1. Introduction

Cranio-maxillofacial injury [CMF] is any injury to the craniofacial region, that involves hard tissue and/or soft tissue injury and is often associated with high morbidity. Cranio-maxillofacial injuries are prevalent among trauma patients. These injuries may present independently or in conjunction with other injuries, such as spinal, abdominal, upper extremity, and lower extremity injuries [

1,

2].

Surgical management involves fracture site exposure, reduction, plate fixation, and soft tissue repair. The goal of open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is to provide stability for immediate function. In 1973, Michelet ended the search for simple osteosynthesis that would guarantee fracture healing without compression [

3] which was modified, and put to practical use by Champy [

4]. Miniplates are currently utilized to achieve stability between bony fragments in the maxillofacial region for the fixation of fractures and osteotomies [

5].

Initially, stainless steel (SS) material plates and screws were utilised for fracture fixation which had several disadvantages. Thereafter, titanium (Ti) material plates which have better biocompatibility gained popularity and increased acceptance. In vitro simulation studies, animal studies as well as electrochemical studies have shown that both the implant material have the potential to corrode in body fluids [

6,

7]. Immuno-inflammatory reactions have also been reported following the use of titanium (Ti) and stainless steel (SS) plates and screws in fracture fixation [

8,

9].

Postoperative infections necessitating the need for removal of miniplate hardware have been reported to range from 10-40% with higher incidence among stainless steel plates and screws [

10,

11]. Infections often result from bacterial biofilms on the foreign material and adjacent bone, with bacteria such as

Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus salivarius, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa being implicated [

12]. Titanium and its alloys are favoured for biomedical use due to their mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and corrosion resistance, leading to a decline in implant-related infections [

13]. Nevertheless, additional efforts are still required to further make improvements and provide optimal outcomes.

The use of surface modifications on implant materials has gained attention as a strategy to combat biofilm formation and enhance physical and chemical properties. New antimicrobial agents, free from antibiotics, have been developed and tested [

14,

15]. Selenium-based compounds, recognized for anticancer activity and low toxicity, have been explored as surface coatings on titanium implants, demonstrating strong antimicrobial effects [

16].

However, research on the alterations in the physical and chemical properties of selenium-coated titanium implants, as well as their antimicrobial efficacy, remains limited [

17,

18,

19]. Thus, this study aims to assess the surface properties and antimicrobial efficacy of selenium-coated titanium miniplates and screws.

2. Materials And Methods

This invitro study was undertaken after obtaining ethical clearance (CSP/23/FEB/123/139) from the institutional ethics committee, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research. The study involves three commercially available titanium miniplate systems namely Leforte (CMF Leforte system) (Group A), Synthes (DePuy Synthes Co. Zuchwil, Switzerland) (Group B), and Stryker (Stryker Leibinger Inc) (Group C), for all the experimental procedures. Each system was divided into a control group (uncoated) and test group (coated with selenium All test samples were treated with commercially available selenous acid (Sigma Aldrich EC 231-974- 7). All reagents used in the procedures were analytical grade. Double distilled (DD) water was utilised for the preparation of solutions.

2.1. Preparation Of Selenium Coated Test Samples

Titanium miniplates and screws were polished using 0.3 -µm aluminum before being ultrasonically cleaned with double distilled water. The polished titanium surface was first etched with absolute ethanol (99.9%) for 24 hours at 24°C. The titanium samples were then rinsed with double distilled water and dried in a stream of dry air.

The test group samples were treated with a 4 mmol selenous acid solution for 6 hours at 24°C Visual confirmation of the interaction of selenium with titanium was by the appearance of a bluish hue on the surface on the treated samples (

Figure 1).

The resultant samples were then rinsed with double distilled water and dried in a stream of dry air.

2.2. Characterization of the Samples

Three samples from each group were used for characterization of the selenium on the titanium surface using a Scanning Electron Microscopy (Carl Zeiss Crossbeam 340) under 10, 25 and 50µm magnification. The qualitative analysis of the samples was performed by Fourier Transformer Infra -Red (FTIR) spectroscopy. The FTIR spectra were recorded on spectrometer, using attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode. Measurements were performed in a spectral range of 400 –4,000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

Further, scratch tests were conducted using a diamond indenter with a 0.4 mm radius, applying a load that increased from 0.03 to 30 N at a loading rate of 71.3 N per minute. The scratch tracks length was set at a standard of 2mm (

Figure 2).

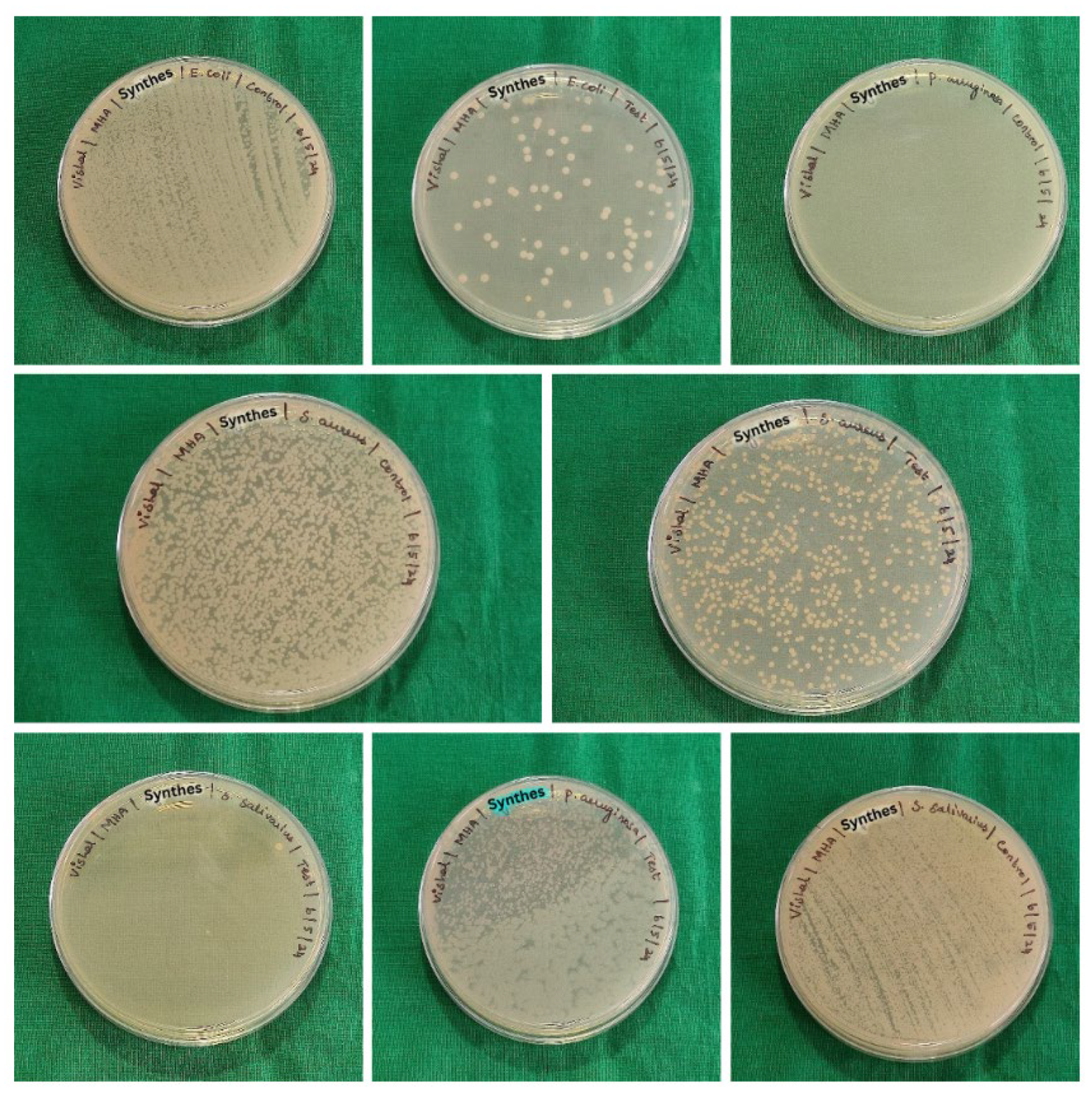

2.3. Antimicrobial Efficacy

The antimicrobial activity of the titanium-selenium (Ti-Se) surface was tested against the gram-negative bacteria

Escherichia coli, gram-positive bacteria

Streptococcus salivarius, gram negative bacteria

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and gram-positive

Staphylococcus aureus. The samples consist of 6 groups (five samples per group) which were immersed in sterile brain heart infusion (BHI) with fresh suspensions of the test organisms. The samples were incubated at 37ºC for 5 hours to encourage the growth of biofilms. Following incubation, the samples were gently agitated, swabs were taken and lawn culture was made on the sterile Blood agar (BA) and Mueller Hinton agar (MHA). The culture plates were incubated at 37 ºC for 48 hours. After incubation, the colonies were counted and recorded as colony forming units (CFU) per ml (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS (version 26). Unpaired t-tests were used to compare contact angles between control and test samples across all three groups. Pairwise comparisons were employed to assess differences in penetration depth. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to analyse the comparisons of colony-forming units (CFU) among all groups.

3. Results

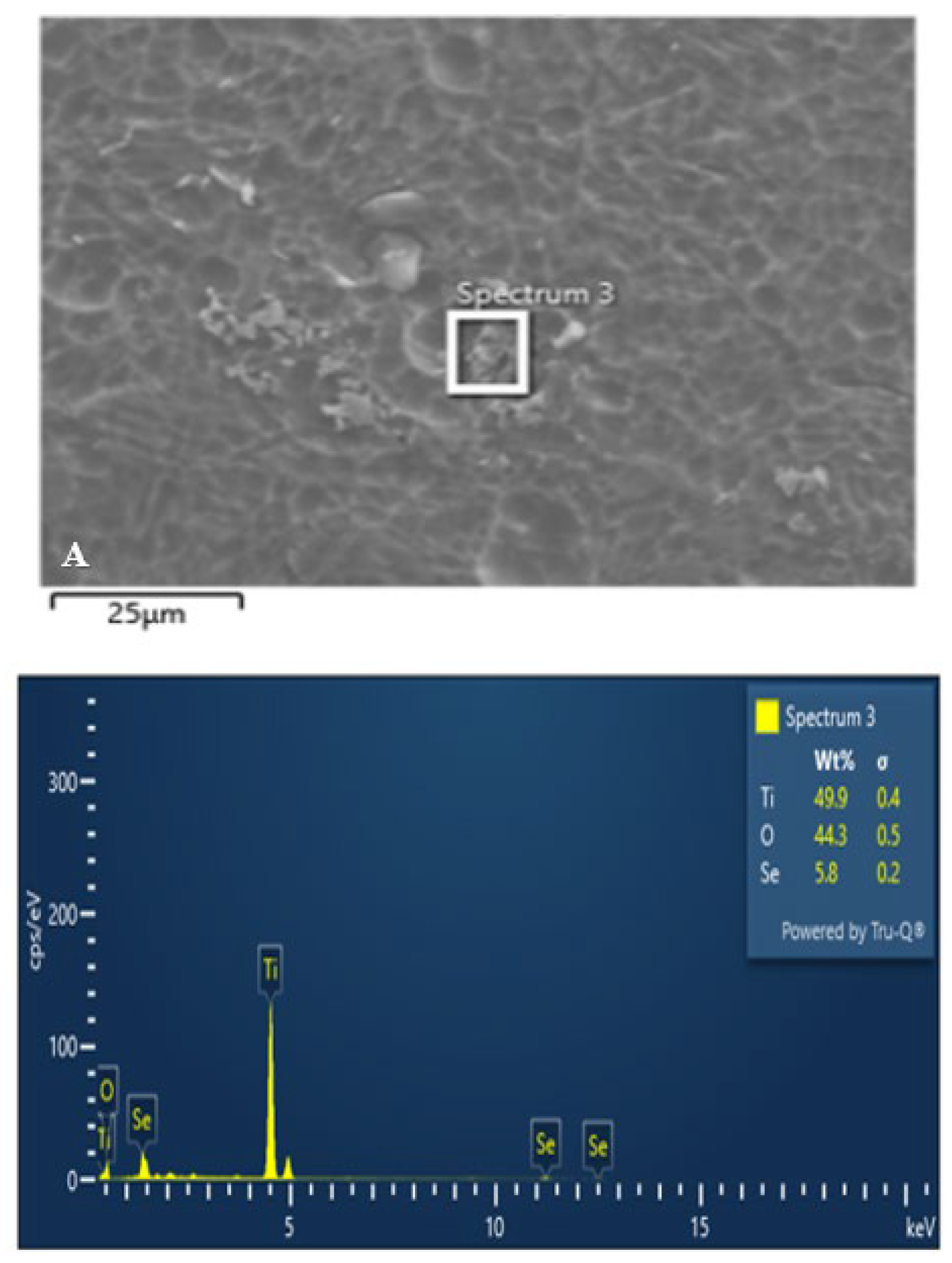

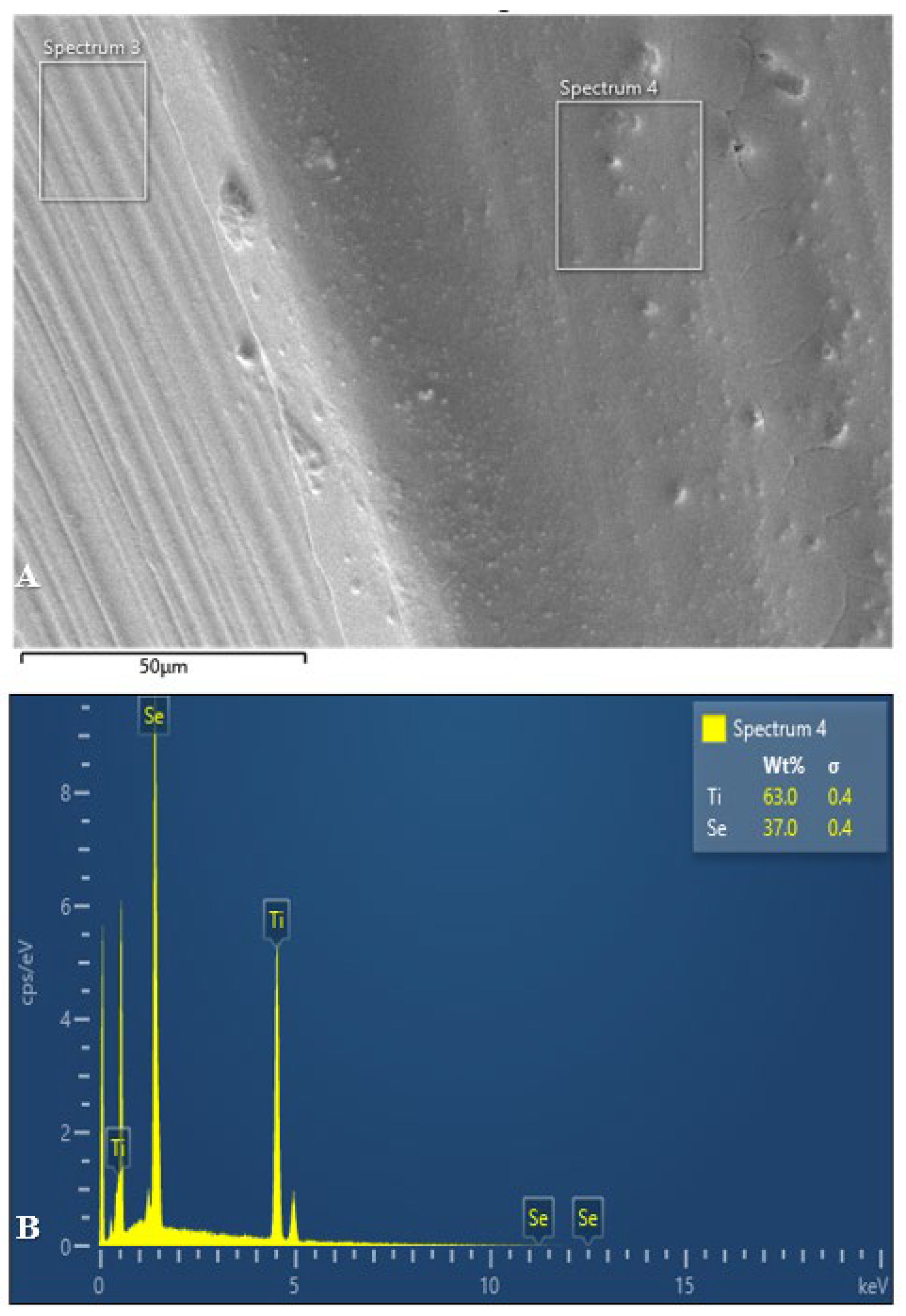

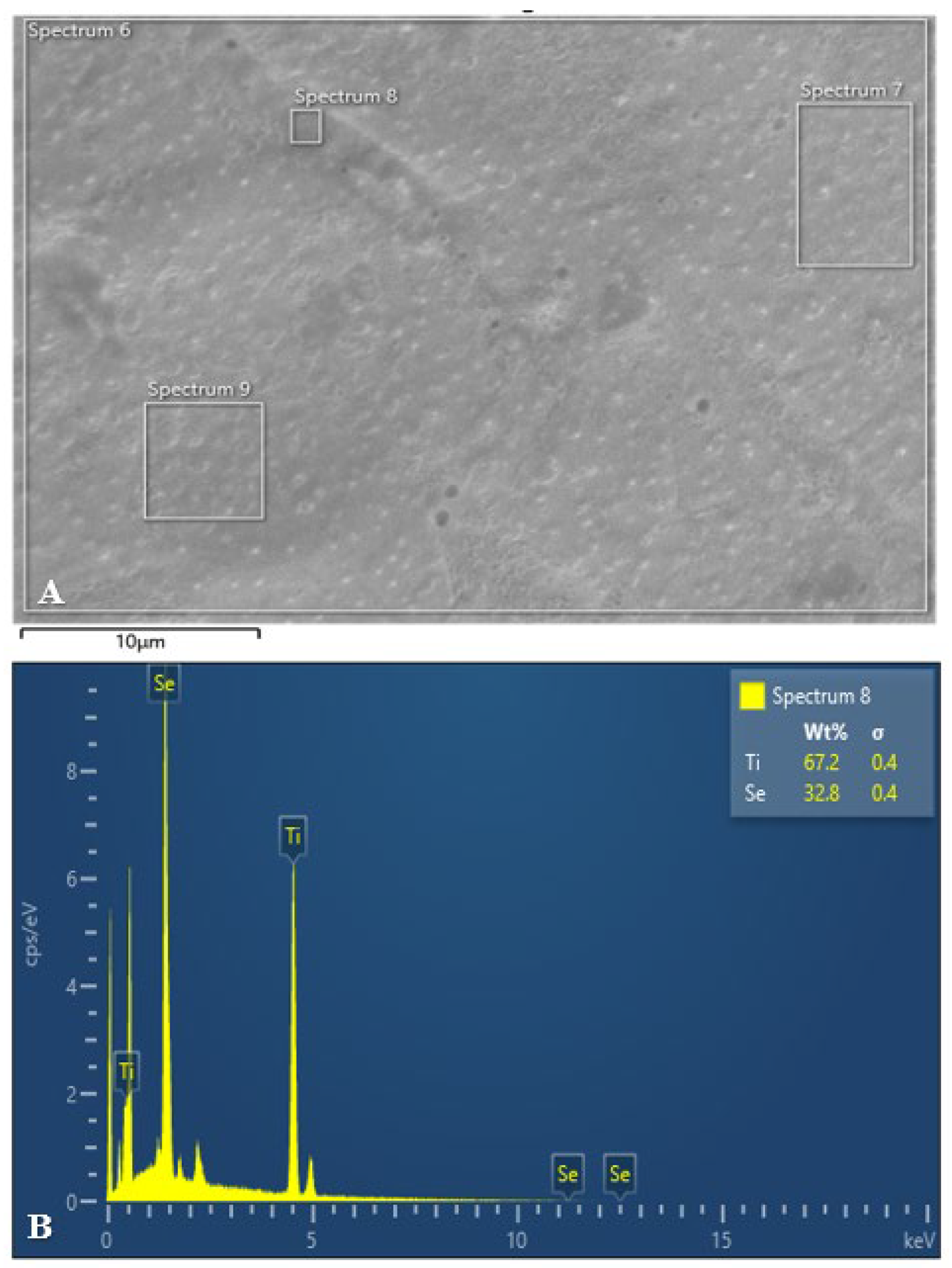

3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis

The following figures (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) present the SEM and EDX analyses of all test group samples treated with selenous acid.

It was noted that the percentage of selenium adsorption on the surface was uniform in Groups B and C. In contrast, Group A exhibited an irregular and non-uniform uptake, which may be attributed to the surface finish.

3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectorscopy (FTIR)

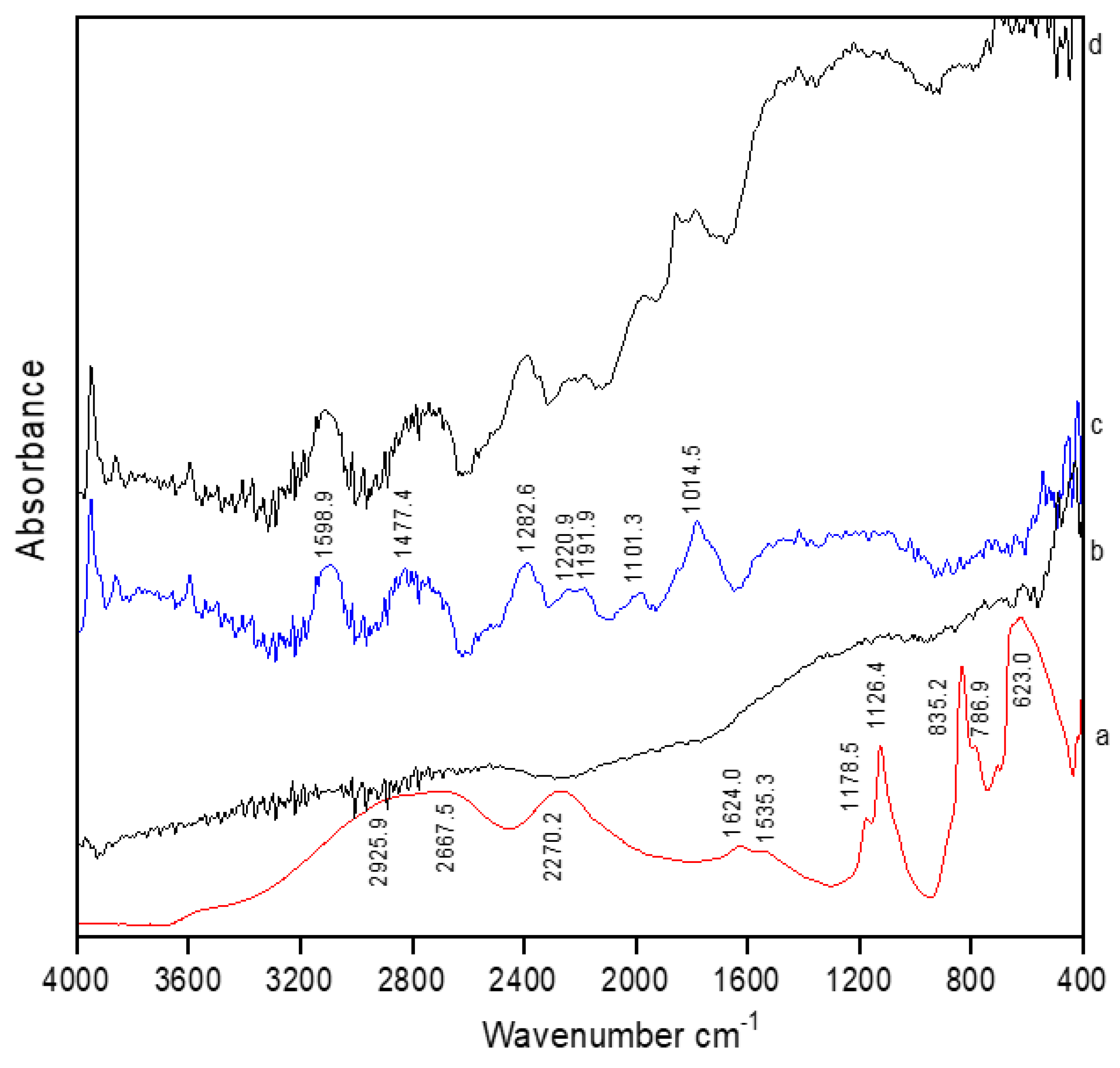

The following graph (

Graph 1) represents FTIR analysis of selenous acid for titanium plate & screw. Lines a,c, and d represent selenium coated titanium substrates of group A, B, and C respectively. Line b represents uncoated titanium substrate.

The absorption observed at 2925.0 and 2270.0 cm- 1 in line a is due to OH stretching mode of selenous signifying the presence and uptake of selenium in the sample. The significant O-H bending modes observed at 1178.5 and 1126.4 cm-1 in line c further confirms the activity of selenium.

The selenium oxide (Se-O) stretching mode observed at 835.0 and 623.0 cm-1 in all three groups further confirms the findings. The observed vibrational frequencies of selenous acid matches with the reported values in literature [

20].

3.3. Scratch Test

Table 1 shows the results for scratch force and penetration depth measurements demonstrating significant differences among all the test groups.

Significant differences were observed among the groups regarding scratch force, with Group A exhibiting the highest mean scratch force (21.156 N) compared to Groups B and C. Similarly, Group A showed the greatest mean penetration depth (37.113 microns), followed by Groups B and C. These results indicate distinct performance characteristics among the tested groups for both penetration depth and scratch force.

3.4. Antimicrobial Efficacy

The colony forming units (CFU) for test and control samples analysed using unpaired t-tests for each organism across different groups revealed the following: for

Escherichia coli, no significant difference was found between the control and test samples for group B & group A, indicated by p-values of 0.260 and 0.016, respectively. However, for group C, a significant difference was observed (p = 0.047), suggesting a potential impact of the test conditions on

Escherichia coli CFU counts. For

Streptococcus salivarius,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Staphylococcus aureus, significant differences were observed between control and test samples across all groups, as indicated by p-values less than 0.05 or 0.016 (

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Initially, miniplates and screws made up of stainless-steel material were commonly used for fracture fixation [

21]. While stainless steel materials are cost-effective and exhibit excellent ductility, tensile strength, and compressive strength, they have several limitations in terms of corrosion resistance, biocompatibility, fatigue limit, infection rate, and wear resistance limiting their usage in fracture fixation. However, with the introduction of titanium materials, the field of maxillofacial reconstruction was revolutionized [

22]. Compared to stainless steel, titanium alloys exhibit a lower modulus of elasticity, higher strength, excellent biocompatibility, less infection rate, and superior corrosion resistance [

23].

These favourable properties have led to their extensive use in clinical applications as bone plate materials [

24]. Despite the numerous advantages of titanium plates over stainless steel plates, there remains a significant rate of implant removal performed (10-40%) that requires attention [

25,

26]. Miniplate removal may be necessitated by various factors, including infection, wound dehiscence, palpability, aesthetic concerns, patient discomfort, and neurosensory disturbances [

27,

28].

Among these factors, postoperative infection is the most preventable cause. Although titanium materials have shown reduced incidence of postoperative infection compared to stainless materials, the rates are still of significance and concern [

29]. Infection of plates and screws may arise as a result of insufficient surgical sterility, inadequate postoperative care, and the implant material’s lack of inherent antimicrobial property.

Novel compounds with antimicrobial properties have been tried as coating over the maxillofacial implant substrates [

30,

31,

32]. Recently, selenium, a trace essential metalloid element, has emerged as a promising antimicrobial material. Selenium has garnered significant attention due to its desirable properties, including high absorption, high biological activity, and excellent biocompatibility. The superior antimicrobial capability of selenium may be attributed to cell membrane damage, inhibition of amino acid synthesis, and DNA replication caused by the overproduction of reactive oxygen species [

33,

34].

Therefore, this in vitro study was undertaken to evaluate both the antimicrobial efficacy and the surface changes resulting from selenium coating on titanium miniplates and screws. The presence of selenium over titanium miniplates and screws was confirmed by the appearance of spherical to cuboidal molecules over the surface at 10µm and 25µm magnification in all the three test groups. However, scanning electron microscopy allows for quantitative surface assessment of coated samples. But to effectively assess the chemical functionalisation of selenium and titanium, Fourier Transformer Infra -Red (FTIR) spectroscopy and Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) were used in this study.

In the current study, the surface functionalisation of selenium with titanium was proved with Fourier Transformer Infra-Red (FTIR) spectroscopy and Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis. The coated miniplates and screws from all the three groups showed varying amounts of selenium present with Group C showing maximum uptake (Figure). Furthermore, coated screws showed more selenium absorption when compared to coated plates in all the three groups which may be attributed to the difference in surface area.

In general, according to literature, postoperative infection is the most common indication for plate removal. Ironically, it is also the most preventable. Some authors advocate the routine removal of miniplates and screws to avoid this potential undesirable complication [

35,

36]. A variety of microorganisms have been associated with infection of miniplates in the maxillofacial region [

37]. The challenge lies in the ability to distinguish and cultivate these locally clustered bacteria because they are frequently metabolically inactive.

Thus, an implant material that has antibacterial characteristics while still preserving acceptable mechanical qualities and biocompatibility is desirable. The results of this study show that selenium as a surface coating can significantly reduce the bacterial colony count of Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Streptococcus salivarius, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa on titanium miniplates and screws.

The concentration of selenium used in this study at which significant bacterial load reduction occurred is relatively less compared to the value reported by Wang and Webster et al and Tran PA et al [

38,

39].

One of the most important characteristics of surface coating is its close adherence to the underlying material. Thus, to evaluate surface adherence as well as the strength of selenium coating, scratch tests were performed. In the current study, surface changes indicating removal of selenium coating was observed in the range of 10-20 newton with Group A showing highest resistance. Forces in the range of 100-200 newton are observed to torque screws and plates in desired position [

40]. This in comparison with forces at which selenium coating shows surface changes is significantly less. This may signify the suitability of selenium coated plates and screws for self-drilling systems may be of limited use.

On assessing the depth of penetration, the surface coating was observed to be of mean thickness of 30 microns with Group A demonstrating the maximum thickness (37.113 microns). Thus, we demonstrated that selenium coatings exhibit excellent adhesion to the underlying titanium substrate; however, their capacity to withstand substantial forces may be questionable.

Furthermore, clinical trials are necessary to ascertain the definitive antimicrobial effects of these selenium-coated plates and screws to support their broader application. Further research into optimizing the surface coating protocol could enhance efficacy while minimizing surface alterations of these plates and screws. Moreover, investigating the incorporation of selenium into the titanium substrates, rather than merely surface coating, could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the material’s effectiveness.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes a proof of concept that selenium coating on titanium miniplates and screws may offer significant advantages. Although the selenium coatings demonstrated good adherence, they may not withstand substantial forces, indicating potential limitations for self-drilling applications. Importantly, selenium coated titanium plates and screws showed a significant reduction in bacterial colony counts of common pathogens, including Streptococcus salivarius, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli. Overall, selenium appears to be a promising antimicrobial coating for titanium implants, with the potential to reduce infection rates and subsequently lower the incidence of miniplate removal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Vishal Ramachandran, Deepak Chandrasekaran, Ravindran Chinnasamy and Naveen Kumar Jayakumar; Data curation, Vishal Ramachandran; Formal analysis, Vishal Ramachandran, Ravindran Chinnasamy and Naveen Kumar Jayakumar; Investigation, Deepak Chandrasekaran, Ravindran Chinnasamy and Naveen Kumar Jayakumar; Methodology, Vishal Ramachandran, Deepak Chandrasekaran, Ravindran Chinnasamy and Naveen Kumar Jayakumar; Resources, Naveen Kumar Jayakumar; Supervision, Deepak Chandrasekaran, Ravindran Chinnasamy and Naveen Kumar Jayakumar; Visualization, Deepak Chandrasekaran; Writing – original draft, Vishal Ramachandran, Deepak Chandrasekaran, Ravindran Chinnasamy and Naveen Kumar Jayakumar; Writing -review & editing, Vishal Ramachandran, Deepak Chandrasekaran, and Ravindran Chinnasamy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hussain, K.B.; Wijetunge, D.B.M.; Grubnic, S.M.; Jackson, I.T.M. A Comprehensive Analysis of Craniofacial Trauma. 1994, 36, 34–47. [CrossRef]

- Oikarinen, K.S. Clinical management of injuries to the maxilla, mandible, and alveolus. Dent. Clin. North Am. 1995, 39, 113–131. [CrossRef]

- Michelet FX, Deymes J, Dessus B. Osteosynthesis with miniaturized screwed plates in maxillo-facial surgery. J Maxillofac Surg. 1973 Jan;1:79–84. [CrossRef]

- Champy, M.; Loddé, J.; Schmitt, R.; Jaeger, J.; Muster, D. Mandibular osteosynthesis by miniature screwed plates via a buccal approach. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 1978, 6, 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Ergun, S.; Ofluoğlu, D.; Saruhanoğlu, A.; Karataşli, B.; Deniz, E.; Özel, S.; TANYERI, H. Comparative evaluation of various miniplate systems for the repair of mandibular corpus fractures. Dent. Mater. J. 2014, 33, 368–372. [CrossRef]

- Matthew, I.R.; Frame, J.W. Ultrastructural analysis of metal particles released from stainless steel and titanium miniplate components in an animal model. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1998, 56, 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Bessho, K.; Iizuka, T. Clinical and animal experiments on stress corrosion of titanium miniplates. Clin. Mater. 1993, 14, 223–227. [CrossRef]

- Torgersen, S.; Gilhuus-Moe, O.T.; Gjerdet, N.R. Immune response to nickel and some clinical observations after stainless steel miniplate osteosynthesis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1993, 22, 246–250. [CrossRef]

- Voggenreiter, G.; Leiting, S.; Brauer, H.; Leiting, P.; Majetschak, M.; Bardenheuer, M.; Obertacke, U. Immuno-inflammatory tissue reaction to stainless-steel and titanium plates used for internal fixation of long bones. Biomaterials 2002, 24, 247–254. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Takenoshita, Y.; Oka, M. Complications of miniplate osteosynthesis for mandibular fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1994, 52, 233–238. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Patil, P.M. Titanium osteosynthesis hardware in maxillofacial trauma surgery: to remove or remain? A retrospective study. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2013, 40, 587–591. [CrossRef]

- Zirk, M.; Markewitsch, W.; Peters, F.; Kröger, N.; Lentzen, M.-P.; Zoeller, J.E.; Zinser, M. Osteosynthesis-associated infection in maxillofacial surgery by bacterial biofilms: a retrospective cohort study of 11 years. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 4401–4410. [CrossRef]

- Linder, L.; Carlsson, A.; Marsal, L.; Bjursten, L.; Branemark, P. Clinical aspects of osseointegration in joint replacement. A histological study of titanium implants. J. Bone Jt. Surgery. Br. Vol. 1988, 70-B, 550–555. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, L.; Mustapha, A.; Li, H.; Hu, Z.; Lin, M. Antibacterial activities of zinc oxide nanoparticles against Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 1193–1201. [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.; Yadav, A.; Gade, A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 76–83. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H. Elemental selenium at nano size possesses lower toxicity without compromising the fundamental effect on selenoenzymes: Comparison with selenomethionine in mice. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 42, 1524–1533. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.-F.; Pi, J. The Advancing of Selenium Nanoparticles Against Infectious Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 682284. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.S.; Baker, D.H.A.; Ahmed, E.A. Cytotoxicity and antimicrobial efficiency of selenium nanoparticles biosynthesized by Spirulina platensis. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 523–532. [CrossRef]

- Holinka J, Pilz M, Kubista B, Presterl E, Windhager R. Effects of selenium coating of orthopaedic imp lant surfaces on bacterial adherence and osteoblastic cell growth. Bone Joint J. 2013 May;95-B(5):678–82. [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.; Giguère, P.A. Infrared spectra and structure of selenious acid. Can. J. Chem. 1958, 36, 1680–1685. [CrossRef]

- Pacifici L, DE Angelis F, Orefici A, Cielo A. Metals used in maxillofacial surgery. Oral Implantol (Rome). 2016;9(Suppl 1/2016 to N 4/2016):107–11. [CrossRef]

- Gilardino, M.S.; Chen, E.; Bartlett, S.P. Choice of Internal Rigid Fixation Materials in the Treatment of Facial Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2009, 2, 49–60. [CrossRef]

- Geetha M, Singh AK, Asokamani R, Gogia AK. Ti based biomaterials, the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants – A review. Prog Mater Sci. 2009 May;54(3):397 –425. [CrossRef]

- Acero, J.; Calderon, J.; Salmeron, J.I.; Verdaguer, J.J.; Concejo, C.; Somacarrera, M.L. The behaviour of titanium as a biomaterial: microscopy study of plates and surrounding tissues in facial osteosynthesis. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 1999, 27, 117–123. [CrossRef]

- Nagase, D.Y.; Courtemanche, D.J.M.; Peters, D.A. Plate Removal in Traumatic Facial Fractures. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2005, 55, 608–611. [CrossRef]

- O’connell, J.; Murphy, C.; Ikeagwuani, O.; Adley, C.; Kearns, G. The fate of titanium miniplates and screws used in maxillofacial surgery: A 10 year retrospective study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 38, 731–735. [CrossRef]

- Rauso R, Tartaro G, Stea S, Tozzi U, Biondi P. Plates removal in orthognathic surgery and facial fractures: When and why. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2011 Jan;22(1):252–4. [CrossRef]

- Sukegawa S, Masui M, Sukegawa-Takahashi Y, Nakano K, Takabatake K, Kawai H, et al. Maxillofacial Trauma Surgery Patients With Titanium Osteosynthesis Miniplates: Remove or Not? J Craniofac Surg. 2020 Jul 1;31(5):1338 –42. [CrossRef]

- Bakathir, A.A.; Margasahayam, M.V.; Al-Ismaily, M.I. Removal of bone plates in patients with maxillofacial trauma: a retrospective study. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2008, 105, e32–e37. [CrossRef]

- Juan, L.; Zhimin, Z.; Anchun, M.; Lei, L.; Jingchao, Z. Deposition of silver nanoparticles on titanium surface for antibacterial effect. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 261–267. [CrossRef]

- Kourai, H.; Yabuhara, T.; Shirai, A.; Maeda, T.; Nagamune, H. Syntheses and antimicrobial activities of a series of new bis-quaternary ammonium compounds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 41, 437–444. [CrossRef]

- Bergemann, C.; Zaatreh, S.; Wegner, K.; Arndt, K.; Podbielski, A.; Bader, R.; Prinz, C.; Lembke, U.; Nebe, J.B. Copper as an alternative antimicrobial coating for implants - an in vitro study. World J. Transplant. 2017, 7, 193–202. [CrossRef]

- Shakibaie, M.; Forootanfar, H.; Golkari, Y.; Mohammadi-Khorsand, T.; Shakibaie, M.R. Anti-biofilm activity of biogenic selenium nanoparticles and selenium dioxide against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus mirabilis. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 2015, 29, 235–241. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Dai, C.; Wang, P.; Fan, S.; Yu, B.; Qu, Y. Antibacterial properties and mechanism of selenium nanoparticles synthesized by Providencia sp. DCX. Environ. Res. 2020, 194, 110630. [CrossRef]

- Thorén, H.; Snäll, J.; Hallermann, W.; Kormi, E.; Törnwall, J. Policy of Routine Titanium Miniplate Removal After Maxillofacial Trauma. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 1901–1904. [CrossRef]

- Torgersen, S.; Gjerdet, N.R. Retrieval study of stainless steel and titanium miniplates and screws used in maxillofacial surgery. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1994, 5, 256–262. [CrossRef]

- Vishal; Rohit; Prajapati, V.; Shahi, A.K.; Prakash, O. Significance of microbial analysis during removal of miniplates at infected sites in the craniomaxillofacial region - An evaluative study. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 10, 330–334. [CrossRef]

- Tran PA, Webster TJ. Selenium nanoparticles inhibit Staphylococcus aureus growth. International journal of nanomedicine. 2011 Jul 29:1553-8. [CrossRef]

- A Tran, P.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.; A Palmer, J.; Bock, N.; Reynolds, E.C.; Webster, T.J.; Deva, A.; A Morrison, W.; O’Connor, A.J. Selenium nanoparticles as anti-infective implant coatings for trauma orthopedics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and epidermidis: in vitro and in vivo assessment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, ume 14, 4613–4624. [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.-C.; Wang, C.-H.; Wang, H.-C.; Lee, K.-T.; Lee, H.-E.; Chen, C.-M. A study of the mechanical strength of miniscrews and miniplates for skeletal anchorage. J. Dent. Sci. 2011, 6, 165–169. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).