1. Introduction

1.1. Background

In recent years, large language models (LLMs) have developed at an accelerated pace, leading to their adoption across various domains of education [

1]. These models have been applied in automated feedback, personalized tutoring, curriculum development, and multimodal learning support [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Their growing presence has introduced both new opportunities [

1,

7,

8,

9] and significant challenges [

1,

10].

LLMs can enhance access to learning resources, support creativity, and offer personalized experiences. On the other hand, they raise concerns about reliability, bias, and the need for new forms of digital literacy. Within this broader context, one emerging application of LLMs is text-to-image generation, which brings distinct implications for teaching and learning.

Text-to-image generation refers to AI systems that produce images from natural language descriptions (text prompts). Recent models, particularly those leveraging LLMs, can create remarkably detailed imagery from text inputs. Notable examples include OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Gemini, LLaVA, Kosmos-2, GigaChat, ERNIE Bot, MMReAct, Qwen-VL, Copilot, and similar platforms, which rose to prominence in 2021–2025. These rapid advances have broadened public awareness of generative AI’s “magic” and sparked interest in non-technical communities, including educators and students.

Notably, ChatGPT’s recent update on March 25, 2025, introduced the improved GPT-4o Image Generation model [

11], significantly enhancing image generation capabilities. This update enables ChatGPT to produce high-quality images directly within the chat interface, supporting iterative refinement through natural language prompts. Users can now more effectively specify details such as composition, color, and perspective, making the technology more accessible and powerful for educational applications. One notable enhancement is the ability to generate images in the style of Studio Ghibli anime, expanding creative and culturally resonant visual options for both teaching and learning.

The relevance of text-to-image AI to education is multifaceted. At a high level, it offers a new medium for creative expression and visualization in learning. An image has long been “worth a thousand words” in teaching, and now AI can potentially produce any image a learner or teacher can describe in words. This capability promises to democratize content creation—much as the camera once enabled anyone to capture reality without fine art training.

Educators are experimenting with generative tools to create custom visuals for lesson materials, while students use them to illustrate stories, design art projects, and even learn about AI. Likewise, many students have begun using generative image tools, bringing their perspectives on how AI fits into their learning processes. Some view it as a creative partner, while others raise critical questions about bias, authenticity, and skill development [

12].

This paper comprehensively reviews the opportunities and challenges of integrating text-to-image generation (especially LLM-based tools) in education. We draw on recent literature—including empirical studies and survey results—to illustrate how these AI tools are applied in various educational contexts, from creative literacy and curriculum design to domain-specific learning in science, history, art, and more. We also discuss technical, ethical, and pedagogical hurdles educators and learners face, such as algorithmic bias, misinformation, intellectual property concerns, and new digital literacy skills. We highlight student and teacher perspectives from recent pilot programs and classroom studies to ground the discussion in real-world experiences. By synthesizing these insights, we aim to elucidate best practices for harnessing text-to-image AI in learning while cautioning against its pitfalls.

1.2. Research Questions

According to the above background, this study was guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the educational opportunities and applications of text-to-image AI across different learning contexts?

RQ2: What are the technical, ethical, and pedagogical challenges associated with implementing text-to-image AI in education?

RQ3: What are students’ perspectives and experiences when using text-to-image AI as part of their learning process?

2. RQ1: Opportunities: Applications of Text-to-Image in Education

Text-to-image AI systems offer a range of opportunities to enhance teaching and learning. They can serve as creative catalysts, visualization tools, and even as study subjects in their own right. We conducted a comprehensive review of the existing literature [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] and concluded the findings.

This section explores a broad spectrum of applications—from fostering creative literacy and storytelling to providing teachers with on-demand custom visuals for any lesson. These uses span domains including STEM, the humanities, art and design, language learning, special education, and informal learning settings. Each example shows how AI-generated imagery can support and inspire learners, often in ways not previously feasible.

2.1. Creative Literacy and Visual Storytelling

An auspicious use of generative image tools lies in supporting creative literacy, encompassing the ability to express ideas through narrative and imagery. AI text-to-image generators acted as “illustration partners” for students seeking to transform written ideas into visual scenes. Educators often observed that these tools encouraged learners to expand their imagination and descriptive skills. For example, a creative writing exercise in which a student composed a short fairy tale and then used an AI prompt to visualize a key scene led to deeper storytelling and more immersive narratives.

In connection with this activity,

Figure 1 shows how an AI-generated castle image helped students refine their descriptive writing to match an envisioned fantasy setting.

Notably, ChatGPT’s recent update on March 25, 2025, introduced the improved GPT-4o Image Generation model [

11], significantly enhancing image generation capabilities. This update enables ChatGPT to produce high-quality images directly within the chat interface, supporting iterative refinement through natural language prompts. Users can now more effectively specify details such as composition, color, and perspective.

During such exercises, participants wrote personal narratives, produced detailed visual prompts, and generated images to spark further revisions. This process prompted them to refine descriptions of characters, settings, and style. Unexpected elements in the AI’s output frequently led to additional creative twists. Beyond illustrating existing texts, AI-generated images were prompts for new writing: some teachers displayed fantastical visuals to inspire learners who struggled with purely textual prompts. Others experimented with using AI to craft poems, comics, or short plays, combining words and images into a creative exercise. The challenge of selecting precise keywords often compelled students to think more carefully about language. When guided effectively, prompt-driven illustration heightened language use, creativity, and meta-cognitive awareness of how textual descriptions shaped outcomes.

2.2. Curriculum Development and Instructional Materials

Teachers and instructional designers likewise harnessed text-to-image AI to produce customized educational resources. Generative models created illustrative examples, diagrams, or scenarios that matched lesson objectives far more rapidly and cost-effectively than traditional artwork or stock-image searches. This capability allowed instructors to visualize everything from abstract mathematical concepts to detailed historical vignettes, enriching slides, worksheets, and assessments.

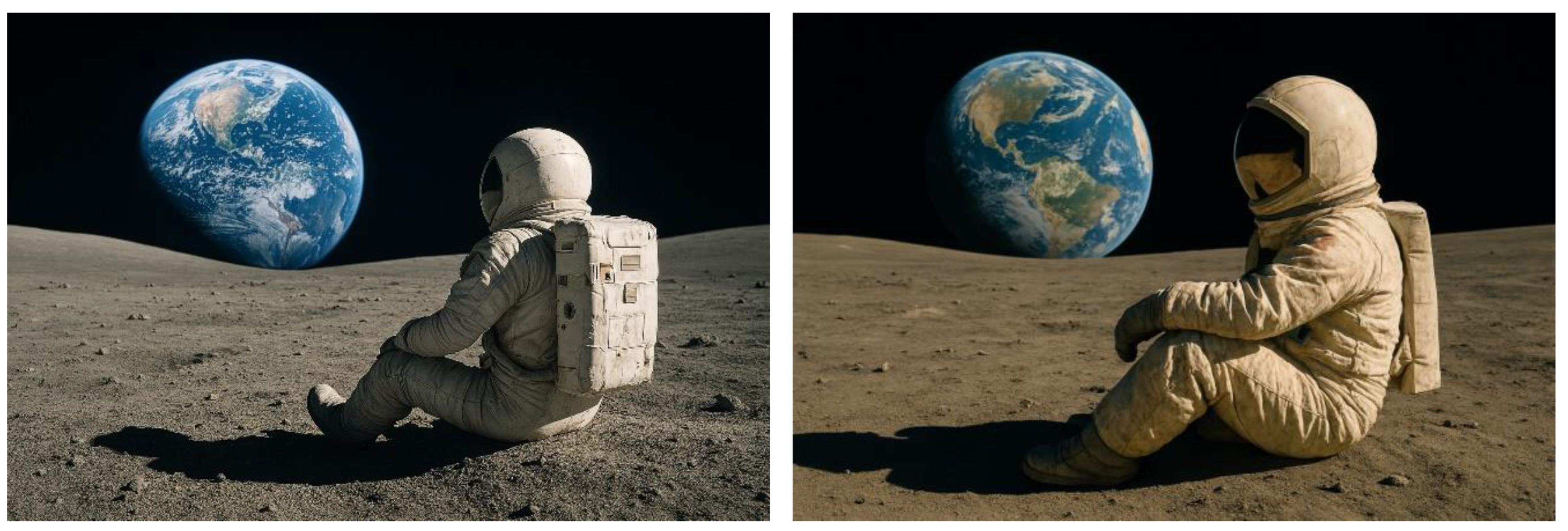

Figure 2 demonstrates how an AI-generated astronaut image, depicting an astronaut on the lunar surface with Earth in the background, can help immerse students in discussions about space exploration and lunar missions.

With prompts like this, a complex illustration that might have taken hours to produce by hand emerged in seconds. Teachers in budget-constrained settings found such a feature particularly advantageous, as it multiplied their visual resources. Additionally, the AI could produce multiple variations—changes in angle, style, or environment—thus enabling more flexible lesson design. Some educators even turned prompt-based image creation into a classroom challenge, guiding students to adjust parameters until they obtained the most fitting graphic for a given scenario.

2.3. STEM and Medical Applications

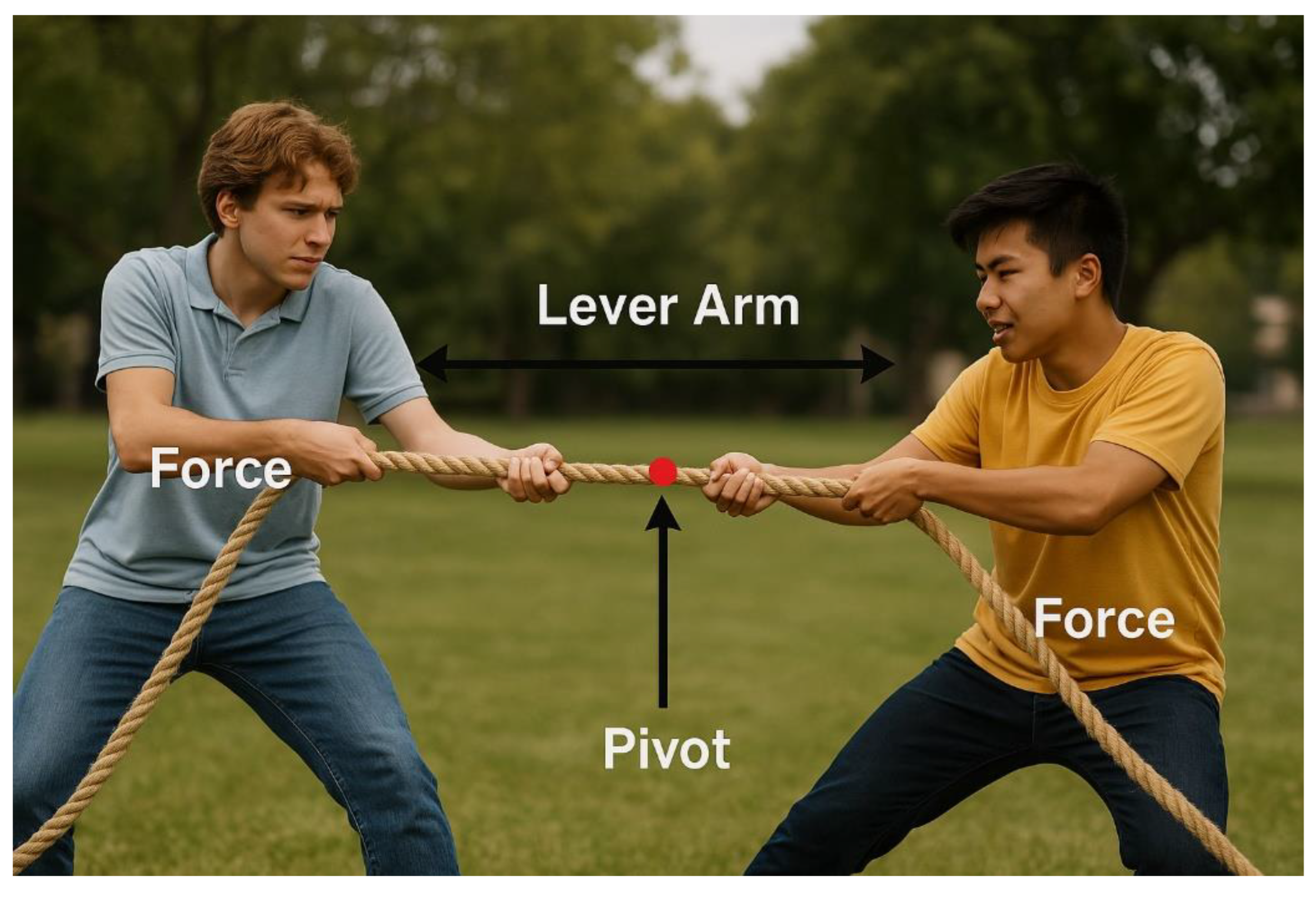

In science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, text-to-image AI proved especially useful for visualizing phenomena that are otherwise challenging to capture. Educators generated images to explain topics such as lever mechanics, gravitational forces, or molecular geometry.

For instance, in a physics classroom, instructors created visuals showing two students engaged in a tug-of-war, with arrows and labels overlaid to illustrate concepts like force, torque, and moment arms. Such diagrams helped students connect textbook definitions with real-world examples.

Figure 3 shows how AI can generate a physics diagram that combines realism with annotated vectors, making abstract mechanical concepts easier to understand. By adjusting prompts, educators could specify the direction of force, indicate the fulcrum, and highlight the effect of different arm lengths. This provided a clear and immediate way to support discussions about equilibrium, torque balance, and applied force.

In chemistry, instructors noted that while the AI could illustrate molecular bonds or reaction mechanisms, verifying the accuracy of bond angles, valence structures, or electron flow remained important before using such visuals as instructional tools. Physics teachers used the tool to enrich lessons on theoretical concepts such as black holes, wave interference, or quantum paradoxes by generating artistic renderings that invited discussion.

Medical and anatomical education instructors relied on prompt-based generation to depict structures like skulls, hearts, and brains. Students regularly required large numbers of detailed diagrams for study, but conventional sources often lacked enough variety or specificity. The AI, by contrast, produced customized cross-sections or labeled views in seconds. However, faculty members discovered that some images omitted critical details, such as foramina or particular vessels, so they treated the AI outputs as supplementary rather than definitive. In some courses, educators deliberately showed images containing inaccuracies and instructed students to find and correct them, turning possible flaws into learning moments.

Computer science classes also used text-to-image tools to visualize algorithmic ideas. In one assignment on fairness, students prompted the system with various stereotypes or biases and then analyzed how the resulting images revealed problematic training data. Learners deepened their understanding of algorithmic bias and the importance of inclusive data practices by examining where and why the AI reinforced or misconstrued social categories. Overall, text-to-image platforms provided a flexible medium for STEM teachers to support conceptual understanding and critical analysis.

2.4. History and Social Sciences

In history, social studies, and related areas, text-to-image AI allowed educators to reimagine past events or represent cultural settings. Rather than relying solely on archival images or paintings, teachers could summon nearly any historical scene or hypothetical scenario, which often increased learner engagement. In some lessons, students analyzed AI-generated historical images for inaccuracies or anachronisms, improving their analytical and critical-thinking skills.

Figure 4 demonstrates how text-to-image AI can help visualize a distant historical episode. Norse maritime expeditions, including trade and raids across Europe marked the Viking Age (ca. 793–1066 CE). While written sources and archaeological finds such as longships and runestones document these activities, no visual records from that time exist. AI-generated imagery allows students to imagine these events visually, supporting discussions about ship design, weaponry, and clothing. By comparing the image with historical sources, students can identify errors or anachronisms and reflect on the limits of visual reconstruction.

Another application arose in role-play exercises: learners would craft prompts from the point of view of someone living in a specific era or social context, detailing clothing, architecture, or rituals. The visuals generated from these prompts helped them envision daily life more concretely.

Figure 5 visually interprets a learner’s persona-based prompt, engaging students in the historical realities of slavery in the United States. The image can support discussion about plantation labor, housing conditions, and social hierarchies. Instructors used this approach to help students confront the material conditions of enslaved life and to assess how slavery shaped American society critically. Students might compare visual elements with primary sources, such as narratives by formerly enslaved people or abolitionist reports, deepening their understanding of this period.

In civics or current-events discussions, teachers used AI images to illustrate possible future scenarios—such as emerging technologies or climate change—making abstract policy debates more tangible.

Educators, however, recognized the need for caution. Highly realistic depictions of events that never took place risked misleading students who lacked contextual knowledge. Teachers addressed this by framing AI outputs as “artistic impressions” rather than verified sources. Some also integrated media-literacy components, asking students to investigate whether any records or trustworthy accounts supported the AI-constructed scenes. Despite the potential for misinformation, many educators found that the immersive quality of text-to-image visuals made challenging topics more accessible, especially when those topics involved distant times or emotionally charged issues.

2.5. Visual Arts and Design Education

Art and design programs frequently stood at the forefront of exploring text-to-image AI. Although these models introduced unprecedented creative opportunities—such as instant concept sketches, style experimentation, and algorithmic “co-creation”—they also sparked debates regarding authorship, originality, and the essence of human ingenuity. Educators in graphic design and architecture courses commonly integrated AI technology while emphasizing foundational skills and ethical considerations.

In graphic design courses, students learned to phrase conceptual ideas as prompts. This process demanded “AI visual literacy,” where learners succinctly described composition, lighting, textures, and color palettes. The AI introduced elements that diverged from a student’s initial intent, prompting iterative refinement or leading to novel, unforeseen directions. Educators noted that such experiences sharpened the students’ ability to communicate design goals clearly and to think flexibly during the creative process.

As illustrated in

Figure 6, architecture studios extensively used AI to generate rapid visual drafts. Students began with broad prompts—defining essential features like transparent facades or spacious interiors—then refined them step by step to reflect real-world constraints. This workflow expedited early design exploration, particularly for those less confident in freehand sketching. Even so, instructors cautioned that an overreliance on AI might diminish the practice of foundational drawing or the critical thinking needed to resolve functional challenges. Therefore, many assignments required learners to remix or complete AI-based images through manual techniques to ensure their vision remained primary.

Debates also emerged around the ethics of referencing particular artists or copyrighted works in prompts. Some instructors insisted on explicit disclosure whenever students used AI, emphasizing the importance of understanding and respecting intellectual property. While specific learners embraced AI as an inspirational tool akin to digital brushes, others questioned whether an algorithm could generate art with emotional resonance or depth. Design curricula evolved to include prompt engineering skills, guidelines on curating AI outputs, and discussions about creativity, fairness, and legal norms.

When integrated thoughtfully, text-to-image AI accelerated iteration and enhanced experimentation in art and design education, provided that educators preserved student agency and encouraged meaningful reflection on the human–machine creative process.

2.6. Cross-Linguistic and Multilingual Education

Language educators are finding inventive ways to use text-to-image AI to teach vocabulary and grammar in multilingual contexts. One key application is having students compose prompts in the target language to see if the AI produces the intended image – essentially using the model as a conversational partner that provides immediate visual feedback on language use.

For example, in an English class for Japanese learners, a teacher asked students to describe culturally familiar actions using English sentence patterns. One of the prompts was “A person is taking off their shoes before entering a tatami room.” This culturally specific behavior is hard to find in standard image databases but is typical in daily life and often appears in language textbooks. When students entered this prompt, the AI-generated an image of a person taking off shoes at the entrance of what looked like a Western living room (

Figure 7, left). The class discussed why the image was incorrect and identified that the LLMs might not have understood what a “tatami room” looks like. They revised the prompt to include more context: “A person is taking off their shoes before entering a traditional Japanese tatami room with sliding doors.” The updated input produced a more accurate image showing a person at the entrance of a Japanese-style room with tatami mats and shoji doors (

Figure 7, right). This led to discussions about vocabulary and sentence structure and how to express cultural knowledge clearly in another language.

Text-to-image tools thus reinforce cross-linguistic skills by requiring precision and context in the target language. Students are motivated to use new vocabulary and correct structures to “get the image right,” essentially gamifying the practice of writing in a foreign language. Beyond grammar, the approach can deepen cultural learning: teachers can prompt images of culturally specific scenes (like a Japanese tea ceremony described in Japanese, or a Mexican market described in Spanish), and then discuss the cultural elements visible in the pictures. It’s also helpful for building multilingual glossaries – for instance, generating a series of labeled images for common household items with captions in both the native language and the language being learned. While AI image generators are not flawless translators, when used under guidance, they encourage active language production and can catch learners’ errors in a memorable, visual way. This immediate feedback loop supports language acquisition and engages students in communicative practice that feels purposeful and fun.

2.7. Special Education and Accessibility

Text-to-image AI also shows promise in special education, by generating personalized visual supports and learning materials for students with disabilities. Many learners with cognitive or communication challenges, such as those on the autism spectrum, benefit from visual aids like social stories, picture schedules, and realistic scenario images.

Traditionally, preparing these supports can be time-consuming – teachers or parents might search for appropriate photos or take them manually. AI generation offers a way to create tailored visuals quickly from a prompt, allowing adults to adjust content to a child’s specific needs, interests, or daily routines.

For example, a parent could prompt an image of “Maria packing her school bag in the morning” to illustrate a routine checklist. Alternatively, a speech therapist might generate a sequence showing a child initiating play with peers to support social interaction learning.

In

Figure 8, the AI-generated scene depicts a peer helping a fallen child, serving as a visual element in a social story about empathy and supportive behavior. The image was generated in the style of Studio Ghibli anime, with soft colors, expressive characters, and a gentle atmosphere. Using illustration styles like this can increase accessibility and clarity, especially for children benefitting from simplified or symbolic representations of social situations.

A recent development in this field is the AI-assisted creation of complete picture books and social narratives for neurodiverse children. Early applications suggest that by adjusting prompts and visual detail (e.g., using plain, clutter-free backgrounds and consistent characters), AI can produce image sequences that align with the processing and comprehension styles of students with autism or learning disabilities. These visuals can also incorporate specific preferences, such as including familiar objects or familiar types of clothing, to increase engagement through personalization.

Accessibility benefits extend further: image outputs can include alt-text, and prompts may be linked with text-to-speech tools to support learners with limited vision or reading ability. Generative models can also adapt image complexity on demand – minimal prompts for students who prefer simplicity or more detailed prompts when context enrichment is helpful.

While educators emphasize the need to review AI outputs for accuracy and appropriateness, many see value in how this technology enables the rapid development of customized visual materials. For students who rely on visual scaffolding, text-to-image AI offers a practical tool for making content more responsive, inclusive, and aligned with individual learning profiles.

2.8. Informal Learning Environments (Afterschool or Home Education)

Outside traditional classrooms, text-to-image AI tools enrich learning in museums, libraries, afterschool programs, and home education. Informal learning environments often seek to provide immersive, engaging experiences, and generative AI offers a new way to achieve that.

For instance, museums are beginning to experiment with interactive displays where visitors can request AI-generated images to visualize historical or scientific content. Imagine a museum exhibit on ancient civilizations that lets attendees type in a description – say, “the Library of Alexandria at night” – and instantly see an AI’s interpretation on a screen. This on-demand visual can make museum experiences more participatory. Curators of cultural heritage have used AI to recreate historical sites as they once stood.

Figure 9 shows a possible reconstruction of a Greek temple generated from text. By comparing the generated reconstruction with photographs of the current ruins, visitors gain a deeper appreciation of history and architecture, sparking discussion about how we infer the past from limited evidence. Similarly, science centers might employ text-to-image kiosks for visualizing phenomena: a prompt like “dinosaur with its young in a Jurassic forest” could complement fossil displays with a vivid, if speculative, scene of prehistoric life.

Homeschooling parents and tutors are also incorporating these tools to create more dynamic learning materials on the fly. In a homeschool setting, a student’s curiosity can be immediately explored by generating images that answer questions or provoke investigation.

For example, during a homeschool unit on world cultures, a student could ask, “What did ancient Egyptian markets look like?” and work with a parent to craft a prompt that produces a colorful market scene. The family can then discuss which elements match historical records and which might be imaginative, thereby practicing critical thinking.

Afterschool programs focused on art or technology have started to include AI image generation as an activity, teaching kids how to use the tools creatively and responsibly. In a digital art club, students might recreate scenes from their favorite books or design concept art for a game storyline they invent. This not only hones their artistic and narrative skills but also introduces them to AI literacy in a hands-on way outside of the formal curriculum. The informal context often gives learners more freedom to experiment without the pressure of grades, leading to playful learning experiences that still build knowledge. Whether in a museum hall or at the kitchen table, text-to-image AI can transform curious questions and ideas into visual explorations, making learning spontaneous and highly personalized.

2.9. AI Literacy and Critical Thinking

As text-to-image generators become more prevalent, educators emphasize teaching AI literacy and critical thinking alongside subject-specific content. This involves helping students understand how generative models function, their limitations, and how to evaluate their outputs critically. One effective approach is to use highly realistic yet scientifically implausible images to encourage skepticism and analytical reasoning. These images can serve as entry points for discussions about trust in visual media, the reliability of AI-generated content, and the importance of verification in an age of manipulated visuals.

In

Figure 10, students may be shown a convincing image of an advanced human settlement on Mars, complete with architectural detail and atmospheric lighting. At first glance, the image may appear plausible. However, students begin to identify inconsistencies through guided questioning—such as “Could this image depict a real scene?” or “What features suggest AI generated it?”. These might include unrealistic planetary scales or impossible lighting conditions. This exercise sharpens their ability to detect fabricated content and reinforces the need to corroborate visual evidence with scientific knowledge and trusted sources.

Beyond passive critique, actively involving students in generating such images can deepen their understanding. For example, learners might experiment with prompt variations in a computer science or digital citizenship setting to observe how demographic or occupational biases appear in AI outputs. This facilitates discussion about algorithmic bias, training data, and the social implications of generative tools. Some schools have extended this into interdisciplinary activities where students act as “AI investigators”, producing images and reflecting on the ease of image manipulation versus the difficulty of verification. By framing text-to-image generation as a topic of inquiry, educators support technical comprehension and the development of critical digital judgment. Students learn not only to ask “How was this created?” but also “Why should (or shouldn’t) I believe this image?”—a core skill in navigating AI-mediated communication.

4. RQ3: Student Perspectives on Text-to-Image AI

In addition to examining the applications and challenges of text-to-image AI in education, we conducted a qualitative study exploring how primary school students experience and perceive this technology in their learning environment. The study involved 30 Macao primary school students aged 9-12 who participated in an 8-week computer science program using Microsoft Copilot to generate images of global cities. Students attended 4 sessions per week, totaling 32 classes of 40 minutes each.

Microsoft Copilot was selected for this classroom study primarily due to its accessibility in a large-group educational setting. Unlike ChatGPT 4o, whose frequent image generation features require a paid subscription, Microsoft Copilot allows access to text-to-image functionality through a standard Office login. This reduced the cost barrier and made it feasible to implement across all students in the program.

During this program, students selected cities of personal interest and crafted prompts to generate images showcasing urban characteristics, cultural landmarks, and distinctive features. Below is an illustration of a prompt centered on Washington, DC, United States.

Figure 11 shows how one might create a visual of city landmarks in a single sunrise panorama by students.

Following the experiment, we interviewed some participants to gather their impressions and experiences. Their responses revealed several key themes regarding the educational impact of text-to-image AI tools, which we present in the following subsections.

4.1. Heightened Engagement and Visual Discovery

Students consistently reported high levels of engagement when using text-to-image AI to explore global cities. The immediacy of seeing their text prompts transformed into visual representations created a sense of wonder that maintained their interest throughout the program. Many participants described the experience as more engaging than traditional computer science lessons because it allowed them to actively participate in creating visual content rather than passively consuming it.

S7: “I never thought I could make pictures with just words! When I typed about the Great Wall of China and saw it appear with all those bricks and mountains, it felt like magic. It made me want to learn about more places so I could make more cool pictures.”

S21: “My favorite part was seeing how the pictures changed when I changed my words. Once I wrote about Tokyo at night with all its lights, and it looked amazing! Then I tried Tokyo in daytime, and it was completely different. I could explore the same city in different ways just by changing a few words.”

Students particularly appreciated the ability to visualize places they had never seen before, which expanded their geographical awareness beyond textbook descriptions. The ability to generate multiple variations of the same location also encouraged comparative thinking as they noticed differences in architecture, landscapes, and cultural elements across diverse urban environments.

S14: “Before, I only knew Paris had the Eiffel Tower because I saw it in movies. But when I used Copilot, I discovered so many other beautiful buildings and bridges I didn’t know about. Now I want to visit Paris someday and see all those places for real.”

The visual discovery process stimulated curiosity about cultural and geographical details that might otherwise have been overlooked in traditional learning materials. This curiosity often extended beyond the classroom as students reported continuing their exploration at home, indicating sustained interest in the subject.

4.2. Descriptive Language Development

One unexpected benefit of the study was the significant improvement in students’ descriptive vocabulary and language precision. As students quickly discovered that more detailed prompts produced better images, they were naturally motivated to expand their descriptive capabilities. This created an authentic context for language development as students sought increasingly specific terms to achieve their desired visual outcomes.

S3: “At first, I just wrote ’Sydney Opera House’ and the picture was okay. But then I learned to write ’Sydney Opera House with white sail-shaped roofs glowing in the sunset with harbor waters reflecting orange light.’ That picture was amazing! Now I use more describing words in all my writing.”

S26: “I had to look up words like ’architecture’ and ’metropolitan’ to make better pictures. My teacher was surprised when I used ’ornate’ to describe buildings in Barcelona. I didn’t know these words before, but now I use them all the time because they make my pictures look exactly how I want.”

They refined their prompts on their own without receiving explicit instruction. This language development extended to their general writing, as reported by several language arts teachers who noticed increased descriptive richness in students’ creative writing assignments.

S18: “When the first picture of Rome didn’t show the Colosseum how I imagined it, I had to think about what words would make it look ancient and huge. I tried ’massive stone arches’ and ’weathered by thousands of years’ and it worked! Now I know how to make my stories sound better too.”

The iterative process of refining prompts to achieve desired visual outcomes created a practical application for vocabulary expansion. Students became more aware of how specific language choices impact communication clarity, a skill that transfers to multiple academic areas.

4.3. Cultural Awareness and Global Perspective

The program significantly enhanced students’ cultural awareness and global perspective as they discovered distinctive features of cities worldwide. Many students reported gaining new insights into cultural diversity and developing an appreciation for architectural styles, urban planning, and cultural landmarks across different regions. This expanded their worldview beyond their immediate environment.

S11: “I chose Kyoto because my favorite cartoon character is from Japan. But I learned so much more! I didn’t know about the bamboo forests and old temples there. The pictures showed how Japan keeps its traditional buildings even though it’s modern too. That’s different from my city where everything looks new.”

S29: “When I compared pictures of Cairo and New York, I noticed how buildings look so different because of their history and weather. Cairo has these cool geometric patterns and flat roofs, while New York has super tall glass buildings. It made me think about why cities look the way they do.”

Students began recognizing architectural elements unique to specific cultures and regions, developing visual literacy that helped them identify cities based on distinctive features. Some students also demonstrated increased cultural sensitivity by asking thoughtful questions about why certain cities developed in particular ways.

S5: “I generated pictures of Venice with all its canals and Rio de Janeiro with mountains right next to the beach. It made me realize how much the land changes how people build cities. Now when I see a new place, I think about how it got shaped by where it is.”

The ability to visually compare global cities reinforced students’ understanding of human geography concepts more engagingly than traditional textbooks. Many reported feeling more connected to distant places after visualizing them through AI-generated images, strengthening their sense of global citizenship.

4.4. Technological Literacy and Critical Evaluation

As students worked with Microsoft Copilot, they developed greater technological literacy and critical evaluation skills. They quickly learned that AI-generated images, while impressive, did not always accurately represent reality. This realization prompted meaningful discussions about AI limitations and the need to verify information—an essential digital literacy skill in today’s information landscape.

S8: “Sometimes Copilot made mistakes, like putting the wrong buildings in a city or making things look weird. Our teacher showed us real photos to compare, and we discussed why AI gets confused. Now I know I should always check if computer-made images are correct.”

S17: “I noticed that when I asked for pictures of Dubai, it always showed the really fancy buildings and beaches, not the normal parts where regular people live. It made me think about how pictures can make us believe things that aren’t completely true about a place.”

Students developed an increasingly sophisticated understanding of how AI tools interpret text prompts, gaining insight into the technology’s capabilities and limitations. They began to recognize patterns in how the AI responded to certain types of language, which fostered critical thinking about technological tools more broadly.

S24: “I learned that you have to be really specific or the AI might get confused. Once I asked for a picture of ’Paris’ and it showed me Paris, France, but when my friend asked for ’Paris’ it showed a different view. We figured out you need to say exactly what parts you want to see, or it just guesses.”

This developing critical awareness extended beyond the classroom as students reported applying similar evaluation skills to other digital content they encountered. Several mentioned becoming more cautious about trusting images they saw online, indicating growth in media literacy.

4.5. Challenges and Frustrations

Despite overwhelmingly positive experiences, students encountered various challenges and frustrations when working with text-to-image AI. These difficulties provided valuable learning moments but also highlighted essential considerations for implementing such technology in primary education settings.

S12: “Sometimes it was really annoying when the computer didn’t understand what I wanted. I tried to get a picture of Machu Picchu with the right mountains, but it kept looking wrong no matter how I described it. It made me feel like giving up after trying five times.”

S19: “The hardest part was when me and my friend used exactly the same words but got different pictures. It didn’t seem fair. I spent a long time thinking of good words for my prompt, but his picture still looked better than mine even though he didn’t try as hard.”

Technical limitations occasionally created barriers to learning, particularly when the AI failed to interpret culturally specific references or produced inconsistent results from similar prompts. Students with less developed vocabulary sometimes struggled to refine their prompts effectively, leading to feelings of frustration.

S4: “When we learned about bias, it was confusing. Our teacher showed how asking for ’a typical city street’ mostly showed American or European places, not African or Asian ones. It made me wonder if the computer thinks some places are more important than others.”

These challenges prompted essential discussions about AI ethics and bias, helping students develop more nuanced perspectives on technological tools. Despite occasional frustrations, most students viewed these difficulties as puzzles to solve rather than insurmountable obstacles, demonstrating resilience in their learning process.

4.6. Collaborative Learning and Peer Inspiration

The text-to-image activities fostered rich collaborative learning environments as students shared their prompts, compared results, and built upon each other’s ideas. This social dimension significantly enhanced engagement and created opportunities for peer-to-peer learning that extended beyond the technical aspects of using the tool.

S2: “When my peer showed his amazing picture of Istanbul with all the mosques and water, I asked him how he did it. He taught me to use words like ’panoramic view’ and ’ornate domes’ that I didn’t know before. We started a competition to see who could make the best city pictures.”

S16: “Our group made a collection of night scenes from different cities around the world. Someone would find a cool way to describe lights or reflections, and then we’d all try using that in our own prompts for different cities. It was fun seeing how the same describing words worked differently for Tokyo versus London.”

Students frequently exchanged successful prompt strategies and vocabulary terms, creating an organic peer teaching environment. This collaboration helped less confident students overcome initial barriers and expanded the collective knowledge of the entire class.

S23: “My partner was really good at thinking of detailed prompts, and I was good at spotting when things looked wrong in the pictures. We made a good team because we could help each other make better city images than we could by ourselves.”

The collaborative aspects of the program extended learning beyond individual discovery to include social negotiation of meaning and collective problem-solving. When the AI produced unexpected results, students often worked together to analyze why their prompts might have been misinterpreted, developing shared strategies for improvement.

4.7. Creativity and Imaginative Exploration

The text-to-image activities sparked creative thinking and imaginative exploration as students moved beyond generating straightforward city representations to envisioning cities in various contexts, time periods, or hypothetical scenarios. This creative dimension engaged students’ imaginative faculties while maintaining connections to geographical learning.

S10: “My favorite part was creating ’what if’ cities. I made pictures of ’What if Rio de Janeiro had snowy mountains instead of sunny beaches?’ and ’What if New York was built in the desert?’ It was fun to imagine how cities would look different if they were in different places.”

S27: “I learned how cities change over time, so I tried making pictures of ’Tokyo 100 years ago’ and ’Tokyo 100 years in the future.’ It was amazing to see how the same place could look so different. The old Tokyo had wooden buildings and the future Tokyo had flying cars and super tall towers.”

Students demonstrated remarkable creativity in their approaches, often combining cities with seasonal changes, historical periods, or fantasy elements. This imaginative engagement deepened their connection to the geographical content while exercising creative thinking skills.

S13: “After seeing all the normal city pictures, I wanted to try something different. I asked for ’Venice during Carnival with people wearing masks and colorful costumes’ and it made an amazing picture! Then everyone started thinking of special events in different cities to make their pictures more interesting.”

This creative exploration often led to more profound questions about urban development, cultural events, and how cities adapt to their environments. The imaginative component of the activity maintained high engagement levels throughout the program as students continually found new creative angles to explore.

The study revealed that text-to-image AI tools offer significant educational potential in primary school settings, particularly in enhancing engagement, language development, cultural awareness, and technological literacy. While challenges exist, thoughtful implementation can transform these tools into valuable resources for expanding students’ global understanding and creative expression.

5. Conclusions

This comprehensive review examined the integration of text-to-image AI in educational contexts, focusing on applications, challenges, and student perspectives. The findings across our three research questions revealed a nuanced landscape with significant potential and essential considerations for implementation.

Regarding RQ1 on educational opportunities, our analysis identified nine key application areas where text-to-image AI demonstrated educational value. Creative literacy and visual storytelling emerged as promising domains, with AI-generated imagery as a catalyst for descriptive writing and narrative development. The technology proved valuable for curriculum development, enabling educators to produce customized visuals that aligned with specific learning objectives rapidly. In STEM fields, text-to-image AI facilitated the visualization of complex concepts, from molecular structures to physical forces, though accuracy verification remained essential. Historical and social science education benefited from the ability to recreate distant times and places, making abstract concepts more tangible for learners. In visual arts and design education, the technology functioned as a rapid prototyping tool that accelerated the creative process while raising important questions about artistry and originality.

Cross-linguistic education represented another significant application area, with text-to-image AI providing immediate visual feedback on language use and cultural comprehension. Special education and accessibility applications demonstrated how personalized visual supports could be generated quickly for diverse learning needs. From museums to homeschooling settings, informal learning environments used text-to-image generation to create more responsive, immersive experiences. Finally, technology became a study subject, supporting AI literacy and critical thinking about digital media. Across all these contexts, text-to-image AI demonstrated the potential to democratize visual content creation and enhance engagement through personally relevant imagery.

In addressing RQ2 on challenges, we identified several categories of limitations educators encountered. Technical challenges included accuracy inconsistencies, particularly in specialized domains requiring precision, and difficulties with prompt engineering that demanded new skills from educators. Resource constraints affected implementation in settings with limited technological infrastructure, while safety and content filtering revealed the need for robust oversight systems. Ethical concerns centered on bias in visual representation, which often reproduced societal stereotypes unless explicitly mitigated through careful prompting. The potential for misinformation posed serious challenges to educational integrity, requiring teachers to emphasize source verification and critical media literacy. Data privacy and intellectual property questions complicated classroom implementation, particularly regarding student information and the ethical use of AI-generated content.

Pedagogical challenges included ensuring alignment with learning objectives, as the technology sometimes distracted from core skills development. Assessment and academic integrity concerns required new approaches to evaluating student work incorporating AI tools. Classroom management issues arose from unequal access to resources and the potential for student distraction during experimentation. Teacher professional development emerged as crucial but often insufficient, with many educators feeling unprepared to navigate complex technical and ethical questions. Finally, curricular relevance required careful consideration to ensure that text-to-image activities genuinely enhanced established learning goals rather than functioning as technological novelties.

Our examination of RQ3 revealed rich insights into student perspectives through our qualitative study with primary school students. Heightened engagement and visual discovery characterized their experiences, with the immediacy of image generation creating a sense of wonder that sustained interest in geographical content. Descriptive language development occurred organically as students refined their prompts, expanding vocabulary and precision to achieve desired visual outcomes. Cultural awareness and global perspective were enhanced as students explored distinctive features of cities worldwide, developing visual literacy and recognizing architectural differences. Technological literacy and critical evaluation skills emerged as students encountered AI limitations and learned to verify information against other sources.

Despite occasional challenges and frustrations with technical limitations or inconsistent results, students demonstrated resilience and problem-solving in overcoming difficulties. Collaborative learning flourished as students shared successful strategies and built upon each other’s ideas, creating organic peer teaching environments. Finally, creativity and imaginative exploration characterized many students’ approaches as they moved beyond straightforward representation to envisioning hypothetical scenarios, historical variations, or future possibilities.

Overall, these findings suggest that text-to-image AI offers significant educational potential when implemented thoughtfully. The technology can engage students, enhance visualization across subjects, support personalized learning, and develop critical digital literacy. However, realizing these benefits requires addressing substantial challenges through careful planning, appropriate safeguards, and ongoing critical reflection. As LLM-based image generation continues to evolve—exemplified by recent advances like ChatGPT’s GPT-4o update—the educational opportunities are likely to expand further, underscoring the importance of developing pedagogical frameworks that harness these tools responsibly.

Future research should investigate longitudinal impacts on skill development, explore implementation strategies across diverse educational contexts, and examine potential differences in effectiveness across age groups and subject areas. Additionally, as the technology evolves, ongoing assessment of educational applications will be necessary to ensure alignment with core learning objectives. By continuing to study opportunities and challenges, educators can work toward integrations that enhance rather than detract from meaningful learning experiences.

Figure 1.

Fantasy Castle Visualization Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 29-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “A fantasy castle perched on a cliff at sunset, with warm orange light and dramatic clouds.”).

Figure 1.

Fantasy Castle Visualization Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 29-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “A fantasy castle perched on a cliff at sunset, with warm orange light and dramatic clouds.”).

Figure 2.

Astronaut Illustration Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “An astronaut sitting on the lunar surface, Earth rising over the horizon, photo-realistic.”).

Figure 2.

Astronaut Illustration Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “An astronaut sitting on the lunar surface, Earth rising over the horizon, photo-realistic.”).

Figure 3.

Lever and Force Illustration Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “Two students playing tug-of-war, realistic style, with overlaid arrows and labels showing force direction, lever arm length, and pivot point.”).

Figure 3.

Lever and Force Illustration Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “Two students playing tug-of-war, realistic style, with overlaid arrows and labels showing force direction, lever arm length, and pivot point.”).

Figure 4.

Historical Reconstruction of a Viking Raiding Expedition Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 29-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “A Viking longship navigating stormy seas toward a coastal European village in the 9th century, with warriors preparing for a raid, depicted in a historically accurate style.”).

Figure 4.

Historical Reconstruction of a Viking Raiding Expedition Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 29-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “A Viking longship navigating stormy seas toward a coastal European village in the 9th century, with warriors preparing for a raid, depicted in a historically accurate style.”).

Figure 5.

Role-Play Prompt Visualization Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “As an enslaved person on a cotton plantation in the American South in the 1850s, describe your living conditions, daily labor, and the people around you.”).

Figure 5.

Role-Play Prompt Visualization Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “As an enslaved person on a cotton plantation in the American South in the 1850s, describe your living conditions, daily labor, and the people around you.”).

Figure 6.

Architectural Concept Rendering Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “A conceptual public building with glass walls, high ceiling, and open interior spaces, bird’s-eye view.”).

Figure 6.

Architectural Concept Rendering Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “A conceptual public building with glass walls, high ceiling, and open interior spaces, bird’s-eye view.”).

Figure 7.

Removing Shoes before Entering a Tatami Room Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Left: Initial prompt “A person is taking off their shoes before entering a tatami room.” Right: Revised prompt “A person is taking off their shoes before entering a traditional Japanese tatami room with sliding doors.”).

Figure 7.

Removing Shoes before Entering a Tatami Room Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Left: Initial prompt “A person is taking off their shoes before entering a tatami room.” Right: Revised prompt “A person is taking off their shoes before entering a traditional Japanese tatami room with sliding doors.”).

Figure 8.

One Child Helping Another Stand Up in Ghibli Style Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “Illustration of a child helping another child who has fallen on a school playground, cartoon style, soft colors, friendly facial expressions, simple background.”).

Figure 8.

One Child Helping Another Stand Up in Ghibli Style Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “Illustration of a child helping another child who has fallen on a school playground, cartoon style, soft colors, friendly facial expressions, simple background.”).

Figure 9.

An Ancient Greek Temple on a Hill Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “Photorealistic aerial view of an intact ancient Greek temple on a hill, surrounded by olive trees and an old village.”).

Figure 9.

An Ancient Greek Temple on a Hill Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “Photorealistic aerial view of an intact ancient Greek temple on a hill, surrounded by olive trees and an old village.”).

Figure 10.

Futuristic Colony on Mars Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “Ultra-realistic photo of a human city on the surface of Mars, with the planet Earth visible in the Martian sky.”).

Figure 10.

Futuristic Colony on Mars Generated by ChatGPT 4o on 30-Mar 2025 (Prompt: “Ultra-realistic photo of a human city on the surface of Mars, with the planet Earth visible in the Martian sky.”).

Figure 11.

Exploration of Washington, DC Landmarks Generated by Microsoft Copilot on Mar 2025 (Prompt: “A panoramic view of Washington, DC at sunrise, featuring the Capitol building, Washington Monument, and Lincoln Memorial in a realistic style.”).

Figure 11.

Exploration of Washington, DC Landmarks Generated by Microsoft Copilot on Mar 2025 (Prompt: “A panoramic view of Washington, DC at sunrise, featuring the Capitol building, Washington Monument, and Lincoln Memorial in a realistic style.”).