Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

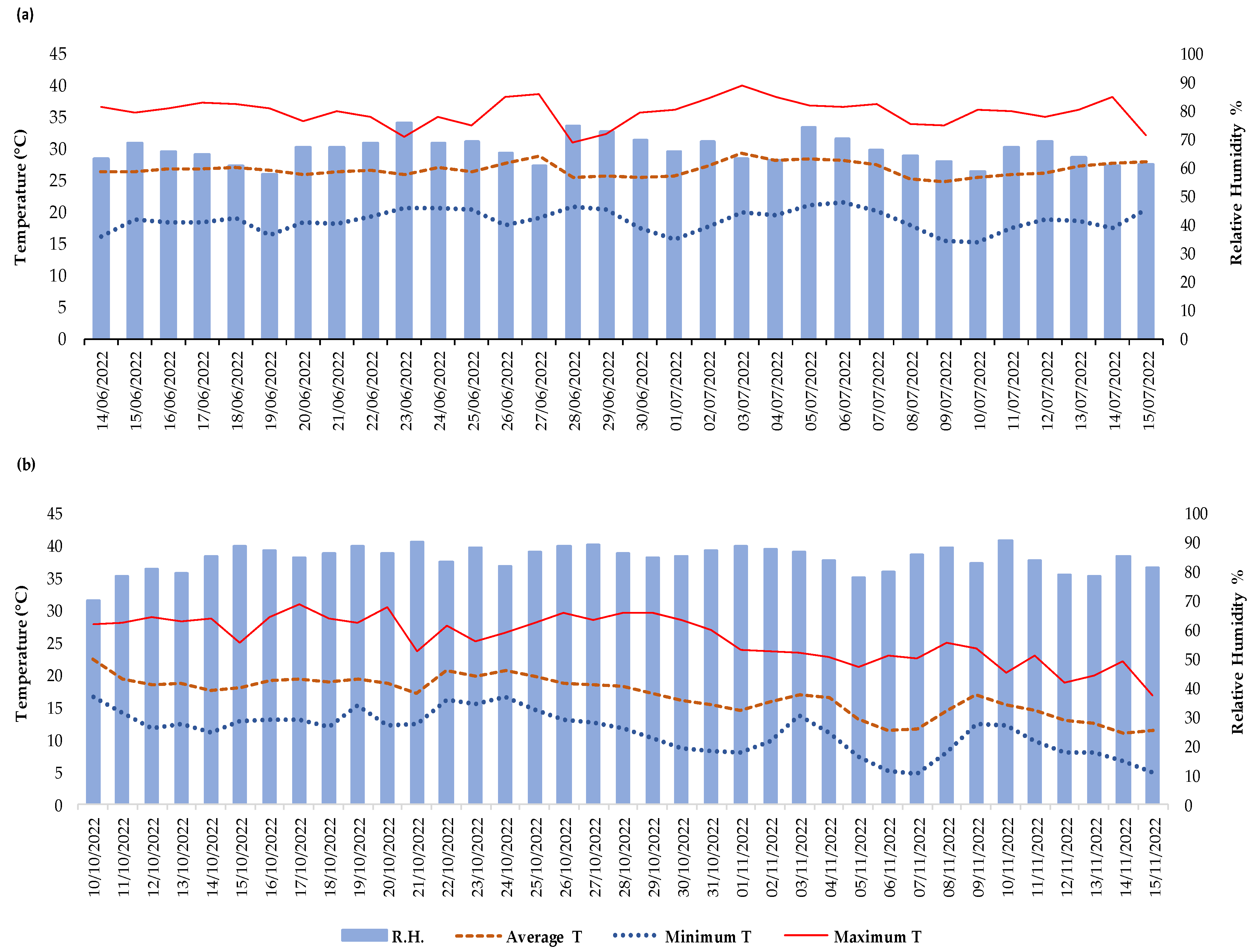

2.1. Experimental Site and Trials Description

2.2. Crop Measurements

2.3. Nutrient Use Efficiency

- (a)

- PFP = Yf/NA (g g-1)

- (b)

- NUEa = (Yf-Yc)/NA (g g−1)

- (c)

- NUEp = (Yf-Yc)/(TNf-TNc) (g g−1)

- (d)

- REC = TNf-TNc/NA (g g−1)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

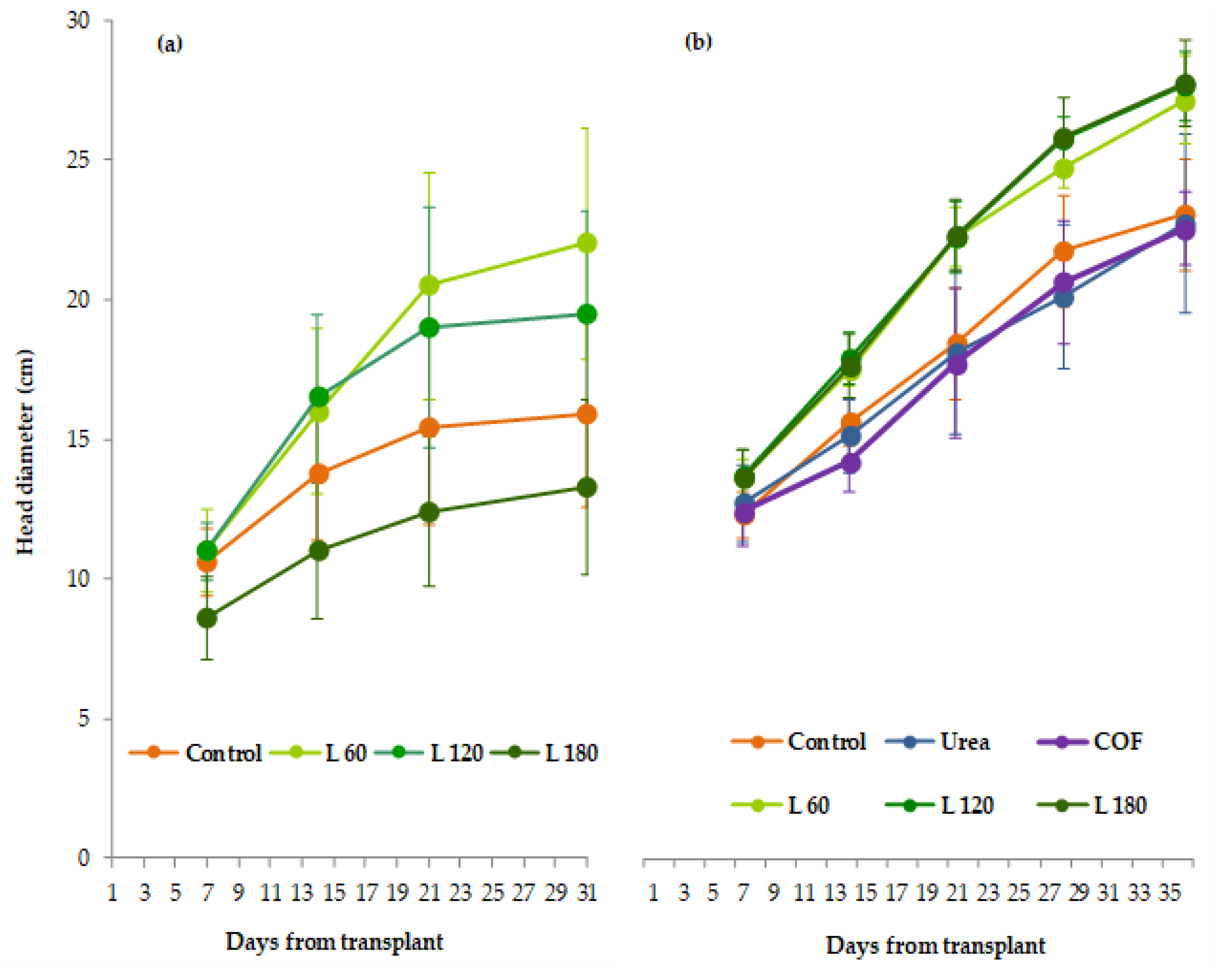

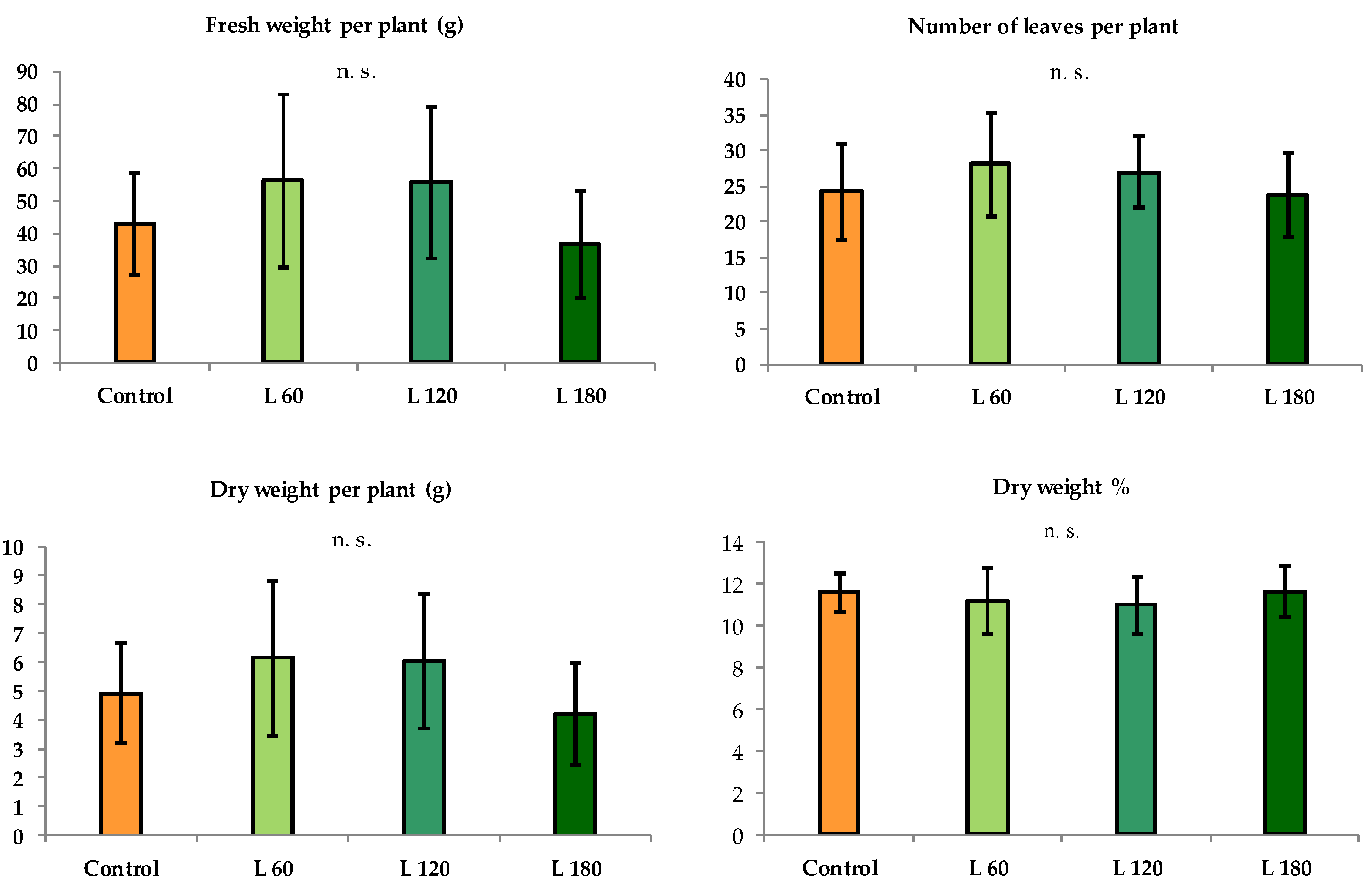

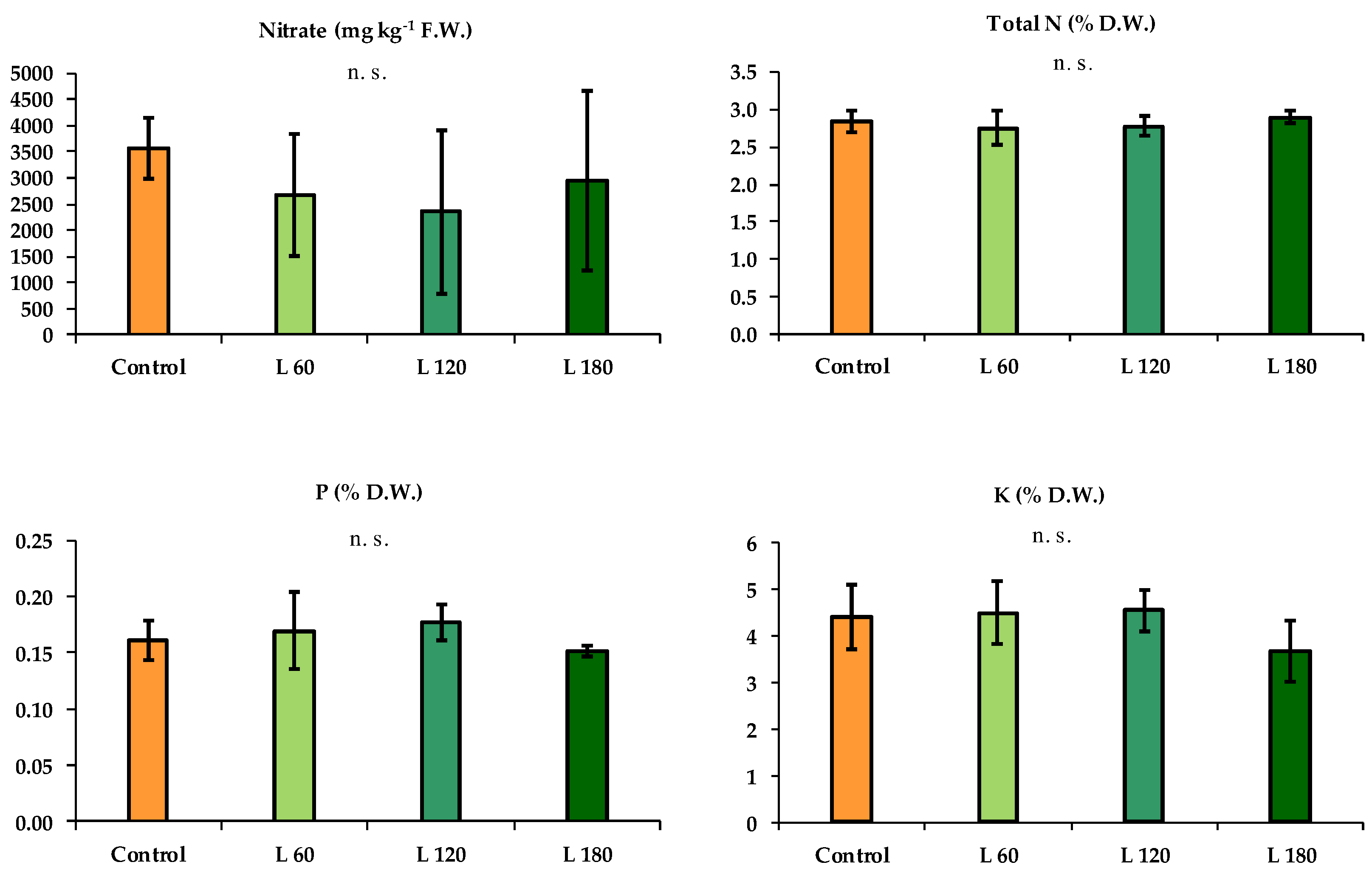

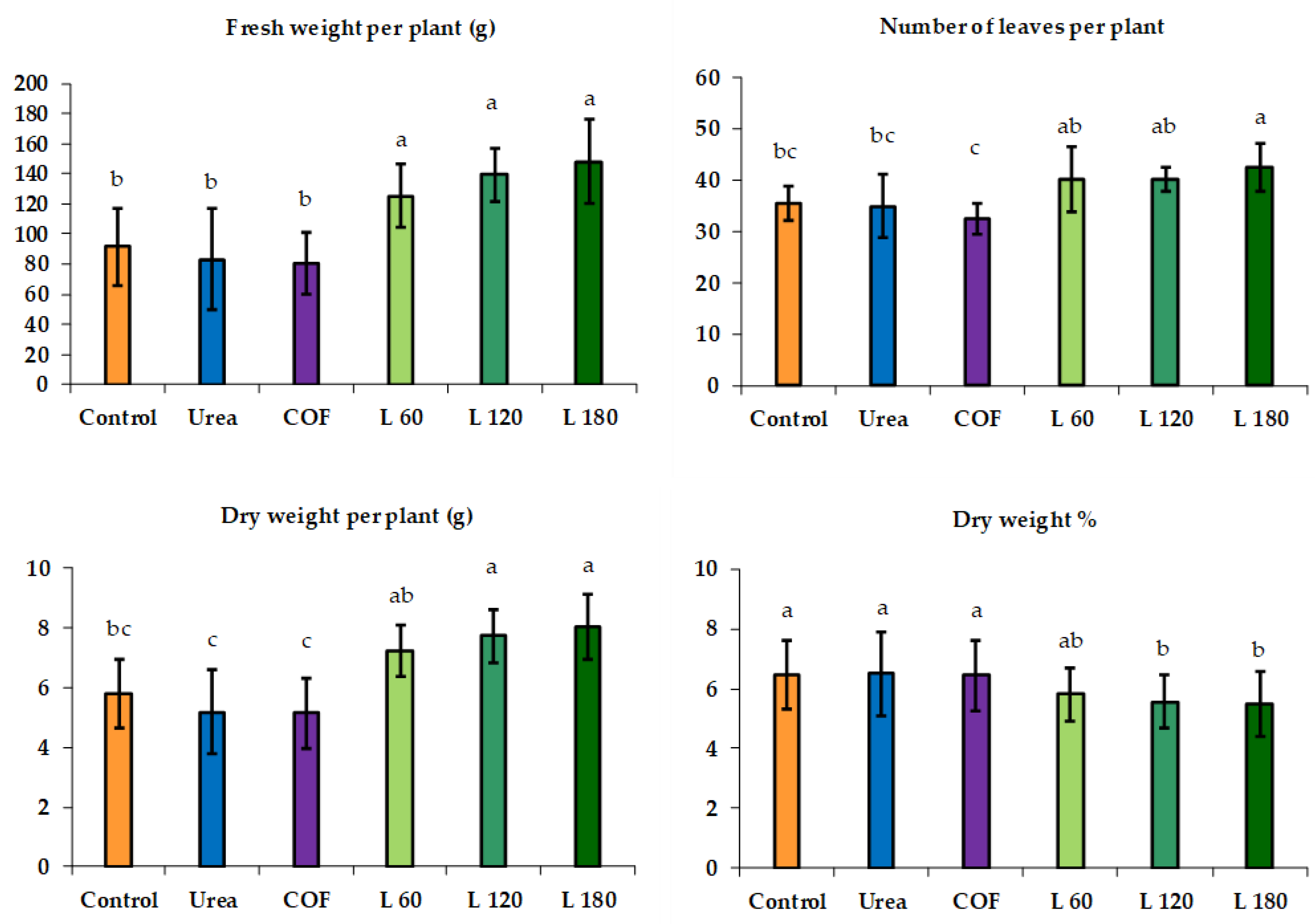

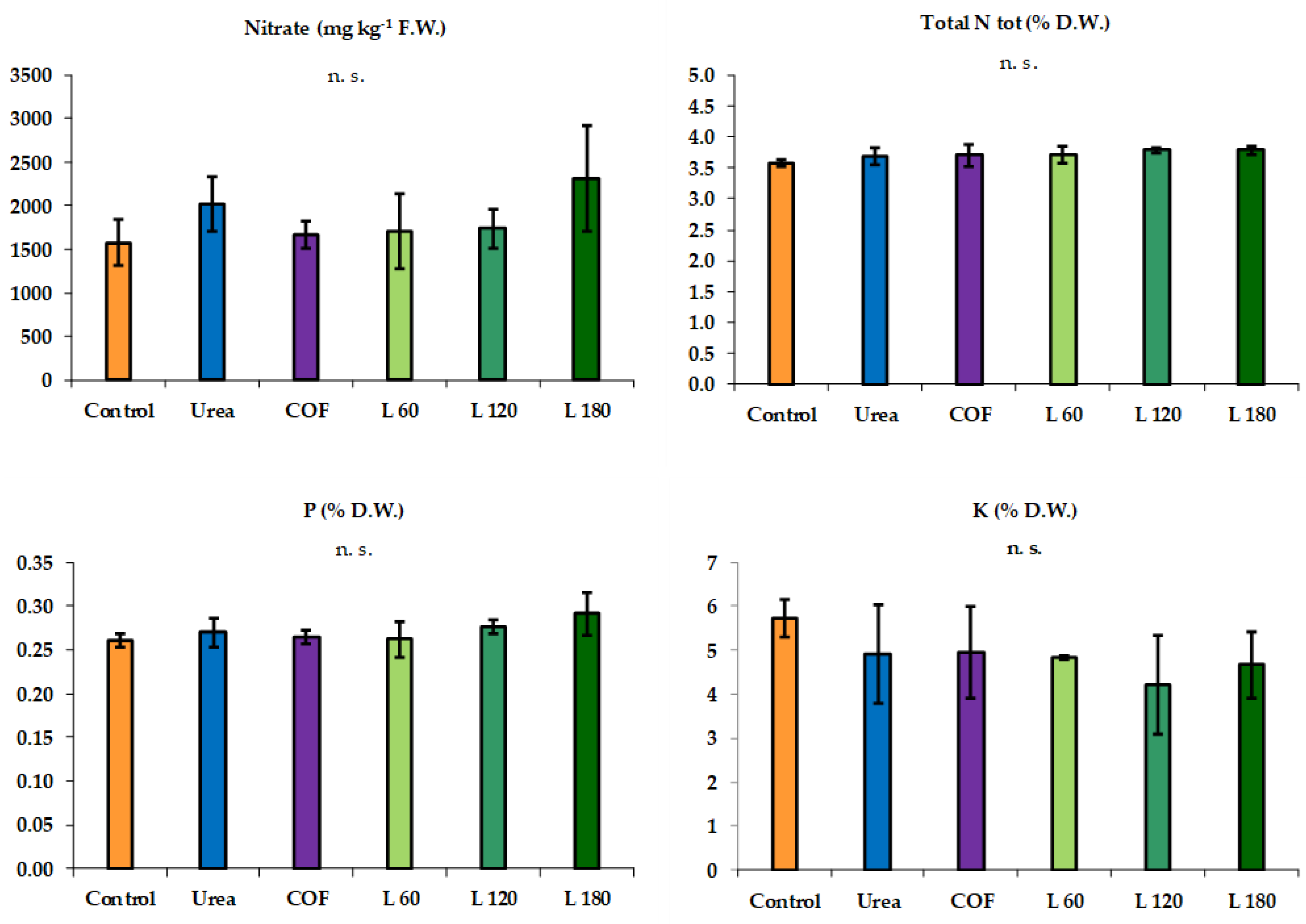

3.1. Summer Growing Cycle

3.2. Autumn Growing Cycle

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acosta, K.; Appenroth, K.J.; Borisjuk, L.; Edelman, M.; Heinig, U.; Jansen, M.A.; Oyama, T.; Pasaribu, B.; Schubert, I.; Sorrels, S.; Sree, K.S.; Xu, S.; Michael, T.P.; Lam, E. Return of the Lemnaceae: duckweed as a model plant system in the genomics and postgenomics era. Plant Cell 2021, 33(10), 3207-3234. [CrossRef]

- Les, D.H.; Crawford, D.J.; Landolt, E.; Gabel, J.D.; Kimball, R.T. Phylogeny and systematics of Lemnaceae, the duckweed family. Syst. Bot. 2002, 27(2), 221-240.

- Ziegler, P.; Appenroth, K.J.; Sree, K.S. Survival strategies of duckweeds, the world’s smallest Angiosperms. Plants 2023, 12(11), 2215. [CrossRef]

- Sil, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Neela, F.A. Anatomical features and antimicrobial activity of duckweed. Bang. J. Bot. 2023, 52(1), 105-110. [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Elizalde, C.; Lynn, J.; Ernst, E.; Martienssen, R. Duckweeds. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33(3), R89-R91.

- Landesman, L.; Parker, N.C.; Fedler, C.B.; Konikoff, M. Modeling duckweed growth in wastewater treatment systems. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2005, 17, 1-8.

- Andrade-Pereira, D.; Cuddington, K. Range expansion risk for a newly established invasive duckweed species in Europe and Canada. Plant Ecol. 2024, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Gul, B.; Rabial, S.; Khan, H. Efficacy of herbicides for control of duckweed (Lemna minor L.). Sarhad J. Agric. 2021, 37(4), 1194-1200. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Hu, S.; Li, T.; He, F.; Tian, C.; Han, Y.; Mao, Y.; Jing, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y. A preliminary study of the impacts of duckweed coverage during rice growth on grain yield and quality. Plants 2023, 13(1), 57. [CrossRef]

- Janse, J.H.; Van Puijenbroek, P.J.T.M. Effects of eutrophication in drainage ditches. Environ. Pollut. 1998, 102 (Suppl. S1), 547–552. [CrossRef]

- Feller, J.; Taylor, M.; Lunt, P.H. Predicting Lemna growth based on climate change and eutrophication in temperate freshwater drainage ditches. Hydrobiologia 2024, 851(10), 2529-2541. [CrossRef]

- Vu, G.T.H.; Fourounjian, P.; Wang, W.; Cao, X.H. Future Prospects of Duckweed Research and Applications. In The Duckweed Genomes; Cao, X.H., Fourounjian, P., Wang, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 179–185.

- Ekperusi, A.O.; Sikoki, F.D.; Nwachukwu, E.O. Application of common duckweed (Lemna minor) in phytoremediation of chemicals in the environment: State and future perspective. Chemosphere 2019, 223, 285-309. [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Cheng, J.J. Growing duckweed for biofuel production: a review. Plant Biol. 2015, 17, 16-23. [CrossRef]

- Baek, G.; Saeed, M.; Choi, H.K. Duckweeds: their utilization, metabolites and cultivation. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2021, 64, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Sońta, M.; Rekiel, A.; Batorska, M. Use of duckweed (Lemna L.) in sustainable livestock production and aquaculture – A review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2019, 19(2), 257-271. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.: Shen, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Smith, G.; Sun, X.S.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y. Duckweed (Lemnaceae) for potentially nutritious human food: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39(7), 3620–3634. [CrossRef]

- Mahofa, R.; Kapenzi, R.; Masaka, J. The effects of different types of duckweed manure on height and yield of floridade tomatoes. Midlands States Univ. J. Sci. Agric. Technol. 2014, 5 (1): 135-152.

- Chikuvire, T.J.; Muchaonyerwa, P.; Zengeni, R. Improvement of nitrogen uptake and dry matter content of Swiss chard by pre-incubation of duckweeds in soil. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agricul. 2019, 8 (1), 235–244. [CrossRef]

- Jilimane K. Nitrogen and phosphorus release in soil and fertiliser value of Lemna minor biomass relative to chicken litter compost. Doctoral dissertation, School of agricultural, earth and environmental sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg, 2019.

- Kreider, A.N.; Fernandez Pulido, C.R.; Bruns, M.A.; Brennan, R.A. Duckweed as an agricultural amendment: nitrogen mineralization, leaching, and sorghum uptake. J. Environm. Quality 2019, 48(2), 469-475. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lens, P.N.L.; Otero-Gonzales, L.; Du Laing, G. Production of selenium and zinc-enriched Lemna and Azolla as potential micronutrient-enriched bioproducts. Water Res. 2020, 172 (115522): 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Pulido, C.R.; Caballero, J.; Bruns, M.A.; Brennan, R.A. Recovery of waste nutrients by duckweed for reuse in sustainable agriculture: second-year results of a field pilot study with sorghum. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 168: 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Otero-Gonzales, L.; Parao, A.; Tack, P.; Folens, K.; Ferrer, I.; Lens, P.N.L.; Du Laing. G. Valorization of selenium-enriched sludge and duckweed generated from wastewater as micronutrient biofertilizer. Chemosphere 2021, 281 (130767): 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Mikula, K.; Skrzypczak, D.; Izydorczyk, G.; Gorazda, K.; Kulczycka, J.; Kominko, H.; Moustakas, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A. Practical aspects of biowastes conversion to fertilizers. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Rauf, M.; Saeed, N.A. Excessive use of nitrogenous fertilizers: an unawareness causing serious threats to environment and human health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 26983–26987. [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Moustakas, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A. Bio-Based Fertilizers: A Practical Approach towards Circular Economy. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 295, 122223. [CrossRef]

- Elia, A.; Conversa, G. Agronomic and physiological responses of a tomato crop to nitrogen input. Eur. J. Agron. 2012, 40, 64-74. [CrossRef]

- Di Gioia, F.; Gonnella, M.; Buono, V.; Ayala, O.; Santamaria, P. Agronomic, physiological and quality response of romaine and red oak-leaf lettuce to nitrogen input. Ital. J. Agron. 2017, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Report (2022). Available on line: https://climate.copernicus.eu/esotc/2022/temperature (Accessed on October 2024).

- Moyo, C.C.; Kissel, D.E.; Cabrera, M.L. Temperature effects on soil urease activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1989, 21(7), 935-938. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.E.; Myrold, D.D.; Bottomley, P.J. Temperature affects the kinetics of nitrite oxidation and nitrification coupling in four agricultural soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 019, 136, 107523. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Pulido, C.R.; Femeena, P.V.; Brennan, R.A. Nutrient cycling with duckweed for the fertilization of root, fruit, leaf, and grain crops: Impacts on plant–soil–leachate systems. Agriculture 2024, 14, 188. [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, A.; Aji, O.R.; Sumbudi, M. Growth response and biochemistry of red spinach (Amaranthus tricolor L.) with the application of liquid organic fertilizer Lemna sp. J. Biotechnol. Nat. Sci. 2022, 2(2), 61-69. [CrossRef]

- Tesi, R. Orticoltura Mediterranea Sostenibile; Pàtron Editore: Bologna, Italy, 2010.

- Nicolas-Espinosa, J.; Garcia-Ibañez, P.; Lopez-Zaplana, A.; Yepes-Molina, L.; Albaladejo-Marico, L.; Carvajal, M. Confronting secondary metabolites with water uptake and transport in plants under abiotic stress. Int. J. Molec. Sci 2023, 24(3), 2826. [CrossRef]

- Hounsome, N.; Hounsome, B.; Tomos, D.; Edwards-Jones, G. Plant Metabolites and Nutritional Quality of Vegetables. J. Food. Sci. 2008, 73, R48–R65. [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Kim, H.J.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Rouphael, Y. Nitrate in fruits and vegetables. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 237, 221-238. [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, P. Nitrate in vegetables: toxicity, content, intake and EC regulation. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2006, 86(1), 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Kreider, A.N. Behavior of duckweed as an agricultural amendment: Nitrogen mineralization, leaching, and sorghum uptake. Thesis in Environmental Engineering, Master of Science, Pennsylvania State University, 2015.

- Fernandez Pulido, C.R. Duckweed as a sustainable soil amendment to supportcrop growth, enhance soil quality, and reduce agricultural runoff. Thesis in Environmental Engineering, Master of Science, Pennsylvania State University, 2016.

- Ahmad, Z.; Hossain, N.S.; Hussain, S.G.; Khan, A.H. Effect of Duckweed (Lemna minor) as complement to fertilizer nitrogen on the growth and yield of rice. Int. J. Trop. Agric. 1990, 8, 72-79.

- Anas, M.; Liao, F.; Verma, K.K.; Sarwar, M.A.; Mahmood, A.; Chen, Z.-L.; Li, Q.; Zeng, X.-P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.-R. Fate of Nitrogen in Agriculture and Environment: Agronomic, Eco-Physiological and Molecular Approaches to Improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Biol. Res. 2020, 53, 47. [CrossRef]

- Congreves, K.A.; Otchere, O.; Ferland, D.; Farzadfar, S.; Williams, S.; Arcand, M.M. Nitrogen use efficiency definitions of today and tomorrow. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Folina, A.; Tataridas, A.; Mavroeidis, A.; Kousta, A.; Katsenios, N.; Efthimiadou, A.; Travlos, I.S.; Roussis, I.; Darawsheh, M.K.; Papastylianou, P.; et al. Evaluation of various nitrogen indices in N-Fertilizers with inhibitors in field crops: A review. Agron. 2021, 11, 418. [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, H. Optimizing the Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Vegetable Crops. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 106–143. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.B.; Incrocci, L.; van Ruijven, J.; Massa, D. Reducing Contamination of Water Bodies from European Vegetable Production Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Davidson, E.; Mauzerall, D.; Searchinger, T.; Dumas, P.; Shen, Y. Managing Nitrogen for Sustainable Development. Nature 2015, 528, 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Hirel, B.; Lemaire, G. From agronomy and ecophysiology to molecular genetics for improving nitrogen use efficiency in crops. J. Crop. Improv. 2005, 15, 213–257. [CrossRef]

- Regni, L.; Del Buono, D.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Senizza, B.; Lucini, L.; Trevisan, M.; Morelli Venturi, D.; Costantino, F.; Proietti, P. Biostimulant Effects of an Aqueous Extract of Duckweed (Lemna minor L.) on Physiological and Biochemical Traits in the Olive Tree. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1299. [CrossRef]

- Dobermann, A. Nitrogen use efficiency—State of the art. In Proceedings of the IFA International Workshop on Enhanced Efficiency Fertilizers, Frankfurt, Germany, 28–30 June 2005; pp. 1–16.

- Greenwood, D.J.; Kubo, K.; Burn, S.I.G.; Draycott, A. Apparent recovery of fertilizer N by vegetable crops. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1989, 35, 367–381. [CrossRef]

- Tei, F.; Benincasa, P.; Guiducci, M. Nitrogen fertilisation on lettuce, processing tomato and sweet pepper: Yield, nitrogen uptake and the risk of nitrate leaching. Acta Hortic. 1999, 506, 61–67. [CrossRef]

- Tei, F.; Benincasa, P.; Guiducci, M. Effect of nitrogen availability on growth and nitrogen uptake in lettuce. Acta Hortic. 2000, 533, 385–392. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7,9 | |

| Electrical Conductivity (EC) | dS m-1 | 2,1 |

| Salinity | ‰ | 2,7 |

| Total Nitrogen | N g kg-1 | 1,8 |

| Available Phosphorus | P2O5 mg kg-1 | 84 |

| Exchangable Potassium | K2O mg kg-1 | 345 |

| Organic Matter | % | 2,9 |

| C/N ratio | 9,6 | |

| Total Limestone | % | 3,4 |

| C.E.C. | meq 100 g-1 | 15,8 |

| Parameter | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Organic C | % | 39.6 |

| Total N | % | 4.3 |

| NO3-N | % | < 0.1 |

| NH4-N | % | < 0.1 |

| P | % | 2.4 |

| K | % | 5.3 |

| Ca | % | 4.0 |

| Mg | % | 0.7 |

| Na | % | 0.3 |

| Cl | % | 1.3 |

| S | % | 1.0 |

| Fe | ppm | 13500 |

| Mn | ppm | 350 |

| Cu | ppm | 78 |

| Zn | ppm | 97 |

| B | ppm | 573 |

| Mo | ppm | 4.0 |

| C:N ratio | 9.2 |

| Trial | Treatment | Dose of fertilizer (g pot-1) |

N dose (kg ha-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | Control | - | 0 |

| Urea | 0.5 | 60 | |

| L60 | 4.7 | 60 | |

| L120 | 9.4 | 120 | |

| L180 | 14.1 | 180 | |

| Autumn | Control | - | 0 |

| Urea | 0.5 | 60 | |

| COF | 1.8 | 60 | |

| L60 | 4.7 | 60 | |

| L120 | 9.4 | 120 | |

| L180 | 14.1 | 180 |

| Treatment | PFPFW | NUEa FW |

NUEp FW |

PFPDW | NUEa DW |

NUEp DW |

REC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L 60 | 279.94 a | 67.23 | 786.95 | 30.42 a | 6.01 | 79.29 | 0.14 |

| L 120 | 138.32 ab | 31.96 | 654.22 | 14.99 ab | 2.78 | 41.49 | 0.07 |

| L 180 | 60.62 b | -10.29 | -1976.62 | 6.94 b | -1.19 | -139.75 | -0.03 |

| * | n.s. | n.s. | * | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Treatment | Chlorophyll a | Chlorophyll b | Chlorophyll a+b | Carotenoids |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controllo | 0.847±0.013 | 0.286±0.021 ab | 1.133±0.034 | 0.244±0.015 |

| Urea | 0.730±0.022 | 0.246±0.022 b | 0.976±0.024 | 0.209±0.008 |

| COF | 0.769±0.071 | 0.272±0.025 ab | 1.041±0.095 | 0.223±0.013 |

| L 60 | 0.766±0.032 | 0.255±0.022 b | 1.021±0.053 | 0.215±0.009 |

| L 120 | 0.770±0.052 | 0.270±0.014 ab | 1.040±0.062 | 0.219±0.021 |

| L 180 | 0.835±0.072 | 0.299±0.022 a | 1.133±0.094 | 0.224±0.021 |

| n.s. | * | n.s. | n.s. |

| Treatment | PFPFW | NUEa FW |

NUEp FW |

PFP DW |

NUEa DW |

NUEp DW |

REC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urea | 413.79 ab | -40.89 bc | 600.08 | 25.68 b | -3.03 b | 29.46 | -0.08 b |

| COF | 400.46 ab | -54.22 c | -432.58 | 25.57 b | -3.14 b | -20.22 | -0.08 b |

| L60 | 622.48 a | 167.80 a | 543.28 | 35.87 a | 7.16 a | 23.14 | 0.30 a |

| L120 | 345.88 b | 118.53 ab | 576.04 | 19.15 bc | 4.79 ab | 22.14 | 0.21 a |

| L180 | 245.13 b | 93.57 abc | 581.01 | 13.28 c | 3.71 ab | 22.97 | 0.16 ab |

| ** | * | n.s. | *** | * | n.s. | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).