Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Isolated Glandular Trichome Disc Cell Response to In Vitro Conditions for 24 h

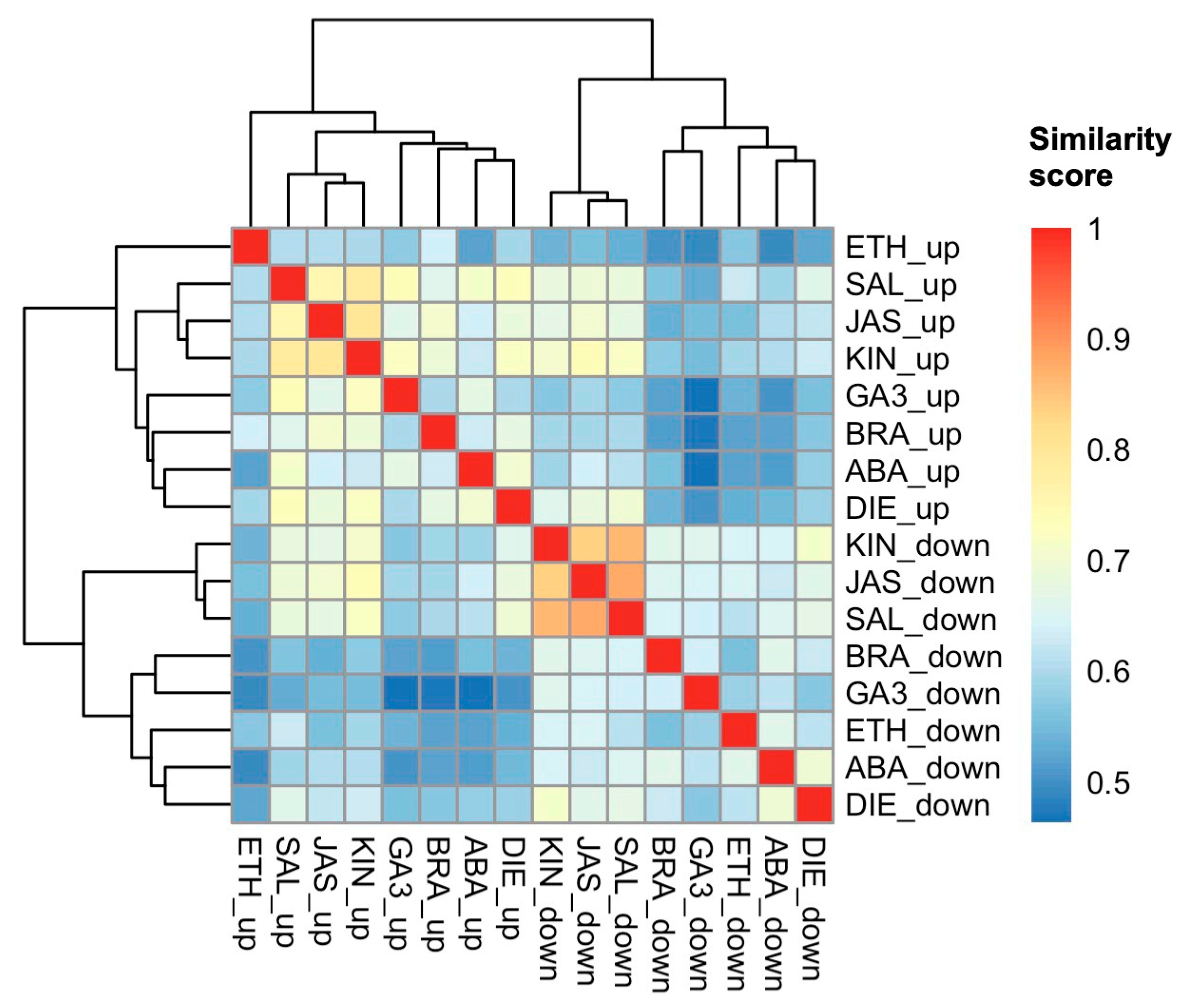

2.2. Proteome Responses of Glandular Trichome Disc Cells to Phytohormone Treatments

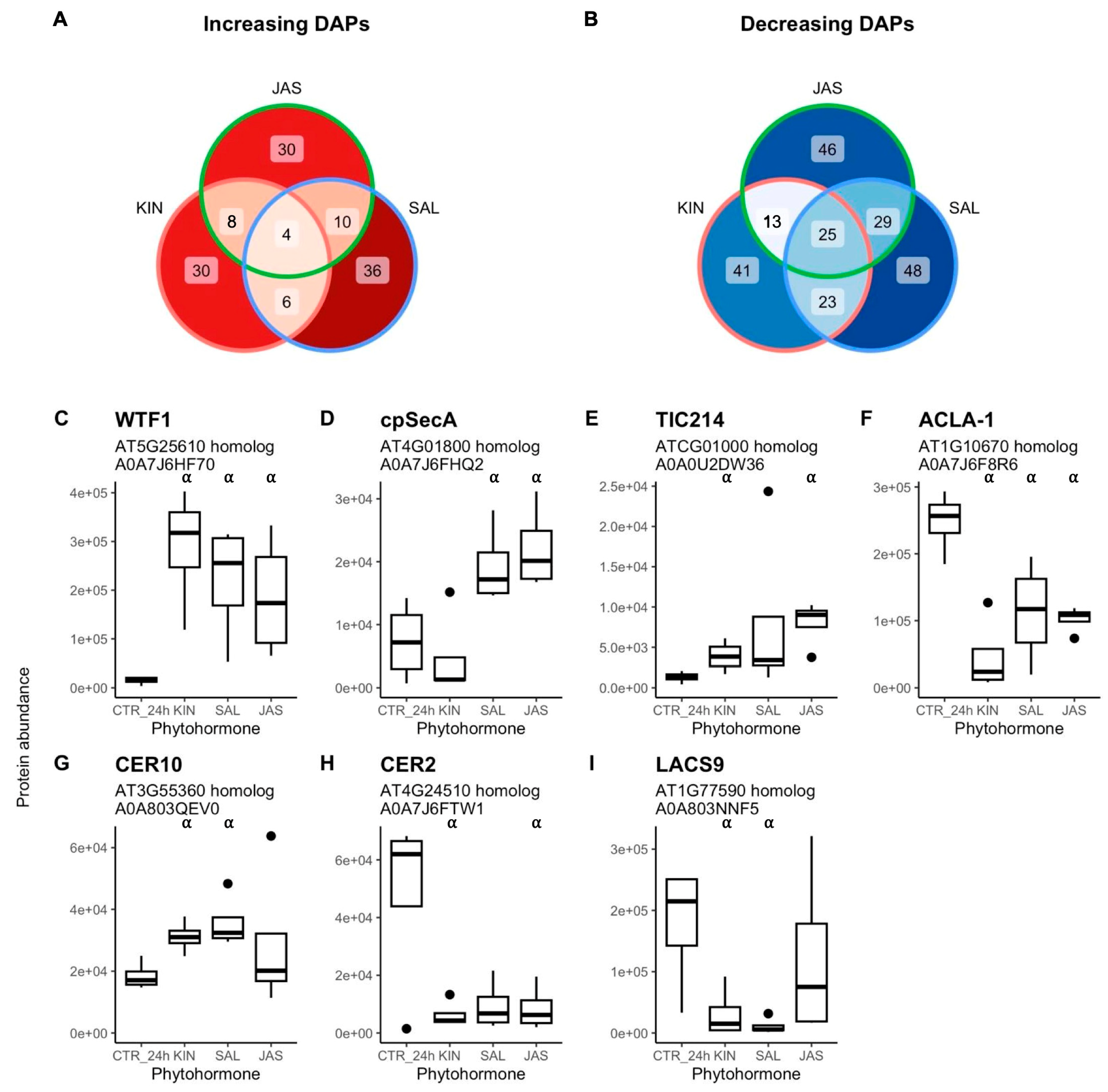

2.3. DAPs and Biological Processes Shared Between Group 2 Phytohormones

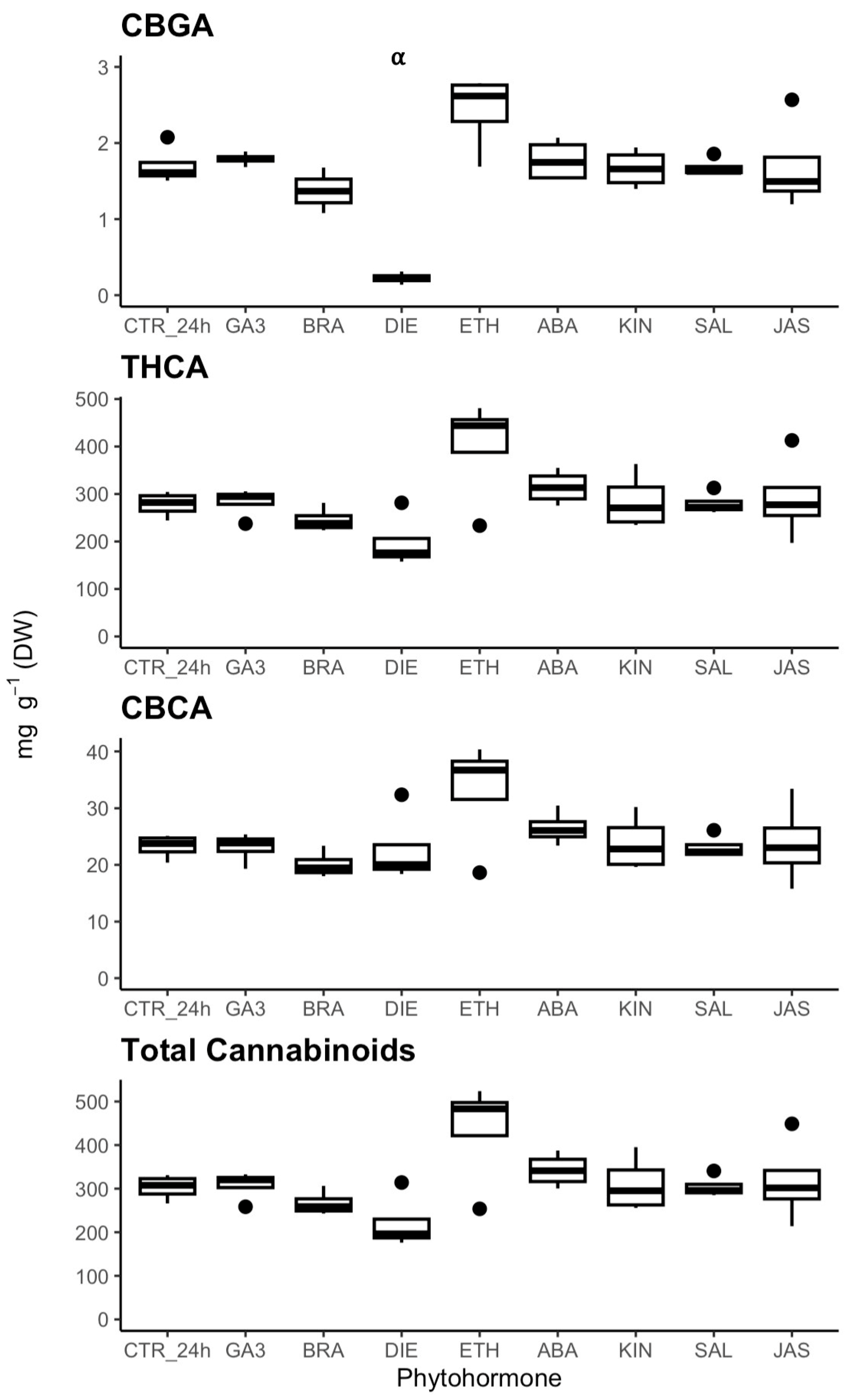

2.4. Phytohormonal Effects on Cannabinoid Metabolism

3. Discussion

3.1. In Vitro GT Assay Proof of Concept

3.2. Phytohormone Regulation of Cannabinoid Biosynthesis

3.2. GT Changes in Common Between Kinetin, Jasmonic Acid, and Salicylic Acid Indicate Roles in Coordinating Trichome Specific Features

3.3. Diethyldithiocarbamate (DIE) Is a Negative Regulator of Cannabinoid Biosynthesis

3.4. JAS Is a Key Coordinating Phytohormone for GT Initiation and Development in Cannabis

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Grow Conditions and Plant Propagation

4.2. Trichome Disc Cell Isolation

4.3. In vitro Phytohormone Treatment

4.4. Protein Extraction

4.5. LC–MS/MS Analysis of Cannabis GT Proteome

4.6. Metabolite Extraction from Cannabis GT

4.7. HPLC-UV Analysis of Cannabinoids from Cannabis GT Cells

4.8. Statistical and Bioinformatic Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Kovalchuk, I.; Pellino, M.; Rigault, P.; Velzen, R.V.; Ebersbach, J.; Ashnest, J.R.; Mau, M.; Schranz, M.E.; Alcorn, J.; Laprairie, R.B. The genomics of Cannabis and its close relatives. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, S.J.; Quilichini, T.D.; Booth, J.K.; Wong, D.C.J.; Rensing, K.H.; Laflamme-Yonkman, J.; Castellarin, S.D.; Bohlmann, J.; Page, J.E.; Samuels, A.L. Cannabis glandular trichomes alter morphology and metabolite content during flower maturation. Plant Journal 2020, 101, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, D. The propagation, characterisation and optimisation of Cannabis sativa L as a phytopharmaceutical. King’s College London, London, United Kingdom, 2009.

- Mahlberg, P.G.; Eun, S.K. Accumulation of cannabinoids in glandular trichomes of Cannabis (Cannabaceae). Journal of Industrial Hemp 2004, 9, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.; Naraine, S.G.U. Size matters: evolution of large drug-secreting resin glands in elite pharmaceutical strains of Cannabis sativa (marijuana). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2016, 63, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, G.M.; Snyder, S.I.; Toth, J.A.; Quade, M.A.; Crawford, J.L.; McKay, J.K.; Jackowetz, J.N.; Wang, P.; Philippe, G.; Hansen, J.L.; et al. Cannabinoids function in defense against chewing herbivores in Cannabis sativa L. Horticulture Research 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuutinen, T. Medicinal properties of terpenes found in Cannabis sativa and Humulus lupulus. Eur J Med Chem 2018, 157, 198–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Kumar, U. Cannabinoid receptors and the endocannabinoid system: Signaling and function in the central nervous system. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.B. Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects. British Journal of Pharmacology 2011, 163, 1344–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conneely, L.J.; Mauleon, R.; Mieog, J.; Barkla, B.J.; Kretzschmar, T. Characterization of the Cannabis sativa glandular trichome proteome. PLoS ONE 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, S.J.; Rensing, K.H.; Page, J.E.; Samuels, A.L. A polarized supercell produces specialized metabolites in cannabis trichomes. Current Biology 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Sanchez, I.J.; Verpoorte, R. PKS activities and biosynthesis of cannabinoids and flavonoids in Cannabis sativa L. plants. Plant and Cell Physiology 2008, 49, 1767–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagne, S.J.; Stout, J.M.; Liu, E.; Boubakir, Z.; Clark, S.M.; Page, J.E. Identification of olivetolic acid cyclase from Cannabis sativa reveals a unique catalytic route to plant polyketides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012, 109, 12811–12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellermeier, M.; Zenk, M.H. Prenylation of olivetolate by a hemp transferase yields cannabigerolic acid, the precursor of tetrahydrocannabinol. FEBS Letters 1998, 427, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirikantaramas, S.; Taura, F.; Tanaka, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; Morimoto, S.; Shoyama, Y. Tetrahydrocannabinolic Acid Synthase, the Enzyme Controlling Marijuana Psychoactivity, is Secreted into the Storage Cavity of the Glandular Trichomes. Plant and Cell Physiology 2005, 46, 1578–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Baron, H.; Alzate, J.F.; Ambrose, B.A.; Pelaz, S.; González, F.; Pabón-Mora, N. Comparative morphoanatomy and transcriptomic analyses reveal key factors controlling floral trichome development in Aristolochia (Aristolochiaceae). Journal of Experimental Botany 2023, 74, 6588–6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, L.; Goossens, A. Hormone-mediated promotion of trichome initiation in plants is conserved but utilizes species- and trichome-specific regulatory mechanisms. Plant Signaling and Behavior 2010, 5, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matías-Hernández, L.; Aguilar-Jaramillo, A.E.; Cigliano, R.A.; Sanseverino, W.; Pelaz, S. Flowering and trichome development share hormonal and transcription factor regulation. Journal of Experimental Botany 2016, 67, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, L.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.C.W.; Zhang, Y.; Reed, D.W.; Pollier, J.; Vande Casteele, S.R.F.; Inzé, D.; Covello, P.S.; Deforce, D.L.D.; Goossens, A. Dissection of the phytohormonal regulation of trichome formation and biosynthesis of the antimalarial compound artemisinin in Artemisia annua plants. New Phytologist 2011, 189, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traw, M.B.; Bergelson, J. Interactive effects of jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, and gibberellin on induction of trichomes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 2003, 133, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Klinkhamer, P.G.L.; Escobar-Bravo, R.; Leiss, K.A. Type VI glandular trichome density and their derived volatiles are differently induced by jasmonic acid in developing and fully developed tomato leaves: implications for thrips resistance. Plant Science 2018, 276, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, M.T.; Deseo, M.A.; O’Brien, M.; Clifton, J.; Bacic, A.; Doblin, M.S. Metabolomic analysis of methyl jasmonate treatment on phytocannabinoid production in Cannabis sativa. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Li, M.; Gu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Cai, S.; Guo, F.; et al. Deep learning-based quantification and transcriptomic profiling reveal a methyl jasmonate-mediated glandular trichome formation pathway in Cannabis sativa. The Plant Journal 2024, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, M.L.; De Almeida, M.; Rossi, M.L.; Martinelli, A.P.; Litholdo Junior, C.G.; Figueira, A.; Rampelotti-Ferreira, F.T.; Vendramim, J.D.; Benedito, V.A.; Pereira Peres, L.E. Brassinosteroids interact negatively with jasmonates in the formation of anti-herbivory traits in tomato. Journal of Experimental Botany 2009, 60, 4347–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janatová, A.; Fraňková, A.; Tlustoš, P.; Hamouz, K.; Božik, M.; Klouček, P. Yield and cannabinoids contents in different cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) genotypes for medical use. Industrial Crops and Products 2018, 112, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcke, G.U.; Bennewitz, S.; Bergau, N.; Athmer, B.; Henning, A.; Majovsky, P.; Jiménez-Gómez, J.M.; Hoehenwarter, W.; Tissier, A. Multi-omics of tomato glandular trichomes reveals distinct features of central carbon metabolism supporting high productivity of specialized metabolites. The Plant Cell 2017, 29, 960–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, N.; Guo, Q.; Purdy, S.J.; Nolan, M.; Halimi, R.A.; Mieog, J.C.; Barkla, B.J.; Kretzschmar, T. From dawn ‘til dusk: daytime progression regulates primary and secondary metabolism in Cannabis glandular trichomes. Journal of Experimental Botany 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A.; Tissier, A. Control of resource allocation between primary and specialized metabolism in glandular trichomes. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2022, 66, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, P.V.; Sands, L.B.; Ma, Y.; Berkowitz, G.A. Delineating genetic regulation of cannabinoid biosynthesis during female flower development in Cannabis sativa. Plant Direct 2022, 6, e412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, L.B.; Haiden, S.R.; Ma, Y.; Berkowitz, G.A. Hormonal control of promoter activities of Cannabis sativa prenyltransferase 1 and 4 and salicylic acid mediated regulation of cannabinoid biosynthesis. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 8620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, H.; Asrar, Z.; Szopa, J. Effects of ABA on primary terpenoids and Δ9- tetrahydrocannabinol in Cannabis sativa L. at flowering stage. Plant Growth Regulation 2009, 58, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, H.; Asrar, Z.; Mehrabani, M. Effects of gibberellic acid on primary terpenoids and Δ9 -tetrahydrocannabinol in Cannabis sativa at flowering stage. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2009, 51, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgel, L.; Hartung, J.; Schibano, D.; Graeff-Hönninger, S. Impact of different phytohormones on morphology, yield and cannabinoid content of Cannabis sativa L. Plants 2020, 9, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, H.; Salari, F.; Asrar, Z. Ethephon application stimulats cannabinoids and plastidic terpenoids production in Cannabis sativa at flowering stage. Industrial Crops and Products 2013, 46, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaskill, D.; Croteau, R. Monoterpene and sesquiterpene biosynthesis in glandular trichomes of peppermint (Mentha x piperita) rely exclusively on plastid-derived isopentenyl diphosphate. Planta 1995, 197, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaskill, D.; Gershenzon, J.; Croteau, R. Morphology and monoterpene biosynthetic capabilities of secretory cell clusters isolated from glandular trichomes of peppermint (Mentha piperita L.). Planta 1992, 187, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, E.E.; Caldelari, D.; Pearce, G.; Walker-Simmons, M.K.; Ryan, C.A. Diethyldithiocarbamic acid inhibits the octadecanoid signaling pathway for the eound induction of proteinase inhibitors in tomato leaves. Plant Physiology 1994, 106, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhuansun, X.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Krugman, T.; Sun, Q.; Xie, C. Exogenous sodium diethyldithiocarbamate, a jasmonic acid biosynthesis inhibitor, induced resistance to powdery mildew in wheat. Plant Direct 2020, 4, e00212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.-M. Cellular and Genetic Responses of Plants to Sugar Starvation. Plant Physiology 1999, 121, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Arsenault, J.; Vierling, E.; Kim, M. Mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit d, a component of the peripheral stalk, is essential for growth and heat stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 2021, 107, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatland, B.L.; Nikolau, B.J.; Wurtele, E.S. Reverse genetic characterization of cytosolic acetyl-CoA generation by ATP-citrate lyase in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2005, 17, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Fu, T.; Chen, N.; Guo, J.; Ma, J.; Zou, M.; Lu, C.; Zhang, L. The stromal chloroplast Deg7 protease participates in the repair of photosystem II after photoinhibition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 2010, 152, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harshavardhan, V.T.; Van Son, L.; Seiler, C.; Junker, A.; Weigelt-Fischer, K.; Klukas, C.; Altmann, T.; Sreenivasulu, N.; Bäumlein, H.; Kuhlmann, M. AtRD22 and AtUSPL1, members of the plant-specific BURP domain family involved in Arabidopsis thaliana drought tolerance. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e110065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, J.; Rico, S.; Corral, C.; Sánchez, C.; Vidal, N.; Martínez-Quesada, J.J.; Ferreiro-Vera, C. Exogenous application of stress-related signaling molecules affect growth and cannabinoid accumulation in medical cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.). Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, N.; Pereira Mendes, M.; Van Wees, S.C.M. Multiple levels of crosstalk in hormone networks regulating plant defense. The Plant Journal 2021, 105, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.-J.; Shimono, M.; Sugano, S.; Kojima, M.; Liu, X.; Inoue, H.; Sakakibara, H.; Takatsuji, H. Cytokinins act synergistically with salicylic acid to activate defense gene expression in rice. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2013, 26, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Gao, D.; Zhao, W.; Du, H.; Qiu, Z.; Huang, J.; Wen, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; et al. Cytokinin confers brown planthopper resistance by elevating jasmonic acid pathway in rice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, A.; Gan, Y. Progress on trichome development regulated by phytohormone signaling. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2011, 6, 1959–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhin, A.; Nawrath, C.; Hachez, C. Subtle interplay between trichome development and cuticle formation in plants. New Phytologist 2022, 233, 2036–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, S.J.; Bae, E.J.; Unda, F.; Hahn, M.G.; Mansfield, S.D.; Page, J.E.; Samuels, A.L. Cannabis glandular trichome cell walls undergo remodeling to store specialized metabolites. Plant and Cell Physiology 2021, 62, 1944–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, T.M.; Mañas-Fernández, A.; Zhao, L.; Kunst, L. Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM2 is a component of the fatty acid elongation machinery required for fatty acid extension to exceptional lengths. Plant Physiology, 2012; 160, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegebarth, D.; Buschhaus, C.; Wu, M.; Bird, D.; Jetter, R. The composition of surface wax on trichomes of Arabidopsis thaliana differs from wax on other epidermal cells. The Plant Journal 2016, 88, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegebarth, D.; Buschhaus, C.; Joubès, J.; Thoraval, D.; Bird, D.; Jetter, R. Arabidopsis ketoacyl-CoA synthase 16 (KCS16) forms C36/C38 acyl precursors for leaf trichome and pavement surface wax. Plant, Cell & Environment 2017, 40, 1761–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, D.; Roth, C.; Wiermer, M.; Fulda, M. Two activities of long-chain acyl-coenzyme A synthetase are involved in lipid trafficking between the endoplasmic reticulum and the plastid in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 2014, 167, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnurr, J.A.; Shockey, J.M.; de Boer, G.-J.; Browse, J.A. Fatty acid export from the chloroplast. Molecular characterization of a major plastidial acyl-coenzyme A synthetase from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 2002, 129, 1700–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnurr, J.; Shockey, J.; Browse, J. The acyl-CoA synthetase encoded by LACS2 is essential for normal cuticle development in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2004, 16, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Gong, Q.; Ma, Y.; Li, P.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; Yuan, L.; Yu, Y.; Pan, D.; Xu, F.; et al. cpSecA, a thylakoid protein translocase subunit, is essential for photosynthetic development in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 2010, 61, 1655–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summer, E.J.; Cline, K. Red bell pepper chromoplasts exhibit in vitro import competency and membrane targeting of passenger proteins from the thylakoidal sec and ΔpH pathways but not the chloroplast signal recognition particle pathway. Plant Physiology 1999, 119, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ouyang, M.; Lu, D.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, L. Protein sorting within chloroplasts. Trends in cell biology 2021, 31, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.G.L.; Schnell, D.J. Origins, function, and regulation of the TOC–TIC general protein import machinery of plastids. Journal of Experimental Botany 2019, 71, 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeger, T.S.; Watkins, K.P.; Friso, G.; van Wijk, K.J.; Barkan, A. A plant-specific RNA-binding domain revealed through analysis of chloroplast group II intron splicing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 4537–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Javed, H.U.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, C.; Jiu, S.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S. Improving berry quality and antioxidant ability in ‘Ruidu Hongyu’ grapevine through preharvest exogenous 2,4-epibrassinolide, jasmonic acid and their signaling inhibitors by regulating endogenous phytohormones. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzwieser, J.; Meischner, M.; Grün, M.; Yáñez-Serrano, A.M.; Fasbender, L.; Werner, C. Drought affects carbon partitioning into volatile organic compound biosynthesis in Scots pine needles. New Phytologist 2021, 232, 1930–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Van Herwijnen, Z.O.; Dräger, D.B.; Sui, C.; Haring, M.A.; Schuurink, R.C. SlMYC1 regulates type VI glandular trichome formation and terpene biosynthesis in tomato glandular cells. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 2988–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalvin, C.; Drevensek, S.; Dron, M.; Bendahmane, A.; Boualem, A. Genetic control of glandular trichome development. Trends in Plant Science 2020, 25, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewavitharana, A.K.; Gloerfelt-Tarp, F.; Nolan, M.; Barkla, B.J.; Purdy, S.; Kretzschmar, T. Simultaneous quantification of 17 cannabinoids in Cannabis inflorescence by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Separations 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Liu, L.; Rupasinghe, T.W.T.; Roessner, U.; Barkla, B.J. Salt stress alters membrane lipid content and lipid biosynthesis pathways in the plasma membrane and tonoplast. Plant Physiology 2022, 189, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. The Innovation 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Li, F.; Qin, Y.; Bo, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S. GOSemSim: an R package for measuring semantic similarity among GO terms and gene products. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).