1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic had a significant impact on the world, with more than 700 million people affected by the virus and nearly 7 million deaths recorded [

1]. Although it has been suggested that pregnant women are no more susceptible to the infection than the general population, they are particularly vulnerable to severe infections due to changes in their immune system, which can increase the risk of severe disease and adverse outcomes for both the mother and the fetus [

2,

3].

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, has been shown to cause respiratory distress, pneumonia, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), all of which can lead to adverse outcomes in pregnant women [

4,

5].

Inflammation is a crucial component of the immune response to infection [

6]. However, excessive or prolonged inflammation can lead to tissue damage and other complications such as hemodynamic changes and organ failure [

6,

7]. In pregnant women, inflammation can lead to adverse outcomes, including preterm labor, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction [

8,

9,

10,

11]. COVID-19 has been shown to cause a systemic inflammatory response, which can have significant implications for both the mother and the fetus [

12,

13].

Recent studies have reported an increased risk of adverse outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19, including preterm birth, preeclampsia, and fetal distress [

14,

15,

16].

However, there is currently limited knowledge regarding the effects of maternal COVID-19 infection during pregnancy on the inflammatory profile and immune system of the newborn. Analyzing inflammatory markers in neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 can offer valuable insights into the influence of maternal infection on the fetal immune system and the potential risks linked to this exposure.

Neutrophils-to-lymphocytes ratio (NLR), platelets-to-lymphocytes (PLR), derived neutrophils-to-lymphocytes ratio (dNLR) and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) are all markers of inflammation and immune response [

17,

18]. These ratios have been used as potential markers of inflammation in various conditions, including infectious diseases, cancer, and autoimmune disorders [

19,

20,

21].

In the context of COVID-19, studies have shown that elevated NLR and PLR levels are associated with disease severity and poor outcomes in adult patients [

18]. However, little is known about the utility of these markers in evaluating the impact of maternal COVID-19 infection on the fetal immune system and neonatal outcomes.

The aim of this study was to assess inflammatory markers in newborns whose mothers were infected with SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

A retrospective cohort study was conducted on a cohort of 296 patients who underwent parturition at Premiere Hospital in Timisoara between May 2021 and January 2022. These patients were stratified into two distinct groups according to their COVID-19 status during the gestational period.

2.2. Participants

The eligibility criteria for the study included pregnant women who gave birth at Premiere Hospital in Timisoara between May 2021 and January 2022. For the COVID-19 positive group, patients had to have a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy, as diagnosed by RT-PCR testing. Patients with pre-existing medical conditions such as chronic hypertension, diabetes, or autoimmune disorders were excluded from the study. Patients with other proven infections during pregnancy were also excluded from the analysis.

2.3. Variables

The primary outcome of the study was to evaluate the levels of inflammatory markers, including NLR, dNLR, PLR, and SII, in neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 during pregnancy.

The main exposure of interest was maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy, confirmed by RT-PCR testing.

Potential confounders included maternal age and trimester of infection.

2.4. Data Sources/Measurement

Demographic and clinical characteristics as well as laboratory results were extracted from the patients’ electronic records using standard forms.

SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed by RT-PCR testing, following the guidelines of the World Health Organization. Maternal comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes were diagnosed based on medical history, physical examination, and laboratory testing. Inflammatory markers were measured from peripheral blood samples using standard laboratory techniques. Both the NLR and PLR are calculated by dividing the absolute count of neutrophils and platelets, respectively, by the absolute count of lymphocytes. dNLR was calculated using the following formula: neutrophil count / (WBC count − neutrophil count). SII was determined by the following formula: (N×P)/L (N, P and L represent the number of neutrophils, the number of platelets and the number of lymphocytes, respectively). The immunoreactivity of SARS-CoV-2, in both neonates and mothers, was ascertained through the detection of IgG or Anti-S antibodies in peripheral blood samples.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was executed employing the Python programming language. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical variables were compared using the Fisher’s exact test. Correlation coefficients between continuous variables were calculated using Spearman rank correlation. The Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to determine if there were statistically significant differences between two or more independent groups on laboratory inflammatory tests. To examine the effects on inflammatory tests of categorical independent variables (COVID-19 status during pregnancy or maternal/neonatal immunoreactivity) while adjusting for other variables (gestational or trimester of infection), multiple linear regression was performed.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

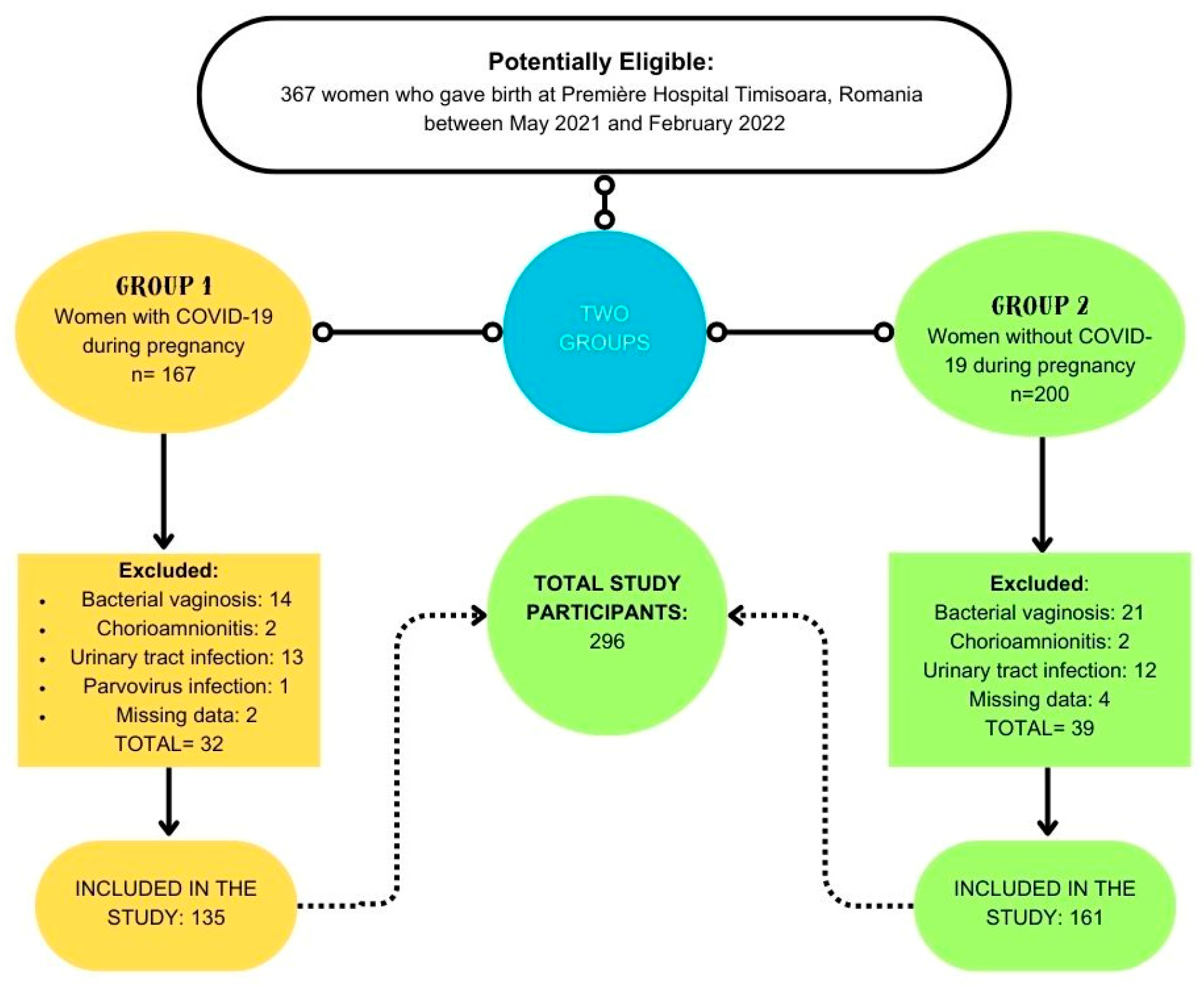

Out of the initial cohort of 367 women who underwent childbirth at Premiere Hospital Timisoara during the study period, a total of 71 were subsequently excluded. Consequently, the final analysis encompassed 296 participants, with 135 individuals having contracted COVID-19 during their gestational period, and 161 individuals who remained COVID-19-free throughout pregnancy (

Figure 1).

3.1. Descriptive Data

Clinical and demographic characteristics did not show statistically significant differences between groups (

Table 1).

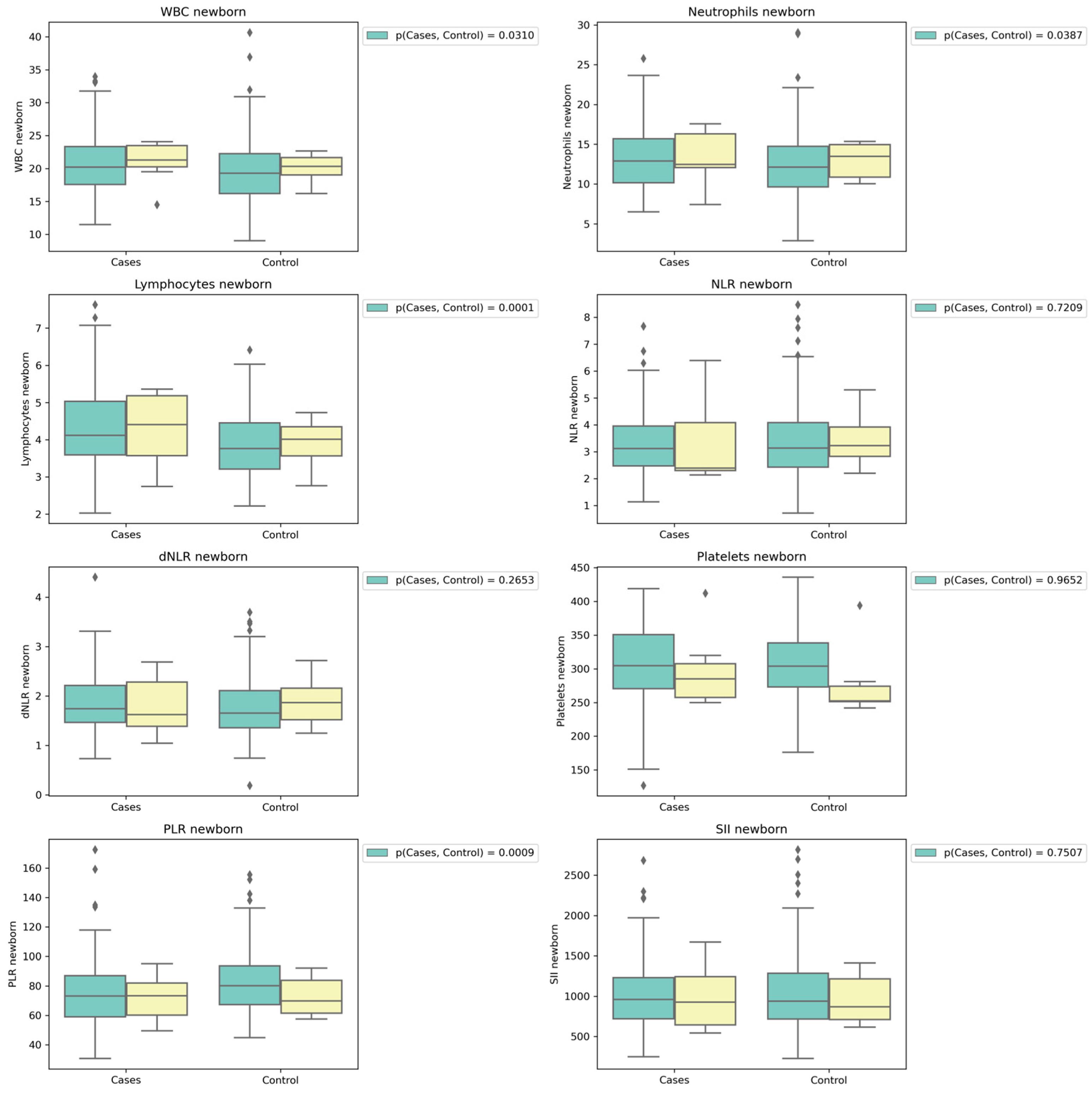

Laboratory findings indicate that there were no noteworthy disparities in maternal parameters between the two groups. However, concerning the neonates, it is noteworthy that white blood cell counts (WBC), lymphocyte counts, and neutrophil counts exhibited statistically significant elevations among newborns whose mothers had contracted COVID-19 during pregnancy. Regarding NLR, dNLR, and SII, there were no discernible significant differences observed between the groups. Nonetheless, intriguingly, PLR exhibited notably higher values among infants whose mothers remained free of COVID-19 during their gestational period (

Table 2).

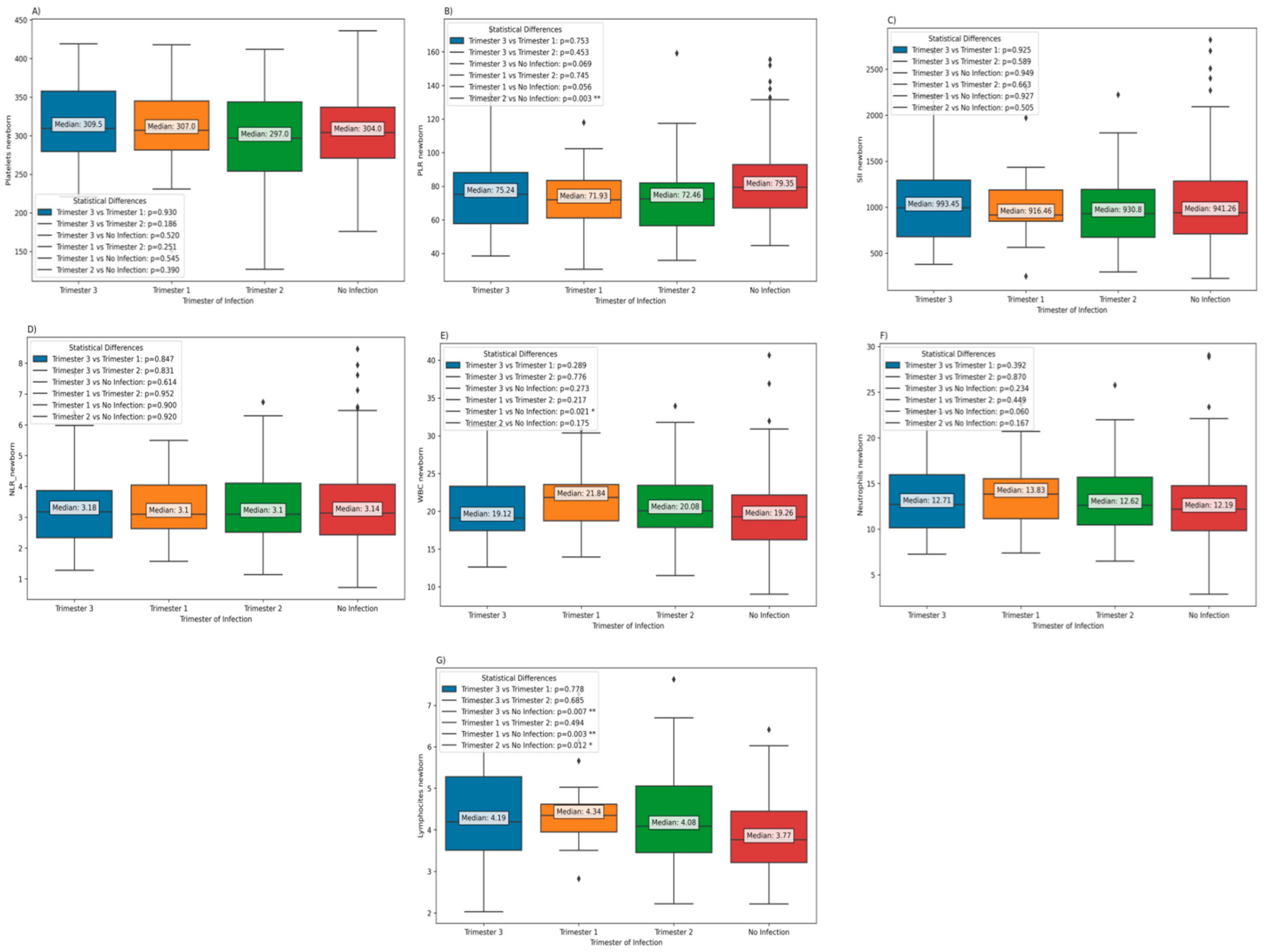

Furthermore, the results indicate the absence of significant differences in platelet counts, PLR, SII, NLR, and neutrophil values, according trimester of infection. Nevertheless, notably, white blood cell (WBC) counts were observed to be significantly elevated in neonates born to mothers who contracted the infection during the first trimester, as opposed to neonates born to mothers who did not experience a COVID-19 infection during pregnancy. In addition, it is worth noting that the lymphocyte counts in neonates born to mothers who remained COVID-19-free during pregnancy were significantly diminished in comparison to those born to mothers who had contracted COVID-19 during pregnancy, irrespective of the trimester in which the infection occurred (

Figure 2).

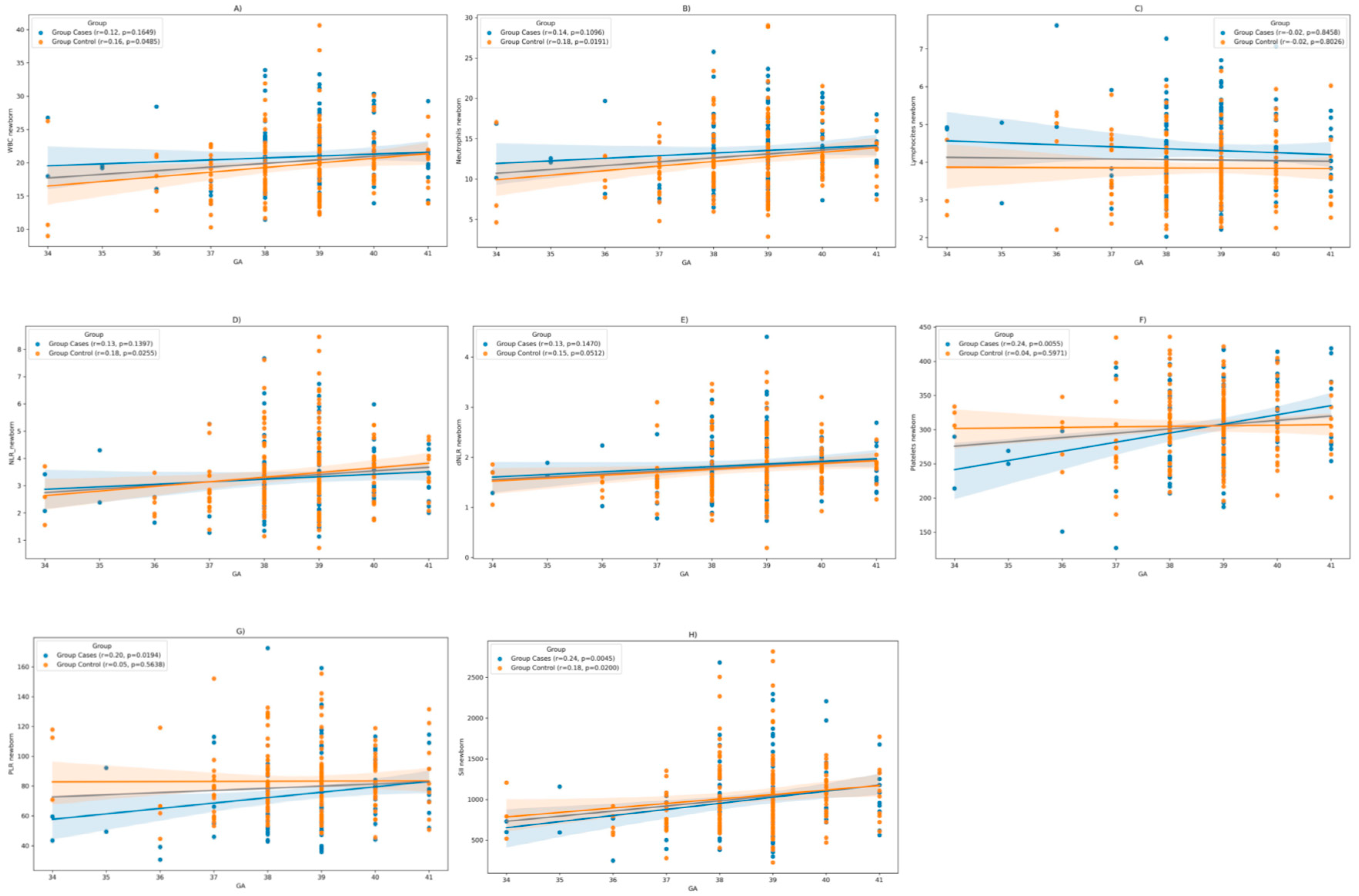

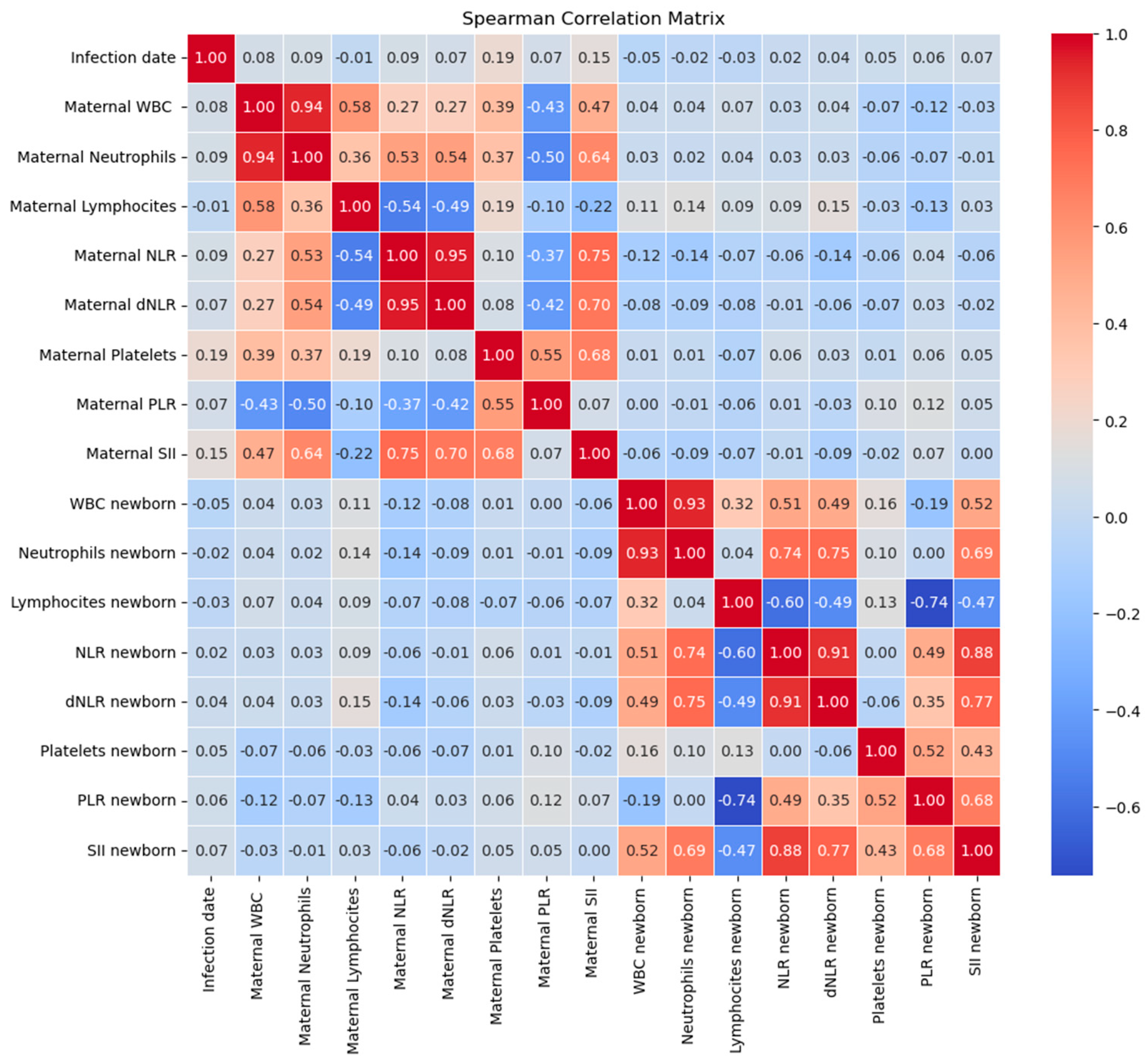

Moreover, we posited that the laboratory findings in neonates might be subject to the influence of gestational age (GA) at the time of birth. Spearman correlation analysis reveals a positive correlation between GA and WBC counts (r= 0.16, p= 0.04), respectively, neutrophil counts (r=0.18, p=0.01) in the control group (COVID-19 negative during pregnancy). However, in the cases group (COVID-19 positive during pregnancy), no statistically significant correlation was discerned. Additionally, there is no notable correlation between lymphocyte counts and gestational age in either group.

In terms of NLR, there is a positive correlation with GA in the control group (r= 0.18, p= 0.02), with no significant correlation in the cases group. In contrast, platelets and PLR correlated positively with gestational age in the case groups (r = 0.24, p = 0.005; respectively r = 0.20, p = 0.01), while in the control group there was no statistically significant correlation. In terms of SII it correlates positively with GA in both groups (

Figure 3).

Furthermore, Kruskal-Wallis Test was conducted to examine the differences on laboratory tests results according to COVID-19 status during pregnancy (Group) and gestational age at birth (

Table 3). There are statistically significant differences in lymphocyte counts and the Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) among different levels of GA and groups. However, for the other laboratory tests, there are no statistically significant differences among these groups.

In addition, multiple linear regression was used to test whether GA and COVID-19 status during pregnancy significantly predicted the outcome of laboratory tests (

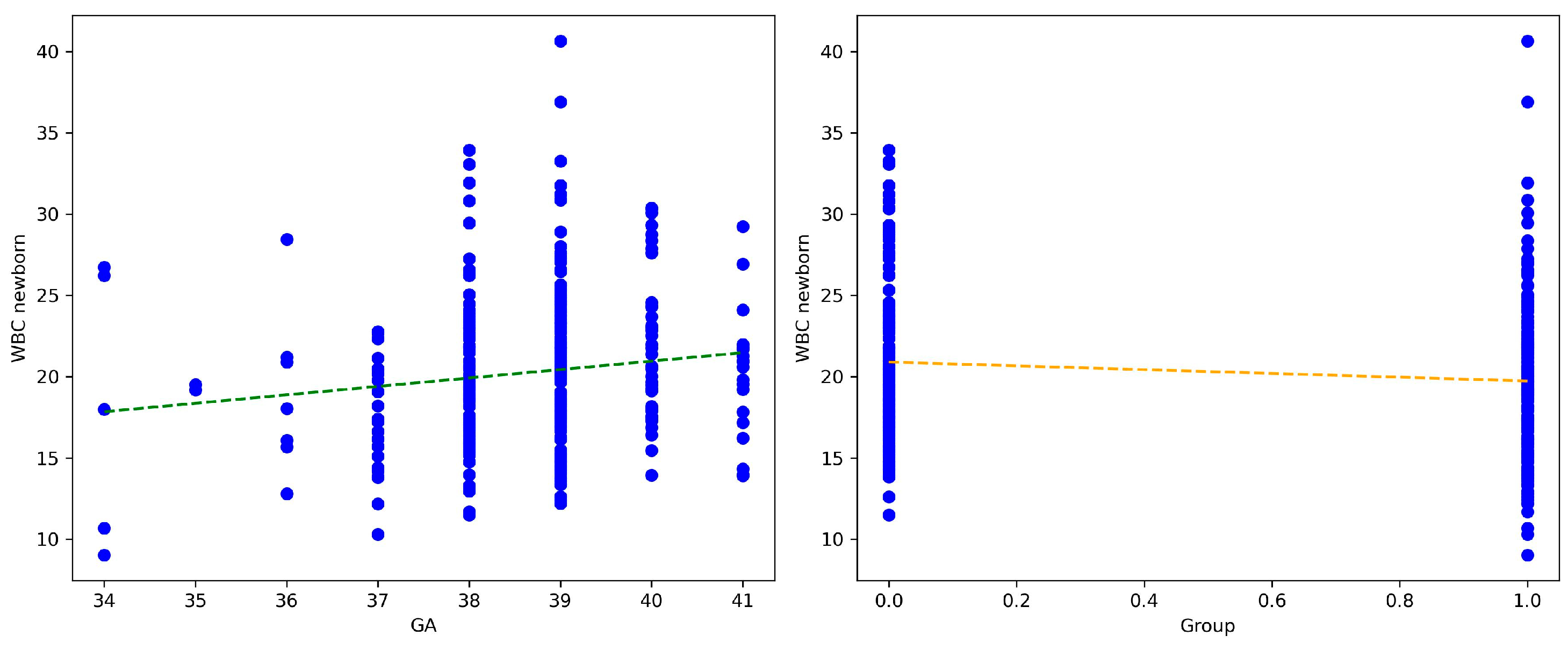

Table 4).

Both GA and COVID-19 status are significant predictors of WBC counts in newborns (

Figure 4).

In addition, COVID-19-free during pregnancy is a significant predictor, with a negative effect on lymphocyte counts and with a positive effect on PLR. However, COVID-19 status during pregnancy does not significantly predict NLR (

Table 5).

Further, taking into account the presence of pre-eclampsia, in women without this pathology, it is concluded that the WBC, neutrophil and lymphocyte values of newborns were significantly higher in infants from the case group. In women with pre-eclampsia, the values of all biomarkers did not show significant differences between control and case groups (

Figure 5).

Furthermore, when including pre-eclampsia as a covariate in the regression analysis, the results show that COVID status remains a significant predictor of neonatal WBC, Lymphocytes, and PLR.

3.2. Subgroup Analysis-COVID-19 Positzive during Pregnancy

Regarding the correlation of blood test values of newborns of COVID-19 positive mothers during pregnancy, with the infection date (gestational weeks), WBC count in newborns exhibited a weak negative correlation with the infection date with no statistical significance (rho = -0.046, p= 0.59). No significant correlations were observed between the infection date and neutrophil or lymphocyte counts in newborns

Neonatal NLR and derived NLR (dNLR) demonstrated positive correlations with the infection date but also without statistical significance (rho= 0.019, p= 0.82 and rho = 0.03, p= 0.68, respectively).

PLR and SII in newborns exhibited positive correlations with the infection date, without statistical significance (rho = 0.059, p= 0.49 and rho = 0.066, p= 0.44, respectively) (

Figure 6).

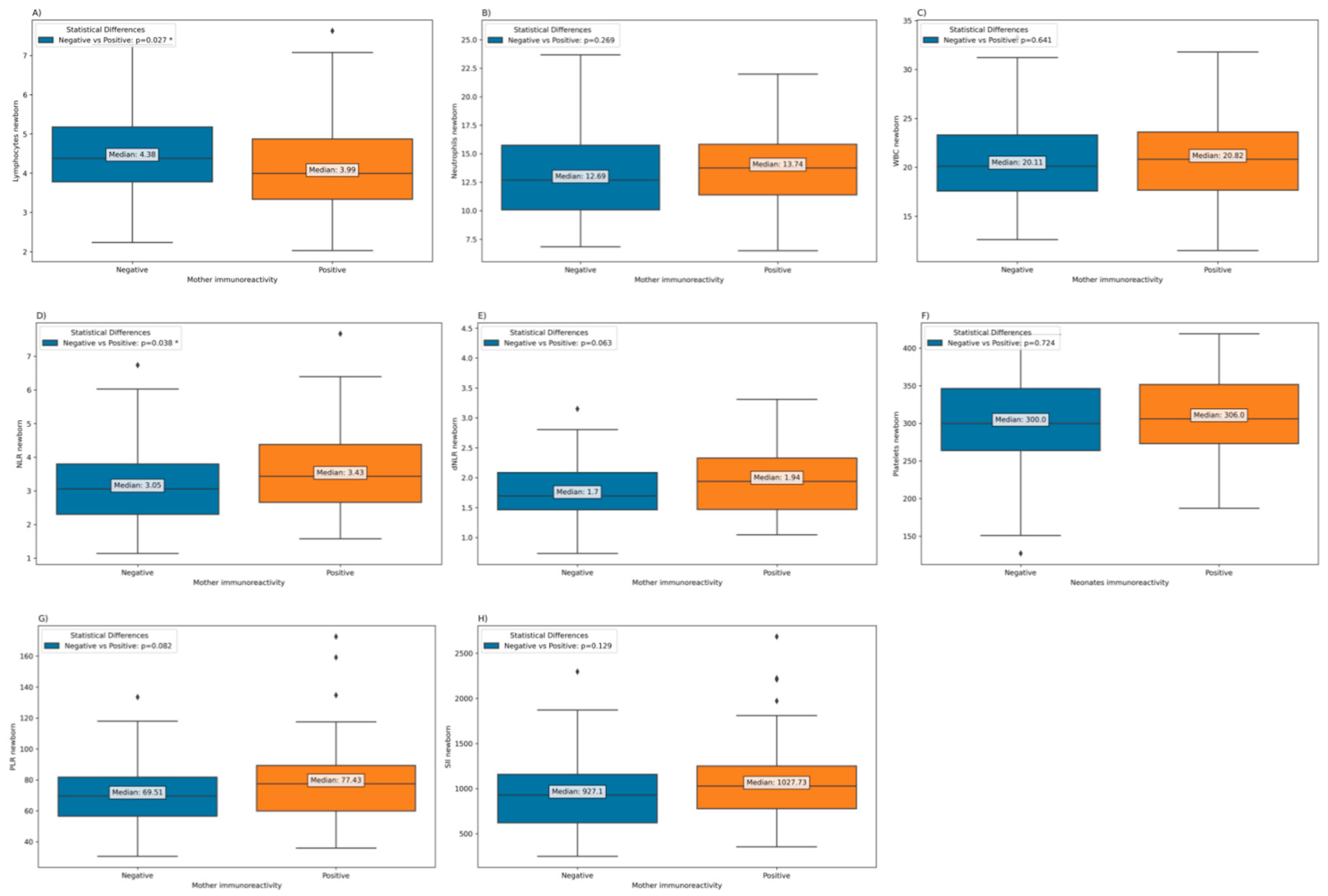

Depending on the immunoreactivity of SARS-CoV-2 in mothers, a significantly lower lymphocytes count is observed in newborns from immunopositive mothers (

Figure 3). However, in terms of neutrophils and WBCs, counts are higher in newborns of immunopositive mothers, but the difference is not statistically significant. Additionally, the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) was significantly elevated in newborns born to mothers who exhibited immunoreactivity, in contrast to those born to mothers who had experienced COVID-19 during pregnancy but were no longer immunoreactive at the time of childbirth. (

Figure 7).

Table 6 presents the results of a multiple linear regression analysis that examines the relationship between various laboratory test results in newborns and maternal immunoreactivity, adjusted for both gestational age (GA) and trimester of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy. The results suggest that there is generally no statistically significant association between maternal immunoreactivity and most of the laboratory test results in newborns after adjusting for GA and trimester of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy. The only borderline significant association is observed for NLR.

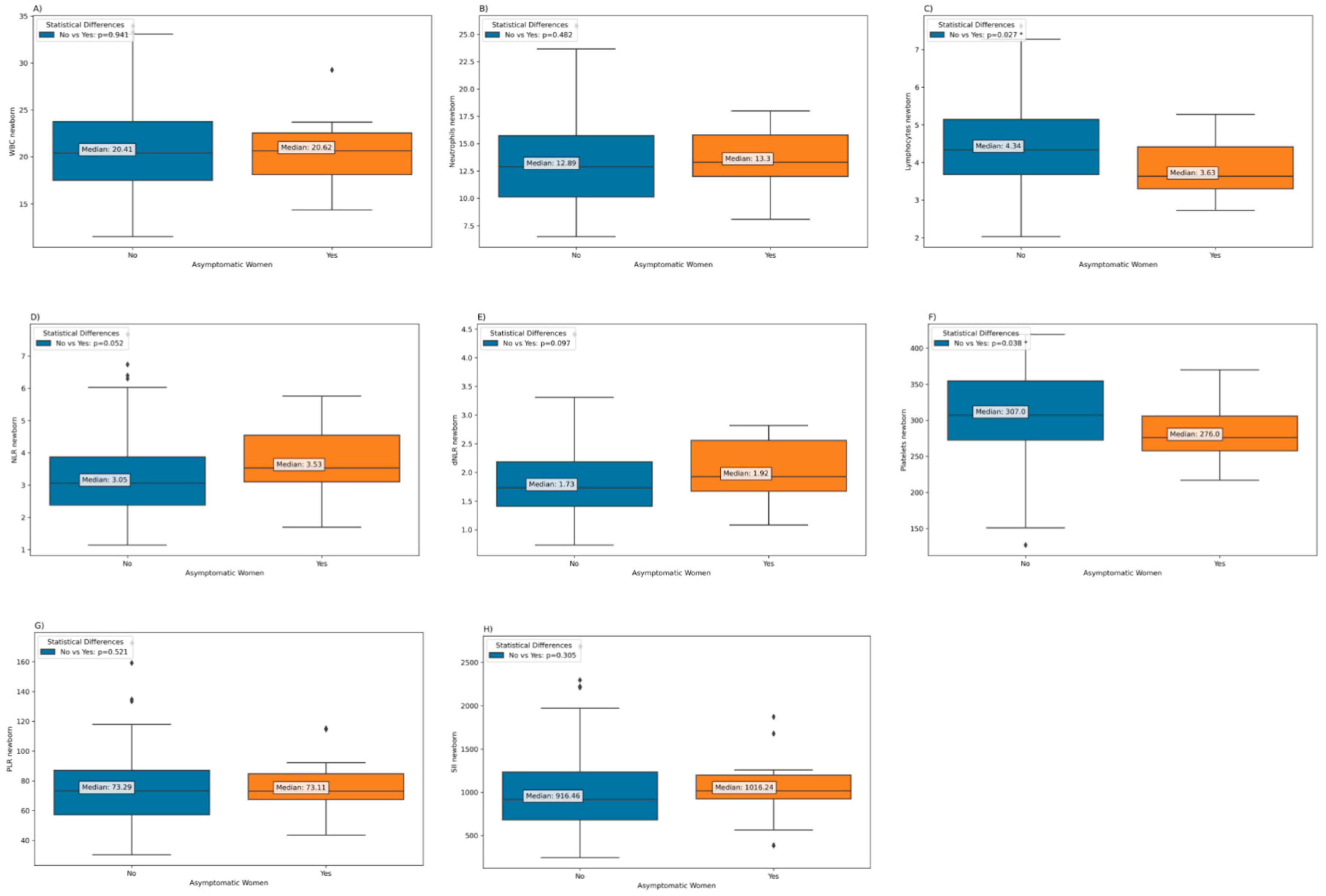

Regarding neonatal parameters according to maternal COVID-19 severity, it was found that infants born to mothers who were asymptomatic during the disease had significantly lower levels of lymphocytes and platelets at birth compared to infants whose mothers showed clinical symptoms during the disease (

Figure 8).

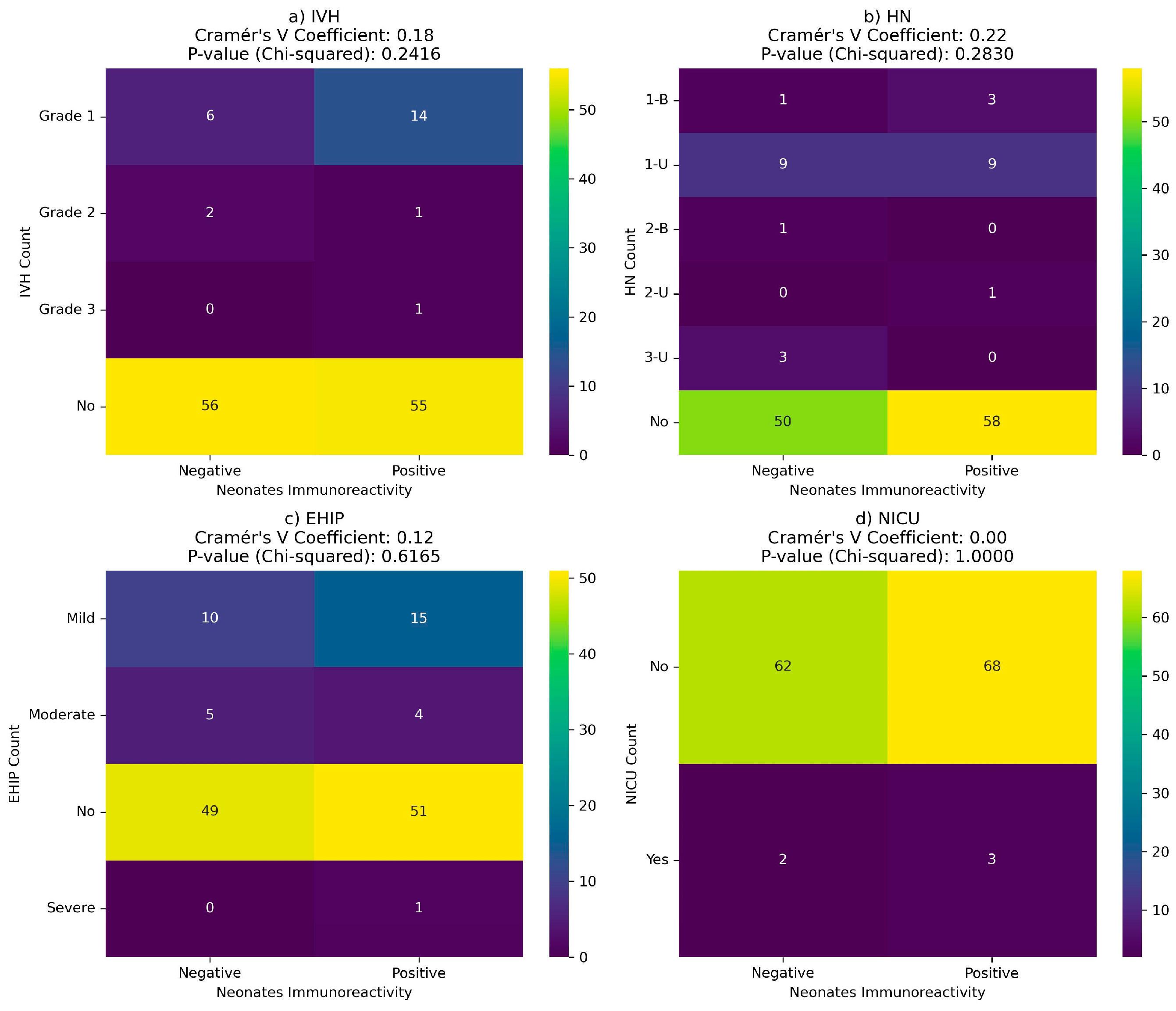

3.3. Neonatal Outcomes in Newborns Born to COVID-19 Positive Women during Pregnancy

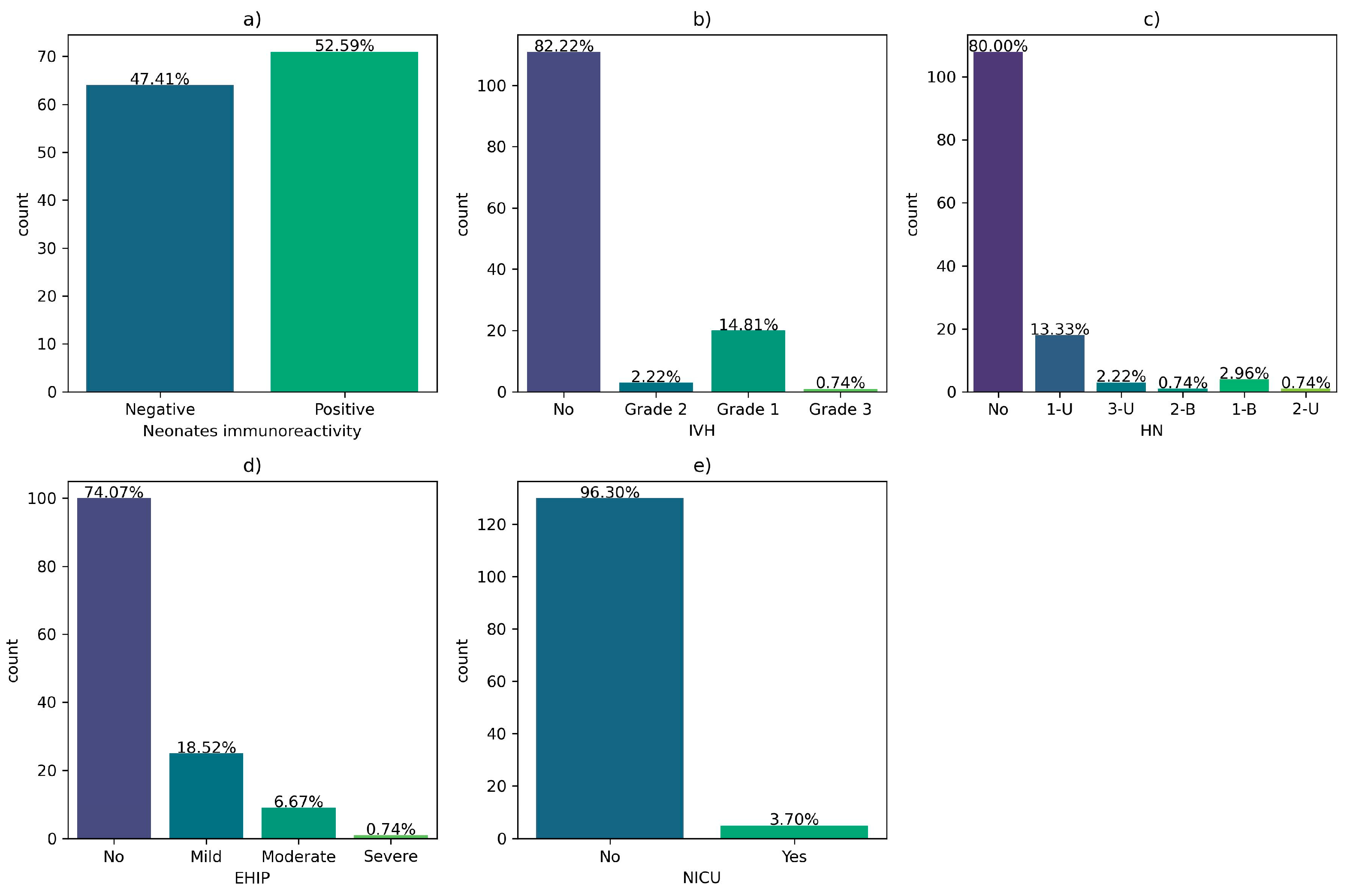

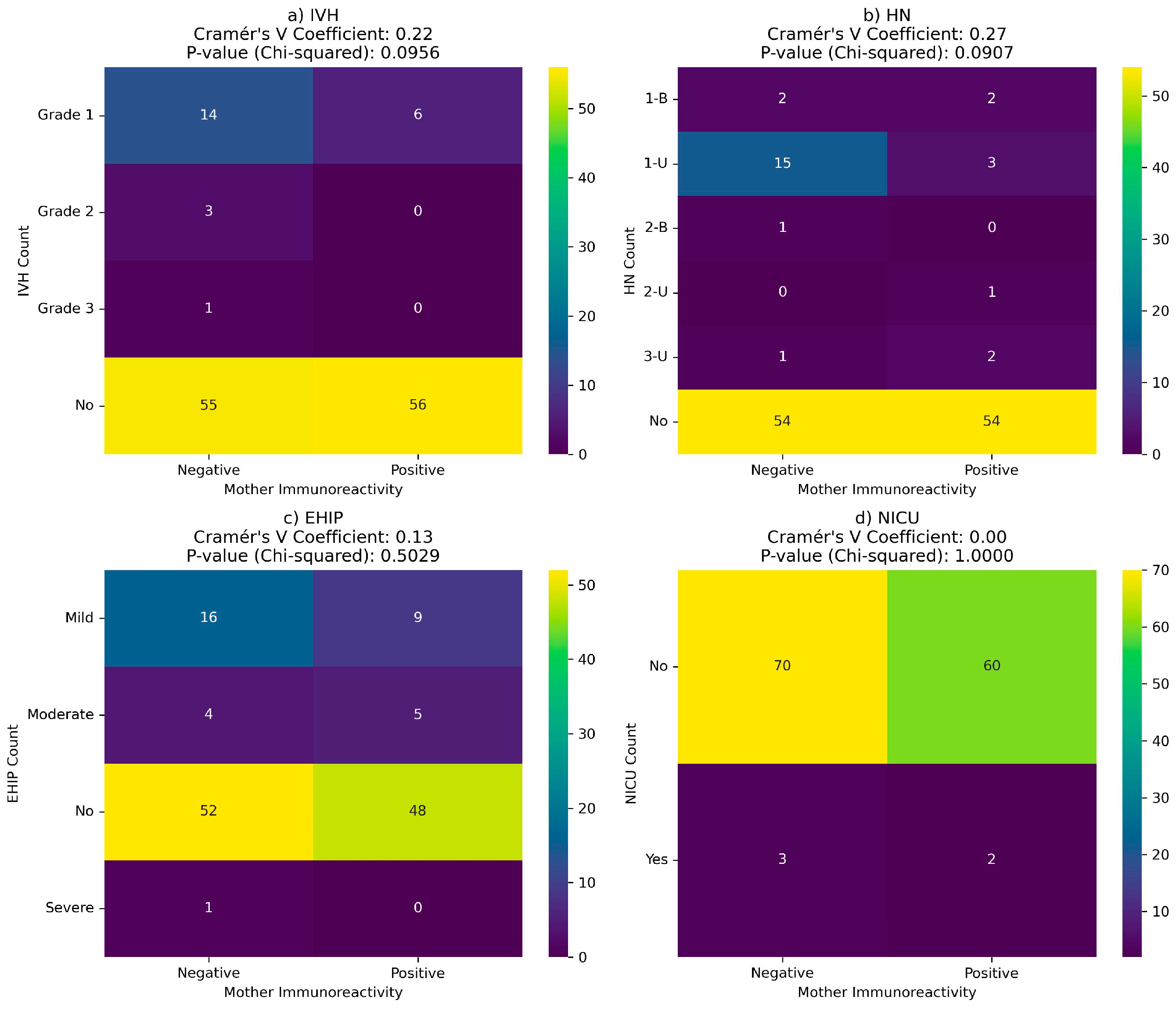

Regarding the outcomes of newborns of COVID-19 positive mothers during pregnancy, 52.59% of them were immunoreactive to COVID-19 at birth. Also, 13% of them developed grade 1 intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), 13.3% unilateral grade 1 hydronephrosis (HN), 18.52% hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (EHIP), and 3.70 were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Figure 9.

Neonatal outcomes of infants born to COVID-19 positive women during pregnancy: (a) Neonatal immunoreactivity; (b) Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH); (c) Hydronephrosis (HN); (d) hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (EHIP); (e) Neonatal dNLR; (f) Neonatal Platelets; (g) Neonatal PLR; h) the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

Figure 9.

Neonatal outcomes of infants born to COVID-19 positive women during pregnancy: (a) Neonatal immunoreactivity; (b) Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH); (c) Hydronephrosis (HN); (d) hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (EHIP); (e) Neonatal dNLR; (f) Neonatal Platelets; (g) Neonatal PLR; h) the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

There is no correlation between neonatal complications and maternal or newborn immunoreactivity at birth (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

However, in newborns from COVID-19 positive mothers during pregnancy, ANOVA results indicate significant associations between inflammatory laboratory tests and neonatal outcomes. The Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) in newborns also shows significance (p-value of 0.04), particularly in relation to IVH. Additionally, the Systemic Immune-Inflammatory Index (SII) demonstrates a significant p-value of 0.02, suggesting a potential link to adverse outcomes such as EHIP (Early Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy). Notably, the Platelets newborn count and Platelets-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) exhibits a statistically significant p-values of 0.04 respectively 0.01, indicating a potential correlation with NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit) admission (

Table 7).

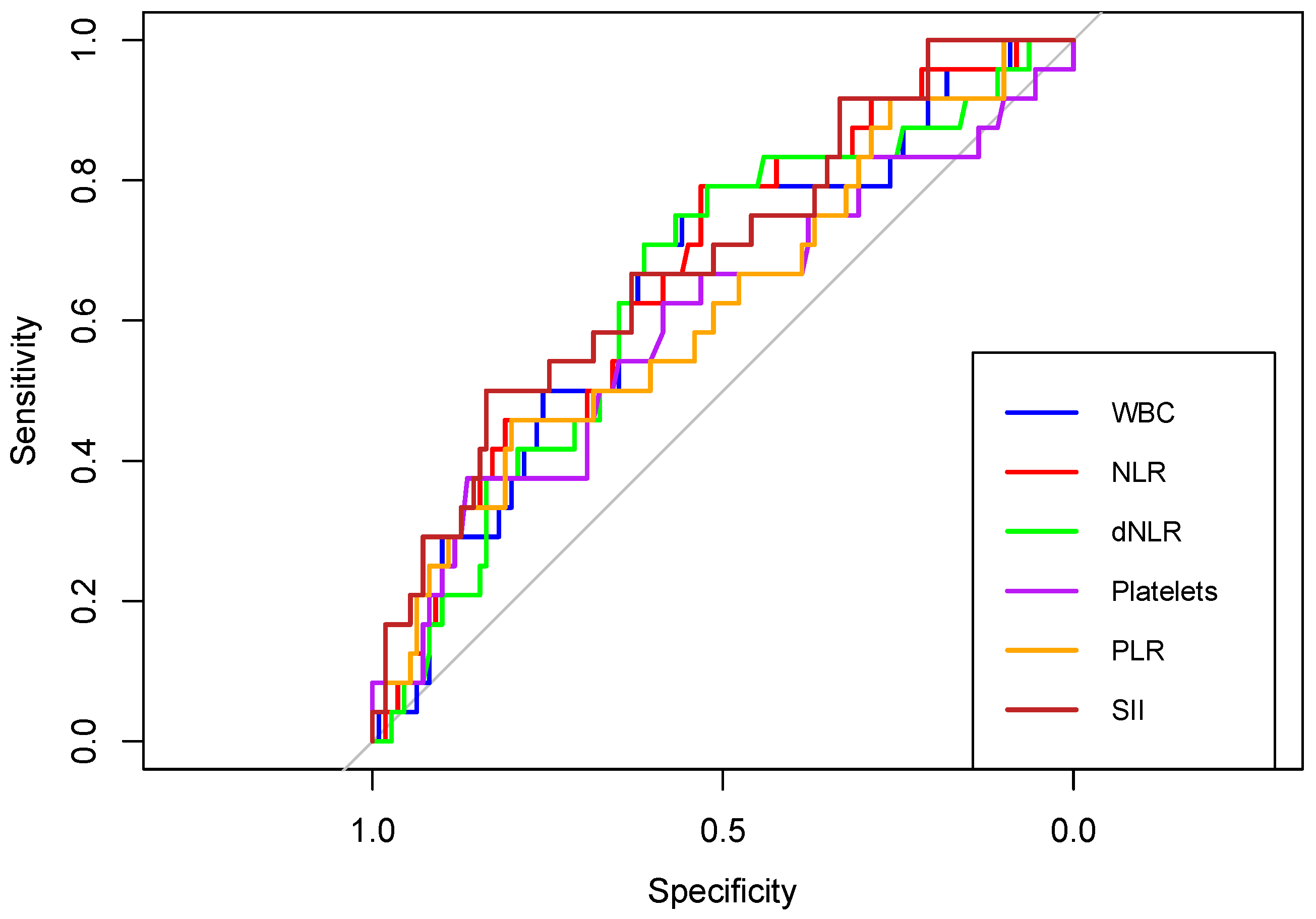

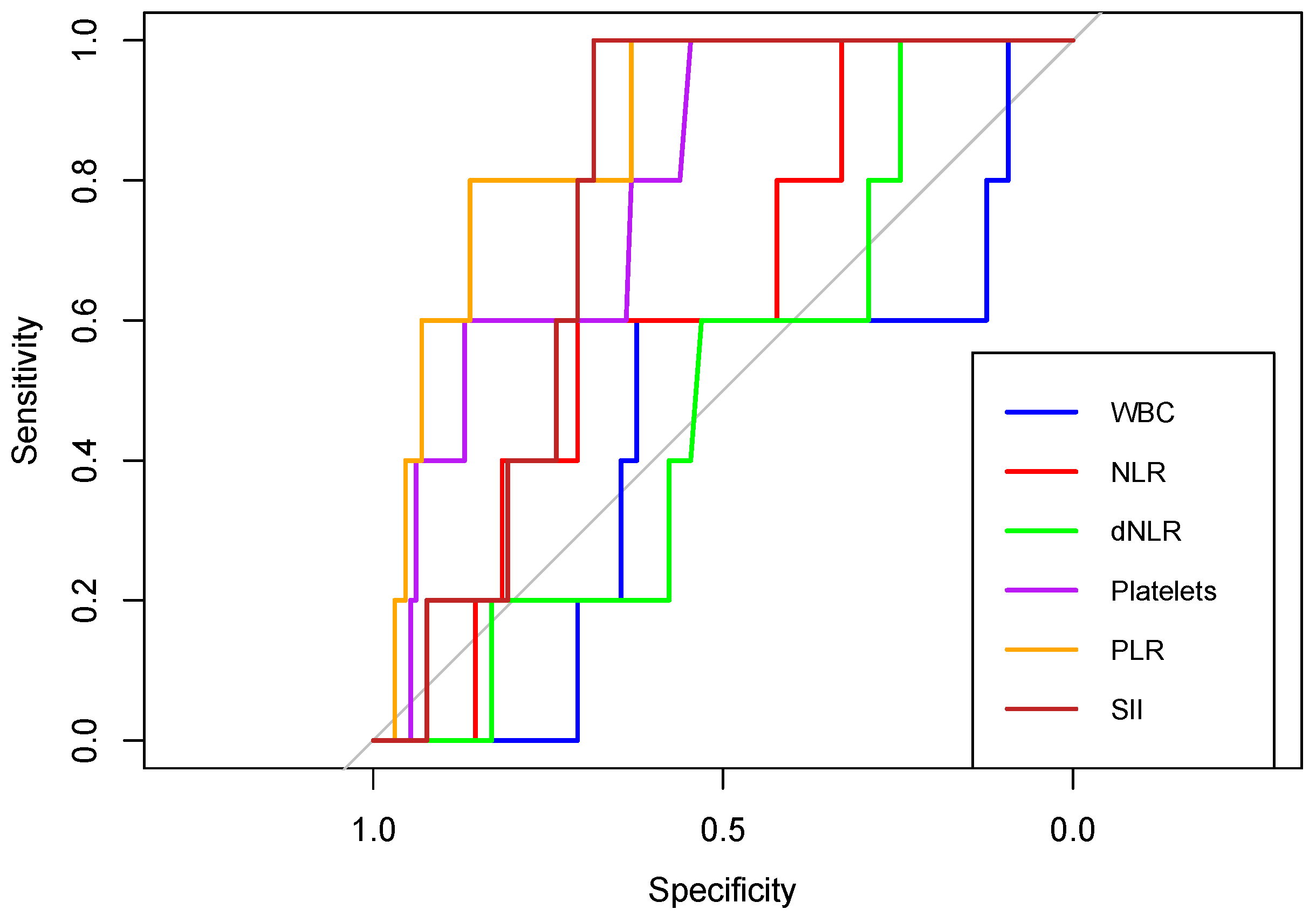

Furthermore, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of WBC, NLR, dNLR, Platelet, PLR, and SII were created to determine whether the baseline of these biomarkers was predictive of the occurrence of IVH, HN, EHIP, or NICU admission in newborns born to COVID-19 positive women during pregnancy.

First, in terms of predicting intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), the areas under the curve (AUC) of WBC, NLR, dNLR, Platelets, PLR and SII were above 0.6. (Figure 12). The highest discriminatory power had SII with an AUC of 0.686 (

Table 8).

Figure 12.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of WBC, NLR, dNLR, Platelets, PLR, and SII in predicting intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), in neonates born to COVID-19 positive women during pregnancy.

Figure 12.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of WBC, NLR, dNLR, Platelets, PLR, and SII in predicting intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), in neonates born to COVID-19 positive women during pregnancy.

Figure 12.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of WBC, NLR, dNLR, Platelets, PLR, and SII in predicting NICU admission, in neonates born to COVID-19 positive women during pregnancy.

Figure 12.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of WBC, NLR, dNLR, Platelets, PLR, and SII in predicting NICU admission, in neonates born to COVID-19 positive women during pregnancy.

In predicting NICU admissions, NLR, platelets, PLR and SII showed an AUC above 0.6. The highest discriminatory power had PLR with an AUC of 0.869 (

Table 9).

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised concerns about its potential impact on maternal and neonatal health. This study aimed to evaluate the inflammatory markers in newborns born to mothers with COVID-19. Understanding the impact of maternal COVID-19 infection on the fetal immune system and potential risks associated with this exposure is crucial for providing appropriate care for pregnant women and their newborns. Assessing these ratios in newborns born to mothers with COVID-19 can provide insights into the immune response of the fetus to the maternal infection and the potential risks associated with exposure to SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy.

One of the notable findings in this study is the positive correlation between GA at the time of birth and specific laboratory parameters in neonates, particularly in the Control Group (COVID-19 negative during pregnancy). WBC counts, neutrophil counts, and NLR were found to increase with increasing GA. These findings align with existing literature, which indicates a progressive rise in the mean white blood cell (WBC) count, increasing from 1,600/μL at the 15th week of gestation to 7,710/μL by the 30th week [

22]. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the neutrophil count tends to be notably low, exhibiting a gradual increment from the 20th to the 30th week of gestation [

22,

23]. Additionally, premature and small for gestational Age (SGA) infants exhibit significantly diminished white blood cell counts [

24].

Our study reveals that maternal COVID-19 infection during pregnancy has significant effects on neonatal laboratory parameters. Notably, WBC counts were elevated in neonates born to mothers who had COVID-19 during the first trimester. This finding suggests that the timing of maternal infection can influence neonatal immune responses, potentially leading to increased WBC counts in neonates exposed to the virus during early pregnancy.

In contrast, maternal infection during pregnancy led to diminished lymphocyte counts in neonates compared to those born to COVID-19-free mothers, irrespective of the trimester of infection.

Understanding the impact of maternal COVID-19 on neonatal laboratory parameters is essential for clinical practice. Elevated WBC counts and altered lymphocyte counts in neonates may have clinical implications, although the exact significance and potential long-term effects require further investigation.

Furthermore, our study provides essential insights into the relationship between neonatal immunoreactivity and various laboratory test results, while controlling for potential confounding factors such as gestational age at birth and the trimester of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy. The results indicate that, after adjusting for these factors, there is generally no statistically significant association between neonatal immunoreactivity and most of the laboratory test results in newborns. These results show that vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2, did not affect the inflammatory parameters of the newborn. These data are consistent with other studies showing that the majority of infants with vertically transmitted SARS-Cov-2 remain asymptomatic with good clinical outcomes [

25].

Furthermore, our study showed good predictive ability of inflammatory markers for the occurrence of IVH and admission to NICU among infants born to COVID-19 positive mothers during pregnancy. The literature shows that inflammatory markers have been proven to be powerful predictors of poor COVID-19 outcomes in the general population [

18,

26,

27,

28]. Regarding the involvement of inflammatory markers in neonatal care, several studies have shown the usefulness of using the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in predicting the progression of intracerebral hemorrhage [

29]. Also similar to our study, Tanacan A et al. showed the usefulness of using SII in predicting poor perinatal outcomes in women with COVID-19 [

30].

The study has several limitations. First, the study was conducted in a single centre. The sample size may not sufficiently represent all populations, which requires multi-centre, larger-scale investigations to draw more robust conclusions. Second, other variables, including maternal treatments, could exert a potential influence on neonatal outcomes and laboratory parameters. Future research should take these factors into account appropriately. In addition, the long-term implications of altered laboratory parameters in neonates exposed to maternal COVID-19 require further and sustained investigation.

The generalizability of our study results should be considered within the context of the study population and its limitations. While our findings provide valuable insights into the impact of maternal COVID-19 infection on neonatal inflammatory parameters, they may not be directly applicable to all populations, especially those with different demographics or healthcare settings. Therefore, the external validity of our results should be cautiously applied to broader populations, and further research should explore these relationships in diverse cohorts to enhance generalizability.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, maternal COVID-19 infection during pregnancy has a discernible impact on neonatal laboratory parameters, including WBC and lymphocyte counts, which may have clinical implications. While maternal COVID-19 infection can lead to altered laboratory parameters in neonates, neonatal immunoreactivity may not be a direct contributor to these changes. Therefore, healthcare providers should consider the multifactorial nature of neonatal outcomes when caring for newborns born to mothers with COVID-19.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, D-E.P. and M.B.; methodology, D-E.P. and C.C; software, E.R.B.; validation, E.R.B., C.C. and Z.L.P; formal analysis, E.R.B. and Z.L.P; investigation, C.P.; A-M.M and C.B resources, I.R.; A-M.M and M.A.D; data curation, M.A.D. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D-E.P.; I.R; and C.M; writing—review and editing, G.I.Z.; L.P. and M.B; visualization, G.I.Z.; supervision, L.P. and M.B;

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Commission Board at Première Hospital (No. 330/18.11.2021), and the Ethics Committee of Scientific Research at “Victor Babeș” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timișoara (No. 76/2020), approved date: 12 January 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Favre, G.; Pomar, L.; Musso, D.; Baud, D. 2019-nCoV Epidemic: What about Pregnancies? The Lancet 2020, 395, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, S.R.; Ho, A.; Pius, R.; Buchan, I.; Carson, G.; Drake, T.M.; Dunning, J.; Fairfield, C.J.; Gamble, C.; Green, C.A.; et al. Risk Stratification of Patients Admitted to Hospital with Covid-19 Using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: Development and Validation of the 4C Mortality Score. The BMJ 2020, 370, m3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, P.G.; Qin, L.; Puah, S.H. COVID -19 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome ( ARDS ): Clinical Features and Differences from Typical Pre- COVID-19 ARDS. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 213, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Luo, F.; Yu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, D.; Xu, D.; Gong, Q.; Liao, J.; Yang, H.; Hou, W.; Zhang, Y. Clinical Characteristics and Intrauterine Vertical Transmission Potential of COVID-19 Infection in Nine Pregnant Women: A Retrospective Review of Medical Records. The Lancet 2020, 395, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory Responses and Inflammation-Associated Diseases in Organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazersaheb, S.; Hosseiniyan Khatibi, S.M.; Hejazi, M.S.; Tarhriz, V.; Farjami, A.; Ghasemian Sorbeni, F.; Farahzadi, R.; Ghasemnejad, T. COVID-19 Infection: An Overview on Cytokine Storm and Related Interventions. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalagiri, R.; Carder, T.; Choudhury, S.; Vora, N.; Ballard, A.; Govande, V.; Drever, N.; Beeram, M.; Uddin, M. Inflammation in Complicated Pregnancy and Its Outcome. Am. J. Perinatol. 2016, 33, 1337–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauder, M.W.; Lee, S.E.; Schulze, K.J.; Christian, P.; Wu, L.S.F.; Khatry, S.K.; LeClerq, S.C.; Adhikari, R.K.; Groopman, J.D.; West, K.P. Inflammation throughout Pregnancy and Fetal Growth Restriction in Rural Nepal. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, e258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haedersdal, S.; Salvig, J.D.; Aabye, M.; Thorball, C.W.; Ruhwald, M.; Ladelund, S.; Eugen-Olsen, J.; Secher, N.J. Inflammatory Markers in the Second Trimester Prior to Clinical Onset of Preeclampsia, Intrauterine Growth Restriction, and Spontaneous Preterm Birth. Inflammation 2013, 36, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubaru, I.; Motoc, A.; Bratosin, F.; Rosca, O.; Folescu, R.; Moise, M.L.; Neagoe, O.; Citu, I.M.; Feciche, B.; Gorun, F.; Erdelean, D.; Ratiu, A.; Citu, C. Exploring Clinical and Biological Features of Premature Births among Pregnant Women with SARS-CoV-2 Infection during the Pregnancy Period. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buicu, A.-L.; Cernea, S.; Benedek, I.; Buicu, C.-F.; Benedek, T. Systemic Inflammation and COVID-19 Mortality in Patients with Major Noncommunicable Diseases: Chronic Coronary Syndromes, Diabetes and Obesity. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, S.-S.; Cambou, M.C.; Mok, T.; Fajardo, V.M.; Jung, K.L.; Fuller, T.; Chen, W.; Kerin, T.; Mei, J.; Bhattacharya, D.; Choi, Y.; Wu, X.; Xia, T.; Shin, W.-J.; Cranston, J.; Aldrovandi, G.; Tobin, N.; Contreras, D.; Ibarrondo, F.J.; Yang, O.; Yang, S.; Garner, O.; Cortado, R.; Bryson, Y.; Janzen, C.; Ghosh, S.; Devaskar, S.; Asilnejad, B.; Moreira, M.E.; Vasconcelos, Z.; Soni, P.R.; Gibson, L.C.; Brasil, P.; Comhair, S.A.A.; Arumugaswami, V.; Erzurum, S.C.; Rao, R.; Jung, J.U.; Nielsen-Saines, K. The Systemic Inflammatory Landscape of COVID-19 in Pregnancy: Extensive Serum Proteomic Profiling of Mother-Infant Dyads with in Utero SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, U.T.; Francisco, R.P.V.; Baptista, F.S.; Gibelli, M.A.B.C.; Ibidi, S.M.; Carvalho, W.B.D.; Paganoti, C.D.F.; Sabino, E.C.; Silva, L.C.D.O.D.; Jaenisch, T.; Mayaud, P.; Brizot, M.D.L. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes: An Open Prospective Study of Pregnant Women in Brazil. Clinics 2022, 77, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.Q.; Bilodeau-Bertrand, M.; Liu, S.; Auger, N. The Impact of COVID-19 on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. J. Assoc. Medicale Can. 2021, 193, E540–E548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Mei, H.; Zheng, T.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Buka, S.; Yao, X.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, A. Pregnant Women with COVID-19 and Risk of Adverse Birth Outcomes and Maternal-Fetal Vertical Transmission: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Wuhan, China. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albayrak, H. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Neutrophil-to-Monocyte Ratio, Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, and Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Psoriasis Patients: Response to Treatment with Biological Drugs. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citu, C.; Gorun, F.; Motoc, A.; Sas, I.; Gorun, O.M.; Burlea, B.; Tuta-Sas, I.; Tomescu, L.; Neamtu, R.; Malita, D.; Citu, I.M. The Predictive Role of NLR, d-NLR, MLR, and SIRI in COVID-19 Mortality. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misiewicz, A.; Dymicka-Piekarska, V. Fashionable, but What Is Their Real Clinical Usefulness? NLR, LMR, and PLR as a Promising Indicator in Colorectal Cancer Prognosis: A Systematic Review. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeb, A.; Khurshid, S.; Bano, S.; Rasheed, U.; Zammurrad, S.; Khan, M.S.; Aziz, W.; Tahir, S. The Role of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as Markers of Disease Activity in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Cureus 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.-J.; Du, Y.-P.; Feng, C.-X.; Wang, L.-Q.; Chen, M.-B. Prognostic Value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Gastric Cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e0144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proytcheva, M.A. Issues in Neonatal Cellular Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 131, 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forestier, F.; Daffos, F.; Catherine, N.; Renard, M.; Andreux, J.P. Developmental Hematopoiesis in Normal Human Fetal Blood. Blood 1991, 77, 2360–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, G.; Bauer, C.R.; Lorch, V.; Noto, T.; Cleveland, W.W. INFLUENCE OF GESTATIONAL AGE(GA) AND BIRTH WEIGHT (BW) ON THE WHITE BLOOD CELL COUNT (WBC) IN THE NEONATE. Pediatr. Res. 1974, 8, 405–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Fadila, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Prasad, A.; Akhtar, A.; Chaudhary, B.K.; Tiwari, L.K.; Chaudhry, N. Vertical Transmission and Clinical Outcome of the Neonates Born to SARS-CoV-2-Positive Mothers: A Tertiary Care Hospital-Based Observational Study. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e001193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fois, A.G.; Paliogiannis, P.; Scano, V.; Cau, S.; Babudieri, S.; Perra, R.; Ruzzittu, G.; Zinellu, E.; Pirina, P.; Carru, C.; Arru, L.B.; Fancellu, A.; Mondoni, M.; Mangoni, A.A.; Zinellu, A. The Systemic Inflammation Index on Admission Predicts In-Hospital Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. Molecules 2020, 25, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyit, M.; Avci, E.; Nar, R.; Senol, H.; Yilmaz, A.; Ozen, M.; Oskay, A.; Aybek, H. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio, Lymphocyte to Monocyte Ratio and Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio to Predict the Severity of COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 40, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.-P.; Liu, J.; Tao, W.; Li, H. The Diagnostic and Predictive Role of NLR, d-NLR and PLR in COVID-19 Patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Tang, Q.; Peng, M.; Zhao, W. Prognostic Role of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 825859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanacan, A.; Oluklu, D.; Laleli Koc, B.; Sinaci, S.; Menekse Beser, D.; Uyan Hendem, D.; Yildirim, M.; Sakcak, B.; Besimoglu, B.; Tugrul Ersak, D.; Akgun Aktas, B.; Gulen Yildiz, E.; Unlu, S.; Kara, O.; Alyamac Dizdar, E.; Canpolat, F.E.; Ates, İ.; Moraloglu Tekin, O.; Sahin, D. The Utility of Systemic Immune-inflammation Index and Systemic Immune-response Index in the Prediction of Adverse Outcomes in Pregnant Women with Coronavirus Disease 2019: Analysis of 2649 Cases. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Flow-Chart on the selection and division of participants into groups.

Figure 1.

Flow-Chart on the selection and division of participants into groups.

Figure 2.

Laboratory parameters according to the trimester of infection.: (a) Neonatal Platelets; (b) Neonatal PLR; c) Neonatal SII; d) Neonatal NLR; e) Neonatal WBC; f) Neonatal Neutrophils; g) Neonatal Lymphocytes.

Figure 2.

Laboratory parameters according to the trimester of infection.: (a) Neonatal Platelets; (b) Neonatal PLR; c) Neonatal SII; d) Neonatal NLR; e) Neonatal WBC; f) Neonatal Neutrophils; g) Neonatal Lymphocytes.

Figure 3.

Correlation analysis, according COVID-19 status during pregnancy, between gestational age at birth and: (a) Neonatal WBC; (b) Neonatal Neutrophils; c) Neonatal Lymphocytes; d) Neonatal NLR; e) Neonatal dNLR; f) Neonatal Platelets; g) Neonatal PLR, and h) Neonatal SII; Note: Group Cases= COVID-19 during pregnancy, Group Control= COVID-19- free during pregnancy.

Figure 3.

Correlation analysis, according COVID-19 status during pregnancy, between gestational age at birth and: (a) Neonatal WBC; (b) Neonatal Neutrophils; c) Neonatal Lymphocytes; d) Neonatal NLR; e) Neonatal dNLR; f) Neonatal Platelets; g) Neonatal PLR, and h) Neonatal SII; Note: Group Cases= COVID-19 during pregnancy, Group Control= COVID-19- free during pregnancy.

Figure 4.

Multivariate Regression Analysis of WBC Newborn, with GA and COVID-19 status during pregnancy. Note: COVID-19 positive during pregnancy= 0; COVID-19-free during pregnancy= 1.

Figure 4.

Multivariate Regression Analysis of WBC Newborn, with GA and COVID-19 status during pregnancy. Note: COVID-19 positive during pregnancy= 0; COVID-19-free during pregnancy= 1.

Figure 5.

Box-plots comparing the biomarker values according to maternal COVID status during pregnancy and pre-eclampsia condition. Note: Preeclampsia- No = Green plots; Preeclampsia-Yes= Yellow plots. * p-values are for case vs control comparison in women without pre-eclampsia.

Figure 5.

Box-plots comparing the biomarker values according to maternal COVID status during pregnancy and pre-eclampsia condition. Note: Preeclampsia- No = Green plots; Preeclampsia-Yes= Yellow plots. * p-values are for case vs control comparison in women without pre-eclampsia.

Figure 6.

Correlation matrix between date of maternal COVID-19 infection (in gestational weeks) and maternal and neonatal laboratory parameters.

Figure 6.

Correlation matrix between date of maternal COVID-19 infection (in gestational weeks) and maternal and neonatal laboratory parameters.

Figure 7.

Laboratory parameters among neonates born to mothers who had experienced COVID-19 during pregnancy, according to the immunoreactivity at the time of birth. (a) Neonatal Platelets; (b) Neonatal PLR; c) Neonatal SII; d) Neonatal NLR; e) Neonatal WBC; f) Neonatal Neutrophils; g) Neonatal Lymphocytes.

Figure 7.

Laboratory parameters among neonates born to mothers who had experienced COVID-19 during pregnancy, according to the immunoreactivity at the time of birth. (a) Neonatal Platelets; (b) Neonatal PLR; c) Neonatal SII; d) Neonatal NLR; e) Neonatal WBC; f) Neonatal Neutrophils; g) Neonatal Lymphocytes.

Figure 8.

Laboratory parameters among neonates born to mothers who had experienced COVID-19 during pregnancy, according to the presence of maternal symptoms during the disease: (a) Neonatal WBC; (b) Neonatal Neutrophils; (c) Neonatal Lymphocytes; (d) Neonatal NLR; (e) Neonatal dNLR; (f) Neonatal Platelets; (g) Neonatal PLR; h) Neonatal SII.

Figure 8.

Laboratory parameters among neonates born to mothers who had experienced COVID-19 during pregnancy, according to the presence of maternal symptoms during the disease: (a) Neonatal WBC; (b) Neonatal Neutrophils; (c) Neonatal Lymphocytes; (d) Neonatal NLR; (e) Neonatal dNLR; (f) Neonatal Platelets; (g) Neonatal PLR; h) Neonatal SII.

Figure 10.

Correlation between COVID-19 immunoreactivity of newborns and neonatal complications: (a) Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH); (b) Hydronephrosis (HN); (c) hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (EHIP); (d) the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

Figure 10.

Correlation between COVID-19 immunoreactivity of newborns and neonatal complications: (a) Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH); (b) Hydronephrosis (HN); (c) hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (EHIP); (d) the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

Figure 11.

Correlation between COVID-19 immunoreactivity of mother at birth and neonatal complications: (a) Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH); (b) Hydronephrosis (HN); (c) hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (EHIP); (d) the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

Figure 11.

Correlation between COVID-19 immunoreactivity of mother at birth and neonatal complications: (a) Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH); (b) Hydronephrosis (HN); (c) hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (EHIP); (d) the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 296 mothers and newborns included in the study.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 296 mothers and newborns included in the study.

| Parameters |

Overall

(n=296) |

COVID-19 during pregnancy- Group1

(n=135) |

Covid-19- free during pregnancy Group 2

(n= 161) |

p-value |

| Maternal Characteristics |

|

|

|

|

Age1

[median (IQR)] |

32 (6) |

32.0 (5.0) |

33.0 (6.0) |

0.51 |

Gestation1

[median (IQR)] |

1 (1) |

2.0 (1.0) |

1 (1) |

0.37 |

Parity1

[median (IQR)] |

1 (1) |

1.0 (1.0) |

1 (1) |

0.01 |

| GA at birth1

|

39 (1) |

39 (1) |

39 (1) |

0.26 |

| Infection date (gestational weeks)1

|

– |

23 (15) |

– |

- |

| Maternal Chronic Disease |

|

|

|

|

| Diabetes2

|

2 (0.67%) |

- |

2 (1.24%) |

0.05 |

| HTA2

|

2 (0.67%) |

- |

2 (1.24%) |

NA |

| Cardiovascular2

|

3 (1.01%) |

3 (2.22%) |

0 |

0.09 |

| Hepatitis2

|

5 (1.68%) |

2 (1.48%) |

3 (1.86%) |

1.00 |

| Thyroid_disease2

|

36 (12.16%) |

12 (8.88%) |

14 (14.90%) |

0.15 |

| C-sections2 |

210 (70.94%) |

103 (76.29%) |

107 (66.45) |

0.07 |

| Preterm birth2 |

14 (4.72%) |

6 (4.44%) |

8 (4.96%) |

1.0 |

| COVID-19 Symptoms |

|

|

|

|

| Respiratory |

– |

88 (29.72%) |

– |

– |

| Fever |

– |

37 (12.5%) |

– |

– |

| Anosmia |

– |

49 (16.55) |

– |

– |

| Newborns Characteristics |

|

|

|

|

| Weight1

|

3325.0 (515.0) |

3360.0 (535.0) |

3300.0 (480.0) |

0.23 |

| Height1

|

51 (1) |

51.0 (1.5) |

50.0 (1.0) |

0.17 |

| APGAR score1

|

9 (0) |

9 (0) |

9 (0) |

0.16 |

Table 2.

Laboratory parameters among 296 mothers and newborns included in the study.

Table 2.

Laboratory parameters among 296 mothers and newborns included in the study.

| Parameters |

Overall

(n=365) |

Cases Group

(n=167) |

Control Group

(n=200) |

p-value |

| Maternal Laboratory Data |

|

|

|

|

| WBC |

9.75 (3.08) |

9.63 (2.67) |

9.79 (3.34) |

0.94 |

| Neutrophils (%) |

69.8 (7.84) |

70.2 (6.90) |

69.2 (8.89) |

0.39 |

| Neutrophils (x109/L) |

6.80 (2.58) |

6.84 (2.41) |

6.73 (2.76) |

0.79 |

| Lymphocytes (%) |

21.0 (6.97) |

20.9 (5.5) |

21.3 (8.7) |

0.71 |

| Lymphocytes (x109/L) |

2.03 (0.76) |

2.01 (0.70) |

2.04 (0.81) |

0.84 |

| Platelets |

232.0 (73.5) |

235.0 (68.0) |

228.0 (80.25) |

0.05 |

| NLR |

3.32 (1.47) |

3.34 (1.23) |

3.27 (1.93) |

0.69 |

| dNLR |

2.31 (0.86) |

2.35 (0.77) |

2.24 (1.00) |

0.34 |

| PLR |

34.15 (14.30) |

34.77 (14.62) |

33.78 (14.10) |

0.21 |

| SII |

762.58 (469.72) |

788.09 (410.62) |

741.29 (513.44) |

0.23 |

| Neonates Laboratory Data |

|

|

|

|

| WBC |

19.78 (5.86) |

20.41 (5.77) |

19.26 (5.91) |

0.03* |

| Neutrophils (%) |

63.05 (10.34) |

63.5 (9.50) |

62.3 (10.30) |

0.26 |

| Neutrophils (x109/L) |

12.56 (5.34) |

12.88 (5.62) |

12.18 (4.92) |

0.03* |

| Lymphocytes (%) |

20.3 (7.52) |

20.3 (7.5) |

20.2 (7.80) |

0.26 |

| Lymphocytes (x109/L) |

3.99 (1.35) |

4.12 (1.46) |

3.76 (1.22) |

0.0001* |

| Platelets |

303.5 (74.25) |

303.0 (82.0) |

304.0 (66.0) |

0.96 |

| NLR |

3.12 (1.61) |

3.11 (1.54) |

3.13 (1.64) |

0.72 |

| dNLR |

1.70 (0.79) |

1.73 (0.75) |

1.65 (0.75) |

0.26 |

| PLR |

77.37 (29.31) |

73.29 (27.92) |

79.34 (25.81) |

0.0009* |

| CRP |

0.2 (0.4) |

0.2 (0.5) |

0.2 (0.4) |

0.28 |

| SII |

945.67 (542.38) |

959.09 (518.51) |

941.26 (574.39) |

0.75 |

Table 3.

Kruskal-Wallis Test between laboratory tests, according GA and groups.

Table 3.

Kruskal-Wallis Test between laboratory tests, according GA and groups.

| Variable |

Kruskal-Wallis H Statistic |

p-value |

| WBC newborn |

18.67 |

0.17 |

| Neutrophils newborn |

13.73 |

0.46 |

| Lymphocytes newborn |

24.51 |

0.03 |

| NLR newborn |

14.48 |

0.41 |

| dNLR newborn |

13.79 |

0.46 |

| Platelets newborn |

18.05 |

0.20 |

| PLR newborn |

26.90 |

0.01 |

| SII |

22.76 |

0.06 |

Table 4.

Multiple Linear Regression between laboratory tests, and GA and groups.

Table 4.

Multiple Linear Regression between laboratory tests, and GA and groups.

| Model |

Coefficients |

Std. error |

p-value |

95%CI |

| Variable |

Covariates |

|

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

| WBC newborn |

GA |

0.518 |

0.21 |

0.01 |

0.089 |

0.949 |

| |

Group |

-1.167 |

0.55 |

0.03 |

-2.260 |

-0.074 |

| Neutrophils newborn |

GA |

0.45 |

0.18 |

0.01 |

0.090 |

0.828 |

| |

Group |

-0.87 |

0.47 |

0.06 |

-1.812 |

0.061 |

| Lymphocytes newborn |

GA |

-0.026 |

0.04 |

0.56 |

-0.115 |

0.063 |

| |

Group |

-0.47 |

0.11 |

0.00 |

-0.705 |

-0.253 |

| NLR newborn |

GA |

0.135 |

0.06 |

0.02 |

0.017 |

0.255 |

| |

Group |

0.13 |

0.15 |

0.39 |

-0.172 |

0.432 |

| dNLR newborn |

GA |

0.055 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

0.001 |

0.110 |

| |

Group |

-0.055 |

0.07 |

0.43 |

-0.194 |

0.083 |

| Platelets newborn |

GA |

6.339 |

2.51 |

0.01 |

1.391 |

11.289 |

| |

Group |

1.30 |

6.38 |

0.83 |

-11.265 |

13.881 |

| PLR newborn |

GA |

1.652 |

1.06 |

0.12 |

-0.436 |

3.740 |

| |

Group |

8.59 |

2.69 |

0.002 |

3.287 |

13.899 |

| SII |

GA |

63.78 |

20.24 |

0.002 |

23.944 |

103.625 |

| |

Group |

40.20 |

51.42 |

0.43 |

-61.002 |

141.418 |

Table 5.

Multiple Linear Regression Coefficients for Neonatal Variables Based on Maternal COVID-19 status during pregnancy (Group) adjusted on Gestational Age (GA), and Preeclampsia presence.

Table 5.

Multiple Linear Regression Coefficients for Neonatal Variables Based on Maternal COVID-19 status during pregnancy (Group) adjusted on Gestational Age (GA), and Preeclampsia presence.

| Model * |

Coefficients |

Std. error |

p-value |

95%CI |

| Variable |

|

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

| WBC newborn |

-1.161 |

0.55 |

0.03 |

-2.256 |

-0.066 |

| Neutrophils newborn |

-0.869 |

0.47 |

0.06 |

-1.809 |

0.069 |

| Lymphocytes newborn |

-0.479 |

0.11 |

0.00 |

-0.705 |

-0.253 |

| NLR newborn |

0.131 |

0.15 |

0.39 |

-0.171 |

0.434 |

| dNLR newborn |

-0.054 |

0.07 |

0.43 |

-0.194 |

0.084 |

| Platelets newborn |

1.059 |

6.39 |

0.86 |

-11.523 |

13.641 |

| PLR newborn |

8.490 |

2.69 |

0.002 |

3.181 |

13.801 |

| SII |

39.720 |

51.54 |

0.44 |

-61.729 |

141.169 |

Table 6.

Multiple Linear Regression between laboratory tests and mother immunoreactivity adjusted on GA and trimester of infection.

Table 6.

Multiple Linear Regression between laboratory tests and mother immunoreactivity adjusted on GA and trimester of infection.

| Variables |

Coefficients |

Std. error |

p-value |

95%CI |

| |

|

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

| WBC newborn |

0.077 |

0.81 |

0.92 |

-1.542 |

1.698 |

| Neutrophils newborn |

0.495 |

0.69 |

0.47 |

-0.874 |

1.865 |

| Lymphocytes newborn |

-0.350 |

0.18 |

0.06 |

-0.723 |

0.023 |

| NLR newborn |

0.448 |

0.21 |

0.03 |

0.024 |

0.874 |

| dNLR newborn |

0.169 |

0.10 |

0.10 |

-0.037 |

0.376 |

| Platelets newborn |

-4.366 |

9.92 |

0.66 |

-24.007 |

15.274 |

| PLR newborn |

6.523 |

4.07 |

0.11 |

-1.534 |

14.582 |

| SII |

116.21 |

73.72 |

0.11 |

-29.620 |

262.05 |

Table 7.

ANOVA between laboratory tests and neonatal outcomes.

Table 7.

ANOVA between laboratory tests and neonatal outcomes.

| Variables |

IVH |

HN |

EHIP |

NICU |

| |

F |

p-value |

F |

p-value |

F |

p-value |

F |

p-value |

| WBC newborn |

1.98 |

0.11 |

0.31 |

0.90 |

2.35 |

0.04 |

0.32 |

0.57 |

| NLR newborn |

2.52 |

0.04 |

0.98 |

0.43 |

2.07 |

0.10 |

0.93 |

0.33 |

| dNLR newborn |

1.62 |

0.15 |

0.91 |

0.47 |

1.53 |

0.20 |

0.02 |

0.87 |

| Platelets newborn |

2.40 |

0.06 |

0.94 |

0.45 |

3.32 |

0.02 |

4.22 |

0.04 |

| PLR newborn |

1.62 |

0.16 |

1.48 |

0.19 |

1.71 |

0.16 |

6.11 |

0.01 |

| SII |

3.18 |

0.02 |

0.87 |

0.50 |

3.29 |

0.02 |

2.94 |

0.08 |

Table 8.

Prognostic accuracy of inflammatory markers in in predicting intraventricular hemorrhage.

Table 8.

Prognostic accuracy of inflammatory markers in in predicting intraventricular hemorrhage.

| Variables |

AUC |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

| WBC |

0.652 |

0.70 |

0.72 |

| NLR |

0.668 |

0.50 |

0.83 |

| dNLR |

0.646 |

0.75 |

0.66 |

| Platelets |

0.600 |

0.54 |

0.61 |

| PLR |

0.620 |

0.62 |

0.61 |

| SII |

0.686 |

0.70 |

0.52 |

Table 9.

Prognostic accuracy of inflammatory markers in in predicting NICU admission.

Table 9.

Prognostic accuracy of inflammatory markers in in predicting NICU admission.

| Variables |

AUC |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

| WBC |

0.562 |

0.60 |

0.48 |

| NLR |

0.628 |

0.60 |

0.64 |

| dNLR |

0.482 |

0.75 |

0.59 |

| Platelets |

0.793 |

0.80 |

0.63 |

| PLR |

0.869 |

0.80 |

0.79 |

| SII |

0.850 |

0.80 |

0.71 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).