Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Croitoru, L.; Chang, J.C.; Akpokodje, J. The Health Cost of Ambient Air Pollution in Lagos. J. Environ. Prot. 2020, 11, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, A.; Harmon, A.C.; Dugas, T.R. Particulate matter air pollutants and cardiovascular disease: Strategies for intervention. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 223, 107890–107890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.J.; Anderson, H.R.; Ostro, B.; Pandey, K.D.; Krzyzanowski, M.; Künzli, N.; Gutschmidt, K.; Pope, A.; Romieu, I.; Samet, J.M.; et al. The Global Burden of Disease Due to Outdoor Air Pollution. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2005, 68, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Profaci, C.P.; Munji, R.N.; Pulido, R.S.; Daneman, R. The blood–brain barrier in health and disease: Important unanswered questions. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. The blood–brain barrier: Structure, regulation and drug delivery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chai, G.; Song, X.; Hui, X.; Li, Z.; Feng, X.; Yang, K. Long-term exposure to particulate matter on cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1134341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, B.N.; Prados, A.I.; Lamsal, L.N.; Liu, Y.; Streets, D.G.; Gupta, P.; Hilsenrath, E.; Kahn, R.A.; Nielsen, J.E.; Beyersdorf, A.J.; et al. Satellite data of atmospheric pollution for U.S. air quality applications: Examples of applications, summary of data end-user resources, answers to FAQs, and common mistakes to avoid. Atmospheric Environ. 2014, 94, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, M.; Holloway, T.; Choi, S.; O’neill, S.M.; Al-Hamdan, M.Z.; Van Donkelaar, A.; Martin, R.V.; Jin, X.; Fiore, A.M.; Henze, D.K.; et al. Methods, availability, and applications of PM2.5 exposure estimates derived from ground measurements, satellite, and atmospheric models. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2019, 69, 1391–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulude, F.O.; Damodharan, U.; Acha, S.; Adamu, A.; Arifalo, K.M. Preliminary Assessment of Air Pollution Quality Levels of Lagos, Nigeria. International Electronic Conference on Geosciences. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 20.

- Obanya, H.E.; Amaeze, N.H.; Togunde, O.; Otitoloju, A.A. Air Pollution Monitoring Around Residential and Transportation Sector Locations in Lagos Mainland. J. Heal. Pollut. 2018, 8, 180903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alani, R.A.; Ayejuyo, O.O.; Akinrinade, O.E.; Badmus, G.O.; Festus, C.J.; Ogunnaike, B.A.; Alo, B.I. The level PM2.5 and the elemental compositions of some potential receptor locations in Lagos, Nigeria. Air Qual. Atmosphere Heal. 2019, 12, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, H.A. and Muhammed, M. I. Atmospheric Physics; Air Pollution Monitoring and Analysis Using Purple Air Data. African Scientific Reports. 2022, 1, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Yahaya, T.; Umar, F.M.; Zanna, A.M.; Abdulmalik, A.; Ibrahim, B.A.; Bilyaminu, M.; Joseph, A. Concentrations and health risks of particulate matter (PM2.5) and associated elements in the ambient air of Lagos, Southwestern Nigeria. Bio-Research 2023, 21, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, O.A.M.; Alani, R.; Assah, F.; Lawanson, T.; Tchouaffi, A.K.; Mapa-Tassou, C.; Blanche, N.; Odekunle, D.; Unuigboje, R.; Onifade, V.A.; et al. Assessment of the Temporal and Seasonal Variabilities in Air Pollution and Implications for Physical Activity in Lagos and Yaoundé. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saetae, S.; Abulude, F.O.; Ndamitso, M.M.; Akinnusotu, A.; Oluwagbayide, S.D.; Matsumi, Y.; Kanegae, K.; Kawamoto, K.; Nakayama, T. Multi-Year Continuous Observations of Ambient PM2.5 at Six Sites in Akure, Southwestern Nigeria. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamseddine, A.; Alameddine, I.; Hatzopoulou, M.; El-Fadel, M. Seasonal variation of air quality in hospitals with indoor–outdoor correlations. Build. Environ. 2018, 148, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, C.; Fakinle, B.; Jimoda, L.; Sonibare, J. Investigation on the ambient air quality in a hospital environment. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Occupational and Environmental Health Team. WHO Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide: global update 2005: summary of risk assessment. 2006. World Health Organization. https:// apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/69477.

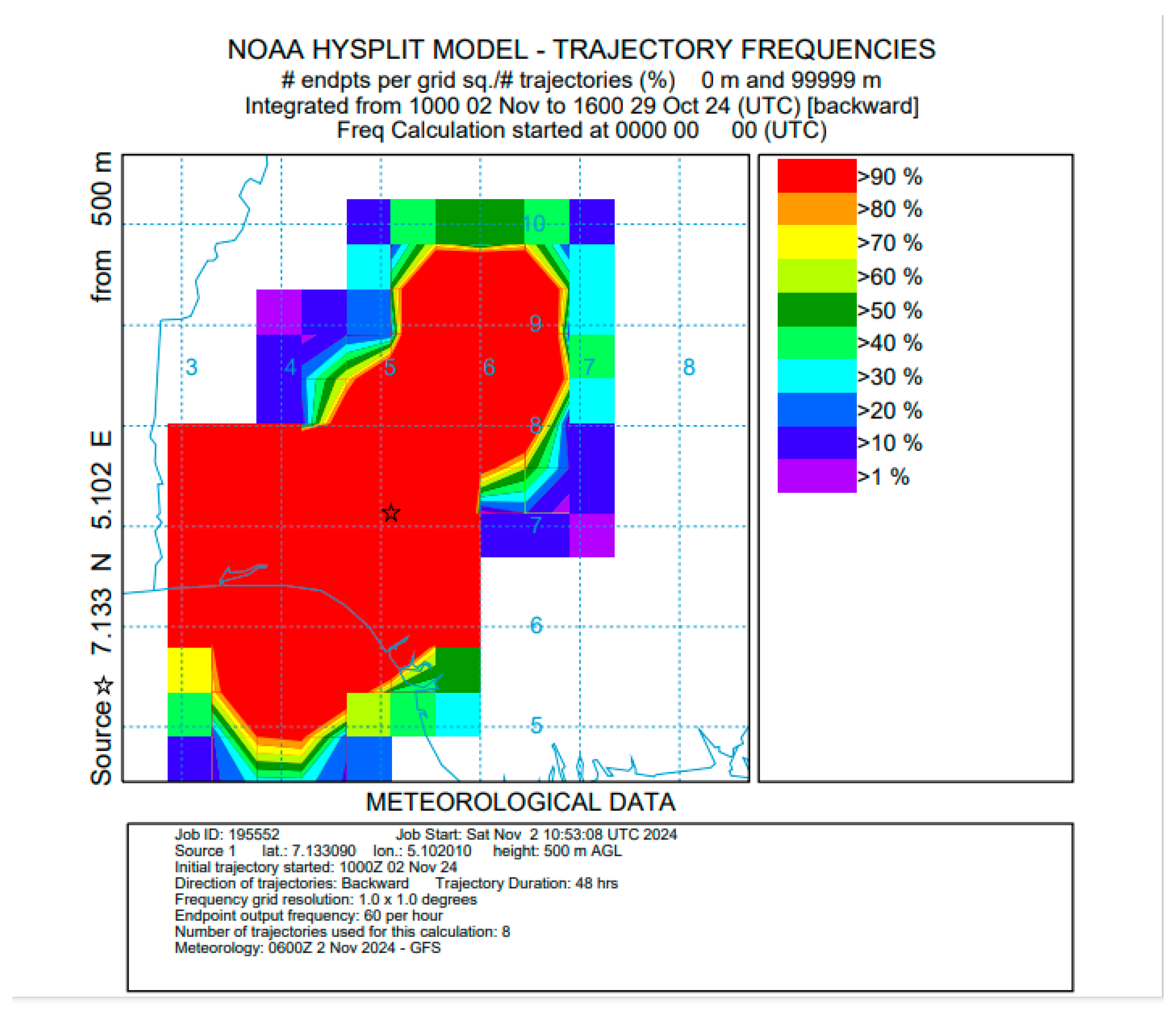

- Draxler RR, Hess GD. Description of the HYSPLIT 4 modeling system (NOAA technical memorandum ERL ARL-224). 2004, NOAA Air Resources Laboratory, Silver Spring.

- Arcadi, A.; Morlacci, V.; Palombi, L. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Containing Heterocyclic Scaffolds through Sequential Reactions of Aminoalkynes with Carbonyls. Molecules 2023, 28, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odu-Onikosi, A.; Herckes, P.; Fraser, M.; Hopke, P.; Ondov, J.; Solomon, P.A.; Popoola, O.; Hidy, G.M. Tropical Air Chemistry in Lagos, Nigeria. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Ho, K.; Lee, S.; Law, S. Seasonal and diurnal variations of PM1.0, PM2.5 and PM10 in the roadside environment of hong kong. China Particuology 2006, 4, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oanh, N.K.; Upadhyay, N.; Zhuang, Y.-H.; Hao, Z.-P.; Murthy, D.; Lestari, P.; Villarin, J.; Chengchua, K.; Co, H.; Dung, N.; et al. Particulate air pollution in six Asian cities: Spatial and temporal distributions, and associated sources. Atmospheric Environ. 2006, 40, 3367–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abulude, F.O.; Abulude, I.A. Monitoring Air Quality in Nigeria: The Case of Center for Atmospheric Research-National Space Research and Development Agency (CAR-NASRDA). Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2021, 5, 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridi, S.; Shamsipour, M.; Krzyzanowski, M.; Künzli, N.; Amini, H.; Azimi, F.; Malkawi, M.; Momeniha, F.; Gholampour, A.; Hassanvand, M.S.; et al. Long-term trends and health impact of PM2.5 and O3 in Tehran, Iran, 2006–2015. Environ. Int. 2018, 114, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghvaee, S.; Sowlat, M.H.; Mousavi, A.; Hassanvand, M.S.; Yunesian, M.; Naddafi, K.; Sioutas, C. Source apportionment of ambient PM2.5 in two locations in central Tehran using the Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) model. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 628-629, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.F.; Draxler, R.R.; Rolph, G.D.; Stunder, B.J.B.; Cohen, M.D.; Ngan, F. NOAA’s HYSPLIT Atmospheric Transport and Dispersion Modeling System. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 96, 2059–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolph, G.; Stein, A.; Stunder, B. Real-time Environmental Applications and Display sYstem: READY. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 95, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoade, O.K.; Olise, F.S.; Ogundele, L.T.; Fawole, O.G.; Olaniyi, H.B. Correlation between particulate matter concentrations and meteorological parameters at a site in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Ife J. Sci. 2012, 14, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

| City (Country) | Title of studies | Instrument Used | Key findings | Reference |

| Lagos Mainland, Nigeria | Air Pollution Monitoring Around Residential and Transportation Sector Locations in Lagos Mainland |

Handheld air tester (CW – HAT 200) | PM10 43.34 – 127.21 μg/m3, and PM2.5 20.32 – 69.05 μg/m3 | [10] |

| Lagos, Nigeria | The Health Cost of Ambient Air Pollution in Lagos | air samplers | Ikeja (77 µg/m3 ), Mushin (85 µg/m3 ) and Ikoyi (41 µg/m3 ) | [1] |

| Allen Avenue, Kolington, Isheri, Badagry, Opebi, Eti-Osa, Ajeniya, Awolowo, Orile, and Ajegunle, Lagos, Nigeria | Concentrations and health risks of particulate matter (PM2.5) and associated elements in the ambient air of Lagos, Southwestern Nigeria | Aerosol Mass Monitor | PM2.5 Allen Avenue (16.83 µg/m3), Kolington (15.85 µg/m3), Isheri 27.22 µg/m3), Badagry (5.36 µg/m3), Opebi (17.85 µg/m3), Eti-osa (31.32 µg/m3), Ajeniya (34.63 µg/m3), Awolowo (17.31 µg/m3), Orile (28.48 µg/m3), Ajegunle (29.65 µg/m3) |

[13] |

| Ikeja, Maryland, Ojodu, Eti-Osa, and Opebi, Lagos, Nigeria | Preliminary Assessment of Air Pollution Quality Levels of Lagos, Nigeria |

Satellite Data |

PM2.5 and PM10 over Ikeja was between 20–123 μg/m3 and 30–176 μg/m3 ; Maryland was between 22– 120 μg/m3 and 33–173 μg/m3 ; Ojodu was between 17 μg/m3 –81 μg/m3 and 27–121 μg/m3 ; and Eti-Osa was between 5 μg/m3 –212 μg/m3 and 9 μg/m3 –298 μg/m3 . In Opebi, however, PM2.5 and PM10 were between 26–163 μg/m3 and 40–241 μg/m3, respectively. |

[9] |

| University of Lagos, Akoka and Agege, Lagos | The level PM2.5 and the elemental compositions of some potential receptor locations in Lagos, Nigeria | Aerosol samples were captured on a microglass fiber particle filter and the PM2.5 determined gravimetrically | PM2.5 6 to 14 μg/m3 in Unilag and Agege respectively |

[11] |

| Victoria Island (in Lagos, Nigeria) and Melen Mini-Ferme, (Yaoundé, Cameroon | Assessment of the Temporal and Seasonal Variabilities in Air Pollution and Implications for Physical Activity in Lagos and Yaoundé |

AQMesh | Mean PM2.5 26 µg/m3 (Lagos) and 28 µg/m3 (Yaoundé) | [14] |

| Lagos, Rivers and Abuja namely Lekki, Port Harcourt and Lugbe | Atmospheric Physics; Air Pollution Monitoring and Analysis Using Purple Air Data | PurpleAir sensors. | The results indicate that Port Harcourt has the greatest concentration of particulate matter among the research regions, afterwards Lugbe, which has an average level of Standard Indoor (CF1) PM2.5 & PM10.0 of 12 weeks. concentration and Standard Outdoor or Atmospheric(ATM) PM2.5 concentration to be 87.80 µg/m3 , 101.76 µg/m3 and 63.15 µg/m3 respectively while Abuja has an average PM2.5 CF1, PM10.0 CF1 and PM2.5 ATM values of 70.51 µg/m3 , 86.21 µg/m3 and 52.07 µg/m3 respectively |

[12] |

| Akure, Nigeria | Multi-Year Continuous Observations of Ambient PM2.5 at Six Sites in Akure, Southwestern Nigeria |

P-sensors | Compared to the rainy season, PM2.5 levels were much higher during the dry season (November–March), frequently surpassing dangerous levels (over 350 µg/m3). |

[15] |

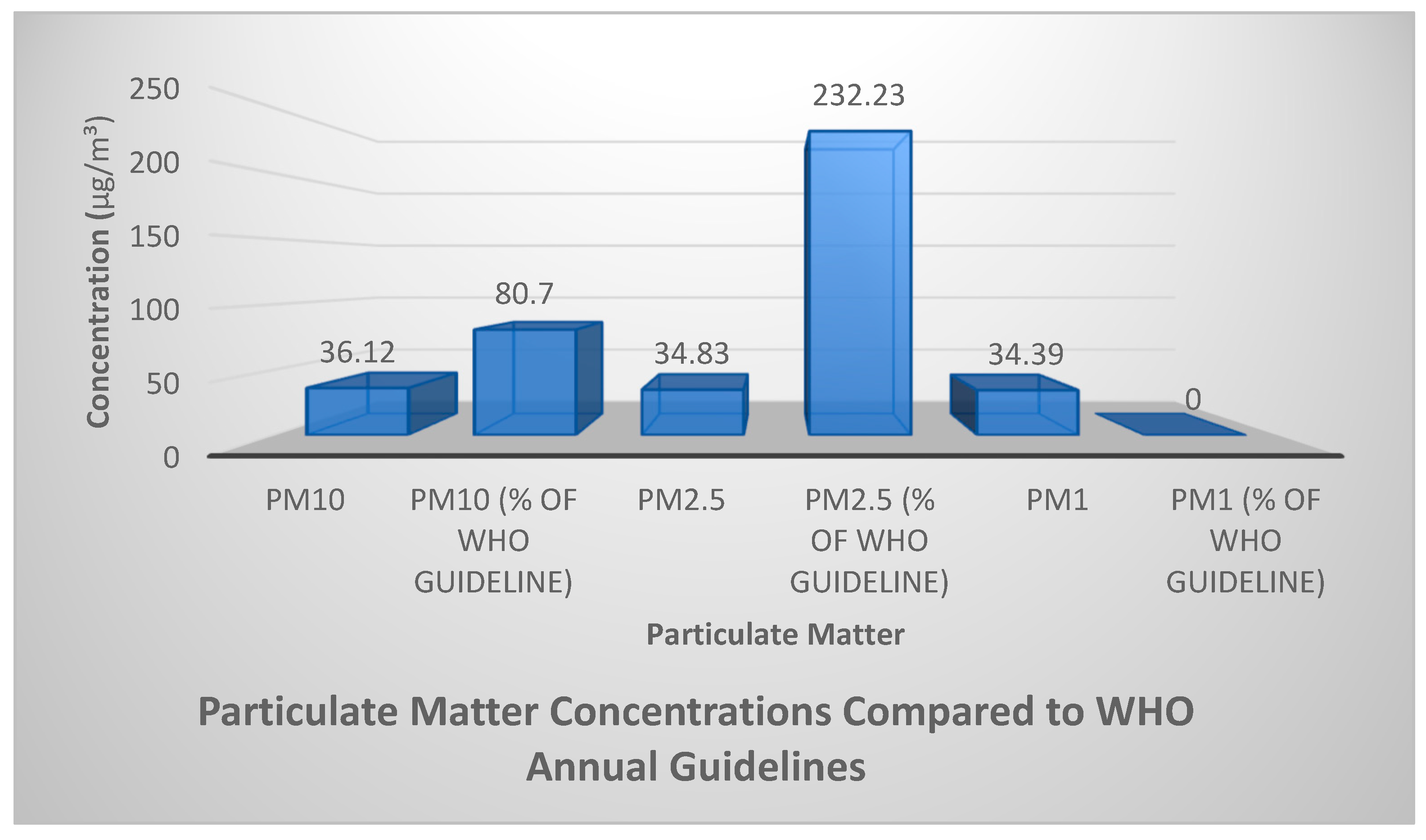

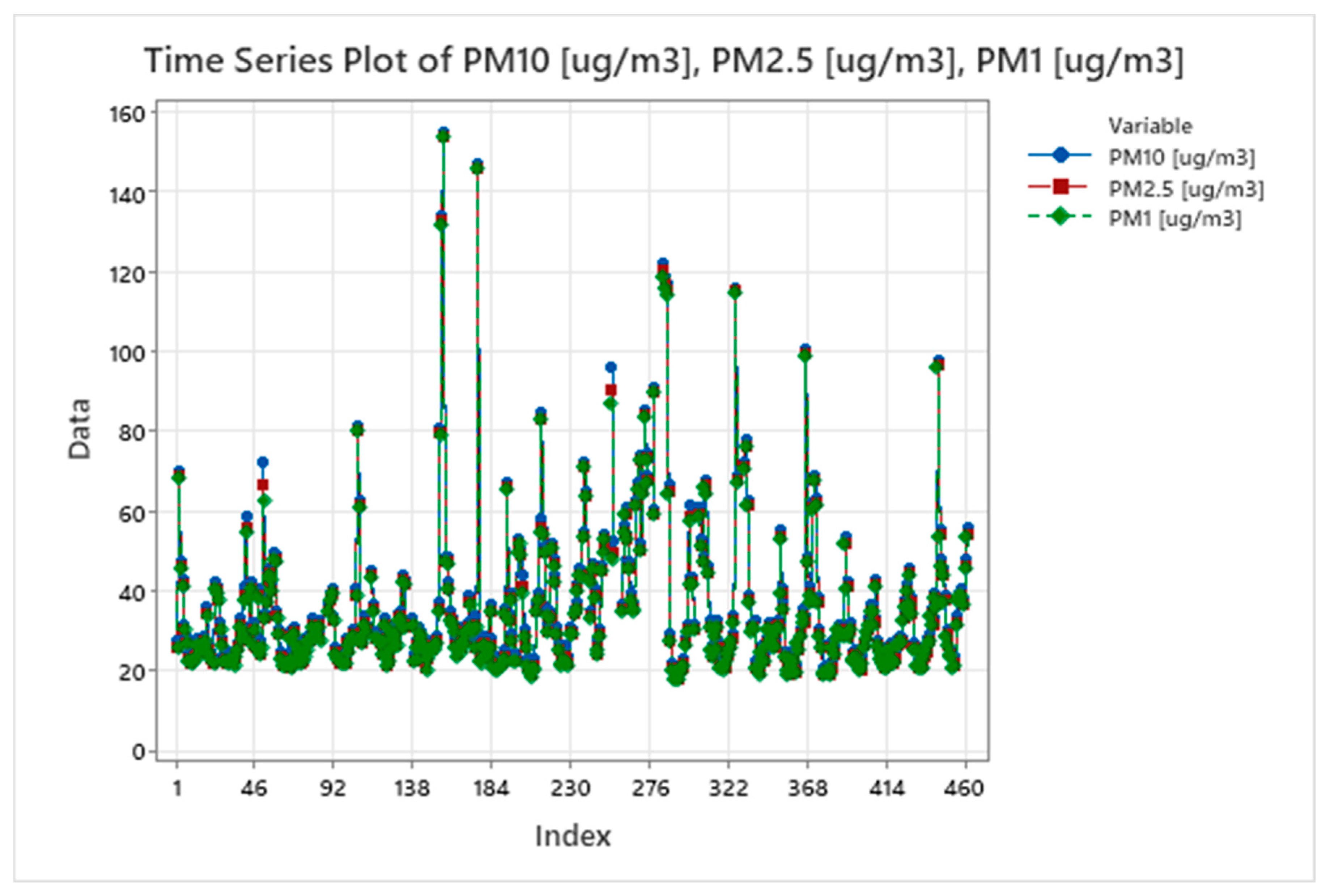

| Variable | Mean | StD | CV (%) | Min | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM10 | 36.32 | 18.57 | 51.13 | 19.45 | 25.26 | 30.06 | 40.38 | 154.84 | 2.92 | 11.24 |

| PM2.5 | 34.83 | 18.58 | 53.35 | 18.01 | 23.51 | 28.63 | 38.74 | 154.02 | 2.92 | 11.32 |

| PM1 | 34.39 | 18.54 | 53.92 | 17.58 | 23.01 | 28.30 | 37.99 | 153.74 | 2.92 | 11.38 |

| Wind Speed | 8.56 | 3.19 | 36.84 | 2.08 | 6.17 | 8.46 | 11.03 | 16.98 | 0.28 | -0.59 |

| Wind Bearing | 224.62 | 36.71 | 16.34 | 10.20 | 206.49 | 217.66 | 137.11 | 358.61 | 0.23 | 4.73 |

| Pressure | 1013.3 | 1.73 | 0.17 | 1008.6 | 1012.3 | 1013.4 | 1014.6 | 1017.5 | -0.22 | -0.29 |

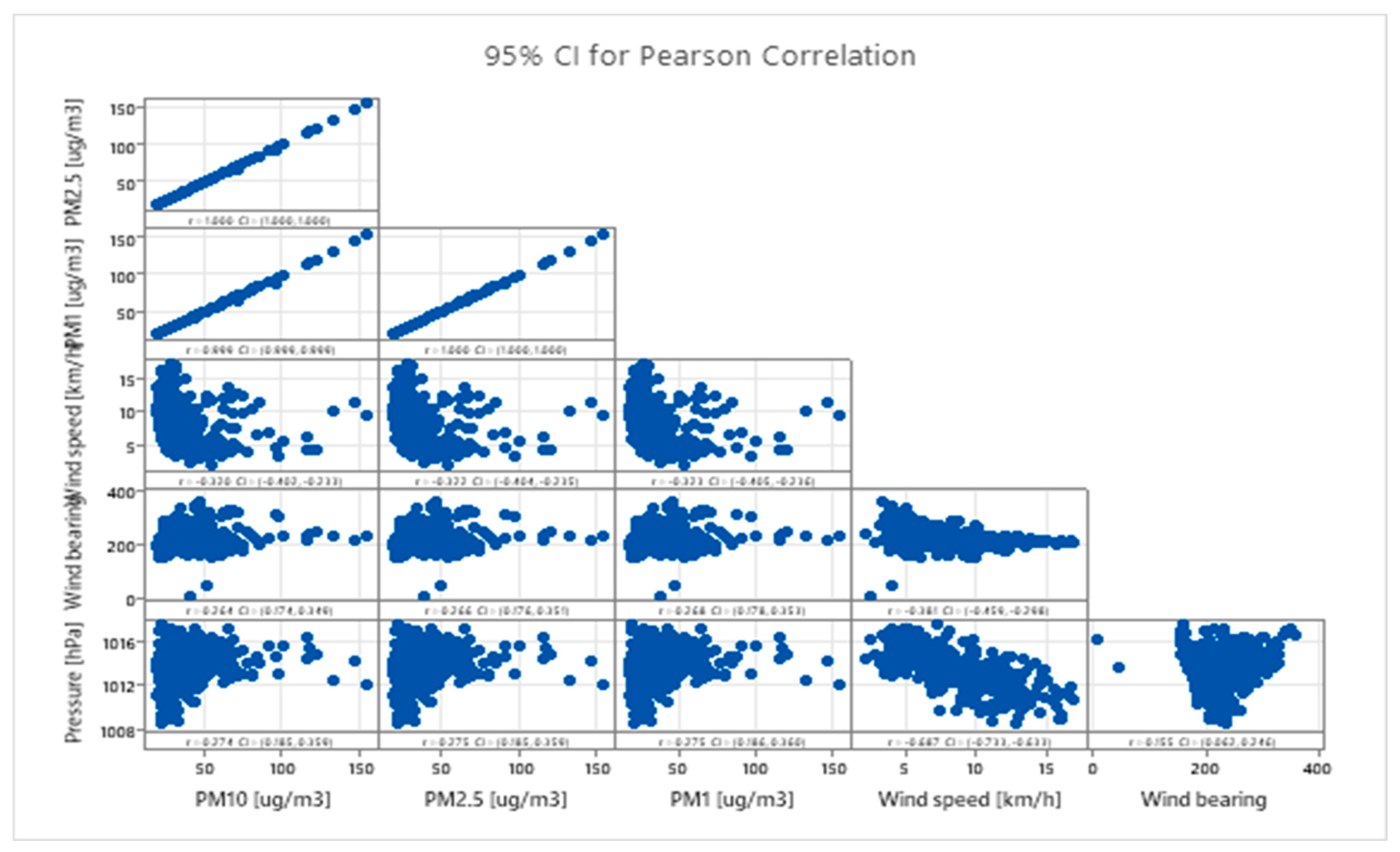

| PM10 | PM2.5 | PM1 | Wind speed | Wind bearing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM10 PM2.5 |

1.000 | ||||

| PM1 | 0.999 | 1.000 | |||

| Wind speed | -0.320 | -0.322 | -0.323 | ||

| Wind bearing | 0.264 | 0.266 | 0.268 | -0.381 | |

| Pressure | 0.274 | 0.275 | 0.275 | -0.687 | 0.155 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).