Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

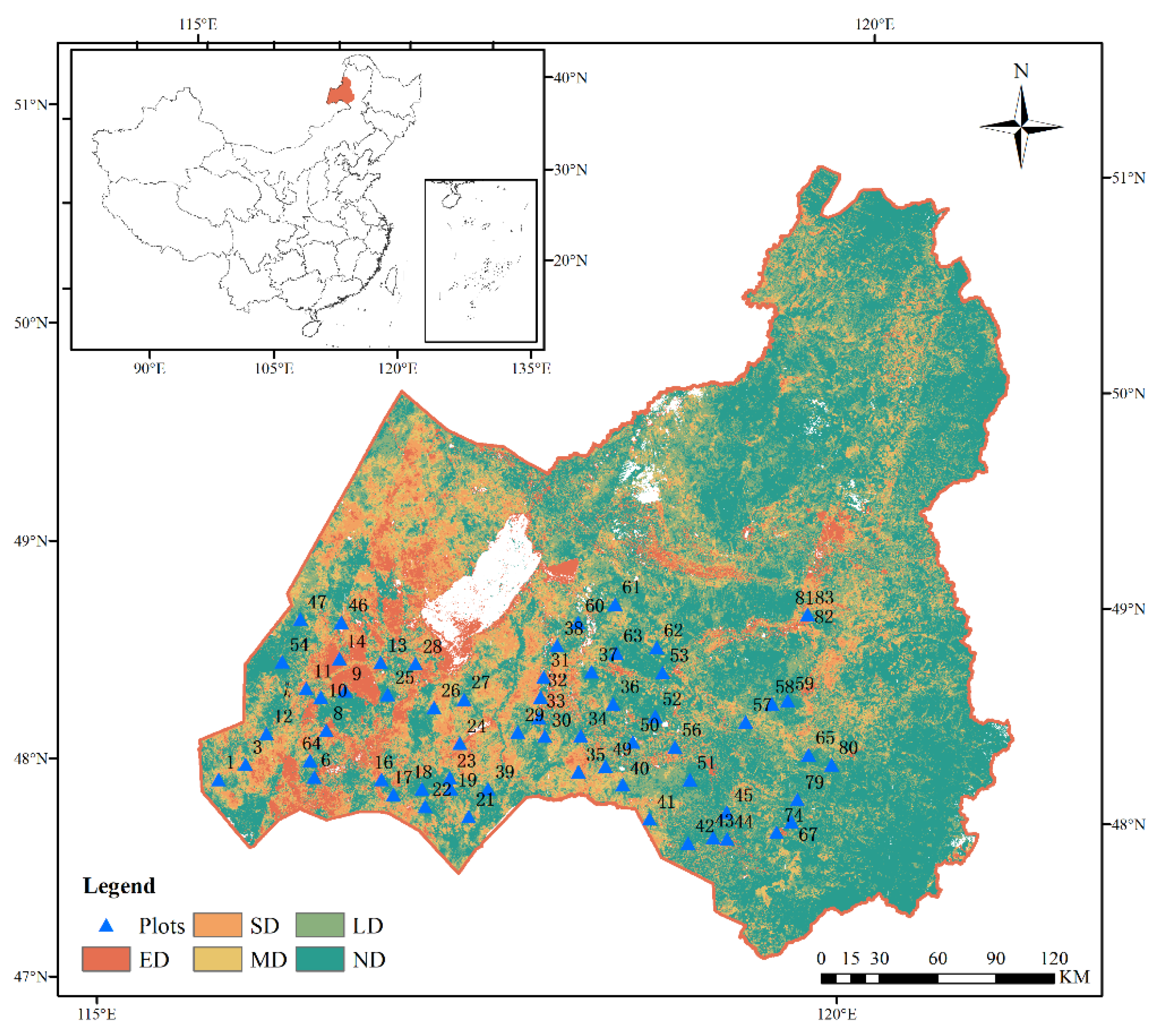

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Grassland Degradation Evaluation

2.3. Vegetation Sampling

- (1)

- Importance value

- (2)

- Shannon–Wiener Index

2.4. Soil Sampling and Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Vegetation Characteristics in Grasslands with Different Levels of Degradation

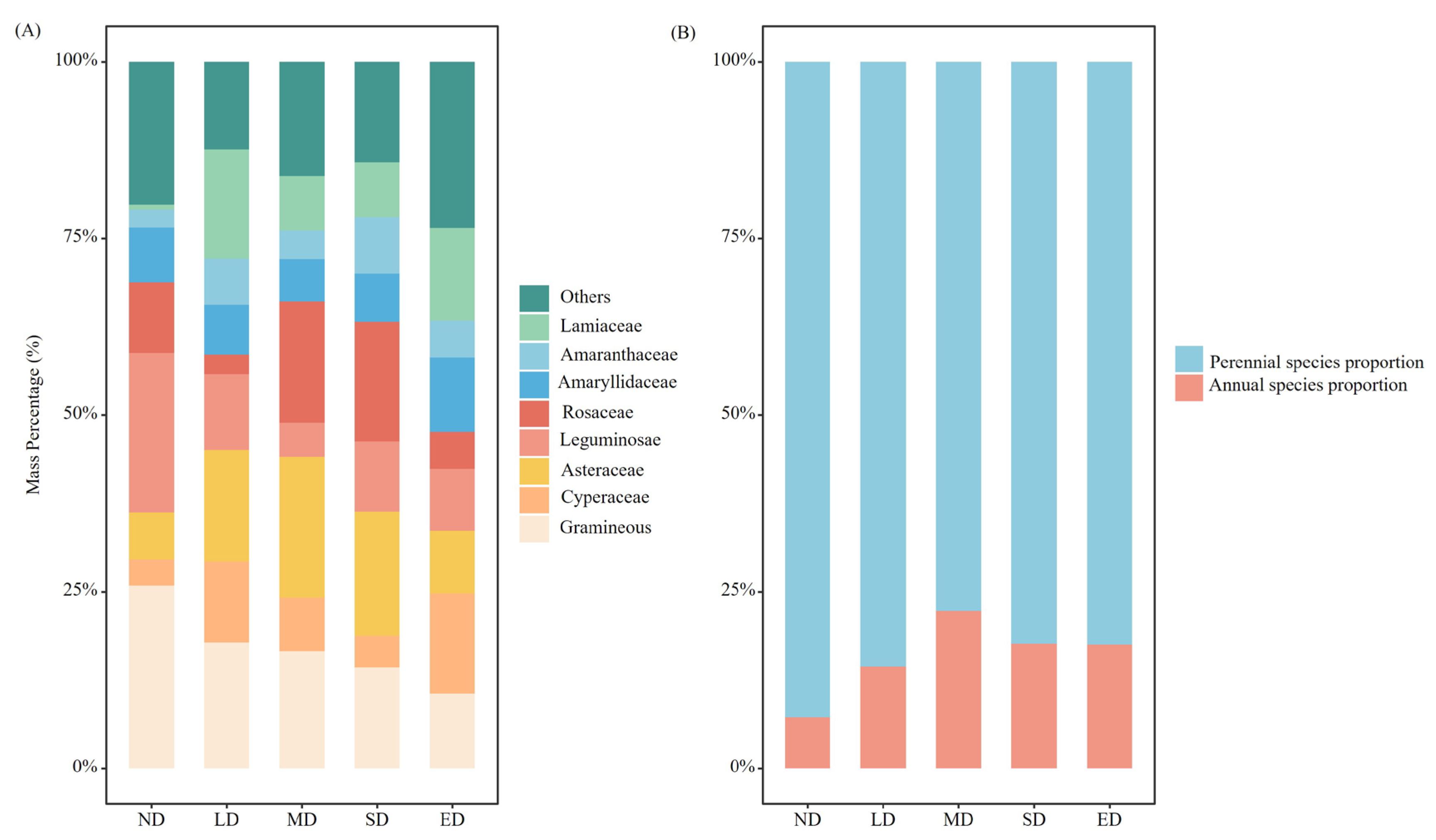

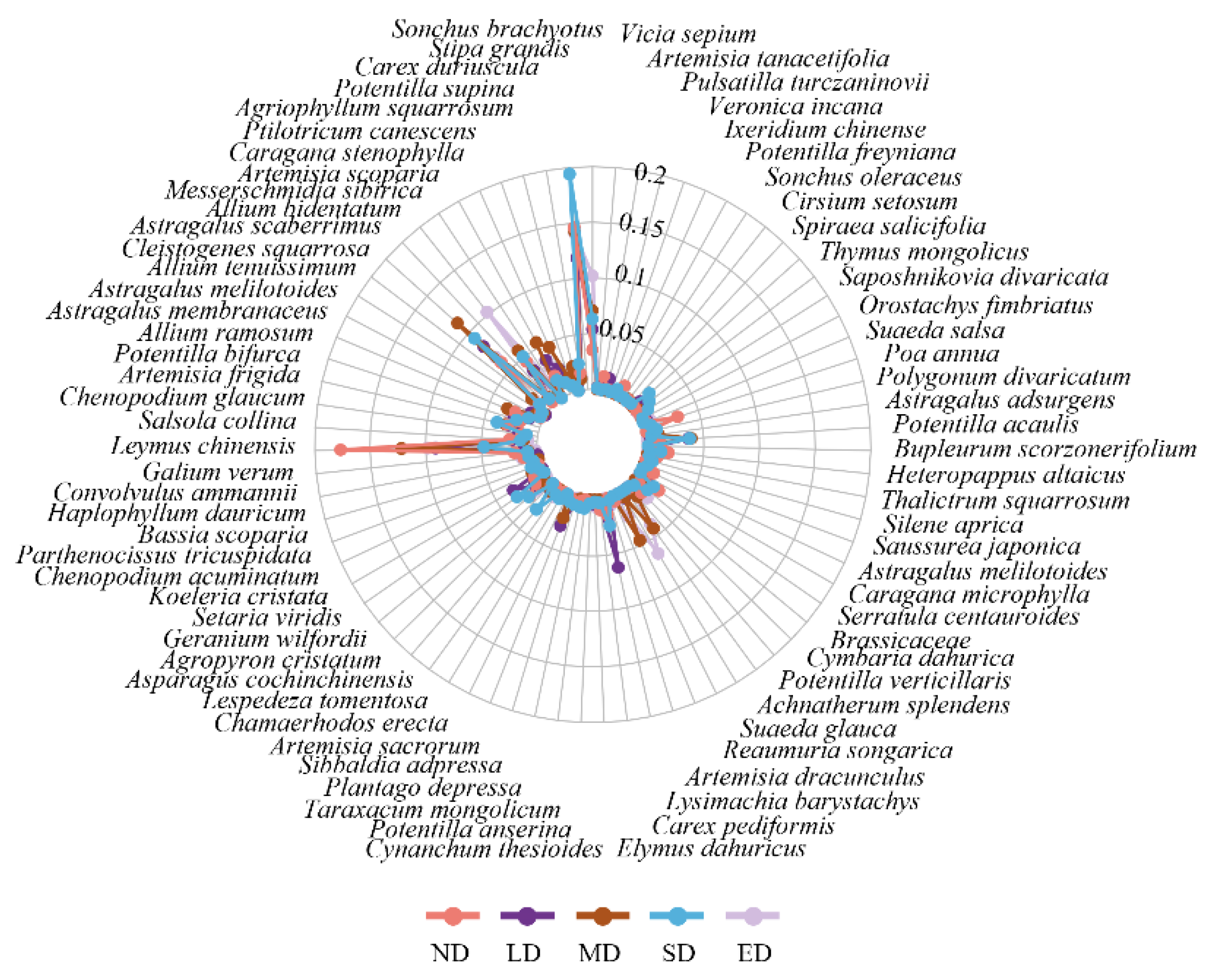

3.1.1. Plant Community Composition

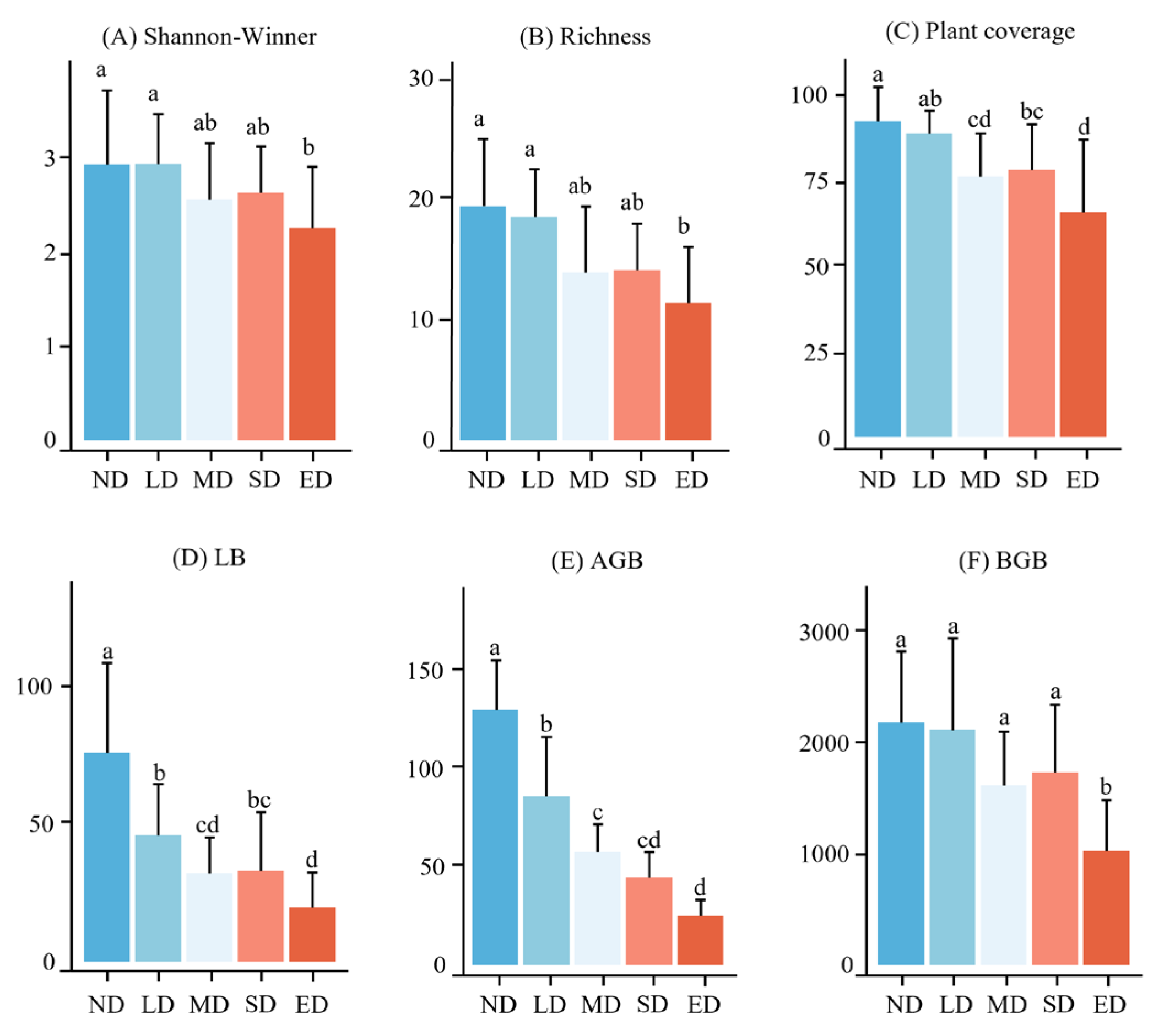

3.1.2. Plant Diversity and Biomass

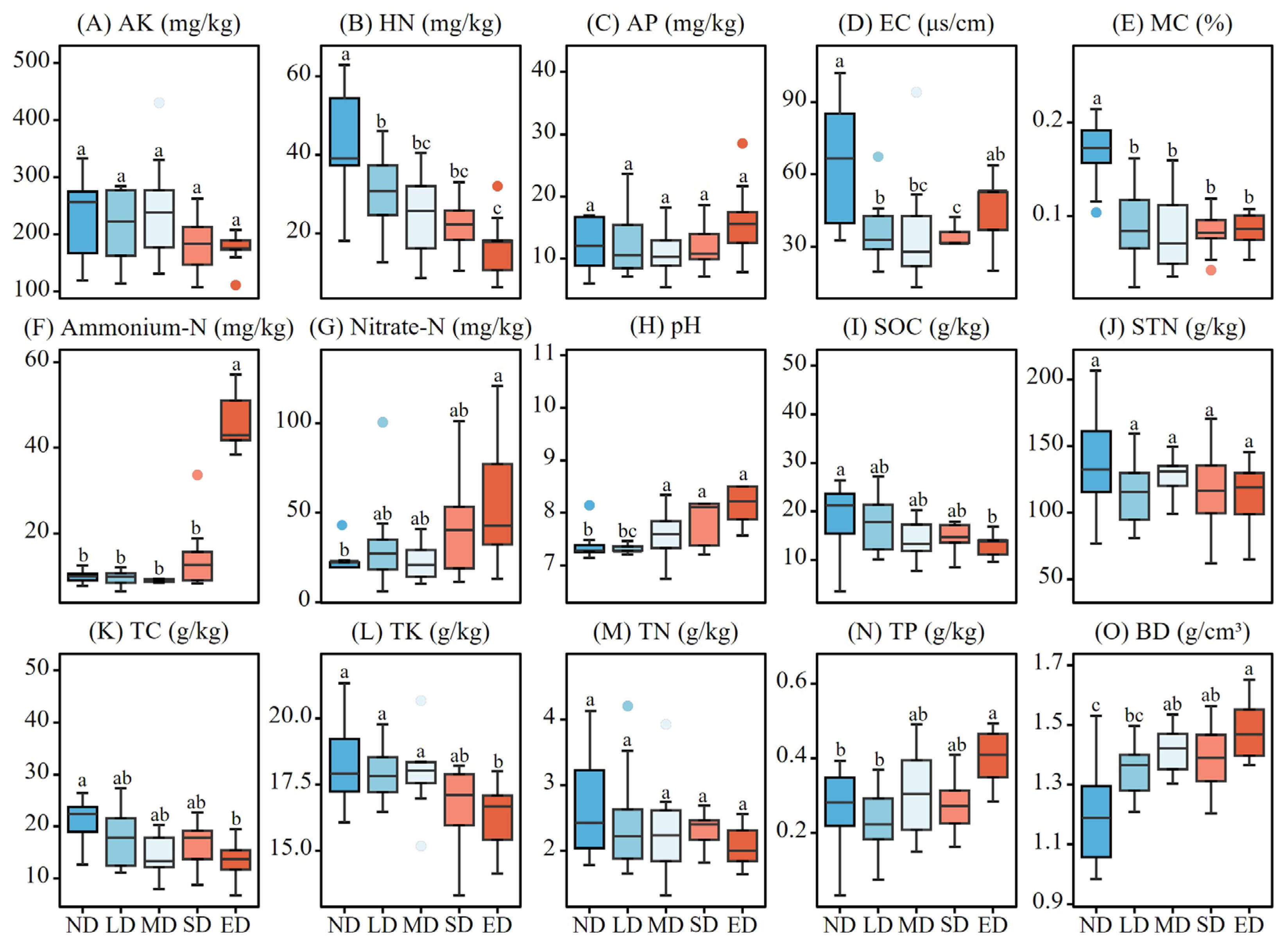

3.2. Soil Nutrient Characteristics in Grasslands with Different Levels of Degradation

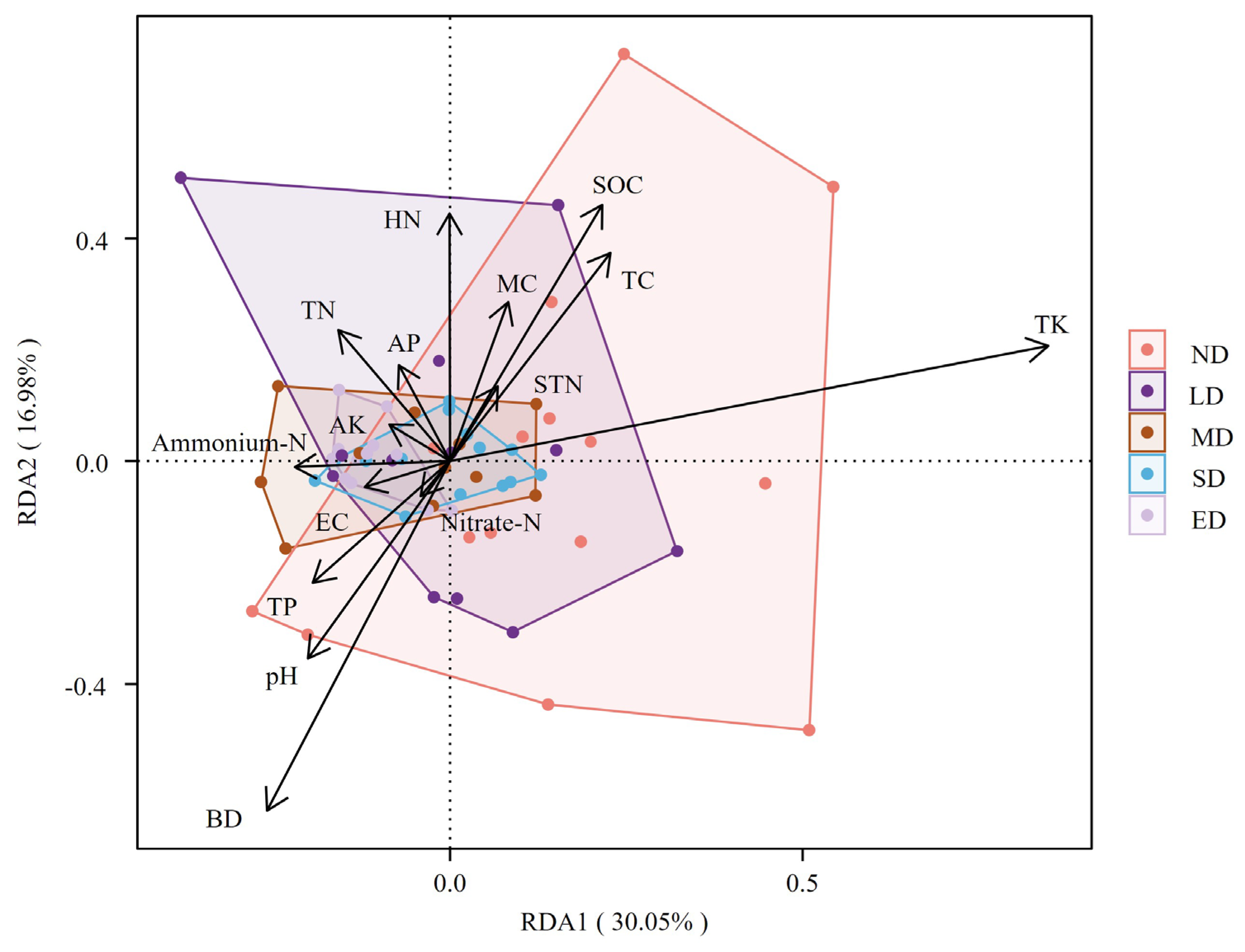

3.3. Soil Nutrient Effects on Plant Biomass in Grasslands with Different Degradation Levels

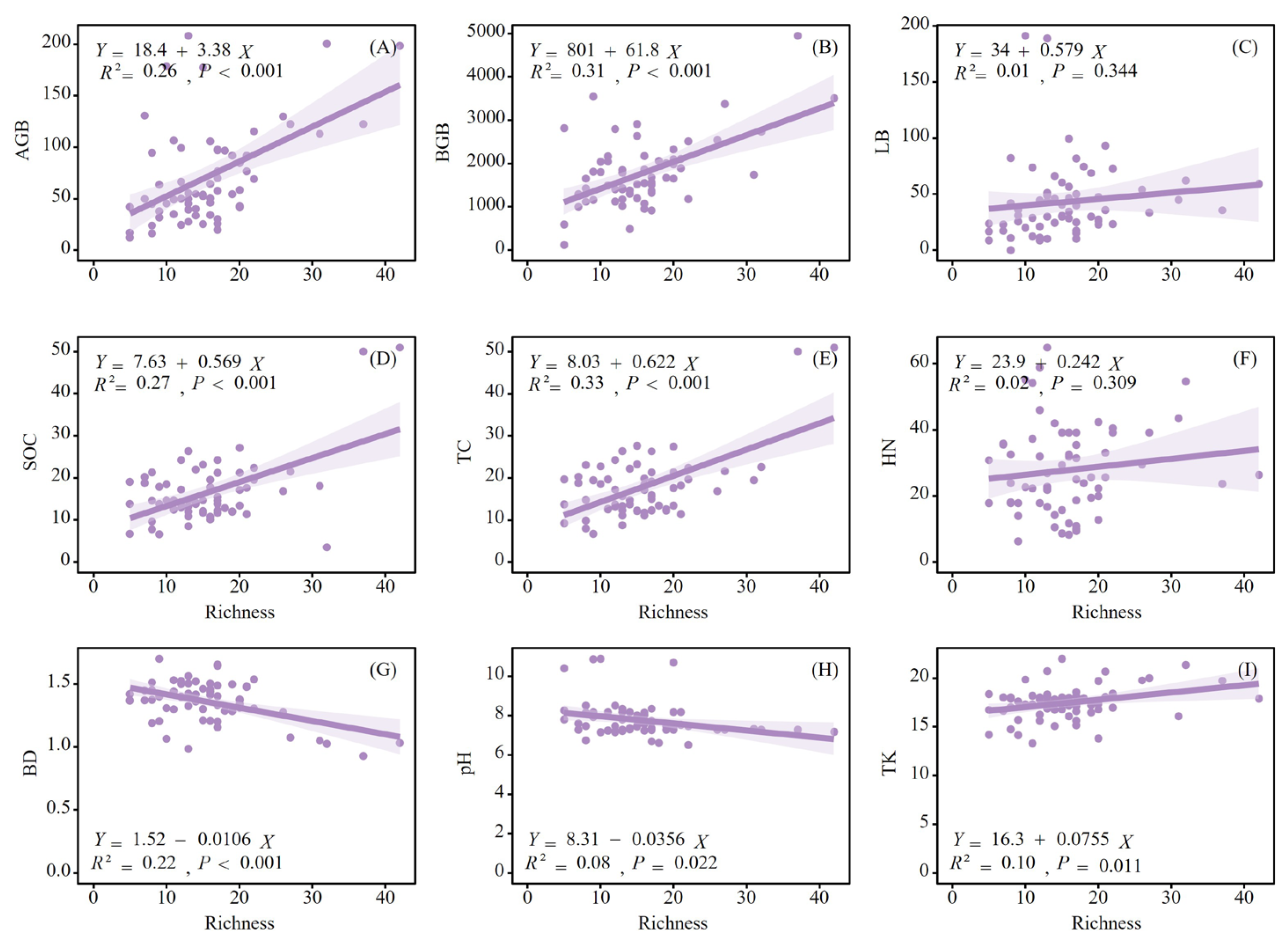

3.4. Plant Biomass, Soil Nutrients, and Plant Diversity Relationships

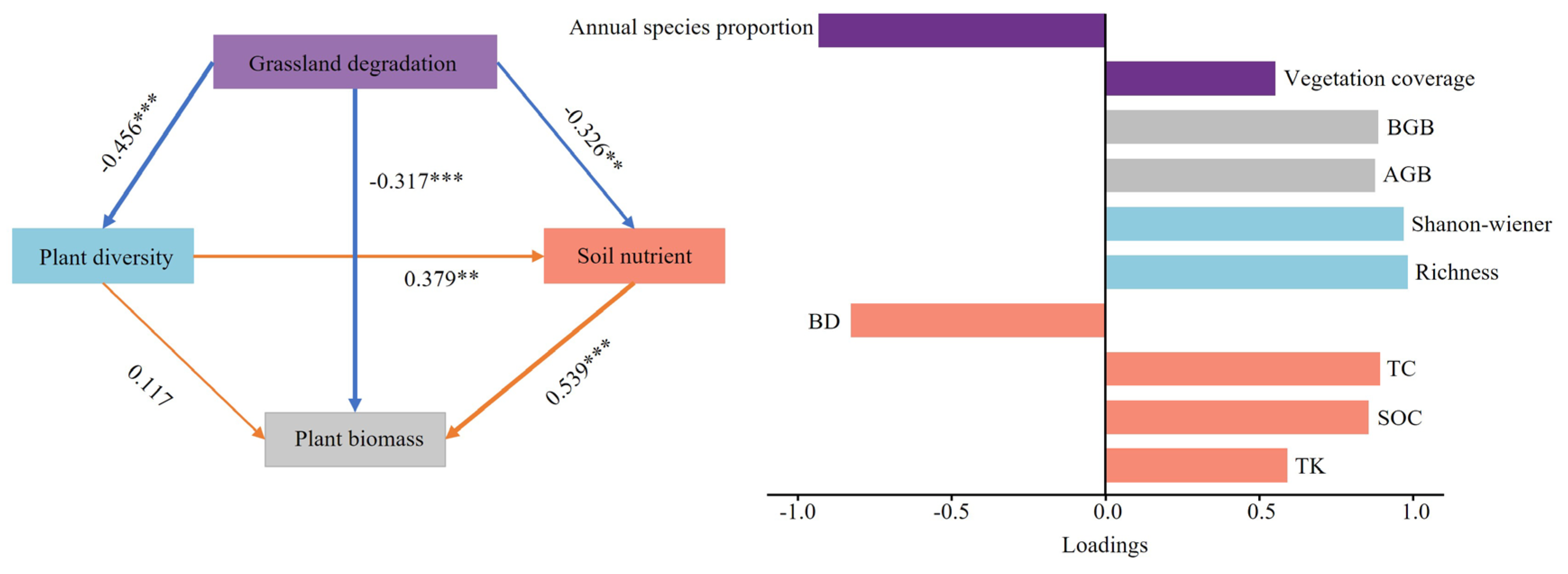

3.5. Plant Diversity and Soil Nutrient Effects on Plant Biomass

4. Discussion

4.1. Grassland Degradation Effects on Plant Composition and Diversity

4.2. Grassland Degradation Effects on Soil Nutrient Factors

4.3. Grassland Degradation Effects on Soil Nutrient, Plant Diversity, and Plant Biomass Relationships

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusion

CRediT statements

Funding

References

- Al-Mufti, M.M.; Sydes, C.L.; Furness, S.B.; Grime, J.P.; Band, S.R. A Quantitative Analysis of Shoot Phenology and Dominance in Herbaceous Vegetation. J. Ecol. 1977, 65, 759–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, J.; Peters, M.K.; Becker, J.N.; Behler, C.; Classen, A.; Ensslin, A.; Ferger, S.W.; Gebert, F.; Gerschlauer, F.; Helbig-Bonitz, M.; et al. Species richness is more important for ecosystem functioning than species turnover along an elevational gradient. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 1582–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Liu, K.; Ahmed, W.; Jing, H.; Qaswar, M.; Anthonio, C.K.; Maitlo, A.A.; Lu, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H. Nitrogen Mineralization, Soil Microbial Biomass and Extracellular Enzyme Activities Regulated by Long-Term N Fertilizer Inputs: A Comparison Study from Upland and Paddy Soils in a Red Soil Region of China. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammer, C. Diversity and forest productivity in a changing climate. New Phytol. 2018, 221, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneja, M.K.; Sharma, S.; Fleischmann, F.; Stich, S.; Heller, W.; Bahnweg, G.; Munch, J.C.; Schloter, M. Microbial Colonization of Beech and Spruce Litter—Influence of Decomposition Site and Plant Litter Species on the Diversity of Microbial Community. Microb. Ecol. 2006, 52, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffret AG, Kimberley A, Plue J, Waldén E (2018) Super-regional land-use change and effects on the grassland specialist flora. Nature Communications 9: 3464.

- Axmanová, I.; Chytrý, M.; Danihelka, J.; Lustyk, P.; Kočí, M.; Kubešová, S.; Horsák, M.; Cherosov, M.M.; Gogoleva, P.A. Plant species richness–productivity relationships in a low-productive boreal region. Plant Ecol. 2012, 214, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Han, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, L. Ecosystem stability and compensatory effects in the Inner Mongolia grassland. Nature 2004, 431, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, J.; Clark, C.M.; Naeem, S.; Pan, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Han, X. Tradeoffs and thresholds in the effects of nitrogen addition on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: evidence from inner Mongolia Grasslands. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2010, 16, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, J.; Pan, Q.; Huang, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, F.; Buyantuyev, A.; Han, X. Positive linear relationship between productivity and diversity: evidence from the Eurasian Steppe. J. Appl. Ecol. 2007, 44, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, J.; Xing, Q.; Pan, Q.; Huang, J.; Yang, D.; Han, X. Primary Production And Rain Use Efficiency Across A Precipitation Gradient On The Mongolia Plateau. Ecology 2008, 89, 2140–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S. , 2005. Soil Agrochemical Analysis, Third ed. China Agriculture Press.

- Bardgett, R.D. , Wardle, D.A., 2010. Aboveground-Belowground Linkages: Biotic Interactions, Ecosystem Processes, and Global Change. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Barrett, C.B.; Zhou, M.; Reich, P.B.; Crowther, T.W.; Liang, J. Forest value: More than commercial—Response. Science 2016, 354, 1541–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, A.J.; Chapin, F.S., III; Mooney, H.A. Resource Limitation in Plants-An Economic Analogy. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1985, 16, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, E.M.; Chase, J.M. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning at local and regional spatial scales. Ecol. Lett. 2002, 5, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyero, L.; Pearson, R.G.; Bastian, M. How biological diversity influences ecosystem function: a test with a tropical stream detritivore guild. Ecol. Res. 2006, 22, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalcraft, D.R.; Williams, J.W.; Smith, M.D.; Willig, M.R. Scale Dependence In The Species-Richness–Productivity Relationship: The Role Of Species Turnover. Ecology 2004, 85, 2701–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, J.M.; Leibold, M.A. Spatial scale dictates the productivity–biodiversity relationship. Nature 2002, 416, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S.; Autumn, K.; Pugnaire, F. Evolution of Suites of Traits in Response to Environmental Stress. Am. Nat. 1993, 142, S78–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, L.; Jing, X.; Wang, J.; Shi, Y.; Chu, H.; He, J. Above- and belowground biodiversity jointly drive ecosystem stability in natural alpine grasslands on the Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 1418–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Yu, T.; Xin, X.; Bai, K.; Zhu, X.; Yan, R. Impacts of Grazing Disturbance on Soil Nitrogen Component Contents and Storages in a Leymus chinensis Meadow Steppe. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Baoyin, T., Xia, F., 2022. Grassland management strategies influence soil C, N, and P sequestration through shifting plant community composition in a semi-arid grasslands of northern China. Ecol. Ind. 134, 108470. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; An, S.; Chen, J.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S. Spatial relationships among species, above-ground biomass, N, and P in degraded grasslands in Ordos Plateau, northwestern China. J. Arid. Environ. 2006, 68, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.T. , 1959. The Vegetation of Wisconsin: An Ordination of Plant Communities. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Dai, L.; Fu, R.; Guo, X.; Du, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Cao, G. Long-term grazing exclusion greatly improve carbon and nitrogen store in an alpine meadow on the northern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. CATENA 2020, 197, 104955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Janssens, I.A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 2006, 440, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Deyn, G.B.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Bardgett, R.D. Plant functional traits and soil carbon sequestration in contrasting biomes. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Deyn, G.B.; Shiel, R.S.; Ostle, N.J.; McNamara, N.P.; Oakley, S.; Young, I.; Freeman, C.; Fenner, N.; Quirk, H.; Bardgett, R.D. Additional carbon sequestration benefits of grassland diversity restoration. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 48, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, F.A.; Cheng, W.; Johnson, D.W. Plant biomass influences rhizosphere priming effects on soil organic matter decomposition in two differently managed soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 2519–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wu, G.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, L. Response of soil properties to yak grazing intensity in a Kobresia parva-meadow on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2012, 12, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanzadeh, R.; Omidipour, R.; Faramarzi, M. Variation of plant diversity components in different scales in relation to grazing and climatic conditions. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2015, 8, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, P.A.; Prober, S.M.; Harpole, W.S.; Knops, J.M.H.; Bakker, J.D.; Borer, E.T.; Lind, E.M.; MacDougall, A.S.; Seabloom, E.W.; Wragg, P.D.; et al. Grassland productivity limited by multiple nutrients. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 15080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayiah, M.; Dong, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, S.; Shen, H.; Xiao, J.; Yang, Y.; Wessell, K. The relationships between plant diversity, plant cover, plant biomass and soil fertility vary with grassland type on Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 286, 106659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, D.A.; Tilman, D. Plant functional composition influences rates of soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation. J. Ecol. 2008, 96, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.B.; Tanaka, D.L.; Hofmann, L.; Follett, R.F. Soil Carbon and Nitrogen of Northern Great Plains Grasslands as Influenced by Long-Term Grazing. J. Range Manag. 1995, 48, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funakawa, S. , Fujii, K., Kadono, A., Watanabe, T., Kosaki, T., 2014. Could Soil Acidity Enhance Sequestration of Organic Carbon in Soils?, in: Hartemink, A.E., McSweeney, K. (Eds.), Soil Carbon. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 209–216. [CrossRef]

- Gan, S. , Xiao, Y., Xu, J., Wang, Y., Yu, F., Xie, G., 2019. Comprehensive cost-benefit evaluation of the Hulunbuir grassland meadow ecological function area. Acta Ecologica Sinica 39: 5874–5884.

- Gang, C.; Zhou, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Qi, J.; Odeh, I. Quantitative assessment of the contributions of climate change and human activities on global grassland degradation. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 4273–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Carmel, Y. Can the intermediate disturbance hypothesis explain grazing–diversity relations at a global scale? Oikos 2019, 129, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China. 2003. GB/19377-2003 Parameters for degradation,sandification and salification of rangelands.

- Gillman, L.N.; Wright, S.D. The Influence Of Productivity On The Species Richness Of Plants: A Critical Assessment. Ecology 2006, 87, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, L.; Grace, J.B.; Taylor, K.L. The Relationship between Species Richness and Community Biomass: The Importance of Environmental Variables. Oikos 1994, 70, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J.B.; Anderson, T.M.; Seabloom, E.W.; Borer, E.T.; Adler, P.B.; Harpole, W.S.; Hautier, Y.; Hillebrand, H.; Lind, E.M.; Pärtel, M.; et al. Integrative modelling reveals mechanisms linking productivity and plant species richness. Nature 2016, 529, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grime, J.P. , 1973. Control of species density in herbaceous vegetation. Journal of Environmental Management.

- Gross, K.L.; Willig, M.R.; Gough, L.; Inouye, R.; Cox, S.B. Patterns of species density and productivity at different spatial scales in herbaceous plant communities. Oikos 2000, 89, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q. , Berry, W.L., 1998. Species Richness and Biomass: Dissection of the Hump-Shaped Relationships. Ecology 79, 2555–2559. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Du, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, S.; Li, Q. Effect of grassland degradation on soil quality and soil biotic community in a semi-arid temperate steppe. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. Rangeland degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau: A review of the evidence of its magnitude and causes. 74, 12. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Davies, K.F.; Safford, H.D.; Viers, J.H. Beta diversity and the scale-dependence of the productivity-diversity relationship: a test in the Californian serpentine flora. J. Ecol. 2005, 94, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhou, G.; Yuan, T.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Shao, J.; Zhou, X. Grazing intensity significantly changes the C : N : P stoichiometry in grassland ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2019, 29, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hector, A.; Bagchi, R. Biodiversity and ecosystem multifunctionality. Nature 2007, 448, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinsinger, P.; Betencourt, E.; Bernard, L.; Brauman, A.; Plassard, C.; Shen, J.; Tang, X.; Zhang, F. P for Two, Sharing a Scarce Resource: Soil Phosphorus Acquisition in the Rhizosphere of Intercropped Species. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.U.; Vitousek, P.M. The Effects of Plant Composition and Diversity on Ecosystem Processes. Science 1997, 277, 1302–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Fanin, N.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Du, G.; Hu, F.; Jiang, L.; Hu, S.; Liu, M. Nutrient-induced acidification modulates soil biodiversity-function relationships. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Li, S.; Guo, Q.; Niu, S.; He, N.; Li, L.; Yu, G. A synthesis of the effect of grazing exclusion on carbon dynamics in grasslands in China. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, F.I.; Polley, H.W.; Wilsey, B.J. Biodiversity, productivity and the temporal stability of productivity: patterns and processes. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.L.; Zhang, W.G.; Wang, G. Effects of different components of diversity on productivity in artificial plant communities. Ecol. Res. 2007, 22, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Kumar, S. A global meta-analysis of livestock grazing impacts on soil properties. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0236638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Eisenhauer, N.; Sierra, C.A.; Bessler, H.; Engels, C.; Griffiths, R.I.; Mellado-Vázquez, P.G.; Malik, A.A.; Roy, J.; Scheu, S.; et al. Plant diversity increases soil microbial activity and soil carbon storage. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, D.C.; Moore, M.M. Climate-induced temporal variation in the productivity–diversity relationship. Oikos 2009, 118, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Zhou, H.; Xue, Y.; Xu, J.; Xue, P.; Yan, H. Effects of Different Grazing Disturbances on the Plant Diversity and Ecological Functions of Alpine Grassland Ecosystem on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 765070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Jia, X.; Dong, G. Influence of desertification on vegetation pattern variations in the cold semi-arid grasslands of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, North-west China. J. Arid. Environ. 2006, 64, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. , Jing, X., Ren, H., Huang, J., He, J., & Fang, J. 2023. Grassland Biodiversity and Stability and Implications for Grassland Conservation and Restoration. 37(04). [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, L.; Ji, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, F.Y. Divergent effects of grazing versus mowing on plant nutrients in typical steppe grasslands of Inner Mongolia. J. Plant Ecol. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tan, N.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, S.; Chu, G.; Liu, J. Plant diversity and species turnover co-regulate soil nitrogen and phosphorus availability in Dinghushan forests, southern China. Plant Soil 2021, 464, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, W.; Feng, B.; Lv, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Dong, Q. Plant biomass partitioning in alpine meadows under different herbivores as influenced by soil bulk density and available nutrients. CATENA 2024, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreau, M.; Naeem, S.; Inchausti, P.; Bengtsson, J.; Grime, J. P.; Hector, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Huston, M.A.; Raffaelli, D.; Schmid, B.; Tilman, D.; et al. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning: Current Knowledge and Future Challenges. Science 2001, 294, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Li, X.; Gong, J.; Wang, H.; Dang, D.; Dou, H.; Li, S.; Liu, S. Comprehensive Grassland Degradation Monitoring by Remote Sensing in Xilinhot, Inner Mongolia, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlo, A.A.; Zhang, S.; Ahmed, W.; Jangid, K.; Ali, S.; Yang, H.; Bhatti, S.M.; Duan, Y.; Xu, M. Potential Nitrogen Mineralization and Its Availability in Response to Long-Term Fertilization in a Chinese Fluvo-Aquic Soil. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, S.J. Compensatory Plant Growth as a Response to Herbivory. Oikos 1983, 40, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. 2021. National Eco-environmental Standard of the People’s Republic of China HJ 1174-2021.

- Mittelbach, G.G. , Steiner, C.F., Scheiner, S.M., Gross, K.L., Reynolds, H.L., Waide, R.B., Willig, M.R., Dodson, S.I., Gough, L., 2001. What Is the Observed Relationship Between Species Richness and Productivity? Ecology 82, 2381–2396. [CrossRef]

- Mosier, S.; Apfelbaum, S.; Byck, P.; Calderon, F.; Teague, R.; Thompson, R.; Cotrufo, M.F. Adaptive multi-paddock grazing enhances soil carbon and nitrogen stocks and stabilization through mineral association in southeastern U.S. grazing lands. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 288, 112409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, S. , 2002. Ecosystem Consequences of Biodiversity Loss: The Evolution of a Paradigm. Ecology 83, 1537–1552. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.; Thompson, L.J.; Lawler, S.P.; Lawton, J.H.; Woodfin, R.M. Declining biodiversity can alter the performance of ecosystems. Nature 1994, 368, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Department of Forest Resource Management, 2022. Technical Regulations for National Forest, Grassland, and Wetland Survey and Monitoring in 2022.

- Ni, J.; Wang, G.; Bai, Y.; Li, X. Scale-dependent relationships between plant diversity and above-ground biomass in temperate grasslands, south-eastern Mongolia. J. Arid. Environ. 2007, 68, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Tang, H.; Fang, F.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z. Is elemental stoichiometry (C, N, P) of soil and soil microbial biomass influenced by management modes and soil depth in agro-pastoral transitional zone of northern China? J. Soils Sediments 2022, 23, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Xue, X.; You, Q.; Huang, C.; Dong, S.; Liao, J.; Duan, H.; Tsunekawa, A.; Wang, T. Changes of soil properties regulate the soil organic carbon loss with grassland degradation on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potthoff, M.; Jackson, L.E.; Steenwerth, K.L.; Ramirez, I.; Stromberg, M.R.; Rolston, D.E. Soil Biological and Chemical Properties in Restored Perennial Grassland in California. Restor. Ecol. 2005, 13, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, S.; Mazalová, M.; Šipoš, J.; Kuras, T. Impacts of Mowing, Grazing and Edge Effect on Orthoptera of Submontane Grasslands: Perspectives for Biodiversity Protection. Pol. J. Ecol. 2014, 62, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiesi, F.; Salek-Gilani, S. Development of a soil quality index for characterizing effects of land-use changes on degradation and ecological restoration of rangeland soils in a semi-arid ecosystem. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, M.K.; Marsden, K.A.; Powell, S.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L.; Evershed, R.P. Combining field and laboratory approaches to quantify N assimilation in a soil microbe-plant-animal grazing land system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Li, Z.; Shen, W.; Yu, Z.; Peng, S.; Liao, C.; Ding, M.; Wu, J. Changes in biodiversity and ecosystem function during the restoration of a tropical forest in south China. Sci. China Life Sci. 2007, 50, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, G.P.; Hutson, M.A.; Evans, F.C.; Tiedje, J.M. Spatial Variability in a Successional Plant Community: Patterns of Nitrogen Availability. Ecology 1988, 69, 1517–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardans, J.; Bartrons, M.; Margalef, O.; Gargallo-Garriga, A.; Janssens, I.A.; Ciais, P.; Obersteiner, M.; Sigurdsson, B.D.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Peñuelas, J. Plant invasion is associated with higher plant–soil nutrient concentrations in nutrient-poor environments. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 23, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hockett, C.F.; Shannon, C.L.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Language 1953, 29, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Liu, C.; Chang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, D. Sheep grazing and local community diversity interact to control litter decomposition of dominant species in grassland ecosystem. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 115, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, M.; Kölbl, A.; Totsche, K.U.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Grazing effects on soil chemical and physical properties in a semiarid steppe of Inner Mongolia (P.R. China). Geoderma 2007, 143, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ma, B.; Lu, X. Grazing enhances soil nutrient effects: Trade-offs between aboveground and belowground biomass in alpine grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau. Land Degrad. Dev. 2017, 29, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talore, D.G.; Tesfamariam, E.H.; Hassen, A.; Du Toit, J.; Klampp, K.; Jean-Francois, S. Long-term impacts of grazing intensity on soil carbon sequestration and selected soil properties in the arid Eastern Cape, South Africa. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 96, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D. The Ecological Consequences of Changes in Biodiversity: A Search for General Principles. Ecology 1999, 80, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D. The Resource-Ratio Hypothesis of Plant Succession. Am. Nat. 1985, 125, 827–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Lehman, C.L.; Thomson, K.T. Plant diversity and ecosystem productivity: Theoretical considerations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997, 94, 1857–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D.; Wedin, D.; Knops, J. Productivity and sustainability influenced by biodiversity in grassland ecosystems. Nature 1996, 379, 718–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waide, R.B.; Willig, M.R.; Steiner, C.F.; Mittelbach, G.; Gough, L.; Dodson, S.I.; Juday, G.P.; Parmenter, R. The Relationship Between Productivity and Species Richness. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1999, 30, 257–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huawei, W. Grassland degradation monitoring and spatio-temporal variation analysis of the Hulun Buir Ecological Function Region. 资源科学 2016, 38, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, Z.G.; Xu, X.H.; Liang, T.G.; Ren, J.Z. Response of vegetation and soils to desertification of alpine meadow in the upper basin of the Yellow River, China. New Zealand J. Agric. Res. 2007, 50, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Hong, Y., Bao, G., Hu, L., Bao, H., Ga, B., 2014. Comparative study on plant community characteristics in Hulunbuir grassland. Journal of Inner Mongonlia Normal University (Natural Science Edition).

- Wang, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, T. [Changes of biomass allocation of Artemisia frigida population in grazing-induced retrogressive communities]. . 2005, 16, 2316–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Sardans, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, C.; Lü, X.; Dijkstra, F.A.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Nitrogen enrichment buffers phosphorus limitation by mobilizing mineral-bound soil phosphorus in grasslands. Ecology 2021, 103, e3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sardans, J.; Zeng, C.; Zhong, C.; Li, Y.; Peñuelas, J. Responses of soil nutrient concentrations and stoichiometry to different human land uses in a subtropical tidal wetland. 232-234. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, S.; Yang, B.; Li, Y.; Su, X. The effects of grassland degradation on plant diversity, primary productivity, and soil fertility in the alpine region of Asia’s headwaters. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 6903–6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yan, Y.; Cao, Y. Impact of historic grazing on steppe soils on the northern Tibetan Plateau. Plant Soil 2011, 354, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wesche, K. Vegetation and soil responses to livestock grazing in Central Asian grasslands: a review of Chinese literature. Biodivers. Conserv. 2016, 25, 2401–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, T.; Li, R.; Tang, Y.; Du, M. Causes for the unimodal pattern of biomass and productivity in alpine grasslands along a large altitudinal gradient in semi-arid regions. J. Veg. Sci. 2012, 24, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R. , Brady, N., 2017. The Nature and Properties of Soils. 15th edition.

- Wu, G.-L.; Liu, Z.-H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.-M.; Hu, T.-M. Long-term fencing improved soil properties and soil organic carbon storage in an alpine swamp meadow of western China. Plant Soil 2010, 332, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Ren, G.; Dong, Q.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y. Above- and Belowground Response along Degradation Gradient in an Alpine Grassland of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. CLEAN – Soil, Air, Water 2013, 42, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, M.; Fiedler, S.; Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Tietjen, B. Impacts of grazing exclusion on productivity partitioning along regional plant diversity and climatic gradients in Tibetan alpine grasslands. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 231, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Sha, Z.; Yu, M. Remote sensing imagery in vegetation mapping: a review. J. Plant Ecol. 2008, 1, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.P.; Zhang, J.; Pang, X.P.; Wang, Q.; Na Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Guo, Z.G. Responses of plant productivity and soil nutrient concentrations to different alpine grassland degradation levels. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Tsang, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Fu, X.; Sun, Y. Plant litter composition selects different soil microbial structures and in turn drives different litter decomposition pattern and soil carbon sequestration capability. Geoderma 2018, 319, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.Y.; Jiao, F.; Li, Y.H.; Kallenbach, R.L. Anthropogenic disturbances are key to maintaining the biodiversity of grasslands. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shen, J.; Li, L.; Liu, X. An overview of rhizosphere processes related with plant nutrition in major cropping systems in China. Plant Soil 2004, 260, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Niu, J.; Buyantuyev, A.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Y.; Dong, J. Productivity–species richness relationship changes from unimodal to positive linear with increasing spatial scale in the Inner Mongolia steppe. Ecol. Res. 2011, 26, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, Z.; Han, G.; Schellenberg, M.P.; Wu, Q.; Gu, C. Grazing induced changes in plant diversity is a critical factor controlling grassland productivity in the Desert Steppe, Northern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 265, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xin, X.; Wang, M.; Pan, F.; Yan, R.; Li, L. Effects of stocking rate on the interannual patterns of ecosystem biomass and soil nitrogen mineralization in a meadow steppe of northeast China. Plant Soil 2021, 473, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou M, Yang Q, Zhang H, Yao X, Zeng W, Wang W (2020) Plant community temporal stability in response to nitrogen addition among different degraded grasslands. Science Of the Total Environment 729: 138886.

- Zuo, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, X.; Guo, Y.; Yun, J.; Wang, S.; Miyasaka, T. Vegetation pattern variation, soil degradation and their relationship along a grassland desertification gradient in Horqin Sandy Land, northern China. Environ. Geol. 2008, 58, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Degradation grades | GDI value (%) |

|---|---|

| Non-degraded (ND) | GDI ≥ 90 |

| Lightly Degraded (LD) | 80 ≤ GDI < 90 |

| Moderately Degraded (MD) | 70 ≤GDI < 80 |

| Severely Degraded (SD) | 50 ≤ GDI < 70 |

| Extremely Degraded (ED) | GDI < 50 |

| r2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| BD | 0.291 | 0.001 |

| TK | 0.570 | 0.001 |

| SOC | 0.163 | 0.010 |

| TC | 0.123 | 0.029 |

| HN | 0.124 | 0.031 |

| pH | 0.106 | 0.042 |

123. Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).