Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population and Study Design

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. ELISA Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological Features of Patients

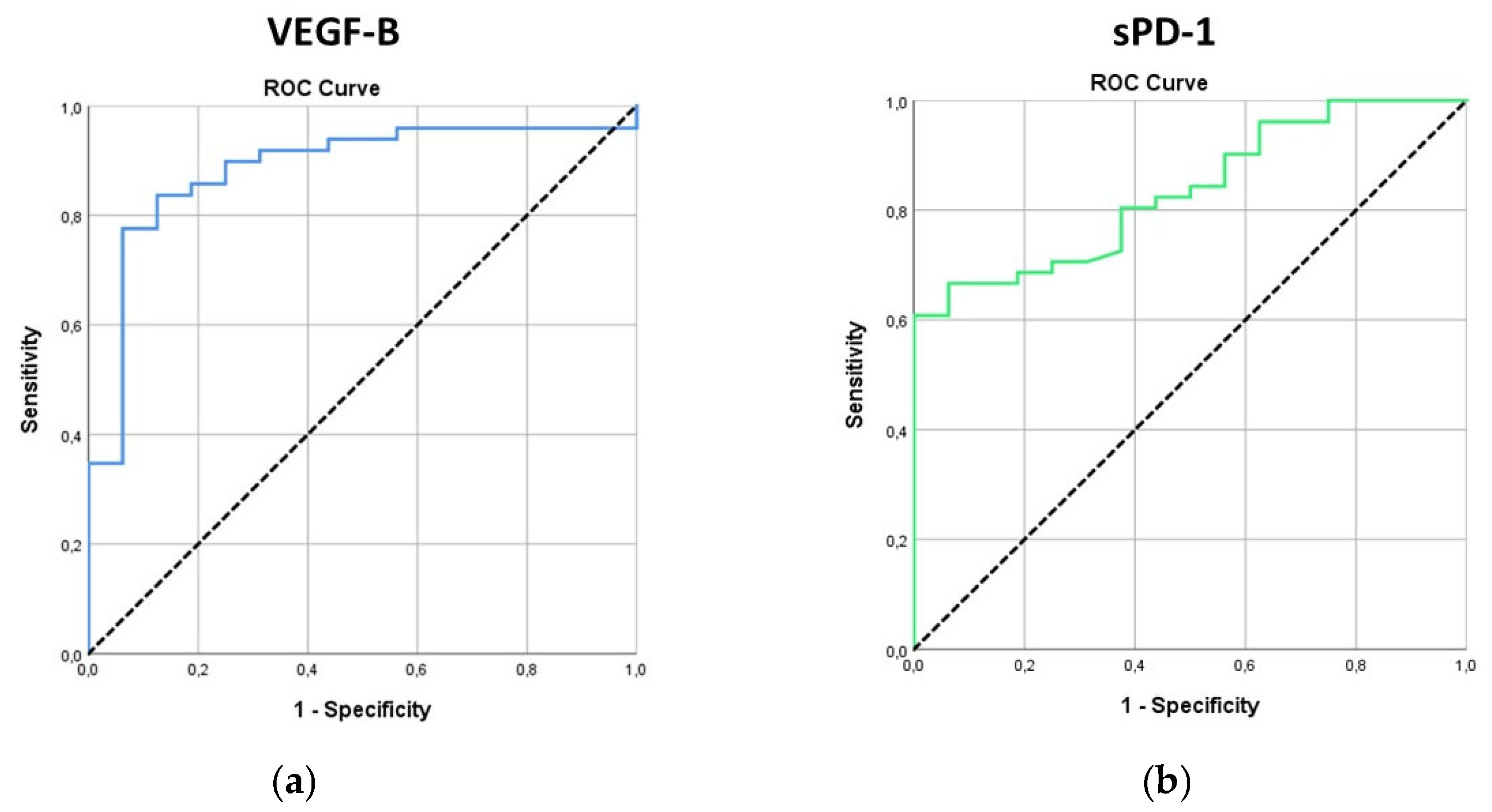

3.2. Levels of Biomarkers and Their Diagnostic Accuracy

3.3. Associations Between Biomarkers and Clinicopathological Features

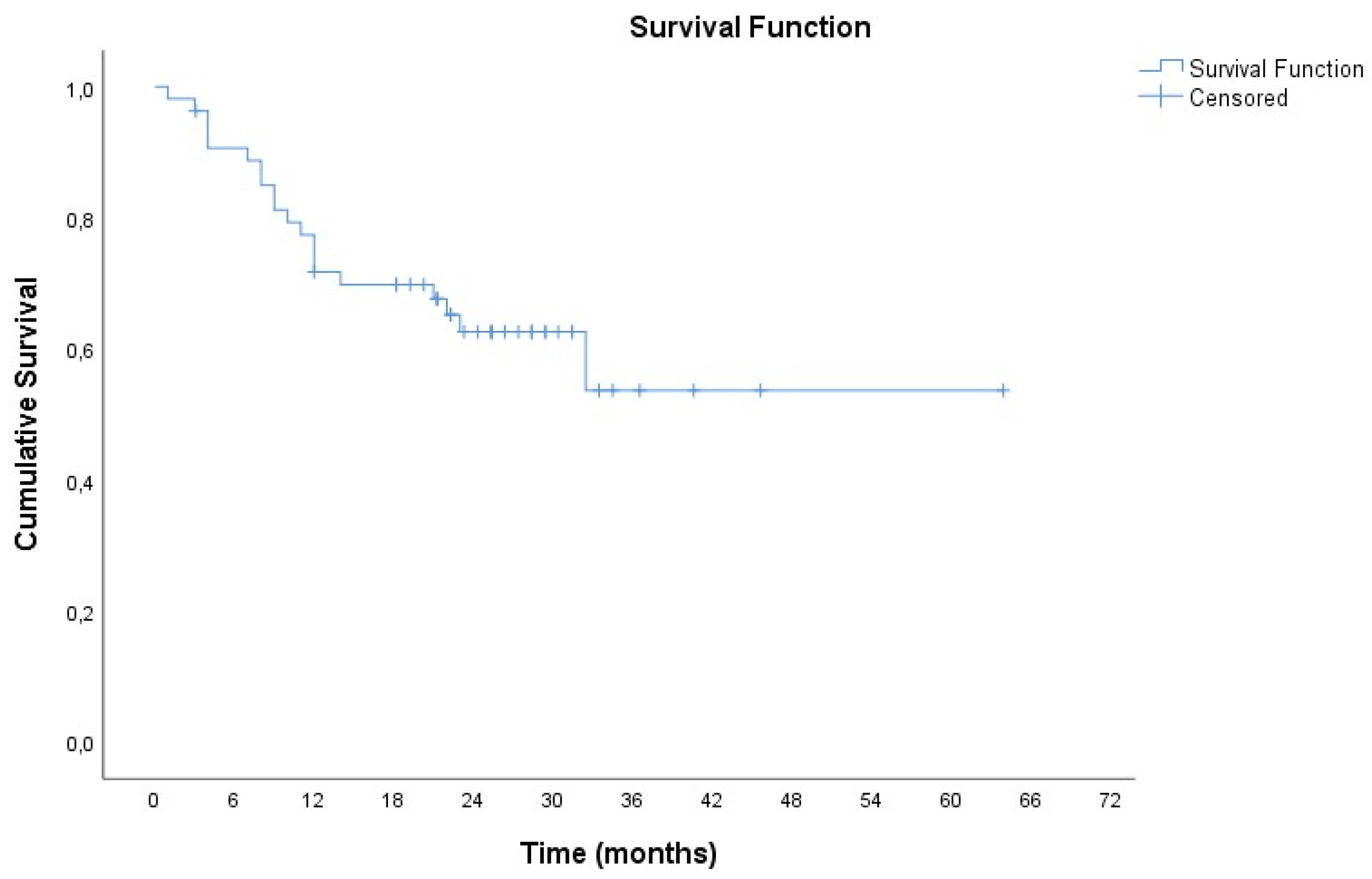

3.3. Correlation with Treatment Response and Survival Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mogavero, A.; Cantale, O.; Mollica, V.; Anpalakhan, S.; Addeo, A.; Mountzios, G.; Friedlaender, A.; Kanesvaran, R.; Novello, S.; Banna, G.L. First-line immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: how to select and where to go. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2023, 17, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; O'Brien, M.; Rao, S.; Hotta, K.; Vandormael, K.; Riccio, A.; Yang, J.; Pietanza, M.C.; Brahmer, J.R. Updated Analysis of KEYNOTE-024: Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. J Clin Oncol. 2019, 37, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; O'Brien, M.; Rao, S.; Hotta, K.; Leal, T.A.; Riess, J.W.; Jensen, E.; Zhao, B.; Pietanza, M.C.; Brahmer, J.R. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol. 2021, 39, 2339–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Herbst, R.S.; Giaccone, G.; de Marinis, F.; Reinmuth, N.; Vergnenegre, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Morise, M.; Felip, E.; Andric, Z.; Geater, S.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Zou, W.; Sandler, A.; Enquist, I.; Komatsubara, K.; Deng, Y.; Kuriki, H.; Wen, X.; McCleland, M.; Mocci, S.; Jassem, J.; Spigel, D.R. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1-Selected Patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezer, A.; Kilickap, S.; Gümüş, M.; Bondarenko, I.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Gogishvili, M.; Turk, H.M.; Cicin, I.; Bentsion, D.; Gladkov, O.; Clingan, P.; Sriuranpong, V.; Rizvi, N.; Gao, B.; Li, S.; Lee, S.; McGuire, K.; Chen, C.I.; Makharadze, T.; Paydas, S.; Nechaeva, M.; Seebach, F.; Weinreich, D.M.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Gullo, G.; Lowy, I.; Rietschel, P. Cemiplimab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 of at least 50%: a multicentre, open-label, global, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021, 397, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macioch, T.; Krzakowski, M.; Gołębiewska, K.; Dobek, M.; Warchałowska, N.; Niewada, M. Pembrolizumab monotherapy survival benefits in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review of real-world data. Discov Oncol. 2024, 15, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wagenius, G.; Vikström, A.; Berglund, A.; Salomonsson, S.; Bencina, G.; Hu, X.; Chirovsky, D.; Brunnström, H. First-line Treatment Patterns and Outcomes in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in Sweden: A Population-based Real-world Study with Focus on Immunotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2024, 63, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amrane, K.; Geier, M.; Corre, R.; Léna, H.; Léveiller, G.; Gadby, F.; Lamy, R.; Bizec, J.L.; Goarant, E.; Robinet, G.; Gouva, S.; Quere, G.; Abgral, R.; Schick, U.; Bernier, C.; Chouaid, C.; Descourt, R. First-line pembrolizumab for non-small cell lung cancer patients with PD-L1 ≥50% in a multicenter real-life cohort: The PEMBREIZH study. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 2309–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cortellini, A.; Cannita, K.; Tiseo, M.; Cortinovis, D.L.; Aerts, J.G.J.V.; Baldessari, C.; Giusti, R.; Ferrara, M.G.; D'Argento, E.; Grossi, F.; Guida, A.; Berardi, R.; Morabito, A.; Genova, C.; Antonuzzo, L.; Mazzoni, F.; De Toma, A.; Signorelli, D.; Gelibter, A.; Targato, G.; Rastelli, F.; Chiari, R.; Rocco, D.; Gori, S.; De Tursi, M.; Mansueto, G.; Zoratto, F.; Filetti, M.; Bracarda, S.; Citarella, F.; Russano, M.; Cantini, L.; Nigro, O.; Buti, S.; Minuti, G.; Landi, L.; Ricciardi, S.; Migliorino, M.R.; Natalizio, S.; Simona, C.; De Filippis, M.; Metro, G.; Adamo, V.; Russo, A.; Spinelli, G.P.; Di Maio, M.; Banna, G.L.; Friedlaender, A.; Addeo, A.; Pinato, D.J.; Ficorella, C.; Porzio, G. Post-progression outcomes of NSCLC patients with PD-L1 expression ≥ 50% receiving first-line single-agent pembrolizumab in a large multicentre real-world study. Eur J Cancer. 2021, 148, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Xie, M.; Yao, J.; Ma, X.; Qin, L.; Zhang, X.M.; Song, J.; Bao, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, W.; Liang, Y.; Jing, Y.; Xue, X. Immune-related adverse events in non-small cell lung cancer: Occurrence, mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Clin Transl Med. 2024, 14, e1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spagnolo, C.C.; Pepe, F.; Ciappina, G.; Nucera, F.; Ruggeri, P.; Squeri, A.; Speranza, D.; Silvestris, N.; Malapelle, U.; Santarpia, M. Circulating biomarkers as predictors of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in NSCLC: Are we on the right path? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024, 197, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisone, D.; Friedlaender, A.; Addeo, A.; Tsantoulis, P. The Landscape of Immunotherapy Resistance in NSCLC. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 817548, Erratum in: Front Oncol. 2023 Apr 04;13:1187021. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1187021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qi, C.; Li, Y.; Zeng, H.; Wei, Q.; Tan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Tian, P. Current status and progress of PD-L1 detection: guiding immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Exp Med. 2024, 24, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- So, W.V.; Dejardin, D.; Rossmann, E.; Charo, J. Predictive biomarkers for PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor response in NSCLC: an analysis of clinical trial and real-world data. J Immunother Cancer. 2023, 11, e006464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosca, O.C.; Vele, O.E. Microsatellite Instability, Mismatch Repair, and Tumor Mutation Burden in Lung Cancer. Surg Pathol Clin. 2024, 17, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahma, O.E.; Hodi, F.S. The Intersection between Tumor Angiogenesis and Immune Suppression. Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5449–5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Kim, B.Y.S.; Chan, C.K.; Hahn, S.M.; Weissman, I.L.; Jiang, W. Improving immune-vascular crosstalk for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018, 18, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, K.; Guo, Q.; Li, X. Efficacy and safety of combined immunotherapy and antiangiogenic therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a real-world observation study. BMC Pulm Med. 2023, 23, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fang, L.; Zhao, W.; Ye, B.; Chen, D. Combination of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Anti-Angiogenic Agents in Brain Metastases From Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 670313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, D.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J.; Bai, H.; Wang, J. Research advances in mechanism of antiangiogenic therapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors for treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1265865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goldstraw, P.; Chansky, K.; Crowley, J.; Rami-Porta, R.; Asamura, H.; Eberhardt, W.E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Groome, P.; Mitchell, A.; Bolejack, V.; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee, Advisory Boards, and Participating Institutions; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee Advisory Boards and Participating Institutions. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016, 11, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grangeon, M.; Tomasini, P.; Chaleat, S.; Jeanson, A.; Souquet-Bressand, M.; Khobta, N.; Bermudez, J.; Trigui, Y.; Greillier, L.; Blanchon, M.; Boucekine, M.; Mascaux, C.; Barlesi, F. Association Between Immune-related Adverse Events and Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019, 20, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Chang, J.; Liu, P.; Tian, X.; Yu, J. Prognostic significance of programmed cell death ligand 1 blood markers in non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1400262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Dai, L. Soluble PD-L1 as a predictive biomarker in lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; He, H. Prognostic value of soluble programmed cell death ligand-1 in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 2022, 14, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazekas, T.; Váncsa, S.; Váradi, M.; Kovács, P.T.; Krafft, U.; Grünwald, V.; Hadaschik, B.; Csizmarik, A.; Hegyi, P.; Váradi, A.; Nyirády, P.; Szarvas, T. Pre-treatment soluble PD-L1 as a predictor of overall survival for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023, 72, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Himuro, H.; Nakahara, Y.; Igarashi, Y.; Kouro, T.; Higashijima, N.; Matsuo, N.; Murakami, S.; Wei, F.; Horaguchi, S.; Tsuji, K.; Mano, Y.; Saito, H.; Azuma, K.; Sasada, T. Clinical roles of soluble PD-1 and PD-L1 in plasma of NSCLC patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023, 72, 2829–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bar, J.; Leibowitz, R.; Reinmuth, N.; Ammendola, A.; Jacob, E.; Moskovitz, M.; Levy-Barda, A.; Lotem, M.; Katsenelson, R.; Agbarya, A.; Abu-Amna, M.; Gottfried, M.; Harkovsky, T.; Wolf, I.; Tepper, E.; Loewenthal, G.; Yellin, B.; Brody, Y.; Dahan, N.; Yanko, M.; Lahav, C.; Harel, M.; Raveh Shoval, S.; Elon, Y.; Sela, I.; Dicker, A.P.; Shaked, Y. Biological insights from plasma proteomics of non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1364473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ohkuma, R.; Ieguchi, K.; Watanabe, M.; Takayanagi, D.; Goshima, T.; Onoue, R.; Hamada, K.; Kubota, Y.; Horiike, A.; Ishiguro, T.; Hirasawa, Y.; Ariizumi, H.; Tsurutani, J.; Yoshimura, K.; Tsuji, M.; Kiuchi, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Tsunoda, T.; Wada, S. Increased Plasma Soluble PD-1 Concentration Correlates with Disease Progression in Patients with Cancer Treated with Anti-PD-1 Antibodies. Biomedicines. 2021, 9, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tiako Meyo, M.; Jouinot, A.; Giroux-Leprieur, E.; Fabre, E.; Wislez, M.; Alifano, M.; Leroy, K.; Boudou-Rouquette, P.; Tlemsani, C.; Khoudour, N.; Arrondeau, J.; Thomas-Schoemann, A.; Blons, H.; Mansuet-Lupo, A.; Damotte, D.; Vidal, M.; Goldwasser, F.; Alexandre, J.; Blanchet, B. Predictive Value of Soluble PD-1, PD-L1, VEGFA, CD40 Ligand and CD44 for Nivolumab Therapy in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Case-Control Study. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hosaka, K.; Andersson, P.; Wang, J.; Tholander, F.; Cao, Z.; Morikawa, H.; Tegnér, J.; Yang, Y.; Iwamoto, H.; Lim, S.; Cao, Y. VEGF-B promotes cancer metastasis through a VEGF-A-independent mechanism and serves as a marker of poor prognosis for cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015, 112, E2900-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanmartín, E.; Sirera, R.; Usó, M.; Blasco, A.; Gallach, S.; Figueroa, S.; Martínez, N.; Hernando, C.; Honguero, A.; Martorell, M.; Guijarro, R.; Rosell, R.; Jantus-Lewintre, E.; Camps, C. A gene signature combining the tissue expression of three angiogenic factors is a prognostic marker in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014, 21, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozuka, T.; Yanagitani, N.; Sakamoto, H.; Yoshida, H.; Amino, Y.; Uematsu, S.; Yoshizawa, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Ariyasu, R.; Uchibori, K.; Kitazono, S.; Seike, M.; Gemma, A.; Nishio, M. Association between continuous decrease of plasma VEGF-A levels and the efficacy of chemotherapy in combination with anti-programmed cell death 1 antibody in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2020, 25, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Hui, K.; Gu, J.; Wang, M.; Hu, C.; Jiang, X. Plasma sPD-L1 and VEGF levels are associated with the prognosis of NSCLC patients treated with combination immunotherapy. Anticancer Drugs. 2024, 35, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Li, S.; Xiao, H.; Xiong, Y.; Lu, X.; Yang, X.; Luo, W.; Luo, J.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dai, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, M. Distinct circulating cytokine/chemokine profiles correlate with clinical benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy and combination therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 12234–12252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shibaki, R.; Murakami, S.; Shinno, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Goto, Y.; Kanda, S.; Horinouchi, H.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Yamamoto, N.; Ohe, Y. Predictive value of serum VEGF levels for elderly patients or for patients with poor performance status receiving anti-PD-1 antibody therapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020, 69, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Rui, Z.; Tang, W.; Xu, Y.; Tao, X.; Zhao, Q.; Tong, X. A comprehensive profiling of soluble immune checkpoints from the sera of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022, 36, e24224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, J.; Pan, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, B.; Tang, Y. Study on the Expression Levels and Clinical Significance of PD-1 and PD-L1 in Plasma of NSCLC Patients. J Immunother. 2020, 43, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Tang, Y.Y.; Wan, J.X.; Zou, J.Y.; Lu, C.G.; Zhu, H.S.; Sheng, S.Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Liu, H.C.; Yang, J.; Hong, H. Sex difference in the expression of PD-1 of non-small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1026214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patients (n=55) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 38 (69.1) | |

| Female | 17 (30.9) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 66.5 (8.0) | |

| Pack-Years, mean (SD) | 64.7 (27.6) | |

| ECOG Performance Status | ||

| 0 | 12 (21.8) | |

| 1 | 34 (61.8) | |

| 2 | 8 (14.5) | |

| 3 | 1 (1.8) | |

| Type of treatment | ||

| Pembrolizumab monotherapy | 19(34.5) | |

| Pembrolizumab + chemotherapy | 36(65.5) | |

| Treatment line | ||

| 1 | 44 (84.6) | |

| 2 | 7 (13.5) | |

| 3 | 1 (1.9) | |

| Disease Stage | ||

| ΙΙΙ | 4 (7.3) | |

| IV | 51 (92.7) | |

| Histological type of tumor | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 35 (63.6) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 18(32.7) | |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 1 (1.8) | |

| NOS | 1 (1.8) | |

| PD-L1, mean (SD) | 44.7 (36) | |

| Response to treatment | ||

| Partial response | 14 (25.9) | |

| Stable disease | 21 (38.9) | |

| Disease progression | 19 (35.2) | |

| Toxicity (irAEs) | 22 (40.0) | |

| Healthy controls (n=16) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 9 (56.3) | |

| Female | 7 (43.8) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 65.4 (9.1) | |

| n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | |||

| VEGFA | 51 | 504.86 (311.46) | 433.05 (221.39 ─ 731.57) |

| VEGFB | 49 | 77.22 (474.79) | 4.97 (3.02 ─ 8.2) |

| sPD-L1 | 51 | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.16 (0.09 ─ 0.25) |

| sPD-1 | 51 | 18.17 (17.52) | 12.29 (3.75 ─ 29.17) |

| Post-treatment | |||

| VEGFA | 42 | 430.17 (286.33) | 321.19 (214.66 ─ 650.97) |

| VEGFB | 42 | 17.69 (31.66) | 6.44 (4.13 ─ 16.8) |

| sPD-L1 | 43 | 0.2 (0.11) | 0.16 (0.11 ─ 0.3) |

| sPD-1 | 42 | 56.22 (99.02) | 40.31 (22.92 ─ 52.68) |

| Change | |||

| VEGFA | 40 | -62.95 (218.99) | -19.26 (-148.18 ─ 94.36) |

| VEGFB | 38 | -78.62 (514.62) | 1.74 (-1.18 ─ 3.83) |

| sPD-L1 | 41 | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.01 (-0.06 ─ 0.09) |

| sPD-1 | 40 | 39.97 (102.04) | 19.06 (6.73 ─ 39.07) |

| Patients | Healthy sample | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ROC | 95% CI | P | Optimal cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

| VEGFA | 504.86 (311.46) | 433.05 (221.39 ─ 731.57) | 410.46 (222.32) | 347.39 (256.17 ─ 552.22) | 0.58 | 0.44 - 0.72 | 0.339 | - | - | - | - | - |

| VEGFB | 77.22 (474.79) | 4.97 (3.02 ─ 8.2) | 53.39 (39.45) | 44.77 (16 ─ 100) | 0.88 | 0.79 - 0.98 | <0.001 | ≤10.94 | 83.7 | 87.5 | 95.3 | 63.6 |

| sPD-L1 | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.16 (0.09 ─ 0.25) | 0.19 (0.1) | 0.15 (0.12 ─ 0.21) | 0.47 | 0.32 - 0.62 | 0.702 | - | - | - | - | - |

| sPD-1 | 18.17 (17.52) | 12.29 (3.75 ─ 29.17) | 73.14 (119.28) | 39.09 (25.17 ─ 63.39) | 0.83 | 0.74 - 0.93 | <0.001 | ≤34.54 | 80.4 | 62.5 | 87.2 | 50 |

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Change | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGFB | sPD-L1 | sPD-1 | VEGFA | VEGFB | sPD-L1 | sPD-1 | VEGFA | VEGFB | sPD-L1 | sPD-1 | ||

| Pretreatment | ||||||||||||

| VEGFA | rho | -0,04 | 0,19 | -0,16 | 0,76 | 0,16 | 0,48 | 0,23 | -0,37 | 0,31 | 0,25 | 0,35 |

| P | 0,780 | 0,192 | 0,256 | <0,001 | 0,330 | 0,002 | 0,160 | 0,019 | 0,061 | 0,109 | 0,025 | |

| VEGFB | rho | 1,00 | 0,26 | 0,09 | -0,04 | 0,45 | 0,17 | 0,00 | 0,08 | -0,26 | -0,04 | -0,05 |

| P | 0,074 | 0,540 | 0,814 | 0,005 | 0,298 | 0,999 | 0,628 | 0,118 | 0,786 | 0,743 | ||

| sPD-L1 | rho | 1,00 | 0,07 | 0,19 | 0,05 | 0,25 | -0,12 | -0,17 | -0,17 | -0,54 | -0,10 | |

| P | 0,622 | 0,234 | 0,747 | 0,109 | 0,477 | 0,308 | 0,316 | <0,001 | 0,545 | |||

| sPD-1 | rho | 1,00 | -0,36 | 0,38 | 0,18 | 0,32 | -0,33 | 0,29 | 0,10 | -0,34 | ||

| P | 0,022 | 0,014 | 0,262 | 0,041 | 0,040 | 0,081 | 0,522 | 0,031 | ||||

| Posttreatment | ||||||||||||

| VEGFA | rho | 1,00 | 0,03 | 0,29 | 0,01 | 0,23 | 0,14 | 0,22 | 0,28 | |||

| P | 0,851 | 0,067 | 0,974 | 0,155 | 0,393 | 0,172 | 0,085 | |||||

| VEGFB | rho | 1,00 | 0,26 | 0,30 | -0,10 | 0,55 | 0,19 | 0,08 | ||||

| P | 0,101 | 0,050 | 0,537 | <0,001 | 0,231 | 0,627 | ||||||

| sPD-L1 | rho | 1,00 | 0,43 | -0,25 | 0,11 | 0,62 | 0,35 | |||||

| P | 0,005 | 0,119 | 0,502 | <0,001 | 0,028 | |||||||

| sPD-1 | rho | 1,00 | -0,42 | 0,34 | 0,56 | 0,74 | ||||||

| P | 0,008 | 0,038 | <0,001 | <0,001 | ||||||||

| Change | ||||||||||||

| VEGFA | rho | 1,00 | -0,20 | -0,10 | -0,20 | |||||||

| P | 0,236 | 0,536 | 0,222 | |||||||||

| VEGFB | rho | 1,00 | 0,26 | 0,21 | ||||||||

| P | 0,120 | 0,212 | ||||||||||

| sPD-L1 | rho | 1,00 | 0,49 | |||||||||

| P | 0,001 | |||||||||||

| HR (95% CI)1 | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | ||

| VEGFA | 0.97 (0.83 ─ 1.13) | 0.673 |

| VEGFB | 1.03 (0.97 ─ 1.10) | 0.297 |

| sPD-L1 | 1.68 (1.02 ─ 2.74) | 0.040 |

| sPD-1 | 10.96 (1.15 ─ 104.19) | 0.037 |

| Post-treatment | ||

| VEGFA | 1.02 (0.85 ─ 1.23) | 0.828 |

| VEGFB | 2.99 (1.01 ─ 8.89) | 0.049 |

| sPD-L1 | 0.30 (0.00 ─ 28.71) | 0.601 |

| sPD-1 | 0.90 (0.45 ─ 1.85) | 0.777 |

| Change | ||

| VEGFA | 0.94 (0.74 ─ 1.20) | 0.628 |

| VEGFB | 0.96 (0.90 ─ 1.03) | 0.243 |

| sPD-L1 | 0.02 (0.00 ─ 1.63) | 0.079 |

| sPD-1 | 0.82 (0.35 ─ 1.96) | 0.659 |

| HR (95% CI)1 | P | |

|---|---|---|

| sPD-L1 pre-treatment | 2.10 (1,16 ─ 3.80) | 0.014 |

| VEGFB post-treatment | 3.37 (1.11 ─ 10.22) | 0.032 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).