Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

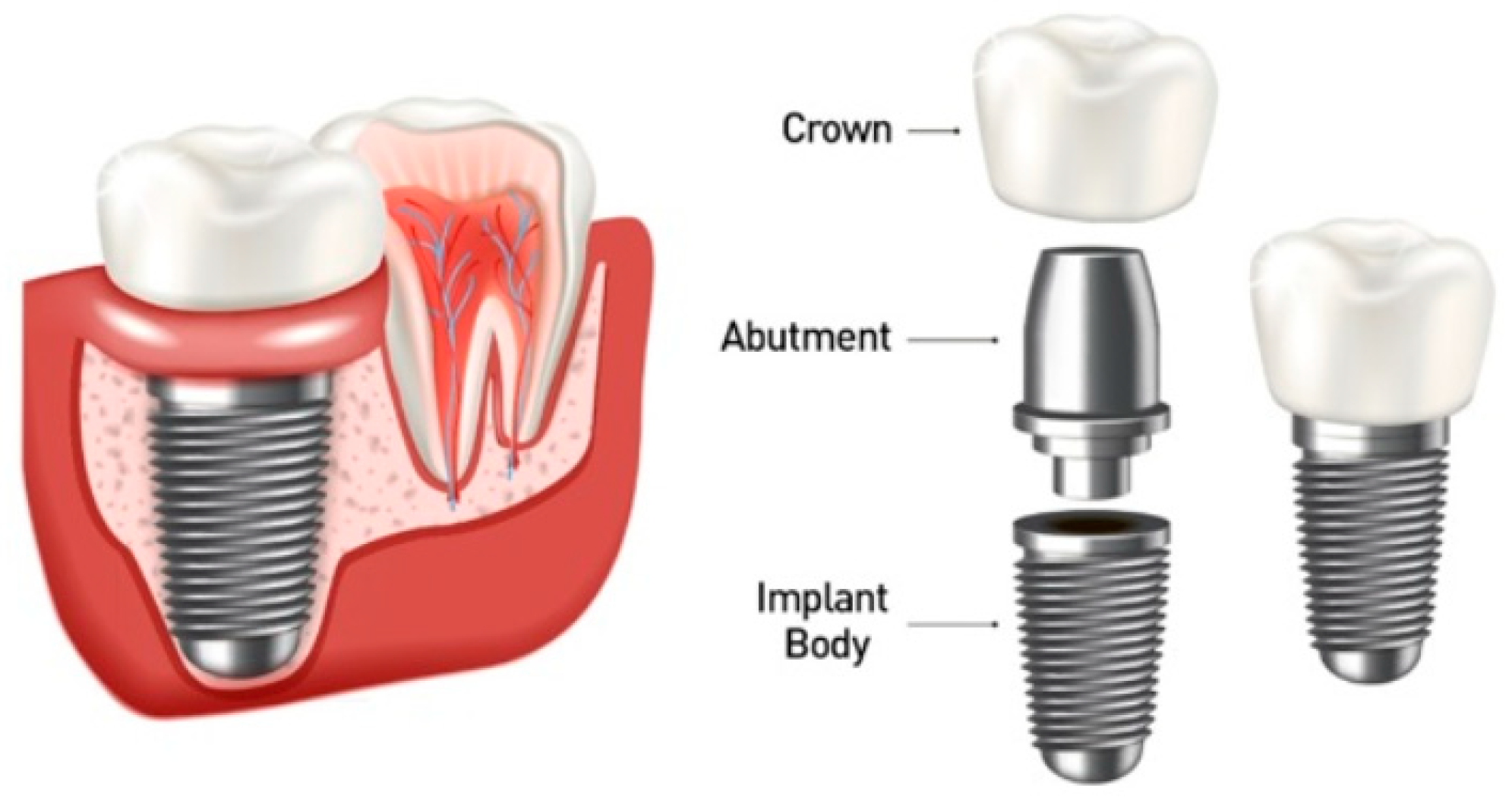

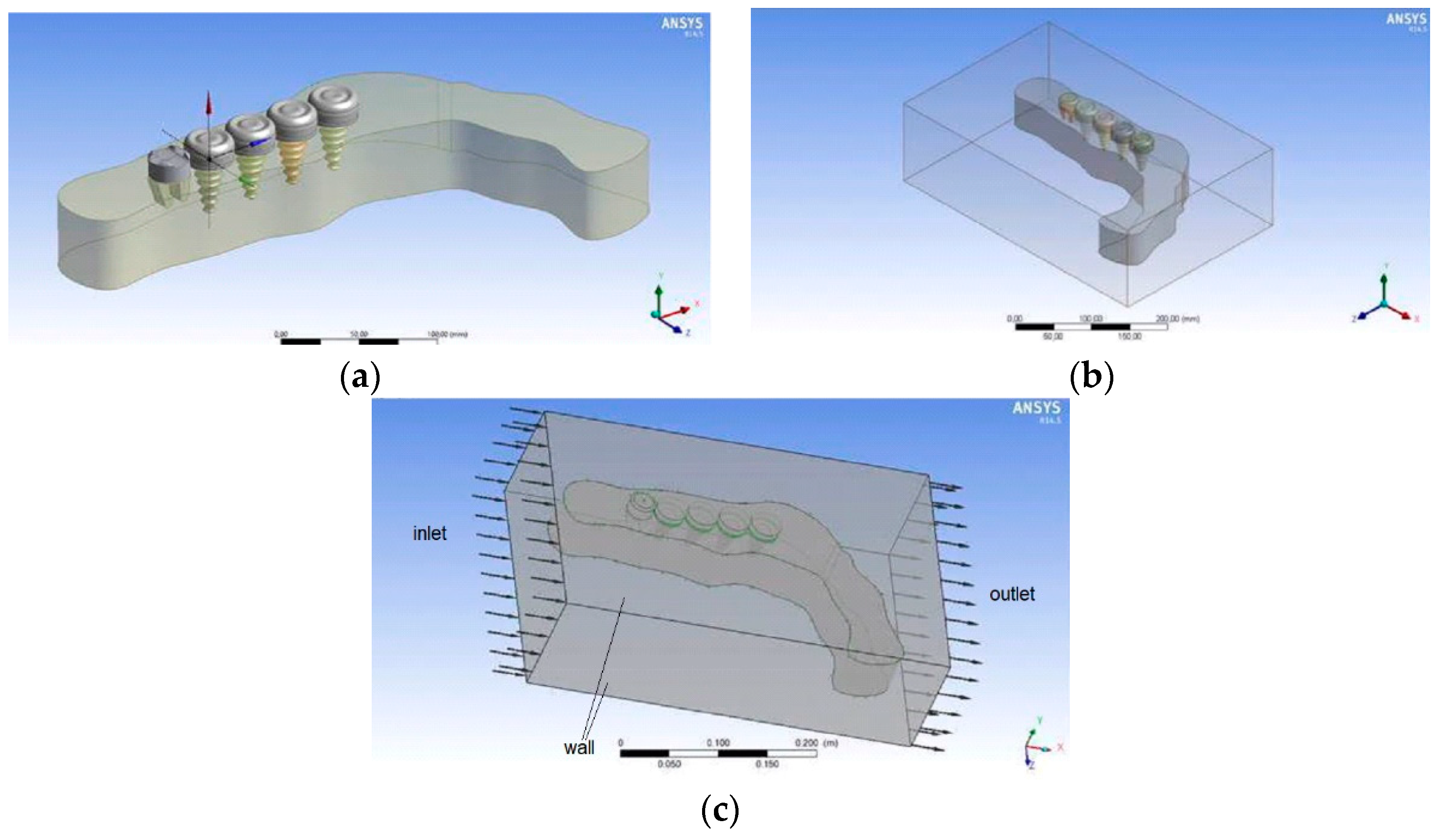

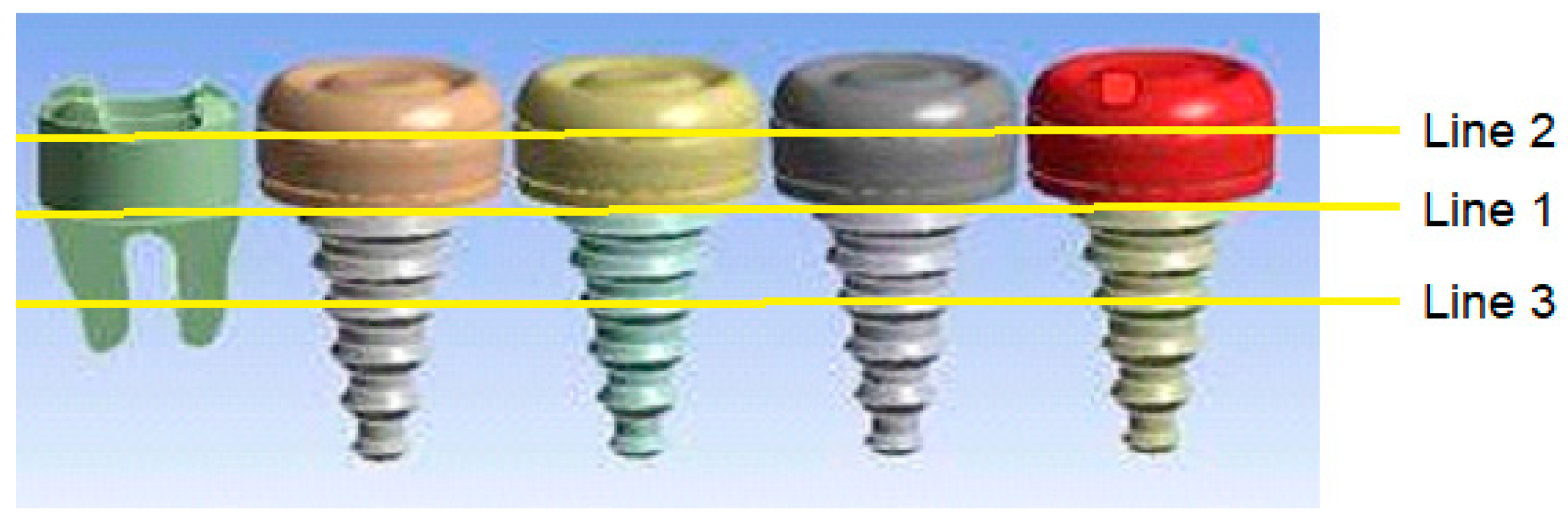

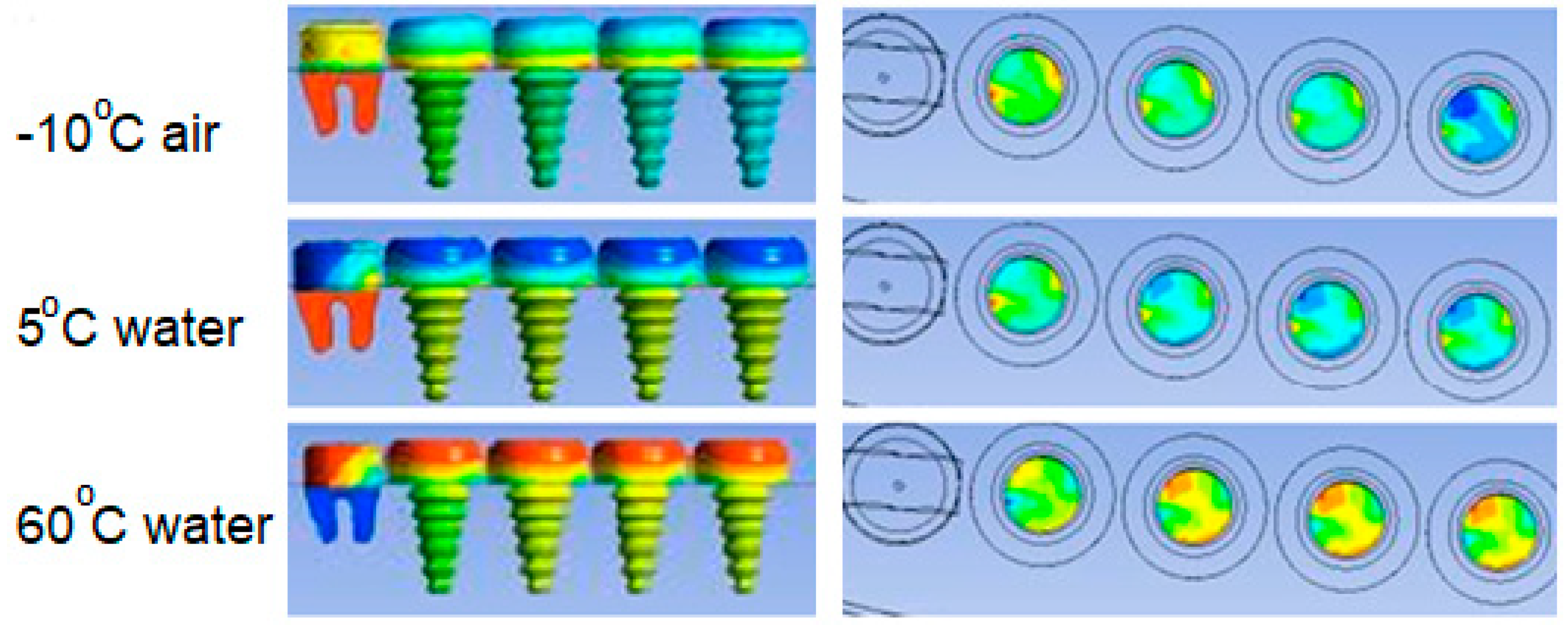

In this study thermal effects of hot and cold fluids on five teeth in the jawbone, one of which is the main tooth and other four are dental implants, are numerically investigated. Since a typical dental implant consists of an implant body, an abutment and a crown, the implant body and crown may be affected differently when they are made of different materials. Based on this reasoning, the cases where the implant body is made of titanium, zirconium, gold and cobalt and the crown is made of zirconium and porcelain are discussed numerically. It was considered as a positive criterion that the prosthetic implant duo, which was considered to be at body temperature at the beginning, were affected by the temperature under different thermal conditions. Therefore, as thermal conditions, the contact of cold (5 C) and hot (60 C) liquid beverages to the teeth and the effect of cold air (-10 C) contacting to the teeth with the breath taken in a cold air are examined. Numerical solutions are obtained by using commercial software ANSYS-CFX.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Numerical Method

2.3. Physical Model

3. Results

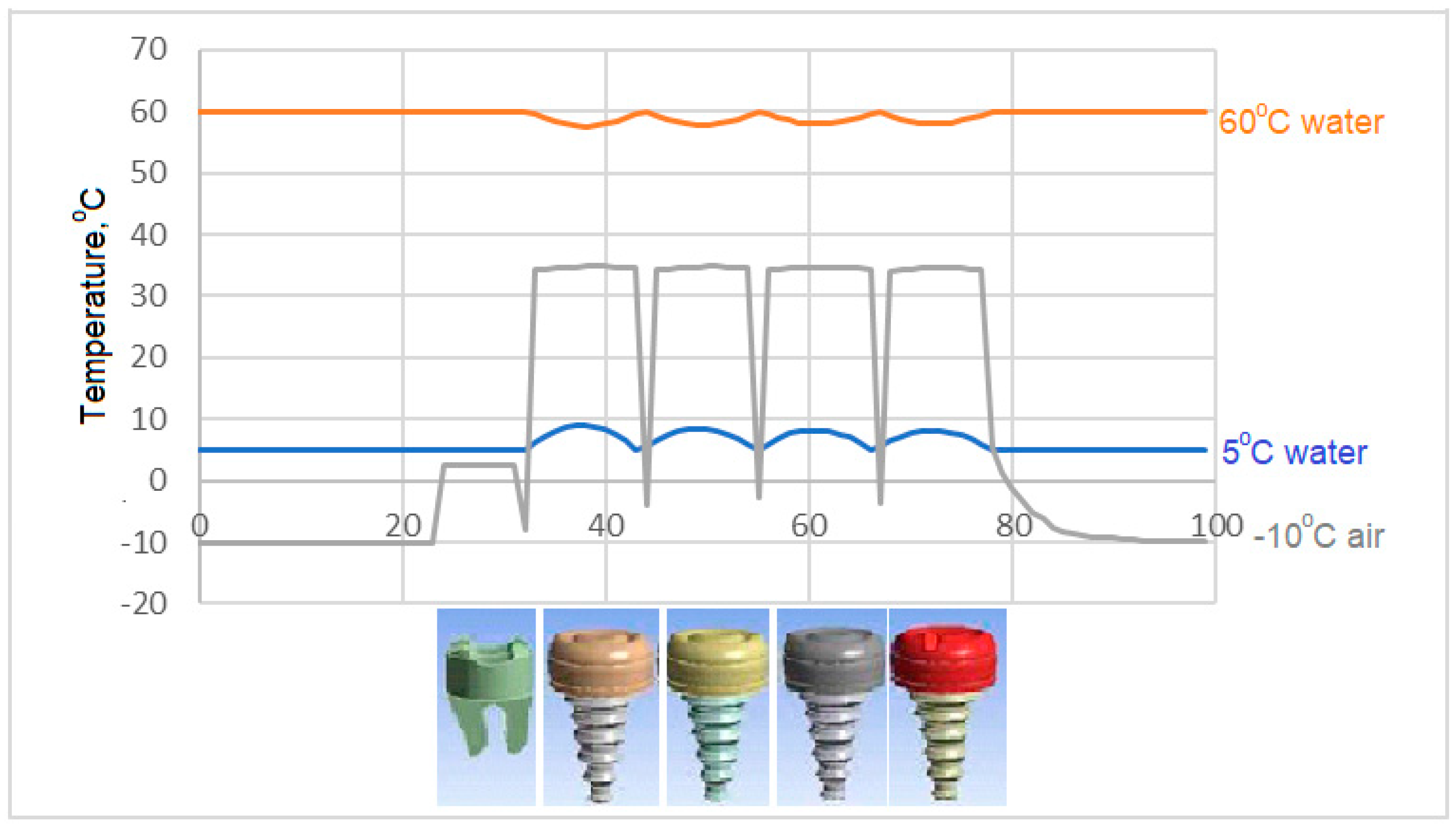

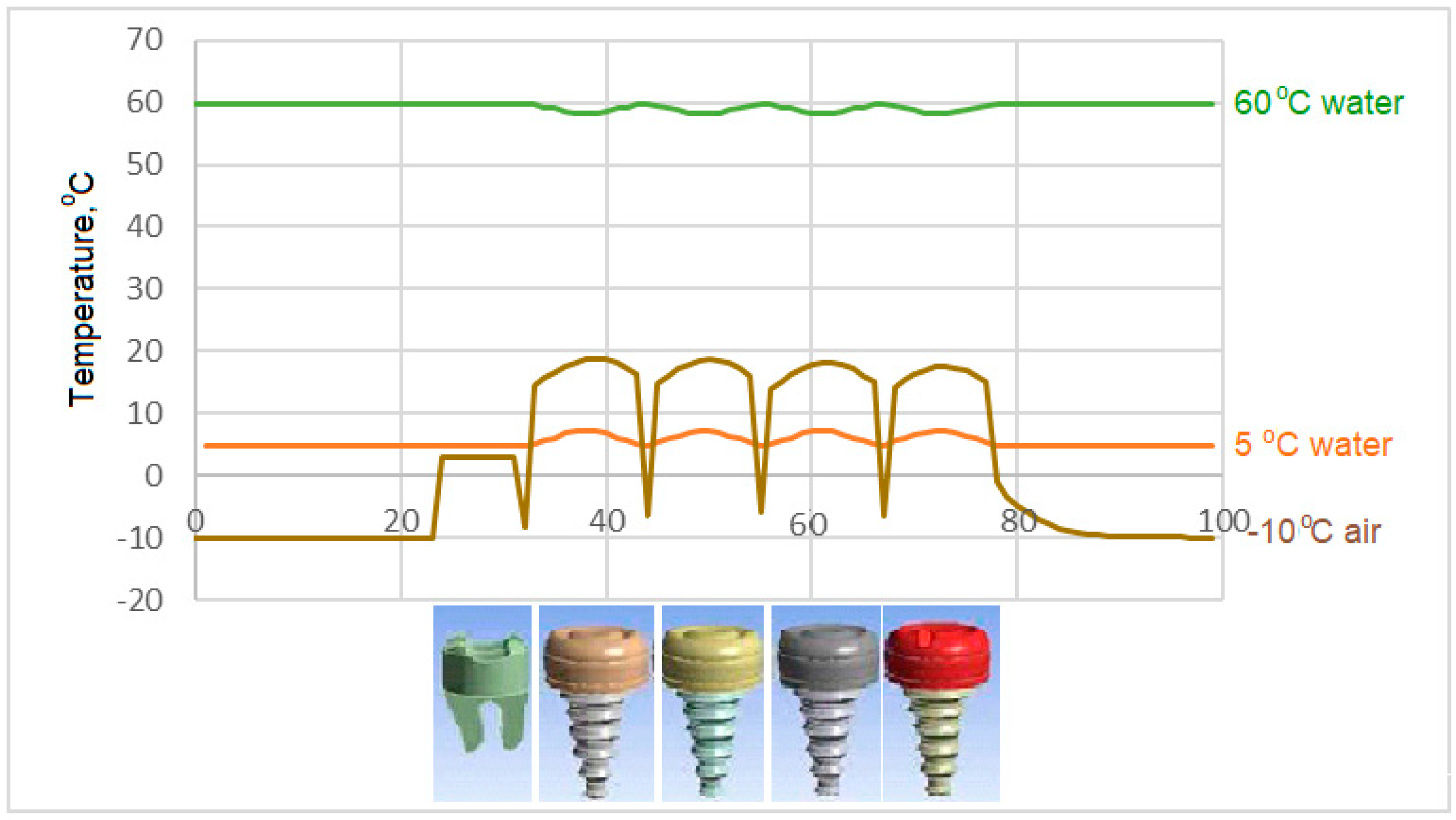

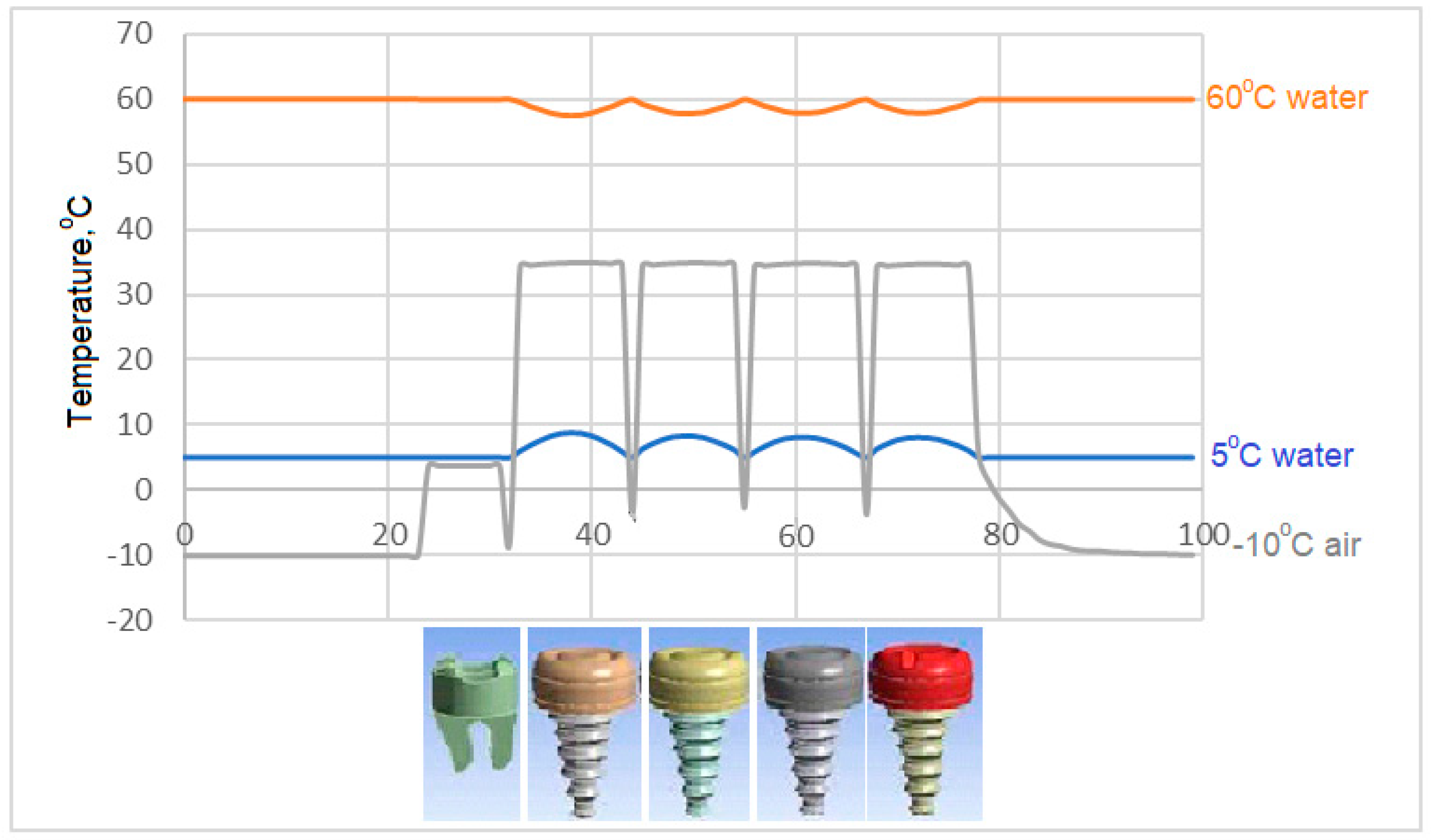

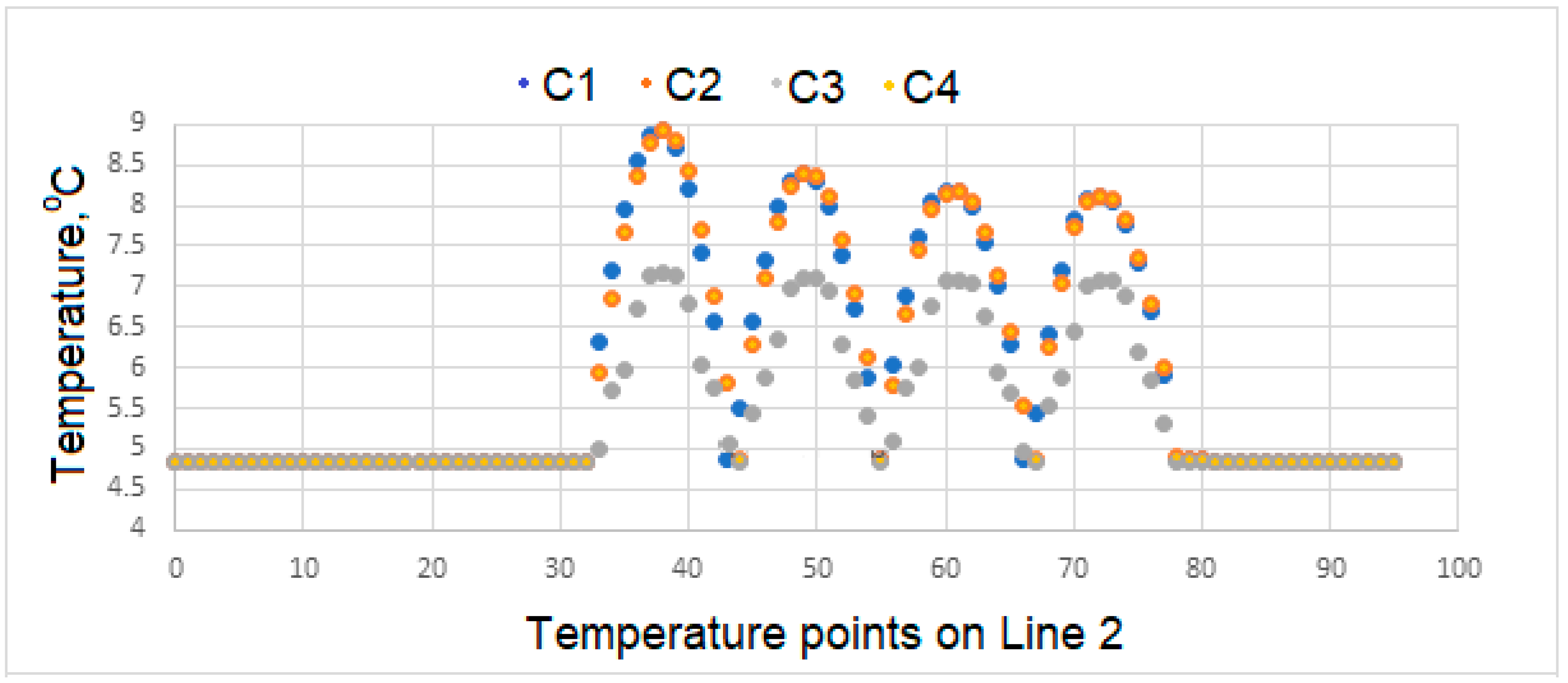

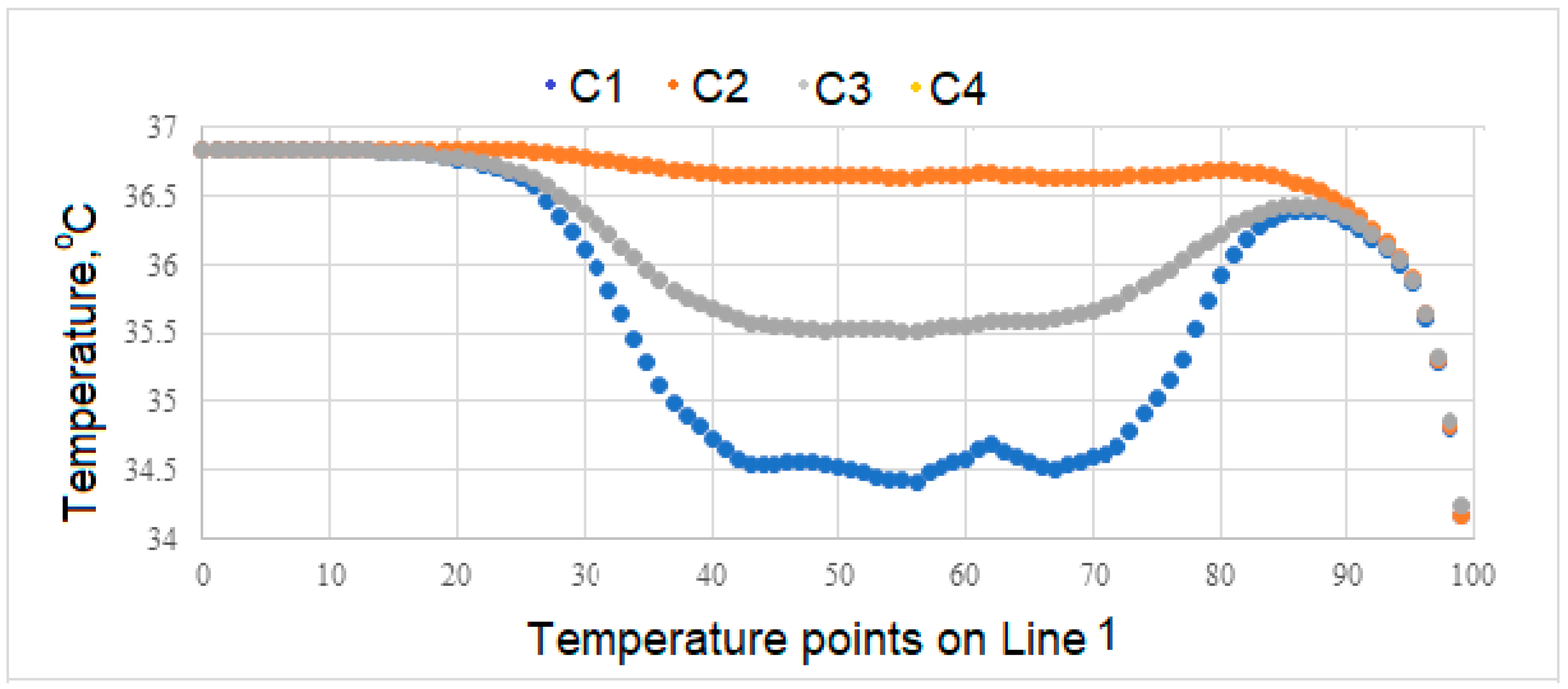

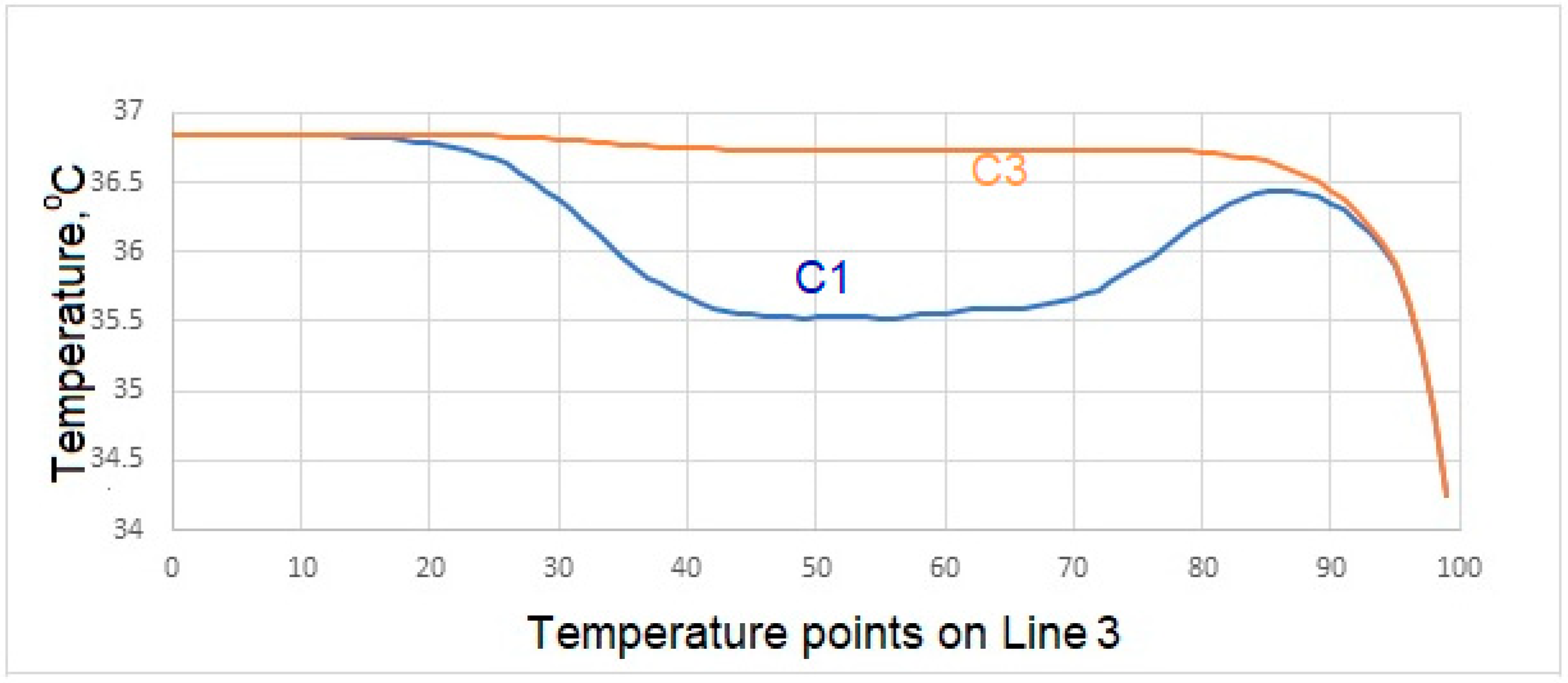

Variation of Surface Temperatures

4. Conclusions

- Temperatures on the upper surface of the tooth, which is initially considered to be at body temperature, is least affected, and that the temperatures at the interface, which is the junction of the crown and implant body, and temperature at the lower point of the implant are close to the temperatures of the natural tooth in the same region.

- In case of drinking water at 5 °C temperature, it is concluded that the porcelain used as crown material in C3 is not as suitable as the zirconium used as prosthetic material as in C1 and C4.

- During liquid contact at 60 °C, the zirconium material used as the crown material in the C4 model is found to be more successful than the porcelain, which is the crown material in the C3 model, since it is less affected by the temperature.

- The model in which the temperature of the crown decreases the most in case of contact with air at -10 °C is the model expressed in C3. The model with the least decrease in surface temperature is the C4 model, in which zirconium is used as the crown.

- In the case of drinking water at 5 °C, the greatest decrease in interface temperatures is seen in the crown and implant body expressed in C1 model. When the temperature distribution in C3 is examined, it is seen that the decrease is very small, and this result makes C3 more successful.

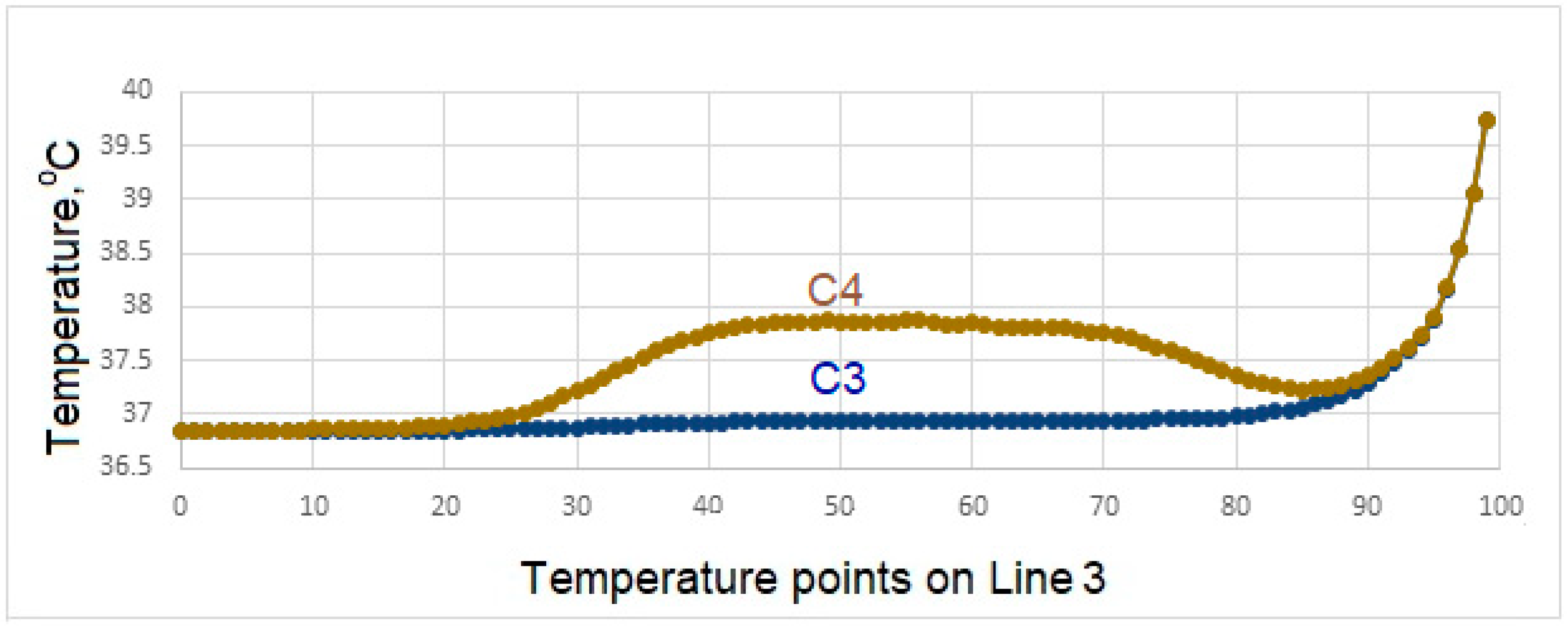

- In the case of drinking water at 60 °C, it is seen that there is no increase in the interface temperatures of the teeth designed in the C3 model, but it reaches a maximum of 38.5 °C in the C4 model. This result shows that the C3 model is more suitable at the interface.

- All of the models examined in air contact at -10 °C showed similar behavior in terms of temperature at the interfaces.

- Since there is a negligible (0.8 °C) temperature drop in the implant bodies of the model called C3 in contact with water at 5 °C, the C3 model is found to be successful under these conditions.

- In case of drinking water at 60 °C, the temperature of the implant screws of the C3 model increases up to a maximum of 36.93 °C. This situation can be interpreted as keeping the temperature constant and can be expressed as the success of the C3 model.

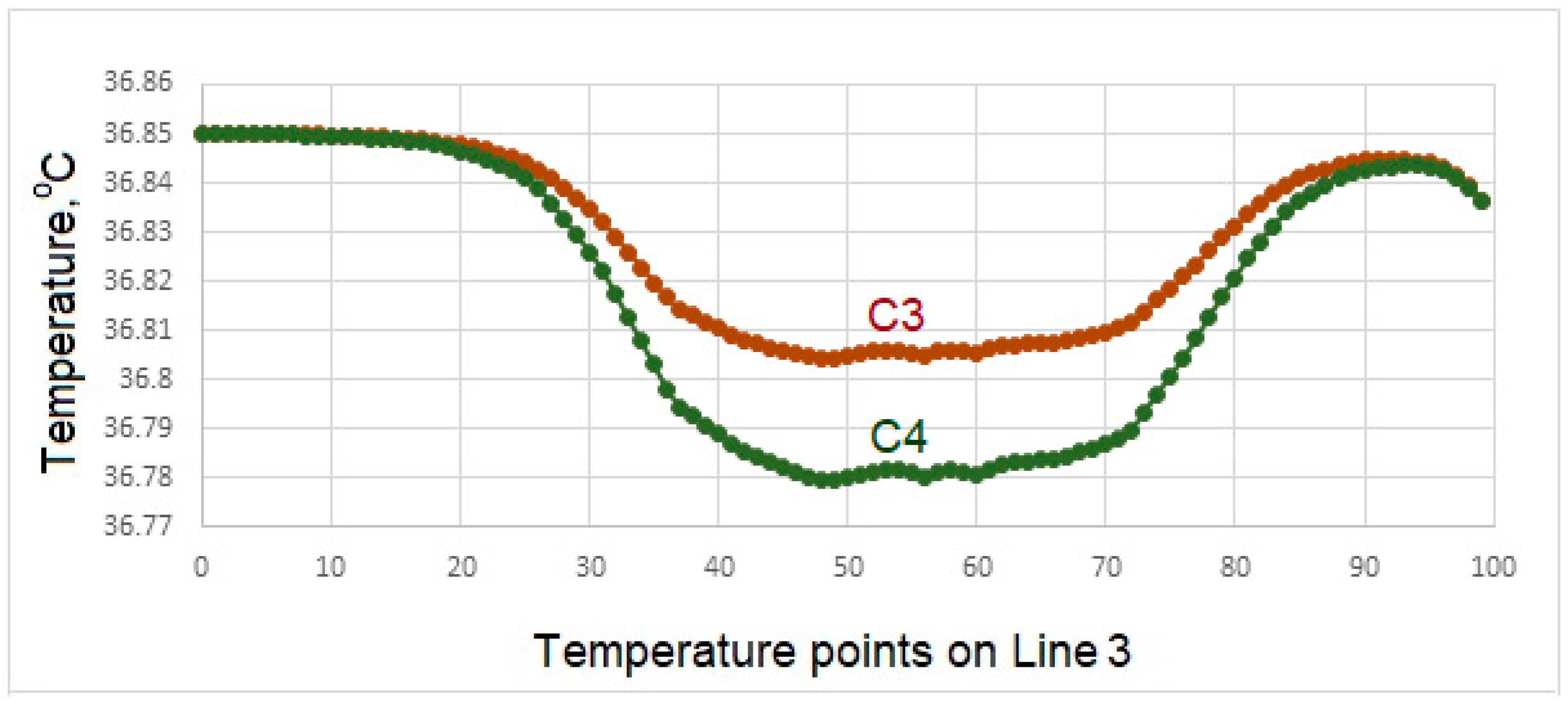

- Among the models examined in air contact at -10 °C, the temperature drop in the implant screw of C3 is at most 36.8 °C. In this case, it is concluded that the C3 model is more successful than the other models

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, X.; Yao, Y.; Tang, W.; Han, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, K.; Wang, S.; Meng, Y. Design of dental implants at materials level: An overview. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A., 2020, 108(8), 1634–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- URL: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/dental-devices/dental-implants-what-you-should-know (accessed on 23rd of February, 2023).

- Misch, C.E. Contemporary implant dentistry, 3rd ed.; Mosby Elsevier: USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, M.; Singh, Y.; Arora, P.; Arora, V.; and Jain, K. Implant biomaterials: A comprehensive review. World J Clin Cases 2015, 3(1), 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulbert, S.F.; Bennett, J.T. State of the art in dental implants. J Dent Res 1975, 54. Spec No B: B153–B157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Noort, R. ; Titanium: The implant material of today. Journal of Materials Science 1987, 22, 3801–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.S. Dental implants: the last 100 years. Journal of Oral and Maxillofasial Surgery 2017, 29079267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.J.; Bronzino, J.D. Biomaterials: principles and applications, 1st ed.; CRC Press: New York, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- de Cos Juez, F.J.; Sánchez, L.F.; García Nieto, P.J.; Álvarez-Arenal, A. Non-linear numerical analysis of a double-threaded titanium alloy dental implant by FEM. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2008, 206, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, D.; Dorogoya, A.; Haïat, G.; Shemtov-Yonaa, K. Resonant frequency analysis of dental implants. Medical Engineering & Physics 2019, 66, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Brune, A.; Stiesch, M.; Eisenburger, M.; Greuling, A. The effect of different occlusal contact situations on peri-implant bone stress - A contact finite element analysis of indirect axial loading. Materials Science and Engineering 2019, C99, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinel, S.; Celik, E.; Sagirkaya, E.; Onur, S. Experimental evaluation of stress distribution with narrow diameter implants: A finite element analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119(3), 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cant´o-Nav´es, O.; Marimon, X.; Ferrer, M.; Cabratosa-Termes, J. Comparison between experimental digital image processing and numerical methods for stress analysis in dental implants with different restorative materials. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2021, 113, 104092. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein, O.; Zeichner, K.; Imbari, C.; Ormianer, Z.; Samet, N.; Weiss, E. Temperature changes in dental implants following exposure to hot substances in an ex vivo model. Clinical Oral Implants Research 2008, 9(6), 629–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, C.W.; Spence, D.; Laird, W.R.E. ; Intra-oral temperatures during function. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2005, 32, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, R.S.; Oskui, Z.I.; Hashemi, A. ; Thermal analysis of dental implants in mandibular premolar region: 3D FEM study. J. Prosthodont., 2018, 27, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskui, I.Z.; Ashtiani, M.N.; Hashemi, A.; Jafarzadeh, H. Thermal analysis of the intact mandibular premolar: A finite element analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2013, 46, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koycu, C.; Imirzalioglu, B.P. Heat transfer and thermal stress analysis of a mandibular molar tooth restored by different indirect restorations using a three-dimensional finite element eethod. J. Prosthodont 2007, 26, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, I.S.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, T.J.; Kim, S.K.; Heo, S.J.; Koak, J.Y.; Park, J.M.; Lee, S.Y. The effect of abutment screw length on screw loosening in dental implants with external abutment connections after thermocycling. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant 2014, 29, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Lee, H.P.; Lu, C. ; Thermal-mechanical study of functionally graded dental implants with the finite element method. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 80, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Fluid | Temp (oC) |

Density (kg/m3 ) |

Dynamic viscosity (kg/ms) |

Thermal conductivity (W/mK) | Specific heat (J/kgK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 5 | 999.9 | 1.519x10-3 | 0.571 | 4205 |

| Water | 60 | 983.3 | 0.467x10-3 | 0.654 | 4185 |

| Air | -10 | 1.341 | 1.680x10-5 | 0.02288 | 1006 |

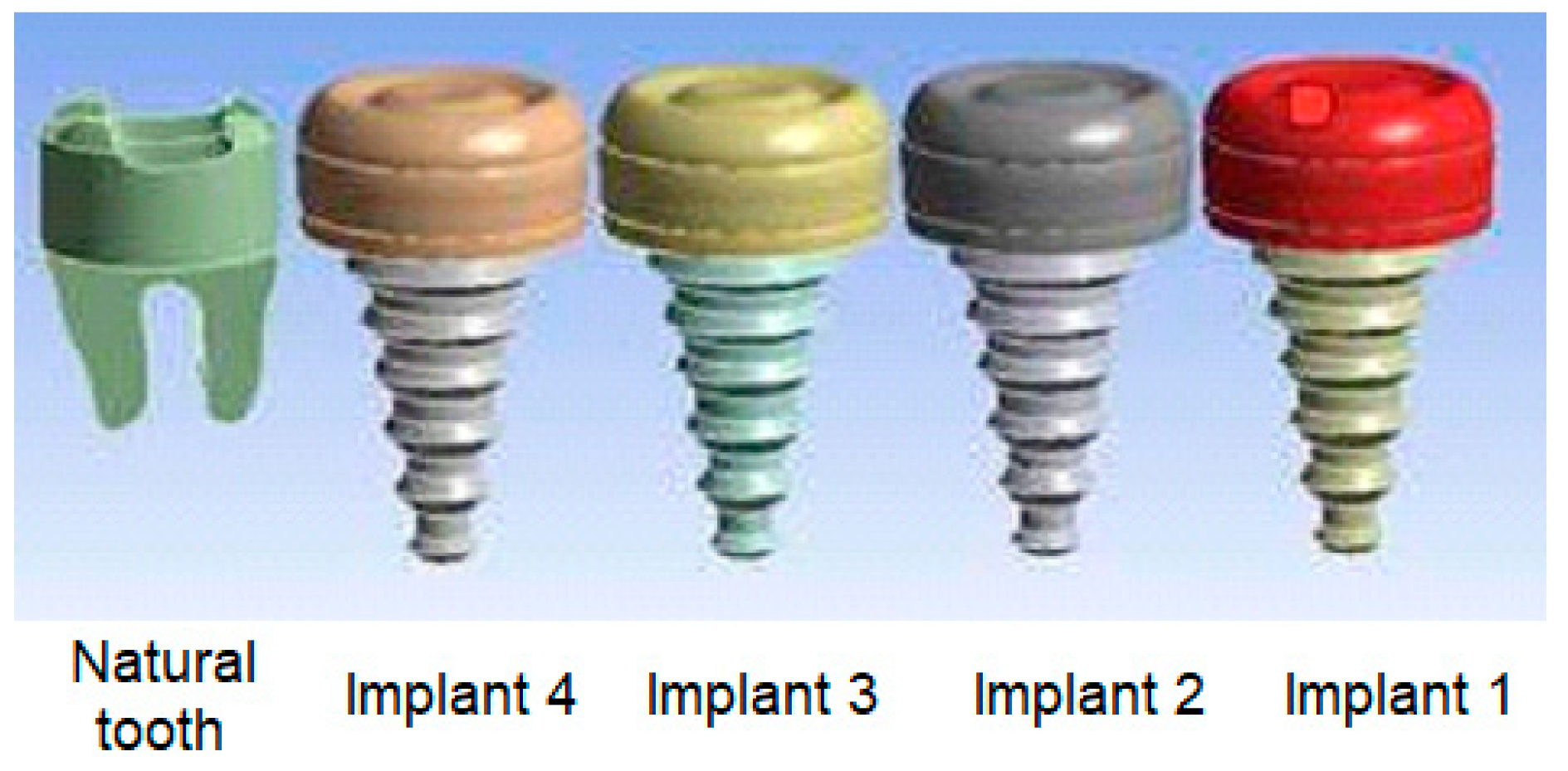

| Cases | Parts of dental implant | Implant 1 | Implant 2 | Implant 3 | Implant 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Implant body | Zirconium | Zirconium | Titanium | Titanium |

| Crown | Zirconium | Zirconium | Zirconium | Zirconium | |

| C2 | Implant body | Gold | Gold | Zirconium | Zirconium |

| Crown | Zirconium | Zirconium | Zirconium | Zirconium | |

| C3 | Implant body | Gold | Gold | Titanium | Titanium |

| Crown | Porcelain | Porcelain | Porcelain | Porcelain | |

| C4 | Implant body | Cobalt | Cobalt | Zirconium | Zirconium |

| Crown | Zirconium | Zirconium | Zirconium | Zirconium |

| Implant body & crown | Density ρ (kg/m3) |

Thermal conductivity k (W/mK) |

Specific heat Cp (J/kgK) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium | 4500 | 22 | 522 |

| Zirconium | 6570 | 22.7 | 278 |

| Gold | 19300 | 317 | 129 |

| Cobalt | 8862 | 99.2 | 421 |

| Porcelain | 2300 | 1.5 | 1085 |

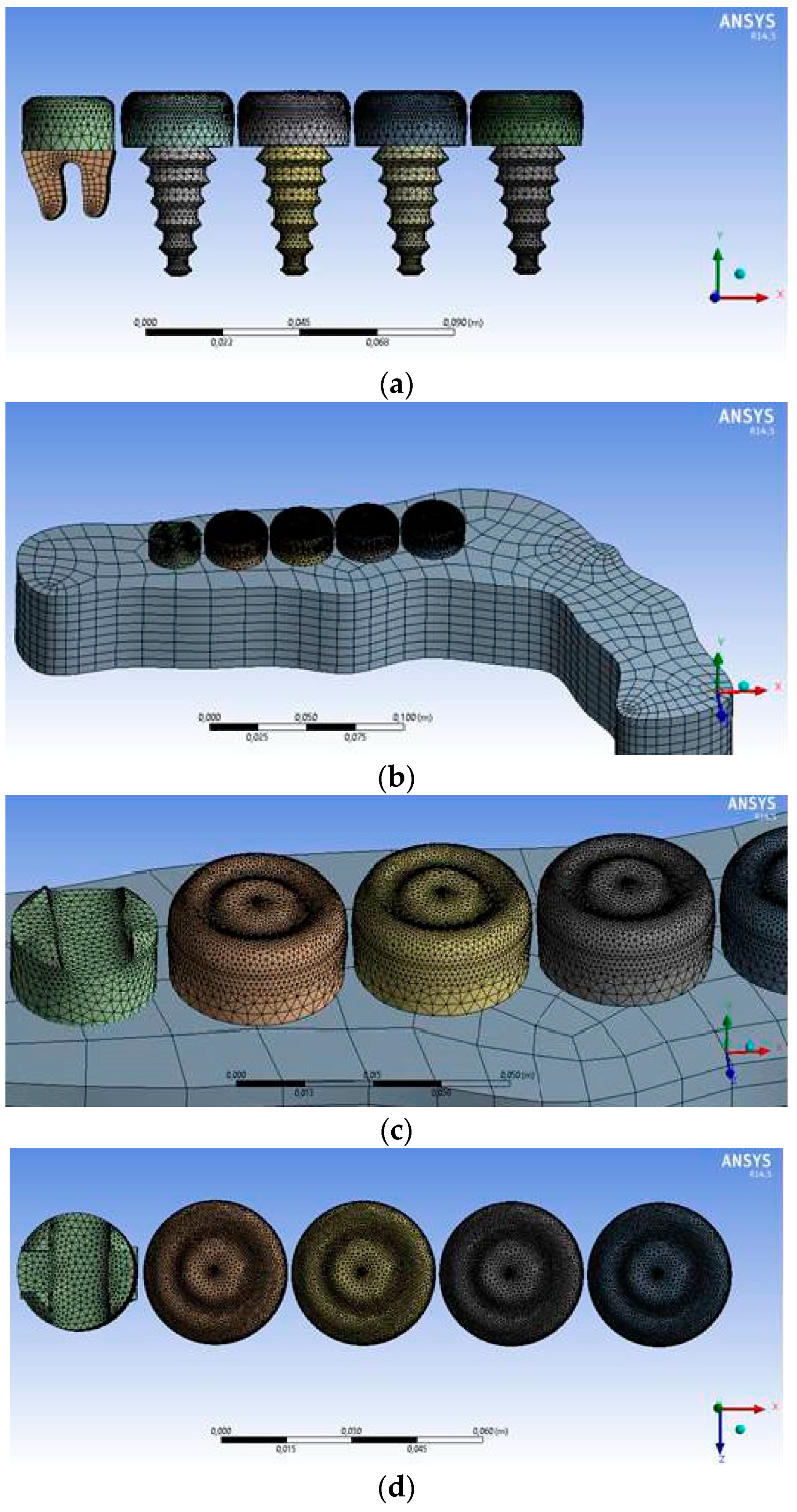

| Domain Name | Nodes | Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Jawbone | 3580 | 2745 |

| Fluid area | 83765 | 450800 |

| Natural tooth | 4017 | 15337 |

| Crown | 46692 | 240448 |

| Implant 1, Implant 2 | 3948 | 18216 |

| Implant 3, Implant 4 | 3948 | 18216 |

| All areas | 145950 | 745762 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).