Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Disclaimer

Introduction

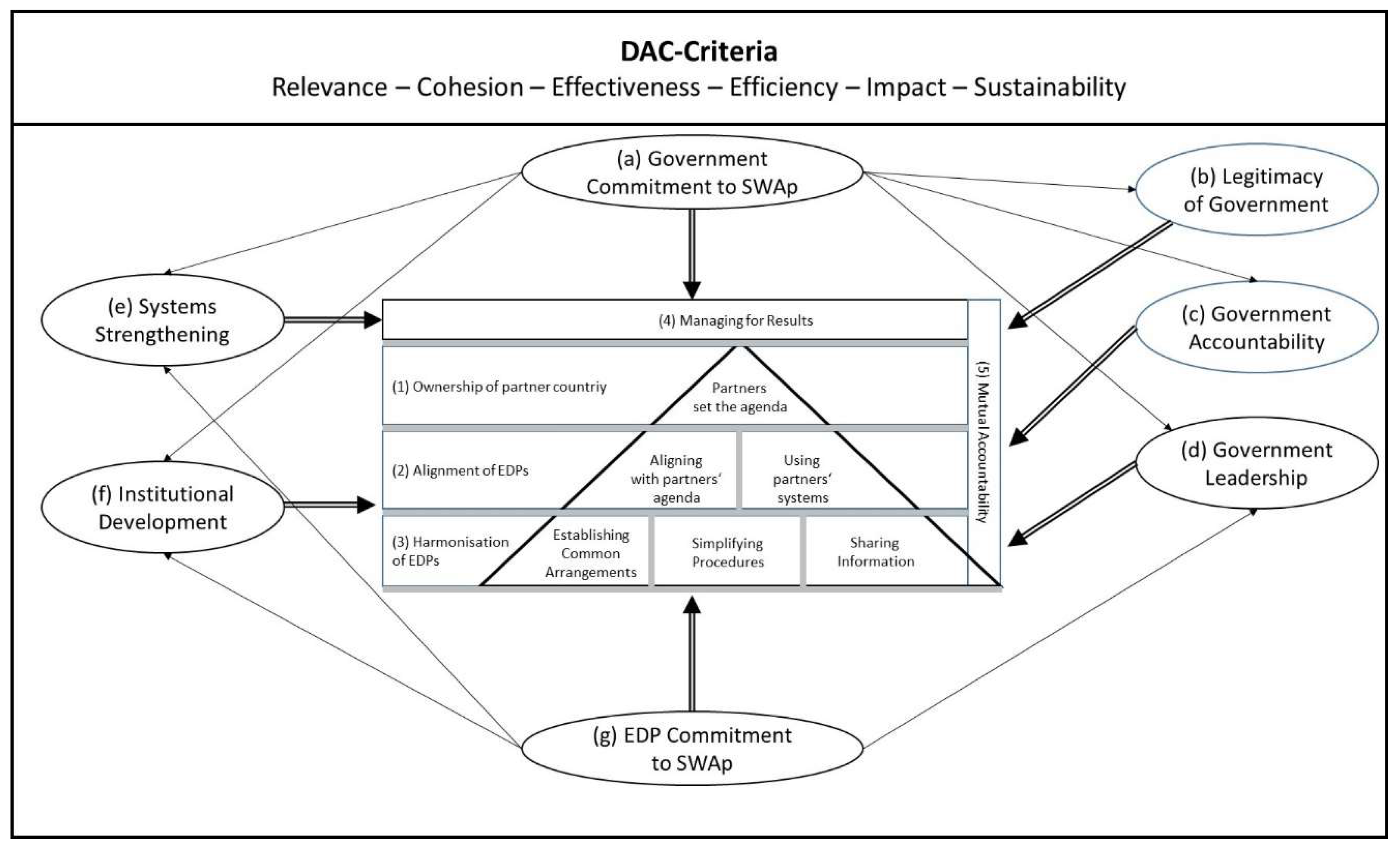

Methods

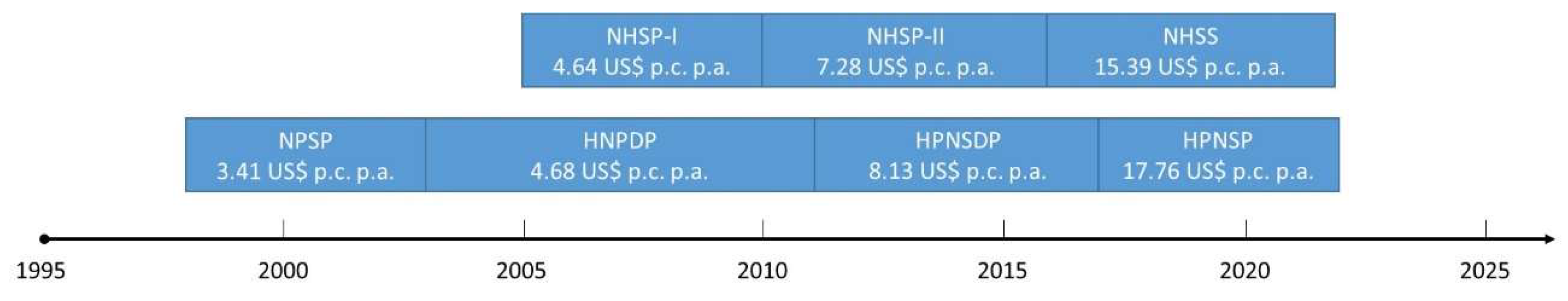

Setting

Mixed-Methods Evaluation

Results

Relevance

Cohesion

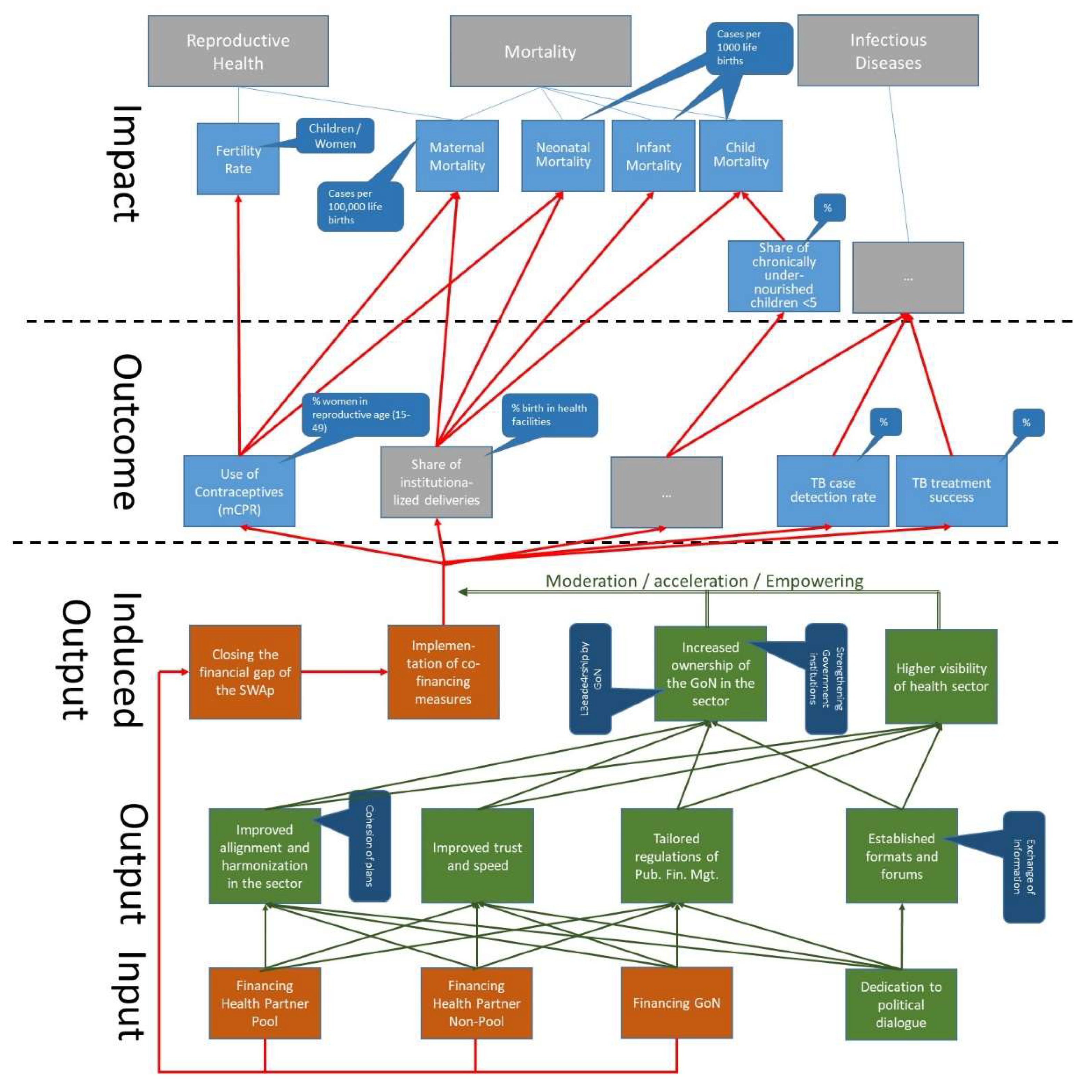

Effectiveness

Efficiency

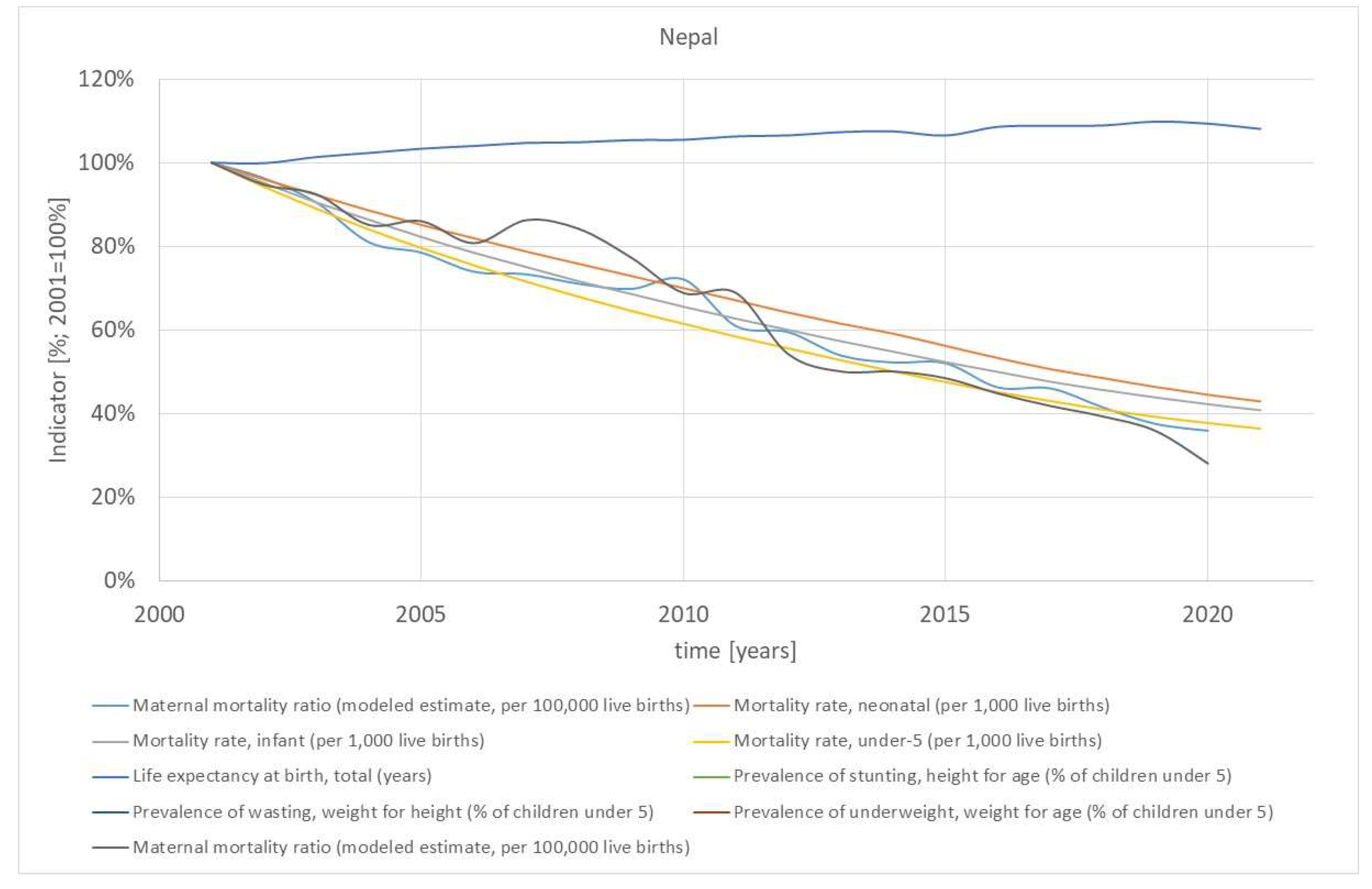

Impact

Sustainability

Discussion

State-of-the-Art

Advantages and Disadvantages of SWAps

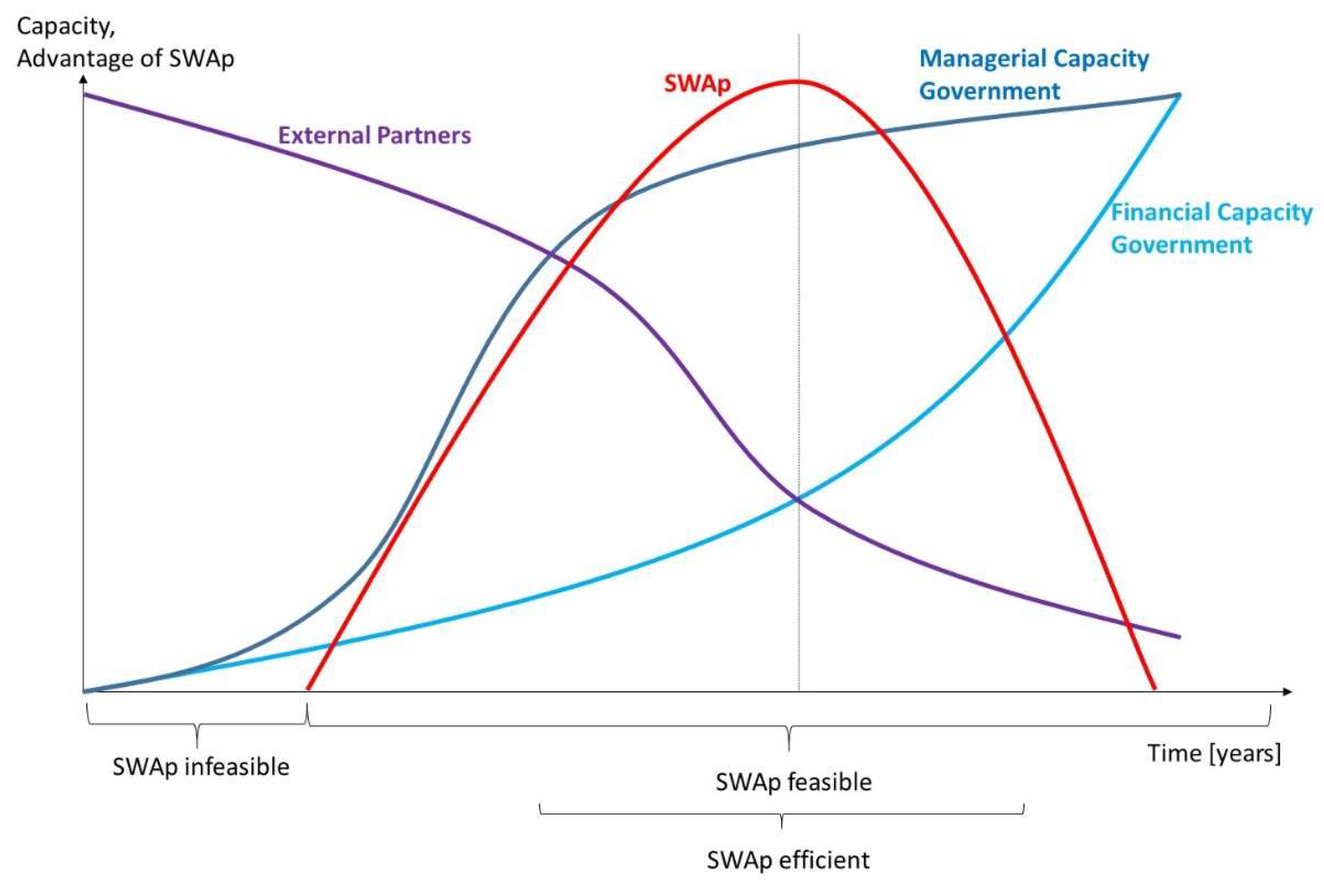

“Best” time for SWAps

Limitations

Conclusions

References

- Ahsan, K. Z., Streatfield, P. K., Ijdi, R.-E.-., Escudero, G. M., Khan, A. W., & Reza, M. (2016). Fifteen years of sector-wide approach (SWAp) in Bangladesh health sector: an assessment of progress. Health Policy Plan, 31(5), 612-623. [CrossRef]

- Akram, R., Sultana, M., Ali, N., Sheikh, N., & Sarker, A. R. (2018). Prevalence and determinants of stunting among preschool children and its urban–rural disparities in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull, 39(4), 521-535. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaman, M. S. (2020). Healthcare crisis in Bangladesh during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(4), 1357.

- Biswas, T., Islam, M. S., Linton, N., & Rawal, L. B. (2016). Socio-economic inequality of chronic non-communicable diseases in Bangladesh. PLoS One, 11(11), e0167140. [CrossRef]

- Cassels, A. (1997). A guide to sector-wide approaches for health development: concepts, issues and working arrangements. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Chansa, C., Sundewall, J., McIntyre, D., Tomson, G., & Forsberg, B. C. (2008). Exploring SWAp's contribution to the efficient allocation and use of resources in the health sector in Zambia. Health Policy Plan, 23(4), 244-251.

- Chianca, T. (2008). The OECD/DAC criteria for international development evaluations: An assessment and ideas for improvement. Journal of Multidisciplinary Evaluation, 5(9), 41-51. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R., & Sarkar, M. (2018). Education in Bangladesh: Changing contexts and emerging realities. Engaging in educational research: Revisiting policy and practice in Bangladesh, 1-18.

- D’Aquino, L., Pyone, T., Nigussie, A., Salama, P., Gwinji, G., & van den Broek, N. (2019). Introducing a sector-wide pooled fund in a fragile context: mixed-methods evaluation of the health transition fund in Zimbabwe. BMJ Open, 9(6), e024516. [CrossRef]

- Dabelstein, N., & Patton, M. Q. (2013). The Paris declaration on aid effectiveness: History and significance. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 27(3), 19-36. [CrossRef]

- Department of Health Services. (2021). Annual Report 2019/20. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal Retrieved from https://dohs.gov.np/category/annual-report/.

- Devnath, P., Hossain, M. J., Emran, T. B., & Mitra, S. (2022). Massive third-wave COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh: A co-epidemic of dengue might worsen the situation (Vol. 17, pp. 347-350): Future Medicine.

- Dhungel, K. R. (2022). Income Inequality in Nepal. Law and Economy, 1(3), 51-54. [CrossRef]

- Exemplars. (2024). Why is Bangladesh an Exemplar? Retrieved from https://www.exemplars.health/topics/neonatal-and-maternal-mortality/bangladesh/why-is-bangladesh-an-exemplar.

- Fendall, N. R. (1978). Declaration of Alma-Ata. Lancet, 2(8103), 1308. [CrossRef]

- Foster, M., Brown, A., Conway, T., & Organization, W. H. (2000). Sector-wide approaches for health development: a review of experience.

- Howell, J. M., & Higgins, C. A. (1990). Champions of technological innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 317-341. [CrossRef]

- Huda, T. M., Hayes, A., El Arifeen, S., & Dibley, M. J. (2018). Social determinants of inequalities in child undernutrition in Bangladesh: A decomposition analysis. Matern Child Nutr, 14(1), e12440. [CrossRef]

- IHME. (2023). Financing Global Health 2021: Global Health Priorities in a Time of Change. Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington.

- Joarder, T., Sutradhar, I., Hasan, M. I., & Bulbul, M. M. I. (2020). A record review on the health status of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Cureus, 12(8).

- m4H. (2023). SSK (Shasthyo Surokhsha Karmasuchi) Social Health Protection Scheme, Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://m4health.pro/ssk-shasthyo-surokhsha-karmasuchi-social-health-protection-scheme-bangladesh/.

- Mayring, P. (2021). Qualitative Content Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide. Los Angeles et al.: SAGE.

- Ministry of Finance. (2018). An Assessment of Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) in Health and Education Sectors of Nepal. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- Ministry of Health. (2004). Nepal Health Sector Programme Implementation Plan 2004-2009. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2011). Health Policy 2011. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2013). Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Key Indicators Report. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2019). Bangladesh National Strategy for Material Health (2019-2030). Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2023). Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2022. Key Indicators Report. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh.

- Ministry of Health and Population. (2015). National Health Sector Strategy 2015-2020. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- Ministry of health and Population. (2017). Annual Progress Report of Health Sector Fiscal Year 2015/16. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- Ministry of Health and Population. (2021). Progress of the Health and Population Sector, 2020/21. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- Ministry of Health and Population. (2022). Demographic and Health Survey 2022. Key Indicators Report. Kathmandu: Nepal.

- Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal Health Research Council, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, & UKaid. (2021). Nepal Burden of Disease 2019. A Country Report based on the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- MOHFW. (2012). Expanding Social Protection for Health Towards Universal Coverage – Health Financing Strategy 2012-2032. Dhaka: Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh.

- MOHFW. (2017). Report on End-Line Evaluation of Health, Population and Nutrition Sector Development Program (HPNSDP) July 2011- December 2016. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh.

- Natuzzi, E. S., & Novotny, T. (2014). Sector wide approaches in health care: do they work? Global Health Governance, 8(1).

- OECD, D. (2005). Paris declaration on aid effectiveness. http://www1. worldbank. org/harmonization/Paris/FINALPARISDECLARATION. pdf.

- Peters, D., & Chao, S. (1998). The sector-wide approach in health: What is it? Where is it leading? Int J Health Plann Manage, 13(2), 177-190.

- Peters, D. H., Paina, L., & Schleimann, F. (2013). Sector-wide approaches (SWAps) in health: what have we learned? Health Policy Plan, 28(8), 884-890.

- Pfeiffer, J., Gimbel, S., Chilundo, B., Gloyd, S., Chapman, R., & Sherr, K. (2017). Austerity and the “sector-wide approach” to health: The Mozambique experience. Soc Sci Med [Med Econ], 187, 208-216.

- Planning Commission. (2015). National Social Security Strategy. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh.

- Rabinowitz, G. (2015). The Power of Owernship. Literature Review on aid ownership and participation. London: Overseas Development Institute report.

- Thapa, R., van Teijlingen, E., Regmi, P. R., & Heaslip, V. (2021). Caste exclusion and health discrimination in South Asia: A systematic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 33(8), 828-838. [CrossRef]

- Titumir, R. A. M. (2021). Poverty and inequality in Bangladesh. In R. A. M. Titumir (Ed.), Numbers and narratives in Bangladesh's economic development (pp. 177-225). Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Toolan, M., Barnard, K., Lynch, M., Maharjan, N., Thapa, M., Rai, N., . . . Burden, C. (2022). A systematic review and narrative synthesis of antenatal interventions to improve maternal and neonatal health in Nepal. AJOG Global Reports, 2(1), 100019. [CrossRef]

- Umesh, G., Jyoti, M., Arun, G., Sabita, T., Yogendra, P., & Tesfayi, G. (2019). Inequalities in health outcomes and access to services by caste/ethnicity, province, and wealth quintile in Nepal. . DHS Further Analysis Report, 117.

- Umesh, G., Jyoti, M., Arun, G., Sabita, T., Yogendra, P., & Tesfayi, G. (2019). Inequalities in health outcomes and access to services by caste/ethnicity, province, and wealth quintile in Nepal. DHS Further Analysis Report(117).

- UNDP. (2023). Human Development Index. Retrieved from https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI.

- UNFPA. (2005). Sector Wide Approaches: A Resource Document for UNFPA Staff. United Nations Population Fund. New York.

- UNICEF. (2018). Health Expenditure Brief. Kathmandu: UNICEF Nepal.

- Upreti, S., Baral, S., Tiwari, S., Elsey, H., Aryal, S., Tandan, M., . . . Lievens, T. (2012). Rapid Assessment of the Demand Side Financing Schemes: Aama programme and 4ANC, 2012. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal; HERD.

- USAID. (2021). USAID Bangladesh Health Strategy 2022-2027. Dhaka: USAID.

- Vaillancourt, D. (2009). Do Health Sector-Wide Approaches Achieve Results? : Washington, DC: World Bank.

- WHO. (2010). Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2014). WHO Country Cooperation Strategy: Bangladesh 2014-2017. (9290224533). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2019). Declaration of Astana: Global Conference on Primary Health Care: Astana, Kazakhstan, 25 and 26 October 2018. Retrieved from Geneva.

- Whyle, E. B., & Olivier, J. (2016). Models of public–private engagement for health services delivery and financing in Southern Africa: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan, 31(10), 1515-1529. [CrossRef]

- WID. (2023). Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://wid.world/country/bangladesh/.

- Woode, M. E., Mortimer, D., & Sweeney, R. (2021). The impact of health Sector-Wide approaches on aid effectiveness and infant mortality. J Int Dev, 33(5), 826-844. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2017). Bangladesh - Health Sector Development Program Project. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/201211514407103482/Bangladesh-Health-Sector-Development-Program-Project.

- World Bank. (2023a). The World Bank In Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/bangladesh/overview.

- World Bank. (2023b). World Development Indicators. Retrieved from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#.

| Method | Horizon | Content | Ownership | Target | Coordination | Financing | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project | fixed | tailor-made intervention with limited scope | can be external development partner | specific challenge | limited | one source or consortium | poor coordination and alignment, poor sustainability, poor ownership |

| Program | until problem is solved or taken over | tailor-made intervention with broader scope | can be external development partner | specific challenge | limited | one source or consortium | poor coordination and alignment, medium sustainability, poor ownership |

| Sector-wide program | phases of a continuous sector program | entire sector | Government | entire health sector | completely within health sector | basket financing or single donor trust fund | limited control by external development partners |

| General budget support | annual support | entire Government | Government | all sectors | completely with all sectors | non-earmarked budget | very limited control by external development partners |

| Indicator | Value 2011 | Objective | Latest Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of contraceptives (CPR; % women in reproductive age (15-49 years) [%] | 62 % | 72 % | 63 % (2019) |

| Share of safe deliveries (births with professional support) [%] | 26 % | 50 % | 59 % (2019) |

| Vitamin A Supplement (share of children from 6-59 months receiving Vitamin A during the last six months) [%] | 83 % | 90 % | 97 % (2020) |

| Breast-Feeding (Share of children ≤ 6 months fully breast-fed) [%] | 43 % | 50 % | 63 % (2019) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).