Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- There is a statistically significant difference in the frequency of pathohistological changes in placental tissue in patients with confirmed SARS-COV2 infection during pregnancy compared to the control group.

- Vertical transmission of SARS CoV-2 from mother to fetus is possible.

- There is a statistically significant increase in maternal and umbilical cord blood biomarkers of oxidative stress in patients infected with SARS CoV-2 during pregnancy compared to the control group.

- There is a significantly elevated level of oxidative stress markers in patients with more pronounced pathohistological changes in placental tissue.

- There is a statistically significant difference in the neonatal outcome of newborns of mothers with COVID-19 compared to the control group.

- Certain clinical parameters such as gestational age, sex of the newborn, and maternal age significantly affect the level of oxidative stress markers in the newborn.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Concerns

2.2. Participants

2.3. Protocol of Study

2.4. Sampling and Collecting Data

2.5. Determination of Oxidative Stress Markers

2.5.1. Determination of TBARS

2.5.2. Nitrite Determination (NO2-)

2.5.3. Superoxide Anion Radical Determination (O2-)

2.5.4. Hydrogen Peroxide Determination (H2O2)

2.5.5. Catalase Activity Determination (CAT)

2.5.6. Superoxide Dismutase Activity Determination (SOD)

2.5.7. Reduced Glutathione Concentration Determination (GSH)

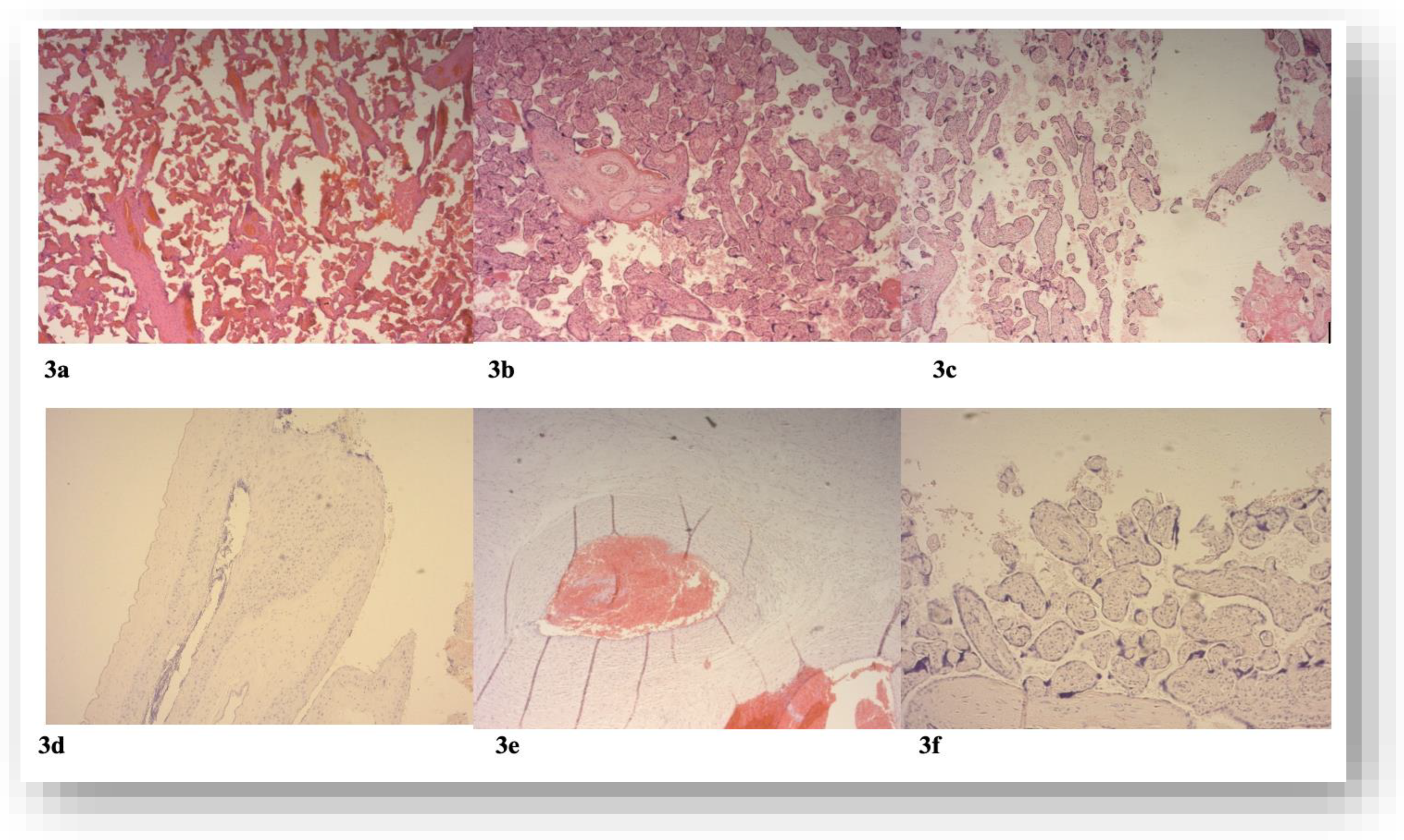

2.6. Pathohistological Analysis of Placental Tissue

2.6.1. Staining Hematoxylin-Eosin Technique

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Demographic and Anamnestic Data of Study Group

3.2. Characteristics of the Newborns at Delivery According to the Presence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Mothers

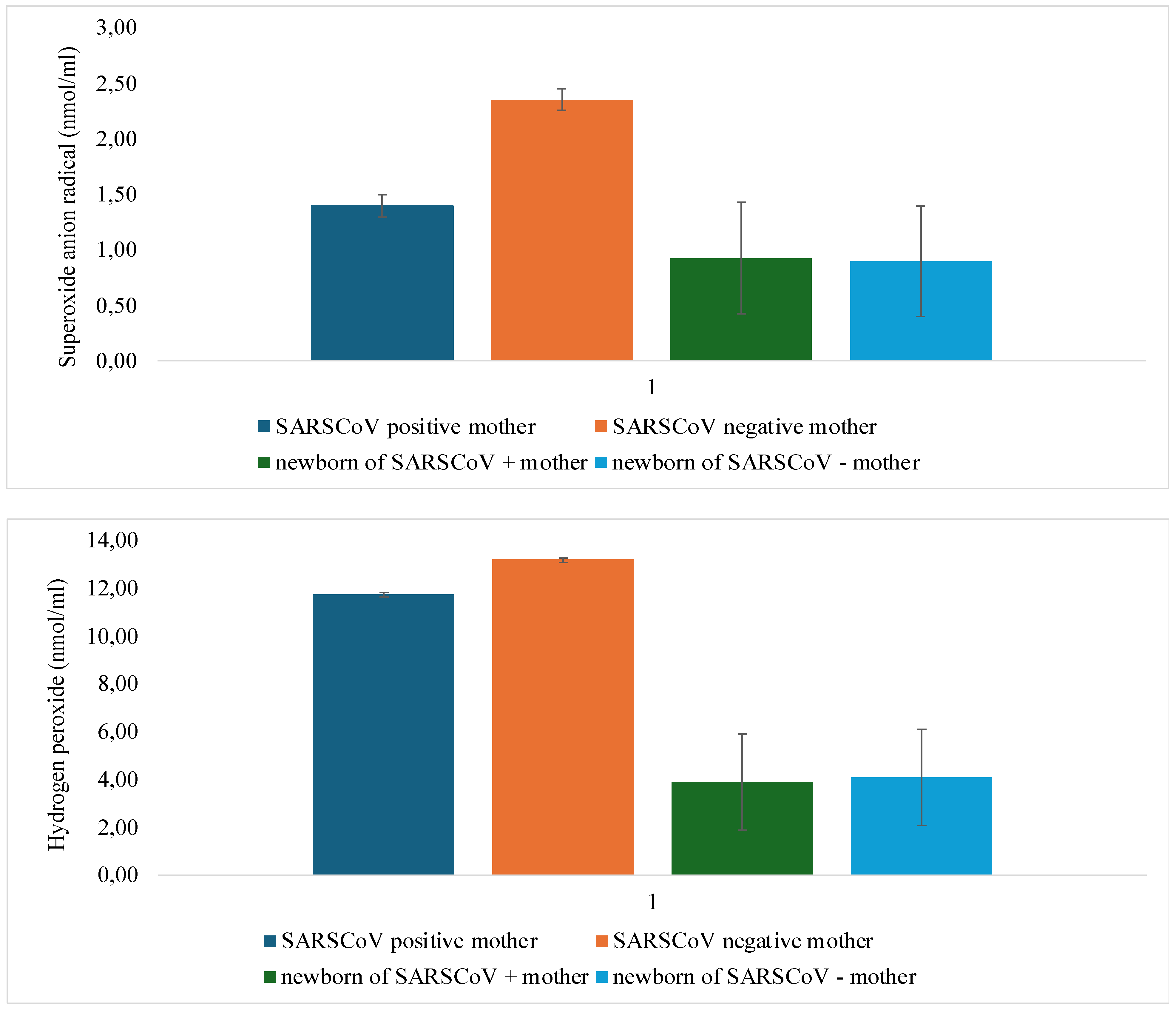

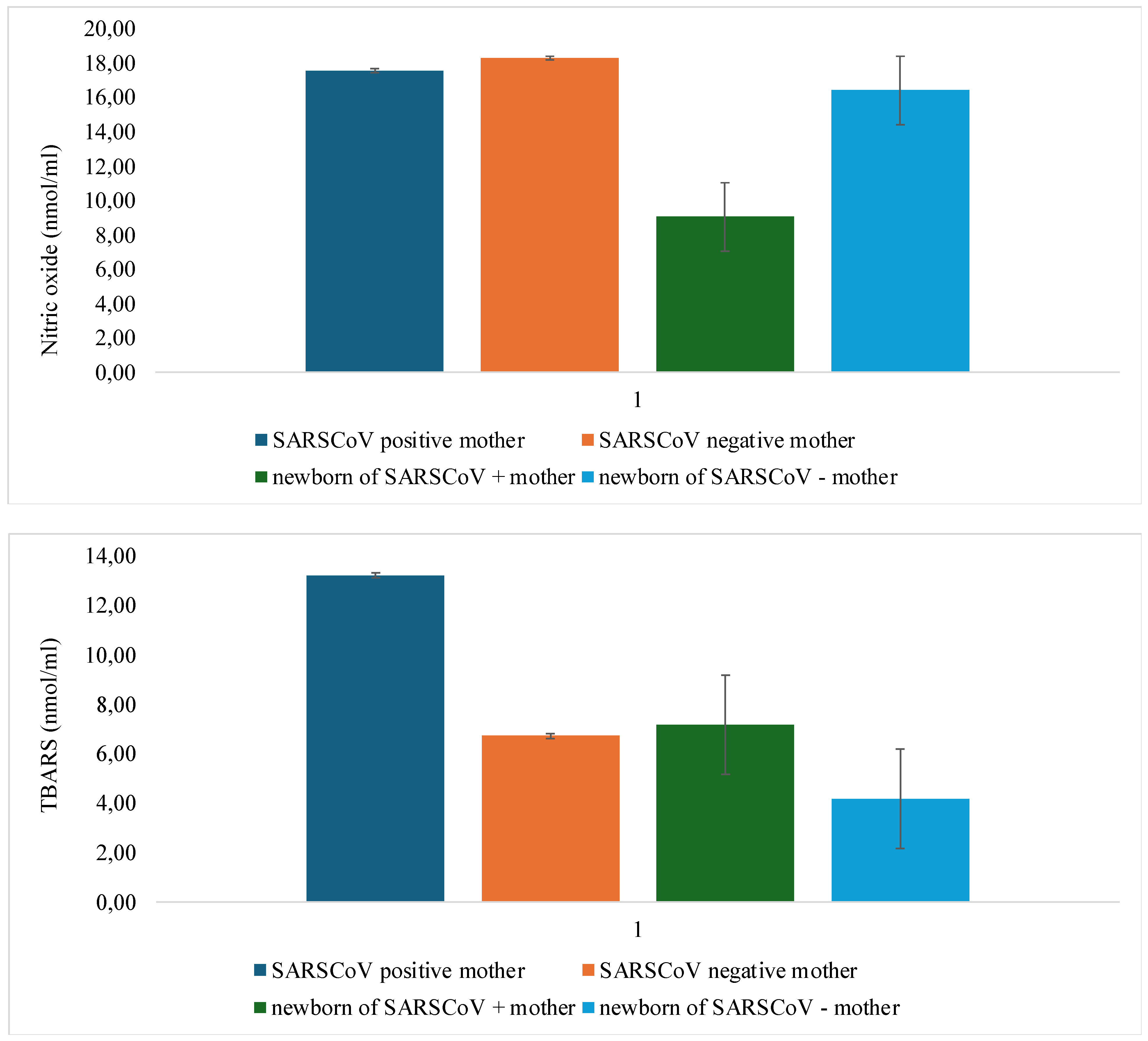

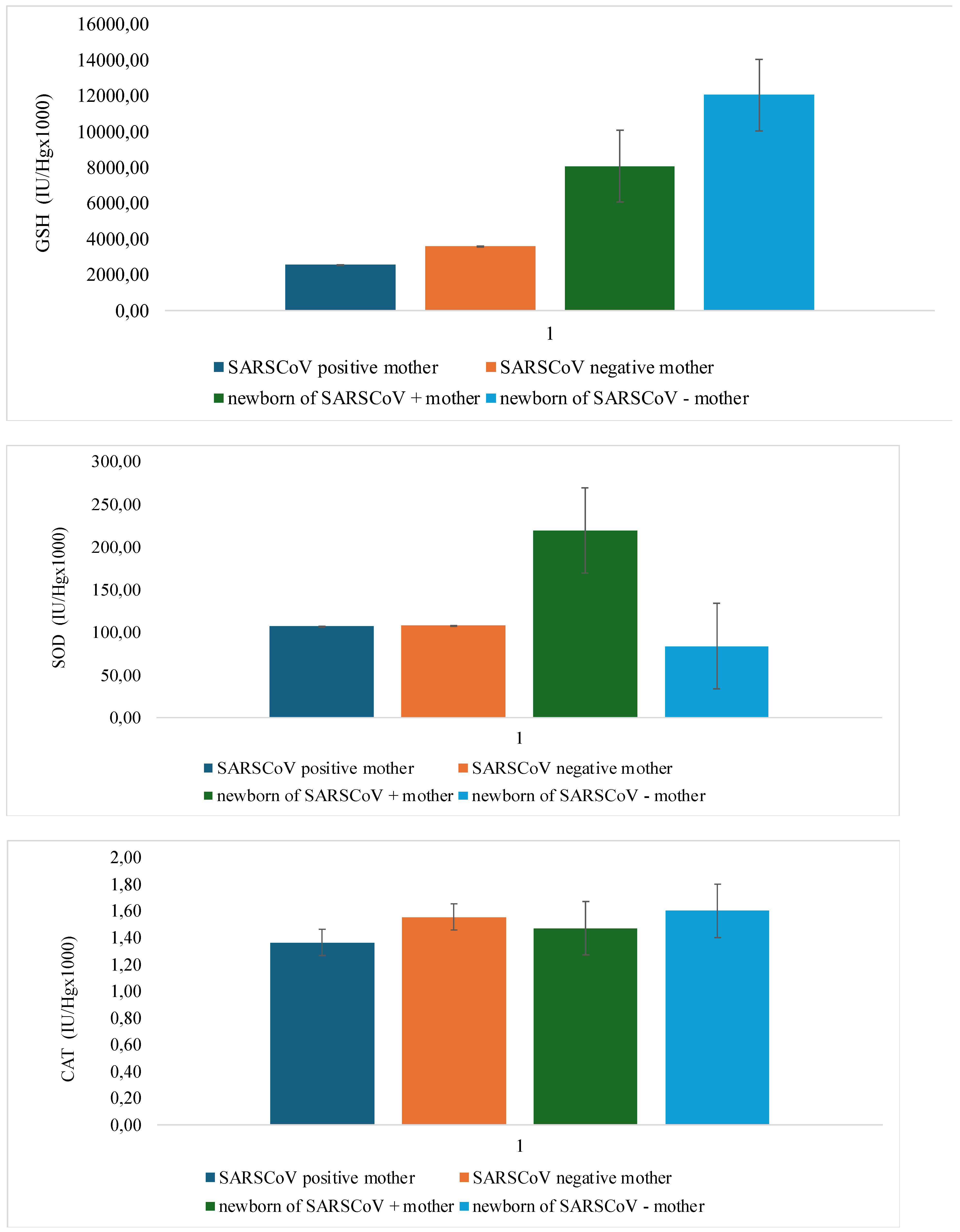

3.3. Analysis of the Oxidative Stress Levels According to the Presence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

3.4. The Histopathologic Lesions in the Placenta Concerning the Presence of SARS-COV2 Infection and the Timing of Infection

3.5. Neonatal Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019. |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| SARS-COV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| FVM | Fetal Vascular Malperfusion |

| MVM | Maternal Vascular Malperfusion |

| TMPRESS2 | Transmembrane serin proteases 2 |

| VTR | Venous Thrombosis |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RNS | Reactive Nitric Species |

| CRS | Chlorine Reactive Species |

| TAS | Total Antioxidative Status |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GPX | Glutathione peroxidase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| IUGR | Intrauterine Grow Restriction |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid Reactive Substances |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

References

- Zhu, Y.; Sharma, L.; Chang, D. Pathophysiology and clinical management of coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a mini-review. Front Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Number of COVID-19 cases reported to WHO (cumulative total) World. 2024.

- Macáková, K.; Pšenková, P.; Šupčíková, N.; Vlková, B.; Celec, P.; Záhumenský, J. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19 Vaccination on Oxidative Status of Human Placenta: A Preliminary Study. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDCWeekly, C. Protocol for Prevention and Control of COVID-19 (Edition 6). China CDC Wkly. 2020, 2, 321–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asselah, T.; Durantel, D.; Pasmant, E.; Lau, G.; Schinazi, R.F. COVID-19: Discovery, diagnostics and drug development. J Hepatol. 2021, 74, 168–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Nomura, N.; Muramoto, Y.; Ekimoto, T.; Uemura, T.; Liu, K.; et al. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 membrane protein essential for virus assembly. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.L.; Abiona, O.; et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, R.; Malhamé, I.; Teshler, L.; Acharya, G.; Hunt, B.J.; McLintock, C. A critical review of the pathophysiology of thrombotic complications and clinical practice recommendations for thromboprophylaxis in pregnant patients with COVID-19. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020, 99, 1110–20. Available online: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/aogs.13962. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardu, C.; Gambardella, J.; Morelli, M.B.; Wang, X.; Marfella, R.; Santulli, G. Hypertension, Thrombosis, Kidney Failure, and Diabetes: Is COVID-19 an Endothelial Disease? A Comprehensive Evaluation of Clinical and Basic Evidence. J Clin Med. 2020, 9, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zuo, W. Single-cell RNA expression profiling of ACE2, the putative receptor of Wuhan 2019-nCov. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.Y.; Redwood, S.; Prendergast, B.; Chen, M. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 1798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middeldorp, S.; Coppens, M.; van Haaps, T.F.; Foppen, M.; Vlaar, A.P.; Müller, M.C.A.; et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2020, 18, 1995–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranucci, M.; Ballotta, A.; Di Dedda, U.; Baryshnikova, E.; Dei Poli, M.; Resta, M.; et al. The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2020, 18, 1747–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, C.D.; Moore, H.B.; Yaffe, M.B.; Moore, E.E. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19: A comment. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2020, 18, 2060–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.J.H.A.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.A.M.P.J.; Kant, K.M.; et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020, 191, 145–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llitjos, J.; Leclerc, M.; Chochois, C.; Monsallier, J.; Ramakers, M.; Auvray, M.; et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2020, 18, 1743–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.F.W.; To, K.K.W.; Tse, H.; Jin, D.Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Interspecies transmission and emergence of novel viruses: lessons from bats and birds. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 544–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu, Z.Y.; Jiang MDi Xu, P.P.; Chen, W.; Ni, Q.Q.; Lu, G.M.; et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Perspective from China. Radiology 2020, 296, E15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bende, M.; Gredmark, T. Nasal Stuffiness During Pregnancy. Laryngoscope 1999, 109, 1108–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mor, G.; Cardenas, I.; Abrahams, V.; Guller, S. Inflammation and pregnancy: the role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011, 1221, 80–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L.L.; Zhao, S.J.; Kwak-Kim, J.; Mor, G.; Liao, A.H. Why are pregnant women susceptible to COVID-19? An immunological viewpoint. J Reprod Immunol. 2020, 139, 103122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahi, S.; Abdoli, A.; Kenarkoohi, A. Maternal COVID-19 infection and the fetus: Immunological and neurological perspectives. New Microbes New Infect. 2023, 53, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, P.; Douglas, J. Coagulation in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2010, 24, 339–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varlas, V.N.; Borș, R.G.; Plotogea, M.; Iordache, M.; Mehedințu, C.; Cîrstoiu, M.M. Thromboprophylaxis in Pregnant Women with COVID-19: An Unsolved Issue. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, F.; Armaganidis, A.; Orfanos, S.E. Immunothrombosis in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Cross Talks between Inflammation and Coagulation. Respiration 2017, 93, 212–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narang, K.; Enninga, E.A.L.; Gunaratne, M.D.S.K.; Ibirogba, E.R.; Trad, A.T.A.; Elrefaei, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19 During Pregnancy: A Multidisciplinary Review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020, 95, 1750–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu Rev Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 180–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: Concept and Some Practical Aspects. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitra, M.; Mathangi, D.C.; Priscilla, J. Oxidative stress during spontaneous vaginal delivery: comparison between maternal and neonatal oxidative status. International Journal of Medical Research and Review 2016, 4, 60–6. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, R.; Abad, C.; Rojas, D.; Chiarello, D.I.; Alejandro, T.G. Biomarkers of oxidative stress and reproductive complications. Adv Clin Chem. 2023, 113, 157–233. [Google Scholar]

- Simon-szabo, Z.; Fogarasi, E.; Nemes-Nagy, E.; Denes, L.; Croitoru, M.; Szabo, B. Oxidative stress and peripartum outcomes (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021, 22, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiselli, A.; Serafini, M.; Natella, F.; Scaccini, C. Total antioxidant capacity as a tool to assess redox status: critical view and experimental data. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000, 29, 1106–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, S.; Laschi, E.; Buonocore, G. Biomarkers of oxidative stress in the fetus and in the newborn. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019, 142, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogarasi, E.; Croitoru, M.D.; Fülöp, I.; Muntean, D.L. Is the Oxidative Stress Really a Disease? Acta Med Marisiensis 2016, 62, 112–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Khoo, M.I.; Ismail, E.H.E.; Hussain, N.H.N.; Zin, A.A.M.; Noordin, L.; et al. Oxidative stress biomarkers in pregnancy: a systematic review. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2024, 22, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K.J.A. Adaptive homeostasis. Mol Aspects Med. 2016, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Jauniaux, E. Oxidative stress. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011, 25, 287–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, F.J.; Vera, J.; Venegas, C.; Pino, F.; Lagunas, C. Circadian System and Melatonin Hormone: Risk Factors for Complications during Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, J.; Sun, X.; Dey, S.K. Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat Med. 2012, 18, 1754–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín, R.; Pujol, F.H.; Rojas, D.; Sobrevia, L. SARS- CoV-2 infection and oxidative stress in early-onset preeclampsia. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterhans, E. Sendai virus stimulates chemiluminescence in mouse spleen cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979, 91, 383–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.J.; Post, M.D. The placenta in pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. J Clin Pathol. 2008, 61, 1254–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, T.Y.; Mooney, E.E.; Ariel, I.; Balmus, N.C.M.; Boyd, T.K.; Brundler, M.A.; et al. Sampling and Definitions of Placental Lesions: Amsterdam Placental Workshop Group Consensus Statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016, 140, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, L.M. Maternal vascular malperfusion of the placental bed. APMIS 2018, 126, 551–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharps, M.C.; Hayes, D.J.L.; Lee, S.; Zou, Z.; Brady, C.A.; Almoghrabi, Y.; et al. A structured review of placental morphology and histopathological lesions associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Placenta 2020, 101, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, L.M. Maternal vascular malperfusion of the placental bed. APMIS 2018, 126, 551–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharps, M.C.; Hayes, D.J.L.; Lee, S.; Zou, Z.; Brady, C.A.; Almoghrabi, Y.; et al. A structured review of placental morphology and histopathological lesions associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Placenta 2020, 101, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, T.Y.; Mooney, E.E.; Ariel, I.; Balmus, N.C.M.; Boyd, T.K.; Brundler, M.A.; et al. Sampling and Definitions of Placental Lesions: Amsterdam Placental Workshop Group Consensus Statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016, 140, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lista, G.; Castoldi, F.; Compagnoni, G.; Maggioni, C.; Cornélissen, G.; Halberg, F. Neonatal and maternal concentrations of hydroxil radical and total antioxidant system: protective role of placenta against fetal oxidative stress. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2010, 31, 319–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, K.M.; Heerema-McKenney, A. Fetal Thrombotic Vasculopathy. American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2015, 39, 274–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redline, R.W. Clinical and pathological umbilical cord abnormalities in fetal thrombotic vasculopathy. Hum Pathol. 2004, 35, 1494–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redline, R.W.; Ariel, I.; Baergen, R.N.; deSa, D.J.; Kraus, F.T.; Roberts, D.J.; et al. Fetal Vascular Obstructive Lesions: Nosology and Reproducibility of Placental Reaction Patterns. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology 2004, 7, 443–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arts, N.; Schiffer, V.; Severens-Rijvers, C.; Bons, J.; Spaanderman, M.; Al-Nasiry, S. Cumulative effect of maternal vascular malperfusion types in the placenta on adverse pregnancy outcomes. Placenta 2022, 129, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, E.; Audette, M.C.; Ye, X.Y.; Keating, S.; Hoffman, B.; Lye, S.J.; et al. Maternal Vascular Malperfusion and Adverse Perinatal Outcomes in Low-Risk Nulliparous Women. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2017, 130, 1112–20. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, W.T.; Catov, J.M. The Placenta as a Window to Maternal Vascular Health. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2020, 47, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zur, R.L.; Kingdom, J.C.; Parks, W.T.; Hobson, S.R. The Placental Basis of Fetal Growth Restriction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2020, 47, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordijn, S.J.; Beune, I.M.; Thilaganathan, B.; Papageorghiou, A.; Baschat, A.A.; Baker, P.N.; et al. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: a Delphi procedure. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2016, 48, 333–9. [Google Scholar]

- Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; Pérez-Morente, M.A.; Hueso-Montoro, C.; Álvarez-Serrano, M.A.; de la Torre-Luque, A. Congenital, Intrapartum and Postnatal Maternal-Fetal-Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 Infections: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynn, S.M.; Yang, Y.J.; Thomas, C.; Friedlander, R.L.; Cagino, K.A.; Matthews, K.C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 and Placental Pathology. American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2022, 46, 51–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heider, A. Fetal Vascular Malperfusion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017, 141, 1484–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfo, A.; Cosma, S.; Nuzzo, A.M.; Salio, C.; Moretti, L.; Sassoè-Pognetto, M.; et al. Increased Placental Anti-Oxidant Response in Asymptomatic and Symptomatic COVID-19 Third-Trimester Pregnancies. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoots, M.H.; Gordijn, S.J.; Scherjon, S.A.; van Goor, H.; Hillebrands, J.L. Oxidative stress in placental pathology. Placenta 2018, 69, 153–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Thomas, K.M. Characterizing COVID-19 maternal-fetal transmission and placental infection using comprehensive molecular pathology. EBioMedicine 2020, 60, 102983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, L.C.; Wagner, D.A.; Glogowski, J.; Skipper, P.L.; Wishnok, J.S.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982, 126, 131–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook Methods For Oxygen Radical Research; CRC Press, 2018.

- Pick, E.; Keisari, Y. A simple colorimetric method for the measurement of hydrogen peroxide produced by cells in culture. J Immunol Methods 1980, 38, 161–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. [13] Catalase in vitro. Methods in Enzymology 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler, E. Red Blood Cell Metabolism, A Manual of Biochemical Methods. In Red Blood Cell Metabolism: A Manual of Biochemical Methods, 2nd ed.; Bergmeyen, H.V., Ed.; Grune and Stratton: New York, 1975; pp. 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler, E. Red Cell Metabolism: A Manual of Biochemical Methods, 3rd ed.; Beutler, E., Ed.; Grune and Stratton: New York, 1982; 105p. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, A.H.; Jacobson, K.A.; Rose, J.; Zeller, R. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining of Tissue and Cell Sections. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2008, 2008, pdb.prot4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, M.; Bunch, K.; Vousden, N.; Morris, E.; Simpson, N.; Gale, C.; et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: national population based cohort study. BMJ 2020, 369, m2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Zheng, D.; Jiang, H.; Wei, Y.; Zou, L.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Pregnant Women with Covid-19 in Wuhan, China. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, M.; Cagino, K.; Matthews, K.; Friedlander, R.; Glynn, S.; Kubiak, J.; et al. Pregnancy and postpartum outcomes in a universally tested population for SARS-CoV-2 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2020, 127, 1548–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaxi, P.; Maniatelli, E.; Vivilaki, V. Evaluation of mode of delivery in pregnant women infected with COVID-19. Eur J Midwifery 2020, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, D.; Lan, W. Clinical and CT imaging features of the COVID-19 pneumonia: Focus on pregnant women and children. Journal of Infection 2020, 80, e7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Luo, F.; Yu, X.; Zhang, W.; et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. The Lancet 2020, 395, 809–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, M.; Perreand, E.; Mangione, M.; Patel, M.; Cojocaru, L.; Seung, H.; et al. Mode of Delivery in Patients with COVID-19. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022, 226, S582–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Chiu, N.C.; Tai, Y.L.; Chang, H.Y.; Lin, C.H.; Sung, Y.H.; et al. Clinical features of neonates born to mothers with coronavirus disease-2019: A systematic review of 105 neonates. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 2021, 54, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azinheira Nobrega Cruz, N.; Stoll, D.; Casarini, D.E.; Bertagnolli, M. Role of ACE2 in pregnancy and potential implications for COVID-19 susceptibility. Clin Sci. 2021, 135, 1805–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.A.; Keith, M.; Pace, R.M.; Williams, J.E.; Ley, S.H.; Barbosa-Leiker, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 specific antibody trajectories in mothers and infants over two months following maternal infection. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flannery, D.D.; Gouma, S.; Dhudasia, M.B.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Pfeifer, M.R.; Woodford, E.C.; et al. Assessment of Maternal and Neonatal Cord Blood SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies and Placental Transfer Ratios. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Morotti, D.; Beigi, B.; Moshfegh, F.; Zafaranloo, N.; Patanè, L. Confirming Vertical Fetal Infection With Coronavirus Disease 2019: Neonatal and Pathology Criteria for Early Onset and Transplacental Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Infected Pregnant Mothers. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020, 144, 1451–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamouroux, A.; Attie-Bitach, T.; Martinovic, J.; Leruez-Ville, M.; Ville, Y. Evidence for and against vertical transmission for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020, 223, 91.e1–91e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camini, F.C.; da Silva Caetano, C.C.; Almeida, L.T.; de Brito Magalhães, C.L. Implications of oxidative stress on viral pathogenesis. Arch Virol. 2017, 162, 907–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broz, P.; Monack, D.M. Molecular mechanisms of inflammasome activation during microbial infections. Immunol Rev. 2011, 243, 174–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshi, M.L.; Su, Y.C.; Hong, J.R. RNA Viruses: ROS-Mediated Cell Death. Int J Cell Biol. 2014, 2014, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, K.B. Oxidative stress during viral infection: A review. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996, 21, 641–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdon, R.H. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in relation to mammalian cell proliferation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995, 18, 775–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, N.; Dhingra, R.; Arya, D.S.; Kalaivani, M.; Bhatla, N.; Kumar, R. Role of oxidative stress markers and antioxidants in the placenta of preeclamptic patients. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2010, 36, 1189–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holwerda, K.M.; Faas, M.M.; van Goor, H.; Lely, A.T. Gasotransmitters. Hypertension 2013, 62, 653–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hracsko, Z.; Safar, Z.; Orvos, H.; Novak, Z.; Pal, A.; Varga, I.S. Evaluation of oxidative stress markers after vaginal delivery or Caesarean section. In Vivo 2007, 21, 703–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chiba, T.; Omori, A.; Takahashi, K.; Tanaka, K.; Kudo, K.; Manabe, M.; et al. Correlations between the detection of stress-associated hormone/oxidative stress markers in umbilical cord blood and the physical condition of the mother and neonate. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2010, 36, 958–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaçor, T.; Sak, S.; Başaranoğlu, S.; Peker, N.; Ağaçayak, E.; Sak, M.E.; et al. Assessment of oxidative stress markers in cord blood of newborns to patients with oxytocin-induced labor. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2017, 43, 860–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, G.J.; Hempstock, J.; Jauniaux, E. Oxygen, early embryonic metabolism and free radical-mediated embryopathies. Reprod Biomed Online 2003, 6, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauniaux, E.; Hempstock, J.; Greenwold, N.; Burton, G.J. Trophoblastic Oxidative Stress in Relation to Temporal and Regional Differences in Maternal Placental Blood Flow in Normal and Abnormal Early Pregnancies. Am J Pathol. 2003, 162, 115–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauniaux, E.; Zaidi, J.; Jurkovic, D.; Campbell, S.; Hustin, J. Pregnancy: Comparison of colour Doppler features and pathological findings in complicated early pregnancy. Human Reproduction 1994, 9, 2432–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauniaux, E.; Watson, A.L.; Hempstock, J.; Bao, Y.P.; Skepper, J.N.; Burton, G.J. Onset of Maternal Arterial Blood Flow and Placental Oxidative Stress: A Possible Factor in Human Early Pregnancy Failure. Am J Pathol. 2000, 157, 2111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Hempstock, J.; Jauniaux, E. Oxygen, early embryonic metabolism and free radical-mediated embryopathies. Reprod Biomed Online 2003, 6, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogel, I.; Pinchuk, I.; Kupferminc, M.J.; Lichtenberg, D.; Fainaru, O. Oxidative stress in the fetal circulation does not depend on mode of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005, 193, 241–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.L.; Skepper, J.N.; Jauniaux, E.; Burton, G.J. Changes in concentration, localization and activity of catalase within the human placenta during early gestation. Placenta 1998, 19, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, T.H.; Skepper, J.N.; Burton, G.J. In Vitro Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Term Human Placenta as a Model for Oxidative Stress in Pathological Pregnancies. Am J Pathol. 2001, 159, 1031–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvey, J.J.; Magro, C.M.; Ma, L.X.; Nuovo, G.J.; Baergen, R.N. Analysis of complement deposition and viral RNA in placentas of COVID-19 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2020, 46, 151530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patberg, E.T.; Adams, T.; Rekawek, P.; Vahanian, S.A.; Akerman, M.; Hernandez, A.; et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection and placental histopathology in women delivering at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021, 224, 382.e1–382e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanes, E.D.; Mithal, L.B.; Otero, S.; Azad, H.A.; Miller, E.S.; Goldstein, J.A. Placental Pathology in COVID-19. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020, 154, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, A.L.; Guan, M.; Johannesen, E.; Stephens, A.J.; Khaleel, N.; Kagan, N.; et al. Placental SARS-CoV-2 in a pregnant woman with mild COVID-19 disease. J Med Virol. 2021, 93, 1038–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhren, J.T.; Meinardus, A.; Hussein, K.; Schaumann, N. Meta-analysis on COVID-19-pregnancy-related placental pathologies shows no specific pattern. Placenta 2022, 117, 72–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitan, D.; London, V.; McLaren, R.A.; Mann, J.D.; Cheng, K.; Silver, M.; et al. Histologic and Immunohistochemical Evaluation of 65 Placentas From Women With Polymerase Chain Reaction–Proven Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021, 145, 648–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rawaf, S.A.; Mousa, E.T.; Kareem, N.M. Correlation between Pregnancy Outcome and Placental Pathology in COVID-19 Pregnant Women. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2022, 2022, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, A.C.M.; Avvad-Portari, E.; Meuser-Batista, M.; Conde, T.C.; de Sá, R.A.M.; Salomao, N.; et al. Histopathological and clinical analysis of COVID-19-infected placentas. Surgical and Experimental Pathology 2024, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baergen, R.N.; Heller, D.S. Placental Pathology in Covid-19 Positive Mothers: Preliminary Findings. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology 2020, 23, 177–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosier, H.; Farhadian, S.F.; Morotti, R.A.; Deshmukh, U.; Lu-Culligan, A.; Campbell, K.H.; et al. SARS–CoV-2 infection of the placenta. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2020, 130, 4947–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smithgall, M.C.; Liu-Jarin, X.; Hamele-Bena, D.; Cimic, A.; Mourad, M.; Debelenko, L.; et al. Third-trimester placentas of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-positive women: histomorphology, including viral immunohistochemistry and in-situ hybridization. Histopathology 2020, 77, 994–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbetta-Rastelli, C.M.; Altendahl, M.; Gasper, C.; Goldstein, J.D.; Afshar, Y.; Gaw, S.L. Analysis of placental pathology after COVID-19 by timing and severity of infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023, 5, 100981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaumann, N.; Suhren, J.T. An Update on COVID-19-Associated Placental Pathologies. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2024, 228, 42–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulersen, M.; Prasannan, L.; Tam Tam, H.; Metz, C.N.; Rochelson, B.; Meirowitz, N.; et al. Histopathologic evaluation of placentas after diagnosis of maternal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020, 2, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, G. Article Review on Histopathologic Features of Placenta and Adverse Outcome in Pregnant Women with COVID-19 Positive. Pathology and Laboratory Medicine 2023, 7, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Gestational week at delivery | APGAR Score 1’ | APGAR Score 5’ | Baby Body Weight (g) | Baby Body length (cm) | Head circumference (cm) | IgM antibody (g/L) | Placenta weight (g) | |

| SARS-CoV-2+ | Mean | 39.19 | 8.96 | 9.10 | 3359.17 | 48.75 | 34.38 | 3.42 | 608.26 |

| SD | 0.98 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 491.69 | 2.25 | 1.58 | 3.25 | 129.81 | |

| SARS-CoV-2- | Mean | 39.42 | 9.23 | 9.19 | 3534.09 | 50.27 | 35.23 | 0.30 | 577.37 |

| SD | 1.26 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 404.35 | 2.12 | 1.38 | 0.27 | 143.37 | |

| P value | p=0.676 | p=0.556 | p=0.780 | p=0.465 | p=0.681 | p=0.899 | p=0.000* | p=0.322 | |

| Comparison | Mothers | Newborns |

|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV2+ vs. SARS CoV2 - | SARS-CoV2+ vs. SARS CoV2 - | |

| O2- | p=0.002* | p=0.113 |

| H2O2 | p=0.012 | p=0.043 |

| NO- | p=0.509 | p=0.003* |

| TBARS | p=0.001* | p=0.004* |

| GSH | p=0.322 | p=0.001* |

| SOD | p=0.488 | p=0.002* |

| CAT | p=0.566 | p=0.623 |

| Placental characteristics | Thrombosis | Avascular villi | Deposits of fibrines | Villous stromal vascular karyorrhexis | Obliteration of blood vessels | Vascular ectasia | Delayed villous maturation | placental infarction | retroplacental hemorrhage | Hypoplasia of distal villus | Accelerated villous maturation | Decidual arteriopathy | inflammatory changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 participants | + [6/28] [21.4%] |

++ [9/28] [32.1%] |

+ [1/28] [3.57%] |

- [0/28] [0%] |

+++ [12/28] [42.8%] |

++ [8/28] [28.5%] |

- [0/28] [0%] |

+ [3/28] [10.7%] |

++ [7/28] [25%] |

+ [2/28 [7.14%] |

++ [8/28] [28.5%] |

- [0/28] [0%] |

+ [4/28] [14.3%] |

| Non-COVID-19 participants | + [1/22] [4.54%] |

+ [1/22] [4.54%] |

- [0/22] [0%] |

- [0/22] [0%] |

+ [1/22] [4.54%] |

- [0/22] [0%] |

+ [1/22] [4.54%] |

- [0/22] [0%] |

- [0/22] [0%] |

- [0/22] [0%] |

++ [4/22] [18.1%] |

- [0/22] [0%] |

- [0/22] [0%] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).