1. Introduction

To evolve, one cannot hide from the reflection in the mirror. Computer Science (CS) as a field of study is routinely reflected upon and evolved to keep up with the everchanging image of technology. But now the people behind the technology are the ones finding themselves prepped for a makeover. Before generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools became widely available, computer programs were built from an empty source code file and an inspiration to solve problems. The origin stories of programmers all align on this point: whether you created the project yourself or inherited it from someone else, programs were built from scratch. Over time, coding editors have begun supplying some default,

boiler plate code to assist with writing a software solution, but the core development has always been born from the minds of humans. This fundamental perception of software development is starting to blur as GenAI tools assist with code completion and autonomous AI tools write software without any human intervention needed [

1]. A shift is coming where programmers, once seen as those who

create code, become those who

review generated code.

In CS education, faculty have historically built curriculum upon this same assumption that programs should be constructed from a blank canvas. Students have been required to learn, memorize, and practice syntax nuances, with the activities rarely including starter code. The premise for this assessment strategy is a combination of

we’ve always done it this way coupled with a belief that students will not be employable if they cannot code from scratch. Modern hiring techniques for software developers, although historically dreaded by prospective job candidates, underscore this point by often including a whiteboard coding interview, where the candidate must prove competency by writing code by hand with a dry erase marker [

2].

This approach to teaching CS may have continued merrily in the same direction if GenAI hadn’t come along and started helping students do their coding assignments for them. The question begs, if GenAI is writing code for the students, are we even assessing student knowledge of syntax anymore? For instructors to cling onto control in this situation by forbidding GenAI use, however futile that may be, involves a lot of overhead to ensure that students have obtained the competencies that instructors have sought to instill. In-person interviews, oral presentations, and hand-written exams become the default again, creating a classroom environment of tension and incompetent until proven competent, which often feels like guilty until proven innocent. But what would happen if, as faculty, we use all that energy poised at resistance of GenAI to instead change our definition of what we’re assessing, all while simultaneously empowering our students with the tools they are desiring to utilize?

In the spirit of ‘work smarter, not harder’, this research posits that students may be able to get to the same desired destination of understanding through coding, albeit faster and more engaged, in cooperation with GenAI. This educational path could potentially speed up learning with exposure to coding solutions in real-time, where students can ask questions for additional clarity as though they are working with a personal tutor. Liken it to learning a new language immersed in a culture where all are willing to help and patiently guide you, versus walking aimlessly in a new country just trying to glean syntax from what you’ve been able to store in your head. Both paths could get you to understand the new language, but the latter is more likely to encourage you to pack up your belongings and give up.

This study aims to answer the following research questions:

What benefits can be found when students work collaboratively with generative AI code assistance tools to complete assignments?

What strategies can Computer Science educators employ to empower students to use generative AI for learning?

2. Related Work

The widespread public accessibility of GenAI tools has forced educators to rethink how they run their classes. It has been two years since ChatGPT launched and the strategies to adopt it and others like it as learning tools instead of categorizing their assistance as plagiarism is still under construction. Proposals for how GenAI can integrate in the classroom include tailored educational content for each individual student, real-time feedback for students, research assistance, and generated teaching materials for educators [

3]. Students allowed to use GenAI for assigned work report the usefulness of the tools, especially with completing routine and tedious tasks [

4]. The potential for benefits of GenAI in academics is still being realized.

During the Spring of 2024, an empirical study was conducted by the author to assess the capabilities of GitHub Copilot against a second semester college programming course and its six required projects. The course, held at Waukesha County Technical College, introduces students to advanced programming topics including Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) design, composition, file input/output, exception handling, dependency management, functional programming, and more. The experiment conducted was overwhelmingly successful, showcasing that GitHub Copilot generated code could complete all six assignments with 100% requirements met and in under three hours total [

5]. Some of these projects used to take students up to three weeks to complete, in contrast to the mere minutes needed when using GitHub Copilot. This efficiency is seen in industry as well, with a recent study announcing a 26% increase in completed tasks when GenAI is used to write software [

6]. Without GenAI, project completion times for developers and CS students vary widely. But when some students use GenAI and some don’t, this range of time becomes a gulf of inequity.

The equity gap for CS students has seemingly always existed when it comes to the time required to complete a coding assignment. In her years as an undergrad and within a near decade of experience as an educator, the author has witnessed a perception and consensus amongst students and faculty alike that some people just aren’t meant to write code. One student may need an hour to complete a coding assignment, while another student in the same class will need the whole week. This disparity between students won’t necessarily dictate whether a student can be successful in a course or within the profession itself, but it does mean that what seems easy for some requires vastly more effort from others, and that struggle can lead to withdrawal.

Attrition rates in CS college degree programs have historically ranked the highest against other degree programs, with dropout rates averaging up to 40% in the last decade [

7,

8]. Acceptance of these attrition rates, and the equity gap for CS students, should no longer be status quo, as GenAI coding assistance tools can swiftly bring each student to a rough draft of their coding projects and offer explanations along the way to improve learning and engagement. The hope is for student confidence to soar as they quickly meet project requirements and see how achievable it can be. But we shouldn’t stop there. With all the evidence presented, the author considered what else students could discover if they suddenly had more time to reflect on the project they had built before moving onto the next one.

GenAI creates an opportunity for improved efficiency, as discovered through the GitHub Copilot study and also imagined by other instructors considering implementing GenAI into their courses [

9]. If students, empowered with GenAI, could complete their projects in a fraction of the time, what additional knowledge could be built here? The results of this research painted a future vastly different for students than originally perceived, where they would get to explore beyond simply meeting requirements and continue on to feats of creativity and innovation. And so, during the Summer of 2024, the programming course from the GitHub Copilot study was modified to formally include the use of GenAI for the upcoming academic year.

3. Methodology

3.1. GitHub Copilot Course Pilot

During the Fall of 2024, a pilot was conducted where students used GitHub Copilot to assist in completing assigned work for the aforementioned programming course. At the start of the eight week term, twenty-four students were tasked with enrolling for free GitHub Education licenses to gain access to GitHub Copilot. Students could opt to use a different GenAI tool, but were highly encouraged to use GitHub Copilot or another embedded IDE GenAI coding assistance tool as it will have more context about their projects than the browser-based alternatives. GitHub Copilot, installed as a plugin for JetBrains IntelliJ IDEA, was introduced to students on the first day of class. Students were shown how to properly install, configure, and prompt in order to work collaboratively with the GenAI as a learning tool. The suggested approach by the author and instructor of the course is for students to use the chat feature of GitHub Copilot exclusively, and that a markdown document of the assigned project’s requirements be referenced when chatting so that context is provided for the scope of the project.

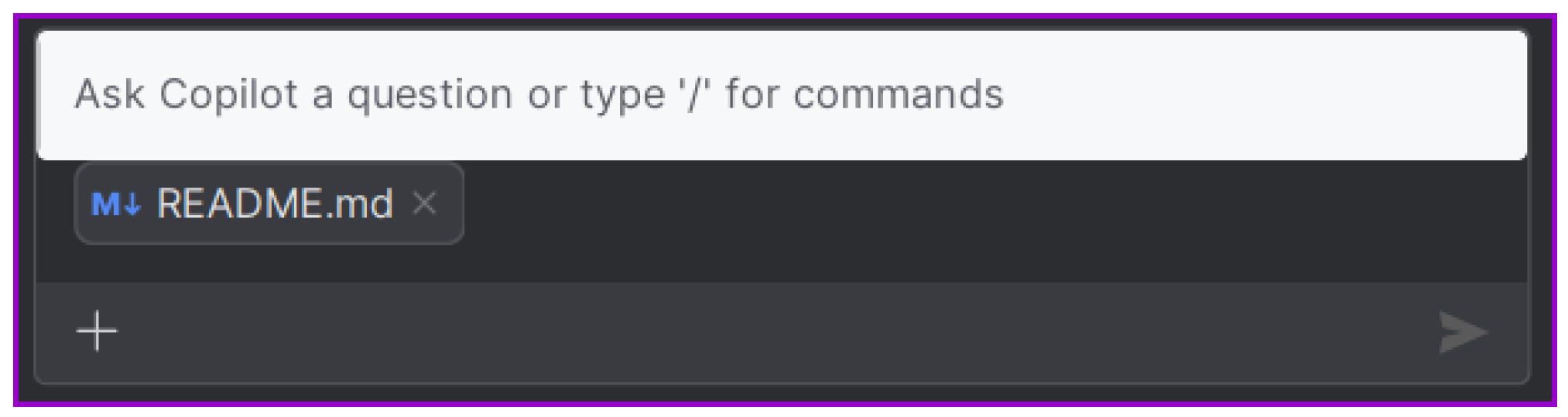

Figure 1.

Including a README.md reference for GitHub Copilot chat.

Figure 1.

Including a README.md reference for GitHub Copilot chat.

The assigned coding projects, which were historically limited to one phase: meet the requirements without compilation errors, were increased into three phases categorized as: experiment, exploration, and expertise. The experiment phase is the original project requirements, but to be completed with the assistance of GenAI. This allows students to observe how an application can be built and glean syntax and semantics along the way. The exploration phase includes a discussion about what additional features or enhancements could be made to the project and some initial modifications are attempted in code. Students are encouraged to prompt the GenAI tool for suggestions on how to improve their projects and discuss these amongst each other with their plans for what to implement next. The expertise phase is a best and final version of the project, where the student showcases the enhancements made beyond the original requirements. Students commit and push their projects to a GitHub Classroom private repository with a minimum of three commits, one for each phase, so that the project can be assessed over the three versions.

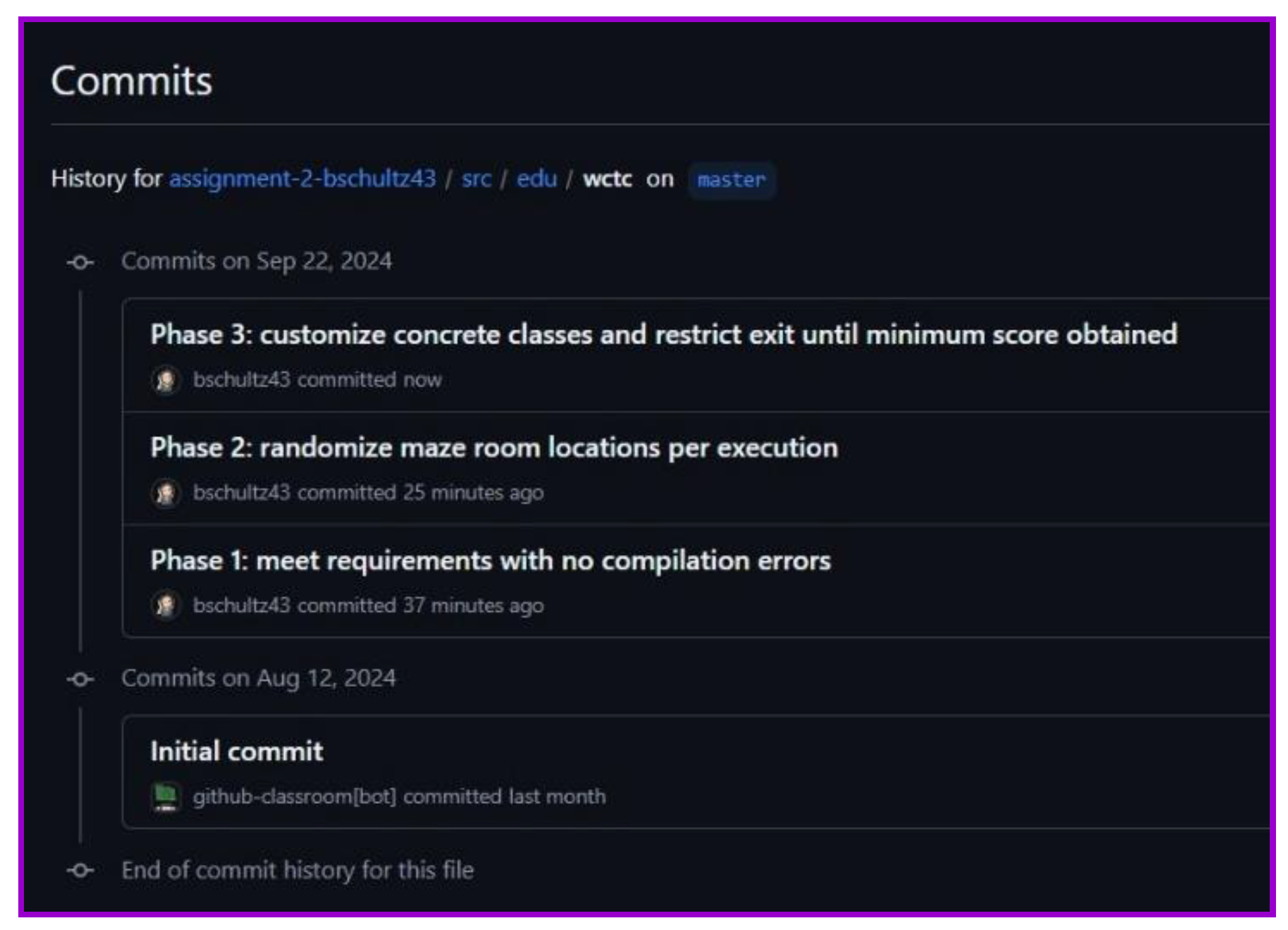

Figure 2.

A GitHub commit history example for the three project phases.

Figure 2.

A GitHub commit history example for the three project phases.

The idea behind this style of assessment is to not restrict the definition of a successful project to one that solely meets syntax and design requirements. This shift in strategy gives students the time to process what they’ve built, decide how it could be improved upon, and make personalized decisions to build something better than what they were originally asked for. The hope is that this creative space will allow the students to explore the different aspects of writing programs and find ones that interest them, such as program efficiency, user experience, security, quality assurance testing, etc.

AI generated solutions can be incorrect, as was found in the first study completed by the author. This creates an opportunity for students to see the complexities of writing code, how simple choices can cause errors, and, in cooperation with the GenAI tool, how to fix these issues when they occur. Furthermore, a slightly skeptical view of generated code may allow students to strengthen their troubleshooting and debugging skills and not become too reliant on GenAI. A well balanced collaboration of technology and critical thinking skills has always been the bedrock of software development and will continue to support the integration of AI generated code.

3.2. Survey student perception of modified course

In addition to the pilot, the students of this course were asked to complete a questionnaire about their experience using GenAI collaboratively to complete the assessments of this course. Although the discussion posts made by students during the exploration phase of each project give insight into the perceptions of this experience, a formal survey can allow for additional aggregate findings to be known. The survey consists of eight multiple choice questions and one open text field for additional comments. No personally identifying information was captured or stored as the true motive for the questionnaire was to obtain summarizing data.

4. Results

4.1. Pilot Shows Great Potential

Of the twenty-four enrolled students, eighteen students actively participated in and completed the course with a C or better. Four students dropped the course within the first two weeks, and two students remained in the course as non-participatory (turned in 20% or less of the required work). The students who actively participated and posted to discussions about their interactions writing code with GenAI assistance were generally positive, often mentioning how impressed they were with the speed in which their code met initial requirements. The allowance for creative expression through assignments also inspired enthusiasm for the project work. Some positive comments include:

The experiment phase was blazing fast. I was genuinely surprised how good Copilot is.

The most valuable feature is the ability to quickly get the ‘skeleton’ of the program done which frees you up to become creative with what additional enhancements you want to make, improving quality and efficiency.

I really enjoy using Copilot because it is able to help write code as well as come up with ideas to improve your code. It ensures that I never get stuck on anything and have a resource to help me with my code.

Some of the discussion posts expressed feelings of frustration or hesitation to adopt GenAI as a learning tool. Some of these comments include:

I am not sure about using Copilot. It feels too easy? I’m worried I’m too reliant on the tool.

[My program] was successfully AI generated, and I’m scared to get rid of things because I don’t want to break it.

I didn’t experiment much with GitHub Copilot! This was a simple enough assignment that I wanted to get used to programming in Java.

The views shared by students echo the concerns and hopes of the author, which continues to impact the overall direction of this course as incorporation of GenAI continues or is otherwise deemed unsuitable.

From an instructor perspective, the grading process was very inspiring as projects were submitted with working code and included additional features that the students felt were worthwhile to incorporate outside the minimum requirements. Traditionally, it has often been challenging to grade projects when turned in partially complete or with too many syntax errors to piece together a cohesive grade. With the assistance of GenAI, all projects submitted during this pilot could be executed successfully which is unprecedented and exciting.

An additional observation worth noting is how few student emails and requests for office hours came through from the students of this course. Any emails received were with regard to configuration or licensing of GitHub Copilot or missing class. There were no emails sent regarding a need for help with code or request for office hours. This is also a rare occurrence and one that could be related to how GenAI can answer a lot of the common questions typically queried to CS instructors. The resulting autonomy instilled in students when they hunt down answers themselves is a very desirable and sought-after characteristic of Information Technology professionals. This training early on bodes well for future employment of CS students in a GenAI era.

4.2. Survey Captures Student Enthusiasm

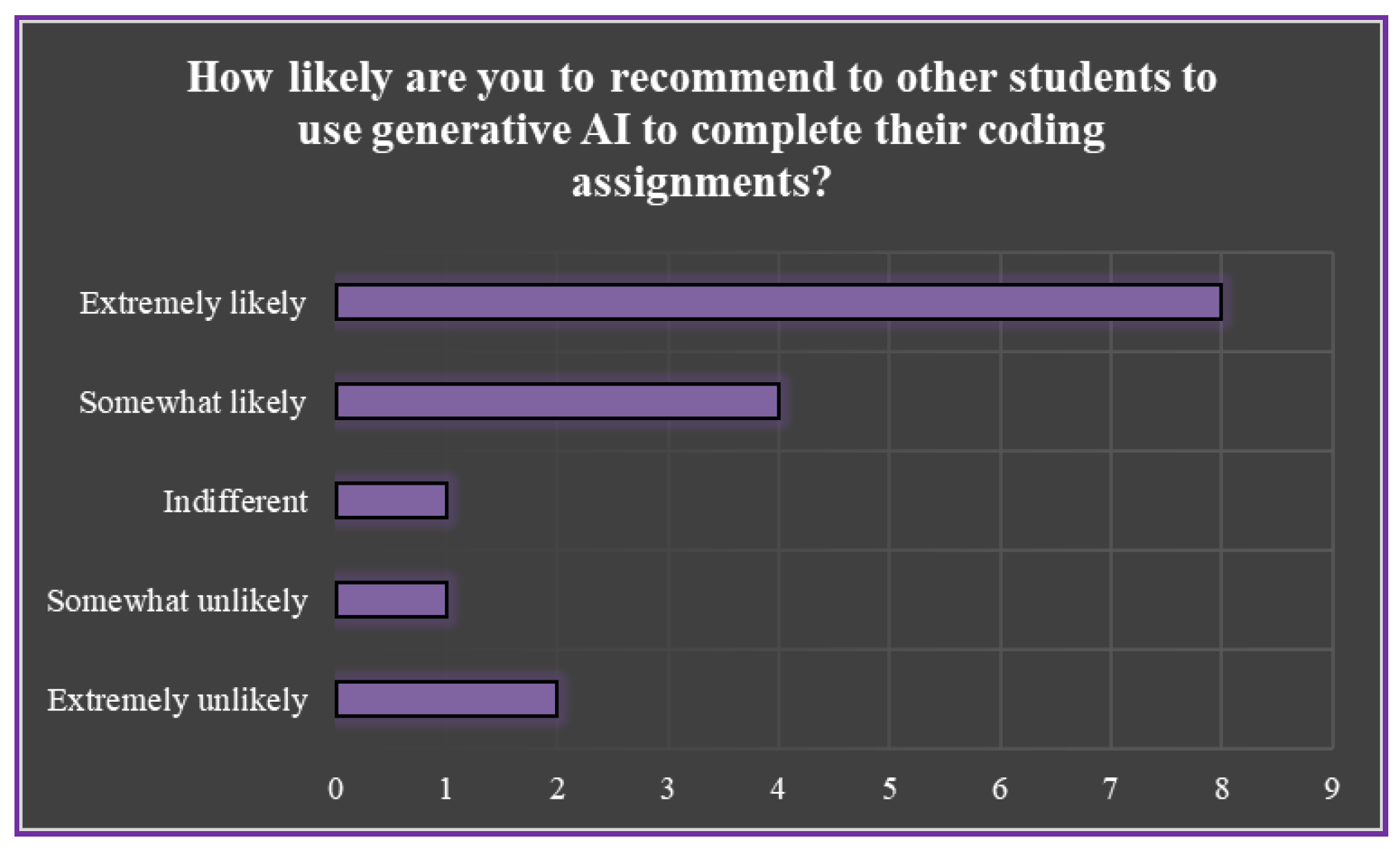

At the end of the course, sixteen of the eighteen participating students completed the survey with the majority being very enthusiastic about the use of GenAI for coding assignments. Fifteen out of sixteen students said that the course should continue to allow students to use GenAI to complete assignments. All students said that GenAI is useful to complete assignments, with 82% choosing very or extremely useful, 19% choosing moderately useful, and 0% choosing slightly or not at all. For the impact of GenAI on student learning, fourteen students stated that their understanding of code is better because of GenAI while two said it was worse. The likelihood that these students would recommend GenAI to other students for coding assignments varied, with 75% likely, 19% unlikely, and 6% indifferent.

Figure 3.

Students are predominantly likely to recommend GenAI to other students for completing coding assignments.

Figure 3.

Students are predominantly likely to recommend GenAI to other students for completing coding assignments.

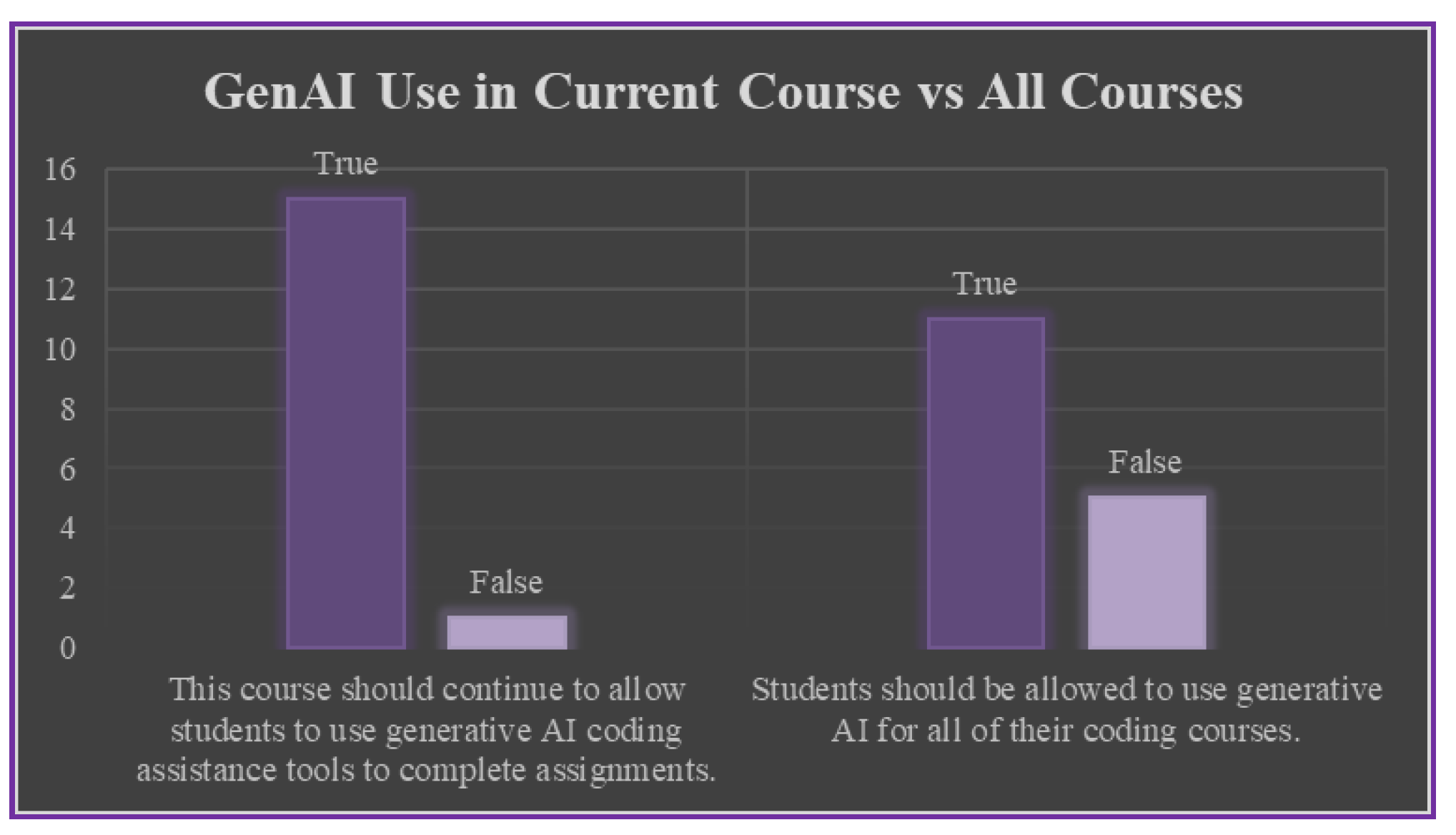

In an interesting comparison, while 94% of respondents believe this course should continue incorporating GenAI, only 69% say that all coding courses should use GenAI. At this time, the author would agree that some courses may not be suitable or appropriate for students to use GenAI, but more research is needed to make stronger conclusions on this topic.

Figure 4.

The adoption of GenAI into coding courses is encouraged by the majority of students in this survey.

Figure 4.

The adoption of GenAI into coding courses is encouraged by the majority of students in this survey.

In a multiple answer question, students were asked to share their feelings about using GenAI to complete assignments and, of the nine categories present, choose all that applied to them. Forty feelings were selected, and of those expressed, 81% were positive feelings including optimistic, empowered, excited, hopeful, and trusted. One respondent marked indifferent and the remaining 16% of selected options were unfavorable feelings including concerned, frustrated, and anxious.

Figure 5.

The vast majority of students expressed positive feelings for the use of GenAI.

Figure 5.

The vast majority of students expressed positive feelings for the use of GenAI.

Some behaviors of using GenAI were collected, including what students used the tool for and what they felt was the best part about using the tool. 100% of students used GenAI to explore new coding ideas, 87% used the tool for generated code, 73% would prompt in chat for additional clarity, 67% would study the generated code, and 60% worked with the tool to learn to debug coding errors. Four categories were listed for students to pick their favorite aspect of working with AI coding assistance. The top choice was

productivity (write code faster) with 40% of students selecting this as the best part of using GenAI.

Learning (understand code written) and

troubleshooting (learn to fix errors) both had 27% each, and

exploring (ask follow-up questions) had 7%. This data mirrors the 2024 Stack Overflow Developer Survey where

increase productivity was chosen as the biggest benefit of AI tools [

10].

Finally, an open-ended text question was given to ask for any additional feedback for faculty on the use of GenAI for this programming course. Seven comments were collected from respondents, with four expressing only positive feedback, two with mixed feedback, and one primarily against it. Some sentiments include:

Generative AI is like having your own personal tutor with you 24/7 who not only can give you the “skeleton” of a project allowing more time to fine tune, but can explain the concepts as much as you need to feel comfortable.

I’m definitely concerned about the misuse of AI, but it’s here to stay either way. Because of this, I think it’s incredibly helpful to use AI while writing code to generate basic structures, explain specific concepts, and diagnosing errors.

In my biased opinion I learn a lot more being forced to write the code myself.

I feel that generative AI is useful in more advanced courses, but in less advanced or ’introduction to coding’ type courses I feel like it cuts out a part of the coding process that is important to learn by just writing code from nothing yourself. I mostly avoided using generative AI for this course.

Using Copilot was a great experience, one of the most helpful things from it was getting clarification on code.

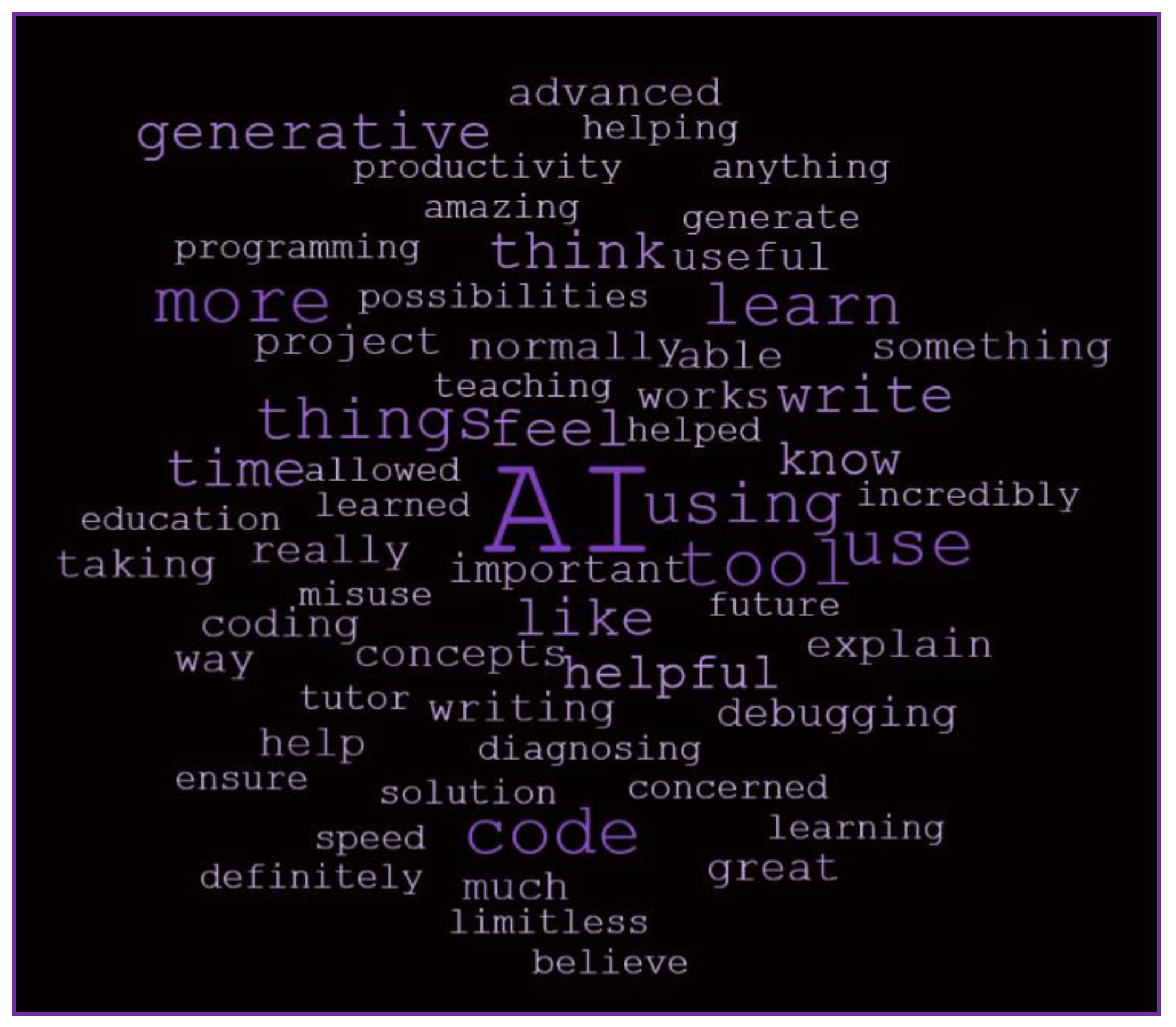

Figure 6.

Word cloud of the responses to Any additional feedback you would like to leave for faculty about the inclusion of generative AI in this course.

Figure 6.

Word cloud of the responses to Any additional feedback you would like to leave for faculty about the inclusion of generative AI in this course.

Overall, this survey shows great promise for student academic success and engagement through the inclusion of GenAI as a learning tool.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

It is risky to adopt a new learning tool, especially one as controversial as generative AI. Educators are encouraged to do their own research and experiments to decide how GenAI can assist their students, as it may not always be an appropriate choice for student learning. In the context of software development, where stakeholders are king, it is arguably less important for a program to be written from scratch than it is to be written within timeline and budget. The use of GenAI assistance gets code written faster, even if only used as a rough draft. But through this process of code generation, coupled with diligent debugging and testing, we can launch a new era of productivity for software developers.

Students who are permitted to use GenAI will not experience the anxiety of blank screen analysis paralysis, as they are able to generate code and begin writing and creating solutions immediately instead of being stuck with how to get started. This will build self-confidence and show students what is possible within themselves and within their coding environments to create impactful and professional software. Once a student sees what they are capable of, they are able to draw from this space of confidence when the software solutions grow more challenging. GenAI bridges the gap for student learning, providing all students with a solid draft to draw from.

Change has an ever-constant presence in our lives, and the people of Information Technology know this well. If we are to continue to serve our students in Computer Science, then we must lean into a new visage for software development and explore the benefits of generative AI. An honest look in the mirror might illuminate the ways our curriculum can evolve to enhance student learning, engagement, autonomy, curiosity, and retention.

References

- M. Tufano, A. Agarwal, J. Jang, R. Z. Moghaddam, and N. Sundaresan, “AutoDev: Automated AI-Driven Development,” Mar. 13, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2403.08299. Accessed: Mar. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2403.08299.

- M. Behroozi, C. Parnin, and T. Barik, “Hiring is Broken: What Do Developers Say About Technical Interviews?,” in 2019 IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing (VL/HCC), Memphis, TN, USA: IEEE, Oct. 2019, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Dr. A.Shaji George, “The Potential of Generative AI to Reform Graduate Education,” Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Lauren and P. Watta, “Work-in-Progress: Integrating Generative AI with Evidence-based Learning Strategies in Computer Science and Engineering Education,” in 2023 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), College Station, TX, USA: IEEE, Oct. 2023, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- B. Schultz, “Generative AI in Academics,” Sep. 12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Cui, M. Demirer, S. Jaffe, L. Musolff, S. Peng, and T. Salz, “The Effects of Generative AI on High Skilled Work: Evidence from Three Field Experiments with Software Developers,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Raigoza, “A study of students’ progress through introductory computer science programming courses,” in 2017 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Indianapolis, IN: IEEE, Oct. 2017, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Giannakos et al., “Identifying dropout factors in information technology education: A case study,” in 2017 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Athens, Greece: IEEE, Apr. 2017, pp. 1187–1194. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, J. Prather, and J. Edwards, “Generative AI in Education: A Study of Educators’ Awareness, Sentiments, and Influencing Factors,” 2024, arXiv. [CrossRef]

- “AI | 2024 Stack Overflow Developer Survey,” Stackoverflow.co, 2024. https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2024/ai#2-benefits-of-ai-tools.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).