Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

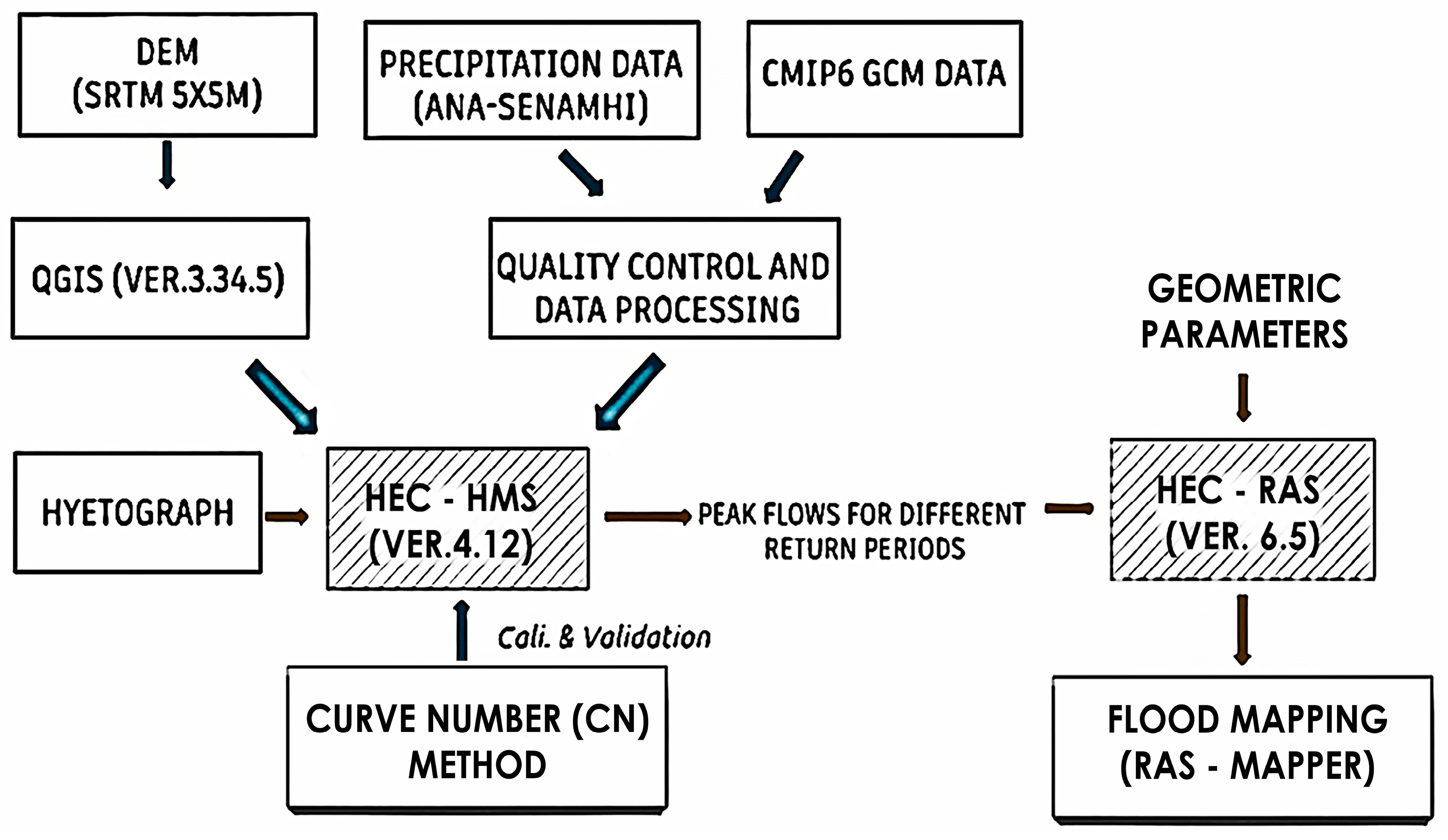

2. Data and Methodology

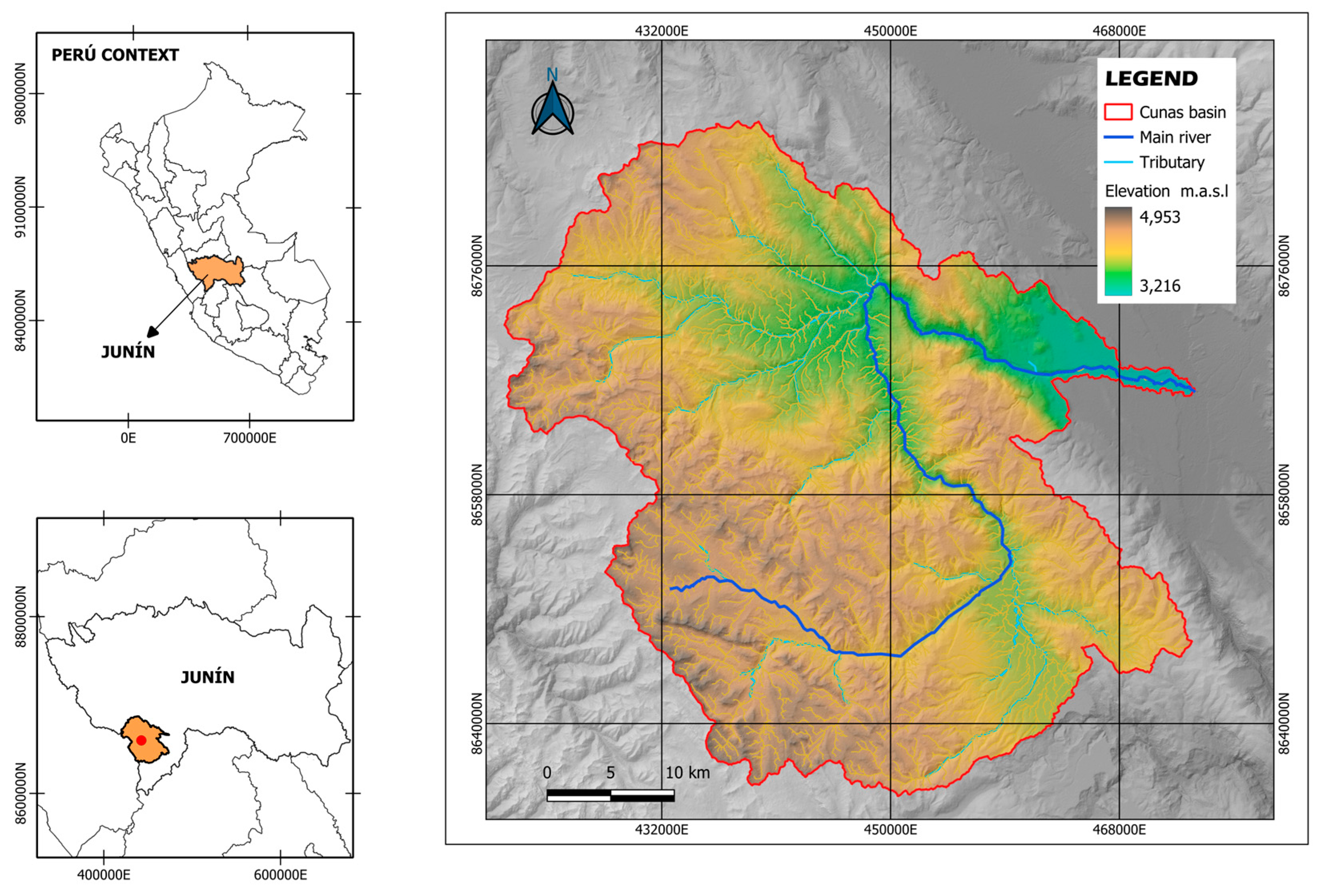

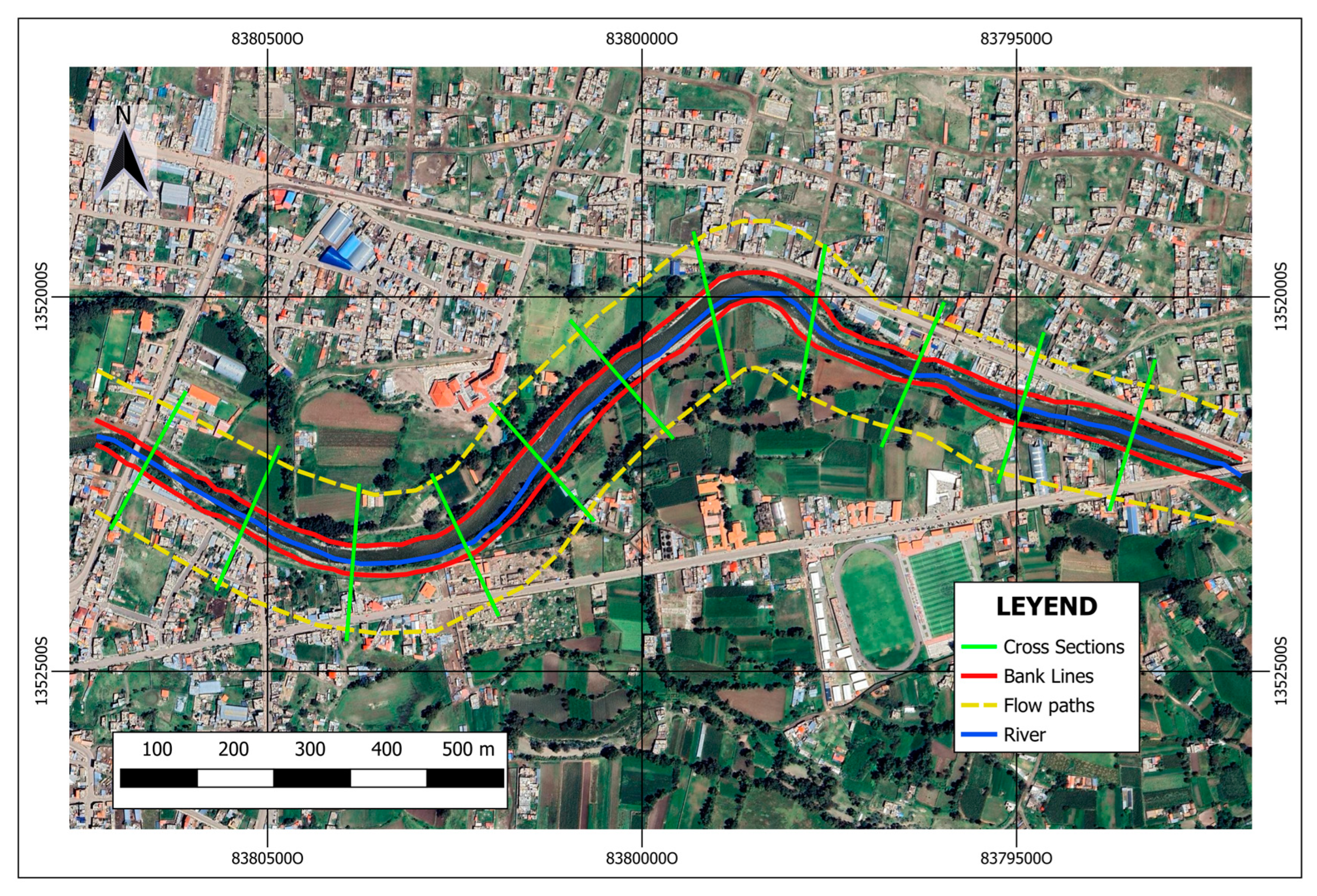

2.1. Study Area

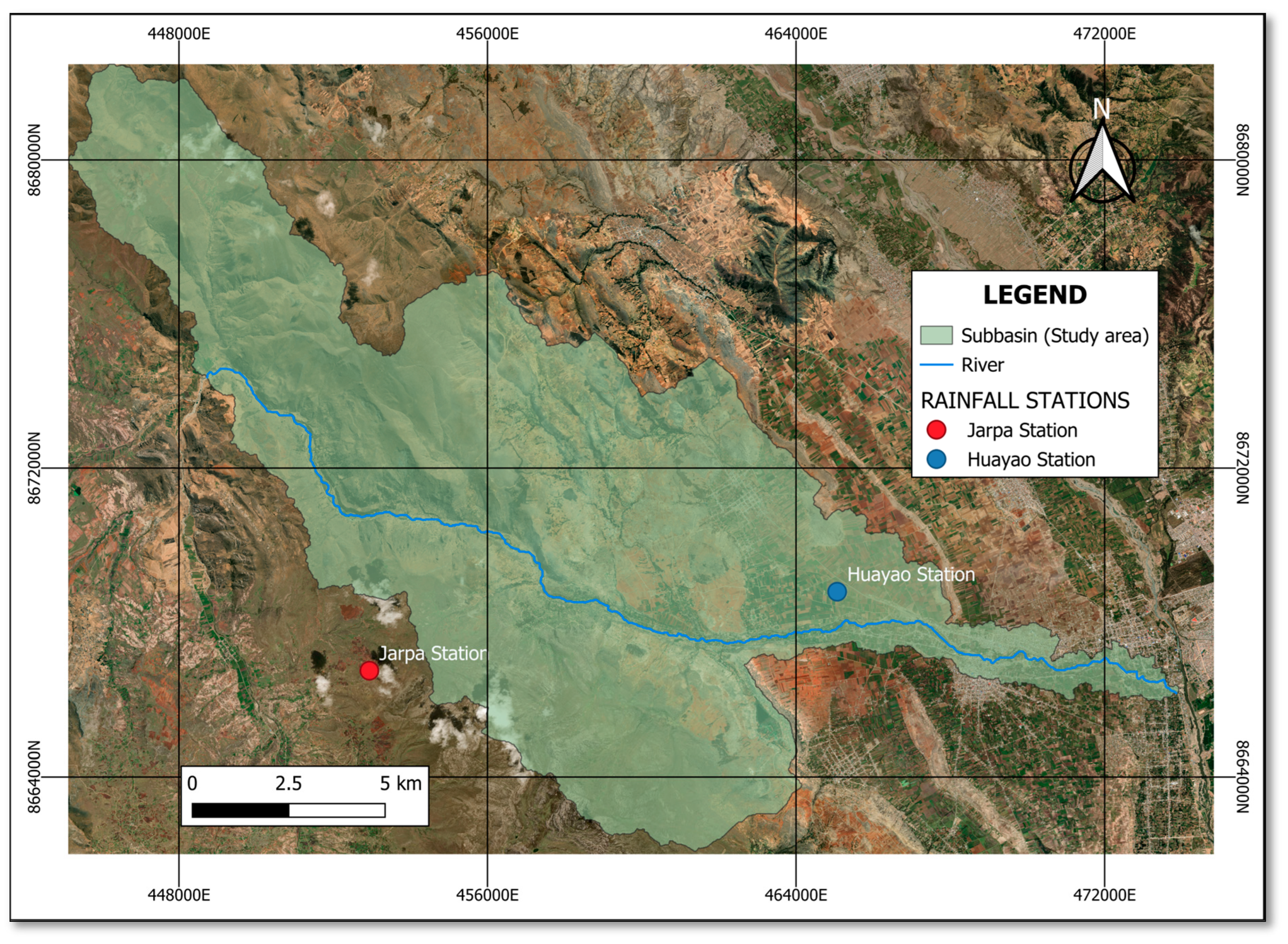

2.2. Area of the Micro-Watersed

2.3. Hydrological Study under Normal Conditions

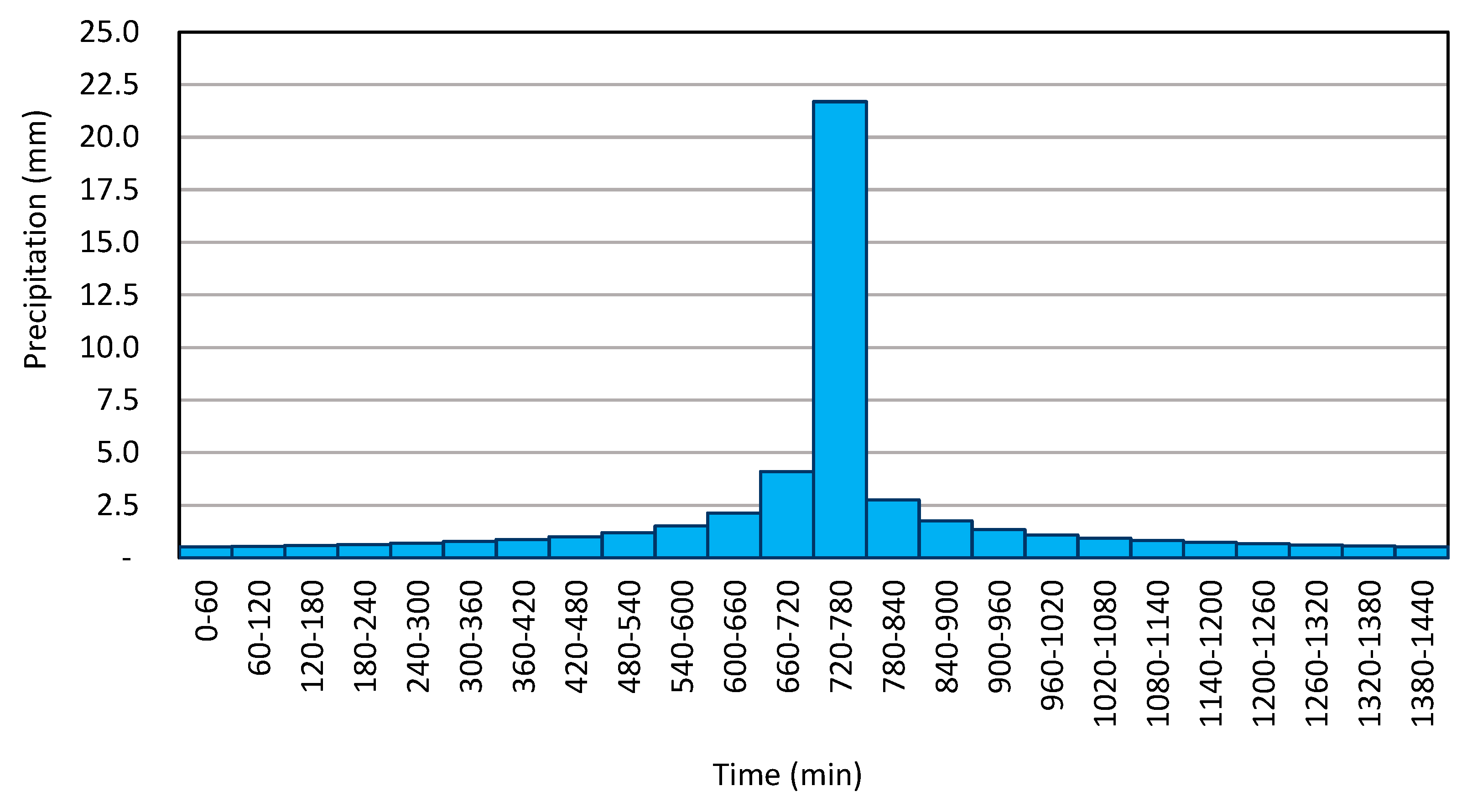

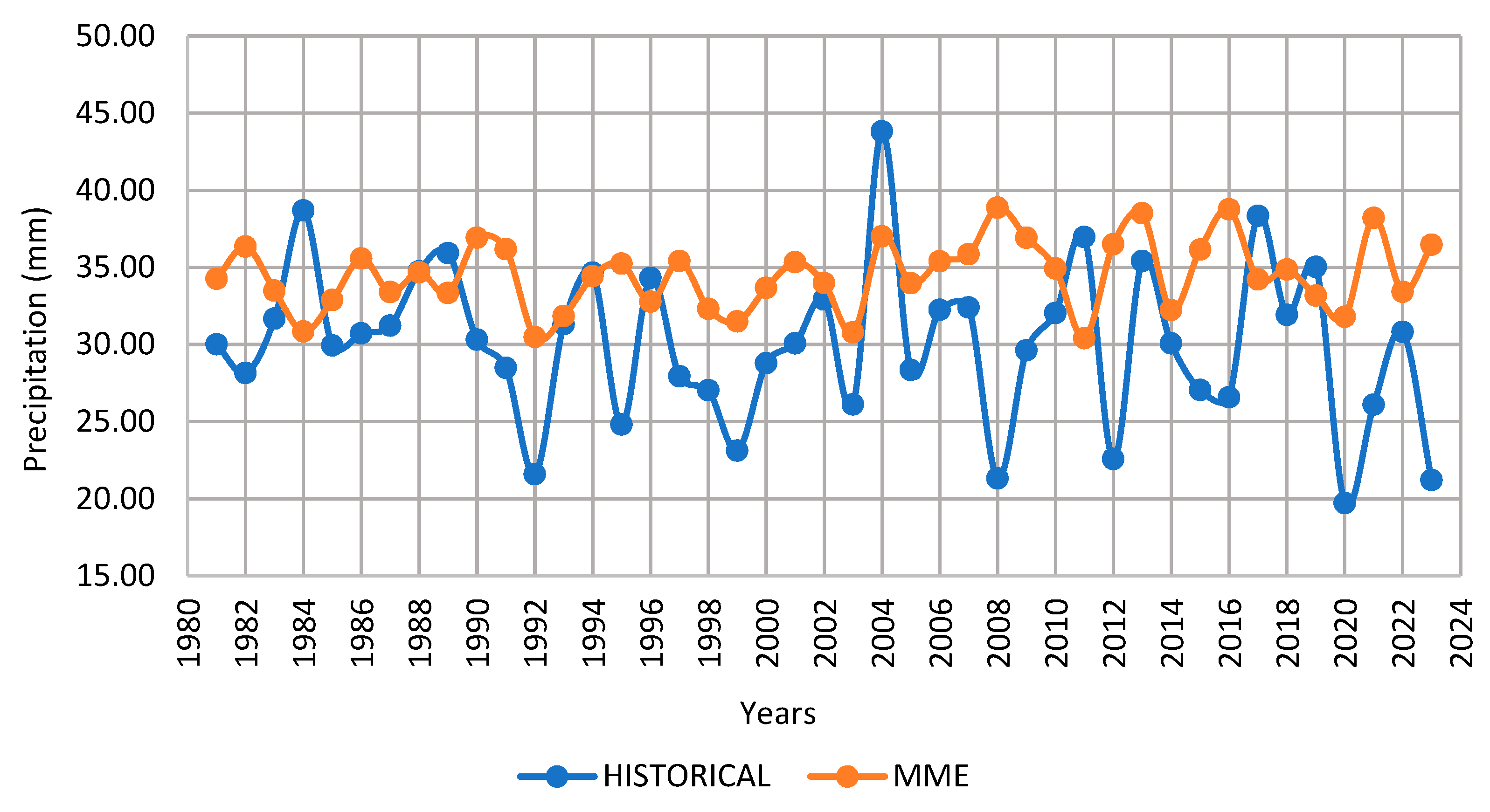

2.3.1. Influence and Analysis of Precipitation

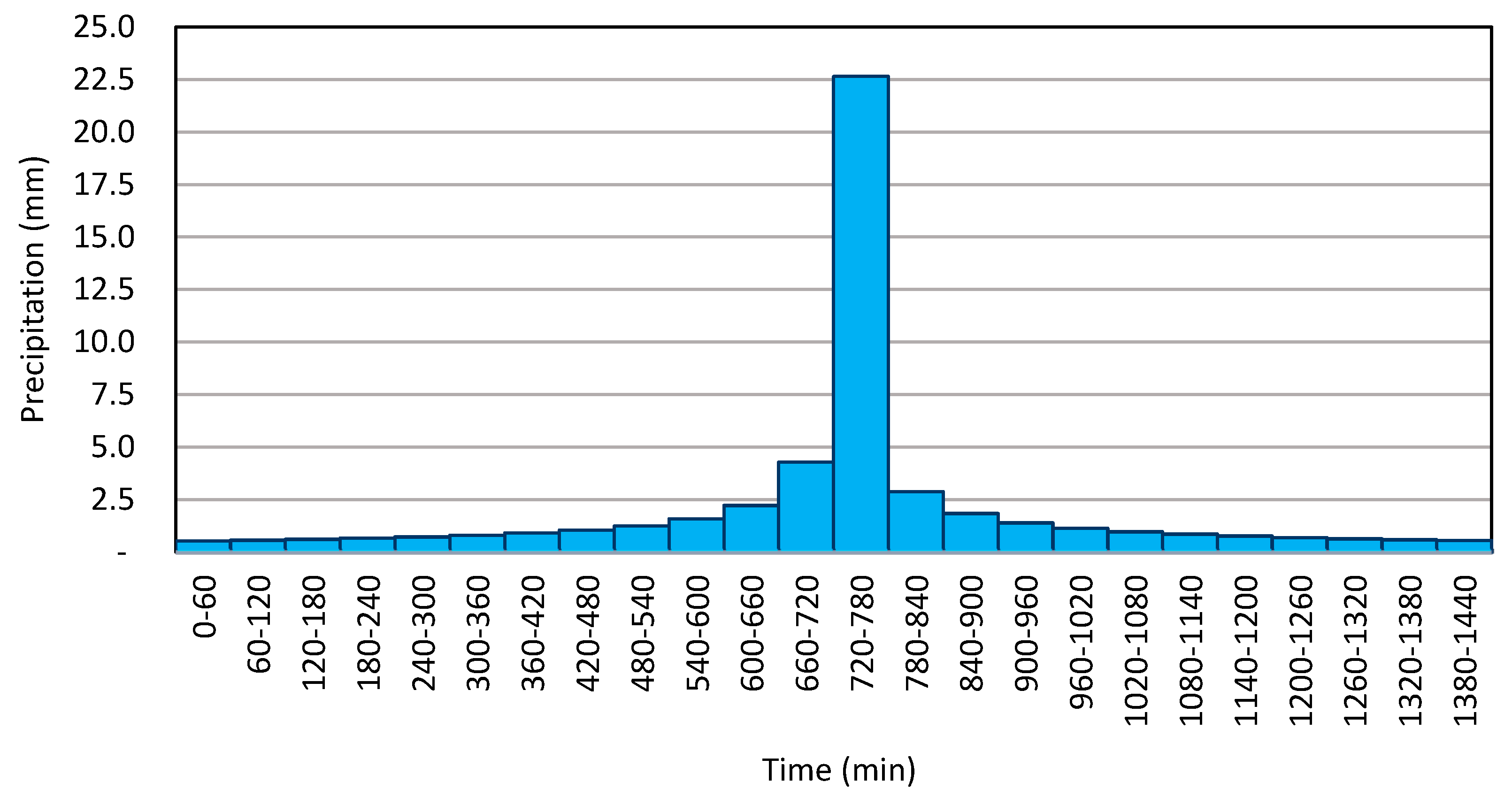

2.3.2. Estimation of Maximum Flow rate (Qmáx) in HEC-HMS

2.3.3. Simulación del Comportamiento del rio Cunas con HEC-RAS

2.4. Hydrological Study with the Presence of Climate Change

2.4.1. Influence and Analysis of Precipitation

2.4.2. Maximum Flow Rate Estimation (Qmáx ) in HEC-HMS and Simulation with HEC-RAS

3. Results

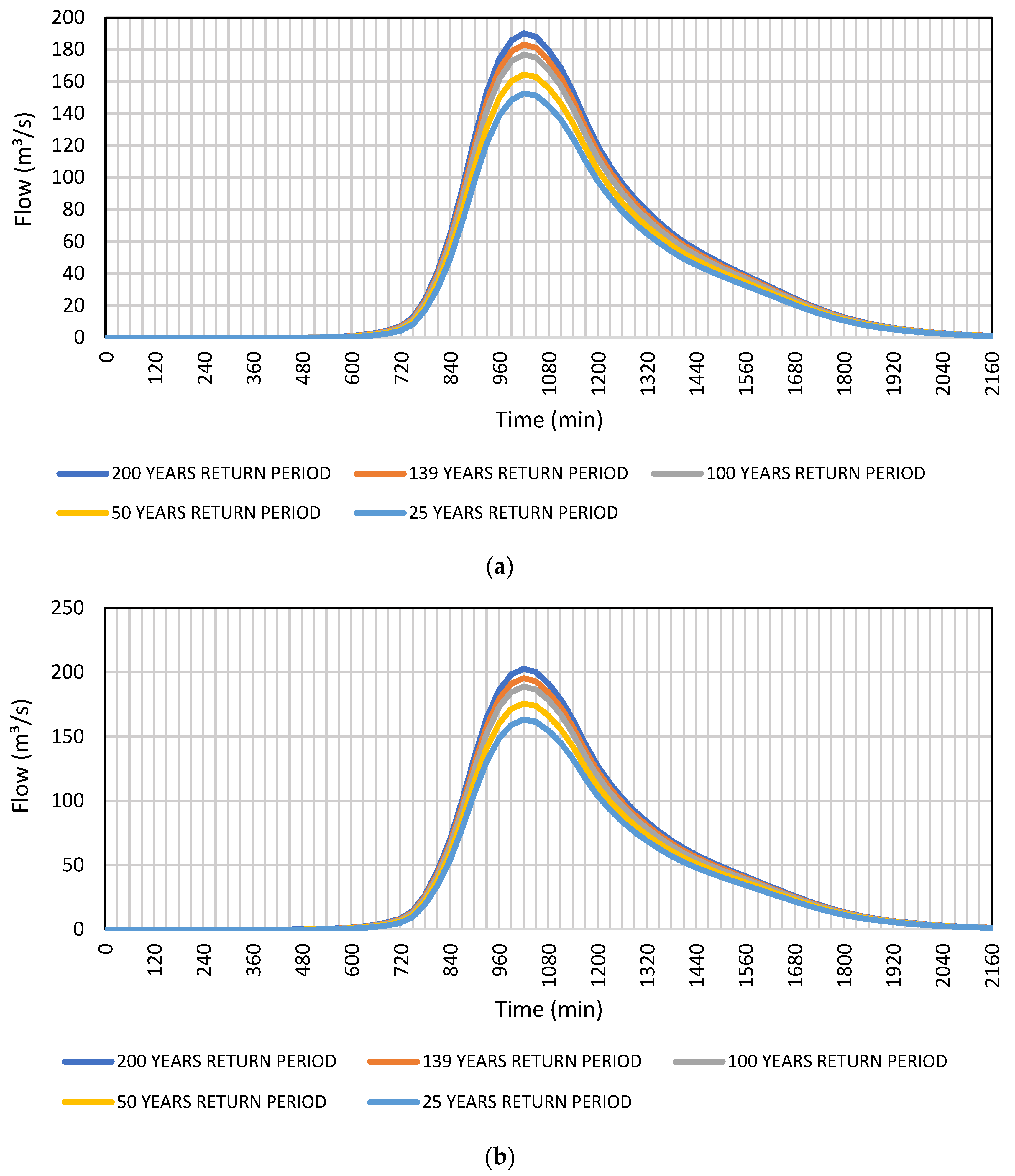

3.1. Calculation of Maximum Design Flow and Volumes Using HEC-HMS

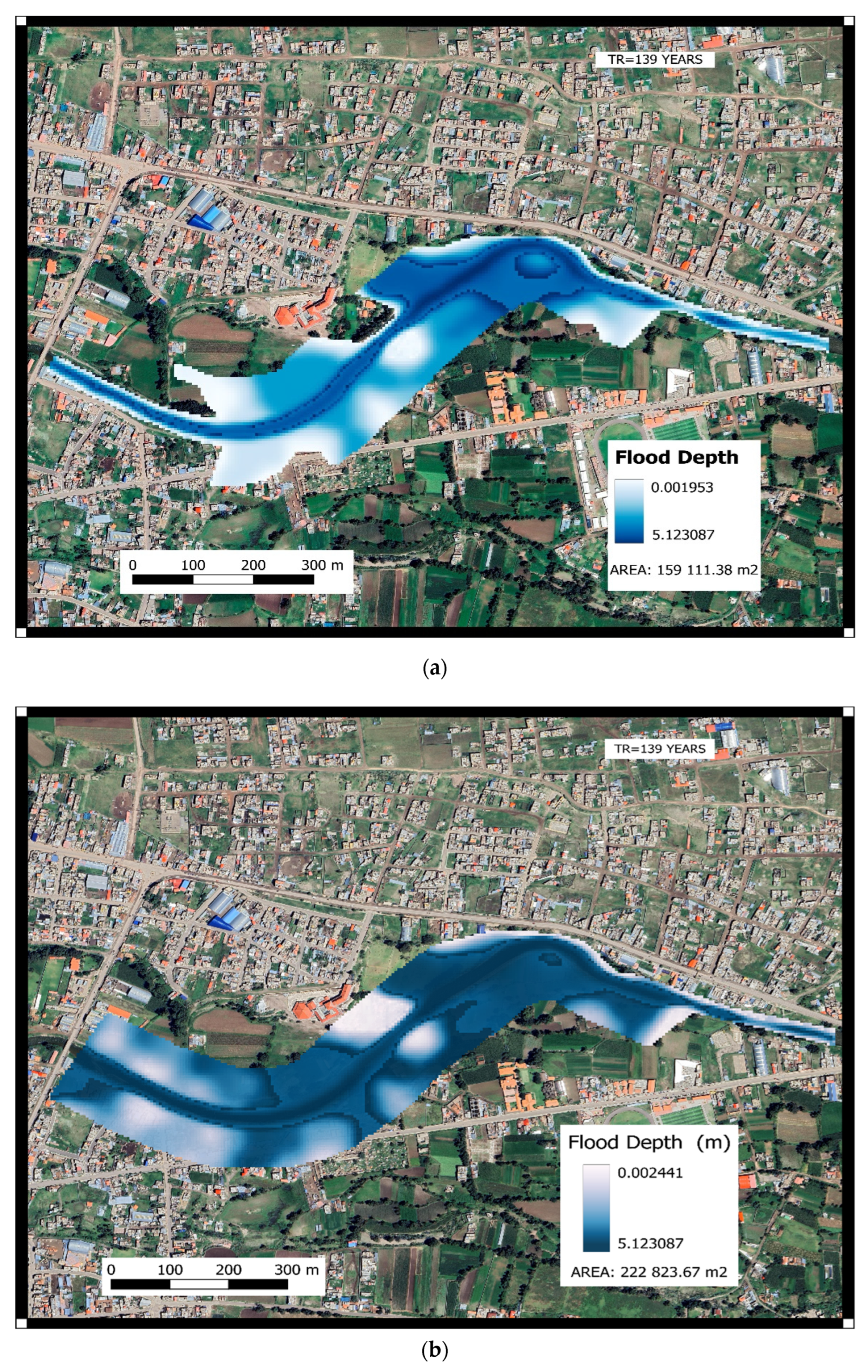

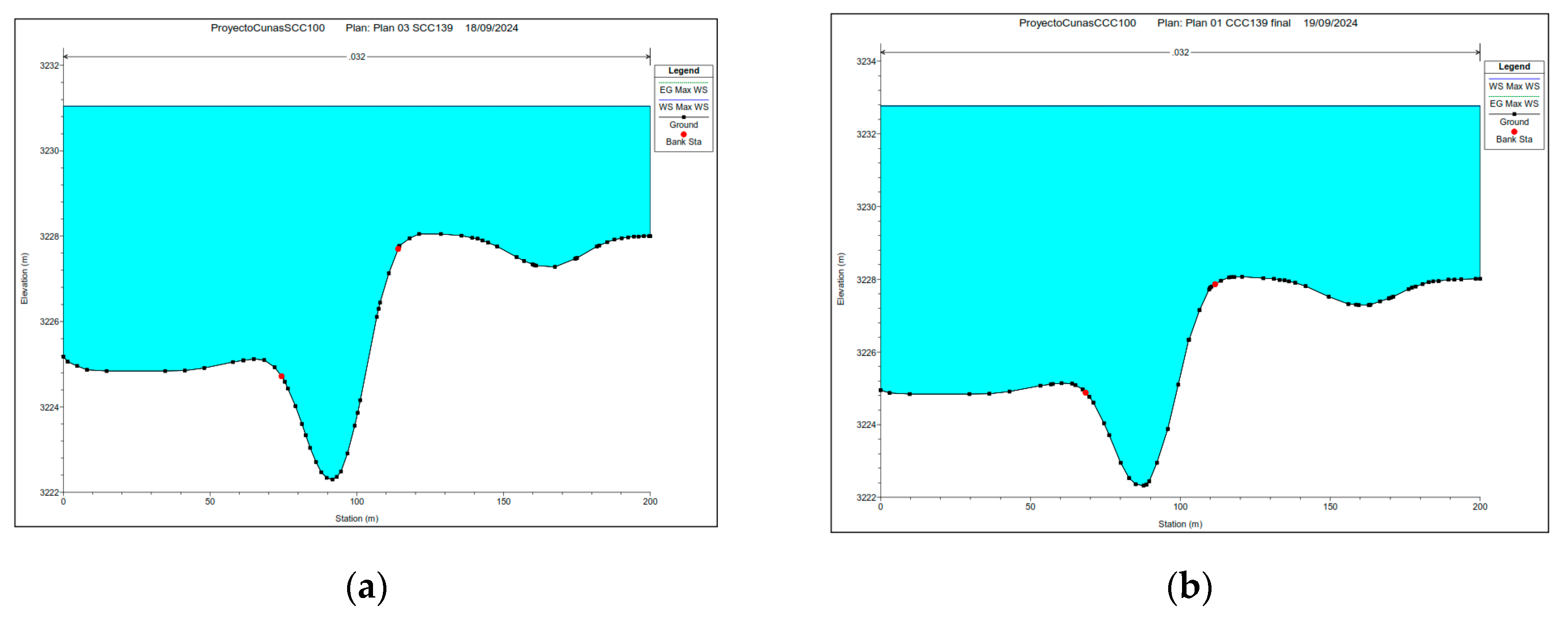

3.2. Flood Simulation (flooded Areas and Sections)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

References

- Samarasinghe, J.T.; Makumbura, R.K.; Wickramarachchi, C.; Sirisena, J.; Gunathilake, M.B.; Muttil, N.; Teo, F.Y.; Rathnayake, U. The Assessment of Climate Change Impacts and Land-use Changes on Flood Characteristics: The Case Study of the Kelani River Basin, Sri Lanka. Hydrology 2022, 9, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.Q.; Degener, J.; Kappas, M. Flash Flood Prediction by Coupling KINEROS2 and HEC-RAS Models for Tropical Regions of Northern Vietnam. Hydrology 2015, 2, 242–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, A.; Parajuli, U.; Regmi, S.; Kalra, A. Application of Machine Learning and Process-Based Models for Rainfall-Runoff Simulation in DuPage River Basin, Illinois. Hydrology 2022, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabinejad, S.; Schüttrumpf, H. Agent-Based Modeling for Household Decision-Making in Adoption of Private Flood Mitigation Measures: The Upper Kan Catchment Case Study. Water 2024, 16, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanapala, L.; Gunarathna, M.H.J.P.; Kumari, M.K.N.; Ranagalage, M.; Sakai, K.; Meegastenna, T.J. Towards Coupling of 1D and 2D Models for Flood Simulation—A Case Study of Nilwala River Basin, Sri Lanka. Hydrology 2022, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, F.; Mantilla, R.; Anderson, C.; Claman, D.; Krajewski, W. Assessment of Changes in Flood Frequency Due to the Effects of Climate Change: Implications for Engineering Design. Hydrology 2018, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadis, C.; Galiatsatou, P.; Glenis, V.; Prinos, P.; Kilsby, C. Urban Flood Modelling under Extreme Rainfall Conditions for Building-Level Flood Exposure Analysis. Hydrology 2023, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruss, Ł.; Wiatkowski, M.; Połomski, M.; Szewczyk, Ł.; Tomczyk, P. Analysis of Changes in Water Flow after Passing through the Planned Dam Reservoir Using a Mixture Distribution in the Face of Climate Change: A Case Study of the Nysa Kłodzka River, Poland. Hydrology 2023, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souley Tangam, I.; Yonaba, R.; Niang, D.; Adamou, M.M.; Keïta, A.; Karambiri, H. Daily Simulation of the Rainfall–Runoff Relationship in the Sirba River Basin in West Africa: Insights from the HEC-HMS Model. Hydrology 2024, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, L.; Sha, J.; Wang, B.; Li, G.; Ma, Q.; Ding, Y. Revelation and Projection of Historic and Future Precipitation Characteristics in the Haihe River Basin, China. Water 2023, 15, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabasara, K.; Gunawardhana, L.; Bamunawala, J.; Sirisena, J.; Rajapakse, L. Significance of Multi-Variable Model Calibration in Hydrological Simulations within Data-Scarce River Basins: A Case Study in the Dry-Zone of Sri Lanka. Hydrology 2024, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaibu, A.; Hounkpè, J.; Bossa, Y.A.; Kalin, R.M. Flood Risk Assessment and Mapping in the Hadejia River Basin, Nigeria, Using Hydro-Geomorphic Approach and Multi-Criterion Decision-Making Method. Water 2022, 14, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xia, X.; Teng, R.; Gu, X.; Zhang, Q. Risk Assessment of Dike Based on Risk Chain Model and Fuzzy Influence Diagram. Water 2023, 15, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaousmail, H.; Ayugi, B.O.; Lim Kam Sian, K.T.C.; Randriatsara, H.H.-R.H.; Mumo, R. How Do CMIP6 HighResMIP Models Perform in Simulating Precipitation Extremes over East Africa? Hydrology 2024, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colín-García, G.; Palacios-Vélez, E.; López-Pérez, A.; Bolaños-González, M.A.; Flores-Magdaleno, H.; Ascencio-Hernández, R.; Canales-Islas, E.I. Evaluation of the Impact of Climate Change on the Water Balance of the Mixteco River Basin with the SWAT Model. Hydrology 2024, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golian, S.; El-Idrysy, H.; Stambuk, D. Using CMIP6 Models to Assess Future Climate Change Effects on Mine Sites in Kazakhstan. Hydrology 2023, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, L.S.; Mattos, T.S.; Oliveira, P.T.S.; Almagro, A.; Rodrigues, D.B.B. Hydrological and Hydraulic Modeling Applied to Flash Flood Events in a Small Urban Stream. Hydrology 2022, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serikbay, N.T.; Tillakarim, T.A.; Rodrigo-Ilarri, J.; Rodrigo-Clavero, M.-E.; Duskayev, K.K. Evaluation of Reservoir Inflows Using Semi-Distributed Hydrological Modeling Techniques: Application to the Esil and Moildy Rivers’ Catchments in Kazakhstan. Water 2023, 15, 2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.N.A.; Almuktar, S.; Scholz, M. Rainfall-Runoff Modeling Using the HEC-HMS Model for the Al-Adhaim River Catchment, Northern Iraq. Hydrology 2021, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, M.U.; Haider, S.; Rashid, M.; Naseer, W.; Pande, C.B.; Đurin, B.; Alshehri, F.; Elkhrachy, I. Assessment of Hydrological Response to Climatic Variables over the Hindu Kush Mountains, South Asia. Water 2023, 15, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Hou, J.; Wang, T.; Li, D.; Gao, X.; Noor, R.S.; Jing, J.; Ameen, M. Assessment of the Impacts of Rainfall Characteristics and Land Use Pattern on Runoff Accumulation in the Hulu River Basin, China. Water 2024, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ma, Y. Sensitivity of Runoff to Climatic Factors and the Attribution of Runoff Variation in the Upper Shule River, North-West China. Water 2024, 16, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamos, I.; Diakakis, M. Mapping Flood Impacts on Mortality at European Territories of the Mediterranean Region within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Framework. Water 2024, 16, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodian, A.; Dezetter, A.; Diop, L.; Deme, A.; Djaman, K.; Diop, A. Future Climate Change Impacts on Streamflows of Two Main West Africa River Basins: Senegal and Gambia. Hydrology 2018, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, C.; Dimitriou, E. River Flow Alterations Caused by Intense Anthropogenic Uses and Future Climate Variability Implications in the Balkans. Hydrology 2021, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chathuranika, I.M.; Gunathilake, M.B.; Azamathulla, H.M.; Rathnayake, U. Evaluation of Future Streamflow in the Upper Part of the Nilwala River Basin (Sri Lanka) under Climate Change. Hydrology 2022, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Anwar, A.H.M.F.; Garg, N.; Prakash, M.; Bari, M. Monthly Rainfall Prediction at Catchment Level with the Facebook Prophet Model Using Observed and CMIP5 Decadal Data. Hydrology 2022, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaibu, A.; Mujahid Muhammad, M.; Bello, A.-A.D.; Sulaiman, K.; Kalin, R.M. Flood Estimation and Control in a Micro-Watershed Using GIS-Based Integrated Approach. Water 2023, 15, 4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.; Chang, C.-H.; Chen, W.-B. Comparison of Rainfall-Runoff Simulation between Support Vector Regression and HEC-HMS for a Rural Watershed in Taiwan. Water 2022, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Chu, X. A Modified SCS Curve Number Method for Temporally Varying Rainfall Excess Simulation. Water 2023, 15, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangelis, H.; Zotou, I.; Kourtis, I.M.; Bellos, V.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Relationship of Rainfall and Flood Return Periods through Hydrologic and Hydraulic Modeling. Water 2022, 14, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cao, Y.; Duan, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, F. Simulation and Prediction of the Impact of Climate Change Scenarios on Runoff of Typical Watersheds in Changbai Mountains, China. Water 2022, 14, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Hussein, A.A.M.; Khan, S.; Ncibi, K.; Hamdi, N.; Hamed, Y. Flood Analysis Using HEC-RAS and HEC-HMS: A Case Study of Khazir River (Middle East—Northern Iraq). Water 2022, 14, 3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsopoulos, G.; Diakakis, M.; Bloutsos, A.; Lekkas, E.; Baltas, E.; Stamou, A. The Effect of Flood Protection Works on Flood Risk. Water 2022, 14, 3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X. Future Joint Probability Characteristics of Extreme Precipitation in the Yellow River Basin. Water 2023, 15, 3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicka, E.; Kanclerz, J. Assessing the Effects of Urbanization on Water Flow and Flood Events Using the HEC-HMS Model in the Wirynka River Catchment, Poland. Water 2023, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, M.; Todaro, V.; Maranzoni, A.; D’Oria, M. Combining Hydrological Modeling and Regional Climate Projections to Assess the Climate Change Impact on the Water Resources of Dam Reservoirs. Water 2023, 15, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, V.B.P.; Chaffe, P.L.B.; Blöschl, G. Climate and land management accelerate the Brazilian water cycle. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil (INDECI). Reporte de Inundaciones en Huancayo. Available online: https://portal.indeci.gob.pe/emergencias/reporte-preliminar-n-2372-28-11-2023-coen-indeci-1030-horas-lluvias-intensas-en-la-provincia-de-huancayo-junin/ (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Yu, X.; Zhang, J. The Application and Applicability of HEC-HMS Model in Flood Simulation under the Condition of River Basin Urbanization. Water 2023, 15, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Hussein, A.A.M.; Hamed, Y.; Bouri, S.; Hajji, S.; Aljuaid, A.M.; Hachicha, W. The Socio-Economic Effects of Floods and Ways to Prevent Them: A Case Study of the Khazir River Basin, Northern Iraq. Water 2023, 15, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.H.; Kang, D.H.; Seo, Y.-H.; Kim, B.S. Analysis of Extreme Rainfall Characteristics in 2022 and Projection of Extreme Rainfall Based on Climate Change Scenarios. Water 2023, 15, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuli-Posadas, R.; García-Rivero, A.E.; Olivera Acosta, J.; Bulege-Gutierrez, W.; Miravet-Sánchez, B.L.; Neira Huamani, E. Determinación de escenarios de inundaciones en la subcuenca del río Cunas, Junín, Perú. Ing. Hidrául. Ambient. 2023, 44, 74–83, https://riha.cujae.edu.cu/index.php/riha/article/view/622. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Wang, Y.; Engel, B.; Zhang, W.; Peng, H.; Chen, X.; Xia, H. Performance Assessment of Spatial Interpolation of Precipitation for Hydrological Process Simulation in the Three Gorges Basin. Water 2017, 9, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershfield, D.M. Rainfall Frequency Atlas of the United States for Durations from 30 Minutes to 24 Hours and Return Periods from 1 to 100 Years: Technical Paper No. 40; Weather Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, D.C., USA, 1961.

- Ministerio de Transportes y Comunicaciones (MTC). Manual de Hidrología, Hidráulica y Drenaje; MTC: Lima, Perú, 2011; pp. 1–221. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/mtc/normas-legales/4443017-20-2011-mtc-14.

- Chow, V.; Maidment, D.R.; Mays, L.W. Applied Hydrology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-07-100174-8. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bagoury, H.; Gad, A. Integrated Hydrological Modeling for Watershed Analysis, Flood Prediction, and Mitigation Using Meteorological and Morphometric Data, SCS-CN, HEC-HMS/RAS, and QGIS. Water 2024, 16, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizian, A. Comparison of Salt Experiments and Empirical Time of Concentration Equations. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Water Manag. 2019, 172, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, B.; Öztürk, M.; Özölçer, İ.H. Effect of Bed Material on Roughness and Hydraulic Potential in Filyos River. Water 2024, 16, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masamba, S.; Fuamba, M.; Hassanzadeh, E. Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on an Ungauged Watershed in the Congo River Basin. Water 2024, 16, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.J.; Lee, G.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.; Jo, J.; Woo, D.K. Climate Change Impact Assessment on Water Resources Management Using a Combined Multi-Model Approach in South Korea. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, L.; Sha, J.; Wang, B.; Li, G.; Ma, Q.; Ding, Y. Revelation and Projection of Historic and Future Precipitation Characteristics in the Haihe River Basin, China. Water 2023, 15, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-T.; Yu, J.-U.; Kim, T.-W.; Kwon, H.-H. A Novel Approach to a Multi-Model Ensemble for Climate Change Models: Perspectives on the Representation of Natural Variability and Historical and Future Climate. Weather. Clim. Extrem. 2024, 44, 100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojpratak, S.; Supharatid, S. Regional Extreme Precipitation Index: Evaluations and Projections from the Multi-Model Ensemble CMIP5 over Thailand. Weather. Clim. Extrem. 2022, 37, 100475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Aguila, S.; Espinoza-Montes, F. Impact of climate change on future discharges from a high Andean basin in Peru to 2100. Tecnol. Cienc. agua 2024, 15, 111–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Díaz, K.J.; Ramos-Fernández, L.; Velásquez-Bejarano, T. Projection of the impacts of climate change on the flow of the Lurín river basin-Peru, under CMIP5-RCP scenarios. Idesia 2022, 40, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Kettle, A.; Meresa, H.; et al. Climate Change Impacts on Irish River Flows: High Resolution Scenarios and Comparison with CORDEX and CMIP6 Ensembles. Water Resour Manage 2023, 37, 1841–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syldon, P.; Shrestha, B.B.; Miyamoto, M.; Tamakawa, K.; Nakamura, S. Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Flood Inundation and Agriculture in the Himalayan Mountainous Region of Bhutan. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 52, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Hussein, A.A.M.; Khan, S.; Ncibi, K.; Hamdi, N.; Hamed, Y. Flood Analysis Using HEC-RAS and HEC-HMS: A Case Study of Khazir River (Middle East—Northern Iraq). Water 2022, 14, 3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, D.; Oweis, T.Y.; Pasquale, S.; Kijne, J.W.; Hanjra, M.A.; Bindraban, P.S.; Bouman, B.A.M.; Cook, S.; Erenstein, O.; Farahani, H.; et al. Pathways for increasing agricultural water productivity. In Water for Food, Water for Life. A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture; Molden, D., Ed.; Earthscan-International Water Management Institute: London, UK, 2007; pp. 279–310. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/36882.

- Zisopoulou, K.; Panagoulia, D. An In-Depth Analysis of Physical Blue and Green Water Scarcity in Agriculture in Terms of Causes and Events and Perceived Amenability to Economic Interpretation. Water 2021, 13, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoussou, E.; Amoussou, F.T.; Bossa, A.Y.; Kodja, D.J.; Totin-Vodounon, H.S.; Houndénou, C.; Borrell-Estupina, V.; Paturel, J.E.; Mahé, G.; Cudennec, C.; Boko, M. Use of the HEC RAS model for the analysis of exceptional floods in the Ouémé basin. Proc. IAHS 2024, 385, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Vargas, E.; Chávarri-Velarde, E.; Ingol-Blanco, E.; Mejía, F.; Cruz, A.; Vera, A. Impacts of Climate Change and Variability on Precipitation and Maximum Flows in Devil’s Creek, Tacna, Peru. Hydrology 2022, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, G.; Beneyto, C.; Aranda, J.Á.; Machado, M.J.; Francés, F.; Sánchez-Moya, Y. Inundaciones y Cambio Climático: Certezas e Incertidumbres en el Camino a la Adaptación. Cuadernos de Geografía de la Universitat de València 2022, 107, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, L.; Bisselink, B.; Dottori, F.; Naumann, G.; de Roo, A.; Salamon, P.; Wyser, K.; Feyen, L. Global Projections of River Flood Risk in a Warmer World. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelling, M. Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation; Routledge: 2010; 1st ed. [CrossRef]

| Cunas River Basin | Indicador | Unidad | Valor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphometric properties basin | Área | [Km²/s] | 1700.25 |

| Perímeter | [Km] | 279.62 | |

| Length | [Km] | 54.37 | |

| Width | [Km] | 31.27 | |

| Average slope | [%] | 23.73 | |

| Maximum elevation | [msnm] | 4953.00 | |

| Minimum elevation | [msnm] | 3216.00 | |

| Average elevation | [msnm] | 4203.82 | |

| Main channel properties | Length | [Km] | 93.79 |

| Length to the dividing line | [Km] | 98.50 | |

| Highest elevation | [msnm] | 4532 | |

| Lower elevation | [msnm] | 3221 | |

| Average slope | [%] | 1.40% | |

| Drainage network properties | Total length of drains | [Km] | 2839.16 |

| Drainage density | [Km/km²/s] | 1.67 | |

| Order of currents | [-] | 5° | |

| Runoff coefficient | [-] | 0.59 | |

| Form index | Compactness coefficient, Kc | [-] | 1.90 |

| Form factor, Kf | [-] | 0.19 |

| Method used | Calculated Tc (Hrs) |

Var. Min (Hrs) | Var. Máx (Hrs) | Acceptance | Tc valid (Hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giandotti | 7.11 | 5.36 | 11.04 | Sí | 7.11 |

| Kirpich | 5.77 | 5.36 | 11.04 | Sí | 5.77 |

| California (U.S.B.R) | 5.78 | 5.36 | 11.04 | Sí | 5.78 |

| Témez | 9.62 | 5.36 | 11.04 | Sí | 9.62 |

| Johnstone Cross | 8.41 | 5.36 | 11.04 | Sí | 8.41 |

| SCS Ranser | 5.77 | 5.36 | 11.04 | Sí | 5.77 |

| Average Tc calculated for the hydrographic unit studied. | 7.08 | ||||

| Condition | Features | Return period (Years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 50 | 100 | 139 | 200 | ||

| Normal conditions | Precipitation volume (mm) | 42.62 | 44.72 | 46.93 | 48.01 | 49.24 |

| Volume of losses (mm) | 18.67 | 18.95 | 19.23 | 19.35 | 19.49 | |

| Excess volume (mm) | 23.95 | 25.77 | 27.7 | 28.66 | 29.74 | |

| Volume of direct runoff/desload (mm) | 23.90 | 25.72 | 27.65 | 28.61 | 29.69 | |

| Maximum flow (m³/s) | 152.50 | 164.40 | 176.90 | 183.10 | 190.10 | |

| With the presence of climate change | Precipitation volume (mm) | 44.51 | 46.7 | 49 | 50.14 | 51.42 |

| Volume of losses (mm) | 18.92 | 19.2 | 19.47 | 19.59 | 19.73 | |

| Excess volume (mm) | 25.58 | 27.5 | 29.54 | 30.54 | 31.69 | |

| Volume of direct runoff/desload (mm) | 25.54 | 27.45 | 29.48 | 30.49 | 31.63 | |

| Maximum flow (m³/s) | 163.20 | 175.60 | 188.80 | 195.30 | 202.70 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).