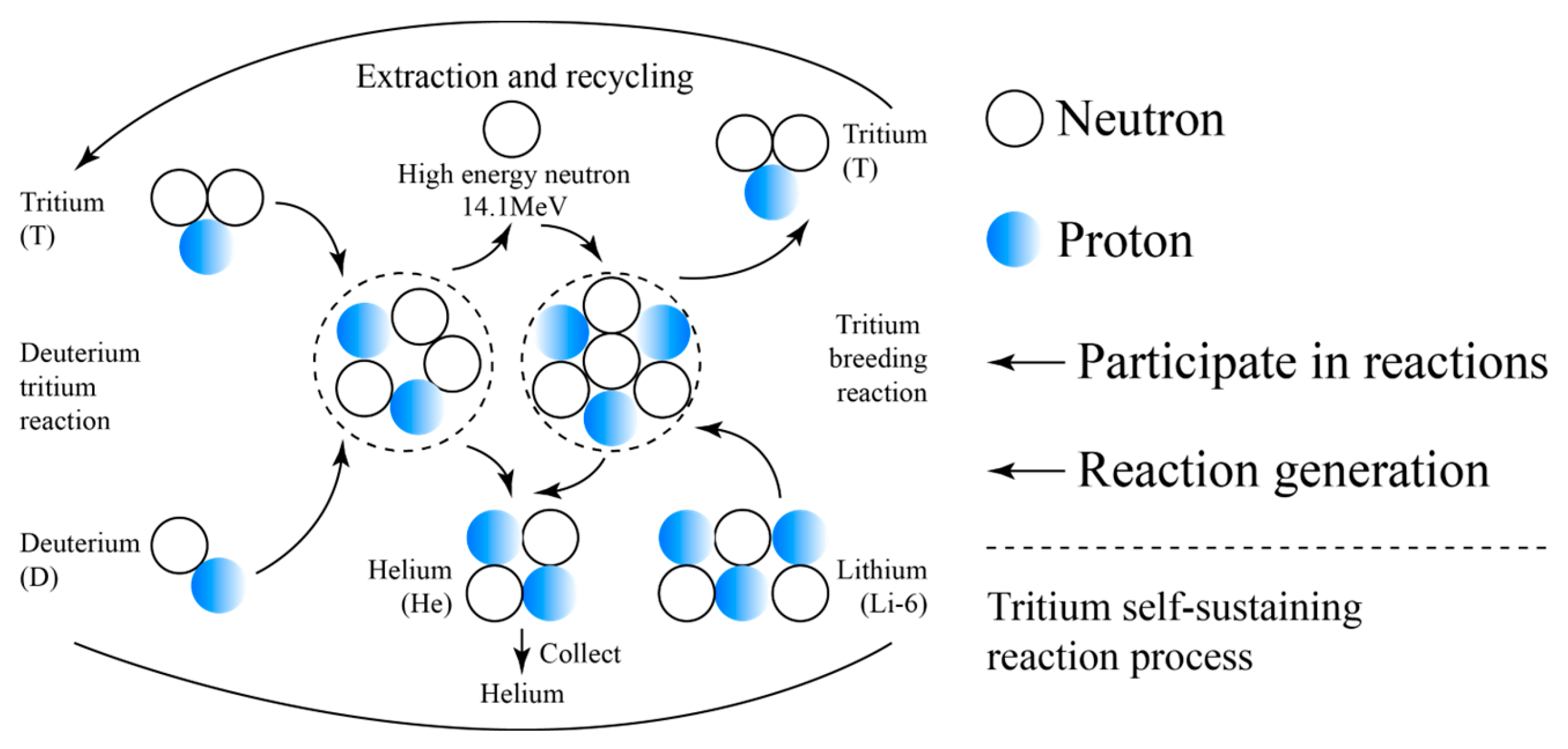

3. Liquid Tritium Breeding Material

- Good fluidity, easy to change materials, cladding structure is relatively simple, easy to design and construct;

- Good thermal conductivity, high lithium content, easy to exchange heat through the flow of liquid metal, to achieve tritium breeding;

- Tritium recovery is convenient.

3.1. Fluorine Containing Molten Salt Tritium Breeding Material

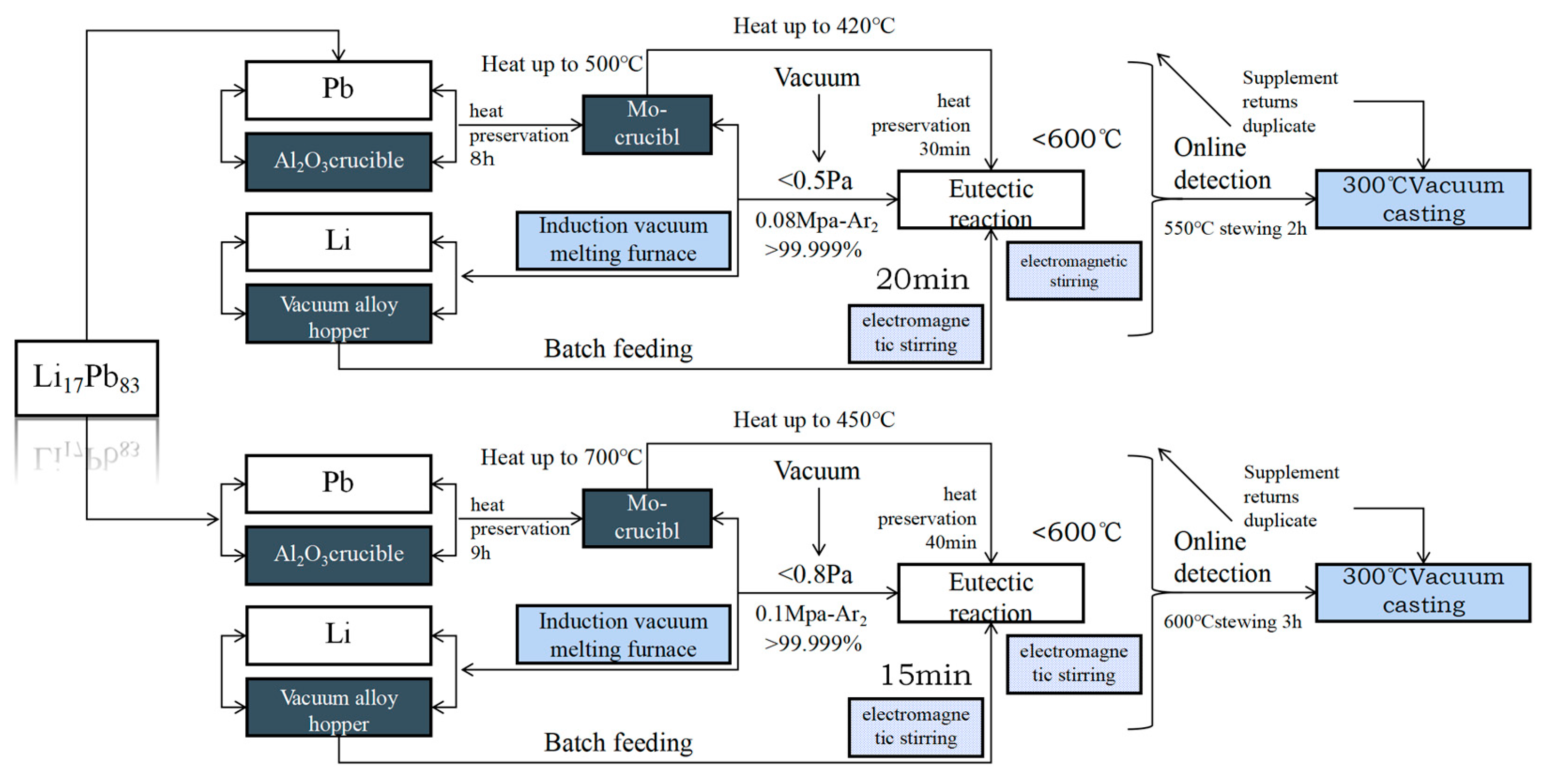

3.2. Li17Pb83 Tritium Breeding Materials

4. Solid Tritium Breeding Material

- Ceramic microspheres must be able to support or withstand various stresses from ITER operation, such as pressure, temperature, temperature gradient and thermal shock, to avoid washing gas leakage;

- The ball bed has a stable thermal conductivity parameter when working to avoid too high or too low temperature;

- Ensure good compatibility between the ceramic breeding agent ball bed and EUROFER steel under maximum temperature range and other conditions;

- A higher tritium breeding ratio (TBR) requires TBR>1;

- Ensure the stability of ceramic microsphere materials during the process of structural changes caused by lithium atom migration under high temperature conditions;

- Ceramic ball beds must have a certain ability to resist neutron irradiation, in order to prevent serious consequences such as container wall rupture caused by neutron irradiation damage to the bed and leakage of washing gas;

- Good tritium release performance and lower tritium retention;

- Minimize neutron irradiation activity of materials and impurities.

4.1. Lithium Based Ceramic Oxide Particles

4.1. Feasibility Study on the Latest Solid Clad Li72Pb28 Alloy

5. Tritium Breeding Rate (TBR)

6. Conclusions

- Firstly, the liquid tritium breeding material cladding has the advantages of strong fluidity, strong spatial geometry adaptability and high tritium breeding ratio. Lithium has been eliminated as a breeder of tritium, and molten salt can undergo proper transmutation, which has a certain prospect. Liquid lithium lead alloy is still the most promising liquid tritium breeder material, and has been widely used in various types of fusion reactors. However, more in-depth research and solutions are needed for corrosion, air tightness and magnetohydrodynamic effects;

- Secondly, compared with liquid tritium breeder, solid tritium breeder has better tritium production capacity, and there is no strict requirement for corrosion and sealing. However, solid tritium breeding materials require the introduction of high-cost beryllium as a neutron multiplier. The newly published high melting point lithium lead alloy is the most promising solid tritium breeding material because it can satisfy the function of neutron breeding and tritium breeding at the same time, and can run continuously at high temperature;

- Finally, liquid lithium lead alloy with low melting point and solid lithium lead alloy with high melting point are the two most promising tritium breeding materials. Considering the advantages and disadvantages of the two materials, it is concluded that solid lithium lead alloy may be more promising, it is a functional, structural and economically balanced material, currently in the conceptual calculation stage, the need for actual qualified products to verify the engineering feasibility.

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rebut, P. H., Keen, B. E., Huguet, M., Dietz, K., Hemmerich, J. L., Last, J. R., … Raimondi, T. (1987). Authors. Fusion Technology, 11(1), 1–6.

- Pearson R, Comsa O, Stefan L, et al. Romanian Tritium for Nuclear Fusion[J]. Taylor & Francis, 2017.

- Yasushi S. Conceptual designs of tokamak fusion reactors.[J]. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 1989. [CrossRef]

- Knaster J, Moeslang A, Muroga T. Materials research for fusion[J]. Nature Physics, 2016:424-434. [CrossRef]

- Santiago,Cuesta-Lopez, J. M, et al. PROGRESS IN ADVANCED MATERIALS UNDER EXTREME CONDITIONS FOR NUCLEAR FUSION TECHNOLOGY[J]. Fusion science and technology: An international journal of the American Nuclear Society, 2012, 61(1T):385-390. [CrossRef]

- Federici G, Boccaccini L, Cismondi F, et al. An overview of the EU breeding blanket design strategy as an integral part of the DEMO design effort[J]. Fusion Engineering and Design, 2019, 141(APR.):30-42. [CrossRef]

- Tobita K, Hiwatari R, Sakamoto Y, et al. fusion science and technology japans efforts to develop the concept of ja demo during the past decade noriyoshi nakajima & the joint special design team for fusion demo and the joint special design team for fusion demo a[J]. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Cho S, Ahn M Y, Chun Y B, et al. Status of HCCR TBM program for DEMO blanket[J]. Fusion Engineering and Design, 2021, 171(2):112553. [CrossRef]

- Grishina I A, Ivanov V A, Kovrizhnyh L M, et al. Plasma physics and controlled nuclear fusion research in Russia: main achievements in 2006[J]. 2007.

- PREDHIMAN,KAW,SHISHIR,et al. Fusion research programme in India[J]. Sadhana: Academy Proceedings in Engineering Science, 2013, 38(5):839-848. [CrossRef]

- Jiangang L, Yuanxi W. Present State of Chinese Magnetic Fusion Development and Future Plans[J]. Journal of Fusion Energy, 2018:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Sheffield,John.Future World Energy Demand and Supply: China and India and the Potential Role of Fusion Energy[J]. Fusion Science & Technology, 2005, 47(3):323-329. [CrossRef]

- Reinders L, J. Post-ITER: DEMO and Fusion Power Plants[J]. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Peng X, Song Y, Yang Y, et al. [IEEE 2011 IEEE 24th Symposium on Fusion Engineering (SOFE) - Chicago, IL, USA (2011.06.26-2011.06.30)] 2011 IEEE/NPSS 24th Symposium on Fusion Engineering - Design feasibility analysis of the robot for EAST tokamak flexible in-vessel inspection[J]. 2011:1-4. [CrossRef]

- Kessel C E, Blanchard J P, Davis A, et al. Overview of the fusion nuclear science facility, a credible break-in step on the path to fusion energy[J]. North-Holland, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Cai L, Lu K, Lu Y, et al. Progress of Engineering Design of CFETR Machine Assembly[J]. Fusion Science and Technology, 2022, 78:631 - 639. [CrossRef]

- A G R, B J C, A H W, et al. The CFETR tritium plant: Requirements and design progress - ScienceDirect[J]. Fusion Engineering and Design, 159[2024-11-13]. [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky M. Clad materials for fusion applications[J]. Thin Solid Films, 1980, 73(1):117-132. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka S. Development of Fusion Reactor Blanket System[J]. Journal of Plasma & Fusion Research, 1999, 75(8):885-894. [CrossRef]

- Fillo J A. First-wall fusion-blanket heat transfer[J]. begel house inc, 1980. [CrossRef]

- Oku T. Graphite Materials for Nuclear Reactors[J]. Tanso, 2011, 1991(150):338-353. [CrossRef]

- Burchell T D, Eatherly W P, Robbins J M, et al. The effect of neutron irradiation on the structure and properties of carbon-carbon composite materials[J]. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 1992, s 191–194(part-PA):295–299. [CrossRef]

- Nozawa T, Hinoki T, Hasegawa A, et al. Recent advances and issues in development of silicon carbide composites for fusion applications[J]. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 2009, 386(17):622-627. [CrossRef]

- Federici,G.Comprehensive nuclear materials || beryllium as a plasma-facing material for near-term fusion devices[J]. 2012:621-666. [CrossRef]

- Joneja O P, Nargundkar V R. Neutronic Performance of Candidate Neutron Multipliers Beryllium and Lead in a Stainless Steel First Wall[J]. Fusion Technology, 1990, 18(2):310-316. [CrossRef]

- Smith D L, Loomis B A, Diercks D R. Vanadium-base alloys for fusion reactor applications — a review[J]. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 1985, 135(2-3):125-139. [CrossRef]

- Yao W Z, Song S X, Zhou Z J, et al. Study on the Plasma-Sprayed Molybdenum as Plasma Facing Materials in Fusion Reactor[J]. Key Engineering Materials, 2008, 373-374:81-84. [CrossRef]

- Qu,D,D, et.al. DEVELOPMENT OF FUNCTIONALLY GRADED TUNGSTEN/EUROFER COATING SYSTEM FOR FIRST WALL APPLICATION[J]. Fusion Science & Technology An International Journal of the American Nuclear Society, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Abdou M A. Deuterium-Tritium Fuel Self-Sufficiency in Fusion Reactors[J]. Fusion Science and Technology, 1986. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Ji B L, Gu S X, et al. Recent research progress on the compatibility of tritium breeders with structural materials and coatings in fusion reactors[J]. Tungsten(English), 2022, 4(3):14. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi B M, Tyagi A K, Prakash D. Synthesis and Processing of Li-Based Ceramic Tritium Breeder Materials[J]. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Muyi Ni,Chao Lian,Shichao Zhang, et al. Structural design and preliminary analysis of liquid lead–lithiumblanket for China Fusion Engineering Test Reactor[J]. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Sagara A, Yamanishi H, Imagawa S. Design and development of the Flibe blanket for helical-type fusion reactor FFHR[J]. Fusion Engineering & Design, 2000, 49:661-666. [CrossRef]

- Xie B, Yang T, Hu R. Theoretical analysis of tritium breeding behavior for liquid lithium tin alloy[J]. Nuclear Techniques, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, Salanne, Christian, et al. A First-Principles Description of Liquid BeF2 and Its Mixtures with LiF: 2. Network Formation in LiFBeF2[J]. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2006, 110(23):11461–11467. [CrossRef]

- Ono M, Majeski R, Jaworski M A, et al. Liquid lithium loop system to solve challenging technology issues for fusion power plant[J]. Nuclear Fusion, 2017, 57(11):116056.1-116056.9. [CrossRef]

- Mánek, Petr, Van Goffrier G, Gopakumar V, et al. Fast Regression of the Tritium Breeding Ratio in Fusion Reactors[J]. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Abdou M A, Team T A. Exploring novel high power density concepts for attractive fusion systems[J]. Fusion Engineering and Design, 1999, 45(2):145-167. [CrossRef]

- Uebeyli M. Investigation on the Neutronic Performance of a Fusion Reactor Using Flibe with Heavy Metal Fluorides[J]. Journal of Fusion Energy, 2006, 25(1/2):67-72. [CrossRef]

- Uebeyli M. Radiation Damage and Tritium Breeding Study in a Fusion Reactor Using a Liquid Wall of Various Thorium Molten Salts[J]. Journal of Fusion Energy, 2007, 26(4):317-321. [CrossRef]

- Uebeyli M, Yapici H. Utilization of Heavy Metal Molten Salts in the ARIES-RS Fusion Reactor[J]. Journal of Fusion Energy, 2008, 27(3):200-205. [CrossRef]

- Mingzhun Lei, Yuntao Song, Minyou Ye, et al. Flibe molten salt blanket structure for fusion reactor[J]. 2015.

- Ahin H M, Güven Tun, Karako A, et al. Neutronic study on the effect of first wall material thickness on tritium production and material damage in a fusion reactor[J]. Nuclear Science and Techniques, 2022, 33(4):1-18. [CrossRef]

- Azam S, Schaer M, Schneeberger J P, et al. Neutronics Studies of Fusion Blankets: Results on a Simulated Lithium-Lead Module[J]. Fusion Technology, 1991, 20(4P2):888-893. [CrossRef]

- Kim D, Noborio K, Hasegawa T, et al. Development of LiPb–SiC High Temperature Blanket[J]. Green Energy & Technology, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Huang Q, Zhang M, Zhu Z, et al. Corrosion experiment in the first liquid metal LiPb loop of China[J]. Fusion Engineering & Design, 2007, 82(15-24):2655-2659. [CrossRef]

- Kalinin G M, Strebkov Y S. The Structure and Properties of LiPb Eutectic and Near-Eutectic Alloys[J]. Fusion Science and Technology, 2009, 56(2):826-830. [CrossRef]

- Maolian Zhang, Yican Wu, Qunying Huang,, et al. Preparation method of lithium-lead alloy Li17Pb83 for nuclear industry.2015[2024-11-13].

- Min P G, Vadeev V E. Vacuum Induction Furnace Melting Technology for High-Temperature Composite Material Based on Nb–Si System[J]. Metallurgist, 2019, 63(4). [CrossRef]

- XIE,Bo,YANG,et al. Trace tritium recovery from the residue of liquid Li_(17)Pb_(83) alloy[J]. Science China, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Khan M S, Huang Q, Bai Y, et al. Performance Optimization of Power Generation System for Helium Gas/Lead Lithium Dual-coolant Blanket System[J]. Journal of Fusion Energy, 2021, 40(1). [CrossRef]

- Baus C, Barron P, Andrea D'Angiò,et al. Kyoto Fusioneering's Mission to Accelerate Fusion Energy: Technologies, Challenges and Role in Industrialisation[J]. Journal of Fusion Energy, 2023, 42(1). [CrossRef]

- Stankus S V, Khairulin R A, Mozgovoi A G. An experimental investigation of the density and thermal expansion of advanced materials and heat-transfer agents of liquid-metal systems of fusion reactor: Lead-lithium eutectic[J]. High Temperature, 2006, 44(6):829-837. [CrossRef]

- Alejaldre C, L. Rodríguez-Rodrigo, Taylor N, et al. ITER on the Way to Become the First Fusion Nuclear Installation[J]. 2008.

- Linjie Zhao, et al. Research progress of solid tritium breeder materials [J]. Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemistry, 2015, 37(3):129-142. [CrossRef]

- Jiang,K.; Wu,Q.; Chen,L.; Liu, S. Conceptual design of solid-type PbxLiy eutectic alloy breeding blanket for CFETR. Nuclear Fusion 2023, 63, 036023. [CrossRef]

- Montanaro L, Lecompte J P. Preparation via gelling of porous Li2ZrO3 for fusion reactor blanket material[J]. Journal of Materials Science, 1992, 27(14):3763-3769. [CrossRef]

- A,Deptuła,T, et al. Inorganic Sol-Gel Preparation of Medium Sized Microparticles of Li2TiO3 from TiCl4 as Tritium Breeding Material for Fusion Reactors[J]. Journal of Sol Gel Science & Technology, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee,M,Naskar,et al. Novel technique for the synthesis of lithium aluminate (LiAlO2) powders from water-based sols.[J]. Journal of Materials Science Letters, 2003.

- Jiang W, Wang T, Wang Y, et al. Deuterium diffusion in γ-LiAlO2 pellets irradiated with He+ and D2+ ions[J]. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 2020:152357. [CrossRef]

- Oyaidzu M, Yoshikawa A, Nishikawa Y, et al. Hot atom chemical behavior of tritium in neutron-irradiated Li2TiO3 and Li2ZrO3[J]. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 2007, 272(3):657-660. [CrossRef]

- Avila R E, Pea L A, J.C. Jiménez.Surface desorption and bulk diffusion models of tritium release from Li 2TiO 3 and Li 2ZrO 3 pebbles[J]. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 2010, 405(3):244-251. [CrossRef]

- Qi, QiangWang, JingZhou, QilaiZhang, YingchunZhao, MingzhongGu, ShouxiNakata, MoekoZhou, HaishanOya, YasuhisaLuo, Guang-Nan.Comparison of tritium release behavior in Li2TiO3 and promising core-shell Li2TiO3-Li4SiO4 biphasic ceramic pebbles[J]. Journal of Nuclear Materials: Materials Aspects of Fission and Fusion, 2020, 539(1). [CrossRef]

- A D K M, A S K, A A, et al. Inelastic scattering and first principles study of tritium breeder materials Li2TiO3 and Li2ZrO3 - ScienceDirect[J]. Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 203[2024-11-14]. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Zhao L, Ran G, et al. Tritium release behavior of Li2TiO3 and 2Li2TiO3-Li4SiO4 biphasic ceramic pebbles fabricated by microwave sintering[J]. Fusion Engineering and Design, 2021, 168:112390. [CrossRef]

- Uchida M, Ishitsuka E, Kawamura H. Thermal conductivity of neutron irradiated Be 12Ti[J]. Fusion Engineering & Design, 2003, 69(1/4):499-503. [CrossRef]

- Fischer U, Pereslavtsev P, Grosse D, et al. Nuclear design analyses of the helium cooled lithium lead blanket for a fusion power demonstration reactor[J]. Fusion Engineering & Design, 2010, 85(7-9):1133-1138. [CrossRef]

- Shanliang Z, Yican W. Neutronic Comparison of Tritium-Breeding Performance of Candidate Tritium-Breeding Materials[J]. Plasma science and Technology: English version, 2003, 5(5):1995-2000. [CrossRef]

- Koichi M. An Analytical Formula for Calculating the Tritium Breeding Ratio in Fusion Reactor Blankets[J]. Fusion Technology, 1987, 12(2):310-319. [CrossRef]

- Beyli M. On the Tritium Breeding Capability of Flibe, Flinabe, and Li 20 Sn 80 in a Fusion-Fission (Hybrid) Reactor[J]. Journal of Fusion Energy, 2003, 22(1):51-57. [CrossRef]

- Acir A. Effect of Nuclear Data Libraries on Tritium Breeding in a (D–T) Fusion Driven Reactor[J]. Journal of Fusion Energy, 2008, 27(4):301-307. [CrossRef]

- Colling B R, Monk S D. Development of fusion blanket technology for the DEMO reactor[J]. Appl Radiat Isot, 2012, 70(7):1370-1372. [CrossRef]

- Hendricks J S, Mckinney G W, Waters L S, et al. New MCNPX developments[J]. Military Technology Weaponry & National Defense, 2001.

- Forrest, R.A. FISPACT-2007: User manual 2007.

- Miao Y, Yun-Tao S, Ming-Zhun L, et al. Design of the molten salt blanket and the calculation of tritium breeding ratio[J]. Nuclear Fusion and Plasma Physics, 2017.

- Segantin S, Testoni R, Zucchetti M. Neutronic comparison of liquid breeders for ARC-like reactor blankets[J]. Fusion Engineering and Design, 2020, 160. [CrossRef]

- Goel V, Aslam S, Dua S. Optimization of Tritium Breeding Ratio in a DT and DD Submersion Tokamak Fusion Reactor[J]. 2023.

- A P K R, A N E H, A B R H, et al. OpenMC: A state-of-the-art Monte Carlo code for research and development[J]. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 2015, 82:90-97. [CrossRef]

| Properties | Li | Li17Pb83 | Li2BeF4 | Li20Sn80 | Flinabe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Point(◦C) | 180 | 235 | 459 | 330 | ~300 |

| Density(g/cm3) | 0.48 | 8.98 | 2.0 | 6.2 | 2.0 |

| Li Density(g/cm3) | 0.48 | 0.062 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| Li2O | γ−LiAlO2 | Li2ZrO3 | Li2TiO3 | Li4SiO4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | High lithium density |

Good chemical stability |

Excellent tritium release performance |

Lowtritium release temperature |

Lowactivation issues |

| Good thermal conductivity |

Stable under irradiation |

--- | Good compatibility |

High lithium density |

|

| Lowactivation issues |

--- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Disadvantages | Sensitivity to moisture |

Lowlithium density |

Activation issues for Zr |

Reduction of Ti | Sensitivity to moisture |

| Significant swelling under irradiation |

Modest tritium release preformance |

--- | --- | --- | |

| High Li vaporization |

--- | --- | --- | --- |

| Candidate solid breeder materials | Melting Point(◦C) | Li Density(g/cm3) | Thermal Conductivity Coefficient at 1000 K (W/mK) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li2O | 1433 | 0.93 | 3.4 |

| LiAlO2 | 1610 | 0.28 | 2.2 |

| Li4SiO4 | 1250 | 0.54 | 1.5 |

| Li2ZrO3 | 1616 | 0.33 | 1.3 |

| Li8ZrO6 | 1250 | 0.68 | 1.5 |

| Li2TiO3 | 1295 | 0.33 | 2.0 |

| Li72Pb28 | 999 | --- | --- |

| Lithium-Based material | Tritium Breeding Ratio Tally (14MeV) | Tritium Breeding Ratio Tally (2.5MeV) |

|---|---|---|

| Li(Pure Lithium) | 1.10905 | 0.543946 |

| Li2O(Lithium Oxide) | 1.09383 | 0.542774 |

| Li2ZrO3(Lithium Zirconate) | 0.974073 | 0.490369 |

| Li2TiO3(Lithium Titanate) | 0.980266 | 0.501079 |

| Li4SiO4(Lithium Orthosilicate) | 1.00325 | 0.525374 |

| LiCl(Lithium Chloride) | 1.04656 | 0.539386 |

| FLiBe(LiF and BeF2) | 1.08196 | 0.569398 |

| Li17Pb83 | 1.14519 | 0.570423 |

| Li72Pb28 | 1.08(Minimum, atomic ratio of Pb 20%) | 1.15(Maximum, atomic ratio of Pb 28%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).