Introduction

Earth’s climate has changed dramatically in recent decades (IPCC, 2023; Falk et al., 2024). Human-induced climate change has reduced the resilience of Amazon ecosystems much faster than the environmental changes that have occurred naturally in the past (Albert et al., 2023). Approximately 38% of Amazonian forests have been devastated by rising temperatures, edge effects, logging, fires, and extreme droughts (Lapola et al., 2023). The Amazon region has also been directly affected by an increase in extreme floods and droughts in recent years, with significant implications for human livelihoods and biodiversity (Marengo & Espinoza, 2016; Espinoza et al., 2021, 2024; Fleischmann et al., 2023; Silva et al., 2023; Terassi et al., 2024), including the record-breaking 2021 flood and 2023 drought in Amazon (Espinoza et al., 2021, 2024).

These observed changes can increase the size, frequency, and duration of blooms of photosynthetic organisms. The occurrence of harmful cyanobacterial blooms in various regions worldwide has been associate witch rising temperatures, decreasing water levels, and excessive nutrient enrichment in aquatic environments (Igwaran et al., 2024). For instance, three intense summer heat waves showed a significant relationship with cyanobacteria proliferation in Lake Taihu in China (Li et al., 2022). During this period, the daily concentration of chlorophyll-a increased due to rising air temperatures, higher levels of photosynthetically active radiation, and reduced wind speed. However, no studies conducted in the Amazon region have yet linked phytoplankton blooms to the direct impacts of climate change.

In 2023, a basin-wide extreme drought occurred, significantly disrupting the environmental and social dynamics in the Amazon (Espinoza et al., 2024). Hundreds of thousands of people, particularly those in riverine communities, were isolated, resulting in a significant reduction in their access to potable water, food, medicines, essential services and markets in nearby urban areas. In the middle Solimões River, specifically in the large Amazonian Tefé and Coari lakes, a mass mortality event of river dolphins (Inia geoffrensis and Sotalia fluviatilis) occurred. Between Sep and Oct 2023, 330 individuals died in Tefé lake, and mortality extended until November in Coari lake (Marmontel et al., 2024). Extreme heating of the waters, which reached temperatures as high as 41°C, was considered the main cause (Marmontel et al., 2024; Fleischmann et al., 2024). During the same time, another unprecedented phenomenon occurred in both lakes: a significant proliferation of reddish algae.

Algal proliferation has the potential to cause environmental damage, including eutrophication, dissolved oxygen depletion, fish mortality, and toxin production (Dokulil & Teubner, 2011). However, in the Amazon, algae blooms have been recorded mainly in urban environments, by cyanobacteria in fish farming tanks, public supply reservoirs and eutrophic bodies of water close to city (Fonseca et al., 2015; Pinheiro et al., 2023). The only existing record of potentially toxic blooms in natural Amazonian systems involves an intense proliferation of cyanobacteria, specifically Anabaena sp. and Microcystis sp., in the Tapajós River, a clear water body in Eastern Amazonia (Sá et al., 2010). Although the concentrations of the microcystin-LR toxin were below the maximum limits allowed by Brazilian legislation for drinking water, in-situ observations indicated that the blooms occupied approximately 10 cm of the water column, which could potentially cause skin irritation for individuals bathing in the river (Sá et al., 2010). To document any potentially toxic bloom in the Amazon is thus very relevant for a system that undergoes multiple environmental stressors.

The reddish bloom in Tefé and Coari lakes during the extreme 2023 drought, associated with Euglena sanguinea, is, to our knowledge, the first record a Euglena bloom in the Amazon. These microalgae are potentially ichthyotoxic, i.e., they pose risks to fish and, as a result, to the entire aquatic ecosystem (Zimba et al., 2010, 2017). Therefore, their blooms should be alert to aquatic ecologists and public health and water resources managers in the region. Here, we present and discuss the unprecedented occurrence of the E. sanguinea bloom in the Amazon waters and its potential environmental impacts. We highlight the relevance of the finding of these potentially harmful microalgae in natural Amazonian environments, providing new information into the impacts of extreme climate events on the ecology of the region. In line with this, we performed morphological and molecular identification, as well as quantification of cell density of E. sanguinea, detection of the euglenophycin toxin, and analysis of physical and chemical characteristics of the waters in the two large lakes identified to be affected in Amazon.

Material and Methods

Study Area

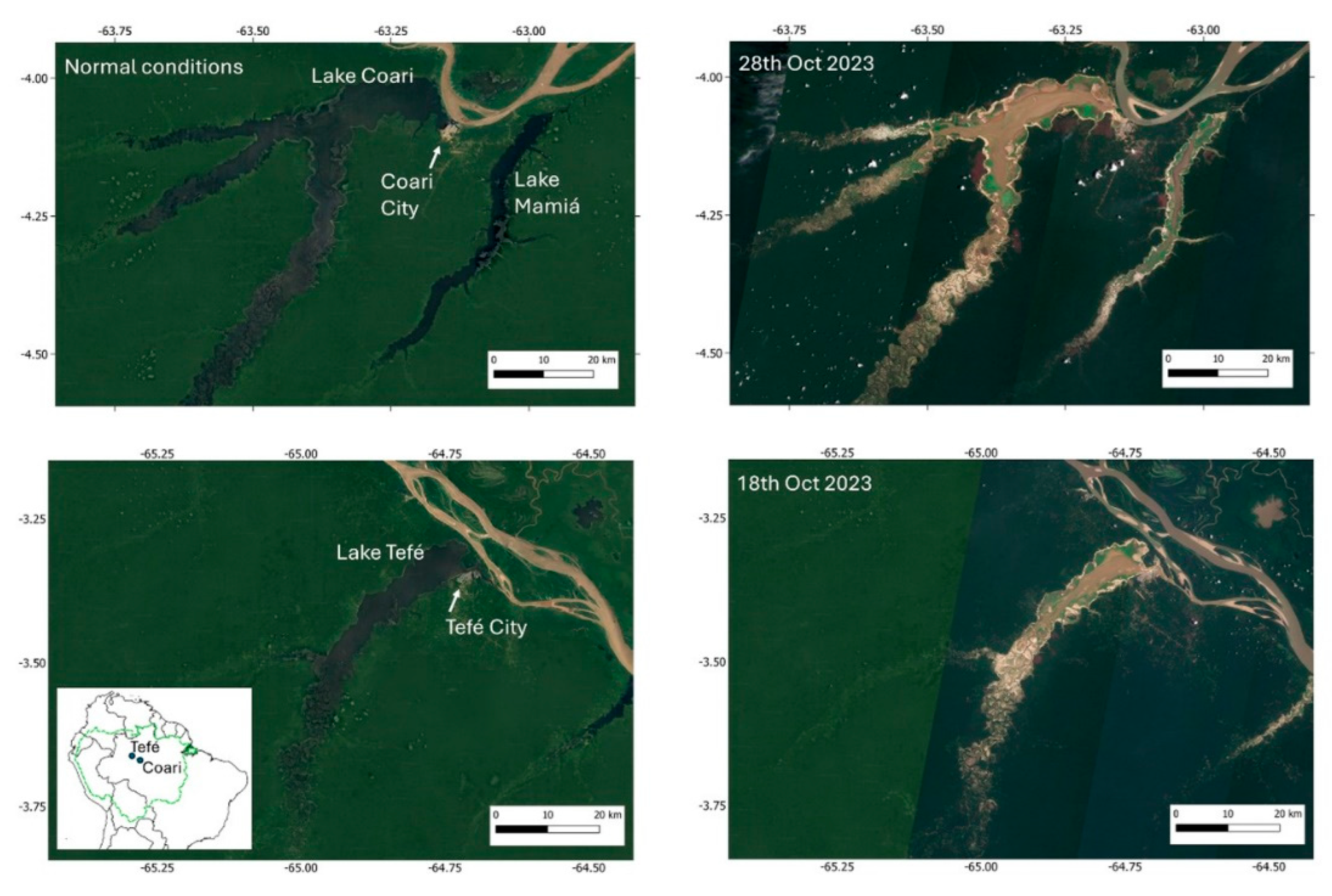

Tefé and Coari (

Figure 1) are “ria” lakes (also known as blocked fluvial valleys), a particular type of lake in the Amazoni associated with the backflooding of tributaries close to their confluences with the Amazon River (Irion et al., 2010; Latrubesse, 2012). The lakes are formed at the downstream end of the Tefé and Coari rivers, where the rivers widen near their confluence with the Amazon River. Although the lakes are black-water systems, they receive sediments from the Amazon specific times of the year. During extreme drought conditions, resuspension of bottom sediments leads to very turbid waters in both lakes (

Figure 1). At their downstream ends, a short channel connects the lakes to the Amazon River (known as the Solimões River in Brazil), measuring 8 km for Tefé and approximately 500 meters for Coari. Both are large lakes, with surface areas of 379 km² (Tefé) and 869 km² (Coari) during normal periods (Wang et al., 2023). However, during the 2023 drought, their surface areas were reduced by 75% (Tefé) and 78% (Coari) (Fleischmann et al., 2024). The urban centers of Tefé (population: 73,669) and Coari (population: 70,496) are located near their confluence with the Amazon. These are the largest cities upstream from Manaus in the state of Amazonas, Brazil.

Water Quality, Hydrology and Meteorology

We measured water levels continuously at a gauge station located at the Mamirauá Institute’s floating station, from 23rd Sep 2023 onward, where a local observer recorded the level twice a day (7 h and 17 h local time). The station is located in front of the city of Tefé. Water characteristics (water temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity and Secchi disk) were measured daily (around 16h local time) from Sep 28 to Nov 9, with a Hannah HI 98194 multiparameter probe at the surface, 50% of the water column depth, and near the bottom. Additionally, water temperature data were continuously recorded with a Hobo Pendant MX2201 logger located at the Mamirauá Institute’s floating station, at a 30 cm depth – during the drought, the whole water column was fully mixed, and the isotherm temperature was observed (same temperature in the whole water column) (Fleischmann et al., 2024). We analyzed turbidity, color, total nitrogen and total phosphorus in four water surface samples, from Oct 1 to 11, with Hanna H7011 turbidimeter, spectrophotometer Hach by wavelight 365 nm.

Phytoplankton Analysis

We collected samples from the ‘red spot’ in Tefé lake in front of the city of Tefé, in October 2023. In Coari lake, we collected samples from the ‘red spot’ in the center of the main lake channel in November 2023. Qualitative samples were collected by horizontal trawling using a conical plankton net with 20 µm mesh pore size. These samples were preserved with Transeau solution at a 6:3:1 ratio (Bicudo & Menezes, 2006).

For quantitative collections, we used a 5-liter graduated container, homogenized the sample, removed a 10 mL aliquot and preserved it with 0.3% Lugol's solution. In the laboratory, we analyzed the qualitative samples using successive slides under a standard optical microscope with 10x and 40x objectives. We selected 10 cells of each shape (elongated and round/oval) from each lake and measured the sizes of the

E. sanguinea cells using a standard optical microscope equipped with a micrometric eyepiece (10x objective). For quantitative analyses, we counted the number of cells in a Sedgewick-Rafter chamber. The final number of cells per volume was estimated with the following calculation:

where, C = number of cells counted, A = field area, DE = field depth, F = number of fields counted.

DNA Extraction, Amplification and Sequencing

To check for the presence of Euglena sanguinea in the bloom sample, we used the molecular marker nSSU rDNA (nuclear Small Subunit ribosomal DNA) species-specific for Euglena sanguinea, as described in Kulczycka et al (2018). The target region for the external primer was located between Helix 29 and 45 in the secondary structure of nSSU rDNA (sangF0: CTGYGGGCGCCACGCCCCCTTG and sangR0: ACGGACTTGCRGGGTTTCCCAGC) and for the internal primers between Helix 30 and 45 (sangF1: CGCCCCCTTGACCGAGAAATCCG, sangR1: GCCRGGGCCCRCAGAARACGAGG).

We used three types of templates: (1) DNA isolated from a Euglena sanguinea bloom from Tefé lake (species previously identified by microscopy); (2) DNA isolated from an environmental sample (Pampulha reservoir, Minas Gerais State, Brazil, with presence of Euglena species, but not Euglena sanguinea); (3) DNA isolated from a Euglena sp. culture (strain 463, CCMA UFSCar culture collection, Brazil). Total genomic DNA from cell cultures and environmental samples was extracted and purified with a DNA/RNA extraction Sample Flex Phot Kit (Phoneutria), according to the fabricant protocol.

The PCR amplification was performed as follows: a 25-μL reaction mixture contained 0.2 U DNA Polymerase, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5 pmol of each primer, reaction buffer and DNA template (10-20 ng). The PCR protocol consisted of two different rounds for a Nested PCR. The first round ran with the sangF0/R0 external primers, starting with 2 min at 98 °C, followed by nine initial cycles comprising the following steps: 30 s at 98 °C, 30 s at 62°C and 20s at 72 °C. For the second round, with the sangF1/R1 internal primers, 1 μL of the mixture from the first round was used and followed a similar protocol, starting with 2 min at 98 °C, followed by 39 cycles comprising steps of 15 s at 98 °C, 15 s at 60 °C (instead of 62°C), and 20 s at 72 °C. The final extension step was performed for 5 min at 72 °C. The PCRs were performed in a C-1000 Touch Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). The amplification PCR products were visualized in 1.2 % agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide, then they were purified (PCR purifying Kit Phoneutria) and sequenced by Fiocruz (Brazil) for the biomolecular confirmation of Euglena sanguinea species identity.

Sequence Processing and Phylogenetic Analysis

The DNA sequence from the Tefé lake bloom was compared by a BlastN search across public databases, including the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and the Joint Genome Institute. From this search, sequences from four Euglena sanguinea strains and four different species of Euglena were selected and aligned using Muscle (Edgar, 2004) alongside the Tefé lake bloom sequence. The species Trachelomonas echinata was used as the reference outgroup to route the tree. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using maximum parsimony (MP) analysis, with 1000 bootstrap replications. The construction of the tree was performed using the MEGA 11 (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis) software.

Toxin Analysis

We performed analyses of the presence of euglenophycin in the lakes’ water samples. For chemicals, methanol (MeOH >99.9%) was purchased from Tedia (Fairfield, USA) and water was purified in a Milli-Q® system (Merck Millipore, USA) to a resistance of 18.2 MΩ cm. Regarding sample preparation, water samples were filtered using a glass filter system connected to a vacuum pump. Glass microfiber filters from Whatman, with porosities of 2.7 and 0.7 µm, were used to facilitate filtration, especially for samples with high particulate content. The extraction of euglenophycin from water was performed using solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges with a polymeric phase (Strata-X 33 µm, 500 mg/6 mL). The cartridges were initially conditioned with 6.0 mL of MeOH, equilibrated with 6.0 mL of purified water, and then loaded with 1.0 L of the water sample. After loading, the sample was eluted with 6.0 mL of MeOH. The extracts were dried under a gentle flow of nitrogen gas, redissolved in 1.0 mL of MeOH, and filtered through a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) syringe filter (diameter 13 mm and pore size 0.45 μm) to remove suspended particles. The filtered extracts were then transferred to vials for chromatographic analysis. The analysis was conducted with Liquid Chromatography/High Resolution Mass spectrometry (LC/HRMS). Chromatographic separation was performed on an UltiMate 3000 ultra-high performance liquid chromatograph (Thermo Scientific, Germany) using a reversed-phase column (Shimpack XR-ODS III, 150mm length, 2.0 mm internal diameter, 2.2 µm particle size) at 40 ºC. The chromatographic method employed a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, with a mobile phase composed of water (A) and methanol (B), both containing 0.1% formic acid. The gradient program was as follows: 0–2 min, 10% B, 2–10 min, 10–90% B, 10–13 min, 10% B, 13–15 min, 10% B. The chromatograph was coupled in line to an Orbitrap Exploris™ 240 mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Germany). Acquisitions were conducted in positive electrospray ionization mode, with a capillary voltage of + 3000 V and a temperature of 300 ºC. Masses were scanned in the m/z 100–1000 range (240 K resolution at m/z 200), with an automatic gain control (AGC) set to accumulate 3 × 106 ions and a maximum injection time of 100 ms. Tandem MS analysis was performed at a resolution of 17.5 K, with the AGC set to 105 and a maximum injection time of 50 ms, using an isolation window of m/z 1.0.

Results

Euglena sanguinea Blooms in Tefé and Coari Lakes

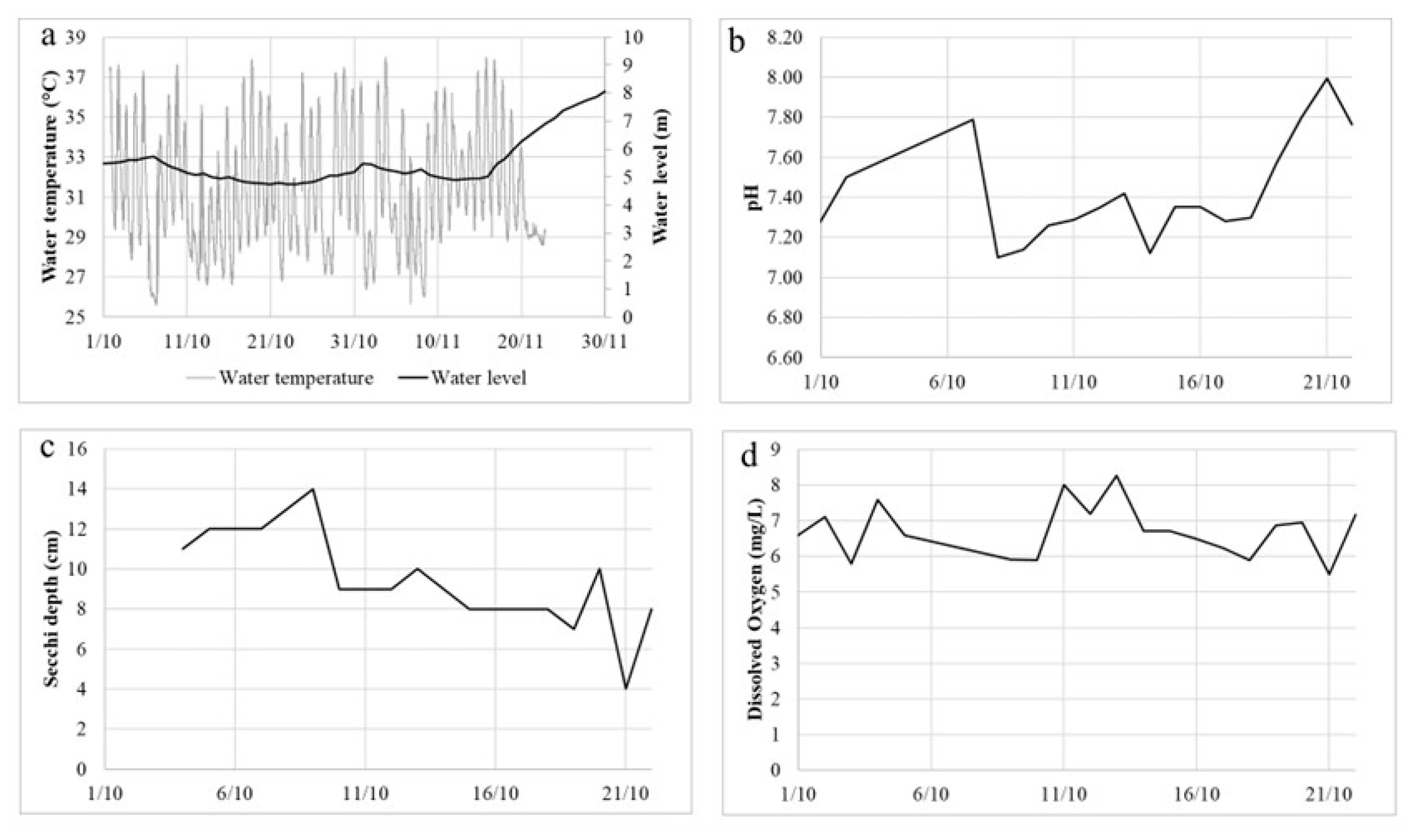

In Tefé lake, the flood peak typically occurs in June, and the typical dry season minimum level occurs in mid-October. After reaching water levels within normality in June, the lake levels started to decrease sharply in September 2023, reaching a decrease of around 30 cm/day of decreasing rate. This led to the lake rapid change from a black water system into a very turbid one (

Figure 1), with a Secchi depth of around 10 cm (

Figure 2c). In late September, a major dolphin mortality event started occurring, which culminated with the death of 209 dolphins dead in the lake over a short period of a few weeks (Marmontel et al., 2024). For this reason, water quality measurements started being collected at the beginning of October. Very high maximum water temperatures (up to 40.9°C in some parts of the lake) and diel variation (up to 13.3°C) were recorded in the lake (Fleischmann et al., 2024). At the Mamirauá Institute’s floating station, temperature as high as 38°C was measured (

Figure 2a). This extreme water temperature has been directly associated with intense incoming solar radiation, associated with a series of clear-sky days during the drought period (Fleischmann et al., 2024). Water levels started increasing considerably only by 16

th November (

Figure 2a). Dissolved oxygen concentrations were satisfactory, between 6 and 7 mg/L during most of the time (

Figure 2d), as well as pH, between 7 and 8 (

Figure 2b). The phosphorous concentration was up to 0.3 mgL

-1 and the maximum value of nitrogen concentration was 0.37 mgL

-1 (

Table 1).

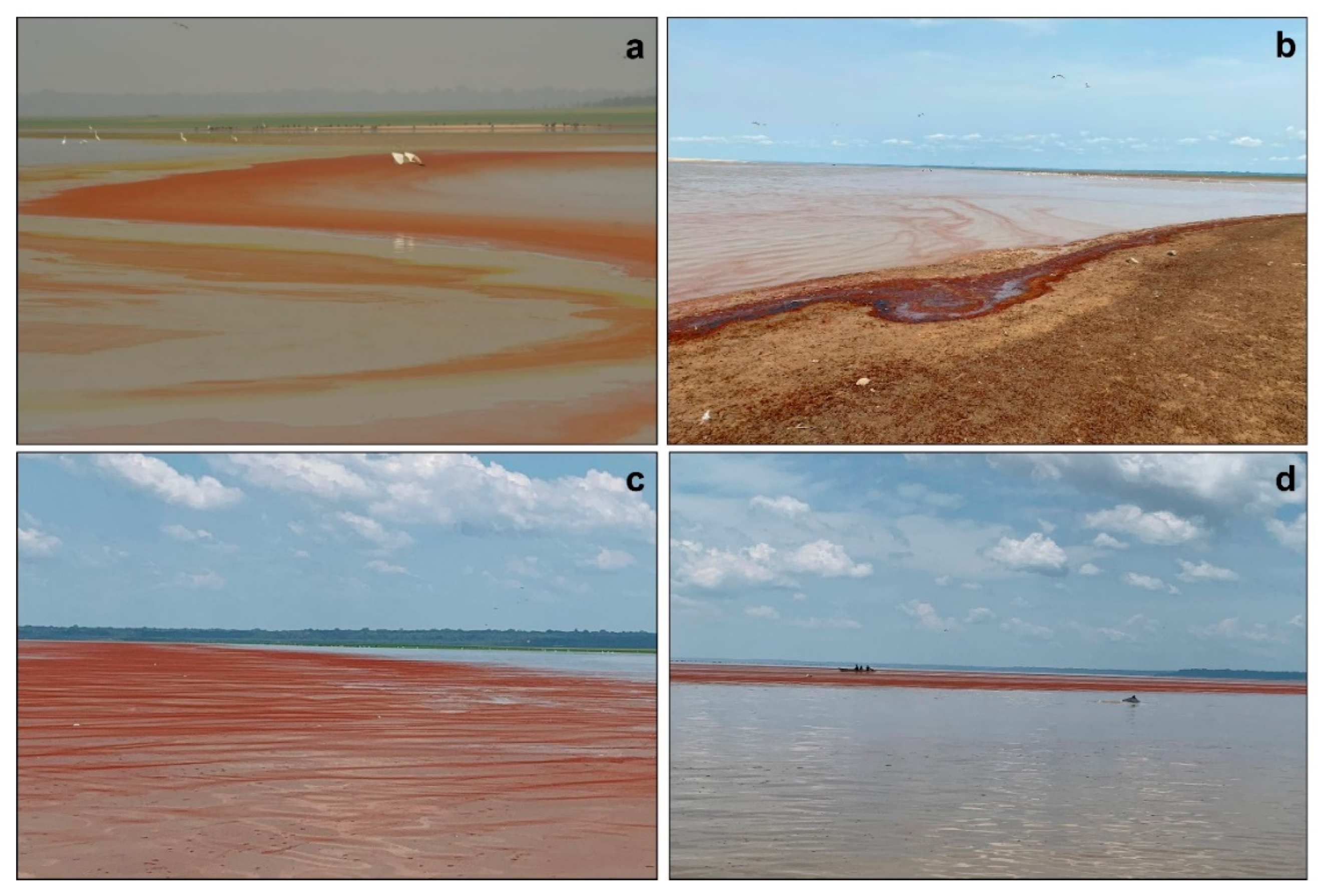

During the extreme drought in 2023, we observed a reddish bloom in both lakes (

Figure 3).

In situ observations began on October 4 and continued until the lake's water levels rose significantly. The bloom was observed for four consecutive weeks, appearing each morning at 8:00 a.m., disappearing during the day, and reappearing the following morning.

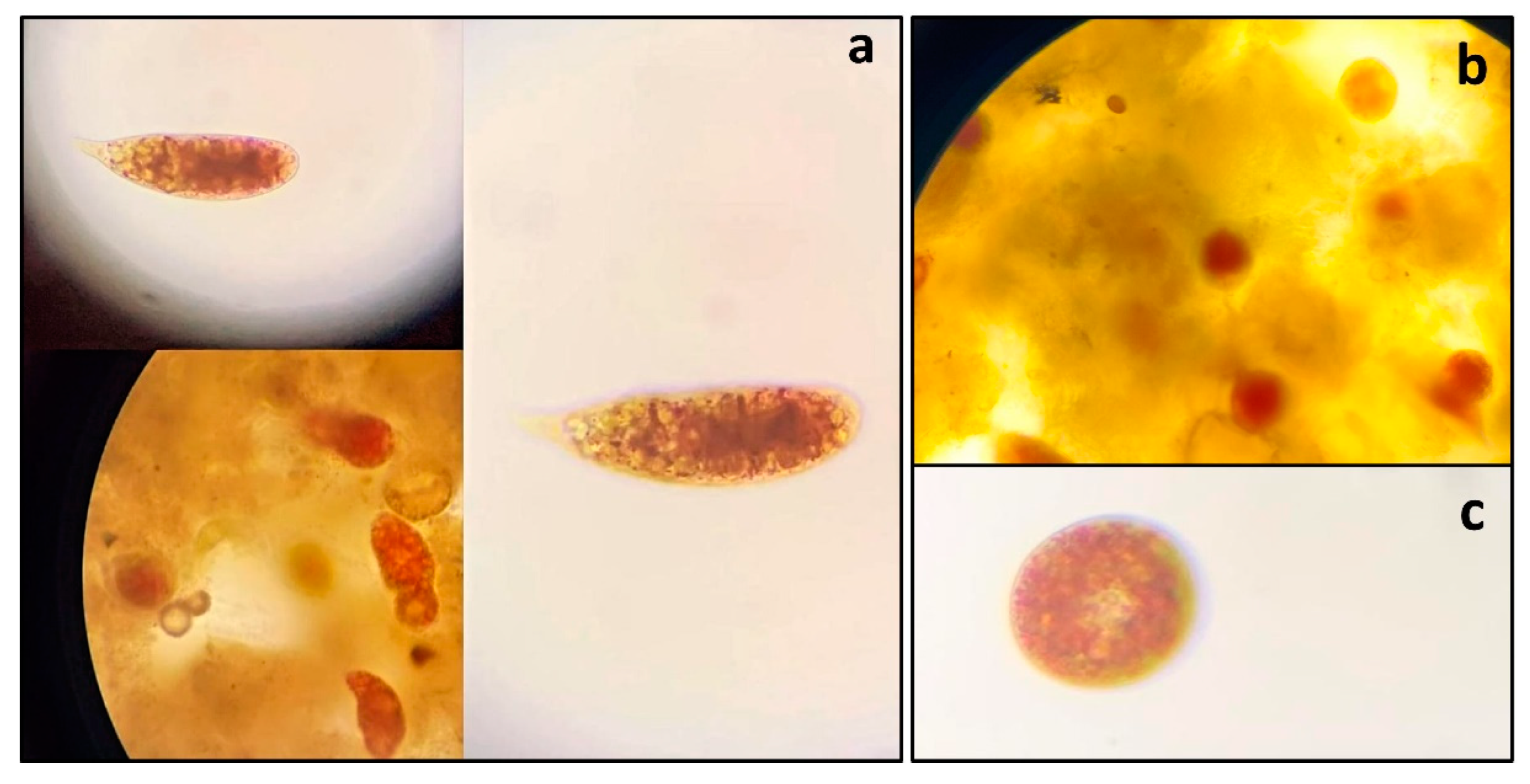

This red color was attributed to the predominance of the freshwater microalgae

Euglena sanguinea Ehrenberg. The

E. sanguinea cells exhibited elongated and round shapes, appearing in both green and red colors (

Figure 4). In Tefé lake, the elongated cells had an average size of 85.4 ± 10.6 µm, while the round cells had an average size of 38.1 ± 4.98 µm. In Coari lake, the elongated cells had an average size of 64.9 ± 4.3 µm, and the round cells had an average size of 48.4 ± 5.5 µm. The density of

E. sanguinea was 64,700 cells/mL in Tefé lake and 42,000 cells/mL in Coari lake. The phytoplankton composition in Tefé lake consisted of five classes: Chlorophyceae (3 taxa), Cyanophyceae (3 taxa), Bacillariophyceae (4 taxa), Zygnemaphyceae (7 taxa), and Euglenophyceae (1 taxon), as shown in

Table 2.

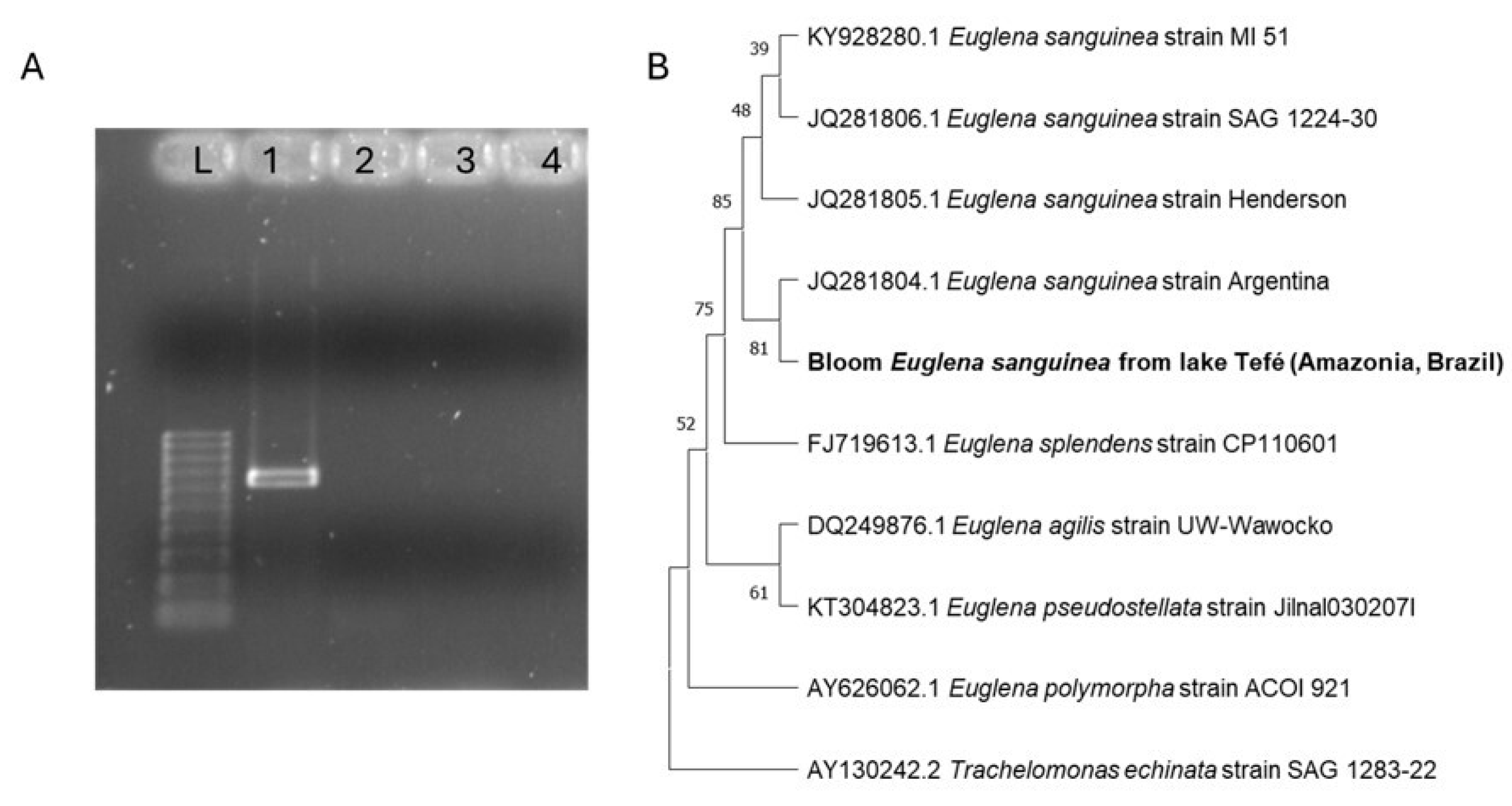

Molecular Identification of Euglena sanguinea

Figure 5A shows an agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products obtained by nested PCR using the external sangF0/R0 and internal sangF1/R1 primers. The bands on the first column "L" correspond to the molecular 100 bp ladder. Column 1 shows a band that corresponds to the bloom sample of Tefé lake, confirming the presence of an organism that was amplified with the species-specific primer for

Euglena sanguinea. The two next columns (2 and 3) do not show any band and represent samples from Pampulha lake (2) and from a

Euglena sp. culture (3), respectively, confirming the absence of any

E. sanguinea in these samples. The last column (4) corresponds to the negative control.

The phylogenetic tree represented in

Figure 5 (B) is based on 18S rRNA

Euglena sequences obtained from the GenBank, aligned with the sequence found in the Tefé lake bloom. The tree shows how all the

E. sanguinea strains are in separate branches from other

Euglena species and confirms the presence of

E. sanguinea in the bloom sample of Tefé lake.

Toxin Detection

The LCHRMS analysis indicated the presence of euglenophycin in all water samples collected on different days from Tefé lake. Although a standard for euglenophycin was not available, the compound was tentatively identified based on its exact mass and fragmentation pattern (

Figure 6). The molecular ion was detected at m/z 306.2793 (mass error of 0.65 ppm), with major product ions detected at m/z 288.2688 (mass error of 0.69 ppm), 274.2530 (mass error of 0.36 ppm), 262.2530 (mass error of 0.38 ppm), 248.2374 (mass error of 0.40 ppm), and 246.2217 (mass error of 0.40 ppm). The product ion at m/z 288, resulting from the neutral loss of H

2O (18 u), was previously reported as a predominant ion by Gutierrez et al. (2013) for euglenophycin extracted and purified from

Euglena sanguinea cultures. This loss was also highly favored in our analysis. The other product ions identified were observed as minor fragments and resulted from various possible neutral losses of alcohol. Specifically, the loss of CH

3OH (32 u) from euglenophycin produces the product ion at m/z 274, the loss of CH

2CHOH (44 u) results in the ion at m/z 262, the loss of CH

3CHCHOH (58 u) gives the ion at m/z 248, and the loss of CH

3CH

2CH

2OH (60 u) produces the ion at m/z 246.

Discussion

The Bloom in Tefé and Coari Lakes

Euglena sanguinea belongs to the Euglenophyceae group, consisting of freshwater microalgae that can be photosynthetic and/or heterotrophic (Rosowski, 2003). Under favorable environmental conditions, such as temperatures above 25 °C and high solar radiation, these organisms can form blooms on the water's surface, which may appear reddish or green (Jahn, 1946). The blood-red color results from the presence of granules called hematochromes, which protect the chlorophyll in the cells when exposed to intense solar radiation (Gojdics, 1939; Jahn, 1946; Lee, 2008). The dispersion of hematochromes throughout the cells causes them to turn red, making the bloom visible to the naked eye on the water's surface (Wołowski et al., 2024).

The concentration of nitrogen and phosphorus in Tefé lake is within the typical levels found in blackwater lakes in the Amazon (Schmidt, 1976; Rai and Hill, 1981), not indicating eutrophication or nutrient imbalance. Therefore, it was not considered a determining factor for the bloom. The bloom of E. sanguinea was favored by (i) the reduction in water levels, which led to a high concentration of suspended sediments, promoting not only photosynthetic but also heterotrophic feeding for this species, (ii) high solar radiation, which triggered the production of hematochromes, along with elevated temperatures exceeding 37 °C in Tefé lake, and (iii) the positive phototaxis of these organisms, causing them to move towards light to optimize energy capture for photosynthesis (Gerber and Häder, 1994).

These organisms commonly exhibit round or oval cysts with thick walls (Rosowski, 2003). Vuuren and Levanets (2020) classified E. sanguinea cells into two types: large and small (elongated and oval). According to the average cell sizes observed in this study, the E. sanguinea cells in Tefé lake were categorized as large and elongated, while in Coari lake, the average size of the elongated cells was classified as small. Round or oval cells in both lakes were generally classified as small. Overall, these differences in cell size may influence their ability to compete for nutrients with other microalgae species, with larger cells potentially having a greater capacity to produce and accumulate proteins. Furthermore, size variations are associated with the rapid cell division that occurs under stressful conditions, leading to the formation of various types of palimeloid stages (Hindák et al., 2000; Wołowski et al., 2024).

In addition to the presence of

E. sanguinea, we also identified other species of microalgae (

Table 1). All these phytoplankton species have been previously recorded in blackwater lakes in the Amazon (Melo et al., 2005). Under “normal” conditions, the composition of the phytoplankton community can be influenced by environmental (e.g., temperature, pH, total nitrogen, total phosphorus, water level variation) and biological factors (e.g., predation by zooplankton and/or ciliates; Reynolds et al., 2002). High water level variation throughout the year, which influences the composition and diversity of the phytoplankton community, is a well-documented phenomenon in several Amazonian lakes (Fassoni-Andrade et al., 2021). For instance, a smaller number of taxa is typically observed during the flood period in whitewater lakes (Moresco et al., 2017), and significant differences are found between the species during dry and flood periods in the floodplain and blackwater lakes (Melo et al., 2005; Raupp et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2013). While we identified euglenophycin was identified in all water samples from Tefé and Coari lakes, no major fish mortality event was observed in these two lakes during the blooms, and preliminary analyses (A. Hercos,

pers. comm.) indicated no direct relationship between the phytoplankton bloom and fish mortality in the lakes.

Molecular Identification of Euglena sanguinea

With the primers selected in this study it was possible to successfully validate the identification of E. sanguinea in the environmental bloom sample of Tefé lake. The choice of an appropriate molecular marker can be instrumental in the identification of this species, since identifying E. sanguinea may pose a challenge, even for experts in the field (Karnkowska-Ishikawa et al., 2013). In this study, we employed specific primers targeting the nSSU rDNA region of E. sanguinea. These primers were specifically designed and validated in the study conducted by Kulczycka et al. (2018) and were found to be highly effective for the precise molecular identification of E. sanguinea. Because of the potential toxicity of this species (Zimba et al., 2010), correct identification is especially important.

In the literature, more than 150 species have been described for the genus Euglena (Mullner et al., 2001) and they have been grouped differently based on several criteria, mostlym morphological (for example, Bourrelly, 1970). However, more recent studies using the SSU rDNA gene suggested that some of these traditional classifications were not supported by molecular results (Linton et al., 2000). Therefore, phylogenetic and molecular studies using the SSU rDNA gene may be very useful to better establish taxonomic identifications in euglenoids (Müllner et al., 2001).

Phytoplankton Blooms in a Changing Amazon: Perspectives and Monitoring Gaps

In a scenario where algal blooms are known to be driven by high nutrient concentrations and suitable temperatures, several studies on river blooms suggest that, when nutrients and temperatures are optimal, changes in the river’s hydrological regime become the primary factors driving blooms, with cumulative and long-term effects (Cheng et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2019). Therefore, in a scenario where water level variations are not yet influenced by climate change, changes in the phytoplankton community can be considered “normal” for the region. However, in the current context, where these variations are being strongly impacted by climate change, different types of changes may occur. There could be positive changes, where the phytoplankton community, composed of species that are not harmful to other food chain levels, adapts to the new conditions. Negative changes could occur, characterized as harmful algal blooms (HABs) —proliferations of toxic aquatic microalgae that have become a global problem due to increasing nutrient levels, global climate change, and the introduction of invasive species, which can harm other links in the food chain (Reid et al., 2024).

Considering that algal blooms in natural freshwater environments in the Amazon are becoming more frequent, it is necessary to adopt specific measures for such as Coari and Tefé lakes, which also have major socioeconomic relevance for food security (e.g., for fisheries and access to food markets) and transportation of local populations in general. One such measure is the biomonitoring of the phytoplankton community under natural conditions, which is almost absent in large Amazon lakes. It would be essential to understand how this environment and the phytoplankton community change during different stages of the hydrological regime as well as in years of extreme conditions. Such a monitoring program would allow the identification of potentially harmful species, such as those that produce toxins. However, this knowledge alone is not sufficient to prevent or predict blooms. Therefore, it is essential to invest in predictive models, such as remote sensing monitoring, which is already well-established in oceanic aquatic ecosystems (Wang et al., 2024), but specifically tailored to the white- and blackwater systems of the Amazon.

Conclusions

Here we documented the first bloom of E. sanguinea in the Amazon Basin (and in South America), a potentially icthyotoxic phytoplankton. Euglenophycin, a toxin that can be harmful to fish, was identified in all water samples from Tefé and Coari lakes, yet its impact on local Amazonian fish could not be measured. No major fish mortality was observed surrounding the algae blooms, but we highlight the need to further investigate the potential of E. sanguinea blooms on Amazon fish, given the likelihood of such events occurring again in large Amazon lakes in the near future.

The presence of diverse species in the phytoplankton community in Tefé lake during the extreme drought of 2023 underscores the need for biomonitoring the dynamics of these organisms, particularly their abundance and composition in relation to water level variations. This is essential for facilitating future comparisons during extreme events, and to shed light on potentially harmful blooms that may threaten Amazonian human populations and aquatic ecosystems. We emphasize the importance of recording and fostering monitoring programs for algae blooms in the Amazon, as climate change may intensify these events. Documenting algae blooms across the region is crucial to alert ecologists and managers to the ongoing environmental risks under climate change, and to emphasize the need for mitigation and adaptation strategies in managing the region’s water resources.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available, upon reasonable request from the corresponding author Raize Castro Mendes. The dataset is not publicly available because the data contains information that compromises the privacy of participants in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest that could perceive to influence the results of the research.

References

- Albert, J.S.; Carnaval, A.C.; Flantua, S.G.A.; Lohmann, L.G.; Ribas, C.C.; Riff, D.; Carrillo, J.D.; Fan, Y.; Figueiredo, J.J.P.; Guayasamin, J.M.; et al. Human impacts outpace natural processes in the Amazon. Science 2023, 379, eabo5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicudo, C.E.M. & Menezes, M., 2006. Gêneros de Águas Continentais do Brasil – chave de identificação e descrições, 2ª ed. São Carlos: Rima Editora, 502 p.

- Bourrelly, P. , 1970. Les Algues d’Eau Douce. Troisiéme partie – Euglénophytes. Ed. N. Boubée & Cie, Paris, pp. 115–184.

- Cheng, B.; Xia, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Hu, S.; Guo, F.; Ma, S. Characterization and causes analysis for algae blooms in large river system. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokulil, M.T. & Teubner, K., 2011. Eutrophication and climate change: Present situation and future scenarios. In: Ansari, A.A., Gill, S.S., Lanza, G.R., Rast, W. (Eds.), Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Control. Springer Science+Business Media B.V., New York, pp. 1–16.

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza, J.-C.; Marengo, J.A.; Schongart, J.; Jimenez, J.C. The new historical flood of 2021 in the Amazon River compared to major floods of the 21st century: Atmospheric features in the context of the intensification of floods. Weather. Clim. Extremes 2021, 35, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.-C.; Jimenez, J.C.; Marengo, J.A.; Schongart, J.; Ronchail, J.; Lavado-Casimiro, W.; Ribeiro, J.V.M. The new record of drought and warmth in the Amazon in 2023 related to regional and global climatic features. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.; Gleick, P.H.; Asayama, S.; Attig-Bahar, F.; Behera, S.; von Braun, J.; Colwell, R.R.; Chapagain, A.K.; El-Beltagy, A.S.; Kennel, C.F.; et al. Critical hydrologic impacts from climate change: addressing an urgent global need. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassoni-Andrade, A.C.; Fleischmann, A.S.; Papa, F.; de Paiva, R.C.D.; Wongchuig, S.; Melack, J.M.; Moreira, A.A.; Paris, A.; Ruhoff, A.; Barbosa, C.; et al. Amazon Hydrology From Space: Scientific Advances and Future Challenges. Rev. Geophys. 2021, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, A.S.; Papa, F.; Hamilton, S.K.; Fassoni-Andrade, A.; Wongchuig, S.; Espinoza, J.-C.; Paiva, R.C.D.; Melack, J.M.; Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Castello, L.; et al. Increased floodplain inundation in the Amazon since 1980. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 034024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.R.; Vieira, P.C.S.; Kujbida, P.; da Costa, I.A.S. Cyanobacterial occurrence and detection of microcystins and saxitoxins in reservoirs of the Brazilian semi-arid. Acta Limnol. Bras. 2015, 27, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, S.; Hã¤Der, D.-P. Effects of enhanced UV-B irradiation on the red coloured freshwater flagellate Euglena sanguinea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1994, 13, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojdics, M. Some Observations on Euglena sanguinea Ehrbg. Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 1939, 58, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, D.B.; Rafalski, A.; Beauchesne, K.; Moeller, P.D.; Triemer, R.E.; Zimba, P.V. Quantitative Mass Spectrometric Analysis and Post-Extraction Stability Assessment of the Euglenoid Toxin Euglenophycin. Toxins 2013, 5, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindák, F.; Wolowski, K.; Hindáková, A. Cysts and their formation in some neustonic Euglena species. Ann. de Limnol. - Int. J. Limnol. 2000, 36, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwaran, A.; Kayode, A.J.; Moloantoa, K.M.; Khetsha, Z.P.; Unuofin, J.O. Cyanobacteria Harmful Algae Blooms: Causes, Impacts, and Risk Management. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC, 2023. Sections. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee & J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 35–115. [CrossRef]

- Irion, G. , et al., 2010. Development of the Amazon Valley During the Middle to Late Quaternary: Sedimentological and Climatological Observations. In: Junk, W., et al. (Eds.), Amazonian Floodplain Forests. Springer Science+Business Media B.V., pp. 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Jahn, T.L. The Euglenoid Flagellates. Q. Rev. Biol. 1946, 21, 246–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnkowska-Ishikawa, A. , Milanowski, R., Triemer, R.E., Zakryś, B., 2013. A redescription of morphologically similar species from the genus Euglena: E. laciniata, E. sanguinea, E. sociabilis, and E. splendens. J. Phycol., 49, 616–626.

- Kulczycka, A.; Łukomska-Kowalczyk, M.; Zakryś, B.; Milanowski, R. PCR identification of toxic euglenid species Euglena sanguinea. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 1759–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapola, D.M.; Pinho, P.; Barlow, J.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Berenguer, E.; Carmenta, R.; Liddy, H.M.; Seixas, H.; Silva, C.V.J.; Silva-Junior, C.H.L.; et al. The drivers and impacts of Amazon forest degradation. Science 2023, 379, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latrubesse, E.M. , 2012. Amazon lakes. In: Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.E. Phycology; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, K.; Qian, H.; Yang, H.; Niu, Y.; Qin, B.; Zhu, G.; Woolway, R.I.; et al. The unprecedented 2022 extreme summer heatwaves increased harmful cyanobacteria blooms. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 896, 165312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, E.W.; Nudelman, M.A.; Conforti, V.; Triemer, R.E. A MOLECULAR ANALYSIS OF THE EUGLENOPHYTES USING SSU RDNA. J. Phycol. 2000, 36, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Espinoza, J.C. Extreme seasonal droughts and floods in Amazonia: causes, trends and impacts. Int. J. Clim. 2016, 36, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmontel, M.; Fleischmann, A.; Val, A.; Forsberg, B. Safeguard Amazon’s aquatic fauna against climate change. Nature 2024, 625, 450–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, S. , Rebelo, S.R.M., Souza, K.F., Menezes, M. & Torgan, L.C., 2005. Fitoplâncton. In: Santos-Silva, E.N., Aprile, F.M., Scudeller, V.V., Melo, S. (Eds.), Biotupé: Meio Físico, Diversidade Biológica e Sociocultural do Baixo Rio Negro, Amazônia Central. Editora INPA, Manaus, Cap. 5.

- Moresco, G.A.; Bortolini, J.C.; Dias, J.D.; Pineda, A.; Jati, S.; Rodrigues, L.C. Drivers of phytoplankton richness and diversity components in Neotropical floodplain lakes, from small to large spatial scales. Hydrobiologia 2017, 799, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllner, A.N. , Angeler, D.G., Samuel, R., Linton, E.W. & Triemer, R.E., 2001. Phylogenetic analysis of phagotrophic, phototrophic and osmotrophic euglenoids by using the nuclear 18S rDNA sequence. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 51, 783–791.

- Pinheiro, M.M.d.L.; Santos, B.L.T.; Filho, J.V.D.; Pedroti, V.P.; Cavali, J.; dos Santos, R.B.; Nishiyama, A.C.O.C.; Guedes, E.A.C.; Schons, S.d.V. First monitoring of cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in freshwater from fish farms in Rondônia state, Brazil. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, H. & Hill, G., 1981. Physical and chemical studies of Lago Tupé, a central Amazonian blackwater “Ria Lake”. Hidrobiol. Hydrogr., 66, 37-82.

- Raupp, S.V. , Torgan, L. & Melo, S., 2009. Planktonic diatom composition and abundance in the Amazonian floodplain Cutiuaú Lake are driven by the flood pulse. Acta Limnol. Bras., 21, 227–234.

- Reid, N.; Reyne, M.I.; O’neill, W.; Greer, B.; He, Q.; Burdekin, O.; McGrath, J.W.; Elliott, C.T. Unprecedented Harmful algal bloom in the UK and Ireland’s largest lake associated with gastrointestinal bacteria, microcystins and anabaenopeptins presenting an environmental and public health risk. Environ. Int. 2024, 190, 108934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, C.S.V. , Huszar, C., Kruk, L., Naselli, L. & Melo, S., 2002. Towards a functional classification of the freshwater phytoplankton. J. Plankton Res., 24, 417–428.

- Rosowski, J.R. , 2003. Photosynthetic euglenoids. In: Wehr, J.D., Sheath, R.G. (Eds.), Freshwater Algae of North America: Ecology and Classification. San Diego, California, 918p.

- de Sá, L.L.C.; Vieira, J.M.d.S.; Mendes, R.d.A.; Pinheiro, S.C.C.; Vale, E.R.; Alves, F.A.d.S.; de Jesus, I.M.; Santos, E.C.d.O.; da Costa, V.B. Ocorrência de uma floração de cianobactérias tóxicas na margem direita do Rio Tapajós, no Município de Santarém (Pará, Brasil). 2010, 1, 159–166. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, G.W. , 1976. Primary production of phytoplankton in three types of Amazonian waters. IV. On the primary productivity of phytoplankton in a Bay of the lower Rio Negro (Amazonas, Brazil). Amazoniana, 5, 517–528.

- Silva, I.G.; Moura, A.N.; Dantas, E.W. Phytoplankton community of Reis lake in the Brazilian Amazon. An. da Acad. Bras. de Cienc. 2013, 85, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.S.; Brown, F.; de Oliveira Sampaio, A.; Silva, A.L.C.; dos Santos, N.C.R.S.; Lima, A.C.; de Souza Aquino, A.M.; da Costa Silva, P.H.; do Vale Moreira, J.G.; Oliveira, I.; et al. Amazon climate extremes: Increasing droughts and floods in Brazil’s state of Acre. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 21, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terassi, P.M.d.B.; Galvani, E.; Gobo, J.P.A.; Oscar-Júnior, A.C.d.S.; Luiz-Silva, W.; Sobral, B.S.; de Gois, G.; Biffi, V.H.R. Exploring climate extremes in Brazil’s Legal Amazon. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 38, 1403–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vuuren, S.J.; Levanets, A. Mass developments ofEuglena sanguineaEhrenberg in South Africa. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 2020, 46, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Lin, Q.; Xiao, W.; Huang, B.; Lu, W.; Chen, N.; Chen, J. Modeling of algal blooms: Advances, applications and prospects. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołowski, K.; Duangjan, K.; Dempster, T.; Tsarenko, P.; Poniewozik, M.; Koreiviene, J. Colour range of euglenoid (Euglenophyceae) blooms. Plant Fungal Syst. 2024, 69, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Dou, M.; Hou, X.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Z. Multi-factor identification and modelling analyses for managing large river algal blooms. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimba, P.V.; Moeller, P.D.; Beauchesne, K.; Lane, H.E.; Triemer, R.E. Identification of euglenophycin – A toxin found in certain euglenoids. Toxicon 2010, 55, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimba, P.V.; Huang, I.-S.; Gutierrez, D.; Shin, W.; Bennett, M.S.; Triemer, R.E. Euglenophycin is produced in at least six species of euglenoid algae and six of seven strains of Euglena sanguinea. 63, 84. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).