Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Individual Factors and Job Satisfaction

2.2. Occupational Factors and Job Satisfaction

2.3. Institutional Factors and Job Satisfaction

2.4. Socio-Demographic Factors and Job Satisfaction

2.5. Machine Learning in Predicting Job Satisfaction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Population and Sample

3.3. Data Collection Instrument

3.4. Procedure

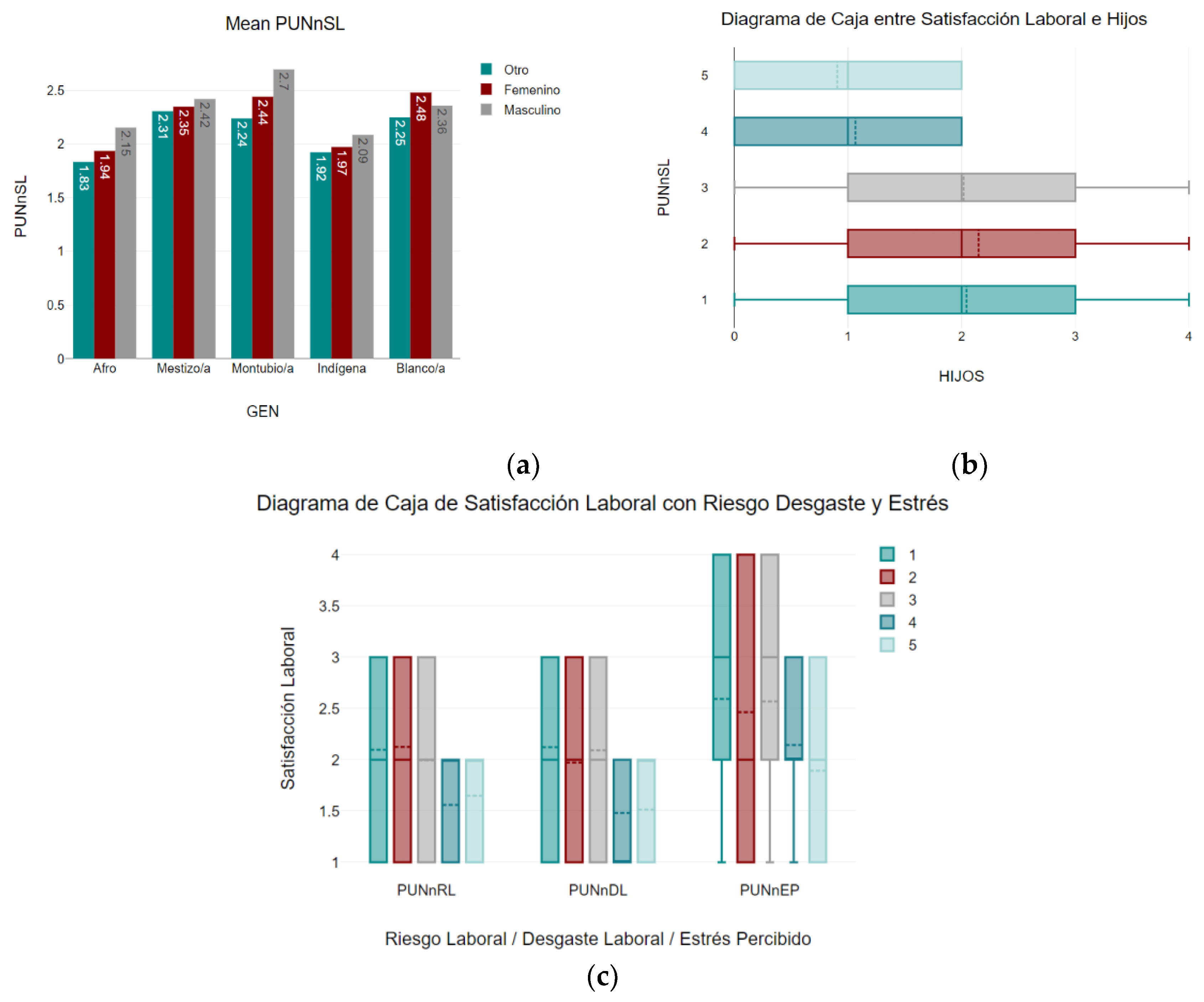

3.5. Descriptive Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Description

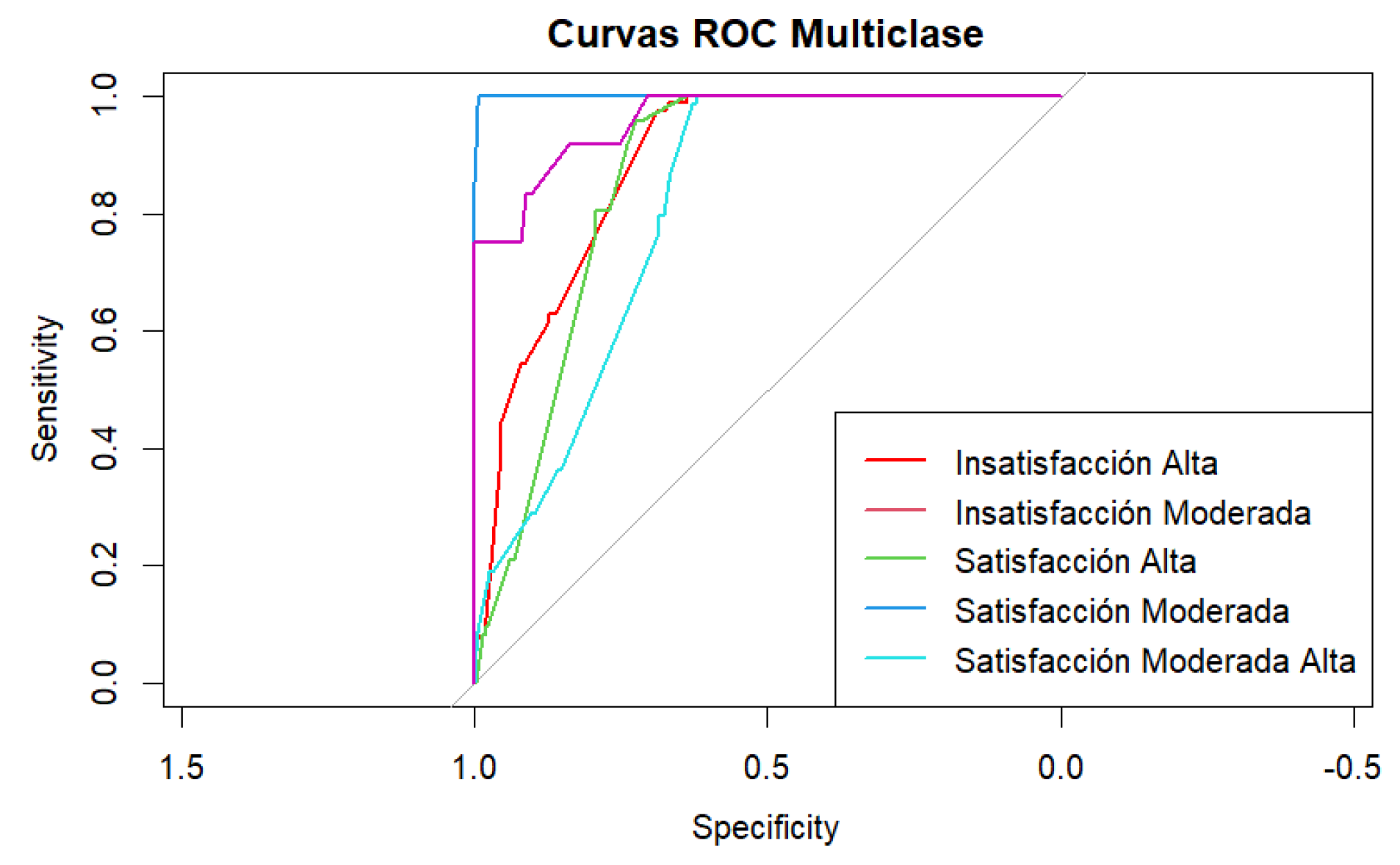

4.2. Clasification Results

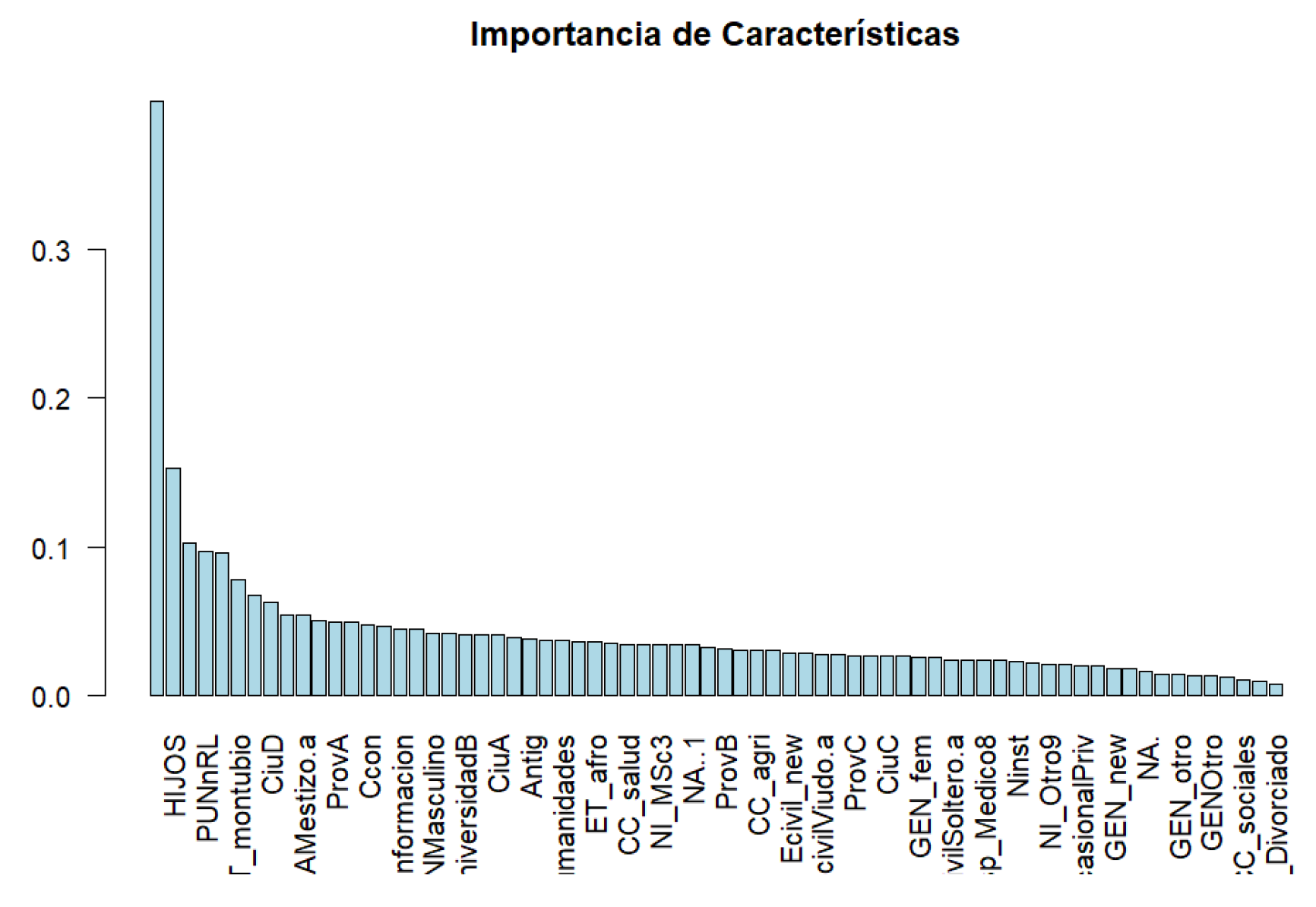

4.3. Feature Importance

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

6. Implications

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Ducharme, M.J.; Martin, J.K. Unrewarding work, coworker support, and job satisfaction: A test of the buffering hypothesis. Work and Occupations 2000, 27(2), 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. Work, happiness, and unhappiness; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin 2001, 127(3), 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshagbemi, T. Gender differences in the job satisfaction of university teachers. Women in Management Review 2000, 15(7), 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E. Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences; Sage, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dinham, S.; Scott, C. Moving into the third, outer domain of teacher satisfaction. Journal of Educational Administration 2000, 38(4), 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.G.L.d.V.; Costa, N.M. Factors connected with professional satisfaction and dissatisfaction among nutrition teachers. Cien Saude Colet 2016, 21(8), 2357–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Cicotto, G.; Lampis, J. Occupational stress, job satisfaction and physical health in teachers. European Review of Applied Psychology 2016, 66(2), 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothmann, S.; Barkhuizen, N. Job satisfaction, occupational stress, burnout, and work engagement as components of work-related wellbeing. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology 2008, 34(3), 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology 2006, 43(6), 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2007, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Motivated for teaching? Associations with school goal structure, teacher self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education 2017, 67, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tytherleigh, M.Y.; Webb, C.; Cooper, C.L.; Ricketts, C. Occupational stress in UK higher education institutions: A comparative study of all staff categories. Higher Education Research & Development 2005, 24(1), 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R.M. Teacher turnover, teacher shortages, and the organization of schools. American Educational Research Journal 2001, 38(3), 499–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadyiwa, M.; Kagura, J.; Stewart, A. Application of machine learning in the prediction of employee satisfaction with support provided in a national park. In Tourism and hospitality for sustainable development; Ndhlovu, E., Dube, K., Makuyana, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Business Management Department, Girne American University, North Cyprus Via Mersin 10, Kyrenia 99320, Turkey; Faculty of Business and Economics, Girne American University, North Cyprus Via Mersin 10, Kyrenia 99320, Turkey; Faculty of Business and Economics, Centre for Management Research, Girne American University, North Cyprus, Via Mersin 10, Kyrenia 99428, Turkey. Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14(6), 490.

- Holgado-Apaza, L.A.; Carpio-Vargas, E.E.; Calderon-Vilca, H.D.; Maquera-Ramirez, J.; Ulloa-Gallardo, N.J.; Acosta-Navarrete, M.S.; Barrón-Adame, J.M.; Quispe-Layme, M.; Hidalgo-Pozzi, R.; Valles-Coral, M. Modeling job satisfaction of Peruvian basic education teachers using machine learning techniques. Applied Sciences 2023, 13(6), 3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.-N.; Win, T.T.; Kim, H.-S.; Pae, A.; Att, W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Lee, D.-H. Deep learning and explainable artificial intelligence for investigating dental professionals’ satisfaction with CAD software performance. Journal of Prosthodontics 2024, 14(6), 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinniah, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Mamun, A. Sinniah; Mamun, A. Modeling the significance of motivation on job satisfaction and performance among the academicians: The use of hybrid structural equation modeling-artificial neural network analysis. Journal of Business Research 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Golande, A.; Surwase, V.; Patil, N.; Bhandekar, J.; Shinde, J. Envisaging college personnel turnover using machine learning and ensemble learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT); 2024; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kebede, A.G.; Fikire, A.H. Demographic and job satisfaction variables influencing academic staffs’ turnover intention in Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia. Cogent Business & Management 2022, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ahumada-Tello E, Ramos K. Reality or utopia? The happiness of university academics in their professional performance: evidence from an emerging country (Mexico). Management Decision 25, 62, 403–25. [Google Scholar]

- Asad Ali Khan, Shamsul Arfin Qasmi, Muhammad Abid, Khushk IA. Factors influencing faculty job satisfaction: a quantitative study of private medical colleges in Karachi. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector PE, Jex SM. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale, Organizational Constraints Scale, Quantitative Workload Inventory, and Physical Symptoms Inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1998, 3, 356–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design 1979.

- Arias-Flores H, Guadalupe-Lanas J, Pérez-Vega D, Artola-Jarrín V, Cruz-Cárdenas J. Emotional State of Teachers and University Administrative Staff in the Return to Face-to-Face Mode. Behavioral Sciences 2022, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi M, Yamano M, Matoba S. Prediction of well-being and insight into work-life integration among physicians using machine learning approach. PLOS ONE 2021, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Hammoudi Halat D, Soltani A, Dalli R, Alsarraj L, Malki A. Understanding and Fostering Mental Health and Well-Being among University Faculty: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao J, Dai T, Dong H, Chen J, Fan Y. Research on the mechanism of academic stress on occupational burnout in Chinese universities. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Mudrak J, Zabrodska K, Kveton P, Jelinek M, Blatny M, Solcova I, et al. Occupational Well-being Among University Faculty: A Job Demands-Resources Model. Research in Higher Education 2017, 59, 325–48. [Google Scholar]

- Colla CN, Andriollo DB, Cielo CA. Self-assessment of teachers with normal larynges and vocal and osteomuscular complaints. Journal of Voice 2024, 38, 1253.e1–1253.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurumendi España, I.E.; Panunzio, A.P.; Calle Gómez, M.A.; Borja Santillán, M.A. Síndrome burnout en docentes universitarios. RECIMUNDO 2021, 5, 205–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzuriaga Jaramillo, H.A.; Espinosa Pinos, C.A.; Haro Sarango, A.F.; Ortiz Román, H.D. Histograma y distribución normal: Shapiro-Wilk y Kolmogorov Smirnov aplicado en SPSS. LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Pinos, C.A.; Acuña-Mayorga, J.M.; Acosta-Pérez, P.B.; Lara-Álvarez, P. Ordinal Logistic Regression Model for Predicting Employee Satisfaction from Organizational Climate. 2023 IEEE Seventh Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ECTM); 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Feng, Y.; Jeong, S.P. Developing an advanced prediction model for new employee turnover intention utilizing machine learning techniques. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-Pérez, P.B.; Espinosa-Pinos, C.A.; Acuña-Mayorga, J.M.; Lascano-Arias, G. Occupational Risks: A Comparative Study of the Most Common Indicators in Uruguay, Cuba and Ecuador. 2023 IEEE Seventh Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ECTM); 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Rustam, F.; Ashraf, I.; Shafique, R.; Mehmood, A.; Ullah, S.; Sang Choi, G. Review prognosis system to predict employees job satisfaction using deep neural network. Computational Intelligence 2021, 37, 924–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado-Apaza, L.A.; Carpio-Vargas, E.E.; Calderon-Vilca, H.D.; Maquera-Ramirez, J.; Ulloa-Gallardo, N.J.; Acosta-Navarrete, M.S.; et al. Modeling Job Satisfaction of Peruvian Basic Education Teachers Using Machine Learning Techniques. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R.; Wolniak, R. Job Satisfaction and Problems among Academic Staff in Higher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predictive models for Employee satisfaction and retention in HR using Machine learning. Journal of Informatics Education and Research 2024.

- Hong, W.-C.; Pai, P.-F.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Yang, S.-L. Application of Support Vector Machines in Predicting Employee Turnover Based on Job Performance. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 2005; pp. 668–674. [Google Scholar]

- Maqsood, A.; Gul, S.; Noureen, N.; Yaswi, A. Dynamics of Perceived Stress, Stress Appraisal, and Coping Strategies in an Evolving Educational Landscape. Behavioral Sciences 2024, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj Kumar, G.V.; Chawla, B.A.; Rao, K.N.; Sita Ratnam, G. Emotional Labour and Perceived Stress at Workplace—HR Analytics. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Barigala, V.K.; PJ; S; P; SK; Ganapathy, N.; PA; K; Kumar, D.; Agastinose Ronickom, J.F. Evaluating the effectiveness of machine learning in identifying the optimal facial electromyography location for emotion detection. In Biomedical Signal Processing and Control; Elsevier BV, 2025; Vol. 100, p. 107012. [Google Scholar]

- Boser, B.E.; Guyon, I.M.; Vapnik, V.N. A training algorithm for optimal margin classifiers. In Proceedings of the fifth annual workshop on Computational learning theory, COLT92: 5th Annual Workshop on Computational Learning Theory; 1992; pp. 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Seok, B.W.; Wee K hoan Park J young Anil Kumar, D.; Reddy, N.S. Modeling the teacher job satisfaction by artificial neural networks. Soft Computing 2021, 25, 11803–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Taylor, J. Statistical Learning. Springer Texts in Statistics 2023, 15–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cranmer, S.J.; Desmarais, B.A. What Can We Learn from Predictive Modeling? Political Analysis 2017, 25, 145–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouval, R.; Bondi, O.; Mishan, H.; Shimoni, A.; Unger, R.; Nagler, A. Application of machine learning algorithms for clinical predictive modeling: a data-mining approach in SCT. Bone Marrow Transplantation 2013, 49, 332–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, F.; Yin, Y. Applying logistic LASSO regression for the diagnosis of atypical Crohn’s disease. Scientific Reports 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; WStevens, G.; SMichel, J.; Zimmerman, L. Workaholism among Leaders: Implications for Their Own and Their Followers’ Well-Being. Research in Occupational Stress and Well-being. 2016; 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A Critical Review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health. Bridging Occupational 2013, 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; You, X. Personal Resources Influence Job Demands, Resources, and Burnout: A One-year, Three-wave Longitudinal Study. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal 2016, 44, 247–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P. The Psychology of Work Engagement; Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciencia Digital. Editorial Ciencia, Digital; 2018, 2. Ciencia Digital. Editorial Ciencia Digital. 2018; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary, S. Exploring school principle’s practices in developing teacher leaders in their school. Social Sciences & Humanities Open 2021, 4, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, C.Z.; Alonzo, D.; Ei, W.Y.; Marynowski, R. Assessment practices of teachers in Myanmar: Are we there yet? Teaching and Teacher Education 2024, 145, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinniah, S.; Al Mamun, A.; Md Salleh, M.F.; Makhbul, Z.K.M.; Hayat, N. Modeling the Significance of Motivation on Job Satisfaction and Performance Among the Academicians: The Use of Hybrid Structural Equation Modeling-Artificial Neural Network Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, I.S.; Verkuilen, J.; Bianchi, R. Inquiry into the correlation between burnout and depression. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2019, 24, 603–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, B.W.; Wee, K.H.; Park, J.Y.; Anil Kumar, D.; Reddy, N.S. Modeling the teacher job satisfaction by artificial neural networks. Soft Computing 2021, 25, 11803–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon S, Simmons L, Liu F. Predicting Tech Employee Job Satisfaction Using Machine Learning Techniques Sumali J. Conlon1 Lakisha L. Simmons2 Feng Liu3. International Journal Of Management & Information Technology 2021, 16, 97–113.

- Fallucchi, F.; Coladangelo, M.; Giuliano, R.; William De Luca, E. Predicting Employee Attrition Using Machine Learning Techniques. Computers 2020, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabais, A.R.; Chambel, M.J.; Carvalho, V.S. Unravelling Time in Higher Education: Exploring the Mediating Role of Psychological Capital in Burnout and Academic Engagement. Education Sciences 2024, 14, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancoko, S.; Yuliawan, R.; Al Aufa, B.; Yuliyanto, H. The effects of job satisfaction on lecturer performance : case study in faculty x Universitas Indonesia. Jurnal Pendidikan Teknologi dan Kejuruan 2023, 29, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartol, A.; Üztemur, S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Şahin, D. Exploring the interplay of emotional intelligence, psychological resilience, perceived stress, and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study in the Turkish context. BMC Psychology 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Variable | Label |

|---|---|---|

| Numeric | HIJOS | From 0 to 4 children. |

| Numeric | EDAD | Age 1 is 16 to 24 years; 2 is 25 to 34 years; 3 is 35 to 43 years; 4 is 44 to 52 years; 5 is 53 years and older. |

| Numeric | Antig | Length of service, 1 is 0 to 2 years, 2 is 3 to 10 years, 3 is 11 to 20 years, 4 is 21 years or more. |

| Categoric | Uni | University to which the surveyed university professor belongs, options A,B,C,D. |

| Categoric | Prov | Represents a province of Ecuador of the university teacher surveyed in the university where he/she works options A,B,C,D. |

| Categoric | Ciu | City where the teacher works |

| Categoric | Ecivil | Marital status can be, Single, Divorced, Married, Widowed, Common-law, of the university professor. |

| Categoric | Ninst | Level of education, 1 is Postdoctorate, 2 is Ph.D., 3 is Master’s, 5 is Specialist, 6, 8 is medical specialist, 9 is other. of the respondent at university A,B,C,D. |

| Categoric | ETNIA | Ethnicity with the options: Mes-tizo/a; Indígena; Afro; Blan-co/a; Montubio/a. of the respondent in the university A,B,C,D. |

| Categoric | GEN | Male, female, other. of the survey in university A,B,C,D. |

| Categoric | Ccon | Field of knowledge, where 1 is Natural Sciences; 2 is Engineering and Technology; 3 is Medical and Health Sciences; 4 is Agricultural Sciences; 5 is Social Sciences; 6 is Humanities; 7 is Education; 8 is Communication and Information Sciences. of respondent at university A,B,C,D |

| Categoric | TcLAB | It is the type of contract, 1 is appointment; 2 is indefinite contract, 3 is occasional public contract, 4 is occasional private contract. of the unit A,B,C,D. |

| Categoric | PUNnDL | Represents the labor attrition. 1 is Low; 2 is Moderate; 3 is High. of the respondent at university A,B,C,D |

| Categoric | PUNnEP | Represents perceived stress. 1 is Low Stress; 2 is Moderate Stress; 3 is High Stress, 4 is High Stress. of the respondent in the university A,B,C,D |

| Categoric | PUNnSL1 | Represents job satisfaction. 1 is High Dissatisfaction; 2 is Moderate Dissatisfaction; 3 is Moderate Satisfaction, 4 is Moderate High Satisfaction, 5 is High Satisfaction. of the survey at the university A,B,C,D |

| Categoric | PUNnRL | Represents job satisfaction. 1 is High Dissatisfaction; 2 is Moderate Dissatisfaction; 3 is Moderate Satisfaction, 4 is Moderate High Satisfaction, 5 is High Satisfaction. of the survey at the university A,B,C,D |

| Var | Cat | Frec | % | Var | Cat | Frec | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universidad | A | 396 | 24.6 | Etnia | Indígena | 0.0189 | 0.0302 |

| B | 402 | 25.0 | Afro | 0.0183 | 0.0293 | ||

| C | 417 | 25.9 | Blanco/a | 0.1767 | 0.1726 | ||

| D | 385 | 24.0 | Mestizo/a | 0.2067 | 0.1983 | ||

| Provincia | A | 418 | 26.0 | Montubio/a | 0.8363 | 0.8130 | |

| B | 366 | 22.8 | Género | Femenino | 758 | 47.4 | |

| C | 424 | 26.4 | Masculino | 793 | 49.6 | ||

| D | 392 | 24.4 | Otro | 49 | 3.0 | ||

| Ciudad | A | 370 | 23.0 | Hijos | Media | 1.969 | - |

| B | 433 | 26.9 | Edad | Media | 3.004 | - | |

| C | 385 | 23.9 | Ccon | 3 | 217 | 13.5 | |

| D | 412 | 25.6 | 2 | 207 | 12.9 | ||

| Estado Civil | Casado/a | 293 | 18.2 | 4 | 207 | 12.9 | |

| Unión de Hecho | 309 | 19.2 | 1 | 204 | 12.7 | ||

| Divorciado/a | 350 | 21.8 | 6 | 200 | 12.4 | ||

| Soltero/a | 329 | 20.4 | 8 | 200 | 12.4 | ||

| Viudo/a | 319 | 19.8 | Otros | 365 | 22.7 | ||

| Instrucción | 1 | 225 | 14.0 | PUNnRL | Media | 2.029 | - |

| 2 | 205 | 12.7 | TcLAB | 1 | 403 | 25.0 | |

| 3 | 235 | 14.6 | 2 | 374 | 23.3 | ||

| 5 | 235 | 14.6 | 3 | 415 | 25.8 | ||

| 6 | 212 | 13.2 | 4 | 408 | 25.4 | ||

| 8 | 225 | 14.0 | Antig | Media | 2.536 | - | |

| 9 | 263 | 16.3 | PUNnDL | Media | 2.007 | ||

| PUNnSL | Media | 2.231 | - | PUNnEP | Media | 2.491 | - |

| Method | Accuracy | 95% CI | No Information rate (Tasa de No-Information) | P-Value [Acc > NIR] | Kappa | Mcnemar’s Test P-Value | AUC Score | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regresión logística multinomial | 42.42% | (0.3803, 0.4691) | 20% | P < 2e-16 | 0.2803 | 0.06781 | 0.79975 | 0.416892 | 0.424242 | 0.418694 |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | 49.49% | (0.45, 0.5399) | 20% | P < 2.2e-16 | 0.3687 | 4.001e-15 | 0.686868 | 0.448025 | 0.498989 | 0.458717 |

| Naive Bayes | 25.86% | (0.2205, 0.2995) | 20% | P < 0.000931 | 0.0732 | P < 2.2e-16 | 0.536616 | 0.251783 | 0.258585 | 0.192793 |

| Árbol de Decisión | 0.5778 | (0.5329, 0.6217) | 20% | P < 2.2e-16 | 0.4722 | NA | 0.846015 | 0.578933 | 0.577777 | 0.577813 |

| Modelo de Máquina de Vectores de Soporte SVN | 58.38% | (0.539, 0.6277) | 20% | P<2.2e-16 | 0.4798 | NA | 0.847515 | 0.588130 | 0.583838 | 0.584808 |

| Regresión Logística Ordinal | 33.25% | (0.3094, 0.3562) | 0.3119 | P<0.0403 | 0.0475 | NA | 0.523898 | 0.345042 | 0.332500 | 0.308198 |

| Red Neuronal Artificial | 74.84% | (0.7068, 0.7869) | 0.5053 | P < 2.2e-16 | 0.6229 | NA | 0.929890 | 0.730435 | 0.748414 | 0.724373 |

| Clasificación Ordinal mediante Random Forest | 62.02% | (0.5758, 0.6631) | 0.2 | P < 2.2e-16 | 0.5253 | NA | 0.855100 | 0.615891 | 0.620202 | 0.617414 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).