3.1. Time Evolution in Möbius Space

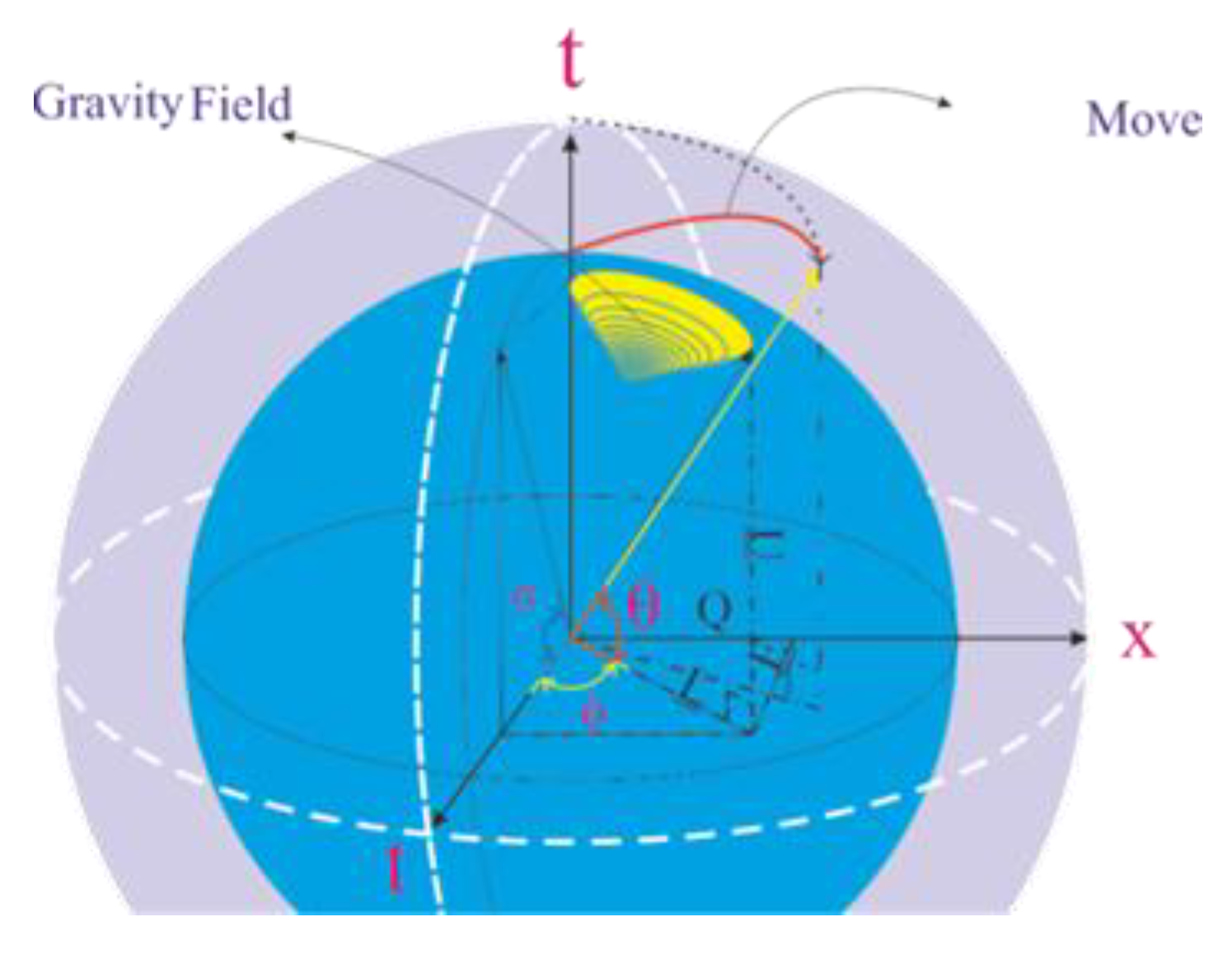

Time originates from geometric potential differences. Within the six-dimensional space-time structure, three-dimensional matter moves under tension in the closed five-dimensional Möbius space, progressing toward regions of lower density along the real dimensions of time. Density variations (Δρ) directly affect the passage of time. Without the passage of time, mass and magnetic fields do not exist. Mass arises from inhomogeneities in space and time, producing negative density and causing the displacement of matter along temporal dimensions and the length of time. This principle explains that without the passage of time, objects in a gravitational field do not fall but move along space-time geodesics within the real dimension of time (e.g., the motion of a ball and feather). Movement through space reduces motion along temporal dimensions (time dilation), appearing as relativistic mass. In Möbius geometry similar to the Klein bottle, density and pressure variations in gravitational fields follow a generalized Bernoulli principle. This principle links hyper-geometric mass distributions to six-dimensional wave function packets expressed by a six-dimensional Fourier series .The packets represent the relation between density variations and field dynamics, connecting gravitational behavior to the Riemann zeta function through prime number distributions. Within this framework, density (ρ) is equivalent to a spatial length (Δx) in space-time; these two are interchangeable. This equivalence allows density variations to be reinterpreted as spatial changes, substituting velocity (v) with density changes (Δρ) From this viewpoint, time (t) is equivalent to a geometric potential difference (Δ

ɸ), explaining the connection between temporal flow and variations in space and geometry.The relation between density variations and the passage of time is expressed as follows. (3.1)

Density and Geometric Potential:

and equivalently:

The logarithmic base k in Möbius space follows the regular spacing between prime numbers in sextuple groups. Moreover, this equation can also have a foundation based on photon density and the speed of light. Accordingly, the general equation is expressed as follows (3.4):

Prime gaps in sextuple groups show a structured distribution. The gaps mainly have values 18, 36, 54, and 72. These values follow a logarithmic model. Differences between consecutive primes repeat periodically. These patterns reflect changes in time and density in higher-dimensional spaces. The spaces include a five-dimensional Möbius space expanding into a sixth dimension. The patterns connect to photon density and the speed of light. This links prime numbers distribution to geometric structures. (3.5)

Table 1

The function f(n) is a periodic function that defines the alternation of prime number gaps based on irregular intervals such as 18, 36, 54, and 72. Constants a, b, and c arise from periodic density variations and prime number groupings. In Möbius geometry, such distributions describe the regular spacing of geodesics in the space-time structure. Density variations correspond to the curvature of the Möbius structure. Density variations are directly related to the arrow of time. Therefore, density behaves like a spatial length over time, rotates around the mass field, and produces the dual-state spin of an object in two temporal dimensions. The radius of the field is directly proportional to the density variation.

Additionally, the generalized Bernoulli principle, derived from motion in the temporal dimension and the constancy of time flow, defines the wave function states in the closed Möbius space based on prime numbers and the meta-geometric distribution of mass.

Accordingly, the relationship between the cosmological constant, the golden ratio, the gravitational constant, and Planck’s constant is expressed through geometric relations within a five-dimensional space expanding into a sixth dimension. (3.6)

Two-dimensional waves oscillate in three dimensions, while three-dimensional waves oscillate in the fourth dimension. Due to the presence of two orthogonal temporal dimensions, the electric field oscillates in one dimension and the magnetic field oscillates in the other. Over time, they periodically interchange within the temporal dimensions, and this interchange within the closed Möbius space introduces a novel definition of superposition. (3.7)

Parallel transport in the closed Möbius space remains stable when the governing laws are homogeneous and isotropic. Accordingly, the necessity of displacement based on prime numbers in the wave function introduces the presence of a wave tensor and a force tensor, which are linked to the fundamental constants of nature, into the final Equation (3.8).

The topology of electron orbitals represents the structure of Möbius space. The structure of the orbitals of an atom is shaped by density changes in six-dimensional space-time. These changes in energy states and the connections between orbitals are regular and have an underlying periodicity of the topology of the gravitational field. A Klein bottle serves as an example of Möbius space, capable of adopting more complex states based on density variations. For instance, the reflection of light from the curved surface of a small stream of water indicates changes in the geometric structure of a surface manifold. Naturally, the distribution of prime numbers over time is influenced by these density variations. Phase shifts between the distances of prime numbers in the defined groups of six reflect the presence of the Bernoulli principle within the geometry of Möbius space. Periodic jumps correspond to discontinuous shifts in geodesic curvature at local minima and maxima of the function, analogous to the throat and flare-out regions in wormhole geometry.

As a result, when two masses exert gravitational influence on one another, they form distinct geometric orbitals that represent orthogonal density domains within the field of each mass. When electrons move between energy levels, or orbitals, the gaps between these energy levels follow patterns similar to those observed in prime numbers. For example, in the six-digit prime groups, common gaps such as 18, 36, 54, and 72 appear periodically. These gaps are influenced by density and energy fluctuations, both of which can be modeled in the Möbius framework. The gaps between energy levels are a periodic function of density fluctuations with changes in the state of the wave function, which overlaps perfectly with the orbital phenomena of the electron.

Δn = Pn - Pn-1, where Δn represents the energy gap, and Pn and Pn-1 represent the successive orbital energy levels obtained by spacing the prime numbers. Symmetry preservation, based on the homogeneity and isotropy of the Möbius space, causes density changes in its geometric structure. Depending on the number of electrons, the orbitals not only adopt different geometric structures, but also express the effects of electrons in regions of negative density within the geometric structure of the orbital. Thus, the relationship between the absence of density and quantum phenomena such as tunneling becomes conceivable. In the universe, dark energy resonance the effects of density changes over time. The resonant reflection of negative density, similar to the fluid flow in Bernoulli’s principle, affects the expansion and expansion rate of the universe. The rotation of Möbius space, which obeys the governing laws of prime numbers, creates the wave function of each particle based on the hypergeometric distribution of mass.

3.2. Gravitational Sensors:

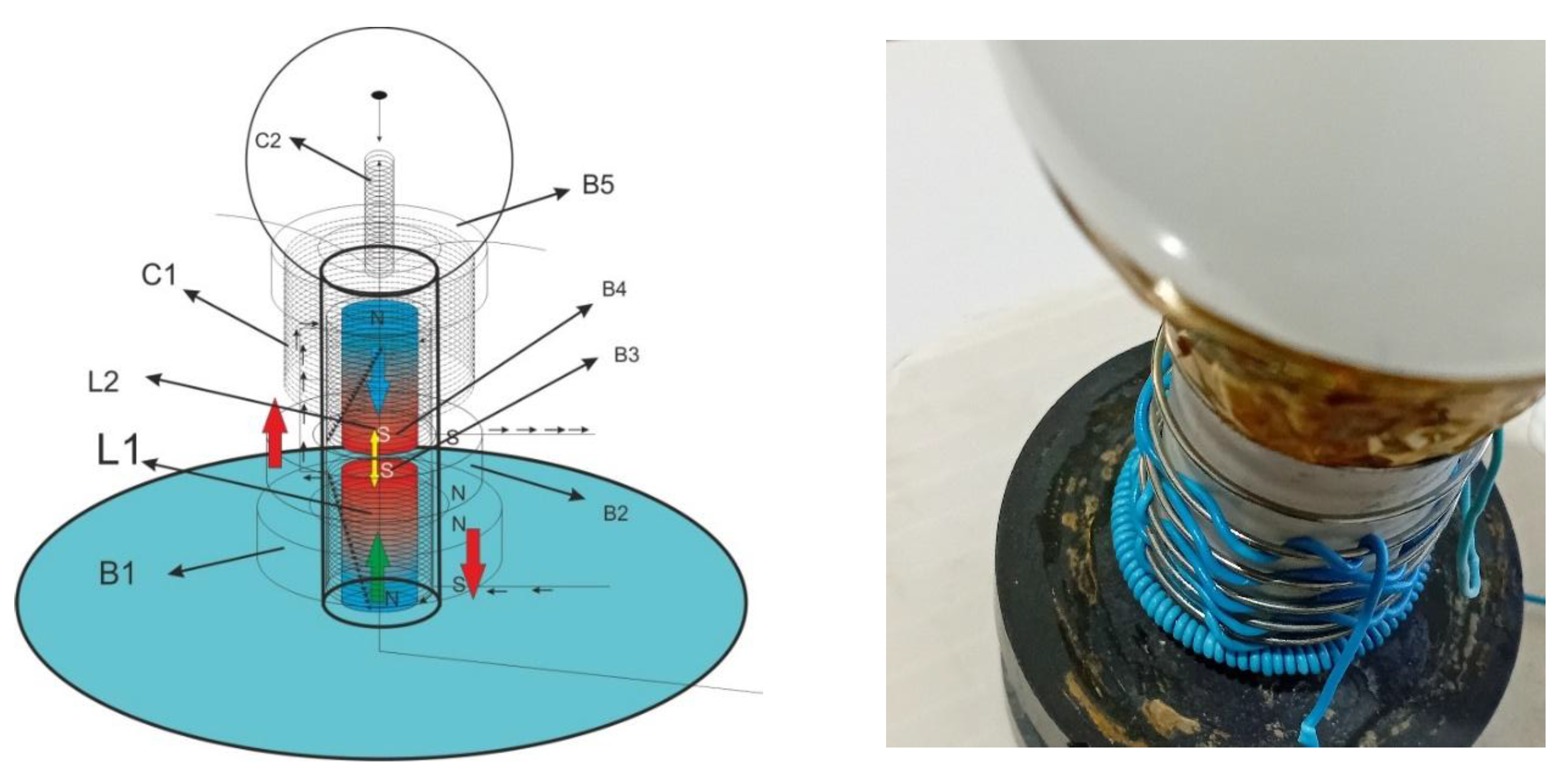

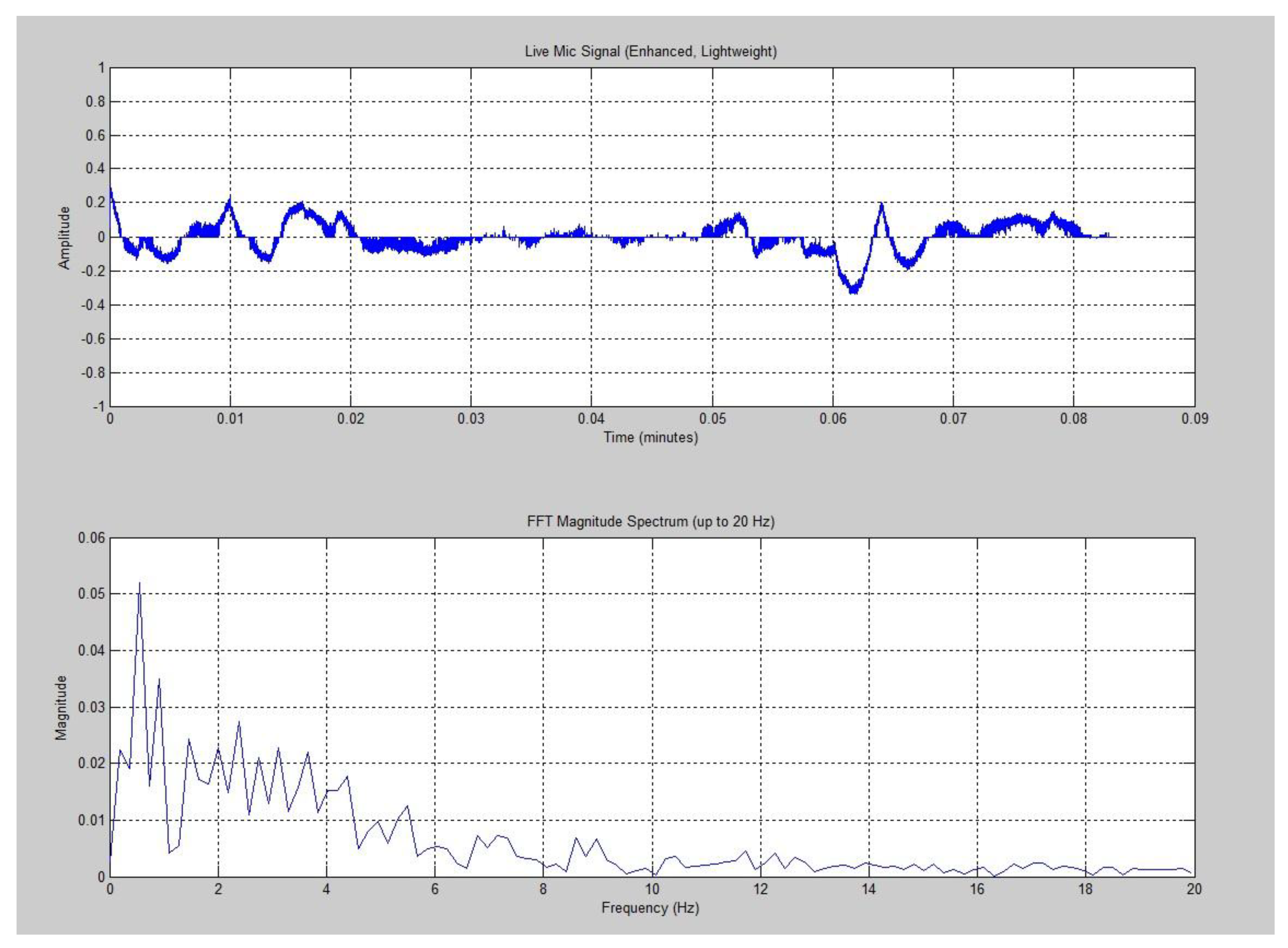

To reduce inductance effects, Möbius coils were designed. Like a Möbius strip, Möbius coils and capacitors transfer higher-dimensional properties to lower dimensions and vice versa .This device shows the ability to generate both positive and negative gravitational fields and can also produce a weak electric current from the gravitational field. This current serves as the sensor output for detecting distortion in a gravitational field. The initial laboratory sample showed the relationship between momentum and wavelength by amplifying gravitational field turbulence. Figure… By Fourier analysis of these fluctuations, it was determined that the device can detect subtle distortions indicative of disturbances caused by momentum or wave-like distortions.

Figure 3.

The Möbius coil consists of two opposing windings connected in series and inversely coupled around a shared magnetic core. The windings remain magnetically isolated and share no mutual connection except through common inductance. Initially, high-voltage, low-current pulses do not pass due to the inductance of the first coil. As the magnetic permeability of the core decreases based on the weight variations of external magnets in a gravitational field a specific current is discharged from the first winding into the second as an instantaneous flux. The reverse current in the second winding, due to its lower inductance, passes through the wire resistance, and with minimal turbulence in the gravitational field, a weak current appears in the Möbius coils as an instantaneous pulse.

Figure 4.

The external magnetic field, induced by natural magnets suspended in isolated conditions and interacting with the gravitational field, transmits distortions caused by the combined effects of gravitational potential energy and magnetic field density changes. Möbius inductors relay these distortions to Möbius capacitors, which are designed with a Möbius geometry and variable dielectric properties. The dielectric variations in the capacitors depend on the current discharged from the Möbius coil. The resulting current undergoes amplification within a loop, generating oscillations whose intervals resemble the structured gaps of prime numbers, akin to the intervals of musical scales. These oscillations, governed by the six-group prime distribution, enable precise identification of the smallest momentum associated with each layer. Such momentum variations can be mapped in spatial coordinates using fast Fourier transformation techniques.

The Möbius coil depends on inductance variations and spike currents generated by turbulence in the gravitational field and time. The Möbius capacitors share a common dielectric, whose variations depend on the output current of the Möbius coils. The system generates oscillations that reflect structured intervals, comparable to the patterns of musical scales. These oscillations resonate in harmony with the prime number gaps distributed across six groups, forming a connection between mathematical intervals and physical oscillations.

Figure 4.

The generalization of Ibn Sahl’s law based on the eccentricity of the ellipse and density variations is observed in the structure of Möbius gravitational sensors. The density changes of an object moving through air alter its density ratio relative to air over time, and from this point of view, antigravity generation by Möbius coils is possible.[

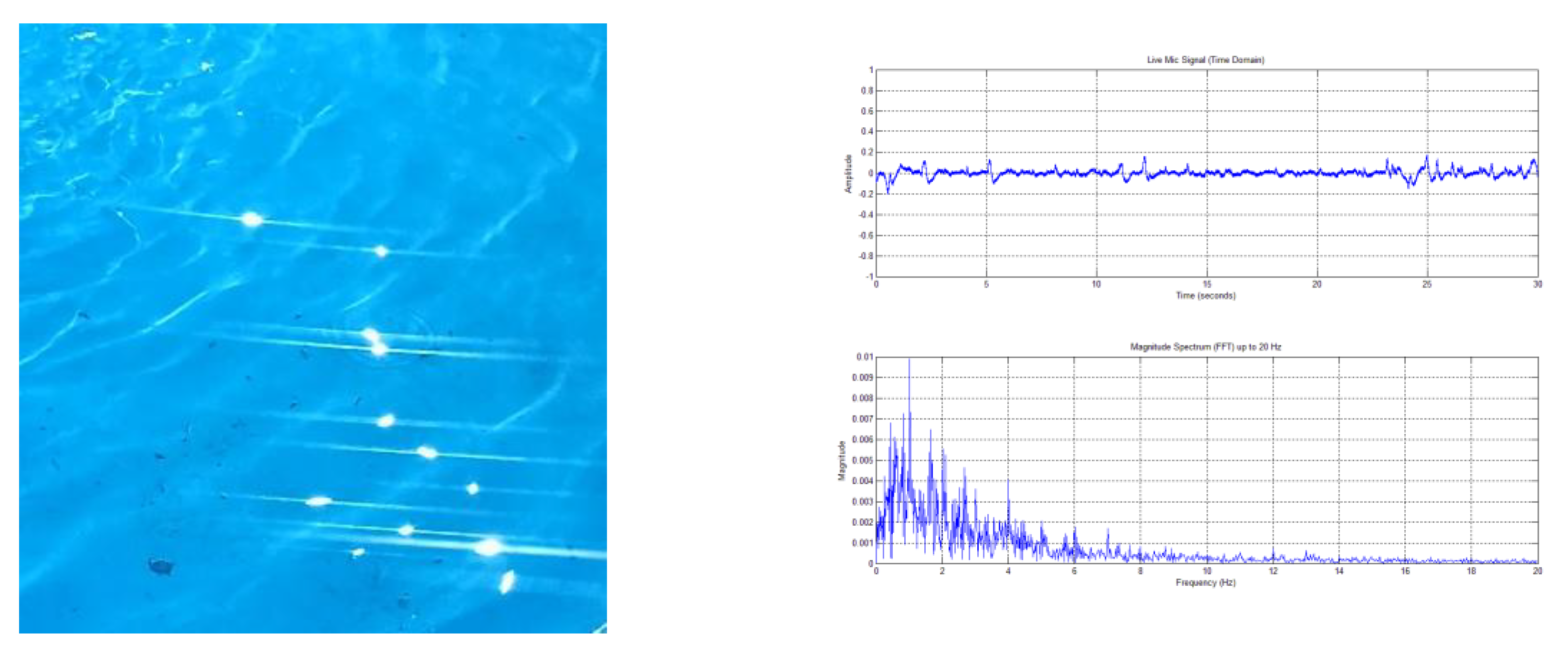

8] Although the de Broglie wavelength for low-momentum objects is not measurable, lambda is wavefunction-dependent, and the ratio of the gravitational field’s wavefunction to that of the moving object is measurable over time using Möbius sensors. Based on Fourier transform and the object’s momentum, direct relations between the gravitational field wavelength and the object’s attributed wavelength can be derived. The gravitational field also rotates in expanding space, and each field has its own wavefunction. The displacement of field layers over time, like a vortex, is measurable through changes in light polarization within the gravitational field.

The average number of aligned polarizations such as repeated upward polarization is dependent on prime numbers and prime number groups.

Figure 5.