1. Introduction

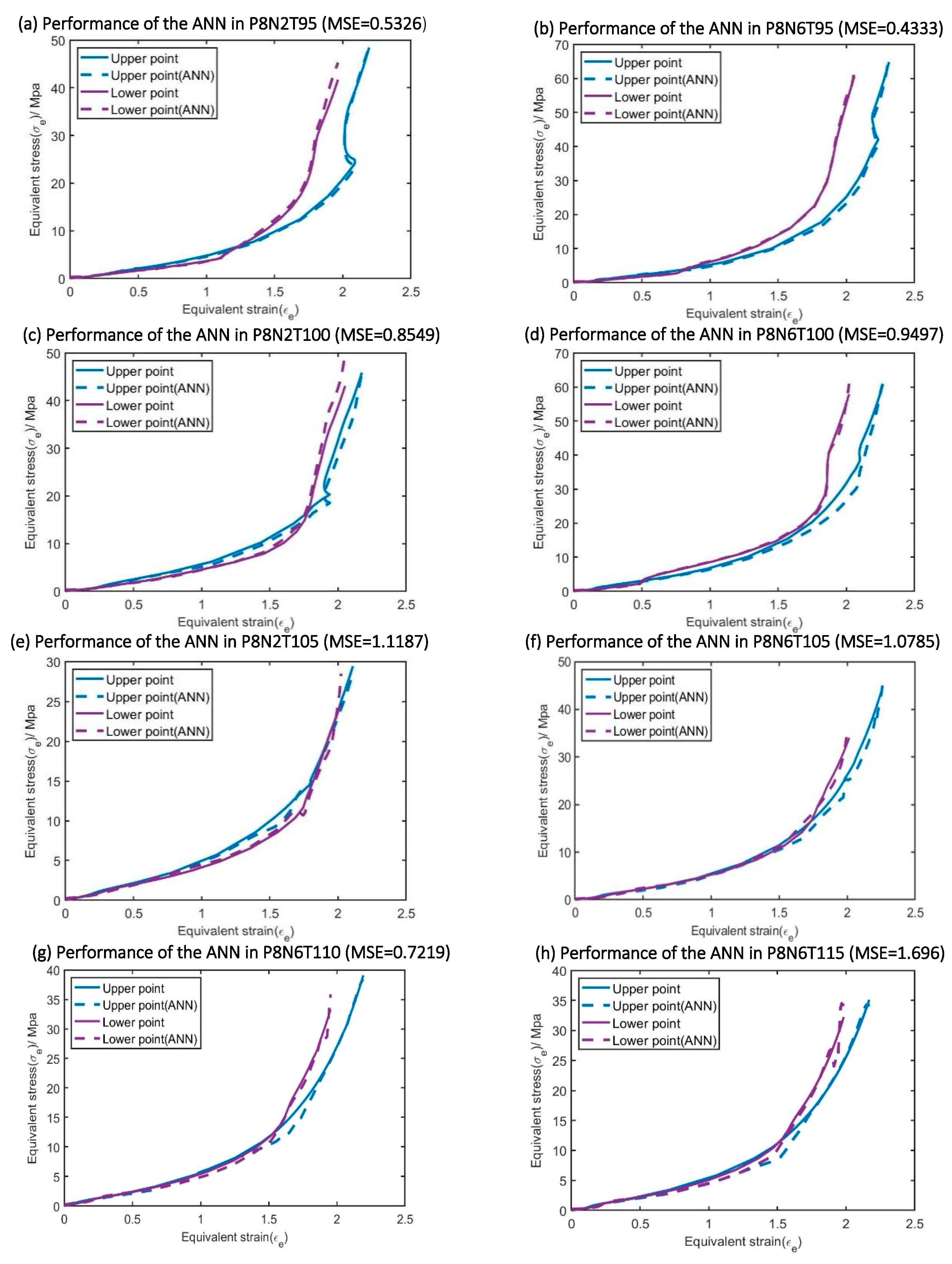

Stretch Blow Moulding (SBM) is the most common method for producing Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) bottles used in the carbonated soft drink (CSD) and water industries. The first step involves creating a preform, which is a test tube-shaped specimen made through injection molding. The preform is then heated above its glass transition temperature and shaped into a mould using both axial stretching through a stretch rod and radial stretching via internal air pressure. The typical evolution of the preform as it is stretched and blown in the mould is shown in

Figure 1.

Manufacturers face a significant challenge in creating containers that utilize minimal material while still meeting the performance demands of in-service use, such as resisting top load, burst, and squeeze forces. Traditionally the optimum preform design and optimum process conditions have been determined by trial and error and knowhow, however the more modern approach involves the use of simulation whereby a finite element model of SBM is used to evaluate preform design and process conditions in advance. One of the key inputs into the SBM simulation is the material model that is required to accurately capture the nonlinear viscoelastic behaviour of PET subjected to high deformation and high strain rates at temperatures above the glass transition temperature (T

g). Previous work by the authors have demonstrated that a model originally developed by Buckley et al. [

1,

2,

3] and with subsequent adjustments [

4,

5,

6] can reasonably well capture this complex behaviour within SBM simulations. However the model has a limitation in the complexity of generating the material parameters which can be time consuming and expensive and it can have difficulty maintaining accuracy across a wide range of temperature and strain rates.

The aim of this paper is to develop an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) based constitutive model to predict the complex behaviour of PET in SBM. In order to do this, we will also present an experimental method for efficiently generating the rich data set required for producing a robust and accurate ANN model (850 strain-stress curves). Each strain-stress curves consists of more than 200 data points so that 253,864 data points can be collected during experiments. The work builds on previous publications [

7,

8] where authors demonstrated the ability of an ANN to predict the behaviour of PET biaxial stretched at different strain rates and temperatures for a simple displacement controlled planar experiment. In this paper we have increased the complexity and capability of the ANN model though the development of a new architecture enabling it to be used in the commercial finite element package Abaqus for complex load-controlled scenarios suitable for modelling the behaviour of PET in SBM.

For decades, researchers have been trying to develop accurate physical based models, which are able to describe the nonlinear viscoelastic behaviour of the PET during the SBM process at temperatures above the glass transition temperature (T

g). A comprehensive review of these approaches has been presented in our previous publication [

7,

8]. In summary, all of these approaches can capture the typical nonlinear temperature stress strain behaviour in specific conditions at different levels of accuracy. However, despite efforts to develop accurate models, weaknesses still exist due to the highly nonlinear deformation behaviour of PET during blow molding, which is affected by various parameters including temperature, deformation mode, stretch ratio, strain history, and strain rate. As pointed out by Menary et al., these parameters have a significant impact on the deformation behaviour of PET [

9]. A shared characteristic among these constitutive models mentioned above is that they limit the depiction of the material's deformation behaviour to predefined parametric constitutive equations. However, fixed equations fail to accurately match the complexity of real conditions, as such physical models have associated inaccuracies. According to Liu et al. [

10], the most obvious novelties of the ANN-based constitutive model is that it is able to build a complex nonlinear relationship in a form-free manner. As a result, the weakness of these models that depend on presumed functions with fixed mathematic expressions can be navigated by utilizing ANN technology.

In addition to the ‘form-free’ advantage mentioned above, the ANN also has other unique advantages compared with conventional physical models. Zhang et al. [

11] demonstrated that a single neural network model was able to describe the behaviour of a material during deformation directly without any other equations, such as yield function, flow rule and hardening law. As a result, in comparison with a physical based model, the complexity of a constitutive model can be greatly reduced, which brings the dual advantage of reduced running time and coding simplicity.

One of the first researchers to propose the concept of an ANN-based constitutive model was Ghaboussi et al. [

12]. They utilized an ANN-based constitutive model to forecast the stress-strain correlation of concrete when subjected to biaxial monotonic loading and uniaxial cyclic loading. Thanks to advancements in computer power, ANN-based constitutive models have undergone rapid development in recent years and have already found widespread use in various materials, such as foam [

13], metals [

14,

15,

16,

17] and polymers [

18,

19,

20].

Settgast et al. [

13] proposed a hybrid ANN based model that embedded neural networks into the established framework of rate-independent plasticity and they demonstrated that this structure was able to simulate the elastic-plastic behaviour of foam efficiently. Settgast et al. [

13] proved the fact that the ANN function can not only be used by itself but also that there were advantages in combining it with an existing traditional physical constitutive model. The cooperation with physical based functions not only reduced the size of training database required by training an ANN but also improved its stability.

Pandya et al. [

14] upgraded Kessler’s model [

21] and proposed a machine-learning based plasticity model which took strain rate and temperature into account. Li et al. [

15,

16] proposed an ANN based plasticity model to capture the large deformation response of the DP780 streel over a large range of strain rates and temperature. This ANN based model not only had higher accuracy and significant speed-up compared with the conventional plasticity model but also features a hardening law. Although Li ‘s previous work was in the metal domain, they demonstrated the feasibility of replacing conventional physical constitutive models by ANNs.

Diamantopoulou et al. [

18] trained an ANN to describe the relationship among the process parameters, the degree of polymerization and the nonlinear stress-strain response of a polymer structure obtained from experiments. They highlighted the robustness of the developed ANN model and its advantage of reducing the complexity of the constitutive law. The hybrid modelling approach proposed by Jordan et al. [

19] is taken by combing mechanism-based and databased model. However, their attention is limited to the stress-strain response for only uniaxial experiments and their temperature and strain rate range are relatively small (20℃ - 80 ℃ and 10

-3/s -10

-1/s) compared to the strain rates and temperature range required for modelling PET in SBM (1/s – 100/s and 85℃-115℃). Jang et al. [

20] proposed a different combination method between FEA and ANN in that the ANN was only used to replace the nonlinear iterations in the stress return mapping method within a UMAT user subroutine [

22].

The novelty of the current work can be summarised into two points. Firstly, an important point to note is that most of the ANN models discussed have been validated for displacement-controlled scenarios i.e. the boundary conditions for displacement are imposed on the model and the resulting force is calculated. We addressed this problem in our previous works [

7,

8] where we demonstrated the ability of the ANN to capture the nonlinear viscoelastic behaviour of PET for displacement controlled biaxial tests. However, to be used in a complex manufacturing simulation such as SBM, it is also important to validate the model in a load-controlled scenario i.e. a load is applied and the corresponding displacement is calculated. This is a more challenging problem since variables such as strain rate, mode of deformation are no longer fixed input parameters but are outputs from the model that vary at each time increment. In order to deal with this difficulty, a hybrid constitutive model combining advantages from both conventional physical based model and an ANN based model is proposed in the current work. The ANN part in the hybrid constitutive model adopts an innovative architecture specifically designed for load-controlled scenarios.

Another novelty of the current work is the acquisition system of experimental data. Generally, the experimental data required to train an ANN is acquired from standard specimens with simple graphs, for example, Jordan et al. [

19] utilized dog-bone specimens and Li et al. [

15] used flat smooth specimens with quasi-static strain rates. However, as highlighted by Menary et al. [

9], the SBM process is a complex manufacturing process influenced by many dynamic parameters. As a result, in order to obtain an accurate enough ANN model, experimental data was collected from free stretch blow (FSB) experiments directly which are able to imitate real process parameters. All experimental data shown in the current work are published for the first time.

The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the experimental procedure for generating the rich experimental data set necessary for training the ANN model. The component of the conventional physical based model used is described in

Section 3 whilst

Section 4 is utilized to introduce the detailed architecture of the hybrid ANN constitutive model. Subsequently, the hybrid ANN based model is trained in

Section 5. Finally, in

Section 6 the hybrid model is implemented in the finite element package Abaqus to simulate the behaviour of PET in a SBM simulation with the results validated against experimental data.

3. Brief Description of Buckley Model

Menary et al. [

26] compared several physical based models, including a hyperelastic model, a creep model and the Buckley model, to ascertain their suitability for modelling stretch blow molding. The model proposed by Buckley et al. [

1,

2,

3] was found to provide the simulation results that match best with the experimental data. After Menary’s work, the model has evolved to capture key features of the behaviour of PET including how the onset of strain hardening changed as a function of temperature and strain rate [

4,

5,

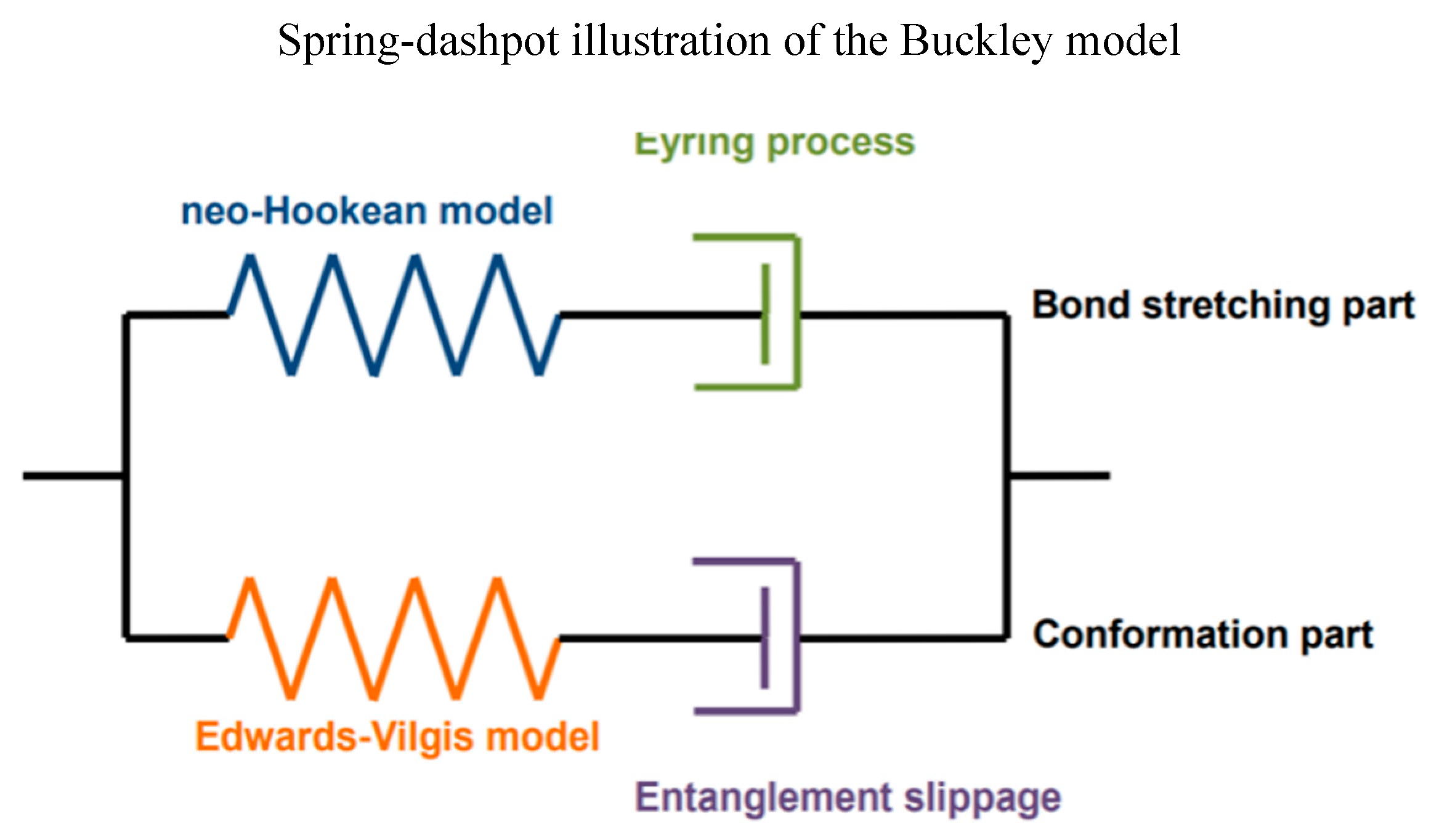

27]. A 1D representation of the Buckley is shown in

Figure 10 which shows a parallel circuit with two arms, named the bond stretching part and the conformation part respectively.

The bond-stretch arm represents the bond deformation of the polymer, exhibiting the instantaneous stress from the interactions of the molecular bonds and is important for predicting the onset of yield and how it varies with temperature and strain rate. In the conformational arm, it represents the perturbation of the polymers conformation and is determined by the change in an entropic free energy function. The conformation part captures the large strain behaviour post yield including strain softening and strain hardening and how these change as a function of temperature, strain rate and mode of deformation.

The Buckley model can be expressed by Equ(1),

where

is the principal bond-stretching stress and

is the principal conformation stress.

3.1. Bond Stretching Part

The principal deviatoric stress of the bond-stretching component (

) is expressed by Equ (2),

where

is the contribution to shear modulus arising from bond stretching,

is the relaxation time and

is the deviatoric true strain. In the present work,

is set as 600MPa [

1]. In order to obtain

, three equations are utilized, including Eyring formulation [

28], Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher function [

29,

30] and Arrhenius equation [

31].

According to Li & Buckley [

32], an implicit method or identified integral solution for Equ (2) can cause potential numerical difficulty in modelling large and post-yield deformations. In order to solve this problem, an explicit method was proposed to solve

from Equ (2) , as shown in Equ (3) and Equ (4), which have been subsequently used in the VUmat subroutine developed in the current work.

is the time increment,

is the spin tensor and

is the stress increment in this time increment.

is obtained from Equ(4).

3.2. Conformation Part

In the conformational part, the stress component (

) is represented by the crosslinks-sliplinks model proposed by Edwards and Vilgis [

33]. The principle conformational stresses (

) are expressed by Equ (5),

where

is the hydrostatic stress,

is the determinant of the deformation gradient tensor,

is the principal stretch and

is obtained from the free energy function which was derived by Edwards and Vilgis [

33] as shown in Equ (6),

where

is the entanglement density,

is the Boltzmann’s constant,

is the absolute temperature,

is the looseness parameter of the entanglement,

are the principal network stretch, and

is a measurement of the inextensibility of the entanglement network where the maximum extension is determined by

.

Adams et al. [

3] updated Equ (5) by considering the entanglement slippage in the conformational part to capture the strain hardening behaviour more accurately. As a result, the total stretch (

) in Equ (5) is replaced by the slippage stretch (

), which can be obtained by Equ (7),

where

are the deviatoric stresses of the conformational part and

is the slippage viscosity as shown in Equ (8),

where

is the maximum principal network stress,

is the critical value of network stretch and

is the initial viscosity.

Yan [

4] modified Equ (8) by changing

from a constant to a function with respect to temperature and strain rate, as shown in Equ (9),

where

is the shifted temperature obtained by Equ (10),

where

is the shift factor which is the ratio between the shifted temperature and the reference temperature,

is the strain rate and

is an indicator of deformation mode.

7. Discussion

A hybrid ANN based constitutive model has been successfully implemented in a free stretch blow simulation and validated against experimental data. Whilst the results vs experiments is impressive, there is still potential to explore the limits of the model beyond that described in this paper to verify the robustness of the model. The validation in the free stretch blow for example could be expanded to include experiments using preforms of the same material but with different geometries and different process conditions. In addition, experiments using more extreme conditions could present a challenge to the model with its current architecture. It has been reported in the literature about the influence of sequential mode of deformation i.e. a strain history involving a significant stretch in one direction followed by a subsequent stretch in the other direction is able to influence the evolution of the microstructure and the resulting stress strain behaviour. With the current approach of taking strain history into account, it is unlikely that the model will be able to capture the significant changes in the stress strain behaviour produced by this mode of deformation. Whilst the strain history is a good starting point for capturing strain history, it is likely a more complex function that takes account of the memory of the polymer and the strain path experienced to arrive at the current state will be required.

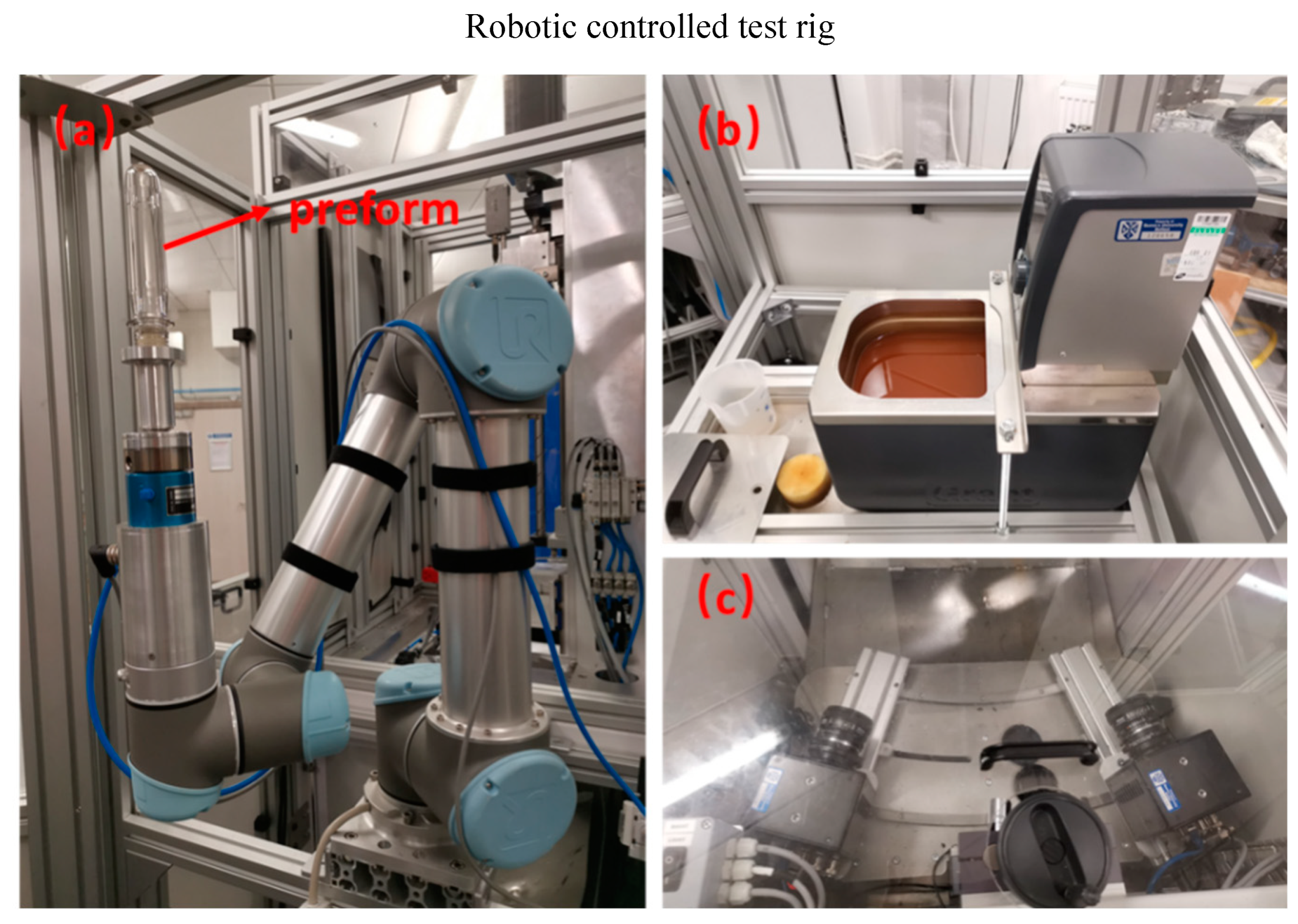

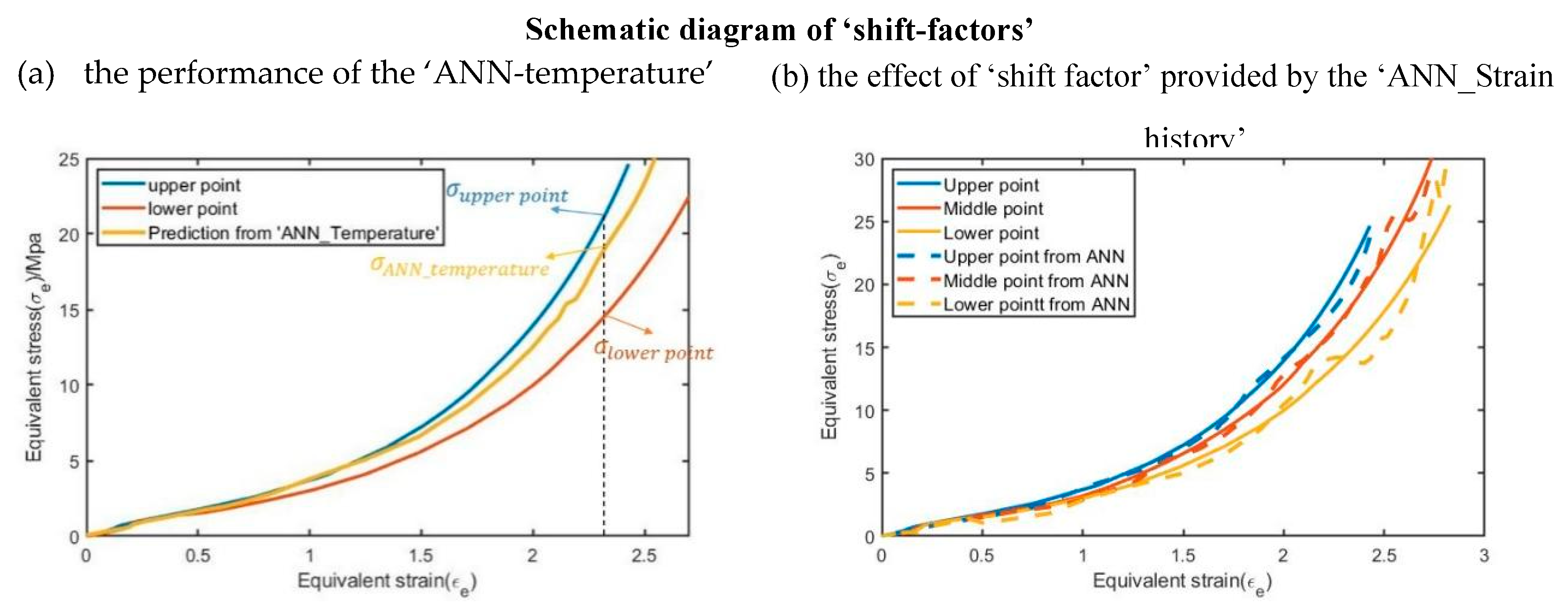

The prediction from the ANN whilst good still has some limitations, for example in

Figure 19 it can be seen that the prediction for the lower point on the preform displays a fluctuation in the stress strain curve rather than a smooth monotonic stress strain curve observed experimentally. This is likely a result of the over fitting phenomenon that can be typically found when training ANNs. Although lots of methods have already adopted to decrease the level of oscillations on the ‘ANN_Temperature’ and the ‘ANN_Strain history separately, for example, the ’ANN_Strain history’ has already been designed as a kind of dynamic model, the oscillation level of the output of the ANN based constitutive model is still slightly larger than the corresponding oscillation level in a single ANN due to the relationship between the outputs of these two ANNs (they need to be multiplied by each other). It is unclear at present what influence this will have on the free stretch blow simulations but it can likely be minimized through further optimization.

Despite the limitations described above, the experimental approach combined with the hybrid ANN based constitutive model offers several advantages over the traditional testing methods and physical based constitutive modelling approach. These includes the ability to automatically produce a fitted material model for any material that can be stretch blow moulded much more efficiently (days vs weeks). This advantage is particularly important for the stretch blow moulding process given the huge interest in replacing petroleum based polymers such as PET with bio based materials such as Polyethylene Furanoate (PEF) and Polyhydroxyalkanoates(PHA). What previously would have taken years to study and test these polymers to build new constitutive laws and establish new processing and design rules to account for their different properties has the potential to be done in weeks with the combination of the semi-automatic test rig, the automated training via the ANN and the stretch blow moulding simulation incorporating the ANN.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Fei Teng; Formal analysis, Fei Teng; Funding acquisition, Gary Menary; Investigation, Fei Teng; Methodology, Fei Teng and Gary Menary; Project administration, Gary Menary; Resources, Gary Menary; Software, Fei Teng; Supervision, Gary Menary and John Stevens; Validation, Fei Teng; Visualization, Fei Teng; Writing – original draft, Fei Teng; Writing – review & editing, Fei Teng, Gary Menary, Shiyong Yan and John Stevens.

Figure 1.

forming stages in the SBM process.

Figure 1.

forming stages in the SBM process.

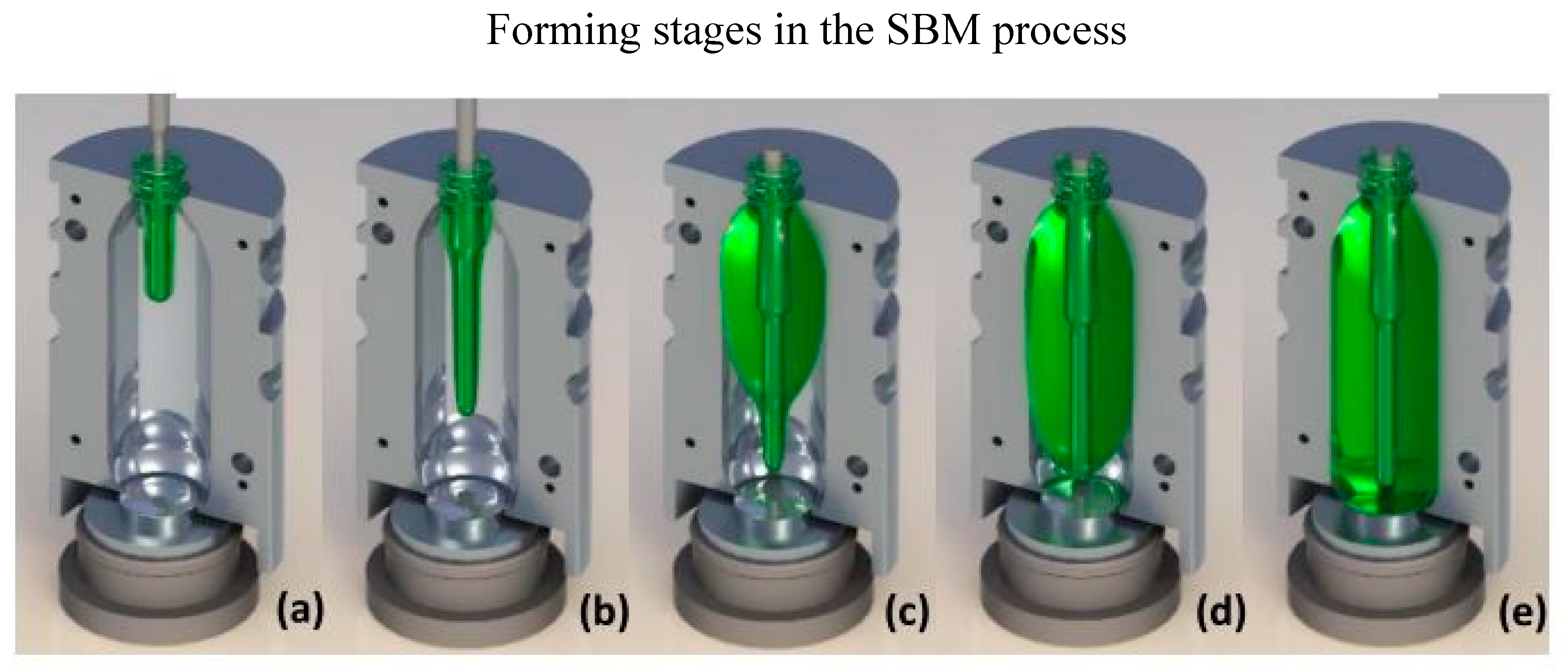

Figure 2.

Dimensions of preform used in experiments.

Figure 2.

Dimensions of preform used in experiments.

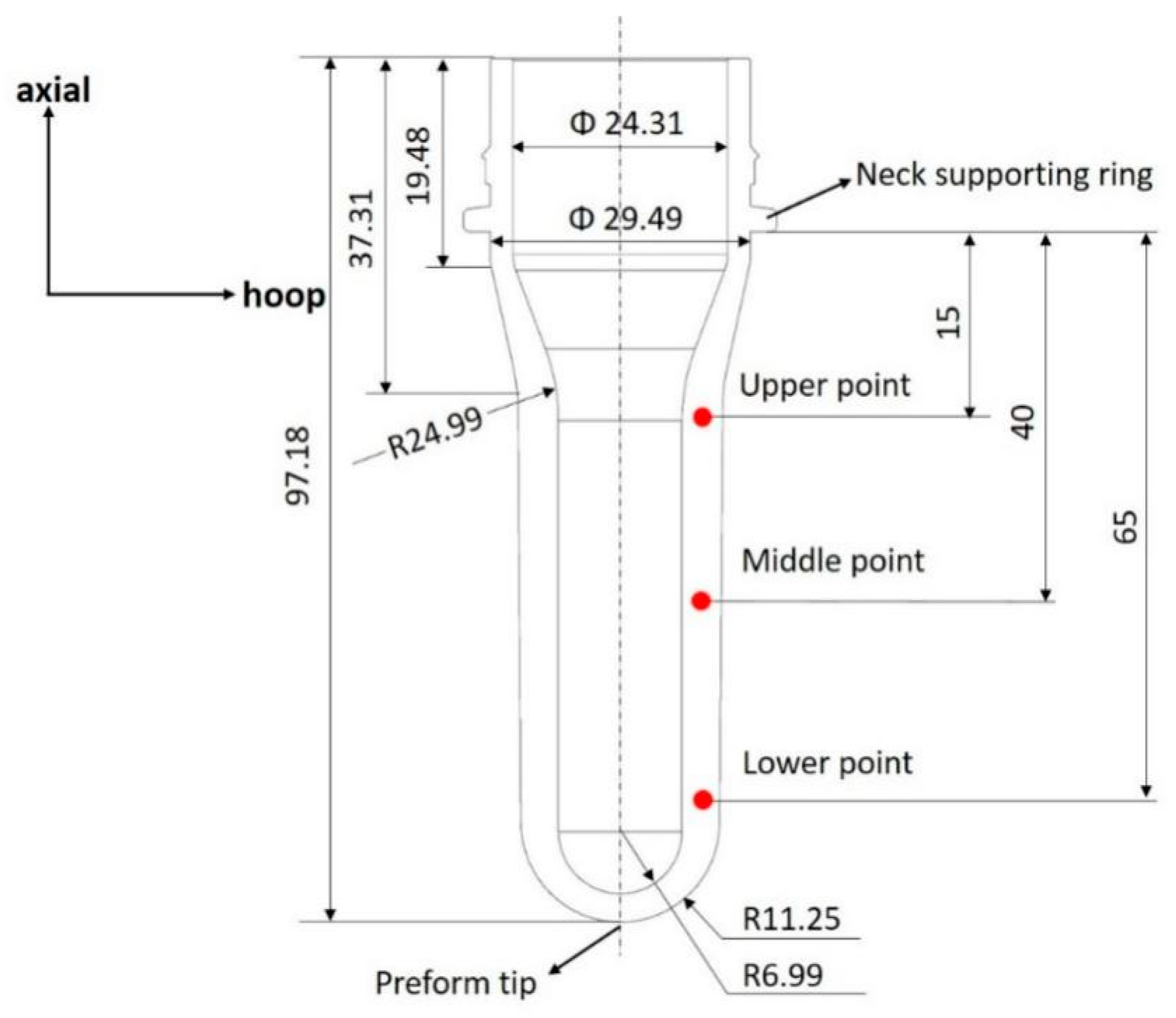

Figure 3.

Robotic controlled test rig, (a) the robotic arm used to hold the specimen;(b) oil bath device; (c) high speed cameras used for monitoring the deformation.

Figure 3.

Robotic controlled test rig, (a) the robotic arm used to hold the specimen;(b) oil bath device; (c) high speed cameras used for monitoring the deformation.

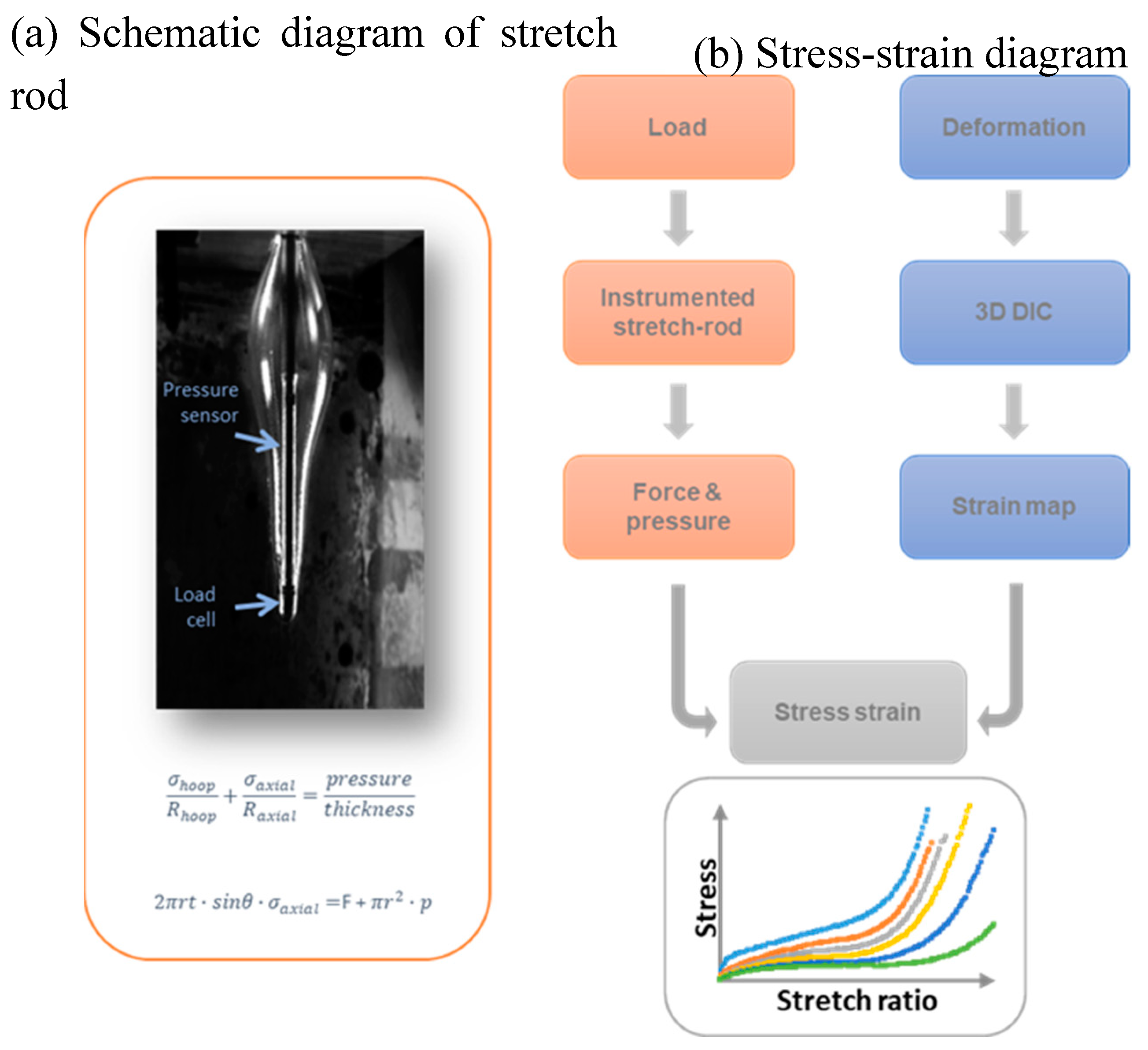

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of demonstrating how stress strain data is captured from Free Stretch Blow experiments.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of demonstrating how stress strain data is captured from Free Stretch Blow experiments.

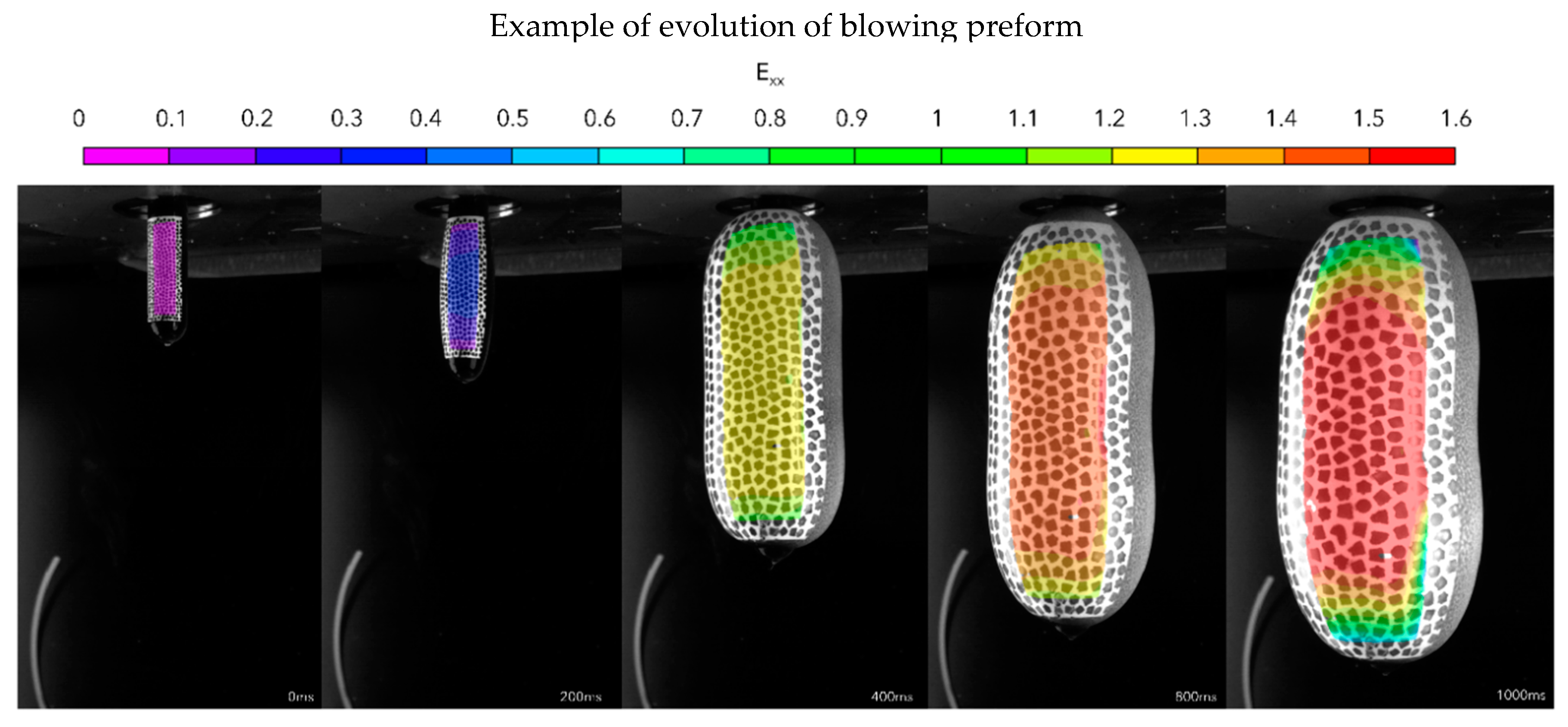

Figure 5.

Example of evolution of blowing preform monitored by high-speed camera with contours of hoop strain as calculated by Digital Image Correlation.

Figure 5.

Example of evolution of blowing preform monitored by high-speed camera with contours of hoop strain as calculated by Digital Image Correlation.

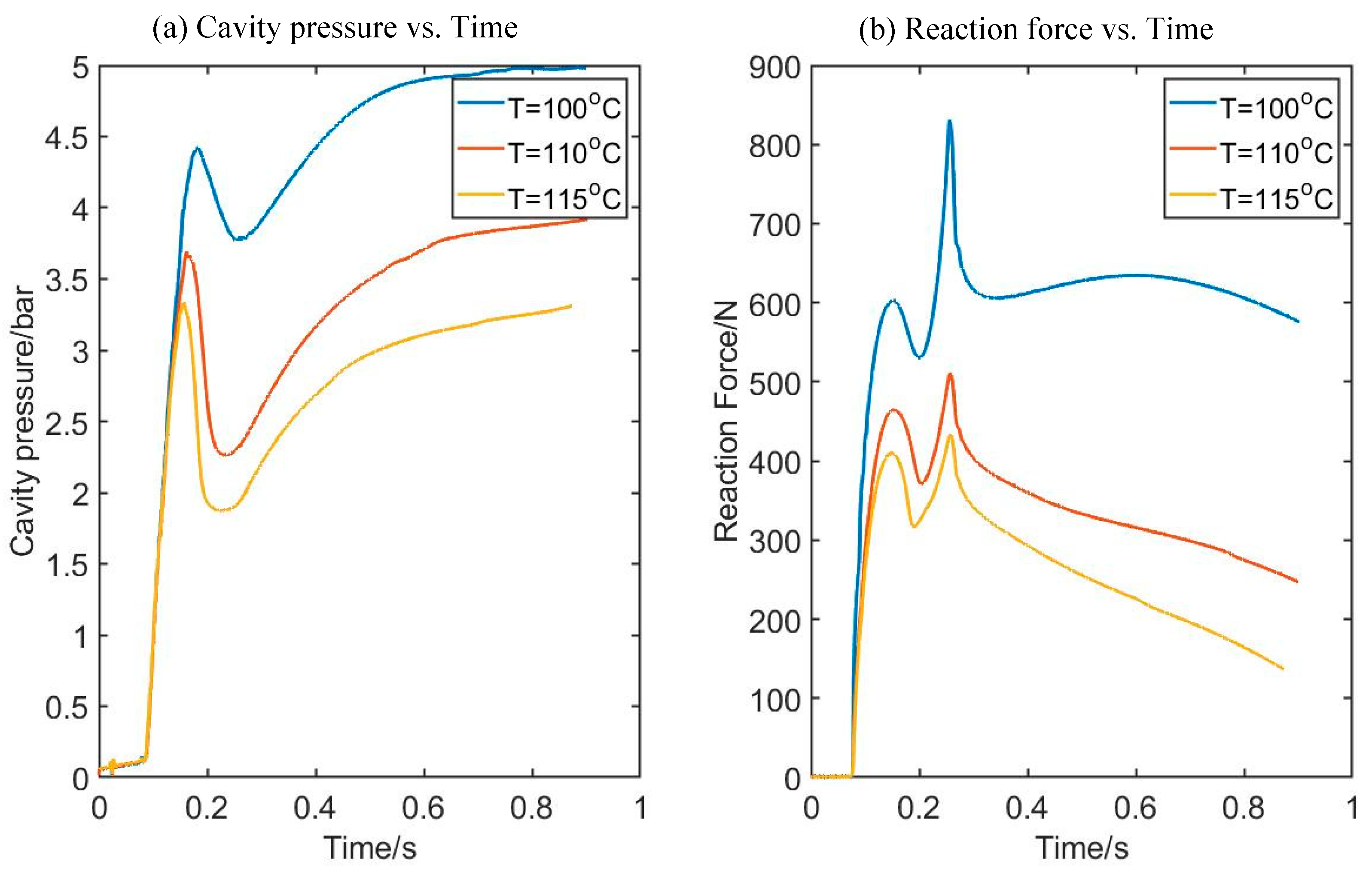

Figure 6.

The evolution of force and pressure of experiment shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

The evolution of force and pressure of experiment shown in

Figure 5.

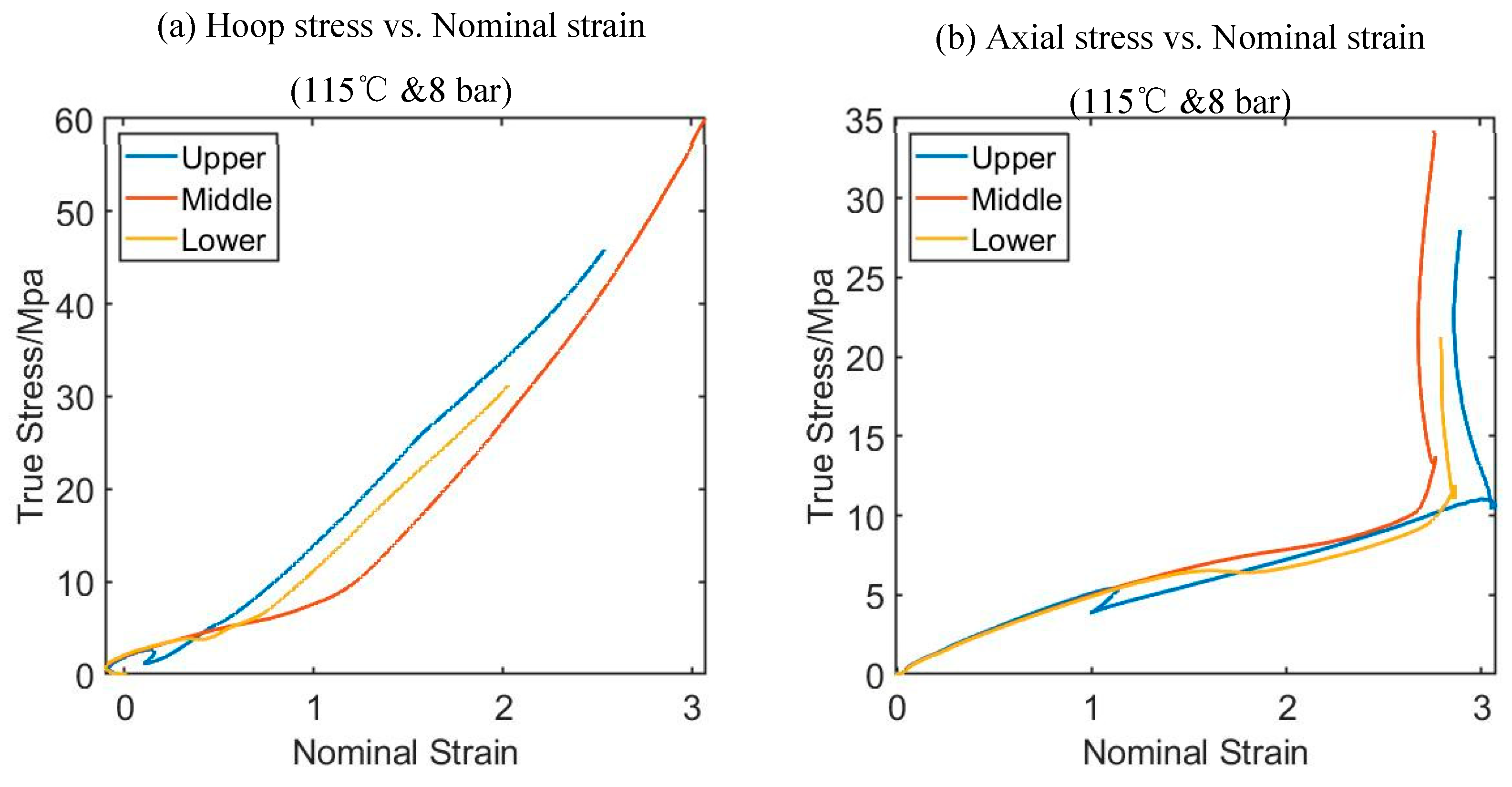

Figure 7.

An example of Hoop Stress Strain curves (a) and Axial Stress strain curves (b) from three positions of the preform (upper, middle, and lower as indicated in

Figure 2).

Figure 7.

An example of Hoop Stress Strain curves (a) and Axial Stress strain curves (b) from three positions of the preform (upper, middle, and lower as indicated in

Figure 2).

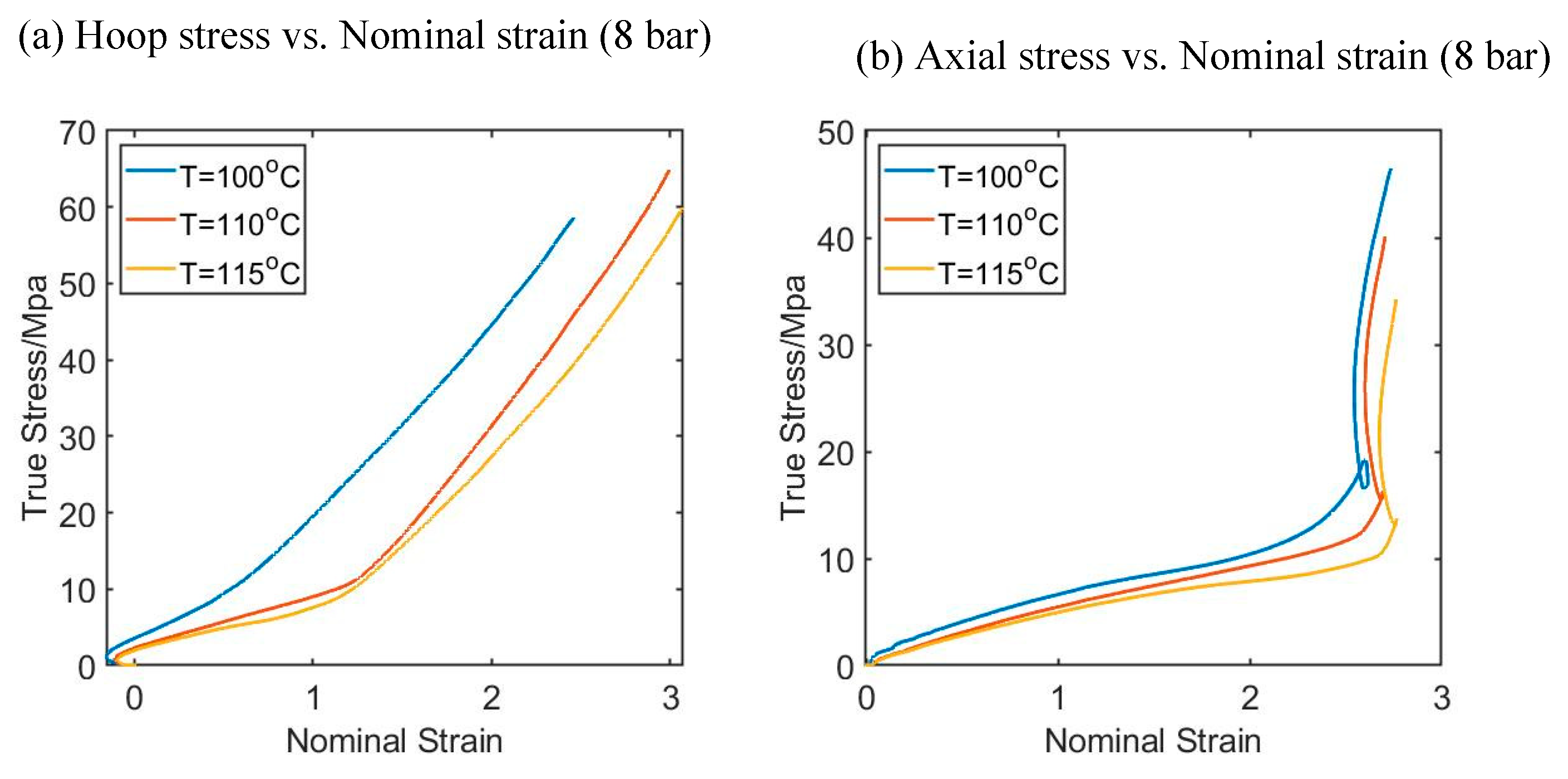

Figure 8.

An example of Hoop Stress Strain curves (a) and Axial Stress strain curves (b) from the midpoint of the preform for three different temperatures.

Figure 8.

An example of Hoop Stress Strain curves (a) and Axial Stress strain curves (b) from the midpoint of the preform for three different temperatures.

Figure 9.

A flow restrictor valve with a rotating knob.

Figure 9.

A flow restrictor valve with a rotating knob.

Figure 10.

Spring-dashpot illustration of the Buckley model.

Figure 10.

Spring-dashpot illustration of the Buckley model.

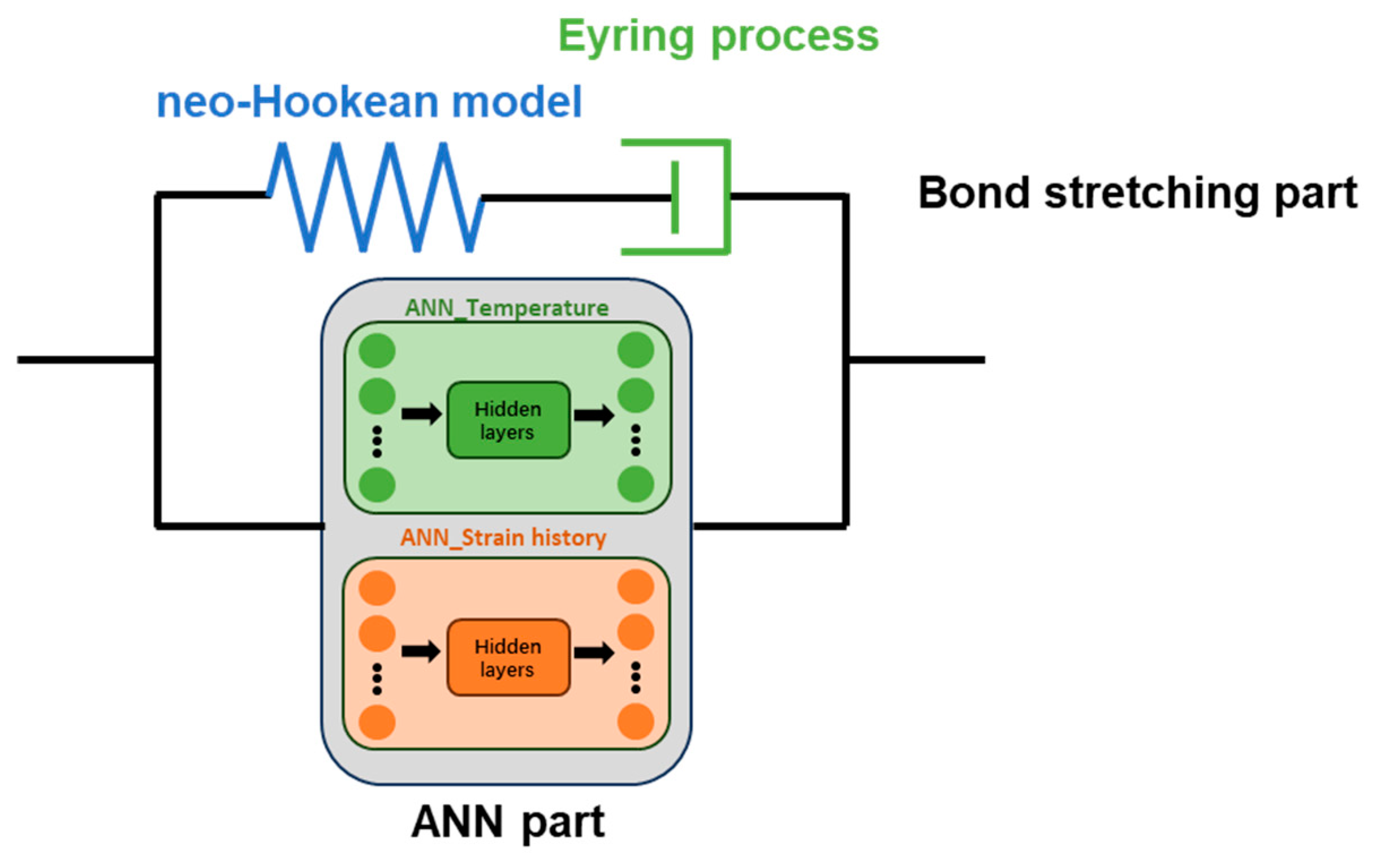

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of hybrid ANN based model.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of hybrid ANN based model.

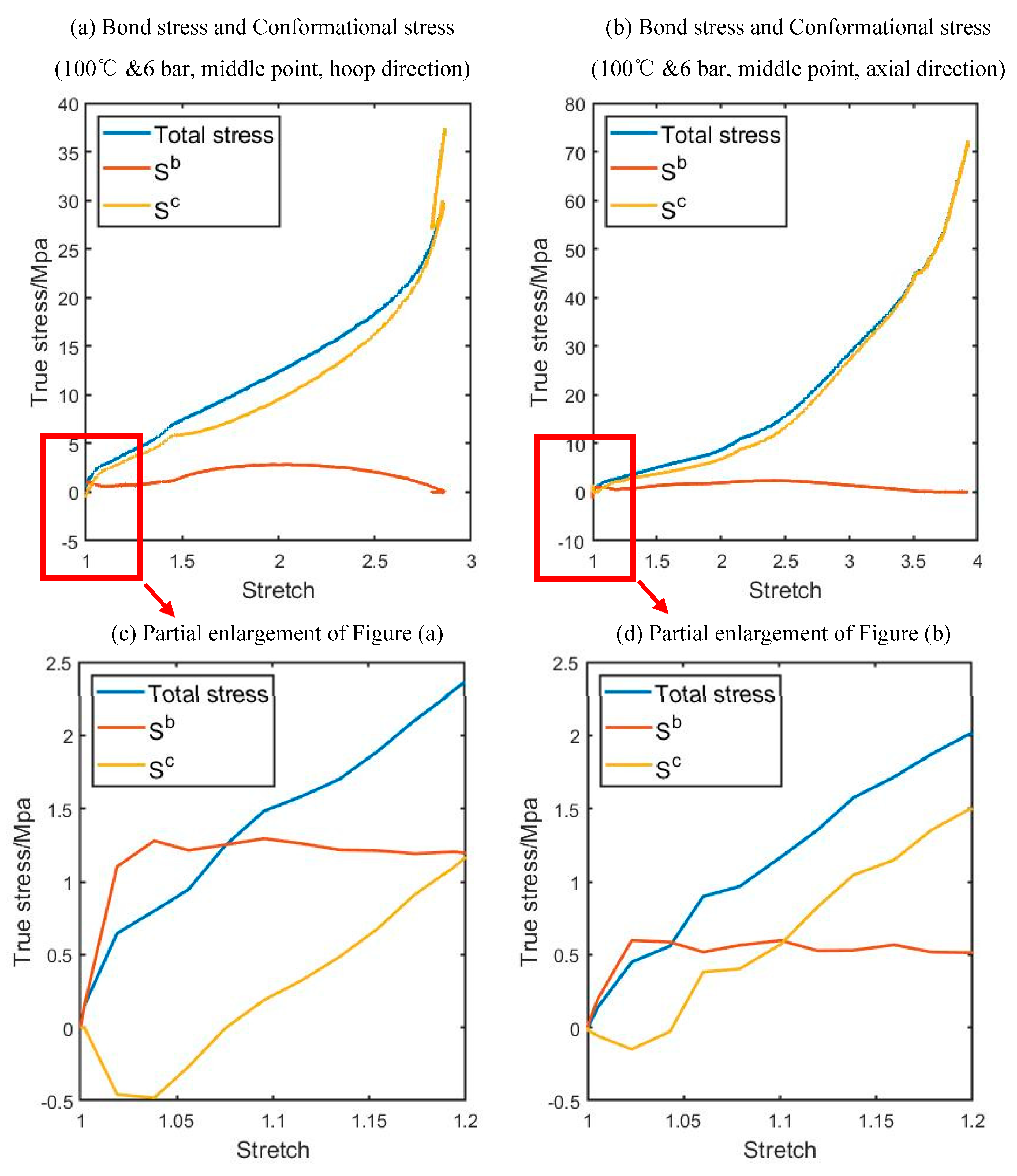

Figure 12.

An example of the relationship between Sb and Sc in both hoop (a) and axial (b) direction and partial enlargement views of (a) and (b). (The position of ‘Middle point’ is indicated in

Figure 2).

Figure 12.

An example of the relationship between Sb and Sc in both hoop (a) and axial (b) direction and partial enlargement views of (a) and (b). (The position of ‘Middle point’ is indicated in

Figure 2).

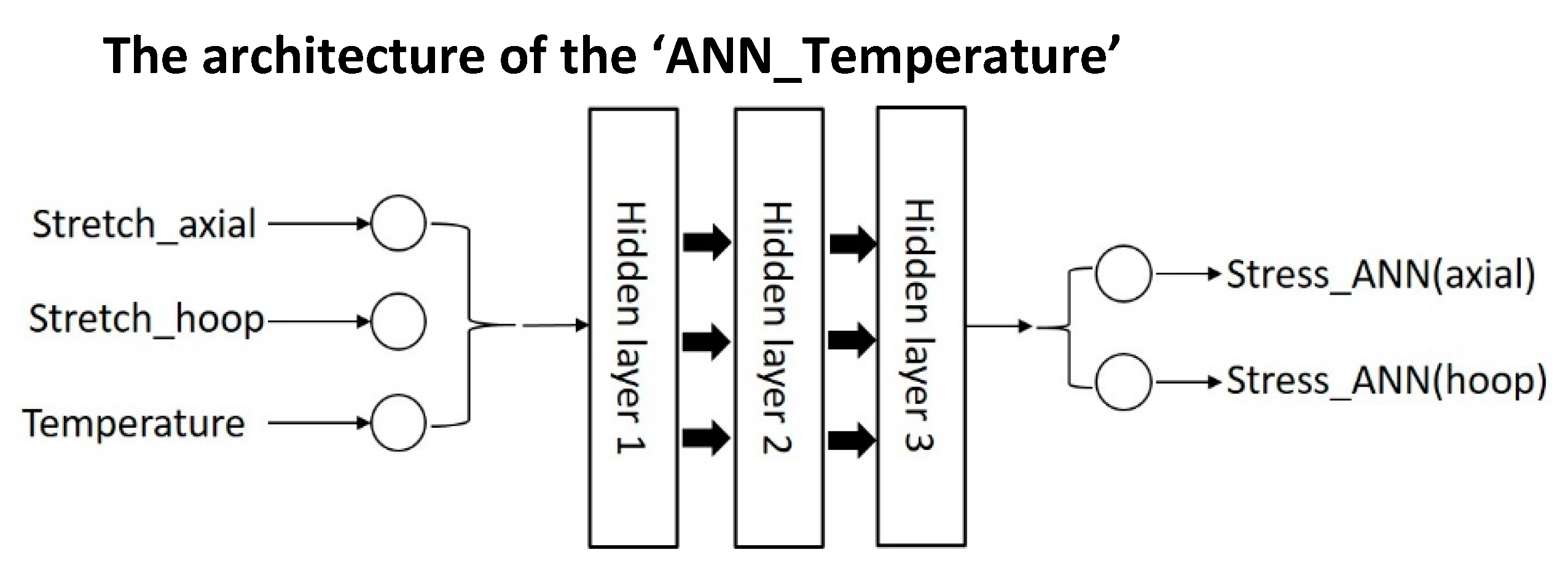

Figure 13.

the architecture of the ‘ANN_Temperature’.

Figure 13.

the architecture of the ‘ANN_Temperature’.

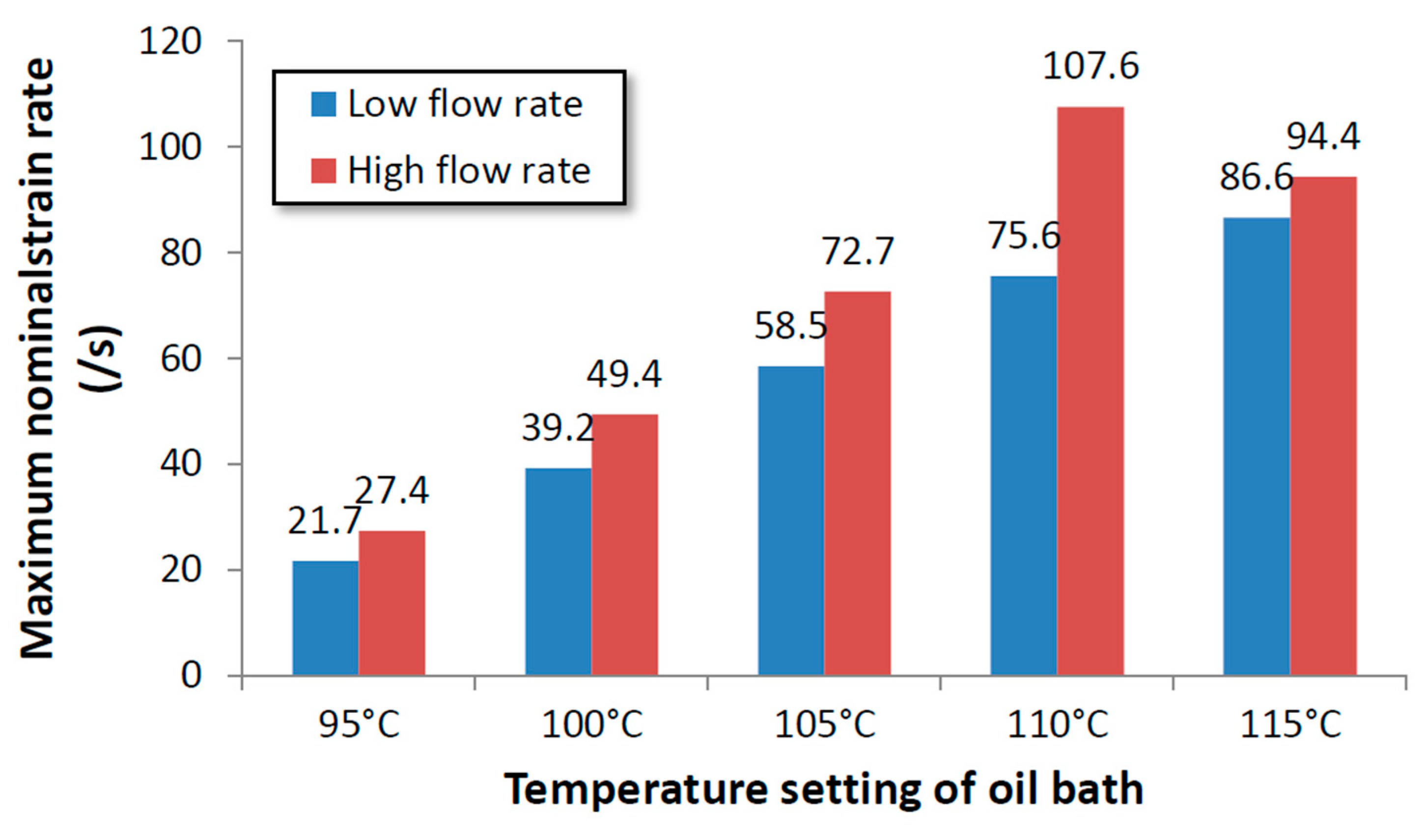

Figure 14.

The effect of mass flow rate and temperature on the maximum strain rate.

Figure 14.

The effect of mass flow rate and temperature on the maximum strain rate.

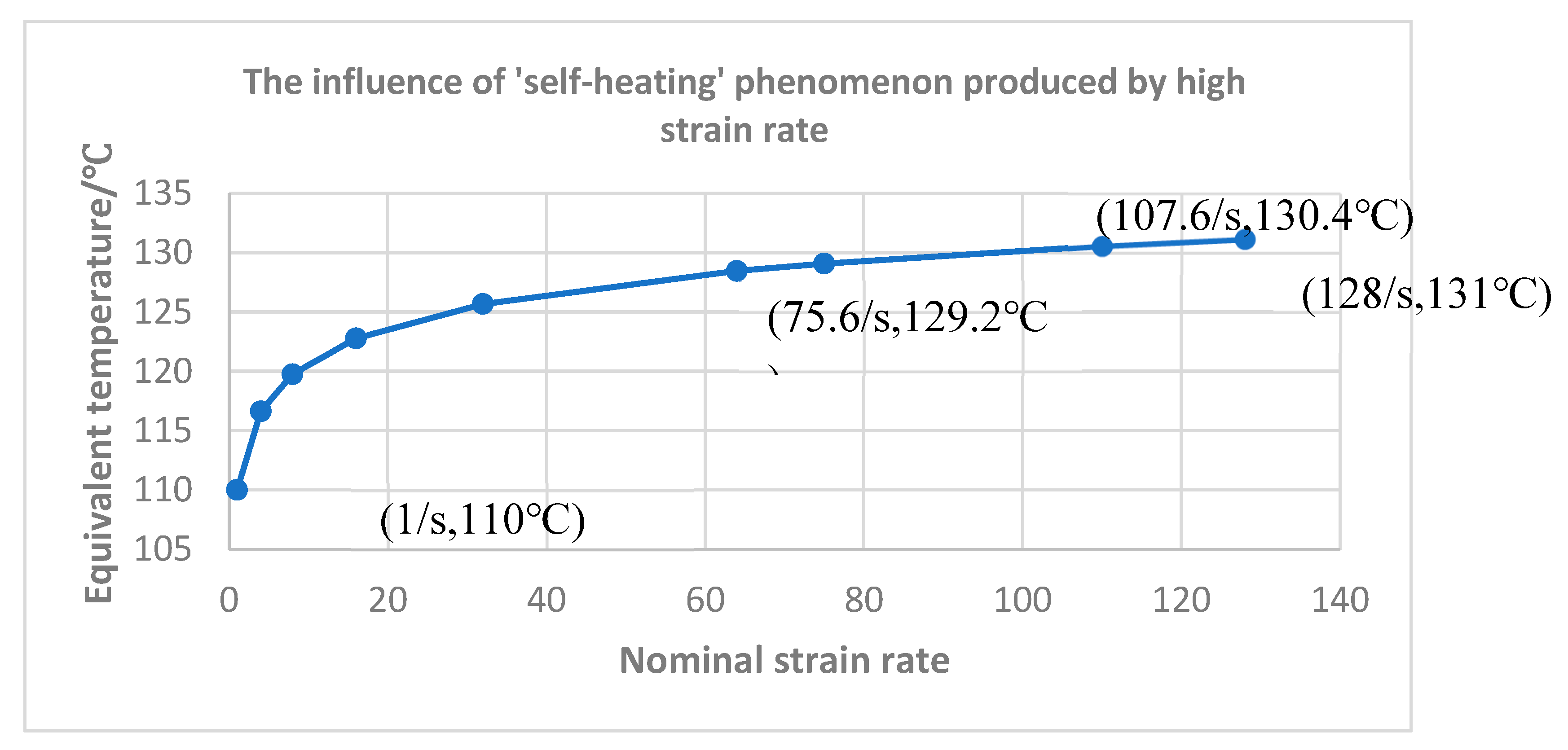

Figure 15.

The temperature increase produced by the high strain rate during SBM process.

Figure 15.

The temperature increase produced by the high strain rate during SBM process.

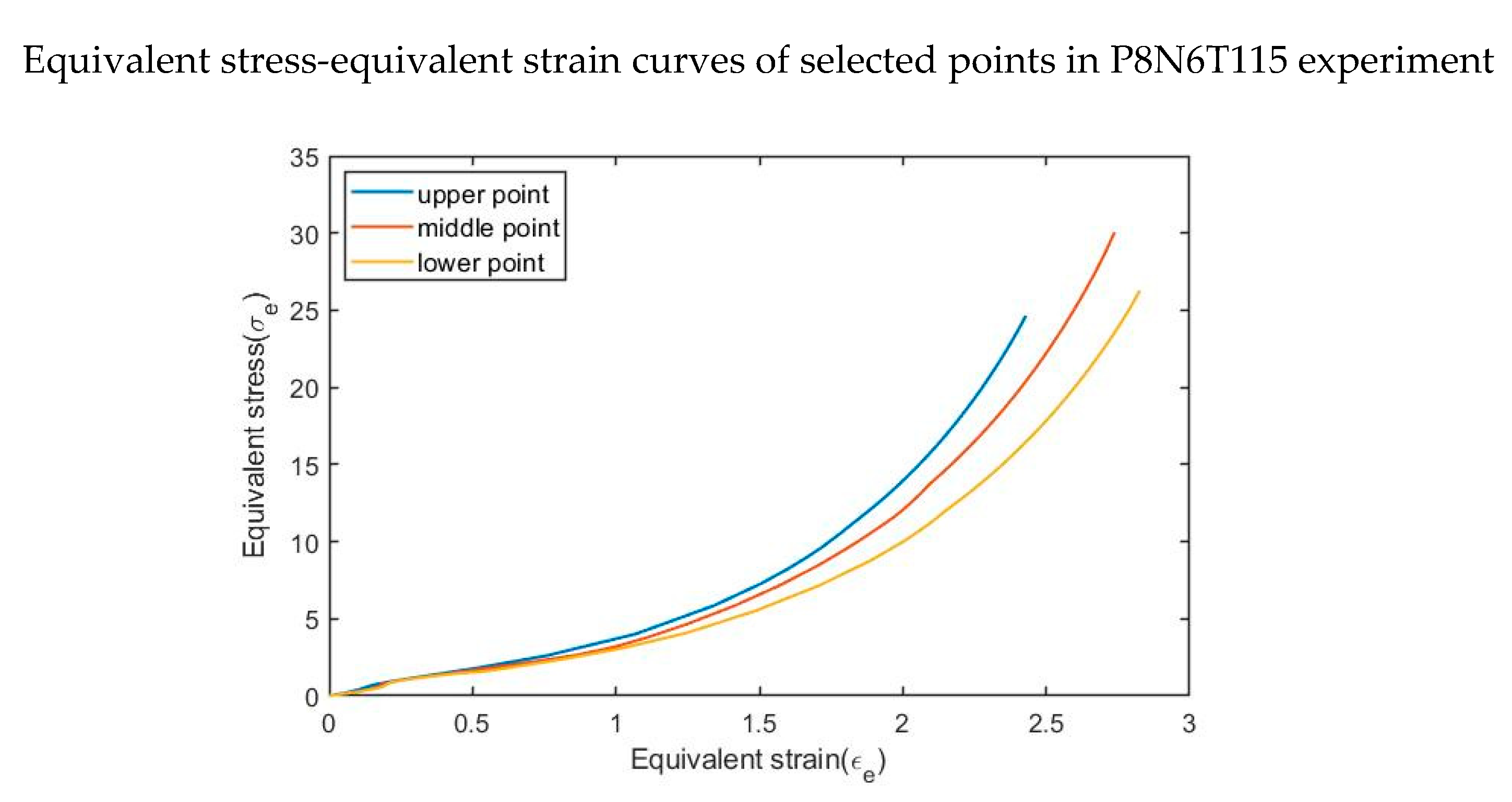

Figure 16.

equivalent stress-equivalent strain curves of selected points in P8N6T115.

Figure 16.

equivalent stress-equivalent strain curves of selected points in P8N6T115.

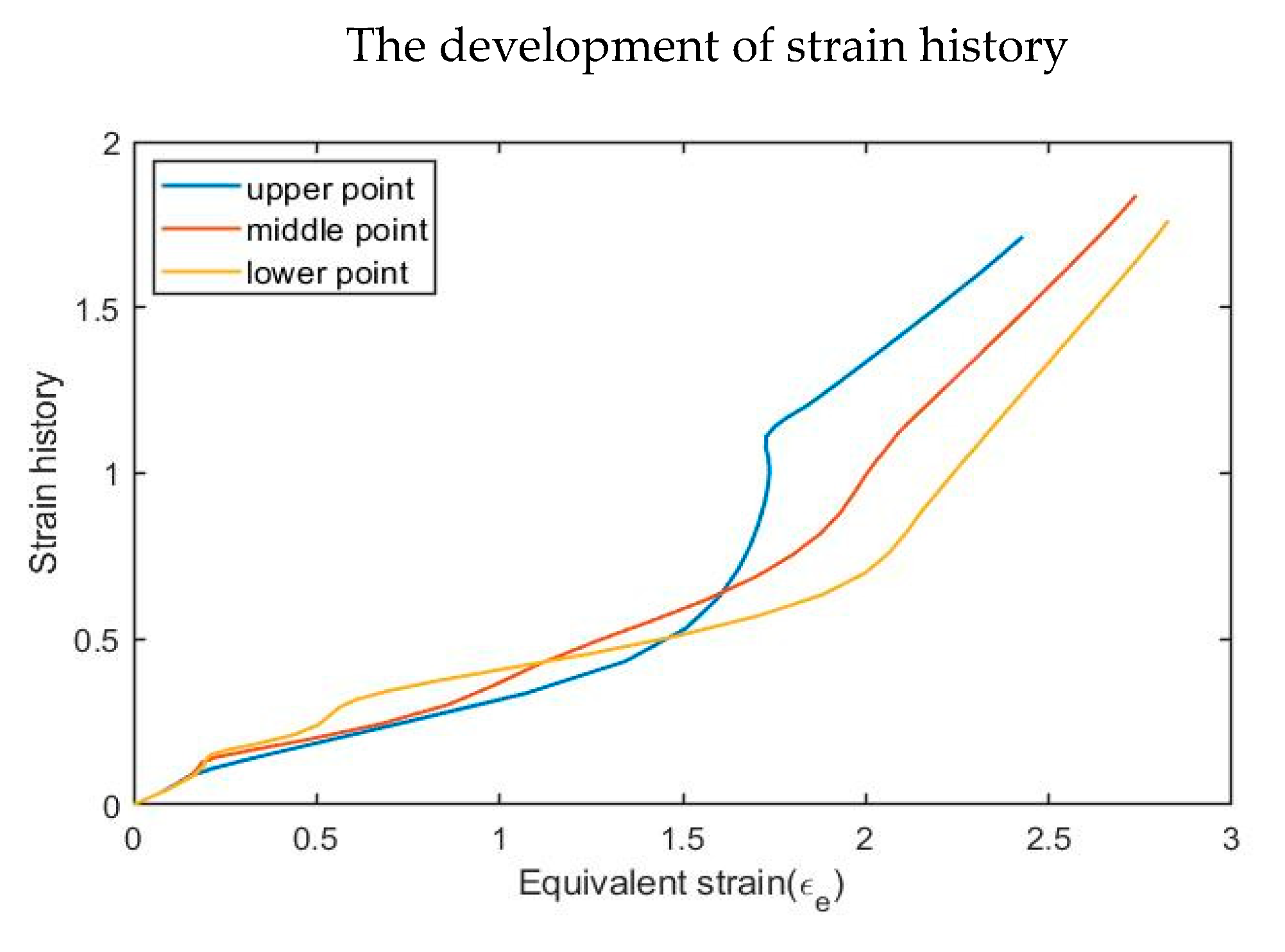

Figure 17.

The development of strain history of selected points in P8N2T115.

Figure 17.

The development of strain history of selected points in P8N2T115.

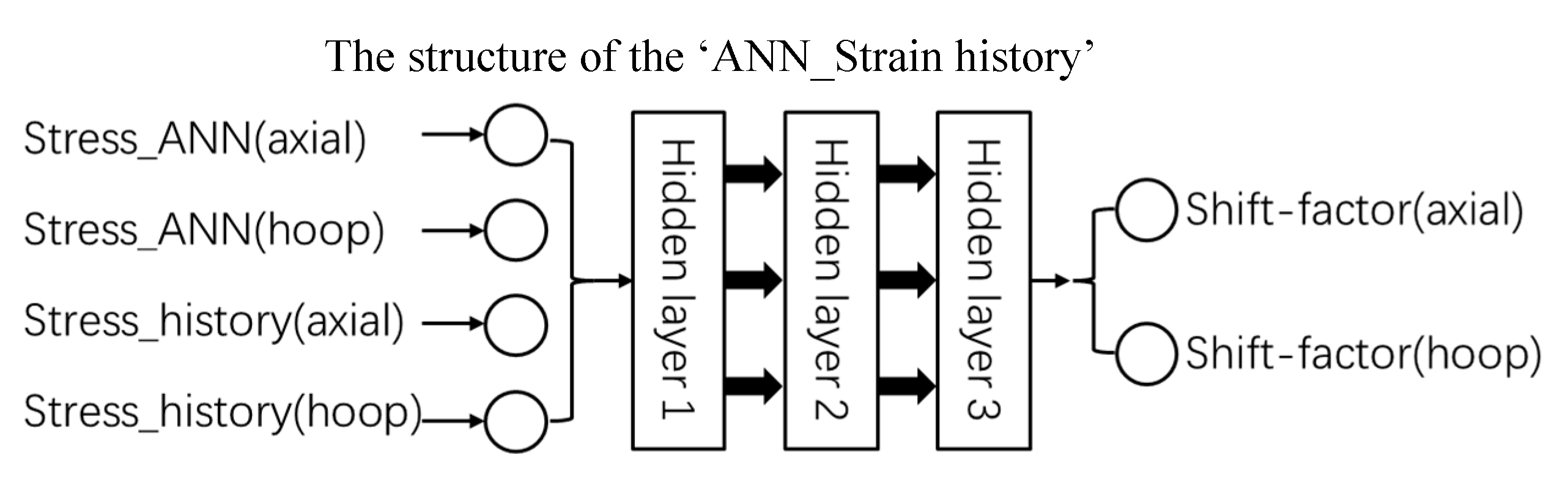

Figure 18.

the structure of the ‘ANN_Strain history’.

Figure 18.

the structure of the ‘ANN_Strain history’.

Figure 19.

Schematic diagram of ‘shift-factors’ for selected points in P8N6T115.

Figure 19.

Schematic diagram of ‘shift-factors’ for selected points in P8N6T115.

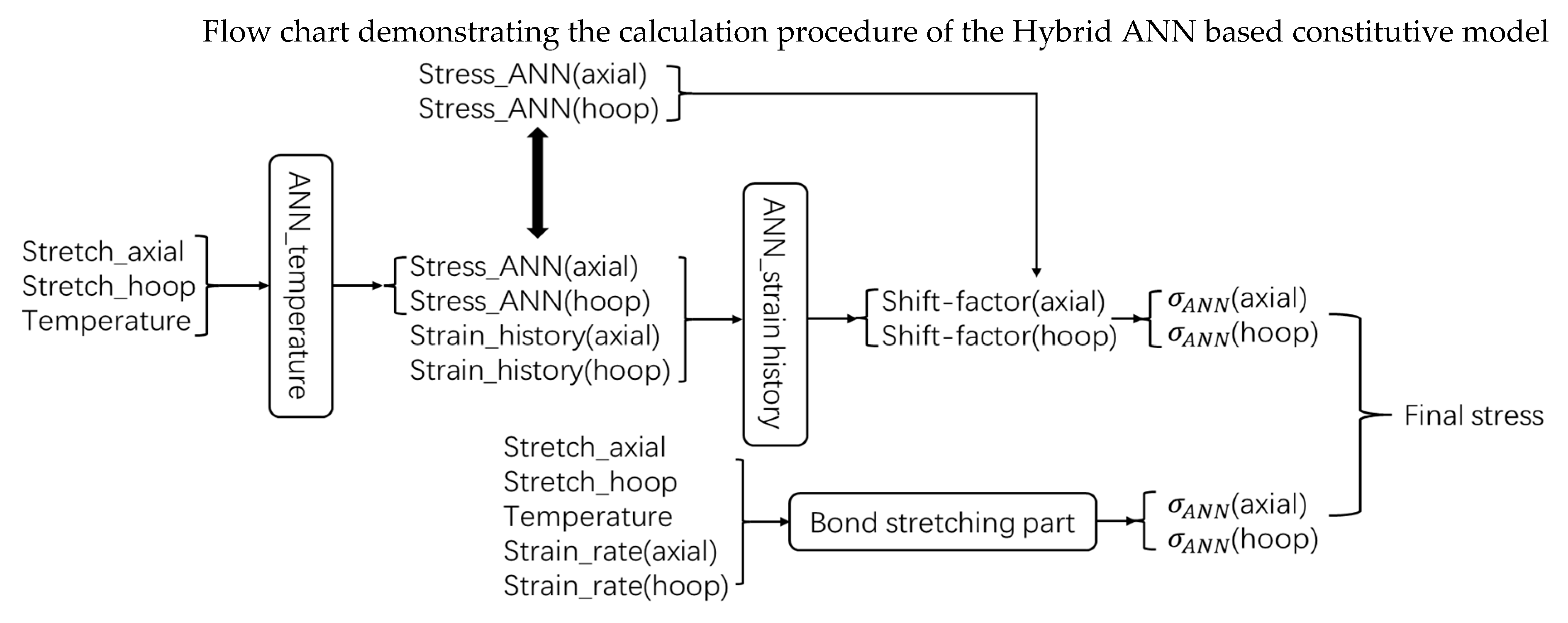

Figure 20.

Flow chart demonstrating the calculation procedure of the Hybrid ANN based constitutive model.

Figure 20.

Flow chart demonstrating the calculation procedure of the Hybrid ANN based constitutive model.

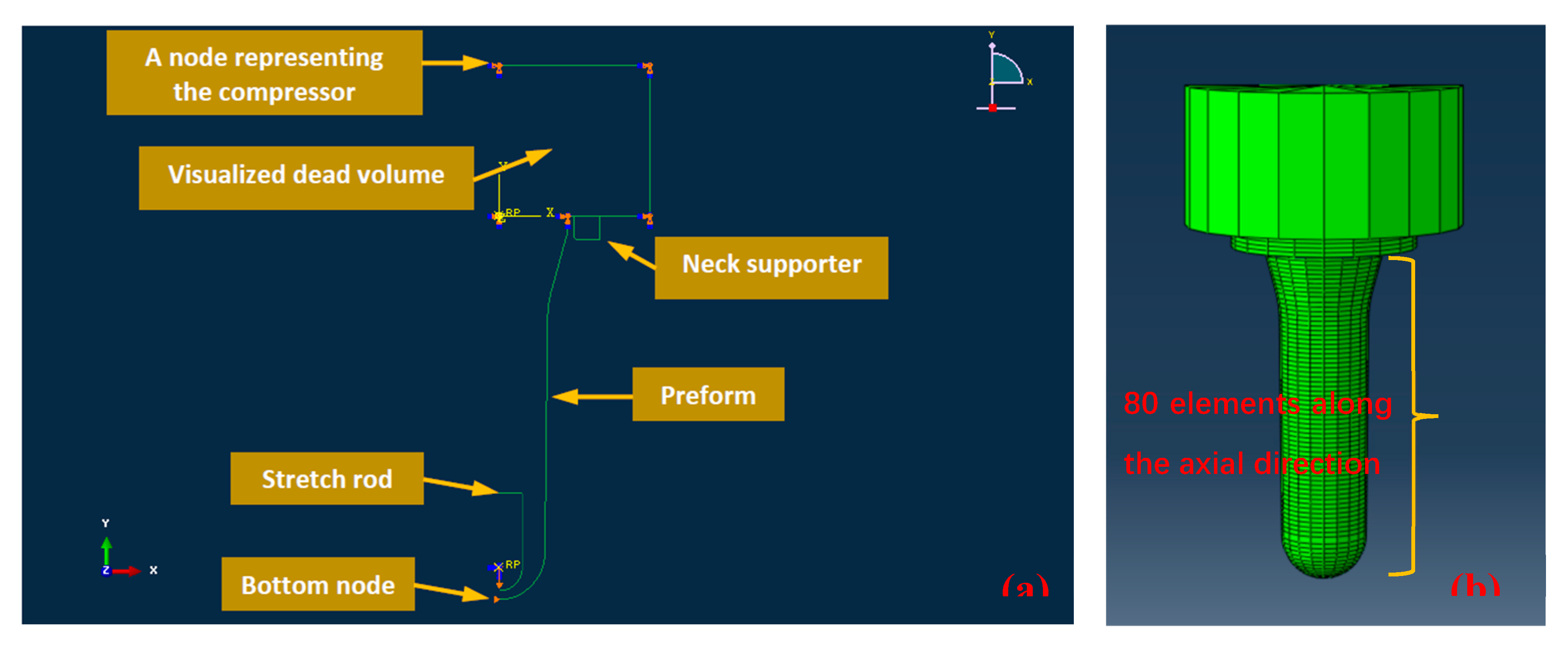

Figure 22.

detailed FE model used for free stretch blow simulation, (a) annotated CAE interface to illustrate the model of free stretch-blow process in ABAQUS/Explicit; (b) FE preform model with 80 SAX1 elements.

Figure 22.

detailed FE model used for free stretch blow simulation, (a) annotated CAE interface to illustrate the model of free stretch-blow process in ABAQUS/Explicit; (b) FE preform model with 80 SAX1 elements.

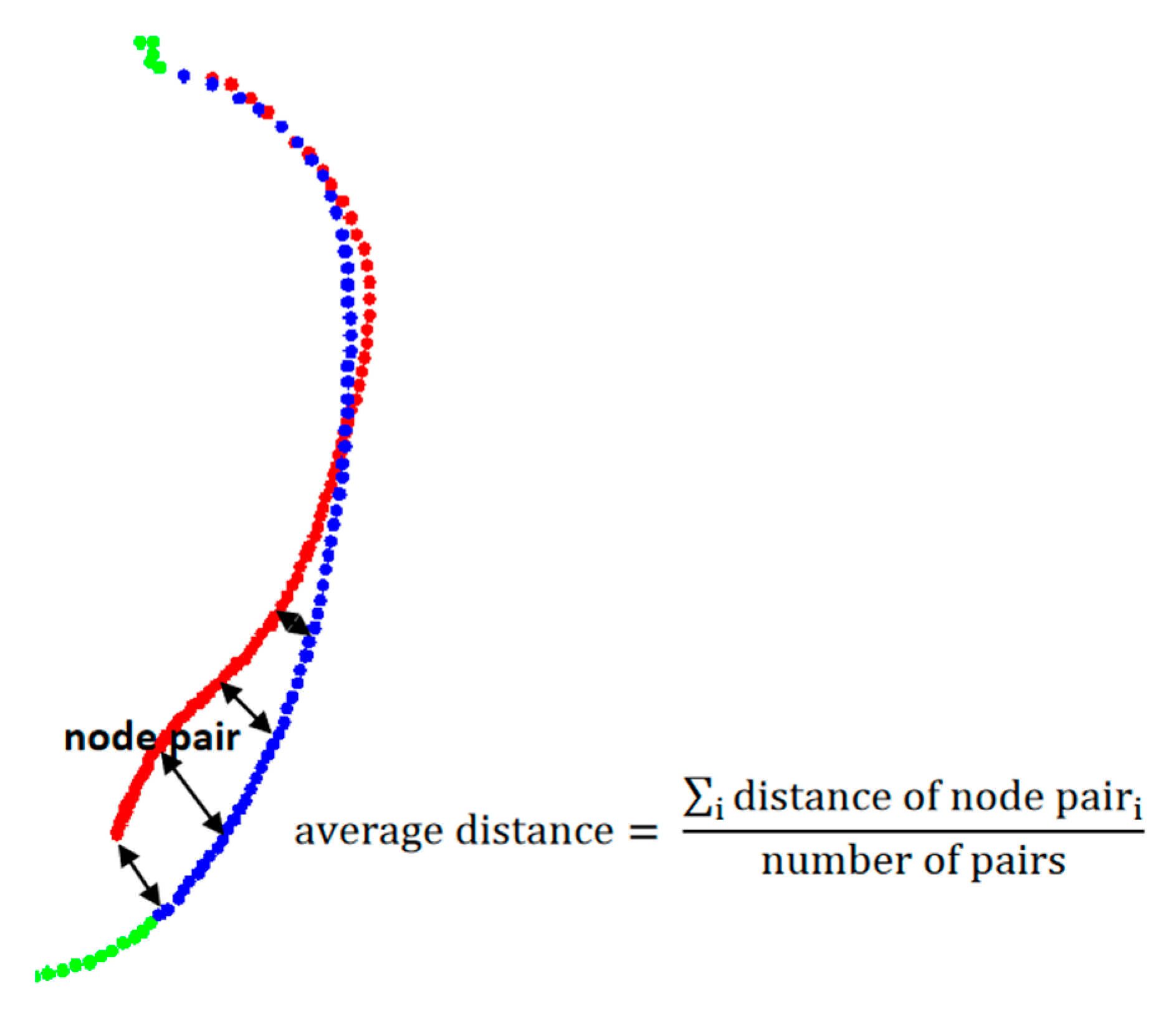

Figure 23.

illustration of distance between node pair, and the equation of calculating the average distance.

Figure 23.

illustration of distance between node pair, and the equation of calculating the average distance.

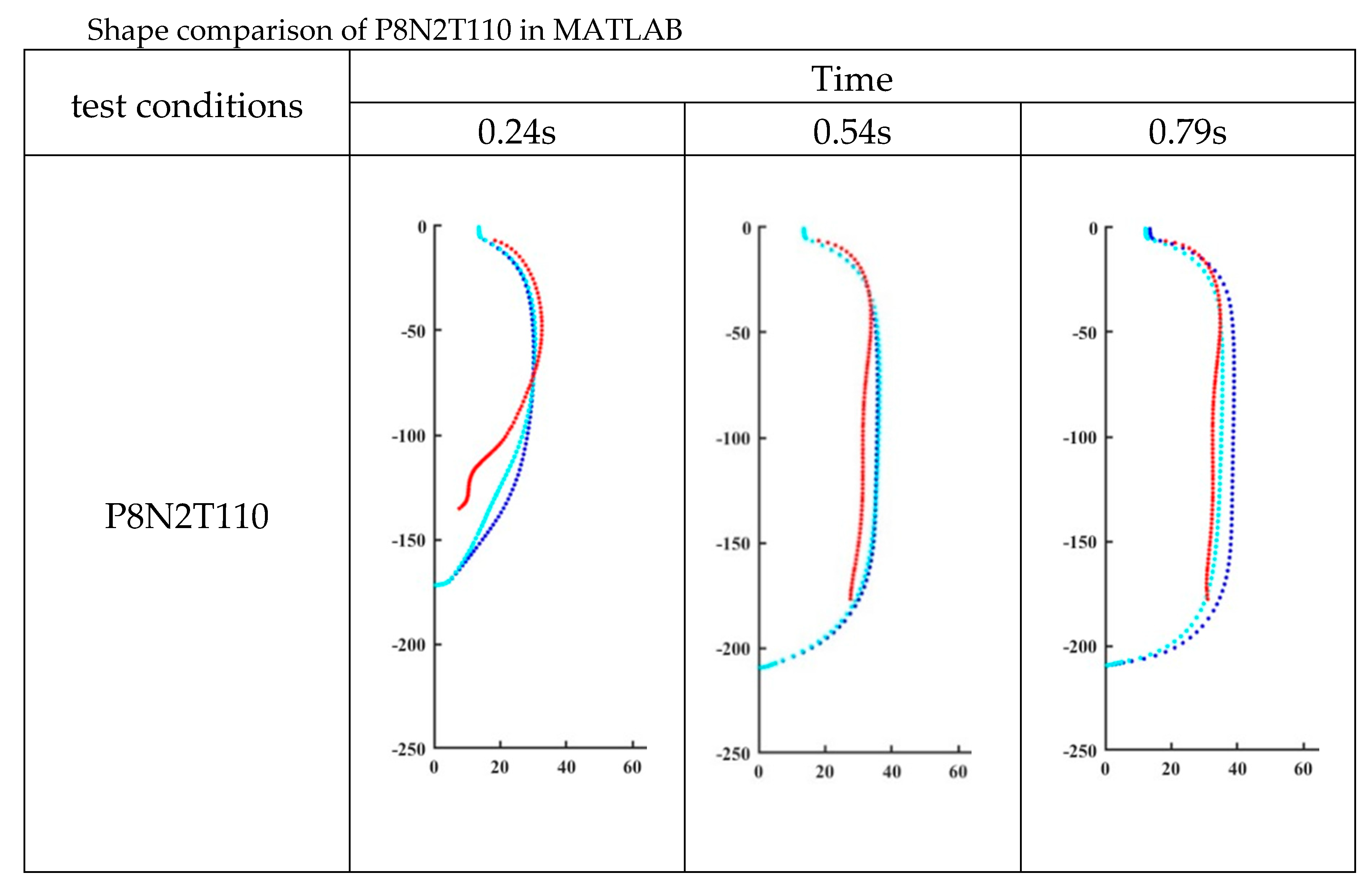

Figure 24.

Shape comparison of P8N2T110 in MATLAB.

Figure 24.

Shape comparison of P8N2T110 in MATLAB.

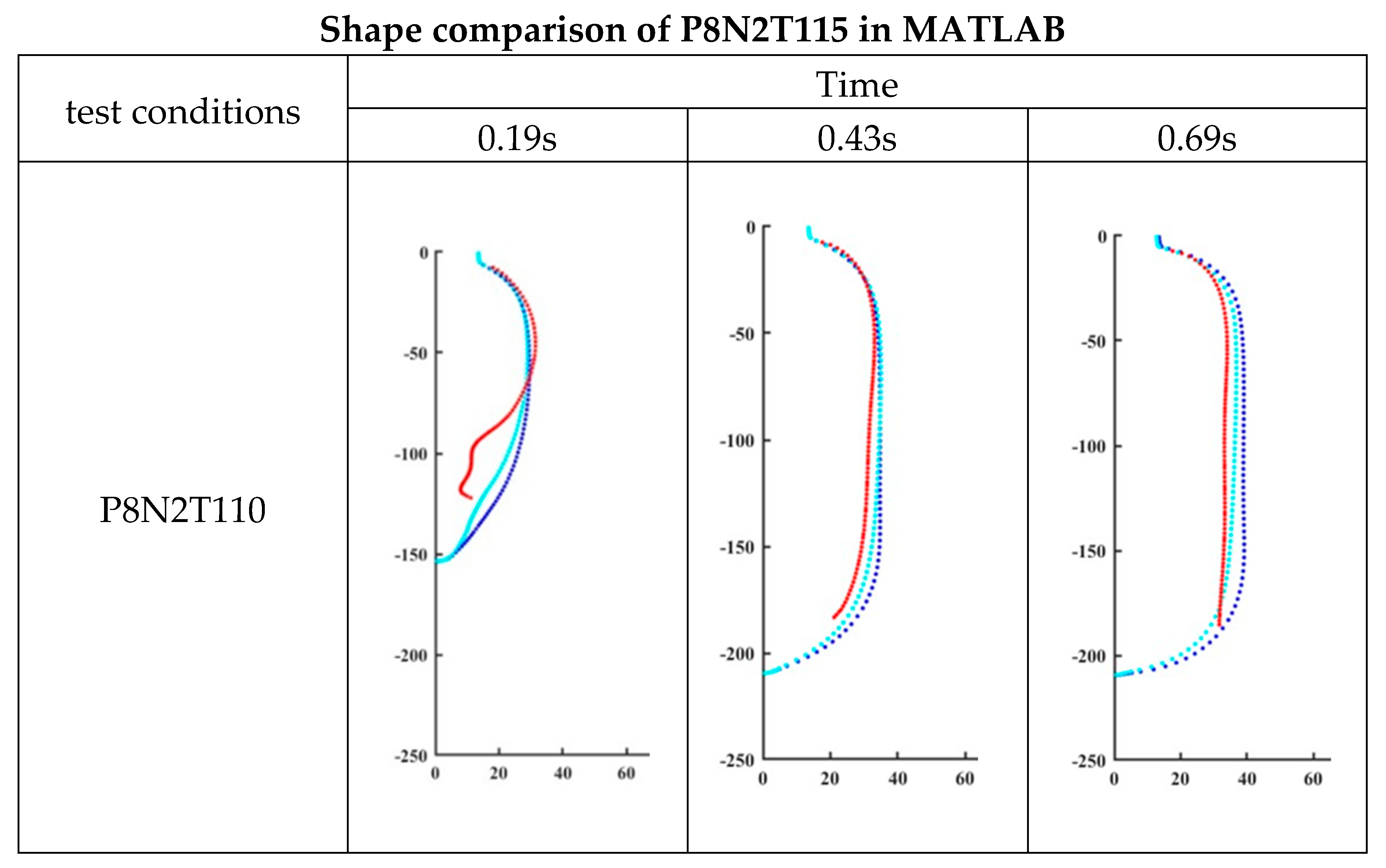

Figure 25.

Shape comparison of P8N2T115 in MATLAB.

Figure 25.

Shape comparison of P8N2T115 in MATLAB.

Table 1.

Summary of experiments conducted.

Table 1.

Summary of experiments conducted.

Experiment label

(Press/Flow/temp) |

Pressure, P (bar) |

Flow index, N (1-6) |

Temperature setting of oil bath( ℃ ) |

| P8N2T95 |

8 |

2 |

95 |

| P8N6T95 |

8 |

6 |

95 |

| P8N2T100 |

8 |

2 |

100 |

| P8N6T100 |

8 |

6 |

100 |

| P8N2T105 |

8 |

2 |

105 |

| P8N6T105 |

8 |

6 |

105 |

| P8N2T110 |

8 |

2 |

110 |

| P8N6T110 |

8 |

6 |

110 |

| P8N2T115 |

8 |

2 |

115 |

| P8N6T115 |

8 |

6 |

115 |

Table 2.

The Mean Relative Error(MRE) of experiments shown in

Figure 20.

Table 2.

The Mean Relative Error(MRE) of experiments shown in

Figure 20.

| Experiment label |

Mean relative error |

| P8N2T95 |

1.37% |

| P8N6T95 |

1.16% |

| P8N2T100 |

2.14% |

| P8N6T100 |

2.42% |

| P8N2T105 |

2.57% |

| P8N6T110 |

2.00% |

| P8N6T115 |

4.14% |

Table 3.

Detailed ‘average distance’ of simulation results.

Table 3.

Detailed ‘average distance’ of simulation results.

| |

Buckley model simulation |

Hybrid ANN based constitutive mode simulation |

| P8N2T110 |

8.11 |

6.21 |

| P8N2T115 |

12.39 |

8.83 |