Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Migration, Displacement and Health in the SDGs

1.2. Determining Health in Contexts of Displacement

1.3. A Whole-of-Route, Rights-Based Approach to Health and Displacement

1.4. Governance Gaps, Implementation Voids and Static Responses

- To review relevant global, continental, regional governance frameworks related to UHC alongside national legislation, policy and frameworks for each country;

- To examine the lived experiences of interviewed healthcare professionals and policy-makers (n=70) engaged with displacement and health, with attention to legal status, gender, and mental health across the four countries; and

- To identify legal, operational, and governance gaps, and propose actionable recommendations for inclusive, migrant-aware health system reform.

2. Methodology

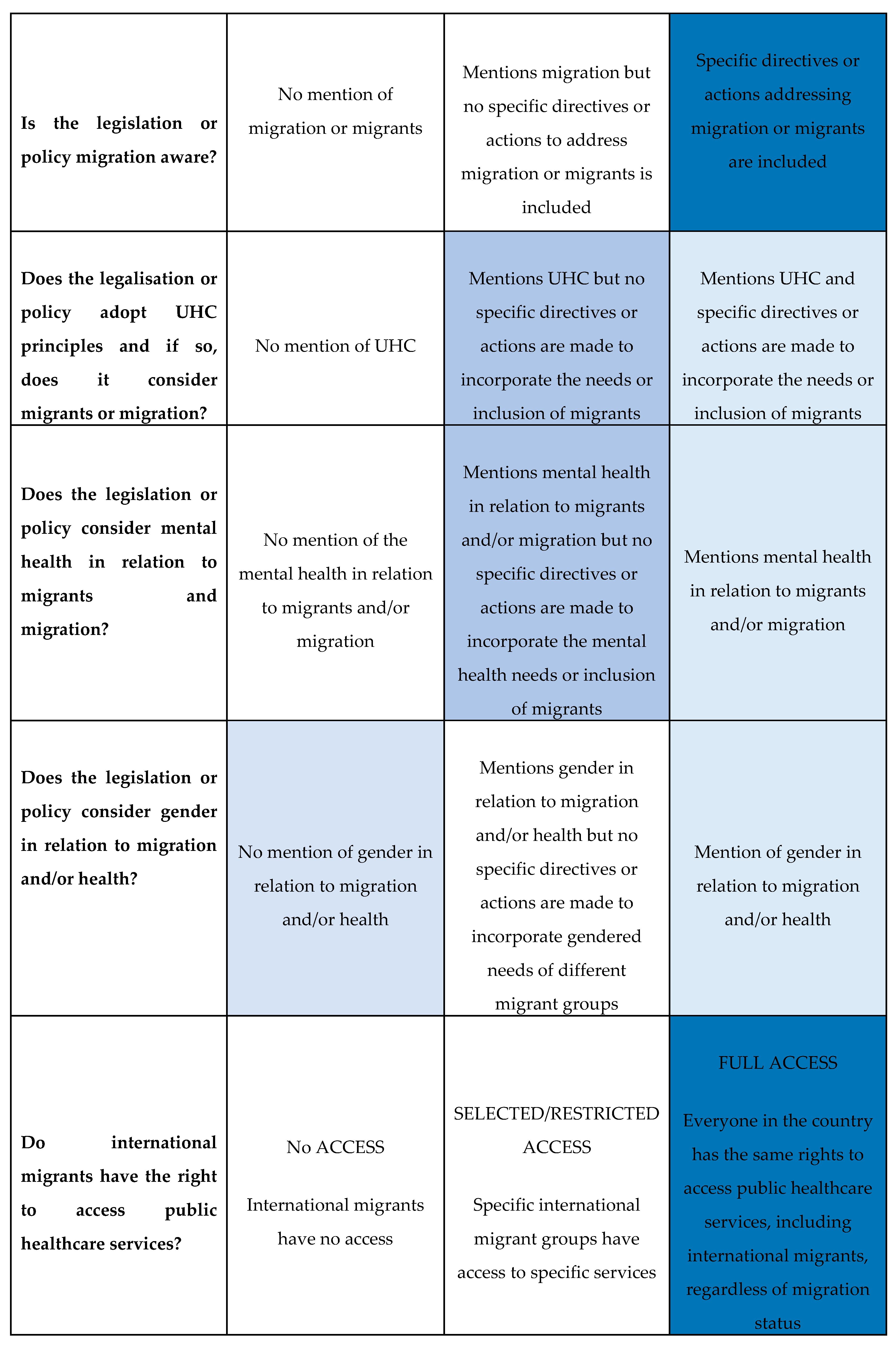

2.1. Policy and Legislative Review

- 1)

- Recognised and provided the right to health for migrants and displaced populations;

- 2)

- Integrated migration into healthcare planning and implementation (through access to public healthcare services);

- 3)

- Addressed mental health and psychosocial support within broader health system strategies;

- 4)

- Incorporated gender-sensitive approaches, including protection for displaced women, girls and, other gender-diverse groups.

2.2. Key Informant Interviews (KIIs)

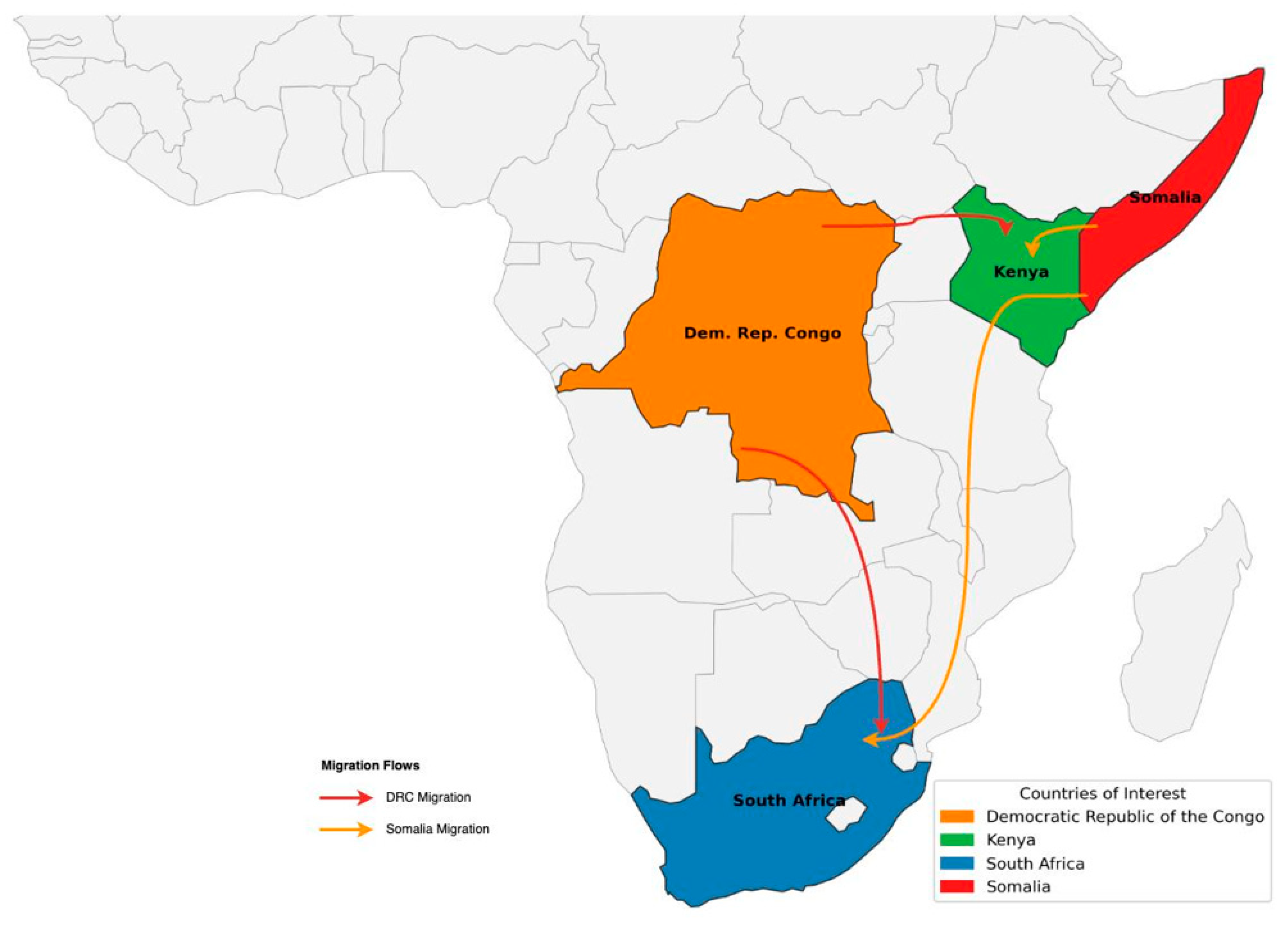

- DRC: 32 interviews (national and provincial levels)

- Somalia: 12 interviews (federal and state levels)

- Kenya: 25 interviews (national and subnational levels)

- South Africa: 25 interviews (national, provincial and local levels)

3. Results

3.1. The Migration, Displacement and Health Governance Ecosystem: Global, Continental and Regional

3.1.1. Global Frameworks

3.1.2. Continental Level: The African Union

3.1.3. Regional Governance Frameworks: Southern and Eastern Africa

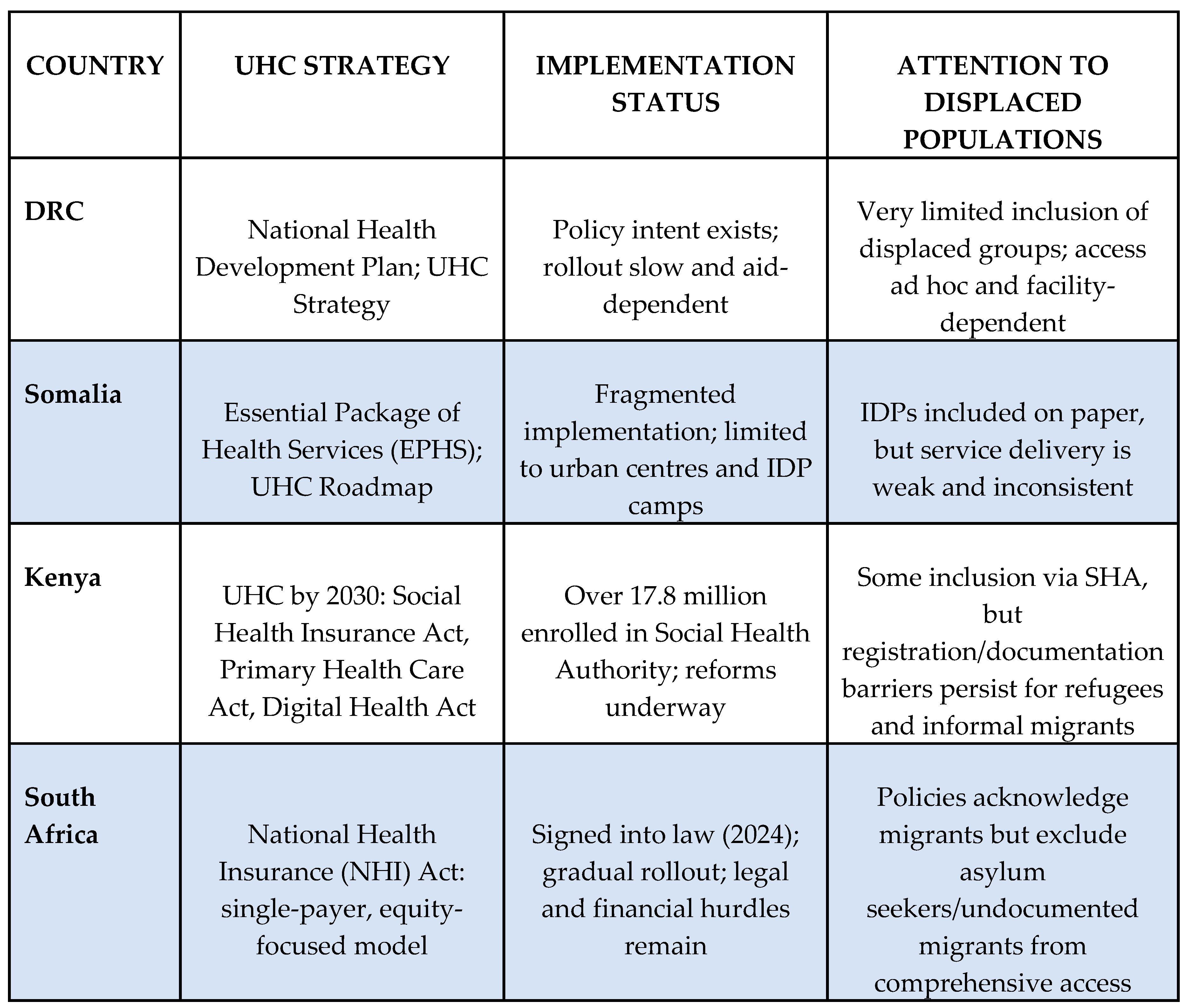

3.2. Upholding the Right to Health for Displaced Populations in the DRC, Somalia, Kenya and South Africa

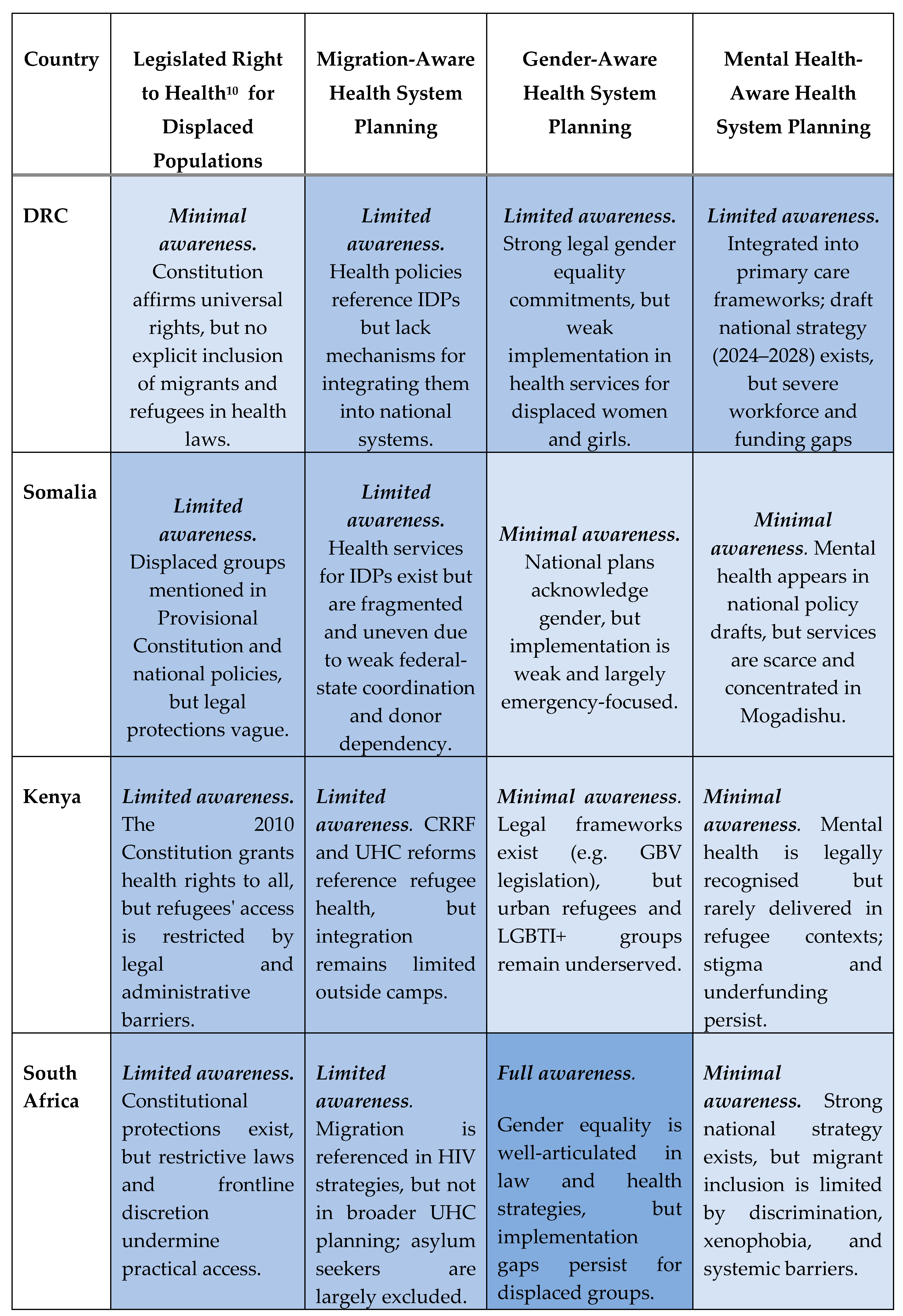

3.2.1. Upholding the Right to Health for Displaced Populations

3.2.2. Migration-Aware Health Systems Planning

3.2.3. Mental Health Aware Health Systems Planning

3.2.4. Gender-Aware Health Systems Planning

4. Discussion

- 1)

- Gaps between UHC commitments and healthcare access for displaced populations;

- 2)

- Limited integration of migration into national health system planning;

- 3)

- Neglect of mental health needs among displaced communities;

- 4)

- Lack of gender-sensitive health programming; and

- 5)

- Structural barriers to care.

4.1. Gaps Between UHC Commitments and Healthcare Access for Displaced Populations

4.1.1. Lack of Migration-Awareness in Health Systems Planning

4.1.2. Neglect of Mental Health Needs Among Displaced Populations

4.1.3. Lack of Gender-Sensitive Health Programming

4.1.4. Structural Barriers to Inclusive Health Systems

5. Conclusion

5.1. Disconnections and Contradictions Within and Between Governance Frameworks Undermine the Right to Health for Displaced Populations

5.2. Rights-Based Approaches While Critical, Are Limited on Their Own

5.3. Migration-Aware, Whole-of-Route Approaches Are Essential to Advance UHC and Uphold the Right to Health for Displaced People

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1 2015.

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. The SDGs and the UN Summit of the Future: Sustainable Development Report 2024; Dublin University Press: Dublin, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mosler Vidal, E. Leave No Migrant Behind: The 2030 Agenda and Data Disaggregation; International Organization for Migration (IOM): Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IOM Glossary on Migration; International Organization for Migration: Geneva, 2019.

- UNHCR Asylum-Seekers. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/about-unhcr/who-we-protect/asylum-seekers (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- UNHCR Refugees. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/about-unhcr/who-we-protect/refugees (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- OHCHR About Internally Displaced Persons. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-internally-displaced-persons/about-internally-displaced-persons (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- ODI Migration and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Overseas Development Institute: London, 2017.

- Adger, W.N.; Fransen, S.; Safra de Campos, R.; Clark, W.C. Migration and Sustainable Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121, e2206193121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W.N.; Boyd, E.; Fábos, A.; Fransen, S.; Jolivet, D.; Neville, G.; Campos, R.S. de; Vijge, M.J. Migration Transforms the Conditions for the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e440–e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosler Vidal, E.; Laczko, F. Migration and the SDGs: Measuring Progress – An Edited Volume; International Organization for Migration (IOM): Geneva, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Migration and the 2030 Agenda. A Guide for Practitioners; IOM: Geneva, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration - A/RES/73/195 2018.

- United Nations Global Compact on Refugees - A/73/12 2018.

- UNHCR How the SDGs and the GCR Are Aligned; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, undated.

- Oelgemöller, C. The Global Compacts, Mixed Migration and the Transformation of Protection. Interventions 2021, 23, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maple, N.; Reardon-Smith, S.; Black, R. Immobility and the Containment of Solutions: Reflections on the Global Compacts, Mixed Migration and the Transformation of Protection. Interventions 2021, 23, 326–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pécoud, A. Narrating an Ideal Migration World? An Analysis of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. Third World Q. 2021, 42, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanopoulos, E.; Guild, E.; Weatherhead, K. Securitisation of Borders and the UN’s Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, I.; Zumla, A. Universal Health Coverage for Refugees and Migrants in the Twenty-Firs t Century. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 216–s12916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oraibi, A.; Martin, C.A.; Hassan, O.; Wickramage, K.; Nellums, L.B.; Pareek, M. Migrant Health Is Public Health: A Call for Equitable Access to COVID- 19 Vaccines. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan, E.; Dhavan, P.; Fortier, J.P.; Mosca, D.; Weekers, J.; Wickramage, K.P. Migration and Health in the Sustainable Development Goals. Migr. 2030 Agenda 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bartovic, J.; Datta, S.S.; Severoni, S.; D’Anna, V. Ensuring Equitable Access to Vaccines for Refugees and Migrants during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 3–3A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM Recommendations on Access to Health Services for Migrants in an Irregu Lar Situation: An Expert Consensus. 2016.

- IOM. Migration Health in the Sustainable Development Goals: ‘Leave No One B Ehind’ in an Increasingly Mobile Society; IOM MIGRATION HEALTH DIVISION: Position Paper; IOM: Geneva, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Migrants’ Right to Health – Legal and Policy Instruments Related to Mi Grants’ Access to Health Care, Social Protection and Labour in Selecte d East African Countries; International Organization for Migration: Geneva, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; Pocock, N.; Tan, S.T.; Pajin, L.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Wickramage, K.; McKee, M.; Pottie, K. Healthcare Is Not Universal If Undocumented Migrants Are Excluded. BMJ 2019, 366, l4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, D.T.; Vearey, J.; Orcutt, M.; Zwi, A.B. Universal Health Coverage: Ensuring Migrants and Migration Are Include d. Glob. Soc. Policy 2020, 20, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onarheim, K.H.; Melberg, A.; Meier, B.M.; Miljeteig, I. Towards Universal Health Coverage: Including Undocumented Migrants. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e001031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulloch, O.; Machingura, F.; Melamed, C. Health, Migration and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Overseas Development Institute: London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vearey, J.; Hui, C.; Wickramage, K. Chapter 7. Migration and Health: Current Issues, Governance and Knowle Dge Gaps’. In WORLD MIGRATION REPORT; 2020; p. 38.

- Wickramage, K.; Vearey, J.; Zwi, A.B.; Robinson, C.; Knipper, M. Migration and Health: A Global Public Health Research Priority. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumla, A. Universal Health Coverage for Refugees and Migrants in the Twenty-Firs t Century. PubMed Cent. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM Recommendations on Access to Health Services for Migrants in an Irregular Situation: An Expert Consensus 2016.

- Adnan, S.A. Barriers to Healthcare Access by Undocumented Migrants in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Systematic Review. 2023.

- Adrian Parra, C.; Stuardo Ávila, V.; Contreras Hernández, P.; Quirland Lazo, C.; Bustos Ibarra, C.; Carrasco-Portiño, M.; Belmar Prieto, J.; Barrientos, J.; Lisboa Donoso, C.; Low Andrade, K. Structural and Intermediary Determinants in Sexual Health Care Access in Migrant Populations: A Scoping Review. Public Health 2024, 227, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Common Health Needs of Refugees and Migrants: Literature Review; WHO: Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization World Report on the Health of Refugees and Migrants; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-005446-2.

- Viruell-Fuentes, E.A.; Miranda, P.Y.; Abdulrahim, S. More than Culture: Structural Racism, Intersectionality Theory, and Immigrant Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruth, L.; Martinez, C.; Smith, L.; Donato, K.; Piñones-Rivera, C.; Quesada, J. Structural Vulnerability: Migration and Health in Social Context. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e005109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willen, S.S.; Knipper, M.; Abadía-Barrero, C.E.; Davidovitch, N. Syndemic Vulnerability and the Right to Health. The Lancet 2017, 389, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormond, M.; Lunt, N. Transnational Medical Travel: Patient Mobility, Shifting Health System Entitlements and Attachments. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 0, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, C.; Libuy, M.; Moreno-Serra, R. What Is the Impact of Forced Displacement on Health? A Scoping Review. Health Policy Plan. 2023, 38, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larchanché, S. Intangible Obstacles: Health Implications of Stigmatization, Structural Violence, and Fear among Undocumented Immigrants in France. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, M.; Aloudat, T.; Bartolomei, J.; Carballo, M.; Durieux-Paillard, S.; Gabus, L.; Jablonka, A.; Jackson, Y.; Kaojaroen, K.; Koch, D.; et al. Migrant and Refugee Populations: A Public Health and Policy Perspective on a Continuing Global Crisis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, I.; Aldridge, R.W.; Devakumar, D.; Orcutt, M.; Burns, R.; Barreto, M.L.; Dhavan, P.; Fouad, F.M.; Groce, N.; Guo, Y.; et al. The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: The Health of a World on the Move. The Lancet 2018, 392, 2606–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, H.; Holmes, S.M.; Madrigal, D.S.; Young, M.-E.D.; Beyeler, N.; Quesada, J. Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, H.; Holmes, S.M.; Madrigal, D.S.; Young, M.-E.D.; Beyeler, N.; Quesada, J. Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Basten, A.; Frattini, C. Migration: A Social Determinant of Migrants’ Health. Migr. Health Eur. Union 2010, 16, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ingleby, D. Ethnicity, Migration and the ‘Social Determinants of Health’ Agenda*. Psychosoc. Interv. 2012, 21, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.K.; Liu, H.; Liang, L.; Ho, J.; Kim, H.; Seong, E.; Bonanno, G.A.; Hobfoll, S.E.; Hall, B.J. Everyday Life Experiences and Mental Health among Conflict-Affected Forced Migrants: A Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Mental Health of Refugees and Migrants: Risk and Protective Factors and Access to Care. ; Global Evidence Review on Health and Migration (GEHM) series; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Elshahat, S.; Moffat, T.; Newbold, K.B. Understanding the Healthy Immigrant Effect in the Context of Mental Health Challenges: A Systematic Critical Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 1564–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, C.; Ali, S.; Roberts, B.; Stewart, R. A Systematic Review of Resilience and Mental Health Outcomes of Conflict-Driven Adult Forced Migrants’. Confl. Health 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaramoorthy, T.; Carney, M.A. Immigration, Mental Health and Psychosocial Well-Being. Med. Anthropol. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.S.Y.; Liddell, B.J.; Nickerson, A. The Relationship Between Post-Migration Stress and Psychological Disorders in Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Suhaiban, H.; Grasser, L.R.; Javanbakht, A. Mental Health of Refugees and Torture Survivors: A Critical Review of Prevalence, Predictors, and Integrated Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IOM. Migrants’ Right to Health – Legal and Policy Instruments Related to Migrants’ Access to Health Care, Social Protection and Labour in Selected East African Countries; International Organization for Migration: Geneva, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vearey, J. Migration and Health in the WHO-AFRO Region: A Scoping Review’; ACMS, WITS University & World Health Organization: Johannesburg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lokotola, C.L.; Mash, R.; Sethlare, V.; Shabani, J.; Temitope, I.; Baldwin-Ragaven, L. Migration and Primary Healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2024, 16, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutiso, V.; Warsame, A.H.; Bosire, E.; Musyimi, C.; Musau, A.; Isse, M.M.; Ndetei, D.M. Intrigues of Accessing Mental Health Services Among Urban Refugees Living in Kenya: The Case of Somali Refugees Living in Eastleigh, Nairobi. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2019, 17, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Pearson, R.J.; McAlpine, A.; Bacchus, L.J.; Spangaro, J.; Muthuri, S.; Muuo, S.; Franchi, G.; Hess, T.; Bangha, M.; et al. Gender-Based Violence and Its Association with Mental Health among Somali Women in a Kenyan Refugee Camp: A Latent Class Analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Ferguson, A.B.; Warsame, A.H.; Isse, M.M. Mental Health Risks and Stressors Faced by Urban Refugees: Perceived Impacts of War and Community Adversities among Somali Refugees in Nairobi. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Swan, L.E.; Warsame, A.H.; Isse, M.M. Risk and Protective Factors for Comorbidity of PTSD, Depression, and Anxiety among Somali Refugees in Kenya. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 0020764020978685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Ferguson, A.; Hunter, M. Cultural Translation of Refugee Trauma: Cultural Idioms of Distress among Somali Refugees in Displacement. Transcult. Psychiatry 2017, 54, 626–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JINNAH, Z. Cultural Causations and Expressions of Distress: A Case Study of Buufis Amongst Somalis in Johannesburg. Urban Forum 2017, 28, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Amobi, A.; Tewolde, S.; Deyessa, N.; Scott, J. Displacement-Related Factors Influencing Marital Practices and Associated Intimate Partner Violence Risk among Somali Refugees in Dollo Ado, Ethiopia: A Qualitative Study. Confl. Health 2020, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, L.E.T.; Im, H. Risk and Protective Factors for Common Mental Disorders among Urban Somali Refugee Youth. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) A Route-Based Approach: Strengthening Protection and Solutions in the Context of Mixed Movements of Refugees and Migrants; 2024.

- Mobilizing Global Knowledge: Refugee Research in an Age of Displacement; Mcgrath, S., Young, J.E.E., Eds.; 1st ed.; University of Calgary Press, 2019; ISBN 978-1-77385-087-0.

- United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); United Nations: New York, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Agudelo, E.; Kim, H.-Y.; Musuka, G.N.; Mukandavire, Z.; Akullian, A.; Cuadros, D.F. Associated Health and Social Determinants of Mobile Populations across HIV Epidemic Gradients in Southern Africa. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vearey, J Legislation, Policy and Frameworks Relating to Migration and Health in South Africa. April 2025.; Governing migration & health in Africa: review series; African Centre for Migration & Society (ACMS), University of the Witwatersrand: Johannebsurg, 2025.

- IOM; ACMS, Wits. Migrants Rights to Health. A Legislative and Policy Review for Southern Africa; IOM and the African Centre for Migration and Society, WITS University: Pretoria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sonke Gender Justice Gender, Migration and Health in SADC: A Focus on Women and Girls; Sonke Gender Justice: Johannesburg, 2019;

- African Union African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention) | African Union 2009.

- UNHCR 2009 Kampala Convention on IDPs 2019.

- Somalia Country Profile. Available online: https://mighealth-policy-africa.org/country-profile-somalia/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (DRC). Gov. Migr. Health Afr. 2023.

- KENYA. Gov. Migr. Health Afr. 2023.

- SOUTH AFRICA. Gov. Migr. Health Afr. 2023.

- Walker, R.; Vearey, J. “Let’s Manage the Stressor Today” Exploring the Mental Health Response to Forced Migrants in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gruchy, T.; Vearey, J.; Datta, K.; Chase, E.; Musariri, L. The “covidisation” of Migration and Health Research: Understanding the Implications of the Pandemic for the Field. In Research Handbook on Migration, Gender, and COVID-19; McAuliffe, M., Bauloz, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2024; pp. 34–47 ISBN 978-1-80220-867-2.

- de Gruchy, T.; Vearey, J.; Datta, K.; Chase, E.; Musariri, L.; Tummers, H. ‘Great Leveler’? Covid-19’s Impact on Migration and Health Research. the Polyphony 2021.

- Walker, R.; Vearey, J. Behind the Masks: Mental Health, Marginalisation and COVID-19’, The Polyphony 2021.

- Walker, R.; Vearey, J. “Let’s Manage the Stressor Today” Exploring the Mental Health Response to Forced Migrants in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2023, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maple, N.; Walker, R.; Vearey, J. Covid-19 and Migration Governance in Africa; Researching Migration & Coronavirus in Southern Africa (MiCoSA): Occasional Paper; African Centre for Migration & Society, University of the Witwatersrand: Johannebsurg, 2021.

- Vearey, J.; de Gruchy, T.; Maple, N. Global Health (Security), Immigration Governance and Covid-19 in South(Ern) Africa: An Evolving Research Agenda. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Maple, N.; Vearey, J. Migrants & the Covid-19 Vaccine Roll-Out in Africa: Hesitancy & Exclusion; African Centre for Migration & Society, University of the Witwatersrand: Johannesburg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vearey, J. Global and Regional Governance Frameworks Shaping Responses to Migration, Displacement and Health in the African Union and the Eastern and Southern African Regions. April 2025 2025.

- The Government of the Republic of South Africa The National Health Insurance Act 20 of 2023 2023.

- SALC SALC Submissions on the South African National Health Insurance Bill (NHI). Available online: https://www.southernafricalitigationcentre.org/2019/11/28/salc-submissions-on-the-south-african-national-health-insurance-bill-nhi/ (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Government of the Republic of Kenya The Refugee Act 2021. No. 1o If 21 2021.

- Ministry of Public Health National Health Development Plan 2019-2022: Towards Universal Health Coverage 2019.

- Ministry of Public Health Strategy for Strengthening the System of Health 2006.

- Boeyink, C.; Ali-Salad, M.A.; Baruti, E.W.; Bile, A.S.; Falisse, J.-B.; Kazamwali, L.M.; Mohamoud, S.A.; Muganza, H.N.; Mukwege, D.M.; Mahmud, A.J. Pathways to Care: IDPs Seeking Health Support and Justice for Sexual and Gender-Based Violence through Social Connections in Garowe and Kismayo, Somalia and South Kivu, DRC. J. Migr. Health 2022, 6, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutombo, P.B.W.B.; Lobukulu, G.L.; Walker, R. Mental Healthcare among Displaced Congolese: Policy and Stakeholders’ Analysis. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2024, 5, 1273937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration (IOM) The DRC: Internal Displacement Overview 2024. Available online: https://drcongo.iom.int/en/news/internal-displacement-overview-2024-published (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Federal Republic of Somalia Essential Package of Health Services (EPHS), Somalia, 2020 2020.

- Federal Republic of Somalia Somali Roadmap Towards Universal Health Coverage (2019-2023) 2018.

- National Department of Health The National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2023-2028 2023.

- The Republic of South Africa The Republic of South Africa National Health Act No. 61 of 2003 2003.

- UHC2030 Action on Health Systems, for Universal Health Coverage and Health Security A UHC2030 Strategic Narrative to Guide Advocacy and Action; 2022.

- Ridde, V.; Ramel, P. The Migrant Crisis and Health Systems: Hygeia Instead of Panacea. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C. From “Invisible Problem” to Global Priority: The Inclusion of Mental Health in the Sustainable Development Goals. Dev. Change 2018, 49, 843–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN United Nations Population Fund Country Programme Document for Democratic Republic of the Congo. DP/FPA/CPD/COD/6; Executive Board of the United Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Population Fund and the United Nations Office for Project Services: New York, 2024;

- Mukala Mayoyo, E.; Chenge, F.; Sow, A.; Criel, B.; Michielsen, J.; Van den Broeck, K.; Coppieters, Y. Health System Facilitators and Barriers to the Integration of Mental Health Services into Primary Care in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A Multimethod Study. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOMALIA. Gov. Migr. Health Afr. 2023.

- Ministry of Health, Kenya Kenya Mental Health Policy 2015 - 2030 2015.

- Ministry of Health, Kenya Mental Health Act 2012 2012.

- Nwoke, C.C.; Cochrane, L. Systematic Review of Gender and Humanitarian Situations Across Africa. Afr. Spectr. 2022, 57, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Republic of South Africa Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000 (as Amended in 2002, 2003, 2005, 2008) 2000.

- Government of the Republic of Kenya The Kenya Citizenship and Immigration Act, 2011. No. 12 of 2011 2011.

- The Republic of South Africa Refugees Amendment Act No.11 of 2017 2017.

- Republic of South Africa Act No. 2 of 2020: Border Management Act, 2020 2020.

- Department of Home Affairs, Republic of South Africa White Paper On Citizenship, Immigration and Refugee Protection: Towards a Complete Overhaul of the Migration System in South Africa. 2024.

- Walker, R. Migration, Trauma and Wellbeing: Exploring the Impact of Violence within the Healthcare System on Refugee Women in South Africa,. In Mobilities of Wellbeing: Migration, the State and Medical Knowledge; Carolina Academic Press, 2021.

- Castañeda, H.; Holmes, S.M.; Madrigal, D.S.; Young, M.-E.D.; Beyeler, N.; Quesada, J. Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vearey, J.; de Gruchy, T.; Maple, N. Global Health (Security), Immigration Governance and Covid-19 in South(Ern) Africa: An Evolving Research Agenda. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organisation of Migration Rights-Based Approach to Migration Governance; 2024.

- Castañeda, H.; Holmes, S.M.; Madrigal, D.S.; Young, M.-E.D.; Beyeler, N.; Quesada, J. Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The 2030 Agenda “is grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, international human rights treaties, the Millennium Declaration and the 2005 World Summit Outcome. It is informed by other instruments such as the Declaration on the Right to Development.” [1] |

| 2 | In this paper, we apply the following definitions: migrant - “An umbrella term, not defined under international law, reflecting the common lay understanding of a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons. The term includes a number of well-defined legal categories of people, such as migrant workers; persons whose particular types of movements are legally defined, such as smuggled migrants; as well as those whose status or means of movement are not specifically defined under international law, such as international students” [4]; asylum seeker: “someone who intends to seek or is awaiting a decision on their request for international protection. In some countries, it is used as a legal term for a person who has applied for refugee status and has not yet received a final decision on their claim [5]; refugee - a person who "owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of [their] nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail [themself] of the protection of that country" [6]; internally Displaced People (IDP): "persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized border"[7]. |

| 3 | In this paper, we define an undocumented migrant as a foreign-born person who is currently in a country without the valid legal authorisation enter, live or work in that country. |

| 4 | In this paper, SEA refers to: the Southern African Development Community (SADC), East African Community (EAC) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). |

| 5 | DiSoCo involved collaboration between (in alphabetical order): Amref International University (Kenya); ARQ International

(Netherlands); the Kinshasa School of Public Health (DRC); Panzi Foundation (DRC); Queen Margaret University (UK);

Somali Institute for Development and Research (Somalia); Université Evangélique en Afrique (DRC); the University of

Edinburgh (UK); and, the University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa). DiSoCo is a GCRF Protracted

Displacement project that aims to help Somali and Congolese displaced people to access appropriate healthcare for chronic

mental health conditions associated with protracted displacement, conflict, and sexual and gender‐based violence. DiSoCo is

a multi‐sited project focusing on Somali and Congolese Internally Displaced People (IDPs) in Somalia and Eastern DRC

respectively, and Somali and Congolese refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya and South Africa. The DiSoCo team brings

together researchers and practitioners from international development, migration studies, gender studies, medical

anthropology, public health and health policy, and medical sciences to undertake interdisciplinary empirical research in

these protracted displacement contexts. https://displacement.sps.ed.ac.uk/

|

| 6 | The Gendered violence and poor mental health among migrants in precarious situations Global Health Research Group (GEMMS) is supported by the NIHR (grant ref: NIHR134629). GEMMS involves collaboration between (in alphabetical order): Africa University (Zimbabwe); the African Centre for Migration & Society (ACMS), University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa); Health Poverty Action (HPA; Cambodia, Zimbabwe and UK); Oxford University (UK); the Tata Institute for Social Sciences (TISS, India); Towards Sustainable Use of Resources Organization (TSURO) Trust (Zimbabwe); University of Essex (UK); and, the University of Johannesburg (South Africa). https://gemms-research.org/

|

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | “Right to Health” here refers to the right to access healthcare. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).