1. Introduction

The diagnosis of benign or malignant oral lesions and the diagnosis of malignancy in cancer or precancerous lesions relies on histopathological examination. In addition, early-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) has a good survival rate and quality of life (QOL) after treatment. Early diagnosis and treatment of lesions is desirable to improve the treatment outcome and prognosis of OSCC. For the diagnosis of early-stage oral cavity-related cancer and precancerous lesions, examination of lesions using an endoscope in addition to conventional macroscopic examination enables observation of lesions in close proximity and frontal observation of lesions in areas that cannot be observed with the macroscopic examination, which can lead to clearer decisions regarding treatment strategy.

Narrow band imaging (NBI), an optical image enhancement technique, is an endoscopic examination using special light, and in combination with magnification, enables detailed observation of dilated and irregular capillary vessels in the mucosa and submucosa for qualitative diagnosis of lesions, and also highlights microstructures on the mucosal surface. This enables appropriate diagnosis and early treatment, prevents progression to advanced cancer, and contributes to improved prognosis. In the future, it is also expected to be applied to endoscopic treatment of OPMDs and early-stage OSCC.

This article summarizes the selection of endoscopic instruments, observation methods, and endoscopic findings and their interpretations for NBI magnification of oral lesions, and provides useful information for actual clinical practice.

2. Current Status of Oral Endoscopy

The magnifying endoscope function was launched commercially by Olympus Medical Corporation in 1990, and has been used to this day. Currently, in endoscopic observation of oral lesions under special light, autofluorescence imaging (AFI) displays cancerous lesions as reddish purple with weak autofluorescence and normal mucosa as green with strong autofluorescence, confirming the presence of the lesion [

1]. Infra-Red Imaging (IRI) is a method in which blue coloration is observed in lesions after administration of indocyanine green (ICG) [

2]. However, it is not commonly used as a method to diagnose the primary lesion of oral cancer.

NBI is characterized by its ability to diagnose malignant or atypical lesions by using magnification of about 100x in addition to lesion detection. Furthermore, attempts have been reported to perform pathological diagnosis of oral mucosal lesions in real time using endocytoscopy, a contact-type light microscopy system with 380x magnification, to observe both structural and cytological atypia [

3].

3. Principle of NBI

NBI is an image enhancement function that uses two wavelengths, 415 nm and 540 nm, narrowed by a dedicated optical filter. Since the peak absorption region of oxidized hemoglobin in blood is 415 nm and 540 nm, and short wavelengths such as 415 nm and 540 nm are scattered in the superficial layers of biological tissues, NBI has an image enhancement function that improves the visibility of surface microstructure and microvasculature under an endoscope in combination with a magnifying endoscopy.

1) Non-magnification (diagnosis of the presence of tumor)

The effectiveness of NBI in non-magnification observation has been demonstrated in the pharyngeal and esophageal region with a high level of evidence. Superficially limited cancer of the head and neck and esophageal carcinoma (multiple superficial carcinomas in the esophagus) can be detected with significantly higher detection rate and diagnostic accuracy by NBI than by white light imaging [

4,

5].

2) Observation with magnification (qualitative and quantitative diagnosis of tumors)

NBI is highly effective for qualitative and quantitative diagnosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, gastric cancer, and colorectal tumors, because it enables observation of microvasculature and surface microstructure when used in combination with magnifying endoscopy. In the esophagus, observation of intraepithelial papillary capillary loop (IPCL) atypia by combination of NBI and magnification is effective not only for the diagnosis of cancerous or non-cancerous lesions but also for the diagnosis of extent and depth of the lesion [

4,

5].

4. Current Status of NBI Magnification Endoscopic Observation

NBI is a method that uses a special imaging technique to visualize mucosal and submucosal IPCL by magnifying the lesion and making it easier to identify early-stage cancers compared to conventional observation [

4]. According to a systematic review, NBI, along with white light imaging (WLI), is an important method to improve the diagnostic accuracy of head and neck cancer [

5,

6]. Furthermore, NBI magnification is characterized by its ability to diagnose atypia or grade of malignancy of the lesion in addition to the presence of the lesion. There are cases in which clinically malignant lesions are suspected, but biopsy tissue shows only inflammatory findings and no atypical or malignant cells are detected, resulting in cases being followed up. Since biopsy is based on a portion of the lesion and does not necessarily reflect the entire lesion, when NBI magnification endoscopy reveals Type III or higher findings, biopsy should be performed on suspicion of severe atypia; when Type II findings are present and biopsy results show only inflammatory findings, the patient should be followed up for a certain period of time. If a tumor is suspected in clinically, it is useful for both the patient and the clinician to perform a complete resection of the tumor in the early stage of the disease and to perform a histological examination of the entire tumor as a diagnostic treatment to confirm the diagnosis. In other words, this is the concept of early case detection and early treatment.

In oesophageal carcinoma, a squamous cell carcinoma of the same histological type as oral cancer, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy using NBI has been already performed in practice. In addition to detecting neoplastic lesions, its grade is diagnosed by NBI magnifying endoscopy, and endoscopic treatment may be performed without biopsy if superficially limited esophageal cancer is suspected. This is because biopsy scar can make endoscopic treatment difficult. Oral lesions are also highly malignant squamous cell carcinomas, and the prognosis is not good, it is important for dentists who treat oral malignant lesions to further promote NBI magnification endoscopy and to accumulate and review cases. Early detection and early treatment of malignant oral lesions can minimize the invasiveness of surgery on the lesions and greatly improve the prognosis.

5. NBI Magnification Endoscopy of Oral Lesions

The classification of the morphology of microvascular loops in the oral mucosa by NBI magnification endoscopy and its correlation with the atypia of lesions has been reported [

7,

8,

9]. NBI magnification endoscopy has been shown to be effective in detecting atypia/malignant lesions in the oral cavity and pharyngolarynx [

10,

11,

12]. NBI magnification endoscopy in the oral cavity has been reported to have higher sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy in the diagnosis of OSCC compared to WLI, and is useful for the recognition and accurate evaluation of neoplastic lesions in the oral cavity [

10,

13].

1) IPCL classification by NBI magnification endoscopy [

7,

8,

9]

IPCL is classified from Type 0 to IV.

Type 0: No vessels are observed due to normal mucosa or keratinization (

Figure 1).

Type I: Regular brown dots are observed when the IPCLs are perpendicular to the mucosa, and waved lines when running parallel. Most of the mucosa is normal (

Figure 2).

Type II: IPCL is dilated and a crossing. It is mainly at inflammatory sites or non-neoplastic lesions (

Figure 3).

Type III: IPCL is further elongation and meandering. Mainly seen in neoplastic lesions (

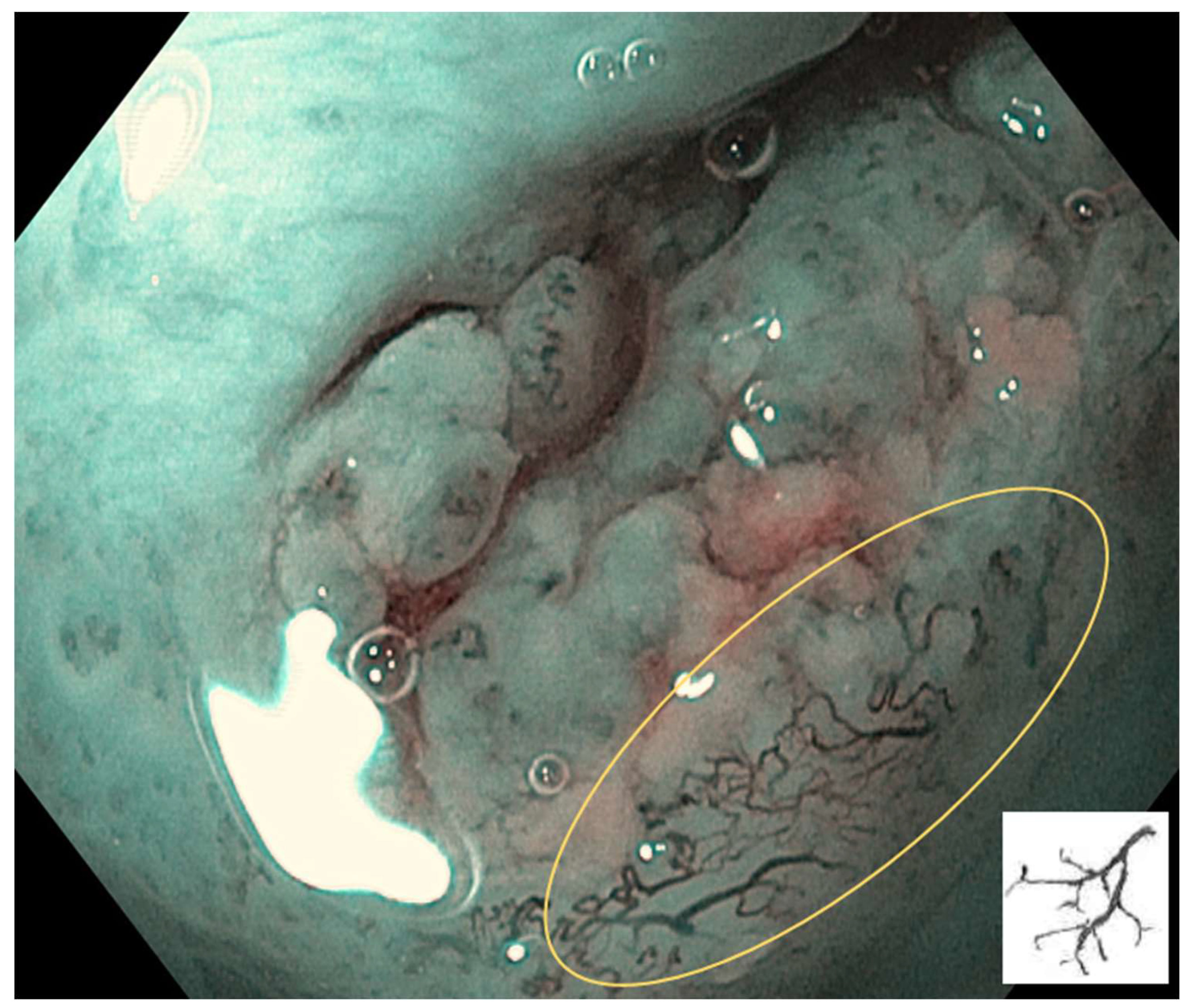

Figure 4).

Type IV: IPCL is characterised by large vessels, destruction of looped vascular structures, and angiogenesis. It presents in neoplastic lesions (

Figure 5).

2) Treatment of IPCL classification

It has been reported that 97.7% of IPCL Type 0, I and II were classified as non-neoplastic lesions (inflammation, etc.), while 78.9% of IPCL Type III and IV were neoplastic lesions [

14]. Furthermore, since Type IV is significantly associated with OSSC in IPCL with NBI magnification endoscopy, the detection of IPCL Type IV in the follow-up of oral lesions may indicate the presence of OSSC [

13].

6. Examination Procedures and Observation Methods

Regarding the indications and contraindications for the use of oral endoscopy, there are no restrictions to its use because the diagnosis is mainly made by intraoral observation. In patients taking anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs or with a bleeding tendency, some bleeding may occur when the endoscope comes into contact with the oral mucosa, but this is not a major problem and hemostasis is considered possible without invasive endoscopic procedures such as biopsy, but careful handling is required.

1) Pre-treatment

No dietary restrictions are required one day before the examination, and food intake on the day of the examination is not a problem if only oral observation is performed. Oral rinsing should be performed prior to the examination. Antispasmodics, sedatives, and analgesics are considered unnecessary.

2) Endoscopic instruments and observation methods

The endoscopic video scope systems EVIS LUCERA ELITE, CV-290 (EVIS LUCERA ELITE Video System Center), CLV-290 (EVIS LUCERA ELITE High Intensity Light Source), and GIF-H290Z upper gastrointestinal endoscope (Olympus Corporation) are used. The lesion can be observed with the macroscopic examination, normal light (white light), switched to NBI to observe the brwonish area, and magnified observation (up to 85x) to observe the mucosal and submucosal IPCL of the lesion and the microstructure of the mucosal surface in detail.

Specifically, the lesion is observed and photographed using white light to confirm the degree of erythema, surface irregularity, and extent of the lesion in the area of abnormal findings in the macroscopic examination. Next, the lesion is observed and photographed in the same procedure as white light by switching to NBI. The lesion center, lesion margins, and vascular structures (IPCL) at the border between the lesion and the normal mucosa are observed and photographed using the NBI magnification endoscopy. As the magnification function of the GIF-H290Z is capable of up to 85x, it should be used as appropriate for observation. It is also recommended to observe the lesion with a cap, but be careful of bleeding due to contact between the endoscope and the lesion. Iodine staining should be performed to confirm the lesion. Biopsy should be performed after endoscopic observation.

7. Interpretation of IPCL

Oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs), such as erythroplakia, erythromatous leukoplakia, leukoplakia, oral submucous fibrosis, and dyskeratosis congenita, are lesions or conditions that can lead to cancer. NBI magnification has been used for better assessment of OPMDs, identification of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and diagnosis of surgical margins of head and neck malignancies. NBI magnification has shown great potential to improve the detection rate of OPMDs, facilitate the evaluation of oral and oropharyngeal SCC, and reduce the risk of OSCC recurrence. Although further studies are needed to correlate IPCL with clinical, histopathologic, and molecular biological parameters, evidence is being proposed for a new gold standard of endoscopic evaluation in oral and head and neck oncology [

15,

16].

In oral lichen planus (OLP), the detection of IPCL Type III-IV on NBI is considered to be useful in the follow-up of malignant transformation of lesions [

17], and diffuse and severe chronic inflammation of OLP generally causes an abnormal vascular pattern [

18]. In oral leukoplakia, when high-grade IPCL is seen on NBI magnification, the risk of OSCC is high and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia tends to be malignant, suggesting that tumor angiogenesis preceding epithelial malignant transformation may be observed on NBI magnification [

19].

When the diagnostic accuracy of IPCL in detecting OPMDs was compared to conventional visual inspection (CVI), WLI and NBI, in OLP and leukoplakia a wide range of lesions could be identified using WLI or NBI compared to CVI, and NBI can detect lesions in larger areas compared to WLI. IPCL in OLP is Type 0-II in 75.0%, various IPCL is seen in leukaemia, and all cases of OSCC have Type III-IV IPCL [

20]. The diagnostic accuracy of OSCC was 100% sensitivity and 80.9% specificity, when severe IPCL was observed. The endoscopic observation of oral mucosal lesions is also useful to determine the margin of the lesions, and NBI magnification endoscopy of IPCL can be an important examination for the early detection of early OSCC in OPMDs lesions [

20,

21,

22].

According to a recent Systematic review, NBI magnification is an effective noninvasive method for identifying malignant transformation of OPMDs, and since detailed observation of the lesion may reveal the presence of neoplastic lesions, biopsy of oral lesions classified as IPCL Type II or higher is recommended for early and accurate diagnosis of atypical epithelium or OSCC [

16].

8. Limitations of NBI Magnification Endoscopy

Although NBI has proven to be an efficient diagnostic tool, NBI is inaccurate in thick keratinized mucosa because of the inability to observe blood vessels. A study using the vascular pattern around the lesion as an evaluation index showed that approximately 28% of thick, homogeneous vitiligo with IPCL Type I surrounding the lesion was actually accompanied by atypia [

23]. In addition, the presence of hemorrhage in the NBI field of view made it difficult to observe the IPCL [

24], and the ulcer surface of an oral ulcer lesion obscured the visualization of the IPCL. In normal mucosa, IPCL is difficult to observe on the dorsum of the tongue, hard palate, and gingiva, etc. Note that OLPs are commonly observed on the buccal mucosa and lower lip and are only recognised as lesions in areas where they can be visualised [

8,

20,

25].

9. Future Prospects

1) Screening of lesions

On WLI endoscopy, lesions of irregular surface and indistinct margins were observed in 56% of OLPs with keratinized white lesions in a background of redness of mucosa, and lesions of irregular surface of OSCC were observed in 92% with nodular or verrucous white lesions in a background of redness of mucosa. On the other hand, 84% of leukoplakia have smooth surfaces and circumscribed lesions. Therefore, the appearance of irregular surface in leukoplakia suggests the occurrence of OSCC. The details of the association between surface irregularities and IPCL have not been well known, but IPCL Type III is present in 25% of OLPs which might be reflect severe atypical lesions or OSCC.

Lesion sites of IPCL Type III or Type IV indicate the possible presence of malignancy, and therefore provide an indicator of the appropriate biopsy site and minimise multiple biopsies [

26]. For OPMDs, a strict diagnosis of IPCL and regular follow-up with NBI magnification endoscopy is necessary. It has been reported that lesions should be reevaluated by NBI one month after screening [

26].

2) Usefulness in dental health examination:

Based on the anatomical findings of the oral cavity, the oral mucosa is divided into 26 areas for macroscopic observation, endoscopic white light observation, and NBI magnification observation [

27]. The IPCLs in the areas where the lesions are confirmed by macroscopic examination and in the newly identified brownish areas are observed by NBI magnification endoscopy.

10. Conclusions

The IPCL classification of OPMDs and OSCC with NBI magnification endoscopy is the optimal approach for the early detection of malignant transformation of OPMDs. NBI magnification endoscopy is a relatively accurate and effective non-invasive diagnostic tool, and biopsy is strongly recommended for lesions diagnosed as IPCL Type II or higher. Further case studies are needed to confirm the accuracy of NBI magnification endoscopy for oral diseases. It is then expected that NBI magnification endoscopy will be widely used by dentists in hospitals and general dental clinics, and that advanced technologies such as the combination of NBI magnifying endoscopes and computer-aided diagnosis systems will be evaluated.

Author Contributions

Writing—review and editing, T.C., A.O., T.H., T.K., A.O. and H. Y.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Ikuya Miyamoto of Hokkaido University, Japan, for supporting the endoscopic findings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mat Lazim N, Kandhro AH, Menegaldo A, Spinato G, Verro B, Abdullah B. Autofluorescence image-guided endoscopy in the management of upper aerodigestive tract tumors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 20: 159.

- Iwamoto O, Kusukawa J. Observation of stage I and stage II oral squamous cell carcinoma using an endoscope with a built-in special light system (NBI, AFI, IRI). J Jpn Soc Oral Oncol 2013; 25: 72-88 (Article in Japanese with English Abstract).

- Miyamoto I, Yada N, Osawa K, Yoshioka I. Endocytoscopy for in situ real-time histology of oral mucosal lesions. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018; 47: 896-899. [CrossRef]

- Guida A, Ionna F, Farah CS. Narrow-band imaging features of oral lichenoid conditions: A multicentre retrospective study. Oral Dis 2021; 29: 764-771. [CrossRef]

- Muto M, Minashi K, Yano T, Saito Y, Oda I, Nonaka S, et al. Early detection of superficial squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region and esophagus by narrow band imaging: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1566-1572.

- Carreras-Torras C, Gay-Escoda C. Techniques for early diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma: Systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2015; 20: e305-e315.

- Takano JH, Yakushiji T, Kamiyama I, Nomura T, Katakura A, Takano N, Shibahara T. Detecting early oral cancer: narrowband imaging system observation of the oral mucosa microvasculature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 39: 208-213.

- Sekine R, Yakushiji T, Tanaka Y, Shibahara T. A study on the intrapapillary capillary loop detected by narrow band imaging system in early oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol 2015; 27: 624-630.

- Cozzani E, Russo R, Mazzola F, Garofolo S, Camerino M, Burlando M, Peretti G, Parodi A. Narrow-band imaging: a useful tool for early recognition of oral lichen planus malignant transformation? Eur J Dermatol 2019; 29: 500–506.

- Vu AN, Farah CS. Efficacy of narrow band imaging for detection and surveillance of potentially malignant and malignant lesions in the oral cavity and oropharynx: A systematic review. Oral Oncol 2014; 50: 413-420.

- Ansari UH, Wong E, Smith M, Singh N, Palme CE, Smith MC, Riffat F. Validity of narrow band imaging in the detection of oral and oropharyngeal malignant lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck 2019; 41: 2430-2440.

- Kim DH, Kim SW, Lee J, Hwang SH. Narrow-band imaging for screening of oral premalignant or cancerous lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 2021; 46: 501-507.

- Saraniti C, Greco G, Verro B, Lazim NM, Enzo Chianetta E. Impact of narrow band imaging in pre-operative assessment of suspicious oral cavity lesions: A systematic review. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol 2021; 33: 127-135. [CrossRef]

- Piazza C, Cocco D, Bon FD, Mangili S, Nicolai P, Peretti G. Narrow band imaging and high definition television in the endoscopic evaluation of upper aero-digestive tract cancer. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2011; 31: 70-75.

- Vu A, Fara CS. Narrow band imaging: clinical applications in oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Diseases 2016; 22: 383-390. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Wu Y, Pan D, Zhang Z, Jiang L, Feng X, Jiang Y, Luo X, Chen Q. Accuracy of narrow band imaging for detecting the malignant transformation of oral potentially malignant disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Surg 2023; 9: 1068256. [CrossRef]

- Guida A, Maglione M, Crispo A, Perri F, Villano S, Pavone E, Aversa C, Longo F, Feroce F, Botti G, Ionna F. Oral lichen planus and other confounding factors in narrow band imaging (NBI) during routine inspection of oral cavity for early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective pilot study. BMC Oral Health 2019; 19: 70. [CrossRef]

- Yang SW, Lee YS, Chang LC, Hwang CC, Chen TA. Use of endoscopy with narrow-band imaging system in detecting squamous cell carcinoma in oral chronic non-healing ulcers. Clin Oral Investig 2014; 18: 949–59.

- Abadie WM, Partington EJ, Fowler CB, Schmalbach CE. Optimal management of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015; 153: 504-511.

- Ota A, Miyamoto I, Ohashi Y, Chiba T, Takeda Y, Yamada H. Diagnostic accuracy of high-grade intraepithelial papillary capillary loops by narrow band imaging for early detection of oral malignancy: A cross-sectional clinicopathological imaging study. Cancers 2022; 14: 2415. [CrossRef]

- Hande AH, Mohite DP, Chaudhary MS, Patel M, Agarwal P, Bohra S. Evidence based demonstration of the concept of “field cancerization” by p53 expression in mirror image biopsies of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma—An immunohistochemical study. Rom J Morphol Embryol Rev 2015; 56: 1027-1033.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer 1953; 6: 963-968.

- Piazza C, Bon FD, Paderno A, Grazioli P, Perotti P, Barbieri D, Majorana A, Bardellini E, Peretti G, Nicolai P. The diagnostic value of narrow band imaging in different oral and oropharyngeal subsites. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016; 273: 3347-3353. [CrossRef]

- Vilaseca I, Valls-Mateus M, Nogués A, Lehrer E, López-Chacón M, Avilés-Jurado FX, Blanch JL, Bernal-Sprekelsen M. Usefulness of office examination with narrow band imaging for the diagnosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and follow-up of premalignant lesions. Head Neck 2017; 39: 1854-1863. [CrossRef]

- Kurihara Y, Hatori M, Kanazuka A, Nagumo T, Shirota T, Shintani S. Narrow band imageing of oral mucosa, cancer and pre-cancerous lesions. Dental Med Res 2010; 30: 237-242.

- Farah CS, Dalley AJ, Nguyen P, Batstone M, Kordbacheh F, Perry-Keene J, Fielding D. Improved surgical margin definition by narrow band imaging for resection of oral squamous cell carcinoma: A prospective gene expression profiling study. Head Neck 2016; 38: 832-839.

- Ota Y, Noguchi T, Ariji E, Fushimi C, Fuwa N, Harada H, Hayashi T, Hayashi R, Honma Y, Miura M, Mori T, Nagatsuka H, Okura M, Ueda M, Uzawa N, Yagihara K, Yagishita H, Yamashiro M, Yanamoto S, Kirita T, Scientific Committee on General Rules for Clinical and Pathological Studies of Oral Cancer, Japanese Society of Oral Oncology. General rules for clinical and pathological studies on oral cancer (2nd edition): a synopsis. Int J Clin Oncol 2021; 26: 623-635.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).