1. Introduction

Cereal crops are most commonly farmed in Ethiopia’s highlands. Besides, in Ethiopia’s highlands, malted barley is a major source of income for small-scale farmers when compared with other cereal crops (Ministry of Agriculture, MoA, 2018). Compared to food barley, Ethiopia produces relatively little malting barley (15%), despite having a favorable climate and prospective markets (Ferede & Demsie, 2020). The use of low-yielding cultivars is one factor contributing to low productivity (Bizuneh & Abebe, 2019). Thus, increasing malt and barley production in an agroecological mass production package utilizing varieties, fertilizer, and pure seed will be beneficial (Bizuneh & Abebe, 2019).

Depending on the level of sophistication in agricultural production, crops, and the environment, a country’s complete seed supply may come from a variety of sources, such as off-farm sources from commercial sources or local trading, or it may come from on-farm savings made by the farmer (Bishaw & Tiruneh, 2020). The commercial purpose production is supported by different farmers.

There are farmers who do-and do not belong to primary cooperatives (PCs). In a marketing links, smallholders who do not belong to primary cooperatives (PCs) sell to private merchants. However, PCs sell to dealers directly or through a Federal Cooperative Union (FCU) to brewers. Hence, brewers, melters, and wholesale dealers are potential buyers of FCUs (Ukaid, 2018).

The Amhara region’s malt barley crop output yield is influenced by the seed system. A seed system is an assembly of activities that facilitate variety development, seed production, and farmer distribution. All three seed systems formal, semi-formal (farmers used both formal and informal seed systems), and informal are utilized in the Amhara region. Institutional and market failures provide major growth obstacles at the research site. The problem lies in the fact that farmers might duplicate enhanced seeds without the assistance of breeders, so reducing the quality and yield of the seeds. Cooperatives predominate in the south Gondar and Awi zones when public organizations, as in many industrialized nations, play a key position in the seed system or when nations transition from a public-led system to one that contains a more complicated collection of agents, as in many emerging nations.

The seed system is the interaction between supply and demand that results in the use of seeds at the farm level. In essence, the seed system is a social and economic process that combines farmers’ needs for seeds and the important characteristics they carry with many possible sources of supply (FAO, 2004). The system includes both traditional (and informal) and non-traditional (formal or commercial) seed systems. The legal framework, which includes things like variety release protocols, intellectual property rights, certification programs, seed standards, contract regulations, and law enforcement, is an essential component of the seed system in the Amhara region. Consistent with the results of this study (Maredia et al., 1999) examined the quantity, quality, and cost of seeds flowing through a seed system.

Although the seed system was created more than 50 years ago to use enhanced seeds to boost agricultural output and enhance food security, its uptake has been somewhat slow. Evidence suggests that, as in sub-Saharan Africa, 95% of the seeds planted are kept, chosen, and traded among farmers themselves (Bishaw & Tiruneh, 2020). Farmers frequently aren’t able to receive benefit from modern advancements because of this persistent reliance on unofficial local seed networks, even though they are essential to maintaining biodiversity and cultivar improvement.

In the Ethiopian contexts, the seed system is significantly influenced by the role of institutions. Thus, several institutions are involved in the malt-barley seed system. However, access to improved seeds has some limitations. It can be attributed to resources. There is resource wastage due to duties being overlapped, gaps in, and repeated efforts by different institutions (Kebede et al., 2017).

Except the small amount produced by farmers who grow seed and the seed brokers’ supply, the Amhara region’s malt barley seed supply system shows that all seed materials come from general crop production rather than crops developed specifically for seed.

The first nation to formally adopt the Pluralistic Seed System Development approach was Ethiopia. PSSDS in 2017 (MoA, 2019). as a substitute for the commonly employed formal seed system development or linear approach. Policymakers and people with agricultural backgrounds can share this information. As a result, the farmer can stop the crop from degrading, and strategies can be created based on expected outcomes. Sustainable agriculture needs seeds, improved crop types, and other agricultural inputs to turn subsistence farming into a profitable industry. Between 2009 and 2013, farmers in Ethiopia received over 1932.1 tons of seeds from seed companies, covering 77,080 hectares of land (CTA, 2014).

To this end, the study seeks to address twofold questions: Q1: What are the malt barley informal seed systems under probable environmental circumstances in the southern Gondar and Awi administrative zones. Q2: What is the performance of cultivating farmers’ malting barley in terms of seed productivity? Therefore, the current study aimed to assess informal malt barely seed system and the roles of the different actors and to provide policy suggestions to make the system more relevant to small-scale farmers.

2. Description of the Study Area

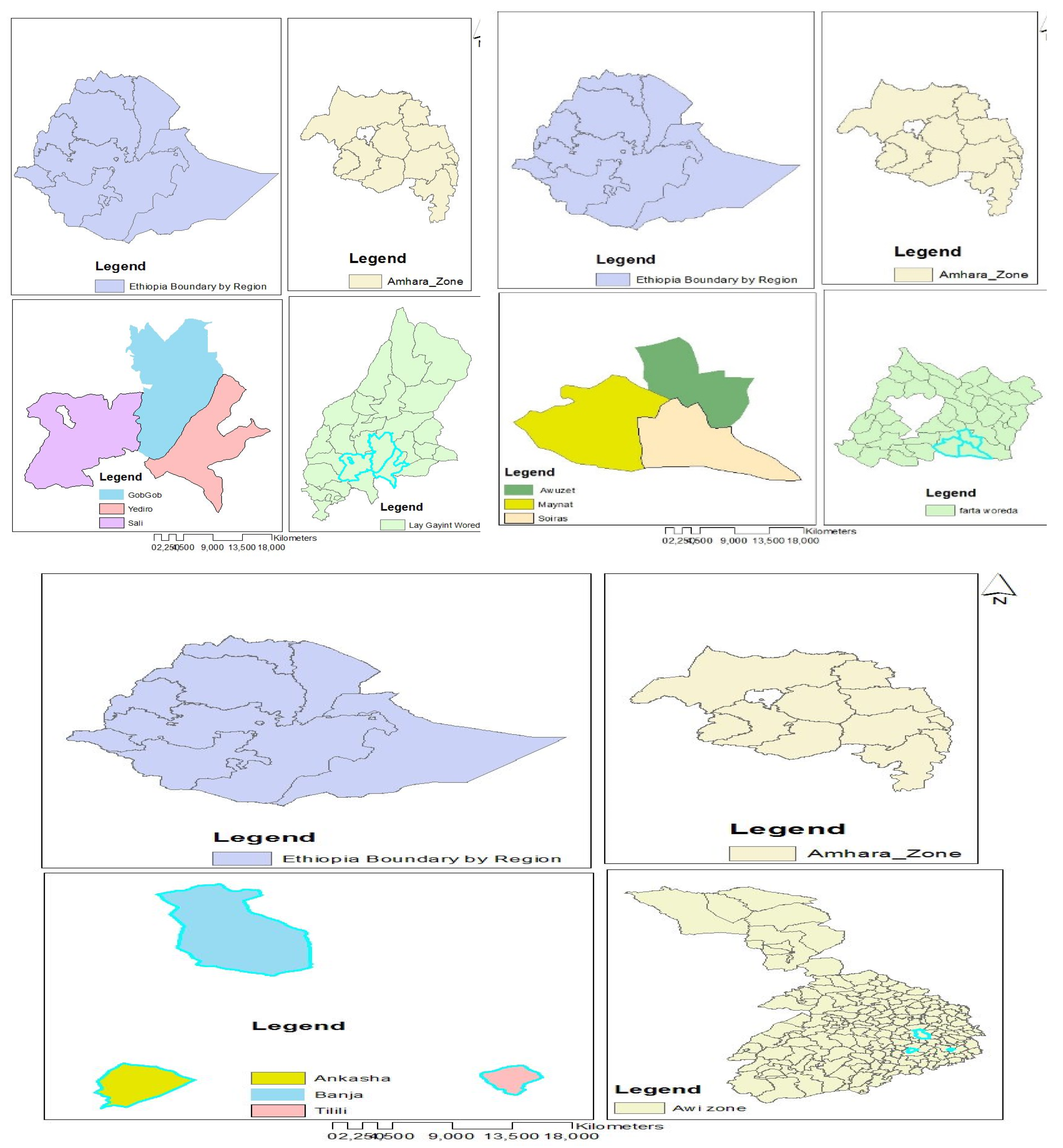

The research was carried out in the 2021 cropping season in three districts of each two zones of Awi and south Gondar such as Banja, Guagusa Shikudad, and Ankesha in the Awi zone, and Farta, Lay Gayint, and Estie in the South Gondar zone (

Figure 1). Two zones of Awi and south Gondar situated in a temperate ecosystem in northwest part of Ethiopia are the primary sites for the cultivation of malt barley. These are divided into different agroclimatic zones: Bereha, Kolla, Woina Dega, Dega, Kur, and wurch agroclimatic zones of Awi zone and Kola “Dega, wurch, and Woina dega agroclimatic zones of south Gondar zone. In the South Gondar zone, the average annual temperature is roughly 15.94 °C, with a range of 8.425 °C to 23.4580 °C at the highest. The average annual rainfall is 1599.4 mm, with significant year-to-year variance. Rainfall occurs in two distinct seasons: the short-wet season occurs from March to April, while the long rainy season spans from June to September. To determine the effects of the malt barley seed source and the difficulties being experienced in the research area surveys and laboratory testing were done.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey and Sampling

Farmers served as the sampling units through the process of snowball random sampling. Sampling was carried out descending from higher to lower administrative levels, as follows. First, one primary region was selected out of all the malt barley growing regions, and in this region, two major zones (Awi and South Gondar) were chosen at random. The selection probability was determined by the area where malt barley was planted.

In the second stage, districts were randomly chosen from among all districts deemed to be the main cultivated malt barley production districts within each of the two selected zones.

Thirdly, three enumeration areas were arbitrarily chosen within each of the districts that were chosen, taking into account the area that was planted malt barley in each area.

In the last stage, based on the list of farmers from peasant associations (PAs), villages and malt barley farmers were randomly chosen within the enumeration areas. At least 40 farmers were questioned in each village. Two peasant associations (PAs) that grow malt barley from each district were chosen for this investigation. Out of the three PAs, 120 respondents, or farming households, were chosen at random (Taro, 1967). The study used a statistical procedure to ascertain the sample size for every kebele. The following formula was used to determine the total sample size for each of the three kebeles using the probability proportional to the size method:

sWhere, n= the total sample size

N= represents total households /population/ of each kebele

e2= margin of error = (0.05 when the confidence level is 95%)

The list of registered households was obtained from the representative kebele administrations and local development agents. Households were obtained from these samples using a systematic random sampling method.

A structured interview schedule was used to gather the main data from the sampled households that were required for the quantitative analysis. Data was gathered in 2022 between April and June. However, a number of preliminary actions were carried out prior to the actual data gathering. First, enumerators familiar with the customs and culture of each sample PAs were selected, trained, and tasked with gathering data by the questionnaire and in an appropriate manner. The training covered how to approach and interview respondents, the goal and substance of the questionnaire, and how to use the questionnaire to collect data. Before performing the official survey, 10 randomly selected farm households from each PAs were given a pre-test copy of the interview schedule. Based on the pretest input, necessary changes were done. Together with each district subject matter and three development agents (DAs) who were more knowledgeable and experienced in the study area’s farming system and farmers’-based malt barley seed production, the researcher collected the data. At the end of each day, the researcher went to examine the results with each enumerator. The enumerators reviewed each questionnaire and provided clarifications as needed.

The primary information gathered from concerned farmers’ sources of seed, their choices for seeds, their methods for managing seeds, how they saw and used different varieties, their understanding of resources for information on agricultural technologies, distribution, protection, production, use, harvesting, and marketing.

Secondary data were gathered from various sources, including records and reports of the Kebele and district office of Agriculture, Regional Agricultural Research Institutes, Agricultural Transformation Institute (ATI), Ethiopian Standard Authority, and Ethiopian Seed Businesses, to fill in information gaps and supplement primary data (data from the farmer and cooperatives farmer seed business group, and local seed business).

3.2. Seed Sampling and Testing

In the study area, seed samples of each type were gathered from each PA’s growing malt barley. Following the collection of 24 samples in total, 1000 g of the submitted samples of the various types were gathered for quality examination by ISTA protocol. Tolerance levels were assessed and all tests were carried out in compliance with ISTA regulations (ISTA, 1996). The Gondar, Brazil, seed science laboratories examined the physiological quality and moisture content of the seeds.

A 600 g working sample of seeds from each seed source was used for the laboratory tests. The working samples were separated into pure seeds and inert materials.

For the standard Germination (SG) test three replicates containing 100 seeds were sown in sanitized sand media. From the pure seed component, 400 seeds were extracted and split into four repetitions, each containing one hundred seeds. Following sowing, the seeds were put in a germination chamber at 18oC for 16 hours in the dark and at 25oC for eight hours in the presence of light (ISTA, 1996). Ten days after planting, seedlings were analyzed to determine if they were abnormal or normal, as well as dead (ungerminated) seeds. Based on the final count, the corresponding percentages of the two groups of seedlings were computed (ISTA, 1996).

Following the final count in the conventional germination test, the lengths of seedling and roots, were assessed. Each experimental replication involved the measurement of 10 randomly selected healthy seedlings. From the site of attachment to the tip of the seedling, the shoot length was measured. Similarly, the length of the root was measured from its place of attachment to its tip. The average shoot or root length was determined by dividing the total shoot or root length by the total number of normal seedlings evaluated (Fessel, 2003). The standard germination rate was multiplied by the average of the shoot and root lengths to determine seedling vigor index I.

Similarly, seedling dry weight was determined after the typical germination test’s final count. From each replicate, 10 seedlings were chosen at random and dried for 24 hours at 80 ± 1 °C in an oven. Using a sensitive balance, the dried seedlings that resulted were calculated to the closest decimal place. The standard germination was multiplied by the mean seedling dry weight to determine Vigor Index II (Fessel, 2003).

Using sanitized sand media for germination and CRD design with three replications of three hundred (300) pure seeds, each sample was sown in pots at a rate of one hundred seeds per replicate. In laboratory pots, the proportion and rate of seedling emergence were calculated.

For moisture content determination 10g seed sample was taken and spread evenly across the surface of a 10-cm-diameter container and then oven-dried for about 17 hours at 103±2oC. They were then covered and cooled for 30 to 45 minutes in desiccators.

3.3. Data Analysis

Various analytical methods were applied to the gathered data according to their type. The focus groups, key informants, sample farmers, and other pertinent sources provided the data. The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Version 24) was used to calculate the mean, standard deviation, frequency of occurrence, and percentage to define and compare various sample unit categories about the desired features. During the survey, seed samples from various seed suppliers and types were employed as treatments for laboratory analysis. In the CRD design, treatments were arranged for laboratory experiments. The Statistical Analysis R soft war was used to analyze variance (ANOVA) on the physiological quality data. The Least Significance Difference (LSD) method was used to distinguish the treatment means. To find out how closely vigor and seedling emergence are related, correlation coefficient analysis was used.

4. Results

4.1. Seed System Survey Findings

In the study areas, smallholder farmers and development practitioners had limited knowledge of community seed production, marketing, enterprise growth, and management. The training covered various topics, including introducing enhanced seed technologies (production, processing, storage, marketing, quality assurance, sustainability, and management of farmer-based seed enterprises) and enhanced malt barley technologies (better varieties and integrated crop management).

Household factors such as sex, age, family size, degree of education, farming experience, and access to extension services are crucial for the seed and quality production of malt barley. Based on the information that is displayed in (

Table 1) below, the percentage of female heads made up roughly 20.23% of the sample as a whole in Awi and 16.46% in the south Gondar zone (

Table 1).

The head of the home had an average age of 47.6 years, with a range of 20 to 75 years (

Table 2). With only a few years of experience in the irrigated production method in the Awi zone, malt barley production averaged 20 years during the main season.

4.2. Social Capital Linkage and NGOs’ Role in Seed Support

In the research areas, several social clubs were present and the farmers took part in holding leadership and membership rolls (

Table 3). Seventy-one percent of the respondents said they had joined multipurpose cooperatives to receive household goods and agricultural input. Cooperatives also give their agricultural produce market access. Women’s associations, cooperatives for seed production and selling,

The majority of seeds production in the research area, estimated at 60% of the region, is malt barley (10%) and wheat (50%). Additionally, it contains 20% of potatoes and 20% of other crops. In the past, we have grown our malt barley crop using seeds that we saved from our yields and even purchased from neighbors. But in terms of yield, this kind of seed source is never sufficient. Gunna Union and One Acre Fund are already receiving yields that we could only have imagined in the past thanks to the recently produced seed types and the training offered by the Agriculture Office. They are also equally well-trained in manufacturing high-quality seeds for the upcoming cropping seasons.

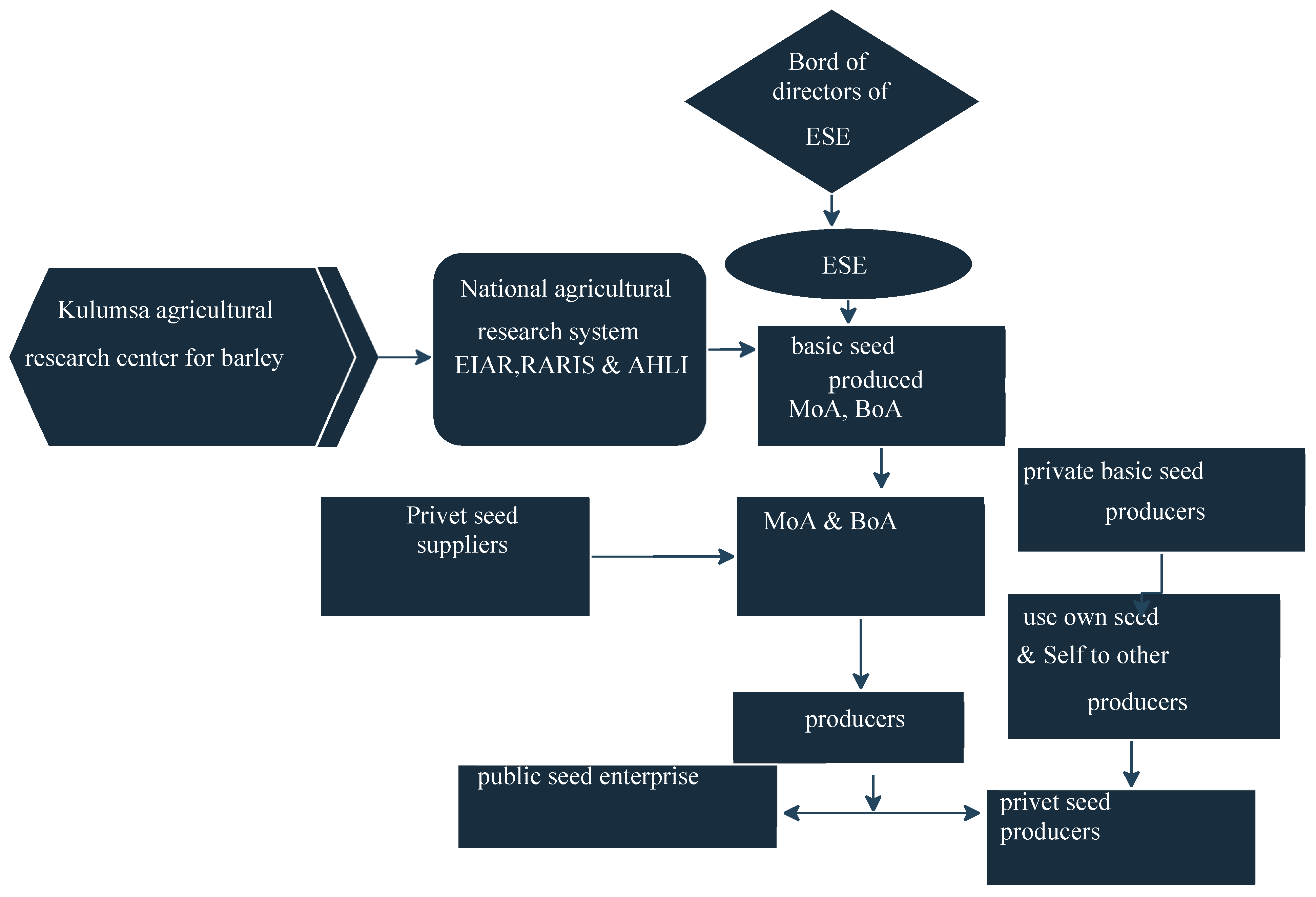

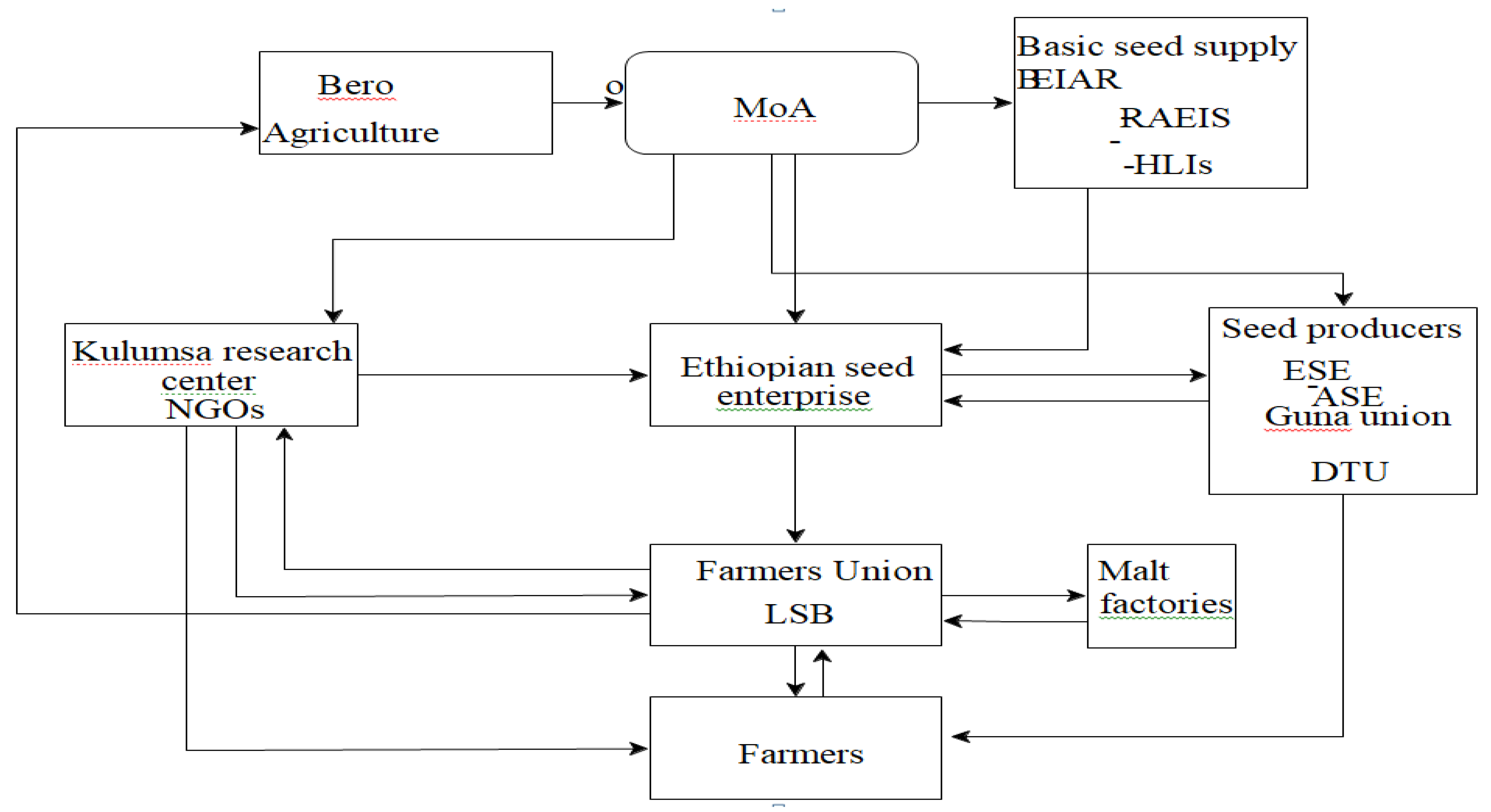

Figure 2.

Ethiopian malt barley distribution and basic seed production actors and links.

Figure 2.

Ethiopian malt barley distribution and basic seed production actors and links.

4.3. Seed Management and Producing Practice

Nearly half (48.47%) of farmers expressed a desire to choose seed colour, 7.38% early maturity, 15.23% seed size, 21.42% marketability, and 5.3% uniformity (

Table 4). Overall, this study is comparable to that (Ariga et al., 2019), who found that the main factor limiting improved varieties’ output across Ethiopia’s agro-ecologies is poor crop management. If farmers do not properly control crop pests (weeds, diseases, and insects), the reduction of production is accompanied by a decrease in seed quality both in the field and in storage.

Most of the local farmers used oxen to plough 75%, 19%, and 5% of the cultivable area three times, twice, and once, respectively, to ensure that the field was ready for sowing based on the basic data. Row and broadcasting are the most widely utilized sowing techniques, with local farmers using them at rates of 15% and 85%, respectively. Local farmers in the study region kept seeds dry by practicing keeping them in airtight containers like sacs and Gotera.

Households in the southern Gondar zone engage in seed selection using the mass, bulk, and pure line methods. Before harvest, sorting of grains from seeds is done by all household members males, females, males and females, and children. By removing discolored seeds, this lowers the amount of contamination by specific seed-borne fungi and improves seed germination. According to the basic data, white color, medium size, and early maturity are considered favorable seed traits that are set by the farmer (

Table 4). They trade pure seeds from farmers with farmers in their neighborhood in addition to farmers who do seed selection. The basic parameter for seed selection of the farmer is seed color,seed size and marketability (48.47%, 1523% and 21.42%) respectively

Table 4.

4.4. Ethiopian Malt Barley Distribution and Basic Seed Production Actors and Links

In Ethiopia, the official malt barley seed system is designed to ensure the production and distribution of high-quality seeds to farmers. The system involves several key stages, each with specific functions and responsibilities. While the exact flow charts might vary slightly based on updates and regional adaptations, the general process typically follows these stages: Agricultural research institutions, such as the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), develop and test new malt barley varieties. The best-performing varieties are produced as foundation seeds by specialized seed producers (

Figure 2). Seed producers who grow Foundation Seeds to produce certified seeds. This stage is crucial for maintaining seed quality and adherence to standards. Certified seeds are inspected by the Ethiopian Seed Council or relevant authorities to ensure they meet quality standards. This includes checking seed purity, germination rates, and other quality parameters. Once seeds pass inspection, they are officially certified and labeled for sale. Certified seeds are distributed through various channels, including government agencies, private seed companies, and cooperatives. Farmers purchase certified seeds from these distribution points for planting as shown in (

Figure 2).

These stages ensure that malt barley seeds are of high quality and suitable for the Ethiopian agricultural context. For specific flow charts and detailed procedures, the Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture or the Ethiopian Seed Council, as they provide official guidelines and documents related to the seed system

4.5. Quality Performance of Malt Barley Seeds from Different Seed Sources

The majority of the seeds gathered from farmers and their cooperatives in two zones of the same type in this study met Ethiopia’s moisture standards (below 13.5%), according to a moisture content analysis (

Table 5). However, there was highly significant variation in seed moisture content (

p ≤ 0.001). The farmers’ own saved seeds of ‘Holker’ had the highest seed moisture content (17.35%), while ‘Travler’ had the lowest seed moisture level (11.35%).

The farmer-collected malt barley seed samples’ standard germination (SG) ranged from 89 (variety ’Holker’) to 98%. The average germination rate for all seeds was 92.63%, falling within the national seed requirement for Ethiopia. Cultivars Fatina and travellers exhibited a higher significant difference (P≤0.01%) in vigor index I than cultivars Ibon and Holker.

The nine batches of malt barley types were divided into distinct vigor levels using germination speed vigour assays (

Table 5). The batch classification, however, ranged from low vigor to intermediate.

In this research, the emergency barley had a highly significant effect (P≤0.01%) in a controlled laboratory setting where a higher proportion of travellers (94.5%) and Ibon (96.5%) were present. The farmers’ Ibon variety had the longest shoot (1.8 cm), and the Travller variety, had the longest roots (4.5 cm). The Fatina variety, which was obtained from farmers, had the shortest shoot and root lengths (0.35 cm and 0.85 cm, respectively). There was a noteworthy variation in vigor index 1. Because of the low root length that was obtained from farmers’ own saved seeds, the Holker variety (16.24) had the lowest vigor index1, while the Fatina variety (22.05) had the highest. There were notable variations in the dry weight of the seedlings between the seed samples.

5. Discussion

5.1. Formal Seed Suppliers and Distribution System

The Federal Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), regional agricultural research institutes (such as the Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institute (ARARI), the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), a regional Bureau of Agriculture (BoA), and an extension system at the zonal, district, and kebele levels. The primary partners carrying out the production in their respective target regions were Kulumsa ARCs from EIAR, Adet, Gonder, and Sirinka ARCs from ARARI; these PSEs included regional public seed enterprises (PSEs) like Amhara Seed Enterprise (ASE), LSB, Guna union, and One-acre fund, as well as Federal Ethiopian Seed Enterprise (ESE). Three seed producers and marketing cooperatives; six farmers’ cooperative unions; regional seed regulatory and quality control and quarantine agencies of respective Regions; farmers in Agricultural Growth Programme (AGP); and Productivity Safety Net Programme (PSNP) districts are examples of private seed producers, farmers’ cooperative unions, and associations. Asella and Gonder malt factories; breweries like Dashen, Habesha, Heineken, Meta, and Raya; and development NGOs working in study locations, such as Agricultural Transformation Institute (ATI), Integrated Seed Sector Development-Ethiopia, and ICARDA-Austrian Development Agency project, were involved in promoting and scaling improved technologies. Farmers were engaged as the primary actors in the seed industry, hosting demonstrations, producing, and marketing seeds. The formal seed system (Bishaw, 2004), is made up of institutional and organizational frameworks that include all businesses and organizations engaged in the transfer of contemporary varieties from agricultural research to farming communities. This analysis is most similar to that report.

5.2. Informal Seed System

The Amhara region’s malt barley seed flow is mostly composed of three systems: integrated, informal, and formal. Farmers connected to programs and formal sector institutions, as well as farmer-to-farmer seed exchanges, have improved seed production and technology scaling up to serve a larger number of farmers in the southern Gondar and Awi zones. This is one method for spreading technology among farmers who are smallholders. While not all partner agricultural research centers and agricultural development agents in each target district have complete tracking, the project’s accomplishments demonstrate that a farmer-to-farmer seed exchange system produces certified/quality malt barley seeds. Seeds for specialized markets are still produced and marketed by the private sector, which ranges from small, medium, and big seed firms to lone seed producers and marketers (Berhanu et al., 2005). A growing number of nations are formulating plans to support the pluralistic seed sector.

Of the farmers surveyed, over 90% were aware that the government was the primary supplier of seeds for the Awi and South Gondar zones, with just 10% coming from research centers and non-governmental organizations. The research center provided the majority of the original seed source. The Ethiopian Institute for Agricultural Research (EIAR) and the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) have introduced improved malt barley varieties through the one-acre fund and ORDA projects. These varieties can serve as sources of raw materials to support Ethiopia’s expanding malt market, particularly the beer brewing industry. Working together with farmers in the higher regions of the Amhara, Awi, and S/Gondar zones, six high-yielding and pest-resistant varieties of malt barley Holker, IBON-174, Travller, and the most recent Fatima have been introduced and assessed since 2017. These cultivars have shown a great deal of promise in meeting the rising domestic demand and providing farmers with a diversified range of revenue streams.

Cooperatives for credit and savings, and associations for water users are examples of additional social institutions. Social structures are crucial to enhancing agricultural practices. This study is consistent with research by (Terefe et al., 2018), which found that increased diversity is essential for lucrative and sustainable malt barley production, as well as information on crop responses to agricultural inputs such as N fertilizer rates.

In recent times, farmers have adopted and employed an intriguing extension strategy in an attempt to acquire seeds from seed actors. However, due to several factors, such as delayed delivery, scarcity, distance, transportation access, lack of information, and the farmer’s low income, seeds are scarce and difficult to obtain. The reason the local farmers wish to raise this product is because of its commercial value, even though they trade themselves for high-value crops like Faba beans and purchase crops from other farmers.

Farmers have to make careful decisions about which crops to cultivate based on various factors such as climate, soil type, market demand, and available resources which is similar to the findings of (Central Statistical Agency, CSA, 2020; Bishaw & Tiruneh, 2020). The survey result shows choice of crop can have a significant impact on the success and profitability of the farming operation in line with (MoA, 2018). The seed system plays a crucial role in the production of malt barley, as it directly affects the quality and yield of the crop. This study is consistent with (Kebede et al., 2017; Terefe et al., 2018) which found that increased diversity is essential for lucrative and sustainable malt barley production, as well as information on crop responses to agricultural inputs such N fertilizer rates. The quality of the malt barley seed is vital for obtaining high-quality grains (CTA, 2014).

The seed system should ensure that the seeds have high germination rates, genetic purity, and are free from diseases or contaminants. Seed quality can greatly influence crop establishment, vigor, and overall yield. Similar to (Bishaw, 2004), this study found that farmers may have chosen to save seed from their harvest for planting the next year, which is produced informally, even though they may have embraced a newer variety produced by the formal sector. The choice of proper varieties of malt barley is essential for consistent quality and yield. The seed system should provide farmers with access to a diverse range of suitable barley varieties that are specifically bred for malt production (Bishaw, 2004). These varieties should have desirable traits such as high malt extract, good agronomic performance, disease resistance, and adaptation to local conditions (CSA, 2020). The seed system should ensure that farmers have sufficient access to high-quality malt barley seeds (FAO, 2004). This includes efficient distribution channels, availability of certified or improved seed varieties, and affordable pricing (CTA, 2014). Accessible seed systems are crucial for enabling farmers to adopt improved varieties and technologies positive finding with (Ebone & Gonçalves, 2019). The seed system should have effective mechanisms for seed multiplication to produce sufficient quantities of quality seeds. Similar findings were found in (Andargie, 2021). This involves the production of foundation and certified seeds through controlled environments and strict quality control measures. Regular monitoring and testing of seed lots help ensure accurate labeling, genetic purity, and acceptable quality standards this is in agreement with (Pinto et al., 2015). The seed system should provide necessary training and support to farmers regarding seed selection, handling techniques, and best practices for seed establishment. Educating farmers on the importance of using quality seeds and proper seed management techniques can greatly enhance crop performance and yield, this study is comparable to that of (Kassie &Tesfaye, 2019) who found that the main factor limiting improved varieties’ output across Ethiopia’s agro-ecologies is poor crop management.

The greater individual diversity among seeds from batches with average physiological potential could account for this variation. For most species, including malt barley, batches of medium vigor often exhibit the largest individual variance across seeds within a single batch. The batches are more vigorous when they are more homogeneous. The individual variation among the seeds rises during the determination process. Comparable outcomes were attained by (Fessel, 2003). who discovered that the vigor tests used to assess physiological potential varied in the way different batches of maize seeds performed.

6. Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the impact of the seed system on malt barley production, quality, and nitrogen content in the Amhara region of Ethiopia. It highlights the importance of accessing high-quality seeds through formal channels to enhance crop productivity and brewing quality. Further research in this area can help to develop strategies to improve the seed system and promote sustainable malt barley production in the region.

Crop research, seed production and quality assurance, financing availability and promotion, and capacity building are all heavily reliant on the public sector for the national seed system to evolve in a balanced manner. The formal seed system is a purposefully designed framework that entails a series of steps culminating in genetically enhanced goods, specifically certified seeds from validated cultivars. Plant breeding or a range of development programs that incorporate a structured release and maintenance system are the first steps in the chain.

In addition, in light of the national goal of food self-sufficiency and food security in the nation, national governments have made significant expenditures in crop improvement and seed supply. Nevertheless, little is known about how the formal and unofficial barley industries in each nation operate. To assess the state and effectiveness of the informal seed system, focus groups, key informant interviews, secondary data, and seed samples for quality standards are utilized. The adoption of enhanced malt barley varieties by farmers and their sources were also evaluated in the study. It evaluated seed management techniques, information sources on agricultural technologies, and farmers’ selection criteria for varieties.

Moreover, the adoption of improved malt barley types has been aided by the manufacturing of seeds and raising public awareness. Access to and availability of malted barley varieties are facilitated by farmer-based seed production and marketing. Farmers’ seed samples were gathered, and their physical, physiological, and moisture content were examined and contrasted. The individual varieties differed significantly from one another. The formal and informal sectors’ malt barley seed samples fulfilled the minimal national seed requirement in terms of physical quality.

Overall, the survey results show a well-functioning seed system for malted barley is essential for ensuring a consistent supply of high-quality seeds to farmers. By optimizing seed quality, access, and support, the seed system can contribute to improved yields, profitability, and sustainability in the malt barley industry. Thus, to guarantee long-term sustainability, however, responsible parties need to keep refining their linking agreements with seed cooperative unions. Establishing public-private partnerships with the Federal Ministry of Agriculture, regional agricultural extension bureaus, cooperatives, and union organization agencies, trade and industry bureaus, credit and savings institutions, malt factories and breweries, seed enterprises, and agencies for seed and other input quality control and certification are a few examples of these efforts.

Data availability

Data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Ministry of Education for funding this study, the south Gondar and Awi zone Agricultural Office for providing general information, the Agricultural Offices of the south Gondar and Awi zone agriculture districts for facilitating data collection and providing secondary data, and the farmers who provided primary data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Andargie, Y. E. (2021). Malt barley seed supply system.

- Ariga, J., Mabaya, E., Waithaka, M. & Wanzala-Mlobela, M. (2019). Improved agricultural technologies spur a green revolution in Africa? A multicountry analysis of seed and fertilizer delivery systems. The journal of the International Association of Agricultural Economists. 50, 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, B., Fekadu, A., & Berhane, L., (2005). Food barley in Ethiopia. In: Grando, S., Gomez, H. (Eds.), Food Barley: Importance, Uses and Local Knowledge. Proceedings of the international Workshop on Food Barley Improvement. pp. 53–82, ICARDA, Hammamet.

- Bishaw, Z. (2004). Wheat and Barley Seed Systems in Ethiopia and Syria Systems in Ethiopia and Syria.

- Bishaw, Z. & Tiruneh, A. M. (2020). Deployment of Malt Barley Technologies In Ethiopia Achievements and Lessons Learned. Lebanon: International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA). Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11766/12906.

- Bizuneh,W. F & Abebe, D. A.(2019). Malt Barley (Hordeum distichon L.) varieties performance evaluation in North Shewa, Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 14(8), 503-508. [CrossRef]

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2020). Agricultural Sample Survey. Report on Livestock and Livestock Characteristics. Volume II. Statistical Bulletin 587. Addis Ababa, 9-11.

- CTA. (2014). Seed System, Science and Policy in East and Central Africa. Available online: https://publications.cta.int.

- Ebone, L. A., & Gonçalves, I. M. (2019). Accelerated aging test and image analysis for barley seed, AJCS, 13(09):1546-1551.

- FAO. (2004). Summary of world food and agricultural statistics. Available online: https://www.fao.org/.

- Fessel, S. A. (2003). Avaliação da qualidade física, fisiológica e sanitária de sementes de milho durante o beneficiamento. Revista Brasileira de Sementes, 25(2). 70-76. [CrossRef]

- ISTA. (1996). International Rules for Seed Testing. Seed Science and Technology, 13, 299-513.

- Kassie, M., & Tesfaye, K., (2019). Malting barley grain quality and yield response to nitrogen fertilization in the Arsi highlands of Ethiopia. Journal of Crop Science and Biotechnology, 22 (3), 225–234. [CrossRef]

- Kebede,W. M., Koye, A. D., Mussa, E. C, Daniel T. Kebede,D.T. (2017). The Roles of Institutions for Malt-Barley Production in Smallholder Farming System: The Case of Wegera District, Northwest Ethiopia. International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 7(1): 7-12.

- Maredia, M., Howard, J., Boughton, D., Naseem, A. & Wanzala, M. (1999). Increasing Seed System Efficiency in Africa: Concepts, Strategies and issues. MSU International Development Working Papers 77, Michigan.

- Pinto, C. A. G, Carvalho, M. L. M., Andrade, D. B., Leite, E. R., & Chalfoun, I. (2015). Image analysis in the evaluation of the physiological potential of maize seeds. Rev Cienc Agron. 46:319-328. [CrossRef]

- Taro, Y. (1967). Statistics: An Introductory analysis. Harper and row.

- Terefe, D., Desalegn, T., & Ashagre, H. (2018). Effect of nitrogen fertilizer levels on grain yield and quality of malt barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) varieties at Wolmera District, Central Highland of Ethiopia. Available online: https://www.joseheras.com/.

- Ukaid. (2018). Assessment of the Malting Barley Market System in Ethiopia. Available online: https://beamexchange.org.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).