Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specific Anammox Activity (SAA)

2.2. Kinetic Model Fitting

2.3. Extended Nitrite Exposure Experiments

2.4. Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

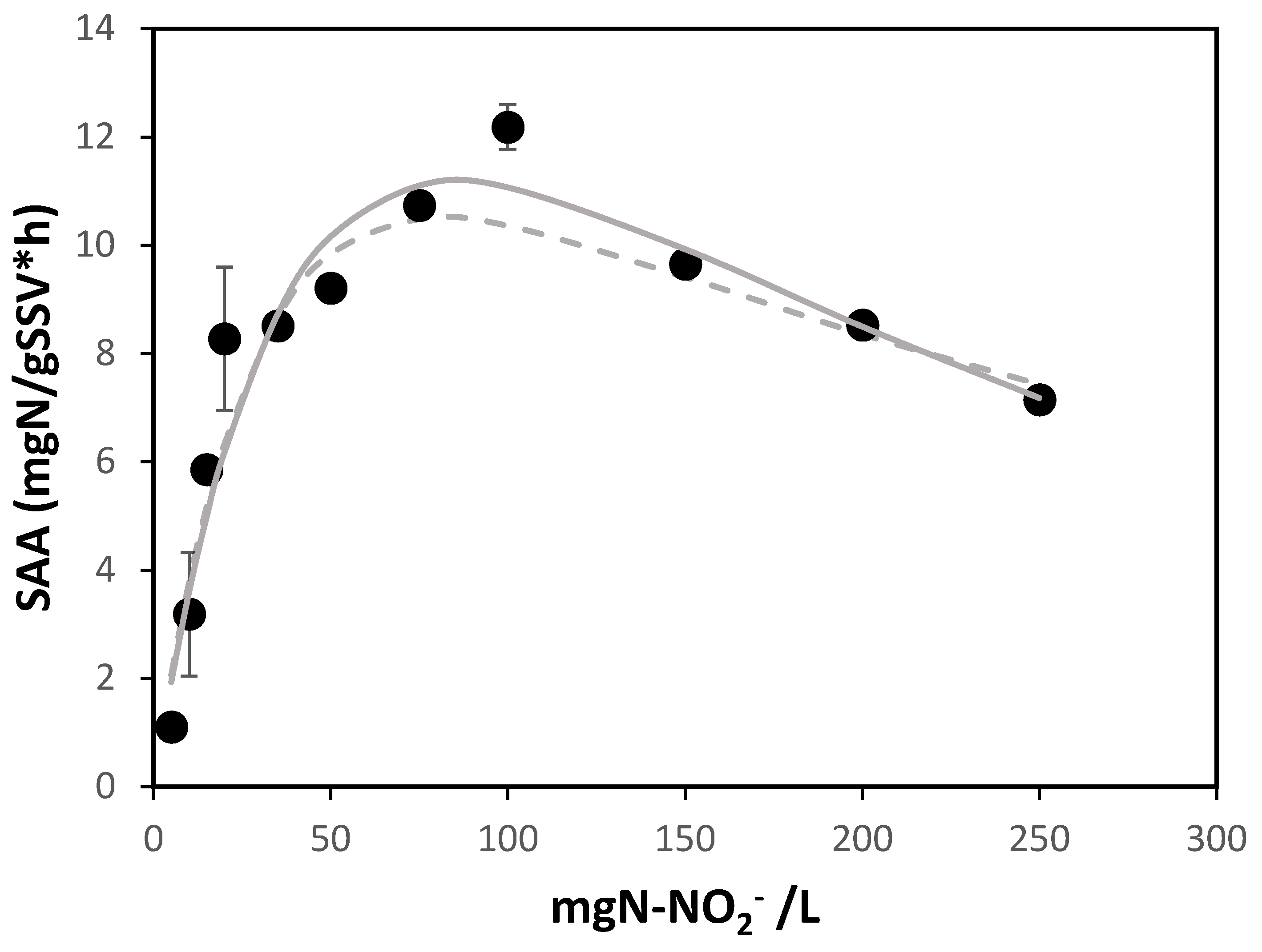

3.1. Short-Term Nitrite Effect

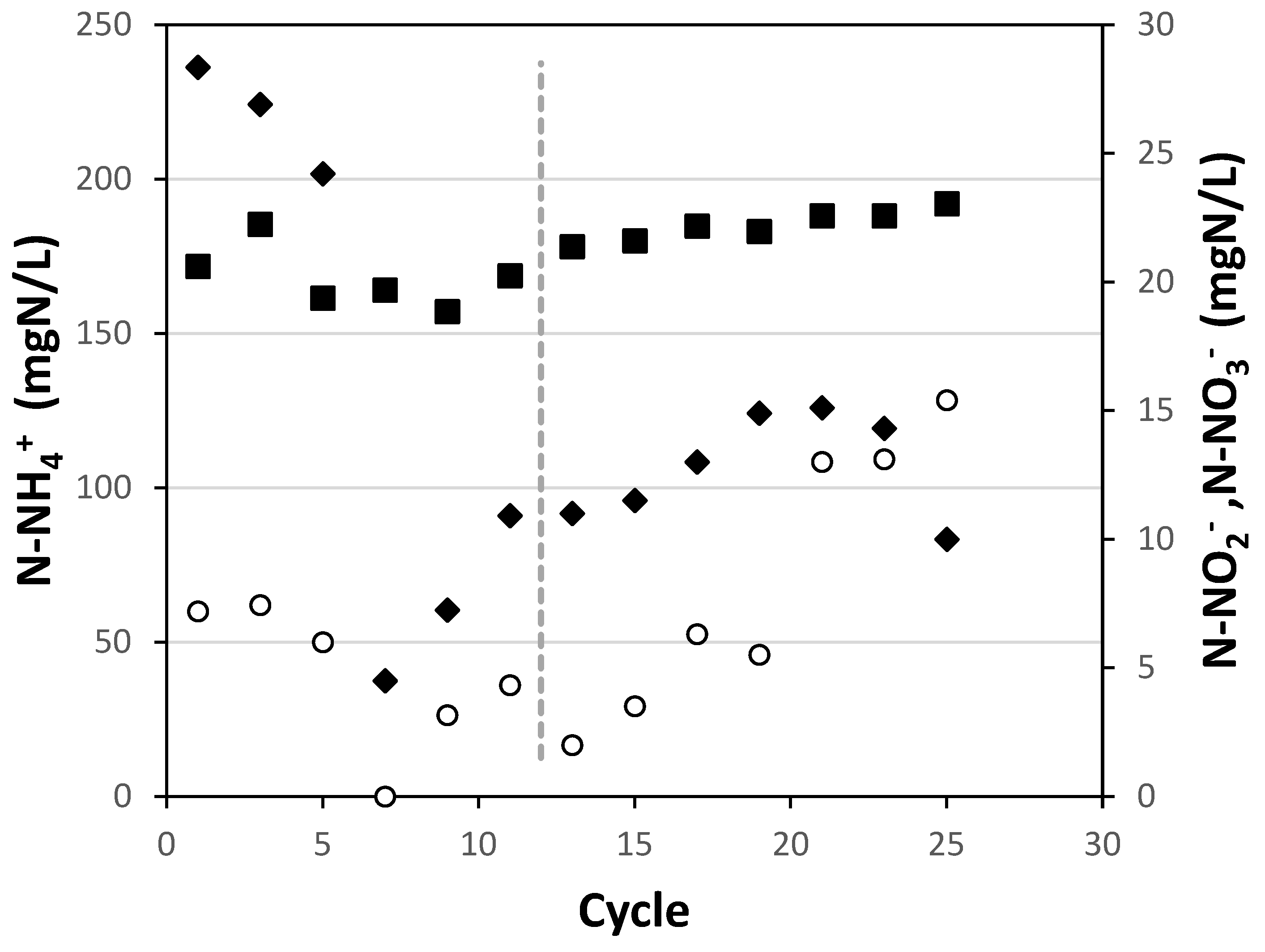

3.2. Long-Term Nitrite Effect

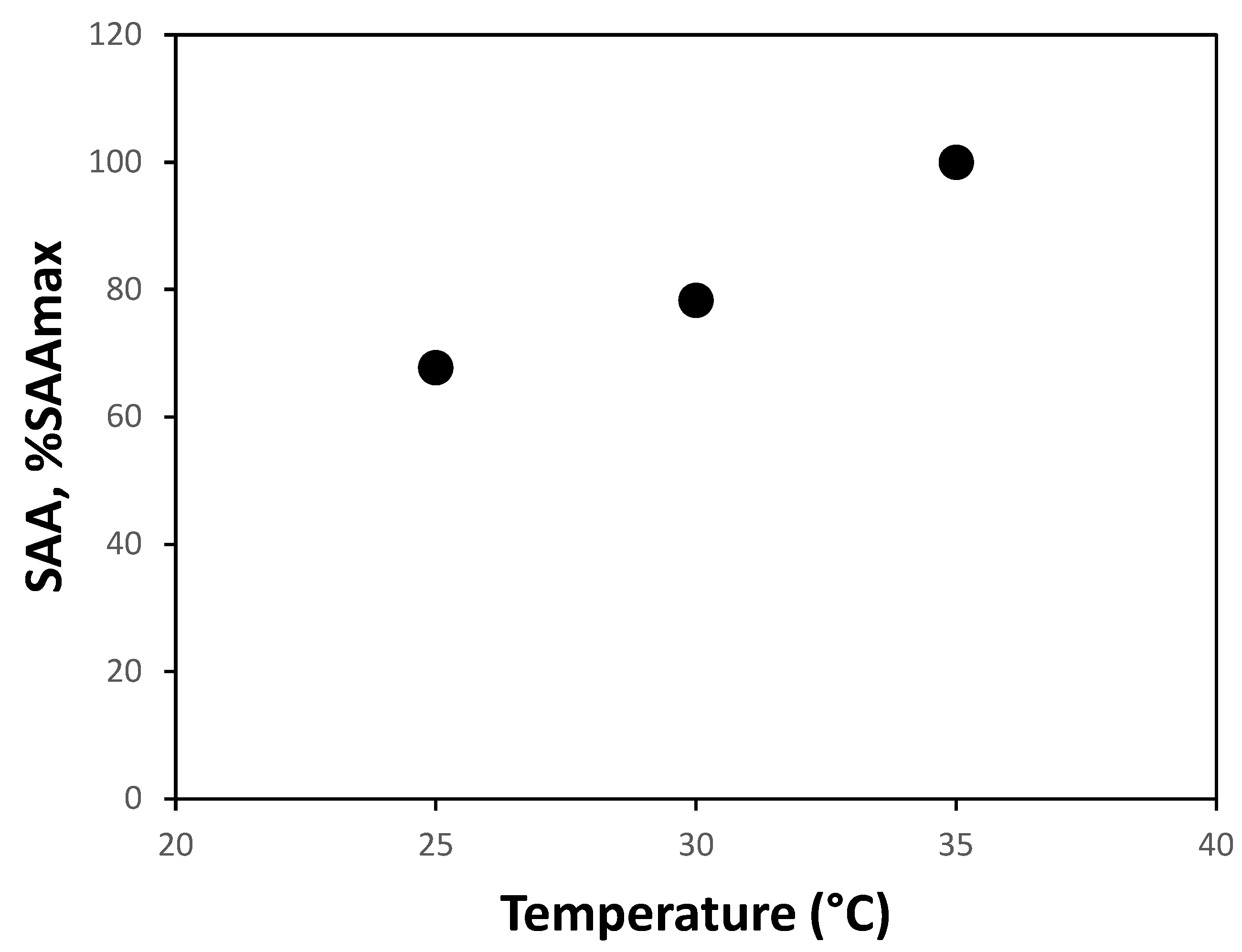

3.3. Short-Term Effect of Temperature

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, V. H., Tilman, G. D., & Nekola, J. C. (1999). Eutrophication: impacts of excess nutrient inputs on freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems. Environmental pollution, 100(1-3), 179-196. [CrossRef]

- Lackner, S., Gilbert, E. M., Vlaeminck, S. E., Joss, A., Horn, H., & Van Loosdrecht, M. C. (2014). Full-scale partial nitritation/anammox experiences–an application survey. Water research, 55, 292-303. [CrossRef]

- Driessen, W., & Hendrickx, T. (2021). Two decades of experience with the granular sludge-based anammox® process treating municipal and industrial effluents. Processes, 9(7), 1207. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z. Q., Wang, H., Zhang, L. G., Du, X. N., Huang, B. C., & Jin, R. C. (2022). A review of anammox-based nitrogen removal technology: From microbial diversity to engineering applications. Bioresource Technology, 363, 127896. [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, S., Biswas, R., & Nandy, T. (2012). Autotrophic ammonia removal processes: ecology to technology. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 42(13), 1353-1418. [CrossRef]

- Talan, A., Tyagi, R. D., & Drogui, P. (2021). Critical review on insight into the impacts of different inhibitors and performance inhibition of anammox process with control strategies. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 23, 101553. [CrossRef]

- Gutwiński, P., Cema, G., Ziembińska-Buczyńska, A., Wyszyńska, K., & Surmacz-Gorska, J. (2021). Long-term effect of heavy metals Cr (III), Zn (II), Cd (II), Cu (II), Ni (II), Pb (II) on the anammox process performance. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 39, 101668. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, I., Dosta, J., Fajardo, C., Campos, J. L., Mosquera-Corral, A., & Méndez, R. (2012). Short-and long-term effects of ammonium and nitrite on the Anammox process. Journal of Environmental Management, 95, S170-S174. [CrossRef]

- Strous, M., Kuenen, J. G., & Jetten, M. S. (1999). Key physiology of anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Applied and environmental microbiology, 65(7), 3248-3250. [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Arroyo, J. M., Sun, W., Sierra-Alvarez, R., & Field, J. A. (2013). Inhibition of anaerobic ammonium oxidizing (anammox) enrichment cultures by substrates, metabolites and common wastewater constituents. Chemosphere, 91(1), 22-27. [CrossRef]

- Oshiki, M., Shimokawa, M., Fujii, N., Satoh, H., & Okabe, S. (2011). Physiological characteristics of the anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacterium ‘Candidatus Brocadia sinica’. Microbiology, 157(6), 1706-1713. [CrossRef]

- Marina, C., Kunz, A., Bortoli, M., Scussiato, L. A., Coldebella, A., Vanotti, M., & Soares, H. M. (2016). Kinetic models for nitrogen inhibition in ANAMMOX and nitrification process on deammonification system at room temperature. Bioresource technology, 202, 33-41. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J. F. (1968). A mathematical model for the continuous culture of microorganisms utilizing inhibitory substrates. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 10(6), 707-723. [CrossRef]

- Boon, B., & Laudelout, H. (1962). Kinetics of nitrite oxidation by Nitrobacter winogradskyi. Biochemical Journal, 85(3), 440. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, V. H. (1970). The influence of high substrate concentrations on microbial kinetics. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 12(5), 679-712. [CrossRef]

- Dapena-Mora, A., Fernandez, I., Campos, J. L., Mosquera-Corral, A., Mendez, R., & Jetten, M. S. M. (2007). Evaluation of activity and inhibition effects on Anammox process by batch tests based on the nitrogen gas production. Enzyme and microbial technology, 40(4), 859-865. [CrossRef]

- Weatherburn, M. W. (1967). Phenol-hypochlorite reaction for determination of ammonia. Analytical chemistry, 39(8), 971-974.

- Raudkivi, M., Zekker, I., Rikmann, E., Vabamäe, P., Kroon, K., & Tenno, T. (2017). Nitrite inhibition and limitation–the effect of nitrite spiking on anammox biofilm, suspended and granular biomass. Water Science and Technology, 75(2), 313-321. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S., Takahashi, Y., Fujii, N., Yamada, Y., Satoh, H., & Okabe, S. (2010). Nitrogen removal performance and microbial community analysis of an anaerobic up-flow granular bed anammox reactor. Chemosphere, 78(9), 1129-1135. [CrossRef]

- Zu, B., Zhang, D. J., & Yan, Q. (2008). Effect of trace NO2 and kinetic characteristics for anaerobic ammonium oxidation of granular sludge. Huan Jing ke Xue= Huanjing Kexue, 29(3), 683-687.

- Baeten, J. E., Batstone, D. J., Schraa, O. J., van Loosdrecht, M. C., & Volcke, E. I. (2019). Modelling anaerobic, aerobic and partial nitritation-anammox granular sludge reactors-A review. Water research, 149, 322-341. [CrossRef]

- Ni, B. J., Hu, B. L., Fang, F., Xie, W. M., Kartal, B., Liu, X. W., ... & Yu, H. Q. (2010). Microbial and physicochemical characteristics of compact anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing granules in an upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 76(8), 2652-2656. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., He, S., Niu, Q., Qi, W., & Li, Y. Y. (2016). Characterization of three types of inhibition and their recovery processes in an anammox UASB reactor. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 109, 212-221. [CrossRef]

- Puyol, D., Carvajal-Arroyo, J. M., Sierra-Alvarez, R., & Field, J. A. (2014). Nitrite (not free nitrous acid) is the main inhibitor of the anammox process at common pH conditions. Biotechnology letters, 36, 547-551. [CrossRef]

- Jin, R. C., Yu, J. J., Ma, C., Yang, G. F., Zhang, J., Chen, H., ... & Hu, B. L. (2014). Transient and long-term effects of bicarbonate on the ANAMMOX process. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 98, 1377-1388. [CrossRef]

- Lotti, T., Kleerebezem, R., & Van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. (2015). Effect of temperature change on anammox activity. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 112(1), 98-103. [CrossRef]

- Dosta, J., Fernández, I., Vázquez-Padín, J. R., Mosquera-Corral, A., Campos, J. L., Mata-Alvarez, J., & Méndez, R. (2008). Short-and long-term effects of temperature on the Anammox process. Journal of hazardous materials, 154(1-3), 688-693. [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, D., Zhai, J., & Makinia, J. (2021). Generalized temperature dependence model for anammox process kinetics. Science of the Total Environment, 775, 145760. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z., Lotti, T., de Kreuk, M., Kleerebezem, R., van Loosdrecht, M., Kruit, J., ... & Kartal, B. (2013). Nitrogen removal by a nitritation-anammox bioreactor at low temperature. Applied and environmental microbiology, 79(8), 2807-2812. [CrossRef]

| Cycle | SAA (mgN/gSSV·h) |

| 1 | 5,43 |

| 12 | 5,32 |

| 25 | 2,67±0,3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).