Submitted:

09 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

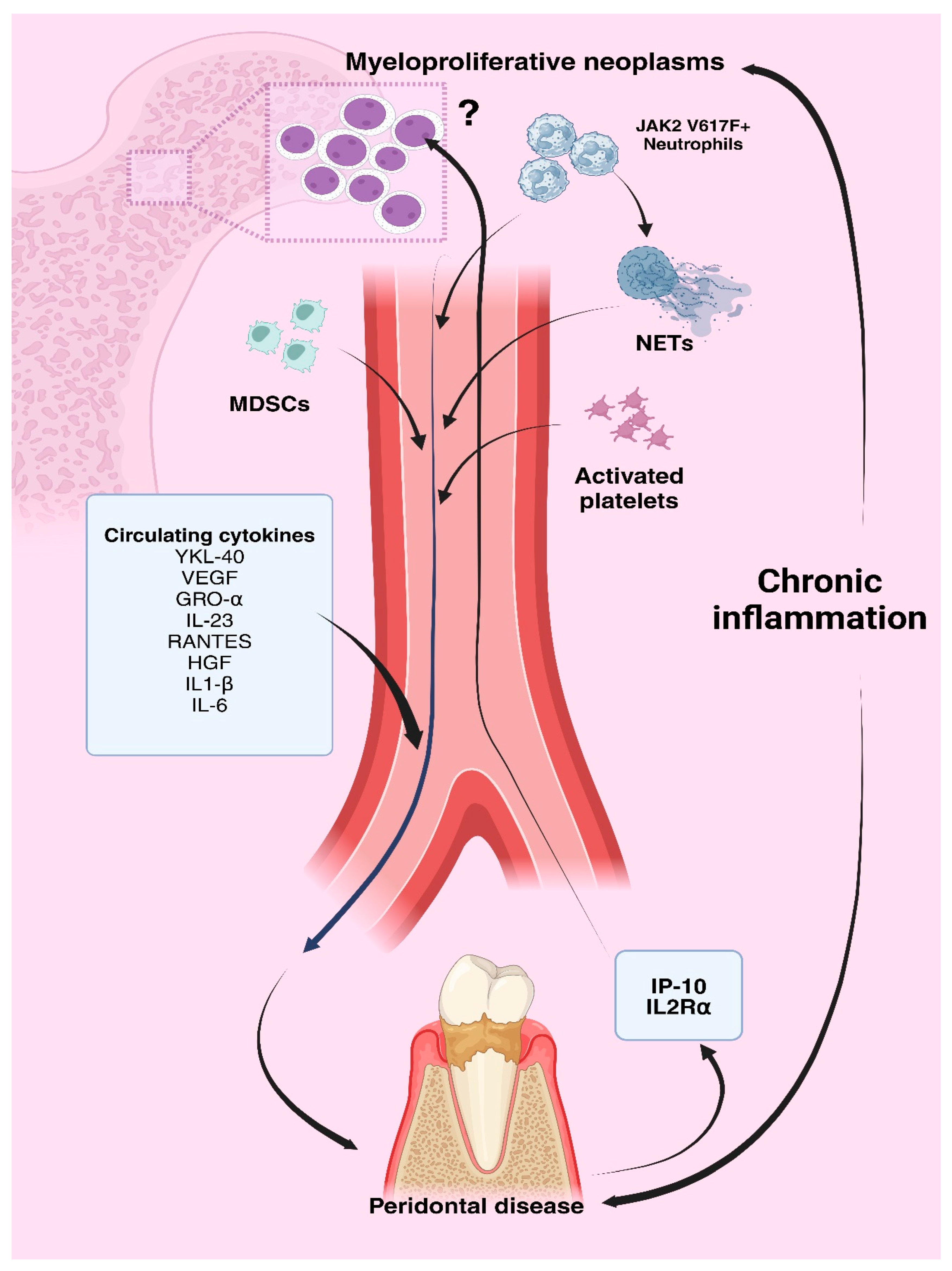

1. Introduction

2. Dysregulation of Inflammatory Cytokines in MPNs and Cytokine Pattern

3. Inflammatory Origin of the PD

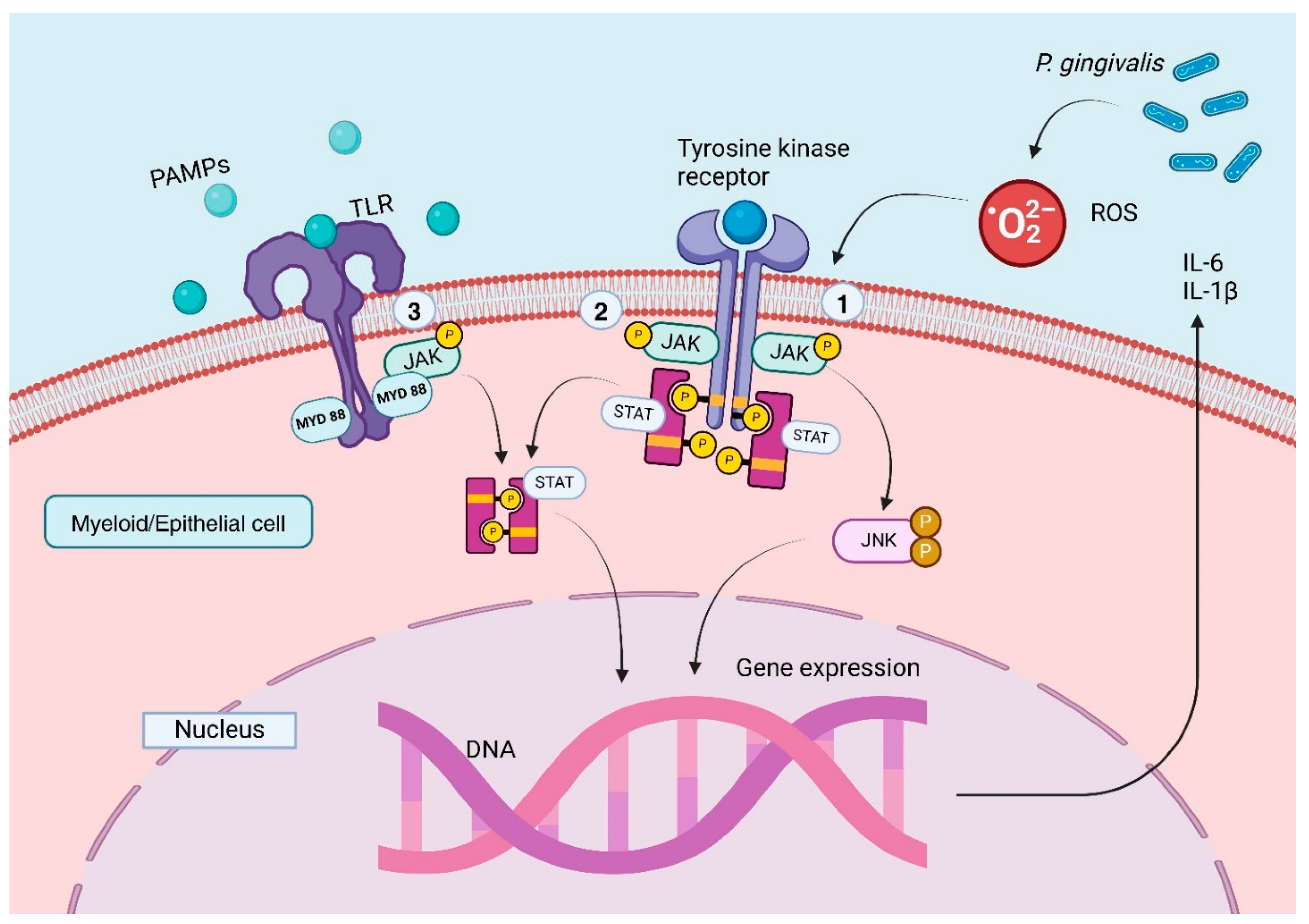

4. Pathogen-Induced Inflammation Through JAK/STAT Signaling in PD

5. Circulating Cells and Periodontal Disease

6. Common Circulating Inflammatory Mediators in MPNs and Periodontal Disease

7. The Bidirectional Impact of Periodontal Disease and Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kinane, D.F.; Stathopoulou, P.G.; Papapanou, P.N. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primer 2017, 3, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihlstrom, B.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Johnson, N.W. Periodontal diseases. The Lancet 2005, 366, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highfield, J. Diagnosis and classification of periodontal disease. Aust Dent J 2009, 54. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01140.x (accessed on 7 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.C.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Clin Periodontol 2018, 45. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jcpe.12935 (accessed on 7 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, S.; Caton, J.G.; Albandar, J.M.; Bissada, N.F.; Bouchard, P.; Cortellini, P.; et al. Periodontal manifestations of systemic diseases and developmental and acquired conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 3 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol 2018, 45. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jcpe.12951 (accessed on 7 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smalley, J.W. Pathogenic Mechanisms in Periodontal Disease. Adv Dent Res 1994, 8, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zee, K. Smoking and periodontal disease. Aust Dent J 2009, 54. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01142.x (accessed on 7 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Borgnakke, W.S. Does Treatment of Periodontal Disease Influence Systemic Disease? Dent Clin North Am 2015, 59, 885–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefferi, A.; Guglielmelli, P.; Larson, D.R.; Finke, C.; Wassie, E.A.; Pieri, L.; et al. Long-term survival and blast transformation in molecularly annotated essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis. Blood 2014, 124, 2507–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yan, S.; Liu, N.; He, N.; Zhang, A.; Meng, S.; et al. Genetic polymorphisms and expression of NLRP3 inflammasome-related genes are associated with Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. Hum Immunol 2020, 81, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischman, A.G.; Aichberger, K.J.; Luty, S.B.; Bumm, T.G.; Petersen, C.L.; Doratotaj, S.; et al. TNFα facilitates clonal expansion of JAK2V617F positive cells in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2011, 118, 6392–6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øbro, N.F.; Grinfeld, J.; Belmonte, M.; Irvine, M.; Shepherd, M.S.; Rao, T.N.; et al. Longitudinal Cytokine Profiling Identifies GRO-α and EGF as Potential Biomarkers of Disease Progression in Essential Thrombocythemia. HemaSphere 2020, 4, e371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Gu, Y.; Lai, X.; Gu, Q. LIGHT is increased in patients with coronary disease and regulates inflammatory response and lipid metabolism in oxLDL-induced THP-1 macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 490, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromovsky, A.D.; Schugar, R.C.; Brown, A.L.; Helsley, R.N.; Burrows, A.C.; Ferguson, D.; et al. Δ-5 Fatty Acid Desaturase FADS1 Impacts Metabolic Disease by Balancing Proinflammatory and Proresolving Lipid Mediators. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2018, 38, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihăilă, R.G. Pragmatic Analysis of Dyslipidemia Involvement in Coronary Artery Disease: A Narrative Review. Curr Cardiol Rev 2020, 16, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todor, S.B.; Ichim, C.; Boicean, A.; Mihaila, R.G. Cardiovascular Risk in Philadelphia-Negative Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Mechanisms and Implications—A Narrative Review. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 8407–8423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Molinaro, R.; Sellar, R.S.; Ebert, B.L. Jak-ing Up the Plaque’s Lipid Core…and Even More. Circ Res 2018, 123, 1180–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Zhang, Y.; Grockowiak, E.; Kimmerlin, Q.; Hansen, N.; Stoll, C.B.; et al. IL-1β promotes MPN disease initiation by favoring early clonal expansion of JAK2-mutant hematopoietic stem cells. Blood Adv 2024, 8, 1234–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orjalo, A.V.; Bhaumik, D.; Gengler, B.K.; Scott, G.K.; Campisi, J. Cell surface-bound IL-1α is an upstream regulator of the senescence-associated IL-6/IL-8 cytokine network. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2009, 106, 17031–17036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arranz, L.; Arriero, M.D.M.; Villatoro, A. Interleukin-1β as emerging therapeutic target in hematological malignancies and potentially in their complications. Blood Rev 2017, 31, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolfi, R.; Di Gennaro, L. Pathophysiology of thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica 2011, 96, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacemiro, M.D.C.; Cominal, J.G.; Tognon, R.; Nunes, N.D.S.; Simões, B.P.; Figueiredo-Pontes, L.L.D.; et al. Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms as disorders marked by cytokine modulation. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther 2018, 40, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, O.; Hobbs, G.; Ravid, K.; Libby, P. Cardiovascular Disease in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. JACC CardioOncology 2022, 4, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.; Ocias, L.F.; Vestergaard, H.; Broesby-Olsen, S.; Hermann, A.P.; Frederiksen, H. Bone morbidity in chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. Expert Rev Hematol 2015, 8, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyfer, E.M.; Fleischman, A.G. Myeloproliferative neoplasms—blurring the lines between cancer and chronic inflammatory disorder. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1208089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermouet, S.; Vilaine, M. The JAK2 46/1 haplotype: a marker of inappropriate myelomonocytic response to cytokine stimulation, leading to increased risk of inflammation, myeloid neoplasm, and impaired defense against infection? Haematologica 2011, 96, 1575–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapper, W.; Jones, A.V.; Kralovics, R.; Harutyunyan, A.S.; Zoi, K.; Leung, W.; et al. Genetic variation at MECOM, TERT, JAK2 and HBS1L-MYB predisposes to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Fu, P.; Pang, Y.; Liu, C.; Shao, Z.; Zhu, J.; et al. TERT rs2736100T/G polymorphism upregulates interleukin 6 expression in non-small cell lung cancer especially in adenocarcinoma. Tumor Biol 2014, 35, 4667–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourantas, K.L.; Hatzimichael, E.C.; Makis, A.C.; Chaidos, A.; Kapsali, E.D.; Tsiara, S.; Mavridis, A. Serum beta-2-microglobulin, TNF-α and interleukins in myeloproliferative disorders. Eur J Haematol 1999, 63, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tefferi, A.; Vaidya, R.; Caramazza, D.; Finke, C.; Lasho, T.; Pardanani, A. Circulating Interleukin (IL)-8, IL-2R, IL-12, and IL-15 Levels Are Independently Prognostic in Primary Myelofibrosis: A Comprehensive Cytokine Profiling Study. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, R.; Gangat, N.; Jimma, T.; Finke, C.M.; Lasho, T.L.; Pardanani, A.; et al. Plasma cytokines in polycythemia vera: Phenotypic correlates, prognostic relevance, and comparison with myelofibrosis. Am J Hematol 2012, 87, 1003–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.C.; Tsai, W.H.; Jiang, M.L.; Ho, C.H.; Hsu, M.L.; Ho, C.K.; et al. Circulating levels of thrombopoietic and inflammatory cytokines in patients with clonal and reactive thrombocytosis. J Lab Clin Med 1999, 134, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.L.; Lasho, T.L.; Butterfield, J.H.; Tefferi, A. Global cytokine analysis in myeloproliferative disorders. Leuk Res 2007, 31, 1389–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mambet, C.; Babosova, O.; Defour, J.P.; Leroy, E.; Necula, L.; Stanca, O.; et al. Cooccurring JAK2 V617F and R1063H mutations increase JAK2 signaling and neutrophilia in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2018, 132, 2695–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.J.; Baltay, M.; Getz, A.; Fuhrman, K.; Aster, J.C.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Gene expression profiling distinguishes prefibrotic from overtly fibrotic myeloproliferative neoplasms and identifies disease subsets with distinct inflammatory signatures. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0216810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourcelot, E.; Trocme, C.; Mondet, J.; Bailly, S.; Toussaint, B.; Mossuz, P. Cytokine profiles in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia patients: Clinical implications. Exp Hematol 2014, 42, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangemi, S.; Allegra, A.; Pace, E.; Alonci, A.; Ferraro, M.; Petrungaro, A.; et al. Evaluation of interleukin-23 plasma levels in patients with polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Cell Immunol 2012, 278, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, K.E.; Hatzimichael, E.C.; Bouranta, P.K.; Katsaraki, A.; Seferiadis, K.; Stebbing, J.; et al. Serum interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, sIL-2Ra, IL-6 and thrombopoietin levels in patients with chronic myeloproliferative diseases. Br J Haematol 2005, 130, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, M.; Hernández-Lemus, E. Periodontal Inflammation and Systemic Diseases: An Overview. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 709438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadowaki, T.; Nakayama, K.; Okamoto, K.; Abe, N.; Baba, A.; Shi, Y.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis Proteinases as Virulence Determinants in Progression of Periodontal Diseases. J Biochem 2000, 128, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.; Hujoel, P.; Belibasakis, G.N. On putative periodontal pathogens: an epidemiological perspective. Virulence 2015, 6, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socransky, S.S.; Haffajee, A.D.; Cugini, M.A.; Smith, C.; Kent, R.L. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol 1998, 25, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Xuan, S.; Wang, Z. Oral microbiota: A new view of body health. Food Sci Hum Wellness 2019, 8, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, D.C.; Cerajewska, T.L.; Seong, J.; Davies, M.; Paterson, A.; Allen-Birt, S.J.; et al. Comparison of Blood Bacterial Communities in Periodontal Health and Periodontal Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 10, 577485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S.; Hosomi, N.; Nishi, H.; Nakamori, M.; Nezu, T.; Shiga, Y.; et al. Serum IgG titers to periodontal pathogens predict 3-month outcome in ischemic stroke patients. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0237185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Woo, H.G.; Park, J.; Lee, J.S.; Song, T.J. Improved oral hygiene care is associated with decreased risk of occurrence for atrial fibrillation and heart failure: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020, 27, 1835–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.R.; Chapple, I.L.; Matthews, J.B. Peripheral blood neutrophil cytokine hyper-reactivity in chronic periodontitis. Innate Immun 2015, 21, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Farrar, W.L.; Yang, X. Transcriptional crosstalk between nuclear receptors and cytokine signal transduction pathways in immunity. Cell Mol Immunol 2004, 1, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kato, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Nakajima, M.; Date, Y.; Kikuchi, J.; Hase, K.; et al. Oral Administration of Porphyromonas gingivalis Alters the Gut Microbiome and Serum Metabolome. mSphere 2018, 3, e00460-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominy, S.S.; Lynch, C.; Ermini, F.; Benedyk, M.; Marczyk, A.; Konradi, A.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv 2019, 5, eaau3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyama, M.; Yoshida, K.; Yoshida, K.; Fujiwara, N.; Ono, K.; Eguchi, T.; et al. Outer membrane vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis attenuate insulin sensitivity by delivering gingipains to the liver. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866, 165731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, Y.; Castellanos, J.; Lafaurie, G.; Castillo, D. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles modulate cytokine and chemokine production by gingipain-dependent mechanisms in human macrophages. Arch Oral Biol 2022, 140, 105453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and ROS-Induced ROS Release. Physiol Rev 2014, 94, 909–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Feng, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z. Trem2 mediated Syk-dependent ROS amplification is essential for osteoclastogenesis in periodontitis microenvironment. Redox Biol 2021, 40, 101849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, N.; Kanai, T.; Okada, M. Rheumatoid Arthritis and Reactive Oxygen Species: A Review. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2023, 45, 3000–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, L.E.; Broniowska, K.A.; Hansen, P.A.; Corbett, J.A.; Tse, H.M. The role of reactive oxygen species and proinflammatory cytokines in type 1 diabetes pathogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2013, 1281, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Ohara, N.; Sato, K.; Yoshimura, M.; Yukitake, H.; Sakai, E.; et al. Novel stationary-phase-upregulated protein of Porphyromonas gingivalis influences production of superoxide dismutase, thiol peroxidase and thioredoxin. Microbiology 2005, 151, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalley, J.W.; Birss, A.J.; Silver, J. The periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis harnesses the chemistry of the μ-oxo bishaem of iron protoporphyrin IX to protect against hydrogen peroxide. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2000, 183, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Spooner, R.; DeGuzman, J.; Koutouzis, T.; Ojcius, D.M.; Yilmaz, Ö. Porphyromonas gingivalis -nucleoside-diphosphate-kinase inhibits ATP-induced reactive-oxygen-species via P2X7 receptor/NADPH-oxidase signalling and contributes to persistence: Porphyromonas inhibits ROS production. Cell Microbiol 2013, 15, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreschi, K.; Laurence, A.; O’Shea, J.J. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev 2009, 228, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrajoli, A.; Faderl, S.; Ravandi, F.; Estrov, Z. The JAK-STAT Pathway: A Therapeutic Target in Hematological Malignancies. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2006, 6, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; Duan, X.; Jotwani, R.; Vuddaraju, H.; Liang, S.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis-Induced Reactive Oxygen Species Activate JAK2 and Regulate Production of Inflammatory Cytokines through c-Jun. Infect Immun 2014, 82, 4118–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancuța, C.; Pomîrleanu, C.; Mihailov, C.; Chirieac, R.; Ancuța, E.; Iordache, C.; et al. Efficacy of baricitinib on periodontal inflammation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine 2020, 87, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Shi, F.; Zhang, Y. Baricitinib alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced human periodontal ligament stem cell injury and promotes osteogenic differentiation by inhibiting JAK/STAT signaling. Exp Ther Med 2022, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoi, M.A.; Camilli, A.C.; Gonzales, K.G.A.; Costa, V.B.; Papathanasiou, E.; Leite, F.R.M.; et al. JAK/STAT as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Osteolytic Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orliaguet, M.; Boisramé, S.; Eveillard, J.; Pan-Petesch, B.; Couturier, M.; Rebière, V.; et al. Pegylated interferon 2a and ruxolitinib induce a high rate of oral complications among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. eJHaem 2020, 1, 350–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomokiyo, A.; Yoshida, S.; Hamano, S.; Hasegawa, D.; Sugii, H.; Maeda, H. Detection, Characterization, and Clinical Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Periodontal Ligament Tissue. Stem Cells Int 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lü, L.; Yakoumatos, L.; Ren, J.; Duan, X.; Zhou, H.; Gu, Z.; et al. JAK3 restrains inflammatory responses and protects against periodontal disease through Wnt3a signaling. FASEB J 2020, 34, 9120–9140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, J.K.; Kaur, G.; Buttar, H.S.; Bagabir, H.A.; Bagabir, R.A.; Bagabir, S.A.; et al. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in the pathophysiology of coronary heart disease and heart failure: Diagnostic biomarkers and therapy with drugs and natural products. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1034170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, S.J.; Jha, J.; McCart, E.A.; Rittase, W.B.; George, J.; Mattapallil, J.J.; et al. Captopril mitigates splenomegaly and myelofibrosis in the Gata1 low murine model of myelofibrosis. J Cell Mol Med 2018, 22, 4274–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.H.; Choi, E.Y.; Hyeon, J.Y.; Keum, B.R.; Choi, I.S.; Kim, S.J. Telmisartan, an angiotensin II receptor blocker, attenuates Prevotella intermedia lipopolysaccharide-induced production of nitric oxide and interleukin-1β in murine macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol 2019, 75, 105750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A.; Hayano, S.; Nagata, M.; Kosami, T.; Wang, Z.; Kamioka, H. Ruxolitinib altered IFN-β induced necroptosis of human dental pulp stem cells during osteoblast differentiation. Arch Oral Biol 2023, 155, 105797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksandrowicz, P.; Kotuła, L.; Grabowska, K.; Krakowiak, R.; Kusa-Podkańska, M.; Agier, J.; et al. Evaluation of circulating CD34+ stem cells in peripheral venous blood in patients with varying degrees of periodontal disease. Ann Agric Environ Med 2021, 28, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delano, M.J.; Scumpia, P.O.; Weinstein, J.S.; Coco, D.; Nagaraj, S.; Kelly-Scumpia, K.M.; et al. MyD88-dependent expansion of an immature GR-1+CD11b+ population induces T cell suppression and Th2 polarization in sepsis. J Exp Med 2007, 204, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Xia, L.; Liu, Y.C.; Hochman, T.; Bizzari, L.; Aruch, D.; et al. Lipocalin produced by myelofibrosis cells affects the fate of both hematopoietic and marrow microenvironmental cells. Blood 2015, 126, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, C.; Lacout, C.; Droin, N.; Le Couédic, J.P.; Ribrag, V.; Solary, E.; et al. A role for reactive oxygen species in JAK2V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm progression. Leukemia 2013, 27, 2187–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanelli, R.; Carolei, A.; Catarsi, P.; Abbà, C.; Boveri, E.; Paulli, M.; et al. Circulating Polymorphonuclear Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (PMN-MDSCs) Have a Biological Role in Patients with Primary Myelofibrosis. Cancers 2024, 16, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Kundra, A.; Andrei, M.; Baptiste, S.; Chen, C.; Wong, C.; et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasm. Leuk Res 2016, 43, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leija-Montoya, A.G.; González-Ramírez, J.; Serafín-Higuera, I.; Sandoval-Basilio, J.; Isiordia-Espinoza, M.; Serafín-Higuera, N. Emerging avenues linking myeloid-derived suppressor cells to periodontal disease. In International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 165–189. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1937644822001459 (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- García-Arévalo, F.; Leija-Montoya, A.G.; González-Ramírez, J.; Isiordia-Espinoza, M.; Serafín-Higuera, I.; Fuchen-Ramos, D.M.; et al. Modulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cell functions by oral inflammatory diseases and important oral pathogens. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1349067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.S.; Yoon, S.Y.; Jeong, S.Y.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, N.; et al. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and carotid plaque burden in patients with essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2022, 32, 1913–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolach, O.; Sellar, R.S.; Martinod, K.; Cherpokova, D.; McConkey, M.; Chappell, R.J.; et al. Increased neutrophil extracellular trap formation promotes thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Transl Med 2018, 10, eaan8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, D.; Nagarkoti, S.; Kumar, A.; Dubey, M.; Singh, A.K.; Pathak, P.; et al. Oxidized LDL induced extracellular trap formation in human neutrophils via TLR-PKC-IRAK-MAPK and NADPH-oxidase activation. Free Radic Biol Med 2016, 93, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Rizo, V.; Martínez-Guzmán, M.A.; Iñiguez-Gutierrez, L.; García-Orozco, A.; Alvarado-Navarro, A.; Fafutis-Morris, M. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Its Implications in Inflammation: An Overview. Front Immunol 2017, 8. Available online: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00081/full (accessed on 25 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Li, J.; Wu, Z. Neutrophil extracellular traps induced by diabetes aggravate periodontitis by inhibiting janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription signaling in macrophages. J Dent Sci 2024, S1991790224003179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, B.; Zou, L.; He, B.; Li, M. The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Periodontitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 639144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Guo, R.; Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Ding, D.; et al. Single-cell atlas of human gingiva unveils a NETs-related neutrophil subpopulation regulating periodontal immunity. J Adv Res 2024, S2090123224003126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Li, T.; Tang, J.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Gou, H.; et al. CXCR4-mediated neutrophil dynamics in periodontitis. Cell Signal 2024, 120, 111212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papapanagiotou, D.; Nicu, E.A.; Bizzarro, S.; Gerdes, V.E.A.; Meijers, J.C.; Nieuwland, R.; et al. Periodontitis is associated with platelet activation. Atherosclerosis 2009, 202, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Bai, J.; Luo, Y.; Song, J.; Feng, P. Mean platelet volume is associated with periodontitis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, C.; Alonci, A.; Bellomo, G.; Tringali, O.; Spatari, G.; Quartarone, C.; et al. Myeloproliferative Disease: Markers of Endothelial and Platelet Status in Patients with Essential Thrombocythemia and Polycythemia Vera. Hematol Amst Neth 2000, 4, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T.; Bartold, P.M. Periodontitis and periodontopathic bacteria as risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis: A review of the last 10 years. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 2023, 59, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sete, M.R.C.; Figueredo, C.M.D.S.; Sztajnbok, F. Periodontitis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rev Bras Reumatol Engl Ed 2016, 56, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, V.; Sabavath, S.; Babu, C.; Boyapati, L. Estimation of YKL-40 acute-phase protein in serum of patients with periodontal disease and healthy individuals: A clinical-biochemical study. Contemp Clin Dent 2019, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, Z.P.; Keles, G.C.; Avci, B.; Cetinkaya, B.O.; Emingil, G. Analysis of YKL-40 Acute-Phase Protein and Interleukin-6 Levels in Periodontal Disease. J Periodontol 2014, 85, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Li, G.; Chang, D.; Su, X. YKL-40 as a novel biomarker in cardio-metabolic disorders and inflammatory diseases. Clin Chim Acta 2020, 511, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, B.; Jia, Z.; Luo, J.; Han, X.; et al. A humanized Anti-YKL-40 antibody inhibits tumor development. Biochem Pharmacol 2024, 225, 116335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krečak, I.; Gverić-Krečak, V.; Lapić, I.; Rončević, P.; Gulin, J.; Fumić, K.; et al. Circulating YKL-40 in Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. Acta Clin Belg 2021, 76, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afacan, B.; Öztürk, V.Ö.; Paşalı, Ç.; Bozkurt, E.; Köse, T.; Emingil, G. Gingival crevicular fluid and salivary HIF-1α, VEGF, and TNF-α levels in periodontal health and disease. J Periodontol 2019, 90, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, H.F. VPF/VEGF and the angiogenic response. Semin Perinatol 2000, 24, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C. Enhanced VEGF-A expression and mediated angiogenic differentiation in human gingival fibroblasts by stimulating with TNF-α in vitro. J Dent Sci 2022, 17, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treliński, J.; Wierzbowska, A.; Krawczyńska, A.; Sakowicz, A.; Pietrucha, T.; Smolewski, P.; et al. Plasma levels of angiogenic factors and circulating endothelial cells in essential thrombocythemia: correlation with cytoreductive therapy and JAK2–V617F mutational status. Leuk Lymphoma 2010, 51, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.R.; Anitha, J.R.; Pai, A.; Yaji, A.Y.; Jambunath, U.; Yadav, K. Oral manifestations of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia—a diagnostic perspective. Hematol Transfus Int J 2018, 6. Available online: https://medcraveonline.com/HTIJ/oral-manifestations-of-myeloid-neoplasms-and-acute-leukemia--a-diagnostic-perspective.html (accessed on 12 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lombardo Bedran, T.B.; Palomari Spolidorio, D.; Grenier, D. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate and cranberry proanthocyanidins act in synergy with cathelicidin (LL-37) to reduce the LPS-induced inflammatory response in a three-dimensional co-culture model of gingival epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Arch Oral Biol 2015, 60, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, P.J.; MacLean, C.; Beer, P.A.; Buck, G.; Wheatley, K.; Kiladjian, J.J.; et al. Correlation of blood counts with vascular complications in essential thrombocythemia: analysis of the prospective PT1 cohort. Blood 2012, 120, 1409–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Campbell, P.; Buck, G.; Wheatley, K.; East, C.; Bareford, D.; et al. The Medical Research Council PT1 Trial in Essential Thrombocythemia. Blood 2004, 104, 6–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Acker, H.H.; Capsomidis, A.; Smits, E.L.; Van Tendeloo, V.F. CD56 in the Immune System: More Than a Marker for Cytotoxicity? Front Immunol 2017, 8, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa Lopes, M.L.D.; De Aguiar, J.N.M.; De Brito Monteiro, B.V.; De Oliveira Nóbrega, F.J.; Da Silveira, É.J.D.; Da Costa Miguel, M.C. PP-IMMUNOEXPRESSION OF IL-17, IL-23 AND RORγT IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF PERIODONTAL DISEASE. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2017, 123, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wu, Y.; Wei, H.; Yang, S.; Zhan, N.; Xing, X.; et al. Up-regulation of IL-23 p19 expression in human periodontal ligament fibroblasts by IL-1β via concurrent activation of the NF-κB and MAPKs/AP-1 pathways. Cytokine 2012, 60, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Ehara, M.; Suzuki, S.; Ohmori, Y.; Sakashita, H. IL-23 promotes growth and proliferation in human squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Int J Oncol 2010, 36. Available online: http://www.spandidos-publications.com/ijo/36/6/1355 (accessed on 13 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.T.; Wong, Y.K.; Hsiao, H.Y.; Wang, Y.W.; Chan, M.Y.; Chang, K.W. Evaluation of saliva and plasma cytokine biomarkers in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018, 47, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, M.O.; Cruz, Á.A.; Teixeira, H.M.P.; Silva, H.D.S.; Gomes-Filho, I.S.; Trindade, S.C.; et al. Variants in interferon gamma inducible protein 16 (IFI16) and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) genes that modulate inflammatory response are associated with periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol 2023, 147, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balu, P.; Balakrishna Pillai, A.K.; Mariappan, V.; Ramalingam, S. Cytokine levels in gingival tissues as an indicator to understand periodontal disease severity. Curr Res Immunol 2024, 5, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalerič, U.; Kramar, B.; Petelin, M.; Pavllia, Z.; Wahl, S.M. Changes in TGF-β1 levels in gingiva, crevicular fluid and serum associated with periodontal inflammation in humans and dogs. Eur J Oral Sci 1997, 105, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.Y.; Qin, L.; Baeyens, N.; Li, G.; Afolabi, T.; Budatha, M.; et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition drives atherosclerosis progression. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 4514–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, K.; Krzanowski, M.; Dumnicka, P.; Kusnierz-Cabala, B.; Krasniak, A.; Sulowicz, W. Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 as a Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Diseases in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients Treated With Peritoneal Dialysis. Clin Lab 2014, 60. Available online: http://www.clin-lab-publications.com/article/1551 (accessed on 26 June 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesseling, M.; Sakkers, T.R.; De Jager, S.C.A.; Pasterkamp, G.; Goumans, M.J. The morphological and molecular mechanisms of epithelial/endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and its involvement in atherosclerosis. Vascul Pharmacol 2018, 106, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamonal, J.; Bascones, A.; Jorge, O.; Silva, A. Chemokine RANTES in gingival crevicular fluid of adult patients with periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 2000, 27, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamonal, J.; Acevedo, A.; Bascones, A.; Jorge, O.; Silva, A. Characterization of cellular infiltrate, detection of chemokine receptor CCR5 and interleukin-8 and RANTES chemokines in adult periodontitis. J Periodontal Res 2001, 36, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emingil, G.; Atilla, G.; Hüseyinov, A. Gingival crevicular fluid monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and RANTES levels in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 2004, 31, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Sharma, A.; Nadela, M. RANTES comparison in patients with periodontal disease—A prospective clinical study. Future Dent J 2018, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hundelshausen, P.; Weber, K.S.C.; Huo, Y.; Proudfoot, A.E.I.; Nelson, P.J.; Ley, K.; et al. RANTES Deposition by Platelets Triggers Monocyte Arrest on Inflamed and Atherosclerotic Endothelium. Circulation 2001, 103, 1772–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossaint, J.; Herter, J.M.; Van Aken, H.; Napirei, M.; Döring, Y.; Weber, C.; et al. Synchronized integrin engagement and chemokine activation is crucial in neutrophil extracellular trap–mediated sterile inflammation. Blood 2014, 123, 2573–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiano, J.E., Jr.; Battinelli, E.M. Selective sorting of alpha-granule proteins. J Thromb Haemost 2009, 7, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Oyarzún, C.P.; Glembotsky, A.C.; Goette, N.P.; Lev, P.R.; De Luca, G.; Baroni Pietto, M.C.; et al. Platelet Toll-Like Receptors Mediate Thromboinflammatory Responses in Patients With Essential Thrombocythemia. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Wu, B.; Ji, L.; Zhan, Y.; Li, F.; Cheng, L.; et al. Cytokine Consistency Between Bone Marrow and Peripheral Blood in Patients With Philadelphia-Negative Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Front Med 2021, 8, 598182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wilkinson, F.; Kirton, J.; Jeziorska, M.; Iizasa, H.; Sai, Y.; et al. Hepatocyte growth factor and c-Met expression in pericytes: implications for atherosclerotic plaque development. J Pathol 2007, 212, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönn, J.; Starkhammar Johansson, C.; Kälvegren, H.; Brudin, L.; Skoglund, C.; Garvin, P.; et al. Hepatocyte growth factor in patients with coronary artery disease and its relation to periodontal condition. Results Immunol 2012, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissinot, M.; Cleyrat, C.; Vilaine, M.; Jacques, Y.; Corre, I.; Hermouet, S. Anti-inflammatory cytokines hepatocyte growth factor and interleukin-11 are over-expressed in Polycythemia vera and contribute to the growth of clonal erythroblasts independently of JAK2V617F. Oncogene 2011, 30, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coudriet, G.M.; He, J.; Trucco, M.; Mars, W.M.; Piganelli, J.D. Hepatocyte Growth Factor Modulates Interleukin-6 Production in Bone Marrow Derived Macrophages: Implications for Inflammatory Mediated Diseases. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Y.F.; Zhao, L.; Xiao, F.J.; Zhang, Q.W.; Wen, M.L.; et al. Hepatocyte Growth Factor Gene-Modified Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reduce Radiation-Induced Lung Injury. Hum Gene Ther 2013, 24, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissinot, M.; Vilaine, M.; Hermouet, S. The Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF)/Met Axis: A Neglected Target in the Treatment of Chronic Myeloproliferative Neoplasms? Cancers 2014, 6, 1631–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: An Overview of Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şehirli, A.Ö.; Aksoy, U.; Koca-Ünsal, R.B.; Sayıner, S. Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in COVID-19 and periodontitis: Possible protective effect of melatonin. Med Hypotheses 2021, 151, 110588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, T.P.; Xue, C.; Yalcinkaya, M.; Hardaway, B.; Abramowicz, S.; Xiao, T.; et al. The AIM2 inflammasome exacerbates atherosclerosis in clonal haematopoiesis. Nature 2021, 592, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeodato, C.S.R.; Soares-Lima, S.C.; Batista, P.V.; Fagundes, M.C.N.; Camuzi, D.; Tavares, S.J.O.; et al. Interleukin 6 and Interleukin 1β hypomethylation and overexpression are common features of apical periodontitis: A case-control study with gingival tissue as control. Arch Oral Biol 2023, 150, 105694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, S.; Valentini, G.; Dolci, M. Exploring Interleukin Levels in Type 1 Diabetes and Periodontitis: A Review with a Focus on Childhood. Children 2024, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, T.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L. Identification of Novel Risk Variants of Inflammatory Factors Related to Myeloproliferative Neoplasm: A Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study. Glob Med Genet 2024, 11, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Zhang, H.; Bai, J.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, L. Associations of the circulating levels of cytokines with the risk of myeloproliferative neoplasms: a bidirectional mendelian-randomization study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, D.E.; Hariyani, N.; Indrawati, R.; Ridwan, R.D.; Diyatri, I. Cytokines and Chemokines in Periodontitis. Eur J Dent 2020, 14, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysanthakopoulos, N.A. Correlation between periodontal disease indices and lung cancer in Greek adults: a case-control study. Exp Oncol 2016, 38, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, X.; LaMonte, M.J.; Hovey, K.M.; Nwizu, N.; Freudenheim, J.L.; Tezal, M.; et al. History of periodontal disease diagnosis and lung cancer incidence in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Cancer Causes Control 2014, 25, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, D.S.; Joshipura, K.; Giovannucci, E.; Fuchs, C.S. A Prospective Study of Periodontal Disease and Pancreatic Cancer in US Male Health Professionals. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 2007, 99, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, K.; Jha, A.R.; Zhao, T.; Uy, J.P.; Sun, C. Is periodontal disease associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer? A meta-analysis. Int J Dent Hyg 2021, 19, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famili, P.; Cauley, J.A.; Greenspan, S.L. The Effect of Androgen Deprivation Therapy on Periodontal Disease in Men With Prostate Cancer. J Urol 2007, 177, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Xia, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Leng, W.; Kwong, J.S.W. Periodontal Disease and Incident Lung Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J Periodontol 2016, 87, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Zou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Relationship between periodontal disease and lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontal Res 2020, 55, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizdar, O.; Hayran, M.; Guven, D.C.; Yılmaz, T.B.; Taheri, S.; Akman, A.C.; et al. Increased cancer risk in patients with periodontitis. Curr Med Res Opin 2017, 33, 2195–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mediator | Role in PD | Role in MPNs | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| YKL-40 (CHI3L1) | Correlates with disease severity, elevated with IL-6 | Linked to increased inflammation, cardiovascular risk, thrombosis in ET/PV | [94,95,98] |

| VEGF | Increases vascular permeability, exacerbating inflammation | Elevated in ET, associated with bleeding tendencies | [99,100,102] |

| GRO-alpha | Promotes neutrophil chemotaxis in inflamed tissue | Elevated in ET, correlates with progression to MF | [104,105] |

| IL-23 | Enhances Th17 response and tissue damage | Elevated in PV, promotes cell proliferation and tumor growth | [37,109,110] |

| Eotaxin-1 | Recruits eosinophils, contributes to inflammation | Elevated in PV/ET, linked to chronic inflammation | [111,112] |

| TGF-β | Dual role in inflammation and tissue repair | Contributes to arterial plaque and coronary damage | [113,114,115,116,117] |

| RANTES | High levels in severe PD; attracts immune cells | Increased in ET, linked to localized thrombo-inflammatory processes | [118,119,124,125,126] |

| HGF | Increases with disease progression, stimulated by P. gingivalis | Overproduced in JAK2 V617F MPNs; promotes progenitor cell growth | [127,128,130,132] |

| NLRP3 inflammasome | Drives chronic inflammation, triggered by pathogens | Upregulated in MPNs, leading to excessive cytokine release | [10,133,134] |

| AIM2 inflammasome | Releases IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 in response to pathogens | Hyperactive in JAK2-mutant MPNs, driving IL-1β signaling | [112,135] |

| IL-1β and IL-6 | Induces bone resorption and tissue damage | Elevated in MPNs (ET/PV/PMF), leading to systemic inflammation | [22,29,30,33,36,136] |

| IL2Rα | Genetic variant linked to PD susceptibility in Type 1 Diabetes | High levels associated with MPN risk | [137,138,139] |

| IP-10 | Attracts immune cells to periodontal tissue, intensifying inflammation | High levels associated with MPN risk | [137,139,140] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).