1. Introduction

Bladder cancers (BC) are highly immunogenic and diverse, with 70-75% of cases presenting with recurrent non-muscle-invasive BC (NMIBC) and 25-30% with aggressive/advanced muscle-invasive BC (MIBC) [

1,

2,

3]. Although little is still known of how immune cells respond, immunotherapy with the bacille Calmette–Guerin (BCG) remains the gold standard for carcinoma in situ (CIS) and high-risk NMIBC. In addition, immunotherapy (IT) to block cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoints and to boost natural immune vigilance is emerging as an effective therapy in MIBC [

4,

5]. Although BCG is a potent enhancer of the immune response, only 50 to 70% of patients respond to this treatment. Therefore, understanding the immunological mechanisms could contribute to improve the results [

6]. Intravesical BCG triggers the cellular immune response, leading to the infiltration of granulocytes, macrophages, NK cells, dendritic cells and lymphocytes into the tumor. Once in there, they secrete IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF-α, GMCSF and sICAM-1, thus contributing to propagate inflammation and induce apoptosis of BC cells. Dendritic cells present tumor antigens to T lymphocytes, triggering their activation and anti-tumor response. Besides, BCG stimulates cancer cell killing through cytotoxic T and NK cells [

3].

In vitro and experimental models suggest that NK cells play important roles in BCG therapy [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Effector mechanisms of NK cells are regulated by a balance of activating and inhibitory receptors interacting with their ligands on cancer cells [

13]. Depending on the killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) genotype, each individual may express varying numbers of 9 inhibitory (KIR2DL1-4, KIR2DL5a/b and KIR3DL1-3) or 6 activating (KIR2DL1-5 and KIR3DS1) receptors. Licensing interactions of inhibitory KIR and NKG2A receptors with their HLA class-I (HLA-I) ligands promote education and full competence of NK cells [

14,

15,

16,

17,

13]. NK cell licensing is associated with: 1) increased expression of CD226 [

18,

19]; 2) enhanced glycolysis [

20]; and 3) lysosomal remodeling [

21]. Licensing allows NK cells to discriminate healthy tissues from tissues expressing damage/danger signs, loss of HLA-I (“missing-self”) [

22,

23], or alterations in the peptidome presented by HLA-I (“altered-self”) [

24,

25].

The best-characterized licensing interactions are KIR2DL1/HLA-C2 (Lys80), KIR2DL2-3/HLA-C1 (Asn80), KIR3DL1/Bw4, KIR3DL2/HLA-A3, A11 alleles, KIR2DL4/HLA-G [

13], and NKG2A/HLA-E [

26]. HLA-E specifically binds nonapeptides from the leader sequence of HLA-I (residues -22 to -14) with a dimorphism at position -21 [

27,

28]. Methionine -21 (-21M), present in all HLA-A and HLA-C and in a minority of HLA-B allotypes, provides a good anchor residue that facilitates the folding and cell-surface expression of HLA-E [

29]. In contrast, threonine -21 (-21T), present in the majority of HLA-B allotypes, does not bind effectively to HLA-E. Genetic analysis of human populations worldwide shows how haplotypes with -21M rarely encode for the Bw4 or C2 ligands [

26,

30]; therefore, there are two fundamental HLA haplotypes: one preferentially supplying NKG2A ligands and the other supplying KIR ligands [

26]. Functional assays have shown that individuals with -21M haplotypes have NKG2A

+ NK cells which are better educated, phenotypically more diverse and functionally more potent than those of TT individuals [

26]. HLA-B -21M/T dimorphism has been associated with susceptibility to HIV infection [

31], killing of HIV-infected cells by NK cells [

32], NK cell anti-leukemic activity and overall survival of acute myeloid leukemia patients under IL-2 immunotherapy [

33].

However, in BC, elevated tumor expression of HLA-E is associated with increased disease progression [

34,

35,

36], revealing an inhibitory role of the NKG2A/HLA-E interaction, which has led to consider this interaction as a new check-point to be blocked with IT, and clinical trials are ongoing. The present work explores the role that NKG2A/HLA-E interaction may have on the antitumor response in BC treated with BCG or other therapies and its usefulness for optimizing personalized immunotherapies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Study Groups

This prospective observational study included 925 healthy Caucasian (HC) donors as a control group and 973 consecutive Caucasian cancer patients as an experimental group, including BC (n=325), melanoma (n=308), myeloma (n=150), pediatric acute leukemia (n=102) and ovarian cancer (n=88). BC tumors were classified according to the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs [

37] into: 1) noninvasive urothelial neoplasms (NIUN), including CIS as well as the low- and high-grade papillary carcinomas (Ta); and 2) infiltrating urothelial carcinoma (IUC), including the NMIBC T1-stage, and the MIBC T2, T3 and T4 stages. Progression was defined in NIUN as local recurrence with higher grade or stage, and in IUC, as local recurrence with higher stage and/or development of metastatic disease. Treatment and management were at the discretion of the urologists, based on the patient’s condition and tumor histology. In this study the recurrence, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were compared separately in patients treated with BCG from those treated with other therapies. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee. The Institutional Review Board (IRB-00005712) approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and controls in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Peripheral blood samples anticoagulated with EDTA (for HLA and KIR genotyping and expression analysis of NK cell receptor by flow cytometry) were obtained at diagnosis. Fresh sodium heparin blood samples were obtained from selected donors for proliferation and cytotoxicity, as well as for cytokine production assays.

2.2. HLA-A, -B and -C and KIR Genotyping

HLA-A, -B, -C, and KIR genotyping was performed on DNA samples extracted from peripheral blood using the QIAmp DNA Blood Mini kit (QIAgen, GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and Lifecodes HLA-SSO and KIR-SSO typing kits (Immucor Transplant Diagnostic, Inc. Stamford, CT. USA), as previously described [

38,

39]. HLA-A and HLA-B genotyping allowed us to identify alleles bearing the Bw4 motif according to the amino-acid sequences at positions 77–83 in the alpha1 domain of the HLA class-I heavy chain. Bw4 alleles with threonine at amino acid 80 (Thr80) and higher affinity for KIR3DL1 (HLA-B*05, B*13, B*44) were discerned from those with isoleucine 80 (Ile80) and lower affinity (HLA-A*23, A*24, A*25, A*32 and HLA-B*17, B*27, B*37, B*38, B*47, B*49, B*51, B*52, B*53, B*57, B*58, B*59, B*63 and B*77). HLA-C genotyping allowed the distinction between HLA-C alleles with asparagine 80 (C1-epitope: HLA-C*01, 03, 07, 08, 12, 14, 16:01) and those with lysine 80 (C2-epitope: HLA- C*02, *04, *05, *06, *15, *16:02, *17, *18). Nonetheless, the KIR ligand calculator at

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/imgt/hla/matching/ was used to ascertain Bw4, C1 and C2 epitopes. Dimorphism at position −21 of the leader sequence of HLA-B was also discriminated to distinguish allotypes with methionine (−21M, HLA-B*07, B*08, B*14, B*38, B*39, B*42, B*48, B*67, B*73 and B*81) from those with threonine (−21T, rest HLA-B alleles).

KIR genotyping identified inhibitory KIRs (2DL1-L3/2DL5 and 3DL1-L3) and activating KIRs (2DS1-S5 and 3DS1), as well as KIR2DL4, which has both inhibitory and activating potential [

40].

2.3. Expression of NK Cell Receptors in Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes

The expression of CD16, CD226 (DNAM1), NKG2A, TIGIT and KIR receptors (KIR2DL1, 2DS1, 2DL2/S2, 2DL3 and 3DL1) on CD56

bright and CD56

dim NK cells as well as on CD3

+CD4

+ and CD3

+CD8

+ T cells was analyzed simultaneously using an LSR-II or Lyric flow cytometer and DIVA Software (BD), following the method previously described [

41,

42]. The following monoclonal antibodies were used for peripheral blood labeling CD158a-FITC (143211, R&D Systems Inc, which recognized KIR2DL1), CD158a/h-PC7 (EB6B, Beckman Coulter, which recognized both KIR2DL1 and 2DS1), CD158b2 (180701, R&D Systems Inc, KIR2DL3), CD226-PE (11A8, Biolegend), CD158e1 (DX9, R&D systems, KIR3DL1), CD16-AlexaFluor700 (3G8, BD), CD8-APC-Cy7 (SK1, BD), TIGIT-BV421 (741182, BD), CD3-BV510 (UCHT1, BD), CD4-BV605 (RPA-T4, BD), CD56 BV711 (NCAM16.2, BD) and CD159a-BV786 (131411, BD). They were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Subsequently red cells were lysed, washed and acquired.

2.4. In Vitro Functional Assays

To evaluate the impact that the interaction of HLA-B -21M/T ligands had on the functionality of T and NK cells, such as the capacity to proliferate, kill tumor cell lines (K562, J82 y T24), and secrete cytokines, immunoefector functionality was evaluated on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated in ficoll density gradients from sodium heparin anticoagulated samples of 18 donors (6 donors MM, 3 MT and 9 TT genotypes). PBMCs were stained with 0.05 µM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and simulated in vitro with ImmunoCult™ Human CD3/CD28 T cell activator (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) following the manufacturer’s instructions or with BCG (Danish 1331, AJVaccines, Copenhagen) at a proportion of 1:1 colony forming units (CFU) to PBMC. CFSE-labeled cells (1x10ˆ6/well) were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator, in 24-well flat-bottomed plates in quintuplicate. After 72 hours 1 well per sample was collected and the supernatant was stored at -80°C and used for cytokine analysis in Luminex. After 144 hours, the harvested cells were either used for cytotoxic assays or stained to analyze proliferation in a Norther-light (NL) flow cytometer (Cytek, Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Cytokine production in culture supernatant was analyzed using a Procarta Plex Human Immune Monitoring 12 Plex Panel (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-23, IFN-γ, TNF-α and TGF-β1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vienna, Austria), following the manufacturer’s instructions, in a Luminex 300 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The analysis was performed using the ProcartaPlex Analysis App software (Thermo Fisher).

Cell proliferation was evaluated in CFSE labeled cells after 6 days of in vitro expansion by labeling with TIGIT-BV421 (RUO, BD), CD16-V450 (3G8, BD), CD4-cFV505 (DK3, Palex), CD226-BV605 (11A8, Biolegend), CD8-BV570 (RPA-T8, Biolegend), TIM-3-BV711 (7D3, BD), TCRgd-BV750 (11F2, BD), NKG2A-BV786 (131411, BD), HLA-DR-cFB548 (L2D3, Cytek), NKG2C-PE (REA205, Miltenyi Biotec), CD25-cFBYG610 (BC96, Cytek), CD158bj-PE-Cy5 (GL183, Beckman Culter), KIR3DL1-APC (DX9, R&D Systems Inc), CD57-cFR668 (HNK1, Cytek), CD38-cFR685 (HIT2, Cytek), CD3-AF700 (UCHT1, BD), NKG2D-APC-H7 (1D11, Biolegend) and CD45-cFR840 (HI30, Cytek) monoclonal antibodies during 15 min at room temperature. Cells were washed with FACsFlow (BD) and acquired in an NL-flow (Cytek) cytometer and analyzed in Diva software (BD). Proliferation was estimated as the percentage of CFSE-low cells within each cell subset (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, CD56

dim and CD56

bright NK cells and NoT-NoNK cells) as shown in

Figure 1A.

Cytotoxic activity of harvested cells (effectors) was evaluated against target cell lines stained with CellTrace

TMViolet (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at effector/target ratios 5:1 and 15:1 in triplicate. In parallel, target cells were incubated alone to measure basal cell death. Cells were incubated in V-bottom 96-well microplates in a total volume of 150 μL of complete medium for 4 h in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere at 37°C. Cell mixtures were then washed in PBS-1% BSA and incubated in the same buffer containing 20µg/mL 7-amino actinomycin D (7-AAD, Sigma, France) and 0.5 µg/mL DRAQ5 (BD, Canada) for 10 min at 4°C in the dark. Cells were then washed and acquired right afterwards on a FACSLyric flow cytometer. Mean value of triplicates was used to calculate the percentage of lysis as follows: experimental – spontaneous apoptotic target cells. Gatting strategy is shown in

Figure 1B.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were collected in Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA, USA) and analyzed using SPSS-21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square and analysis of variance/post hoc tests were used to analyze categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Kaplan-Meier and log-rank tests were used to analyze patient survival (PFS and OS). Time to events (progression or death) was estimated as months from the diagnosis date. Outcome of patient groups expressed in months were estimated as the 75-percentile-PFS (75p-PFS) or 75-percentile-OS (75p-OS). Cox regression was used for investigating the effect of multiple parameters on the OS. Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval were estimated. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bonferroni correction (pc) was applied when needed.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical, Biological, Therapeutic and Evolutionary Characteristics of the Study Groups

The study included 325 patients with BC, 150 with myeloma, 88 with ovarian cancer, 308 with melanoma and 105 with pediatric acute leukemia with a 75p-OS of 34.04±4.4, 35.0±5.5, and 18.0±2.9 years, respectively, and not reached for melanoma and pediatric acute leukemia (

Figure 2). For BC, 57 were NIUN (CIS or Ta), and the rest UIC, 149 T1, 99 T2 and 88 T3 or T4, with a 75p-OS of 120±27.2, 53.0±7.0, 14.0±3.6 and 14.0±2.9 years, respectively. BCG therapy was administered to 32 CIS+Ta cases (56.1%), 117 T1 cases (78.5%) and 2 T2 cases (2.0%). The 75p-OS for BCG and other therapies were 59.0±6.5 and 19.0±2.9 years, respectively. The age and sex of the study groups are shown in

Figure 2. Mean age of the HC group (n=925) was 52±0.7 years with a proportion of 44.5% males.

3.2. L3/C1 Was the Only Interaction Associated with Susceptibility of BC and Patient Outcome

We first assessed the role of NK cell receptor/ligand interactions in BC susceptibility (

Figure 3). KIR3DS1 gene, but not KIR3DS1/Bw4 interaction, showed higher frequency in BC patients treated with BCG or other treatments (50.7% and 47.5%, p=0.044) than in healthy controls (41.3%) or other cancers (40.3%); therefore, KIR3DS1 was associated with higher susceptibility to BC, although this molecule did not significantly impact disease progression or patient outcome.

HLA C1 ligands showed lower frequency in BC patients treated with BCG (70.0%, p=0.038) than in BC patients with other treatments (81.5%), in other cancers (80.0%) or in healthy controls (84.4%); therefore, C1 ligands were associated with lower susceptibility to low stages of BC, although this molecule did not significantly impact disease progression or patient outcome.

KIR2DL3/C1 was the only interaction that showed lower frequency in BC patients treated with BCG (61.8%, p<0.001) than in healthy controls (75.8%), in BC patients treated with other therapies (68.9%) and in other cancers (70.2%); therefore, KIR2DL3/C1 interaction appeared to protect from low-stage BC. Besides, although BC patients with KIR2DL3/C1 interaction treated with BCG did not show differences in the progression-free survival curves, they showed longer 75p-OS than those without this interaction (71.0±12.0 vs. 56.0±11.0 months, p=0.031).

3.3. HLA-B -21M/T Genotype is an Independent Predictive Parameter of the Progression-Free and Overall Survival of BC Treated with BCG

Next, the role of the HLA-B -21M/T genotype was evaluated in the progression of the disease and the survival of cancer patients (

Figure 4A). The -21M/T genotype showed opposite effects in BC patients treated with BCG or with other therapies. While in patients with other treatments the MM genotype was associated with shorter 75p-PFS (7.0±2.2 vs. 16.0±4.8 and 19.0±4.7 months, p=0.415) and 75p-OS (8.0±2.4 vs. 21.0±3.4 and 19.0±4.9 months, p=0.131) than the MT and TT genotypes, in BCG-treated patients the MM genotype was associated with longer 75p-PFS (not reached vs. 47.00±18.6 and 36.0±12.0 months, p=0.100) and 75p-OS (not reached vs. 68.0±13.7 and 52.0±8.3 months, p=0.034) than the MT and TT genotypes. In other cancers, the HLA-B -21M/T genotype was not associated with differential PFS or OS.

HLA -21M/T genotype was an independent predictive parameter of the PFS (HR=2.08, p=0.01) and the OS (HR=2.059, p=0.039) of BC patients treated with BCG, together with tumor size (HR=3.064, p=0.001), tumor pattern (HR=2.224, p=0.035), and tumor recurrence (HR=3.198, p=0.001) for PFS; and age (HR=1.068, p=0.007) and tumor staging (HR=2.989, p=0.064) for OS.

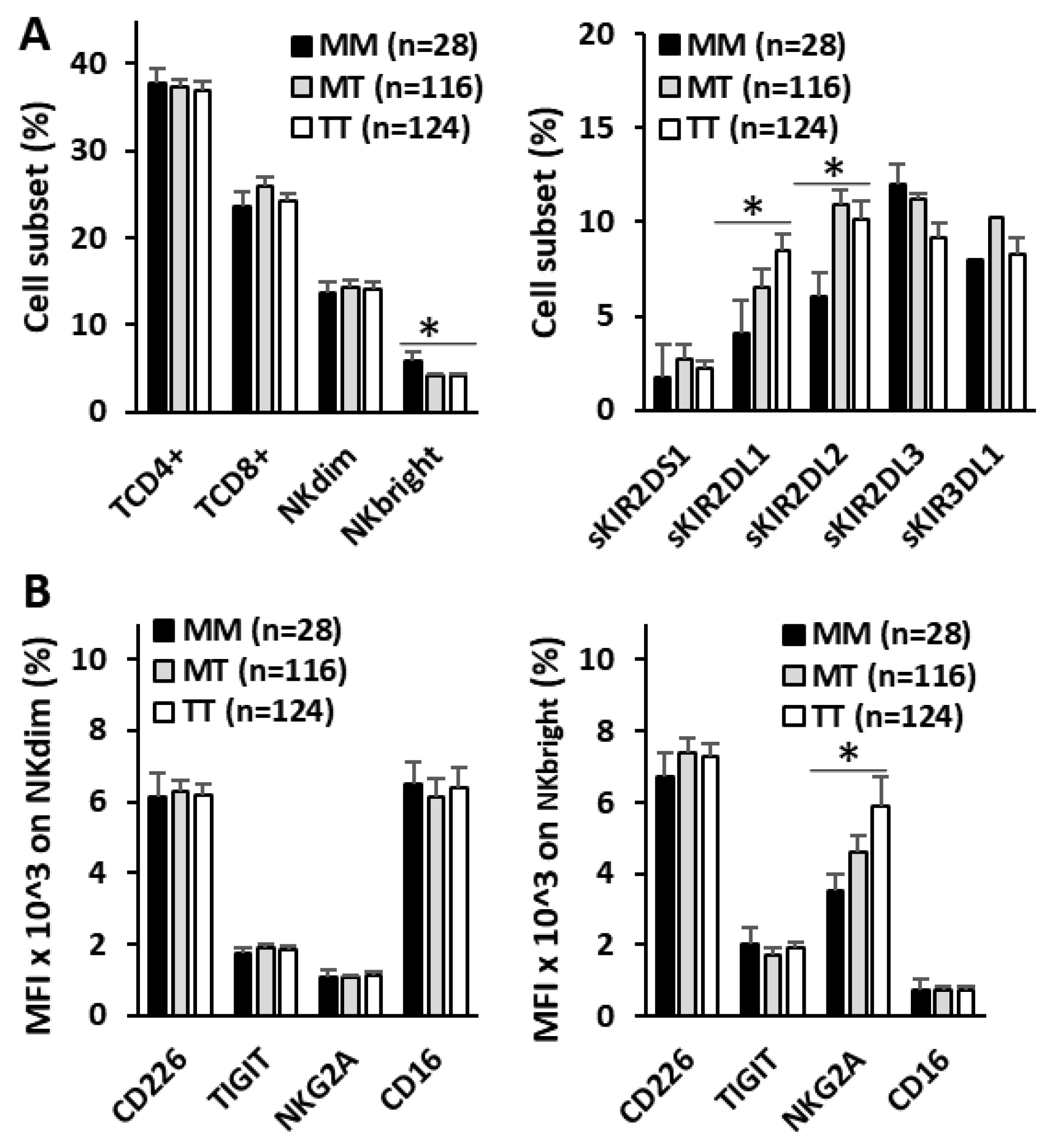

3.4. HLA-B -21M/T Genotype Is Associated with Differential Repertoire of KIR+ NK Cells and Expression of NKG2A in CD56bright NK Cells

To evaluate the imprint that HLA-B -21M/T genotype might have on antitumor effectors, the repertoire of NK and T lymphocytes and the expression of activating (CD226 and CD16) and inhibitory (TIGIT and NKG2A) receptors in NK cells were evaluated in the peripheral blood of 268 BC patients at diagnosis (

Figure 5). No differences in the numbers of CD4

+ and CD8

+ T lymphocytes or CD56

dim NK cells were associated with the HLA-B -21M/T genotype. However, the MM genotype showed higher frequency of CD56

bright NK cells (5.82±1.07%, 4.12±0.28% and 4.09±0.28%, p<0.05) and lower frequency of NK cells expressing single-KIR2DL1

+ (4.12±0.58%, 6.54±085% and 8.51±0.83%, p<0.05) and single-KIR2DL2/S2

+ (6.07±1.60%, 10.95±1.47% and 10.14±1.01%, p<0.05) receptors than MT and TT genotypes.

Although no differences in the expression of CD226, CD16 or TIGIT were associated with the HLA-B -21M/T genotype in CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells, the expression of NKG2A decreased proportionally to the number of -21M ligands (3.5±0.50, 4.6±0.45 and 5.9±0.8 MFIx10^3, p<0.05, for MM, MT and TT genotypes) in CD56bright but not in CD56dim NK cells.

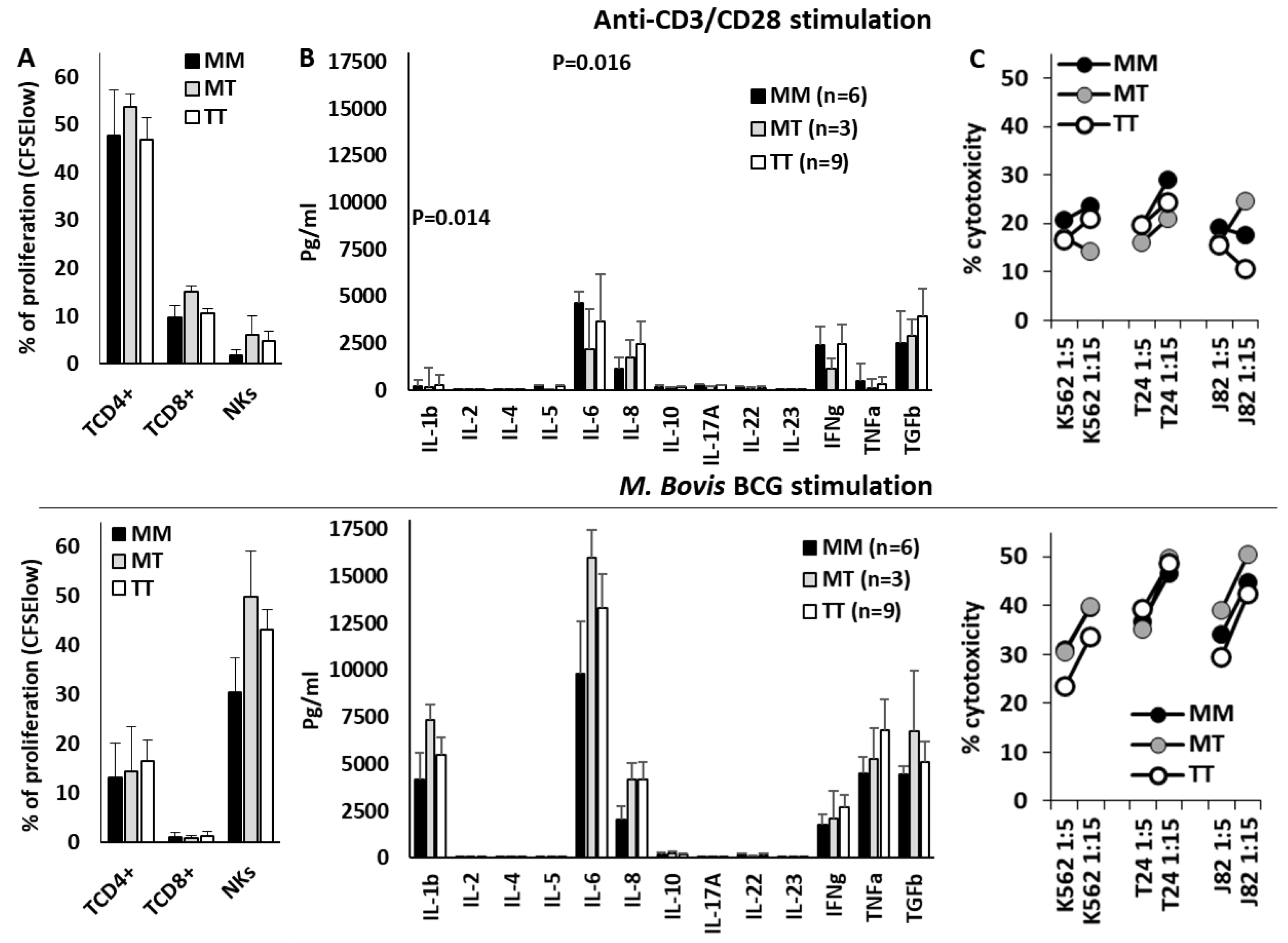

3.5. HLA-B -21M/T Genotype Was not Associated with Differential NK Cell Functionality In Vitro

Finally, T and NK cell effector functions were evaluated in PBMCs of 18 donors stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3/CD28 or BCG (

Figure 6). Anti-CD3/CD28 mainly stimulated the proliferation of CD4+ T cells, whilst BCG strongly stimulated the proliferation of NK cells and the secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, IFNγ, TNFα and TGFβ1. Nonetheless, the HLA-B -21M/T genotype was not associated with any significant variation in the effector function of NK or T cells after anti-CD3/CD28 or BCG stimulation, in the secretion of cytokines, the proliferation of T or NK cells, or the cytotoxic capacity of NK cells.

4. Discussion

Following BCG treatment of NMIBC, a 32.6% to 42.1% local recurrence and a 9.5% to 13.4% progression is usually observed [

43]. Unfortunately, radical cystectomy is the only definitive treatment option for BCG unresponsive disease, leaving patients at high risk for complications and diminished quality of life [

44]. Several immune-escape mechanisms associated with BCG therapy have been described, including loss of HLA-I or increased PD-L1 expression in tumor cells [

45,

46]. Immunotherapeutic strategies, especially those engaging the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, to unleash exhausted immune cells, have modestly improved BC outcome [

47]. NKG2A/HLA-E interaction has been identified as a potent immune checkpoint regulating both CD8T and NK cells [

48]. In fact, combined PD-1/PD-L1 and NKG2A/HLA-E immunotherapy has demonstrated an improved objective response in a Phase 2 clinical trial of patients with nonresectable, stage III non-small-cell lung cancer [

49]. Recent results have shown that IFN-γ induced by BCG-treatment enhances HLA-E and PD-L1 expression in recurrent tumors and NKG2A expression on intra-tumoral NK and CD8T cells, and have provided a framework for combined NKG2A and PD-L1 blockade strategy for bladder-sparing treatment of BCG-unresponsive BC [

36]. However, our results show that the role of the NKG2A/HLA-E interaction in the success of BCG therapy, and other therapies, might diverge dramatically as a function of the HLA-B -21M/T genotype, with MM patients having a very favorable outcome if treated with BCG but very unfavorable when treated with other therapies. These results appear to indicate that HLA-B genotyping could help to personalize these immunotherapies to improve the outcomes in BC.

In fact, the results presented in this work have two potential therapeutic implications. On the one hand, in NMIBC, BCG should be the treatment of choice in patients with MM genotype and blockade of NKG2A/HLA-E interaction should be questioned, since it could worsen the good results observed in these patients. On the other hand, blocking this immune checkpoint in patients who are going to receive non-BCG therapies would be fully justified, although in view of the good results obtained with BCG therapy in patients with NMIBC, the use of BCG therapy should also be considered in patients with MIBC before radical cystectomy. Nonetheless, this decision should be based on new studies with larger series and properly randomized trials.

Therefore, the NKG2A/HLA-E licensing interaction appears to have a counteracting effect depending on the treatment. In patients with MIBC under conventional therapy, the inhibitory function of NKG2A in the presence of its specific ligand, HLA-E highly expressed by the double dose of -21M, seems to predominate [

34,

35,

36]. However, the microenvironment induced by BCG stimulation seems to enhance the antitumor activity of NK cells that might have received a more potent education in the presence of -21M [

26]. To try to understand the mechanism involved in this divergence, we analyzed the peripheral blood NK cell repertoire and the expression of activating and inhibitory receptors in BC patients at diagnosis. It was observed that MM genotypes were associated with higher frequencies of CD56

bright NK cells, which also showed lower NKG2A expression, indicating a strong interaction with its ligand HLA-E [

50]. In addition, these patients had fewer single-positive KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL2 NK cells, although this may be due to the worse Bw4/C2 ligand-mediated licensing typically observed in MM genotypes [

26,

30]. Nonetheless, the combination of lower NKG2A expression and fewer NK cells expressing KIR2DL1 could be mimicking combination therapy with Monalizumab (anti-NKG2A) and Lirilumab (anti-KIR2DL1/3), which prevents tumor metastasis by activating NK-mediated circulating tumor cells elimination [

51]. However, these -21M/T genotype-induced differential features did not appear to be translated into the functionality of NK cells once stimulated in vitro with BCG or into that of T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28. Therefore, further multi-omics studies will be necessary to identify the mechanisms involved in this differential effect of -21M/T genotypes, mechanisms that could be of particular importance in BC as they do not seem to be active in other types of cancer.

Our study has clear limitations, on the one hand the low frequency of the MM genotype (≈11.0% in BC patients and healthy controls), which has limited the follow-up to 17 MM cases in each of the treatment groups (BCG and other therapies); and on the other hand, the fact that we have not been able to identify functional aspects in NK cells or T lymphocytes that could justify the differences in patient outcome associated with the -21M/T genotypes, especially after having identified differences in their circulating NK cells. It is likely that our in vitro model was not able to emulate the complexity of the tumor microenvironment, and therefore, in order to corroborate these results, it will be necessary to perform in vitro 3D cultures to model the tumor microenvironment and/or to develop experimental animal models.

In conclusion, although our data should be confirmed in experimental models and clinical trials, they suggest that the study of the HLA-B -21M/T genotype could contribute to optimize immunotherapy in patients with bladder cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R.L, A.M. and L.G.; methodology, I.R.L, L.G, M.V.M.S and A.L.A.; software, A.M, P.L.C, L.G and I.R.L; validation, I.R.L, L.G, T.F.A, L.J.A.E, G.D.I and A.M.; formal analysis, I.R.L, L.G, P.L.C, A.L.A and A.M.; investigation, I.R.L., L.G.A, G.S, P.L.G.M-V, M.V.M.S and A.M.; resources, I.R.L, L.G and A.M.; data curation, A.L.A, P.L.C, T.F.A, L.J.A.E and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.R.L, L.G, P.L.C, A.L.A, J.A.C and A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.V.M.S and A.L.A.; visualization, I.R.L, L.G, P.L.C and A.M.; supervision, L.G, A.M, J.A.C and P.L.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness ISCIII-FIS (PI1302297 and PI20_00161); Seneca Foundation, Science and Technology Agency from Murcia Region (20812-PI-18); Robles Chillida Foundation (L.G.), University of Murcia, Campus Mare Nostrum and Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC PRDMU21540RUIZ). I.R.L. was funded by AECC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Clinic University Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca from Murcia (IRB-00005712, 2013).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of the work will be available upon justified request of the researchers who need it.

Acknowledgments

We would like to give special thanks to all the patients and donors who have helped us to carry out this work and to all the clinicians for their determined dedication and collaboration in the collection and interpretation of the clinical data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Babjuk, M.; Burger, M.; Capoun, O.; Cohen, D.; Compérat, E.M.; Dominguez Escrig, J.L.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer (Ta, T1, and Carcinoma in Situ). Eur Urol 2022, 81, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaig, T.W.; Spiess, P.E.; Abern, M.; Agarwal, N.; Bangs, R.; Boorjian, S.A.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Bladder Cancer, Version 2.2022. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2022, 20, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieczorek, E.; Garstka, M.A. Recurrent bladder cancer in aging societies: Importance of major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation. Int J Cancer 2021, 148, 1808–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cimadamore, A.; Blanca, A.; Massari, F.; Vau, N.; Scarpelli, M.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for the Treatment of Bladder Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, M.; Enting, D. Immune Responses in Bladder Cancer-Role of Immune Cell Populations, Prognostic Factors and Therapeutic Implications. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 01270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cuesta, E.M.; Esteso, G.; Alvarez-Maestro, M.; López-Cobo, S.; Álvarez-Maestro, M.; Linares, A.; et al. Characterization of a human anti-tumoral NK cell population expanded after BCG treatment of leukocytes. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1293212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandau, S.; Riemensberger, J.; Jacobsen, M.; Kemp, D.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, X.; et al. NK cells are essential for effective BCG immunotherapy. Int J Cancer 2001, 92, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secanella-Fandos, S.; Noguera-Ortega, E.; Olivares, F.; Luquin, M.; Julián, E. Killed but metabolically active mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin retains the antitumor ability of live bacillus Calmette-Guérin. Journal of Urology 2014, 191, 1422–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttmann, H.; Jacobsen, M.; Reiss, K.; Jocham, D.; Böhle, A.; Brandau, S. Mechanisms of bacillus Calmette-Guerin mediated natural killer cell activation. J Urol 2004, 172, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maasho, K.; Opoku-Anane, J.; Marusina, A.I.; Coligan, J.E.; Borrego, F. Cutting Edge: NKG2D is a costimulatory receptor for human naive CD8+ T cells. J Immunol 2005, 174, 4480–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoe, M.; Ogawa, Y.; Takeshita, K.; Morita, J.; Iwamoto, S.; Miyazaki, A.; et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin-pulsed dendritic cells stimulate natural killer T cells and gammadeltaT cells. Int J Urol 2007, 14, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cuesta, E.M.; López-Cobo, S.; Álvarez-Maestro, M.; Esteso, G.; Romera-Cárdenas, G.; Rey, M.; et al. NKG2D is a key receptor for recognition of bladder cancer cells by IL-2-activated NK cells and BCG promotes NK cell activation. Front Immunol 2015, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béziat, V.; Hilton, H.G.; Norman, P.J.; Traherne, J.A. Deciphering the killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor system at super-resolution for natural killer and T-cell biology. Immunology 2017, 150, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anfossi, N.; André, P.; Guia, S.; Falk, C.S.; Roetynck, S.; Stewart, C.A.; et al. Human NK Cell Education by Inhibitory Receptors for MHC Class I. Immunity 2006, 25, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Heller, G.; Chewning, J.; Kim, S.; Yokoyama, W.M.; Hsu, K.C. Hierarchy of the Human Natural Killer Cell Response Is Determined by Class and Quantity of Inhibitory Receptors for Self-HLA-B and HLA-C Ligands. The Journal of Immunology 2007, 179, 5977–5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, L.M. Current perspectives on natural killer cell education and tolerance: Emerging roles for inhibitory receptors. Immunotargets Ther 2015, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, A.; Djaoud, Z.; Nemat-Gorgani, N.; Blokhuis, J.; Hilton, H.G.; Béziat, V.; et al. Class I HLA haprotypes form two schools that educate NK cells in different ways. Sci Immunol 2016, 1, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enqvist, M.; Ask, E.H.; Forslund, E.; Carlsten, M.; Abrahamsen, G.; Béziat, V.; et al. Coordinated Expression of DNAM-1 and LFA-1 in Educated NK Cells. The Journal of Immunology 2015, 194, 4518–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamón, C.F.; Martínez-Sánchez, M.V.; Gimeno, L.; Mrowiec, A.; Martínez-García, J.; Server-Pastor, G.; et al. NK Cell Education in Tumor Immune Surveillance: DNAM-1/KIR Receptor Ratios as Predictive Biomarkers for Solid Tumor Outcome. Cancer Immunol Res 2018, 6, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J.R.; Salzillo, T.C.; Chakravarti, N.; Kararoudi, M.N.; Trikha, P.; Foltz, J.A.; et al. Education-dependent activation of glycolysis promotes the cytolytic potency of licensed human natural killer cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, 143, 346–358.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodridge, J.P.; Jacobs, B.; Saetersmoen, M.L.; Clement, D.; Hammer, Q.; Clancy, T.; et al. Remodeling of secretory lysosomes during education tunes functional potential in NK cells. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kärre, K. Natural killer cell recognition of missing self. Nat Immunol 2008, 9, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parham, P. MHC class I molecules and KIRS in human history, health and survival. Nat Rev Immunol 2005, 5, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pende, D.; Falco, M.; Vitale, M.; Cantoni, C.; Vitale, C.; Munari, E.; et al. Killer Ig-Like Receptors (KIRs): Their Role in NK Cell Modulation and Developments Leading to Their Clinical Exploitation. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, H.G.; Parham, P. Missing or altered self: Human NK cell receptors that recognize HLA-C. Immunogenetics 2017, 69, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A.; Djaoud, Z.; Nemat-Gorgani, N.; Blokhuis, J.; Hilton, H.G.; Béziat, V.; et al. Class I HLA haplotypes form two schools that educate NK cells in different ways. Sci Immunol 2016, 1, eaag1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braud, V.M.; Allan, D.S.; O’Callaghan, C.A.; Söderström, K.; D’Andrea, A.; Ogg, G.S.; et al. HL-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature 1998, 391, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Botet, M.; Llano, M.; Navarro, F.; Bellón, T. NK cell recognition of non-classical HLA class I molecules. Semin Immunol 2000, 12, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Goodlett, D.R.; Ishitani, A.; Marquardt, H.; Geraghty, D.E. HLA-E surface expression depends on binding of TAP-dependent peptides derived from certain HLA class I signal sequences. J Immunol 1998, 160, 4951–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, E.J.; Romero, V.; Diaz-Giffero, F.; Zuñiga, J.; Koka, P. Natural Killer Cell Receptor NKG2A/HLA-E Interaction Dependent Differential Thymopoiesis of Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells Influences the Outcome of HIV Infection. J Stem Cells 2007, 2, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, A.M.; Song, W.; He, D.; Mulenga, J.; Allen, S.; Hunter, E.; et al. HLA-B signal peptide polymorphism influences the rate of HIV-1 acquisition but not viral load. J Infect Dis 2012, 205, 1797–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, A.M.; Sabbaj, S.; Easlick, J.; Goepfert, P.; Kaslow, R.A.; Tang, J. Dimorphic HLA-B signal peptides differentially influence HLA-E- and natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis of HIV-1-infected target cells. Clin Exp Immunol 2013, 174, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallner, A.; Bernson, E.; Hussein, B.A.; Ewald Sander, F.; Brune, M.; Aurelius, J.; et al. The HLA-B -21 dimorphism impacts on NK cell education and clinical outcome of immunotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2019, 133, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, T.; Seow, S.V.; Wong, D.; Robinson, M.; Campana, D. Blocking expression of inhibitory receptor NKG2A overcomes tumor resistance to NK cells. J Clin Invest 2019, 129, 2094–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Narita, S.; Fujiyama, N.; Hatakeyama, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Kato, R.; et al. Impact of germline HLA genotypes on clinical outcomes in patients with urothelial cancer treated with pembrolizumab. Cancer Sci 2022, 113, 4059–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranti, D.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.A.; Bieber, C.; Strandgaard, T.; Salomé, B.; et al. HLA-E and NKG2A Mediate Resistance to, M. bovis BCG Immunotherapy in Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. BioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moch, H.; Humphrey, P.A.; Ulbright, T.M. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Fourth edition. 2016.

- Guillamón, C.F.; Martínez-Sánchez, M.V.; Gimeno, L.; Mrowiec, A.; Martínez-García, J.; Server-Pastor, G.; et al. NK Cell Education in Tumor Immune Surveillance: DNAM-1/KIR Receptor Ratios as Predictive Biomarkers for Solid Tumor Outcome. Cancer Immunol Res 2018, 6, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno, L.; González-Lozano, I.; Soto-Ramírez, M.F.; Martínez-Sánchez, M.V.; López-Cubillana, P.; Fuster, J.L.; et al. CD8+ T lymphocytes are sensitive to NKG2A/HLA-E licensing interaction: Role in the survival of cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 1986943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretta, L.; Moretta, A. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptors. Curr Opin Immunol 2004, 16, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamón, C.F.; Gimeno, L.; Server, G.; Martínez-Sánchez, M.V.; Escudero, J.F.; López-Cubillana, P.; et al. Immunological Risk Stratification of Bladder Cancer Based on Peripheral Blood Natural Killer Cell Biomarkers. Eur Urol Oncol 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamón, C.F.; Martínez-Sánchez, M.V.; Gimeno, L.; Mrowiec, A.; Martínez-García, J.; Server-Pastor, G.; et al. NK Cell Education in Tumor Immune Surveillance: DNAM-1/KIR Receptor Ratios as Predictive Biomarkers for Solid Tumor Outcome. Cancer Immunol Res 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, A.M.; Li, R.; O’Donnell, M.A.; Black, P.C.; Roupret, M.; Catto, J.W.; et al. Predicting Response to Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin Immunotherapy: Are We There Yet? A Systematic Review. Eur Urol 2018, 73, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.S.; Shan, B.L.; Shan, L.L.; Chin, P.; Murray, S.; Ahmadi, N.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Surg Oncol 2016, 25, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouanne, M.; Adam, J.; Radulescu, C.; Letourneur, D.; Bredel, D.; Mouraud, S.; et al. BCG therapy downregulates HLA-I on malignant cells to subvert antitumor immune responses in bladder cancer. J Clin Invest 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M.; Hilsendecker, A.; Pertoll, A.; Stühler, V.; Walz, S.; Rausch, S.; et al. PD-L1 Expression in High-Risk Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer Is Influenced by Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedke, J.; Black, P.C.; Szabados, B.; Guerrero-Ramos, F.; Shariat, S.F.; Xylinas, E.; et al. Optimizing outcomes for high-risk, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: The evolving role of PD-(L)1 inhibition. Urol Oncol 2023, 41, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomé, B.; Sfakianos, J.P.; Ranti, D.; Daza, J.; Bieber, C.; Charap, A.; et al. NKG2A and HLA-E define an alternative immune checkpoint axis in bladder cancer. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 1027–1043.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Majem, M.; Barlesi, F.; Carcereny, E.; Chu, Q.; Monnet, I.; et al. COAST: An Open-Label, Phase II, Multidrug Platform Study of Durvalumab Alone or in Combination With Oleclumab or Monalizumab in Patients With Unresectable, Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 3383–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamón, C.F.; Martínez-Sánchez, M.V.; Gimeno, L.; Mrowiec, A.; Martínez-García, J.; Server-Pastor, G.; et al. NK Cell Education in Tumor Immune Surveillance: DNAM-1/KIR Receptor Ratios as Predictive Biomarkers for Solid Tumor Outcome. Cancer Immunol Res 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zuo, F.; Song, J.; Tang, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; et al. Immune checkpoints HLA-E:CD94-NKG2A and HLA-C:KIR2DL1 complementarily shield circulating tumor cells from NK-mediated immune surveillance. Cell Discov 2024, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).