2.1. Limitation of Apparent Capacitance due to Alignment Layers

Recently the Boulder group poured a cold shower on entire dielectric society, raising the question of the applicability of dielectric spectroscopy for ferroelectric nematics due to effect of the insulating alignment layers on the apparent/measured values of the dielectric permittivity [27]. They have noticed that the apparent capacitance

Capp of LC cell can be expressed as two capacitances in series: capacitance of the LC layer,

CLC and capacitance of insulating alignment layers,

Cal. Hence the apparent capacitance is

There can be two possible opposite cases: the ordinary case, where

CLC « Cal, and the opposite extraordinary case, where

CLC » Cal. In the ordinary one, i.e., in LCs with the low/moderate dielectric permittivity, capacitance of the LC layer

CLC « Cal and the apparent capacitance according Eq(1) equals to capacitance of LC cell,

Capp= CLC and it gives real/actual value of the capacitance and dielectric permittivity. However, in the liquids/LCs with very high dielectric permittivity (ε > 10,000), such as in the bent-core compounds [25,26] and the ferroelectric N

F phase, the capacitance of LC cell can exceed the capacitance of the alignment layer,

CLC » Cal. In such extraordinary case, the apparent capacitance is limited to the capacitance of the alignment layers,

Cal. We term it as the Clark’s limit,

Capp= Cal or

. Therefore, the answer to the first raised question “Are the real values of dielectric permittivity lower or higher than the measured ones?” is obviously “lower”. However and surprisingly, the original paper [

27] states opposite: “… deriving dielectric constants from electrical impedance measurements of high-polarization ferroelectric liquid crystals, …, can result in overestimation of the

ε’ values of the LC by many orders of magnitude.” [

27], i.e.,

CLC ≪ Capp. An explanation of this contradiction will be given at the end of the article. This limit was studied experimentally which confirms that it is proportional to the cell thickness. In other words in the extraordinary case the apparent capacitance will be linearly dependent on ratio

and these feature were observed and confirmed experimentally [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

In such extraordinary case,

CLC » Cal, the apparent LC capacitance

Capp (and dielectric permittivity) would be limited by Clark’s limit

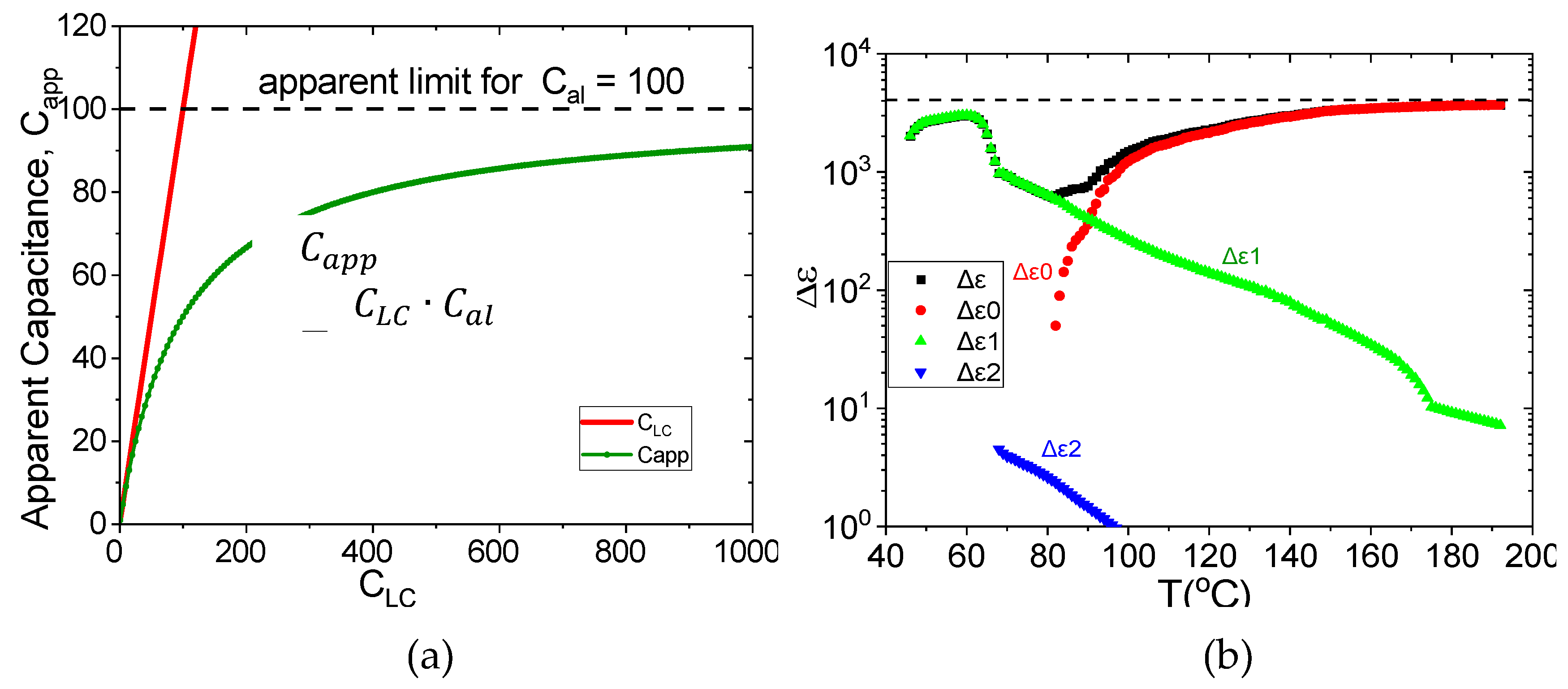

Cal, which is temperature independent. This can be illustrated in the

Figure 1(a), which shows the apparent capacitance as function of the actual capacitance of LC cell for

Cal= 100.

It should be noticed that this dependence is rather smooth, so that even at

CLC = 10∙Cal the apparent capacitance is not completely saturated, reaches only 90% of limit value

Cal and still has 10 % to grow showing weak temperature dependence. Such weak temperature dependence can be seen in the

Figure 1 (b) which presents the temperature dependence of the dielectric strengths of three relaxation processes

Δεi and the total dielectric permittivity, (which includes all three relaxation processes in the measured frequency range, i.e.,

) of 4 μm DIO homeotropic cell, adopted from [

20]. In the middle temperature range where the total dielectric permittivity is rather moderate (~< 1000), i.e., well below the limit, all relaxation processes show strong temperature dependence. However, in the low and high temperature range where the total dielectric permittivity is rather high ~< 3700 the temperature dependence of dielectric strengths shows very weak temperature dependence indicating that they are rather close to the Clark’s limit (~4000 see as dash line

Figure 1(b)) as expected in extraordinary case. Moreover, in the high temperature range the apparent permittivity is higher than in high temperature range it shows weaker temperature dependence according to the

Figure 1(a).

Summarizing the effect of alignment layers in extraordinary case we notice three important features: (i) the apparent capacitance (permittivity) shows very weak temperature dependence; (ii) is linearly dependent on the cell thickness and (iii) the measured dielectric permittivity is limited by the alignment layers.

2.2. Reconstruction of Accutial Value of Apparent Capacitance

Now let’s return to the second question “Can the real values of dielectric permittivity be recovered in the cell with alignment layers?”. In this regard, it is worth noting the following publication which is directly related to this issue and entitled “Constraining the value of the dielectric constant of the ferroelectric nematic phase.” [

30]. The word “constraining” explicitly implies that the measured value of dielectric permittivity is overestimated as noticed in the Ref. [

27] and can be corrected to lower value. To check this question, let’s notice the real dielectric permittivity value, even being limited, can be deduced or recovered from the Eq. (1) with more or less accuracy depending on accuracy of assumed value of limit. Eq.(1) can be rewritten as

or as

for dielectric permittivity.

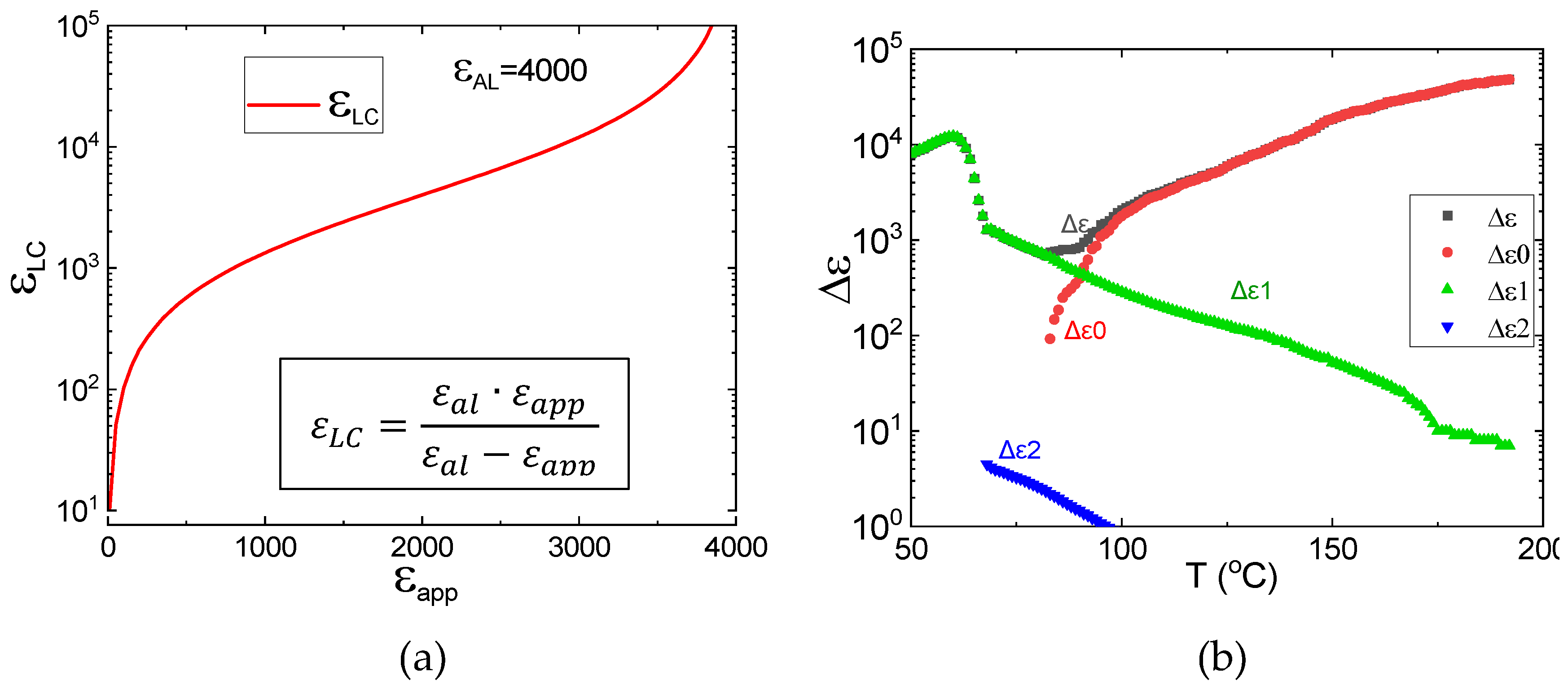

Figure 2(a) presents the dependence of “recovered” LC dielectric permittivity on the apparent permittivity for Clark’s limit of as 4000 and temperature dependence of “recovered” dielectric permittivity of 4 μm DIO homeotropic cell. The value recovered dielectric permittivity diverges on approaching the limit value (

Figure 2(a)) and high recovered permittivity value due to ions (

Figure 2(b)) might have a certain error. However, in the low temperature range corresponding to N

F phase the apparent permittivity is ~3200 which is rather far from the limit of 4000, the value of recovered permittivity ~10000 is rather confident and typical for ferroelectric nematic phase.

This example shows that the retrieved value is higher than apparent one which is opposite to references [

27,

30]. Such contradiction however has a very simple explanation which we are going to demonstrate with help of dielectric spectroscopy.

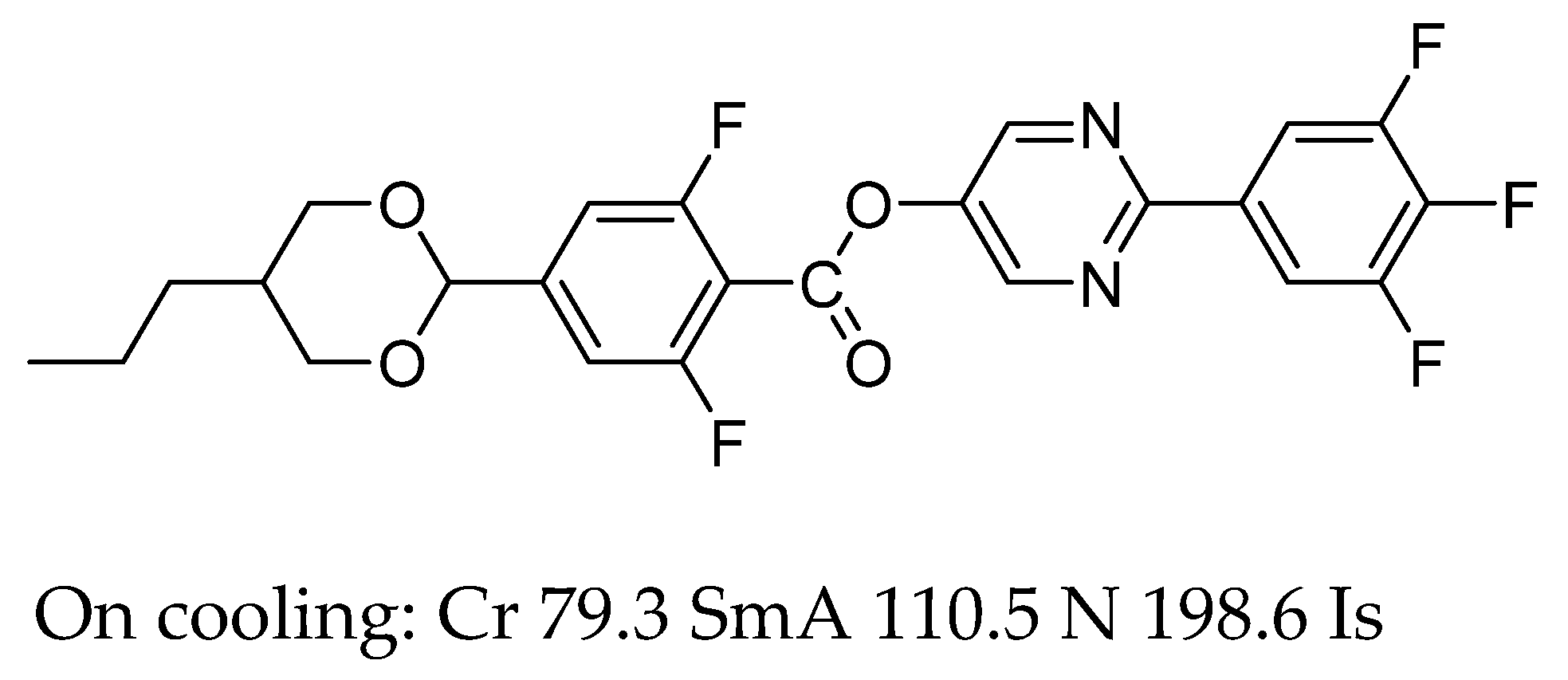

2.4. Dielectric Spectroscopy of Polymer-Coated Planar LC Cells

Dielectric spectroscopy measurements over a frequency range 0.1 Hz–10 MHz were made using a broadband Alpha High Resolution Dielectric Analyzer (Novocontrol GmbH, Germany). We used commercial cells (E.H.C ltd., Japan) of different thicknesses (2, 4, 9, 15 and 25 μm) with both homeotropic and planar alignment and also with uncoated bare ITO electrodes to avoid possible limitation from alignment layers. The ITO electrodes used in these cells have very low sheet resistance (5 Ω/□) to avoid the parasitic peak arising from the sheet resistance of ITO in series with the capacitance of the cell. The measurements were carried out under the application of weak voltage 0.1 V applied across the cell. The temperature of the sample is stabilized to within ± 0.05 oC. The dielectric spectra are analyzed using the Novocontrol WINFIT program.

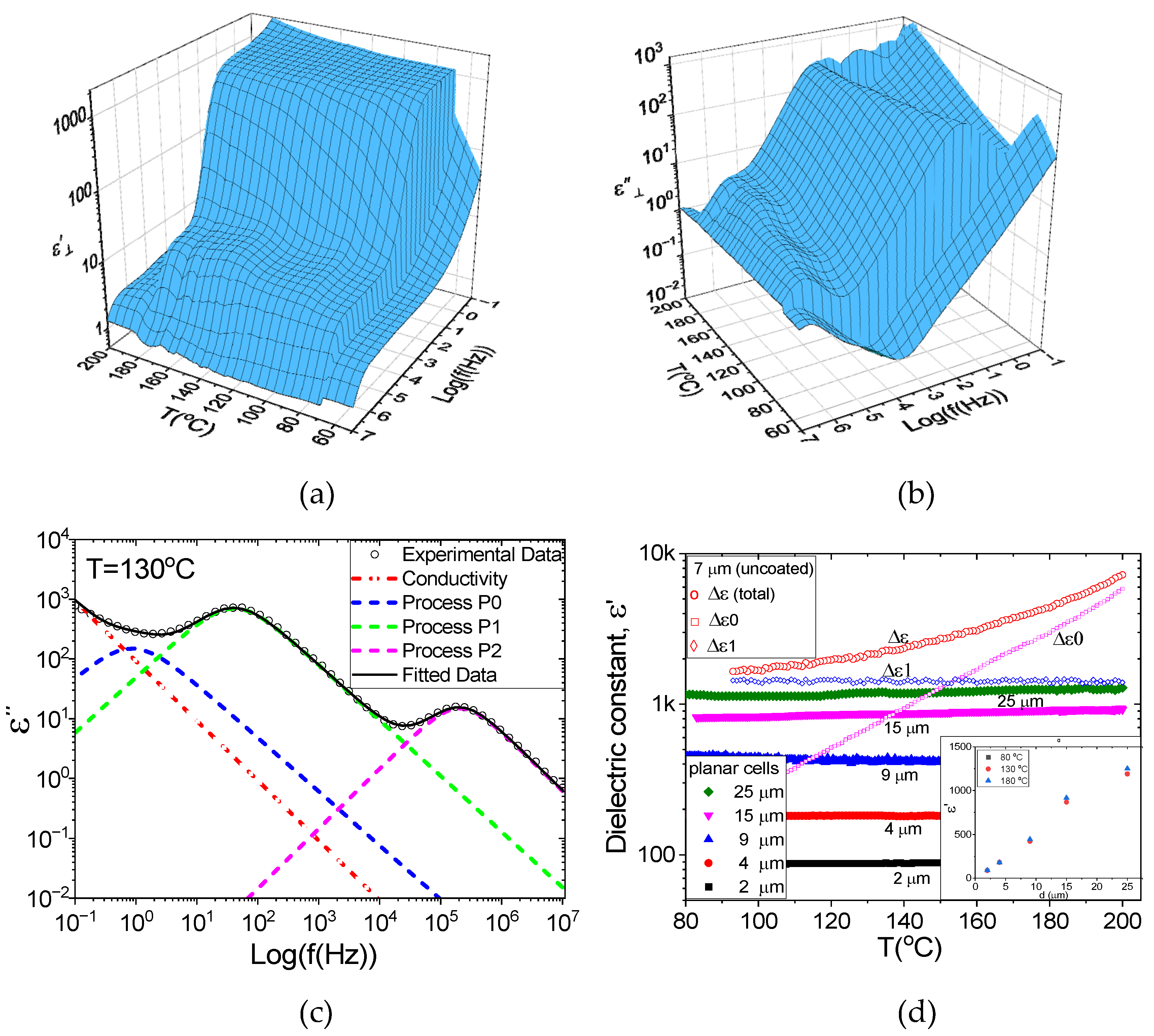

Figure 4 (a,b) shows 3D temperature dependencies of the real (ε’) and imaginary (ε”) parts of the complex permittivity in the frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 10 MHz in a 7 μm uncoated cell.

Let’s consider the results on the cells with electrodes coated by planar alignment layer first.

Figure 3(d) presents the temperature dependence of dielectric permittivity at 0.1 Hz for planar cells of different thicknesses. The dielectric permittivity of these cells is temperature independent and linearly dependent on the cell thickness showing both main features of extraordinary case (

CLC » CAL) and therefore they restricted by Clark’s limit which is linearly increase with cell thickness.

We can estimate capacitance of the insulating alignment layers of our cells

, and assuming the layer thickness

dal= 200 nm, and its permittivity as

εal ~ 5, we obtain

Cal ~ 5.5 nF. This capacitance limits the apparent value of the dielectric permittivity for 4 μm cell to ~100 which is in good agreement with the experimental value of 180, considering that the actual values of thickness and the permittivity of alignment layer may be different from the assumed values. In order to avoid this limitation and to get the actual values of the dielectric permittivity, one needs to increase capacitance of the alignment layers

Cal in approaching the ordinary case

Cal » CLC. The only way to do this is to increase the ratio d/d

AL or just to use uncoated (bare) metal/ITO electrodes [

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. This removes alignment layers limit and allows to measure permittivity up to fantastic ~ 300,000 [

29].

2.5. Dielectric Spectroscopy of Uncoated Cells and Super-Paraelectrics

Figure 3(d) shows the temperature dependence of total dielectric permittivity of uncoated 7 μm cell which is shown as open red circles. The texture was quasi-planar and the expected value of dielectric permittivity of 7 planar cell with alignment layers is ~ 300 (see the inset

Figure 4 (d)). However the permittivity of uncoated cell is ~1300 and it is also temperature dependent, which means we have the ordinary case (

C « CAL) and the apparent (measured) value corresponds to real dielectric permittivity.

The complex permittivity data of 7 μm uncoated cell were fitted to the Havriliak-Negami, Eqn. (2) below to three relaxation processes, P0–P2, and as example of fitting quality for 130

oC is shown in the

Figure 4 (c).

Looking at

Figure 3, the unusual temperature behavior of the relaxation processes P0 and P1 immediately catches the eye. The dielectric strength of the P0, Δε

0 increases exponentially on heating while the Δε

1 is independent off temperature.

The relaxation processes in WJ-16 are somehow similar to those observed in DIO where the physical origin of the relaxation processes in DIO were assigned as follows [

17,

18,

19,

20]: the least frequency P0 arises from the dynamics of ions in the medium having accumulated on the alignment layers [

34,

35], which sometime is called as Electrode Polarization (EP) process [

36] and highest frequency process P2 is individual molecular dynamics around long molecular axis. The lowest frequency relaxation process P0 which is usually considered as “parasitic” and is responsible for abnormal rise of dielectric permittivity on heating to the Isotropic phase.

However the middle frequency relaxation process P1 in WJ-16 has different physical origin than P1 in DIO. In DIO The largest P1 is observed only in N

F phase and was theoretically developed as so-called polarization-capacitance Goldstone (PCG) mode [

27].

However, in WJ-16 it can’t be a Goldstone PCG mode because, firstly, this material does not possess the ferroelectric N

F phase. Secondly, it is also observed in all phases including SmA, nematic and evenisotropic, and thirdly, its dielectric strength is independent of temperature (see

Figure 3(d)). Despite the Colossal Polarization (CP), this substance does not exhibit any ferroelectric properties, instead of that it shows perfect homogeneous domain-free texture and hysteresis-free switching and linear P-E dependence [

37], i.e., behaves overall as typical paraelectric. These properties, together with CP, allow this material to be classified as Super-Para-Electric (SPE). Further details on assignment and other features of SPE are given in the Ref. [

37] here we just use this example to show that the Clark’s limit is observed in non-ferroelectric LCs as well.

In summary we experimentally confirm the limiting effect of alignment layer capacitance. This limit is due to the total dielectric permittivity, which is the sum of contributions of all relaxation processes in the cell. For example, (

Figure 1(b)) in the low temperature range of DIO corresponding to the NF phase the saturation occurs mainly due to the Goldstone mode (P1) while in high temperature range, i.e., in paraelectric N phase, the main contribution comes from the ionic accumulation or EP process. However, WJ-16 does not have ferroelectric N

F but also exhibits CP in SPE state. The dielectric permittivity in SPE (~1300) is about one order smaller than in N

F phase however it may show an extraordinary case in the commercial cells due to rather high alignment layer thickness.

2.6. Further Discussions on Accual Capacitance

Here we switch our attention from the limiting effect of alignment layers to its interpretation in relation of apparent (measured) and real (actual) values of dielectric permittivity. Even though all the research groups agree with this effect, but its interpretation sounds absolutely opposite.

Now it’s the right time to clarify this issue. That this limitation occurs when capacitance of LC exceeds the capacitance of alignment layers, i.e.,

CLC >> Cal ≈ Capp. This explicitly supposes that real capacitance and dielectric permittivity is higher than the apparent value. This is illustrated by number of papers, here we will only give a couple of excerpts from them. Ref. [

17]: “Thus, for studied here materials with very high permittivity the measured equivalent capacity of the circuit might be considerably lower than the actual capacity of LC”. Ref. [

32]: “… the relative permittivity of the ferroelectric nematics is indeed huge, and it is even higher than the apparent measured values” and “… measurements confirm a huge relative permittivity of the ferroelectric nematic phase, which can even be orders of magnitude larger than the measured apparent values”.

However, according to the original opinion [

27] supported in other papers [

30] the Clark’s limit “…can result in overestimation of the

ε’ values of the LC by many orders of magnitude.”, i.e.,

CLC ≪ Capp. However, this contradicts the condition for such limit, i.e.,

CLC >> Cal ≈ Capp

Such curious contradiction can be easily explained by different interpretation of the term “relative permittivity” or historically “dielectric constant”. The Ref. [

30] states that “In this paper, we have once again

ruled out the CP values of the NF phase. In doing so, we have followed the classical definition of permittivity, which

does not include the spontaneous polarization, as in solid ferroelectrics.” Therefore, according to this interpretation, which excludes the ferroelectric Goldstone mode (Δε1) contributing the largest to the total permittivity, and the rest of the permittivity from other weaker processes (Δε2) is less than the apparent one. It is not clear from [

27,

30] whether the authors also exclude Δε0 due to the ionic process P0? If not, as they didn’t mention about it explicitly, the total dielectric permittivity or capacitance may exceed the capacitance of alignment layers without ferroelectric Goldstone mode due to exclusively by ionic mode Δε0 as can be seen in the

Figure 1 (b) for T > 150

oC.

However, such a definition of relative permittivity can hardly be accepted as “classical”. According to classical definition of “dielectric constant” (or “relative permittivity”) it is defined as ratio of the total dielectric permittivity to the permittivity of vacuum, , where ε(ω) is the complex frequency-dependent permittivity of the material which includes all relaxation processes and can be measured as . Accepting this “classical” definition the actual dielectric permittivity in (not only) ferroelectric nematics is higher than the apparent one.