Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Diagnosis of Malaria

2.1. Traditional Diagnostics Methods

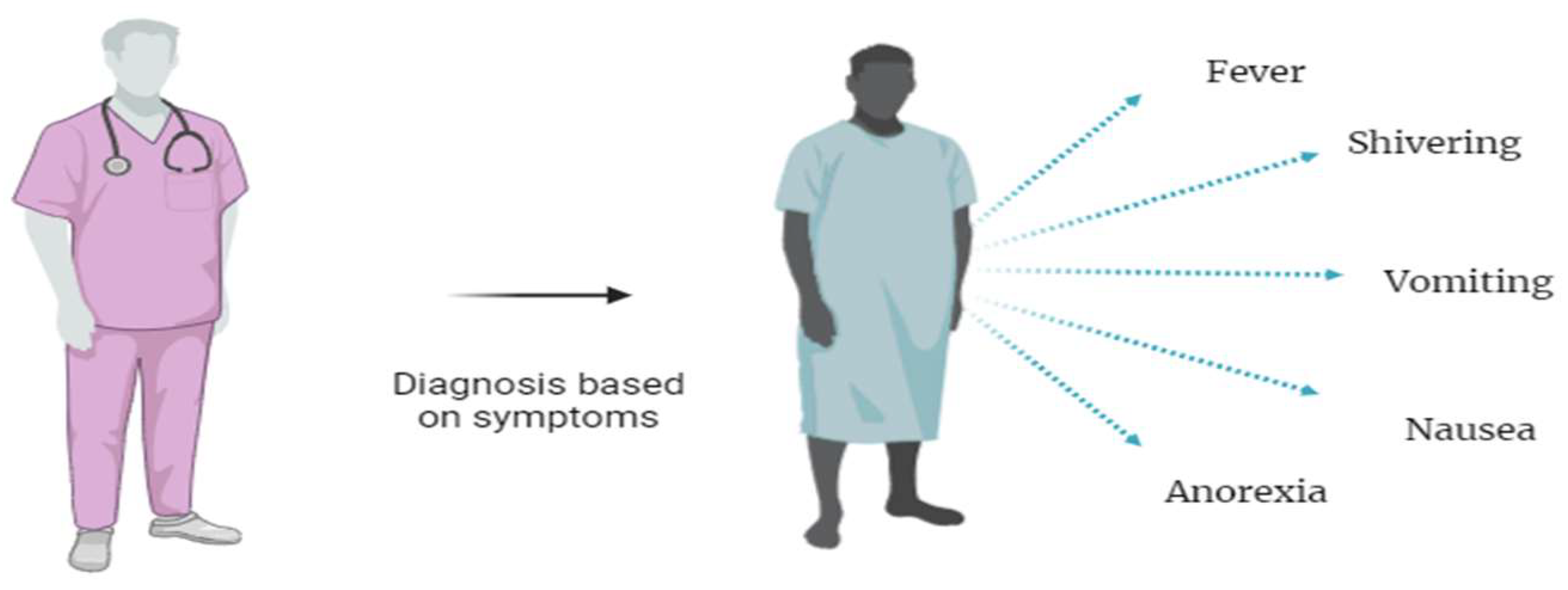

2.1.1. Clinical Diagnosis of Malaria

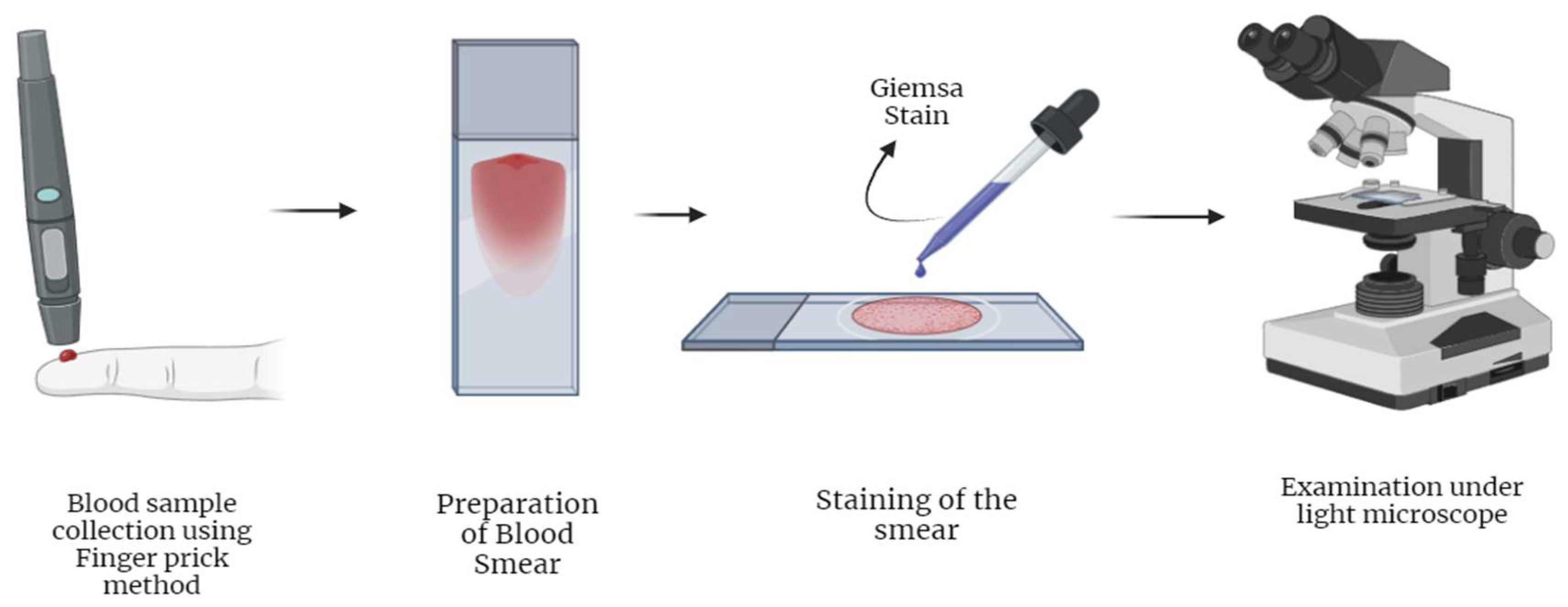

2.1.2. Light Microscopy Based Diagnosis of Malaria

| Diagnostic technique | Advantages | Disadvantages | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Diagnostics methods | ||||

| Clinical Diagnosis | (i) No instrument or specific facility required [18,19] | (i) Challenging to differentiate from other tropical illness[18,19] | 17.2 % [20] | 86.5 % [20] |

| (ii) Only symptoms based [18,19] | ||||

| Microscopic examination | (i) Availability [1,25] | (i) Requires expert personnel [1,26,30] | 56 % [58] | 100 % [58] |

| (ii) Low-cost diagnosis [1,25] | (ii) Results are expert-dependent [1,26,30] | |||

| (iii) Parasite level calculations [29,30,32] | (iii) Thin vs thick blood film variations [1,28- 32, 61] | |||

| (iv)Species identification [1,27,29,30,31,32] | ||||

| Serology | (i) Seroprevalence study [1,34] | (i) Non-reliable diagnostic technique [35] | ||

| (ii) Malaria transmission [1,35] | (ii) Not indicative of active infection [35] | |||

| (iii) screening of potential blood donors[ 1,34] | ||||

| Advanced Diagnostic Methods | ||||

| Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) | (i) Fast preparation and diagnosis results [1,49,54,59] | (i) pfHRP2/3 gene deletions [49, 59,62,63] | 84.2% [55] | 99.8% [55] |

| (ii) Easy handling [1,49,54,59] | (ii) Low sensitivity with low parasite levels [49,59] | 63.4-100% [56] | 53.4-99.9% [56] | |

| (iii) Low-cost diagnosis [1,49,59] | (iii) Low sensitivity with P. ovale and P. malariae species [45,54]. | 84.2% [57] | 95.2%[57] | |

| (iv) Species identification [45,49,59] (usually P. falciparum from non-P. falciparum species) | (iv) Cross-reactivity [45,63] | 37–88% [58] | 93–100%[58] | |

| (v) Prozone effect [49,60] | 95% (HRP2)[11] | 95.2%(HRP2) [11] 98.5%(pLDH) [11] | ||

| 93.2% (pLDH) [11] | ||||

| Quantitative Buffy Coat (QBC) | (i) simple, reliable, and user-friendly [1,67,68,70,72] | (i) Requires expert personnel [1,67] | 70.5% [57] | 92.1%[57] |

| (ii) Rapid and sensitive [1,66,67,68,70] | (ii) Requires fluorescent microscopy set up [1,67] | 55.9 %[67] | 88.8 %[67] | |

| (iii) High specificity [65,66] | (iii) low sensitivity in field [70] | 93 % [69] | 99% [69] | |

| (iv) Less training time [66] | 97.7 %[70] | 99.7 %[70] | ||

| 70.9 %[70] (field) | 97.4 %[70] (field) | |||

| PCR | (i) High sensitivity and specificity [30,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91] | (i) Specialized instrumentation [1,30,84,85,91] | 100% [84,90,91] | 100% [84,90,91] |

| (ii) Accurate Species identification [84,85,86,87,88,91] | (ii) Difficult implementation in endemic areas [30,84,85,87,91] | |||

| (iii) Reference tool for comparative studies [84,90,91] | (iii) Expensive diagnosis [1,30,84,85,88,91] | |||

| (iv) Works in low parasite density [87,88,89,91] | ||||

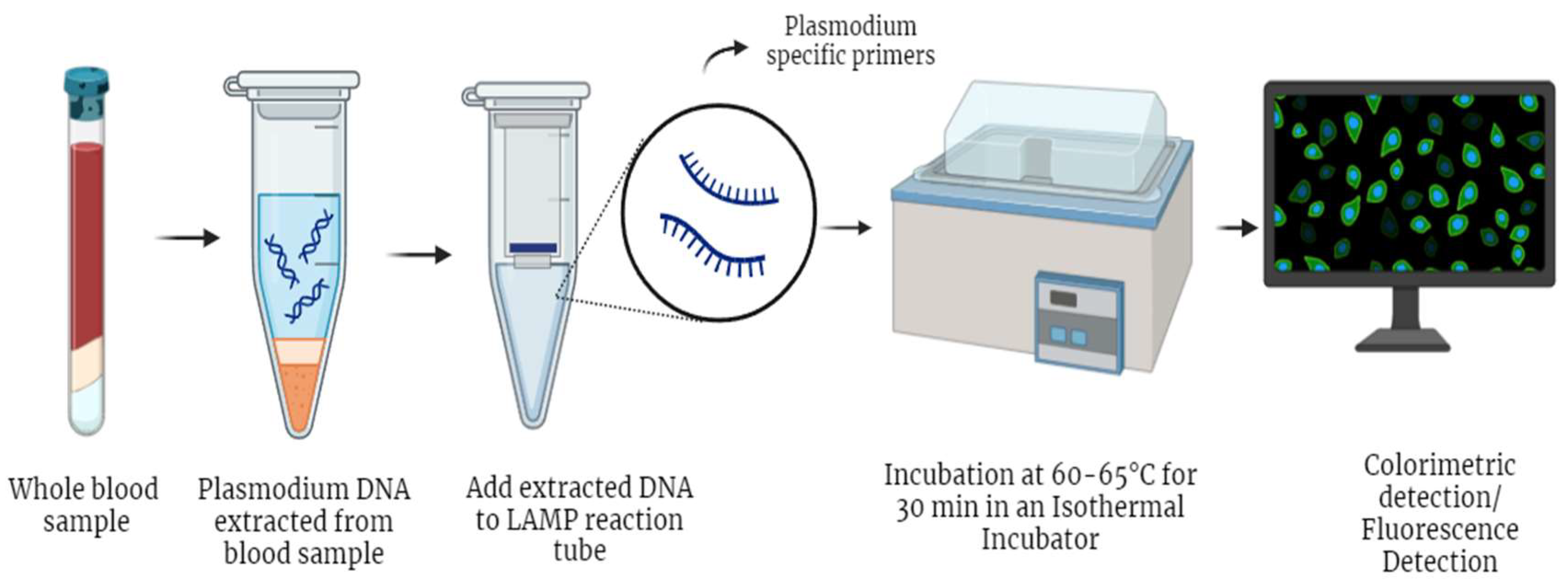

| LAMP | (i) High sensitivity and specificity [92,94,95,96,97] | (i) Less sensitive for other species (other than P. falciparum and P. vivax) [97] | 99 % (Pan) [96] | 100%(Pan)[96] |

| (ii) Species identification [94,96,97] | 90%(P. falciparum) [96] | 93%(P. falciparum) [96] | ||

| (iii) Inexpensive, No thermocyclers needed [92,94,95] | 95% [92] | 99% [92] | ||

| (iv) Less turnaround time, comparable to RDT [94] | 98.89% [94] | 100% [94] | ||

| 100% [58] | 86–99% [58] | |||

| 95–98% [95] | 91–99% [95] | |||

| Mass Spectrometry | (i) High specificity [102,103] | (i) Low sensitivity [102,103] | 52 % [101] | 92 % [101] |

| (ii) Early detection of infection [100] | (ii) Specialized and costly instrumentation [102, 103] | 80.2 % [102] | >95% [102] | |

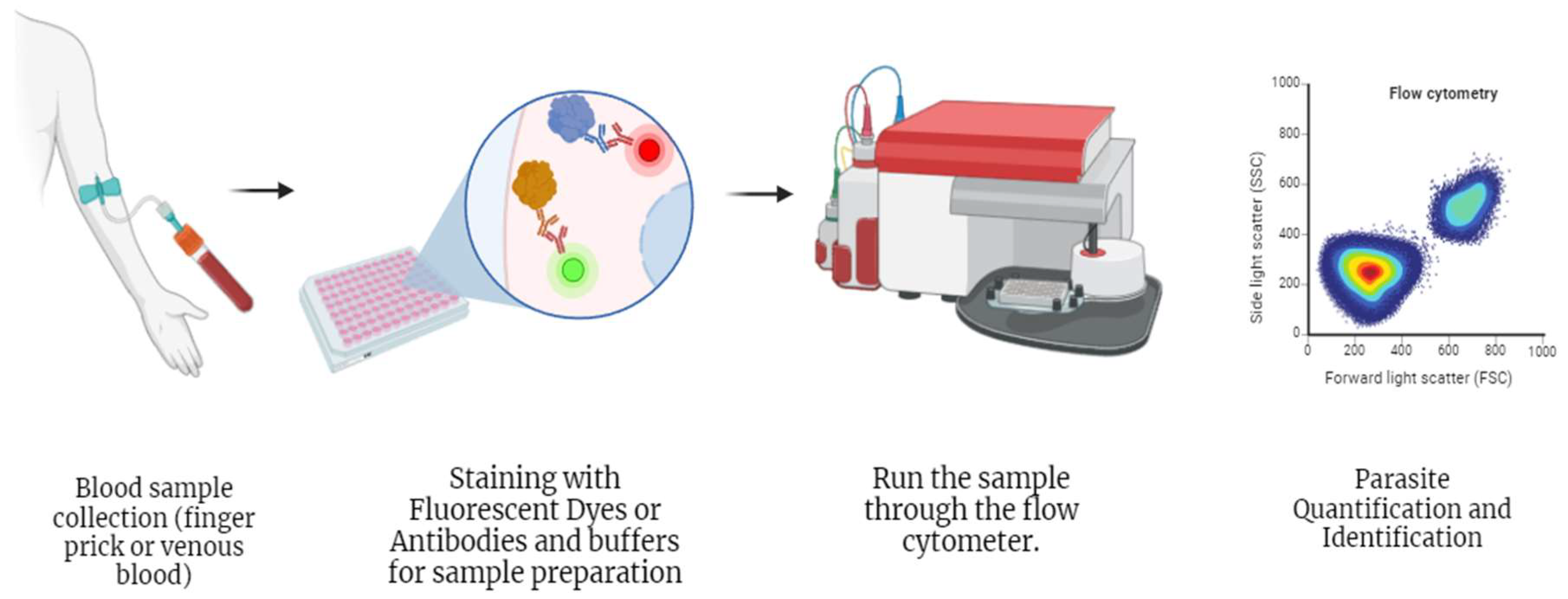

| Flow cytometry | (i) Quantification of infected erythrocytes [102,103,105,106,107,108] | (i) Low sensitivity than PCR [106] | 100 % [107] | 98.39% [107] |

| (ii) Automated parasite level calculations [105,106,107,108] | (ii) Difficult implementation in endemic areas [105,106,107,108] | |||

2.1.3. Serological Test

2.2. Advancements in Malaria Diagnosis

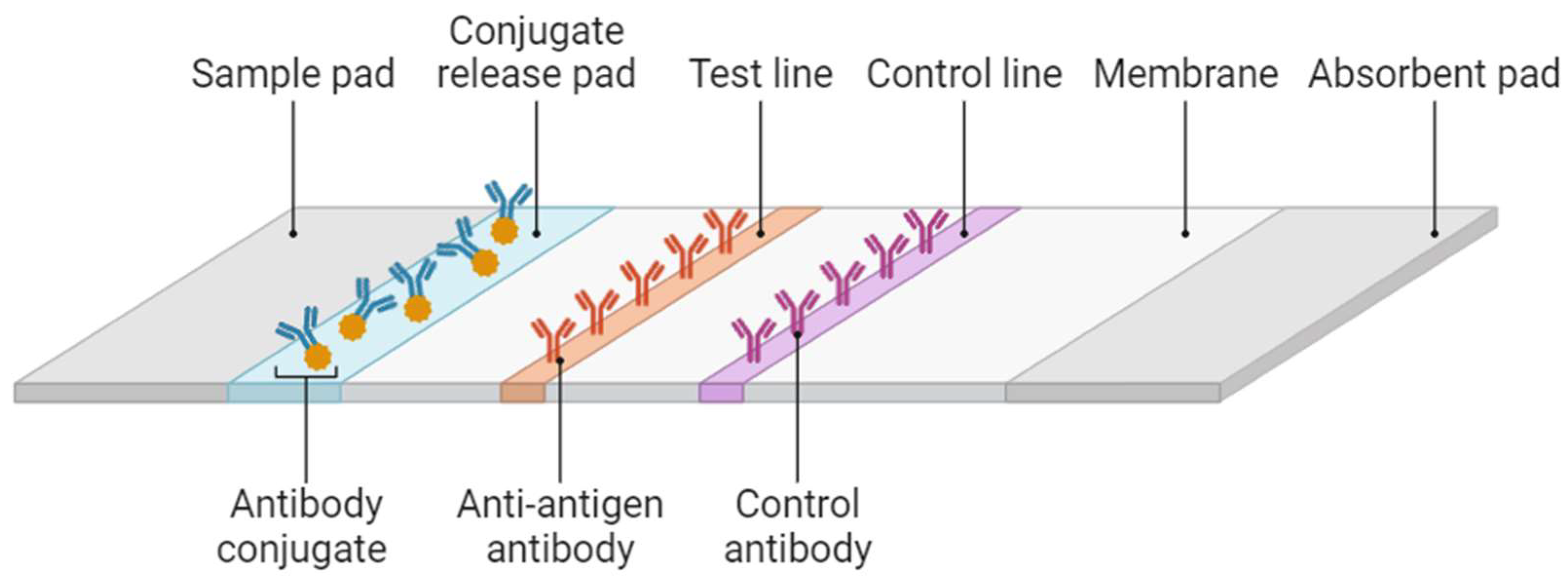

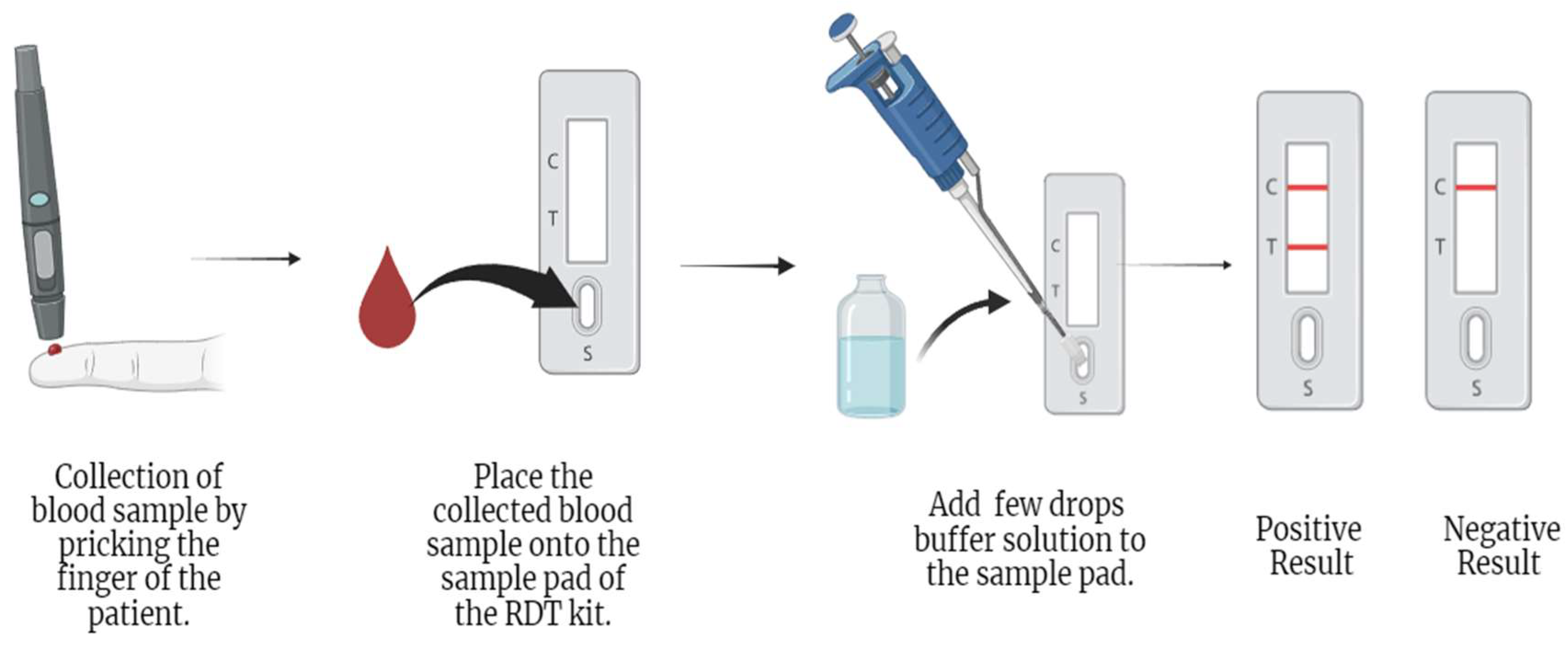

2.2.1. Rapid Diagnostic Test

2.2.2. Quantitative Buffy Coat (QBC) Test

2.3.3. Molecular Diagnosis of Malaria

2.3.3.1. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

2.3.3.2. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP)

2.3.3.3. Mass Spectrometry

2.3.3.4. Flow Cytometry

2.3. Artificial Intelligence and Image Analysis Techniques

2.3.1. Artificial Intelligence Based Object Detection System (AIDMAN)

2.3.2. Automated AI-Based Microscopy (Easy Go Scan)

2.3.3. Smartphone Based Application for Malaria Diagnosis (Malaria Screener & PVF-Net)

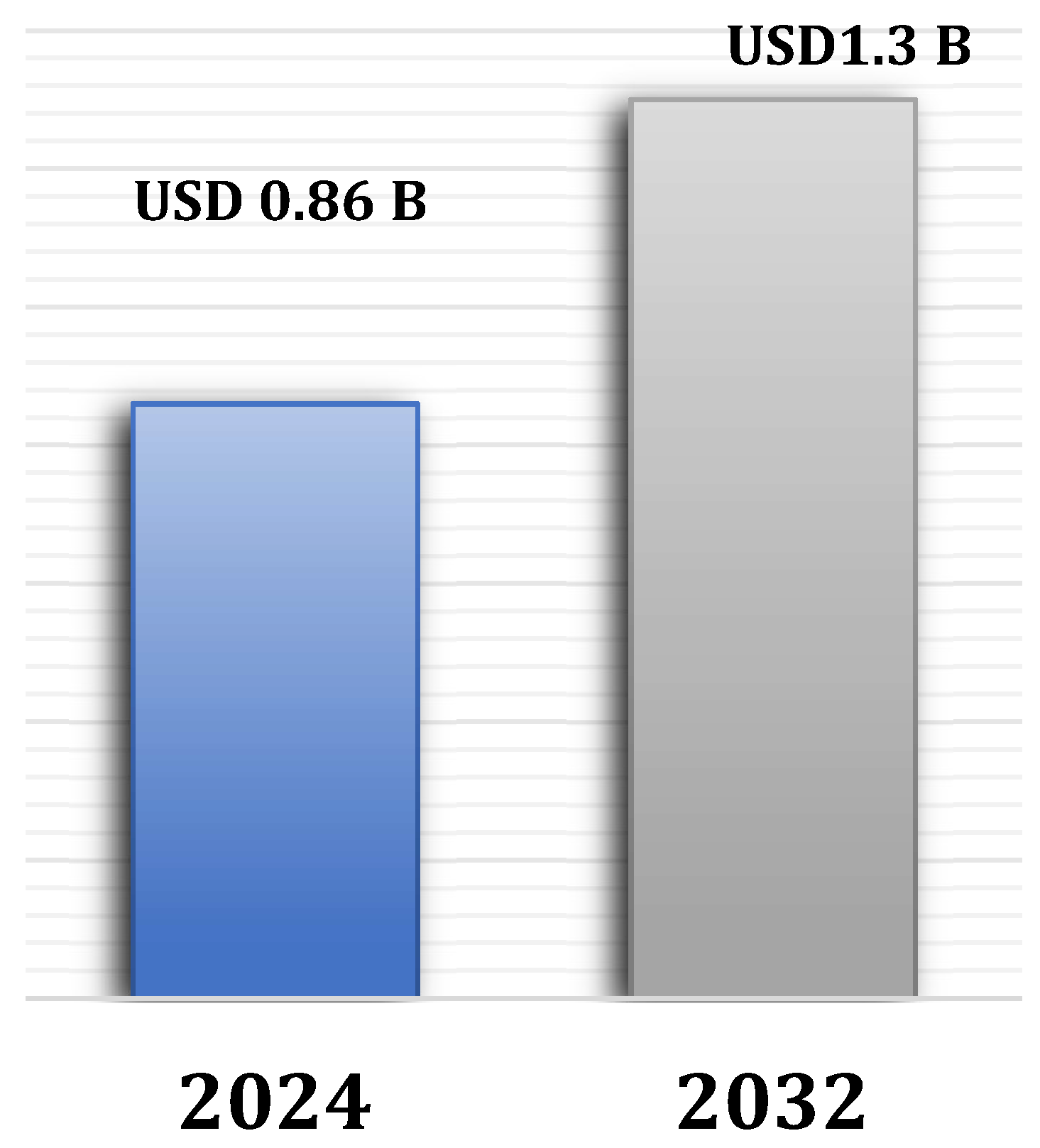

2.4. Malaria Diagnostic Market

2.4.1. Challenges and Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tangpukdee, N., Duangdee, C., Wilairatana, P., &Krudsood, S. (2009). Malaria Diagnosis: A Brief Review. The Korean Journal of Parasitology, 47(2), 93. [CrossRef]

- Kantele, A., &Jokiranta, T. S. (2011). Review of cases with the emerging fifth human malaria parasite, Plasmodium knowlesi. In Clinical Infectious Diseases (Vol. 52, Issue 11, pp. 1356–1362). [CrossRef]

- World malaria report 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023 (accessed on 05-09-2024). Available online:.

- Narain, J. P. , &Nath, L. M. (2018). Eliminating malaria in India by 2027: The countdown begins! In Indian Journal of Medical Research (Vol. 148, Issue 2, pp. 123–126). Indian Council of Medical Research. [CrossRef]

- Bell, D. , Wongsrichanalai, C., & Barnwell, J. W. (2006). Ensuring quality and access for malaria diagnosis: how can it be achieved? Nature Reviews Microbiology, 4(S9), S7–S20. [CrossRef]

- Bhandari PL, Raghuveer CV, Rajeev A, Bhandari PD. Comparative study of peripheral blood smear, quantitative buffy coat and modified centrifuged blood smear in malaria diagnosis. Indian J PatholMicrobiol. 2008;51(1):108-112. [CrossRef]

- Ngasala, B. , Mubi, M., Warsame, M., Petzold, M. G., Massele, A. Y., Gustafsson, L. L., Tomson, G., Premji, Z., &Bjorkman, A. (2008). Impact of training in clinical and microscopy diagnosis of childhood malaria on antimalarial drug prescription and health outcome at primary health care level in Tanzania: A randomized controlled trial. Malaria Journal, 7(1), 199. [CrossRef]

- Grimberg, B. T. (2011). Methodology and application of flow cytometry for investigation of human malaria parasites. Journal of Immunological Methods, 367(1–2), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. L. (2013). Laboratory Diagnosis of Malaria: Conventional and Rapid Diagnostic Methods. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 137(6), 805–811. [CrossRef]

- Fitri, L. E. , Widaningrum, T., Endharti, A. T., Prabowo, M. H., Winaris, N., &Nugraha, R. Y. B. (2022). Malaria diagnostic update: From conventional to advanced method. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis, 36(4). [CrossRef]

- Mouatcho, J. C. , & Dean Goldring, J. P. (2013). Malaria rapid diagnostic tests: Challenges and prospects. In Journal of Medical Microbiology (Vol. 62, Issue PART10, pp. 1491–1505). [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Mohammed FO, Abdel Hamid M, et al. Patient-level performance evaluation of a smartphone-based malaria diagnostic application. Malar J. 2023;22(1):33. Published 2023 Jan 27. [CrossRef]

- Ledermann D, W. (2008). [Laveran, Marchiafava and paludism]. RevistaChilena de Infectologia : OrganoOficial de La SociedadChilena de Infectologia, 25(3), 216–221.

- Baker, J. , Ho, M.-F., Pelecanos, A., Gatton, M., Chen, N., Abdullah, S., Albertini, A., Ariey, F., Barnwell, J., Bell, D., Cunningham, J., Djalle, D., Echeverry, D. F., Gamboa, D., Hii, J., Kyaw, M. P., Luchavez, J., Membi, C., Menard, D., … Cheng, Q. (2010). Global sequence variation in the histidine-rich proteins 2 and 3 of Plasmodium falciparum: implications for the performance of malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Malaria Journal, 9(1), 129. [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, D. , Ho, M.-F., Bendezu, J., Torres, K., Chiodini, P. L., Barnwell, J. W., Incardona, S., Perkins, M., Bell, D., McCarthy, J., & Cheng, Q. (2010). A Large Proportion of P. falciparum Isolates in the Amazon Region of Peru Lack pfhrp2 and pfhrp3: Implications for Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests. PLoS ONE, 5(1), e8091. [CrossRef]

- 16. Kumar, N., Pande, V., Bhatt, R. M., Shah, N. K., Mishra, N., Srivastava, B., Valecha, N., & Anvikar, A. R. (2013). Genetic deletion of HRP2 and HRP3 in Indian Plasmodium falciparum population and false negative malaria rapid diagnostic test. Acta Tropica, 125(1), 119–121. [CrossRef]

- Malaria Diagnostics Market Size. Available onine: https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/malaria-diagnostics-market/market-size (accessed on 07.10.2024). (accessed on 07.10.2024).

- Bartoloni, A., & Zammarchi, L. (2012). Clinical aspects of uncomplicated and severe malaria. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases, 4(1), e2012026. 4. [CrossRef]

- Warrell, D. A. (2017). Essential Malariology, 4Ed. CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Prah, J. K., Amoah, S., Yartey, A. N., Ampofo-Asiama, A., &Ameyaw, E. O. (2021). Assessment of malaria diagnostic methods and treatments at a Ghanaian health facility. The Pan African Medical Journal, 39, 251. [CrossRef]

- Cheesbrough, M. (2005). District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Azikiwe, C. C. A. , Ifezulike, C. C., Siminialayi, I. M., Amazu, L. U., Enye, J. C., &Nwakwunite, O. E. (2012). A comparative laboratory diagnosis of malaria: microscopy versus rapid diagnostic test kits. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 2(4), 307–310. [CrossRef]

- Bayisa, G., &Dufera, M. (2022). Malaria Infection, Parasitemia, and Hemoglobin Levels in Febrile Patients Attending Sibu Sire Health Facilities, Western Ethiopia. BioMed Research International, 2022, 1–8. 2022. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Malaria Microscopy Quality Assurance Manual—Ver. 2. WHO. WHO Press; 2016. 1-2 p.

- Diagnosing malaria. Available online: www.who.int/westernpacific/activities/diagnosing-malaria# (accessed on 10.10.2024). Available online:.

- Guintran, J.-O. , Delacollette, C., and Trigg, P. (2006). Systems for the Early Detection of Malaria Epidemics in Africa, 1–100 http://www.li.mahidol.ac.th/ thainatis/pdf-ebook/ebook77.pdf.

- Collins, W. E. , and Jeffery, G. M. (2007). Plasmodium malariae: parasite and disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 579–592. [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M. A. , and Shute, G. T. ( 1966). A comparative study of thick and thin blood films in the diagnosis of scanty malaria parasitaemia. Bull. World Health Organ. 34, 249–267. [PubMed]

- Wangai, L. N. , Karau, M. G., Njiruh, P. N., Sabah, O., Kimani, F. T., Magoma, G., et al. (2011). Sensitivity of microscopy compared to molecular diagnosis of P. falciparum: implications on malaria treatment in epidemic areas in Kenya. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 5, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Poostchi, M., Silamut, K., Maude, R. J., Jaeger, S., and Thoma, G. (2018). Image analysis and machine learning for detecting malaria. Transl. Res. 194, 36–55. [CrossRef]

- Evaluation and Diagnosis (2019). Shujatullah-Malaria-Diagnosis and Treatment (United States)– Diagnosis (U.S.). Centres for Diseases Control and Prevention CDC, CDC. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/hcp/clinical-guidance/evaluation-diagnosis.html.

- Maturana, C. R. , de Oliveira, A. D., Nadal, S., Bilalli, B., Serrat, F. Z., Soley, M. E., Igual, E. S., Bosch, M., Lluch, A. V., Abelló, A., López-Codina, D., Suñé, T. P., Clols, E. S., & Joseph-Munné, J. (2022). Advances and challenges in automated malaria diagnosis using digital microscopy imaging with artificial intelligence tools: A review. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Voller, a. , &Draper, C. C. (1982). Immunodiagnosis and sero-epidemiology of malaria. British Medical Bulletin, 38(2), 173–178. [CrossRef]

- Mungai, M. , Tegtmeier, G., Chamberland, M., &Parise, M. (2001). Transfusion-Transmitted Malaria in the United States from 1963 through 1999. New England Journal of Medicine, 344(26), 1973–1978. [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, A., Knipes, A., Worrell, C., Fox, L. A. M., Desir, L., Fayette, C., et al. (2020). Combination of serological, antigen detection, and DNA data for Plasmodium falciparum provides robust geospatial estimates for malaria transmission in Haiti. Sci. Rep. 10, 8443–8449. [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, N. W. , Demas, A., Narayanan, J., Sumari, D., Kabanywanyi, A., Kachur, S. P., Barnwell, J. W., &Udhayakumar, V. (2010). Real-Time Fluorescence Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification for the Diagnosis of Malaria. PLoS ONE, 5(10), e13733. [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, N. W. , Karell, M. A., Journel, I., Rogier, E., Goldman, I., Ljolje, D., Huber, C., Mace, K. E., Jean, S. E., Akom, E. E., Oscar, R., Buteau, J., Boncy, J., Barnwell, J. W., & Udhayakumar, V. (2014). PET-PCR method for the molecular detection of malaria parasites in a national malaria surveillance study in Haiti, 2011. Malaria Journal, 13(1), 462. [CrossRef]

- Putaporntip, C. , Buppan, P., &Jongwutiwes, S. (2011). Improved performance with saliva and urine as alternative DNA sources for malaria diagnosis by mitochondrial DNA-based PCR assays. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 17(10), 1484–1491. [CrossRef]

- Krampa, F. D., Aniweh, Y., Kanyong, P., &Awandare, G. A. (2020). Recent Advances in the Development of Biosensors for Malaria Diagnosis. Sensors, 20(3), 799. [CrossRef]

- Sarvamangala, D. R. , &Kulkarni, R. V. (2022). Convolutional neural networks in medical image understanding: a survey. Evolutionary Intelligence, 15(1), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Moody, A. (2002). Rapid Diagnostic Tests for Malaria Parasites. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 15(1), 66–78. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C. K., D. Bell, R. A. Gasser, and C. Wongsrichanalai. 2003. Rapid diagnostic testing for malaria. Trop. Med. Int. Health 8:876-883.

- Rock, E. P. , Marsh, K., Saul, A. J., Wellems, T. E., Taylor, D. W., Maloy, W. L., & Howard, R. J. (1987). Comparative analysis of the Plasmodium falciparumhistidine-rich proteins HRP-I, HRP-II and HRP-III in malaria parasites of diverse origin. Parasitology, 95(2), 209–227. [CrossRef]

- Bell D, Wongsrichanalai C, Barnwell JW. Ensuring quality and access for malaria diagnosis: how can it be achieved?. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(9):682-695. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C. K. , and Bennett, J. W. ( 2009). Rapid diagnosis of malaria. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2009, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. "Malaria rapid diagnostic test performance: results of WHO product testing of malaria RDTs: round 8 (2016–2018)." (2018).

- Michael L. Wilson, Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 54, Issue 11, 1 June 2012, Pages 1637–1641. [CrossRef]

- Barney R, Velasco M, Cooper CA, et al. Diagnostic Characteristics of Lactate Dehydrogenase on a Multiplex Assay for Malaria Detection Including the Zoonotic Parasite Plasmodium knowlesi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;106(1):275-282. Published 2021 Nov 15. [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, M. J. , Azzam, S. E., &Rockabrand, D. M. (2021). Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests: Literary Review and Recommendation for a Quality Assurance, Quality Control Algorithm. Diagnostics, 11(5), 768. [CrossRef]

- Kyabayinze, D. J. , Tibenderana, J. K., Odong, G. W., Rwakimari, J. B., &Counihan, H. (2008). Operational accuracy and comparative persistent antigenicity of HRP2 rapid diagnostic tests for Plasmodium falciparum malaria in a hyperendemic region of Uganda. Malaria Journal, 7(1), 221. [CrossRef]

- Berzosa, P. , de Lucio, A., Romay-Barja, M., Herrador, Z., González, V., García, L., Fernández-Martínez, A., Santana-Morales, M., Ncogo, P., Valladares, B., Riloha, M., & Benito, A. (2018). Comparison of three diagnostic methods (microscopy, RDT, and PCR) for the detection of malaria parasites in representative samples from Equatorial Guinea. Malaria Journal, 17(1), 333. [CrossRef]

- Ogunfowokan, O. , Ogunfowokan, B. A., &Nwajei, A. I. (2020). Sensitivity and specificity of malaria rapid diagnostic test (mRDTCareStatTM) compared with microscopy amongst under five children attending a primary care clinic in southern Nigeria. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Badiane, A. , Thwing, J., Williamson, J., Rogier, E., Diallo, M. A., &Ndiaye, D. (2022). Sensitivity and specificity for malaria classification of febrile persons by rapid diagnostic test, microscopy, parasite DNA, histidine-rich protein 2, and IgG: Dakar, Senegal 2015. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 121, 92–97. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J. , Jones, S., Gatton, M. L., Barnwell, J. W., Cheng, Q., Chiodini, P. L., Glenn, J., Incardona, S., Kosack, C., Luchavez, J., Menard, D., Nhem, S., Oyibo, W., Rees-Channer, R. R., Gonzalez, I., & Bell, D. (2019). A review of the WHO malaria rapid diagnostic test product testing programme (2008–2018): performance, procurement and policy. Malaria Journal, 18(1), 387. [CrossRef]

- DiMaio, M. A., Pereira, I. T., George, T. I., andBanaei, N. (2012). Performance of BinaxNOW for diagnosis of malaria in a U.S. hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 2877–2880. [CrossRef]

- Boyce, M. R. , and O’Meara, W. P. (2017). Use of malaria RDTs in various health contexts across sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 17, 470–415. [CrossRef]

- Ifeorah, I. K., Brown, B. J., and Sodeinde, O. O. (2017). A comparison of rapid diagnostic testing (by plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase), and quantitative buffy coat technique in malaria diagnosis in children. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 11, 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Feleke, D. G. , Alemu, Y., and Yemanebirhane, N. (2021). Performance of rapid diagnostic tests, microscopy, loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and PCR for malaria diagnosis in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar. J. 20, 384–311. [CrossRef]

- Wongsrichanalai, C. , Barcus, M., Muth, S., Sutamihardja, A., and Wernsdorfer, W. (2007). A review of malaria diagnostic tools: microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77, 119–127. [CrossRef]

- Gillet, P., Mori, M., Van Esbroeck, M., Van den Ende, J., and Jacobs, J. (2009). Assessment of the prozone effect in malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Malar. J. 8, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Bejon, P., Andrews, L., Hunt-Cooke, A., Sanderson, F., Gilbert, S. C., and Hill, A. V. S. (2006). Thick blood film examination for plasmodium falciparum malaria has reduced sensitivity and underestimates parasite density. Malar. J. 5, 5–8. [CrossRef]

- Nima, M. K. , Hougard, T., Hossain, M., Kibria, M., Mohon, A., Johora, F., et al. (2017). Case report: a case of plasmodium falciparum hrp2 and hrp3 gene mutation in Bangladesh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97, 1155–1158. [CrossRef]

- Orish, V. N., De-Gaulle, V. F., and Sanyaolu, A. O. (2018). Interpreting rapid diagnostic test (RDT) for Plasmodium falciparum. BMC. Res. Notes 11, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Response plan to pfhrp2 gene deletions. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-CDS-GMP-2019.02 (accessed on 12.10.2024).

- Ahmed, N. H. (2014). Quantitative Buffy Coat Analysis-An Effective Tool For Diagnosing Blood Parasites. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH. [CrossRef]

- Kochareka, M., Sarkar, S., Dasgupta, D., &Aigal, U. (2012). A preliminary comparative report of quantitative buffy coat and modified quantitative buffy coat with peripheral blood smear in malaria diagnosis. Pathogens and Global Health, 106(6), 335–339. [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, G. O. , &Nga, I. C. (2007). Comparison of Quantitative Buffy Coat technique (QBC) with Giemsa-stained thick film (GTF) for diagnosis of malaria. Parasitology International, 56(4), 308–312. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M. J., Rodrigues, S. R., Desouza, R., &Verenkar, M. P. (2001). Usefulness of quantitative buffy coat blood parasite detection system in diagnosis of malaria. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, 19(4), 219–221.

- Gay, F., Traoré, B., Zanoni, J., Danis, M., &Gentilini, M. (1994). Evaluation of the QBC system for the diagnosis of malaria. Sante (Montrouge, France), 4(4), 289–297.

- Vaidya, K. A. , &Sukesh. (2012). Quantitative buffy coat (QBC) test and other diagnostic techniques for diagnosing malaria: review of literature. National Journal of Medical Research, 2(03), 386–388.

- Shujatullah, F., Malik, A., Khan, H. M., and Malik, A. (2006). Comparison of different diagnostic techniques in plasmodium falciparum cerebral malaria. J. Vector Borne Dis. 43, 186–190. [PubMed]

- Bhandari, P. L., Raghuveer, C. V., Rajeev, A., &Bhandari, P. D. (2008). Comparative study of peripheral blood smear, quantitative buffy coat and modified centrifuged blood smear in malaria diagnosis. Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology, 51(1), 108-112.

- Snounou, G. , Viriyakosol, S., Xin Ping Zhu, Jarra, W., Pinheiro, L., do Rosario, V. E., Thaithong, S., & Brown, K. N. (1993). High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 61(2), 315–320. [CrossRef]

- Lazrek, Y., Florimond, C., Volney, B., Discours, M., Mosnier, E., Houzé, S., Pelleau, S., & Musset, L. (2023). Molecular detection of human Plasmodium species using a multiplex real time PCR. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 11388. [CrossRef]

- Menard, D. , Popovici, J., Meek, S., Socheat, D., Rogers, W. O., Taylor, W. R. J., Lek, D., Vinjamuri, S. B., Ariey, F., & Bruce, J. (2016). National Malaria Prevalence in Cambodia: Microscopy Versus Polymerase Chain Reaction Estimates. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 95(3), 588–594. [CrossRef]

- Tedla, M. (2019). A focus on improving molecular diagnostic approaches to malaria control and elimination in low transmission settings: Review. Parasite Epidemiology and Control, 6, e00107. [CrossRef]

- Magnaval, J. F. , Morassin, B., Berry, A., & Fabre, R. (2002). One year’s experience with the polymerase chain reaction as a routine method for the diagnosis of imported malaria. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 66(5), 503–508. [CrossRef]

- Anthony C, Mahmud R, Lau YL, Syedomar SF, Sri La Sri Ponnampalavanar S. Comparison of two nested PCR methods for the detection of human malaria. Trop Biomed. 2013;30(3):459-466.

- Looareesuwan S, Krudsood S, Sloan L, et al. Evaluation of a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for the diagnosis of malaria in patients from Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(5):850-854.

- Mangold KA, Manson RU, Koay ESC, et al. Real-time PCR for detection and identification of Plasmodium spp. J ClinMicrobiol. 2005;43(5):2435-2440.

- Tajebe A, Magoma G, Aemero M, Kimani F. Detection of mixed infection level of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax by SYBR Green I-based real-time PCR in North Gondar, north-west Ethiopia. Malar J. 2014;13(1):411. [CrossRef]

- Chua KH, Lim SC, Ng CC, et al. Development of high resolution melting analysis for the diagnosis of human malaria. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15671.

- Awosolu, O. B. , Yahaya, Z. S., Farah Haziqah, M. T., &Olusi, T. A. (2022). Performance Evaluation of Nested Polymerase Chain Reaction (Nested PCR), Light Microscopy, and Plasmodium falciparum Histidine-Rich Protein 2 Rapid Diagnostic Test (PfHRP2 RDT) in the Detection of Falciparum Malaria in a High-Transmission Setting in Southwestern Nigeria. Pathogens, 11(11), 1312.

- Johnston, S. P., Pieniazek, N. J., Xayavong, M. V., Slemenda, S. B., Wilkins, P. P., and da Silva, A. J. (2006). PCR as a confirmatory technique for laboratory diagnosis of malaria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 1087–1089. [CrossRef]

- Siwal, N., Singh, U. S., Dash, M., Kar, S., Rani, S., Rawal, C., et al. (2018). Malaria diagnosis by PCR revealed differential distribution of mono and mixed species infections by plasmodium falciparum and p. vivax in India. PLoS One 13, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Haanshuus, C. G. , Mørch, K., Blomberg, B., Strøm, G. E. A., Langeland, N., Hanevik, K., et al. (2019). Assessment of malaria real-time PCR methods and application with focus on lowlevelparasitaemia. PLoS One 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Eshag, H. A. , Elnzer, E., Nahied, E., Talib, M., Mussa, A., Muhajir, A. E. M. A., et al. (2020). Molecular epidemiology of malaria parasite amongst patients in a displaced people’s camp in Sudan. Trop. Med. Health 48, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Leski, T. A. , Taitt, C. R., Swaray, A. G., Bangura, U., Reynolds, N. D., Holtz, A., et al. (2020). Use of real-time multiplex PCR, malaria rapid diagnostic test and microscopy to investigate the prevalence of plasmodium species among febrile hospital patients in Sierra Leone. Malar. J. 19, 84–88. [CrossRef]

- Feufack-Donfack, L. B. , Sarah-Matio, E. M., Abate, L. M., BouopdaTuedom, A. G., NganoBayibéki, A., MaffoNgou, C., et al. (2021). Epidemiological and entomological studies of malaria transmission in Tibati, Adamawa region of Cameroon 6 years following the introduction of long-lasting insecticide nets. Parasit. Vectors 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Mwenda, M. C. , Fola, A. A., Ciubotariu, I. I., Mulube, C., Mambwe, B., Kasaro, R., et al. (2021). Performance evaluation of RDT, light microscopy, and PET-PCR for detecting plasmodium falciparum malaria infections in the 2018 Zambia National Malaria Indicator Survey. Malar. J. 20, 386–310. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A., Soni, P., Kumar, L., Singh, M. P., Verma, A. K., Sharma, A., Das, A., & Bharti, P. K. (2021). Comparison of polymerase chain reaction, microscopy, and rapid diagnostic test in malaria detection in a high burden state (Odisha) of India. Pathogens and Global Health, 115(4), 267–272. [CrossRef]

- Poon, L. L. , Wong, B. W., Ma, E. H., Chan, K. H., Chow, L. M., Abeyewickreme, W., Tangpukdee, N., Yuen, K. Y., Guan, Y., Looareesuwan, S., &Peiris, J. M. (2006). Sensitive and Inexpensive Molecular Test for Falciparum Malaria: Detecting Plasmodium falciparum DNA Directly from Heat-Treated Blood by Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification,.Clinical Chemistry, 52(2), 303–306. [CrossRef]

- Clinical Guidance: Malaria Diagnosis & Treatment in the U.S. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/clinicians1.html (accesed on 01.09.2024).

- Puri, M. , Kaur Brar, H., Madan, E., Srinivasan, R., Rawat, K., Gorthi, S. S., et al. (2022). Rapid diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum malaria using a point of- care loop-mediated isothermal amplification device. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12:961832. [CrossRef]

- Morris, U. , and Aydin-Schmidt, B. (2021). Performance and application of commercially available loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) kits in malaria endemic and non-endemic settings. Diagnostics 11, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Ocker, R. , Prompunjai, Y., Chutipongvivate, S., and Karanis, P. (2016). Malaria diagnosis by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) in Thailand. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 58, 2–7. [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, D. , Naing, C., Htet, N. H., and Mak, J. W. (2020). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) test for diagnosis of uncomplicated malaria in endemic areas: a meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. Malar. J. 19, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Antinori, S. , Ridolfo, A. L., Grande, R., Galimberti, L., Casalini, G., Giacomelli, A., &Milazzo, L. (2021). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay for the diagnosis of imported malaria: a narrative review. Le Infezioni in Medicina, 29(3), 355–365. [CrossRef]

- Demirev, P. A. (2004). Mass spectrometry for malaria diagnosis. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics, 4(6), 821–829. [CrossRef]

- Scholl, P. F. , Kongkasuriyachai, D., Demirev, P. A., Feldman, A. B., Lin, J. S., Sullivan, D. J., & Kumar, N. (2004). Rapid detection of malaria infection in vivo by laser desorption mass spectrometry. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 71(5), 546–551.

- Nyunt, M. , Pisciotta, J., Feldman, A. B., Thuma, P., Scholl, P. F., Demirev, P. A.,...& Sullivan Jr, D. J. (2005). Detection of Plasmodium falciparum in pregnancy by laser desorption mass spectrometry. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(3):485-490.

- Christner M, Frickmann H, Klupp E, Rohde H, Kono M, Tannich E, et al. Insufficient sensitivity of laser desorption-time of flight mass spectrometry-based detection of hemozoin for malaria screening. J Microbiol Methods. 2019;160:104–6.

- Stauning, M.A. , Jensen, C.S., Staalsøe, T. et al. Detection and quantification of Plasmodium falciparum in human blood by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry: a proof of concept study. Malar J 22, 285, 2023.

- Robinson, J. P. (2022). Flow Cytometry: Past and Future. BioTechniques, 72(4), 159–169. [CrossRef]

- vanVianen, P. H. , van Engen, A., Thaithong, S., van der Keur, M., Tanke, H. J., van der Kaay, H. J., Mons, B., &Janse, C. J. (1993). Flow cytometric screening of blood samples for malaria parasites. Cytometry, 14(3), 276–280. [CrossRef]

- Malleret, B. , Claser, C., Ong, A. S. M., Suwanarusk, R., Sriprawat, K., Howland, S. W., Russell, B., Nosten, F., &Rénia, L. (2011). A rapid and robust tri-color flow cytometry assay for monitoring malaria parasite development. Scientific Reports, 1(1), 118. [CrossRef]

- Stéphane Picot, Thomas Perpoint, Christian Chidiac, Alain Sigal, Etienne Javouhey, Yves Gillet, Laurent Jacquin, Marion Douplat, Karim Tazarourte, Laurent Argaud, Martine Wallon, CharlineMiossec, Guillaume Bonnot and Anne-LiseBienvenu. Diagnostic accuracy of fluorescence flow-cytometry technology using Sysmex XN-31 for imported malaria in a non-endemic setting, Parasite, 29, 2022, 31.

- Khartabil, T. A. , de Rijke, Y. B., Koelewijn, R., van Hellemond, J. J., andRusscher, H. (2022). Fast detection and quantification of plasmodium species infected erythrocytes in a non-endemic region by using the Sysmex XN-31 analyzer. Malar. J. 21, 119–110. [CrossRef]

- Manescu, P. , Shaw, M. J., Elmi, M., Neary-Zajiczek, L., Claveau, R., Pawar, V., Kokkinos, I., Oyinloye, G., Bendkowski, C., Oladejo, O. A., Oladejo, B. F., Clark, T., Timm, D., Shawe-Taylor, J., Srinivasan, M. A., Lagunju, I., Sodeinde, O., Brown, B. J., & Fernandez-Reyes, D. (2020). Expert-level automated malaria diagnosis on routine blood films with deep neural networks. American Journal of Hematology, 95(8), 883–891. [CrossRef]

- Okello PE, Van Bortel W, Byaruhanga AM, Correwyn A, Roelants P, Talisuna A, D'Alessandro U, Coosemans M: Variation in malaria transmission intensity in seven sites throughout Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006, 75: 219-225.

- Wanji S, Kimbi HK, Eyong JE, Tendongfor N, Ndamukong JL. Performance and usefulness of the Hexagon rapid diagnostic test in children with asymptomatic malaria living in the Mount Cameroon region. Malar J. 2008;7. [CrossRef]

- Nkrumah B, Acquah SE, Ibrahim L, May J, Brattig N, Tannich E, et al. Comparative evaluation of two rapid field tests for malaria diagnosis: Partec Rapid Malaria Test® and Binax Now® Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11. [CrossRef]

- Hassan SE, Okoued SI, Mudathir MA, Malik EM: Testing the sensitivity and specificity of the fluorescence microscope (Cyscope(R)) for malaria diagnosis. Malar J. 2010, 9: 88. [CrossRef]

- Kimbi HK, Ajeagah HU, Keka FC, Lum E, Nyabeyeu HN, Tonga CF, et al. Asymptomatic malaria in school children and evaluation of the performance characteristics of the PartecCyscope® in the Mount Cameroon Region. J BacteriolParasitol. 2012;3:5.

- Ndamukong-Nyanga J, Kimbi H, Sumbele I, Bertek S, Lafortune K, Larissa K, et al. Comparison of the PartecCyScope® rapid diagnostic test with light microscopy for malaria diagnosis in Rural Tole, Southwest Cameroon. British J Med Med Res. 2015;8:623–633. [CrossRef]

- Birhanie, M. Comparison of Partec rapid malaria test with conventional light microscopy for diagnosis of malaria in Northwest Ethiopia. J Parasitol Res. 2016;1:5. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. , Liu, T., Dan, T., Yang, S., Li, Y., Luo, B., Zhuang, Y., Fan, X., Zhang, X., Cai, H., &Teng, Y. (2023). AIDMAN: An AI-based object detection system for malaria diagnosis from smartphone thin-blood-smear images. Patterns, 4(9), 100806. [CrossRef]

- Pirnstill, C.W. , Coté G.L. Malaria diagnosis using a mobile phone polarized microscope. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. , Poostchi M., Yu H., Zhou Z., Silamut K., Yu J., Maude R.J., Jaeger S., Antani S. Deep learning for smartphone-based malaria parasite detection in thick blood smears. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020;24:1427–1438. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. , Yang F., Rajaraman S., Ersoy I., Moallem G., Poostchi M., Palaniappan K., Antani S., Maude R.J., Jaeger S. Malaria Screener: a smartphone application for automated malaria screening. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20:825. [CrossRef]

- Rees-Channer, R. R., Bachman, C. M., Grignard, L., Gatton, M. L., Burkot, S., Horning, M. P., Delahunt, C. B., Hu, L., Mehanian, C., Thompson, C. M., Woods, K., Lansdell, P., Shah, S., &Chiodini, P. L. (2023). Evaluation of an automated microscope using machine learning for the detection of malaria in travelers returned to the UK. Frontiers in Malaria, 1. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. , Mohammed, F. O., Abdel Hamid, M., Yang, F., Kassim, Y. M., Mohamed, A. O., Maude, R. J., Ding, X. C., Owusu, E. D. A., Yerlikaya, S., Dittrich, S., & Jaeger, S. (2023). Patient-level performance evaluation of a smartphone-based malaria diagnostic application. Malaria Journal, 22(1), 33. [CrossRef]

- Kassim, Y. M., Yang, F., Yu, H., Maude, R. J., & Jaeger, S. (2021). Diagnosing Malaria Patients with Plasmodium falciparum and vivax Using Deep Learning for Thick Smear Images. Diagnostics, 11(11), 1994. [CrossRef]

- LIST OF RAPID DIAGNOSTIC TEST (RDT) KITS FOR MALARIA classified according to the Global Fund Quality Assurance Policy. Available online: https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/5891/psm_qadiagnosticsmalaria_list_en.pdf (accessed on 15.10.2024).

- Malaria Diagnostics Market Insights. Available online: https://www.skyquestt.com/report/malaria-diagnostics-market (accessed on 14.10.2024).

- Kalia, I. , Anand, R., Quadiri, A., Bhattacharya, S., Sahoo, B., & Singh, A.P. (2021). Plasmodium berghei-Released Factor, PbTIP, Modulates the Host Innate Immune Responses. Front. Immunol. 12:699887. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).