Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Femur Fracture Model

2.2. X-Ray Analysis

2.3. Quantitative Analysis of Microcomputed Tomography (CT) Imaging of Bone Callus

2.4. Study Design and ACC Supplementation

2.5. Weight-Bearing Test

2.6. Micro-CT Quantification for Callus Repair

2.7. Histopathological Examination of the Femurs

2.8. Serum Protein Analysis

2.9. Mechanical Testing

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Surgery Results

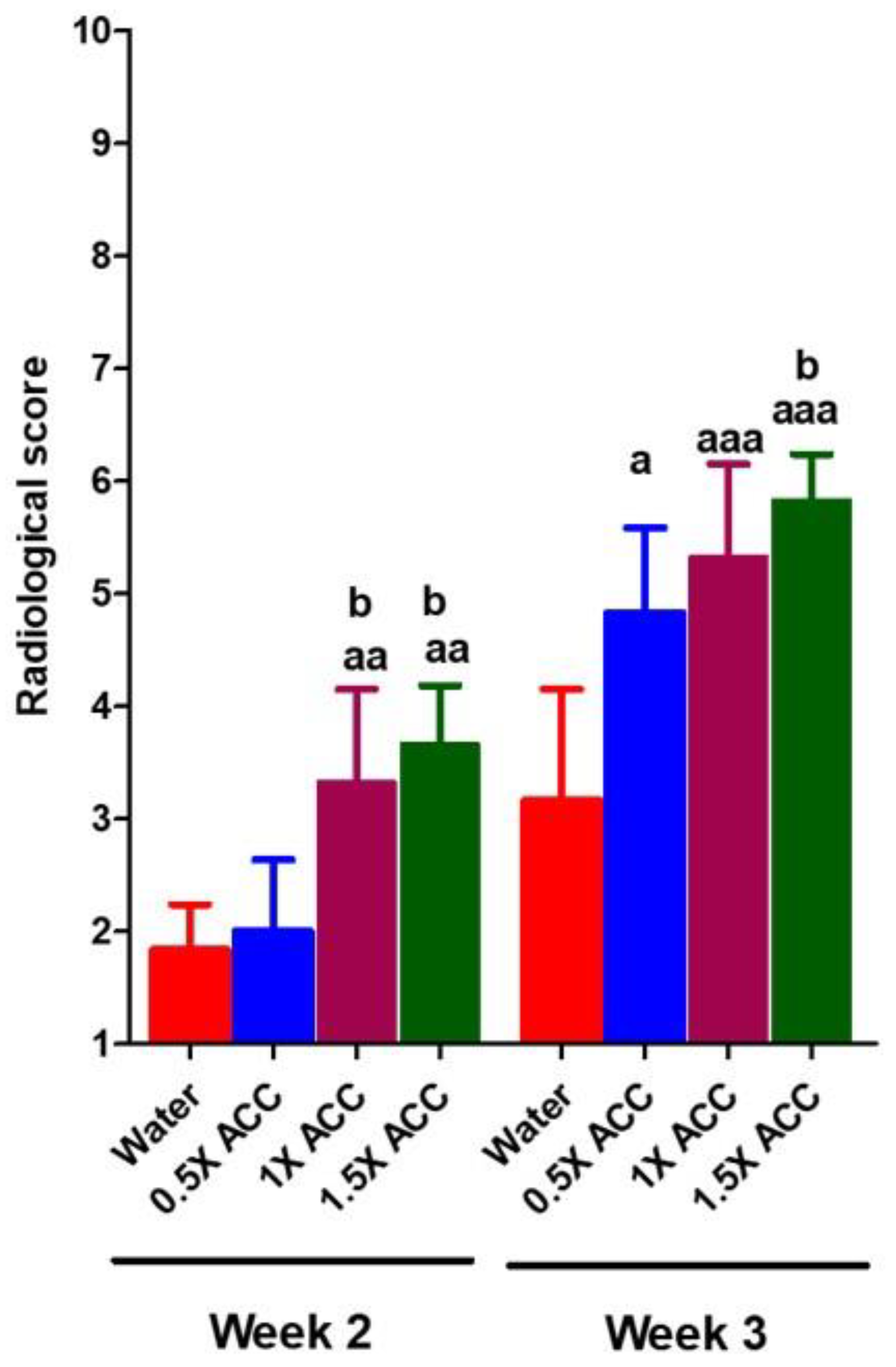

3.2. Radiological and Histomorphometry Results

3.3. Weight-Bearing Results

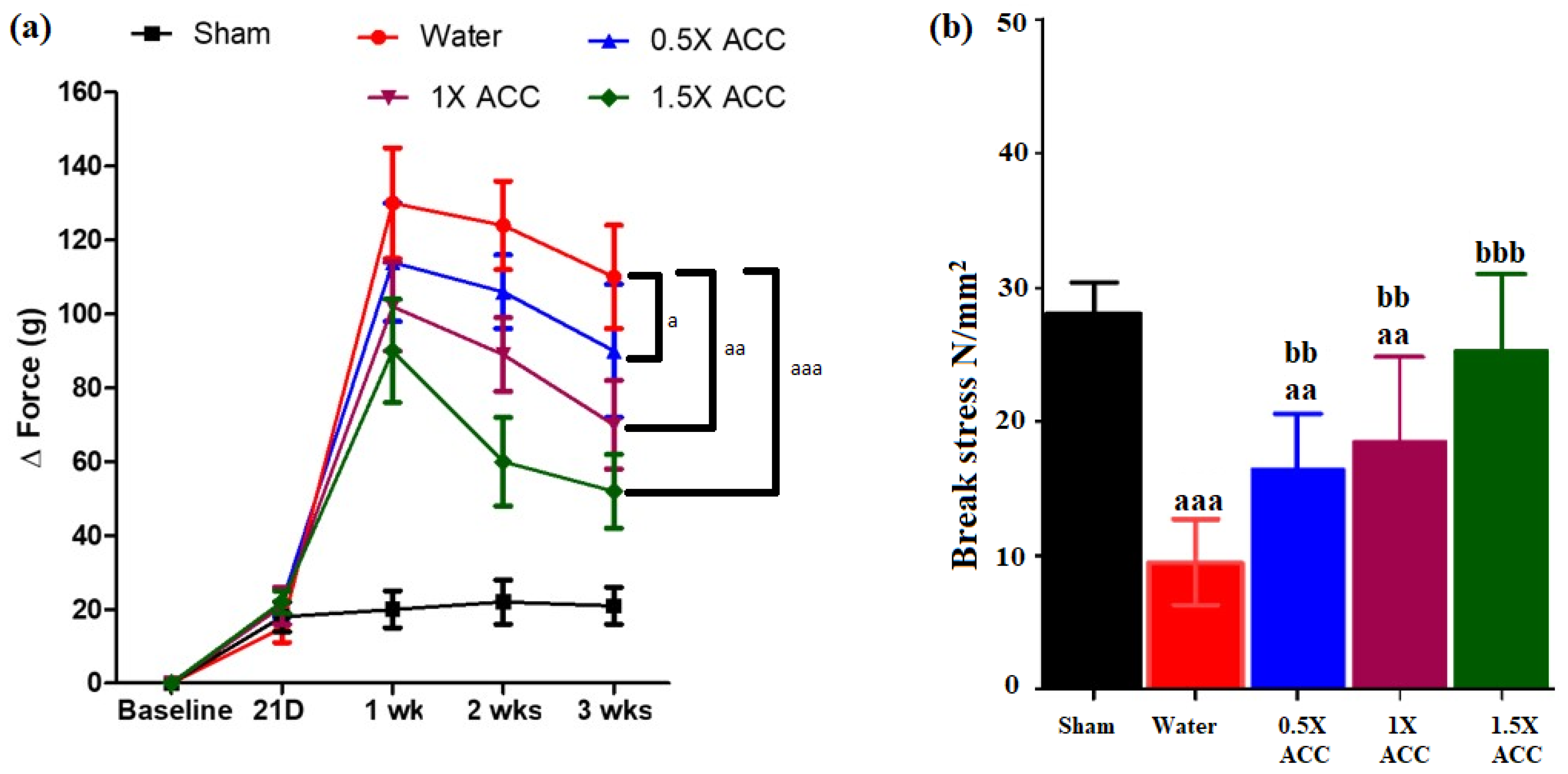

3.4. Mechanical Testing

3.5. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

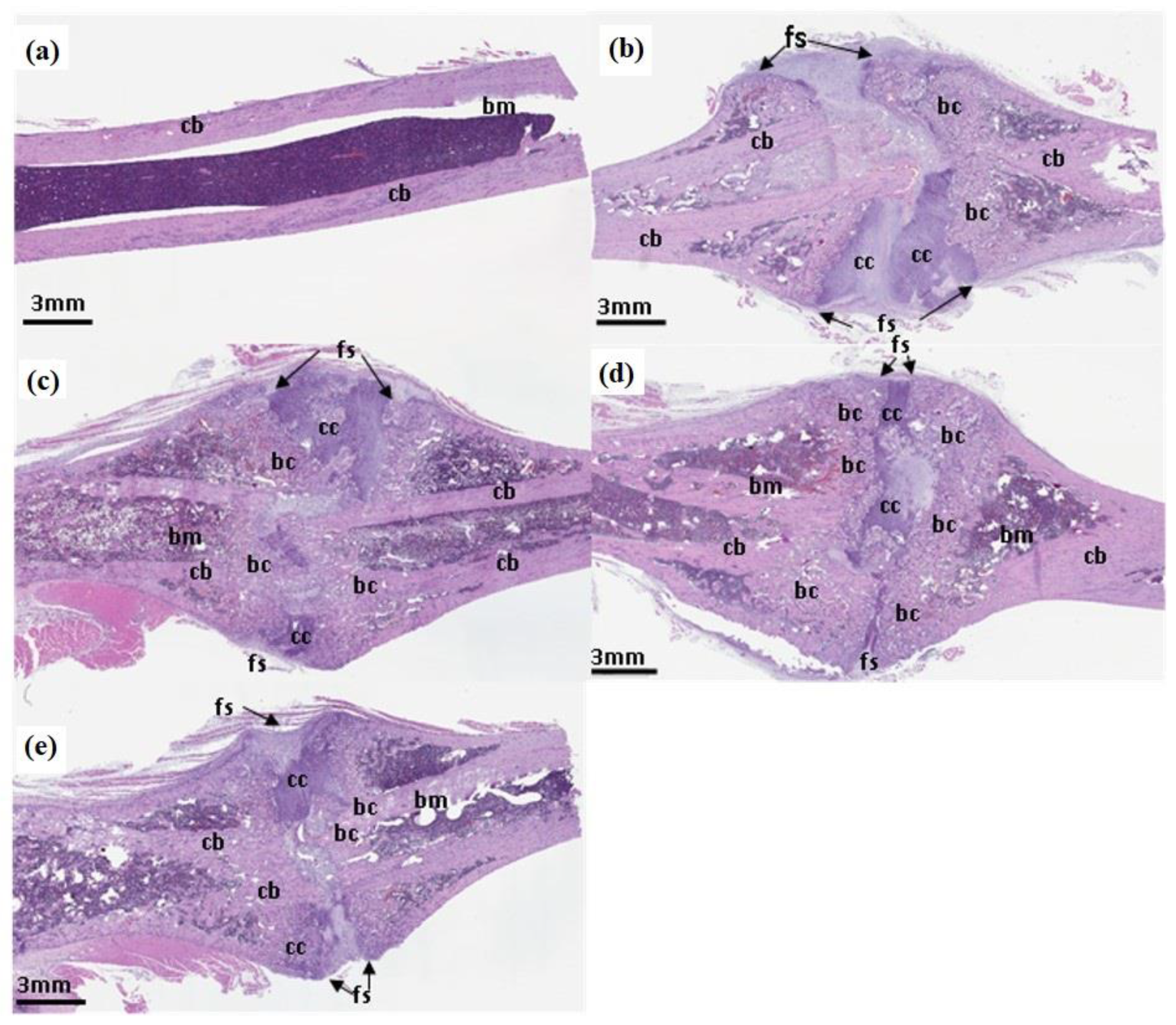

3.6. Biochemical Analyses

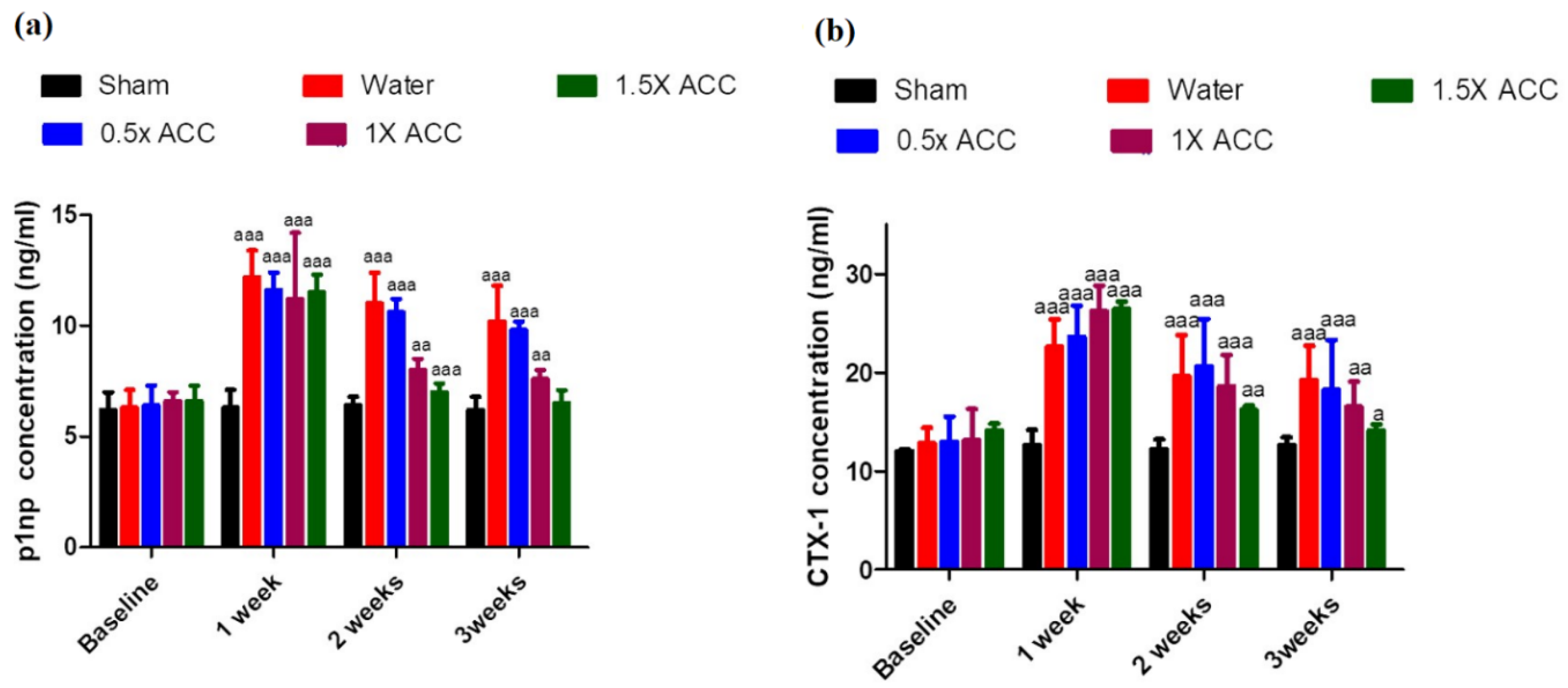

3.6.1. P1NP

3.6.2. CTX-1

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability

Conflicts of interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Amin: S.; Achenbach, S.J.; Atkinson, E.J.; Khosla, S.; Melton, L.J., 3rd. Trends in fracture incidence: a population-based study over 20 years. J Bone Miner Res 2014, 29, 581-589. [CrossRef]

- McPherson, E.J.; Stavrakis, A.I.; Chowdhry, M.; Curtin, N.L.; Dipane, M.V.; Crawford, B.M. Biphasic bone graft substitute in revision total hip arthroplasty with significant acetabular bone defects : a retrospective analysis. Bone Jt Open 2022, 3, 991-997. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.T.; Rosenbaum, A.J. Bone grafts, bone substitutes and orthobiologics: the bridge between basic science and clinical advancements in fracture healing. Organogenesis 2012, 8, 114-124. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.L.; Drissi, H. Advances and Promises of Nutritional Influences on Natural Bone Repair. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2020, 38, 695-707. [CrossRef]

- Shuid, A.N.; Mohamad, S.; Mohamed, N.; Fadzilah, F.M.; Mokhtar, S.A.; Abdullah, S.; Othman, F.; Suhaimi, F.; Muhammad, N.; Soelaiman, I.N. Effects of calcium supplements on fracture healing in a rat osteoporotic model. J Orthop Res 2010, 28, 1651-1656. [CrossRef]

- Somlyo, A.P.; Himpens, B. Cell calcium and its regulation in smooth muscle. Faseb j 1989, 3, 2266-2276. [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.-P.; Huang, J.-D.; Hsiao, H.-A.; Chang, Y.-W.; Kao, Y.-T. Risk Assessment of the Dietary Phosphate Exposure in Taiwan Population Using a Total Diet Study. Foods 2020, 9, 1574.

- Iguacel, I.; Miguel-Berges, M.L.; Gómez-Bruton, A.; Moreno, L.A.; Julián, C. Veganism, vegetarianism, bone mineral density, and fracture risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition reviews 2019, 77, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, R.; Naldini, G.; Chiavarini, M. Dietary Patterns in Relation to Low Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.) 2019, 10, 219-236. [CrossRef]

- Lagarto, A.; Bellma, A.; Couret, M.; Gabilondo, T.; López, R.; Bueno, V.; Guerra, I.; Rodríguez, J. Prenatal effects of natural calcium supplement on Wistar rats during organogenesis period of pregnancy. Experimental and toxicologic pathology : official journal of the Gesellschaft fur Toxikologische Pathologie 2013, 65, 49-53. [CrossRef]

- Pop, M.S.; Cheregi, D.C.; Onose, G.; Munteanu, C.; Popescu, C.; Rotariu, M.; Turnea, M.A.; Dogaru, G.; Ionescu, E.V.; Oprea, D., et al. Exploring the Potential Benefits of Natural Calcium-Rich Mineral Waters for Health and Wellness: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Balk, E.M.; Adam, G.P.; Langberg, V.N.; Earley, A.; Clark, P.; Ebeling, P.R.; Mithal, A.; Rizzoli, R.; Zerbini, C.A.F.; Pierroz, D.D., et al. Global dietary calcium intake among adults: a systematic review. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 2017, 28, 3315-3324. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Shi, P.; Lim, S.; Andrews, K.G.; Engell, R.E.; Ezzati, M.; Mozaffarian, D. Global, Regional, and National Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, Fruit Juices, and Milk: A Systematic Assessment of Beverage Intake in 187 Countries. PloS one 2015, 10, e0124845. [CrossRef]

- Shkembi, B.; Huppertz, T. Calcium Absorption from Food Products: Food Matrix Effects. Nutrients 2022, 14, 180.

- Mizuhira, V.; Ueno, M. Calcium Transport Mechanism in Molting Crayfish Revealed by Microanalysis (1)(2). J Histochem Cytochem 1983, 31, 214-218. [CrossRef]

- Wenger, K.H.; Zumbrun, S.D.; Rosas, M.; Dickinson, D.P.; McPherson, J.C., 3rd. Ingestion of gastrolith mineralized matrix increases bone volume and tissue volume in mouse long bone fracture model. J Orthop 2020, 20, 251-256. [CrossRef]

- Shechter, A.; Glazer, L.; Cheled, S.; Mor, E.; Weil, S.; Berman, A.; Bentov, S.; Aflalo, E.D.; Khalaila, I.; Sagi, A. A gastrolith protein serving a dual role in the formation of an amorphous mineral containing extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 7129-7134. [CrossRef]

- Bentov, S.; Weil, S.; Glazer, L.; Sagi, A.; Berman, A. Stabilization of amorphous calcium carbonate by phosphate rich organic matrix proteins and by single phosphoamino acids. J Struct Biol 2010, 171, 207-215. [CrossRef]

- Vaisman, N.; Shaltiel, G.; Daniely, M.; Meiron, O.E.; Shechter, A.; Abrams, S.A.; Niv, E.; Shapira, Y.; Sagi, A. Increased calcium absorption from synthetic stable amorphous calcium carbonate: double-blind randomized crossover clinical trial in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2014, 29, 2203-2209. [CrossRef]

- Meiron, O.E.; Bar-David, E.; Aflalo, E.D.; Shechter, A.; Stepensky, D.; Berman, A.; Sagi, A. Solubility and bioavailability of stabilized amorphous calcium carbonate. J Bone Miner Res 2011, 26, 364-372. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M.; Beig, A.; Carr, R.A.; Spence, J.K.; Dahan, A. A win-win solution in oral delivery of lipophilic drugs: supersaturation via amorphous solid dispersions increases apparent solubility without sacrifice of intestinal membrane permeability. Mol Pharm 2012, 9, 2009-2016. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Katie T.; Koewler, Nathan J.; Jimenez-Andrade, Juan M.; Buus, Ryan J.; Herrera, Monica B.; Martin, Carl D.; Ghilardi, Joseph R.; Kuskowski, Michael A.; Mantyh, Patrick W. A Fracture Pain Model in the Rat: Adaptation of a Closed Femur Fracture Model to Study Skeletal Pain. Anesthesiology 2008, 108, 473-483. [CrossRef]

- Manigrasso, M.B.; O’Connor, J.P. Characterization of a closed femur fracture model in mice. J Orthop Trauma 2004, 18, 687-695. [CrossRef]

- Sevcik, M.A.; Ghilardi, J.R.; Peters, C.M.; Lindsay, T.H.; Halvorson, K.G.; Jonas, B.M.; Kubota, K.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Boustany, L.; Shelton, D.L., et al. Anti-NGF therapy profoundly reduces bone cancer pain and the accompanying increase in markers of peripheral and central sensitization. Pain 2005, 115, 128-141. [CrossRef]

- Bonnarens, F.; Einhorn, T.A. Production of a standard closed fracture in laboratory animal bone. J Orthop Res 1984, 2, 97-101. [CrossRef]

- Fernihough, J.; Gentry, C.; Malcangio, M.; Fox, A.; Rediske, J.; Pellas, T.; Kidd, B.; Bevan, S.; Winter, J. Pain related behaviour in two models of osteoarthritis in the rat knee. Pain 2004, 112, 83-93. [CrossRef]

- Bove, S.E.; Calcaterra, S.L.; Brooker, R.M.; Huber, C.M.; Guzman, R.E.; Juneau, P.L.; Schrier, D.J.; Kilgore, K.S. Weight bearing as a measure of disease progression and efficacy of anti-inflammatory compounds in a model of monosodium iodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003, 11, 821-830. [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, M.; Mignemi, N.A.; Nyman, J.S.; Duvall, C.L.; Schwartz, H.S.; Okawa, A.; Yoshii, T.; Bhattacharjee, G.; Zhao, C.; Bible, J.E., et al. Fibrinolysis is essential for fracture repair and prevention of heterotopic ossification. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 3117-3131. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-C.; Yang, C.-C.; Tai, C.-L.; Tsai, T.-T.; Lai, P.-L.; Fu, T.-S.; Niu, C.-C.; Chen, L.-H.; Chen, W.-J. Characterization of a novel caudal vertebral interbody fusion in a rat tail model: An implication for future material and mechanical testing. Biomedical Journal 2017, 40, 62-68. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Campion, G.; Melton, L.J., 3rd. Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 1992, 2, 285-289. [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.B.; He, S.L.; Xu, L.; Liu, A.M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, O.; Xing, X.P.; Sun, Y.; Cummings, S.R. Rapidly increasing rates of hip fracture in Beijing, China. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2012, 27, 125-129. [CrossRef]

- Shlisky, J.; Mandlik, R.; Askari, S.; Abrams, S.; Belizan, J.M.; Bourassa, M.W.; Cormick, G.; Driller-Colangelo, A.; Gomes, F.; Khadilkar, A., et al. Calcium deficiency worldwide: prevalence of inadequate intakes and associated health outcomes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2022, 1512, 10-28. [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Calcium in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Journal of internal medicine 1992, 231, 169-180. [CrossRef]

- Hoang-Kim, A.; Gelsomini, L.; Luciani, D.; Moroni, A.; Giannini, S. Fracture healing and drug therapies in osteoporosis. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2009, 6, 136-143.

- Hoffman, J.R.; Ben-Zeev, T.; Zamir, A.; Levi, C.; Ostfeld, I. Examination of Amorphous Calcium Carbonate on the Inflammatory and Muscle Damage Response in Experienced Resistance Trained Individuals. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Marsell, R.; Einhorn, T.A. The biology of fracture healing. Injury 2011, 42, 551-555. [CrossRef]

- Dincel, Y.M.; Alagoz, E.; Arikan, Y.; Caglar, A.K.; Dogru, S.C.; Ortes, F.; Arslan, Y.Z. Biomechanical, histological, and radiological effects of different phosphodiesterase inhibitors on femoral fracture healing in rats. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2018, 26, 2309499018777885. [CrossRef]

- Yasui, M.; Shiraishi, Y.; Ozaki, N.; Hayashi, K.; Hori, K.; Ichiyanagi, M.; Sugiura, Y. Nerve growth factor and associated nerve sprouting contribute to local mechanical hyperalgesia in a rat model of bone injury. Eur J Pain 2012, 16, 953-965. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Meyers, C.A.; Chang, L.; Lee, S.; Li, Z.; Tomlinson, R.; Hoke, A.; Clemens, T.L.; James, A.W. Fracture repair requires TrkA signaling by skeletal sensory nerves. J Clin Invest 2019, 129, 5137-5150. [CrossRef]

- Chartier, S.R.; Thompson, M.L.; Longo, G.; Fealk, M.N.; Majuta, L.A.; Mantyh, P.W. Exuberant sprouting of sensory and sympathetic nerve fibers in nonhealed bone fractures and the generation and maintenance of chronic skeletal pain. Pain 2014, 155, 2323-2336. [CrossRef]

- Brazill, J.M.; Beeve, A.T.; Craft, C.S.; Ivanusic, J.J.; Scheller, E.L. Nerves in Bone: Evolving Concepts in Pain and Anabolism. J Bone Miner Res 2019, 34, 1393-1406. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Diggins, N.H.; Gunderson, Z.J.; Fehrenbacher, J.C.; White, F.A.; Kacena, M.A. No pain, no gain? The effects of pain-promoting neuropeptides and neurotrophins on fracture healing. Bone 2020, 131, 115109. [CrossRef]

- Loi, F.; Córdova, L.A.; Pajarinen, J.; Lin, T.H.; Yao, Z.; Goodman, S.B. Inflammation, fracture and bone repair. Bone 2016, 86, 119-130. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, I.C.; Lindblad, A.J.; Kolber, M.R. Fracture healing and NSAIDs. Can Fam Physician 2014, 60, 817, e439-840.

- Shanmugam, V.K.; Couch, K.S.; McNish, S.; Amdur, R.L. Relationship between opioid treatment and rate of healing in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2017, 25, 120-130. [CrossRef]

- Majuta, L.A.; Longo, G.; Fealk, M.N.; McCaffrey, G.; Mantyh, P.W. Orthopedic surgery and bone fracture pain are both significantly attenuated by sustained blockade of nerve growth factor. Pain 2015, 156, 157-165. [CrossRef]

- Baht, G.S.; Vi, L.; Alman, B.A. The Role of the Immune Cells in Fracture Healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2018, 16, 138-145. [CrossRef]

- Proff, P.; Römer, P. The molecular mechanism behind bone remodelling: a review. Clin Oral Investig 2009, 13, 355-362. [CrossRef]

- Gerstenfeld, L.C.; Sacks, D.J.; Pelis, M.; Mason, Z.D.; Graves, D.T.; Barrero, M.; Ominsky, M.S.; Kostenuik, P.J.; Morgan, E.F.; Einhorn, T.A. Comparison of effects of the bisphosphonate alendronate versus the RANKL inhibitor denosumab on murine fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res 2009, 24, 196-208. [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, M.; Mori, Y.; Sugahara-Tobinai, A.; Takai, T.; Itoi, E. Impaired Fracture Healing Caused by Deficiency of the Immunoreceptor Adaptor Protein DAP12. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0128210. [CrossRef]

- Schindeler, A.; McDonald, M.M.; Bokko, P.; Little, D.G. Bone remodeling during fracture repair: The cellular picture. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2008, 19, 459-466. [CrossRef]

- Gerstenfeld, L.C.; Cullinane, D.M.; Barnes, G.L.; Graves, D.T.; Einhorn, T.A. Fracture healing as a post-natal developmental process: molecular, spatial, and temporal aspects of its regulation. J Cell Biochem 2003, 88, 873-884. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.; Alpern, E.; Miclau, T.; Helms, J.A. Does adult fracture repair recapitulate embryonic skeletal formation? Mech Dev 1999, 87, 57-66. [CrossRef]

- Ivaska, K.K.; Gerdhem, P.; Akesson, K.; Garnero, P.; Obrant, K.J. Effect of fracture on bone turnover markers: a longitudinal study comparing marker levels before and after injury in 113 elderly women. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2007, 22, 1155-1164. [CrossRef]

- Veitch, S.W.; Findlay, S.C.; Hamer, A.J.; Blumsohn, A.; Eastell, R.; Ingle, B.M. Changes in bone mass and bone turnover following tibial shaft fracture. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 2006, 17, 364-372. [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, A.; Müller, U.; Roth, H.J.; Wentzensen, A.; Grützner, P.A.; Zimmermann, G. TRACP 5b and CTX as osteological markers of delayed fracture healing. Injury 2011, 42, 758-764. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.C.; O’Hara, N.N.; Bzovsky, S.; Bahney, C.S.; Sprague, S.; Slobogean, G.P. Bone turnover markers as surrogates of fracture healing after intramedullary fixation of tibia and femur fractures. Bone & joint research 2022, 11, 239-250. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.K.; Laroche, N.; Vanden-Bossche, A.; Linossier, M.T.; Thomas, M.; Peyroche, S.; Normand, M.; Bertache-Djenadi, Y.; Thomas, T.; Marotte, H., et al. Protective Effect on Bone of Nacre Supplementation in Ovariectomized Rats. JBMR plus 2022, 6, e10655. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Zhou, Q.; Bai, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, G.; Zong, S. Deficiency of PDK1 in osteoclasts delays fracture healing and repair. Molecular medicine reports 2020, 22, 1536-1546. [CrossRef]

- Ecker Cohen, O.; Neuman, S.; Natan, Y.; Levy, A.; Blum, Y.D.; Amselem, S.; Bavli, D.; Ben, Y. Amorphous calcium carbonate enhances osteogenic differentiation and myotube formation of human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells and primary skeletal muscle cells under microgravity conditions. Life sciences in space research 2024, 41, 146-157. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, W.; Masson, A.; Li, Y.-P. Cell signaling and transcriptional regulation of osteoblast lineage commitment, differentiation, bone formation, and homeostasis. Cell Discovery 2024, 10, 71. [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.S.; Song, Y.M.; Cho, T.H.; Park, Y.D.; Lee, K.B.; Noh, I.; Weber, F.; Hwang, S.J. In vitro response of primary human bone marrow stromal cells to recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 in the early and late stages of osteoblast differentiation. DGD 2008, 50, 553-564. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, O.E.; Neuman, S.; Natan, Y.; Levy, A.; Blum, Y.D.; Amselem, S.; Bavli, D.; Ben, Y. Amorphous calcium carbonate enhances osteogenic differentiation and myotube formation of human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells and primary skeletal muscle cells under microgravity conditions. Life Sciences in Space Research 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Tao, Y.; Bai, J.; Yu, B.; Shen, J.; Sun, H.; Xiao, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J., et al. KLF2 regulates osteoblast differentiation by targeting of Runx2. Laboratory Investigation 2019, 99, 271-280. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Kim, S.H.; Cui, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, W.; Kong, Y., et al. Wnt signaling in bone formation and its therapeutic potential for bone diseases. Therapeutic advances in musculoskeletal disease 2013, 5, 13-31. [CrossRef]

- Schini, M.; Vilaca, T.; Gossiel, F.; Salam, S.; Eastell, R. Bone Turnover Markers: Basic Biology to Clinical Applications. Endocrine reviews 2023, 44, 417-473. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-K.; Lee, Y.-S.; Kong, Z.-L.; Chien, Y.-W. Amorphous Calcium Carbonate from Plants Can Promote Bone Growth in Growing Rats. Biology 2024, 13, 201.

- Sullivan, S.D.; Lehman, A.; Nathan, N.K.; Thomson, C.A.; Howard, B.V. Age of menopause and fracture risk in postmenopausal women randomized to calcium + vitamin D, hormone therapy, or the combination: results from the Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trials. Menopause 2017, 24, 371-378. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).