Submitted:

13 November 2024

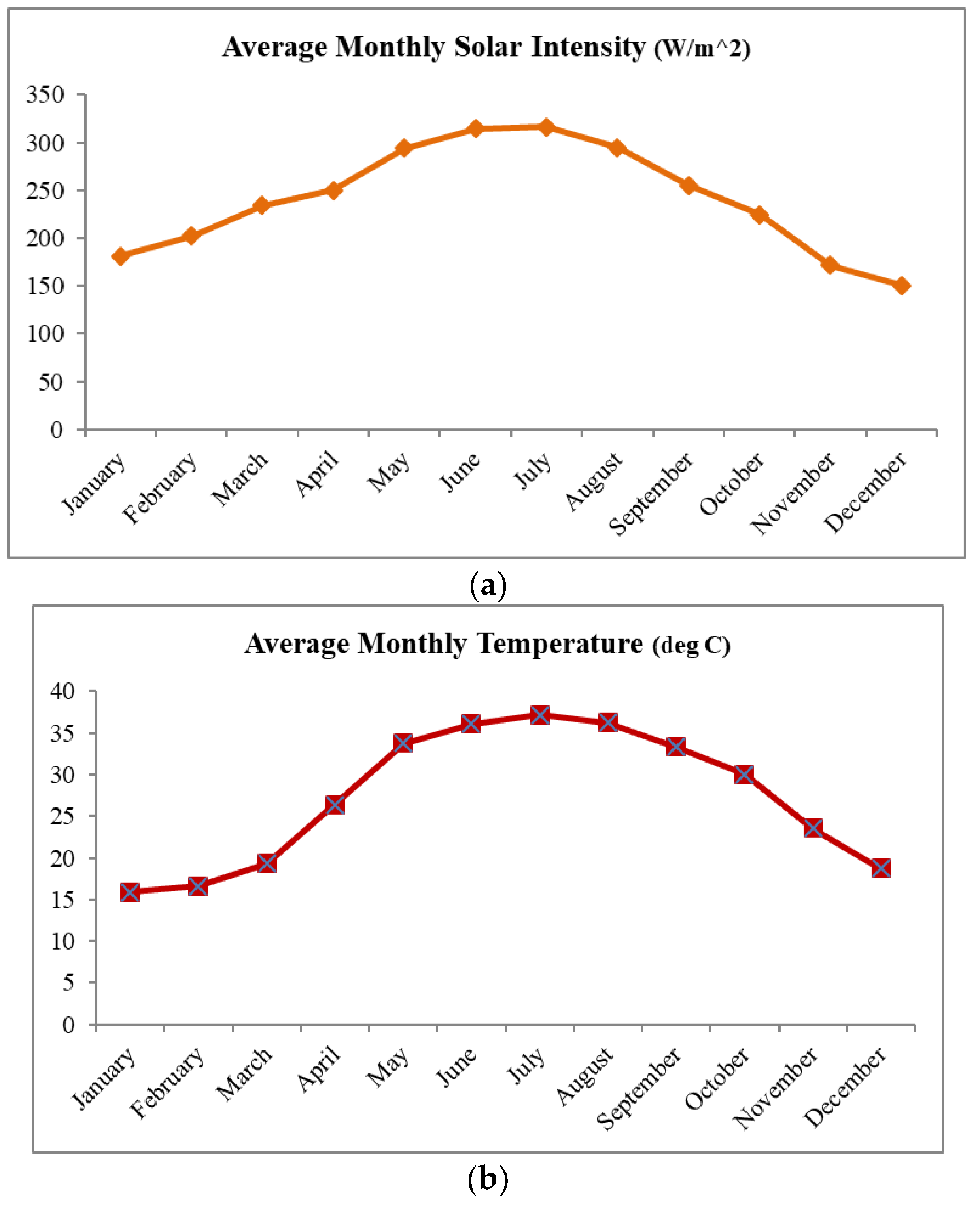

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Weathering of WPCs

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

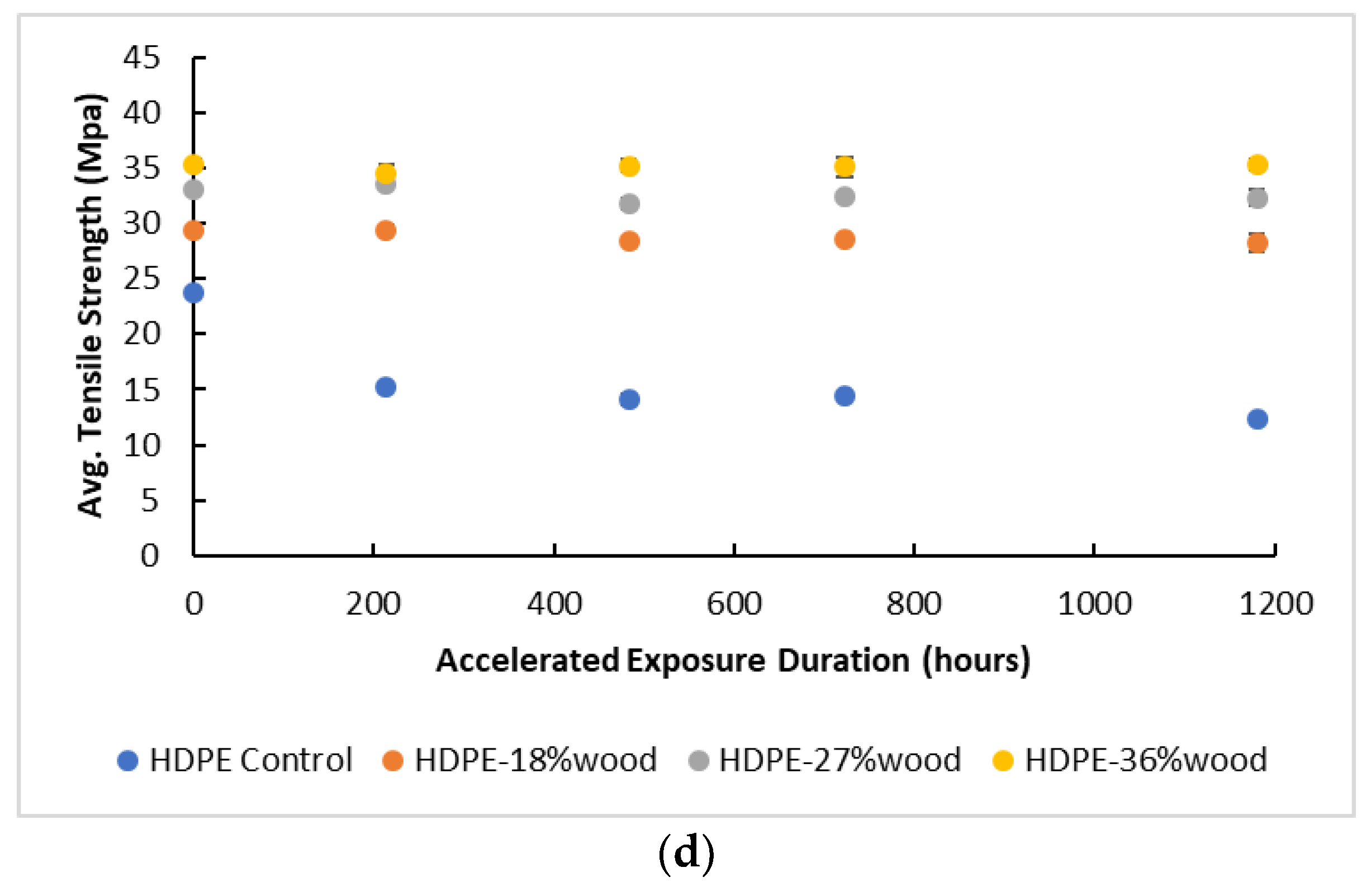

3.1. Tensile Properties

3.2. Hardness Properties

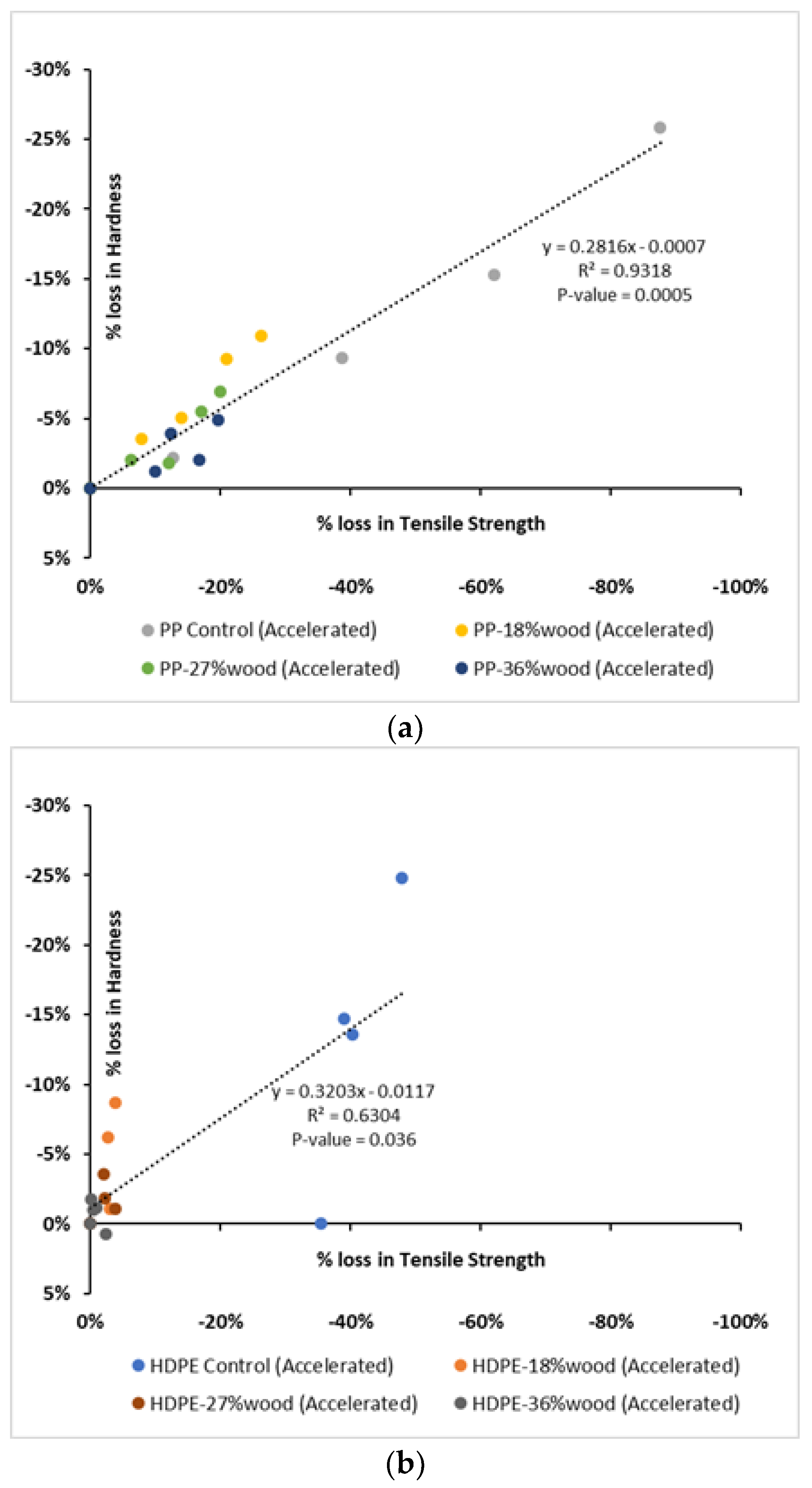

3.3. Tensile Strength versus Surface Hardneses

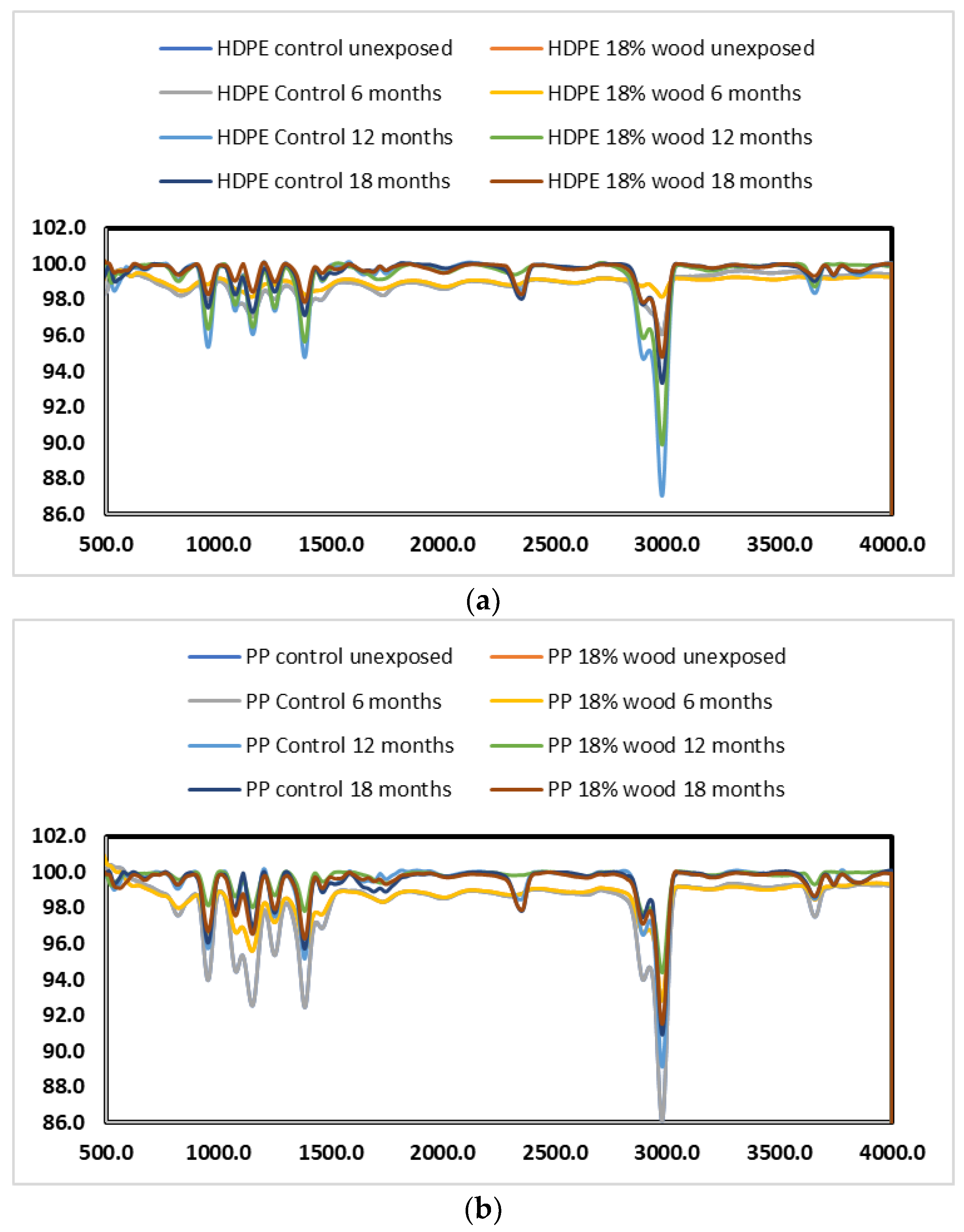

3.4. FTIR Characterization

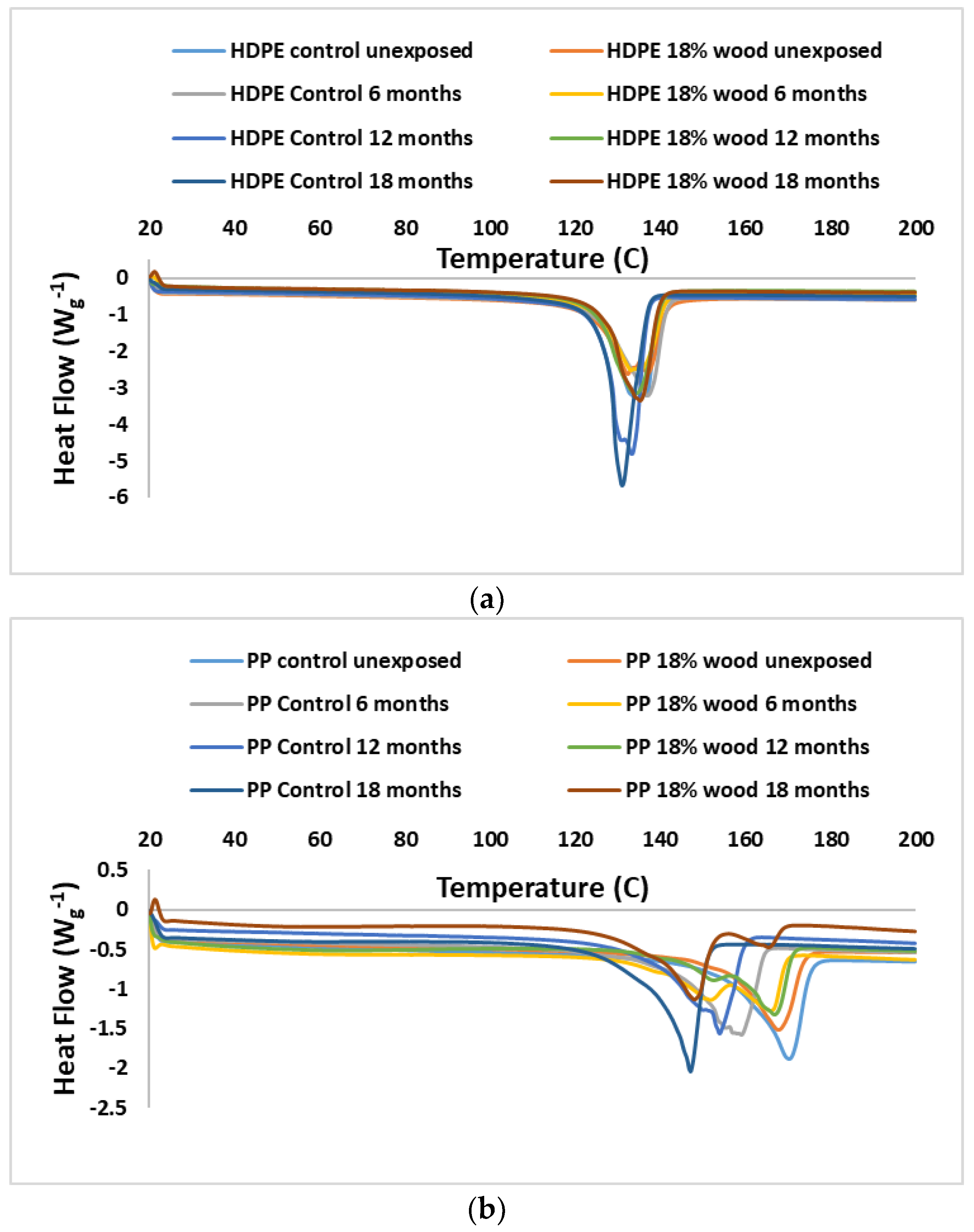

3.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

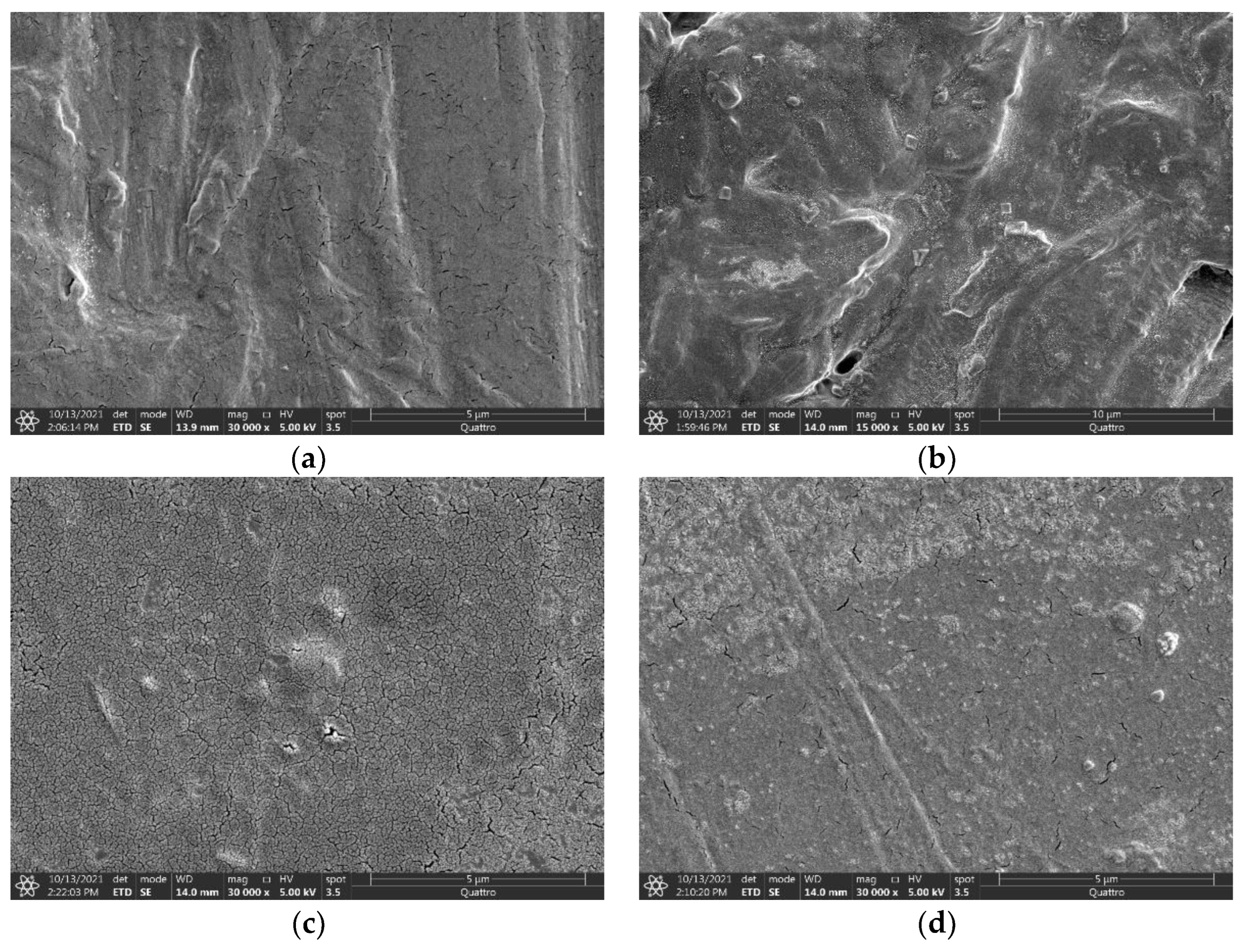

3.6. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

3.7. Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2020. Paris, International Energy Agency. 2020. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2020.

- Balu R.; Dutta N.K.; Roy Choudhury N. Plastic Waste Upcycling: A Sustainable Solution for Waste Management, Product Development, and Circular Economy 2022, Polymers (Basel), Nov 8;14(22):4788.

- Kassab A.; Al Nabhani D.; Mohanty P.; Pannier C.; Ayoub G.Y. Advancing Plastic Recycling: Challenges and Opportunities in the Integration of 3D Printing and Distributed Recycling for a Circular Economy 2023, Polymers (Basel), Sep 25;15(19):3881. [CrossRef]

- Gamboa C. Towards zero-carbon building In Climate 2020. UNA-UK Publication.

- Rowell R.M. Understanding Wood Surface Chemistry and Approaches to Modification: A Review 2021, Polymers, 13(15):2558. [CrossRef]

- Kučerová V.; Hrčka R.; Hýrošová T. Relation of Chemical Composition and Colour of Spruce Wood 2022, Polymers (Basel), Dec 6;14(23):5333. [CrossRef]

- Kumar B.G.; Singh R.P.; Nakamura T. Degradation of carbon fiber-reinforced epoxy composites by ultraviolet radiation and condensation 2002, J. Compos. Mater., 36:2713–2732. [CrossRef]

- Broda M.; Popescu C.M.; Curling S.F.; Timpu D.I.; Ormondroyd G.A. Effects of Biological and Chemical Degradation on the Properties of Scots Pine Wood-Part I: Chemical Composition and Microstructure of the Cell Wall 2022, Materials (Basel), Mar 22;15(7):2348. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, D. Thermoplastic moulding of Wood-Polymer Composites (WPC): A review on physical and mechanical behaviour under hot-pressing technique. Compos. Struct. 2021, 262, 113649. [CrossRef]

- Muller, U.; Veigel, S. The strength and stiffness of oriented wood and cellulose-fiber materials: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 125, 100916.

- Smith, P.M.; Wolcott, M.P. Opportunities for Wood/Natural Fiber-Plastic Composites in Residential and Industrial applications. For. Prod. J. 2006, 56, 4–11.

- Gardner, D.; Han, Y.; Song, W. Wood plastic composites technology trends. In Proceedings of the 51st International Convention of Society of Wood.

- Olonisakin, K.; He, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, R.; Yang, W. Influence of stacking sequence on mechanical properties and moisture absorption of epoxy-based woven flax and basalt fabric hybrid composites. Sustain. Struct. 2022, 2, 16. [CrossRef]

- Panthapulakkal, S.; Zereshkian, A.; Saim, M. Preparation and characterization of wheat straw fibers for reinforcing application in injection molded thermoplastic composites. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 265–272. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yao, X.; Khanal, S.; Xu, S. A novel surface treatment for bamboo flour and its effect on the dimensional stability and mechanical properties of high-density polyethylene/bamboo flour composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 1220–1227. [CrossRef]

- Oladejo, K.O.; Omoniyi, T.E. Dimensional Stability and Mechanical Properties of Wood Plastic Composites Products from Sawdust of Anogeissus leiocarpus (Avin) with Recycled Polyethylene Teraphthalate (PET) Chips. Eur. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. Res. 2017, 5, 28–33.

- Najafi, S.K. Use of Recycled Plastics in Wood Plastic Composites—A Review. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1898–1905. [CrossRef]

- Binhussain, M.A.; El-Tonsy, M.M. Palm leave and plastic waste wood composite for out-door structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 1431–1435. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.H.; Deviatkin, I.; Havukainen, J.; Horttanainen, M. Environmental impacts of wooden, plastic, and wood-polymer composite pallet: A life cycle assessment approach. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1607–1622. [CrossRef]

- Ratanawilai, T.; Taneerat, K. Alternative polymeric matrices for wood-plastic composites: Effects on mechanical properties and resistance to natural weathering. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 349–357. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhao, M.; Chang, G.; Hu, X.; Guo, Q. A composite obtained from waste automotive plastics and sugarcane skin flour: Mechanical properties and thermo-chemical analysis. Powder Technol. 2019, 347, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Dauletbek, A.; Li, H.; Xiong, Z.; Lorenzo, R. A review of mechanical behavior of structural laminated bamboo lumber. Sustain. Struct. 2021, 1, 4. [CrossRef]

- Grubbström, G.; Holmgren, A.; Oksman, K. Silane-crosslinking of recycled low-density polyethylene/wood composites—ScienceDirect. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2010, 41, 678–683.

- Oladejo, K.O.; Omoniyi, T.E. Dimensional Stability and Mechanical Properties of Wood Plastic Composites Produced from Sawdust of Anogeissus leiocarpus (Ayin) with Recycled Polyethylene Teraphthalate (PET) ChipsEur J Appl Eng Scientific Res, 5 (2017), pp. 28-33.

- Carus, M., Eder, A. WPC and NFC market trends, bioplastics Magazine 10 (2015) 12-13.

- Nevin G.K.; Ayse A. Effects of maleated polypropylene on the morphology, thermal and mechanical properties of short carbon fiber reinforced polypropylene composites, Materials & Design, Volume 32, Issue 7, 2011, Pages 4069-4073.

- Pickering, K.; Efendy, M.A.; Le, T. A review of recent developments in natural fibre composites and their mechanical performance. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 83, 98–112. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Razavi-Nouri, Masoud Tayefi, Alireza Sabet, Morphology development and thermal degradation of dynamically cured ethylene-octene copolymer/organoclay nanocomposites, Thermochimica Acta, 655, (2017), 302-312. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Zhang, Z., Song, K., Lee, S., Chun, S.-J., Zhou, D., and Wu, Q. Effect of durability treatment on ultraviolet resistance, strength, and surface wettability of wood plastic composite, BioRes. 2014, 9(2), 3591-3601. [CrossRef]

- Stark, N. M. (2007). Considerations in the weathering of wood-plastic composites. In Proceedings: 3rd Wood Fibre Polymer Composites International Symposium: Innovative Sustainable Materials Applied to Building and Furniture: March 26-27, 2007... Bordeaux, France. [Sl: sn], 2007: 10 pages.

- Teacă, C.-A.; Roşu, D.; Bodîrlău, R.; and Roşu, L. Structural changes in wood under artificial UV light irradiation determined by FTIR spectroscopy and color measurements - A brief review, BioRes. 2013, 8(1), 1478-1507. [CrossRef]

- Doğan M. Ultraviolet light accelerates the degradation of polyethylene plastics. Microsc Res Tech. 2021, Nov;84(11):2774-2783. [CrossRef]

- Hon D.N.S. Wood and Cellulosic Chemistry, Marcel Dekker, Inc., 2001.

- Selden R.; Nystrom B.; Langstrom R. UV aging of polypropylene/wood fiber composites. Polymer Composites 2004, 25 (5): 543–53.

- Beg M.; Pickering K. Accelerated weathering of unbleached kraft wood fibre reinforced polypropylene composites. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2008, 93: 1939–46.

- Mantia F.; Morreale M. Accelerated weathering of polypropylene/wood flour composites. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2008, 93: 1252–58.

- Soccalingame L.; Rerrin D.; Benezet J. Reprocessing of artificial UV weathered wood flour reinforced polypropylene composites. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2015, 120: 313–27. [CrossRef]

- Phiriyawirut M.; Seenpung P.; Calermboom S. Isostatic polypropylene/wood sawdust composite: Effects of natural weathering, water immersion and Ga,,a-Ray Irradiation on Mechanical Properties. Macromolecular Symposia 2008.

- Darabi P.; Karimi A.N.; Mirshokraie S.A.; Thévenon M.F. Lignin blocking effects on weathering process of wood plastic composites. Conference paper: 41st Annual Meeting of the International Research Group on Wood Protection, Biarritz, France, 9-13 May 2010, 2010, IRG-WP 10-40529.

- Lei Z.; Liu J.; Zhang Z.; Zhao X; Li Q. Study on Preparation and Properties of Anti-Ultraviolet Aging Wood-Plastic Composites. Wood Research 2023, 68 (4), 680-691 pp.

- Redhwi, H.H.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Andrady, A.L.; Furquan, S.A.; Hussain, S. Durability of High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) and Polypropylene (PP) based Wood-Plastic Composites Part 1: Mechanical Properties of the Composite Materials, J. Comps. Sci. 2023, 7, 163. [CrossRef]

- Wood Plastic Composites Market Size. Share & Trend Analysis Report by Product (Polyethylene, Polypropylene), by Application (Automotive Components), by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2022–2030; Report ID: 978-1-68038-849-7; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022; p. 198.

- Umar A.H; Zainudin E.S; Sapuan S.M Effect of Accelerated Weathering n Tensile Properties of Kenaf Reinforced High-Density Polyethylene Composites. Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Sciences (JMES) 2012, ISSN (Print): 2289-4659, Volume 2, pp. 198-205.

- Hung K.C.; Chang W.C.; Xu J.W.; Wu T.L.; Wu J.H. Comparison of the Physico-Mechanical and Weathering Properties of Wood-Plastic Composites Made of Wood Fibers from Discarded Parts of Pomelo Trees and Polypropylene. Polymers (Basel) 2021, Aug 11;13(16):2681.

- Beg M.D.H.; Pickering K.L.; Accelerated weathering of unbleached and bleached Kraft wood fibre reinforced polypropylene composites. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2008, Volume 93, Issue 10, Pages 1939-1946.

- Gunjal J.; Aggarwal P.; Chauhan S. Changes in colour and mechanical properties of wood polypropylene composites on natural weathering. Maderas, Cienc. tecnol. [online]. 2020, vol.22, n.3 [cited 2024-04-25], pp.325-334. [CrossRef]

- López-Naranjo E.J.; Alzate-Gaviria L.M.; Hernández-Zárate G.; Reyes-Trujeque J.; Cruz-Estrada R.H. Effect of accelerated weathering and termite attack on the tensile properties and aesthetics of recycled HDPE-pinewood composites. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2014, 27(6):831-844. [CrossRef]

- Stark N.M.; Matuana L.M.; Clemons C.M. Effect of processing method on surface and weathering characteristics of wood-flour/HDPE composites. J. Appl Polym Sci 2004, 93, pp. 1021-1030. [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, E.; Chrysafi, I.; Polychronidis, P.; Zamboulis, A.; Bikiaris, D.N. Evaluation of Eco-Friendly Hemp-Fiber-Reinforced Recycled HDPE Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 138. [CrossRef]

- Li J.; Huo R.; Liu W.; Fang H.; Jiang L.; Zhou D. Mechanical properties of PVC-based wood–plastic composites effected by temperature. Front. Mater. 2022, 9:1018902.

- Grause G.; Chien M.F.; Inoue C. Changes during the weathering of polyolefins. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2020, Volume 181, 109364, ISSN 0141-3910. [CrossRef]

- Oluwoye I.; Altarawneh M.; Gore J.; Dlugogorski B.Z. Oxidation of crystalline polyethylene. Combustion and Flame 2015, Volume 162, Issue 10, Pages 3681-3690. [CrossRef]

- Kanbayashi T.; Matsunaga M.; Kobayashi M. Cellular-level chemical changes in Japanese beech (Fagus crenata Blume) during artificial weathering. J. Holzforschung 2021, De Gruyter (online). [CrossRef]

- Andrady A.L.; Barnes P.W.; Bornman J.F.; Gouin T.; Madronich S.; White C.C.; Zepp R.G.; Jansen M.A.K. Oxidation and fragmentation of plastics in a changing environment; from UV-radiation to biological degradation. Sci Total Environ. 2022, Dec 10, 851(Pt 2):158022. [CrossRef]

- Homkhiew C.; Ratanawilai T.; Thongruang W. Effects of natural weathering on the properties of recycled polypropylene composites reinforced with rubberwood flour, Industrial Crops and Products 2014, Volume 56, Pages 52-59. [CrossRef]

- Nukala S.G.; Kong I.; Kakarla A.B.; Kong W.; Kong W. Development of wood polymer composites from recycled wood and plastic waste: thermal and mechanical properties J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, p. 194.

- Srivabut C.; Homkhiew C.; Rawangwong S.; Boonchouytan W. Possibility of using municipal solid waste for manufacturing wood plastic composites: effects of natural weathering, wood waste types, and contents. J. Mater. Cycles. Waste. Manag. 2022, 24, pp. 1407-1422.

- Srivabut C.; Khamtree S.; Homkhiew C.; Ratanawilai T.; Rawangwong S. Comparative effects of different coastal weathering on the thermal, physical, and mechanical properties of rubberwood–latex sludge flour reinforced with polypropylene hybrid composites, Composites Part C: Open Access 2023, Volume 12, 100383.

| Outdoor Exposure Duration | Average Hardness Value [Std. Dev.] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDPE Control | HDPE-18% wood | HDPE-27% wood | HDPE- 36% wood | |

| Unexposed | 63.2 [0.1] | 65.8 [0.2] | 66.7 [0.4] | 68.3 [0.6] |

| 6 months | 56.9 [2.1] | 67.5 [0.3] | 66.4 [0.4] | 68.5 [2.0] |

| 12 months | 56.4 [2.3] | 63.4 [0.8] | 63.6 [1.2] | 67.6 [0.2] |

| 18 months | 56.3 [1.7] | 62.9 [1.7] | 61.2 [0.7] | 64.4 [0.7] |

| Outdoor Exposure Duration | Average Hardness Value [Std. Dev.] | |||

| PP Control | PP-18% wood | PP-27% wood | PP- 36% wood | |

| Unexposed | 73.9 [0.8] | 73.4 [1.0] | 73.3 [0.6] | 73.9 [1.1] |

| 6 months | 67.8 [1.1] | 68.0 [1.7] | 69.8 [0.8] | 68.1 [1.3] |

| 12 months | 68.1 [0.6] | 67.4 [1.2] | 68.1 [1.2] | 69.5 [0.8] |

| 18 months | 60.1 [2.1] | 60.8 [1.9] | 65.3 [1.5] | 67.8 [2.1] |

| Accelerated Exposure Duration | Average Hardness Value [Std. Dev.] | |||

| HDPE Control | HDPE-18% wood | HDPE-27% wood | HDPE- 36% wood | |

| 214 hours | 63.2 [1.2] | 64.4 [0.8] | 66.0 [1.3] | 68.8 [1.1] |

| 483 hours | 54.6 [2.6] | 65.1 [1.4] | 66.0 [1.3] | 67.6 [2.1] |

| 723 hours | 53.9 [1.0] | 61.7 [3.0] | 64.3 [1.6] | 67.5 [1.0] |

| 1180 hours | 47.5 [2.8] | 60.1 [1.1] | 65.5 [0.7] | 67.1 [1.5] |

| Accelerated Exposure Duration | Average Hardness Value [Std. Dev.] | |||

| PP Control | PP-18% wood | PP-27% wood | PP- 36% wood | |

| 214 hours | 72.3 [1.2] | 70.8 [1.0] | 71.8 [1.4] | 73.0 [0.8] |

| 483 hours | 67.0 [0.7] | 69.7 [1.5] | 72.0 [1.3] | 71.0 [1.7] |

| 723 hours | 62.6 [1.5] | 66.6 [1.9] | 69.3 [1.1] | 72.4 [1.0] |

| 1180 hours | 54.8 [1.0] | 65.4 [3.5] | 68.2 [2.4] | 70.3 [0.8] |

| Outdoor Exposure Duration | Material | Tensile Strength (Mpa) | % elongation at break | Modulus of Elasticity (Mpa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | ||

| Unexposed | HDPE Control | 23.67 | 0.23 | 1011.87 | 3.68 | 619.01 | 35.89 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 29.35 | 0.79 | 24.53 | 3.53 | 1010.31 | 51.08 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 33.05 | 0.84 | 13.75 | 1.52 | 1226.15 | 38.98 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 35.36 | 0.79 | 9.45 | 0.90 | 1461.73 | 56.92 | |

| PP Control | 37.84 | 0.18 | 43.15 | 7.41 | 991.73 | 3.07 | |

| PP-18% wood | 38.42 | 0.38 | 9.52 | 0.57 | 1370.90 | 12.70 | |

| PP-27% wood | 38.73 | 0.30 | 6.93 | 0.36 | 1553.33 | 42.83 | |

| PP-36% wood | 38.77 | 0.63 | 5.87 | 0.21 | 1712.30 | 14.51 | |

| 6 Months | HDPE Control | 4.67 | 0.99 | 5.34 | 7.01 | 969.82 | 39.14 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 28.50 | 0.99 | 13.78 | 1.60 | 1051.20 | 44.41 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 31.97 | 0.76 | 11.05 | 0.91 | 1264.55 | 45.03 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 34.47 | 0.60 | 8.05 | 0.34 | 1494.55 | 36.63 | |

| PP Control | 16.70 | 1.75 | 2.40 | 0.39 | 1052.09 | 5.26 | |

| PP-18% wood | 31.83 | 0.35 | 6.93 | 0.40 | 1295.30 | 28.43 | |

| PP-27% wood | 33.38 | 0.18 | 5.74 | 0.15 | 1492.23 | 22.43 | |

| PP-36% wood | 33.38 | 0.24 | 4.92 | 0.17 | 1651.79 | 27.03 | |

| 12 Months | HDPE Control | 4.41 | 0.99 | 1.55 | 0.55 | 776.78 | 20.32 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 25.20 | 0.85 | 11.70 | 0.53 | 1004.87 | 32.70 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 29.82 | 0.49 | 8.70 | 0.80 | 1244.91 | 28.31 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 32.35 | 0.55 | 7.86 | 0.25 | 1443.60 | 40.78 | |

| PP Control | 9.57 | 0.20 | 1.55 | 0.06 | 833.50 | 21.66 | |

| PP-18% wood | 28.02 | 0.53 | 7.18 | 0.57 | 1132.39 | 25.34 | |

| PP-27% wood | 30.20 | 0.21 | 5.69 | 0.18 | 1378.63 | 22.98 | |

| PP-36% wood | 30.34 | 0.44 | 4.60 | 0.23 | 1544.98 | 31.86 | |

| 18 Months | HDPE Control | 4.55 | 0.55 | 1.09 | 0.15 | 781.58 | 41.13 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 24.23 | 0.94 | 9.98 | 0.92 | 1000.21 | 27.54 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 28.62 | 0.61 | 9.39 | 0.67 | 1204.85 | 29.77 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 31.11 | 0.40 | 7.78 | 0.27 | 1376.91 | 24.97 | |

| PP Control | 3.63 | 0.45 | 1.42 | 0.69 | 630.65 | 32.97 | |

| PP-18% wood | 26.30 | 0.20 | 6.53 | 0.34 | 1063.13 | 22.03 | |

| PP-27% wood | 28.75 | 0.46 | 5.63 | 0.30 | 1275.50 | 50.53 | |

| PP-36% wood | 30.00 | 0.24 | 4.67 | 0.29 | 1483.51 | 20.35 | |

| Accelerated Exposure Time/Energy | Material | Tensile Strength (Mpa) | % elongation at break | Modulus of Elasticity (Mpa) | |||

| Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | ||

| 214 h Exposure Energy = 276.8 kJ/sq.mt. | HDPE Control | 15.27 | 0.42 | 6.37 | 2.17 | 793.17 | 77.97 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 29.38 | 0.71 | 15.15 | 1.01 | 1090.50 | 17.23 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 33.47 | 0.26 | 10.40 | 0.76 | 1361.87 | 18.56 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 34.52 | 1.44 | 8.16 | 0.56 | 1488.11 | 98.97 | |

| PP Control | 33.05 | - | 8.38 | - | 1034.57 | - | |

| PP-18% wood | 35.38 | 0.45 | 7.59 | 0.38 | 1402.82 | 31.60 | |

| PP-27% wood | 36.33 | 0.22 | 5.65 | 0.26 | 1613.51 | 34.87 | |

| PP-36% wood | 34.91 | 0.58 | 4.60 | 0.28 | 1761.16 | 16.45 | |

| 483 h Exposure Energy = 624.9 kJ/sq.mt. | HDPE Control | 14.14 | 0.79 | 11.14 | 1.62 | 628.23 | 13.99 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 28.44 | 0.48 | 13.50 | 1.46 | 1078.97 | 19.89 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 31.79 | 0.86 | 10.00 | 0.60 | 1297.29 | 40.10 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 35.19 | 0.89 | 7.69 | 0.39 | 1566.84 | 54.39 | |

| PP Control | 23.19 | - | 7.12 | - | 853.28 | - | |

| PP-18% wood | 33.01 | 0.19 | 6.33 | 0.12 | 1363.88 | 24.19 | |

| PP-27% wood | 34.06 | 0.01 | 5.58 | 0.22 | 1535.70 | 3.10 | |

| PP-36% wood | 33.94 | 0.27 | 4.53 | 0.19 | 1777.21 | 61.82 | |

| 723 h Exposure Energy = 945 kJ/sq.mt. | HDPE Control | 14.45 | 0.20 | 11.37 | 1.68 | 558.04 | 21.26 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 28.58 | 0.47 | 11.41 | 0.55 | 1119.73 | 12.33 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 32.38 | 0.17 | 8.85 | 0.09 | 1337.09 | 9.03 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 35.05 | 1.57 | 7.42 | 0.14 | 1549.66 | 96.14 | |

| PP Control | 14.34 | - | 5.92 | - | 645.15 | - | |

| PP-18% wood | 30.35 | 0.69 | 6.07 | 0.32 | 1253.94 | 23.91 | |

| PP-27% wood | 32.09 | 0.23 | 5.27 | 0.36 | 1488.93 | 58.20 | |

| PP-36% wood | 32.28 | 0.31 | 4.36 | 0.11 | 1665.32 | 11.43 | |

| 1180 h Exposure Energy = 1514.6 kJ/sq.mt. | HDPE Control | 12.35 | - | 9.15 | - | 479.71 | - |

| HDPE-18% wood | 28.22 | 1.39 | 10.37 | 0.56 | 1093.23 | 56.28 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 32.31 | 1.19 | 8.43 | 0.65 | 1360.65 | 71.09 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 35.31 | 0.91 | 6.56 | 0.19 | 1579.18 | 49.82 | |

| PP Control | 4.68 | - | 4.58 | - | 353.50 | - | |

| PP-18% wood | 28.35 | 0.46 | 6.12 | 0.13 | 1135.02 | 35.05 | |

| PP-27% wood | 30.97 | 0.33 | 5.15 | 0.35 | 1451.05 | 23.63 | |

| PP-36% wood | 31.13 | 0.35 | 4.14 | 0.14 | 1661.96 | 54.21 | |

| Outdoor Exposure Duration | Material | Tensile Strength (Mpa) | % elongation at break | Modulus of Elasticity (Mpa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | ||

| Unexposed | HDPE Control | 23.67 | 0.23 | 1011.87 | 3.68 | 619.01 | 35.89 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 29.35 | 0.79 | 24.53 | 3.53 | 1010.31 | 51.08 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 33.05 | 0.84 | 13.75 | 1.52 | 1226.15 | 38.98 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 35.36 | 0.79 | 9.45 | 0.90 | 1461.73 | 56.92 | |

| PP Control | 37.84 | 0.18 | 43.15 | 7.41 | 991.73 | 3.07 | |

| PP-18% wood | 38.42 | 0.38 | 9.52 | 0.57 | 1370.90 | 12.70 | |

| PP-27% wood | 38.73 | 0.30 | 6.93 | 0.36 | 1553.33 | 42.83 | |

| PP-36% wood | 38.77 | 0.63 | 5.87 | 0.21 | 1712.30 | 14.51 | |

| 6 Months | HDPE Control | 4.67 | 0.99 | 5.34 | 7.01 | 969.82 | 39.14 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 28.50 | 0.99 | 13.78 | 1.60 | 1051.20 | 44.41 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 31.97 | 0.76 | 11.05 | 0.91 | 1264.55 | 45.03 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 34.47 | 0.60 | 8.05 | 0.34 | 1494.55 | 36.63 | |

| PP Control | 16.70 | 1.75 | 2.40 | 0.39 | 1052.09 | 5.26 | |

| PP-18% wood | 31.83 | 0.35 | 6.93 | 0.40 | 1295.30 | 28.43 | |

| PP-27% wood | 33.38 | 0.18 | 5.74 | 0.15 | 1492.23 | 22.43 | |

| PP-36% wood | 33.38 | 0.24 | 4.92 | 0.17 | 1651.79 | 27.03 | |

| 12 Months | HDPE Control | 4.41 | 0.99 | 1.55 | 0.55 | 776.78 | 20.32 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 25.20 | 0.85 | 11.70 | 0.53 | 1004.87 | 32.70 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 29.82 | 0.49 | 8.70 | 0.80 | 1244.91 | 28.31 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 32.35 | 0.55 | 7.86 | 0.25 | 1443.60 | 40.78 | |

| PP Control | 9.57 | 0.20 | 1.55 | 0.06 | 833.50 | 21.66 | |

| PP-18% wood | 28.02 | 0.53 | 7.18 | 0.57 | 1132.39 | 25.34 | |

| PP-27% wood | 30.20 | 0.21 | 5.69 | 0.18 | 1378.63 | 22.98 | |

| PP-36% wood | 30.34 | 0.44 | 4.60 | 0.23 | 1544.98 | 31.86 | |

| 18 Months | HDPE Control | 4.55 | 0.55 | 1.09 | 0.15 | 781.58 | 41.13 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 24.23 | 0.94 | 9.98 | 0.92 | 1000.21 | 27.54 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 28.62 | 0.61 | 9.39 | 0.67 | 1204.85 | 29.77 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 31.11 | 0.40 | 7.78 | 0.27 | 1376.91 | 24.97 | |

| PP Control | 3.63 | 0.45 | 1.42 | 0.69 | 630.65 | 32.97 | |

| PP-18% wood | 26.30 | 0.20 | 6.53 | 0.34 | 1063.13 | 22.03 | |

| PP-27% wood | 28.75 | 0.46 | 5.63 | 0.30 | 1275.50 | 50.53 | |

| PP-36% wood | 30.00 | 0.24 | 4.67 | 0.29 | 1483.51 | 20.35 | |

| Accelerated Exposure Time/Energy | Material | Tensile Strength (Mpa) | % elongation at break | Modulus of Elasticity (Mpa) | |||

| Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | ||

| 214 h Exposure Energy = 276.8 kJ/sq.mt. | HDPE Control | 15.27 | 0.42 | 6.37 | 2.17 | 793.17 | 77.97 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 29.38 | 0.71 | 15.15 | 1.01 | 1090.50 | 17.23 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 33.47 | 0.26 | 10.40 | 0.76 | 1361.87 | 18.56 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 34.52 | 1.44 | 8.16 | 0.56 | 1488.11 | 98.97 | |

| PP Control | 33.05 | - | 8.38 | - | 1034.57 | - | |

| PP-18% wood | 35.38 | 0.45 | 7.59 | 0.38 | 1402.82 | 31.60 | |

| PP-27% wood | 36.33 | 0.22 | 5.65 | 0.26 | 1613.51 | 34.87 | |

| PP-36% wood | 34.91 | 0.58 | 4.60 | 0.28 | 1761.16 | 16.45 | |

| 483 h Exposure Energy = 624.9 kJ/sq.mt. | HDPE Control | 14.14 | 0.79 | 11.14 | 1.62 | 628.23 | 13.99 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 28.44 | 0.48 | 13.50 | 1.46 | 1078.97 | 19.89 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 31.79 | 0.86 | 10.00 | 0.60 | 1297.29 | 40.10 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 35.19 | 0.89 | 7.69 | 0.39 | 1566.84 | 54.39 | |

| PP Control | 23.19 | - | 7.12 | - | 853.28 | - | |

| PP-18% wood | 33.01 | 0.19 | 6.33 | 0.12 | 1363.88 | 24.19 | |

| PP-27% wood | 34.06 | 0.01 | 5.58 | 0.22 | 1535.70 | 3.10 | |

| PP-36% wood | 33.94 | 0.27 | 4.53 | 0.19 | 1777.21 | 61.82 | |

| 723 h Exposure Energy = 945 kJ/sq.mt. | HDPE Control | 14.45 | 0.20 | 11.37 | 1.68 | 558.04 | 21.26 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 28.58 | 0.47 | 11.41 | 0.55 | 1119.73 | 12.33 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 32.38 | 0.17 | 8.85 | 0.09 | 1337.09 | 9.03 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 35.05 | 1.57 | 7.42 | 0.14 | 1549.66 | 96.14 | |

| PP Control | 14.34 | - | 5.92 | - | 645.15 | - | |

| PP-18% wood | 30.35 | 0.69 | 6.07 | 0.32 | 1253.94 | 23.91 | |

| PP-27% wood | 32.09 | 0.23 | 5.27 | 0.36 | 1488.93 | 58.20 | |

| PP-36% wood | 32.28 | 0.31 | 4.36 | 0.11 | 1665.32 | 11.43 | |

| 1180 h Exposure Energy = 1514.6 kJ/sq.mt. | HDPE Control | 12.35 | - | 9.15 | - | 479.71 | - |

| HDPE-18% wood | 28.22 | 1.39 | 10.37 | 0.56 | 1093.23 | 56.28 | |

| HDPE-27% wood | 32.31 | 1.19 | 8.43 | 0.65 | 1360.65 | 71.09 | |

| HDPE-36% wood | 35.31 | 0.91 | 6.56 | 0.19 | 1579.18 | 49.82 | |

| PP Control | 4.68 | - | 4.58 | - | 353.50 | - | |

| PP-18% wood | 28.35 | 0.46 | 6.12 | 0.13 | 1135.02 | 35.05 | |

| PP-27% wood | 30.97 | 0.33 | 5.15 | 0.35 | 1451.05 | 23.63 | |

| PP-36% wood | 31.13 | 0.35 | 4.14 | 0.14 | 1661.96 | 54.21 | |

| Outdoor Exposure Duration | Average Hardness Value [Std. Dev.] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDPE Control | HDPE-18% wood | HDPE-27% wood | HDPE- 36% wood | |

| Unexposed | 63.2 [0.1] | 65.8 [0.2] | 66.7 [0.4] | 68.3 [0.6] |

| 6 months | 56.9 [2.1] | 67.5 [0.3] | 66.4 [0.4] | 68.5 [2.0] |

| 12 months | 56.4 [2.3] | 63.4 [0.8] | 63.6 [1.2] | 67.6 [0.2] |

| 18 months | 56.3 [1.7] | 62.9 [1.7] | 61.2 [0.7] | 64.4 [0.7] |

| Outdoor Exposure Duration | Average Hardness Value [Std. Dev.] | |||

| PP Control | PP-18% wood | PP-27% wood | PP- 36% wood | |

| Unexposed | 73.9 [0.8] | 73.4 [1.0] | 73.3 [0.6] | 73.9 [1.1] |

| 6 months | 67.8 [1.1] | 68.0 [1.7] | 69.8 [0.8] | 68.1 [1.3] |

| 12 months | 68.1 [0.6] | 67.4 [1.2] | 68.1 [1.2] | 69.5 [0.8] |

| 18 months | 60.1 [2.1] | 60.8 [1.9] | 65.3 [1.5] | 67.8 [2.1] |

| Accelerated Exposure Duration | Average Hardness Value [Std. Dev.] | |||

| HDPE Control | HDPE-18% wood | HDPE-27% wood | HDPE- 36% wood | |

| 214 hours | 63.2 [1.2] | 64.4 [0.8] | 66.0 [1.3] | 68.8 [1.1] |

| 483 hours | 54.6 [2.6] | 65.1 [1.4] | 66.0 [1.3] | 67.6 [2.1] |

| 723 hours | 53.9 [1.0] | 61.7 [3.0] | 64.3 [1.6] | 67.5 [1.0] |

| 1180 hours | 47.5 [2.8] | 60.1 [1.1] | 65.5 [0.7] | 67.1 [1.5] |

| Accelerated Exposure Duration | Average Hardness Value [Std. Dev.] | |||

| PP Control | PP-18% wood | PP-27% wood | PP- 36% wood | |

| 214 hours | 72.3 [1.2] | 70.8 [1.0] | 71.8 [1.4] | 73.0 [0.8] |

| 483 hours | 67.0 [0.7] | 69.7 [1.5] | 72.0 [1.3] | 71.0 [1.7] |

| 723 hours | 62.6 [1.5] | 66.6 [1.9] | 69.3 [1.1] | 72.4 [1.0] |

| 1180 hours | 54.8 [1.0] | 65.4 [3.5] | 68.2 [2.4] | 70.3 [0.8] |

| Exposure Duration | Material | Mw | Mn | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexposed | HDPE Control | 78428 | 15208 | 5.16 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 61839 | 12871 | 4.81 | |

| PP Control | 194387 | 37189 | 5.23 | |

| PP-18% wood | 190151 | 32495 | 5.85 | |

| 6 Months | HDPE Control | 26680 | 7481 | 3.57 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 69140 | 15891 | 4.35 | |

| PP Control | 31292 | 7899 | 3.96 | |

| PP-18% wood | 189532 | 30840 | 6.15 | |

| 12 Months | HDPE Control | 23019 | 5929 | 3.88 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 72990 | 14369 | 5.08 | |

| PP Control | 7398 | 3154 | 2.35 | |

| PP-18% wood | 167423 | 26657 | 6.28 | |

| 18 Months | HDPE Control | 23282 | 5426 | 4.29 |

| HDPE-18% wood | 60495 | 15550 | 3.89 | |

| PP Control | 5975 | 2906 | 2.06 | |

| PP-18% wood | 155017 | 28854 | 5.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).