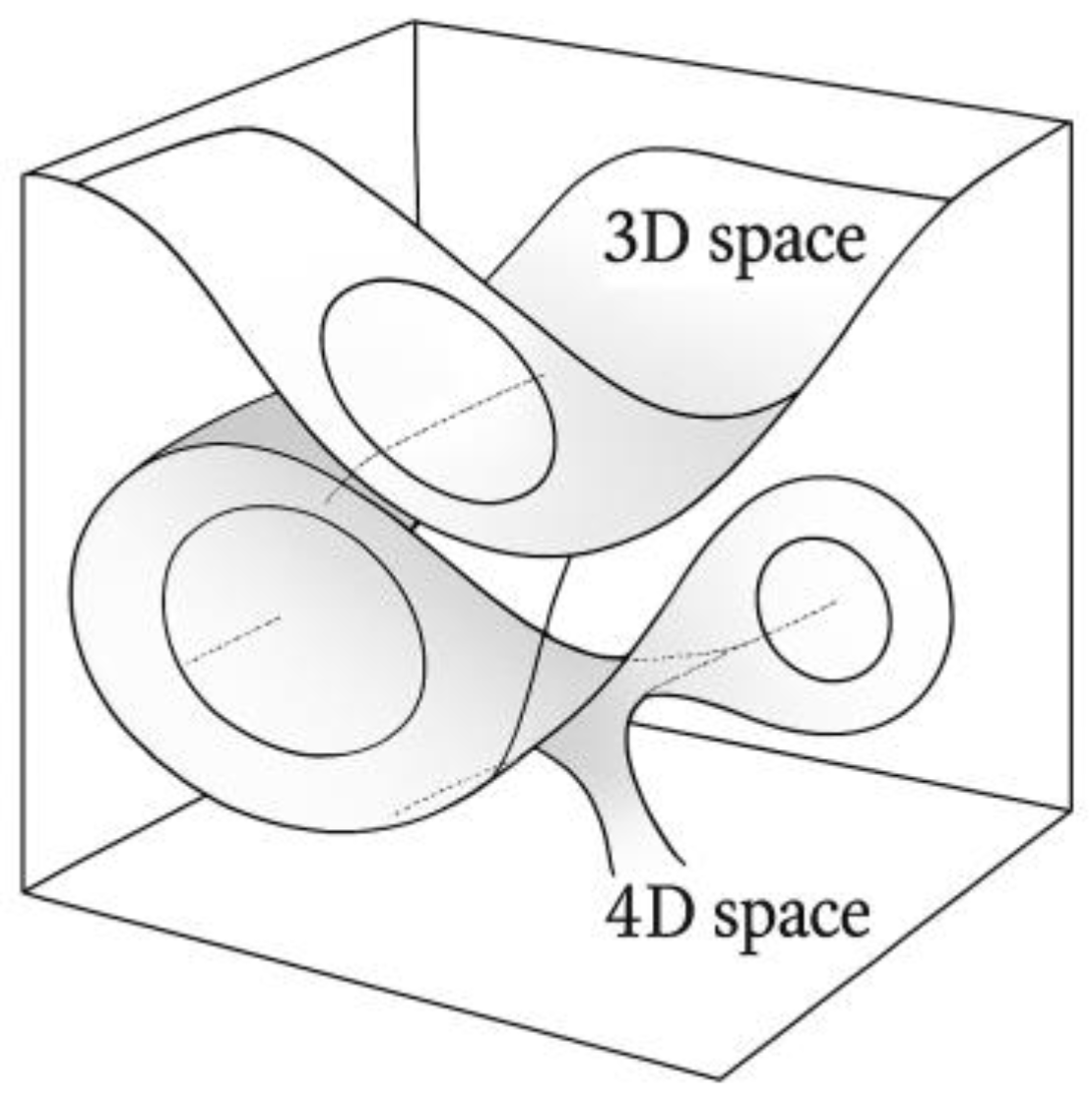

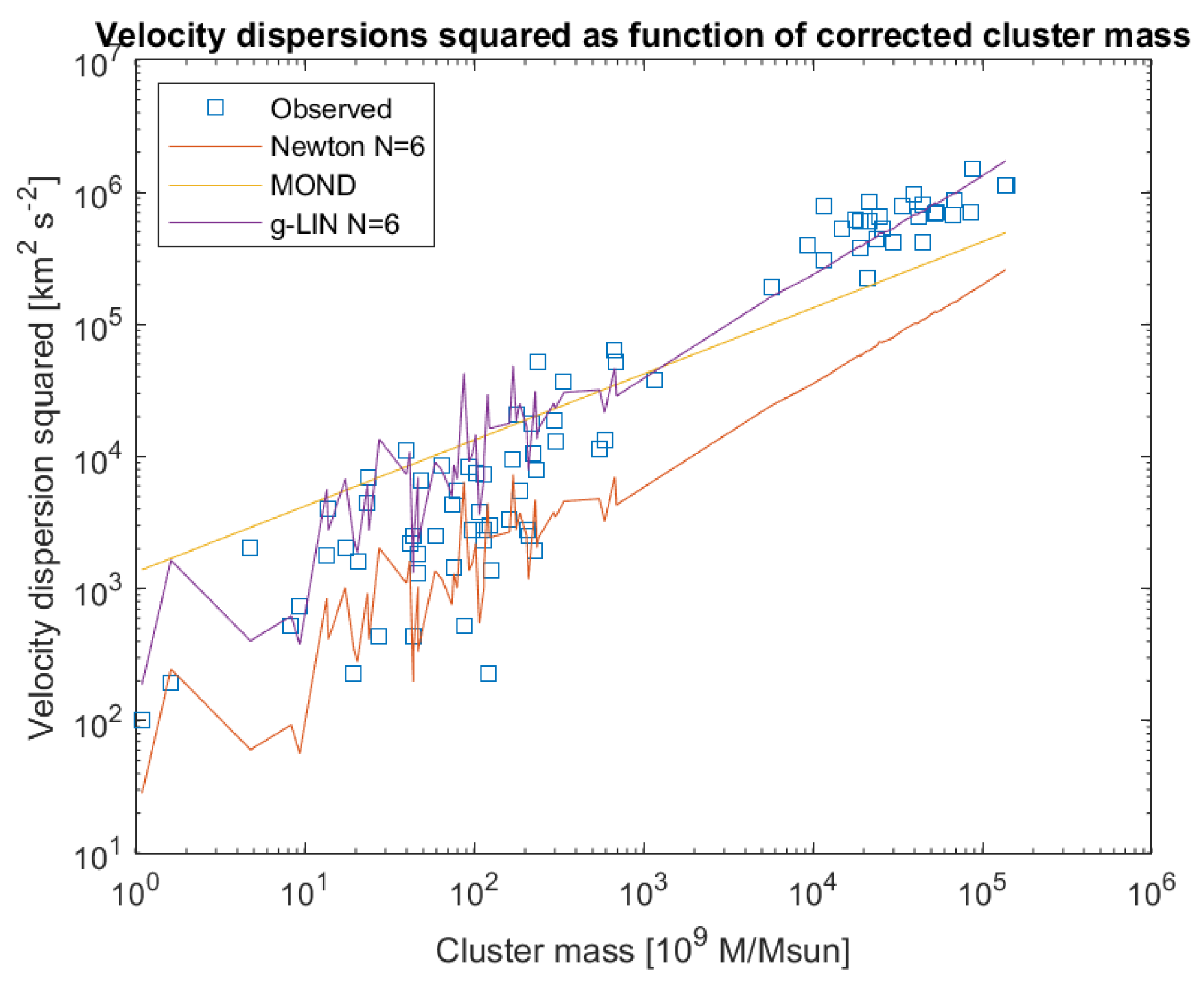

This expansion affects the 2-dimensional projections of universes in one another in the supposed 4-dimensional multiverse. The 2-dimensional projections of other 3-dimensional universes that expand at the same rate as ours, will be stretched, at the same rate as the radius of the 3-dimensional universe, to remain consistent geometrically. This occurs since a 2-dimensional plane with a fixed thickness, i.e. the Planck-length Lp, will have to increase its surface at the same rate as the other increases its volume to still fill that volume.

Therefore, the projections and hence the gravity contribution of the other universes will be diluted from the galaxies and decrease of the effect of dark matter in galaxies will be strongly correlated with the expansion rate of the radius of the universes. In this way the gravity from the other universes will start to appear as resulting from a line-source of mass as mentioned in chapter 5. Besides this, from this prediction, it logically follows that in the past, when the universe was much smaller, the additional gravity in galaxies must have been much larger. In the small universe of the beginning, it has been larger than Newtonian gravity. The effect of this must be traceable in the initial stages of the evolution of the universe. The case for this will be argued at the end of this chapter.

5.4.1. Checking Consistency with TeVeS

TeVeS was developed on the basis of the action principle, with two additional actions and a free function added to the geometric action of GR and varying those actions with respect to the metric and to the scalar and vector fields added by Bekenstein in those actions. Variation calculus on these actions yields a differential equation for the free function F, which then is shown to reproduce MOND. The differential equation of Bekenstein is used here to show the theory of linear gravity as well is a valid solution of this. And in the sequel, it is shown that the dilution of dark matter from galaxies with time, inevitably follows from these equations.

He applies different metrics in his actions for different applications and solves them for those situations, like for instance non-spherical symmetric cases like galaxies and to study the evolution in time using the Friedmann-Robertson-Walker (FRW) metric in his added actions. In this chapter it will be shown that this framework as well allows for the hypothesis of linear gravity to be entered into TeVeS, so the mathematics of TeVeS as well can incorporate linear gravity perfectly and used to study the evolution in time of the added gravity caused by dark matter.

As with MOND, in TeVeS a function µ is introduced, that modifies the total gravitational acceleration to obtain the Newtonian acceleration. It thus acts on the sum of all contributions to the total gravitational acceleration and not on the contributions from different masses in a galaxy separately. The application of TeVeS in this chapter to the proposed hypothesis will, however, do so. Like in chapter 5.2 formula (18), the contributions all masses in a galaxy have to be summed up after modification with µ for each contribution separately.

Conservation of momentum is not satisfied by MOND, but is automatically satisfied in physical theories that are derived using an action principle [

3]. To that end, in AQUAL, his starting point, the following Lagrangian was formulated under the assumption of and additional real scalar field ψ:

(21)

Where f is some function, not known a priori. The same recipe is followed in TeVeS: define and additional scalar field as well as a free function, the exact form of which at a later stage follows from constraints that come with solving the equations. MOND formula (5) then follows from (21) under spherical symmetry and static conditions.

T

eV

eS [

3] is based on three dynamical gravitational fields: and Einstein metric

gµυ with a well-defined inverse

gµυ and a time-like 4-vector field Џ

µ as well as a dynamic scalar field

ϕ and a non-dynamical scalar field

σ. The physical metric is obtained by stretching the Einstein metric in space-time directions orthogonal to Џ

α = gαβ Џ

β by a factor e

-2ϕ while shrinking it by the same factor in the direction parallel to it. As becomes clear from [

3] (p. 21 formulas (52), (53) and (58)) the scalar field

ϕ is to be interpreted as the additional gravitational potential. So, in T

eV

eS this potential

ϕ is added to the Newtonian potential.

Then the total action resulting from the scalar fields contains a geometric part just as in GR, the Einstein-Hilbert action

Sg, the matter action

Sm and two extra actions,

Ss and

Sv, including two positive parameters

k (dimensionless) and

l (a length scale) and a free dimensionless function

F, which is related to an additional gravitational potential [

3] (p. 8). The shape and behaviour of

F must be consistent with the theory and yield a valid solution of the equations. The extra action for the pair of scalar fields is as follows [

3]:

(22)

where hαβ = gαβ - Џα Џβ.

Then, varying the three actions with respect to the metric and to the scalar and vector fields added by Bekenstein in those actions gives a general solution for spherically symmetric situations. Variation of σ in

Ss gives the relation between σ and ϕ

,α and

F, where per definition [

3]

F’ = dF(µ)/dµ:

(23)

Now [

3] defines the function

µ(y) such that equation (23) takes the following shape:

(24)

so that .

This differential equation can be solved when the function µ(y) is specified, so as to yield the function F(µ). If µ(y) yields a solution for F(µ) and the solution shows proper behaviour, i.e. consistent with the theory, then the theory incorporates relativity consistently. This now is done for the hypothesis of linear gravity.

Bekenstein has firstly derived his free function

F(µ) for relativity in quasistatic systems. He does not calculate it for MOND separately, but explores the behaviour in different limits, for example the non-relativistic limit, to show it just reproduces MOND in those cases. This, for example leads to an equation [

3] (p. 13 formula (58)) that closely resembles equation (7), so the potential being the sum of Newtonian and an additional potential. This, again, hints at the strong relationship between MOND, T

eV

eS and linear gravity.

As a starting point to determine F(µ) for linear gravity, so as to predict gravitational acceleration from a given mass distribution including relativistic effects, inverting formula (9) yields:

(25)

This follows directly from the theory of linear gravity as outlined in chapter 4 and it can be used instead of Bekenstein’s free function

y(µ) from [

3] (Bekenstein’s formula (50) to predict gravitational acceleration from a given mass distribution. Bekenstein states that there is great freedom in choosing

y(µ) and hence

F(µ), but here it directly follows from the theory that the gravitational acceleration in a galaxy is the sum of two contributions, see chapter 4, formula’s (6) and (8).

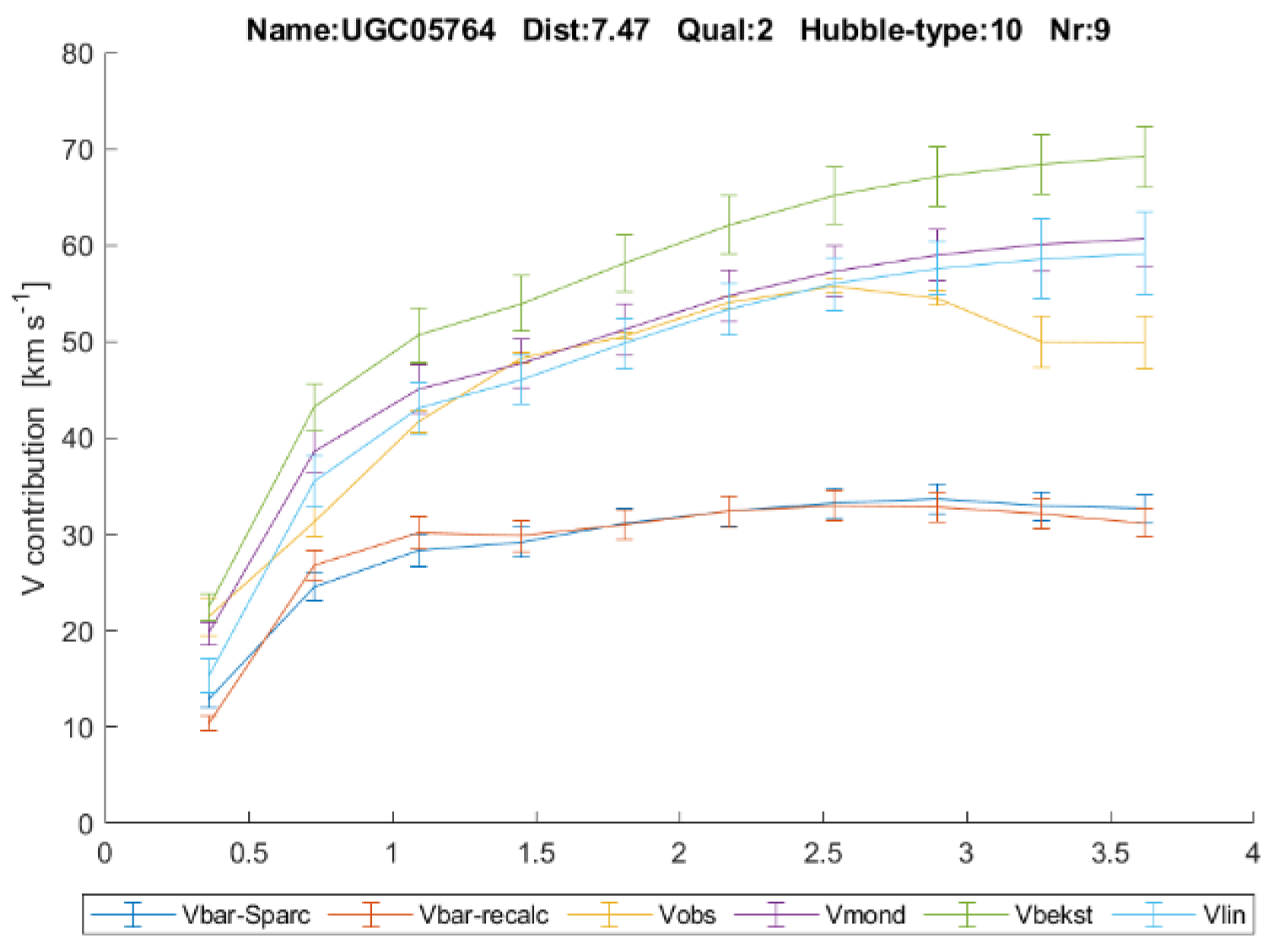

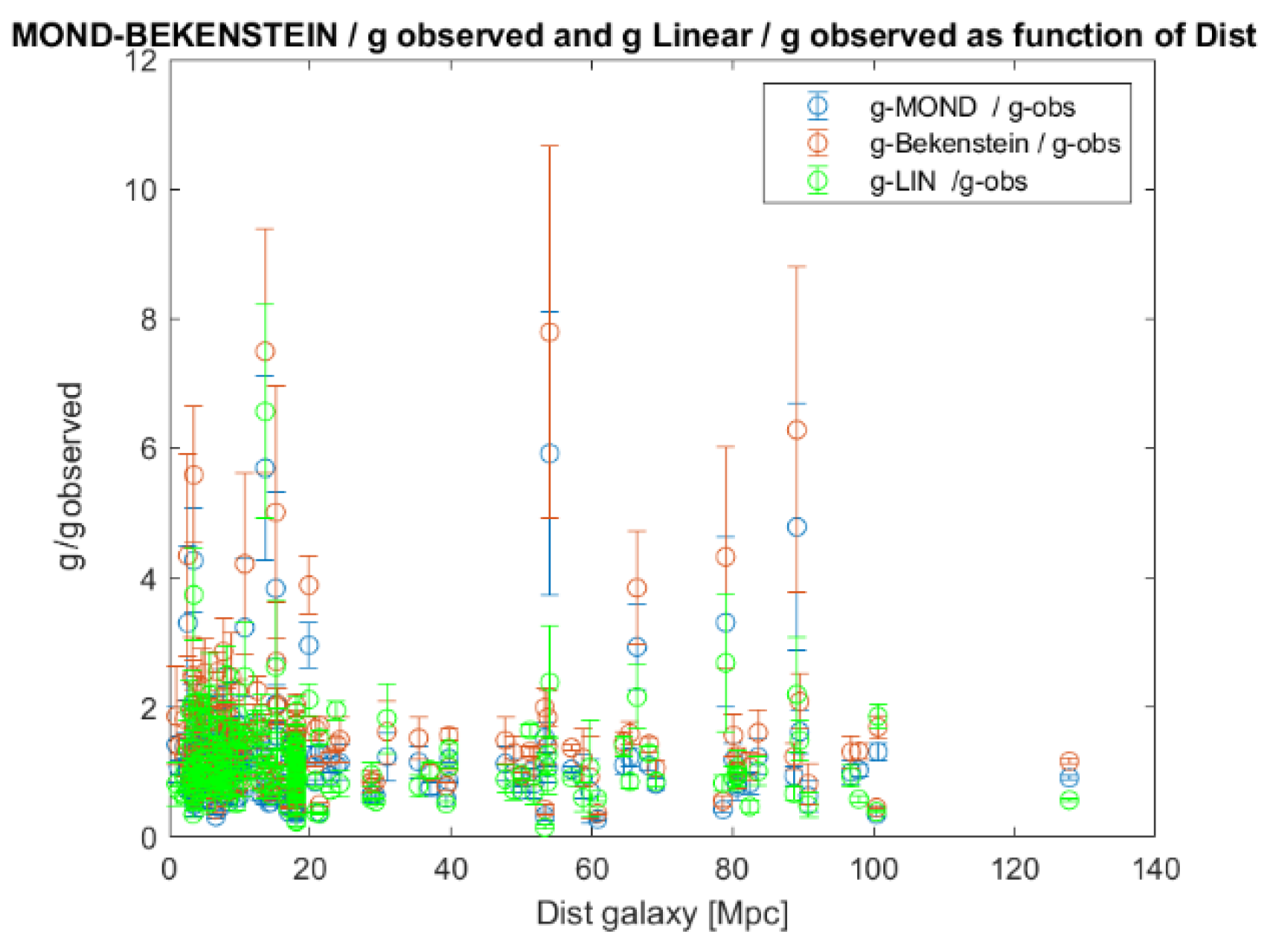

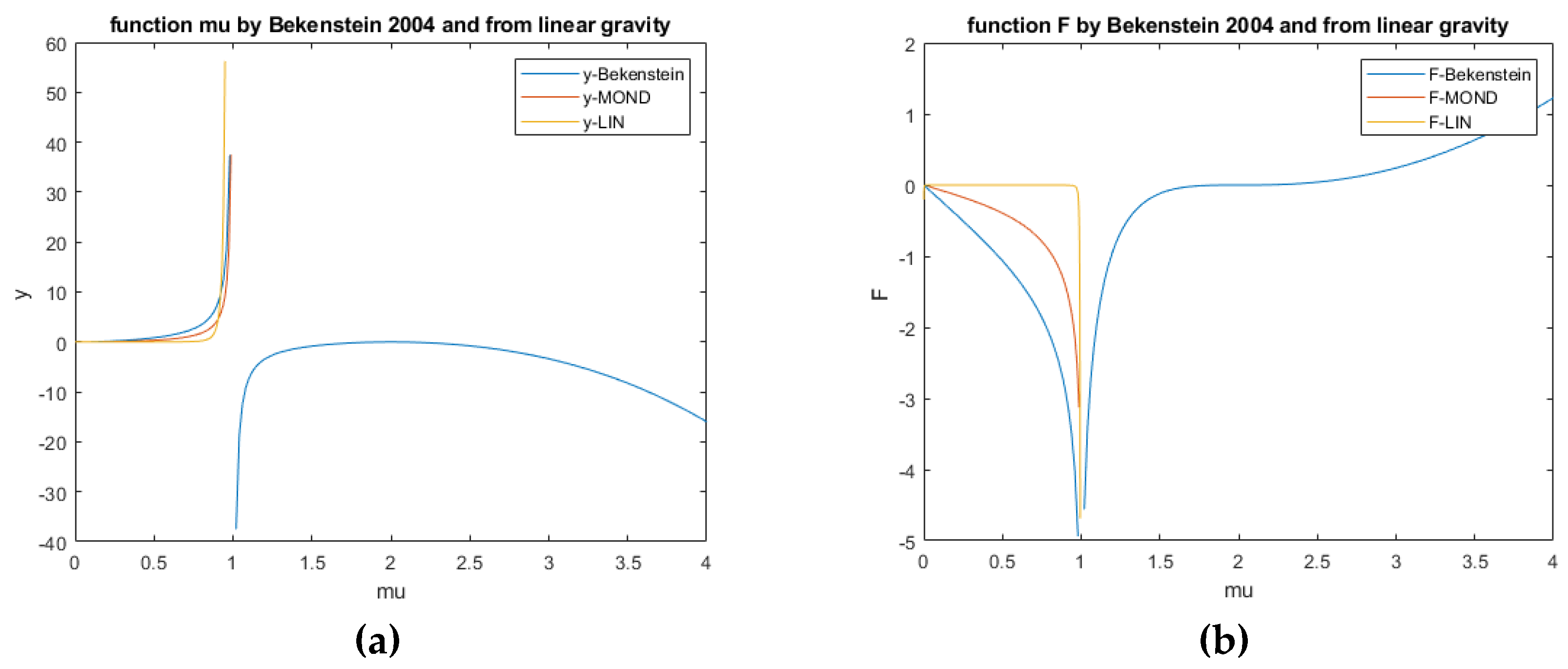

Figure 11a shows it gives a somewhat steeper increase towards

µ = 1, but the trend as well as the sign and magnitude are of the same order as MOND and T

eV

eS. And no values for

µ > 1 to account for cosmological effects are needed now, since dark matter is part of this hypothesis, opposed to MOND and T

eV

eS. The most left part, with

µ << 1 is the deep MOND-regime.

µ = 1 is the case where Newtonian gravity fully dominates.

However,

c is not a constant but depends on the mass

mi in a certain position in the galaxy now as discussed in chapter 5.2 formula (20). But, on using a linearised metric as in Bekenstein [

3] (p. 18, section B) the sum is a valid solution when each contribution to the sum is a valid solution. As explained by Bekenstein and for example in Schutz [

41] (p. 200) this is valid for low gravitational acceleration where space-time is nearly flat.

So, in galaxies, y may be treated the sum of many contributions from all mass in the galaxy, each with their own value of c, i.e conforming to formula (20). ci. And in galaxies with a bulge, in line with chapter 5.2, the bulge and the disk can be treated separately and the results added to yield a solution for the galaxy with bulge as a whole. The same applies to all different masses in a galaxy. So, if at one radial position R for one contribution from mass at another position X, agreement is proved, it is valid for the total acceleration g at a point.

Integration of (24) with use of (25), with c* = c4/am2, gives:

(26)

k1 is an integration constant, which can be chosen small compared to c* such that the function F(µ) at small values of µ, i.e. in the outer regions of the galaxy, is not dominated by the most right quadratic term in (26) but continues to converge steadily when µ, goes to zero. µ is limited to the range [0-1) in galaxies and when µ = 1 Newtonian acceleration is the only contribution to the acceleration, so in the centre of the galaxy and y would go to infinity. Bekenstein applies his function F to values of µ > 1 for cosmology and gravitational lensing, but that is not necessary if dark matter is used to explain those effects.

Again, as

Figure 11b shows, the function

F by linear gravity towards

µ = 1 is steeper, but the trend and the sign are as well as the orders of magnitude are the same. The same applies to the function derived from MOND, what Bekenstein did not show, but is done here in the same way equation (26) was derived. As can be seen in

Figure 11 in chapter 5.4 as well as Annex 3, the impact of the differences in

F on the predicted rotation velocities are rather small. And again, no values for

µ > 1 to account for cosmological effects are needed here.

This latter restriction, valid since dark matter is not excluded here, as well cures some of the reported problems of T

eV

eS like the incompatibility with the value of the quantity

Eg at cosmological scales reported by Zhang [

42]. Since linear gravity is an explanation of dark matter and not designed to do without it, the function

µ, does not have to account for gravitational lensing effects and cosmological dark matter. Like in MOND, it only is applied in the range

µ =[0-1), so with a positive contribution of dark matter to gravity. And since it is only applied for very weak fields, determining the motions of stars and gas in galaxies, the T

eV

eS problem with instability in stars reported by Seifert [

43] does not apply here either. Applying T

eV

eS as a mathematical approach to dark matter is in line of the hybrid approach to dark matter as advocated by Banik [

2].

5.4.2. Assessment of Evolution in Time with TeVeS

Bekenstein [

3] also explores the dynamic, time-dependent, behaviour in his section E for, among other, the matter era in the evolution of our universe. Please note, the elaboration in the sequel fully applies to his theory and MOND as well, since in the outer regions of galaxies, i.e. the deep MOND regime, the theories behave the same with respect to the function

y(

µ), as can be seen upon comparing formulas (2) and (3) with (8) for small values of

g, and the same for

F(

µ). And these functions are still free in Bekenstein’s scalar equation [

3] (Bekenstein’s equation (37)) that is applied down here again.

Recall that

µ is the ratio of Newtonian acceleration over total acceleration. Hence it is a decreasing function of the radial position in a galaxy and a supposed decay of the additional gravity by dark matter would make it grow towards unity. To explore this, Bekenstein uses the Friedmann-Robertson-Walker (FRW) cosmology [

3] (p. 10) in which

a(t) is the scale factor of the expanding universe.

(27)

Bekenstein uses (27) to a obtain a modified, now time-dependent scalar equation, (30) in the sequel, as well as a modified Friedmann equation (28) in TeVeS. Then he uses a combination of both to study the resulting evolution of F and ϕ, the additional gravitational potential caused by the added scalar field, in time.

His modified Friedmann equation, obtained from variation of his additional action S with respect to this metric, with ρ being the proper energy density and p the pressure and ϕ > 0, is:

(28)

Please note, that all variables are scaled such way by Bekenstein that

ϕ << 1 and that is it dimensionless [

3] (pp. 8, 12 and 20). Later on he will argue that the left term of the right-hand-side in (28) dominates over the right term, which he then ignores.

Now Bekentein wants to find a relation between the time derivatives of

a(t) and

ϕ(t) by combining this, as said, with a time dependent scalar equation. Applying his scalar equation (Bekenstein’s formula (37)) to the FRW metric yields Bekenstein’s formula (45) copied down here [

3] (p. 10):

(29)

Since the function F(µ) was part of the definitions of Bekenstein’s additional action Ss and hence of formula (23), the function µ reappears here as part of a differential equation, but, as mentioned earlier, with F still free.

In the matter era

and

ρ varies as

a-3 [

3] (p. 21). Then integrating equation (29) from the start of this era gives:

(30)

The time tr is the time at the end of the radiation era and the start of the matter era, where a = ar. Now Bekenstein explicitly evaluated this integral from tr to t to let (30) become the following equation:

(31)

Now equation (28) is used to express the left term in the right-hand-side in as a function of .

After that, Bekenstein argues that after the start of the matter era, after the first e-folding of a, the first term of the right-hand side becomes dominant, so over most of the matter era up to the present. Ignoring the second term in the right hand makes (31) a simple differential equation. This is elaborated down here following Bekenstein.

Bekenstein [

3] (p. 22) only elaborates on the situation that

µ > 2, so for application in cosmology and then states the evolution in time is small. But it is important to note that if

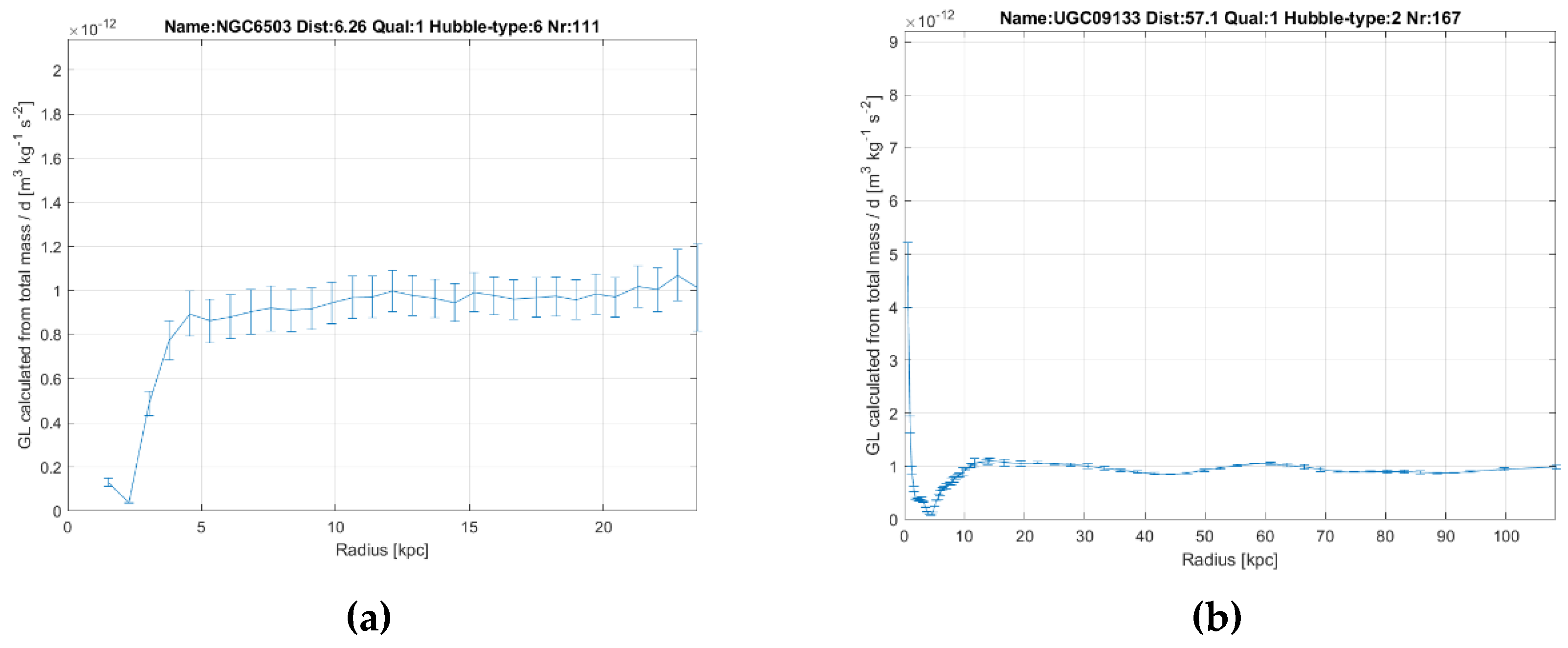

µ << 1, like in the flat rotation region of a galaxy (typically in the order of O (0.1) in the 175 galaxies studied with a deep MOND regime)

dϕ/dt might become very large indeed in this equation. For it then is multiplied with a very small

µ in the left-hand side, which is relevant in the sight of the third prediction of this paper. So, this case is elaborated in the sequel.

Bekenstein does solve this equation with the help of (28) and ends with the following inequality, which in galaxies gets a < sign, since now F < 0 and y > 0:

(32)

But, he argues that this inequality is nearly saturated, since the scalar field contributions to his modified version of the Friedmann’s equations (28) are small compared to the left term in the right-hand-side [

3] (pp. 20 and 21) as mentioned earlier after equation (28). Since in galaxies the absolute values of

µ,

y and

F, are all smaller than in cosmology (

µ > 2) this is even much truer in galaxies as can be seen upon comparing the left and right parts of

Figure 8 with each other.

Then he integrates his equation from tr to the current time t, But this can only be an approximation since µ actually is a function of time too, so this is valid only for a certain value of µ. With µ = O (0.1) instead of 2 this gives:

(33)

With

k = 0.03 as determined by Bekenstein, it follows that this decay

amounts to -0.11 approximately. In his work, Bekenstein [

3] (pp. 20-22) scaled his variables such that during the entire cosmological evolution

ϕ << 1 (i.e. e

ϕ≈ 1). His initial value was 0.007 <

ϕ0 << 1 [

3] (p. 22). This simply means that the predicted decay of -0.11 in a typical galaxy, dominates the current value of the gravitational potential by linear gravity, so in the past it must have been much stronger than nowadays. Comparing Milgrom’s constant with Earth’s gravitational acceleration, confirms it is a very weak field nowadays in galaxies, so

ϕ << 1 at present. Bekenstein [

3] (pp. 10,11,12) gives another estimate of

ϕ in cosmology and in localised systems like galaxies, and states that

ϕ as defined in his theory nowadays typically has a value of order O (

k). The actual value of order

k = 0.03 evidently is much smaller than 0.11.

And for galaxies the inequality (32) gives an lower limit on the decay. Recalling it has a negative value, it’s magnitude may be larger even than 0.11, provided µ were constant, what is discussed in the sequel. And, as can be seen in equation (32), there will inevitably be a decay as long as there is linear gravity, except when k would be zero, but that would mean no linear gravity, so no dark matter.

But all this is only relevant when the decay of the additional potential affects the additional gravitational acceleration. So, the radial derivatives of the potential must be affected by this in a galaxy. µ being a decreasing function of the radial position, as stated earlier, ensures this. It decreases with increasing radial position and hence increases as function of the radial position, cf. formulas (30) to (32). So the additional acceleration in a galaxy decreases as well. It must have undergone a vast decay since the start of the matter dominated era, since through the lower µ values then, ϕ varied much more with the radial position than it does now, so it’s radial derivative must have been huge compared to nowadays.

Consequently, the lower values of µ in the past made the magnitude of the decay much larger than 0.11 in the past. The decay getting smaller and smaller as time proceeds is exactly what you would expect for a dilution as described in chapter 5.3. This can be made explicit by solving (33) again, but now assuming µ is a function of time t as well, so as to check whether the predicted additional acceleration in the past as well decreased linearly with radial position, consistent with the hypothesis.

This can be checked by modifying equation (7) analogue to the approach leading to the FRW metric and see if the equation has a solution. Bekenstein follows exactly the same approach [

3] p. 10) to obtain his equations (Bekenstein’s equations (44) and (45) and the text above his equation (44)). So equation (7) is modified as follows:

(34)

Then, differentiating (34) with respect to R gives a gravitational acceleration that is as well proportional to f(t). Hence, if one defines a function f(t) that decreases or increases the potential ϕ with time t, so that ϕ(t) = f(t-tr) ϕr, then it follows logically that µ(t) = f-1(t-tr) µr. In the sequel it will be verified this has a solution.

Inserting the above in equation (32) and as argued, considering (32) nearly saturated and assuming

[

3] (p. 21), [

13] (p. 236) makes it a simple differential equation in f(t-tr). Rewriting this in terms of

and solving it, makes it possible to extrapolate as well to the current era with accelerating expansion, where

tr in the denominator of the fraction can be ignored:

(35)

With

c = k/(8π ϕr µr). The exact speed of the decay is unknown, but clearly depends on the product

ϕr µr. But

ϕr and

µr are unknown, and their values, at the start of the matter dominated era, cannot be determined directly from the current values using equation (36). For the galaxies have undergone an evolution in this long period. But it can be showed, the assumptions made up here,

ϕ(t) = f(t-tr) ϕr etc

,, in this derivation, beneath equation (34), are not a limitation, since

f(t) is eliminated in the product

ϕrµr, for it appears in both the numerator and the denominator. And during the largest period of the matter dominated era galaxies as studied here did already exist, from 300 million years after the Big Bang [

13] (p. 141), and before that the matter that would form the galaxies already existed in localised and rotating clouds of matter, so formula (33) may hold over the very largest part of this period [

13] (p. 150).

Besides this, it can be shown, this as well holds when the most right term in the right-hand side of equation (30) is not ignored; then the right-hand side of (36) only will be multiplied with a power of e, that in the product ϕr µr still drops out. But the current value of the product ϕ µ clearly is not a constant, and will be a function of radial position R in a galaxy, so it does not have a unique value now, but it does not vary with an order of magnitude, since it varies only with ln(R)/R (less than a factor 8 from 2 to even 100 kpc). Given this small range, the deviation from the assumptions made in equation (34) in the first period of this era may be limited. So, using actual values, some constraints and an estimation can be given to find the order of magnitude of c.

A constraint on

µr for

c to be unity, so the power of

a/ar is minus unity, i.e. the most simple form of a dilution of

ϕ from galaxies, can be derived. Given the lowest value for

ϕr estimated in the above

ϕr > 0.11, the value of

c could be unity when

µr < 0.012. This is realistic when compared with the current typical value of

µ = O (0.1), and a pair of values for

ϕ and

µ that obeys to this and to equation (37) can exist. And, as mentioned, Bekenstein [

3] (pp. 10,11,12) gives an estimate of

ϕ in cosmology and in localised systems like galaxies, and states that

ϕ as defined in his theory currently typically has a value of order O (

k). Combining this with the current typical value of

µ = O (0.1) in the deep MOND regime, gives an estimate of the order of magnitude of the power:

c = O (1). So the dilution of

ϕ from galaxies, and hence the growth of

µ, goes with a power of

a/ar that is of order O (-1). So, the power law (35) indeed is typical for a case of simple dilution of a physical quantity with the scale of space

a.

To summarize: since the function

F was part of the definition of Bekenstein’s additional action

Ss and hence of formula (23), the function

µ reappears as part of a differential equation for

ϕ(t) when Bekenstein’s actions are combined with the, time-dependent, FRW metric. It is shown there is a decay of the additional gravitational potential by linear gravity with time, that the decay till now has been vast, that it follows a power law typical for simple dilution of a physical quantity with time and that the power has a value in the order of minus unity. The increase of

µ in time, per definition would mean a decrease of Milgrom’s constant

am in time. Sanders [

44] with the assumption of a constant

am already showed that MOND predicts faster development of structure in the early universe and the decrease of

am in time will make this effect even stronger. This all confirms the third prediction of this paper and this significant time evolution of

ϕ in T

eV

eS gives an even more powerful explanation for the rapid evolution of large galaxies in the early universe.

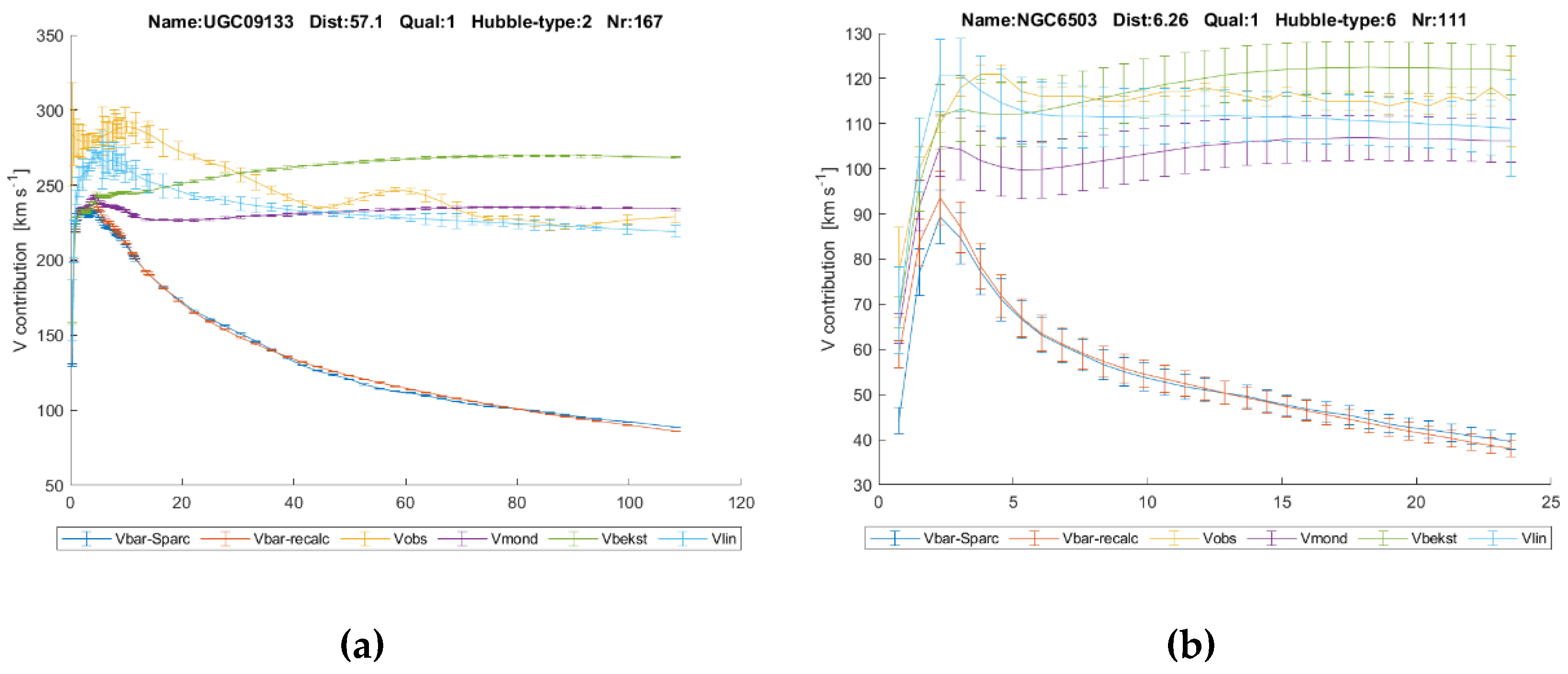

5.4.3 Strong Support for an Evolution in Time from Galaxy Clusters

Strong support for the predicted evolution in time comes from galaxy clusters. It will be shown the linear mass density here is vital to be able to significantly improve the predictions of the velocity dispersions. The clusters show velocity dispersions that depend on the gravitational potential and obey the Virial theorem, see Milgrom 2018 [

45]. Milgrom used data from NGC clusters only, but Tian, McGaugh et al in 2021 [

46] analyzed the much larger Abell clusters as well. The data of both sources have been combined in the graph down here in

Figure 12.

The Newtonian, and the MOND approach, as well as linear gravity will be elaborated and used to predict the dispersion velocities from the mass M and the diameter Rh of the clusters.

The Virial theorem states that if a spherical distribution of objects of equal mass is stable and self-gravitating (such as a galaxy cluster), the total gravitational potential energy, U, of the objects is equal to minus two times the total kinetic energy, T:

(36)

With U being the sum of all the dot products of the gravitational forces acting on test masses and the vectors to the mass center as follows:

(37)

With Newtonian gravity and with the commonly assumed ratio of 3 between the velocity dispersion and the line-of-sight velocity, that is the measured quantity, the following equation results for the line-of-sight velocity dispersions

σ, after Heisler et al in 1985 [

47]:

(38)

But, Milgrom has applied the Virial theorem to the MOND formula (5) for spherical clusters in Milgrom [

45]. For linear gravity it is simple to derive a comparable formulation from this, what will be done in the sequel. Milgrom’s formula for the dispersion velocity in a cluster is:

(39)

Since

G and

M and

am are just constants for a given cluster, for MOND works on the resulting gravitational acceleration from all the different masses on a test mass (and not on the separate contributions, so the square root in the next only applies to the sum), they can very well be replaced by another constant without changing the steps taken in the derivation by Milgrom [

45]. This will be done here. In the deep MOND regime the gravitational acceleration in a galaxy is

, whereas in the linear gravity formulation (10) for

N superposed masses this is

g = 2*N*GLM’/R, since the potential energies of

N times the visible mass add up, so this leads to:

(40)

However, so as to compare this with the said NGC and Abell data, the average linear mass density has to be expressed in the mass of the entire spherical cluster, so using M instead of M’, which is straightforward, since the average mass density of an 2-dimensional cross section, with average radius, through a sphere with uniform mass amounts . Inserting this in (40) gives:

(41)

Which closely resembles the Newtonian result (38), despite the fact that (41) was derived using MOND (!), so results from a logarithmic potential.

But this can as well be derived in a direct manner from the Virial theorem using the logarithmic potential of N times a hypothetical 2- dimensional disk that is consistent with linear gravity from formula (10), and down here it will be shown this gives the same result.

The total potential energy of the mass in a cluster U was formulated in equation (37) and with the potential (10) the Virial theorem from formula (36) yields:

(42)

Now, since in a line mass the vectors just point perpendicular to the line mass, taking the dot product is the same as multiplying with this distances , and differentiating the logarithm leads to the same distance in the denominator. So, this is canceled. And that, again with ratio of 3 between the velocity dispersion and the line-of-sight velocity, leads to:

(43)

Which results in the same as formula (40) that was derived from MOND. So, again, this formula closely resembles the result that follows from Newtonian gravity (38), with the same slope, but giving higher velocity dispersions as will be argued in the sequel. This is astonishing, since a logarithmic potential as in MOND in a spherical cluster leads to squared dispersion velocities that are proportional to the square root of M in formula (39) and linear gravity, which as well has a logarithmic potential, ends up with a very Newtonian-like result.

However, both said literature sources, as well as Banik [

2] reveal that when the Virial theorem is applied to the Newtonian potential, see formula (38) this needs significantly more mass than the visible to match the observed velocity dispersions. In conventional cosmology it is assumed the dark matter amounts to approximately six times the baryonic matter, but this does not suffice to bridge the gap, as is well shown in Tian, McGaugh et al [

46] This factor six has been applied to the data in the graph in

Figure 12 down here to yield the Newtonian velocity dispersions including the effect of dark matter. And, contrary to Milgrom’s findings for smaller and nearer by clusters (Milgrom 2018), the full range including the Abell clusters, reveals the MOND data are significantly lower than the observations in the Abell clusters and the corresponding curve in

Figure 12 does not have the right slope.

But, the paper in hand proposes a hybrid approach, in which the existence of dark matter is included. Therefore, in line with the Newtonian approach of conventional cosmology, much dark matter can be resident in the clusters, even much more than in the galaxies alone.

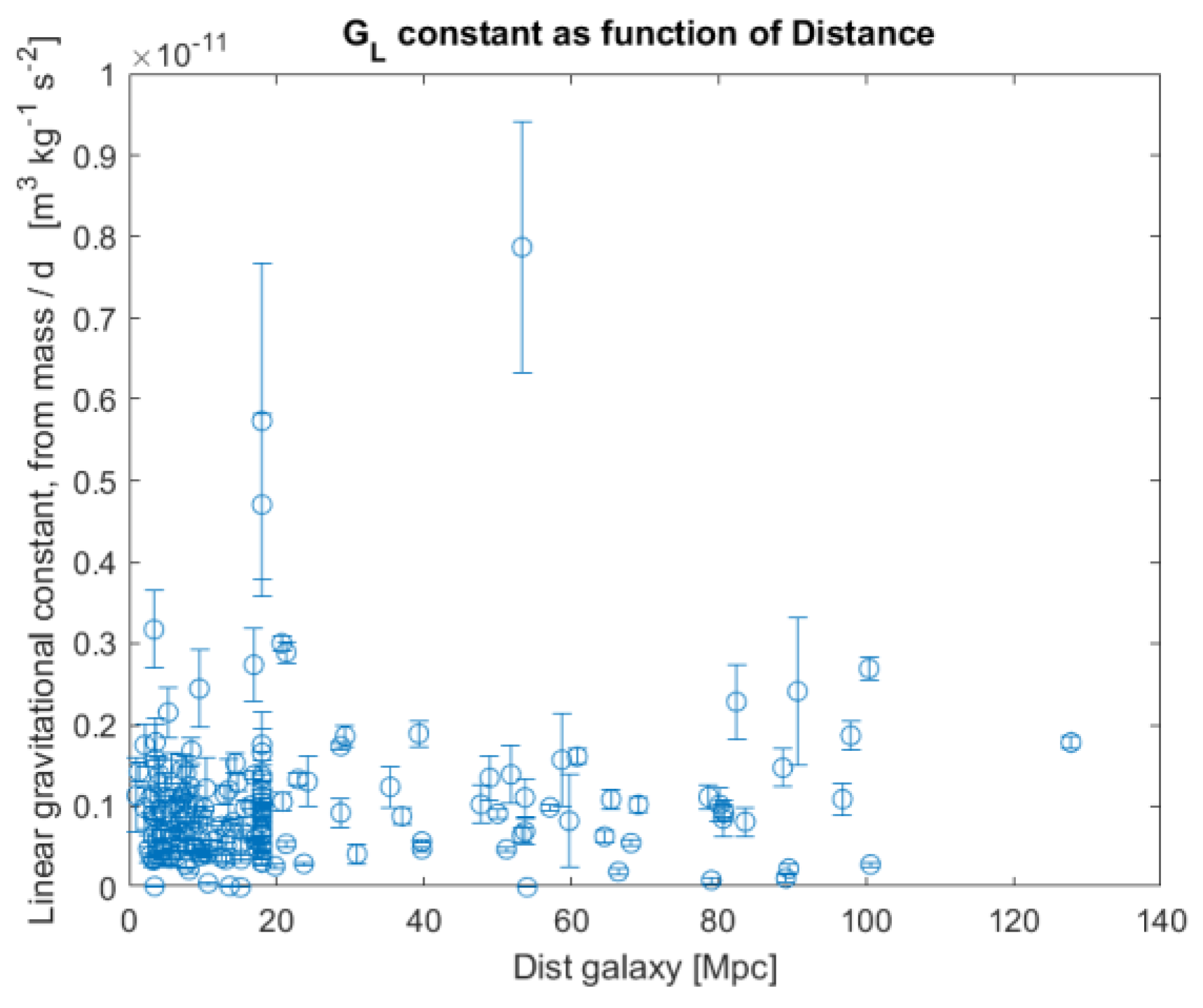

The theory in hand suggests this is dark matter diluted from the galaxies into the space between them. So, the essential idea here is the dark matter diluted from galaxies will still be in the clusters now. To give the best fit with the observations, an additional factor 104 has been assumed for this ratio. This means in this hybrid approach there is much more dark matter in the clusters than the dark matter that diluted from the galaxies only, which is credible. Now, the fundamental clue of all this is that this additional factor 104 exactly matches the ratio of GL/ G found in galaxies in chapter 5.3, assuming the number of superpositions N = 6, which was in line with the ratio of dark matter and baryonic matter in conventional cosmology!

In line with the elaboration at the start of this chapter, it is predicted dark matter diluted from the galaxies because of the expansion of space and hence the appearance of new space between the 2-dimensional cross sections of the universes. But, from the Nasa/Ipac Extragalactic Database it can be deduced the farthest Abell clusters are at a distance of approximately 1 Billion lightyears from ourselves, what corresponds with an expansion of space-time of approximately 2.5 % in that period of time, which is insufficient to give the effect visible in

Figure 12. But the factor 104 does.

This gives a reduction of the r.m.s. of the deviations from the observations of 44 % compared with both MOND and 57 % compared with the conventional Newtonian approach, see

Table 2.

The said additional factor of 104 on the amount of dark matter needed in clusters compared to that in the galaxies alone, is consistent with the hybrid approach of this paper in hand. The number of superposed universes, N, that lead to all this dark matter will be discussed in the next section. Given the ratio of GL/ G of approximately 104, it must be N = 6. See the next section. Roughly the same value will be derived in another way the sequel.