Submitted:

16 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

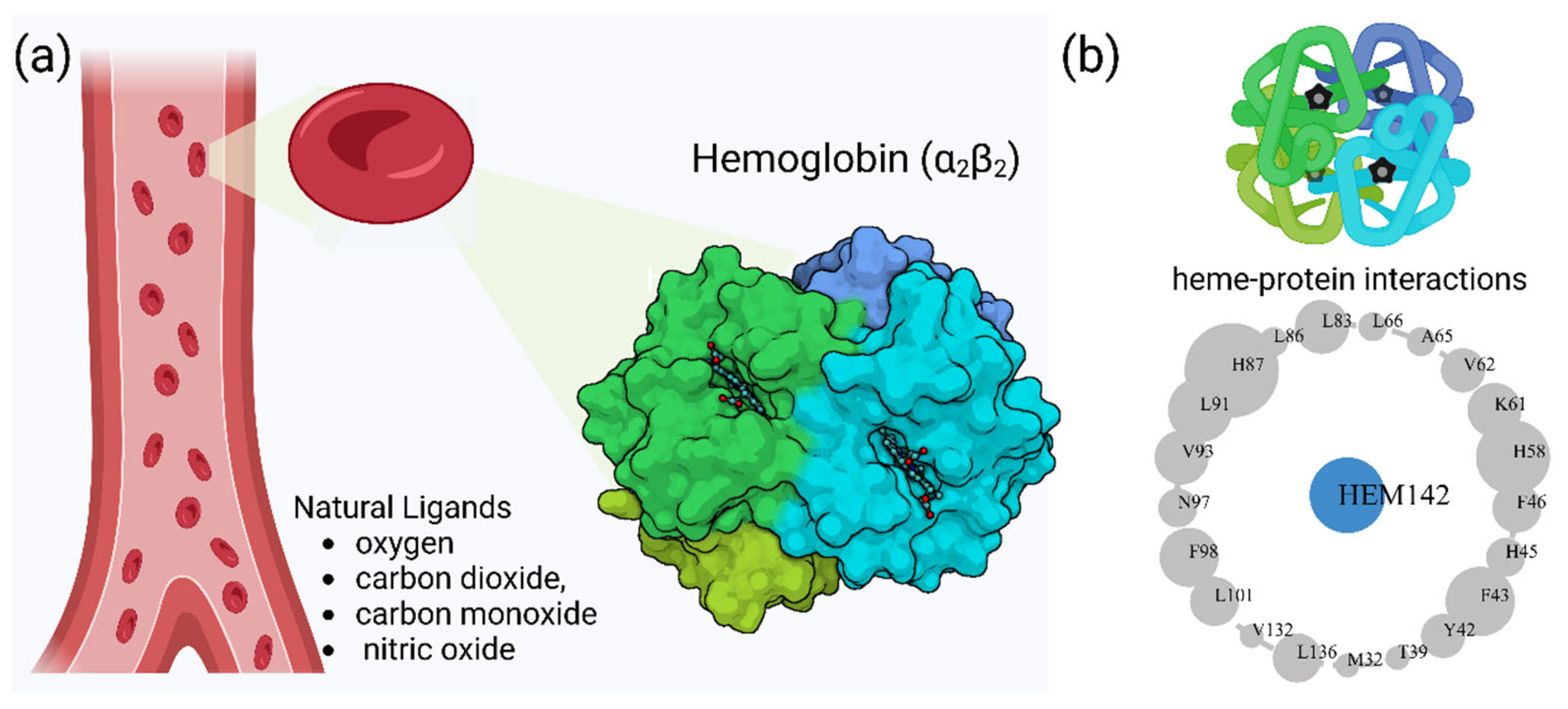

2. Hemoglobin Function and Clinical Variants

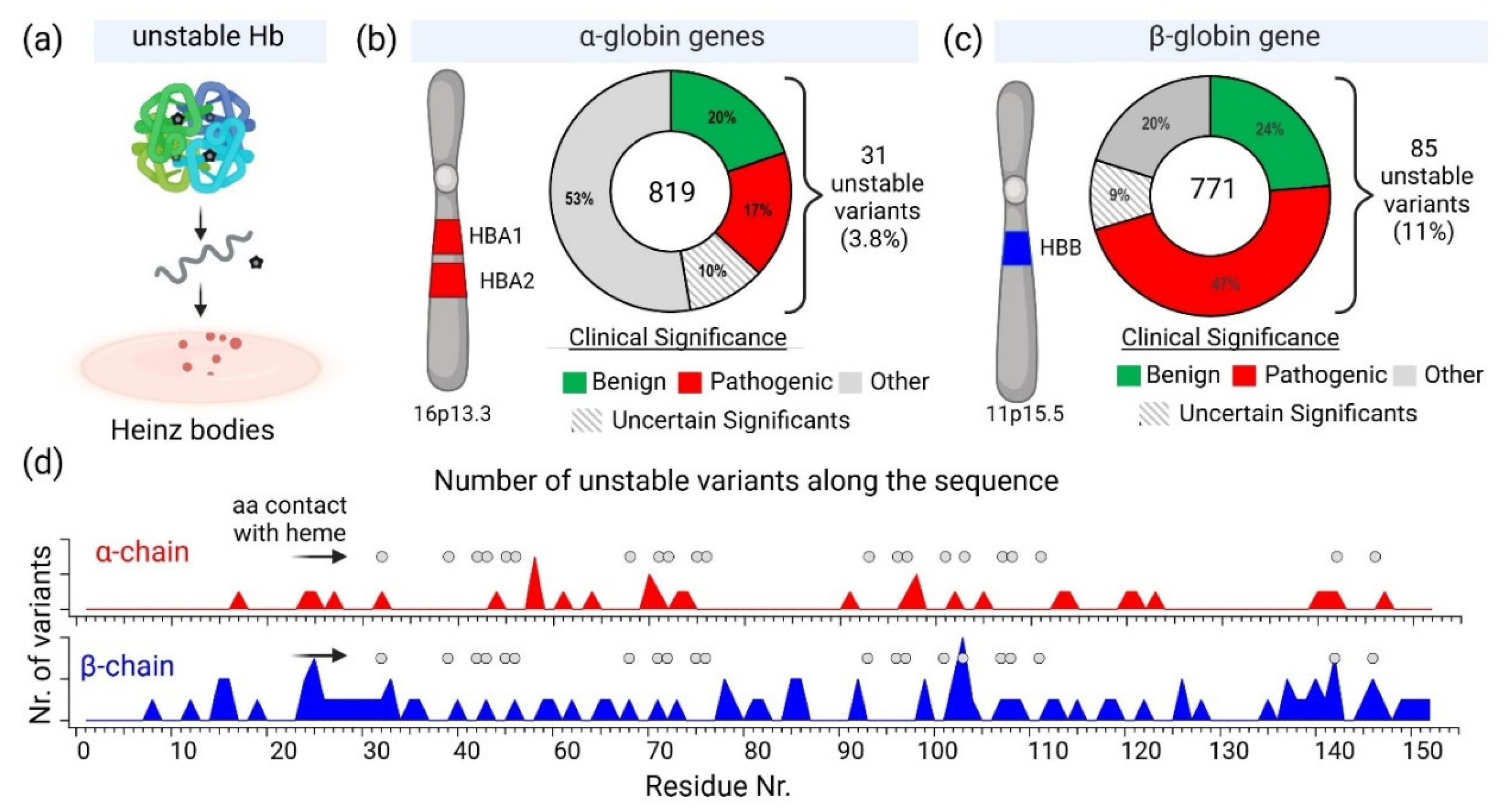

2.1. Diversity of Genetic Variants of Hemoglobin

2.2. Hemoglobin Instability and Heinz Bodies

2.3. Pharmacological Approaches to Hemoglobin Stabilization and Oxidative Stress in Hemolytic Disorders

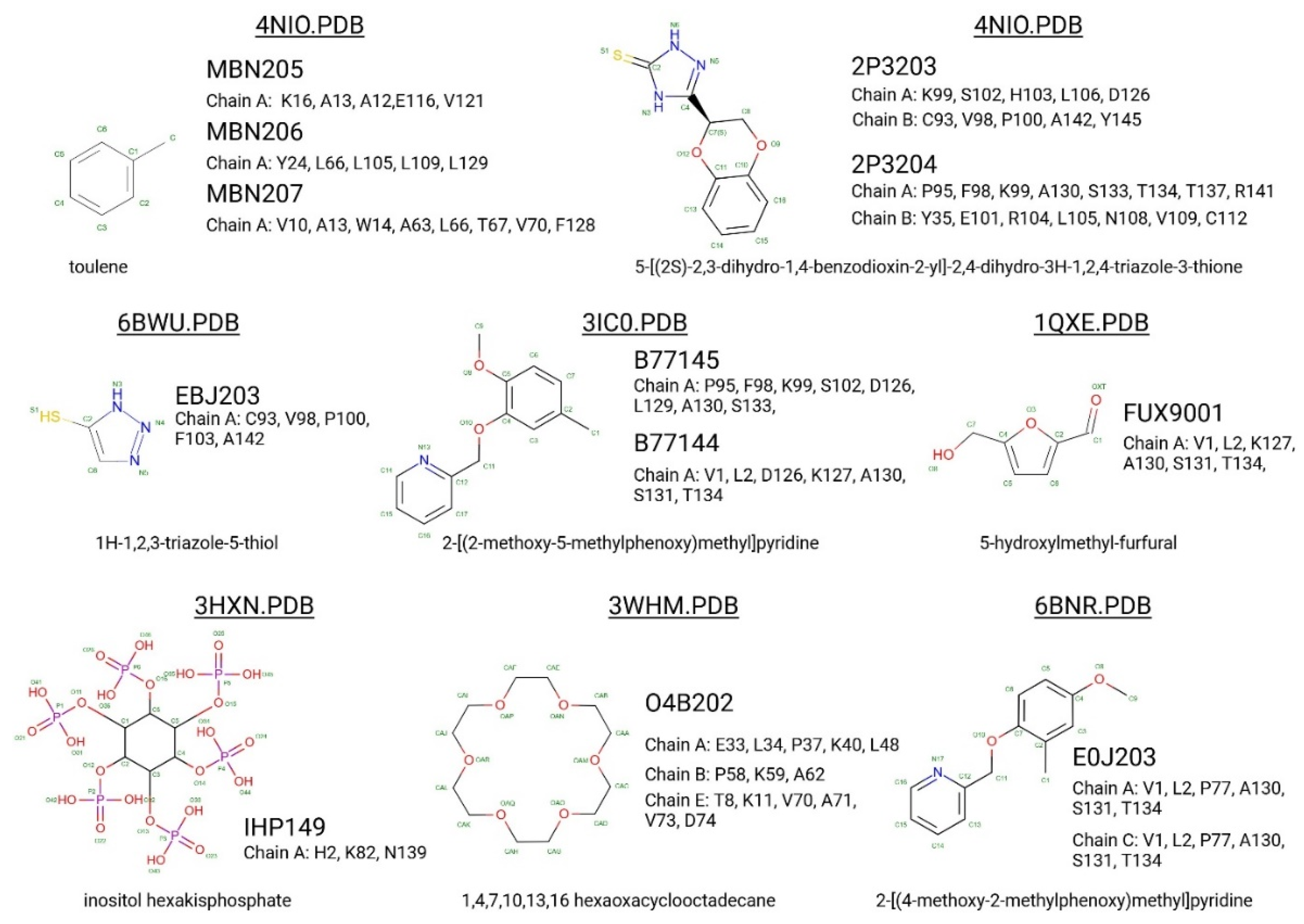

2.4. Small-Molecule Binders to Hemoglobin

3. Search for Potentially New Hb Stabilisers: Hemoglobin Binding Proteins

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| SNO | S-nitrosohemoglobin |

| BPG | Bisphosphoglycerate |

| HbF | Fetal Hemoglobin |

| HbA | Adult Hemoglobin |

| HbC | Hemoglobin C |

| HbD | Hemoglobin D |

| HbE | Hemoglobin E |

| Hb CS | Hb Constant Spring |

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| SCD | Sickle cell disease |

| RBC | Red Blood Cell |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| AHSP | α-Hemoglobin Stabilizing Protein |

| G6PD | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| ALAS-1 | aminolevulinic acid synthase |

| S1P | sphingosine 1-phosphate |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

References

- Perutz, M.F. Stereochemical mechanism of oxygen transport by haemoglobin. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1980, 208, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellelli, A. Hemoglobin and cooperativity: Experiments and theories. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2010, 11, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, A.F. The Bohr effect. Annu Rev Physiol 1988, 50, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyuma, I.; Shimizu, K. Different response to organic phosphates of human fetal and adult hemo globins. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 129, 404–405. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safo, M.K.; Ahmed, M.H.; Ghatge, M.S.; Boyiri, T. Hemoglobin-ligand binding: understanding Hb function and allostery on atomic level. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2011, 1814, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.H.; Ghatge, M.S.; Safo, M.K. Hemoglobin: Structure, Function and Allostery. Subcell Biochem 2020, 94, 345–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randad, R.S.; Mahran, M.A.; Mehanna, A.S.; Abraham, D.J. Allosteric modifiers of hemoglobin. 1. Design, synthesis, testing, and structure-allosteric activity relationship of novel hemoglobin oxygen affinity decreasing agents. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 34, 752–757. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronda, L.; Bruno, S.; Abbruzzetti, S.; Viappiani, C.; Bettati, S. Ligand reactivity and allosteric regulation of hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 1784, 1365–1377. [CrossRef]

- Ciaccio, C.; Coletta, A.; De Sanctis, G.; Marini, S.; Coletta, M. Cooperativity and allostery in haemoglobin function. IUBMB Life 60, 112–123. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maillett, D.H.; Simplaceanu, V.; Shen, T.-J.; Ho, N.T.; Olson, J.S.; Ho, C. Interfacial and Distal-Heme Pocket Mutations Exhibit Additive Effects on the Structure and Function of Hemoglobin. Biochemistry 47, 10551-10563. [CrossRef]

- Brunori, M.; Miele, A.E. Modulation of Allosteric Control and Evolution of Hemoglobin. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storz, J.F. Hemoglobin structure and allosteric mechanism. In Hemoglobin, Oxford University Press: 2018, pp. 58-93. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.K.; Roughton, F.J. The chemical relationships and physiological importance of carbamino compounds of CO(2) with haemoglobin. J Physiol 1934, 83, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, N.; Kavanaugh, J.; Rogers, P.; Arnone, A. Crystallographic analysis of the interaction of nitric oxide with quat ernary-T human hemoglobin. Biochemistry . [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.W.; Stamler, J.S.; Piantadosi, C.A. Hemoglobin, nitric oxide and molecular mechanisms of hypoxic vasodilat ion. Trends in Molecular Medicine 15, 452-460. [CrossRef]

- Hamasaki, N.; Rose, Z.B. The binding of phosphorylated red cell metabolites to human hemoglobin A. The Journal of biological chemistry 1974, 249, 7896–7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garby, L.; De Verdier, C.H. Affinity of human hemoglobin A to 2,3--diphosphoglycerate. Effect of hemoglobin concentration and of pH. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1971, 27, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beek, G.M.; Bruin, S.H.D. The pH Dependence of the Binding of d-Glycerate 2,3-Bisphosphate to De oxyhemoglobin and Oxyhemoglobin. [CrossRef]

- Isaacks, R.E. Can Metabolites Contribute in Regulating Blood Oxygen Affinity? In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Springer US: 1988; pp. 137-143. [CrossRef]

- Mulquiney, P.J.; Kuchel, P.W. Model of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate metabolism in the human erythrocyte based on detailed enzyme kinetic equations: equations and parameter refinement. Biochemical Journal 1999, 342, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayikci, M.; Venkatakrishnan, A.J.; Scott-Brown, J.; Ravarani, C.N.J.; Flock, T.; Babu, M.M. Visualization and analysis of non-covalent contacts using the Protein Contacts Atlas. Nature structural & molecular biology 2018, 25, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrayo López, F.J.; Figarola Centurion, I.; Perea Díaz, F.J.; Millán Pacheco, C.; Ibarra Cortés, B.; Torres Mendoza, B.M.; Flores-Jimenez, J.A.; Rizo-De La Torre, L.D.C. Structural Effect of Gγ and Aγ Globin Chains in Fetal Hemoglobin Tetramer. Blood 2023, 142, 2291–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiv k, S. Hematologic and Coagulation Disorders. Obstetric anesthesia: principles and practice 14.

- Manca, L.; Masala, B. Disorders of the synthesis of human fetal hemoglobin. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Rockwood, A.L.; Agarwal, A.M.; Anderson, L.C.; Weisbrod, C.R.; Hendrickson, C.L.; Marshall, A.G. Diagnosis of Hemoglobinopathy and beta-Thalassemia by 21 Tesla Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry and Tandem Mass Spectrometry of Hemoglobin from Blood. Clin Chem 2019, 65, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.S. Diagnosis of hemoglobinopathy and beta-thalassemia by 21-Tesla Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Ann Transl Med 2019, 7, S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrocini, G.C.; Zamaro, P.J.; Bonini-Domingos, C.R. What influences Hb fetal production in adulthood? Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter 2011, 33, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempe, J.M.; Craver, R.D. Laboratory Diagnosis of Structural Hemoglobinopathies and Thalassemias by Capillary Isoelectric Focusing. In Clinical Applications of Capillary Electrophoresis, Humana Press: pp. 81-98. [CrossRef]

- Little, R.R.; Roberts, W.L. A review of variant hemoglobins interfering with hemoglobin A1c measurement. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2009, 3, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thom, C.S.; Dickson, C.F.; Gell, D.A.; Weiss, M.J. Hemoglobin variants: biochemical properties and clinical correlates. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013, 3, a011858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, E.; Zou, W.B.; Genin, E.; Cooper, D.N.; Le Gac, G.; Fichou, Y.; Pu, N.; Rebours, V.; Ferec, C.; Liao, Z.; et al. Expanding ACMG variant classification guidelines into a general framework. Hum Genomics 2022, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carss, K.; Goldstein, D.; Aggarwal, V.; Petrovski, S. Variant Interpretation and Genomic Medicine. Handbook of Statistical Genomics 2019, 25. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-M.; Masson, E.; Zou, W.-B.; Liao, Z.; Génin, E.; Cooper, D.N.; Férec, C. Validation of the ACMG/AMP guidelines-based seven-category variant cla ssification system. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, N.; Cooper, A.; Dockery, A.; O'Byrne, J.J. Variant reclassification and clinical implications. J Med Genet 2024, 61, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabath, D.E. Molecular Diagnosis of Thalassemias and Hemoglobinopathies. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 148, 6-15. [CrossRef]

- Kountouris, P.; Stephanou, C.; Lederer, C.W.; Traeger-Synodinos, J.; Bento, C.; Harteveld, C.L.; Fylaktou, E.; Koopmann, T.T.; Halim-Fikri, H.; Michailidou, K.; et al. Adapting the ACMG/AMP variant classification framework: A perspective from the ClinGen Hemoglobinopathy Variant Curation Expert Panel. Hum Mutat 2022, 43, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.A.; Rao, S.K.; Morgan, R.H.; Vnencak-Jones, C.L.; Wiesner, G.L. The impact of variant classification on the clinical management of hereditary cancer syndromes. Genet Med 2019, 21, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Nora Syahirah, S.; Muhammad Nur Salam Bin, H.; Rajan, R. The Blood Blues: A Review on Methemoglobinemia. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics 2018, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylston, M.; Beer, D. Methemoglobinemia: a case study. Crit Care Nurse 2002, 22, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashurst, J.; Wasson, M. Methemoglobinemia: a systematic review of the pathophysiology, detecti on, and treatment. Delaware medical journal 2011, 83, 5. [Google Scholar]

- do Nascimento, T.S.; Pereira, R.O.; de Mello, H.L.; Costa, J. Methemoglobinemia: from diagnosis to treatment. Rev Bras Anestesiol 2008, 58, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iolascon, A.; Bianchi, P.; Andolfo, I.; Russo, R.; Barcellini, W.; Fermo, E.; Toldi, G.; Ghirardello, S.; Rees, D.; Van Wijk, R.; et al. Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of methemoglobinemia. Am J Hematol 2021, 96, 1666–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ash-Bernal, R.; Wise, R.; Wright, S.M. Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004, 83, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, N.; Scolnik, D.; McMurray, L.; Bryan, J. Acquired methemoglobinemia presenting to the pediatric emergency department: a clinical challenge. CJEM 2020, 22, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Biophysical Basis of Hb-S Polymerization in Red Blood Cell Sickling. bioRxiv 2019. [CrossRef]

- Karen, C. Sickle Cell Disease: A Genetic Disorder of Beta-Globin. Thalassemia and Other Hemolytic Anemias 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth, P.; Sparkenbaugh, E.M. Targeting the von Willebrand Factor-ADAMTS-13 axis in sickle cell disease. J Thromb Haemost 2023, 21, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nader, E.; Romana, M.; Connes, P. The Red Blood Cell-Inflammation Vicious Circle in Sickle Cell Disease. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley-Koch, A.; Yang, Q.; Olney, R.S. Sickle hemoglobin (HbS) allele and sickle cell disease: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol 2000, 151, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fatlawi, A.C.Y. A Review on Sickle Cells Disease. SJMR 2019, 03, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, M.C.; Orange, J. CRISPR/Cas9 β-globin Gene Targeting in Human Haematopoietic Stem Cells. Pediatrics 2017, 140, S226–S227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, S.; Gudmundsdottir, B.; Li, Q.; Haro-Mora, J.J.; Nassehi, T.; Drysdale, C.; Yapundich, M.; Gamer, J.; Seifuddin, F.; Tisdale, J.F.; et al. βT87Q-Globin Gene Therapy Reduces Sickle Hemoglobin Production, Allowi ng for Ex Vivo Anti-sickling Activity in Human Erythroid Cells. Molecular Therapy - Methods & Clinical Development 17, 912-921. [CrossRef]

- De Simone, G.; Quattrocchi, A.; Mancini, B.; di Masi, A.; Nervi, C.; Ascenzi, P. Thalassemias: from gene to therapy. Mol Aspects Med 2022, 84, 101028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angastiniotis, M.; Lobitz, S. Thalassemias: An Overview. Int J Neonatal Screen 2019, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weatherall, D.J. The thalassaemias. BMJ 1997, 314, 1675–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muncie, H.; James, C. Alpha and beta thalassemia. American Family Physician 2009, 80, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vernimmen, D. Globins, from Genes to Physiology and Diseases. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2018, 70, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksu, T.; Ş, Ü. Thalassemia. Trends in Pediatrics . 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Meri, M.; Hamid Al-Hakeem, A.; Saad Al-Abeadi, R. Overview on Thalassemia: A Review Article. Med.Sci.Jour.Adv.Res 2022, 3, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibek, K.; Jha, S.; Eiman, A.A.Z. Hemoglobin C Disease. Definitions 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Charache, S.; Conley, C.L.; Waugh, D.F.; Ugoretz, R.J.; Spurrell, J.R. Pathogenesis of hemolytic anemia in homozygous hemoglobin C disease. J Clin Invest 1967, 46, 1795–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, G.H.; Ranney, H.M.; Shaklai, N. Association of hemoglobin C with erythrocyte ghosts. J Clin Invest 1982, 70, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verra, F.; Simpore, J.; Warimwe, G.M.; Tetteh, K.K.; Howard, T.; Osier, F.H.; Bancone, G.; Avellino, P.; Blot, I.; Fegan, G.; et al. Haemoglobin C and S role in acquired immunity against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. PLoS One 2007, 2, e978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, K.L.; Randolph, T.R. Development of a Microscopic Method to Identify Hemoglobin C Conditions for Use in Developing Countries. Clin Lab Sci 2023, 32, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohiri, C.D.; Randolph, T.R. Development of an easy, inexpensive, and precise method to identify Hemoglobin C for use in underdeveloped countries. The FASEB Journal 2016, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Basak, J.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Coexistence of rare variant HbD Punjab [alpha2beta2(121(Glu-->Gln))] and alpha 3.7 kb deletion in a young boy of Hindu family in West Bengal, India. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2015, 20, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Seth, T.; Tyagi, S. Review of Clinical and Hematological Profile of Hemoglobin D Cases in a Single Centre. Journal of Marine Medical Society 2023, 25, S74–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Mishra, R.M.; Pandey, S.; Shah, V.; Saxena, R. Molecular characterization of hemoglobin D Punjab traits and clinical-hematological profile of the patients. Sao Paulo Med J 2012, 130, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italia, K.; Upadhye, D.; Dabke, P.; Kangane, H.; Colaco, S.; Sawant, P.; Nadkarni, A.; Gorakshakar, A.; Jain, D.; Italia, Y.; et al. Clinical and hematological presentation among Indian patients with common hemoglobin variants. Clin Chim Acta 2014, 431, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberoi, S.; Das, R.; Trehan, A.; Ahluwalia, J.; Bansal, D.; Malhotra, P.; Marwaha, R.K. HbSD-Punjab: clinical and hematological profile of a rare hemoglobinopathy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014, 36, e140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieder, R.F. Globin chain synthesis in HbD (Punjab)-beta-thalassemia. Blood 47, 113-120. [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, A.A.; Pivnik, A.V.; Kim, P.P.; Demidova, E.Y.; Surin, V.L.; Abdullaev, A.O.; Sudarikov, A.B.; Petrova, N.A.; Maryina, S.A. Coinheritance of HbD-Punjab/beta+-thalassemia (IVSI+5 G-C) in patient with Gilbert's syndrome. Ter Arkh 2018, 90, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, J.; Naka, I.; Patarapotikul, J.; Hananantachai, H.; Brittenham, G.; Looareesuwan, S.; Clark, A.G.; Tokunaga, K. Extended linkage disequilibrium surrounding the hemoglobin E variant due to malarial selection. Am J Hum Genet 2004, 74, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatz, G.; Sanguansermsri, T.; Sengchanh, S.; Horst, D.; Horst, J. The ‘Hot Spot’ of Hb E [β26(B8)Glu→Lys] in Southeast Asia: β-Globin An omalies in the Lao Theung Population of Southern Laos. Hemoglobin 28, 197-204. [CrossRef]

- Camille, J.R.; Malashkevich, V.; Tatiana, C.B.; Dantsker, D.; Qiu-Mao, C.; Juan, C.M.; Almo, S.; Friedman, J.; Hirsch, R.E. Structural and Functional Studies Indicating Altered Redox Properties of Hemoglobin E. Journal of Biological Chemistry . [CrossRef]

- Strader, M.B.; Kassa, T.; Meng, F.; Wood, F.B.; Hirsch, R.E.; Friedman, J.M.; Alayash, A.I. Oxidative instability of hemoglobin E (beta26 Glu-->Lys) is increased in the presence of free alpha subunits and reversed by alpha-hemoglobin stabilizing protein (AHSP): Relevance to HbE/beta-thalassemia. Redox Biol 2016, 8, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamsai, D.; Zaibak, F.; Vadolas, J.; Voullaire, L.; Fowler, K.J.; Gazeas, S.; Peters, H.; Fucharoen, S.; Williamson, R.; Ioannou, P.A. A humanized BAC transgenic/knockout mouse model for HbE/beta-thalassemia. Genomics 2006, 88, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naka, I.; Ohashi, J.; Nuchnoi, P.; Hananantachai, H.; Looareesuwan, S.; Tokunaga, K.; Patarapotikul, J. Lack of association of the HbE variant with protection from cerebral malaria in Thailand. Biochem Genet 2008, 46, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandopadhyay, M.; Jha, A.K.; Karmakar, S.; Sengupta, M.; Basu, K.; Das, M.; Mukherjee, S. HbE Variants: An Experience from Tertiary Care Centre of Eastern India. Annals of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine 2020, 7, A570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C. Oxidative denaturation in congenital hemolytic anemias: the unstable hemoglobins. Proceedings of Seminars in hematology; p. 41.

- Kidd, R.D.; Baker, H.M.; Mathews, A.J.; Brittain, T.; Baker, E.N. Oligomerization and ligand binding in a homotetrameric hemoglobin: Two high-resolution crystal structures of hemoglobin Bart's (γ4), a marker for α-thalassemia. Protein Science 10, 1739-1749. [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, E.W.; Risk, M.; Matustik, M.C. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction studies of methemogl obin Bart's. Journal of Biological Chemistry 256, 13128-13129. [CrossRef]

- Rugless, M.J.; Fisher, C.A.; Stephens, A.D.; Amos, R.J.; Mohammed, T.; Old, J.M. Hb Bart's in Cord Blood: An Accurate Indicator of α-Thalassemia. Hemoglobin 30, 57-62. [CrossRef]

- Papassotiriou, I.; Traeger-Synodinos, J.; Vlachou, C.; Karagiorga, M.; Metaxotou, A.; Kanavakis, E.; Stamoulakatou, A. Rapid and accurate quantitation of Hb Bart's and Hb H using weak cation exchange high performance liquid chromatography: correlation with the alpha-thalassemia genotype. Hemoglobin 1999, 23, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pootrakul, S.; Wasi, P.; Na-Nakorn, S. Haemoglobin Bart's hydrops foetalis in Thailand. Ann Hum Genet 1967, 30, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pembrey, M.E.; Weatherall, D.J.; Clegg, J.B.; Bunch, C.; Perrine, R.P. Haemoglobin Bart's in Saudi Arabia. British Journal of Haematology 29, 221-234. [CrossRef]

- Sasazuki, T.; Isomoto, A.; Nakajima, H. Circular dichroism and absorption spectra of haemoglobin Bart's. Journal of molecular biology 65, 365-369. [CrossRef]

- Folayan Esan, G.J. Haemoglobin Bart's in Newborn Nigerians. British Journal of Haematology 22, 73-86. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.; Charache, S.; Hathaway, P.J. The effect of hemoglobin F-Chesapeake (alpha 2 92 Arg. leads to Leu gamma 2) on fetal oxygen affinity and erythropoiesis. Pediatr Res 1979, 13, 851–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Q.H.; Nagel, R.L. Allosteric Transition and Ligand Binding in Hemoglobin Chesapeake. Journal of Biological Chemistry 249, 7255-7259. [CrossRef]

- Taketa, F.; Huang, Y.; Libnoch, J.; Dessel, B. Hemoglobin Wood beta97(FG4) His replaced by Leu. A new high-oxygen-aff inity hemoglobin associated with familial erythrocytosis. Biochimica et biophysica acta . [CrossRef]

- Charache, S. A manifestation of abnormal hemoglobins of man: altered oxygen affinity. Hemoglobin Chesapeake: from the clinic to the laboratory, and back again. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1974, 241, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, C.S.; Hampson, R.; Gordon, S.; Jones, R.T.; Novy, M.J.; Brimhall, B.; Edwards, M.J.; Koler, R.D. Erythrocytosis Secondary to Increased Oxygen Affinity of a Mutant Hemo globin, Hemoglobin Kempsey. Blood 31, 623-632. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.; Charache, S.; Hathaway, P. The effect of hemoglobin F-Chesapeake (alpha 2 92 Arg. leads to Leu ga mma 2) on fetal oxygen affinity and erythropoiesis. Pediatric Research 1979, 851-853.

- Wajcman, H.; Galactéros, F. Hemoglobins With High Oxygen Affinity Leading to Erythrocytosis. New V ariants and New Concepts. Hemoglobin 29, 91-106. [CrossRef]

- Pirastru, M.; Manca, L.; Trova, S.; Mereu, P. Biochemical and Molecular Analysis of the Hb Lepore Boston Washington in a Syrian Homozygous Child. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017, 1261972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harteveld, C.L.; Wijermans, P.W.; Arkesteijn, S.G.; Van Delft, P.; Kerkhoffs, J.L.; Giordano, P.C. Hb Lepore-Leiden: a new delta/beta rearrangement associated with a beta-thalassemia minor phenotype. Hemoglobin 2008, 32, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seward, D.P.; Ware, R.E.; Kinney, T.R. Hemoglobin sickle-Lepore: report of two siblings and review of the literature. Am J Hematol 1993, 44, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabile, E.; Testa, R.; Consalvo, C.; Dickerhoff, R.; Schilirò, G. Association of Hb S/Hb lepore and δβ-thalassemia/Hb lepore in Sicilian patients: Review of the presence of Hb lepore in Sicily. European Journal of Haematology 55, 126-130. [CrossRef]

- Efremov, G.D. Hemoglobins Lepore and anti-Lepore. Hemoglobin 1978, 2, 197–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaibunruang, A.; Srivorakun, H.; Fucharoen, S.; Fucharoen, G.; Sae-Ung, N.; Sanchaisuriya, K. Interactions of hemoglobin Lepore (deltabeta hybrid hemoglobin) with v arious hemoglobinopathies: A molecular and hematological characteristi cs and differential diagnosis. Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases . [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Tang, X.W.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.Y.; Zuo, L.D.; Li, D.Z. Hb Lepore-Hong Kong: First Report of a Novel delta/beta-Globin Gene Fusion in a Chinese Family. Hemoglobin 2021, 45, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, D.M.; Higgs, D.R.; Winichagoon, P.; Clegg, J.B.; Weatherall, D.J. Haemoglobin Constant Spring has an unstable α chain messenger RNA. British Journal of Haematology 51, 405-413. [CrossRef]

- Thonglairoam, V.; Winichagoon, P.; Fucharoen, S.; Tanphaichitr, V.S.; Pung-amritt, P.; Embury, S.H.; Wasi, P. Hemoglobin constant spring in Bangkok: molecular screening by selective enzymatic amplification of the alpha 2-globin gene. Am J Hematol 1991, 38, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Sanchaisuriya, K.; Wongprachum, K.; Nguyen, M.D.; Phan, T.T.; Vo, V.T.; Sanchaisuriya, P.; Fucharoen, S.; Schelp, F.P. Hemoglobin Constant Spring is markedly high in women of an ethnic minority group in Vietnam: a community-based survey and hematologic features. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2014, 52, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomoui, W.; Fucharoen, G.; Sanchaisuriya, K.; Nguyen, V.H.; Fucharoen, S. Hemoglobin Constant Spring among Southeast Asian Populations: Haplotypic Heterogeneities and Phylogenetic Analysis. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0145230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropp, G.L.; Fucharoen, S.; Embury, S.H. Selective enzymatic amplification of alpha 2-globin DNA for detection of the hemoglobin Constant Spring mutation. Blood 1989, 73, 1987–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W.L. Hemoglobin constant spring can interfere with glycated hemoglobin measurements by boronate affinity chromatography. Clin Chem 2007, 53, 142–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoenkwan, P.; Sirichotiyakul, S.; Chanprapaph, P.; Tongprasert, F.; Taweephol, R.; Sae-Tung, R.; Sanguansermsri, T. Anemia and hydrops in a fetus with homozygous hemoglobin constant spring. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2006, 28, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, S.A.; O'Branski, E.E.; Rosse, W.F.; Ware, R.E. Hemoglobin S/O(Arab): thirteen new cases and review of the literature. Am J Hematol 1999, 60, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, S. Clinical and hematological features of homozygous hemoglobin O-Arab [b eta 121 Glu → Lys]. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 60, 506-507. [CrossRef]

- Sangaré, A.; Sanogo, I.; Meité, M.; Ambofo, Y.; Abesopie, V.; Ségbéna, A.; Tolo, A. [Hemoglobin O Arab in Ivory Coast and western Africa]. Medecine tropicale : revue du Corps de sante colonial 52, 5.

- Hafsia, R.; Gouider, E.; Ben Moussa, S.; Ben Salah, N.; Elborji, W.; Hafsia, A. [Hemoglobin O Arab: about 20 cases]. Tunis Med 2007, 85, 637–640. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, P.F.; Miller, C.; Grey, R.; Seakins, M.; DeJong, W.W.; Went, L.N. Hemoglobin O Arab in Four Negro Families and Its Interaction with Hemo globin S and Hemoglobin C. N Engl J Med 283, 1417-1425. [CrossRef]

- El-Hazmi, M.A.F.; Lehmann, H. Human Haemoglobins and Haemoglobinopathies in Arabia: Hb O Arab in Sau di Arabia. Acta Haematol 63, 268-273. [CrossRef]

- Merritt, D.; Jones, R.T.; Head, C.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Fairbanks, V.F.; Steinberg, M.H.; Coleman, M.B.; Rodgers, G.P. Hb Seal Rock [(alpha 2)142 term-->Glu, codon 142 TAA-->GAA]: an extended alpha chain variant associated with anemia, microcytosis, and alpha-thalassemia-2 (-3.7 Kb). Hemoglobin 1997, 21, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prehu, C.; Moradkhani, K.; Riou, J.; Bahuau, M.; Launay, P.; Martin, N.; Wajcman, H.; Goossens, M.; Galacteros, F. Chronic hemolytic anemia due to novel alpha-globin chain variants: critical location of the mutation within the gene sequence for a dominant effect. Haematologica 2009, 94, 1624–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattori, A.; Kimura, E.M.; Albuquerque, D.M.; Oliveira, D.M.; Costa, F.F.; Sonati, M.F. Hb Indianapolis [beta112 (G14) Cys-->Arg] as the probable cause of moderate hemolytic anemia and renal damage in a Brazilian patient. Am J Hematol 2007, 82, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S.J.; Timbs, A.T.; McCarthy, J.; Gallienne, A.E.; Proven, M.; Rugless, M.J.; Lopez, H.; Eglinton, J.; Dziedzic, D.; Beardsall, M.; et al. Ten Years of Routine alpha- and beta-Globin Gene Sequencing in UK Hemoglobinopathy Referrals Reveals 60 Novel Mutations. Hemoglobin 2016, 40, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Outeirino, J.; Casey, R.; White, J.M.; Lehmann, H. Haemoglobin Madrid β 115 (G17) Alanine→Proline: an U nstable Variant Associated with Haemolytic Anaemia. Acta Haematol 52, 53-60. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Park, S.S.; Jung, H.L.; Keum, D.H.; Park, H.; Chang, Y.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Cho, H.I. Hb Madrid [beta115(G17)Ala-->Pro] in a Korean family with chronic hemolytic anemia. Hemoglobin 2000, 24, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edison, E.S.; Shaji, R.V.; Devi, S.G.; Kumar, S.S.; Srivastava, A.; Chandy, M. Hb Showa-Yakushiji [beta110(G12)Leu-->Pro] in four unrelated patients from west Bengal. Hemoglobin 2005, 29, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villegas, A.; Ropero, P.; Nogales, A.; González, F.A.; Mateo, M.; Mazo, E.; Rodrigo, E.; Arias, M. Hb Santander [β34(B16)Val→Asp (GTC→GAC)]: A New Unstable Variant Found as a De Novo Mutation in a Spanish Patient. Hemoglobin 27, 31-35. [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuji, T.; Miwa, S.; Ohba, Y.; Hattori, Y.; Miyaji, T.; Hino, S.; Matsumoto, N. A new unstable hemoglobin, Hb Yokohama beta 31 (B13)Leu substituting for Pro, causing hemolytic anemia. Hemoglobin 1981, 5, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huehns, E.R.; Hecht, F.; Yoshida, A.; Stamatoyannopoulos, G.; Hartman, J.; Motulsky, A.G. Hemoglobin-Seattle (α2Aβ276 Glu): An Unstable Hemoglobin Causing Chron ic Hemolytic Anemia. Blood 36, 209-218. [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, J.D.; Baxter, J.K.; Moran, A.M.; Kubic, K.S.; Ehmann, W.C. Two unstable beta chain variants associated with beta-thalassemia: Hb Miami [beta116(G18)his-->Pro], and Hb Hershey [beta70(E14)Ala-->Gly], and a second unstable Hb variant at 170: Hb Abington [beta70(E14)Ala-->Pro]. Hemoglobin 2005, 29, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ideguchi, H. [Effects of abnormal Hb on red cell membranes]. Rinsho Byori 1999, 47, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacob, H.S.; Winterhalter, K.H. The role of hemoglobin heme loss in Heinz body formation: studies with a partially heme-deficient hemoglobin and with genetically unstable h emoglobins. Journal of Clinical Investigation 49, 2008-2016. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, H.; Winterhalter, K. Unstable Hemoglobins: The Role of Heme Loss in Heinz Body Formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 65, 697-701. [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C.; Carrell, R.W. Studies of hemoglobin denaturation and Heinz body formation in the unstable hemoglobins. J Clin Invest 1974, 54, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Shigemasa, Y.; Abe, Y.; Ohgushi, I.; Ueno, E.; Shimamoto, F. Molecular biosensing mechanisms in the spleen for the removal of aged and damaged red cells from the blood circulation. Sensors (Basel) 2010, 10, 7099–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmers, R.N.; Mulley, J.C.; Hyland, V.J.; Callen, D.F.; Sutherland, G.R. Mapping the human alpha globin gene complex to 16p13.2----pter. J Med Genet 1987, 24, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, R.D.; Jonasson, J.A.; McGee, J.O.; Patil, S.; Ionasescu, V.V.; Weatherall, D.J.; Higgs, D.R. High resolution gene mapping of the human alpha globin locus. J Med Genet 1987, 24, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, R.J.; Peden, J.F.; Lloyd, C.; Horsley, S.W.; Clark, K.; Tufarelli, C.; Kearney, L.; Buckle, V.J.; Doggett, N.A.; Flint, J.; et al. Sequence, structure and pathology of the fully annotated terminal 2 Mb of the short arm of human chromosome 16. Hum Mol Genet 2001, 10, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, D.R.; Wainscoat, J.S.; Flint, J.; Hill, A.V.; Thein, S.L.; Nicholls, R.D.; Teal, H.; Ayyub, H.; Peto, T.E.; Falusi, A.G.; et al. Analysis of the human alpha-globin gene cluster reveals a highly informative genetic locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986, 83, 5165–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, A.; Picanco, I.; Seuanes, F.; Seixas, M.T.; Faustino, P. Novel large deletions in the human alpha-globin gene cluster: Clarifying the HS-40 long-range regulatory role in the native chromosome environment. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2010, 45, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, D.R.; Hill, A.V.; Nicholls, R.; Goodbourn, S.E.; Ayyub, H.; Teal, H.; Clegg, J.B.; Weatherall, D.J. Molecular rearrangements of the human alpha-globin gene cluster. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1985, 445, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, C.S.; Wilkie, A.O.; Drysdale, H.C.; Wood, W.G.; Vickers, M.A.; Sharpe, J.; Ayyub, H.; Pretorius, I.M.; Buckle, V.J.; Higgs, D.R. Alpha-thalassemia caused by a large (62 kb) deletion upstream of the human alpha globin gene cluster. Blood 1990, 76, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, M.H. A New Trans-Acting Modulator of Fetal Hemoglobin? Acta Haematol 2018, 140, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.; Galanello, R. Beta-thalassemia. Genetics in Medicine 12, 61-76. [CrossRef]

- Ana, M.; Seixas, S.; Lopes, A.; Bento, C.; Prata, M.; Amorim, A. Evolutionary Constraints in the β-Globin Cluster: The Signature of Pur ifying Selection at the δ-Globin (HBD) Locus and Its Role in Developme ntal Gene Regulation. Genome Biology and Evolution . [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Draper, P.N.; De Braekeleer, M. High-resolution chromosomal localization of the β-gene of the human β- globin gene complex by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Genome Res 39, 269-274. [CrossRef]

- Gusella, J.; Varsanyi-Breiner, A.; Kao, F.T.; Jones, C.; Puck, T.T.; Keys, C.; Orkin, S.; Housman, D. Precise localization of human beta-globin gene complex on chromosome 11. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1979, 76, 5239–5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deisseroth, A.; Nienhuis, A.; Lawrence, J.; Giles, R.; Turner, P.; Ruddle, F.H. Chromosomal localization of human beta globin gene on human chromosome 11 in somatic cell hybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1978, 75, 1456–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.E.; Orkin, S.H. Update on fetal hemoglobin gene regulation in hemoglobinopathies. Curr Opin Pediatr 2011, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.M.; Dumoulin, A.; Li, X.; Manning, L.R. Normal and abnormal protein subunit interactions in hemoglobins. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 19359–19362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, R.D.; Russell, J.E.; Watmough, N.J.; Baker, E.N.; Brittain, T. The role of beta chains in the control of the hemoglobin oxygen binding function: chimeric human/mouse proteins, structure, and function. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 15669–15675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Pang, J.; Reddy, K.S.; Surrey, S.; Adachi, K. Role of beta112 Cys (G14) in homo- (beta4) and hetero- (alpha2 beta2) tetramer hemoglobin formation. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 14179–14185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgstahl, G.; Rogers, P.; Arnone, A. The 1.8 A structure of carbonmonoxy-beta 4 hemoglobin. Analysis of a h omotetramer with the R quaternary structure of liganded alpha 2 beta 2 hemoglobin. Journal of molecular biology . [CrossRef]

- Walder, J.A.; Chatterjee, R.; Steck, T.L.; Low, P.S.; Musso, G.F.; Kaiser, E.T.; Rogers, P.H.; Arnone, A. The interaction of hemoglobin with the cytoplasmic domain of band 3 of the human erythrocyte membrane. The Journal of biological chemistry 1984, 259, 10238–10246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gell, D.; Kong, Y.; Eaton, S.A.; Weiss, M.J.; Mackay, J.P. Biophysical Characterization of the α-Globin Binding Protein α-Hemoglo bin Stabilizing Protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry 277, 40602-40609. [CrossRef]

- Domingues-Hamdi, E.; Vasseur, C.; Fournier, J.B.; Marden, M.C.; Wajcman, H.; Baudin-Creuza, V. Role of alpha-globin H helix in the building of tetrameric human hemoglobin: interaction with alpha-hemoglobin stabilizing protein (AHSP) and heme molecule. PLoS One 2014, 9, e111395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Gell, D.A.; Zhou, S.; Gu, L.; Kong, Y.; Li, J.; Hu, M.; Yan, N.; Lee, C.; Rich, A.M.; et al. Molecular mechanism of AHSP-mediated stabilization of alpha-hemoglobin. Cell 2004, 119, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Kong, Y.; Dore, L.C.; Abdulmalik, O.; Katein, A.M.; Zhou, S.; Choi, J.K.; Gell, D.; Mackay, J.P.; Gow, A.J.; et al. An erythroid chaperone that facilitates folding of alpha-globin subunits for hemoglobin synthesis. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollan, T.L.; Yu, X.; Weiss, M.J.; Olson, J.S. The Role of Alpha-Hemoglobin Stabilizing Protein in Redox Chemistry, D enaturation, and Hemoglobin Assembly. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 12, 219-231. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Mollan, T.L.; Butler, A.; Gow, A.J.; Olson, J.S.; Weiss, M.J. Analysis of human alpha globin gene mutations that impair binding to the alpha hemoglobin stabilizing protein. Blood 2009, 113, 5961–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, H.P.; Vadolas, J. Controlling alpha-globin: a review of alpha-globin expression and its impact on beta-thalassemia. Haematologica 2008, 93, 1868–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, G.; Theodorsson, E. Inherited, non-spherocytic haemolysis due to deficiency of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2007, 67, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, H.Y.; Cheng, M.L.; Chiu, D.T. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase--from oxidative stress to cellular functions and degenerative diseases. Redox Rep 2007, 12, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arese, P.; Gallo, V.; Pantaleo, A.; Turrini, F. Life and Death of Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) Deficient E rythrocytes – Role of Redox Stress and Band 3 Modifications. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy . [CrossRef]

- Janney, S.K.; Joist, J.J.; Fitch, C.D. Excess release of ferriheme in G6PD-deficient erythrocytes: possible cause of hemolysis and resistance to malaria. Blood 1986, 67, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, M.D.; Zuo, L.; Lubin, B.H.; Chiu, D.T. NADPH, not glutathione, status modulates oxidant sensitivity in normal and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient erythrocytes. Blood 1991, 77, 2059–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.J.; Zielenski, J.; Tsui, L.C.; Wells, P.G. An embryoprotective role for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in deve lopmental oxidative stress and chemical teratogenesis. The FASEB Journal 14, 111-127. [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.O.; Jhang, J.S.; Pham, H.P.; Hod, E.A.; Zimring, J.C.; Spitalnik, S.L. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in transfusion medicine: the unknown risks. Vox Sang 2013, 105, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fibach, E.; Rachmilewitz, E. The role of oxidative stress in hemolytic anemia. Curr Mol Med 2008, 8, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghpanah, S.; Hosseini-Bensenjan, M.; Zekavat, O.R.; Bordbar, M.; Karimi, M.; Ramzi, M.; Asmarian, N. The Effect of N-Acetyl Cysteine and Vitamin E on Oxidative Status and Hemoglobin Level in Transfusion-Dependent Thalassemia Patients: A Syst ematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Halima, W.M.A.B.; Hannemann, A.; Rees, D.; Brewin, J.; Gibson, J. The Effect of Antioxidants on the Properties of Red Blood Cells From P atients With Sickle Cell Anemia. Frontiers in Physiology.

- Pallotta, V.; Gevi, F.; D'Alessandro, A.; Zolla, L. Storing red blood cells with vitamin C and N-acetylcysteine prevents oxidative stress-related lesions: a metabolomics overview. Blood Transfus 2014, 12, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delesderrier, E.; Curioni, C.; Omena, J.; Macedo, C.R.; Cople-Rodrigues, C.; Citelli, M. Antioxidant nutrients and hemolysis in sickle cell disease. Clin Chim Acta 2020, 510, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibach, E.; Rachmilewitz, E.A. The role of antioxidants and iron chelators in the treatment of oxidative stress in thalassemia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2010, 1202, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonkovsky, H.L.; Guo, J.T.; Hou, W.; Li, T.; Narang, T.; Thapar, M. Porphyrin and heme metabolism and the porphyrias. Compr Physiol 2013, 3, 365–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissell, D.M.; Lai, J.C.; Meister, R.K.; Blanc, P.D. Role of delta-aminolevulinic acid in the symptoms of acute porphyria. Am J Med 2015, 128, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, C.J. Editorial: Hematin and porphyria. N Engl J Med 1975, 293, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenhunen, R.; Mustajoki, P. Acute Porphyria: Treatment with Heme. Semin Liver Dis 18, 53-55. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Li, T.; Hou, W.; Zheng, J.; Schrum, L.W.; Bonkovsky, H.L. Lon peptidase 1 (LONP1)-dependent breakdown of mitochondrial 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase protein by heme in human liver cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 2011, 286, 26424–26430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hift, R.J.; Thunell, S.; Brun, A. Drugs in porphyria: From observation to a modern algorithm-based system for the prediction of porphyrogenicity. Pharmacol Ther 2011, 132, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, L.C.; Smith, S.J.; Cox, T.M. Biosynthesis of delta-aminolevulinic acid and the regulation of heme formation by immature erythroid cells in man. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1991, 266, 22010–22018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, M.H. Hydroxyurea Treatment for Sickle Cell Disease. The Scientific World JOURNAL 2, 1706-1728. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, M.H. Therapies to increase fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell disease. Curr Hematol Rep 2003, 2, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fathallah, H.; Atweh, G.F. Induction of fetal hemoglobin in the treatment of sickle cell disease. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2006, 2006, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokic, V.P.; Smith, R.D.; Beleslin-Cokic, B.B.; Njoroge, J.M.; Miller, J.L.; Gladwin, M.T.; Schechter, A.N. Hydroxyurea induces fetal hemoglobin by the nitric oxide–dependent activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2003, 111, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, G.P.; Dover, G.J.; Noguchi, C.T.; Schechter, A.N.; Nienhuis, A.W. Hematologic Responses of Patients with Sickle Cell Disease to Treatmen t with Hydroxyurea. N Engl J Med 322, 1037-1045. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N. Hydroxyurea therapy: improving the lives of patients with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Nurs 2006, 32, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, M.A.; Brugnara, C.; Dover, G.J.; Schapira, L.; Charache, S.; Bunn, H.F. Treatment of Sickle Cell Anemia with Hydroxyurea and Erythropoietin. N Engl J Med 323, 366-372. [CrossRef]

- Dover, G.; Samuel, C. Hydroxyurea induction of fetal hemoglobin synthesis in sickle-cell dis ease. Seminars in Oncology 1992, 19, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, R.F.; Glenthøj, A.; Barcellini, W.; Verhovsek, M.; Rothman, J.A.; Morado, M.; Layton, D.M.; Andres, O.; Galactéros, F.; van Beers, E.J.; et al. Long-Term Hemoglobin Response and Reduction in Transfusion Burden Are Maintained in Patients with Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency Treated with Mitapivat. Blood 2022, 140, 5313–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, R.F.; Rose, C.; Layton, D.M.; Galacteros, F.; Barcellini, W.; Morton, D.H.; van Beers, E.J.; Yaish, H.; Ravindranath, Y.; Kuo, K.H.M.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Mitapivat in Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, K.H.; Layton, D.M.; Lal, A.; Al-Samkari, H.; Bhatia, J.; Tong, B.; Lynch, M.; Uhlig, K.; Vichinsky, E.P. Results from a Phase 2 Study of Mitapivat in Adults with Non–Transfusion-Dependent Alpha- or Beta-Thalassemia. Hematology, Transfusion and Cell Therapy 2021, 43, S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, K.H.M.; Layton, D.M.; Lal, A.; Al-Samkari, H.; Kosinski, P.A.; Tong, B.; Estepp, J.H.; Uhlig, K.; Vichinsky, E.P. Mitapivat Improves Markers of Erythropoietic Activity in Long-Term Study of Adults with Alpha- or Beta-Non-Transfusion-Dependent Thalassemia. Blood 2022, 140, 2479–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, K.; Layton, D.; Lal, A.; Al-Samkari, H.; Bhatia, J.; Kosinski, P.; Tong, B.; Lynch, M.; Uhlig, K.; Vichinsky, E. S116: Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of the Oral Pyruvate Kinase Activator Mitapivat in Adults with Non—Transfusion-Dependent Alpha- or Beta-Thalassemia. HemaSphere 2022, 6, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.Z.; Conrey, A.; Frey, I.; Gwaabe, E.; Menapace, L.A.; Tumburu, L.; Lundt, M.; Li, Q.; Glass, K.; Iyer, V.; et al. Mitapivat (AG-348) Demonstrates Safety, Tolerability, and Improvements in Anemia, Hemolysis, Oxygen Affinity, and Hemoglobin S Polymerization Kinetics in Adults with Sickle Cell Disease: A Phase 1 Dose Escalation Study. Blood 2021, 138, 10–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilo, F.; Angelucci, E. Mitapivat for sickle cell disease and thalassemia. Drugs Today (Barc) 2023, 59, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musallam, K.M.; Taher, A.T.; Cappellini, M.D. Right in time: Mitapivat for the treatment of anemia in alpha- and beta-thalassemia. Cell Rep Med 2022, 3, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olubiyi, O.O.; Olagunju, M.O.; Strodel, B. Rational Drug Design of Peptide-Based Therapies for Sickle Cell Disease. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.T.; Ogu, U.O. Sickle cell disease in the new era: advances in drug treatment. Transfus Apher Sci 2022, 61, 103555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.A.; Ahmad, A.; Chaudry, H.; Aiman, W.; Aamir, S.; Anwar, M.Y.; Khan, A. Efficacy and safety of recently approved drugs for sickle cell disease: a review of clinical trials. Exp Hematol 2020, 92, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataga, K.I.; Desai, P.C. Advances in new drug therapies for the management of sickle cell disease. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 2018, 6, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Conran, N. Emerging pharmacotherapeutic approaches for the management of sickle cell disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2019, 20, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carden, M.A.; Little, J. Emerging disease-modifying therapies for sickle cell disease. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1710–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Ghatge, M.S.; Donkor, A.K.; Musayev, F.N.; Deshpande, T.M.; Al-Awadh, M.; Alhashimi, R.T.; Zhu, H.; Omar, A.M.; Telen, M.J.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Investigation of Novel Nitric Oxide (NO)-Releasing Aromatic Aldehydes as Drug Candidates for the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, A.; Lui, F.E.; Wassaf, D.; Yefidoff-Freedman, R.; Casalena, D.; Palmer, M.A.; Meadows, J.; Mozzarelli, A.; Ronda, L.; Abdulmalik, O.; et al. Identification of a small molecule that increases hemoglobin oxygen affinity and reduces SS erythrocyte sickling. ACS chemical biology 2014, 9, 2318–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassa, T.; Strader, M.B.; Nakagawa, A.; Zapol, W.M.; Alayash, A.I. Targeting betaCys93 in hemoglobin S with an antisickling agent possessing dual allosteric and antioxidant effects. Metallomics 2017, 9, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassa, T.; Wood, F.; Strader, M.B.; Alayash, A.I. Antisickling Drugs Targeting betaCys93 Reduce Iron Oxidation and Oxidative Changes in Sickle Cell Hemoglobin. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garel, M.C.; Domenget, C.; Caburi-Martin, J.; Prehu, C.; Galacteros, F.; Beuzard, Y. Covalent binding of glutathione to hemoglobin. I. Inhibition of hemogl obin S polymerization. Journal of Biological Chemistry 261, 14704-14709. [CrossRef]

- Garel, M.C.; Domenget, C.; Galacteros, F.; Martin-Caburi, J.; Beuzard, Y. Inhibition of erythrocyte sickling by thiol reagents. Molecular pharmacology 1984, 26, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdulmalik, O.; Safo, M.; Qiukan, C.; Jisheng, Y.; Brugnara, C.; Ohene-Frempong, K.; Abraham, D.; Asakura, T. 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural modifies intracellular sickle haemoglobin a nd inhibits sickling of red blood cells †,‡. British Journal of Haematology . [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.G.; Pagare, P.P.; Ghatge, M.S.; Safo, R.P.; Gazi, A.; Chen, Q.; David, T.; Alabbas, A.B.; Musayev, F.N.; Venitz, J.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Ester and Ether Derivatives of Antisickling Agent 5-HMF for the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. Mol Pharm 2017, 14, 3499–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, W.; Mathews, D.; McKew, J.; Shen, X.; Kato, G.J. A Phase 1, First-in-Man, Dose-Response Study of Aes-103 (5-HMF), an Anti-Sickling, Allosteric Modifier of Hemoglobin Oxygen Affinity in Healthy Norman Volunteers. Blood 2012, 120, 3210–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.; Ao-Ieong, E.S.Y.; Williams, A.T.; Jani, V.P.; Muller, C.R.; Yalcin, O.; Cabrales, P. Increased Hemoglobin Oxygen Affinity With 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Supports Cardiac Function During Severe Hypoxia. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannemann, A.; Cytlak, U.M.; Rees, D.C.; Tewari, S.; Gibson, J.S. Effects of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural on the volume and membrane permeability of red blood cells from patients with sickle cell disease. J Physiol 2014, 592, 4039–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhashimi, R.T.; Ghatge, M.S.; Donkor, A.K.; Deshpande, T.M.; Anabaraonye, N.; Alramadhani, D.; Danso-Danquah, R.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Musayev, F.N.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Antisickling Investigation of a Nitric Oxide-Releasing Prodrug of 5HMF for the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safo, M.; Abdulmalik, O.; Danso-Danquah, R.; Burnett, J.; Samuel, N.; Joshi, G.; Musayev, F.; Asakura, T.; Abraham, D. Structural basis for the potent antisickling effect of a novel class o f five-membered heterocyclic aldehydic compounds. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2004, 47, 4665–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safo, M.K.; Kato, G.J. Therapeutic strategies to alter the oxygen affinity of sickle hemoglobin. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2014, 28, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaventura, C.; Fago, A.; Henkens, R.; Crumbliss, A.L. Critical Redox and Allosteric Aspects of Nitric Oxide Interactions wit h Hemoglobin. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 6, 979-991. [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Ognibene, F.P.; Pannell, L.K.; Nichols, J.S.; Pease-Fye, M.E.; Shelhamer, J.H.; Schechter, A.N. Relative role of heme nitrosylation and beta-cysteine 93 nitrosation in the transport and metabolism of nitric oxide by hemoglobin in the human circulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 9943–9948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.; Stamler, J.; Piantadosi, C. Hemoglobin, nitric oxide and molecular mechanisms of hypoxic vasodilat ion. Trends in Molecular Medicine . [CrossRef]

- Sonveaux, P.; Lobysheva, I.I.; Feron, O.; McMahon, T.J. Transport and peripheral bioactivities of nitrogen oxides carried by red blood cell hemoglobin: role in oxygen delivery. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007, 22, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamler, J.S.; Jia, L.; Eu, J.P.; McMahon, T.J.; Demchenko, I.T.; Bonaventura, J.; Gernert, K.; Piantadosi, C.A. Blood flow regulation by S-nitrosohemoglobin in the physiological oxygen gradient. Science 1997, 276, 2034–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frehm, E.; Bonaventura, J.; Gow, A. Serial Review: Biomedical Implications for Hemoglobin Interactions wit h Nitric Oxide Serial Review Editors: Mark T. Gladwin and Rakesh Patel S-NITROSOHEMOGLOBIN: AN ALLOSTERIC MEDIATOR OF NO GROUP FUNCTION IN M AMMALIAN VASCULATURE. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 2004, 37, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.; Liu, X.; Du, J.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y. The role of hemoglobin in nitric oxide transport in vascular system. Medicine in Novel Technology and Devices 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, J.; Hutchings, A.; Kerby, J.D.; Patel, R.P. The hemoglobin-nitric oxide axis: implications for transfusion therapeutics. Transfusion Alternatives in Transfusion Medicine 2008, 9, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.M.; Abdulmalik, O.; Ghatge, M.S.; Muhammad, Y.A.; Paredes, S.D.; El-Araby, M.E.; Safo, M.K. An Investigation of Structure-Activity Relationships of Azolylacryloyl Derivatives Yielded Potent and Long-Acting Hemoglobin Modulators for Reversing Erythrocyte Sickling. Biomolecules 10, 1508. [CrossRef]

- Pagare, P.P.; Ghatge, M.S.; Musayev, F.N.; Deshpande, T.M.; Chen, Q.; Braxton, C.; Kim, S.; Venitz, J.; Zhang, Y.; Abdulmalik, O.; et al. Rational design of pyridyl derivatives of vanillin for the treatment o f sickle cell disease. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 26, 2530-2538. [CrossRef]

- Pagare, P.P.; Rastegar, A.; Abdulmalik, O.; Omar, A.M.; Zhang, Y.; Fleischman, A.; Safo, M.K. Modulating hemoglobin allostery for treatment of sickle cell disease: current progress and intellectual property. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 32, 115-130. [CrossRef]

- Gopalsamy, A.; Aulabaugh, A.E.; Barakat, A.; Beaumont, K.C.; Cabral, S.; Canterbury, D.P.; Casimiro-Garcia, A.; Chang, J.S.; Chen, M.Z.; Choi, C.; et al. PF-07059013: A Noncovalent Modulator of Hemoglobin for Treatment of Si ckle Cell Disease. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 64, 326-342. [CrossRef]

- Saunthararajah, Y. Targeting sickle cell disease root-cause pathophysiology with small molecules. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1720–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janz, J.M.; Piotrowski, D.W.; Beaumont, K.; Chang, J.S.; Jasti, J.; Narula, J.; Sahasrabudhe, P.; Wenzel, Z.; Rao, D.; Barakat, A.; et al. A Novel Non-Covalent Modulator of Hemoglobin Improves Anemia and Reduces Sickling in a Mouse Model of Sickle Cell Disease. Blood 2019, 134, 207–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oder, E.; Safo, M.K.; Abdulmalik, O.; Kato, G.J. New developments in anti-sickling agents: can drugs directly prevent the polymerization of sickle haemoglobin in vivo? Br J Haematol 2016, 175, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalf, B.; Chuang, C.; Dufu, K.; Patel, M.P.; Silva-Garcia, A.; Johnson, C.; Lu, Q.; Partridge, J.R.; Patskovska, L.; Patskovsky, Y.; et al. Discovery of GBT440, an Orally Bioavailable R-State Stabilizer of Sick le Cell Hemoglobin. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters 8, 321-326. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Little, J.A.; Pecker, L.H. Advances in the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2018, 93, 1810–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, N.; Galacteros, F.; Brugnara, C. 2015 Clinical trials update in sickle cell anemia. American J Hematol 90, 934-950. [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, T.M.; Pagare, P.P.; Ghatge, M.S.; Chen, Q.; Musayev, F.N.; Venitz, J.; Zhang, Y.; Abdulmalik, O.; Safo, M.K. Rational modification of vanillin derivatives to stereospecifically de stabilize sickle hemoglobin polymer formation. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 956-964. [CrossRef]

- Scipioni, M.; Kay, G.; Megson, I.L.; Kong Thoo Lin, P. Synthesis of novel vanillin derivatives: novel multi-targeted scaffold ligands against Alzheimer's disease. Med. Chem. Commun. 10, 764-777. [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, F.; Ross, A.; Lema, P.P.; Vachon, P. Pharmacokinetics of vanillin and its effects on mechanical hypersensit ivity in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Phytotherapy Research 24, 525-530. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, Z.; Rafiq, M.; Seo, S.-Y.; Babar, M.M.; Zaidi, N.-u.-S.S. Synthesis, kinetic mechanism and docking studies of vanillin derivativ es as inhibitors of mushroom tyrosinase. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 23, 5870-5880. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, D.J.; Mehanna, A.S.; Wireko, F.C.; Whitney, J.; Thomas, R.P.; Orringer, E.P. Vanillin, a potential agent for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. Blood 1991, 77, 1334–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulmalik, O.; Pagare, P.P.; Huang, B.; Xu, G.G.; Ghatge, M.S.; Xu, X.; Chen, Q.; Anabaraonye, N.; Musayev, F.N.; Omar, A.M.; et al. VZHE-039, a novel antisickling agent that prevents erythrocyte sickling under both hypoxic and anoxic conditions. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagare, P.P.; Ghatge, M.S.; Chen, Q.; Musayev, F.N.; Venitz, J.; Abdulmalik, O.; Zhang, Y.; Safo, M.K. Exploration of Structure-Activity Relationship of Aromatic Aldehydes Bearing Pyridinylmethoxy-Methyl Esters as Novel Antisickling Agents. J Med Chem 2020, 63, 14724–14739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Maestre-Reyna, M.; Hsu, K.C.; Wang, H.C.; Liu, C.I.; Jeng, W.Y.; Lin, L.L.; Wood, R.; Chou, C.C.; Yang, J.M.; et al. Crowning proteins: modulating the protein surface properties using crown ethers. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2014, 53, 13054–13058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.; Dellacherie, E. Acylation of human hemoglobin with polyoxyethylene derivatives. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1984, 791, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, D.J.; Wireko, F.C.; Randad, R.S.; Poyart, C.; Kister, J.; Bohn, B.; Liard, J.F.; Kunert, M.P. Allosteric modifiers of hemoglobin: 2-[4-[[(3,5-disubstituted anilino)carbonyl]methyl]phenoxy]-2-methylpropionic acid derivatives that lower the oxygen affinity of hemoglobin in red cell suspensions, in whole blood, and in vivo in rats. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 9141–9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; D’Alessandro, A.; Ahmed, M.H.; Zhang, Y.; Song, A.; Ko, T.-P.; Nemkov, T.; Reisz, J.A.; Wu, H.; Adebiyi, M.; et al. Structural and Functional Insight of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate-Mediated Pathogenic Metabolic Reprogramming in Sickle Cell Disease. Scientific reports 7. [CrossRef]

- Wiesław, K.; Roth, R.; Levin, J. Hemoglobin, a newly recognized lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protei n that enhances LPS biological activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry . [CrossRef]

- Bahl, N.; Du, R.; Winarsih, I.; Ho, B.; Tucker-Kellogg, L.; Tidor, B.; Ding, J.L. Delineation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding sites on hemoglobin: from in silico predictions to biophysical characterization. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 37793–37803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechuga, G.C.; Souza-Silva, F.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Trugilho, M.R.O.; Valente, R.H.; Napoleao-Pego, P.; Dias, S.S.G.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Temerozo, J.R.; Carels, N.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Proteins Bind to Hemoglobin and Its Metabolites. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, S.; Nagel, R.L.; Bookchin, R.M.; Roth, E.F., Jr.; Tellez-Nagel, I. The binding of hemoglobin to membranes of normal and sickle erythrocytes. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1975, 375, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaklai, N.; Yguerabide, J.; Ranney, H.M. Interaction of hemoglobin with red blood cell membranes as shown by a fluorescent chromophore. Biochemistry 1977, 16, 5585–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yenamandra, A.; Marjoncu, D. Voxelotor: A Hemoglobin S Polymerization Inhibitor for the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. J Adv Pract Oncol 2020, 11, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Maggo, S.; Sadananden, U.K. Voxelotor: novel drug for sickle cell disease. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology 2020, 9, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Saraf, S.L.; Gordeuk, V.R. Systematic Review of Voxelotor: A First-in-Class Sickle Hemoglobin Polymerization Inhibitor for Management of Sickle Cell Disease. Pharmacotherapy 2020, 40, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.; Hemmaway, C.J.; Telfer, P.; Layton, D.M.; Porter, J.; Awogbade, M.; Mant, T.; Gretler, D.D.; Dufu, K.; Hutchaleelaha, A.; et al. A phase 1/2 ascending dose study and open-label extension study of voxelotor in patients with sickle cell disease. Blood 2019, 133, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchaleelaha, A.; Patel, M.; Washington, C.; Siu, V.; Allen, E.; Oksenberg, D.; Gretler, D.D.; Mant, T.; Lehrer-Graiwer, J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of voxelotor (GBT440) in healthy adults and patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2019, 85, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissa, M.; Vichinsky, E. Voxelotor for the treatment of sickle cell disease. Expert Rev Hematol 2021, 14, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, C.; Baudin-Creuza, V. [Role of alpha-hemoglobin molecular chaperone in the hemoglobin formation and clinical expression of some hemoglobinopathies]. Transfus Clin Biol 2015, 22, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favero, M.E.; Costa, F.F. Alpha-hemoglobin-stabilizing protein: an erythroid molecular chaperone. Biochem Res Int 2011, 2011, 373859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell, D.; Kong, Y.; Eaton, S.A.; Weiss, M.J.; Mackay, J.P. Biophysical characterization of the alpha-globin binding protein alpha-hemoglobin stabilizing protein. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 40602–40609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.J.; Zhou, S.; Feng, L.; Gell, D.A.; Mackay, J.P.; Shi, Y.; Gow, A.J. Role of alpha-hemoglobin-stabilizing protein in normal erythropoiesis and beta-thalassemia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2005, 1054, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandros, E.; Mollan, T.L.; Yu, X.; Wang, X.; Yao, Y.; D'Souza, J.; Gell, D.A.; Olson, J.S.; Weiss, M.J. Insights into hemoglobin assembly through in vivo mutagenesis of alpha-hemoglobin stabilizing protein. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 11325–11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleson, K.K.; Duffin, K.L.; Goldberg, D.E. Identification and characterization of falcilysin, a metallopeptidase involved in hemoglobin catabolism within the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 32411–32417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, C.E.; Goldberg, D.E. Plasmodium falciparum falcilysin: a metalloprotease with dual specificity. The Journal of biological chemistry 2003, 278, 38022–38028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, S.A. Subcellular multitasking - multiple destinations and roles for the Plasmodium falcilysin protease. Mol Microbiol 2007, 63, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponpuak, M.; Klemba, M.; Park, M.; Gluzman, I.Y.; Lamppa, G.K.; Goldberg, D.E. A role for falcilysin in transit peptide degradation in the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Mol Microbiol 2007, 63, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chance, J.P.; Fejzic, H.; Hernandez, O.; Istvan, E.S.; Andaya, A.; Maslov, N.; Aispuro, R.; Crisanto, T.; Nguyen, H.; Vidal, B.; et al. Development of piperazine-based hydroxamic acid inhibitors against falcilysin, an essential malarial protease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2018, 28, 1846–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Zheng, G.; Setegne, M.; Tenglin, K.; Izada, M.; Xie, H.; Zhai, L.; Orkin, S.H.; Dassama, L.M.K. A cell-permeant nanobody-based degrader that induces fetal hemoglobin. [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Izadi, M.; Tenglin, K.; Viennet, T.; Zhai, L.; Zheng, G.; Arthanari, H.; Dassama, L.M.K.; Orkin, S.H. Evolution of nanobodies specific for BCL11A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2218959120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahl, N.; Du, R.; Winarsih, I.; Ho, B.; Tucker-Kellogg, L.; Tidor, B.; Ding, J.L. Delineation of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding Sites on Hemoglobin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 286, 37793-37803. [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.R.; Samuels, I.; Binks, S.; Grinter, R. The structure of a haemoglobin-nanobody complex reveals human beta-subunit-specific interactions. Febs Lett 2024. [CrossRef]

- Aylaz, G.; Andac, M.; Denizli, A.; Duman, M. Recognition of human hemoglobin with macromolecularly imprinted polymeric nanoparticles using non-covalent interactions. J Mol Recognit 2021, 34, e2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakurel, K.P.; Zoldak, G.; Angelov, B.; Andreasson, J. On the feasibility of time-resolved X-ray powder diffraction of macromolecules using laser-driven ultrafast X-ray sources. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2024, 57, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakurel, K.P.; Nemergut, M.; Dzupponova, V.; Kropielnicki, K.; Savko, M.; Zoldak, G.; Andreasson, J. Design and fabrication of 3D-printed in situ crystallization plates for probing microcrystals in an external electric field. J Appl Crystallogr 2024, 57, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).