Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Key Features of IL-18

- IL-18, originally named IFN-γ-inducing factor, is a member of the IL-1 family, links innate and adaptive immunity and is regulated by the cytokine it induces.

- IL-18 is a double-edged sword cytokine that can either be detrimental, by promoting inflammation, or beneficial, by regulating immune responses to restore homeostasis, depending on the microenvironment.

- IL-18 can function as a Th1or Th2 cytokine depending on the immune microenvironment.

- IL-18 does not require de novo synthesis. The inactive pro IL-18 is always on standby, ready to be processed by caspase 1 into its biologically active form.

- IL-18 is included in an exclusive dictionary of cytokines, a dictionary that provides a specific signature of the cellular response of each immune cell-type to a variety of cytokines. Induction of interferon-gamma (IFN-g) is IL-18’s signature and NK cells are its main target. IL-18 triggers the upregulation of more than 1,000 genes, an order of magnitude higher compared to other cytokines.

- IL-18 signals through an evolutionary conserved IL-18 receptor consisting of a ligand- binding chain and an accessory chain. Signal transduction involves recruitment of MyD88, the four IRAKs and TNF receptor activating factor-6 (TRAF-6) leading to IκB degradation, NFκB release and the activation of a proinflammatory cascade.

- IL-18 plays a role in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, inborn disorders, infectious diseases including severe cases of Covid 19, and cancer.

- IL-18 serves as a biomarker in disorders characterized by elevated IL-18 levels, referred to as "IL-18opathies," a term coined to facilitate differential diagnosis in these pathologies.

- IL-18 is a checkpoint biomarker in cancer and IL-18-engineered CAR-T cells have demonstrated an enhanced tumor-killing ability in solid tumors particularly in immunotherapies involving PD-1 blockade.

- A cytokine storm, with IL-18 as one of its key players, represents the harmful side of IL-18. This storm can occur as a complication of viral infections, autoimmune diseases, cancer, and CAR-T therapy. Recently, the external administration of IL-18's antidote, IL-18BP, has been tested as a potential rescue treatment.

- Blocking IL-18 is a safer option compared to blocking its family member, the master cytokine IL-1, since prolonged IL-1 inhibition can lead to severe infections.

Key Features of IL-18BP

- IL-18 Binding Protein, unlike canonical soluble receptors, is a rare example of a cytokine antagonist encoded by a separate gene.

- IL-18BP is a glycosylated protein that binds to mature but not to the inactive pro-IL-18. In humans IL-18BPa is the most abundant and the most active of four splice variants.

- IL-18BPa is exceptional for its extremely high affinity to IL-18 and its slow dissociation rate (Koff), ensuring the stability of the dyad complex. This makes it an ideal regulator of IL-18 signaling and a promising therapeutic agent.

- IL-18BPa pharmacokinetics: IL-18BPa has an elimination half-life of 34-40 hours when administered subcutaneously at doses of 80 mg and 160 mg to patients three times a week. Unlike antibody treatments, with a half-life of 3-4 weeks, IL-18BP's shorter half-life allows for more rapid cessation, enabling timely IL-18 activity when needed for immune defense.

- The balance between IL-18 and IL-18BPa, and particularly the level of free IL-18, all regulated by IFN-g in a feedback loop mechanism, are crucial in maintaining homeostasis, and in determining disease outcomes.

- IL-18BP deficiency can be life-threatening and, when left untreated, has proven to be fatal.

- Tadekinig alfa, a recombinant IL-18BPa, is a life-saving drug that has rescued children with inborn IL-18 overexpression and organ failure. A Phase III clinical study had been completed and it is in compassionate use for seven years now with no reported adverse effects. Beneficial also in Still’s disease it shows promise for treating cytokine storms caused by viral infections, cancer and CAR-T therapy.

IL-18

1.1. IL-18 Is an IFN-g Inducing Factor (IGIF)

1.2. IL-18 Is of a Dual Nature

1.3. IL-18 Is a Th1 and a Th2 Cytokine

1.4. Pro-IL-18: Always on Standby

1.5. IL-18 Dictionary of Interactions

1.6. IL-18: A Non-Master Cytokine

1.7. IL-18 Regulation

1.8. Cells Producing IL-18

2. IL-18 Receptor

2.1. IL-18 Receptor Composition

2.2. IL-18 Receptor: Evolutionary Conserved

2.3. IL-18 Receptor Expression

2.4. IL-18 Receptor Binding Sites

2.5. IL-18 Affinity to Its Receptor

3. IL-18 Knockout Models

4. IL-18 in Health and Disease

4.1. IL-18 and Free IL-18 Levels in Healthy Individuals and in a Pathology

4.2. IL-18’opathies

4.2.1. IL-18 in NLRC4 Associated Inflammasomopathies

4.2.2. IL-18 in XIAP Deficiency

4.2.3. IL-18 in Still’s Disease

4.2.4. IL-18: Predictor of Mortality in Acute Renal Disease

4.2.5. IL-18 in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

4.2.6. IL-18 in Gastrointestinal System

4.2.7. IL-18 in Covid 19

4.2.8. IL-18 in Cancer: A Double-Edged Sword

4.2.9. IL-18 and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

4.2.10. IL-18 Enhances CAR-T Treatment

4.2.11. IL-18 Toxicity in CAR T-Cell Therapy

4.2.12. IL-18 in Skin Diseases

4.2.13. IL-18 in Other Pathologies

5. IL-18 Binding Protein (IL-18BP)

5.1. IL-18BP Is Not a Canonical Soluble Receptor

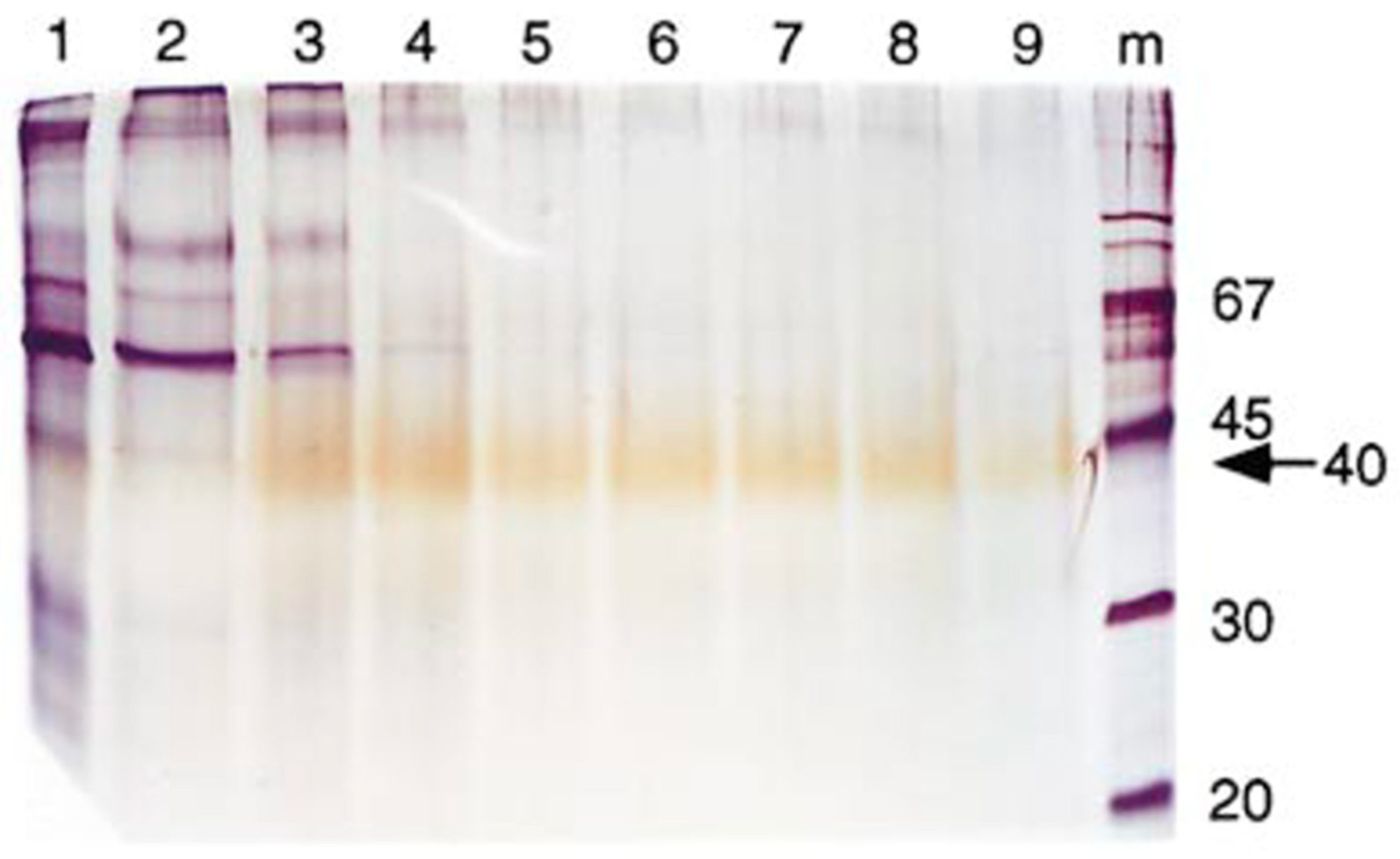

5.2. IL-18BP Isolation and Cloning

5.3. Regulation of IL-18BP

5.4. IL-18BP Promoter

5.5. IL-18BP Evolutionary Importance

5.6. IL-18BP Knockout Mice

5.7. IL-18BP Affinity and Dissociation Rate: Advantages for Drug Development

5.8. IL-18BP Level in Health and Disease

6. The Clinical Relevance of IL-18 and IL-18BP

6.1. The Therapeutic Potential of IL-18/IL-18BP Axis

6.2. IL-18 in Differential Diagnosis (HLH and MAS)

6.3. IL-18BP in Covid 19

6.4. Fatal IL-18BP Deficiency

6.5. Safety and Tolerability of IL-18BP Therapy

Targeting IL-18

7.1. IL-18 Inhibitory Drugs (Table 1)

7.1.1. IL-18 Binding Protein (Tadekinig alfaTM) by AB2 Bio

7.1.2. IL-18 Antibody (GSK-1070806) by GlaxoSmithKline

7.1.3. IL-18 Antibody (Camoteskimab) by Apollo Therapeutics (Avalo Therapeutics and MedImmune)

7.1.4. IL-18 and IL-1 Bispecific Antibody (MAS825) by Novartis

7.1.5. NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitor (Dapansutrile) by Olatec Therapeutics

7.2. IL-18 Enhancing Drugs (Table 2)

7.2.1. IL-18 Variant (ST-067) by Simcha Therapeutics (USA)

7.2.2. Modified IL-18 Fused to Fc (XmAb143) by Xencor

7.2.3. Modified IL-18 Fused to Fc and Targeted to PD-1 (BPT 567/PD1-IL18-Fc) by Bright Peak Therapeutics

7.2.4. Modified and Conditionally Activated IL-18 Resistant to IL-18BP (WTX 518) by Werewolf Therapeutics

7.2.5. Antibody Based IL-18 Agonist Resistant to IL-18BP

7.3. IL-18 Activity Enhancement Strategy Using IL-18BP Antibodies

7.3.1. IL-18BP Antibody (COM503) by Compugen and Gilead

7.3.2. IL-18BP Antibody (LASN500) by Lassen Therapeutics

7.4. IL-18 and CAR T Combined Therapy (Table 3)

7.4.1. IL-18 and CAR T Combined Therapy by Janssen Research & Development

7.4.2. Eutilex Co. Ltd. in Korea Engineered a Combination of a Targeted Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumor (HCC) Marker, Glypican-3 (GPC3) and an IL-18-Secreting CAR T Cell Therapy (EU-307 GPC3-IL18) Which Is in Phase I and Designated for the Treatment of HCC and Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

7.4.3. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Is Conducting an Ongoing Phase I Study (NCT06017258) that Tests CAR T Cell Therapy Using a Combination of Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (AML) Marker and an IL- 18-Armored Construct (CD371-YSNVZIL-18). This Study Is Expected to Be Completed in 2026

8. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aggarwal, B. B. (2003). Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol, 3(9), 745-756. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, F., Istomine, R., Da Silva Lira Filho, A., Al-Aubodah, T. A., Huang, D., Okde, R., Olivier, M., Fritz, J. H., & Piccirillo, C. A. (2023). IL-18 is required for the T(H)1-adaptation of T(REG) cells and the selective suppression of T(H)17 responses in acute and chronic infections. Mucosal Immunol, 16(4), 462-475. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M., Pfeilschifter, J., & Mühl, H. (2018). A Prominent Role of Interleukin-18 in Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury Advocates Its Blockage for Therapy of Hepatic Necroinflammation. Front Immunol, 9, 161. [CrossRef]

- Baggio, C., Bindoli, S., Guidea, I., Doria, A., Oliviero, F., & Sfriso, P. (2023). IL-18 in Autoinflammatory Diseases: Focus on Adult Onset Still Disease and Macrophages Activation Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci, 24(13). [CrossRef]

- Baud'huin, M., Duplomb, L., Teletchea, S., Lamoureux, F., Ruiz-Velasco, C., Maillasson, M., Redini, F., Heymann, M. F., & Heymann, D. (2013). Osteoprotegerin: multiple partners for multiple functions. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 24(5), 401-409. [CrossRef]

- Behrens, E. M. (2024). Cytokines in Cytokine Storm Syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol, 1448, 173-183. [CrossRef]

- Belkaya, S., Michailidis, E., Korol, C. B., Kabbani, M., Cobat, A., Bastard, P., Lee, Y. S., Hernandez, N., Drutman, S., de Jong, Y. P., Vivier, E., Bruneau, J., Béziat, V., Boisson, B., Lorenzo-Diaz, L., Boucherit, S., Sebagh, M., Jacquemin, E., Emile, J. F., . . . Casanova, J. L. (2019). Inherited IL-18BP deficiency in human fulminant viral hepatitis. J Exp Med, 216(8), 1777-1790. [CrossRef]

- Bindoli, S., Baggio, C., Doria, A., & Sfriso, P. (2024). Adult-Onset Still's Disease (AOSD): Advances in Understanding Pathophysiology, Genetics and Emerging Treatment Options. Drugs, 84(3), 257-274. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, F., Duplomb, L., Baud'huin, M., & Brounais, B. (2009). The dual role of IL-6-type cytokines on bone remodeling and bone tumors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 20(1), 19-28. [CrossRef]

- Bosmann, M., & Ward, P. A. (2013). Modulation of inflammation by interleukin-27. J Leukoc Biol, 94(6), 1159-1165. [CrossRef]

- Canna, S. W., & Cron, R. Q. (2020). Highways to hell: Mechanism-based management of cytokine storm syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 146(5), 949-959. [CrossRef]

- Canna, S. W., & De Benedetti, F. (2024). The 4(th) NextGen therapies of SJIA and MAS, part 4: it is time for IL-18 based trials in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis? Pediatr Rheumatol Online J, 21(Suppl 1), 79. [CrossRef]

- Canna, S. W., de Jesus, A. A., Gouni, S., Brooks, S. R., Marrero, B., Liu, Y., DiMattia, M. A., Zaal, K. J., Sanchez, G. A., Kim, H., Chapelle, D., Plass, N., Huang, Y., Villarino, A. V., Biancotto, A., Fleisher, T. A., Duncan, J. A., O'Shea, J. J., Benseler, S., . . . Goldbach-Mansky, R. (2014). An activating NLRC4 inflammasome mutation causes autoinflammation with recurrent macrophage activation syndrome. Nat Genet, 46(10), 1140-1146. [CrossRef]

- Canna, S. W., Girard, C., Malle, L., de Jesus, A., Romberg, N., Kelsen, J., Surrey, L. F., Russo, P., Sleight, A., Schiffrin, E., Gabay, C., Goldbach-Mansky, R., & Behrens, E. M. (2017). Life-threatening NLRC4-associated hyperinflammation successfully treated with IL-18 inhibition. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 139(5), 1698-1701. [CrossRef]

- Canna, S. W., & Marsh, R. A. (2020). Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood, 135(16), 1332-1343. [CrossRef]

- Canny, S. P., Stanaway, I. B., Holton, S. E., Mitchem, M., O'Rourke, A. R., Pribitzer, S., Baxter, S. K., Wurfel, M. M., Malhotra, U., Buckner, J. H., Bhatraju, P. K., Morrell, E. D., Speake, C., Mikacenic, C., & Hamerman, J. A. (2024). Identification of biomarkers for COVID-19 associated secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Cecrdlova, E., Krupickova, L., Fialova, M., Novotny, M., Tichanek, F., Svachova, V., Mezerova, K., Viklicky, O., & Striz, I. (2024). Insights into IL-1 family cytokines in kidney allograft transplantation: IL-18BP and free IL-18 as emerging biomarkers. Cytokine, 180, 156660. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, H., Zhou, J., Zhong, Y., Ali, M. M., McGuire, F., Nagarkatti, P. S., & Nagarkatti, M. (2013). Role of cytokines as a double-edged sword in sepsis. In Vivo, 27(6), 669-684.

- Chen, Y. T., Jenq, C. C., Hsu, C. K., Yu, Y. C., Chang, C. H., Fan, P. C., Pan, H. C., Wu, I. W., Cherng, W. J., & Chen, Y. C. (2020). Acute kidney disease and acute kidney injury biomarkers in coronary care unit patients. BMC Nephrol, 21(1), 207. [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, M., & Abken, H. (2017). CAR T Cells Releasing IL-18 Convert to T-Bet(high) FoxO1(low) Effectors that Exhibit Augmented Activity against Advanced Solid Tumors. Cell Rep, 21(11), 3205-3219. [CrossRef]

- Codarri Deak, L., Nicolini, V., Hashimoto, M., Karagianni, M., Schwalie, P. C., Lauener, L., Varypataki, E. M., Richard, M., Bommer, E., Sam, J., Joller, S., Perro, M., Cremasco, F., Kunz, L., Yanguez, E., Hüsser, T., Schlenker, R., Mariani, M., Tosevski, V., . . . Umaña, P. (2022). PD-1-cis IL-2R agonism yields better effectors from stem-like CD8(+) T cells. Nature, 610(7930), 161-172. [CrossRef]

- Coll, R. C., & Schroder, K. (2024). Inflammasome components as new therapeutic targets in inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. [CrossRef]

- Cui, A., Huang, T., Li, S., Ma, A., Pérez, J. L., Sander, C., Keskin, D. B., Wu, C. J., Fraenkel, E., & Hacohen, N. (2024). Dictionary of immune responses to cytokines at single-cell resolution. Nature, 625(7994), 377-384. [CrossRef]

- de Zoete, M. R., Palm, N. W., Zhu, S., & Flavell, R. A. (2014). Inflammasomes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 6(12), a016287. [CrossRef]

- Diorio, C., Shraim, R., Myers, R., Behrens, E. M., Canna, S., Bassiri, H., Aplenc, R., Burudpakdee, C., Chen, F., DiNofia, A. M., Gill, S., Gonzalez, V., Lambert, M. P., Leahy, A. B., Levine, B. L., Lindell, R. B., Maude, S. L., Melenhorst, J. J., Newman, H., . . . Teachey, D. T. (2022). Comprehensive Serum Proteome Profiling of Cytokine Release Syndrome and Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome Patients with B-Cell ALL Receiving CAR T19. Clin Cancer Res, 28(17), 3804-3813. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Bonin, J. P., Devant, P., Liang, Z., Sever, A. I. M., Mintseris, J., Aramini, J. M., Du, G., Gygi, S. P., Kagan, J. C., Kay, L. E., & Wu, H. (2024). Structural transitions enable interleukin-18 maturation and signaling. Immunity, 57(7), 1533-1548.e1510. [CrossRef]

- Dumoutier, L., Lejeune, D., Colau, D., & Renauld, J. C. (2001). Cloning and characterization of IL-22 binding protein, a natural antagonist of IL-10-related T cell-derived inducible factor/IL-22. J Immunol, 166(12), 7090-7095. [CrossRef]

- Edman, P. (1949). A method for the determination of amino acid sequence in peptides. Arch Biochem, 22(3), 475.

- Efthimiou, P., Kontzias, A., Hur, P., Rodha, K., Ramakrishna, G. S., & Nakasato, P. (2021). Adult-onset Still's disease in focus: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and unmet needs in the era of targeted therapies. Semin Arthritis Rheum, 51(4), 858-874. [CrossRef]

- Elson, G. C., Graber, P., Losberger, C., Herren, S., Gretener, D., Menoud, L. N., Wells, T. N., Kosco-Vilbois, M. H., & Gauchat, J. F. (1998). Cytokine-like factor-1, a novel soluble protein, shares homology with members of the cytokine type I receptor family. J Immunol, 161(3), 1371-1379.

- Engelmann, H., Novick, D., & Wallach, D. (1990). Two tumor necrosis factor-binding proteins purified from human urine. Evidence for immunological cross-reactivity with cell surface tumor necrosis factor receptors. J Biol Chem, 265(3), 1531-1536.

- Etna, M. P., Giacomini, E., Severa, M., & Coccia, E. M. (2014). Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in tuberculosis: a two-edged sword in TB pathogenesis. Semin Immunol, 26(6), 543-551. [CrossRef]

- Fabbi, M., Carbotti, G., & Ferrini, S. (2015). Context-dependent role of IL-18 in cancer biology and counter-regulation by IL-18BP. J Leukoc Biol, 97(4), 665-675. [CrossRef]

- Fauteux-Daniel, S., Girard-Guyonvarc'h, C., Caruso, A., Rodriguez, E., & Gabay, C. (2023). Detection of Free Bioactive IL-18 and IL-18BP in Inflammatory Disorders. Methods Mol Biol, 2691, 263-277. [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Riepe, L., Kailayangiri, S., Zimmermann, K., Pfeifer, R., Aigner, M., Altvater, B., Kretschmann, S., Völkl, S., Hartley, J., Dreger, C., Petry, K., Bosio, A., von Döllen, A., Hartmann, W., Lode, H., Görlich, D., Mackensen, A., Jungblut, M., Schambach, A., . . . Rossig, C. (2024). Preclinical Development of CAR T Cells with Antigen-Inducible IL18 Enforcement to Treat GD2-Positive Solid Cancers. Clin Cancer Res, 30(16), 3564-3577. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. D., Cepinskas, G., Slessarev, M., Martin, C., Daley, M., Miller, M. R., O'Gorman, D. B., Gill, S. E., Patterson, E. K., & Dos Santos, C. C. (2020). Inflammation Profiling of Critically Ill Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients. Crit Care Explor, 2(6), e0144. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C., A, S. M., & A, S. P. (2024). Unraveling the Intricacies of OPG/RANKL/RANK Biology and Its Implications in Neurological Disorders-A Comprehensive Literature Review. Mol Neurobiol. [CrossRef]

- Gabay, C., Fautrel, B., Rech, J., Spertini, F., Feist, E., Kötter, I., Hachulla, E., Morel, J., Schaeverbeke, T., Hamidou, M. A., Martin, T., Hellmich, B., Lamprecht, P., Schulze-Koops, H., Courvoisier, D. S., Sleight, A., & Schiffrin, E. J. (2018). Open-label, multicentre, dose-escalating phase II clinical trial on the safety and efficacy of tadekinig alfa (IL-18BP) in adult-onset Still's disease. Ann Rheum Dis, 77(6), 840-847. [CrossRef]

- Galozzi, P., Bindoli, S., Doria, A., & Sfriso, P. (2022). Progress in Biological Therapies for Adult-Onset Still's Disease. Biologics, 16, 21-34. [CrossRef]

- Geerlinks, A. V., & Dvorak, A. M. (2022). A Case of XIAP Deficiency Successfully Managed with Tadekinig Alfa (rhIL-18BP). J Clin Immunol, 42(4), 901-903. [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, R., Ruscitti, P., & Shoenfeld, Y. (2018). A comprehensive review on adult onset Still's disease. J Autoimmun, 93, 24-36. [CrossRef]

- Girard, C., Rech, J., Brown, M., Allali, D., Roux-Lombard, P., Spertini, F., Schiffrin, E. J., Schett, G., Manger, B., Bas, S., Del Val, G., & Gabay, C. (2016). Elevated serum levels of free interleukin-18 in adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatology (Oxford), 55(12), 2237-2247. [CrossRef]

- Girard-Guyonvarc'h, C., Palomo, J., Martin, P., Rodriguez, E., Troccaz, S., Palmer, G., & Gabay, C. (2018). Unopposed IL-18 signaling leads to severe TLR9-induced macrophage activation syndrome in mice. Blood, 131(13), 1430-1441. [CrossRef]

- Glienke, W., Dragon, A. C., Zimmermann, K., Martyniszyn-Eiben, A., Mertens, M., Abken, H., Rossig, C., Altvater, B., Aleksandrova, K., Arseniev, L., Kloth, C., Stamopoulou, A., Moritz, T., Lode, H. N., Siebert, N., Blasczyk, R., Goudeva, L., Schambach, A., Köhl, U., . . . Esser, R. (2022). GMP-Compliant Manufacturing of TRUCKs: CAR T Cells targeting GD(2) and Releasing Inducible IL-18. Front Immunol, 13, 839783. [CrossRef]

- Guha, A., Diaz-Pino, R., Fagbemi, A., Hughes, S. M., Wynn, R. F., Lopez-Castejon, G., & Arkwright, P. D. (2024). Very Early-Onset IBD-Associated IL-18opathy Treated with an Anti-IL-18 Antibody. J Clin Med, 13(20). [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A. D., Awili, M., O'Neal, H. R., Siddiqi, O., Jaffrani, N., Lee, R., Overcash, J. S., Chauffe, A., Hammond, T. C., Patel, B., Waters, M., Criner, G. J., Pachori, A., Junge, G., Levitch, R., Watts, J., Koo, P., Sengupta, T., Yu, L., . . . Matthews, J. (2023). Efficacy and safety of MAS825 (anti-IL-1β/IL-18) in COVID-19 patients with pneumonia and impaired respiratory function. Clin Exp Immunol, 213(3), 265-275. [CrossRef]

- Hand, T. W. (2015). Interleukin-18: The Bouncer at the Mucosal Bar. Cell, 163(6), 1310-1312. [CrossRef]

- Harms, R. Z., Creer, A. J., Lorenzo-Arteaga, K. M., Ostlund, K. R., & Sarvetnick, N. E. (2017). Interleukin (IL)-18 Binding Protein Deficiency Disrupts Natural Killer Cell Maturation and Diminishes Circulating IL-18. Front Immunol, 8, 1020. [CrossRef]

- He, Z., Lu, L., Altmann, C., Hoke, T. S., Ljubanovic, D., Jani, A., Dinarello, C. A., Faubel, S., & Edelstein, C. L. (2008). Interleukin-18 binding protein transgenic mice are protected against ischemic acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 295(5), F1414-1421. [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T., Izawa, K., Miyamoto, T., Honda, Y., Nishiyama, A., Shimizu, M., Takita, J., & Yasumi, T. (2022). An efficient diagnosis: A patient with X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) deficiency in the setting of infantile hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis was diagnosed using high serum interleukin-18 combined with common laboratory parameters. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 69(8), e29606. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, K., Tsutsui, H., Kawai, T., Takeda, K., Nakanishi, K., Takeda, Y., & Akira, S. (1999). Cutting edge: generation of IL-18 receptor-deficient mice: evidence for IL-1 receptor-related protein as an essential IL-18 binding receptor. J Immunol, 162(9), 5041-5044.

- Hu, B., Ren, J., Luo, Y., Keith, B., Young, R. M., Scholler, J., Zhao, Y., & June, C. H. (2017). Augmentation of Antitumor Immunity by Human and Mouse CAR T Cells Secreting IL-18. Cell Rep, 20(13), 3025-3033. [CrossRef]

- Hurgin, V., Novick, D., & Rubinstein, M. (2002). The promoter of IL-18 binding protein: activation by an IFN-gamma -induced complex of IFN regulatory factor 1 and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 99(26), 16957-16962. [CrossRef]

- Ihim, S. A., Abubakar, S. D., Zian, Z., Sasaki, T., Saffarioun, M., Maleknia, S., & Azizi, G. (2022). Interleukin-18 cytokine in immunity, inflammation, and autoimmunity: Biological role in induction, regulation, and treatment. Front Immunol, 13, 919973. [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y. S., Lee, K., Park, M., Joo Park, J., Choi, G. M., Kim, C., Dehkohneh, S. B., Chi, S., Han, J., Song, M. Y., Han, Y. H., Cha, S. H., & Goo Kang, S. (2023). Albumin-binding recombinant human IL-18BP ameliorates macrophage activation syndrome and atopic dermatitis via direct IL-18 inactivation. Cytokine, 172, 156413. [CrossRef]

- Janho Dit Hreich, S., Humbert, O., Pacé-Loscos, T., Schiappa, R., Juhel, T., Ilié, M., Ferrari, V., Benzaquen, J., Hofman, P., & Vouret-Craviari, V. (2024). Plasmatic Inactive IL-18 Predicts a Worse Overall Survival for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Early Metabolic Progression after Immunotherapy Initiation. Cancers (Basel), 16(12). [CrossRef]

- Jarret, A., Jackson, R., Duizer, C., Healy, M. E., Zhao, J., Rone, J. M., Bielecki, P., Sefik, E., Roulis, M., Rice, T., Sivanathan, K. N., Zhou, T., Solis, A. G., Honcharova-Biletska, H., Vélez, K., Hartner, S., Low, J. S., Qu, R., de Zoete, M. R., . . . Flavell, R. A. (2020). Enteric Nervous System-Derived IL-18 Orchestrates Mucosal Barrier Immunity. Cell, 180(1), 50-63.e12. [CrossRef]

- Jun, H. T., Deborah A. Witherden, D. A., Elliot, E. K., Chidester, C. M., Willen, M., Peguero, B. R., Chai, M., Horlick, R. A. and King, D. J. (2023). Discovery and evaluation of an anti-IL18BP antibody to enhance anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Res 83. [CrossRef]

- .

- Kaplanski, G. (2018). Interleukin-18: Biological properties and role in disease pathogenesis. Immunol Rev, 281(1), 138-153. [CrossRef]

- Kaser, A., Novick, D., Rubinstein, M., Siegmund, B., Enrich, B., Koch, R. O., Vogel, W., Kim, S. H., Dinarello, C. A., & Tilg, H. (2002). Interferon-alpha induces interleukin-18 binding protein in chronic hepatitis C patients. Clin Exp Immunol, 129(2), 332-338. [CrossRef]

- Kass, D. J. (2011). Cytokine-like factor 1 (CLF1): life after development? Cytokine, 55(3), 325-329. [CrossRef]

- Kiltz, U., Kiefer, D., Braun, J., Schiffrin, E. J., Girard-Guyonvarc'h, C., & Gabay, C. (2020). Prolonged treatment with Tadekinig alfa in adult-onset Still's disease. Ann Rheum Dis, 79(1), e10. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H., Eisenstein, M., Reznikov, L., Fantuzzi, G., Novick, D., Rubinstein, M., & Dinarello, C. A. (2000). Structural requirements of six naturally occurring isoforms of the IL-18 binding protein to inhibit IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 97(3), 1190-1195. [CrossRef]

- Konishi, H., Tsutsui, H., Murakami, T., Yumikura-Futatsugi, S., Yamanaka, K., Tanaka, M., Iwakura, Y., Suzuki, N., Takeda, K., Akira, S., Nakanishi, K., & Mizutani, H. (2002). IL-18 contributes to the spontaneous development of atopic dermatitis-like inflammatory skin lesion independently of IgE/stat6 under specific pathogen-free conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 99(17), 11340-11345. [CrossRef]

- Korotaeva, A. A., Samoilova, E. V., Pogosova, N. V., Fesenko, A. G., Evchenko, S. V., & Paleev, F. N. (2024). Ratios between the Levels of IL-18, Free IL-18, and IL-1β-Binding Protein Depending on the Severity and Outcome of COVID-19. Bull Exp Biol Med, 176(4), 423-427. [CrossRef]

- Krei, J. M., Møller, H. J., & Larsen, J. B. (2021). The role of interleukin-18 in the diagnosis and monitoring of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome - a systematic review. Clin Exp Immunol, 203(2), 174-182. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B. A., Lim, E. Y., Metaxaki, M., Jackson, S., Mactavous, L., Lyons, P. A., Doffinger, R., Bradley, J. R., Smith, K. G. C., Sinclair, J., Matheson, N. J., Lehner, P. J., Sithole, N., & Wills, M. R. (2024). Spontaneous, persistent, T cell-dependent IFN-γ release in patients who progress to Long Covid. Sci Adv, 10(8), eadi9379. [CrossRef]

- Kudela, H., Drynda, S., Lux, A., Horneff, G., & Kekow, J. (2019). Comparative study of Interleukin-18 (IL-18) serum levels in adult onset Still's disease (AOSD) and systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) and its use as a biomarker for diagnosis and evaluation of disease activity. BMC Rheumatol, 3, 4. [CrossRef]

- Lage, S. L., Ramaswami, R., Rocco, J. M., Rupert, A., Davis, D. A., Lurain, K., Manion, M., Whitby, D., Yarchoan, R., & Sereti, I. (2024). Inflammasome activation in patients with Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated diseases. Blood, 144(14), 1496-1507. [CrossRef]

- Landy, E., Carol, H., Ring, A., & Canna, S. (2024). Biological and clinical roles of IL-18 in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 20(1), 33-47. [CrossRef]

- Levy, M., Thaiss, C. A., Zeevi, D., Dohnalová, L., Zilberman-Schapira, G., Mahdi, J. A., David, E., Savidor, A., Korem, T., Herzig, Y., Pevsner-Fischer, M., Shapiro, H., Christ, A., Harmelin, A., Halpern, Z., Latz, E., Flavell, R. A., Amit, I., Segal, E., & Elinav, E. (2015). Microbiota-Modulated Metabolites Shape the Intestinal Microenvironment by Regulating NLRP6 Inflammasome Signaling. Cell, 163(6), 1428-1443. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Qian, W., Wei, X., Narasimhan, H., Wu, Y., Arish, M., Cheon, I. S., Tang, J., de Almeida Santos, G., Li, Y., Sharifi, K., Kern, R., Vassallo, R., & Sun, J. (2024). Comparative single-cell analysis reveals IFN-γ as a driver of respiratory sequelae after acute COVID-19. Sci Transl Med, 16(756), eadn0136. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D. A., Schischlik, F., Shao, L., Steinberg, S. M., Yates, B., Wang, H. W., Wang, Y., Inglefield, J., Dulau-Florea, A., Ceppi, F., Hermida, L. C., Stringaris, K., Dunham, K., Homan, P., Jailwala, P., Mirazee, J., Robinson, W., Chisholm, K. M., Yuan, C., . . . Shah, N. N. (2021). Characterization of HLH-like manifestations as a CRS variant in patients receiving CD22 CAR T cells. Blood, 138(24), 2469-2484. [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, B., Unmuth, L., Arras, P., Becker, S., Bauer, C., Toleikis, L., Krah, S., Doerner, A., Yanakieva, D., Boje, A. S., Klausz, K., Peipp, M., Siegmund, V., Evers, A., Kolmar, H., Pekar, L., & Zielonka, S. (2023). Generation and engineering of potent single domain antibody-based bispecific IL-18 mimetics resistant to IL-18BP decoy receptor inhibition. MAbs, 15(1), 2236265. [CrossRef]

- Manzo Margiotta, F., Gambino, G., Pratesi, F., Michelucci, A., Pisani, F., Rossi, L., Dini, V., Romanelli, M., & Migliorini, P. (2024). Interleukin-1 family cytokines and soluble receptors in hidradenitis suppurativa. Exp Dermatol, 33(9), e15179. [CrossRef]

- Marx, J. L. (1988). Cytokines are two-edged swords in disease. Science, 239(4837), 257-258. [CrossRef]

- Mazodier, K., Marin, V., Novick, D., Farnarier, C., Robitail, S., Schleinitz, N., Veit, V., Paul, P., Rubinstein, M., Dinarello, C. A., Harlé, J. R., & Kaplanski, G. (2005). Severe imbalance of IL-18/IL-18BP in patients with secondary hemophagocytic syndrome. Blood, 106(10), 3483-3489. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P., Samanta, R. J., Wick, K., Coll, R. C., Mawhinney, T., McAleavey, P. G., Boyle, A. J., Conlon, J., Shankar-Hari, M., Rogers, A., Calfee, C. S., Matthay, M. A., Summers, C., Chambers, R. C., McAuley, D. F., & O'Kane, C. M. (2024). Elevated ferritin, mediated by IL-18 is associated with systemic inflammation and mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Thorax, 79(3), 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Menachem, A., Alteber, Z., Cojocaru, G., Fridman Kfir, T., Blat, D., Leiderman, O., Galperin, M., Sever, L., Cohen, N., Cohen, K., Granit, R. Z., Vols, S., Frenkel, M., Soffer, L., Meyer, K., Menachem, K., Galon Tilleman, H., Morein, D., Borukhov, I., . . . Ophir, E. (2024). Unleashing Natural IL18 Activity Using an Anti-IL18BP Blocker Induces Potent Immune Stimulation and Antitumor Effects. Cancer Immunol Res, 12(6), 687-703. [CrossRef]

- Mertens, R. T., Misra, A., Xiao, P., Baek, S., Rone, J. M., Mangani, D., Sivanathan, K. N., Arojojoye, A. S., Awuah, S. G., Lee, I., Shi, G. P., Petrova, B., Brook, J. R., Anderson, A. C., Flavell, R. A., Kanarek, N., Hemberg, M., & Nowarski, R. (2024). A metabolic switch orchestrated by IL-18 and the cyclic dinucleotide cGAMP programs intestinal tolerance. Immunity, 57(9), 2077-2094.e2012. [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, G., Pallone, F., & Macdonald, T. T. (2010). Interleukin-25: a two-edged sword in the control of immune-inflammatory responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 21(6), 471-475. [CrossRef]

- Moore, A. R., Pienkos, S. M., Sinha, P., Guan, J., O'Kane, C. M., Levitt, J. E., Wilson, J. G., Shankar-Hari, M., Matthay, M. A., Calfee, C. S., Baron, R. M., McAuley, D. F., & Rogers, A. J. (2023). Elevated Plasma Interleukin-18 Identifies High-Risk Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Patients not Distinguished by Prior Latent Class Analyses Using Traditional Inflammatory Cytokines: A Retrospective Analysis of Two Randomized Clinical Trials. Crit Care Med, 51(12), e269-e274. [CrossRef]

- Morris, K. R., Brodkin, H., Economides, K., Hicklin, D. J., LePrevost, J., Nagy-Domonkos, C., Nirschl, C., Salmeron, A., Seidel-Dugan, C., Spencer, C., Steuert, Z. and William M. Winston, W. M. (2024). Discovery of WTX-518, an IL-18 pro-drug that is conditionally activated within the tumor microenvironment and induces regressions in mouse tumor models. Cancer Res 84. [CrossRef]

- Mühl, H., & Bachmann, M. (2019). IL-18/IL-18BP and IL-22/IL-22BP: Two interrelated couples with therapeutic potential. Cell Signal, 63, 109388. [CrossRef]

- Mühl, H., Kämpfer, H., Bosmann, M., Frank, S., Radeke, H., & Pfeilschifter, J. (2000). Interferon-gamma mediates gene expression of IL-18 binding protein in nonleukocytic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 267(3), 960-963. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K., Okamura, H., Wada, M., Nagata, K., & Tamura, T. (1989). Endotoxin-induced serum factor that stimulates gamma interferon production. Infect Immun, 57(2), 590-595. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S., Otani, T., Okura, R., Ijiri, Y., Motoda, R., Kurimoto, M., & Orita, K. (2000). Expression and responsiveness of human interleukin-18 receptor (IL-18R) on hematopoietic cell lines. Leukemia, 14(6), 1052-1059. [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K., Yoshimoto, T., Tsutsui, H., & Okamura, H. (2001). Interleukin-18 is a unique cytokine that stimulates both Th1 and Th2 responses depending on its cytokine milieu. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 12(1), 53-72. [CrossRef]

- Nasser, S. M. T., Rana, A. A., Doffinger, R., Kafizas, A., Khan, T. A., & Nasser, S. (2023). Elevated free interleukin-18 associated with severity and mortality in prospective cohort study of 206 hospitalised COVID-19 patients. Intensive Care Med Exp, 11(1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Netea, M. G., Joosten, L. A., Lewis, E., Jensen, D. R., Voshol, P. J., Kullberg, B. J., Tack, C. J., van Krieken, H., Kim, S. H., Stalenhoef, A. F., van de Loo, F. A., Verschueren, I., Pulawa, L., Akira, S., Eckel, R. H., Dinarello, C. A., van den Berg, W., & van der Meer, J. W. (2006). Deficiency of interleukin-18 in mice leads to hyperphagia, obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Med, 12(6), 650-656. [CrossRef]

- Nisthal, A., Lee, S., Bonzon, C., Love, R., Avery, K., Rashid, R., Lertkiatmongkol, P., Rodriguez, N., Karki ,S., Barlow, N., Chu, S., Moore, G. and Desjarlais, J. . (2022). XmAb143, an engineered IL18 heterodimeric Fc-fusion, features improved stability, reduced potency, and insensitivity to IL18BP. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Novick, D. (2022). Nine receptors and binding proteins, four drugs, and one woman: Historical and personal perspectives. Front Drug Discovery. [CrossRef]

- Novick, D. (2023). A natural goldmine of binding proteins and soluble receptors simplified their translation to blockbuster drugs, all in one decade. Front Immunol, 14, 1151620. [CrossRef]

- Novick, D., Kim, S., Kaplanski, G., & Dinarello, C. A. (2013). Interleukin-18, more than a Th1 cytokine. Semin Immunol, 25(6), 439-448. [CrossRef]

- Novick, D., Kim, S. H., Fantuzzi, G., Reznikov, L. L., Dinarello, C. A., & Rubinstein, M. (1999). Interleukin-18 binding protein: a novel modulator of the Th1 cytokine response. Immunity, 10(1), 127-136. [CrossRef]

- Novick, D., & Rubinstein, M. (2007). The tale of soluble receptors and binding proteins: from bench to bedside. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 18(5-6), 525-533. [CrossRef]

- Novick, D., Schwartsburd, B., Pinkus, R., Suissa, D., Belzer, I., Sthoeger, Z., Keane, W. F., Chvatchko, Y., Kim, S. H., Fantuzzi, G., Dinarello, C. A., & Rubinstein, M. (2001). A novel IL-18BP ELISA shows elevated serum IL-18BP in sepsis and extensive decrease of free IL-18. Cytokine, 14(6), 334-342. [CrossRef]

- Nowarski, R., Jackson, R., Gagliani, N., de Zoete, M. R., Palm, N. W., Bailis, W., Low, J. S., Harman, C. C., Graham, M., Elinav, E., & Flavell, R. A. (2015). Epithelial IL-18 Equilibrium Controls Barrier Function in Colitis. Cell, 163(6), 1444-1456. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, C. R., Abraham, E., Ancukiewicz, M., & Edelstein, C. L. (2005). Urine IL-18 is an early diagnostic marker for acute kidney injury and predicts mortality in the intensive care unit. J Am Soc Nephrol, 16(10), 3046-3052. [CrossRef]

- Peleman, C., Van Coillie, S., Ligthart, S., Choi, S. M., De Waele, J., Depuydt, P., Benoit, D., Schaubroeck, H., Francque, S. M., Dams, K., Jacobs, R., Robert, D., Roelandt, R., Seurinck, R., Saeys, Y., Rajapurkar, M., Jorens, P. G., Hoste, E., & Vanden Berghe, T. (2023). Ferroptosis and pyroptosis signatures in critical COVID-19 patients. Cell Death Differ, 30(9), 2066-2077. [CrossRef]

- Posey, A. D., Jr., Young, R. M., & June, C. H. (2024). Future perspectives on engineered T cells for cancer. Trends Cancer, 10(8), 687-695. [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S., Hackett, C. S., & Brentjens, R. J. (2020). Engineering strategies to overcome the current roadblocks in CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 17(3), 147-167. [CrossRef]

- Rex, D. A. B., Agarwal, N., Prasad, T. S. K., Kandasamy, R. K., Subbannayya, Y., & Pinto, S. M. (2020). A comprehensive pathway map of IL-18-mediated signalling. J Cell Commun Signal, 14(2), 257-266. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M. J., Kirkwood, J. M., Logan, T. F., Koch, K. M., Kathman, S., Kirby, L. C., Bell, W. N., Thurmond, L. M., Weisenbach, J., & Dar, M. M. (2008). A dose-escalation study of recombinant human interleukin-18 using two different schedules of administration in patients with cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 14(11), 3462-3469. [CrossRef]

- Romberg, N., Al Moussawi, K., Nelson-Williams, C., Stiegler, A. L., Loring, E., Choi, M., Overton, J., Meffre, E., Khokha, M. K., Huttner, A. J., West, B., Podoltsev, N. A., Boggon, T. J., Kazmierczak, B. I., & Lifton, R. P. (2014). Mutation of NLRC4 causes a syndrome of enterocolitis and autoinflammation. Nat Genet, 46(10), 1135-1139. [CrossRef]

- Romberg, N., Vogel, T. P., & Canna, S. W. (2017). NLRC4 inflammasomopathies. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 17(6), 398-404. [CrossRef]

- Rusiñol, L., & Puig, L. (2024). A Narrative Review of the IL-18 and IL-37 Implications in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis: Prospective Treatment Targets. Int J Mol Sci, 25(15). [CrossRef]

- Sareneva, T., Julkunen, I., & Matikainen, S. (2000). IFN-alpha and IL-12 induce IL-18 receptor gene expression in human NK and T cells. J Immunol, 165(4), 1933-1938. [CrossRef]

- Schroder, K., & Tschopp, J. (2010). The inflammasomes. Cell, 140(6), 821-832. [CrossRef]

- Sefik, E., Qu, R., Junqueira, C., Kaffe, E., Mirza, H., Zhao, J., Brewer, J. R., Han, A., Steach, H. R., Israelow, B., Blackburn, H. N., Velazquez, S. E., Chen, Y. G., Halene, S., Iwasaki, A., Meffre, E., Nussenzweig, M., Lieberman, J., Wilen, C. B., . . . Flavell, R. A. (2022). Inflammasome activation in infected macrophages drives COVID-19 pathology. Nature, 606(7914), 585-593. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M. (2021). Macrophage activation syndrome in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Immunol Med, 44(4), 237-245. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M., Inoue, N., Mizuta, M., Nakagishi, Y., & Yachie, A. (2018). Characteristic elevation of soluble TNF receptor II : I ratio in macrophage activation syndrome with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol, 191(3), 349-355. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M., Takei, S., Mori, M., & Yachie, A. (2022). Pathogenic roles and diagnostic utility of interleukin-18 in autoinflammatory diseases. Front Immunol, 13, 951535. [CrossRef]

- Simonet, W. S., Lacey, D. L., Dunstan, C. R., Kelley, M., Chang, M. S., Lüthy, R., Nguyen, H. Q., Wooden, S., Bennett, L., Boone, T., Shimamoto, G., DeRose, M., Elliott, R., Colombero, A., Tan, H. L., Trail, G., Sullivan, J., Davy, E., Bucay, N., . . . Boyle, W. J. (1997). Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell, 89(2), 309-319. [CrossRef]

- Smith, V. P., Bryant, N. A., & Alcamí, A. (2000). Ectromelia, vaccinia and cowpox viruses encode secreted interleukin-18-binding proteins. J Gen Virol, 81(Pt 5), 1223-1230. [CrossRef]

- Snell, L. M., McGaha, T. L., & Brooks, D. G. (2017). Type I Interferon in Chronic Virus Infection and Cancer. Trends Immunol, 38(8), 542-557. [CrossRef]

- Steinman, L. (2007). A brief history of T(H)17, the first major revision in the T(H)1/T(H)2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage. Nat Med, 13(2), 139-145. [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, J., Gerson, J. N., Landsburg, D. J., Chong, E. A., Barta, S. K., Nasta, S.D., Ruella, M.,Hexner, E. O., Marshall, A. et al. and June, C. H. (2022). Interleukin-18 Secreting Autologous Anti-CD19 CAR T-Cells (huCART19-IL18) in Patients with Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas Relapsed or Refractory to Prior CAR T-Cell Therapy. Blood, 140, 4612-4614. [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, J., Landsburg, D. J., Dwivedy Nasta, S. D., Barta, S. K., Chong, E. A., Lariviere, M. J., Shea, J., Cervini, S., Hexner, E. O., Marshall, A., et al. and June, C. H. . (2024). Safety and efficacy of armored huCART19-IL18 in patients with relapsed/refractory lymphomas that progressed after anti-CD19 CAR T cells. Journal of Clinical Oncology 42. [CrossRef]

- Tak, P. P., Bacchi, M., & Bertolino, M. (2006). Pharmacokinetics of IL-18 binding protein in healthy volunteers and subjects with rheumatoid arthritis or plaque psoriasis. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet, 31(2), 109-116. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, N., Kimura, T., Arita, K., Ariyoshi, M., Ohnishi, H., Yamamoto, T., Zuo, X., Maenaka, K., Park, E. Y., Kondo, N., Shirakawa, M., Tochio, H., & Kato, Z. (2014). The structural basis for receptor recognition of human interleukin-18. Nat Commun, 5, 5340. [CrossRef]

- Uslu, U., Sun, L., Castelli, S., Finck, A. V., Assenmacher, C. A., Young, R. M., Chen, Z. J., & June, C. H. (2024). The STING agonist IMSA101 enhances chimeric antigen receptor T cell function by inducing IL-18 secretion. Nat Commun, 15(1), 3933. [CrossRef]

- Volfovitch, Y., Tsur, A. M., Gurevitch, M., Novick, D., Rabinowitz, R., Mandel, M., Achiron, A., Rubinstein, M., Shoenfeld, Y., & Amital, H. (2022). The intercorrelations between blood levels of ferritin, sCD163, and IL-18 in COVID-19 patients and their association to prognosis. Immunol Res, 70(6), 817-828. [CrossRef]

- Wada, T., Kanegane, H., Ohta, K., Katoh, F., Imamura, T., Nakazawa, Y., Miyashita, R., Hara, J., Hamamoto, K., Yang, X., Filipovich, A. H., Marsh, R. A., & Yachie, A. (2014). Sustained elevation of serum interleukin-18 and its association with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in XIAP deficiency. Cytokine, 65(1), 74-78. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. (2024). Interleukin-18 binding protein: Biological properties and roles in human and animal immune regulation (Review). Biomed Rep, 20(6), 87. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Wang, L., Wen, X., Zhang, L., Jiang, X., & He, G. (2023). Interleukin-18 and IL-18BP in inflammatory dermatological diseases. Front Immunol, 14, 955369. [CrossRef]

- Washburn, K. K., Zappitelli, M., Arikan, A. A., Loftis, L., Yalavarthy, R., Parikh, C. R., Edelstein, C. L., & Goldstein, S. L. (2008). Urinary interleukin-18 is an acute kidney injury biomarker in critically ill children. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 23(2), 566-572. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E. S., Girard-Guyonvarc'h, C., Holzinger, D., de Jesus, A. A., Tariq, Z., Picarsic, J., Schiffrin, E. J., Foell, D., Grom, A. A., Ammann, S., Ehl, S., Hoshino, T., Goldbach-Mansky, R., Gabay, C., & Canna, S. W. (2018). Interleukin-18 diagnostically distinguishes and pathogenically promotes human and murine macrophage activation syndrome. Blood, 131(13), 1442-1455. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Sakorafas, P., Miller, R., McCarthy, D., Scesney, S., Dixon, R., & Ghayur, T. (2003). IL-18 receptor beta-induced changes in the presentation of IL-18 binding sites affect ligand binding and signal transduction. J Immunol, 170(11), 5571-5577. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Craft, M. L., Wang, P., Wyburn, K. R., Chen, G., Ma, J., Hambly, B., & Chadban, S. J. (2008). IL-18 contributes to renal damage after ischemia-reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol, 19(12), 2331-2341. [CrossRef]

- Xia, S., Zhang, Z., Magupalli, V. G., Pablo, J. L., Dong, Y., Vora, S. M., Wang, L., Fu, T. M., Jacobson, M. P., Greka, A., Lieberman, J., Ruan, J., & Wu, H. (2021). Gasdermin D pore structure reveals preferential release of mature interleukin-1. Nature, 593(7860), 607-611. [CrossRef]

- Yamanishi, K., Hata, M., Gamachi, N., Watanabe, Y., Yamanishi, C., Okamura, H., & Matsunaga, H. (2023). Molecular Mechanisms of IL18 in Disease. Int J Mol Sci, 24(24). [CrossRef]

- Yasin, S., Fall, N., Brown, R. A., Henderlight, M., Canna, S. W., Girard-Guyonvarc'h, C., Gabay, C., Grom, A. A., & Schulert, G. S. (2020). IL-18 as a biomarker linking systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and macrophage activation syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford), 59(2), 361-366. [CrossRef]

- Yasin, S., Solomon, K., Canna, S. W., Girard-Guyonvarc'h, C., Gabay, C., Schiffrin, E., Sleight, A., Grom, A. A., & Schulert, G. S. (2020). IL-18 as therapeutic target in a patient with resistant systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and recurrent macrophage activation syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford), 59(2), 442-445. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K., Nakanishi, K., & Tsutsui, H. (2019). Interleukin-18 in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci, 20(3). [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, T., Takeda, K., Tanaka, T., Ohkusu, K., Kashiwamura, S., Okamura, H., Akira, S., & Nakanishi, K. (1998). IL-12 up-regulates IL-18 receptor expression on T cells, Th1 cells, and B cells: synergism with IL-18 for IFN-gamma production. J Immunol, 161(7), 3400-3407.

- Young, R. M., Engel, N. W., Uslu, U., Wellhausen, N., & June, C. H. (2022). Next-Generation CAR T-cell Therapies. Cancer Discov, 12(7), 1625-1633. [CrossRef]

- Yu, P., Zhang, X., Liu, N., Tang, L., Peng, C., & Chen, X. (2021). Pyroptosis: mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 6(1), 128. [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, M. R., & Merlino, G. (2011). The two faces of interferon-γ in cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 17(19), 6118-6124. [CrossRef]

- Zenewicz, L. A. (2021). IL-22 Binding Protein (IL-22BP) in the Regulation of IL-22 Biology. Front Immunol, 12, 766586. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D., Mohapatra, G., Kern, L., He, Y., Shmueli, M. D., Valdés-Mas, R., Kolodziejczyk, A. A., Próchnicki, T., Vasconcelos, M. B., Schorr, L., Hertel, F., Lee, Y. S., Rufino, M. C., Ceddaha, E., Shimshy, S., Hodgetts, R. J., Dori-Bachash, M., Kleimeyer, C., Goldenberg, K., . . . Elinav, E. (2023). Epithelial Nlrp10 inflammasome mediates protection against intestinal autoinflammation. Nat Immunol, 24(4), 585-594. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T., Damsky, W., Weizman, O. E., McGeary, M. K., Hartmann, K. P., Rosen, C. E., Fischer, S., Jackson, R., Flavell, R. A., Wang, J., Sanmamed, M. F., Bosenberg, M. W., & Ring, A. M. (2020). IL-18BP is a secreted immune checkpoint and barrier to IL-18 immunotherapy. Nature, 583(7817), 609-614. [CrossRef]

| Drug Name | Company | Description | Indications | Clinical Trials | Clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tadekinig alfa | AB2 Bio Ltd. | Recombinant IL-18BP | -NLRC4 mutation -XIAP deficiency |

Phase III completed |

NCT03113760 |

| Tadekinig alfa | AB2 Bio Ltd. | Recombinant IL-18BP | AOSD | Phase II completed |

NCT02398435 |

| GSK 1070806 | GlaxoSmithKline | Humanized anti-IL-18 IgG1 monoclonal antibody | Atopic Dermatitis | Phase II | NCT05999799 |

| Camoteskimab | Apollo Therapeutics | Human anti IL-18 IgG1 monoclonal antibody | Atopic Dermatitis | Phase II | NCT06436183 |

| MAS825 | Novartis | Anti IL-18 and IL-1 Bispecific Antibody | -NLRC4 mutation -XIAP deficiency |

Phase II | NLRC4-GOF, NCT04641442 |

| Drug Name | Company | Description | Indications | Clinical Trials | Clinical trial number or Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST-067 | Simcha Therapeutics | A variant of IL-18 resistant to IL-18BP monotherapy or combined with anti PD-1 | Variety of solid tumors | Phase Ia/II | NCT04787042 |

| XmAb143 | Xencor | Modified IL-18 fused to Fc and resistant to IL-18BP | Cancer | Pre-clinical | Nishtal et al., 2022 |

| BPT 567/PD1-IL18-Fc | Bright Peak Therapeutics | A conjugate of IL-18 variant resistant to IL-18BP with anti-PD-1 antibody | Cancer | Pre-clinical | Codarri Deak et al., 2022 |

| WTX 518 | Werewolf Therapeutics | Modified and conditionally activated IL-18 resistant to IL-18BP monotherapy or combined with anti PD-1 | Cancer | Pre- clinical | Morris et al., 2024 |

| SCA | Merck Healthcare KGaA and Synthekine | IL-18 mimetic agonist resistant to IL-18BP | Cancer | Pre- clinical | Lipinski et al., 2023 |

| COM503 | Compugen and Gilead | Anti IL-18BP fully human antibody | Mouse breast cancer, colorectal cancer and melanoma | Pre- clinical and Phase I | Menachem et al., 2024 |

| LASN500 | Lassen Therapeutics | Anti IL-18BP Antibody monotherapy or combined with anti PD-1 | Cancer | Pre- clinical | Jun et al., 2023 |

| Drug Name | Company | Description | Indications | Clinical Trials | Clinical trial number or Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HuCART19-IL18 | Gilead | Anti CD19 construct secreting IL-18 | Lymphoma | Phase I | Svoboda et al. 2022; Svoboda et al., 2024 |

| GPC3-IL18 | Eutilex Co. Ltd. | Targeted hepatocellular carcinoma tumor (HCC) marker, Glypican-3 (GPC3) and an IL-18-secreting CAR T cell therapy | Hepatocellular carcinoma tumor and non-small cell lung carcinoma | Phase I | |

| CD371-YSNVZIL-18 | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | Combination of acute myelogenous leukemia targeted marker and IL-18-secreting construct | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Phase I | NCT06017258 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).