1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised numerous questions about its impact on public health, particularly in relation to pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. While some early reports indicated that SARS-CoV-2 infection might have limited effects on pregnancy, others highlighted significant concerns regarding the potential implications for maternal and neonatal health [

1]. In 2021, a systematic review by the World Health Organization (WHO) concluded that SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy was associated with increased risks of maternal admission to intensive care units (ICU), neonatal admissions and preterm birth [

2]. Several studies identified risk factors for severe COVID-19 outcomes in pregnancy, including advanced maternal age (over 35 years), elevated body mass index (BMI), other than Caucasian, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, and preeclampsia [

2,

3,

4]. However, many of these studies were conducted outside of Europe, were hospital-based, or involved only a limited number of severe cases. Variations in the definitions of exposures and outcomes further underscored the need for population-based studies with standardized methodologies [

3]. Countries participating in the International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems (INOSS), including Slovakia’s Slovak Obstetric Survey System (SOSS), collect ongoing prospective data on maternal mortality, severe maternal morbidity, and rare pregnancy-related conditions [

5]. With the onset of the pandemic, some INOSS countries swiftly initiated national data collection efforts, including the CONSIGN (Covid-19 infectiOn aNd medicineS In pregnancy) study, which aimed to gather and share data on pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to hospitals [

2]. Slovakia initially joined the CONSIGN study but encountered significant challenges in tracking hospital admissions due to a lack of interconnected hospital systems. This limitation required us to redesign our study entirely, shifting our focus to developing a comprehensive population-based dataset. As a result, we were no longer able to participate in the INOSS project and proceeded independently to establish a new study structure. We created a project designed to map SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women in Slovakia called

COVID-19 PreMatOut (COVID-19 Pregnancy & Maternal Outcome). The aim of the study is to analyse the course and consequences of the infection on pregnancy, childbirth, puerperium, occurrence of obstetric and non-obstetric complications and neonatal conditions during their in-hospital stay. Further analysis is ongoing, including symptom severity in its relation to pre-existing conditions/ comorbidities of affected women and treatment approaches. After overcoming these challenges, we are now ready to present our first results.

2. Materials and Methods

This national retrospective observational cohort study was conducted among pregnant women in Slovakia who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 between March 1, 2020, and May 5, 2023. The study utilizes a population-based dataset and aims to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes. A multidisciplinary collaboration was established between several departments of the Faculty of Medicine of Comenius University, the Slovak Medical University, the Slovak Obstetric Survey System (SOSS) and the Public Health Office of the Slovak Republic. The Public Health Office maintained a nationwide registry of individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antigen testing, including pregnant women.

Clinical practices surrounding SARS-CoV-2 testing for pregnant women in Slovakia evolved throughout the pandemic. Initially, testing was primarily conducted in symptomatic individuals. However, as the pandemic progressed, routine monthly screenings were introduced, leading to the identification of asymptomatic cases. Additionally, universal screening for all obstetric admissions was recommended by the national health authorities during the second and third waves of the pandemic. Despite these efforts, limitations in the Public Health Office’s surveillance capacity, particularly during the peaks of the Delta and Omicron variants in densely populated areas, resulted in underreported cases.

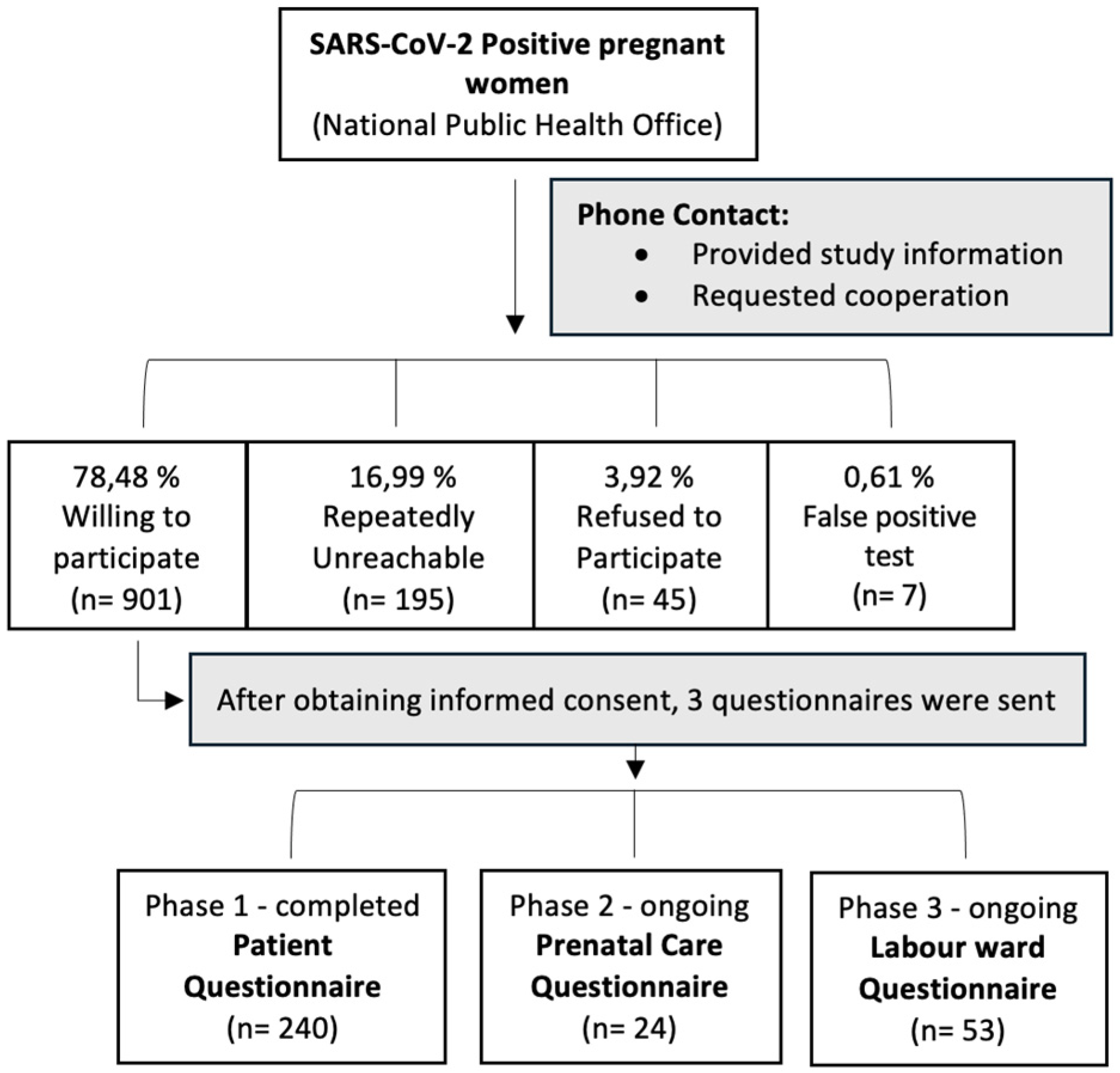

Based on records from the National Public Health Office, a total of 1,184 pregnant women who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were contacted by our research team for participation in the study. The individual steps of data collection are illustrated in

Figure 1.

Data Collection

The data collection process involved three key steps:

Patient Questionnaire: Participants were asked to provide subjective information regarding their infection and pregnancy course. All 1,184 women were contacted by telephone, informed about the study, and asked to provide consent. Informed consent forms were sent either via email or post. Out of all the women contacted, 750 agreed to participate and were given patient questionnaires. As of October 30, 2024, 240 completed questionnaires have been collected, marking the completion of this phase.

Prenatal Care Questionnaire: Information from prenatal care providers (gynaecologists) is being gathered to provide an objective account of each participant’s pregnancy course. Following consent from the participants, their primary care providers were contacted by telephone or email and asked to complete an online questionnaire. This phase is ongoing.

Hospitalization Questionnaire: Data from gynaecological and obstetrical facilities are being collected to document hospital stays, delivery outcomes, and any complications related to COVID-19. Hospitals were contacted over phone or email and asked to complete online questionnaires to provide objective accounts of the participants’ hospitalizations. This step allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on both maternal and neonatal health. This phase is ongoing.

Data Management and Analysis

All collected data are processed anonymously in compliance with current regulations on personal data protection (GDPR). The information is analysed using quantitative statistical methods. The study retroactively included all SARS-CoV-2 positive pregnant women from the start of the pandemic in March 2020, with additional participants enrolled until the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the pandemic’s end on May 5, 2023.

3. Results

A total of 1,148 eligible women who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were identified from the national database. After obtaining informed consent, 240 pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 completed the patient questionnaires for inclusion in the study.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population. The mean age of participants was 32 years (range 21–47) at the time of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the mean gestational age at infection was 23 weeks and 2 days. The group included 106 primiparous and 134 multiparous women.

The symptomatic course was dominant in our cohort, with only 1 % of women reporting an asymptomatic course. The most prevalent symptoms were related to the upper respiratory tract, reported by 91 women (42 %), followed by neurological symptoms in 38 % of cases. Less commonly, respondents experienced other symptoms related to the lower respiratory tract (16 %) and gastrointestinal symptoms (3 %).

Among the individual symptoms, fatigue and lethargy were the most frequent, affecting 70 % of women. This was followed by headaches (58 %), febrilities (57 %), and both anosmia and cough, each occurring in approximately 54 % of cases. A complete list of symptoms and their prevalence in our cohort can be found in

Table 2.

We also analyzed obstetric complications among the cohort of 240 women, distinguishing between those that occurred prior to and after contracting SARS-CoV-2 (

Table 3). A total of 52 women (22 %) reported experiencing complications during pregnancy before infection. The most common of these complications was bleeding (25 %), followed by imminent abortion or preterm labour (13 %), and haematological or gastrointestinal complications (each 8 %). After contracting SARS-CoV-2, 55 women reported new or worsening complications. The most prevalent post-infection complication was hypertension (29 %), followed by oedema (21 %), fetal growth restriction (16 %), and placental abnormalities (15 %).

In terms of the mode of delivery, 67% of the women delivered vaginally, while 33 % underwent caesarean section. Twenty-one women delivered preterm (range 32-37 week of gestation), and 21 women had COVID-19 during labour. Among these 21 women, 6 underwent caesarean sections, of which 2 were directly indicated due to the course of COVID-19, and 5 delivered preterm—most likely as a result of the infection (

Table 4).

Vaccination status was included in our study, with 103 of the 240 participants vaccinated against COVID-19. Of these, 30 were vaccinated pre-pregnancy, 17 during pregnancy, and 56 after giving birth. Mild side effects were reported, including fever, injection site pain, redness, and fatigue. Regarding vaccine types, 79 received Comirnaty (Pfizer-BioNTech), 11 Spikevax (Moderna), 7 Janssen (Johnson & Johnson), and 6 Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca)—

Table 5.

Out of 240 pregnant women in the study, 13 (5,42 %) required hospitalization due to COVID-19. In 9 cases, the reason was poor clinical status associated with obstetric complications such as preterm contractions, fever, dyspnoea, and fetal arrhythmia. The remaining 4 cases involved peripartal hospitalizations where COVID-19 led to labour at term. All hospitalizations required specialized care: 4 cases were treated in a COVID-19 specialized department, 4 in a gynaecological ward, 3 in a critical care unit, and 2 in an infectious disease department.

Treatment primarily involved symptomatic care, with specific therapies including bronchodilators, antibiotics, expectorants, immunomodulators, magnesium therapy, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), corticosteroids, and oxygen therapy. Non-invasive oxygen support was required in 70% of cases, while 30% required invasive ventilatory support. Among the 13 hospitalized women, 7 were over 35 years of age. Hospitalizations occurred predominantly in the third trimester (9 cases), with fewer in the second (3 cases) and first trimester (1 case). No significant comorbidities were identified in this group.

In addition to clinical data, our study recorded notable levels of psychological distress and disappointment among pregnant women with COVID-19. Many reported negative experiences with pandemic-related restrictions, such as cancelled check-ups, isolation during labour, and the requirement to wear masks, all of which heightened concerns for both maternal and fetal health.

Prenatal Care Findings

To assess prenatal care among pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2, 24 completed questionnaires were obtained directly from prenatal care providers. This phase remains ongoing, which limits the current sample size but allows us to gather objective clinical, laboratory, and ultrasound characteristics. The participant sociodemographic revealed that all participants were white women with a median age of 32 and a BMI of 22. Most were married (80 %), employed (88 %), and well-educated, with 70 % holding university degrees and 30 % being high school graduates. Additionally, the participants had no significant comorbidities. SARS-CoV-2 infections occurred in the second trimester for 45% of cases, the first trimester for 32%, and the third trimester for 23 %. Only two women were asymptomatic: four reported mild symptoms, while the majority experienced multiple symptoms, including fever, catarrhal symptoms, lethargy, and dyspnoea. In regard to laboratory findings, studies commonly report laboratory abnormalities in pregnant COVID-19 women, such as low white blood cell counts, low haemoglobin, thrombocytopenia, and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). In our study, however, the primary abnormality was an increase in CRP levels, as seen in

Table 6. No other significant laboratory abnormalities were observed.

Ultrasound evaluations, as shown in

Table 7, did not reveal significant differences in Doppler ultrasound or morphological findings between women with COVID-19 and the general population. Given the ongoing nature of the study and its limited sample size, no signs of fetal infection—such as cerebral calcifications or skin oedema—were detected, nor were there any structural abnormalities in any foetus. One foetus was observed to be small for gestational age (SGA) at the 10th percentile, while all pregnancies displayed normal amount of amniotic fluid. Our analysis did, however, reveal two statistically significant differences from the general population: crown-rump length (CRL) at 12 weeks was smaller, and abdominal circumference (AC) at 20 weeks was higher. While these findings may be attributed to the small sample size, which limits the robustness of p-value interpretations, they also suggest a potential area for further research to assess if these differences persist in larger populations.

Six women had pre-infection complications (emesis, gestational diabetes, fetal growth restriction, and threatened abortion). Post-infection, four developed additional complications, including missed abortion, fetal growth restriction, pruritus or risk of miscarriage. One woman experienced a missed abortion after SARS-CoV-2 infection, and another required hospitalization, resulting in both discontinuing regular prenatal observation. One missed routine diabetes screening, but most continued outpatient care. Symptomatic treatment was provided to most, with antibiotics and LMWH each prescribed in two cases.

Labour Ward Data

This section presents the objective clinical profile of the cohort (n=53), derived from labour ward data and supplemented by self-reported information. It is important to note that data collection is ongoing; thus, the sample size remains limited and smaller than anticipated. We are proceeding with the available data for the time being.

Most participants had a normal Body Mass Index (BMI) at conception (60 %), while 40 % were classified as overweight or obese. By the time of birth, BMI distribution shifted with 40 % overweight, 25 % obese, and 15 % with class III obesity, reflecting mostly physiologic pregnancy weight gain. The median age of participants was 33 years, with 94 % employed and 70 % married. Comorbidities were identified in 40 % of cases, most commonly hypothyroidism and thrombophilia. Most pregnancies were spontaneous conceptions (90 %), with 10 % conceived via assisted reproductive technology (ART).

Most births were spontaneous (53 %), with 15 % requiring induction due to conditions such as post-term pregnancy, oligohydramnios, or hypertensive disorders. Caesarean sections accounted for 28 % of deliveries, while operative vaginal birth occurred in 4%. Peripartal complications were identified in 18 cases out of 53 (34 %). The specific complications included severe haemorrhage (requiring ≥ 4 transfusion units), OASIS (Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury), uterine hypotony or atony, manual lysis of the placenta, premature rupture of membranes, and fetal hypoxia. Hospital stay duration averaged 3,8 days (

Table 8).

Neonatal Outcomes

The mean birth weight of newborns was 3420 grams (2200 g–4110 g), with an average length of 50 cm (46 cm- 54 cm). The mean cord blood pH at birth was 7.35, indicating a normal range of acid-base balance. Bonding was possible in 92 % of cases, with 8 % facing bonding challenges due to acute caesarean sections. Additionally, 17 % of newborns required isolation due to maternal COVID-19 infection, and rooming-in was possible in 80 % of cases. All newborns were reported healthy, with no issues identified in follow-up questionnaires conducted one year later (

Table 9).

4. Discussion

Pregnancy is widely recognized as a risk factor for a more severe course of COVID-19. Research has demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection increases the risk of adverse outcomes such as preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, intrauterine fetal death, and maternal ICU admissions, including cases requiring ventilation support or resulting in maternal death [

6,

7]. One of the earliest studies on this topic, led by Knight et al. in the UK, reported that about 10 % of pregnant patients hospitalized with COVID-19 required ventilatory support, with a case fatality rate of 1 % [

8].

The UKOSS study, a national prospective cohort study, examined 1,148 pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 confirmed during hospitalization in the UK from March to August 2020. It found that 63 % of these women were symptomatic, and the estimated incidence of hospitalisation with symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 was 2 per 1,000 pregnancies [

4].

Our COVID-19 Pre-MatOut project has shown a potentially higher hospitalization rate in Slovakia. 13 out of 240 (5.42 %) pregnant women who tested positive required hospitalization, including four in specialized COVID-19 wards and three in intensive care units due to ventilation support needs. Notably, the symptomatic course was particularly dominant, with only 1% of participants asymptomatic.

Symptom profiles in our study showed differences in frequency compared to another research. A systematic review analysing symptoms in 135 pregnant women (all in their third trimester) reported fever (67 %), cough (35 %), and myalgia / arthralgia (25 %) as the most common symptoms, with fatigue (15 %), dyspnoea (15 %), pharyngodynia (12 %) and diarrhoea (8 %) occurring less often [

9]. In our cohort fatigue was the most frequently reported symptom (70 %), followed by headache (58 %), febrilities (57 %), anosmia (55 %) and cough (53 %), myalgia / arthralgia (48 %), pharyngodynia (44 %), dyspnoea (21 %), and diarrhoea (7 %).

Regarding obstetric complications during pregnancies, we observed that the most common complication before SARS-CoV-2 infection was bleeding. After contracting SARS-CoV-2, women reported new or worsening complications, with the most prevalent being hypertension and oedema. These findings allow us to draw comparisons with the study by Zare et al., which highlighted significant increases in hypertensive disorders in pregnancy as well as the other complications during the pandemic [

10].

Notably, while our results indicate a rise in complications following COVID-19 infection, it is essential to consider the gestational age of the onset of these complications. The median gestational age at which SARS-CoV-2 was diagnosed in our cohort was 29th week. This is the only specific information available about gestational age, and while we do not have precise data on the median gestational age when complications arose, we can hypothesize that it was likely sooner than 29th week prior to the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2. Conversely, it is reasonable to assume that the women were in higher gestational week than 29th after the diagnosis.

This observation is consistent with the known complications typically associated with different gestational ages in the general population. For instance, complications such as bleeding and risk of miscarriage are more common in earlier stages of pregnancy, while conditions like elevated blood pressure and oedema are more prevalent later in pregnancy. Further studies are necessary to clarify the relationship between COVID-19 and gestational age-related complications, as well as there is need to differentiate these from the baseline obstetric risks.

While specific hospitalization rates were not statistically analysed, preliminary observations suggest that vaccination may be associated with reduced severity of COVID-19 symptoms in pregnant women. Observations suggest that women vaccinated during pregnancy experienced fewer symptoms and no hospitalizations, with positive outcomes for their infants. In contrast, while women vaccinated before pregnancy also experienced positive neonatal outcomes, they sustained a higher prevalence of the disease symptoms and in some cases also required hospitalization. These observations indicate a need for further investigation into how vaccination timing impacts hospitalization rates and symptom severity in pregnant populations with COVID-19.

Our study also observed a high rate of caesarean deliveries (~50%) in women with COVID-19, mirroring global trends where symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with a nearly doubled risk of caesarean section [

4,

11,

12,

13]. Neonatal outcomes in our cohort showed no significant differences in rates of stillbirth or neonatal death when comparing symptomatic and asymptomatic cases to pre-pandemic historical data from Slovakia [

4].

What’s unique about this study is its multifaceted approach. We gathered direct information from women, conducted personal inquiries that captured their anxieties and experiences, and documented both clinical and personal insights. At the start of the pandemic, pregnant women with COVID-19 were often advised to self-isolate and avoid in-person consultations, affecting their psychological well-being. Many expressed distresses over cancelled check-ups, isolation during labour, and mandatory mask-wearing, which intensified concerns for their own and their babies’ health. Our findings, which we plan to publish, align with Flaherty et al., who also found that maternity care during COVID-19 was predominantly experienced negatively, impacting both patients and providers [

14].

A key strength of this study, compared to most studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy, is our ability to examine complete pregnancy trajectories. This includes capturing subjective patient perception alongside objective clinical data. Unlike studies focused solely on hospitalized women, our data span lower gestational weeks, complications throughout pregnancy, and outcomes up to one year postpartum. While our data collection is ongoing, these preliminary results indicate that larger sample sizes may yield significant correlations.

Our findings on pregnancy and maternal outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic provide insights into the experiences of affected women. To further contextualize the impact of COVID-19 on maternal health in Slovakia, we considered preliminary data on maternal mortality from a co-author, which has not yet been formally published. According to this preliminary data, maternal mortality in Slovakia, monitored since 2007, showed a notable increase during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022). In this period, there were 7 maternal deaths associated with COVID-19 infection, with 4 patients passing directly due to COVID-19 and 2 with COVID-19 as a contributing factor in 2021, along with 1 additional COVID-19-related death in 2022. Overall, COVID-19-related cases accounted for nearly 37 % of the 19 total maternal deaths recorded in 2021 and 2022.

This increase underscores the heightened risks for pregnant women during the pandemic and highlights the importance of monitoring maternal health outcomes amid infectious disease outbreaks. Further research and official publications on this topic will provide a clearer understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on maternal mortality rates.

Variations in COVID-19 management among countries may stem from differences in intervention thresholds for both COVID-19 and obstetric complications. ICU admission policies, for example, may differ based on “at the time” available resources, local experience, and national guidelines. Additionally, early in the pandemic, limited data on COVID-19’s effects on pregnancy and the safety of COVID-19 treatments in pregnant women led to considerable differences in treatment approaches, with clinician discretion often shaping decisions [

3].

In Slovakia, thromboprophylaxis was conditionally recommended in April 2020, inspired by UK guidelines, though it was underutilized [

15,

16]. Similarly, corticosteroid therapy—found effective for reducing COVID-19 mortality in the RECOVERY trial [

17,

18] was rarely administered. This low utilization may reflect concerns regarding disease progression in pregnant patients. In general, our study found limited use of COVID-19-related treatments during the pandemic’s early phase, consistent with the literature [

19]. Pregnant women are routinely excluded from large international trials and early-phase studies, highlighting the need for pandemic-specific research protocols that can rapidly resume during a future crisis [

3].

To better prepare for a future pandemic, it is essential to have hibernated study protocols with all necessary approvals and allocated funding in place, enabling research to resume immediately when needed. Additionally, rapid registry linkages and robust, population-based data on infection burden, as well as key maternal and perinatal outcomes, can support healthcare systems in responding more effectively to future emergencies.

5. Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the sample size, which fell below initial expectations due to multiple obstacles encountered during data collection. Discrepancies between actual cases and figures from the National Public Health Office, a declining response rate at each stage, and technical issues with our digital platform restricted data availability. To address these challenges, we plan to expand our study by gathering retrospective data directly from Slovak hospitals. This approach will allow us to include critically ill or deceased COVID-19-positive women who were initially unable to consent, broadening our study’s scope and statistical robustness.

6. Conclusions

This national study demonstrated that symptomatic COVID-19 was prevalent among pregnant women in Slovakia, with a higher hospitalization rate compared to other countries. Higher maternal age and infection during the second trimester were associated with increased hospitalization risk. Slightly elevated rates of caesarean and preterm births suggest an indirect impact of SARS-CoV-2 on maternity care in high-income settings, warranting further investigation. Overall, maternal and neonatal outcomes were largely positive; however, administering proven effective treatments could further align outcomes with those seen in the general population. Our study provided a unique, multi-dimensional perspective on pregnancy during the pandemic, capturing the mother’s personal concerns and the objective perspectives from prenatal and labour care settings. Trends such as elevated CRP levels in infected women and normal ultrasound findings were also observed. An upcoming expansion of this study, with follow-up through INOSS, is expected to deepen our understanding of COVID-19’s impact on maternal health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., L.K. and M.B..; Methodology, A.K., L.K., Z.K. and L.I.; Validation, J.M., J.N. and A.K.; Formal Analysis, A.K., A.G.; Investigation, A.G., C.M. D.K.; Data Curation, A.K., L.K., J.M., J.N., A.G., C.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.G.; Writing—Review & Editing, A.G., C.M., L.K. and A.K..; Supervision, A.K., M.B.; Project Administration, A.K., L.K.; Funding Acquisition, A.K., M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A grant provided by ESET foundation** (90 %) and co-financed by Faculty of Medicine; Comenius University Bratislava (10 %) used for development of the dedicated website that facilitated the digitalization of data collection. Same platform not only streamlined the data collection process but also serves as a resource for disseminating interim study results and providing information on a topic for as well as health care professionals as well as for the public. ** Grant call: Popularisation of science and research; Category: Effective tools for management of the COVID-19 pandemic (2021); Contract No. Z/2021/1061/VIII/LF/OPP; Contract ID: 5795440.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University Bratislava and University Hospital in Bratislava (Ref. Number 62/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the women who participated in this study and took the time to complete our questionnaires. We also extend our appreciation to the healthcare providers, including gynaecologists in prenatal care and obstetricians in labour wards, for their invaluable cooperation and support throughout this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ischenko, G.I. COVID-19 during pregnancy. Analytical inspection. Ukrainian Journal of Perinatology and Pediatrics 2021, 85, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allotey J., Stallings E., Bonet M. et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2020. [CrossRef]

- de Bruin O., Engjom H., Vousden N. et al. Variations across Europe in hospitalization and management of pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 during the initial phase of the pandemic: Multi-national population- based cohort study using the International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems (INOSS). Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023, 102, 1521-1530. [CrossRef]

- Vousden N., Bunch K., Morris E. et al. The incidence, characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women hospitalized with symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK from March to September 2020: A national cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 5. [CrossRef]

- Knight, M. The International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems (INOSS): benefits of multi-country studies of severe and uncommon maternal morbidities. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014, 93, pp 127-131. [CrossRef]

- Vousden N., Knight M., Bunch K. et al. Management and implications of severe COVID-19 in pregnancy in the UK: data from the UK Obstetric Surveillance System national cohort. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2022, 101 (4), pp 461-470. Epub 2022 Feb 25. PMID: 35213734. [CrossRef]

- Vousden, N. , Knight M., Bunch K. et al. Severity of maternal infection and perinatal outcomes during periods of SARS-CoV-2 wildtype, alpha, and delta variant dominance in the UK: prospective cohort study. BMJ Medicine 2022, 1. [CrossRef]

- Knight, M. , Bunch K., Vousden N. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of preg- nant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: national population based cohort study. BMJ 2020; 369: m2107. [CrossRef]

- Hassanipour, S. , Faradonbeh S.B., Khalil M., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pregnancy and COVID-19: Signs and symptoms, laboratory tests, and perinatal outcomes. Int J Reprod Biomed 2020, 18 (12), 1005-1018. [CrossRef]

- Zare F., Karimi A., Daliri S. Complications in Pregnant Women and Newborns Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2024, 29(1), pp 91-97. [CrossRef]

- Silva C.E.B.D., Guida J.P.S., Costa M.L. Increased Cesarean Section Rates during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Looking for Reasons through the Robson Ten Group Classification System. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2023, 45(7): e371-e376. [CrossRef]

- Pryshliak O.Y., Marynchak O.V., Kondryn O.Y., et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of COVID-19 in pregnant women. J Med Life. 2023, 16(5): pp 766-772. [CrossRef]

- Bilodeau-Bertrand M., Liu S., Auger N. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2021, 193 (16): E540-E548. [CrossRef]

- Flaherty S.J., Delaney H., Matvienko-Sikar K., Smith V. Maternity care during COVID-19: a qualitative evidence synthesis of women’s and maternity care providers’ views and experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22(1): pp 438. [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in Pregnancy. Accessed September 12, 2024. Available online: https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/xsubnsma/2022-03-07-coronavirus-covid-19-infection-in-pregnancy-v15.pdf.

- Use of heparins in adult patients with COVID-19. Accessed September 12, 2024. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1267737/Eparine_update_02_13.05.2021_eng.pdf.

- McIntosh, J.J. Corticosteroid guidance for pregnancy during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Perinatol 2020, 37, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P., Lim W.S., et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, pp 693-704.

- Giesbers S., Goh E., Kew T., et al. Treatment of COVID-19 in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021, 267, pp 120-128.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).