Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

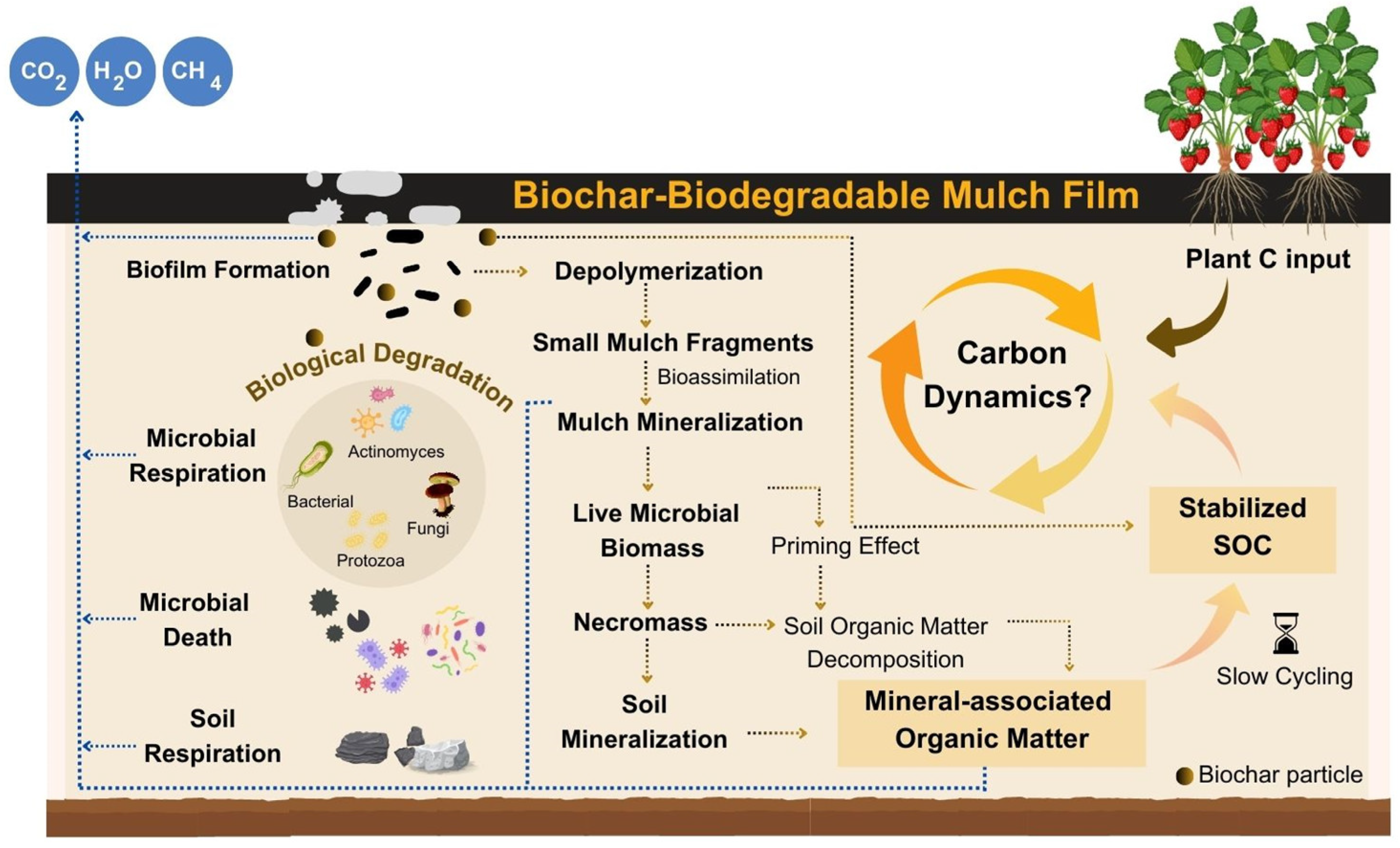

The pollution caused by plastic mulch film in agriculture has garnered significant attention. To safeguard the ecosystem from the detrimental effects of plastic pollution, it is imperative to investigate the use of biodegradable materials for manufacturing agricultural plastic film. Biochar has emerged as a feasible substance for the production of biodegradable mulch film (BDM), significantly improving providing agricultural soil benefits. Although biochar has been widely applied in the BDM manufacturing, the effect of biochar-filled plastic mulch film on soil carbon stock has not been well documented. This study provides an overview of the current stage of biochar incorporated with BDM and summarizes the possible pathway of biochar incorporated BDM on soil carbon stock contribution. The application of biochar incorporated BDM can lead to substantial changes in soil microbial diversity, thereby influencing the emissions of greenhouse gas. These alterations may ultimately yield unforeseen repercussions on the carbon cycles. In light of the current knowledge vacuum and potential challenges, additional study is necessary to ascertain if biochar incorporated BDM can effectively mitigate the issues of residual mulch film and microplastic contamination in agricultural land. However, significant progress remains necessary before BDM may fully supplant traditional agricultural mulch film in agricultural production.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

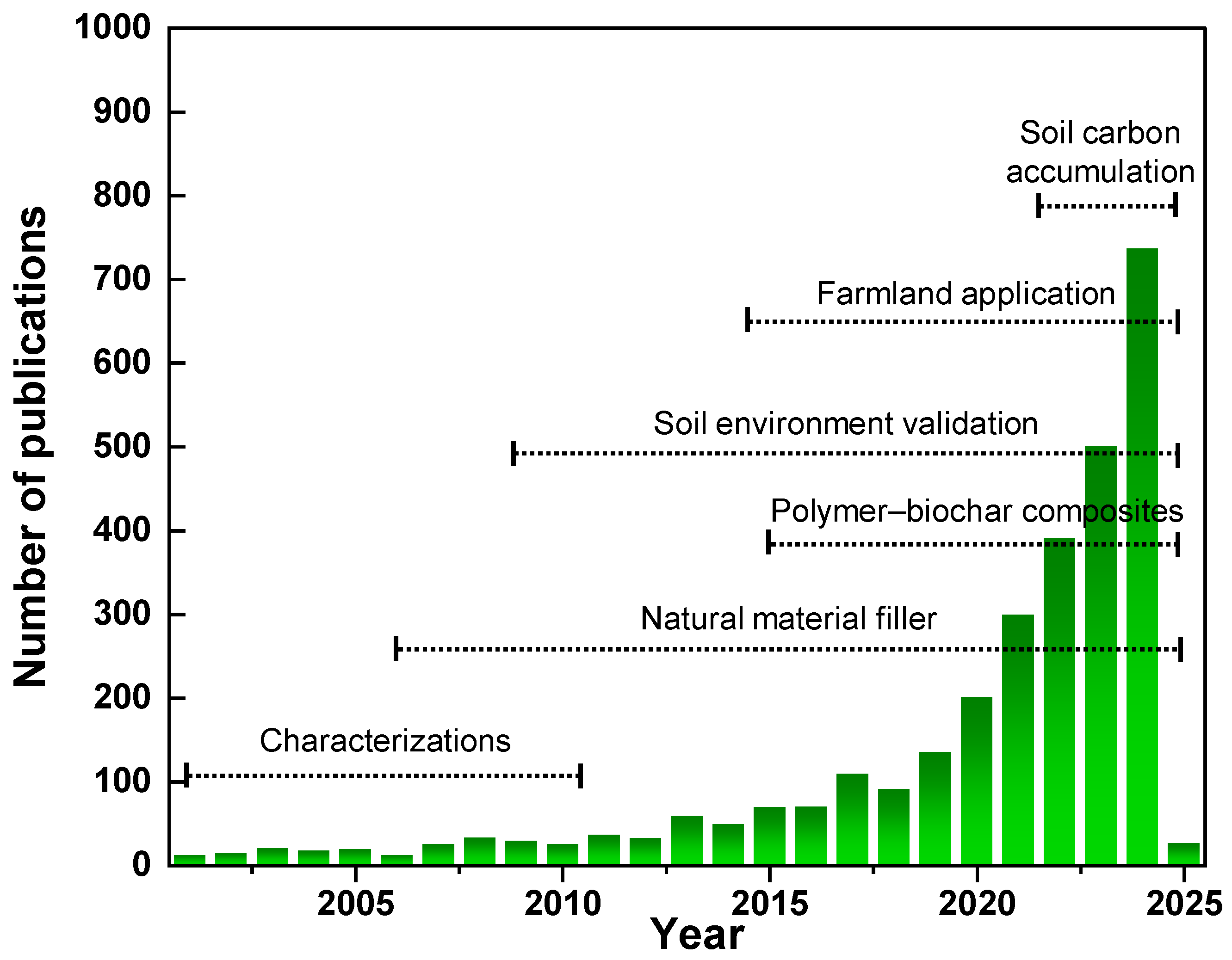

2. Quantitative Assessment of the Publications

3. Comparative Assessment of BDM Degradation in Soil

4. Biochar-Bioplastic Composite in Biodegradable Mulch Film

| Biochar feedstock | Biochar loading (wt %) | Base Polymer | Key finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy manure Wood chip |

10 | PCL PLA |

Biochar’s moisture content contributed to the hydrolytic degradation of the synthesized polymer. | [55] |

| Cassava rhizome Durian peel Pineapple peel Corncob |

0.25 | PLA | Carbon content in biochar improved mechanical properties (tensile elastic modulus and impact energy) of PLA/biochar composites. | [54] |

| Beechwood | 5 | PLA | Incorporating 5 wt% of biochar improved the composite’s tensile modulus of elasticity and strength. | [31] |

| Spent ground coffee | 1, 2.5, 5, and 7.5 | PLA | The content of BC highly influenced the ultimate properties of the PLA/BC biocomposites | [56] |

| Switchgrass | 12 | PLA | Biochar significantly enhanced the hydrophobicity and mechanical characteristics relative to the control film. | [57] |

| Wood chips | 10, 15, 20, and 30 | PBAT/PLA | The degradation time of the composites was prolonged by a biochar content exceeding 15 wt%, which was attributed to the entrapment of PLA and/or PBAT within the matrix. | [58] |

| Post-consumer food waste | 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 | PBAT/PLA | The degradation rate of PLA was significantly increased by biochar under composting conditions, resulting in a nearly doubled mass loss in samples with a high biochar content after 40 days compared to neat PLA. | [52] |

| Wood Sewage sludge |

10, 20 | PLA | The use of biochars in biocomposites resulted in a reduction of the mechanical characteristics and impact strength as compared to PLA. | [59] |

| Pelleted miscanthus straw | 1, 2.5, 5 | PBS | The disintegration rate of biocomposites through enzymatic hydrolysis increased as the biochar content increased. | [32] |

| Birch and beech wood | 5, 10, 20 | PBAT | The elastic modulus was improved by biochar, while the deformation values were maintained at a high level. | [53] |

| Carob waste | 10 and 20 | PBAT | The dispersion grade and compatibility of biochar particles within the PBAT matrix were outstanding. | [60] |

| Waste coffee grounds | 10, 20, and 30 | PCL | The modulus of elasticity and tensile strength were not significantly impacted by the addition of biochar, despite the fact that the elongation at break decreased. | [45] |

| Wood | 50 | PBAT | A comprehensive techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment indicated that biochar is currently not a viable choice in film production. | [60] |

5. Effects Biodegradable Mulch Film on Soil Carbon Dynamic

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Y. Fei et al., “Response of soil enzyme activities and bacterial communities to the accumulation of microplastics in an acid cropped soil,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 707, p. 135634, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Jin, J. Tang, H. Lyu, L. Wang, A. B. Gillmore, and S. M. Schaeffer, “Activities of Microplastics (MPs) in Agricultural Soil: A Review of MPs Pollution from the Perspective of Agricultural Ecosystems,” Apr. 13, 2022, American Chemical Society. [CrossRef]

- K. Malińska, A. Pudełko, P. Postawa, T. Stachowiak, and D. Dróżdż, “Performance of Biodegradable Biochar-Added and Bio-Based Plastic Clips for Growing Tomatoes,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 20, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Rosseto, D. D. C. Krein, N. P. Balbé, and A. Dettmer, “Starch–gelatin film as an alternative to the use of plastics in agriculture: a review,” Dec. 01, 2019, John Wiley and Sons Ltd. [CrossRef]

- A. A. de Souza Machado, W. Kloas, C. Zarfl, S. Hempel, and M. C. Rillig, “Microplastics as an emerging threat to terrestrial ecosystems,” Apr. 01, 2018, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “The effect of C:N ratio on heterotrophic nitrification in acidic soils,” Soil Biol Biochem, vol. 137, p. 107562, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xue et al., “Long-term mulching of biodegradable plastic film decreased fungal necromass C with potential consequences for soil C storage,” Chemosphere, vol. 337, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Bher, P. C. Mayekar, R. A. Auras, and C. E. Schvezov, “Biodegradation of Biodegradable Polymers in Mesophilic Aerobic Environments,” Oct. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Gul-E-Nayyab et al., “A Review on Biodegradable Composite Films Containing Organic Material as a Natural Filler,” J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Yin, Y. Li, H. Fang, and P. Chen, “Biodegradable mulching film with an optimum degradation rate improves soil environment and enhances maize growth,” Agric Water Manag, vol. 216, pp. 127–137, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Zumstein et al., “Biodegradation of synthetic polymers in soils: Tracking carbon into CO2 and microbial biomass,” Sci Adv, vol. 4, no. 7, p. eaas9024, 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Guliyev et al., “Degradation of Bio-Based and Biodegradable Plastic and Its Contribution to Soil Organic Carbon Stock,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 3, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. RameshKumar, P. Shaiju, K. E. O’Connor, and R. B. P, “Bio-based and biodegradable polymers - State-of-the-art, challenges and emerging trends,” Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem, vol. 21, pp. 75–81, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu et al., “It is still too early to promote biodegradable mulch film on a large scale: A bibliometric analysis,” Aug. 01, 2022, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- M. Velandia, A. Smith, A. Wszelaki, and T. Marsh, “The Economics of Adopting Biodegradable Plastic Mulch Films,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://ag.tennessee.edu/biodegradablemulch/Pages/biomulchprojects.aspx.

- J. Y. Chua, K. M. Pen, J. V. Poi, K. M. Ooi, and K. F. Yee, “Upcycling of biomass waste from durian industry for green and sustainable applications: An analysis review in the Malaysia context,” Jun. 01, 2023, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- J. H. R. Llanos and C. C. Tadini, “Preparation and characterization of bio-nanocomposite films based on cassava starch or chitosan, reinforced with montmorillonite or bamboo nanofibers,” Int J Biol Macromol, vol. 107, pp. 371–382, 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Trinetta, “Biodegradable Packaging,” in Reference Module in Food Science, Elsevier, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Sirivechphongkul et al., “Agri-Biodegradable Mulch Films Derived from Lignin in Empty Fruit Bunches,” Catalysts, vol. 12, no. 10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tan, Y. Yi, H. Wang, W. Zhou, Y. Yang, and C. Wang, “Physical and degradable properties of mulching films prepared from natural fibers and biodegradable polymers,” Applied Sciences, vol. 6, no. 5, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Merino, A. Y. Mansilla, T. J. Gutiérrez, C. A. Casalongué, and V. A. Alvarez, “Chitosan coated-phosphorylated starch films: Water interaction, transparency and antibacterial properties,” React Funct Polym, vol. 131, pp. 445–453, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Liling, Z. Di, X. Jiachao, G. Xin, F. Xiaoting, and Z. Qing, “Effects of ionic crosslinking on physical and mechanical properties of alginate mulching films,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 136, pp. 259–265, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Gao, C. Yan, Q. Liu, W. Ding, B. Chen, and Z. Li, “Effects of plastic mulching and plastic residue on agricultural production: A meta-analysis,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 651, pp. 484–492, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Pinpru, T. Charoonsuk, S. Khaisaat, O. Sawanakarn, N. Vittayakorn, and S. Woramongkolchai, “Synthesis and preparation of bacterial cellulose/calcium hydrogen phosphate composite film for mulching film application,” Mater Today Proc, vol. 47, pp. 3529–3536, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Stasi et al., “Biodegradable carbon-based ashes/maize starch composite films for agricultural applications,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 3, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. She et al., “Development of black and biodegradable biochar/gutta percha composite films with high stretchability and barrier properties,” Compos Sci Technol, vol. 175, pp. 1–5, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Luo et al., “Carbon Sequestration Strategies in Soil Using Biochar: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities,” Aug. 08, 2023, American Chemical Society. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie et al., “A critical review on production, modification and utilization of biochar,” J Anal Appl Pyrolysis, vol. 161, p. 105405, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Joseph et al., “How biochar works, and when it doesn’t: A review of mechanisms controlling soil and plant responses to biochar,” Nov. 01, 2021, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- M. Qiu et al., “Biochar for the removal of contaminants from soil and water: a review,” Dec. 01, 2022, Springer. [CrossRef]

- M. Zouari, D. B. Devallance, and L. Marrot, “Effect of Biochar Addition on Mechanical Properties, Thermal Stability, and Water Resistance of Hemp-Polylactic Acid (PLA) Composites,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 6, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Papadopoulou et al., “Synthesis and Study of Fully Biodegradable Composites Based on Poly(butylene succinate) and Biochar,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 4, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Li et al., “Liquid mulch films based on polysaccharide /furfural Schiff base adducts with pH-controlled degradability,” Ind Crops Prod, vol. 216, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Paustian, J. Lehmann, S. Ogle, D. Reay, G. P. Robertson, and P. Smith, “Climate-smart soils,” Nature, vol. 532, no. 7597, pp. 49–57, 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Guenet et al., “Can N2O emissions offset the benefits from soil organic carbon storage?,” Jan. 01, 2021, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Nazir et al., “Harnessing soil carbon sequestration to address climate change challenges in agriculture,” Mar. 01, 2024, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Dignac et al., “Increasing soil carbon storage: mechanisms, effects of agricultural practices and proxies. A review,” Apr. 01, 2017, Springer-Verlag France. [CrossRef]

- Y. D. Hernandez-Charpak, A. M. Mozrall, N. J. Williams, T. A. Trabold, and C. A. Diaz, “Biochar as a sustainable alternative to carbon black in agricultural mulch films,” Environ Res, vol. 246, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. De Prisco, B. Immirzi, M. Malinconico, P. Mormile, L. Petti, and G. Gatta, “Preparation, physico-chemical characterization, and optical analysis of polyvinyl alcohol-based films suitable for protected cultivation,” J Appl Polym Sci, vol. 86, no. 3, pp. 622–632, Oct. 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. M. K. T, R. N, A. A, S. Siengchin, V. R. A, and N. Ayrilmis, “Development and Analysis of Completely Biodegradable Cellulose/Banana Peel Powder Composite Films,” Journal of Natural Fibers, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 151–160, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Chen, J. Cui, W. Dong, and C. Yan, “Effects of Biodegradable Plastic Film on Carbon Footprint of Crop Production,” Agriculture (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 4, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Chen, N. Hu, Q. Zhang, H. Sun, and L. Zhu, “Effects of Biodegradable Plastic Film Mulching on the Global Warming Potential, Carbon Footprint, and Economic Benefits of Garlic Production,” Agronomy, vol. 14, no. 3, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Das, A. K. Sarmah, and D. Bhattacharyya, “A novel approach in organic waste utilization through biochar addition in wood/polypropylene composites,” Waste Management, vol. 38, pp. 132–140, 2015. [CrossRef]

- O. Das, A. K. Sarmah, and D. Bhattacharyya, “Biocomposites from waste derived biochars: Mechanical, thermal, chemical, and morphological properties,” Waste Management, vol. 49, pp. 560–570, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Diaz, R. K. Shah, T. Evans, T. A. Trabold, and K. Draper, “Thermoformed containers based on starch and starch/coffee waste biochar composites,” Energies (Basel), vol. 13, no. 22, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Brodhagen, M. Peyron, C. Miles, and D. A. Inglis, “Biodegradable plastic agricultural mulches and key features of microbial degradation,” Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 99, pp. 1039–1056, 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Arias, C. Piattoni, S. Guerrero, and A. Iglesias, “Biochemical Mechanisms for the Maintenance of Oxidative Stress Under Control in Plants,” in Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress, Third Edition, 2011, pp. 157–190.

- R. Gattin, A. Copinet, C. Bertrand, and Y. Couturier, “Comparative Biodegradation Study of Starch-and Polylactic Acid-Based Materials,” 2001. [CrossRef]

- R. Hatti-Kaul, L. J. Nilsson, B. Zhang, N. Rehnberg, and S. Lundmark, “Designing Biobased Recyclable Polymers for Plastics,” Trends Biotechnol, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 50–67, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Zheng and S. Suh, “Strategies to reduce the global carbon footprint of plastics,” Nat Clim Chang, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 374–378, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Bartoli, R. Arrigo, G. Malucelli, A. Tagliaferro, and D. Duraccio, “Recent Advances in Biochar Polymer Composites,” Jun. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- S. Kane and C. Ryan, “Biochar from food waste as a sustainable replacement for carbon black in upcycled or compostable composites,” Composites Part C: Open Access, vol. 8, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Botta, R. Teresi, V. Titone, G. Salvaggio, F. P. La Mantia, and F. Lopresti, “Use of biochar as filler for biocomposite blown films: Structure-processing-properties relationships,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 22, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Aup-Ngoen and M. Noipitak, “Effect of carbon-rich biochar on mechanical properties of PLA-biochar composites,” Sustain Chem Pharm, vol. 15, p. 100204, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. D. Hernandez-Charpak, T. A. Trabold, C. L. Lewis, and C. A. Diaz, “Biochar-filled plastics: Effect of feedstock on thermal and mechanical properties,” Biomass Convers Biorefin, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 4349–4360, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Arrigo, M. Bartoli, and G. Malucelli, “Poly(lactic Acid)-biochar biocomposites: Effect of processing and filler content on rheological, thermal, and mechanical properties,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 4, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Bajwa, S. Adhikari, J. Shojaeiarani, S. G. Bajwa, P. Pandey, and S. R. Shanmugam, “Characterization of bio-carbon and ligno-cellulosic fiber reinforced bio-composites with compatibilizer,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 204, pp. 193–202, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Musioł et al., “(Bio)degradable biochar composites – Studies on degradation and electrostatic properties,” Materials Science and Engineering: B, vol. 275, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Pudełko, P. Postawa, T. Stachowiak, K. Malińska, and D. Dróżdż, “Waste derived biochar as an alternative filler in biocomposites - Mechanical, thermal and morphological properties of biochar added biocomposites,” J Clean Prod, vol. 278, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Infurna et al., “Biochar Particles Obtained from Agricultural Carob Waste as a Suitable Filler for Sustainable Biocomposite Formulations,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 15, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Bandopadhyay, L. Martin-Closas, A. M. Pelacho, and J. M. DeBruyn, “Biodegradable plastic mulch films: Impacts on soil microbial communities and ecosystem functions,” Apr. 26, 2018, Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- B. Singh and N. Sharma, “Mechanistic implications of plastic degradation,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 93, no. 3, pp. 561–584, 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Devi, P. Pandey, and G. D. Sharma, “Plant growth-promoting endophyte Serratia marcescens AL2-16 enhances the growth of Achyranthes aspera L., a medicinal plant,” Hayati, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 173–180, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huo, F. A. Dijkstra, M. Possell, and B. Singh, “Mineralisation and priming effects of a biodegradable plastic mulch film in soils: Influence of soil type, temperature and plastic particle size,” Soil Biol Biochem, vol. 189, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Ding, M. Flury, S. M. Schaeffer, Y. Xu, and J. Wang, “Does long-term use of biodegradable plastic mulch affect soil carbon stock?,” Dec. 01, 2021, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Gabriel, L. Kellman, and D. Prest, “Examining mineral-associated soil organic matter pools through depth in harvested forest soil profiles,” PLoS One, vol. 13, no. 11, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cao et al., “Labile and refractory fractions of sedimentary organic carbon off the Changjiang Estuary and its implications for sedimentary oxygen consumption,” Front Mar Sci, vol. 9, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Ding, M. Flury, S. M. Schaeffer, Y. Xu, and J. Wang, “Does long-term use of biodegradable plastic mulch affect soil carbon stock,” Resour. Conserv. Recycl, vol. 175, no. 105895.10, p. 1016, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Hayes et al., “Effect of diverse weathering conditions on the physicochemical properties of biodegradable plastic mulches,” Polym Test, vol. 62, pp. 454–467, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. M. Semida et al., “Biochar implications for sustainable agriculture and environment: A review,” Dec. 01, 2019, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- I. Saleem et al., “Chapter 13 - Biochar and microbes for sustainable soil quality management,” in Microbiome Under Changing Climate, A. Kumar, J. Singh, and L. F. R. Ferreira, Eds., Woodhead Publishing, 2022, pp. 289–311. [CrossRef]

- B. Li et al., “Global integrative meta-analysis of the responses in soil organic carbon stock to biochar amendment,” J Environ Manage, vol. 351, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Jia et al., “Effects of LDPE and PBAT plastics on soil organic carbon and carbon-enzymes: A mesocosm experiment under field conditions,” Environmental Pollution, vol. 362, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu et al., “Biochar-plant interactions enhance nonbiochar carbon sequestration in a rice paddy soil,” Commun Earth Environ, vol. 4, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Ding, G. Li, X. Zhao, Q. Lin, and X. Wang, “Biochar application significantly increases soil organic carbon under conservation tillage: an 11-year field experiment,” Biochar, vol. 5, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Tomczyk, Z. Sokołowska, and P. Boguta, “Biochar physicochemical properties: pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects,” Mar. 01, 2020, Springer. [CrossRef]

- S. Li and D. Tasnady, “Biochar for Soil Carbon Sequestration: Current Knowledge, Mechanisms, and Future Perspectives,” Sep. 01, 2023, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Y. Kuzyakov, I. Bogomolova, and B. Glaser, “Biochar stability in soil: Decomposition during eight years and transformation as assessed by compound-specific 14C analysis,” Soil Biol Biochem, vol. 70, pp. 229–236, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tang, F. Zuo, C. Li, Q. Zhang, W. Gao, and J. Cheng, “Combined effects of biochar and biodegradable mulch film on chromium bioavailability and the agronomic characteristics of tobacco,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhou et al., “The long-term uncertainty of biodegradable mulch film residues and associated microplastics pollution on plant-soil health,” Jan. 15, 2023, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- M. Menossi, M. Cisneros, V. A. Alvarez, and C. Casalongué, “Current and emerging biodegradable mulch films based on polysaccharide bio-composites. A review,” Agron Sustain Dev, no. 41, p. 53, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Bandopadhyay, L. Martin-Closas, A. M. Pelacho, and J. M. DeBruyn, “Biodegradable plastic mulch films: impacts on soil microbial communities and ecosystem functions,” Front Microbiol, vol. 9, p. 819, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhang et al., “Effect of Long-Term Biodegradable Film Mulch on Soil Physicochemical and Microbial Properties,” Toxics, vol. 3, no. 10, p. 129, 2022. [CrossRef]

| Classification of polymer | Polymer-based agricultural mulches | Comparative assessment of biodegradation in soil1 |

| Bio-based | Thermoplastic starch | High |

| Chemically modified starch | High | |

| Cellulose | Moderately high | |

| PLA | Low | |

| Fossil-based | PHB | Moderate |

| PHV | Moderate | |

| PBAT | Low moderate | |

| PBSA | Low moderate | |

| PCL | Low moderate | |

| PBS | Low moderate | |

| PTT | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).