Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

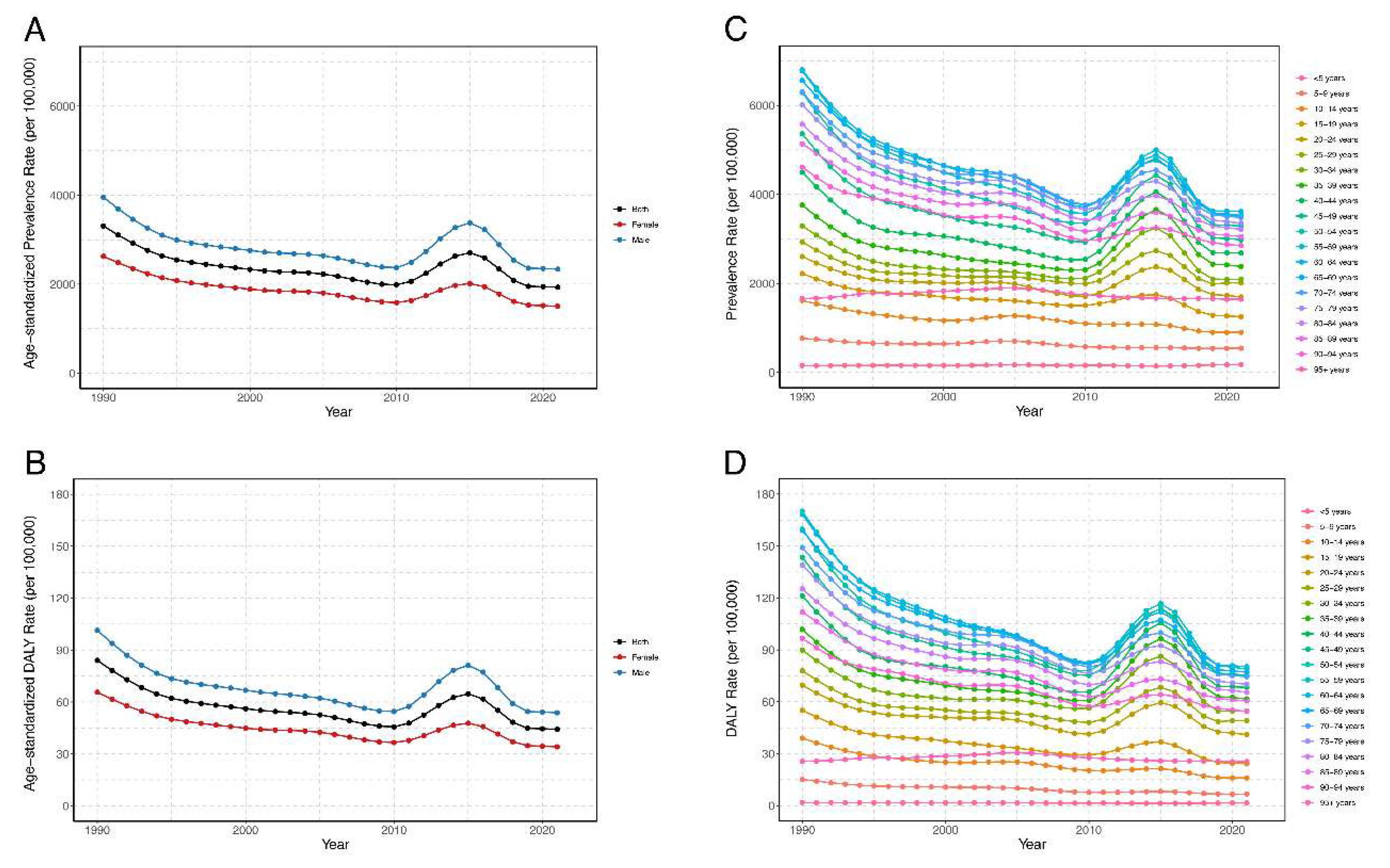

3.1. Prevalence and DALYs of Food-Borne Trematodiases in China from 1990 to 2021

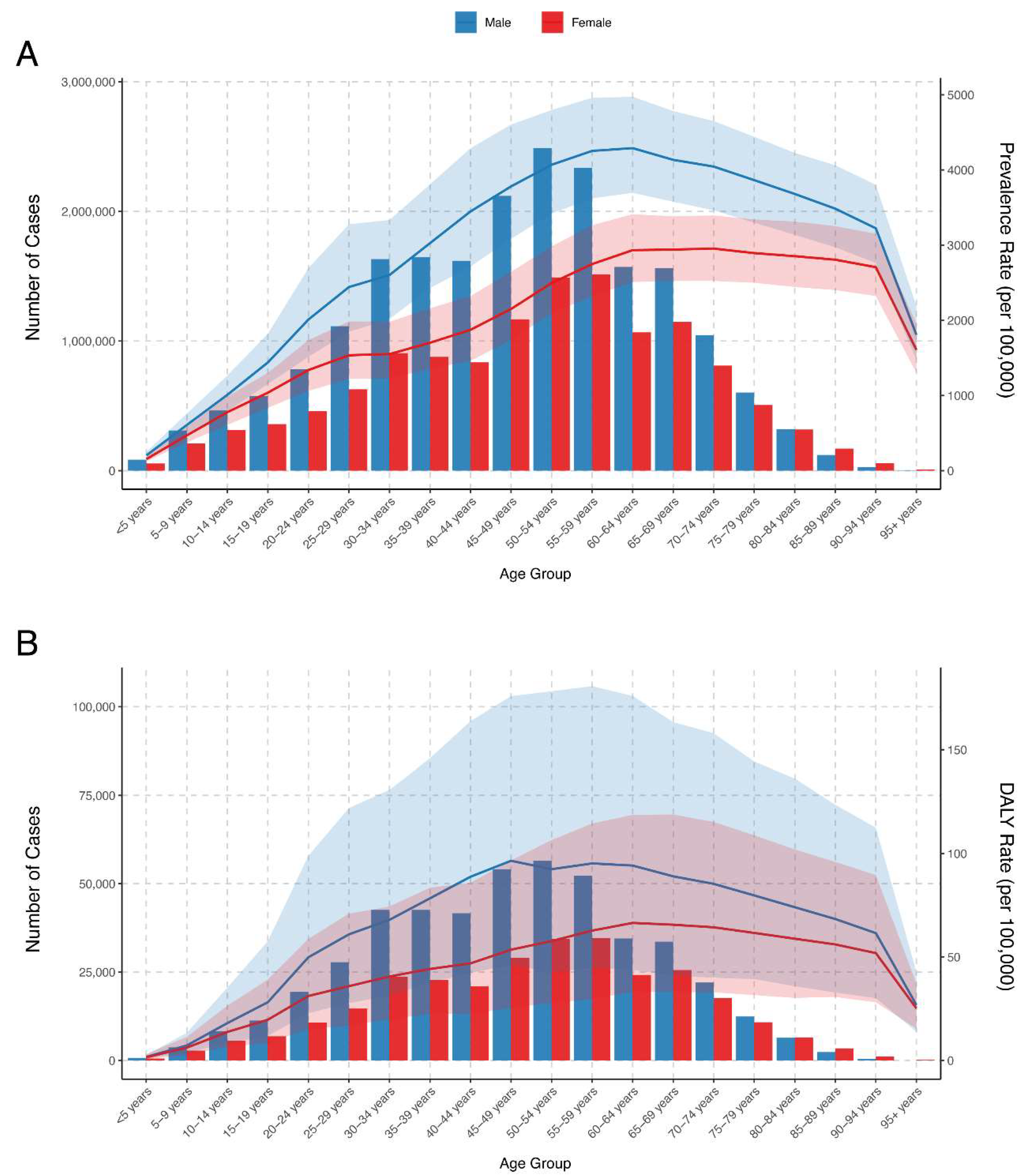

3.2. Age-specific Prevalence and DALYs of Food-Borne Trematodiases in China from 1990 to 2021

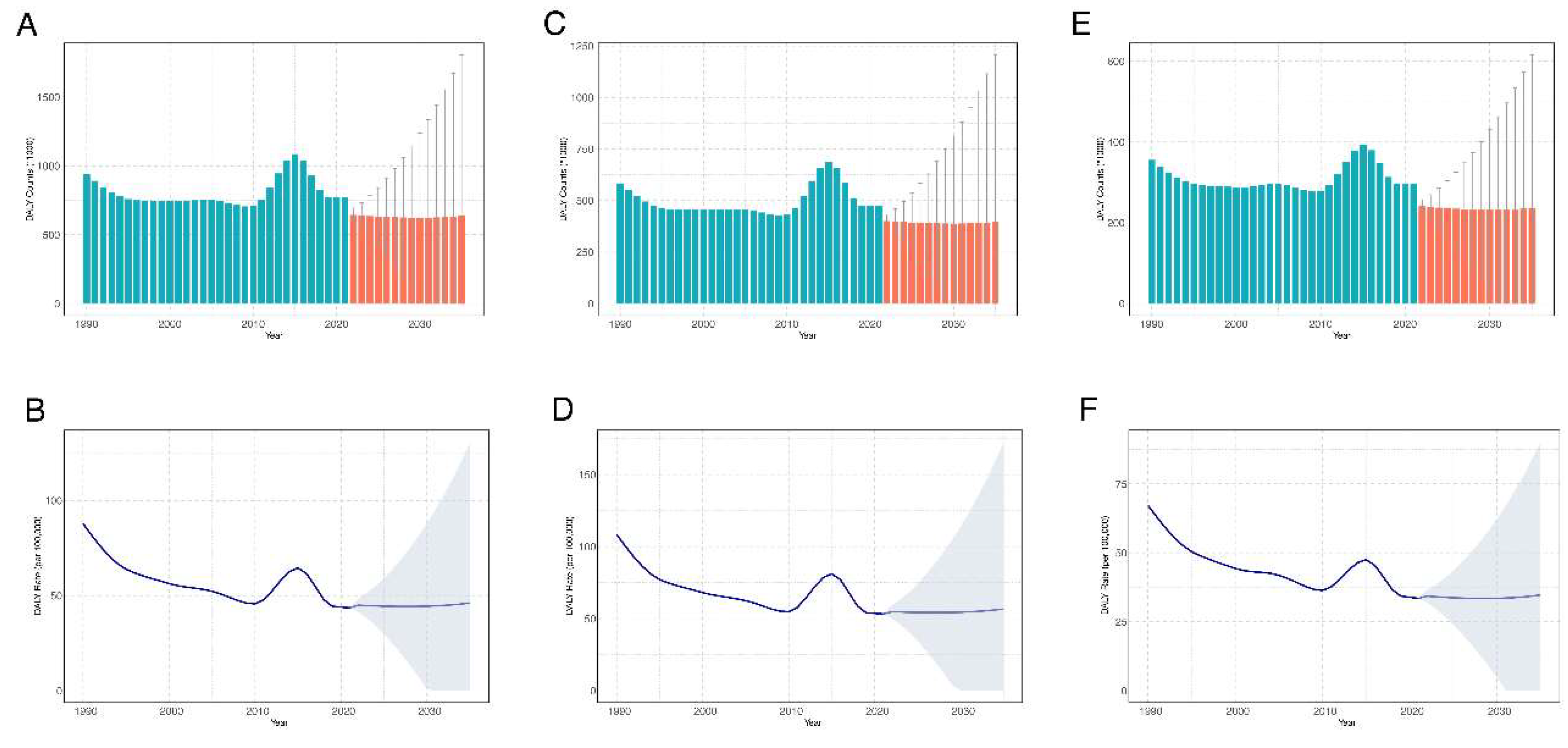

3.3. Projected DALYs of Food-Borne Trematodiases in China through 2035

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fürst T, Duthaler U, Sripa B, Utzinger J, Keiser J. Trematode infections: liver and lung flukes. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26[2]:399-419.

- Fürst T, Sayasone S, Odermatt P, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Manifestation, diagnosis, and management of foodborne trematodiasis. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2012;344:e4093.

- Fürst T, Yongvanit P, Khuntikeo N, Lun Z-R, Haagsma JA, Torgerson PR, Odermatt P, Bürli C, Chitnis N, Sithithaworn P. Food-borne Trematodiases in East Asia: Epidemiology and Burden. In: Utzinger J, Yap P, Bratschi M, Steinmann P, editors. Neglected Tropical Diseases - East Asia. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 13-38.

- World Health Organization. Foodborne Trematodiases (Chapter 4.7). Investing to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: third WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. p. 105–9.

- Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Intapan PM, Maleewong W, Brindley PJ. Food-borne trematodiases in Southeast Asia: epidemiology, pathology, clinical manifestation and control. Advances in parasitology. 2010;72:305-50.

- Keiser J, Utzinger Jr. Food-borne trematodiases. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2009;22[3]:466-83.

- Toledo R, Esteban JG, Fried B. Current status of food-borne trematode infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31[8]:1705-18.

- World Health Organization. DALY Estimates: Parasites (Chapter 5.4). WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007-2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. p. 86.

- World Health Organization. 2030 targets and milestones (Chapter 2). Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. p. 12-23.

- Wei DX, Yang WY, Huang SQ, Lu YF, Su TC, Ma JH, Hu WX, Xie NF. Parasitological investigation on the ancient corpse of the Western Han Dynasty unearthed from tomb No. 168 on Phoenix Hill in Jiangling county. Acta Acad Med Wuhan. 1981;1[2]:16-23.

- Chen YD, Zhou CH, Xu LQ. Analysis of the results of two nationwide surveys on Clonorchis sinensis infection in China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2012;25[2]:163-6.

- Qian M-B, Chen J, Bergquist R, Li Z-J, Li S-Z, Xiao N, Utzinger J, Zhou X-N. Neglected tropical diseases in the People's Republic of China: progress towards elimination. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2019;8[1]:86.

- Zhou, XN. Report on the national survey of important human parasitic diseases in China [2015]. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2018.

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403[10440]:2133-61.

- GBD 2021 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific mortality, life expectancy, and population estimates in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1950-2021, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403[10440]:1989-2056.

- Flaxman AD, Vos T, Murray CJ. An integrative metaregression framework for descriptive epidemiology. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press; 2015.

- Rue H, Martino S, Chopin N. Approximate Bayesian inference for latent Gaussian models by using integrated nested Laplace approximations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology. 2009;71[2]:319-92. [CrossRef]

- Knoll M, Furkel J, Debus J, Abdollahi A, Karch A, Stock C. An R package for an integrated evaluation of statistical approaches to cancer incidence projection. BMC medical research methodology. 2020;20:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Liu N, Yang D-W, Wu Y-X, Xue W-Q, Li D-H, Zhang J-B, He Y-Q, Jia W-H. Burden, trends, and risk factors for breast cancer in China from 1990 to 2019 and its predictions until 2034: an up-to-date overview and comparison with those in Japan and South Korea. BMC Cancer. 2022;22[1]:826. [CrossRef]

- Wu B, Li Y, Shi B, Zhang X, Lai Y, Cui F, Bai X, Xiang W, Geng G, Liu B. Temporal trends of breast cancer burden in the Western Pacific Region from 1990 to 2044: Implications from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Journal of Advanced Research. 2024;59:189-99. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S-X, Yang G-B, Zhang R-J, Zheng J-X, Yang J, Lv S, Duan L, Tian L-G, Chen M-X, Liu Q. Global, regional, and national burden of dengue, 1990–2021: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. Decoding Infection and Transmission. 2024;2:100021.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Population Prospects 2024, Online Edition. [Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022.

- Wang Y-P, Zhou X-N. The year 2020, a milestone in breaking the vicious cycle of poverty and illness in China. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2020;9[1]:11.

- Zhang H, Liu C, Zheng Q. Development and application of anthelminthic drugs in China. Acta Tropica. 2019;200:105181.

- Huang Y, Huang D, Geng Y, Fang S, Yang F, Wu C, Zhang H, Wang M, Zhang R, Wang X. An integrated control strategy takes Clonorchis sinensis under control in an endemic area in South China. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2017;17[12]:791-8.

- Chen Y-D, Li H-Z, Xu L-Q, Qian M-B, Tian H-C, Fang Y-Y, Zhou C-H, Ji Z, Feng Z-J, Tang M, Li Q, Wang Y, Bergquist R, Zhou X-N. Effectiveness of a community-based integrated strategy to control soil-transmitted helminthiasis and clonorchiasis in the People's Republic of China. Acta Tropica. 2021;214:105650.

- Song L, Xie Q, Lv Z. Foodborne parasitic diseases in China: a scoping review on current situation, epidemiological trends, prevention and control. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2021;14[9]:385-400.

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. National Plan for the Prevention and Control of Echinococcosis and Other Important Parasitic Diseases (2016-2020) [Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s5873/201702/dda5ffe3f50941a29fb0aba6233bb497.shtml.

- Qian MB, Chen YD, Zhu HH, Zhu TJ, Zhou CH, Zhou XN. Establishment and role of national clonorchiasis surveillance system in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2018;39[11]:1496-500.

- Fürst T, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Global burden of human food-borne trematodiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2012;12[3]:210-21.

- Zeng T, Lü S, Tian L, Li S, Sun L, Jia T. Temporal trends in disease burden of major human parasitic diseases in China from 1990 to 2019. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2023;35[1].

- Zhu T-J, Chen Y-D, Qian M-B, Zhu H-H, Huang J-L, Zhou C-H, Zhou X-N. Surveillance of clonorchiasis in China in 2016. Acta Tropica. 2020;203:105320.

- Choi M-H, Park SK, Li Z, Ji Z, Yu G, Feng Z, Xu L, Cho S-Y, Rim H-J, Lee S-H, Hong S-T. Effect of control strategies on prevalence, incidence and re-infection of clonorchiasis in endemic areas of China. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2010;4[2]:e601.

- National Disease Control and Prevention Administration. National Comprehensive Implementation Plan for the Prevention and Control of Echinococcosis and Other Important Parasitic Diseases (2024-2030) 2024 [Available from: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202405/content_6950309.htm.

| Parameter | Number | Percentage change(%) | Age-standardized rate (per 100 000 population) | EAPC (95% CI, %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 (95%UI) | 2021 (95%UI) | 1990 (95%UI) | 2021 (95%UI) | |||

| Prevalence | ||||||

| Both | 36621225.1 (31239359.0, 43237071.8) | 33317222.7 (29251038.7, 38353602.0) | -9.02 | 3307.89 (2845.59, 3875.81) | 1930.21 (1700.47, 2240.51) | -0.96 (-1.34, -0.57) |

| Male | 22476187.2 (19095640.6, 26580789.7) | 20418481.9 (17785189.7, 23654614.6) | -9.16 | 3954.06 (3377.44, 4640.68) | 2337.02 (2042.27, 2718.69) | -0.81 (-1.24, -0.38) |

| Female | 14145037.9 (12067609.2, 16774017.0) | 12898740.8 (11350526.9, 14870728.4) | -8.81 | 2626.23 (2255.27, 3066.96) | 1506.51 (1328.58, 1743.02) | -1.17 (-1.48, -0.85) |

| DALYs | ||||||

| Both | 938172.2 (365200.0, 1876414.7) | 768297.4 (383882.8, 1367826.1) | -18.11 | 84.04 (32.98, 168.04) | 44.17 (22.08, 79.87) | -1.21 (-1.65, -0.77) |

| Male | 582518.0 (224509.7, 1168057.0) | 472583.6 (231736.8, 849985.0) | -18.87 | 101.43 (39.26, 203.48) | 53.80 (26.54, 98.11) | -1.08 (-1.57, -0.59) |

| Female | 355654.2 (137444.6, 708492.9) | 295713.8 (151020.2, 519060.0) | -16.85 | 65.63 (25.81, 129.90) | 34.10 (17.27, 60.67) | -1.39 (-1.75, -1.04) |

| Age group | Number | Percentage change(%) | Prevalence rate (per 100 000 population) | EAPC (95% CI, %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 (95%UI) | 2021 (95%UI) | 1990 (95%UI) | 2021 (95%UI) | |||

| <5 years | 171914.5 (144671.2, 208443.7) | 139694.9 (114532.1, 171235.8) | -18.74 | 153.76 (129.39, 186.43) | 179.86 (147.46, 220.47) | 0.05 (-0.14, 0.24) |

| 5-9 years | 799728.8 (615585.6, 1010084.7) | 520272.9 (418052.3, 648896.7) | -34.94 | 766.92 (590.33, 968.65) | 543.25 (436.52, 677.55) | -0.99 (-1.17, -0.81) |

| 10-14 years | 1653399.4 (1218426.7, 2149169.6) | 776875.7 (610532.1, 979481.6) | -53.01 | 1616.35 (1191.12, 2101.01) | 901.32 (708.33, 1136.38) | -1.46 (-1.66, -1.26) |

| 15-19 years | 2812747.8 (2142971.6, 3626489.7) | 936264.0 (753794.3, 1173989.0) | -66.71 | 2220.62 (1691.84, 2863.05) | 1253.83 (1009.47, 1572.19) | -1.17 (-1.44, -0.91) |

| 20-24 years | 3436931.0 (2608526.7, 4458216.2) | 1240725.6 (955563.4, 1634296.6) | -63.90 | 2603.72 (1976.14, 3377.41) | 1695.58 (1305.88, 2233.43) | -0.63 (-0.98, -0.27) |

| 25-29 years | 3219883.5 (2475118.3, 4211276.7) | 1741653.7 (1345850.6, 2298166.3) | -45.91 | 2930.11 (2252.37, 3832.28) | 2013.89 (1556.22, 2657.39) | -0.40 (-0.78, -0.02) |

| 30-34 years | 2903003.4 (2268678.5, 3779118.4) | 2538187.6 (1984320.7, 3241193.0) | -12.57 | 3289.73 (2570.91, 4282.56) | 2095.02 (1637.86, 2675.28) | -0.39 (-0.91, 0.13) |

| 35-39 years | 3435818.6 (2709447.3, 4304031.1) | 2523380.2 (2014491.7, 3165399.0) | -26.56 | 3761.61 (2966.36, 4712.15) | 2381.37 (1901.12, 2987.26) | -0.41 (-0.95, 0.13) |

| 40-44 years | 3017969.3 (2405475.4, 3666181.0) | 2454304.9 (1957302.9, 3031967.6) | -18.68 | 4498.10 (3585.21, 5464.22) | 2681.31 (2138.34, 3312.41) | -0.64 (-1.19, -0.08) |

| 45-49 years | 2768369.1 (2274417.5, 3393964.6) | 3287197.4 (2690789.9, 4014219.7) | 18.74 | 5363.09 (4406.17, 6575.04) | 2979.65 (2439.04, 3638.65) | -0.93 (-1.44, -0.41) |

| 50-54 years | 3001413.2 (2502700.4, 3644828.9) | 3978362.9 (3342141.3, 4704312.9) | 32.55 | 6290.84 (5245.56, 7639.41) | 3291.74 (2765.32, 3892.40) | -1.23 (-1.71, -0.75) |

| 55-59 years | 2939965.3 (2472520.4, 3529015.9) | 3847655.0 (3277996.9, 4521053.7) | 30.87 | 6778.94 (5701.11, 8137.17) | 3499.70 (2981.56, 4112.20) | -1.37 (-1.81, -0.93) |

| 60-64 years | 2403019.1 (2035702.1, 2875610.9) | 2638368.9 (2267403.2, 3068835.9) | 9.79 | 6800.20 (5760.75, 8137.57) | 3613.95 (3105.81, 4203.59) | -1.42 (-1.79, -1.06) |

| 65-69 years | 1789766.7 (1518589.8, 2133235.4) | 2706401.5 (2339545.7, 3102609.6) | 51.22 | 6560.29 (5566.31, 7819.26) | 3528.39 (3050.12, 4044.94) | -1.41 (-1.72, -1.09) |

| 70-74 years | 1185961.6 (1003456.2, 1409151.9) | 1856504.5 (1589514.4, 2120836.3) | 56.54 | 6302.39 (5332.53, 7488.46) | 3483.36 (2982.40, 3979.32) | -1.33 (-1.60, -1.07) |

| 75-79 years | 684429.1 (580074.5, 817345.2) | 1109850.9 (951457.8, 1267878.7) | 62.16 | 6013.95 (5097.00, 7181.86) | 3351.11 (2872.85, 3828.26) | -1.31 (-1.56, -1.06) |

| 80-84 years | 295455.9 (248823.4, 352100.8) | 636509.6 (542502.1, 736544.2) | 115.43 | 5577.66 (4697.33, 6647.02) | 3216.02 (2741.04, 3721.45) | -1.28 (-1.51, -1.05) |

| 85-89 years | 86628.4 (72630.0, 103491.8) | 290944.6 (248501.3, 338972.4) | 235.85 | 5135.49 (4305.64, 6135.19) | 3054.30 (2608.73, 3558.48) | -1.32 (-1.53, -1.11) |

| 90-94 years | 14148.4 (11764.8, 17181.7) | 83548.5 (71718.7, 97227.5) | 490.52 | 4611.27 (3834.40, 5599.90) | 2849.55 (2446.08, 3316.10) | -1.28 (-1.44, -1.11) |

| 95+ years | 672.0 (561.3, 792.9) | 10519.3 (8546.3, 12752.3) | 1465.37 | 1659.66 (1386.12, 1958.21) | 1645.97 (1337.24, 1995.35) | -0.19 (-0.35, -0.02) |

| Age group | Number | Percentage change(%) | DALY rate (per 100 000 population) | EAPC (95% CI,%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 (95%UI) | 2021 (95%UI) | 1990 (95%UI) | 2021 (95%UI) | |||

| <5 years | 2031.6 (1081.8, 3458.7) | 1227.1 (633.5, 1972.2) | -39.60 | 1.82 (0.97, 3.09) | 1.58 (0.82, 2.54) | -0.74 (-0.90, -0.57) |

| 5-9 years | 15797.3 (6328.7, 32927.4) | 6441.4 (3175.8, 11675.0) | -59.22 | 15.15 (6.07, 31.58) | 6.73 (3.32, 12.19) | -2.31 (-2.51, -2.10) |

| 10-14 years | 39857.1 (14192.0, 86405.5) | 13801.5 (6714.9, 26475.6) | -65.37 | 38.96 (13.87, 84.47) | 16.01 (7.79, 30.72) | -2.28 (-2.51, -2.05) |

| 15-19 years | 69811.7 (24070.1, 148812.0) | 18072.2 (7724.6, 37470.3) | -74.11 | 55.12 (19.00, 117.48) | 24.20 (10.34, 50.18) | -1.83 (-2.19, -1.47) |

| 20-24 years | 91807.6 (34189.3, 191422.8) | 30048.7 (14278.4, 58379.7) | -67.27 | 69.55 (25.90, 145.02) | 41.06 (19.51, 79.78) | -0.87 (-1.27, -0.47) |

| 25-29 years | 85671.9 (31447.9, 169654.0) | 42446.5 (19397.0, 87010.0) | -50.45 | 77.96 (28.62, 154.39) | 49.08 (22.43, 100.61) | -0.64 (-1.06, -0.22) |

| 30-34 years | 79295.9 (31337.0, 160702.4) | 66289.6 (32003.2, 125248.6) | -16.40 | 89.86 (35.51, 182.11) | 54.72 (26.42, 103.38) | -0.49 (-1.01, 0.04) |

| 35-39 years | 92973.1 (36213.0, 189105.5) | 65380.4 (31594.7, 123636.0) | -29.68 | 101.79 (39.65, 207.04) | 61.70 (29.82, 116.68) | -0.51 (-1.05, 0.04) |

| 40-44 years | 81304.9 (30671.0, 163233.2) | 62564.1 (29975.6, 114785.1) | -23.05 | 121.18 (45.71, 243.29) | 68.35 (32.75, 125.40) | -0.77 (-1.34, -0.21) |

| 45-49 years | 74077.2 (27619.0, 147619.4) | 83120.4 (38906.2, 150098.9) | 12.21 | 143.51 (53.51, 285.98) | 75.34 (35.27, 136.06) | -1.08 (-1.60, -0.56) |

| 50-54 years | 76218.4 (28809.0, 157441.2) | 90924.1 (43634.0, 175210.7) | 19.29 | 159.75 (60.38, 329.99) | 75.23 (36.10, 144.97) | -1.51 (-2.02, -1.00) |

| 55-59 years | 73736.4 (27983.8, 150512.0) | 86778.8 (41879.9, 162705.9) | 17.69 | 170.02 (64.52, 347.05) | 78.93 (38.09, 147.99) | -1.65 (-2.11, -1.18) |

| 60-64 years | 59478.0 (23670.0, 119142.2) | 58659.0 (28705.5, 105542.6) | -1.38 | 168.31 (66.98, 337.16) | 80.35 (39.32, 144.57) | -1.71 (-2.13, -1.30) |

| 65-69 years | 43396.6 (17667.0, 88027.8) | 59120.3 (29032.5, 107203.1) | 36.23 | 159.07 (64.76, 322.66) | 77.08 (37.85, 139.76) | -1.69 (-2.05, -1.33) |

| 70-74 years | 28064.7 (11468.3, 56576.6) | 39708.1 (19789.4, 71793.7) | 41.49 | 149.14 (60.94, 300.66) | 74.50 (37.13, 134.71) | -1.61 (-1.92, -1.30) |

| 75-79 years | 15814.9 (6682.0, 31495.1) | 23228.6 (11931.7, 40927.0) | 46.88 | 138.96 (58.71, 276.74) | 70.14 (36.03, 123.58) | -1.58 (-1.87, -1.29) |

| 80-84 years | 6640.7 (2915.3, 13102.9) | 12959.5 (6550.4, 22750.2) | 95.15 | 125.36 (55.04, 247.36) | 65.48 (33.10, 114.95) | -1.54 (-1.81, -1.27) |

| 85-89 years | 1887.1 (822.7, 3588.0) | 5765.8 (3041.6, 9965.5) | 205.54 | 111.87 (48.77, 212.70) | 60.53 (31.93, 104.62) | -1.55 (-1.80, -1.31) |

| 90-94 years | 296.6 (134.6, 563.1) | 1598.4 (848.5, 2809.7) | 438.91 | 96.68 (43.85, 183.51) | 54.52 (28.94, 95.83) | -1.49 (-1.69, -1.29) |

| 95+ years | 10.4 (6.4, 15.0) | 162.7 (101.1, 234.1) | 1464.42 | 25.62 (15.90, 37.11) | 25.46 (15.81, 36.64) | -0.19 (-0.40, 0.03) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).