Submitted:

11 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

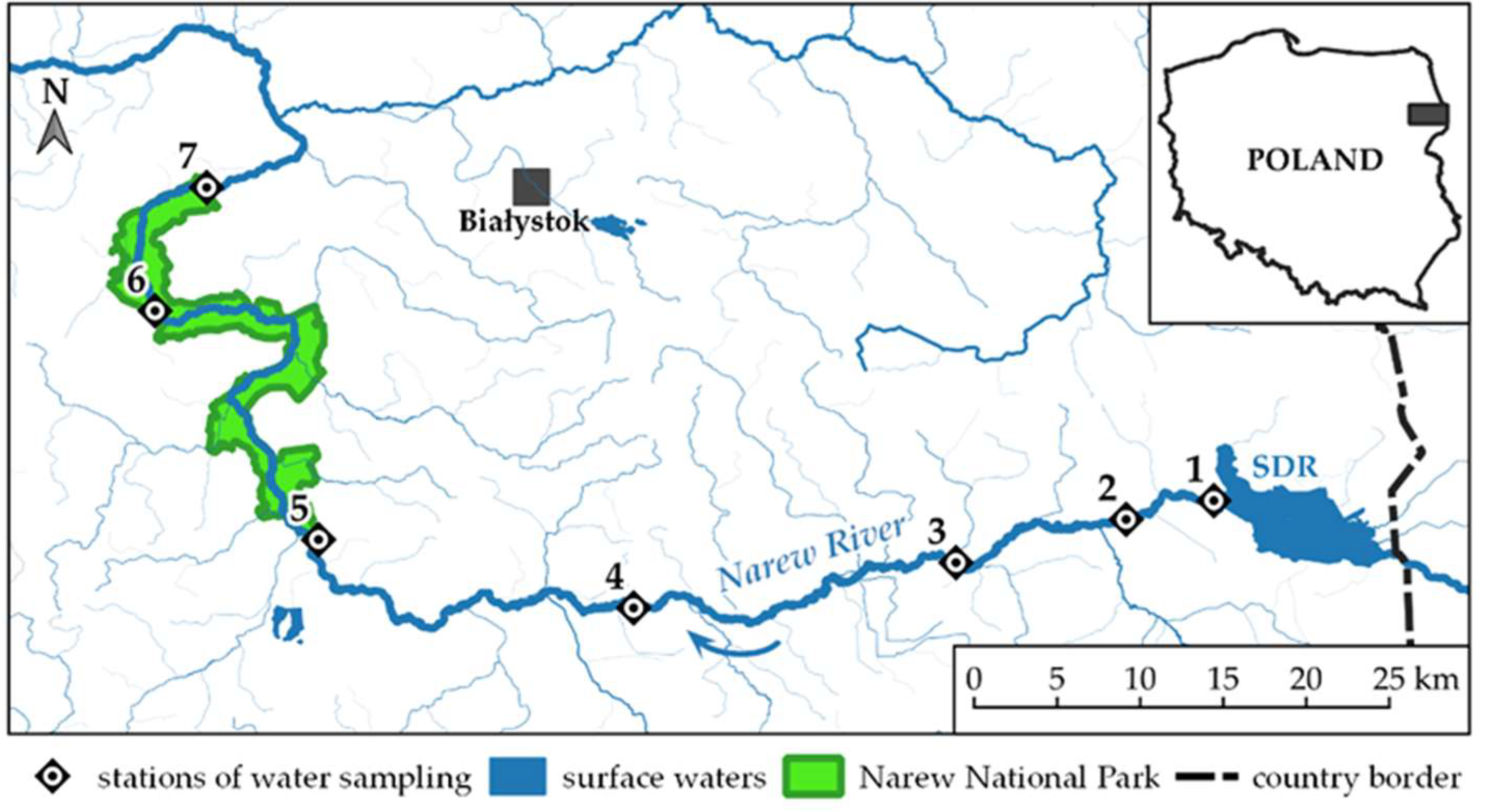

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Water Chemistry

2.3. Phytoplankton and Secondary Metabolites

3. Results

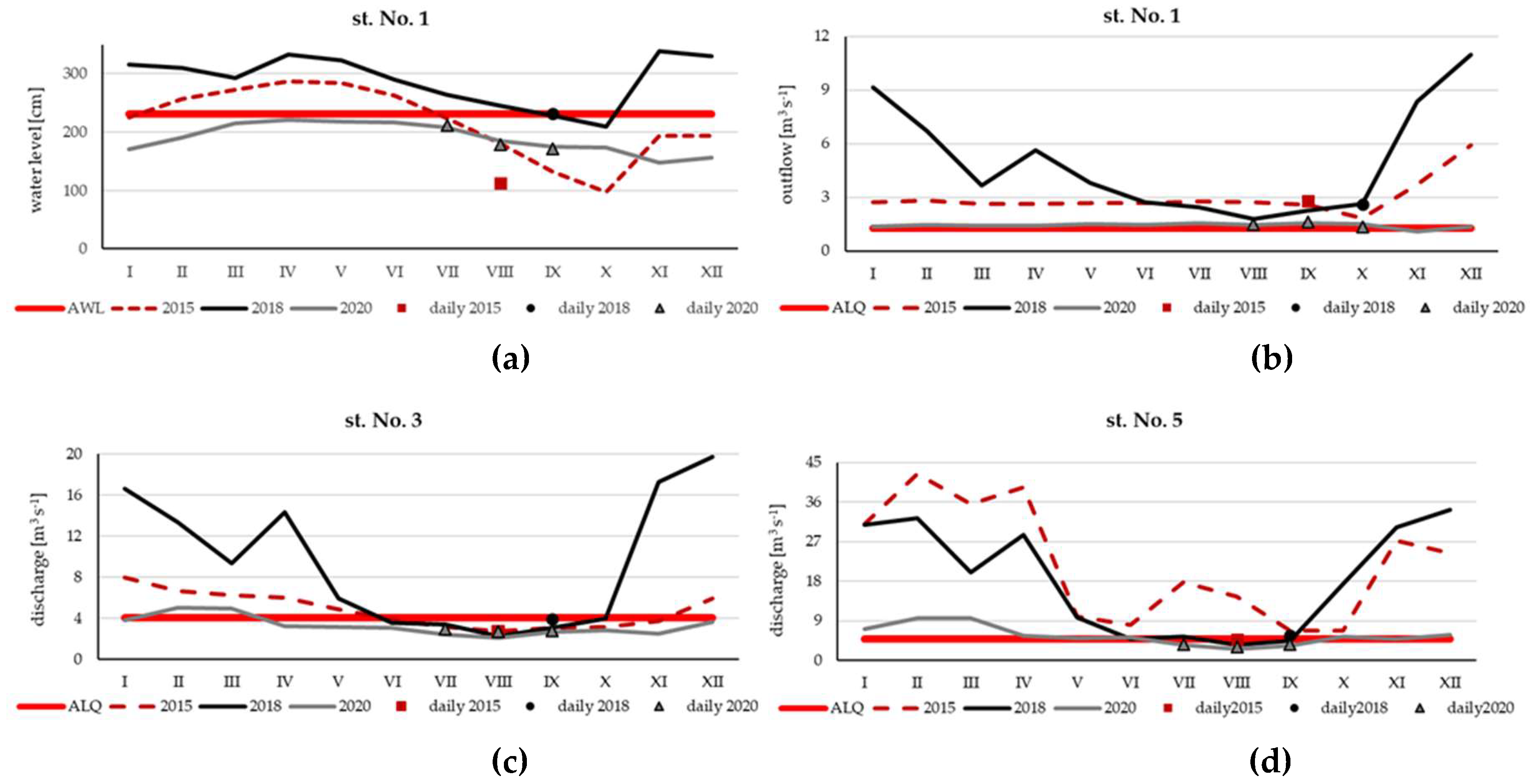

3.1. Hydrological Conditions

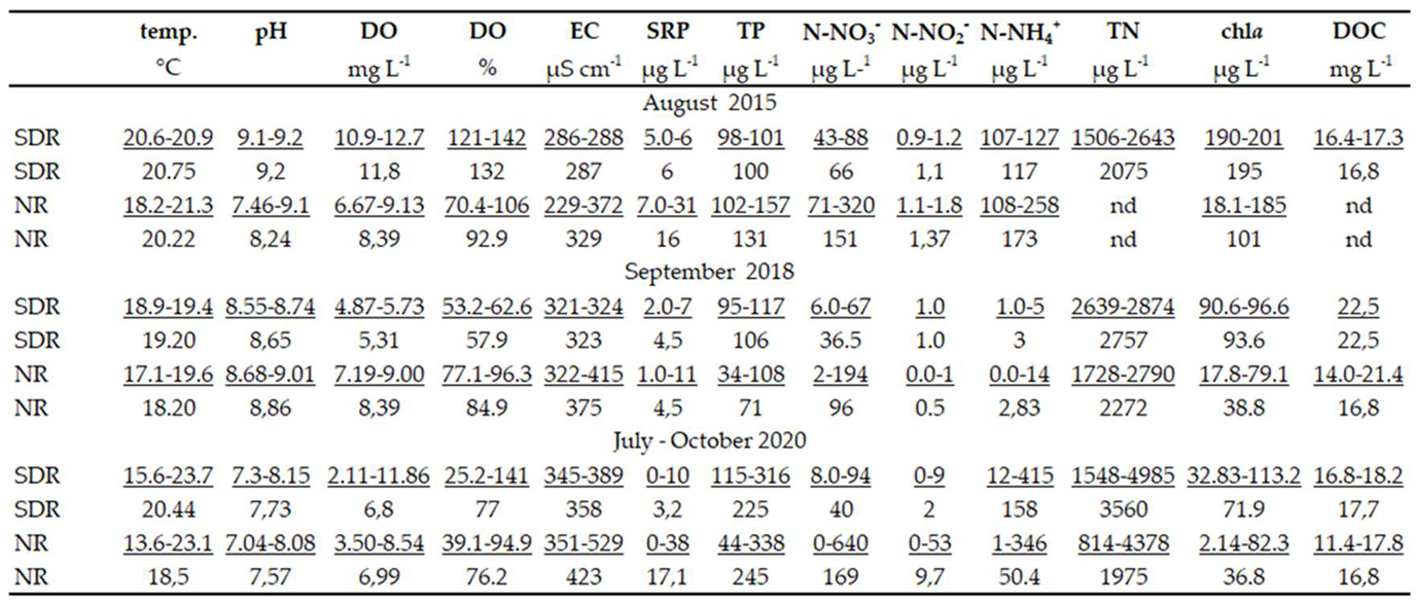

3.2. Water Parameters

|

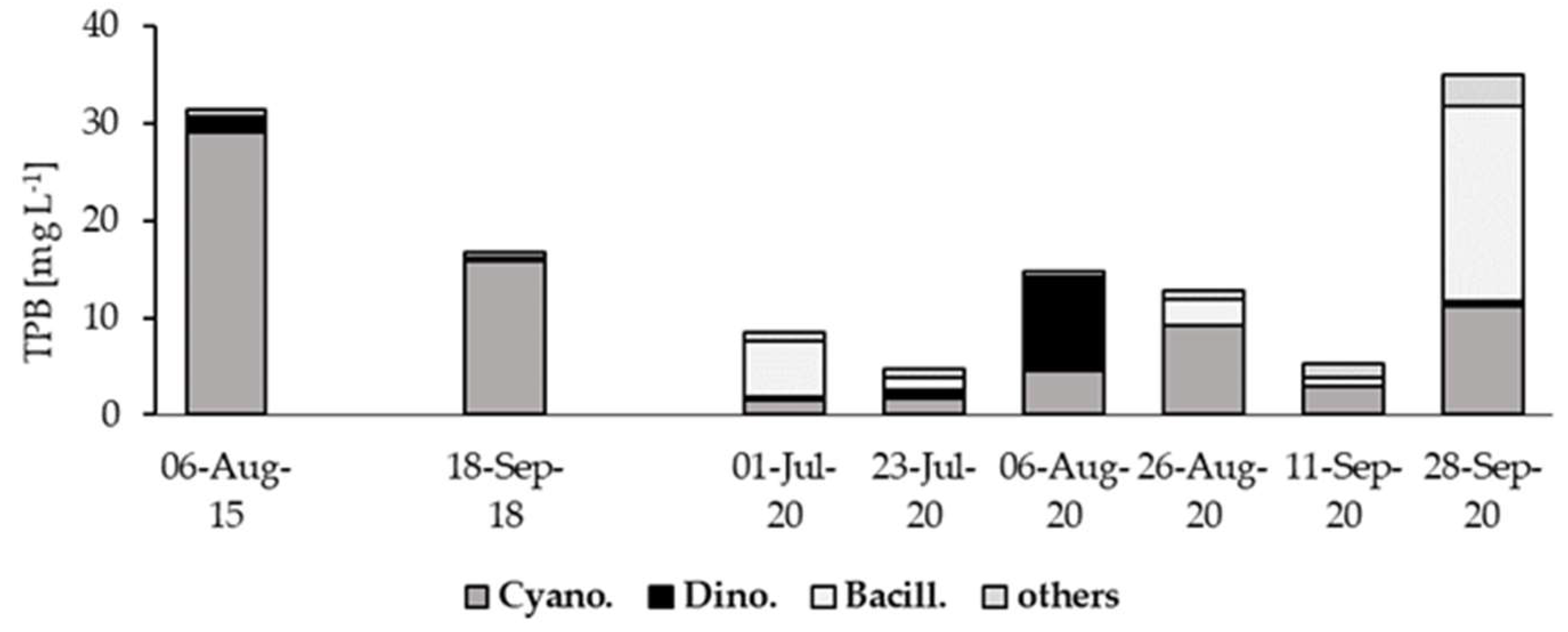

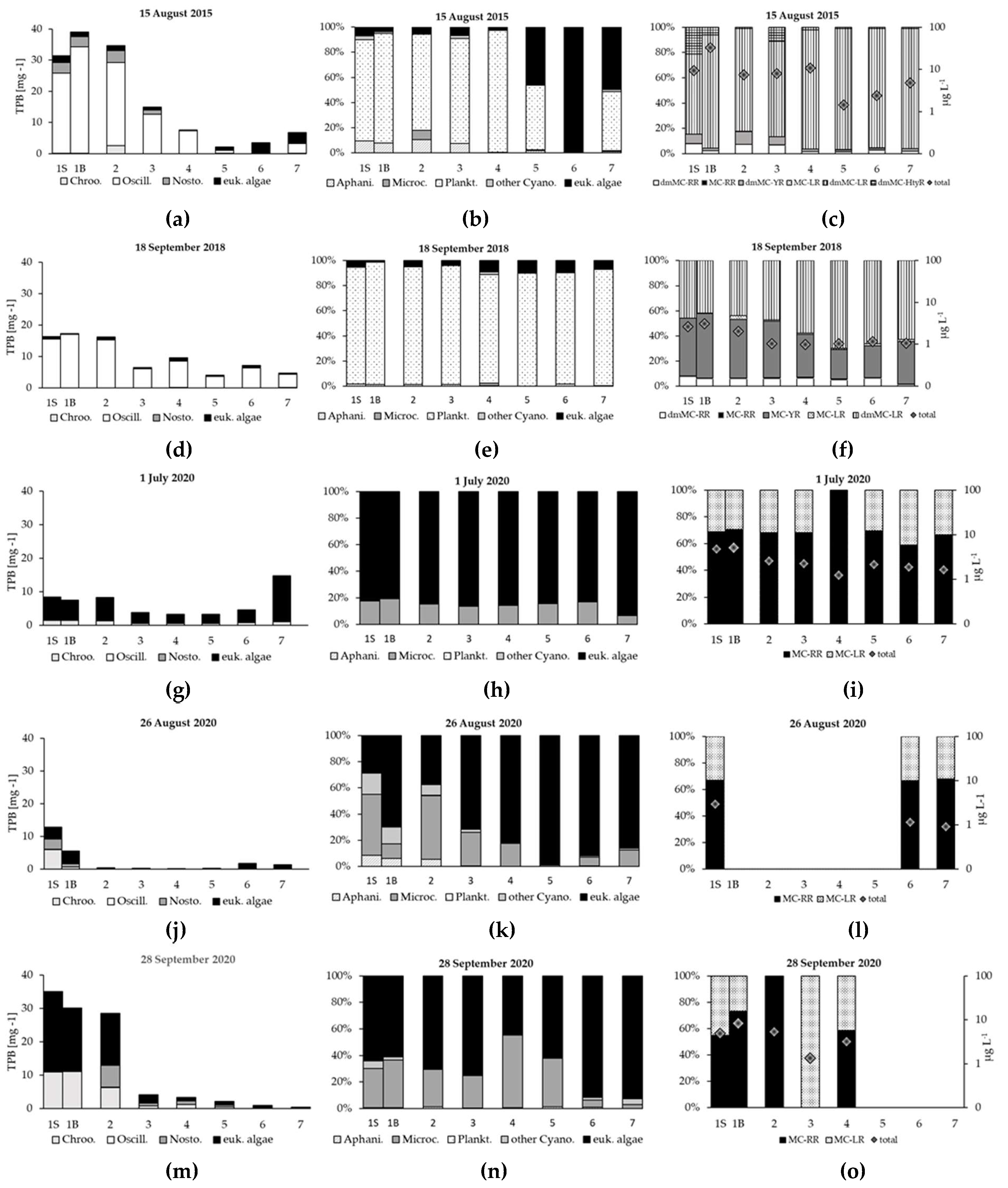

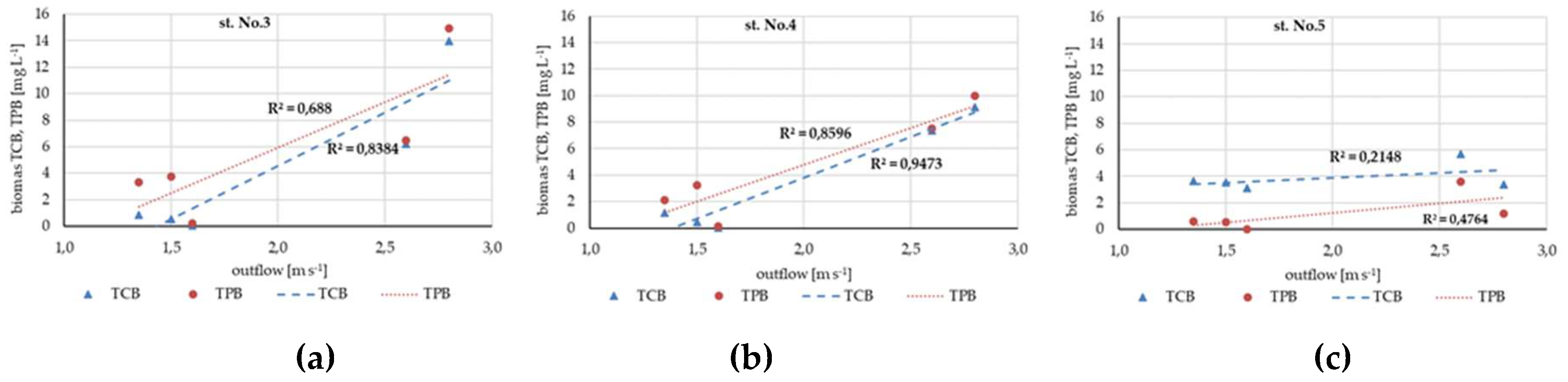

3.3. Phytoplankton Structure

3.4. Secondary Metabolites of Cyanobacteria

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Neil, J.M.; Davis, T.W.; Burford, M.A.; Gobler, C.J. The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: The potential roles of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobos, J.; Błaszczyk, A.; Hohlfeld, N.; Toruńska-Sitarz, A.; Krakowiak, A.; Hebel, A.; Sutryk, K.; Grabowska, M.; Toporowska, M.; Kokociński, M.; et al. Cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in Polish freshwater bodies. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2013, 42, 358–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overlingė, D.; Kataržytė, M.; Vaičiūtė, D.; Gyraitė, G.; Gečaitė, I.; Jonikaitė, E.; Mazur-Marzec, H. Are there concerns regarding cHAB in coastal bathing waters affected by freshwater-brackish continuum? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 159, 111500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, J.M.; Lopes, F.A.C.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Vidal, L.M.; Leomil, L.; Melo, F.; de Azevedo, G.S.; Oliveira, R.M.S.; Medeiros, A.J.; Melo, A.S.O.; et al. Occurrence of Harmful Cyanobacteria in Drinking Water from a Severely Drought-Impacted Semi-arid Region. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewska, W.; Piontek, M.; Łuszczyńska, K. The Occurrence of Potential Harmful Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxins in the Obrzyca River (Poland), a Source of Drinking Water. Toxins 2020, 12, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorus, I.; Welker, M. Toxic cyanobacteria in water. A guide to their public health consequences, monitoring and management. 2nd ed.; CRC Press, Boca Raton (FL), on behalf of the World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; 1–859.

- Rangel, L.M.; Soares, M.C.S.; Paiva, R.; Silva, L.H.S. Morphology-based functional groups as effective indicators of phytoplankton dynamics in a tropical cyanobacteria-dominated transitional river–reservoir system. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 64, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegłowska, M.; Kwiecień, P.; Szubert, K.; Brzuzan, P.; Florczyk, M.; Edwards, C.; Kosakowska, A.; Mazur-Marzec, H. Biological activity and stability of aeruginosamides from cyanobacteria. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.R.; Pinto, E.; Torres, M.A.; Dörr, F.; Mazur-Marzec, H.; Szubert, K.; Tartaglione, L.; Dell'Aversano, C.; Miles, C.O.; Beach, D.G.; et al. CyanoMetDB, a comprehensive public database of secondary metabolites from cyanobacteria. Water Res. 2021, 196, 117017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzouki, E.; Lürling, M.; Fastner, J.; De Senerpont Domis, L.; Wilk-Woźniak, E.; Koreivienė, J.; Seelen, L.; Teurlincx, S.; Verstijnen, Y.; Krztoń, W.; et al. Temperature Effects Explain Continental Scale Distribution of Cyanobacterial Toxins. Toxins 2018, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidenbach, J.D.; French, B.W.; Gordon, T.T.; Kleinhenz, A.L.; Khalaf, F.K.; Willey, J.C.; Hammersley, J.R.; Wooten, R.M.; Crawford, E.L.; Modyanov, N.N.; Malhotra, D.; Teeguarden, J.G.; Haller, S.T.; Kennedy, D.J. Microcystin-LR aerosol induces inflammatory responses in healthy human primary airway epithelium. Environ. Int. 2022, 169, 107531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roegner, A.F.; Corman, J.R.; Sitoki, L.M.; Kwena, Z.A.; Ogari, Z.; Miruka, J.B.; Xiong, A.; Weirich, C.; Aura, C.M.; Miller, T.R. Impacts of algal blooms and microcystins in fish on small-scale fishers in Winam Gulf, Lake Victoria: implications for health and livelihood. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaïcha, N.; Miles, C.O.; Beach, D.G.; Labidi, Z.; Djabri, A.; Benayache, N.Y.; Nguyen-Quang, T. Structural Diversity, Characterization and Toxicology of Microcystins. Toxins 2019, 11, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, D.; Xie, P.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Z. Simultaneous determination of microcystin contaminations in various vertebrates (fish, turtle, duck and water bird) from a large eutrophic Chinese lake, Lake Taihu, with toxic Microcystis blooms. Sci. Total. Environ. 2009, 407, 3317–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlik-Skowrońska, B.; Toporowska, M.; Mazur-Marzec, H. Effects of secondary metabolites produced by different cyanobacterial populations on the freshwater zooplankters Brachionus calyciflorus and Daphnia pulex. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 11793–11804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, Z.; Dang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, J. Promotion effect on liver tumor progression of microcystin-LR at environmentally relevant levels in female krasV12 transgenic zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 252, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmayer, R.; Deng, L.; Entfellner, E. Role of toxic and bioactive secondary metabolites in colonization and bloom formation by filamentous cyanobacteria Planktothrix. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.M.L. Cyanobacterial peptides beyond microcystins–A review on co-occurrence, toxicity, and challenges for risk assessment. Water Res. 2019, 151, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varriale, F.; Tartaglione, L.; Zervou, S.-K.; Miles, C.O.; Mazur-Marzec, H.; Triantis, T.M.; Kaloudis, T.; Hiskia, A.; Dell’aversano, C. Untargeted and targeted LC-MS and data processing workflow for the comprehensive analysis of oligopeptides from cyanobacteria. Chemosphere 2022, 311, 137012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overlingė, D.; Toruńska-Sitarz, A.; Cegłowska, M.; Błaszczyk, A.; Szubert, K.; Pilkaitytė, R.; Mazur-Marzec, H. Phytoplankton of the Curonian Lagoon as a New Interesting Source for Bioactive Natural Products. Special Impact on Cyanobacterial Metabolites. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duy, S.V.; Munoz, G.; Sauvé, S. Phytotoxic effects of microcystins, anatoxin-a and cylindrospermopsin to aquatic plants: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 810, 152104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bownik, A.; Pawlik-Skowrońska, B.; Wlodkowic, D.; Mieczan, T. Interactive effects of cyanobacterial metabolites aeruginosin-98B, anabaenopeptin-B and cylindrospermopsin on physiological parameters and novel in vivo fluorescent indicators in Chironomus aprilinus larvae. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 914, 169846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yéprémian, C.; Gugger, M.F.; Briand, E.; Catherine, A.; Berger, C.; Quiblier, C.; Bernard, C. Microcystin ecotypes in a perennial Planktothrix agardhii bloom. Water Res. 2007, 41, 4446–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, P.S. Ecological effects of perturbation by drought in flowing waters. Freshw. Biol. 2003, 48, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havens, K.; Paerl, H.; Phlips, E.; Zhu, M.; Beaver, J.; Srifa, A. Extreme Weather Events and Climate Variability Provide a Lens to How Shallow Lakes May Respond to Climate Change. Water 2016, 8, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuting, W.; Hongshan, Y.; Jian, S.; Jiuguo, Z. The effect of drought on the communities of plankton and benthos in reservoirs in spring. J. Ocean Univ. Qingdao 2002, 32, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, M.; Zwolsman, G. Impact of summer droughts on the water quality of the Meuse River. J. Hydrol. 2008, 353, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, C.; Álvarez-Cobelas, M.; Benavent-Corai, J.; Barón-Rodríguez, M.M.; Rodrigo, M.A. Trade-offs in plankton species richness arising from drought: insights from long-term data of a National Park wetland (central Spain). Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 2453–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, J.R.; Jensen, D.E.; Casamatta, D.A.; Tausz, C.E.; Scotese, K.C.; Buccier, K.M.; Teacher, C.E.; Rosati, T.C.; Minerovic, A.D.; Renicker, T.R. Response of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities in six reservoirs of the middle Missouri River (USA) to drought conditions and a major flood event. Hydrobiologia 2012, 705, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornés, E.; Pérez, M.C.; Durán, C.; Sabater, C. Reservoirs override seasonal variability of phytoplankton communities in a regulated Mediterranean river Sci. Total Environ 2014, 475, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.A.; Borges, H.; Puddick, J.; Biessy, L.; Atalah, J.; Hawes, I.; Dietrich, D.R.; Hamilton, D.P. Contrasting cyanobacterial communities and microcystin concentrations in summers with extreme weather events: insights into potential effects of climate change. Hydrobiologia 2016, 785, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo, S.; Soria, J.; Fernández, F.; Ouahid, Y.; Barón-Solá. Water residence time and the dynamics of toxic cyanobacteria. Freshw. Biol. 2012, 58, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, P.; Grabowska, M.; Jekatierynczuk-Rudczyk, E. Influence of changeable hydro-meteorological conditions on dissolved organic carbon and bacterioplankton abundance in a hypertrophic reservoir and downstream river. Ecohydrology 2015, 9, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowski, P.; Grygoruk, M. Long-Term Downstream Effects of a Dam on a Lowland River Flow Regime: Case Study of the Upper Narew. Water 2017, 9, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhu, G.; Paerl, H.W.; Zhu, M.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B. Extreme weather event may induce Microcystis blooms in the Qiantang River, Southeast China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 22273–22284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K.; Cho, E.-A.; Kim, H.-W.; Joo, G.-J. Microcystis bloom formation in the lower Nakdong River, South Korea: importance of hydrodynamics and nutrient loading. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1999, 50, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Li, C.; Peng, L.; Han, B.-P. Competition between toxic and non-toxic Microcystis aeruginosa and its ecological implication. Ecotoxicology 2015, 24, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzyńska, A.; Rosińska, J.; Pełechata, A.; Toporowska, M.; Napiórkowska-Krzebietke, A.; Kozak, A.; Messyasz, B.; Pęczuła, W. Kokociński, M.; Szeląg-Wasielewska, E.; Grabowska, M.; Mądrecka, B.; Niedźwiecki, M.; Alcaraz-Parraga, P.; Pełechaty, M.; Karpowicz, M.; Pawlik-Skowrońska, B. Environmental factors driving the occurrence of the invasive cyanobacterium Sphaerospermopsis aphanizomenoides (Nostocales) in temperate lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paerl, H.W.; Havens, K.E.; Hall, N.S.; Otten, T.G.; Zhu, M.; Xu, H.; Zhu, G.; Qin, B. Mitigating a global expansion of toxic cyanobacterial blooms: confounding effects and challenges posed by climate change. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2020, 71, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górniak, A.; Zieliński, P.; Jekatierynczuk-Rudczyk, E.; Grabowska, M.; Suchowolec, T. The role of dissolved organic carbon in the shallow lowland reservoir ecosystem. Acta Hydroch. Hydrob. 2002, 30, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, S.-H.; Oh, H.-M.; You, K.-A. Dynamic variation of toxic and non-toxic Microcystis proportion in the eutrophic Daechung Reservoir in Korea. J. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidelev, S.; Zubishina, A.; Chernova, E. Distribution of microcystin-producing genes in Microcystis colonies from some Russian freshwaters: Is there any correlation with morphospecies and colony size? Toxicon 2020, 184, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krztoń, W.; Walusiak, E.; Wilk-Woźniak, E. Possible consequences of climate change on global water resources stored in dam reservoirs. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 830, 154646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowska, M.; Mazur-Marzec, H. The influence of hydrological conditions on phytoplankton community structure and cyanopeptide concentration in dammed lowland river. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Meteorology and Water Management National Research Institute. Available online: https://hydro.imgw.pl/#/station/hydro/152230120?

- TuTiempo.net. Climate Bialystok. http://en.tutiempo.net/climate/ws-122950.html. (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Institute of Meteorology and Water Management National Research Institute? Available online: https://dane.imgw.pl/data/dane_pomiarowo_obserwacyjne/dane_hydrologiczne/miesieczne/?C=M;O=A (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Grabowska, M.; Mazur-Marzec, H. Vertical distribution of cyanobacteria biomass and cyanotoxin production in polymictic Siemianówka Dam Reservoir. Arch. Pol. Fisheries 2014, 22, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, C.; Neal, M.; Wickham, H. Phosphate measurement in natural waters: two examples of analytical problems associated with silica interference using phosphomolybdic acid methodologies. Sci. Total. Environ. 2000, 251–252, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, M.; Kobos, J.; Toruńska-Sitarz, A.; Mazur-Marzec, H. Non-ribosomal peptides produced by Planktothrix agardhii from Siemianówka Dam Reservoir SDR (northeast Poland) Arch. Microbiol. 2014, 196, 697–707. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, M. Cyanoprokaryota blooms in the polyhumic Siemianówka dam reservoir in 1992-2003. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2005, 34, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, M. Phytoplankton of Siemianówka dam reservoir. In Ecosystem of Siemianówka reservoir in 1990-2004 and its restoration, Ed. Górniak, A., Department of Hydrobiology University of Białystok, Białystok, Poland, 2006, 83–92 (in Polish).

- Grabowska, M. The role of a eutrophic lowland reservoir in shaping the composition of river phytoplankton. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2012, 12, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczak, T.; Tarczyńska, M.; Karlsson, K.; Meriluoto, J. Characterization and Diversity of Cyano- bacterial Hepatotoxins (Microcystins) in Blooms from Polish Freshwaters Identified by Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionisation Mass Spectrometry. Chromatographia 2004, 59, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, M.; Pawlik-Skowrońska, B. Replacement of chroococcales and nostocales by oscillatoriales caused a significant increase in microcystin concentrations in a dam reservoir. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2008, 37, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, M.; Mazur-Marzec, H. The effect of cyanobacterial blooms in the Siemianówka Dam Reservoir on the phytoplankton structure in the Narew River. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2011, 40, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W.; Barnard, M.A. Mitigating the global expansion of harmful cyanobacterial blooms: Moving targets in a human- and climatically-altered world. Harmful Algae 2020, 96, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, L.P.; Petsch, D.K.; Mantovano, T.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Agostinho, A.A.; Bonecker, C.C. A prolonged drought period reduced temporal β diversity of zooplankton, phytoplankton, and fish metacommunities in a Neotropical floodplain. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 1073–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, R.; Paul, M.J.; Stamp, J.; Hamilton, A.; Johnson, T. A Review of water quality responses to air temperature and precipitation changes 2: Nutrients, algal blooms, sediment, pathogens. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2018, 55, 844–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosley, L.M. Drought impacts on the water quality of freshwater systems; review and integration. Earth-Science Rev. 2015, 140, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk-Woźniak, E.; Krztoń, W.; Budziak, M.; Walusiak, E.; Žutinič, P.; Udovič, M.G.; Koreivienė, J.; Karosienė, J.; Kasperovičienė, J.; Kobos, J.; et al. Harmful blooms across a longitudinal gradient in central Europe during heatwave: Cyanobacteria biomass, cyanotoxins, and nutrients. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadova-Ratkus, K.; Mazur-Marzec, H.; Karosienė, J.; Kasperovičienė, J.; Paškauskas, R.; Vitonytė, I.; Koreivienė, J. Interplay of Nutrients, Temperature, and Competition of Native and Alien Cyanobacteria Species Growth and Cyanotoxin Production in Temperate Lakes. Toxins 2021, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, J.D.; Davis, T.W.; Smith, D.J.; Baer, M.M.; Dick, G.J. Interactions between nitrogen form, loading rate, and light intensity on Microcystis and Planktothrix growth and microcystin production. Harmful Algae 2018, 73, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöhnk, K.D.; Huisman, J.; Sharples, J.; Sommeijer, B.; Visser, P.M.; Stroom, J.M. Summer heatwaves promote blooms of harmful cyanobacteria. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2007, 14, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W.; Paul, V.J. Climate change: Links to global expansion of harmful cyanobacteria. Water Res. 2012, 46, 1349–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, J.; Codd, G.A.; Paerl, H.W.; Ibelings, B.W.; Verspagen, J.M.H.; Visser, P.M. Cyanobacterial blooms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gągała, I.; Izydorczyk, K.; Skowron, A.; Kamecka-Plaskota, D.; Stefaniak, K.; Kokociński, M.; Mankiewicz-Boczek, J. Appearance of toxigenic cyanobacteria in two Polish lakes dominated by Microcystis aeruginosa and Planktothrix agardhii and environmental factors influence. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2010, 10, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, X.; Peijnenburg, W.; Zhang, M.; Sun, L.; Zhai, Y.; Yu, Q.; Wu, J.; Lu, T.; Qian, H. Alteration of dominant cyanobacteria in different bloom periods caused by abiotic factors and species interactions. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 99, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monchamp, M.-E.; Pick, F.R.; Beisner, B.E.; Maranger, R. Nitrogen Forms Influence Microcystin Concentration and Composition via Changes in Cyanobacterial Community Structure. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e85573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Schmalz, B.; Fohrer, N. Distribution of phytoplankton in a German lowland river in relation to environmental factors. J. Plankton Res. 2010, 33, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harke, M.J.; Steffen, M.M.; Gobler, C.J.; Otten, T.G.; Wilhelm, S.W.; Wood, S.A.; Paerl, H.W. A review of the global ecology, genomics, and biogeography of the toxic cyanobacterium, Microcystis spp. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fang, H.; Lu, H.; Wu, X.; Yu, G.; Nakano, S.-I.; Li, R. Relationship between morphospecies and microcystin-producing genotypes of Microcystis species in Chinese freshwaters. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2021, 39, 1926–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suominen, S.; Brauer, V.S.; Rantala-Ylinen, A.; Sivonen, K.; Hiltunen, T. Competition between a toxic and a non-toxic Microcystis strain under constant and pulsed nitrogen and phosphorus supply. Aquat. Ecol. 2016, 51, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.S.; Recknagel, F.; Cao, H.; Park, H.-D. Elucidation and short-term forecasting of microcystin concentrations in Lake Suwa (Japan) by means of artificial neural networks and evolutionary algorithms. Water Res. 2007, 41, 2247–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gągała, I.; Izydorczyk, K.; Jurczak, T.; Pawełczyk, J.; Dziadek, J.; Wojtal-Frankiewicz, A.; Jóźwik, A.; Jaskulska, A.; Mankiewicz-Boczek, J. Role of Environmental Factors and Toxic Genotypes in the Regulation of Microcystins-Producing Cyanobacterial Blooms. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 67, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Zhang, C.; Struewing, I.; Li, X.; Allen, J.; Lu, J. Cyanotoxin-encoding genes as powerful predictors of cyanotoxin production during harmful cyanobacterial blooms in an inland freshwater lake: Evaluating a novel early-warning system. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 830, 154568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | m/z | Class | Name of oligopeptide | 2015 | 2018 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1057 | MC | MC-Prhcyst(O)R | dam | 1S | ||

| river | |||||||

| 2 | 1045 | MC | [Asp3]MC-HtyR | dam | 1S, 1B | ||

| river | 2-7 | ||||||

| 3 | 1038 | MC | MC-RR | dam | 1S, 1B | 1S, 1B | 1S, 1B |

| river | 2-7 | 2-7 | 2-7 | ||||

| 4 | 1031 | MC | [Asp3]MC-YR | dam | 1S, 1B | ||

| river | 2-7 | ||||||

| 5 | 1024 | MC | [Asp3]MC-RR | dam | 1S, 1B | 1S, 1B | |

| river | 2-7 | 2-7 | |||||

| 6 | 995 | MC | MC-LR | dam | 1S, 1B | 1S, 1B | |

| river | 2, 5-6 | 2-7 | 2-7 | ||||

| 7 | 981 | MC | [Asp3]MC-LR | dam | 1S, 1B | 1S, 1B | 1S, 1B |

| river | 2-7 | 2-7 | |||||

| 8 | 1045 | MC | MC-YR | dam | 1S, 1B | ||

| river | 2-7 | ||||||

| 9 | 1015 | CP | X-X-[Thr-Arg-Ahp-Phe-MeTyr-Val] | dam | 1S | ||

| river | 4 | ||||||

| 10 | 973 | CP | Hex-Gln-[Thr-Lys-Ahp-Leu-MeTyr- | dam | 1S | ||

| river | |||||||

| 11 | 917 | CP | X-X-[Thr-X-Ahp-Phe-MeTyr-X] | dam | 1S | ||

| river | 4 | ||||||

| 12 | 905 | CP | X-X-[Thr-X-Ahp-Phe-MeTyr-X] | dam | 1S, 1B | ||

| river | |||||||

| 13 | 887 | CP | X-X-[Thr-X-Ahp-Phe-MeTyr-Ile] | dam | 1S, 1B | ||

| river | 3-7 | ||||||

| 14 | 858 | CP | [Phe-MeAla-HTyr-Ile-Lys]CO-Tyr | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-5, 7 | 2, 4-7 | |||||

| 15 | 916 | AP | [Ile-MeHty-HTyr-Val-Lys]CO-Tyr | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-4, 6- | 2, 4-5, 7 | |||||

| 16 | 910 | AP G | [Tyr-MeLeu-HTyr-Ile-Lys]CO-Arg | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-4, 6-7 | 2, 5-7 | |||||

| 17 | 851 | AP F | [Phe-MeAla-HTyr-Ile-Lys]CO-Arg | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-4, 6-7 | 2, 4-7 | |||||

| 18 | 844 | AP A | [Phe-MeAla-HTyr-Val-Lys]CO-Tyr | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-7 | 2, 4-7 | |||||

| 19 | 837 | AP B | [Phe-MeAla-HTyr-Val-Lys]CO-Arg | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-7 | 2, 4-7 | |||||

| 20 | 801 | PL | [Leu-Val-Met-Phe-Arg-154] | dam | 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-4 | 5-6 | |||||

| 21 | 765 | AER | Cl-Hpla-Leu-(Xyl)Choi-Aeap | dam | 1S, 1B | ||

| river | 2-4 | ||||||

| 22 | 749 | Cl-AER | Cl-Pla-Leu-(Xyl)Choi-Aeap | dam | 1S, 1B | ||

| river | 2-4 | ||||||

| 23 | 715 | AER | Pla-Leu-(Xyl)Choi-Aeap | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-4 | 2, 4-7 | |||||

| 24 | 707 | AER | Hpla-Leu-(Xyl)Choi-Agm | dam | 1S, 1B | ||

| river | 2-3 | ||||||

| 25 | 691 | AER | Pla-Leu-(Xyl)Choi-Agm | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-4 | 2, 4-7 | |||||

| 26 | 653 | AER | Hpla-Tyr-Choi-Argal | dam | |||

| river | 4-5 | ||||||

| 27 | 643 | AER | Cl2-Hpla-Tyr-Choi-Agm | dam | 1S, 1B | ||

| river | |||||||

| 28 | 637 | AER | Cl-Hpla-Leu-Choi-Argal | dam | 1S | 1B | |

| river | 2-4, 7 | 2, 6-7 | 3, 5 | ||||

| 29 | 625 | MG | ClAhda-Tyr-MeLeu-Pro | dam | 1B | ||

| river | 2, 4-7 | ||||||

| 30 | 621 | AER | X-Leu-Choi-Agm | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-5, 7 | 2, 4-7 | |||||

| 31 | 609 | AER | Cl-Hpla-Leu-Choi-Agm | dam | 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-3 | 2, 4, 6-7 | |||||

| 32 | 587 | AER | X-Leu-Choi-Agm | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | |

| river | 2-4, 7 | 2, 5 - 7 | |||||

| 33 | 593 | MG | ClAhda-Tyr-MeLeu-Pro | dam | 1S | 1B | |

| river | 2, 4 - 7 | ||||||

| 34 | 561 | AERD | (Pren)2Ile-Val-Pro-methiazole | dam | 1S, 1B | 1B | 1S, 1B |

| river | 2-7 | 2-6 |

| Species/order | season | SDR | NR | SDR&NR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. agardhii | 2015 &2018 | 0.953 | 0.478 | 0.725 |

| p=0.047 | p=0.116 | p=0.001 | ||

| Oscillatoriales | 2015 & 2018 | 0.947 | 0.482 | 0.725 |

| p=0.054 | p=0.113 | p=0.001 | ||

| Chroococcales | 2015 & 2018 | 0.132 | 0.409 | 0.070 |

| p=0.868 | p=0.186 | p=0.796 | ||

| Nostocales | 2015 & 2018 | 0.724 | 0.591 | 0.693 |

| p=0.276 | p=0.043 | p=0.003 | ||

| Cyanobacteria | 2015 & 2018 | 0.921 | 0.501 | 0.717 |

| p=0.079 | p=0.097 | p=0.002 | ||

| P. agardhii | 2020 | n.d. | 0.046 | -0.075 |

| p=0.860 | p=0.708 | |||

| Oscillatoriales | 2020 | 0.252 | 0.161 | 0.539 |

| p=0.513 | p=0.524 | p=0.004 | ||

| Chroococcales | 2020 | 0.631 | 0.751 | 0.779 |

| p=0.069 | p=0.000 | p=0.000 | ||

| Nostocales | 2020 | 0.378 | 0.663 | 0.953 |

| p=0.315 | p=0.003 | p=0.047 | ||

| Cyanobacteria | 2020 | 0.691 | 0.839 | 0.779 |

| p=0.039 | p=0.000 | p=0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).