1. Introduction

Biogas production by anaerobic treatment of organic waste is one of the most effective ways to mitigate climate change. This kind of treatment of the waste releases biogas, which primarily consists of methane (CH

4), carbon dioxide (CO

2), oxygen (O

2), nitrogen (N

2), and hydrogen sulphide (H

2S) [

1]. The composition of biogas affects the operation of cogeneration engines and the energy value of biogas itself [

1]. Reducing CO

2 concentration can increase the energy value of biogas and thus satisfy the standards in a specific country for the injection of biogas into natural gas pipe network or the usage for vehicles [

2].

Various methods are employed worldwide to enhance biogas purification processes: chemical, physical, vacuum swing adsorption, and the biological one [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. In particular, the potential of biological methods is being extensively studied and assessed. Efforts have been made to use microalgae cultures for biogas purification more intensively due to two main reasons: production of highly purified biogas and generation of microalgae biomass [

8,

9]. Firstly, biologically purified biogas can be transformed into nearly pure CH

4, allowing the upgraded biogas to be supplied to natural gas networks, effectively replacing them as a substitute. A higher concentration of CH₄ in biogas indicates greater energy efficiency and increased power generation potential in CH₄-based energy systems. In such case, clear economic benefits would be achieved [

10,

11,

12]. Moreover, highly purified biogas can be used as a fuel for transport vehicles when quality and compliance requirements of these fuels, which differ from country to country, are met [

13,

14]. However, the presence of a high amount of non-combustible CO₂ reduces the calorific value of raw biogas [

15]. As a result, biogas upgrading technologies are necessary to enhance its calorific value. Capturing CO

2 from biogas can be named as effective biogas upgrading technology.

Different microalgae species have been used for biogas upgrading. Microalgae species used for CO

2 mitigation include

Chlorella vulgaris [

16],

Chlorella kessleri [

17],

Monoraphidium griffithii [

18],

Botryococcus braunii and

Scenedesmus sp. [

19]. An algae photobioreactor (PBR) with

Chlorella vulgaris suspension can be used to produce and sustain big biomass production and the CO

2 capture rate in a wide range of CO

2 concentrations from 0.04% to 18% [

16] when operated in continuous flow mode [

20]. As it is known that CO

2 content in the biogas can range from 30% to 50% [

21], it is important to search for CO

2 tolerant microalgae species, which could be used in the PBR. Some CO

2 tolerant microalgae like,

Desmodesmus sp., can grow at CO

2 concentration of 50% or higher [

22]. Choosing the right microalgal strains is crucial for biogas upgrading systems operating under high CO

2 partial pressure.

Photosynthetic cultivation of microalgae can be performed in both open pond system or closed PBR. Different types of closed PBRs have been used for cultivation of green microalgae, including flat-plate, tubular and column type [

23]. Column-type PBRs can be further categorized into stirred-tank PBRs and aerated columns, which include bubble columns or airlift systems. Vertical PBR consists of a transparent column most usually produced from high quality glass, and is encased in a water jacket. This jacket enables temperature control by circulating water while still allowing sufficient light to penetrate the system [

24]. The benefits of bubble column PBRs include their mechanical simplicity, low initial cost, efficient heat and mass transfer capabilities, and the absence of moving parts.

A thorough understanding of various aspects of cell physiology and behavior is essential for the successful implementation of a PBR. Physicochemical parameters such as nutrient availability and pH have a significant influence on performance of PBR. Enhancing the nutrient medium for cultivating microalgae is done to improve the efficiency of CO₂ capture. Chemical composition of culture medium is vital for microalgae growth, therefore some studies have shown that addition of sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO

3) significantly improved microalgae productivity, as well as CO

2 utilization process [

25]. Other study showed importance of nitrogen source (NO

3-N) on green algae (

Chlorella and

Scenedesmus) growth prolongation and CO

2 fixation improvement [

26]. Magnesium (Mg) can act as central atom of chlorophyll and participate in photosynthesis, while calcium (Ca) can participate in many cellular metabolic activities [

27].

Another factor important in PBR performance is pH. Optimum range of pH is important for the overall health of microalgae culture, which is involved in the uptake CO

2 and other important nutrients. It has been reported that optimal medium pH range for the microalgae growth is 7-9 [

28], however most of the species show a maximum activity at pH 7-8 [

21]. If pH is not kept at the ideal value, there is a risk of biomass production decrease. pH is heavily affected by the concentration of dissolved carbon species [

23]. CO

2 in water can be found in different forms according to pH: in acidic pH (<5) dissolved carbon can be found in the form of CO

2, in neutral system (7<pH<9) as HCO

3- and in alkaline pH (>9) as CO

32-. An alkaline pH is favorable for biogas upgrading because it increases the solubility of CO

2 [

21].

Besides physicochemical parameters, another factors affecting CO

2 capture and microalgae growth are physical and operational such as light intensity and light wavelength. In general, the amount of light energy absorbed and stored by the cells is directly linked to their carbon fixation capacity, which in turn influences biomass productivity and the cell growth rate [

29]. Thus, improving light utilization efficiency is crucial for achieving greater CO

2 fixation capacity. It is known, that any photosynthetic system has its saturation point where further increasing of light intensity does not benefit CO

2 fixation or productivity. One study [

30] showed that the highest CO

2 removal ratio (67%) by

Scenedesmus obliquus strain WUST4 was achieved at 12,000-13,000 lx. However, CO

2 removal rate declined at higher light levels (>13,000 lx) due to inhibition of algal photosynthesis. Light driven growth follows saturation kinetics as well, when maximum growth efficiency is achieved once a threshold of light intensity is exceeded [

31]. As light intensity increases, a saturation point is reached, causing growth to stabilize. However, further increase of light intensity may kill the cells. For example, Ogbonna et al. [

32] showed that optimal light intensity for

Desmodesmus subspicatus biomass production was 5,000 lx. However, the increase of light intensity (from 5,000 lx to 10,000 lx) led to the destruction of microorganisms. As can be seen from the reviewed studies, the light intensity affects both CO

2 fixation and biomass productivity, which may differ depending on the microalgae species, so the optimal light intensity should be selected taking into account the species under consideration. To sum up, nutrients, pH and light could be ascribed as most important factors for the growth of microalgae and CO

2 fixation.

Moreover, the pigments in chloroplasts absorb light differently depending on the light’s wavelength (ranging from 400 nm to 700 nm), which in turn influences photosynthesis process in microalgae based on the light wavelength or color [

27]. One of such pigment found in green algae is chlorophyll, which captures photosynthetic light. Studies have demonstrated that green algae exhibit better growth under blue and red light because they contain chlorophyll a and b, which are key pigments for capturing light and are particularly responsive to these wavelengths [

33]. Improved green algae growth was observed in this region.

Among all the physical and chemical technologies used for biogas purification, water washing method is the closest technology to the biological biogas treatment in PBR. Water washing is a physical CO

2 absorption method [

34]. In comparison to the methods mentioned above, the water washing technique uses water as the absorbent and offers benefits such as lower cost, greater stability and safety, and a more environmentally friendly approach. It is still commonly used in European industries today, particularly for upgrading biogas. One study [

35] showed that significant removal efficiency of 86% can be achieved using water wash concept for CO

2 capture. Considering that biogas purification takes place in a closed PBR due to microalgae suspension (liquid medium), it is not difficult to see similarities between this technology and physical absorption process, where purification also takes place in a liquid medium, in that case, water. In both technologies, the components of biogas are physically absorbed, in first case by live organisms – microalgae suspension, in second case – by water [36,37].

This reasearch focused on the process of biogas upgrading mediated by microalgae species that have not been widely studied for this application. The study investigated two microalgae culture systems (Monoraphidium griffithi and Desmodesmus sp.) and two systems without microalgae cultures (mineral salt media and aqueous media) with the following objectives: 1) compare the efficiency of biogas purification using different microalgae cultures (Monoraphidium griffithi and Desmodesmus sp.) and absorbents (mineral salt solution and water); 2) determine Monoraphidium griffithi and Desmodesmus sp. capacities to capture CO2.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microalgal Species and Cultivation Conditions

Monoraphidium griffithi and

Desmodesmus sp. microalgae cultures were prepared by inoculating microalgal solids. The microalgae were selected from a microalgae collection housed at Nature Research Centre in Lithuania. Before the experiment, microalgae were inoculated for 14 days in MWH (Modified Woods Hole) medium. The composition of the nutrient-saturated MWH medium is given in

Table 1. Water quality met the required elements for microalgae growth, and it contained more nitrogen (N), magnesium (Mg) and calcium (Ca). Macronutrients, such as N and phosphorus (P), are vital for the general growth and development of microalgae, while micronutrients, such as vitamins and trace metals, though needed in smaller amounts, are just as critical for their optimal growth and CO

2 absorption [

38].

The trace elements were mixed with distilled water in the appropriate ratio given in

Table 1. Prior to studying the shape, size, and quantity of microalgal cells, they were cultivated in an algal culture reactor at the Nature Research Center for a period of 20-30 days. The algae cultivation occurred at room temperature of 22±2 °C under fluorescent lamps emitting approximately 250 μmol/m

2/s of white light for about of 10 h per each day. Light intensity was measured using a LI190SA Quantum Data Logger (model LI-1400). Additionally, oxygen was introduced into the microalgae suspension during inoculation to enhance the growth rate and concentration of the cultures. The physical and chemical parameters of the suspensions are given in

Table 2.

A total of 4 liters of microalgae suspension was required, since it corresponds to the volume of the columns in the experimental setup. The microalgae medium was diluted with the nutrient medium in a way that ensured uniform chlorophyll content across all microalgae suspensions. The initial chlorophyll concentration was 325±10 mg/L, while initial concentration of microalgae was 565±30×103 cells/m.

2.2. Experimental Apparatus

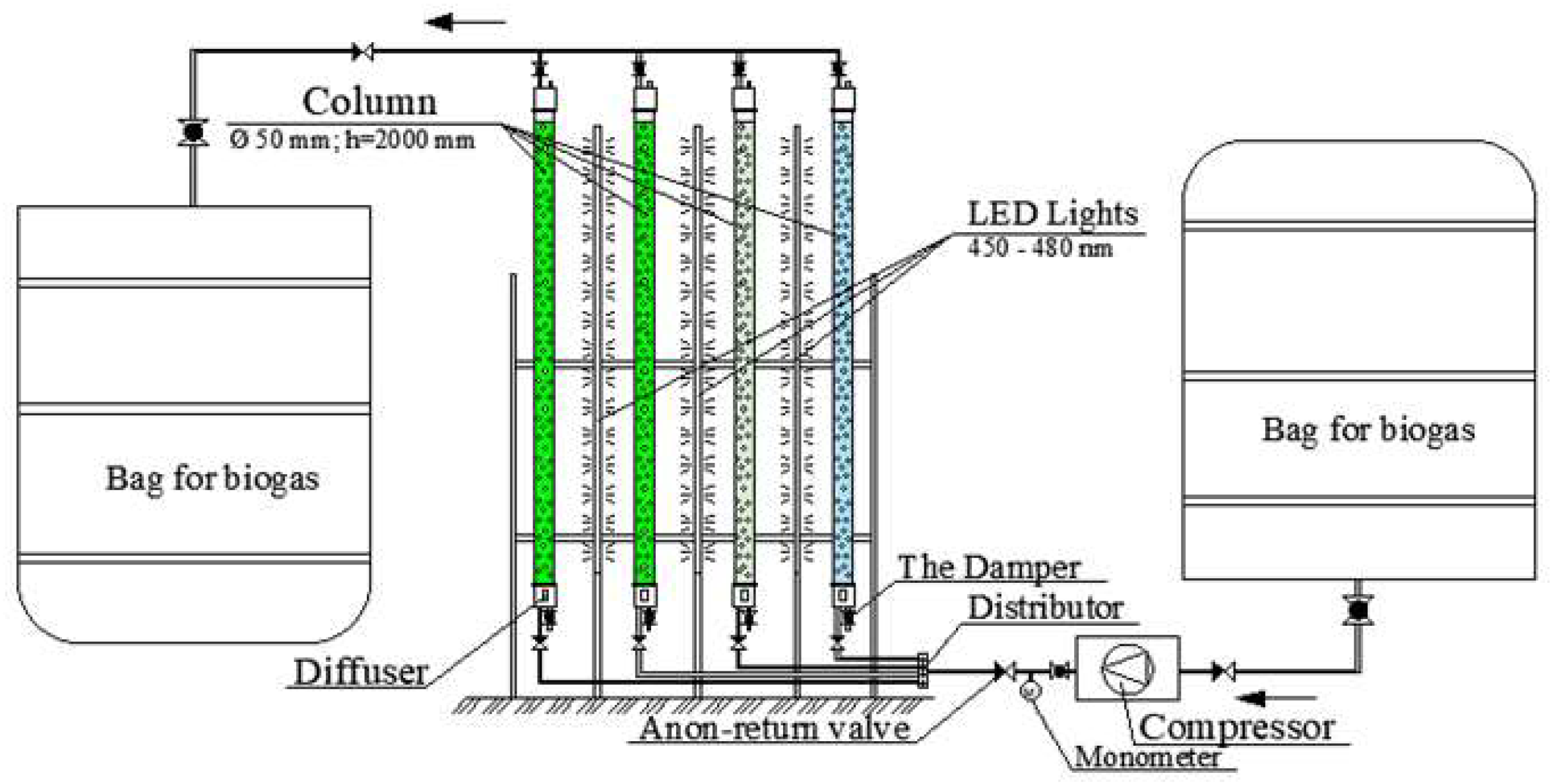

The experimental bench consisted of a bag for inlet biogas, compressor, PBR, and bag for outlet biogas. The PBR consisted of biogas inlet system, LED lighting system, four columns (each with a volume of 4 litres), and biogas outlet system. A scheme of the experimental apparatus can be seen in

Figure 1.

The experimental apparatus consisted of four columns: two with different microalgae suspensions (Monoraphidium griffithii; Desmodesmus sp.) and the other two with MWH medium and distilled water used as a nutrient and water source for the cultivation of the microalgae in the PBR. Before filling the columns with microalgae suspensions, MWH medium, and distilled water, their physical and chemical parameters were measured: pH, electrical conductivity, redox potential, total dissolved solids (TDS) and chlorophyll concentration. To compare the effect of nutrient medium and water on CO2 purification from biogas, two columns were filled with these suspensions.

Biogas from the tank was supplied by a compressor through a distributor to four columns. Each column was 2.0 m in height and 0.05 m in diameter. The distributor was equipped with valves that allowed regulation of biogas flow to each column. To ensure uniform biogas distribution across the entire cross-sectional area of the columns, diffusers were installed at the bottoms of the columns, breaking down biogas into small air bubbles, which enhanced the absorption and decomposition of its components. The columns were side-lit with LED blue light source equipped with dimmers and adjustable wavelengths ranging from 450 to 480 nm (

Figure 1). After purification, the biogas was collected in a 2 m

3 tank.

To facilitate photosynthesis in the PBR columns, a white-light LED source was used for illumination. The LED source was positioned 20 cm away from the columns to ensure an even distribution of light across their entire surface area. The light intensity was adjusted to achieve illumination level of 5000 lx, while the temperature was maintained at 20.2±1 °C.

2.3. Biogas and Calculations of Biomedium Viscosity and Bubble Rise Velocity

In this study, biogas generated from anaerobic treatment of sewage sludge was utilized. The biogas for the experiments was sourced from the Vilnius wastewater treatment plant. Its composition consisted of 56.1% methane, 35.8% carbon dioxide, 2.5% oxygen and 2 ppm hydrogen sulphide. The biogas was supplied to the columns of the experimental setup at a flow rate of 0.2 L/min.

The biogas passed through columns for 36 hours under plug-flow operation. Using the Hadamard-Rybczynski equation [

39], the average dynamic viscosity was determined to be 0.00127 Pa·s. At this viscosity, the biogas bubbles rose at an average speed of 0.6635 m/s. Having a column height of 200 cm and a width of 5 cm, the calculated retention time for biogas, based on bubble rise speed of 0.6635 m/s, was 3.01 seconds. The biogas was sampled and its composition was measured from each column every 2 hours, excluding a 12-hour period overnight from 10 p.m. to 10 a.m., with measurements repeated three times.

2.4. Estimation of the Microalgae Growth Rate

Prior to calculating the biomass growth rate, the biomass quantity was estimated. The estimation involved counting the microalgae cells and assessing their shape and size. The microalgae

Monoraphidium griffithii had a spindle shape, and their volume was determined using Equation 1:

where VC is the volume of the spindle-shaped cell (μm3); d is the diameter of the cell (μm); l is the length of the cell (μm).

The volume of

Desmodesmus sp. microalgae was determined using Equation 2:

where Velip denotes the volume of the spindle-shaped cell (μm3); d represents the diameter of the cell (μm); l indicates the length of the cell (μm).

The weight of algal biomass was determined using Equation 3:

where Kmic represents the weight of the wet algal biomass (μg); V is the volume of algal cell (μm3); CC is the cell count per 1 mL.

2.5. Analytical Methods and Statistical Analysis

The biogas composition was measured using the nondispersive infrared (NDIR) technique with the dual beam method. Biogas composition measurements were taken with an INCA 4000 biogas analyzer, which provides concentrations of methane (%), carbon dioxide (%), oxygen (%) and hydrogen sulfide (ppm). The analyzer’s measurement ranges and accuracy are as follows: oxygen – 0-25% (±1%), hydrogen sulphide – 0-100 ppm (±5%), methane – 0-100% (±1%), carbon dioxide – 0-100 (±1%).

For pH determination, the WTW ™ SenTix ™ 980 Digital IDS pH electrode pH meter was used, which measures pH of the solution within a range from 0 to 14 (±0.1 accuracy) and temperature from -5 °C to 60 °C (±0.5 °C accuracy). Redox potential, TDS and temperature were measured using the SenTix® ORP-T 900 ORP electrolyte, with measurement range of -1250 to 1250 mV for redox potential, 0-100 °C for temperature, and 0-2000 mg/l for TDS. Electrical conductivity was measured using the WTW TertraCon 925 sensor, which has a measurement range from 1µS/cm to 2 S/cm. Light intensity was measured using a Metrel Poly MI6401 luxmeter, which operates within a 0-10,000 lx range. Chlorophyll content was analyzed with an AlgaeLab Analyser chlorimeter. Studies on microalgal cell shape, size, and quantity were conducted using a Nikon ECLIPSE Ci-L optical microscope, which has a resolution of 1 µm and a magnification capability up to 600 times.

The data were analyzed and presented as mean ± standard deviation based on three independent assays. Calculated statistical indicators included arithmetic mean of measurements, arithmetic variance, and standard deviation of arithmetic mean. Microsoft Office Excel 2003 was used to perform these calculations.

3. Results

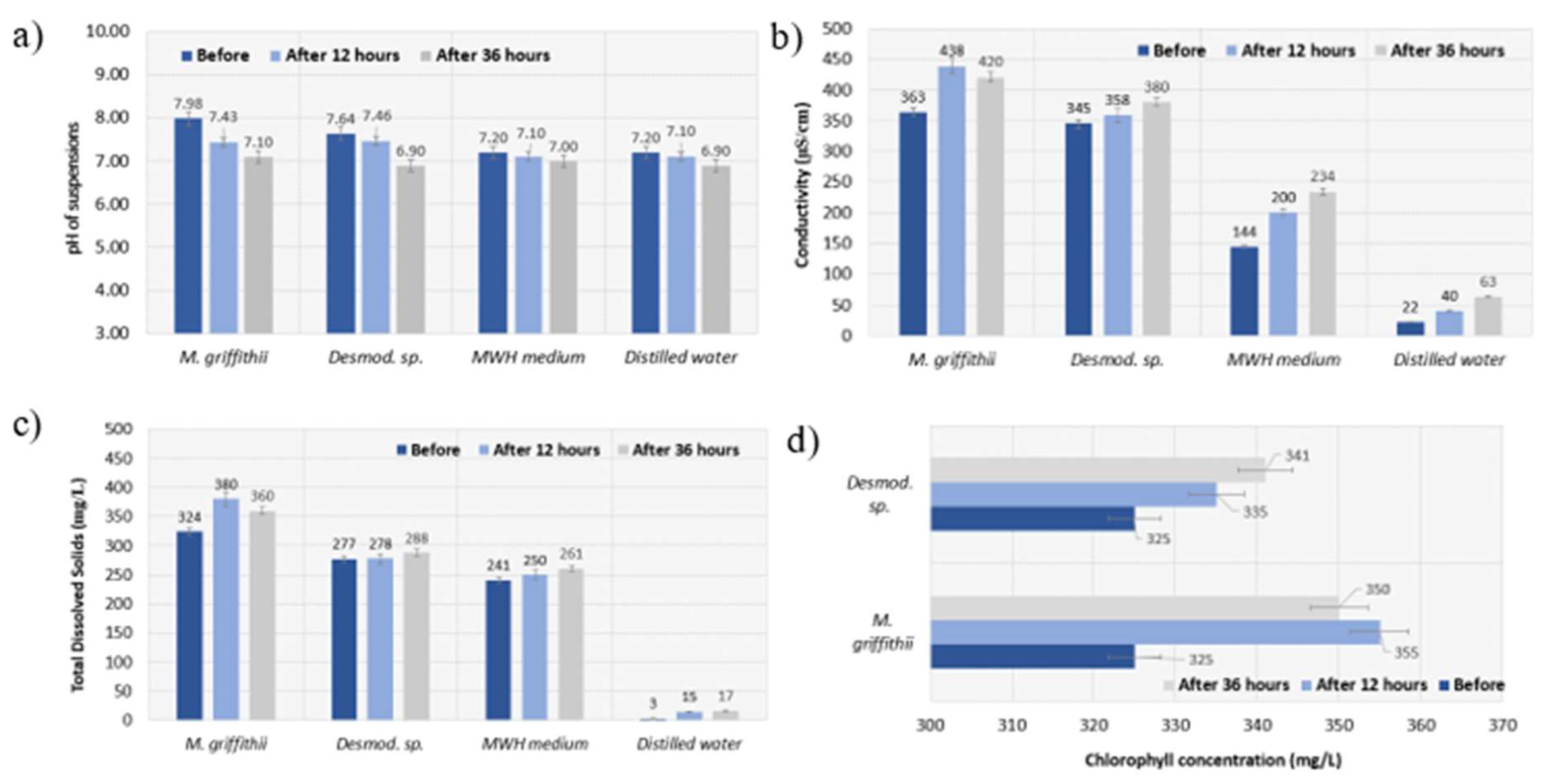

The physical and chemical parameters of the suspensions were measured prior to the experiment, after 12 hours of biogas purification, and again after 36 hours of biogas purification. The pH dynamics are shown in

Figure 2a. The results show that in all media pH decreased slightly over time from 0 to 36 hours, which was expected, due to the higher concentration of CO

2 concentration in the biogas. High biogas CO

2 concentration increase the partial pressure of dissolved CO

2 and the concentration of carbonic acid, this way reducing pH [

40]. Therefore, constant pH drop in all tretaments could be explained by relatively stable gas-liquids CO

2 dynamics. On the other hand, the electrical conductivity parameter increased almost for all media including

Monoraphidium griffithii suspension, MWH medium and the distilled water, except for the

Desmodesmus sp. suspension, where it dropped (

Figure 2b). The sum of all inorganic salts is the TDS, which is almost the same as salinity [

41]. According to

Figure 2c, TDS for MWH medium that contained

Desmodesmus sp. did not show significant changes from 0 to 36 hours and was similar to the values obtained from MWH medium itself. However, in the case of TDS for MWH medium that contained

Monoraphidium griffithii, it was a more significant rise of TDS by 130 mg/l after 12 hours and by 99 mg/l after 36 hours compared to MWH medium. However, an observed decrease in TDS with time shows that

Monoraphidium griffithii utilized dissolved solids for growth and metabolism through bioabsorption/adsorption. Many researchers have reported a reduction in TDS during water treatment using microalgae [

42]. The chlorophyll concentration parameter is only relevant for microalgae suspensions, but in both cases the chlorophyll concentration increased, which means that the biomass of the microalgae grew during experiment (

Figure 2d). Chlorophyll content reached its peak (341 mg/l) in

Desmodesmus sp. group at the end of the experiment (after 36 hours), meanwhile in

Monoraphidium griffithii group peak (355 mg/l) was reached at the beginning (after 12 hours) and even at the end was higher than in

Desmodesmus sp. group. These results suggest that

Monoraphidium griffithii system should be more beneficial for purifying biogas what was later proved by the CO

2 fixation analysis. Redox potential can be used for monitoring oxidative stress, thus this parameter was recorded during this study as well. High redox potential was recorded in all suspensions during the entire study. After 36 hours, the redox potential increased in

Monoraphidium griffithii microalgae suspension and reached 265 mV.

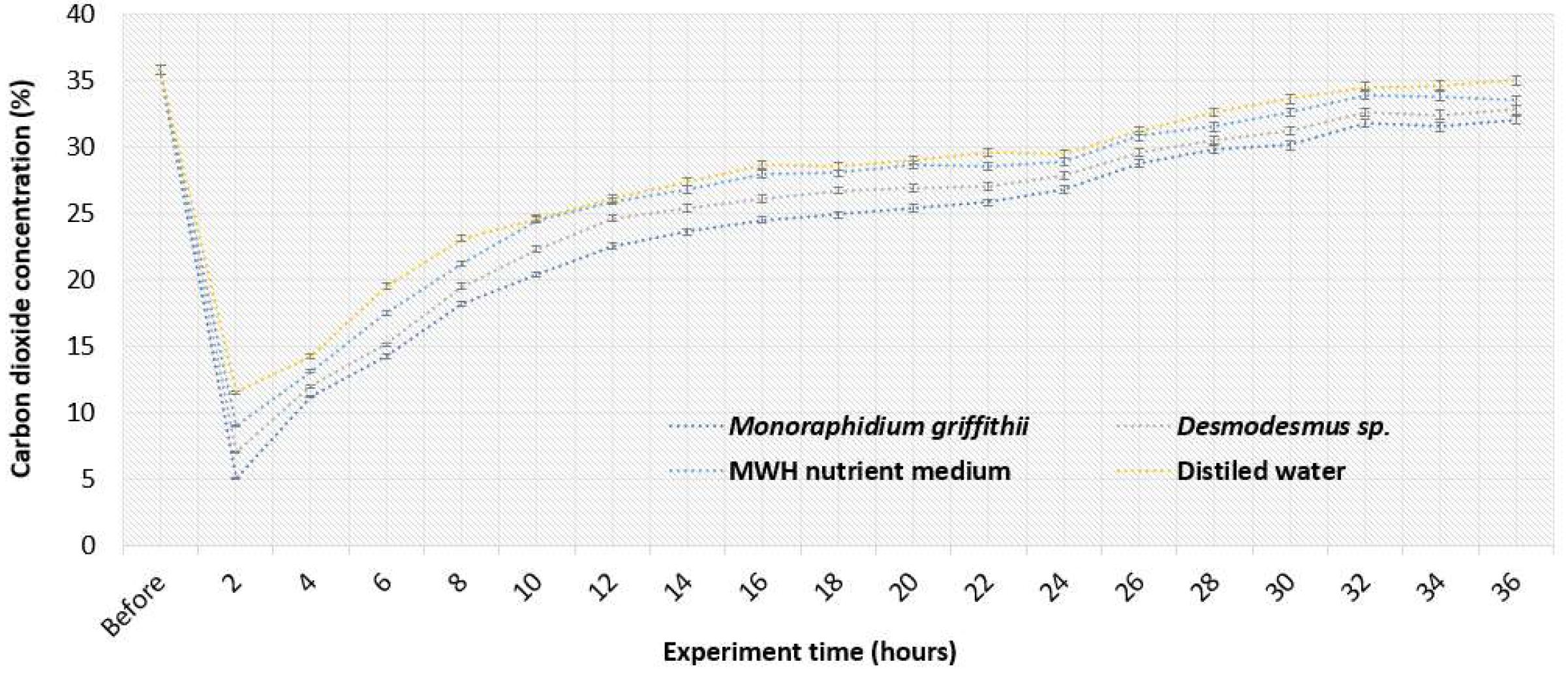

Figure 3 shows how the CO

2 concentration in the biogas varied over time as it passed through different media. The CO

2 removal results show that within the first 2 hours of the experiment, all media achieved a significant reduction in biogas CO

2 concentration, with the largest decrease observed in

Monoraphidium griffithii, where CO

2 levels dropped from 35.8% to 5.0%, resulting in 86.0% removal efficiency. This high efficiency could be attributed to the high solubility of CO

2 in water. In comparison,

Desmodesmus sp. and distilled water achieved CO

2 cleaning efficiencies of 80.4% and 67.9%, respectively, over the same period of time. The MWH medium reduced CO

2 concentration from 35.8% to 9.0%, resulting in the lowest cleaning efficiency of 74.9% at that time point. Compared to other studies, different microalgae species have demonstrated similar CO

2 removal efficiencies from biogas. Study performed by Kao et al. [

39] using outdoor microalgae incroporating PBR showed that CO

2 (20%) capture efficiency by the

Chlorella sp. culture after desulfurized biogas (H

2S < 50 ppm) aeration was 86% at a gas flow rate of 0.05 vvm.

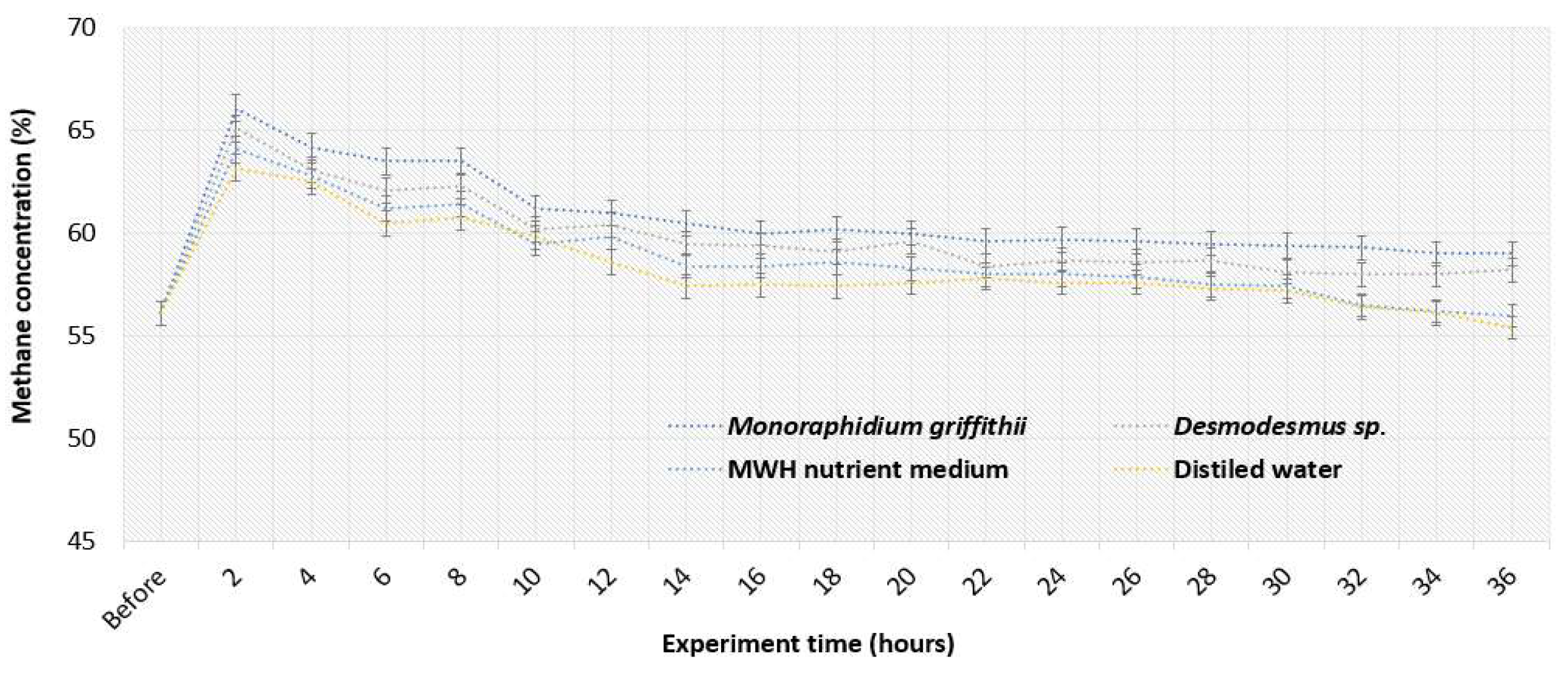

Figure 4 shows how CH

4 concentration in the biogas changed over time as it flowed through various media. Significant changes in CH

4 concentration can be seen within first 2-4 hours of the experiment. Compared to CO

2 the CH

4 gas has significantly lower solubility in distilled water, therefore there was no loss of CH

4 from biogas when its concentration increased from 56.1% to 63.2% within first 2 hours, so the quality of biogas improved, but not as much as with microalgae. The results showed that using

Monoraphidium griffithii, in the beginning (during first 2 hours) CH

4 concentration increased by 15.1% (to 66.1%), whereas when using

Desmodesmus sp. – by 13.8% (to 65.1%). The highest CH

4 concentration was reached with

Monoraphidium griffithii 66.4% (increase of 15.4%) after 4 hours of experiment. At 97% methane, biogas can produce 9.67 kWh [

43], with methane’s energy value at 37.78 MJ/Nm³ [

44]. Using a photobioreactor,

Monoraphidium griffithii and

Desmodesmus sp. can generate 6.59 and 6.49 kWh/Nm³, with biogas energy values reaching 24.97 and 24.59 MJ/Nm³, respectively. Compared to other microalgae species, a higher methane increase can be achieved after biogas upgrading process. For example, one study showed that CH

4 concentration in the biogas effluent from the

Chlorella sp. culture increased from its original 70% to 85-90% [

45]. The enrichment of CH

4 in biogas was contributed to the removal of CO

2.

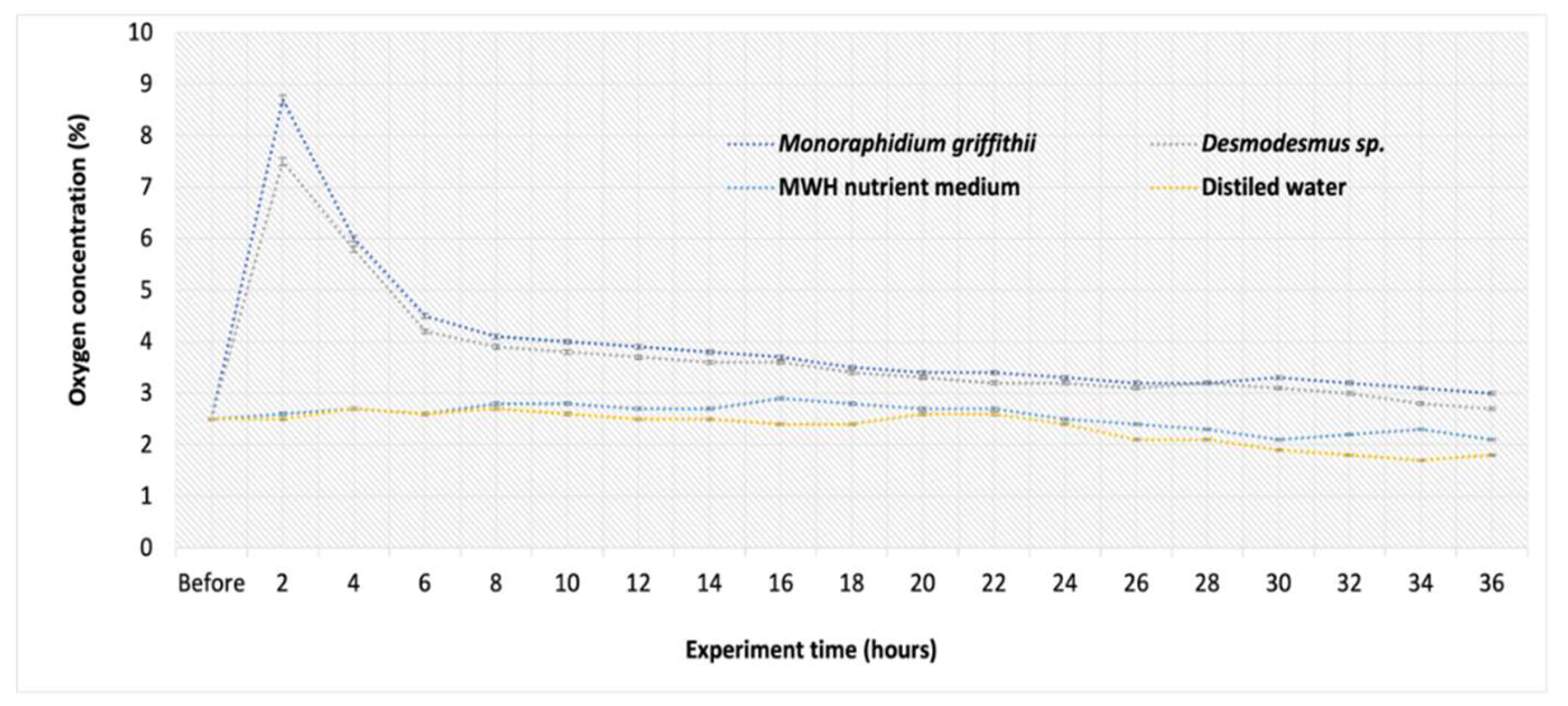

The O

2 results indicate that after 2 hours from the start of the experiment, the O

2 concentration rose at different rates across all media (

Figure 5). The highest O

2 concentration in purified biogas was observed after 2 hours of treatment with

Monoraphidium griffithii, reaching 8.7% (up from 2.6%), which indicates lower biogas quality and safety. At this time point, average O

2 concentrations in

Monoraphidium griffithii and

Desmodesmus sp. were 8.7% and 7.5%, respectively. This rise of O

2 can be attributed to the oxygen produced by microalgae through photosynthesis process. After 36 hours, the O

2 concentration gradually declined, nearing its initial level measured before the experiment, suggesting the biogas reached an intermediate saturation point. However, final O

2 concentration in the upgraded biogas did not meet international regulations for natural gas pipeline network (≤1%) and this technology should be optimized further [

15]. It has also been noted that the presence of H₂S in biogas can lead to sulfur oxidation (formation of SO

2- and H

2O) when O₂ is present, what could also result in a decrease in the O₂ content of the upgraded biogas [

46]. Although H

2S was present in the purified biogas, its amount was probably insufficient (0.0002%) for mentioned reactions to occur.

The graphs above indicate that biogas purification using microalgae, distilled water, and MWH medium effectively reduces CO2 concentrations within a short period of time – 2 hours. However, after this initial phase, the cleaning efficiency of all media declines, and by 32-36 hours, when saturation point is reached, the biogas purification process stops. Thus, to maintain effective biogas purification process over time, the media must be periodically regenerated or replaced. Besides, combining such technologies like water washing and PBR may also be beneficial. However, it was demonstrated that Monoraphidium griffithii contribution to CO2 removal from biogas, excluding water absorption, was only 3.1%. While distilled water alone (representing water physical absorption process) showed strong CO2 removal, it also exhibited high CH4 solubility, leading to significant CH4 losses, which is inefficient for improving biogas quality.

The results of the biomass growth rate are presented in

Table 3. Research revealed that the highest microalgae growth was obtained in the suspension containing

Monoraphidium griffithi, reaching 1.10 g/l/h. During the experiments, a positive microalgae biomass growth rate was determined.

These results demonstrate that both cultures (

Monoraphidium griffithi and

Desmodesmus sp.) can grow well in an indoor PBR aerated directly with biogas. Additionally, microalgae weight growth with time agreeded well with biogas CO

2 removal, suggesting that CO

2 as a carbon source facilitated microalgae growth. A similar trend at relatively high CO

2 level of 20% was observed in other study [

47].

4. Discussion

Microalgae are diverse group of fast-growing microorganisms capable of photoautotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic growth. They can be cultivated on non-fertile land and have CO

2 fixation capacity 10–50 times higher than that of terrestrial plants [

48]. In this context, microalgae offer an efficient method for CO₂ fixation and the generation of valuable products, which can be used in different sectors, including pharmaceutical and cosmetics, wastewater treatment and biogas treatment [

49]. To make microalgal CO

2 fixation applicable to the treatment of actual biogas, some problems should be overcome. Firstly, since concentrations of CO

2 in biogases are usually in the range of 30-50%, one of the step for efficient CO

2 fixation would be increased tolerance of microalgal species to high CO

2 concentrations (20-55%) [

22]. This study results showed that both

Monoraphidium griffithii and

Desmodesmus sp. microalgae species can tolerate CO

2 concentration of 36% and efficiently remove it from the real biogas stream. However, CO

2 saturation point was reached pretty fast (after 32-36 hours), thus in order to prolong exponential phase of algal growth and CO

2 fixation, spent medium should be periodically exchanged with fresh medium [

26]. Usually nitrogen source (nitrate) is consumed more quickly than other medium components and becomes a limiting factor in the early stage of cultivation.

In this study different parameters affecting CO

2 fixation have been analyzed. One of such parameter was redox potential which shows oxidative or reductive state of a system, indicating whether environment is more oxidizing or reducing. Redox potential gives insights into balance between light and dark reactions. High redox potential could indicate oxidative stress, which can be triggered by imbalance between the production of oxidant compounds and the activity of antioxidant defense systems [

50]. Too positive (oxidized) redox potential can lead to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which damage cellular components, including those involved in photosynthesis and CO

2 fixation. Study performed by Ferreira et al. [

50] showed that B3 vitamins not only increased

Chlorella vulgaris biomass, but also increased capacity for CO

2 biofixation. It was also showed that B3 vitamins, regardless of the used source, reduced redox potential in the PBRs from around 400 mV to around 250 mV, therefore can be called as an antioxidant agent. In our study, a similar redox potential (265 mV) was recorded at the end of the study (after 36 hours), so it can be said that the studied PBR systems with different microalgae (e.g.

Monoraphidium griffithii) did not experience oxidative stress, as was shown by the results of increased biomass.

Another important parameter in PBRs with microalgae suspension studies is TDS. TDS shows total dissolved substances (salts, minerals, organic compounds) in water, which can have high impact on microalgae growth, metabolism and CO2 fixation. When TDS is too low, essential nutrients may decrease microalgal growth. However, excessive TDS can imbalance certain ions, which could inhibit growth via osmotic/metabolic stress. Our study results showed that obtained TDS values were sufficient to sustain photosynthetic growth of Monoraphidium griffithii and Desmodesmus sp. within studied PBR. It can be concluded that MWH medium contained enough dissolved nutrients to support microalgae growth.

The CO

2 gas concentration consistently increased until 18-20 hour of our experiment, at which point it stabilised and nearly matched pre-experimental concentration. This likely represents CO

2 saturation point, beyond which the medium can no longer be purified effectively and requires regeneration or replacement in the columns. Comparing results of the 36-hour distilled water trial (representing water physical absorption) with microalgae trial (representing the PBR), it is possible to assess CO

2 removal efficiency, excluding water’s impact. Distilled water achieved CO

2 concentration of 35.0%,

Monoraphidium griffithii reached 32.0% and

Desmodesmus sp. also achieved 32.0%. The CO

2 concentration after treatment with

Monoraphidium griffithii was 0.7% lower than with distilled water, indicating

Monoraphidium griffithii contributed only 3.1% to CO

2 removal excluding impact of physical water absorption. On the other hand, CO

2 levels after treatment with

Desmodesmus sp. were 2.2% higher than with distilled water, meaning that

Desmodesmus sp. was less effective in CO

2 removal. Other study showed that

Scenedesmus sp. could simultaneously assimilate biogas CO

2 and organic carbon from digestate. When the digestate concentration was 5 g COD/L, it achieved the highest algal biomass concentration, COD removal, and bio-CO

2 fixation efficiency with values of 1.79 g/L, 69.1% and 98.2%, respectively, over a 10-day cultivation period [

51].

The concentrations of CO2 and CH4 in biogas are influenced by the biogas residence time within the PBR. During the experiments, it was observed that biogas remained in the PBR for 5.5 seconds. The increase in O2 concentration as biogas passed through the macroalgae columns demonstrated the microalgae’s activity. This effectiveness was further evidenced by pH measurements. When biogas passes through the water, it becomes saturated with CO2, necessitating water regeneration. Meanwhile, macroalgae absorb inorganic carbon from CO2, reducing the CO2 concentration in the biogas while increasing O2 levels. Our experiments confirmed this effect.

An increase in CH

4 concentration was observed from 2 to 4 hours across all media. Basically, beyond this period and until the end of the experiment, the CH

4 concentration gradually decreased across all media, returning to its nearly initial level by 32-36 hours. Since values remained steady between 32-36 hours, it can be assumed that the media reached methane’s solubility limits (saturation point). Similarly, as previously was shown in

Figure 3, the CO

2 saturation point was also reached after 32-36 hours. For CO

2, the the process kinetics limit the process until all carbonate reactants are enganged, along with the flow of the water volume [

52].

Attention should be given to changes in O

2 concentration in biogas over time, as was shown in

Figure 5, because biogas containing 6-12% O

2 (depending on CH

4 concentration) can be explosive [

53]. Therefore, maintaining the O

2 concentration at 1% or lower is preferable.