Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

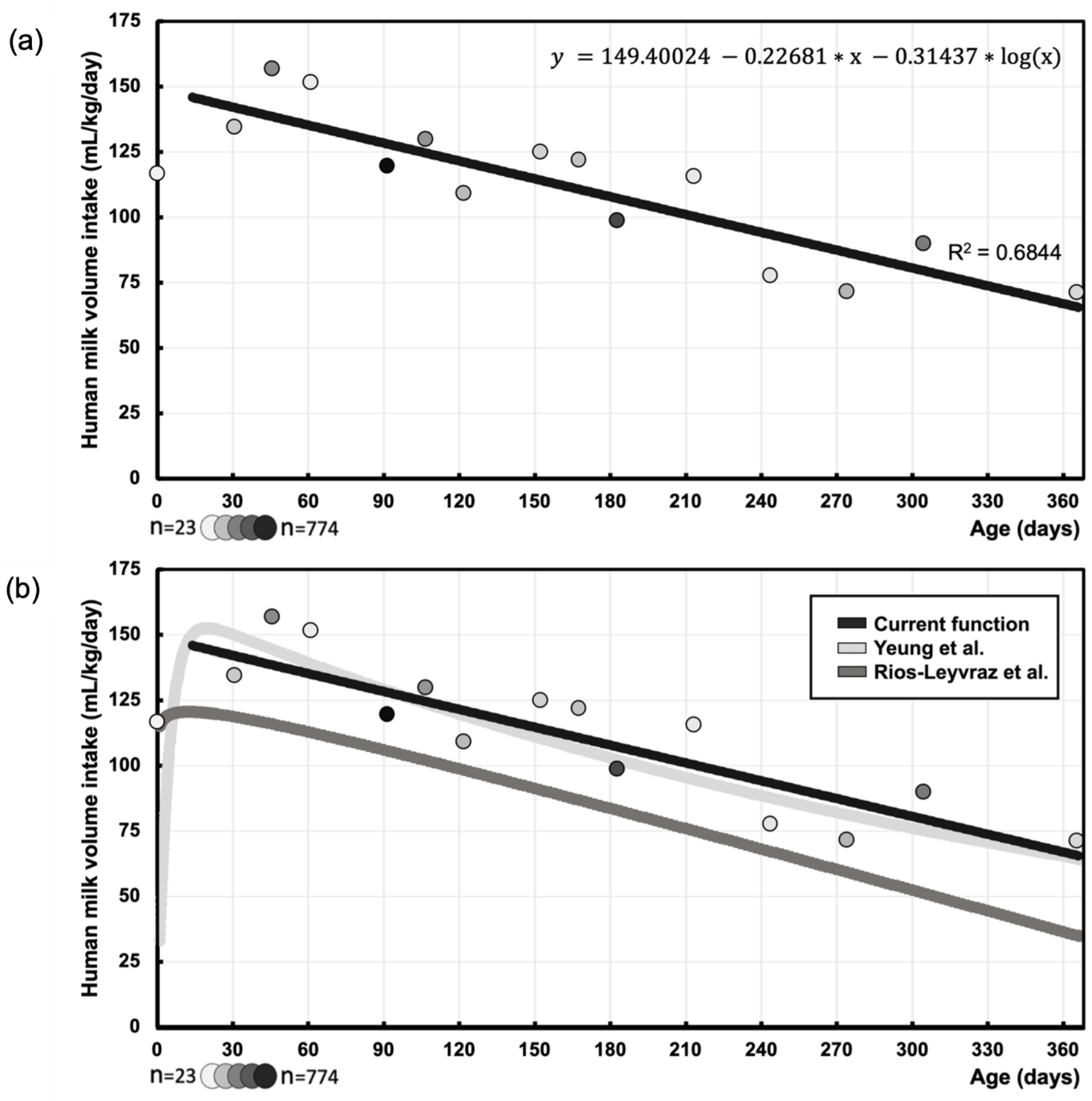

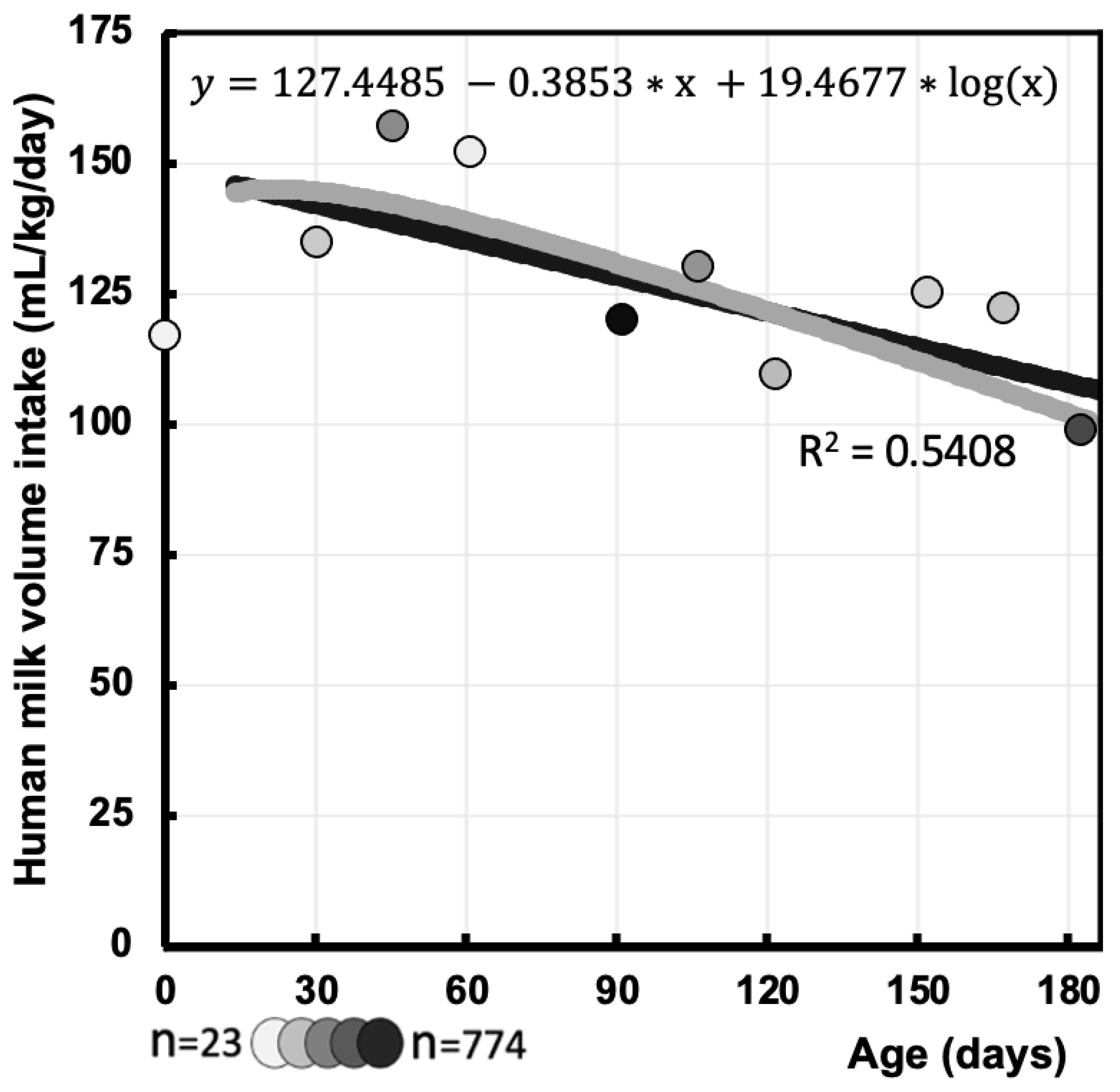

Background: Global health organizations recommend breastfeeding, but maternal pharmacotherapy can disrupt this due to safety concerns. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models predict medication transfer through breastfeeding, relying on validated milk intake volume data. However, literature mainly focused on different measurement methods, or such intake data were collected without systematic review. This systematic review therefore aims to gather data on human milk intake volume derived using the (dose-to-the-mother) deuterium oxide dilution method, allowing comparison with literature. Additionally, it aims to explore effects of maternal conditions on milk intake volume. Methods: PubMed, Embase, Web of science, Cochrane library, Scopus and CINAHL were searched for studies on the dilution method and breastfeeding in healthy infants. Risk of Bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and the Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) tool. Data on mean human milk intake volume were extracted and synthesized (mL/day and mL/kg/day) throughout infancy. Results: Sixty studies (34 countries) reported on milk intake volume of 5502 infants. This intake was best described by logarithmic regression y(mL/kg/day) = 149.4002 -0.2268*x -0.1365*log(x) (x=postnatal age, days). Maternal conditions showed no significant influence on human milk intake, except for maternal smoking (reduction). Conclusion: This function corresponds with previous literature, particularly between 1.5 to 12 months. Limited availability of early infancy data underscores the need for additional data in future PBPK modelling to enhance informed healthcare decisions and improved outcomes for mother and infant.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

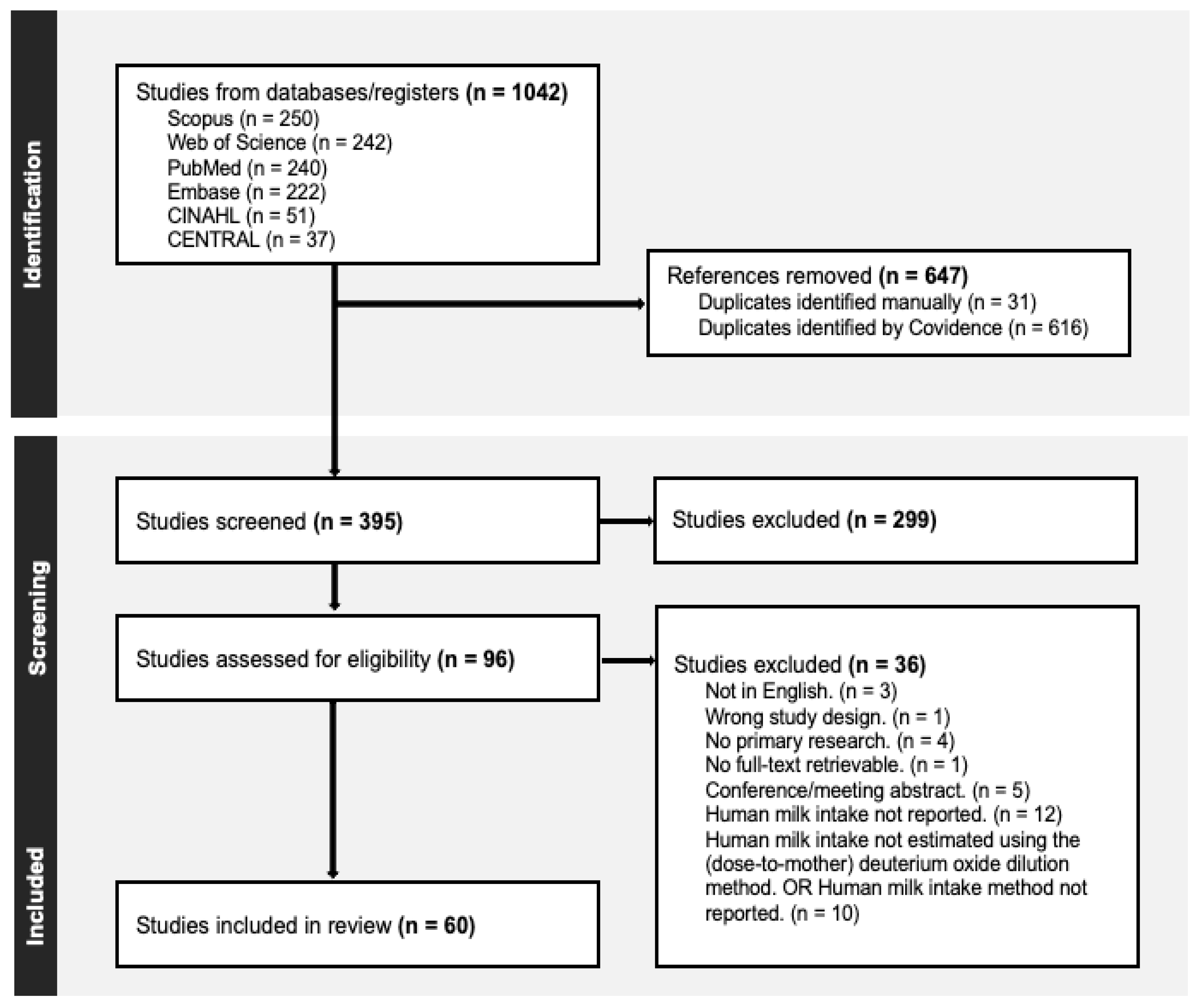

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Screening Process and Quality Assessment

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

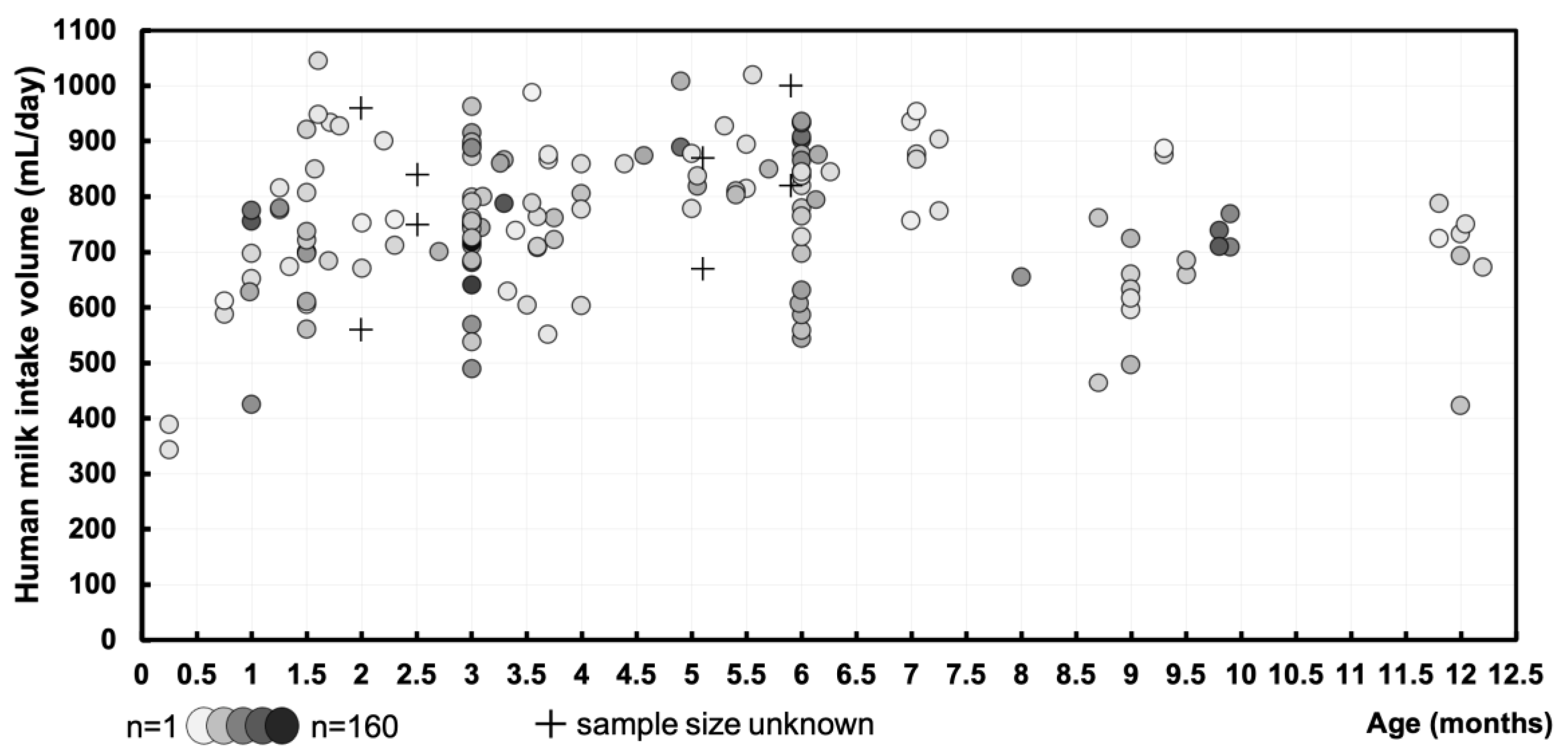

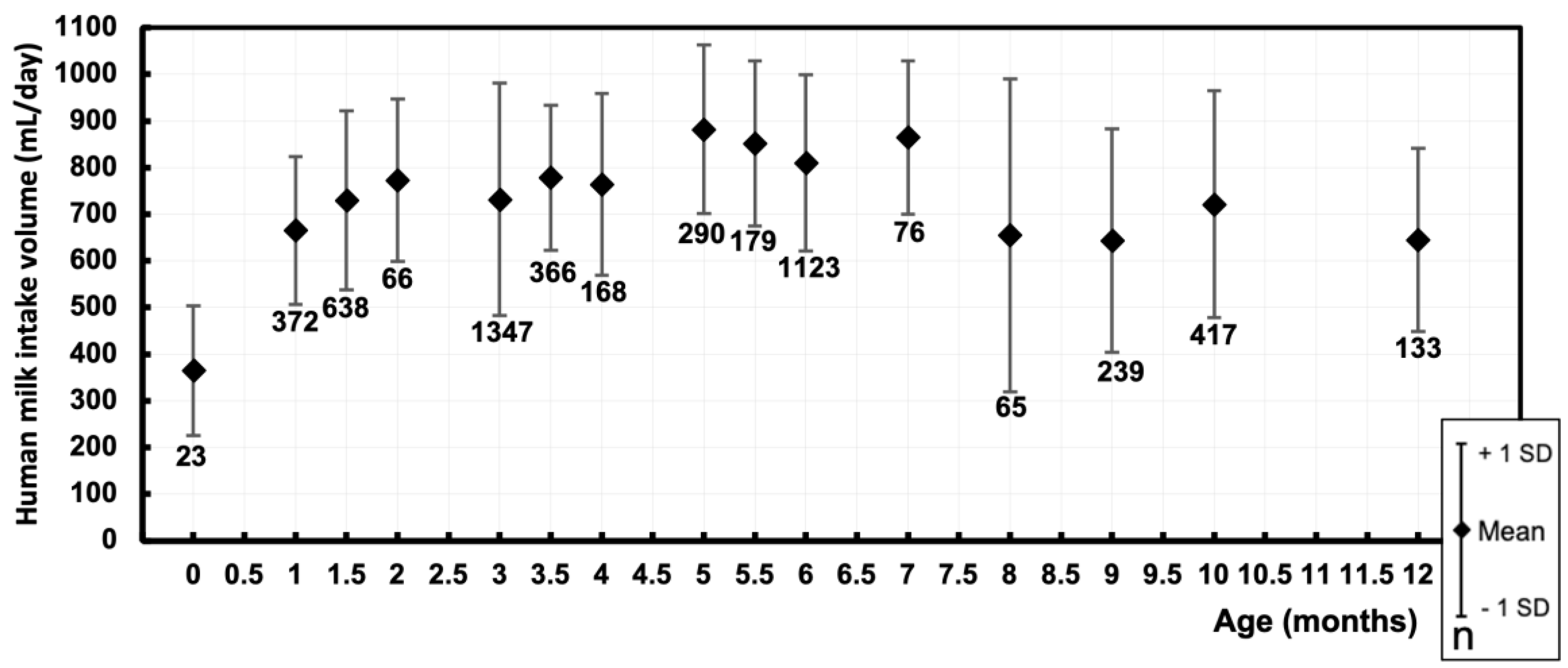

3.1. Human Milk Intake Volume – mL/day

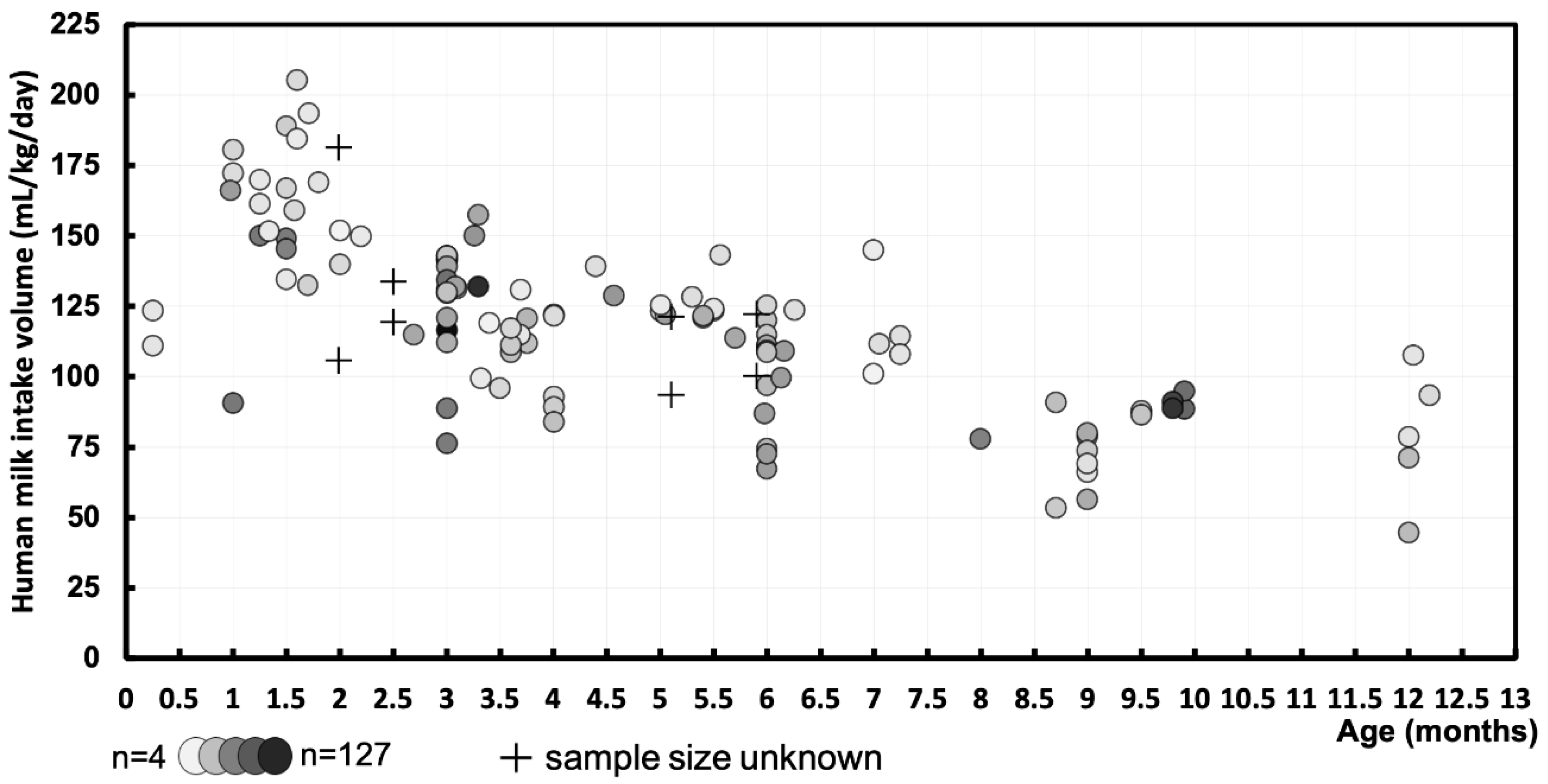

3.2. Human Milk Intake Volume – mL/kg/day

3.2. Function of Human Milk Intake Volume (mL/kg/day) Over Postnatal Age (days)

3.3. Human Milk Intake Volume Function (mL/kg/day) During First 6 Months

3.4. Maternal Conditions and Interventions Effects on Human Milk Intake Volume

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. Infant and young child feeding: WHO; 2021 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding.

- Fan D, Xia Q, Lin D, Ma Y, Rao J, Liu L, et al. Role of breastfeeding on maternal and childhood cancers: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. J Glob Health. 2023;13:04067. [CrossRef]

- Odom EC, Li R, Scanlon KS, Perrine CG, Grummer-Strawn L. Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e726-32. [CrossRef]

- Della-Giustina K, Chow G. Medications in pregnancy and lactation. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21(3):585-613. [CrossRef]

- Nauwelaerts N, Deferm N, Smits A, Bernardini C, Lammens B, Gandia P, et al. A comprehensive review on non-clinical methods to study transfer of medication into breast milk - A contribution from the ConcePTION project. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;136:111038. [CrossRef]

- Smits A, De Cock P, Vermeulen A, Allegaert K. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling and simulation in neonatal drug development: how clinicians can contribute. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(1):25-34. [CrossRef]

- Yeung CHT, Fong S, Malik PRV, Edginton AN. Quantifying breast milk intake by term and preterm infants for input into paediatric physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16(2):e12938. [CrossRef]

- Agency IAE. IAEA human health series No. 7. Stable Isotope Technique to Assess Intake of Human Milk in Breastfed Infants. Vienna, 2010.

- Torabinia M, Rosenblatt SD, Mosadegh B. A Review of Quantitative Instruments for Understanding Breastfeeding Dynamics. Glob Chall. 2021;5(10):2100019. [CrossRef]

- Meier PP, Engstrom JL. Test weighing for term and premature infants is an accurate procedure. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92(2):F155-6. [CrossRef]

- Savenije OE, Brand PL. Accuracy and precision of test weighing to assess milk intake in newborn infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91(5):F330-2.

- Nancy F. Butte MGL-A, Cutberto Garza. Nutrient adequacy of exclusive breastfeeding for the term infant during the first six months of life. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002.

- da Costa TH, Haisma H, Wells JC, Mander AP, Whitehead RG, Bluck LJ. How much human milk do infants consume? Data from 12 countries using a standardized stable isotope methodology. J Nutr. 2010;140(12):2227-32. [CrossRef]

- Rios-Leyvraz M, Yao Q. The Volume of Breast Milk Intake in Infants and Young Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breastfeed Med. 2023;18(3):188-97. [CrossRef]

- Martje Van Neste KA, Lucas Cloostermans. The deuterium oxide dilution method for estimating breast milk volume intake of the infant: a systematic review: PROSPERO; 2022 [CRD42022380374]. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022380374.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software Australia2023 [Available from: www.covidence.org.

- Kenniscentrum voor de Gezondheidszorg Gent. Newcastle - Ottawa quality assessment scale [Available from: https://www.kcgg.ugent.be/pdf/NEWCASTLE-OTTAWA_QUALITY_ASSESSMENT_SCALE.pdf.

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj. 2019;366:l4898.

- Salkind NJ. Encyclopedia of Research Design. United kingdom SAGE Publications; 2010.

- Warner RM. Applied Statistics II: Multivariable and Multivariate Techniques. United states SAGE Publications; 2020.

- collaboration. Tc. Obtaining standard deviations from standard errors and confidence intervals for group means 2011 [6 february 2024]. Available from: https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_7/7_7_3_2_obtaining_standard_deviations_from_standard_errors_and.htm#:~:text=The%20standard%20deviation%20for%20each,should%20be%20replaced%20by%205.15.

- Palmer. M. Propagation of Uncertainty through Mathematical Operations: massecuite institute of technology [Available from: https://web.mit.edu/fluids-modules/www/exper_techniques/2.Propagation_of_Uncertaint.pdf.

- Islam MM, Brown KH. Zinc transferred through breast milk does not differ between appropriate- and small-for-gestational-age, predominantly breast-fed Bangladeshi infants. Journal of Nutrition. 2014;144(5):771-6. [CrossRef]

- Caire-Juvera G, Casanueva E, Bolaños-Villar AV, De Regil LM, De la Barca AMC. No changes in weight and body fat in lactating adolescent and adult women from Mexico. American Journal of Human Biology. 2012;24(4):425-31. [CrossRef]

- Leong C, Gibson RS, Diana A, Haszard JJ, Rahmannia S, Ansari MB, et al. Differences in Micronutrient Intakes of Exclusive and Partially Breastfed Indonesian Infants from Resource-Poor Households are Not Accompanied by Differences in Micronutrient Status, Morbidity, or Growth. Journal of Nutrition. 2021;151(3):705-15. [CrossRef]

- Mulol H, Coutsoudis A. Breastmilk Output in a Disadvantaged Community with High HIV Prevalence as Determined by the Deuterium Oxide Dose-to-Mother Technique. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2016;11(2):64-9. [CrossRef]

- Oiye S, Mwanda W, Filteau S, Owino V. HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Western Kenyan Women Produce Equivalent Amounts of Breast Milk at 6 Wk and 6 Mo Postpartum: A Prospective Cohort Study Using Deuterium Oxide Dose-to-Mother Technique. The Journal of nutrition. 2023;153(1):27-33. [CrossRef]

- Rahman A, Hafeez A, Bilal R, Sikander S, Malik A, Minhas F, et al. The impact of perinatal depression on exclusive breastfeeding: a cohort study. Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2016;12(3):452-62. [CrossRef]

- Vio F, Salazar G, Infante C. Smoking during pregnancy and lactation and its effects on breast-milk volume. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1991;54(6):1011-6. [CrossRef]

- Mofid LS, Casapía M, Montresor A, Rahme E, Marquis GS, Vercruysse J, et al. Maternal postpartum deworming and infant milk intake: Secondary outcomes from a trial. Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2021;17(4). [CrossRef]

- Saint L, Smith M, Hartmann PE. The yield and nutrient content of colostrum and milk of women from giving birth to 1 month post-partum. Br J Nutr. 1984;52(1):87-95. [CrossRef]

- Santoro W, Jr., Martinez FE, Ricco RG, Jorge SM. Colostrum ingested during the first day of life by exclusively breastfed healthy newborn infants. J Pediatr. 2010;156(1):29-32. [CrossRef]

- Bandara T, Wong WW. Quantification of human milk intake of the babies. SriLanka J Child Health. 2022;51(4):608-12. [CrossRef]

- Braga GC, Ferriolli E, Quintana SM, Ferriani RA, Pfrimer K, Vieira CS. Immediate postpartum initiation of etonogestrel-releasing implant: A randomized controlled trial on breastfeeding impact. Contraception. 2015;92(6):536-42. [CrossRef]

- Van Neste M, Bogaerts A, Nauwelaerts N, Macente J, Smits A, Annaert P, et al. Challenges Related to Acquisition of Physiological Data for Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Models in Postpartum, Lactating Women and Breastfed Infants-A Contribution from the ConcePTION Project. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(11). [CrossRef]

- Agne-Djigo A, Kwadjode KM, Idohou-Dossou N, Diouf A, Guiro AT, Wade S. Energy intake from human milk covers the requirement of 6-month-old Senegalese exclusively breast-fed infants. Br J Nutr. 2013;110(10):1849-55. [CrossRef]

- Haisma H, Coward WA, Albernaz E, Visser GH, Wells JCK, Wright A, et al. Breast milk and energy intake in exclusively, predominantly, and partially breast-fed infants. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;57(12):1633-42. [CrossRef]

- Mazariegos M, Slater C, Ramirez-Zea M. Validity of Guatemalan Mother’s Self-Reported Breast-Feeding Practices of 3-Month-Old Infants. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2016;37(4):494-503. [CrossRef]

- Wells JC, Jonsdottir OH, Hibberd PL, Fewtrell MS, Thorsdottir I, Eaton S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of 4 compared with 6 mo of exclusive breastfeeding in Iceland: differences in breast-milk intake by stable-isotope probe. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(1):73-9. [CrossRef]

- Arthur PG, Hartmann PE, Smith M. Measurement of the milk intake of breast-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6(5):758-63.

- Toh JY, Yip G, Han WM, Fok D, Low YL, Lee YS, et al. Infant Feeding Practices in a Multi-Ethnic Asian Cohort: The GUSTO Study. Nutrients. 2016;8(5). [CrossRef]

- Zong Xn, Wu H, Zhao M, Magnussen CG, Xi B. Global prevalence of WHO infant feeding practices in 57 LMICs in 2010–2018 and time trends since 2000 for 44 LMICs. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;37.

| Postnatal age (months) | Pooled sample size (n) | Pooled mean (mL/day) | Pooled SD (mL/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 [0.01 – 0.49] | 23 | 364.9 | 139 |

| 1 [0.50 – 1.24] | 372 | 665.6 | 158.3 |

| 1.5 [1.25 – 1.74] | 638 | 729.9 | 191.9 |

| 2 [1.75 – 2.49] | 66 | 773.4 | 174.4 |

| 3 [2.50 – 3.24] | 1347 | 732 | 249.4 |

| 3.5 [3.25 – 3.74] | 366 | 778.6 | 155.2 |

| 4 [3.75 – 4.49] | 168 | 764.7 | 194.8 |

| 5 [4.50 – 5.24] | 290 | 882.4 | 181 |

| 5.5 [5.25 – 5.74] | 179 | 852.5 | 177 |

| 6 [5.75 – 6.49] | 1123 | 809.9 | 189 |

| 7 [6.50 – 7.49] | 76 | 864.8 | 164.9 |

| 8 [7.50 – 8.49] | 65 | 655 | 336 |

| 9 [8.50 – 9.49] | 239 | 643.5 | 239.2 |

| 10 [9.50 – 10.49] | 417 | 721.7 | 243 |

| 12 [11.50 – 12.49] | 133 | 645 | 197 |

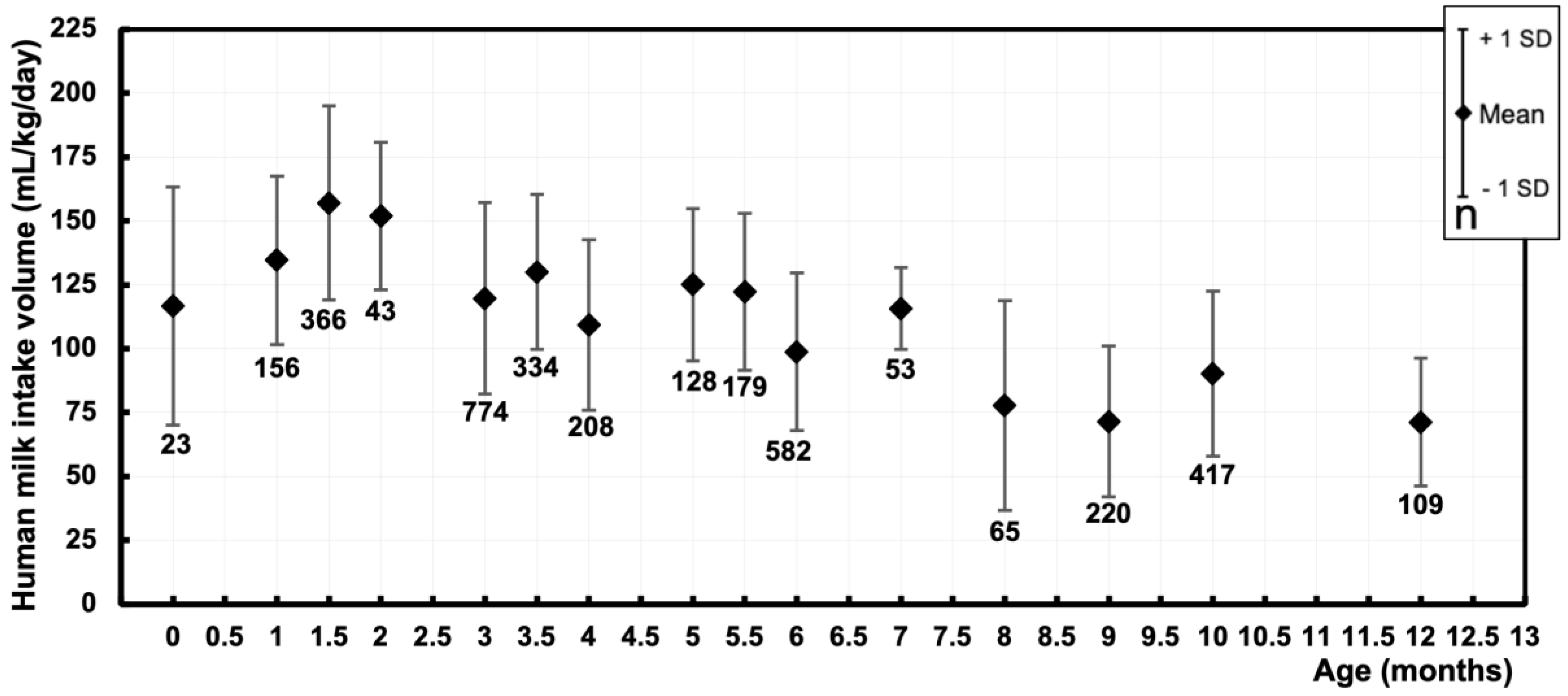

| Postnatal age (months) | Pooled sample size | Pooled mean (mL/kg/day) | Pooled SD (mL/kg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 [0.01 – 0.49] | 23 | 116.8 | 46.6 |

| 1 [0.50 – 1.24] | 156 | 134.6 | 32.9 |

| 1.5 [1.25 – 1.74] | 366 | 157 | 38 |

| 2 [1.75 – 2.49] | 43 | 151.9 | 28.9 |

| 3 [2.50 – 3.24] | 774 | 119.7 | 37.3 |

| 3.5 [3.25 – 3.74] | 334 | 130.1 | 30.3 |

| 4 [3.75 – 4.49] | 208 | 109.4 | 33.4 |

| 5 [4.50 – 5.24] | 128 | 122.2 | 30.7 |

| 5.5 [5.25 – 5.74] | 179 | 122.2 | 30.7 |

| 6 [5.75 – 6.49] | 582 | 98.8 | 30.8 |

| 7 [6.50 – 7.49] | 53 | 115.8 | 16 |

| 8 [7.50 – 8.49] | 65 | 77.8 | 41 |

| 9 [8.50 – 9.49] | 220 | 71.5 | 29.5 |

| 10 [9.50 – 10.49] | 417 | 90.2 | 32.3 |

| 12 [11.50 – 12.49] | 109 | 71.2 | 25 |

| Author | Year | Postnatal age | Sample size | Maternal conditions |

Human milk intake volume |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulol et al. [27] | 2016 | 6 weeks | 21 | HIV positive | 831 ± 185 g/day | 0.06 |

| 24 | HIV negative | 948 ± 223 g/day | ||||

| 3 months | 28 | HIV positive | 899 ± 188 g/day | 0.61 | ||

| 45 | HIV negative | 925 ± 227 g/day | ||||

| 6 months | 27 | HIV positive | 871 ± 293 g/day | 0.66 | ||

| 45 | HIV negative | 902 ± 286 g/day | ||||

| 9 months | 24 | HIV positive | 679 ± 281 g/day | 0.33 | ||

| 43 | HIV negative | 746 ± 263 g/day | ||||

| 12 months | 13 | HIV positive | 755 ± 287 g/day | 0.64 | ||

| 33 | HIV negative | 713 ± 264 g/day | ||||

| Oiye et al. [28] |

2023 | 6 weeks | 68 | HIV positive | 721 ± 111 g/day | 0.88 |

| 65 | HIV negative | 719 ± 121 g/day | ||||

| 6 months | 60 | HIV positive | 960 ± 121 g/day | 0.91 | ||

| 62 | HIV negative | 963 ± 107 g/day | ||||

| Rahman et al. [29] | 2016 | 4 months | 24 | Depressed | 89.3 ± 38.1 mL/kg/day | 0.57 |

| 31 | Not depressed | 83.9 ± 29.0 mL/kg/day | ||||

| Vio et al. [30] | 1991 | 41 ± 6.7 days | 10 | Smoking | 693 ± 110 g/day | <0.0001 |

| 52 ± 14 days | 10 | Not smoking | 961 ± 120 g/day | |||

| Mofid et al. [31] | 2021 | 1 months |

109 | Albendazole | 756 ± 167 mL/day* | 0.471 |

| 90 | Placebo | 774 ± 170.8 mL/day* | ||||

| 6 months |

107 | Albendazole | 903 ± 165.5 mL/day* | 0.849 | ||

| 93 | Placebo | 908 ± 173.6 mL/day* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).