Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

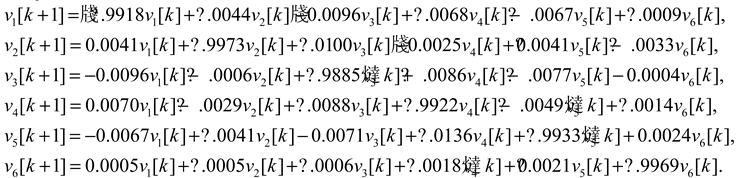

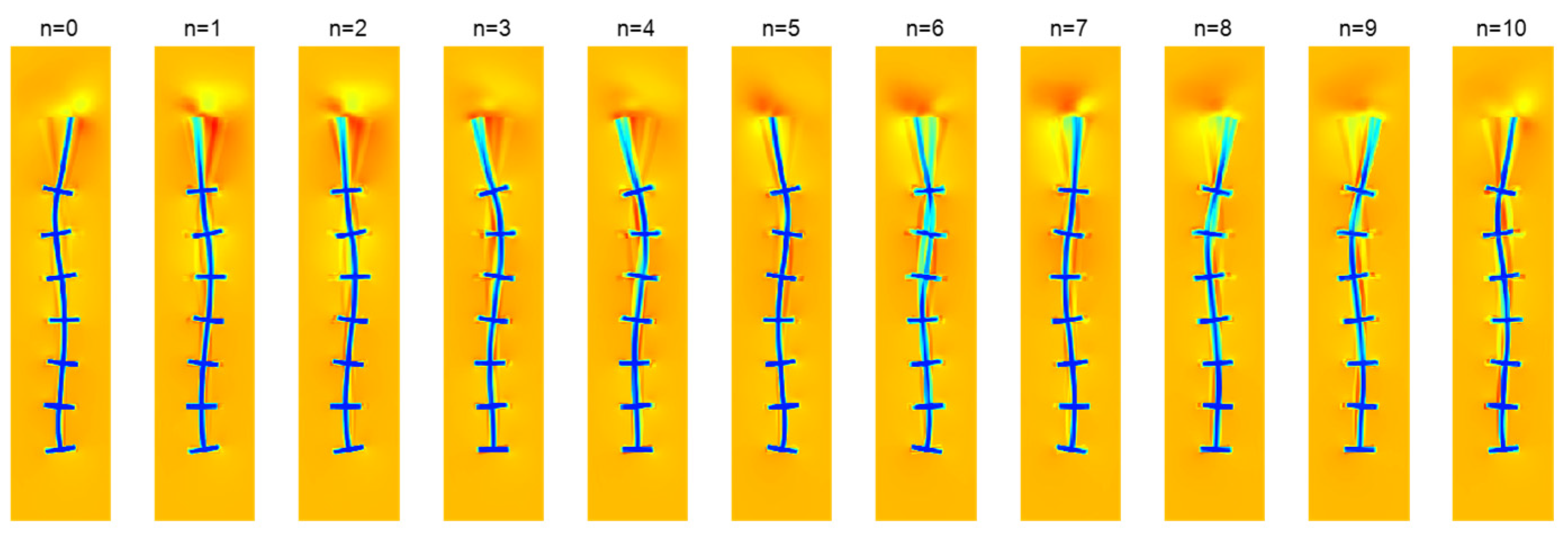

2.1. Data Preparation

2.2. Decomposition and Regression Methods

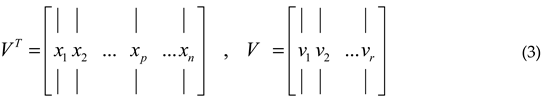

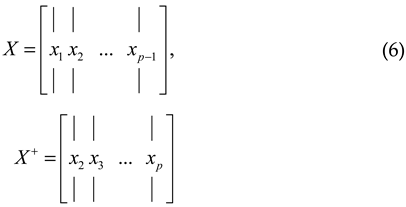

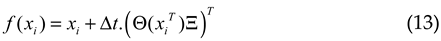

2.2.1. DMD Approach

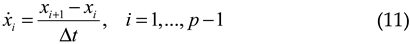

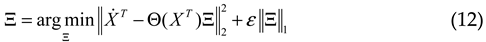

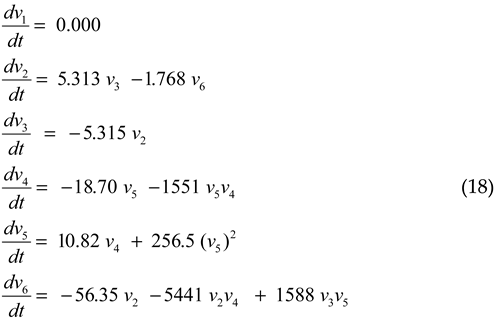

2.2.2. SINDy Approach

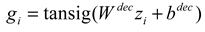

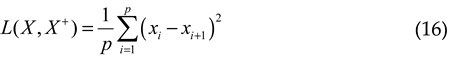

2.2.3. AE NN Approach

3. Results

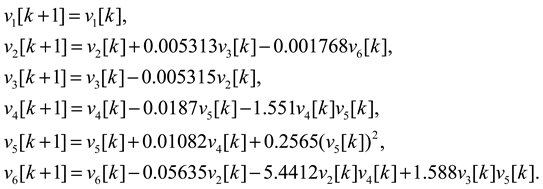

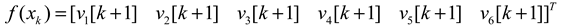

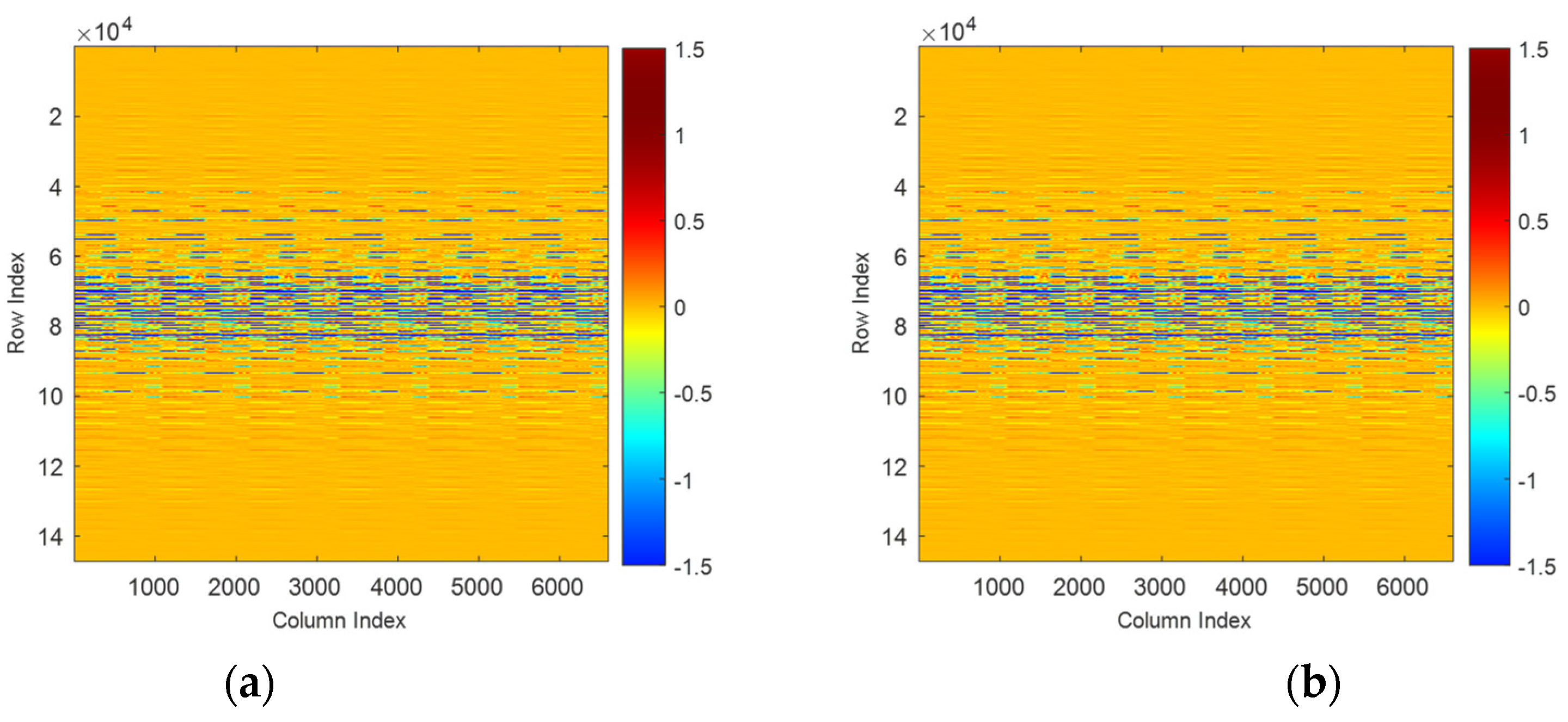

3.1. Regression Function

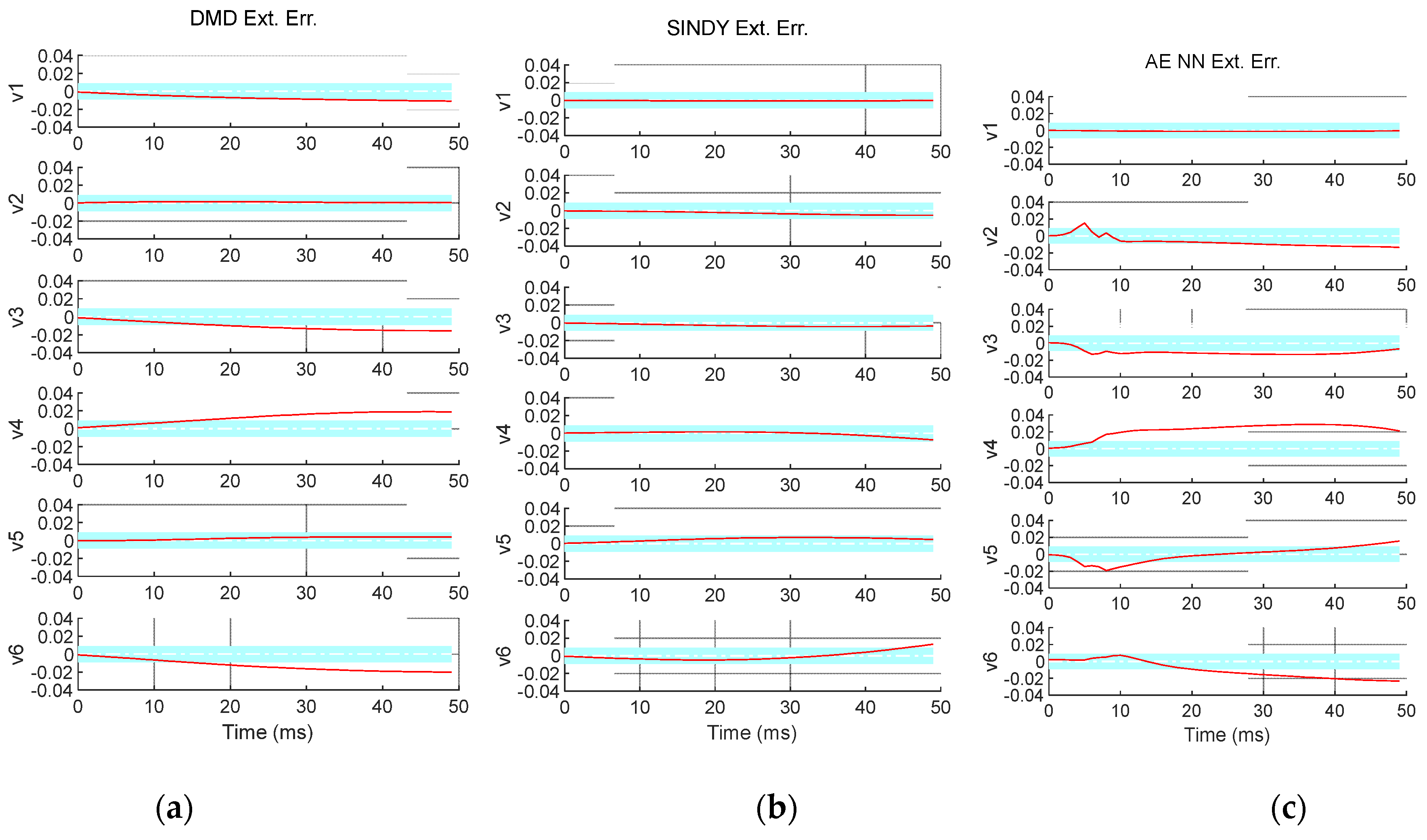

3.2. Simulation of the Regression Methods

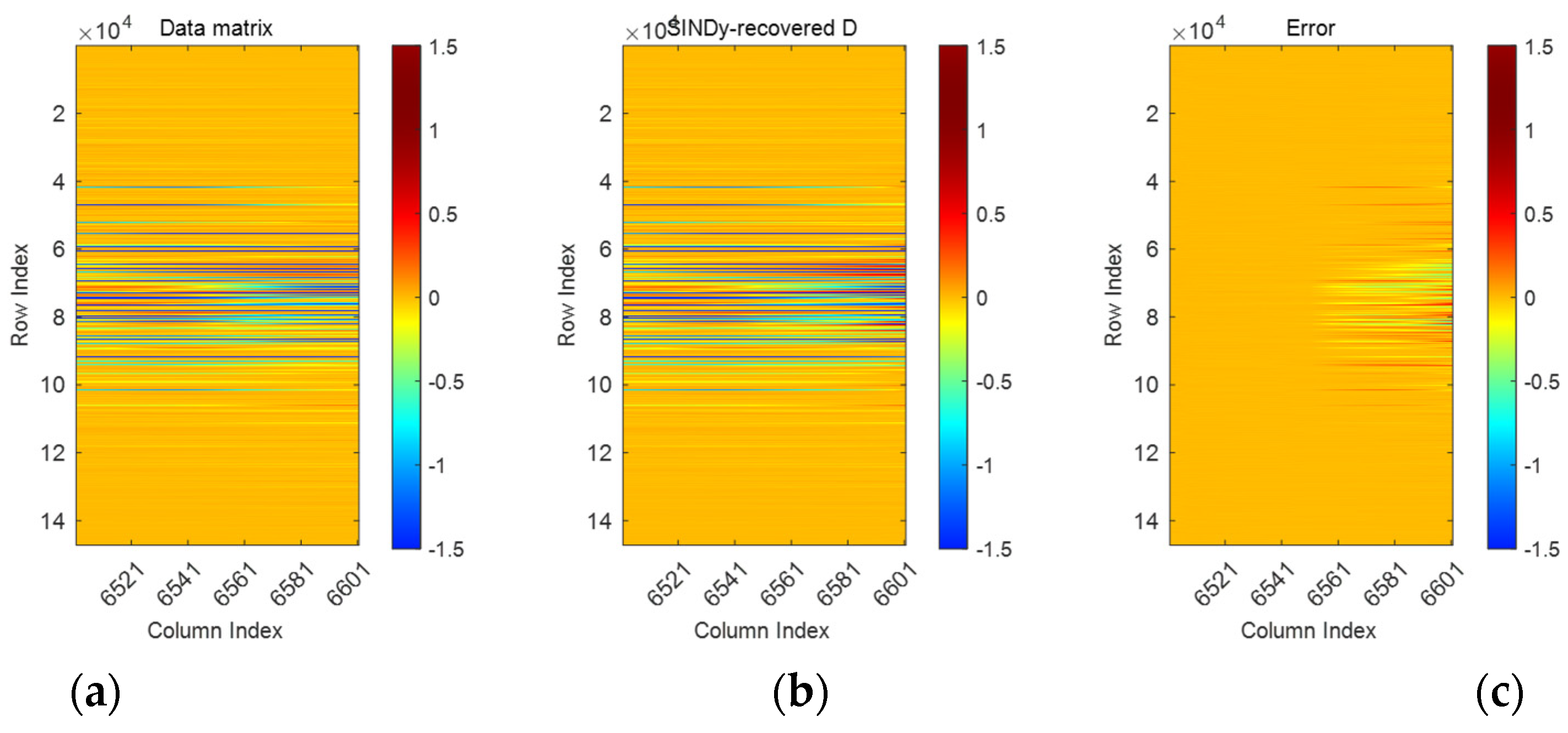

3.3. SINDy Data-Reconstruction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cortez, R.; Sandoval-Chileño, M.A.; Lozada-Castillo, N.; Luviano-Juárez, A. Snake Robot with Motion Based on Shape Memory Alloy Spring-Shaped Actuators. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyidoğlu, B.; Rafsanjani, A. A textile origami snake robot for rectilinear locomotion. Device 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Inada, S.; Shimizu, D. Development of a Snake Robot to Weed in Rice Paddy Field and Trial of Field Test. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration (SII); 2024; pp. 1537–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Thakker, R.; Paton, M.; Strub, M.P.; Swan, M.; Daddi, G.; Royce, R.; Tosi, P.; Gildner, M.; Vaquero, T.; Veismann, M. EELS: Towards Autonomous Mobility in Extreme Terrain with a Versatile Snake Robot with Resilience to Exteroception Failures. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2023; pp. 9886–9893. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, N.; Pailevanian, T.; Ambrose, E.; Archanian, A.; Melikyan, H.; de Mola Lemu, D.L.; Gildner, M. EELS: A Modular Snake-like Robot Featuring Active Skin Propulsion, Designed for Extreme Icy Terrains. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Aerospace Conference; 2024; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Virgala, I.; Varga, M.; Sinčák, P.J.; Merva, T.; Mykhailyshyn, R.; Kelemen, M. Mathematical framework for snake robot motion in a confined space. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2024, 132, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G.; Lanzetti, L.; Mariana, D.; Cinquemani, S. Bioinspired Design and Experimental Validation of an Aquatic Snake Robot. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.S.X.; Tan, M.W.M.; Xu, C.; Yang, Z.; Lee, P.S.; Lum, G.Z. Locomotion of miniature soft robots. Advanced Materials 2021, 33, 2003558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Gravish, N. Multimodal Locomotion in a Soft Robot Through Hierarchical Actuation. Soft Robotics 2024, 11, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, D.R.; Kim, I.; Yin, S.; Gao, W. Multimodal soft robotic actuation and locomotion. Advanced Materials 2024, 2308829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Wu, C.; Wang, X. Design, control, and experiments of a fluidic soft robotic eel. Smart Materials and Structures 2021, 30, 065001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.Q. Evaluation on swimming efficiency of an eel-inspired soft robot with partially damaged body. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft); 2021; pp. 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, R.; Gong, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, T.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qi, P. Bionic body wave control for an eel-like robot based on segmented soft actuator array. In Proceedings of the 2021 40th Chinese Control Conference (CCC); 2021; pp. 4261–4266. [Google Scholar]

- Cervera-Torralba, J.; Kang, Y.; Khan, E.M.; Adibnazari, I.; Tolley, M.T. Lost-Core Injection Molding of Fluidic Elastomer Actuators for the Fabrication of a Modular Eel-Inspired Soft Robot. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft); 2024; pp. 971–976. [Google Scholar]

- Sayahkarajy, M.; Witte, H. Analysis of Robot–Environment Interaction Modes in Anguilliform Locomotion of a New Soft Eel Robot. In Proceedings of the Actuators; 2024; p. 406. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, P.J. Dynamic mode decomposition of numerical and experimental data. Journal of fluid mechanics 2010, 656, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.J.J.A.R.o.F.M. Dynamic mode decomposition and its variants. 2022, 54, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, S.L.; Proctor, J.L.; Kutz, J.N. Discovering governing equations from data by sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2016, 113, 3932–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Silva, B.M.; Champion, K.; Quade, M.; Loiseau, J.-C.; Kutz, J.N.; Brunton, S.L. Pysindy: a python package for the sparse identification of nonlinear dynamics from data. arXiv preprint arXiv:.08424 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptanoglu, A.A.; de Silva, B.M.; Fasel, U.; Kaheman, K.; Goldschmidt, A.J.; Callaham, J.L.; Delahunt, C.B.; Nicolaou, Z.G.; Champion, K.; Loiseau, J.-C. PySINDy: A comprehensive Python package for robust sparse system identification. arXiv preprint arXiv:.08481 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).