Introduction

Chronic liver disease (CLD) has a critical treat to humankind, such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is characterized by inflammation and fibrosis [

1]. A variety of pathological factors cause the occurrence of LF. Without timely intervention of related pathogenic factors, cirrhosis and even liver cancer will occur. And killed about 2 million people worldwide each year [

2]. The pathology of LF performance of collagen fiber and the extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulate, lead to the fibrotic changes [

3]. Inflammation promotes hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) activation, cytokines and chemokines and HSCs to differentiate into muscle fibroblasts collagen fibers, the activation of HSCs are important events in LF [

4]. LF is reversible [

5], Studies have shown that LF can be inhibited by TCM [

6,

7]. So far, however, no clinical effects of the approved drug therapy of LF [

8]. Therefore, looking for safe and effective anti-fibrosis drug is particularly important.

In recent years, TCM and related monomers have received extensive attention [

9]. With the deepening of understanding of TCM, the research shows that TCM contains complex ingredients, can be used in the treatment of many diseases [

10], a growing number of studies prove that TCM for CLD has certain curative effect [

11,

12,

13]. PS is a traditional Chinese medicine with many effects, such as improving immunity, preventing aging, protecting liver, and anti-cancer [

14,

15,

16].

TCM also has the advantage of less side effects [

17], PS to improve LF may have certain advantages, but there is no research prove that PS can inhibit LF, the principle of which is not clear.

Using network pharmacology make queries and predicted TCM targets and pathways, disease becomes effective [

18,

19]. The holistic view of treating diseases in TCM is consistent with the research ideas of network pharmacology [

20], Network pharmacology for the development of TCM and research provides new idea and method. In this study, we used the network composition and targets for pharmacology for PS and predicted the PS possible mechanisms by which inhibit LF (

Figure 1). And we found that PS can inhibit LF in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Network Pharmacology

Explore Targets of PS and BS

Build the Protein - Protein Interaction Network Diagram (PPI)

Venny 2.1.0 was used to find common targets for PS and LF. The targets were then entered into STRING 12.0 (

https://cn.string-db.org/) to construct the protein-protein interaction networks (PPI). Visualization of the PPI using Cytoscape 3.9.1[

25].

Enrichment Analysis

Then targets input to DAVID (

https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp) to get the results of enrichment. Through R 4.1.3, GO and KEGG were visualized and analyzed to further speculate the potential mechanism of drugs on LF[

26].

Drug Preparation and ReagentsIn Vitro Experimental Part

PS (purity: 99%, Batch number: 90082-98-7) was purchased from Shanghai Future Industrial Co., LTD. DMEM (Viva Cell C3113-0500), fetal bovine serum (LONSERA 5711-001S), trypsin (Biofroxx 9002-07-7), CCK-8(C0038), crystal violet staining solution (Beyotime C0121-100),TUNEL(Beyotime C1086), FITC-PI (Transgenbiotech R20901), fluorescent secondary antibody (Beyotime A0516), GAPDH (60004-1-Ig), α-SMA, Bcl-2, Bax, Caspase3, Caspase8, Caspase9, p53, Goat Anti-Mouse IgG-HRP, Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG-HRP. The antibodies were bought from Proteintech.

In Vivo Experimental Part

CCl4(MACKLIN 56-23-5), olive oil (MACKLIN 801-25-0), HE Stain kit (Beyotime C0105S), Masson Stain kit (Solarbio G1340), Sirius Red Stain kit (Solarbio G1472) AST detection kit and ALT detection kit were from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, antigen repair solution (Proteintech PR30001), DAB Horseradish Peroxidase Color Development Kit (Beyotime P0202).

LX-2 Cell Culture Protocol

From Wuhan Punosai Life Technology Co., LTD. Buy the life human source LX-2 cells. LX-2 cells contain 10% and 1% of the double resistance to serum DEME in training. Cells are placed at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2 in the constant temperature incubator (Themo 3111) training. All experiments in the 4 generation of cell.

Cell Viability Assay

Add 8000 cells/hole LX-2 cells in 96-well plate. The next day, add PS (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80mg/mL) into the cells. After 24h of drug treatment, 100μL CCK-8 reagent (DMEM: CCK-8=10:1) was added to the cells, and the steps were referred to the instructions of CCK-8.

Cell Cloning

Add 2000 cells/hole LX-2 cells in 24-well plate. After 72 hours, add PS (0, 5, 10, 20mg/mL). After 72 hours, add 200μL 4% paraformaldehyde into 24-well plates for 20min. In the dark place add crystal violet dye solution for 10min, rinsed with PBS, then observed and photographed.

Cellular Immunofluorescence

Add 2x10

5 LX-2 cells into 24-well plate. After 24h add 40ng/ml PDGF-BB[

27], 3nM Colchicine (CCC) [

28], 20mg/ml PS into the plate. The next day add 4% paraformaldehyde. 0.3%Triton X-100 was added and left for 15min at room temperature. 5% BSA was added for 45min. Antibody (1:200) was added overnight at 4℃. The next day add rabbit IgG-HRP (1:500) for 1h at room temperature. Then use microscope (Themo evo5000) to observe and take photos.

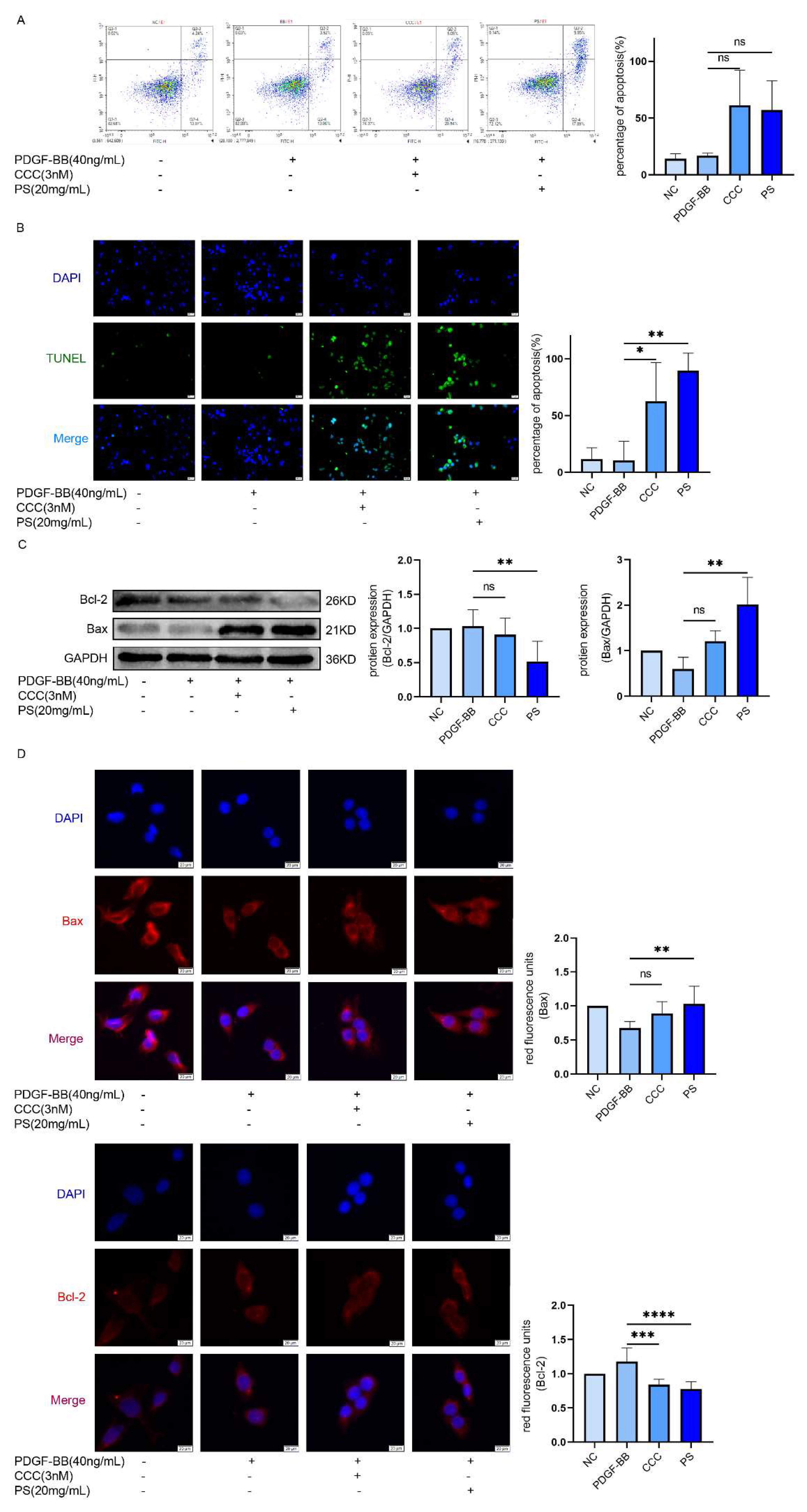

FITC-PI Double Staining to Detect Cell Apoptosis

2 x105 LX-2 cells were added into 24-well plate and then placed in a constant temperature incubator. After 24h, the cells were treated with PDGF-BB, CCC, and PS, respectively. (Refer to the instructions of the kit for specific steps).

Cell Apoptosis Was Detected by TUNEL Assay

2 x105 LX-2 cells were added to each of the 24 well plates and then placed in a constant temperature incubator. PDGF-BB, CCC and PS were added respectively, and then cultured in the incubator. After 24h, add 4% paraformaldehyde for 30min. (refer to the kit instructions for specific steps)

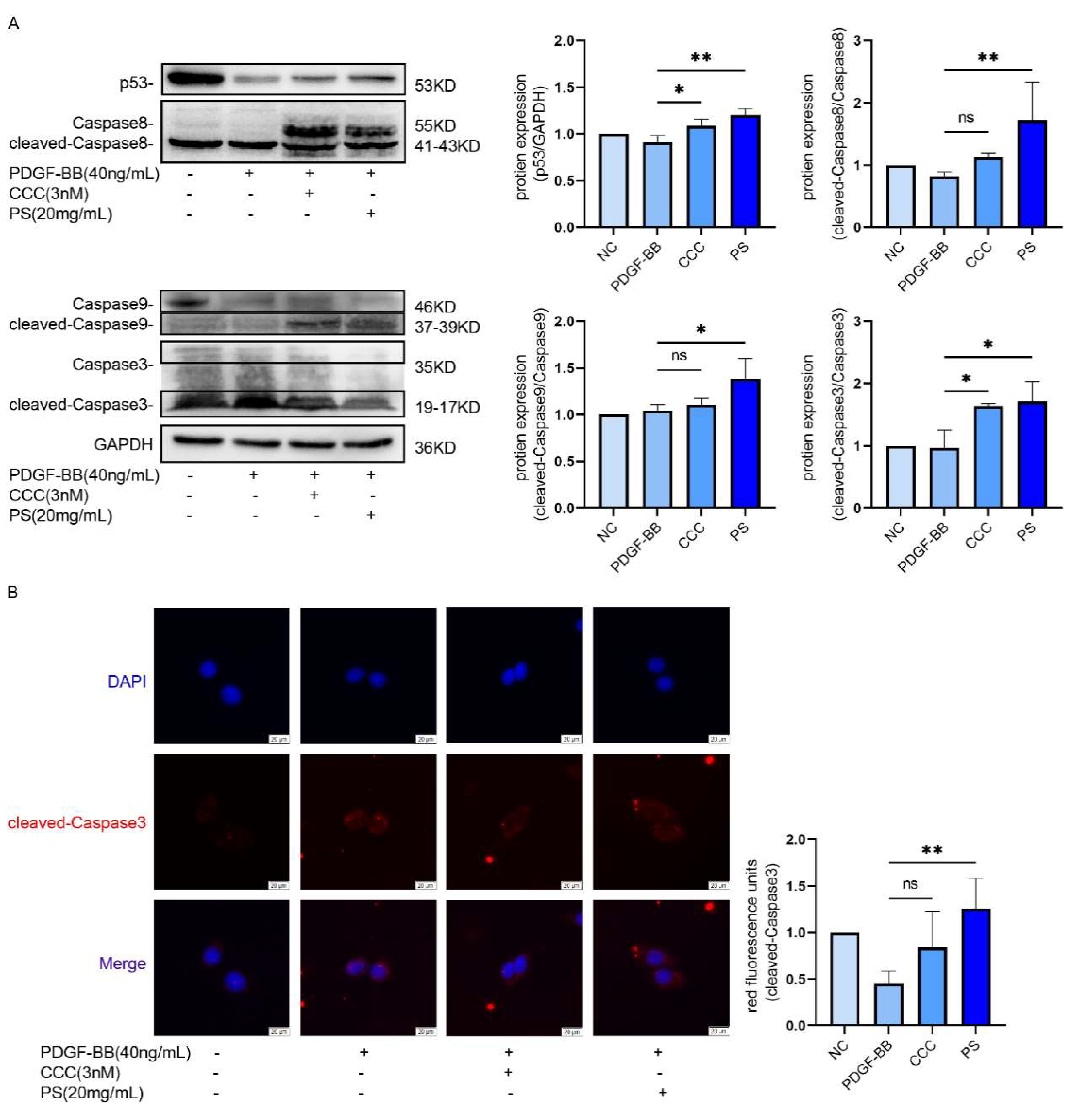

Western Blot

LX-2 cells protein extraction (refer to the instructions for specific steps). Loading Buffer was added to the sample, 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel was applied, and electrophoresis was started at 80V-120V voltage. PVDF membrane transfer was performed at the end of electrophoresis. PVDF membranes were put into 5% skim milk for 90min. PVDF membrane was placed in primary antibody and kept away from light overnight at 4℃. The PVDF membrane was removed and added rabbit IgG-HRP for 90min. Exposure was performed with chemiluminescent reagents and analyzed with Image Lab software. Western-blot method was consistent in vivo.

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from (Chengdu Dashuo), weigh 20g±2g, were bred at scientific research center of Chengdu Medical College. Standard 12h light and dark environment circulation, constant temperature 22°C±2°C, provide food and water. All used in the experiment of mice with healthy body, good immunity. Relevant experiments on animals were approved by the animal welfare committee. (Number: Chengdu Medical College animal ethics [2024] No. 032)

Animals Experiment Group

Put 40 mice into 4 groups, normal group, LF group, low PS group, high PS group. Except normal group, the rest groups were injected CCl

4 (0.6mL/kg) [

29] twice a week. After 5 weeks, the Low-dose PS group got PS (50mg/kg) by gavage, and High-dose PS group was treated with PS (200mg/kg) by gavage, 3 times a week for 4 weeks. After 4 weeks collect eyeball blood and livers for further experiments.

Detection of AST/ALT in Mouse Serum

Collect eyeball blood of mice, serum was centrifuged at 3000 R /min for 3min and stored at -20℃. ALT/AST content was detected by AST/ALT detection kit.

Liver Pathology Was Detected in Mice

After killing the mice, the livers were removed. The liver tissues were put into 4% formaldehyde and paraffin sectioned after 48 hours. The liver tissues were processed by HE, Masson, Sirius red and immunohistochemical reagents for staining and immuno-methods, respectively, and finally observed and photographed under the microscope.

Results

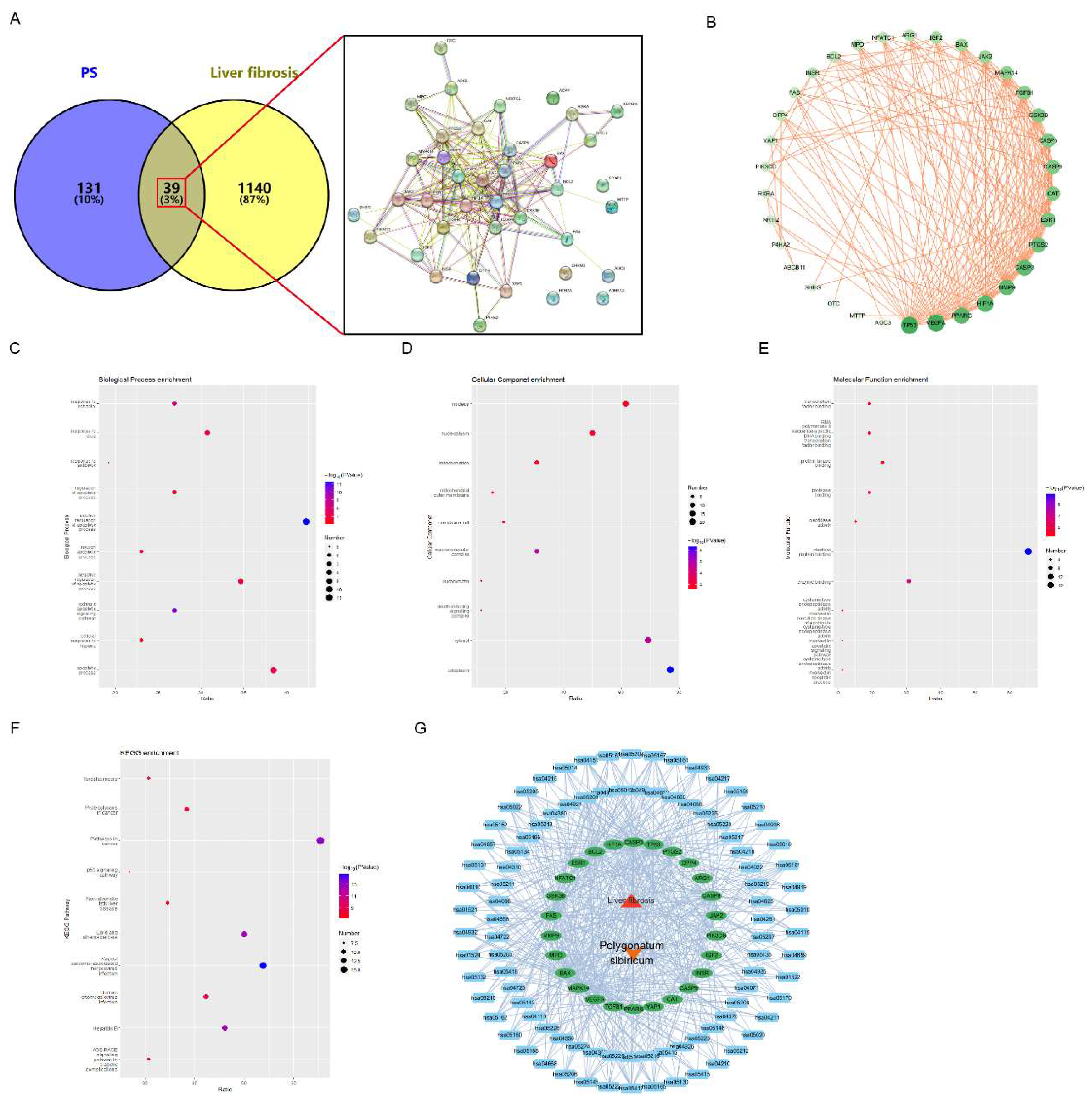

Network Pharmacology to Explore the Possible Ways in Which PS Inhibits LF

The full name of PS was entered into TCM database to search its targets, and 170 potential targets were found. The number of LF targets in the disease database is 1179. The drug targets and LF targets were intersected by venny 2.1.0, and 39 common targets were found. Then input the 39 common targets into the STRING 12.0 to construct protein interaction network (PPI), (

Figure 1A). Using Cytoscape 3.9.1 to analyze PPI data, we concluded that tp53 is the core target. And the deeper color means the more important target (

Figure 1B). We input the top 26 key targets of

Figure 1B into DAVID database for enrichment analysis to determine the possible mechanism of PS on LF. The Biological process (BP) term found key targets mainly related to promoting apoptotic processes, response to drugs (

Figure 1C). The cellular component (CC) term found that the key targets were mainly related to the cytoplasm, nucleus, and mitochondria (Figure 1D). The analysis results of the molecular function (MF) term showed that the key targets were mainly related to protein binding, protein modification, and enzyme binding (

Figure 1E). It is obvious that the key targets have a strong relationship with the p53 pathway and cancer pathway (

Figure 1F).

Figure 1G shows the PS-LF-target-pathway network diagram, where the red triangle is LF, the orange V-shape is PS, the green ellipse is the key targets, and the blue square is the KEGG pathways.

Figure 1.

Network pharmacology analysis results. Venny diagram and PPI of PS and LF targets (A). Shows the relationship of common targets (B). Enrichment results of the important targets (C. BP, D. CC, E. MF, F. pathway). PS-LF-target-pathway visualization network (G).

Figure 1.

Network pharmacology analysis results. Venny diagram and PPI of PS and LF targets (A). Shows the relationship of common targets (B). Enrichment results of the important targets (C. BP, D. CC, E. MF, F. pathway). PS-LF-target-pathway visualization network (G).

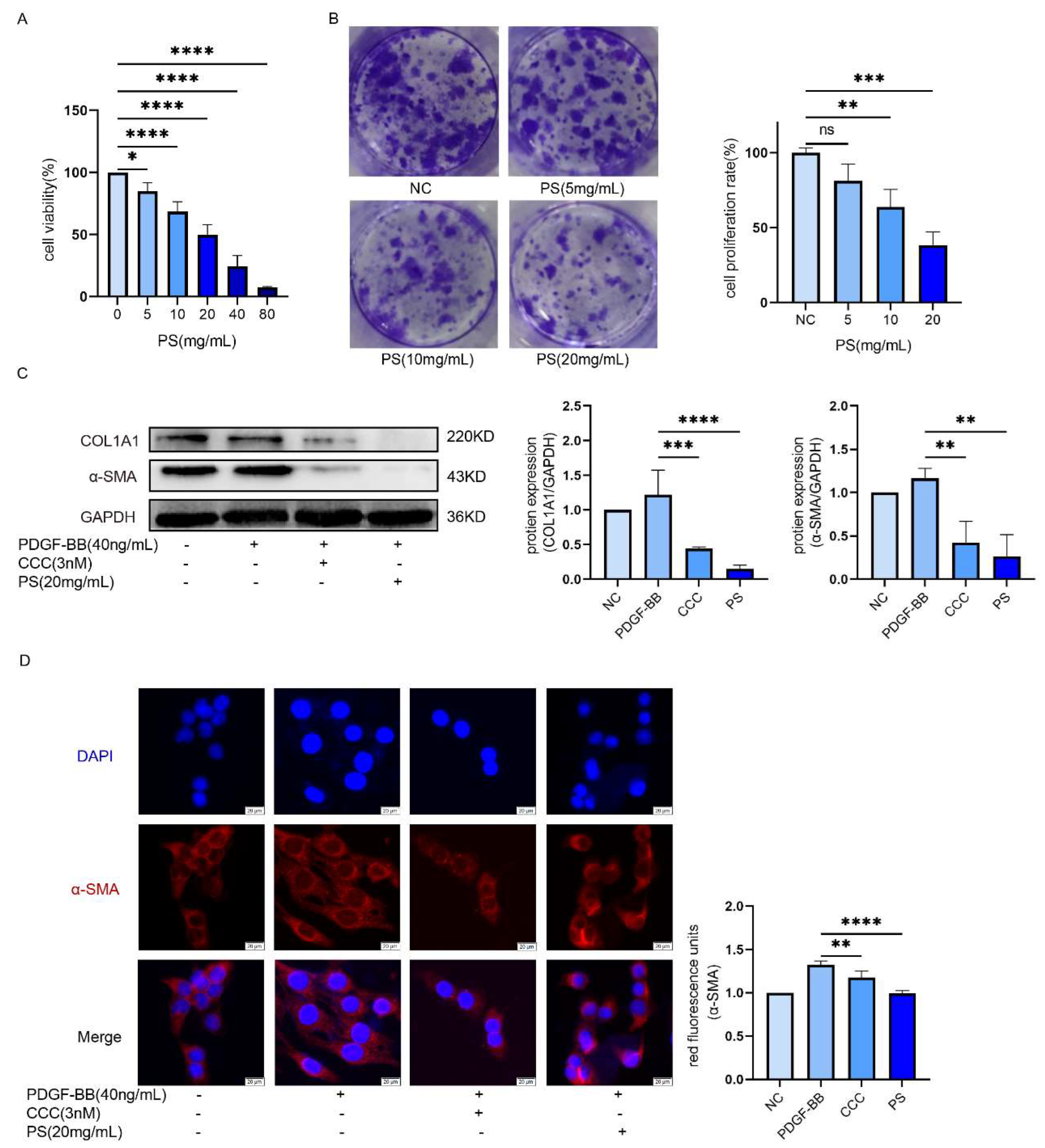

LX-2 cells were inhibited by PS

The activation of HSCs is the beginning of the LF. To explore whether PS can inhibit HSCs. We add (0-80 mg/mL) of PS into LX-2 cells to explore PS could inhibit LX-2 cells proliferation. The results of CCK-8 experiment showed the survival rate of LX-2 cells decreased with the increase of drug concentration (IC

50≈20mg/ml was used as the concentration of experimental group in subsequent experiments) (

Figure 2A). According to Cell cloning experiments, with the drug concentration increased, the proliferation of LX-2 cells is decreased (

Figure 2B). Compared with the PDGF-BB group, the expression of α-SMA and COL1A1 in CCC and PS group was decreased (

Figure 2C). The results of immunofluorescence showed that the red fluorescence intensity gradually decreased, that means α-SMA of LX-2 was decreased (

Figure 2D). These results indicate that LX-2 cells could be inhibited by PS.

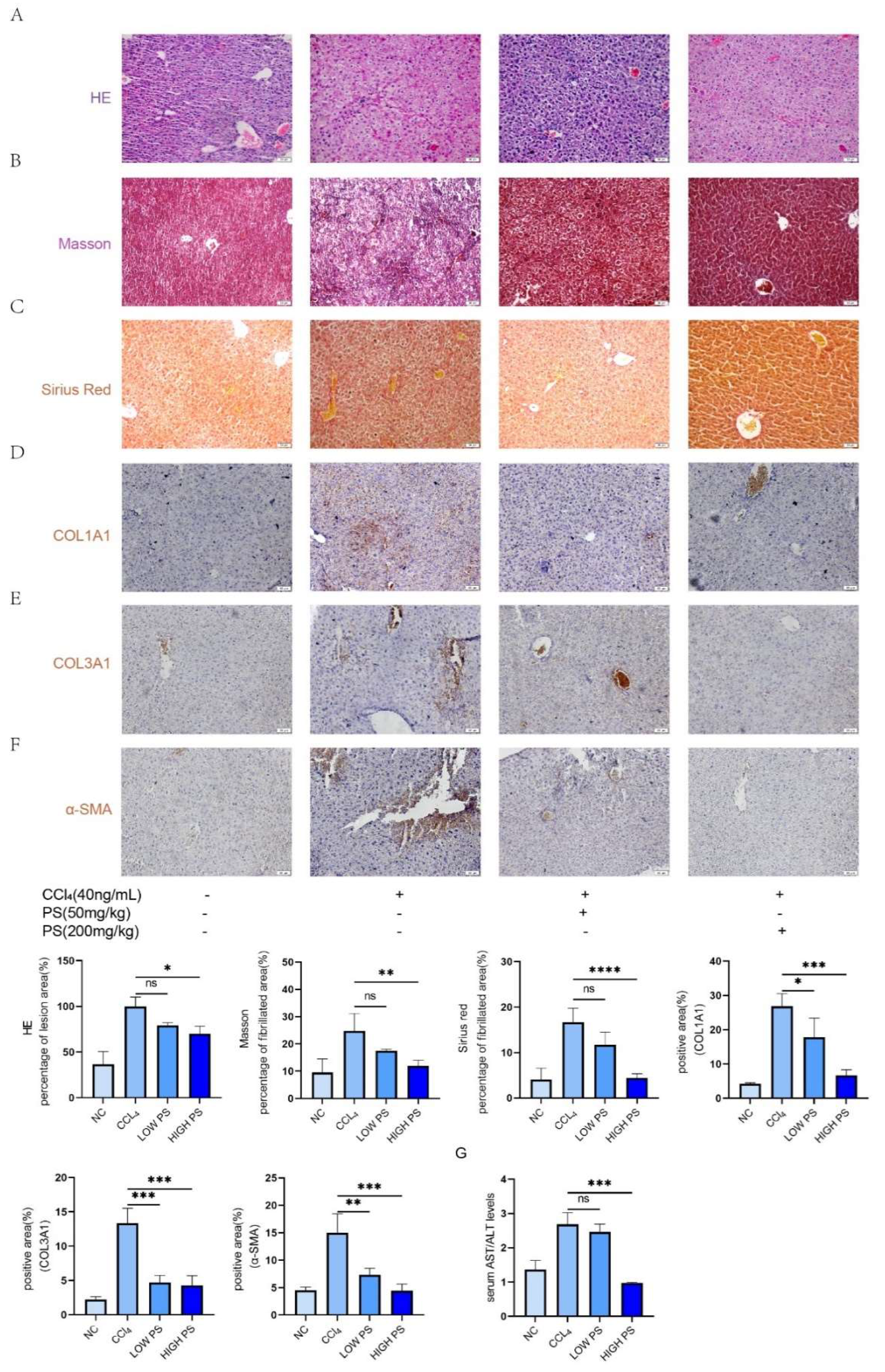

Inhibitory Effect of PS on LF In Vivo

To explore the effect of PS on LF in vivo, we constructed LF model by injecting CCl

4 to mice. HE stains can learn that compared to normal group, the liver cells in model group are disorder, fatty change and liver cells had been vacuolated. In contrast, the liver cells of the treatment group showed a relatively orderly arrangement and reduced the incidence of fatty degeneration (

Figure 3A). From Masson staining, we can see that the blood vessel wall and surrounding tissues produced obvious dark blue fibers in the model group (

Figure 3B). And in the treatment group the number of blue fibers has decreased, the LF conditions had been inhibited. From Sirius Red staning we can learn that the collagen fiber (in red color) in model group is more than in normal group, however in treatment groups the number of collagen fiber is less than model group (

Figure 3C). Immunohistochemical results showed that compared with the model group mice, the expression of COL1A1, COL3A1, and α-SMA antibodies in the liver tissues of the drug-treated group mice gradually decreased with the increase of drug concentration (

Figure 3D–F). Compared with the normal group, the AST/ALT ratio in the serum of mice in the model group (injected with CCl

4 only) was significantly elevated; and with the increase of PS concentration, the AST/ALT ratio was significantly decreased (

Figure 3G). The above results indicated that the LF situation in mice gradually improved with the increase of PS drug concentration.

Discussion

TCM treatment is considered the most common treatment in China. PS as a kind of medicine edible Chinese herbal medicine, has been active since was found in clinical treatment, it has a history of more than 2000 years [

30]. Nowadays, many diseases are treated by PS in clinical practice [

31]. A study shows that PS also has an anti-injury effect on the liver [

32]. However, no studies have shown that PS can anti LF.

We combined network pharmacology with basic experiments to investigate the underlying mechanisms of PS in inhibiting LF. Network pharmacology results showed that PS and hepatic fibrosis had 39 common targets, indicating that hepatic fibrosis may be regulated by PS and these targets were inhibited. It can be found in enrichment analysis that it is related to apoptosis pathway, p53 signaling pathway and other pathways. And studies have pointed out that kill HSCs, can inhibit the development of LF [

33,

34]. Bax and Bcl-2 protein as the regulation of cell apoptosis factor [

35]. When Bax expression quantity increases, the Bcl-2 expression quantity cut will promote cell apoptosis [

36]. α-SMA , COL1A1 and COL3A1 as phenotypic protein of LF and HSCs activation markers, if by drugs to lower their expression levels can slow the progression of LF [

37,

38,

39]. Studies have shown that drugs induce HSCs to die by enhancing the expression of protein p53 [

40], The increased expression of a series of apoptotic factors Caspase3, Caspase8, and Caspase9 can significantly promote the apoptosis of HSCs. We established a mouse model of LF by injection of CCl

4 to explore whether PS could inhibit LF. Serological indexes AST/ALT activity [

41], Inhibition of LF was demonstrated by HE, Masson, Sirius Red staining and immunohistochemistry [

42]. The results show that the PS can inhibit the LF.

In addition, PS can promote the expression of Bax, cleaved-Caspase3, cleaved-Caspase8 and cleaved-Caspase9, and inhibit the expression of Bcl-2, α-SMA, COL1A1 and COL3A1. More importantly, we guess through the analysis of the basic experiment verify the network pharmacology: PS can through the regulation of p53/Caspase8/Caspase9/Caspase3 signaling pathway to promote hepatic stellate cell senescence and apoptosis and inhibiting LF.

The disadvantages of today by CCC in clinical treatment of LF is that it is toxic to organs [

43,

44]. Compared with the toxicity of CCC, PS is safer. There are other monomer components in PS that have not been experimentally verified, which is the deficiency of our study. In the future study, we will add other monomer components for further in-depth exploration to find more effective monomer components, for clinical treatment and prevention of LF provide safer and more effective ideas and solutions.

Conclusion

Our research by combining network pharmacology and basic experiment, our study analyzed the effect and possible mechanism of PS in inhibiting LF. The results indicate that PS may inhibit LF by regulating p53/Caspase8/Caspase9/Caspase3 signaling pathway to cause apoptosis of HSCs. The results provide a more novel and reliable plan to treat LF in clinical.

Author Contribution

Haotian Shen and Xue Hu contributed equally to this work. Haotian Shen: Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing - manuscript. Xue Hu: Data processing, Software. Yang Song and Ying Du: Data processing, Formal analysis and Supervision. Bin Tang: Writing - review & editing. Fengmei Deng: Fund preparation, Writing - editing.

Acknowledgments

The research is financially supported by Chengdu Medical College graduate innovative research fund project (No: YCX2023-01-02), and Chengdu Medical College “Sichuan gerontology Clinical medical Research Center” (NO. 23LHPDZZD06), Chengdu Medical College Chengdu Medical College “Sichuan Elderly care and elderly health Collaborative innovation Center” (NO. 23LHNBZZD08). The study datas can be got from the corresponding author. Relevant experiments on animals approved by the animal welfare committee of Chengdu Medical College (Number: Chengdu Medical College animal ethics [2024] No. 032).

Declaration of Interests

No conflicts of interest.

References

- Hammerich, L.; Tacke, F. Hepatic inflammatory responses in liver fibrosis. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat 2023, 20, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehlen, N.; Crouchet, E.; Baumert, T.F. Liver Fibrosis: Mechanistic Concepts and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells-Basel 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, Y.; Su, H.; Lian, X.; etc. Pathogenesis of Liver Fibrosis and Its TCM Therapeutic Perspectives. Evid-Based Compl Alt 2022, 2022, 5325431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydın, M.M.; Akçalı, K.C. Liver fibrosis. Turk J Gastroenterol 2018, 29, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataller, R.; Brenner, D.A. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2005, 115, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, L.; Hao, Y.; Song, H.; etc. Efficacy and potential mechanisms of the main active ingredients of astragalus mongholicus in animal models of liver fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 319, 117198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du B; You, S. Present situation in preventing and treating liver fibrosis with TCM drugs. J Tradit Chin Med 2001, 21, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Huang, Y.; Zou, Q. Peptide-Based Nanoarchitectonics for the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis. Chembiochem 2023, 24, e202300002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Ding, Y.; etc. Protective effect of traditional Chinese medicine on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver cancer by targeting ferroptosis. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1033129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Su, H.; Lian, X.; etc. Pathogenesis of Liver Fibrosis and Its TCM Therapeutic Perspectives. Evid-Based Compl Alt 2022, 2022, 5325431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaji, A.N.; Sun, M. Zeaxanthin Dipalmitate in the Treatment of Liver Disease. Evid-Based Compl Alt 2019, 2019, 1475163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Y; Guo, J. ; Liu, Z.; etc. Calenduloside E ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via modulating a pyroptosis-dependent pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 319, 117239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Yang, G.; Sun, T.; etc. Capsaicin receptor TRPV1 maintains quiescence of hepatic stellate cells in the liver via recruitment of SARM1. J Hepatol 2023, 78, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Wang, S.; Cao, H.; etc. A Review: The Bioactivities and Pharmacological Applications of Polygonatum sibiricum polysaccharides. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Tang, W.; Han, C.; etc. Advances in Polygonatum sibiricum polysaccharides: Extraction, purification, structure, biosynthesis, and bioactivity. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1074671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Patil, S.; Qian, A.; etc. Bioactive Compounds of Polygonatum sibiricum - Therapeutic Effect and Biological Activity. Endocr Metab Immune 2022, 22, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Han, L.; Wang, X.; etc. Exploring the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effect of Salvia miltiorrhiza in diabetic nephropathy using network pharmacology and molecular docking. Bioscience Rep 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Yuan, T.; Wang, R.; etc. Network pharmacology approach and experimental verification of Dan-Shen Decoction in the treatment of ischemic heart disease. Pharm Biol 2023, 61, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xu, Y.; Tan, H.L.; etc. The Key Ingredient Acacetin in Weishu Decoction Alleviates Gastrointestinal Motility Disorder Based on Network Pharmacology Analysis. Mediat Inflamm 2021, 2021, 5265444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Ding, J.; Hong, H.H.; etc. Identifying the Mechanism of Polygoni Cuspidati Rhizoma et Radix in Treating Acute Liver Failure Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Gastroent Res Pract 2022, 2022, 2021066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hou, J.; Liu, Y.; etc. Using Network Pharmacology to Explore the Mechanism of Panax notoginseng in the Treatment of Myocardial Fibrosis. J Diabetes Res 2022, 2022, 8895950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Li, L.; Hu, Z. Exploring the Molecular Mechanism of Action of Yinchen Wuling Powder for the Treatment of Hyperlipidemia, Using Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 9965906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; etc. Bioinformatics and Network Pharmacology Identify the Therapeutic Role and Potential Mechanism of Melatonin in AD and Rosacea. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 756550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.; Song, T.; Ge, C.; etc. Identification of bioactive compounds and potential mechanisms of scutellariae radix-coptidis rhizoma in the treatment of atherosclerosis by integrating network pharmacology and experimental validation. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 165, 115210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.J.; Chen, X.H.; Liang, P.Y.; etc. Mechanism of anti-hyperuricemia of isobavachin based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Comput Biol Med 2023, 155, 106637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Peng, C.; Wang, L.; etc. Network pharmacology and experimental validation-based approach to understand the effect and mechanism of Taohong Siwu Decoction against ischemic stroke. J Ethnopharmacol 2022, 294, 115339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Shen, H.; Liu, R.; etc. Mechanism of acacetin regulating hepatic stellate cell apoptosis based on network pharmacology and experimental verification. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Kao, Y.H.; etc. Colchicine modulates calcium homeostasis and electrical property of HL-1 cells. J Cell Mol Med 2016, 20, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.J.; Kim, G.H.; Park, Y.; etc. Suaeda glauca Attenuates Liver Fibrosis in Mice by Inhibiting TGFβ1-Smad2/3 Signaling in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xu, S.; Bi, J.; etc. Metabolomics study of polysaccharide extracts from Polygonatum sibiricum in mice based on (1) H NMR technology. J Sci Food Agr 2020, 100, 4627–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ni, L.; Hu, S.; etc. Polygonatum sibiricum ameliorated cognitive impairment of naturally aging rats through BDNF-TrkB signaling pathway. J Food Biochem 2022, 46, e14510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Wang, S.; Cao, H.; etc. A Review: The Bioactivities and Pharmacological Applications of Polygonatum sibiricum polysaccharides. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, H.; Zhang, D.; Shi, J.; etc. Sorafenib induces autophagic cell death and apoptosis in hepatic stellate cell through the JNK and Akt signaling pathways. Anti-Cancer Drug 2016, 27, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymann, F.; Tacke, F. Immunology in the liver--from homeostasis to disease. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat 2016, 13, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaumer, S.; Guénal, I.; Brun, S.; etc. Bcl-2 and Bax mammalian regulators of apoptosis are functional in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ 2000, 7, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, C.; Hoy, T.; Bentley, D.P. Bcl-2/Bax ratios in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and their correlation with in vitro apoptosis and clinical resistance. Brit J Cancer 1997, 76, 935–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; etc. SIRT3 regulates mitophagy in liver fibrosis through deacetylation of PINK1/NIPSNAP1. J Cell Physiol 2023, 238, 2090–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Zou, J.; Zhu, X.; etc. Physalin D attenuates hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by blocking TGF-β/Smad and YAP signaling. Phytomedicine 2020, 78, 153294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, A.Y.; Ding, Q.; Li, Z.; etc. Doxazosin Attenuates Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting Autophagy in Hepatic Stellate Cells via Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther 2021, 15, 3643–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Chen, M.H.; Guo, Q.L.; etc. Interleukin-10 induces senescence of activated hepatic stellate cells via STAT3-p53 pathway to attenuate liver fibrosis. Cell Signal 2020, 66, 109445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Huang, C.; Wu, Q.; etc. Sini San ameliorates CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice by inhibiting AKT-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 303, 115965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, P.; Zhao, T.; etc. E Se tea extract ameliorates CCl(4) induced liver fibrosis via regulating Nrf2/NF-κB/TGF-β1/Smad pathway. Phytomedicine 2023, 115, 154854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, Y.; Aks, S.E.; Hutson, J.R.; etc. Colchicine poisoning: the dark side of an ancient drug. Clin Toxicol 2010, 48, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; etc. Secalonic acid A reduced colchicine cytotoxicity through suppression of JNK, p38 MAPKs and calcium influx. Neurochem Int 2011, 58, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).