Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention and Therapeutics: Recent Developments

3. Major Benefits of Phytochemicals in Comparison with Synthetic Anti-Cancer Drugs

4. Molecular Insights into the Roles of Phytochemicals Against Cancer

5. Terpenes and Anticancer Effects

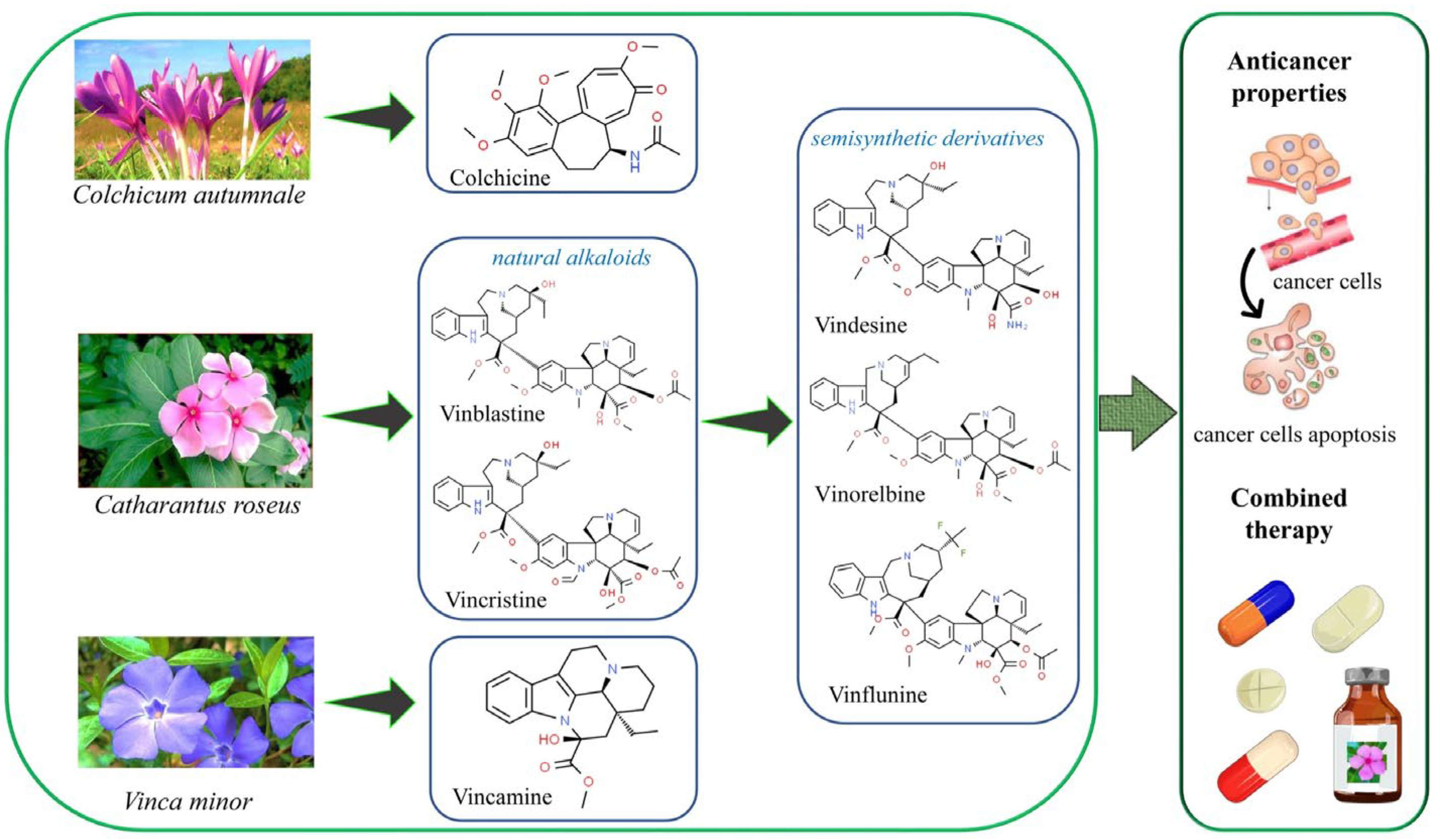

6. Alkaloids and Their Antitumor Effects

7. Organosulphur Compounds Against Cancer

8. Polyphenols Against Cancer

9. Phenolic Lipids Against Cancer

10. Flavonoids and Antitumor Effects

11. Naphthoquinones and Their Anticancer Activities

12. Saponins and Their Anticancer Effects

13. Other Phytochemicals and Their Antitumor Activities

14. Phytochemical-Based Nanoparticles in Cancer Prophylaxis and Therapy

15. Negative Effects of Phytochemicals

16. Expression of Monoclonal Antibodies (Mabs) in Plants

17. Stable Expression of Recombinant Mabs in Transgenic Plants

18. Transient Expression of Plant Based Mabs

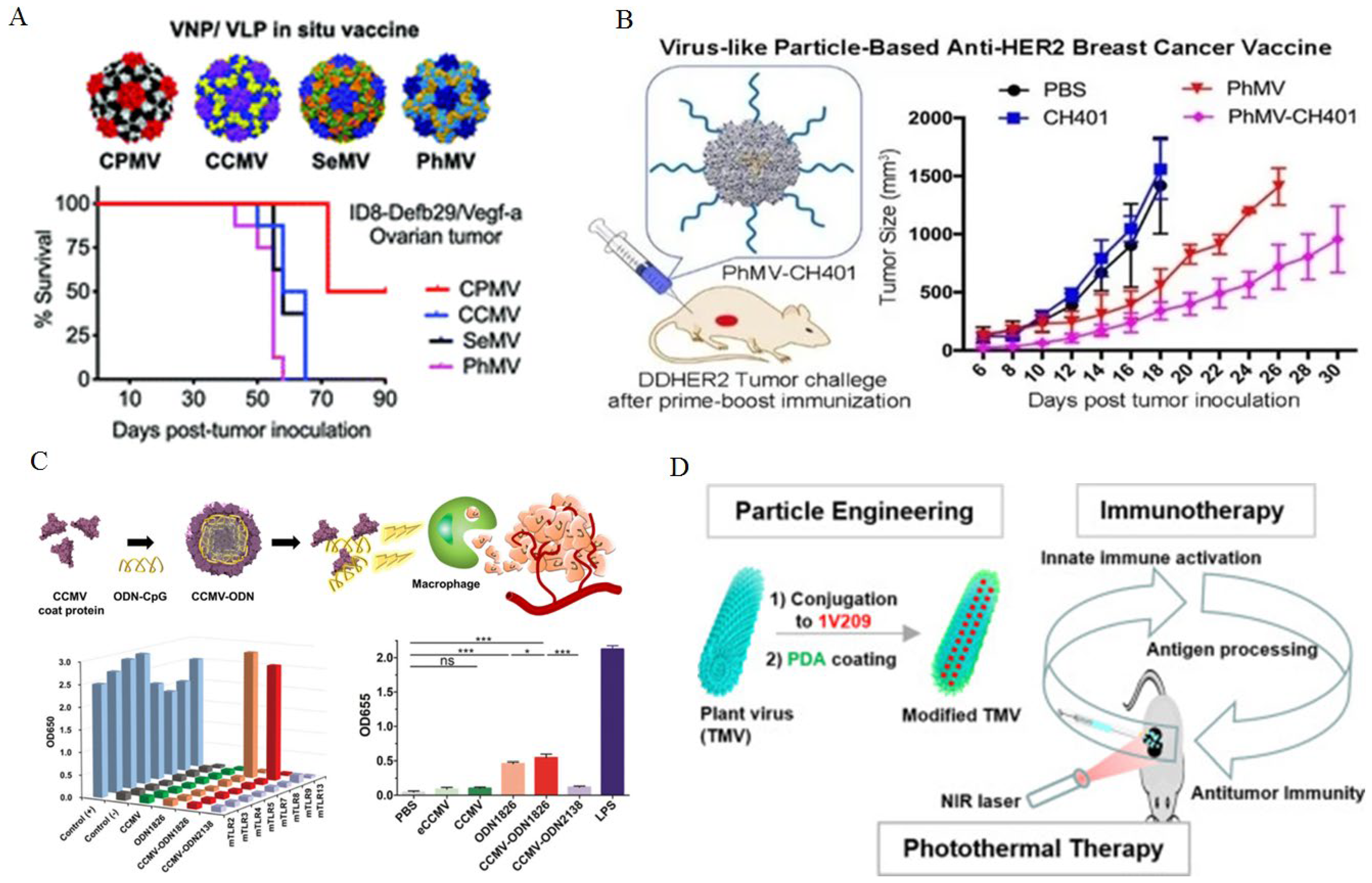

19. Plant Cell Cultures for Mab Production

20. Recent Developments Involving the Expression of Plant-Based Monoclonal Antibodies Against Cancer

21. Plant-Based VNPs and VLPs Against Cancer

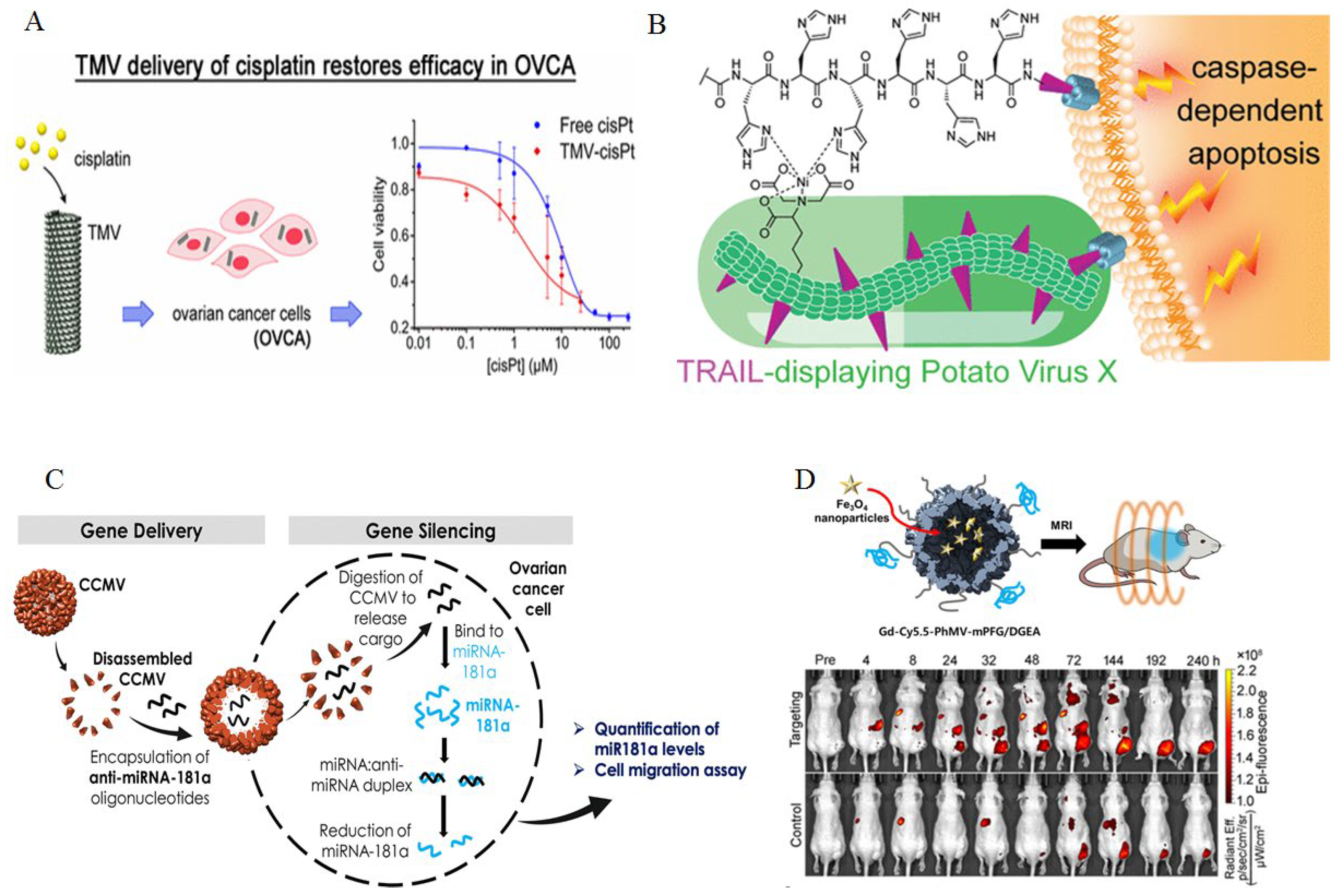

22. PVNPs as Delivery Nanosystem in Cancer

23. PVNPs as Imaging Agents

24. PVNPs as Theranostic Agents

25. PVNPs as Vaccine and Immunotherapy Agents

26. PVNPs -Based Combination Therapies

27. Recent Developments of PVNPs Against Cancer

28. Advantages of the Use of Plants for Production of Anti-Cancer Mabs, Plant Viral Nanoparticles and Phytochemicals Against Cancer

29. Disadvantages of Plant-Based Platforms Against Cancer

30. Regulatory Aspects of Plant-Made Biopharmaceuticals

31. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li S, Chen J, Wang Y, Zhou X, Zhu W: Moxibustion for the side effects of surgical therapy and chemotherapy in patients with gastric cancer: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e21087. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman HL, Atkins MB, Subedi P, Wu J, Chambers J, Joseph Mattingly T, Campbell JD, Allen J, Ferris AE, Schilsky RL: The promise of Immuno-oncology: implications for defining the value of cancer treatment. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer, 2019; 7, 1–11.

- Tiffon C: The impact of nutrition and environmental epigenetics on human health and disease. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, 3425. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo Y, Su Z-Y, Kong A-NT: Current perspectives on epigenetic modifications by dietary chemopreventive and herbal phytochemicals. Current pharmacology reports 2015, 1:245-257.

- Samec M, Liskova A, Kubatka P, Uramova S, Zubor P, Samuel SM, Zulli A, Pec M, Bielik T, Biringer K: The role of dietary phytochemicals in the carcinogenesis via the modulation of miRNA expression. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology, 2019; 145, 1665–1679.

- Lin SR, Chang CH, Hsu CF, Tsai MJ, Cheng H, Leong MK, Sung PJ, Chen JC, Weng CF: Natural compounds as potential adjuvants to cancer therapy: Preclinical evidence. British journal of pharmacology 2020, 177, 1409–1423. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari RB, Homayouni TS, Baluch N, Morgatskaya E, Kumar S, Das B, Yeger H: Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38022. [CrossRef]

- Kamta J, Chaar M, Ande A, Altomare DA, Ait-Oudhia S: Advancing cancer therapy with present and emerging immuno-oncology approaches. Frontiers in oncology, 2017; 7, 64.

- Besufekad Y, Malaiyarsa P: Production of monoclonal antibodies in transgenic plants. J Adv Biol Biotechnol, 2017; 12, 1–8.

- Hefferon K: Reconceptualizing cancer immunotherapy based on plant production systems. Future science OA 2017, 3, FSO217. [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz M, Ebrahimzadeh MS, Miri SM, Dianat-Moghadam H, Ghorbanhosseini SS, Mohebbi SR, Keyvani H, Ghaemi A: Oncolytic Newcastle disease virus delivered by Mesenchymal stem cells-engineered system enhances the therapeutic effects altering tumor microenvironment. Virology journal, 2020; 17, 1–13.

- Shukla S, Hu H, Cai H, Chan S-K, Boone CE, Beiss V, Chariou PL, Steinmetz NF: Plant viruses and bacteriophage-based reagents for diagnosis and therapy. Annual review of virology 2020, 7, 559–587. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyanani V, Haley JC, Goswami R: Challenges of current anticancer treatment approaches with focus on liposomal drug delivery systems. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 835. [CrossRef]

- Nonnekens J, Hoeijmakers JH: After surviving cancer, what about late life effects of the cure? EMBO molecular medicine 2017, 9, 4–6. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho FS, Burgeiro A, Garcia R, Moreno AJ, Carvalho RA, Oliveira PJ: Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: from bioenergetic failure and cell death to cardiomyopathy. Medicinal research reviews 2014, 34, 106–135. [CrossRef]

- Wigmore PM, Mustafa S, El-Beltagy M, Lyons L, Umka J, Bennett G: Effects of 5-FU. In: Chemo Fog: Cancer Chemotherapy-Related Cognitive Impairment. Springer; 2010: 157-164.

- Ioele G, Chieffallo M, Occhiuzzi MA, De Luca M, Garofalo A, Ragno G, Grande F: Anticancer drugs: recent strategies to improve stability profile, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Molecules 2022, 27, 5436. [CrossRef]

- Feyzizadeh M, Barfar A, Nouri Z, Sarfraz M, Zakeri-Milani P, Valizadeh H: Overcoming multidrug resistance through targeting ABC transporters: Lessons for drug discovery. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2022, 17, 1013–1027. [CrossRef]

- Naeem A, Hu P, Yang M, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhu W, Zheng Q: Natural products as anticancer agents: current status and future perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 8367. [CrossRef]

- Talib WH, Awajan D, Hamed RA, Azzam AO, Mahmod AI, Al-Yasari IH: Combination anticancer therapies using selected phytochemicals. Molecules 2022, 27, 5452. [CrossRef]

- Steward W, Brown K: Cancer chemoprevention: a rapidly evolving field. British journal of cancer 2013, 109, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Swetha M, Keerthana C, Rayginia TP, Anto RJ: Cancer chemoprevention: A strategic approach using phytochemicals. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2022; 12, 809308.

- Olayiwola Y, Gollahon L: Natural Compounds and Breast Cancer: Chemo-Preventive and Therapeutic Capabilities of Chlorogenic Acid and Cinnamaldehyde. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 361. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Kong A-NT: Dietary cancer-chemopreventive compounds: from signaling and gene expression to pharmacological effects. Trends in pharmacological sciences 2005, 26, 318–326. [CrossRef]

- Mocanu M-M, Nagy P, Szöllősi J: Chemoprevention of breast cancer by dietary polyphenols. Molecules 2015, 20, 22578–22620. [CrossRef]

- Hussain SS, Kumar AP, Ghosh R: Food-based natural products for cancer management: Is the whole greater than the sum of the parts? In: Seminars in cancer biology: 2016. Elsevier: 233-246.

- Orlikova B, Dicato M, Diederich M: 1,000 Ways to die: natural compounds modulate non-canonical cell death pathways in cancer cells. Phytochemistry reviews, 2014; 13, 277–293.

- Israel BeB, Tilghman SL, Parker-Lemieux K, Payton-Stewart F: Phytochemicals: Current strategies for treating breast cancer. Oncology letters 2018, 15, 7471–7478.

- Tao J, Diao L, Chen F, Shen A, Wang S, Jin H, Cai D, Hu Y: pH-sensitive nanoparticles codelivering docetaxel and dihydroartemisinin effectively treat breast cancer by enhancing reactive oxidative species-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2020, 18, 74–86.

- Weng J-R, Bai L-Y, Chiu C-F, Hu J-L, Chiu S-J, Wu C-Y: Cucurbitane Triterpenoid from Momordica charantia Induces Apoptosis and Autophagy in Breast Cancer Cells, in Part, through Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Activation. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013, 2013, 935675.

- Xu W-S, Li T, Wu G-S, Dang Y-Y, Hao W-H, Chen X-P, Lu J-J, Wang Y-T: Effects of furanodiene on 95-D lung cancer cells: apoptosis, autophagy and G1 phase cell cycle arrest. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2014, 42, 243–255. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Wang X, Cao S, Sun Y, He X, Jiang B, Yu Y, Duan J, Qiu F, Kang N: Berberine represses human gastric cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo by inducing cytostatic autophagy via inhibition of MAPK/mTOR/p70S6K and Akt signaling pathways. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2020; 128, 110245.

- Davoodvandi A, Sadeghi S, Alavi SMA, Alavi SS, Jafari A, Khan H, Aschner M, Mirzaei H, Sharifi M, Asemi Z: The therapeutic effects of berberine for gastrointestinal cancers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024, 20, 152–167. [CrossRef]

- Eguchi H, Kimura R, Onuma S, Ito A, Yu Y, Yoshino Y, Matsunaga T, Endo S, Ikari A: Elevation of anticancer drug toxicity by caffeine in spheroid model of human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells mediated by reduction in claudin-2 and Nrf2 expression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 15447. [CrossRef]

- Wang A, Wang W, Chen Y, Ma F, Wei X, Bi Y: Deguelin induces PUMA-mediated apoptosis and promotes sensitivity of lung cancer cells (LCCs) to doxorubicin (Dox). Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2018, 442, 177–186. [CrossRef]

- Swain SS, Sahoo SK: Piperlongumine and its derivatives against cancer: A recent update and future prospective. Archiv der Pharmazie, 2024; e2300768.

- Singh P, Sahoo SK: Piperlongumine loaded PLGA nanoparticles inhibit cancer stem-like cells through modulation of STAT3 in mammosphere model of triple negative breast cancer. International journal of pharmaceutics, 2022; 616, 121526.

- Singh D, Mohapatra P, Kumar S, Behera S, Dixit A, Sahoo SK: Nimbolide-encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles induces mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition by dual inhibition of AKT and mTOR in pancreatic cancer stem cells. Toxicology in Vitro, 2022; 79, 105293.

- Wang F, Mao Y, You Q, Hua D, Cai D: Piperlongumine induces apoptosis and autophagy in human lung cancer cells through inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology 2015, 28, 362–373. [CrossRef]

- Thongsom S, Suginta W, Lee KJ, Choe H, Talabnin C: Piperlongumine induces G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cells through the ROS-JNK-ERK signaling pathway. Apoptosis, 2017; 22, 1473–1484.

- Rawat L, Hegde H, Hoti SL, Nayak V: Piperlongumine induces ROS mediated cell death and synergizes paclitaxel in human intestinal cancer cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2020; 128, 110243.

- Tripathi SK, Biswal BK: Piperlongumine, a potent anticancer phytotherapeutic: Perspectives on contemporary status and future possibilities as an anticancer agent. Pharmacological Research, 2020; 156, 104772.

- Kung F-P, Lim Y-P, Chao W-Y, Zhang Y-S, Yu H-I, Tai T-S, Lu C-H, Chen S-H, Li Y-Z, Zhao P-W: Piperlongumine, a potent anticancer phytotherapeutic, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo through the ROS/Akt pathway in human thyroid cancer cells. Cancers 2021, 13, 4266.

- Pan X, Chen G, Hu W: Piperlongumine increases the sensitivity of bladder cancer to cisplatin by mitochondrial ROS. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis 2022, 36, e24452. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Sun S, Xu W, Zhang Y, Yang R, Ma K, Zhang J, Xu J: Piperlongumine inhibits thioredoxin reductase 1 by targeting selenocysteine residues and sensitizes cancer cells to erastin. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 710. [CrossRef]

- Chu Y, Tian Z, Yang M, Li W: Conformation and energy investigation of microtubule longitudinal dynamic instability induced by natural products. Chemical Biology & Drug Design 2023, 102, 444–456.

- Risinger AL, Du L: Targeting and extending the eukaryotic druggable genome with natural products: Cytoskeletal targets of natural products. Natural product reports 2020, 37, 634–652. [CrossRef]

- Dhyani P, Quispe C, Sharma E, Bahukhandi A, Sati P, Attri DC, Szopa A, Sharifi-Rad J, Docea AO, Mardare I: Anticancer potential of alkaloids: a key emphasis to colchicine, vinblastine, vincristine, vindesine, vinorelbine and vincamine. Cancer cell international 2022, 22, 206. [CrossRef]

- Au TH, Nguyen BN, Nguyen PH, Pethe S, Vo-Thanh G, Vu Thi TH: Vinblastine loaded on graphene quantum dots and its anticancer applications. Journal of microencapsulation 2022, 39, 239–251. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, An J, Shao Y, Yu N, Yue S, Sun H, Zhang J, Gu W, Xia Y, Zhang J et al: CD38-Directed Vincristine Nanotherapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 377–387. [CrossRef]

- Atal C, Dubey RK, Singh J: Biochemical basis of enhanced drug bioavailability by piperine: evidence that piperine is a potent inhibitor of drug metabolism. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 1985, 232, 258–262.

- Yaffe PB, Power Coombs MR, Doucette CD, Walsh M, Hoskin DW: Piperine, an alkaloid from black pepper, inhibits growth of human colon cancer cells via G1 arrest and apoptosis triggered by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecular carcinogenesis 2015, 54, 1070–1085. [CrossRef]

- Yang Q, Li F, Jia G, Liu R: Aged black garlic extract inhibits the growth of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells by downregulating MCL-1 expression through the ROS-JNK pathway. Plos one 2023, 18, e0286454.

- Stępień AE, Trojniak J, Tabarkiewicz J: Anti-Cancer and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Black Garlic. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 1801. [CrossRef]

- Park C, Park S, Chung YH, Kim G-Y, Choi YW, Kim BW, Choi YH: Induction of apoptosis by a hexane extract of aged black garlic in the human leukemic U937 cells. Nutrition Research and Practice 2014, 8, 132. [CrossRef]

- Dong M, Yang G, Liu H, Liu X, Lin S, Sun D, Wang Y: Aged black garlic extract inhibits HT29 colon cancer cell growth via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Biomedical Reports 2014, 2, 250–254. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Li HY, Zhang ZH, Bian HL, Lin G: Garlic-derived compound S-allylmercaptocysteine inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis via the JNK and p38 pathways in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Oncology letters 2014, 8, 2591–2596. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang A, Cao S-Y, Xu X-Y, Gan R-Y, Tang G-Y, Corke H, Mavumengwana V, Li H-B: Bioactive compounds and biological functions of garlic (Allium sativum L.). Foods 2019, 8, 246.

- Bagul M, Kakumanu S, Wilson TA: Crude garlic extract inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of cancer cells in vitro. Journal of medicinal food 2015, 18, 731–737. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledano Medina MÁ, Merinas-Amo T, Fernández-Bedmar Z, Font R, del Río-Celestino M, Pérez-Aparicio J, Moreno-Ortega A, Alonso-Moraga Á, Moreno-Rojas R: Physicochemical characterization and biological activities of black and white garlic: In vivo and in vitro assays. Foods 2019, 8, 220.

- Wang X, Jiao F, Wang Q-W, Wang J, Yang K, Hu R-R, Liu H-C, Wang H-Y, Wang Y-S: Aged black garlic extract induces inhibition of gastric cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Molecular Medicine Reports 2012, 5, 66–72.

- Castro NP, Rangel MC, Merchant AS, MacKinnon G, Cuttitta F, Salomon DS, Kim YS: Sulforaphane suppresses the growth of triple-negative breast cancer stem-like cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Prevention Research 2019, 12, 147–158. [CrossRef]

- Na G, He C, Zhang S, Tian S, Bao Y, Shan Y: Dietary isothiocyanates: Novel insights into the potential for cancer prevention and therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 1962. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Zhang T, Korkaya H, Liu S, Lee H-F, Newman B, Yu Y, Clouthier SG, Schwartz SJ, Wicha MS: Sulforaphane, a dietary component of broccoli/broccoli sprouts, inhibits breast cancer stem cells. Clinical Cancer Research 2010, 16, 2580–2590. [CrossRef]

- Jeon YK, Yoo DR, Jang YH, Jang SY, Nam MJ: Sulforaphane induces apoptosis in human hepatic cancer cells through inhibition of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2, 6-biphosphatase4, mediated by hypoxia inducible factor-1-dependent pathway. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics 2011, 1814, 1340–1348. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan JI, Salm N, Wallace AJ, Hampton MB: Using food to reduce H. pylori-associated inflammation. Phytotherapy Research 2012, 26, 1620–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He C, Huang L, Lei P, Liu X, Li B, Shan Y: Sulforaphane normalizes intestinal flora and enhances gut barrier in mice with BBN-induced bladder cancer. Molecular nutrition & food research 2018, 62, 1800427.

- Singh KB, Hahm E-R, Alumkal JJ, Foley LM, Hitchens TK, Shiva SS, Parikh RA, Jacobs BL, Singh SV: Reversal of the Warburg phenomenon in chemoprevention of prostate cancer by sulforaphane. Carcinogenesis 2019, 40, 1545–1556. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan Y, Zhou Y, Li J, Zheng Z, Hu Y, Li L, Wu W: Sulforaphane downregulated fatty acid synthase and inhibited microtubule-mediated mitophagy leading to apoptosis. Cell Death & Disease 2021, 12, 917.

- Li S-H, Fu J, Watkins DN, Srivastava RK, Shankar S: Sulforaphane regulates self-renewal of pancreatic cancer stem cells through the modulation of Sonic hedgehog–GLI pathway. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2013, 373:217-227.

- Kumar R, de Mooij T, Peterson T, Johnson A, Daniels DJ, Parney IF: Modulating glioma-mediated myeloid-derived suppressor cell development with sulforaphane. In: NEURO-ONCOLOGY: 2016. OXFORD UNIV PRESS INC JOURNALS DEPT, 2001 EVANS RD, CARY, NC 27513 USA: 99-100.

- Rai R, Gong Essel K, Mangiaracina Benbrook D, Garland J, Daniel Zhao Y, Chandra V: Preclinical efficacy and involvement of AKT, mTOR, and ERK kinases in the mechanism of sulforaphane against endometrial cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 1273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao Y, Wang W, Zhou Z, Sun C: Benefits and risks of the hormetic effects of dietary isothiocyanates on cancer prevention. PLoS One 2014, 9, e114764.

- Rao J, Xu D-R, Zheng F-M, Long Z-J, Huang S-S, Wu X, Zhou W-H, Huang R-W, Liu Q: Curcumin reduces expression of Bcl-2, leading to apoptosis in daunorubicin-insensitive CD34+ acute myeloid leukemia cell lines and primary sorted CD34+ acute myeloid leukemia cells. Journal of translational medicine, 2011; 9, 1–15.

- Cao A, Li Q, Yin P, Dong Y, Shi H, Wang L, Ji G, Xie J, Wu D: Curcumin induces apoptosis in human gastric carcinoma AGS cells and colon carcinoma HT-29 cells through mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Apoptosis, 2013; 18, 1391–1402.

- Liu E, Wu J, Cao W, Zhang J, Liu W, Jiang X, Zhang X: Curcumin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in a p53-dependent manner and upregulates ING4 expression in human glioma. Journal of neuro-oncology, 2007; 85, 263–270.

- Mousavi SM, Hosseindoost S, Mahdian SMA, Vousooghi N, Rajabi A, Jafari A, Ostadian A, Hamblin MR, Hadjighassem M, Mirzaei H: Exosomes released from U87 glioma cells treated with curcumin and/or temozolomide produce apoptosis in naive U87 cells. Pathology-Research and Practice, 2023; 245, 154427.

- Mukherjee S, Mazumdar M, Chakraborty S, Manna A, Saha S, Khan P, Bhattacharjee P, Guha D, Adhikary A, Mukhjerjee S: Curcumin inhibits breast cancer stem cell migration by amplifying the E-cadherin/β-catenin negative feedback loop. Stem cell research & therapy, 2014; 5, 1–19.

- Borges GA, Elias ST, Amorim B, de Lima CL, Coletta RD, Castilho RM, Squarize CH, Guerra ENS: Curcumin downregulates the PI3K–AKT–mTOR pathway and inhibits growth and progression in head and neck cancer cells. Phytotherapy research 2020, 34, 3311–3324. [CrossRef]

- Shamsnia HS, Roustaei M, Ahmadvand D, Butler AE, Amirlou D, Soltani S, Momtaz S, Jamialahmadi T, Abdolghaffari AH, Sahebkar A: Impact of curcumin on p38 MAPK: Therapeutic implications. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 2201–2212. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almatroodi SA, Almatroudi A, Khan AA, Alhumaydhi FA, Alsahli MA, Rahmani AH: Potential therapeutic targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), the most abundant catechin in green tea, and its role in the therapy of various types of cancer. Molecules 2020, 25, 3146. [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa S, Ohishi T, Miyoshi N, Oishi Y, Nakamura Y, Isemura M: Anti-cancer effects of green tea epigallocatchin-3-gallate and coffee chlorogenic acid. Molecules 2020, 25, 4553. [CrossRef]

- Gu J-W, Makey KL, Tucker KB, Chinchar E, Mao X, Pei I, Thomas EY, Miele L: EGCG, a major green tea catechin suppresses breast tumor angiogenesis and growth via inhibiting the activation of HIF-1α and NFκB, and VEGF expression. Vascular cell, 2013; 5, 1–10.

- Sen T, Chatterjee A: Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) downregulates EGF-induced MMP-9 in breast cancer cells: involvement of integrin receptor α5β1 in the process. European journal of nutrition, 2011; 50, 465–478.

- Wei R, Cortez Penso NE, Hackman RM, Wang Y, Mackenzie GG: Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) suppresses pancreatic cancer cell growth, invasion, and migration partly through the inhibition of Akt pathway and epithelial–mesenchymal transition: Enhanced efficacy when combined with gemcitabine. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1856.

- Van Aller GS, Carson JD, Tang W, Peng H, Zhao L, Copeland RA, Tummino PJ, Luo L: Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a major component of green tea, is a dual phosphoinositide-3-kinase/mTOR inhibitor. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2011, 406, 194–199. [CrossRef]

- Ko E-B, Jang Y-G, Kim C-W, Go R-E, Lee HK, Choi K-C: Gallic acid hindered lung cancer progression by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in a549 lung cancer cells via PI3K/Akt pathway. Biomolecules & Therapeutics 2022, 30, 151.

- Zhang Y, Ren X, Shi M, Jiang Z, Wang H, Su Q, Liu Q, Li G, Jiang G: Downregulation of STAT3 and activation of MAPK are involved in the induction of apoptosis by HNK in glioblastoma cell line U87. Oncology reports 2014, 32, 2038–2046. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moral R, Escrich E: Influence of olive oil and its components on breast cancer: Molecular mechanisms. Molecules 2022, 27, 477. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Pu R, Zhou L, Wang D, Li X: Effects of a Chlorogenic Acid-Containing Herbal Medicine (LASNB) on Colon Cancer. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2021, 2021, 9923467.

- Lu H, Tian Z, Cui Y, Liu Z, Ma X: Chlorogenic acid: A comprehensive review of the dietary sources, processing effects, bioavailability, beneficial properties, mechanisms of action, and future directions. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety 2020, 19, 3130–3158. [CrossRef]

- Kim TW: Cinnamaldehyde induces autophagy-mediated cell death through ER stress and epigenetic modification in gastric cancer cells. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2022, 43, 712–723. [CrossRef]

- Mei J, Ma J, Xu Y, Wang Y, Hu M, Ma F, Qin Z, Xue R, Tao N: Cinnamaldehyde treatment of prostate cancer-associated fibroblasts prevents their inhibitory effect on T cells through toll-like receptor 4. Drug design, development and therapy, 2020; 3363–3372.

- Kueck A, Opipari Jr AW, Griffith KA, Tan L, Choi M, Huang J, Wahl H, Liu JR: Resveratrol inhibits glucose metabolism in human ovarian cancer cells. Gynecologic oncology 2007, 107, 450–457. [CrossRef]

- Fu Y, Chang H, Peng X, Bai Q, Yi L, Zhou Y, Zhu J, Mi M: Resveratrol inhibits breast cancer stem-like cells and induces autophagy via suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. PloS one 2014, 9, e102535.

- Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CW, Fong HH, Farnsworth NR, Kinghorn AD, Mehta RG: Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. science 1997, 275, 218–220. [CrossRef]

- Baek SH, Ko J-H, Lee H, Jung J, Kong M, Lee J-w, Lee J, Chinnathambi A, Zayed M, Alharbi SA: Resveratrol inhibits STAT3 signaling pathway through the induction of SOCS-1: Role in apoptosis induction and radiosensitization in head and neck tumor cells. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 566–577. [CrossRef]

- Harikumar KB, Kunnumakkara AB, Sethi G, Diagaradjane P, Anand P, Pandey MK, Gelovani J, Krishnan S, Guha S, Aggarwal BB: Resveratrol, a multitargeted agent, can enhance antitumor activity of gemcitabine in vitro and in orthotopic mouse model of human pancreatic cancer. International journal of cancer 2010, 127, 257–268.

- Carter LG, D'Orazio JA, Pearson KJ: Resveratrol and cancer: focus on in vivo evidence. Endocrine-related cancer 2014, 21, R209–R225. [CrossRef]

- Yousef M, Vlachogiannis IA, Tsiani E: Effects of resveratrol against lung cancer: In vitro and in vivo studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhami VM, Afaq F, Ahmad N: Suppression of ultraviolet B exposure-mediated activation of NF-κB in normal human keratinocytes by resveratrol. Neoplasia 2003, 5, 74–82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza JL, Kurokawa Y, Takami A: Rationale for assessing the therapeutic potential of resveratrol in hematological malignancies. Blood Reviews, 2019; 33, 43–52.

- Ren B, Kwah MX-Y, Liu C, Ma Z, Shanmugam MK, Ding L, Xiang X, Ho PC-L, Wang L, Ong PS: Resveratrol for cancer therapy: Challenges and future perspectives. Cancer letters, 2021; 515, 63–72.

- Seong Y-A, Shin P-G, Yoon J-S, Yadunandam AK, Kim G-D: Induction of the endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy in human lung carcinoma A549 cells by anacardic acid. Cell biochemistry and biophysics, 2014; 68, 369–377.

- Li Y, Zhou Y, Wang M, Lin X, Zhang Y, Laurent I, Zhong Y, Li J: Ampelopsin inhibits breast cancer cell growth through mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2021, 44, 1738–1745. [CrossRef]

- Lu H-F, Chie Y-J, Yang M-S, Lee C-S, Fu J-J, Yang J-S, Tan T-W, Wu S-H, Ma Y-S, Ip S-W: Apigenin induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in human lung cancer A549 cells through Bax-and Bcl-2-triggered mitochondrial pathway. International journal of oncology 2010, 36, 1477–1484.

- Tsai M-H, Liu J-F, Chiang Y-C, Hu SC-S, Hsu L-F, Lin Y-C, Lin Z-C, Lee H-C, Chen M-C, Huang C-L: Correction: Artocarpin, an isoprenyl flavonoid, induces p53-dependent or independent apoptosis via ROS-mediated MAPKs and Akt activation in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 3430.

- Park S-A, Seo YJ, Kim LK, Kim HJ, Yoon KD, Heo T-H: Butein Inhibits Cell Growth by Blocking the IL-6/IL-6Rα Interaction in Human Ovarian Cancer and by Regulation of the IL-6/STAT3/FoxO3a Pathway. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 6038. [CrossRef]

- Khoo BY, Chua SL, Balaram P: Apoptotic effects of chrysin in human cancer cell lines. International journal of molecular sciences 2010, 11, 2188–2199. [CrossRef]

- Samarghandian S, Azimi Nezhad M, Mohammadi G: Role of caspases, Bax and Bcl-2 in chrysin-induced apoptosis in the A549 human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents) 2014, 14, 901–909.

- Zhang Z, Pan Y, Zhao Y, Ren M, Li Y, Lu G, Wu K, He S: Delphinidin modulates JAK/STAT3 and MAPKinase signaling to induce apoptosis in HCT116 cells. Environmental Toxicology 2021, 36, 1557–1566. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gossner G, Choi M, Tan L, Fogoros S, Griffith KA, Kuenker M, Liu JR: Genistein-induced apoptosis and autophagocytosis in ovarian cancer cells. Gynecologic oncology 2007, 105, 23–30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicosia SV, Bai W, Cheng JQ, Coppola D, Kruk PA: Oncogenic pathways implicated in ovarian epithelial cancer. Hematology/Oncology Clinics 2003, 17, 927–943. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi H, Gupta DS, Abjani NK, Kaur G, Mohan CD, Kaur J, Aggarwal D, Rani I, Ramniwas S, Abdulabbas HS: Genistein: a promising modulator of apoptosis and survival signaling in cancer. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology 2023, 396, 2893–2910. [CrossRef]

- Obinu A, Burrai GP, Cavalli R, Galleri G, Migheli R, Antuofermo E, Rassu G, Gavini E, Giunchedi P: Transmucosal solid lipid nanoparticles to improve genistein absorption via intestinal lymphatic transport. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 267. [CrossRef]

- Křížová L, Dadáková K, Kašparovská J, Kašparovský T: Isoflavones. Molecules 2019, 24, 1076. [CrossRef]

- Kim I-S: Current perspectives on the beneficial effects of soybean isoflavones and their metabolites for humans. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1064. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu R, Yu X, Chen X, Zhong H, Liang C, Xu X, Xu W, Cheng Y, Wang W, Yu L: Individual factors define the overall effects of dietary genistein exposure on breast cancer patients. Nutrition research, 2019; 67, 1–16.

- Ma M, Luan X, Zheng H, Wang X, Wang S, Shen T, Ren D: A mulberry diels-alder-type adduct, Kuwanon M, triggers apoptosis and paraptosis of lung cancer cells through inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 1015. [CrossRef]

- Shu Y-h, Yuan H-h, Xu M-t, Hong Y-t, Gao C-c, Wu Z-p, Han H-t, Sun X, Gao R-l, Yang S-f: A novel Diels–Alder adduct of mulberry leaves exerts anticancer effect through autophagy-mediated cell death. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2021, 42, 780–790. [CrossRef]

- Wang K, Liu R, Li J, Mao J, Lei Y, Wu J, Zeng J, Zhang T, Wu H, Chen L: Quercetin induces protective autophagy in gastric cancer cells: involvement of Akt-mTOR-and hypoxia-induced factor 1α-mediated signaling. Autophagy 2011, 7, 966–978. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed HA, Sulaiman GM, Anwar SS, Tawfeeq AT, Khan RA, Mohammed SA, Al-Omar MS, Alsharidah M, Al Rugaie O, Al-Amiery AA: Quercetin against MCF7 and CAL51 breast cancer cell lines: apoptosis, gene expression and cytotoxicity of nano-quercetin. Nanomedicine 2021.

- Nakamura M, Urakawa D, He Z, Akagi I, Hou D-X, Sakao K: Apoptosis Induction in HepG2 and HCT116 Cells by a Novel Quercetin-Zinc (II) Complex: Enhanced Absorption of Quercetin and Zinc (II). International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 17457. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarahovsky YS, Kim YA, Yagolnik EA, Muzafarov EN: Flavonoid–membrane interactions: Involvement of flavonoid–metal complexes in raft signaling. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2014, 1838, 1235–1246. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang R, Yang L, Li S, Ye D, Yang L, Liu Q, Zhao Z, Cai Q, Tan J, Li X: Quercetin inhibits breast cancer stem cells via downregulation of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 (ALDH1A1), chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), mucin 1 (MUC1), and epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM). Medical Science Monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research, 2018; 24, 412.

- Liu Y, Wang Y, Sun S, Chen Z, Xiang S, Ding Z, Huang Z, Zhang B: Understanding the versatile roles and applications of EpCAM in cancers: from bench to bedside. Experimental hematology & oncology 2022, 11, 97.

- Binienda A, Ziolkowska S, Pluciennik E: The anticancer properties of silibinin: its molecular mechanism and therapeutic effect in breast cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents) 2020, 20, 1787–1796.

- Iqbal MA, Chattopadhyay S, Siddiqui FA, Ur Rehman A, Siddiqui S, Prakasam G, Khan A, Sultana S, Bamezai RN: Silibinin induces metabolic crisis in triple-negative breast cancer cells by modulating EGFR-MYC-TXNIP axis: potential therapeutic implications. The FEBS journal 2021, 288, 471–485. [CrossRef]

- Feng X-L, Ho SC, Mo X-F, Lin F-Y, Zhang N-Q, Luo H, Zhang X, Zhang C-X: Association between flavonoids, flavonoid subclasses intake and breast cancer risk: a case-control study in China. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2020, 29, 493–500. [CrossRef]

- Golonko A, Olichwier AJ, Swislocka R, Szczerbinski L, Lewandowski W: Why Do Dietary Flavonoids Have a Promising Effect as Enhancers of Anthracyclines? Hydroxyl Substituents, Bioavailability and Biological Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 24, 391. [CrossRef]

- Dhingra R, Margulets V, Kirshenbaum L: Chapter 2—Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity: Challenges in Cardio-Oncology. Cardio-Oncology; Gottlieb, RA, Mehta, PK, Eds; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017:25-34.

- Pons DG: Roles of Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention and Therapeutics. In., vol. 25: MDPI; 2024: 5450.

- Zhang YY, Zhang F, Zhang YS, Thakur K, Zhang JG, Liu Y, Kan H, Wei ZJ: Mechanism of Juglone-Induced Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Ishikawa Human Endometrial Cancer Cells. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2019, 67, 7378–7389. [CrossRef]

- Sun W, Bao J, Lin W, Gao H, Zhao W, Zhang Q, Leung C-H, Ma D-L, Lu J, Chen X: 2-Methoxy-6-acetyl-7-methyljuglone (MAM), a natural naphthoquinone, induces NO-dependent apoptosis and necroptosis by H2O2-dependent JNK activation in cancer cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2016; 92, 61–77.

- Ock CW, Kim GD: Dioscin decreases breast cancer stem-like cell proliferation via cell cycle arrest by modulating p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and AKT/mTOR signaling pathways. Journal of cancer prevention 2021, 26, 183. [CrossRef]

- Shah MA, Abuzar SM, Ilyas K, Qadees I, Bilal M, Yousaf R, Kassim RMT, Rasul A, Saleem U, Alves MS: Ginsenosides in cancer: Targeting cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Chemico-biological interactions, 2023; 110634.

- Aggarwal V, Tuli HS, Kaur J, Aggarwal D, Parashar G, Chaturvedi Parashar N, Kulkarni S, Kaur G, Sak K, Kumar M: Garcinol exhibits anti-neoplastic effects by targeting diverse oncogenic factors in tumor cells. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 103.

- Kamiya T, Nishihara H, Hara H, Adachi T: Ethanol extract of Brazilian red propolis induces apoptosis in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells through endoplasmic reticulum stress. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2012, 60, 11065–11070. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu S-C, Hsieh Y-S, Yu C-C, Lai Y-Y, Chen P-N: Thymoquinone induces cell death in human squamous carcinoma cells via caspase activation-dependent apoptosis and LC3-II activation-dependent autophagy. PloS one 2014, 9, e101579.

- Shanmugam MK, Ahn KS, Hsu A, Woo CC, Yuan Y, Tan KHB, Chinnathambi A, Alahmadi TA, Alharbi SA, Koh APF: Thymoquinone inhibits bone metastasis of breast cancer cells through abrogation of the CXCR4 signaling axis. Frontiers in pharmacology, 2018; 1294.

- Hu R, Zhou P, Peng Y-B, Xu X, Ma J, Liu Q, Zhang L, Wen X-D, Qi L-W, Gao N: 6-Shogaol induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and exhibits anti-tumor activity in vivo through endoplasmic reticulum stress. PloS one 2012, 7, e39664.

- Jiang Q, Rao X, Kim CY, Freiser H, Zhang Q, Jiang Z, Li G: Gamma-tocotrienol induces apoptosis and autophagy in prostate cancer cells by increasing intracellular dihydrosphingosine and dihydroceramide. International journal of cancer 2012, 130, 685–693. [CrossRef]

- Yang KM, Kim BM, Park J-B: ω-Hydroxyundec-9-enoic acid induces apoptosis through ROS-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2014, 448, 267–273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustynowicz D, Lemieszek MK, Strawa JW, Wiater A, Tomczyk M: Phytochemical profiling of extracts from rare Potentilla species and evaluation of their anticancer potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 4836. [CrossRef]

- Augustynowicz D, Lemieszek MK, Strawa JW, Wiater A, Tomczyk M: Anticancer potential of acetone extracts from selected Potentilla species against human colorectal cancer cells. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2022; 13, 1027315.

- Leitzmann C: Characteristics and health benefits of phytochemicals. Forschende Komplementärmedizin/Research in Complementary Medicine 2016, 23, 69–74.

- Li S, Tan HY, Wang N, Cheung F, Hong M, Feng Y: The potential and action mechanism of polyphenols in the treatment of liver diseases. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2018, 2018, 8394818. [CrossRef]

- Elekofehinti OO, Iwaloye O, Olawale F, Ariyo EO: Saponins in cancer treatment: Current progress and future prospects. Pathophysiology 2021, 28, 250–272. [CrossRef]

- Moran NE, Mohn ES, Hason N, Erdman Jr JW, Johnson EJ: Intrinsic and extrinsic factors impacting absorption, metabolism, and health effects of dietary carotenoids. Advances in Nutrition 2018, 9, 465–492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudzińska A, Juchaniuk P, Oberda J, Wiśniewska J, Wojdan W, Szklener K, Mańdziuk S: Phytochemicals in cancer treatment and cancer prevention—review on epidemiological data and clinical trials. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1896. [CrossRef]

- Khan UM, Sevindik M, Zarrabi A, Nami M, Ozdemir B, Kaplan DN, Selamoglu Z, Hasan M, Kumar M, Alshehri MM: Lycopene: Food sources, biological activities, and human health benefits. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2021, 2021, 2713511. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krinsky NI, Johnson EJ: Carotenoid actions and their relation to health and disease. Molecular aspects of medicine 2005, 26, 459–516. [CrossRef]

- Niranjana R, Gayathri R, Mol SN, Sugawara T, Hirata T, Miyashita K, Ganesan P: Carotenoids modulate the hallmarks of cancer cells. Journal of functional foods, 2015; 18, 968–985.

- Jomova K, Valko M: Health protective effects of carotenoids and their interactions with other biological antioxidants. European journal of medicinal chemistry, 2013; 70, 102–110.

- Rutz JK, Borges CD, Zambiazi RC, da Rosa CG, da Silva MM: Elaboration of microparticles of carotenoids from natural and synthetic sources for applications in food. Food chemistry, 2016; 202, 324–333.

- Tapiero H, Townsend DM, Tew KD: The role of carotenoids in the prevention of human pathologies. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2004, 58, 100–110.

- Yang D-J, Lin J-T, Chen Y-C, Liu S-C, Lu F-J, Chang T-J, Wang M, Lin H-W, Chang Y-Y: Suppressive effect of carotenoid extract of Dunaliella salina alga on production of LPS-stimulated pro-inflammatory mediators in RAW264. 7 cells via NF-κB and JNK inactivation. Journal of Functional Foods 2013, 5, 607–615. [Google Scholar]

- Amin A, Hamza AA, Bajbouj K, Ashraf SS, Daoud S: Saffron: a potential candidate for a novel anticancer drug against hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2011, 54, 857–867. [CrossRef]

- Zou G, Zhang X, Wang L, Li X, Xie T, Zhao J, Yan J, Wang L, Ye H, Jiao S: Herb-sourced emodin inhibits angiogenesis of breast cancer by targeting VEGFA transcription. Theranostics 2020, 10, 6839. [CrossRef]

- Fu M, Tang W, Liu J-J, Gong X-Q, Kong L, Yao X-M, Jing M, Cai F-Y, Li X-T, Ju R-J: Combination of targeted daunorubicin liposomes and targeted emodin liposomes for treatment of invasive breast cancer. Journal of drug targeting 2020, 28, 245–258. [CrossRef]

- Shen Z, Zhao L, Yoo S-a, Lin Z, Zhang Y, Yang W, Piao J: Emodin induces ferroptosis in colorectal cancer through NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy and NF-κb pathway inactivation. Apoptosis, 2024; 1–14.

- Shi M, Chen Z, Gong H, Peng Z, Sun Q, Luo K, Wu B, Wen C, Lin W: Luteolin, a flavone ingredient: Anticancer mechanisms, combined medication strategy, pharmacokinetics, clinical trials, and pharmaceutical researches. Phytotherapy Research 2024, 38, 880–911. [CrossRef]

- Gu X, Peng Y, Zhao Y, Liang X, Tang Y, Liu J: A novel derivative of artemisinin inhibits cell proliferation and metastasis via down-regulation of cathepsin K in breast cancer. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2019; 858, 172382.

- Tong X, Chen L, He S-j, Zuo J-p: Artemisinin derivative SM934 in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases: therapeutic effects and molecular mechanisms. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2022, 43, 3055–3061. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holdhoff M, Nicholas MK, Peterson RA, Maraka S, Liu LC, Fischer JH, Wefel JS, Fan TM, Vannorsdall T, Russell M et al: Phase I dose-escalation study of procaspase-activating compound-1 in combination with temozolomide in patients with recurrent high-grade astrocytomas. Neuro-oncology advances 2023, 5, vdad087.

- Sminia P, van den Berg J, van Kootwijk A, Hageman E, Slotman BJ, Verbakel W: Experimental and clinical studies on radiation and curcumin in human glioma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2021, 147, 403–409. [CrossRef]

- Medical University of South C: Phase I Assay-guided Trial of Anti-inflammatory Phytochemicals in Patients With Advanced Cancer. clinicaltrialsgov 2013.

- Paur I, Lilleby W, Bøhn SK, Hulander E, Klein W, Vlatkovic L, Axcrona K, Bolstad N, Bjøro T, Laake P: Tomato-based randomized controlled trial in prostate cancer patients: Effect on PSA. Clinical Nutrition 2017, 36, 672–679. [CrossRef]

- https://clinicaltrials.gov, 2024.

- Hamblin MR: Shining light on the head: photobiomodulation for brain disorders. BBA clinical, 2016; 6, 113–124.

- Zhen X, Cheng P, Pu K: Recent advances in cell membrane–camouflaged nanoparticles for cancer phototherapy. Small 2019, 15, 1804105. [CrossRef]

- Pivetta TP, Botteon CE, Ribeiro PA, Marcato PD, Raposo M: Nanoparticle systems for cancer phototherapy: An overview. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3132. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He Z, Zhao L, Zhang Q, Chang M, Li C, Zhang H, Lu Y, Chen Y: An acceptor–donor–acceptor structured small molecule for effective NIR triggered dual phototherapy of cancer. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 30, 1910301. [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Yang W, Shi L, Zhang H, Xu Y, Wang P, Zhang G, Chen WR, Zhang B, Wang X: Concurrent photothermal therapy and photodynamic therapy for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma by gold nanoclusters under a single NIR laser irradiation. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2019, 7, 6924–6933. [CrossRef]

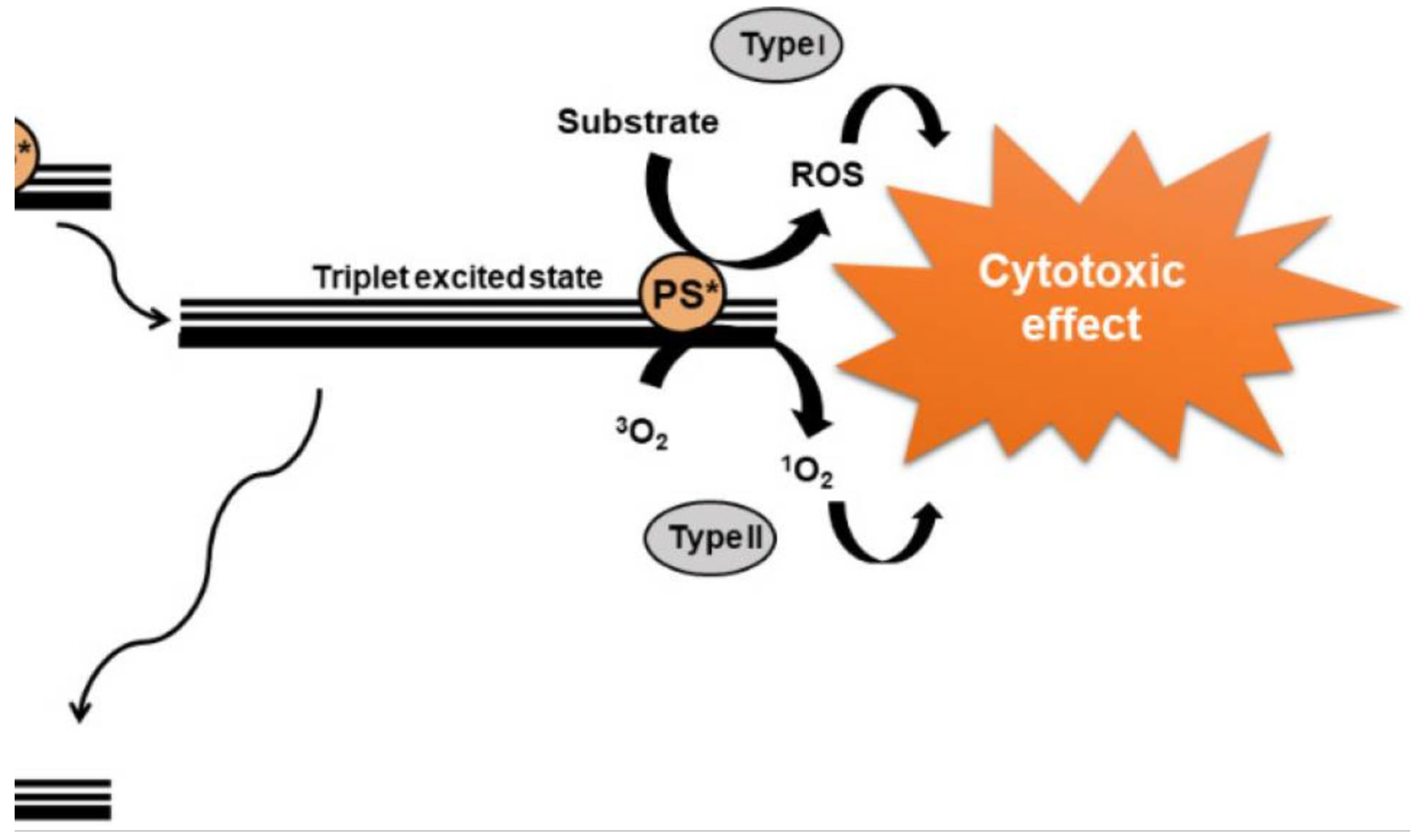

- Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, Hahn SM, Hamblin MR, Juzeniene A, Kessel D: Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2011, 61, 250–281.

- Oniszczuk A, Wojtunik-Kulesza KA, Oniszczuk T, Kasprzak K: The potential of photodynamic therapy (PDT)—Experimental investigations and clinical use. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy.

- Kim M, Jung HY, Park HJ: Topical PDT in the treatment of benign skin diseases: principles and new applications. International journal of molecular sciences 2015, 16, 23259–23278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen X, Li Y, Hamblin MR: Photodynamic therapy in dermatology beyond non-melanoma cancer: An update. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy, 2017; 19, 140–152.

- Ailioaie LM, Litscher G: Curcumin and photobiomodulation in chronic viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 7150. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang S, Zhu R, He X, Wang J, Wang M, Qian Y, Wang S: Enhanced photocytotoxicity of curcumin delivered by solid lipid nanoparticles. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 2017; 167–178.

- Machado FC, de Matos RPA, Primo FL, Tedesco AC, Rahal P, Calmon MF: Effect of curcumin-nanoemulsion associated with photodynamic therapy in breast adenocarcinoma cell line. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 27, 1882–1890.

- Monge-Fuentes V, Muehlmann LA, Longo JPF, Silva JR, Fascineli ML, de Souza P, Faria F, Degterev IA, Rodriguez A, Carneiro FP: Photodynamic therapy mediated by acai oil (Euterpe oleracea Martius) in nanoemulsion: A potential treatment for melanoma. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 2017; 166, 301–310.

- Semeraro P, Chimienti G, Altamura E, Fini P, Rizzi V, Cosma P: Chlorophyll a in cyclodextrin supramolecular complexes as a natural photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy (PDT) applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2018; 85, 47–56.

- Wang K, Xiang Y, Pan W, Wang H, Li N, Tang B: Dual-targeted photothermal agents for enhanced cancer therapy. Chemical science 2020, 11, 8055–8072. [CrossRef]

- Abadeer NS, Murphy CJ: Recent progress in cancer thermal therapy using gold nanoparticles. Nanomaterials and Neoplasms, 2021; 143–217.

- Zou L, Wang H, He B, Zeng L, Tan T, Cao H, He X, Zhang Z, Guo S, Li Y: Current approaches of photothermal therapy in treating cancer metastasis with nanotherapeutics. Theranostics 2016, 6, 762. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Wu X, Shen P, Wang J, Shen Y, Shen Y, Webster TJ, Deng J: Applications of inorganic nanomaterials in photothermal therapy based on combinational cancer treatment. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 2020; 1903–1914.

- Fernandes N, Rodrigues CF, Moreira AF, Correia IJ: Overview of the application of inorganic nanomaterials in cancer photothermal therapy. Biomaterials science 2020, 8, 2990–3020. [CrossRef]

- Tafech A, Stéphanou A: On the importance of acidity in cancer cells and therapy. Biology 2024, 13, 225.

- Mendes R, Pedrosa P, Lima JC, Fernandes AR, Baptista PV: Photothermal enhancement of chemotherapy in breast cancer by visible irradiation of Gold Nanoparticles. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 10872.

- Li H, Zhang N, Hao Y, Wang Y, Jia S, Zhang H: Enhancement of curcumin antitumor efficacy and further photothermal ablation of tumor growth by single-walled carbon nanotubes delivery system in vivo. Drug delivery 2019, 26, 1017–1026. [CrossRef]

- Bano S, Nazir S, Nazir A, Munir S, Mahmood T, Afzal M, Ansari FL, Mazhar K: Microwave-assisted green synthesis of superparamagnetic nanoparticles using fruit peel extracts: surface engineering, T 2 relaxometry, and photodynamic treatment potential. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 2016; 3833–3848.

- Kharey P, Dutta SB, Manikandan M, Palani I, Majumder S, Gupta S: Green synthesis of near-infrared absorbing eugenate capped iron oxide nanoparticles for photothermal application. Nanotechnology 2019, 31, 095705.

- Ashkbar A, Rezaei F, Attari F, Ashkevarian S: Treatment of breast cancer in vivo by dual photodynamic and photothermal approaches with the aid of curcumin photosensitizer and magnetic nanoparticles. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 21206.

- Mun ST, Bae DH, Ahn WS: Epigallocatechin gallate with photodynamic therapy enhances anti-tumor effects in vivo and in vitro. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy 2014, 11, 141–147. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao Y, Zhang L, Shen J, Ma L, Wang L: Effects of Nutrients/Nutrition on Toxicants/Toxicity. In: Nutritional Toxicology. Springer; 2022: 1-28.

- Duda-Chodak A, Tarko T: Possible side effects of polyphenols and their interactions with medicines. Molecules 2023, 28, 2536. [CrossRef]

- Alwhaibi AM, Alshamrani AA, Alenazi MA, Altwalah SF, Alameel NN, Aljabali NN, Alghamdi SB, Bineid AI, Alwhaibi M, Al Arifi MN: Vincristine-induced neuropathy in patients diagnosed with solid and hematological malignancies: the role of dose rounding. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 5662. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen ML, Due H, Ejskjær N, Jensen P, Madsen J, Dybkær K: Aspects of vincristine-induced neuropathy in hematologic malignancies: a systematic review. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology, 2019; 84, 471–485.

- Tang Z, Zhang Q: The potential toxic side effects of flavonoids. Biocell 2022, 46, 357.

- Bode AM, Dong Z: Toxic phytochemicals and their potential risks for human cancer. Cancer prevention research 2015, 8, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Laqueur G, Spatz M: Toxicology of cycasin. Cancer Research 1968, 28, 2262–2267.

- Kisby GE, Fry RC, Lasarev MR, Bammler TK, Beyer RP, Churchwell M, Doerge DR, Meira LB, Palmer VS, Ramos-Crawford A-L: The cycad genotoxin MAM modulates brain cellular pathways involved in neurodegenerative disease and cancer in a DNA damage-linked manner. PLoS One 2011, 6, e20911.

- Niemeyer HB, Honig DM, Kulling SE, Metzler M: Studies on the metabolism of the plant lignans secoisolariciresinol and matairesinol. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2003, 51, 6317–6325. [CrossRef]

- Ward HA, Kuhnle GG, Mulligan AA, Lentjes MA, Luben RN, Khaw K-T: Breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition–Norfolk in relation to phytoestrogen intake derived from an improved database. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2010, 91, 440–448. [CrossRef]

- van Duursen MB, Nijmeijer S, De Morree E, de Jong PC, van den Berg M: Genistein induces breast cancer-associated aromatase and stimulates estrogen-dependent tumor cell growth in in vitro breast cancer model. Toxicology 2011, 289(2-3):67-73.

- Ju YH, Doerge DR, Woodling KA, Hartman JA, Kwak J, Helferich WG: Dietary genistein negates the inhibitory effect of letrozole on the growth of aromatase-expressing estrogen-dependent human breast cancer cells (MCF-7Ca) in vivo. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 2162–2168. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang H, Cifone M, Murli H, Erexson G, Mecchi M, Lawlor T: Application of simplified in vitro screening tests to detect genotoxicity of aristolochic acid. Food and chemical toxicology 2004, 42, 2021–2028. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlt VM, Stiborova M, Schmeiser HH: Aristolochic acid as a probable human cancer hazard in herbal remedies: a review. Mutagenesis 2002, 17, 265–277. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han ZT, Tong YK, He LM, Zhang Y, Sun JZ, Wang TY, Zhang H, Cui YL, Newmark HL, Conney AH: 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced increase in depressed white blood cell counts in patients treated with cytotoxic cancer chemotherapeutic drugs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 5362–5365. [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi E, Ahlgren J, Bergelin N, Törnquist K: Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate inhibits FRO anaplastic human thyroid cancer cell proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest in G1/S phase: Evidence for an effect mediated by PKCδ. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 2008, 292(1-2):26-35.

- Zheng X, Chang RL, Cui X-X, Avila GE, Hebbar V, Garzotto M, Shih WJ, Lin Y, Lu S-E, Rabson AB: Effects of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) in combination with paclitaxel (Taxol) on prostate Cancer LNCaP cells cultured in vitro or grown as xenograft tumors in immunodeficient mice. Clinical cancer research 2006, 12, 3444–3451.

- Fürstenberger G, Berry D, Sorg B, Marks F: Skin tumor promotion by phorbol esters is a two-stage process. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1981, 78, 7722–7726. [CrossRef]

- Schoental R: Toxicology and carcinogenic action of pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Cancer Research 1968, 28, 2237–2246.

- Zhao Y, Xia Q, Yin JJ, Lin G, Fu PP: Photoirradiation of dehydropyrrolizidine alkaloids—formation of reactive oxygen species and induction of lipid peroxidation. Toxicology letters 2011, 205, 302–309. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisbord SD, Soule JB, Kimmel PL: Poison on line—acute renal failure caused by oil of wormwood purchased through the Internet. New England journal of medicine 1997, 337, 825–827. [CrossRef]

- Winickoff JP, Houck CS, Rothman EL, Bauchner H: Verve and Jolt: deadly new Internet drugs. Pediatrics 2000, 106, 829–830. [CrossRef]

- Komarova TV, Baschieri S, Donini M, Marusic C, Benvenuto E, Dorokhov YL: Transient expression systems for plant-derived biopharmaceuticals. Expert review of vaccines 2010, 9, 859–876. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdeil J-L, Alemanno L, Niemenak N, Tranbarger TJ: Pluripotent versus totipotent plant stem cells: dependence versus autonomy? Trends in plant science 2007, 12, 245–252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko K, Steplewski Z, Glogowska M, Koprowski H: Inhibition of tumor growth by plant-derived mAb. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 7026–7030. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopertekh L, Schiemann J: Transient production of recombinant pharmaceutical proteins in plants: evolution and perspectives. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 26, 365–380. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyel JF, Twyman RM, Fischer R: Very-large-scale production of antibodies in plants: The biologization of manufacturing. Biotechnology Advances 2017, 35, 458–465. [CrossRef]

- Daniell H: Medical molecular pharming: expression of antibodies, biopharmaceuticals and edible vaccines via the chloroplast genome. In: Plant Biotechnology 2002 and Beyond: Proceedings of the 10 th IAPTC&B Congress –28, 2002 Orlando, Florida, USA: 2003. Springer: 371-376. 23 June.

- McCormick AA, Kumagai MH, Hanley K, Turpen TH, Hakim I, Grill LK, Tusé D, Levy S, Levy R: Rapid production of specific vaccines for lymphoma by expression of the tumor-derived single-chain Fv epitopes in tobacco plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1999, 96, 703–708. [CrossRef]

- Verch T, Yusibov V, Koprowski H: Expression and assembly of a full-length monoclonal antibody in plants using a plant virus vector. Journal of immunological methods 1998, 220(1-2):69-75.

- Nessa MU, Rahman MA, Kabir Y: Plant-produced monoclonal antibody as immunotherapy for cancer. BioMed Research International 2020, 2020.

- Tusé D, Ku N, Bendandi M, Becerra C, Collins R, Langford N, Sancho SI, López-Díaz de Cerio A, Pastor F, Kandzia R: Clinical safety and immunogenicity of tumor-targeted, plant-made Id-KLH conjugate vaccines for follicular lymphoma. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015.

- Gronenborn B, Matzeit V: Plant gene vectors and genetic transformation: plant viruses as vectors. In: Molecular Biology of Plant Nuclear Genes. Elsevier; 1989: 69-100.

- Xu J, Dolan MC, Medrano G, Cramer CL, Weathers PJ: Green factory: plants as bioproduction platforms for recombinant proteins. Biotechnology advances 2012, 30, 1171–1184. [CrossRef]

- Donini M, Marusic C: Current state-of-the-art in plant-based antibody production systems. Biotechnology letters 2019, 41:335-346.

- Houdelet M, Galinski A, Holland T, Wenzel K, Schillberg S, Buyel JF: Animal component-free Agrobacterium tumefaciens cultivation media for better GMP-compliance increases biomass yield and pharmaceutical protein expression in Nicotiana benthamiana. Biotechnology Journal 2017, 12, 1600721.

- Bulaon CJI, Khorattanakulchai N, Rattanapisit K, Sun H, Pisuttinusart N, Phoolcharoen W: Development of Plant-Derived Bispecific Monoclonal Antibody Targeting PD-L1 and CTLA-4 against Mouse Colorectal Cancer. Planta Medica 2024.

- Lee JH, Park SR, Phoolcharoen W, Ko K: Expression, function, and glycosylation of anti-colorectal cancer large single-chain antibody (LSC) in plant. Plant Biotechnology Reports 2020, 14:363-371.

- Park SR, Lee J-H, Kim K, Kim TM, Lee SH, Choo Y-K, Kim KS, Ko K: Expression and in vitro function of anti-breast cancer llama-based single domain antibody VHH expressed in tobacco plants. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 1354. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Gamboa I, Caparco AA, McCaskill J, Fuenlabrada-Velázquez P, Hays SS, Jin Z, Jokerst JV, Pokorski JK, Steinmetz NF: Inter-coat protein loading of active ingredients into Tobacco mild green mosaic virus through partial dissociation and reassembly of the virion. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 7168.

- Bulaon CJI, Khorattanakulchai N, Rattanapisit K, Sun H, Pisuttinusart N, Phoolcharoen W: Development of Plant-Derived Bispecific Monoclonal Antibody Targeting PD-L1 and CTLA-4 against Mouse Colorectal Cancer. Planta Medica 2024, 90, 305–315. [CrossRef]

- Bulaon CJI, Khorattanakulchai N, Rattanapisit K, Sun H, Pisuttinusart N, Strasser R, Tanaka S, Soon-Shiong P, Phoolcharoen W: Antitumor effect of plant-produced anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody in a murine model of colon cancer. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2023; 14, 1149455.

- Rattanapisit K, Bulaon CJI, Strasser R, Sun H, Phoolcharoen W: In vitro and in vivo studies of plant-produced Atezolizumab as a potential immunotherapeutic antibody. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 14146.

- Bulaon CJI, Sun H, Malla A, Phoolcharoen W: Therapeutic efficacy of plant-produced Nivolumab in transgenic C57BL/6-hPD-1 mouse implanted with MC38 colon cancer. Biotechnology Reports, 2023; 38, e00794.

- Izadi S, Gumpelmair S, Coelho P, Duarte HO, Gomes J, Leitner J, Kunnummel V, Mach L, Reis CA, Steinberger P: Plant-derived Durvalumab variants show efficient PD-1/PD-L1 blockade and therapeutically favourable FcR binding. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2024, 22, 1224–1237. [CrossRef]

- Shin JH, Oh S, Jang MH, Lee SY, Min C, Eu YJ, Begum H, Kim JC, Lee GR, Oh HB: Enhanced efficacy of glycoengineered rice cell-produced trastuzumab. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2024.

- Stark MC, Joubert AM, Visagie MH: Molecular farming of pembrolizumab and nivolumab. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 10045. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen KD, Kajiura H, Kamiya R, Yoshida T, Misaki R, Fujiyama K: Production and N-glycan engineering of Varlilumab in Nicotiana benthamiana. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2023; 14, 1215580.

- Park C, Kim K, Kim Y, Zhu R, Hain L, Seferovic H, Kim M-H, Woo HJ, Hwang H, Lee SH: Plant-Derived Anti-Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Antibody Suppresses Trastuzumab-Resistant Breast Cancer with Enhanced Nanoscale Binding. ACS nano 2024.

- Jin C, Kang YJ, Park SR, Oh YJ, Ko K: Production, expression, and function of dual-specific monoclonal antibodies in a single plant. Planta 2024, 259, 15. [CrossRef]

- Lu R-M, Hwang Y-C, Liu I-J, Lee C-C, Tsai H-Z, Li H-J, Wu H-C: Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. Journal of biomedical science, 2020; 27, 1–30.

- Phakham T, Bulaon CJI, Khorattanakulchai N, Shanmugaraj B, Buranapraditkun S, Boonkrai C, Sooksai S, Hirankarn N, Abe Y, Strasser R: Functional characterization of pembrolizumab produced in Nicotiana benthamiana using a rapid transient expression system. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2021; 12, 736299.

- Rattanapisit K, Phakham T, Buranapraditkun S, Siriwattananon K, Boonkrai C, Pisitkun T, Hirankarn N, Strasser R, Abe Y, Phoolcharoen W: Structural and in vitro functional analyses of novel plant-produced anti-human PD1 antibody. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 15205.

- Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, Tatiparti K, Bhise K, Kashaw SK, Iyer AK: PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Frontiers in pharmacology, 2017; 8, 561.

- Mattila PO, Babar Z-U-D, Suleman F: Assessing the prices and affordability of oncology medicines for three common cancers within the private sector of South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 2021; 21, 1–10.

- Steele JF, Peyret H, Saunders K, Castells-Graells R, Marsian J, Meshcheriakova Y, Lomonossoff GP: Synthetic plant virology for nanobiotechnology and nanomedicine. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2017, 9, e1447.

- Shahgolzari M, Pazhouhandeh M, Milani M, Yari Khosroushahi A, Fiering S: Plant viral nanoparticles for packaging and in vivo delivery of bioactive cargos. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2020, 12, e1629.

- Steinmetz NF, Masarapu H, He H: Tymovirus virus and virus-like particles as nanocarriers for imaging and therapeutic agents. In.: Google Patents; 2023.

- Ortega-Rivera OA, Beiss V, Osota EO, Chan SK, Karan S, Steinmetz NF: Production of cytoplasmic type citrus leprosis virus-like particles by plant molecular farming. Virology.

- Nikitin N, Trifonova E, Karpova O, Atabekov J: Biosafety of plant viruses for human and animals. Moscow University biological sciences bulletin, 2016; 71, 128–134.

- Wen AM, Steinmetz NF: Design of virus-based nanomaterials for medicine, biotechnology, and energy. Chemical Society Reviews 2016, 45, 4074–4126. [CrossRef]

- Sherman MB, Guenther RH, Tama F, Sit TL, Brooks CL, Mikhailov AM, Orlova EV, Baker TS, Lommel SA: Removal of divalent cations induces structural transitions in red clover necrotic mosaic virus, revealing a potential mechanism for RNA release. Journal of virology 2006, 80, 10395–10406. [CrossRef]

- Czapar AE, Steinmetz NF: Plant viruses and bacteriophages for drug delivery in medicine and biotechnology. Current opinion in chemical biology, 2017; 38, 108–116.

- Kim SM, Faix PH, Schnitzer JE: Overcoming key biological barriers to cancer drug delivery and efficacy. Journal of Controlled Release, 2017; 267, 15–30.

- Cheng X, Xie Q, Sun Y: Advances in nanomaterial-based targeted drug delivery systems. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology, 2023; 11, 1177151.

- Chariou PL, Lee KL, Wen AM, Gulati NM, Stewart PL, Steinmetz NF: Detection and imaging of aggressive cancer cells using an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted filamentous plant virus-based nanoparticle. Bioconjugate chemistry 2015, 26, 262–269. [CrossRef]

- Destito G, Yeh R, Rae CS, Finn M, Manchester M: Folic acid-mediated targeting of cowpea mosaic virus particles to tumor cells. Chemistry & biology 2007, 14, 1152–1162.

- Cho C-F, Yu L, Nsiama TK, Kadam AN, Raturi A, Shukla S, Amadei GA, Steinmetz NF, Luyt LG, Lewis JD: Viral nanoparticles decorated with novel EGFL7 ligands enable intravital imaging of tumor neovasculature. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 12096–12109. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti L, Novelli F, Tanno B, Leonardi S, Hizam VM, Arcangeli C, Santi L, Baschieri S, Lico C, Mancuso M: Peptide-Functionalized and Drug-Loaded Tomato Bushy Stunt Virus Nanoparticles Counteract Tumor Growth in a Mouse Model of Shh-Dependent Medulloblastoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 8911.

- Le DH, Lee KL, Shukla S, Commandeur U, Steinmetz NF: Potato virus X, a filamentous plant viral nanoparticle for doxorubicin delivery in cancer therapy. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 2348–2357. [CrossRef]

- Lin RD, Steinmetz NF: Tobacco mosaic virus delivery of mitoxantrone for cancer therapy. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 16307–16313. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czapar AE, Zheng Y-R, Riddell IA, Shukla S, Awuah SG, Lippard SJ, Steinmetz NF: Tobacco mosaic virus delivery of phenanthriplatin for cancer therapy. ACS nano 2016, 10, 4119–4126. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parhizkar E, Rafieipour P, Sepasian A, Alemzadeh E, Dehshahri A, Ahmadi F: Synthesis and cytotoxicity evaluation of gemcitabine-tobacco mosaic virus conjugates. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, 2021; 62, 102388.

- Alemzadeh E, Dehshahri A, Dehghanian AR, Afsharifar A, Behjatnia AA, Izadpanah K, Ahmadi F: Enhanced anti-tumor efficacy and reduced cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin delivered in a novel plant virus nanoparticle. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2019; 174, 80–86.

- Cao J, Guenther RH, Sit TL, Opperman CH, Lommel SA, Willoughby JA: Loading and release mechanism of red clover necrotic mosaic virus derived plant viral nanoparticles for drug delivery of doxorubicin. Small 2014, 10, 5126–5136. [CrossRef]

- Aljabali AA, Shukla S, Lomonossoff GP, Steinmetz NF, Evans DJ: Cpmv-dox delivers. Molecular pharmaceutics 2013, 10, 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Franke CE, Czapar AE, Patel RB, Steinmetz NF: Tobacco mosaic virus-delivered cisplatin restores efficacy in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Molecular pharmaceutics 2017, 15, 2922–2931.

- Le DH, Commandeur U, Steinmetz NF: Presentation and delivery of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand via elongated plant viral nanoparticle enhances antitumor efficacy. ACS nano 2019, 13, 2501–2510.

- Chan SK, Steinmetz NF: microRNA-181a silencing by antisense oligonucleotides delivered by virus-like particles. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2023, 11, 816–825. [CrossRef]

- Kim KR, Lee AS, Kim SM, Heo HR, Kim CS: Virus-like nanoparticles as a theranostic platform for cancer. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2023; 10, 1106767.

- Lam P, Lin RD, Steinmetz NF: Delivery of mitoxantrone using a plant virus-based nanoparticle for the treatment of glioblastomas. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2018, 6, 5888–5895. [CrossRef]

- Kernan DL, Wen AM, Pitek AS, Steinmetz NF: Featured Article: Delivery of chemotherapeutic vcMMAE using tobacco mosaic virus nanoparticles. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2017, 242, 1405–1411. [CrossRef]

- Esfandiari N, Arzanani MK, Soleimani M, Kohi-Habibi M, Svendsen WE: A new application of plant virus nanoparticles as drug delivery in breast cancer. Tumor Biology, 2016; 37, 1229–1236.

- Esfandiari N: Targeting breast cancer with bio-inspired virus nanoparticles. Archives of Breast Cancer, 2018; 90–95.

- Shukla S, Roe AJ, Liu R, Veliz FA, Commandeur U, Wald DN, Steinmetz NF: Affinity of plant viral nanoparticle potato virus X (PVX) towards malignant B cells enables cancer drug delivery. Biomaterials science 2020, 8, 3935–3943. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti L, Simon-Gracia L, Lico C, Mancuso M, Baschieri S, Santi L, Teesalu T: Targeting of Tomato Bushy Stunt Virus with a Genetically Fused C-End Rule Peptide. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1428. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkovich KJ, Zhao Z, Steinmetz NF: iRGD-Targeted Physalis Mottle Virus Like Nanoparticles for Targeted Cancer Delivery. Small Science 2023, 3, 2300067. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahgolzari M, Venkataraman S, Osano A, Akpa PA, Hefferon K: Plant Virus Nanoparticles Combat Cancer. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1278. [CrossRef]

- Chariou PL, Wang L, Desai C, Park J, Robbins LK, von Recum HA, Ghiladi RA, Steinmetz NF: Let there be light: Targeted photodynamic therapy using high aspect ratio plant viral nanoparticles. Macromolecular Bioscience 2019, 19, 1800407.

- Nkanga CI, Ortega-Rivera OA, Steinmetz NF: Photothermal immunotherapy of melanoma using TLR-7 agonist laden tobacco mosaic virus with polydopamine coat. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine, 2022; 44, 102573.

- Zhao Z, Simms A, Steinmetz NF: Cisplatin-loaded tobacco mosaic virus for ovarian cancer treatment. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 4379–4387. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam P, Steinmetz NF: Plant viral and bacteriophage delivery of nucleic acid therapeutics. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2018, 10, e1487.

- Shahgolzari M, Dianat-Moghadam H, Yavari A, Fiering SN, Hefferon K: Multifunctional plant virus nanoparticles for targeting breast cancer tumors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1431. [CrossRef]

- Lam P, Steinmetz NF: Delivery of siRNA therapeutics using cowpea chlorotic mottle virus-like particles. Biomaterials science 2019, 7, 3138–3142. [CrossRef]

- Villagrana-Escareño MV, Reynaga-Hernández E, Galicia-Cruz OG, Durán-Meza AL, la Cruz-González D, Hernández-Carballo CY, Ruíz-García J: VLPs derived from the CCMV plant virus can directly transfect and deliver heterologous genes for translation into mammalian cells. BioMed Research International 2019, 2019.

- Xue F, Cornelissen JJ, Yuan Q, Cao S: Delivery of MicroRNAs by plant virus-based nanoparticles to functionally alter the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Chinese Chemical Letters 2023, 34, 107448. [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Rivera A, Fournier PG, Arellano DL, Rodriguez-Hernandez AG, Vazquez-Duhalt R, Cadena-Nava RD: Brome mosaic virus-like particles as siRNA nanocarriers for biomedical purposes. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology 2020, 11, 372–382. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masarapu H, Patel BK, Chariou PL, Hu H, Gulati NM, Carpenter BL, Ghiladi RA, Shukla S, Steinmetz NF: Physalis mottle virus-like particles as nanocarriers for imaging reagents and drugs. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 4141–4153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz I, Shukla S, Steinmetz NF: Applications of viral nanoparticles in medicine. Current opinion in biotechnology 2011, 22, 901–908. [CrossRef]

- Hu H, Zhang Y, Shukla S, Gu Y, Yu X, Steinmetz NF: Dysprosium-modified tobacco mosaic virus nanoparticles for ultra-high-field magnetic resonance and near-infrared fluorescence imaging of prostate cancer. ACS nano 2017, 11, 9249–9258. [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz NF, Ablack AL, Hickey JL, Ablack J, Manocha B, Mymryk JS, Luyt LG, Lewis JD: Intravital imaging of human prostate cancer using viral nanoparticles targeted to gastrin-releasing peptide receptors. Small 2011, 7, 1664–1672. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla S, Dickmeis C, Nagarajan A, Fischer R, Commandeur U, Steinmetz N: Molecular farming of fluorescent virus-based nanoparticles for optical imaging in plants, human cells and mouse models. Biomaterials science 2014, 2, 784–797. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruckman MA, Randolph LN, Gulati NM, Stewart PL, Steinmetz NF: Silica-coated Gd (DOTA)-loaded protein nanoparticles enable magnetic resonance imaging of macrophages. Journal of materials chemistry B 2015, 3, 7503–7510. [CrossRef]

- Chung YH, Cai H, Steinmetz NF: Viral nanoparticles for drug delivery, imaging, immunotherapy, and theranostic applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 2020; 56, 214–235.

- Wu Z, Zhou J, Nkanga CI, Jin Z, He T, Borum RM, Yim W, Zhou J, Cheng Y, Xu M: One-step supramolecular multifunctional coating on plant virus nanoparticles for bioimaging and therapeutic applications. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2022, 14, 13692–13702.

- Pitek A, Hu H, Shukla S, Steinmetz N: Cancer theranostic applications of albumin-coated tobacco mosaic virus nanoparticles. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2018, 10, 39468–39477.

- Luzuriaga MA, Welch RP, Dharmarwardana M, Benjamin CE, Li S, Shahrivarkevishahi A, Popal S, Tuong LH, Creswell CT, Gassensmith JJ: Enhanced stability and controlled delivery of MOF-encapsulated vaccines and their immunogenic response in vivo. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2019, 11, 9740–9746.

- Dharmarwardana M, Martins AF, Chen Z, Palacios PM, Nowak CM, Welch RP, Li S, Luzuriaga MA, Bleris L, Pierce BS: Nitroxyl modified tobacco mosaic virus as a metal-free high-relaxivity MRI and EPR active superoxide sensor. Molecular pharmaceutics 2018, 15, 2973–2983. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruckman MA, Jiang K, Simpson EJ, Randolph LN, Luyt LG, Yu X, Steinmetz NF: Dual-modal magnetic resonance and fluorescence imaging of atherosclerotic plaques in vivo using VCAM-1 targeted tobacco mosaic virus. Nano letters 2014, 14, 1551–1558. [CrossRef]

- Valdivia G, Pérez-Alenza D, Barreno L, Alonso-Diez Á, de Oliveira JFA, Suárez-Redondo M, Fiering SF, Steinmetz NF, Peña L: Innovative CPMV immunotherapy: A canine model for poor-prognosis breast cancer treatment. Cancer Research, 2024; 84, (6_Supplement):6663-6663.

- Shahgolzari M, Fiering S: Emerging potential of plant virus nanoparticles (PVNPs) in anticancer immunotherapies. Journal of cancer immunology 2022, 4, 22.

- Jung E, Chung YH, Mao C, Fiering SN, Steinmetz NF: The Potency of Cowpea Mosaic Virus Particles for Cancer In Situ Vaccination Is Unaffected by the Specific Encapsidated Viral RNA. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2023, 20, 3589–3597. [CrossRef]

- Mao C, Beiss V, Fields J, Steinmetz NF, Fiering S: Cowpea mosaic virus stimulates antitumor immunity through recognition by multiple MYD88-dependent toll-like receptors. Biomaterials 2021, 275:120914.

- Shukla S, Wang C, Beiss V, Cai H, Washington T, Murray AA, Gong X, Zhao Z, Masarapu H, Zlotnick A: The unique potency of Cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) in situ cancer vaccine. Biomaterials science 2020, 8, 5489–5503. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu H, Steinmetz NF: Development of a virus-like particle-based anti-HER2 breast cancer vaccine. Cancers 2021, 13, 2909. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreno L, Sevane N, Valdivia G, Alonso-Miguel D, Suarez-Redondo M, Alonso-Diez A, Fiering S, Beiss V, Steinmetz NF, Perez-Alenza MD: Transcriptomics of canine inflammatory mammary cancer treated with empty cowpea mosaic virus implicates neutrophils in anti-tumor immunity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 14034.

- Shukla S, Myers JT, Woods SE, Gong X, Czapar AE, Commandeur U, Huang AY, Levine AD, Steinmetz NF: Plant viral nanoparticles-based HER2 vaccine: Immune response influenced by differential transport, localization and cellular interactions of particulate carriers. Biomaterials 2017, 121:15-27.

- Lebel M-È, Chartrand K, Tarrab E, Savard P, Leclerc D, Lamarre A: Potentiating cancer immunotherapy using papaya mosaic virus-derived nanoparticles. Nano letters 2016, 16, 1826–1832. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray AA, Wang C, Fiering S, Steinmetz NF: In situ vaccination with cowpea vs tobacco mosaic virus against melanoma. Molecular pharmaceutics 2018, 15, 3700–3716. [CrossRef]

- Cai H, Shukla S, Wang C, Masarapu H, Steinmetz NF: Heterologous prime-boost enhances the antitumor immune response elicited by plant-virus-based cancer vaccine. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019, 141, 6509–6518. [CrossRef]

- Shahgolzari M, Pazhouhandeh M, Milani M, Fiering S, Khosroushahi AY: Alfalfa mosaic virus nanoparticles-based in situ vaccination induces antitumor immune responses in breast cancer model. Nanomedicine 2020, 16, 97–107.

- Zhao Z, Chung YH, Steinmetz NF: Melanoma immunotherapy enabled by M2 macrophage targeted immunomodulatory cowpea mosaic virus. Materials Advances 2024, 5, 1473–1479. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla S, Jandzinski M, Wang C, Gong X, Bonk KW, Keri RA, Steinmetz NF: A viral nanoparticle cancer vaccine delays tumor progression and prolongs survival in a HER2+ tumor mouse model. Advanced therapeutics 2019, 2, 1800139. [CrossRef]

- Patel BK, Wang C, Lorens B, Levine AD, Steinmetz NF, Shukla S: Cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV)-based cancer testis antigen NY-ESO-1 vaccine elicits an antigen-specific cytotoxic T cell response. ACS applied bio materials 2020, 3, 4179–4187. [CrossRef]

- Cai H, Shukla S, Steinmetz NF: The antitumor efficacy of CpG oligonucleotides is improved by encapsulation in plant virus-like particles. Advanced functional materials 2020, 30, 1908743. [CrossRef]

- Iravani S, Varma RS: Vault, viral, and virus-like nanoparticles for targeted cancer therapy. Materials Advances 2023, 4, 2909–2917. [CrossRef]

- Jung E, Chung YH, Steinmetz NF: TLR Agonists Delivered by Plant Virus and Bacteriophage Nanoparticles for Cancer Immunotherapy. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2023, 34, 1596–1605. [CrossRef]

- Shin MD, Jung E, Moreno-Gonzalez MA, Ortega-Rivera OA, Steinmetz NF: Pluronic F127 “nanoarmor” for stabilization of Cowpea mosaic virus immunotherapy. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 2024, 9, e10574.

- Boone CE, Wang C, Lopez-Ramirez MA, Beiss V, Shukla S, Chariou PL, Kupor D, Rueda R, Wang J, Steinmetz NF: Active microneedle administration of plant virus nanoparticles for cancer in situ vaccination improves immunotherapeutic efficacy. ACS applied nano materials 2020, 3, 8037–8051. [CrossRef]

- Patel R, Czapar AE, Fiering S, Oleinick NL, Steinmetz NF: Radiation therapy combined with cowpea mosaic virus nanoparticle in situ vaccination initiates immune-mediated tumor regression. ACS omega 2018, 3, 3702–3707. [CrossRef]

- Karan S, Jung E, Boone C, Steinmetz NF: Synergistic combination therapy using cowpea mosaic virus intratumoral immunotherapy and Lag-3 checkpoint blockade. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2024, 73, 51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koellhoffer EC, Steinmetz NF: Cowpea mosaic virus and natural killer cell agonism for in situ cancer vaccination. Nano letters 2022, 22, 5348–5356. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam A, Beiss V, Wang C, Wang L, Steinmetz NF: Plant viral nanoparticle conjugated with anti-PD-1 peptide for ovarian cancer immunotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 9733. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee KL, Murray AA, Le DHT, Sheen MR, Shukla S, Commandeur U, Fiering S, Steinmetz NF: Combination of Plant Virus Nanoparticle-Based in Situ Vaccination with Chemotherapy Potentiates Antitumor Response. Nano Letters 2017, 17, 4019–4028. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai H, Wang C, Shukla S, Steinmetz NF: Cowpea mosaic virus immunotherapy combined with cyclophosphamide reduces breast cancer tumor burden and inhibits lung metastasis. Advanced science 2019, 6, 1802281. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z, Ortega-Rivera OA, Chung YH, Simms A, Steinmetz NF: A co-formulated vaccine of irradiated cancer cells and cowpea mosaic virus improves ovarian cancer rejection. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2023, 11, 5429–5441. [CrossRef]

- Barkovich KJ, Wu Z, Zhao Z, Simms A, Chang EY, Steinmetz NF: Physalis Mottle Virus-Like Nanocarriers with Expanded Internal Loading Capacity. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2023, 34, 1585–1595. [CrossRef]

- Almalki WH: An Up-to-date Review on Protein-based Nanocarriers in the Management of Cancer. Current Drug Delivery 2024, 21, 509–524. [CrossRef]

- Arul SS, Balakrishnan B, Handanahal SS, Venkataraman S: Viral nanoparticles: Current advances in design and development. Biochimie 2023.

- Shen L, Zhou P, Wang YM, Zhu Z, Yuan Q, Cao S, Li J: Supramolecular nanoparticles based on elastin-like peptides modified capsid protein as drug delivery platform with enhanced cancer chemotherapy efficacy. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 256:128107.

- Shah S, Famta P, Tiwari V, Kotha AK, Kashikar R, Chougule MB, Chung YH, Steinmetz NF, Uddin M, Singh SB: Instigation of the epoch of nanovaccines in cancer immunotherapy. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2023, 15, e1870.

- Chung YH, Zhao Z, Jung E, Omole AO, Wang H, Sutorus L, Steinmetz NF: Systemic Administration of Cowpea Mosaic Virus Demonstrates Broad Protection Against Metastatic Cancers. Advanced Science 2024:2308237.

- Valdivia G, Alonso-Miguel D, Perez-Alenza MD, Zimmermann ABE, Schaafsma E, Kolling IV FW, Barreno L, Alonso-Diez A, Beiss V, Affonso de Oliveira JF: Neoadjuvant intratumoral immunotherapy with cowpea mosaic virus induces local and systemic antitumor efficacy in canine mammary cancer patients. Cells 2023, 12, 2241.

- Chung YH, Ortega-Rivera OA, Volckaert BA, Jung E, Zhao Z, Steinmetz NF: Viral nanoparticle vaccines against S100A9 reduce lung tumor seeding and metastasis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120, e2221859120. [CrossRef]

- Truchado Martín DA, Juárez-Molina M, Rincón S, Zurita L, Tomé-Amat J, Lorz López MC, Ponz F: A multifunctionalized potyvirus-derived nanoparticle that targets and internalizes into cancer cells. 2024.

- Jung E, Foroughishafiei A, Chung YH, Steinmetz NF: Enhanced Efficacy of a TLR3 Agonist Delivered by Cowpea Chlorotic Mottle Virus Nanoparticles. Small Science 2024:2300314.

- Moreno-Gonzalez MA, Zhao Z, Caparco AA, Steinmetz NF: Combination of cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) intratumoral therapy and oxaliplatin chemotherapy. Materials Advances 2024.

- Ghani MA, Bangar A, Yang Y, Jung E, Sauceda C, Mandt T, Shukla S, Webster NJ, Steinmetz NF, Newton IG: Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Multimodal In Situ Vaccination Using Cryoablation and a Plant Virus Immunostimulant. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2023, 34, 1247–1257. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng Z, Zhang L, Hou X: Potential roles and molecular mechanisms of phytochemicals against cancer. Food & Function 2022, 13, 9208–9225.

- Oluwayelu DO, Adebiyi AI: Plantibodies in human and animal health: a review. African health sciences 2016, 16, 640–645. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheshukova E, Komarova T, Dorokhov Y: Plant factories for the production of monoclonal antibodies. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2016, 81:1118-113.