Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Treatments

Sampling Methodology

2.2. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence

2.3. Chlorophyll and Carotenoids Content

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

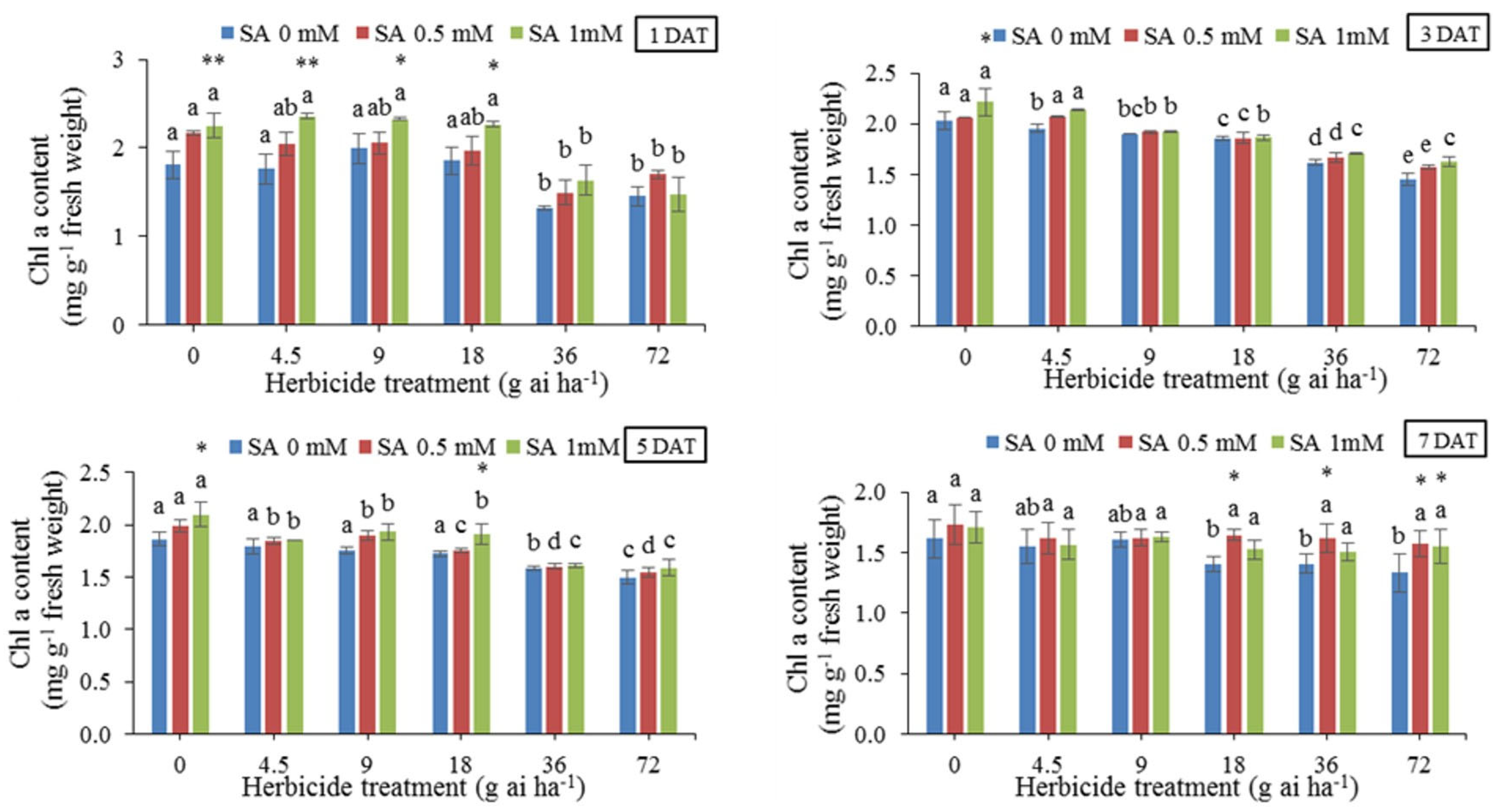

3.1. Chlorophyll a Content

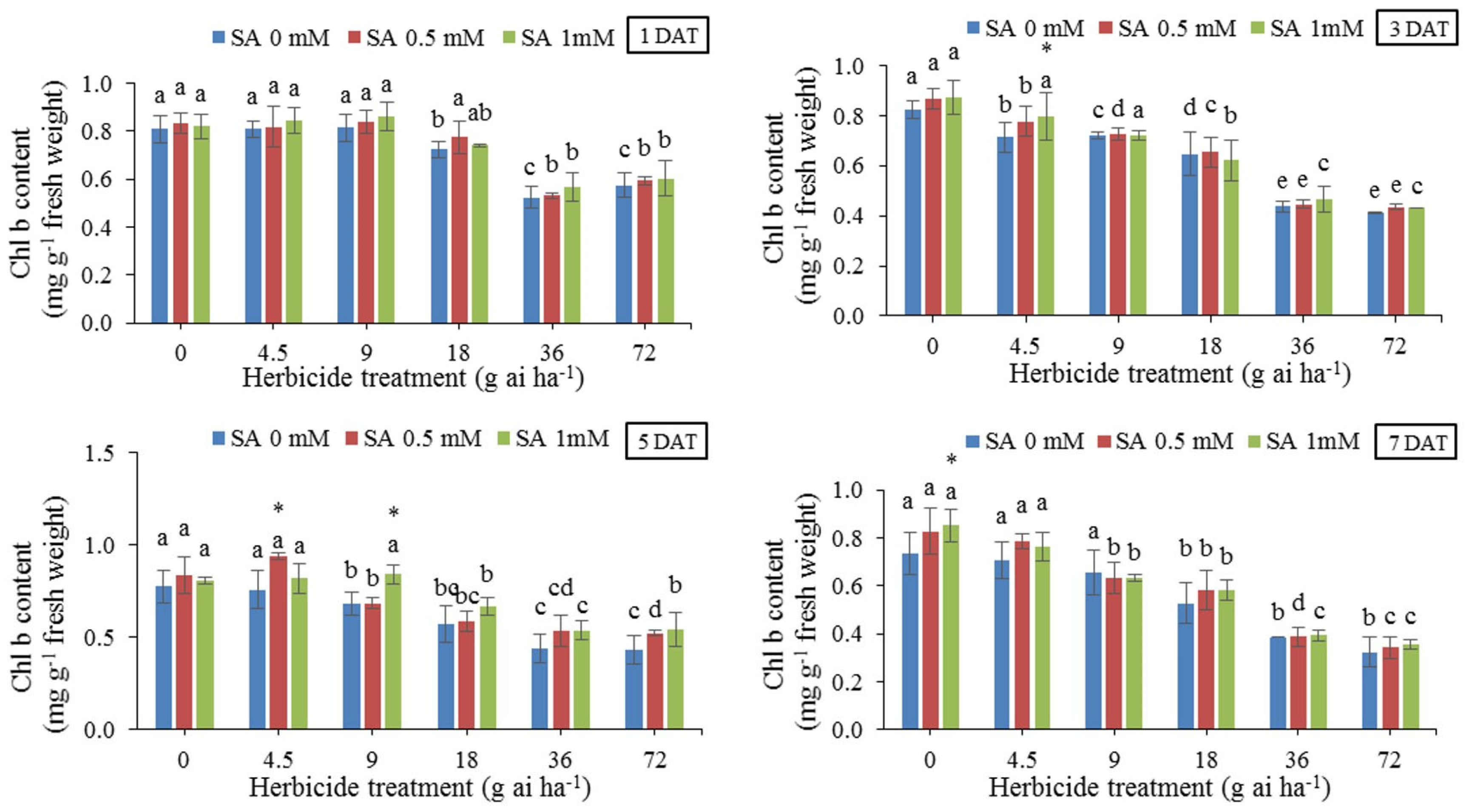

3.2. Chlorophyll b Content

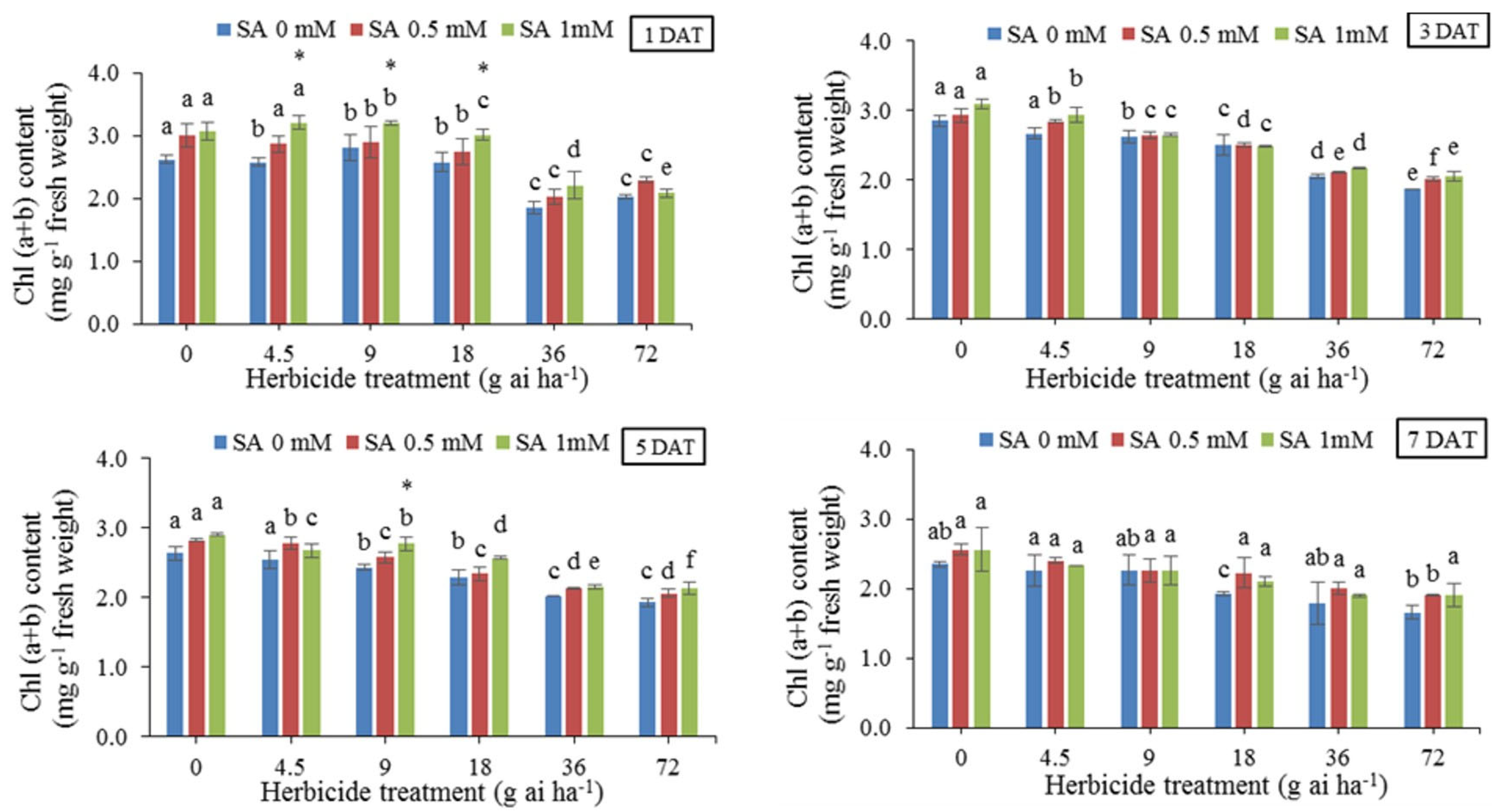

3.3. Total Chlorophyll

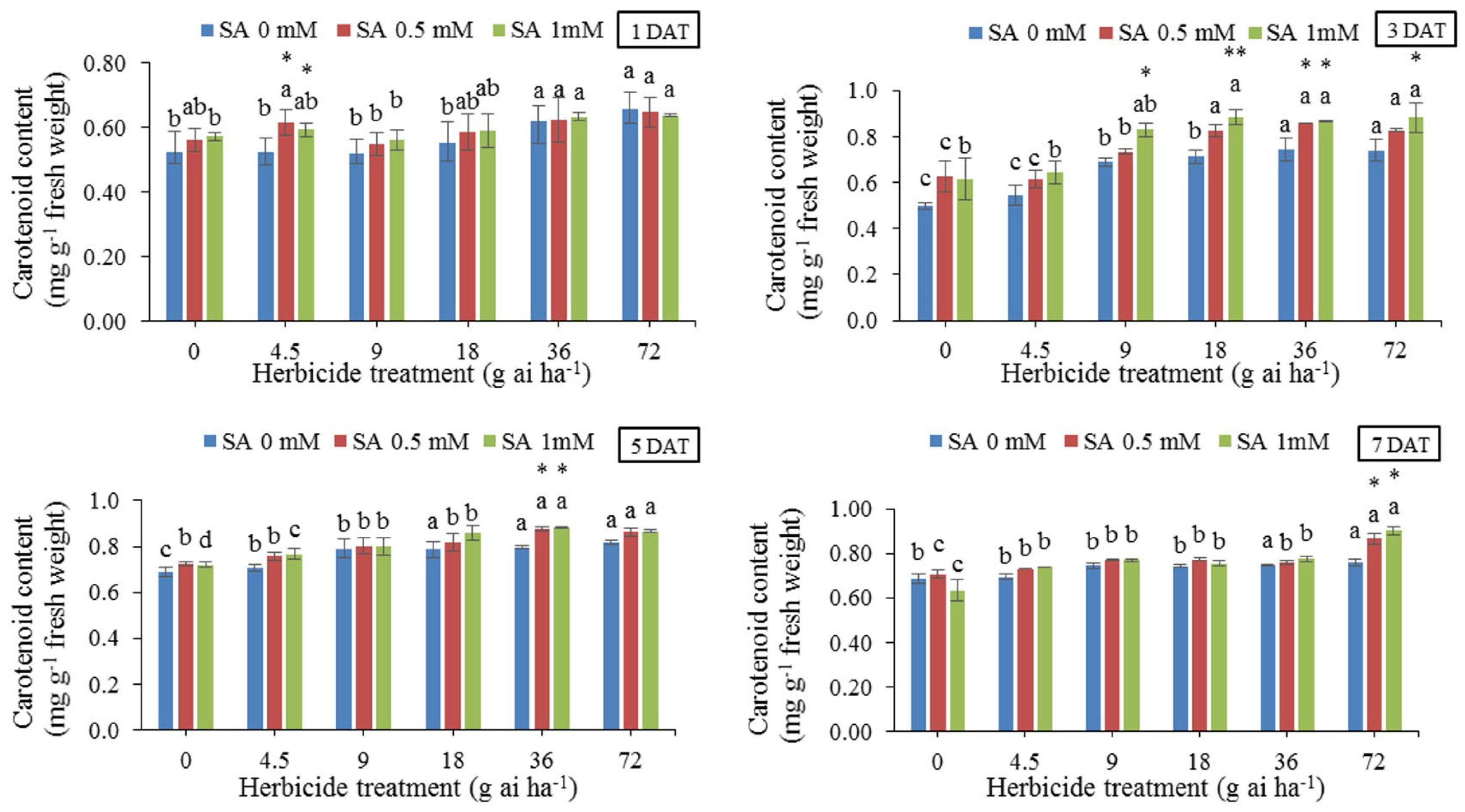

3.4. Carotenoid Content

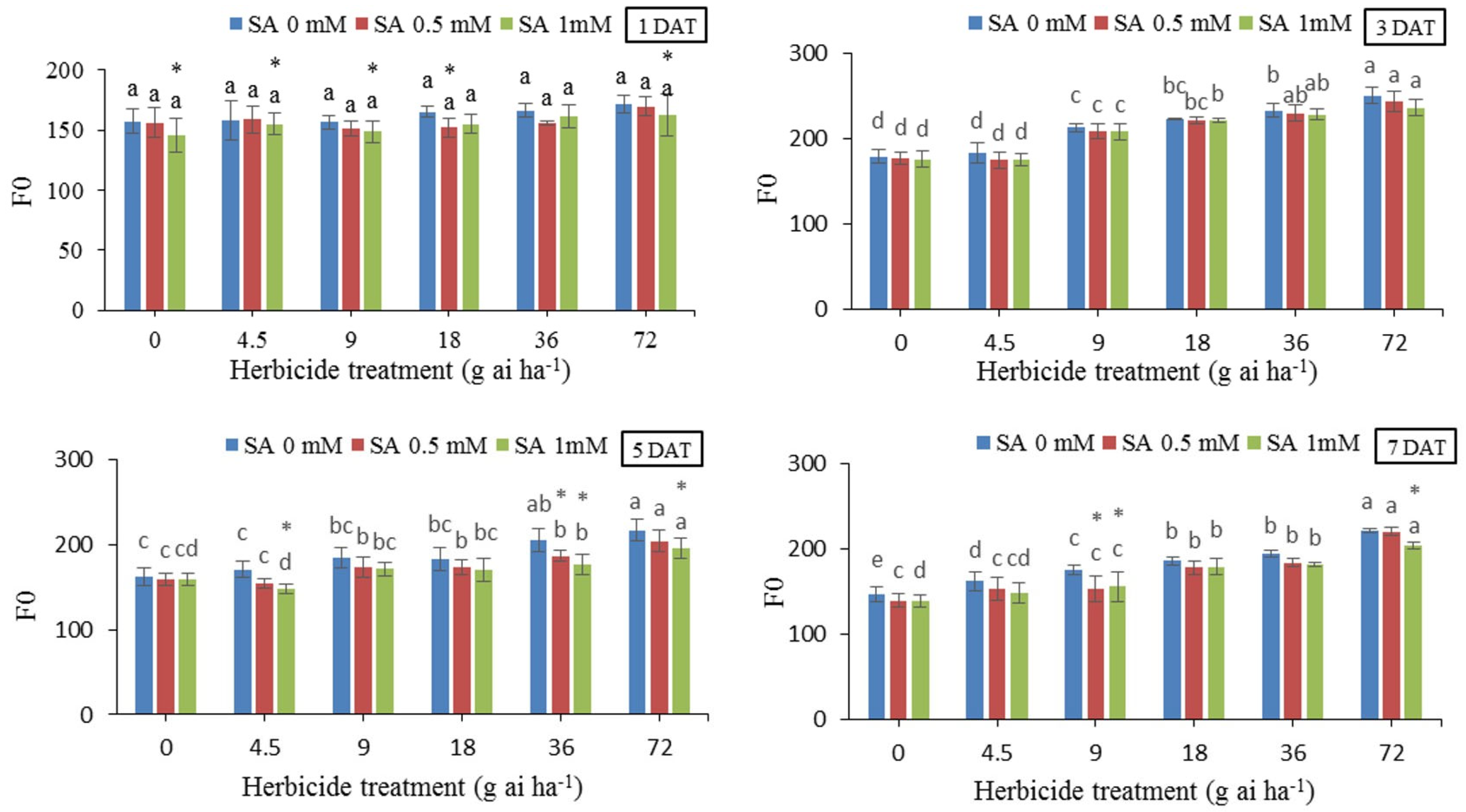

3.5. Minimal Fluorescence (Fo)

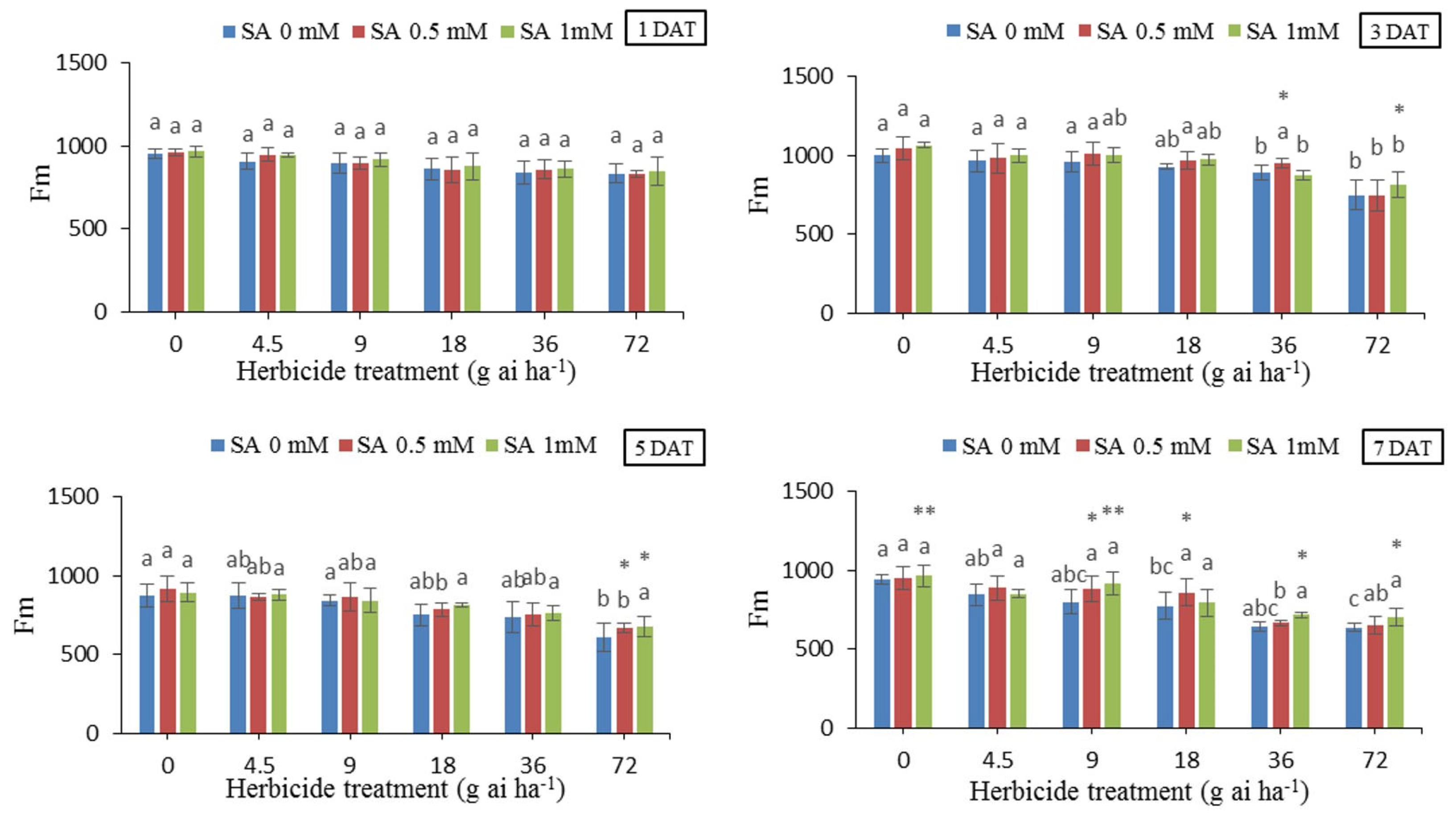

3.6. Maximal Fluorescence (Fm)

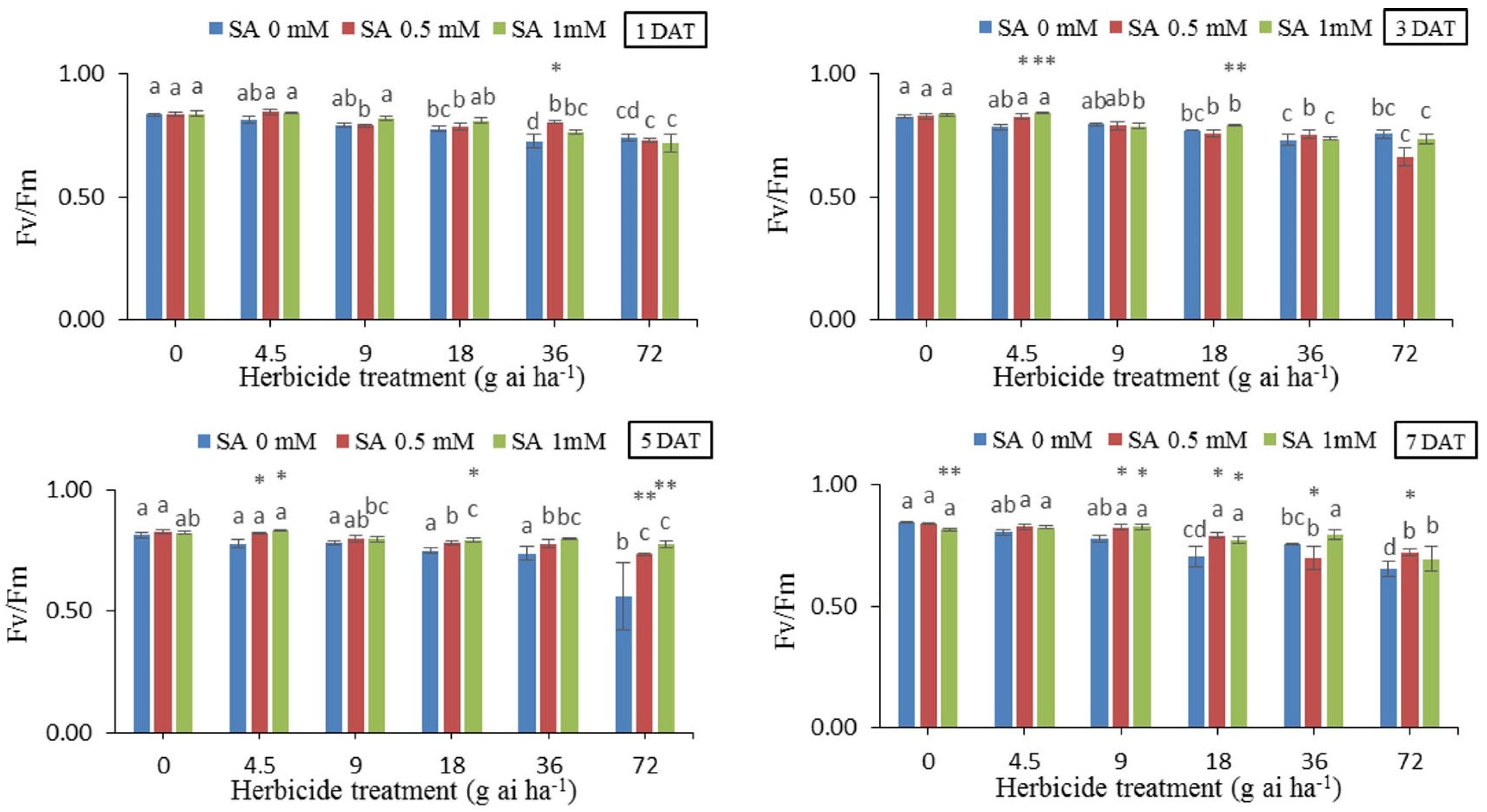

3.7. Quantum Performance (Fv/Fm)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shewry, P.R.; Hey, S.J. The Contribution of Wheat to Human Diet and Health. Food Energy Secur. 2015, 4, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, S.H.; Saleem, M.; Maqsood, M.M.; Mujahid, M.Y.; ul Hassan, M.; Saleem, R. Weed density and grain yield of wheat as affected by spatial arrangements and weeding techniques under rainfed conditions of pothowar. J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 46, 242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.M.; Begum, M. Soil Weed Seed Bank: Importance and Management for Sustainable Crop Production—A Review. J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ. 2015, 13, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayana, B. Wheat Production as Affected by Weed Diversity and Other Crop Management Practices in Ethiopia. International J. Res. Stud. Agric. Sci. (IJRSAS) 2020, 6, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakka, S.; Jugulam, M.; Peterson, D.; Asif, M. Herbicide Resistance: Development of Wheat Production Systems and Current Status of Resistant Weeds in Wheat Cropping Systems. Crop J. 2019, 7, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, S.K.; Gill, R.K.; Virk, H.K.; Bhardwag, R.D. Effect of Herbicide Stress on Synchronization of Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism in Lentil (Lens Culinaris Medik.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 196, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, S.; Alebrahim, M.; Weed, R. The Effect of Rimsulfuron Application Time and Dose on Weed Control and Potato (Solanum Tuberosum) Tuber Yield. Iran. J. weed Sci. 2017, 12, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova, D.; Aleksandrov, V.; Anev, S.; Sergiev, I. Photosynthesis Alterations in Wheat Plants Induced by Herbicide, Soil Drought or Flooding. Agronomy 2022, 12, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathika, S.; Udhaya, A.; Ramesh, T.; Shanmugapriya, P. Weed Management Strategies in Green Gram: A Review. The Pharma Innov. Journal 2023, 12, 5574–5580. [Google Scholar]

- Alebrahim, M.T.; Kalkhoran, E.S.; Majd, R.; Khatami, S.A. Effects of Adjuvants on the Effectiveness and Rainfastness of Rimsulfuron in Potato. Hell. Plant Prot. J. 2023, 17, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.M. Review of Glyphosate and ALS-Inhibiting Herbicide Crop Resistance and Resistant Weed Management. Weed Technol. 2007, 21, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranel, P.; Wright, T. Resistance of Weeds to ALS-Inhibiting Herbicides: What Have We Learned? Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K. Action Mechanisms of Acetolactate Synthase-Inhibiting Herbicides. Pest Biochem. Physiol 2007, 89, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Wang, R.; Hu, H.; Lu, T.; Chen, X.; Ye, H.; Liu, W.; Fu, Z. Enantioselective Phytotoxicity of the Herbicide Imazethapyr and Its Effect on Rice Physiology and Gene Transcription. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7036–7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Q.; Yu, C.Y.; Dong, J.G.; Hu, S.W.; Xu, A.X. Acetolactate Synthase-Inhibiting Gametocide Amidosulfuron Causes Chloroplast Destruction, Tissue Autophagy, and Elevation of Ethylene Release in Rapeseed. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 280179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, D.; Pathange, P.; Chung, J.S.; Jiang, J.; Gao, L.; Oikawa, A.; Hirai, M.Y.; Saito, K.; Pare, P.W.; Shi, H. A Stress-inducible Sulphotransferase Sulphonates Salicylic Acid and Confers Pathogen Resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant, Cell & Environment 2010, 33, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Chen, S.; Jin, Y.; Song, H.; Ruan, S.; Fu, Z.; Asad, M.A.U.; Qian, H. Effects of the Herbicide Imazethapyr on Photosynthesis in PGR5- and NDH-Deficient Arabidopsis Thaliana at the Biochemical, Transcriptomic, and Proteomic Levels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 4497–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayez, K.A. Action of Photosynthetic Diuron Herbicide on Cell Organelles and Biochemical Constituents of the Leaves of Two Soybean Cultivars. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2000, 66, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caverzan, A.; Piasecki, C.; Chavarria, G.; Stewart, C.N.; Vargas, L. Defenses Against ROS in Crops and Weeds: The Effects of Interference and Herbicides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Reactive Species and Antioxidants. Redox Biology Is a Fundamental Theme of Aerobic Life. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.G.; Teicher, H.B.; Streibig, J.C. Linking Fluorescence Induction Curve and Biomass in Herbicide Screening. Pest Manag. Sci. 2003, 59, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, L.W.; Dahllöf, I. Direct and Indirect Effects of the Herbicides Glyphosate, Bentazone and MCPA on Eelgrass (Zostera Marina). Aquatic Toxicol. 2007, 82, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottardini, E.; Cristofori, A.; Cristofolini, F.; Nali, C.; Pellegrini, E.; Bussotti, F.; Ferretti, M. Chlorophyll-Related Indicators Are Linked to Visible Ozone Symptoms: Evidence from a Field Study on Native Viburnum Lantana L. Plants in Northern Italy. Ecological Indic. 2014, 39, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneau, P.; Qiu, B.; Deblois, C.P. Use of Chlorophyll Fluorescence as a Tool for Determination of Herbicide Toxic Effect: Review. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2007, 89, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Xu, W.; He, X.; Wang, J. The Feasibility of Fv/Fm on Judging Nutrient Limitation of Marine Algae through Indoor Simulation and in Situ Experiment. Estuarine, Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaji, H.M.; Schansker, G.; Brestic, M.; Bussotti, F.; Calatayud, A.; Ferroni, L.; Goltsev, V.; Guidi, L.; Jajoo, A.; Li, P.; et al. Frequently Asked Questions about Chlorophyll Fluorescence, the Sequel. Photosynth. Res. 2016, 132, 13–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Y.I.; Menegat, A.; Gerhards, R. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Imaging: A New Method for Rapid Detection of Herbicide Resistance in Alopecurus Myosuroides. Weed Res. 2013, 53, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, F.E.; Zaccaro, M.L.D.M. Chlorophyll Fluorescence as a Marker for Herbicide Mechanisms of Action. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 102, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korres, N.E.; Froud-Williams, R.J.; Moss, S.R. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Technique as a Rapid Diagnostic Test of the Effects of the Photosynthetic Inhibitor Chlorotoluron on Two Winter Wheat Cultivars. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2003, 143, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Y.; Sami, F.; Siddiqui, H.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Salicylic Acid in Relation to Other Phytohormones in Plant: A Study towards Physiology and Signal Transduction under Challenging Environment. Environmental Exp. Bot. 2020, 175, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi-Golezani, K.; Solhi-Khajemarjan, R. Changes in Growth and Essential Oil Content of Dill (Anethum Graveolens) Organs under Drought Stress in Response to Salicylic Acid. J. Plant Physiol. Breeding 2021, 11, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wen, T.; Liu, M.; Yang, M.; Chen, X. Implications of Terminal Oxidase Function in Regulation of Salicylic Acid on Soybean Seedling Photosynthetic Performance under Water Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 112, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Guan, C.; Ji, J. Foliar Application of Salicylic Acid Alleviate the Cadmium Toxicity by Modulation the Reactive Oxygen Species in Potato. Ecotoxicology Environ. Safety 2019, 172, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janda, T.; Gondor, O.K.; Yordanova, R.; Szalai, G.; Pál, M. Salicylic Acid and Photosynthesis: Signalling and Effects. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2014, 36, 2537–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, H. Prometryne-Induced Oxidative Stress and Impact on Antioxidant Enzymes in Wheat. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2009, 72, 1687–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.H.; Le Yin, X.; Chen, G.F.; Yang, H. Biological Responses of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum) Plants to the Herbicide Chlorotoluron in Soils. Chemosphere 2007, 68, 1779–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wei, H.; Cui, L. Effects of Heat Acclimation Pretreatment on Changes of Membrane Lipid Peroxidation, Antioxidant Metabolites, and Ultrastructure of Chloroplasts in Two Cool-Season. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2006, 56, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, S.A.; Barmaki, M.; Alebrahim, M.T.; Bajwa, A.A. Salicylic Acid Pre-Treatment Reduces the Physiological Damage Caused by the Herbicide Mesosulfuron-Methyl+ Iodosulfuron-Methyl in Wheat (Triticum aestivum). Agronomy 2022, 12, 3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagallo, R.P.; Oxborough, K.; Pallett, K.E.; Baker, N.R. Rapid, Noninvasive Screening for Perturbations of Metabolism and Plant Growth Using Chlorophyll Fluorescence Imaging. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saja, D.; Rys, M.; Stawoska, I.; Skoczowski, A. Metabolic Response of Cornflower (Centaurea Cyanus L.) Exposed to Tribenuron-Methyl: One of the Active Substances of Sulfonylurea Herbicides. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Goto, M.; Hanai, M.; Shimizu, T.; Izawa, N.; Kanamoto, H.; Tomizawa, I.K.; Yokota, I.; Kobayashi, H. Tolerance to Herbicides by Mutated Acetolactate Synthase Genes Integrated into the Chloroplast Genome of Tobacco. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodoulou, F.L.; Clark, I.M.; He, X.L.; Pallett, K.E.; Cole, D.J.; Hallahan, D.L. Co-Induction of Glutathione-S-Transferases and Multidrug Resistance Associated Protein by Xenobiotics in Wheat. Pest Manag. Sci. 2003, 59, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatami, S.A.; Alebrahim, M.T.; Barmaki, M. Effect of Mesosulfuron Methyl + Iodosulfuron Methyl Herbicide in Combination with Salicylic Acid on Wild Oat (Avena Fatua). Iran. J. Weed Sci. 2023, 19, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fai, P.B.; Grant, A.; Reid, B. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence as a Biomarker for Rapid Toxicity Assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2007, 26, 1520–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riethmuller-Haage, I.; Bastiaans, L.; Kropff, M.J.; Harbinson, J.; Kempenaar, C. Can Photosynthesis-Related Parameters Be Used to Establish the Activity of Acetolactate Synthase–Inhibiting Herbicides on Weeds? Weed Sci. 2006, 54, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph Falqueto, A.; Alves da Silva Júnior, R.; Thiago Gaudio Gomes, M.; Paulo Rodrigues Martins, J.; Moura Silva, D.; Luiz Partelli, F. Effects of Drought Stress on Chlorophyll a Fluorescence in Two Rubber Tree Clones. Scientia Hortic. 2017, 224, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatev, Z. Drought-Induced Changes in Chlorophyll Fluorescence of Young Wheat Plants. Biotechnology Biotechnol. Equipment 2009, 23, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.L.; Morrison, M.J.; Voldeng, H.D. Leaf Greenness and Photosynthetic Rates in Soybean. Crop Sci. 1995, 35, 1411–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanova, D.A.; Paunov, M.; Goltsev, V.; Cuypers, A.; Vangronsveld, J.; Vassilev, A. Photosynthetic Performance of the Imidazolinone Resistant Sunflower Exposed to Single and Combined Treatment by the Herbicide Imazamox and an Amino Acid Extract. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, H.; Hassan, M.; Mohassel, R.; Parsa, M.; Bannayan-Aval, M.; Zand, E. Behavior of Sethoxydim Alone or in Combination with Turnip Oils on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameter. Notulae Sci. Biol. 2014, 6, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avarseji, Z.; Rashed Mohssel, M.H.; Nezami, A.; Abbaspoor, M.; Mahallati, M.N. Dicamba+ 2,4-D Affects the Shape of the Kautsky Curves in Wild Mustard (Sinapis Arvensis). Plant Knowl. Journal 2012, 1, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, G.; Eryilmaz, I.E.; Ozakca, D. The Effect of Aluminium-Stress and Exogenous Spermidine on Chlorophyll Degradation, Glutathione Reductase Activity and the Photosystem II D1 Protein Gene (PsbA) transcript level in lichen Xanthoria parietina. Elsevier. Phytochemistry 2014, 98, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaci, A.; Kaya, A.; Duman, S. Effects of Ascorbic Acid on Some Physiological Changes of Pepino (Solanum Muricatum Ait.) under Chilling Stress. Acta Biol. Hungarica 2014, 65, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alscher, R.G.; Erturk, N.; Heath, L.S. Role of Superoxide Dismutases (SODs) in Controlling Oxidative Stress in Plants. Journal Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Prithiviraj, B.; Smith, D.L. Photosynthetic Responses of Corn and Soybean to Foliar Application of Salicylates. J. plant physiol. 2003, 160, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodary, S.E.A. Effect of Salicylic Acid on the Growth, Photosynthesis and Carbohydrate Metabolism in Salt Stressed Maize Plants. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2004, 6, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sakuraba, Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.S.; Hörtensteiner, S.; Paek, N.C. Arabidopsis Staygreen-Like (SGRL) Promotes Abiotic Stress-Induced Leaf Yellowing during Vegetative Growth. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 3830–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A.; Yigit, E. The Physiological and Biochemical Effects of Salicylic Acid on Sunflowers (Helianthus Annuus) Exposed to Flurochloridone. Ecotoxicology Environ. Safety 2014, 106, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tayeb, M.A. Response of Barley Grains to the Interactive e. Ect of Salinity and Salicylic Acid. Plant Growth Regul. 2005, 45, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambussi, E.A.; Bartoli, C.G.; Beltrano, J.; Guiamet, J.J.; Araus, J.L. Oxidative Damage to Thylakoid Proteins in Water-Stressed Leaves of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum). Physiol. Plant. 2000, 108, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candan, N.; Tarhan, L. Changes in Chlorophyll-Carotenoid Contents, Antioxidant Enzyme Activities and Lipid Peroxidation Levels in Zn-Stressed Mentha Pulegium. Turkish J. Chem. 2003, 27, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Duan, B.; Korpelainen, H.; Li, C. Effect of Drought and ABA on Growth, Photosynthesis and Antioxidant System of Cotinus Coggygria Seedlings under Two Different Light Conditions. Environmental Exp. Bot. 2011, 71, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrtash, M.; Mohsenzadeh, S.; Mohabatkar, H. Salicylic Acid Alleviates Paraquat Oxidative Damage in maize seedling. Asian J. Exp. Biol. Sci. 2011, 2, 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Ananieva, E.A.; Alexieva, V.S.; Popova, L.P. Treatment with Salicylic Acid Decreases the Effects of Paraquat on Photosynthesis. J. Plant Physiol. 2002, 159, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Singh, N.B.; Singh, A.; Hussain, I.; Yadav, V. Physiological and Biochemical Effects of Salicylic Acid on Pisum Sativum Exposed to Isoproturon. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2016, 62, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).