Introduction

Thalassemia is an inherited monogenic disease caused by the mutation in the beta globin (HBB) gene1. Although it’s monogenic origin, clinical severity of beta thalassemia (β-thalassemia) varies from very severe to mild. It has been noticed that a group of subjects present the disease at very early age and need regular transfusion for survival, on the other hand, cases also reported with late onset and do not require regular transfusion2. Recently, we reported the role of HBB gene mutation and alpha globin gene (HBA) mutation has a role in the β-thalassemia clinical severity which ultimately regulate the globin synthesis3,4. Other studies also reveal that genetic variants which regulate the fetal hemoglobin (HbF) production may also causes the β-thalassemia clinical severity.

The present knowledge of genotyped for thalassemia severity, either on globin chain or globin synthesis centric. However, a huge percentage of β-thalassemia subject, in spite of having same globin genotype, but possess extreme different phenotype severity. Thus, it may be involvement of non-globin genes, which might play crucial role for such phenotype heterogeneity. To decipher this phenotypic mystery, we recruited two index cases with same HBB mutant of β+/ β0 genotype [compound heterozygous IVS1-5(G>C) and CD26(G>A)], with HBA wild type.

Subjects and Methods

Along with the index cases, their parents also recruited for trio-based study. Although they posses same mutant HBB genotype, but clinically they were of extreme variations (

Table 1). This study was approved by the ethics committee of The University of Burdwan.

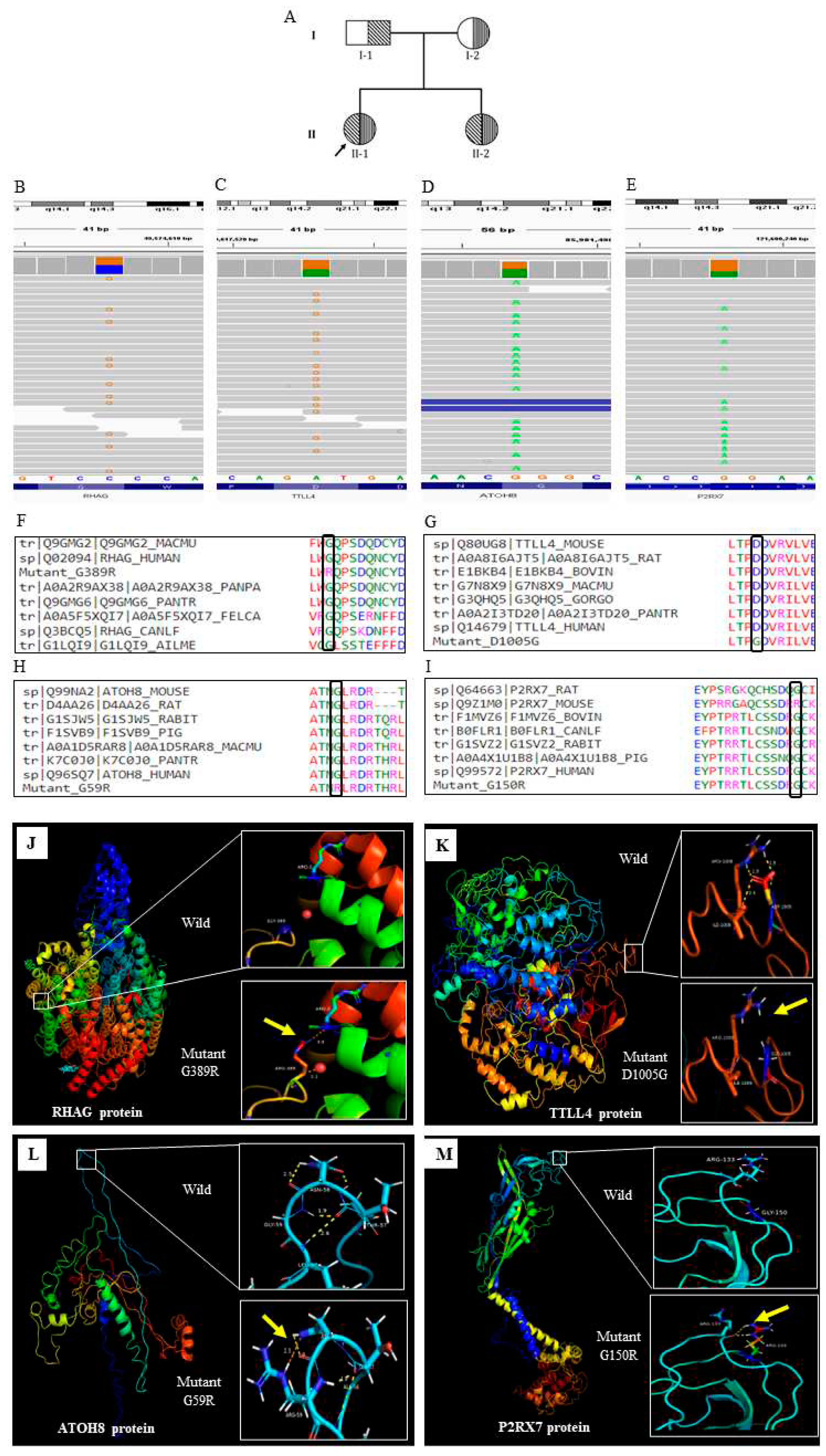

Subject 1, was presented the disease at 10 months of age and found to have severe anemia (steady state hemoglobin level was 6.1 g/dl). She undergone a regular blood transfusion at an interval of 2 months for the last 13 years (Table: 1). The sanger sequencing of

HBB gene confirms the β thalassemia disease with [IVS1-5(G>C) and CD26(G>A)]. Both the parents are found to be carrier for β thalassemia (

Figure 1A). She representing as severe, transfusion dependent thalassaemic subject

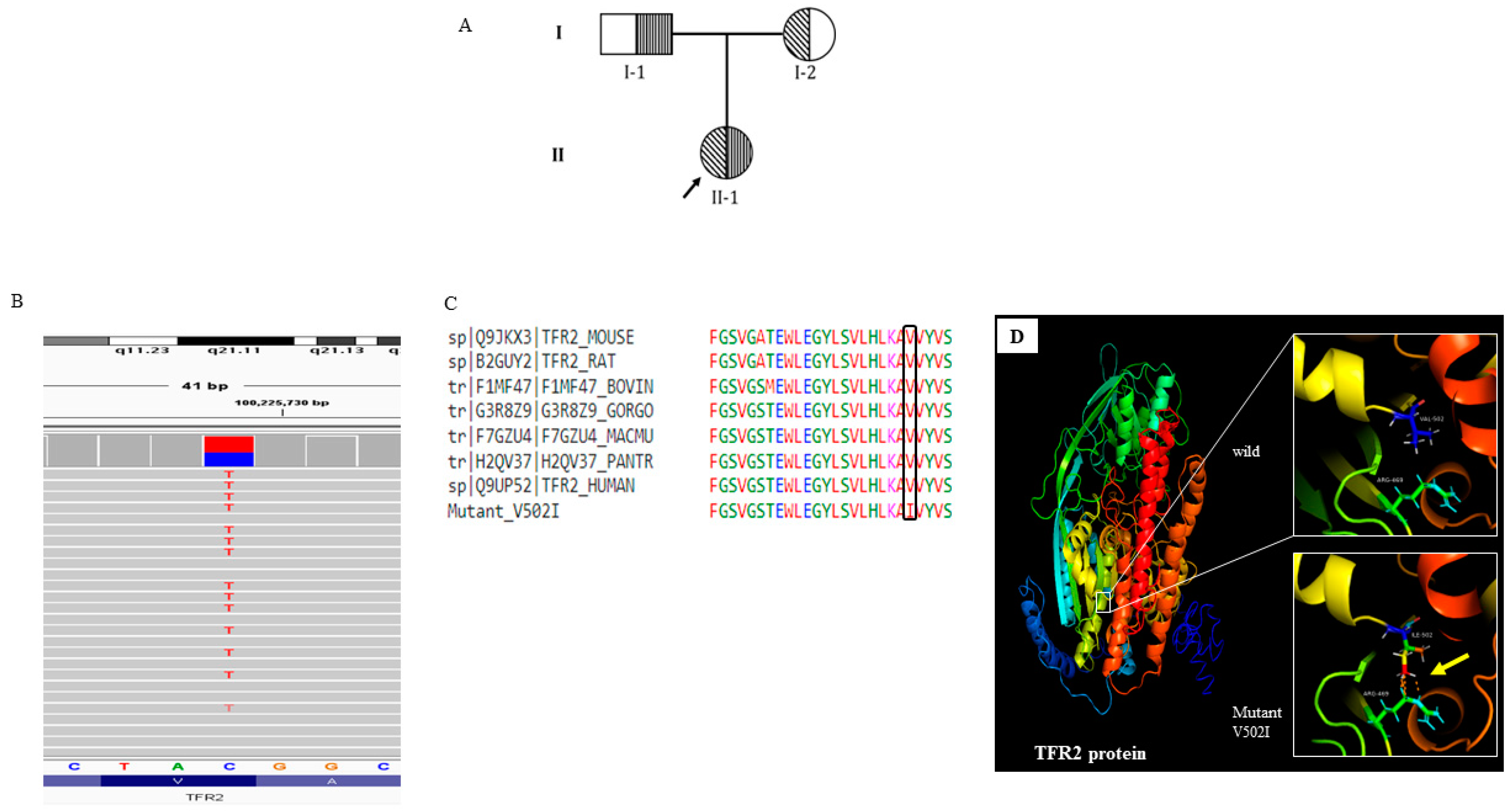

Subject 2, was presented the disease at 14 years of age with anaemia during regular blood test (

Figure 2A). She did not take any transfusion for the last 16 years and maintained a steady state hemoglobin level of 8g/dl. She had a splenomegaly of 6 cm from the left costal margin. (

Table 1). The sanger sequencing of the

HBB gene of this subject also confirms the β thalassemia disease with [IVS1-5(G>C) and CD26(G>A)]. Both the parents are found to be carrier for β thalassemia. She representing as a non-severe thalassemia subject.

We performed trio based extended whole exome sequencing (WES) of six subjects, two index cases as well as, father, mother of each one. For WES, DNA from the peripheral blood was extracted from the subjects. Agilent Sure select XT Human all Exome V6+UTR kit (Agilent, USA) was used for library preparation. Sequence run was performed in Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. The sequence data was aligned using human reference genome, hg19 and variant calling file (VCF) was generated and annotated with VarAFT tool5. To find out the significant genetic variants we perform both de novo variant and inherited variants searching (Supplementary Fig-1, Supplementary Fig-2). Among the total variants, only the non-synonymous, exonic, splice site, indel, stop-gain, stop-loss variants were considered. Variants were further filtered MAF < 0.01as per 1000genome data base6. Variants with damaging prediction, either by SIFT, PolyPhen2, and Mutation tester were retained. These variants were compared between both severe and non-severe patient and only unique variants in both patients were further selected, as per the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) 20157. Only the uncertain significant, pathogenic, and likely pathogenic variants were considered for further functional prediction /structural analysis. Function and disease association of each gene of respective variants were obtained from exhaustive literature survey as well as the public database, Gene Cards8 and OMIM9. The impact of the variants on the gene product were predicted using SOPMA10 and I-Mutant 2.011 tools. The tertiary protein structure were obtained from RSCB PDB database12. The 3D stricture were generated by I-TASSER13,14. To compare the alteration between wild and mutant proteins, PyMol was used15. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal Omega16 tools to examine the sequence conservativeness of the translated protein sequence.

Result and Discussion

In case of severe subject (Subject 1), we identified 4 significant inherited variants. We don’t find any significant de novo variants in this study

The identified 4 inherited variants in the severe subject are of in gene

RHAG (rs553258732),

TTLL4 (rs116116034),

ATOH8 (rs558361422),

P2RX7 (rs28360447) (Fig;1.B-E). All the variants were disease causing and present in the conserved region (

Figure 1 F-I) We further check the protein level changes of these variants using the bioinformatic tools and found that all the variants were significantly changes in the protein secondary.

structure and stability (

Table 2). The tertiary structure of the altered protein was also significantly changes (

Figure 1.J-M).

RHAG encodes the rhesus associated glycoprotein. Mutated RhAG leads to Overhydrated hereditary Stomatocytosis (OHST). Previously, it was reported that reduced or null expression of RhAG is associated with osmotically fragile erythrocyte and exhibit cation leak which leads to mild to moderate macrocytic hemolytic anemia17.

TTLL4 is a member of the tubulin ligase like family protein and abundantly expressed in the hematopoietic tissue of bone marrow and maintains the structural organization of RBC cytoskeleton18. A recent study reported that TTLL4 knock out mice have greater average diameter of RBCs than that of the wild type and showed greater vulnerability to oxidative stress leading to erythrolysis19. Mutation in these 2 major membrane proteins might destabilize the structural integrity of RBC membrane, making it much more fragile which can lead to hemolysis thus exacerbating anaemic state and enforcing severe condition.

ATOH8 gene, is a positive regulator of hepcidin transcription in the liver, which maintains iron homeostasis through regulating its own synthesis20. It has been reported that, hepcidin and ATOH8 expressions are downregulated in β thalassemia mice21. Mutation in this gene may causes the iron overload in the subject. Further evaluation reports that liver iron concentration is 6.1 mg/g in dry tissue in this subject, which is far more than the normal level.

P2RX7 is an ATP gated cation channel, previously it has been reported that, P2RX7 mediates ROS production in mature RBCs22. Mutation in the P2RX7 gene may lead to various consequences that disrupt cellular homeostasis, and may induce severe phenotype.

In case 2 (Non -sever subject), only single inherited variant in the gene

TFR2 (rs150618729) was identified. (

Figure 2. B; Supplementary table-2). Protein modelling confirms the tertiary structure changes (

Figure 2.).

TFR2 encodes a transmembrane glycoprotein of transferrin receptor like family, which regulate iron homeostasis

23. A recent study reported that,

TFR2 knockout β thalassemia mice sustained amelioration of anemia through improvement of the RBC count. Haploinsufficiency of TFR2 triggers erythroid cells to became more susceptible to erythropoietin (EPO) stimulation which helps erythropoiesis and improved anemic condition

24. Thus this variant may help in the non-severe subject as better clinical outcome.

In the present whole exome based pilot study, it has been addressed the phenotype mystery or extreme clinical variability with same globin genotype (Beta globin, as well as alpha globin). We have sequenced the parental members of the index cases, anticipating the effect of any sporadic mutation for this clinical mystery. But didn’t get any responsible variants out of sporadic mutation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in the world, explaining diverse clinical presentation of thalassemia with same globin mutations. From our study, it has been hypothesized that if the patient co associated with severe mutation in the gene/s responsible for RBC membrane, cytoskeleton formation, iron homeostatic, ROS generations, may be presented with severe clinical outcome, having beta globin genotype β +/ β 0 genotype.

In conclusion, hypothesis generated out of this study need to be validated, through the multi-omics study with large sample number. Generally, β 0/ β 0 genotype, would be severe clinical outcome, by the loss of two beta globin allele for β o mutation, but β +/ β 0, would have non -severe type. Thus, clue of the present study can helps to formulate suppurative therapy for β +/ β 0 thalassemia of severe subjects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Authorship

DS and DP performed the data collection, analysis prepared the initial version of manuscript, PKC did the patient management, KN and GS did the clinical confirmation, SB did data collection. AB did the overall planning and data validation and finalizing the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Department of Biotechnology, Govt of India for funding this work [Sanc.No-BT/PR26461/MED/12/821/2018]. Authors are also express due acknowledgment to National Institute of Biomedical Genomics (NIBMG), Kalyani for providing necessary WES work.

References

- Giardine B, Borg J, Viennas E, et al. Updates of the HbVar database of human hemoglobin variants and thalassemia mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jan;42(Database issue):D1063-9. [CrossRef]

- Sharma V, Kumar B, Kumar G, et al. Alpha globin gene numbers: an important modifier of HbE/beta thalassemia. Hematology.2009;14(5):297-300. [CrossRef]

- Saha D, Chowdhury PK, Panja A, et al. Effect of deletions in the α-globin gene on the phenotype severity of β-thalassemiaassemia. Hemoglobin. 2022;46(2):118-123. [CrossRef]

- Perera S, Allen A, Silva I, et al Genotype-phenotype association analysis identifies the role of α globin genes in modulating disease severity of β thalassaemia intermedia in Sri Lanka. Sci Rep. 2019 Jul; 12;9(1):10116. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Pierre Desvignes, Marc Bartoli, Valérie Delague, et al. VarAFT: a variant annotation and filtration system for human next generation sequencing data, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 46, Issue W1, 2 July 2018, Pages W545–W553. [CrossRef]

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68-74. [CrossRef]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015 May;17(5):405-24. [CrossRef]

- Stelzer G, Rosen N, Plaschkes I, et al. The GeneCards Suite: From Gene Data Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2016;54:1.30.1-1.30.33. Published 2016 Jun 20. [CrossRef]

- Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database issue): D514-D517. [CrossRef]

- Geourjon C, Deléage G. SOPMA: significant improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by consensus prediction from multiple alignments. Comput Appl Biosci. 1995 Dec;11(6):681-4. [CrossRef]

- Capriotti E, Fariselli P, Casadio R. I-Mutant2.0: predicting stability changes upon mutation from the protein sequence or structure. Nucleic Acids Res.2005 Jul 1;33(Web Server issue):W306-10. [CrossRef]

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235-242. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinform 2008; 9(40). [CrossRef]

- The UniProt Consortium, UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 49, Issue D1, 8 January 2021, Pages D480–D489. [CrossRef]

- PyMOL: The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC. Web site. http://www.pymol.org.

- ievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, et al. and Higgins D.G. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011; 7:539. [CrossRef]

- Jamwal M, Aggarwal A, Sachdeva MUS, et al. Overhydrated stomatocytosis associated with a complex RHAG genotype including a novel de novo mutation. J Clin Pathol. 2018; 71(7):648-652. [CrossRef]

- Ijaz F, Hatanaka Y, Hatanaka T, et al. Proper cytoskeletal architecture beneath the plasma membrane of red blood cells requires Ttll4. Mol Biol Cell. 2017 Feb 15;28(4):535-544. [CrossRef]

- Ijaz F, Hatanaka Y, Hatanaka T, et al. Proper cytoskeletal architecture beneath the plasma membrane of red blood cells requires Ttll4. Mol Biol Cell. 2017 Feb 15;28(4):535-544. [CrossRef]

- Park CH, Valore EV, Waring AJ, Ganz T. Hepcidin, a urinary antimicrobial peptide synthesized in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2001 Mar 16;276(11):7806-10. [CrossRef]

- Upanan S, McKie AT, Latunde-Dada GO, et al. Hepcidin suppression in β-thalassemiaassemia is associated with the down-regulation of atonal homolog 8. Int J Hematol. 2017 Aug;106(2):196-205. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Sluyter R. P2X7 receptor activation induces reactive oxygen species formation in erythroid cells. Purinergic Signal. 2013 Mar;9(1):101-12. [CrossRef]

- Silvestri L, Nai A, Pagani A, Camaschella C. The extrahepatic role of TFR2 in iron homeostasis. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:93. Published 2014 May 7. [CrossRef]

- Artuso I, Lidonnici MR, Altamura S, et al. Transferrin receptor 2 is a potential novel therapeutic target for β-thalassemiaassemia: evidence from a murine model [published correction appears in Blood. 2019 Jul 4;134(1):94]. Blood. 2018;132(21):2286-2297. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).