1. Introduction

Computational imaging (CI) is a rapidly evolving field of research with incredible capabilities [

1]. Coded aperture imaging is one of the oldest sub-fields of CI developed to overcome the challenges associated with manufacturing lenses for non-visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum such as X-rays and Gamma rays [

2,

3,

4]. In CAI, the light from an object is modulated by a coded mask (CM) and the response to object intensity (

IROI) is recorded by an image sensor. Like any imaging system, CAI involves a calibration step where the point spread function (

IPSF) is recorded using the CM. The image of the object is reconstructed by processing

IPSF with

IROI using a computational reconstruction algorithm. While without a doubt CAI enabled imaging for extreme wavelengths without a lens, the quality of images obtained from CAI after the above-described multiple steps did not reach the level of that obtained from a lens. Therefore, CAI evolved over the years with developments in two directions namely towards an advanced CM and computational algorithm. Some notable inventions along the direction of CM are the developments of the Fresnel zone aperture [

5], uniformly redundant array mask [

6], modified uniformly redundant array mask [

7], and scattering mask [

8]. Similarly, many developments in computational reconstruction methods such as phase-only filter [

9], Weiner deconvolution (WD) [

10], and Lucy-Richardson algorithm were developed [

11,

12].

In 2017, interferenceless coded aperture correlation holography (I-COACH) was developed which extended CAI to 3D imaging along three spatial dimensions [

13]. It must be noted that CAI along 3D (2D space and spectrum) was achieved much earlier [

14]. When I-COACH was developed using a quasi-random phase mask, it was found that the existing computational reconstruction methods did not support an image reconstruction with a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). This led to the development of numerous computational reconstruction methods such as non-linear reconstruction (NLR) [

15], Lucy-Richardson-Rosen algorithm (LRRA) [

16], and incoherent non-linear deconvolution with an iterative algorithm (INDIA) [

17].

The development of I-COACH had a significant impact on the field of imaging and holography [

2]. I-COACH was able to achieve imaging capabilities that were believed to be impossible in imaging technology. Some key developments include, the development of a 4D imaging capability along 3D space and spectrum using a monochrome camera [

18], extending the field-of-view beyond the limits of the image sensor [

19], synthetic aperture imaging system which requires scanning only along the periphery with a scanning ratio < 0.01 (scanning ratio = Scanned area/total area) [

20] and imaging resolution enhancement [

21,

22]. Recently, a new problem ‘tuning axial resolution independent of lateral resolution’ has been addressed extensively using I-COACH techniques [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In 2024, the above problem has been solved creatively with capabilities to tune axial and spectral resolutions post-recording [

27,

28]. However, the above methods require multiple camera shots.

In this tutorial, we introduce a simple yet valuable technique called spatial ensemble mapping (SEM) where an ensemble of diverse diffraction patterns is mapped to different radii of the area of the image sensor. Therefore, different areas of the image sensor have different axial correlation lengths affecting the respective resolutions along the longitudinal space. But the lateral resolution remains the same as the numerical aperture (NA) which controls the lateral correlation lengths remains the same yielding lateral resolution independent of the area selection in the image sensor. Therefore, the developed approach allows tuning the axial resolution post-recording from a single camera recording without affecting the lateral resolution. Besides, this approach creates a new interdependency between the field of the image sensor to the axial resolution which does not exist in conventional imaging as well as CAI. Both direct as well as inverse relations between the area of the sensor and axial resolution can be obtained. While we demonstrate the SEM concept for only axial resolution, the developed method can be used to tune other imaging characteristics such as spectral resolution, lateral resolution, and 3D image location.

The manuscript consists of six sections. The methodology is presented in the next section. In the third section, presents the simulation studies. The experimental studies are presented in the fourth section. The results are discussed in the fifth section. The conclusion and future perspectives of the study are presented in the final section of the manuscript.

2. Materials and Methods

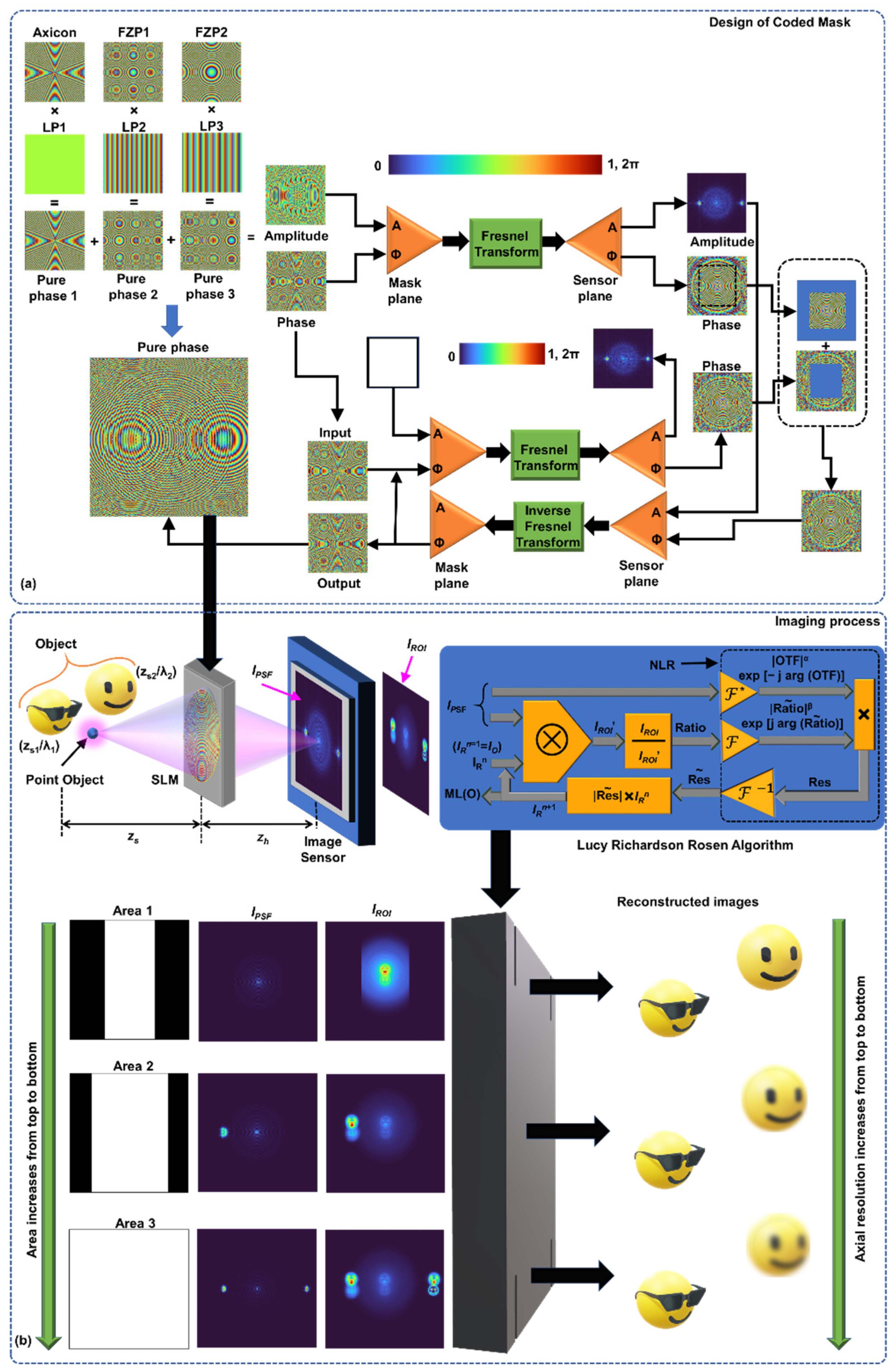

The proposed SEM-CAI consists of two components namely CM design and imaging process as shown in

Figure 1. In the CM design, the SEM concept is applied where the phase functions of several diffractive elements with different axial propagation characteristics are mapped to different regions of the image sensor mutually exclusively – without spatial overlap. This is achieved by combining unique linear phases (LPs) with the phase functions of different diffractive elements. There are no rules on what diffractive elements are to be used, where to map the functions on the image sensor, and what relationship between the area of the image sensor and axial resolution is needed. All the above can be selected depending upon the requirements ‘on-demand’.

—refers to complex conjugate following a Fourier transform; - Inverse Fourier transform; Rn is the nth solution and n is an integer, when n = 1, IRn = IROI; NLR – Non-linear reconstruction; ML – Maximum Likelihood; α and β are varied from -1 to 1.

In this study, three diffractive elements namely a diffractive axicon and two Fresnel zone plates (FZPs) with different focal distances are selected. The diffraction pattern generated by the axicon is mapped to the origin of the image sensor. The diffraction patterns from the FZPs are mapped at certain distances away from the center in the positive and negative sides along the horizontal direction. The above mapping was designed such that when the area of the recording is increased, the axial resolution is increased. When the area includes only the diffraction pattern of axicon, a low axial resolution is obtained. When the area includes the diffraction patterns of axicon and FZP1 then the axial resolution increases and when the area includes all the diffraction patterns, then the axial resolution is increased further. It is possible to have greyscale masks that can increase the contribution of one of the diffraction patterns with respect to the other. The maximum axial resolution is given by the NA, ~λ/NA2. The proposed SEM-CAI allows to tune the axial resolution from a certain value to the maxima but cannot be used to achieve super axial resolution.

In this study, only spatially incoherent and temporally coherent light sources are considered. The phase functions of the diffractive axicon, FZP1 and FZP2 are given as

,

and

respectively, where

Λ is the period of the axicon,

,

f1 and

f2 are the focal distances of FZP1 and FZP2 respectively. The three LPs assigned to the above three masks are

, where

k = 1, 2 and 3. The above LPs are combined with the phase functions of diffractive elements as

resulting in a complex function. A recently developed computational algorithm named transport of amplitude into phase based on Gerchberg-Saxton algorithm (TAP-GSA) is used to convert the complex function Ψ

CM into a phase only function as shown in

Figure 1a [

29]. Therefore, the CM can be expressed as

. The resulting phase-only CM is used for the next step – imaging process. The above approximation is achieved by applying amplitude and phase constraints in the sensor plane. The generated amplitude matrix during forward propagation is replaced by the amplitude matrix obtained for the forward propagation of the complex CM. The phase matrix is replaced as above but partially quantified by a term called degrees of freedom given by the number of pixels replaced in the matrix to the total number of pixels of the phase matrix. After several iterations, a phase-only equivalent of a complex CM is obtained. The application of TAP-GSA is crucial to the implementation of SEM as the alternative random multiplexing method developed for Fresnel incoherent correlation holography (FINCH) results in speckle noises affecting the overall tunability of axial resolution [

30,

31]. When TAP-GSA was implemented to FINCH, instead of the random multiplexing, a significant improvement in SNR and light throughput was observed. The commented MATLAB code for implementing TAP-GSA is provided in the supplementary materials (Supplementary_code1.txt) [

32].

The imaging process shown in

Figure 1b in the next step can be mathematically expressed as follows: A point object is considered in the object domain

from the CM. The complex amplitude reaching the CM is given as

, where

is the amplitude,

Q is a quadratic phase function given as

,

L is the linear phase function given as

and

C1 is a complex constant. The complex amplitude after the CM is given as

which is propagated by a distance of

zh and recorded by an image sensor whose intensity distribution is given as

where ‘

’ is a 2D convolutional operator and

is the location vector in the sensor plane. However, unlike the previous developments of CAI and I-COACH, there is a new equality in the proposed approach which is

where

C11,

C12,

C13 are complex constants. The above equality is possible because of SEM which has a much deeper meaning. In Eq. (1), there is self-interference

between the ensemble of optical fields, whereas the equality shown in Eq. (2), has a unique behavior

, where

A represents the ensemble of diffracted fields generated by the CM. In the first case, where there is self-interference, the nature of light is spatially incoherent and temporally coherent which matches with the source specifications. In the second case due to SEM, the fields generated by the CM that are mapped to different locations behave as if they are not coherent with respect to one another even though derived from the same object point. This is a fundamental change through SEM which allows such tunability. Equation (1) can be expressed as

where

,

and

are PSFs of axicon, FZP1 and FZP2 respectively. By selecting the area of the recordings, it is possible to control the contributions from the different diffractive elements.

has a low sensitivity to changes in depth and wavelength, whereas

and

have a high sensitivity to changes in depth and wavelength as given by the numerical aperture NA. Therefore, when there is a change in depth and only the central region of the recording containing only the diffracted field of axicon is considered, then the correlation curve given as

will be broad as

, where ‘

is a 2D correlation operator. The same argument also applies to changes in wavelength. Let us consider the other cases when the area includes a diffracted field of FZP in addition to that from axicon,

will be sharper than the previous case as

. Once again, the above is true for the wavelength. In this way, the axial resolution can be tuned between the limits of axicon and lens which are

and

respectively, where

D is the diameter of the CM [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

The proposed SEM-CAI is a linear, shift-invariant system and therefore,

A 2D object with N points can be represented mathematically as a collection of N Delta functions given by

where

aj’s are constants. The response to object intensity based on the assumption that a spatially incoherent and temporally coherent light source is considered is given as

There are numerous deconvolution methods that can be applied and, in this study, LRRA and WD are used for reconstructing the object information as shown in

Figure 1b. The (

n+1)

th reconstructed image is given as

where ‘

’ indicates the NLR operation which is given as

, where

is the Fourier transform of

X and

A and

B are the two matrices. The

α and

β are tuned between -1 and 1 to obtain the optimal entropy and a fast convergence. The LRRA has been thoroughly discussed in [

16,

17]. The algorithm is briefly summarized here. The LRRA begins with an initial guess solution of the object which is the

IROI. In principle, the initial guess can be any matrix, even random, but to improve the convergence, the initial guess is selected as

IROI. This initial guess is convolved with

IPSF to obtain

IROI’ which will be

IROI if the initial guess was the actual solution. The ratio between the recorded response to object intensity and obtained matrix given as Ratio =

IROI/

IROI’ is calculated. Then the Ratio is processed with

IPSF using NLR to obtain the Residue. The Residue is multiplied to the previous solution which is the initial guess solution to obtain the next solution (

n=2). This process is iterated until an optimal solution is obtained. During the reconstruction, the values of

α and

β are set to a value and are not changed once the iteration is started. The commented MATLAB code is provided in the supplementary materials (Supplementary_code2.txt).

3. Simulation Results

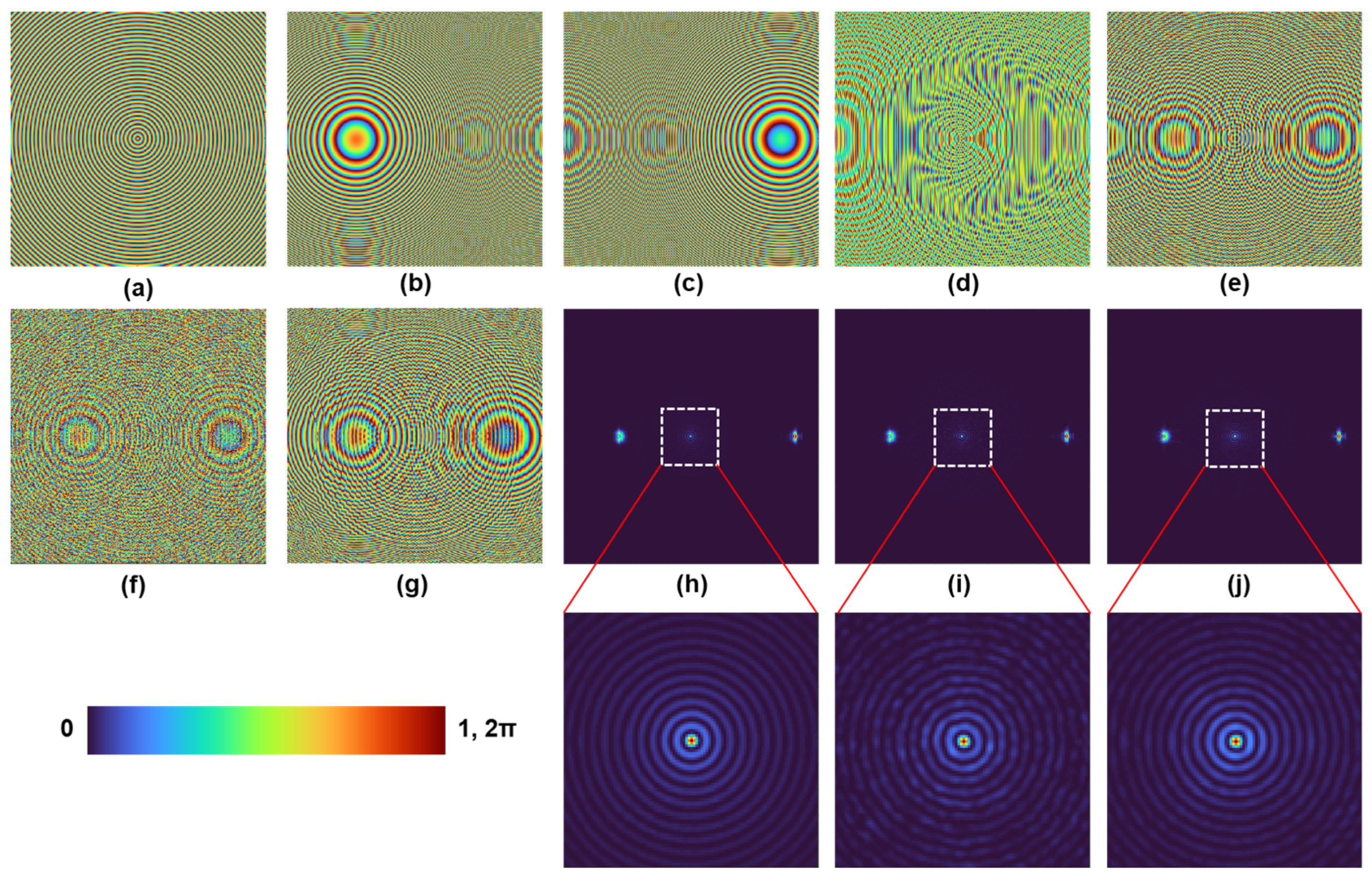

The simulation studies were carried out in MATLAB software (version R2022a). A matrix size of 500 × 500 pixels, a pixel size Δ = 10 μm, wavelength

λ = 632.8 nm, object distance

zs = 1 m, and a recording distance (distance between CM and image sensor)

zh = 0.2 m are selected. Three greyscale diffractive elements were designed: Axicon with

Λ = 80 μm with no linear phase (

ak =

bk = 0), FZP1 (

f1 = 0.16 m) (

ak = -0.007,

bk = 0) and FZP2 (

f2 = 0.17 m) (

ak = 0.01,

bk = 0). The phase images of the masks are shown in

Figure 2a–c respectively. The magnitude and phase of the complex function of CM obtained by the sum of the three phase-only functions of a diffractive axicon, FZP1 with LP2 and FZP2 with LP3 are shown in

Figures 2d and 2e respectively. The phase-only CMs obtained by random multiplexing and TAP-GSA with a degree of freedom of 0.16 are shown in

Figure 2f and 2g respectively. The diffraction pattern obtained at a distance of 0.2 m from the CM for

Figure 2d,e,

Figure 2f,g are shown in

Figure 2h, 2i and 2j respectively. The magnified regions of the intensity matrices for the above three cases show a reduced scattering noise with TAP-GSA.

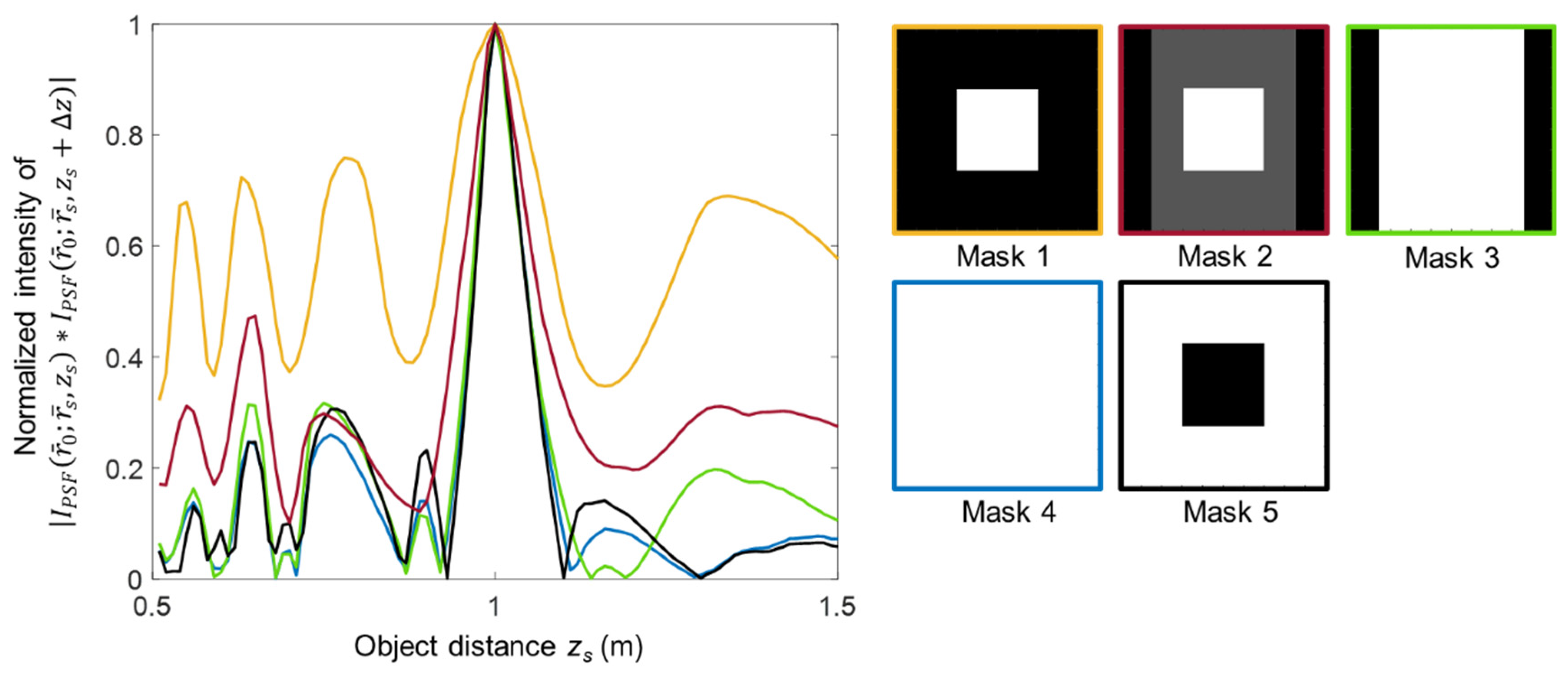

The axial behavior is simulated next. The

IPSF is simulated for different values of

zs and processed with

IPSF corresponding to a single value of

zs as

, where

zs = 1 m and Δ

zs is tuned from -0.5 m to 0.5 m. The normalized curves of

for five cases of masks applied to recordings are shown in

Figure 3. It can be seen that by selecting an appropriate mask, different strengths of axial correlation lengths can be contributed from different areas of the recordings resulting in a desired effective axial resolution.

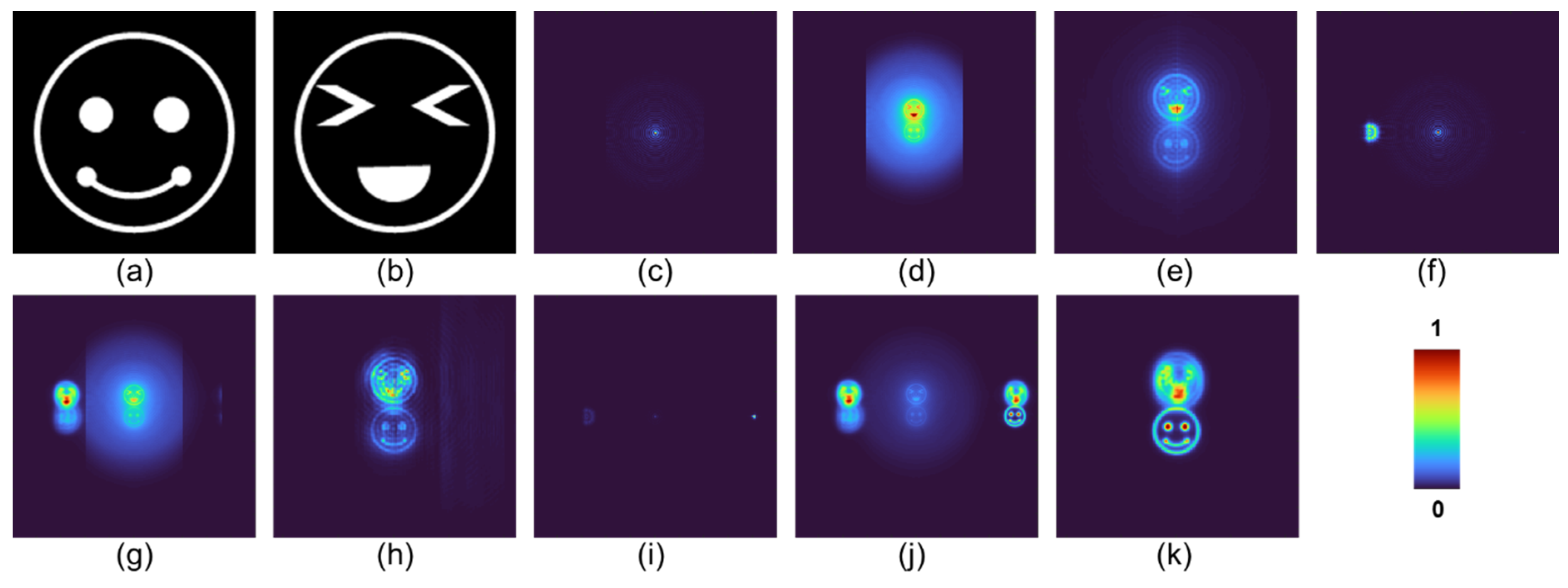

The simulated optical experiments are discussed next. Two ‘Smiley’ objects were selected for the study as shown in

Figure 4a and 4b respectively. The two objects were separated by a distance of 20 cm. Even though there are clear variations in the curves shown in

Figure 3 for different cases of the masks, in imaging it is challenging to observe minor changes in axial resolution. Therefore, for the simulation study, only three cases are considered corresponding to Masks – Mask1, Mask2, and Mask4. The images of the simulated

IPSFs,

IROIs, and

IRs for Mask1, Mask2, and Mask4 are shown in

Figure 4. From the results, it can be seen that the axial resolution increases from Mask1 to Mask4. The reconstructed second smiley object – Test object 2 becomes more and more blurred with an increase in the axial resolution. For all the above cases, LRRA was applied with three to five iterations with

α = 0,

β = 0 to 0.2.

4. Experiments

The schematic and a photograph of the experimental setup are shown in

Figure 5a,b. The experimental setup includes the following optical components: Light emitting diode (LED) from Thorlabs with 940 mW power, operating at a wavelength of λ = 660 nm and has a bandwidth of Δλ = 20 nm; two irises; polarizer; three refractive lenses (RLs) with a focal length

f = 3.5 cm,

f = 5 cm and

f = 5 cm; pinhole of size 50 μm; beam splitter (BS); Exulus-4K 1/M spatial light modulator (SLM) from Thorlabs with 3840 × 2160 pixels and a pixel size of 3.74 μm and Zelux CS165MU/M monochrome image sensor with 1440 × 1080 pixels with a pixel size of ~3.5 µm.

The light from the LED is controlled by an iris and collimated by an RL (

f = 3.5 cm). The collimated beam is passed through a polarizer, which is oriented along the active axis of the SLM. Two objects were created by shifting a pinhole of 50 μm in horizontal and vertical directions. Object 1 (Two points along horizontal direction separated by 120 μm) and Object 2 (Two points along vertical direction separated by 120 μm) are created. The object is critically illuminated by an RL (

f = 5 cm). The light beam from the object is collimated by an RL (

f = 5 cm) and the beam size is controlled by another iris. The collimated light beam enters the BS and is incident on the SLM. The CM was created by combining two FZPs (with a focal length of 16 cm) and one diffractive axicon (with

Λ = 187 μm) using TAP-GSA with a degree of freedom of 75%. The phase-only CM from TAP-GSA is displayed on the SLM which modulates the light beam creating the diffraction spots of the two FZPs and diffractive axicon at predefined locations on the image sensor. The

IPSF and

IROI were recorded by the image sensor located at a distance of 20 cm from the SLM. The

IPSF was recorded using a 50 μm pinhole. Object 1 and Object 2 were recorded at two different depths

zs = 5 cm and

zs = 5.4 cm respectively. The object information was reconstructed by processing

IPSF and

IROI using LRRA. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 6. The experimentally recorded

IPSF and

IROI are shown in

Figure 6a,b respectively. Two masks Mask1 and Mask2 were applied to the recorded

IPSF and

IROI and reconstructed. The images of the masks - Mask1 and Mask2 and reconstructed images are shown in

Figure 6c, 6e, 6d and 6f respectively. The phase image of the CM generated using TAP-GSA with degrees of freedom of 75% is shown in

Figure 6g. Comparing the reconstruction results of

Figure 6d,f, the axial resolution of 6f is better than that of 6d demonstrating the tunability of axial resolution post-recording. In the case of Mask1 (

Figure 6c), there is contribution only from the diffractive axicon which has a long axial correlation length resulting in a low axial resolution. In the case of Mask2 (

Figure 6e), there is contribution from two FZPs and a diffractive axicon resulting in short axial correlation length. The shorter correlation length for Mask2 arises due to the averaging effect of correlation lengths corresponding to diffractive axicon and FZPs. However, in the above two cases, the lateral correlation length is the same as the NA is constant for both cases. In all the above cases, the typical range of

α, β and the number of iterations for LRRA are 0 to 0.4, 1 and 10 to 30 respectively. The experimental results are matched with the simulation results and validate the theory of SEM-CAI.

5. Discussion

In this study, a simple yet useful technique called SEM has been introduced in CAI for tuning axial resolution independent of lateral resolution post-recording. Like any new technique, an advancement is made here with SEM-CAI with a compromise on the field of view. The above approach is suitable only for recording events and scenes with a limited field of view. The above understanding also gives rise to a question. Can direct imaging approaches be applied here by reducing the field of view and tiling different configurations along the x and y directions on the image sensor? This is impossible due to the interdependency between lateral and axial resolutions in direct imaging approaches. Even if that condition is relaxed, the direct imaging approach can allow only discrete tuning of axial resolution along the tiled images. The interdependency between lateral and axial resolutions by NA will cause a change in lateral resolution also along the tiled images.

The developed SEM-CAI, even though has been demonstrated only for tuning axial resolution independent of lateral resolution, the concept can be extended to tuning spectral resolution independent of lateral resolution as well. The simulation results for tuning spectral resolution post-recording using a monochrome sensor for three masks Mask1, Mask2 and Mask4 were carried out. The spectral correlation curves obtained from

for a wavelength variation between 400 to 800 nm for the three masks are shown in

Figure 7. As it is seen, the spectral resolution improves from Mask1 to Mask4. The same approach can also be used to tune lateral resolution which has not been discussed in [

27,

28] and so far, not possible after recording a picture or a video. However, a low lateral resolution does not have any useful application.

This tutorial unifies also the previous studies on this topic using a hybrid imaging system with a lens and an axicon and an Airy beam generator [

27,

28]. In this study, only two types of elements namely a diffractive lens and a diffractive axicon have been used. However, it is possible to use a wide range of diffractive elements and beams such as self-rotating beams [

25,

38,

39], Airy beams [

40,

41], and Higher order Bessel beams [

42,

43,

44]. In this study, only three beams have been used, however lesser or a greater number of beams can be used to achieve axial and spectral tunability post-recording.

Figure 1.

(a) Design of coded mask: Schematic of TAP-GSA. Three masks: Axicon, FZP1 and FZP2 are combined with unique LPs to map every diffraction pattern to a predefined area on the image sensor. The resulting three masks are summed to obtain a complex function. The phase of the complex function and a uniform matrix were used as phase and amplitude constraints, respectively, in the mask domain. The amplitude distribution obtained by Fresnel propagation of the ideal complex function to the sensor domain is used as a constraint in the sensor domain. The phase distribution obtained at the sensor plane by Fresnel propagation is combined with the ideal phase distribution. The process is iterated to obtain a phase-only CM. A – Amplitude; Φ – phase; FZP – Fresnel zone plate; LP – Linear phase; (b) Imaging process: The CM is used to record IPSF and IROI and the above intensity distributions are mapped to different regions of the image sensor. With an increase in the area, the axial correlation lengths decrease. OTF—Optical transfer function; n—number of iterations; ⊗—2D convolutional operator;

Figure 1.

(a) Design of coded mask: Schematic of TAP-GSA. Three masks: Axicon, FZP1 and FZP2 are combined with unique LPs to map every diffraction pattern to a predefined area on the image sensor. The resulting three masks are summed to obtain a complex function. The phase of the complex function and a uniform matrix were used as phase and amplitude constraints, respectively, in the mask domain. The amplitude distribution obtained by Fresnel propagation of the ideal complex function to the sensor domain is used as a constraint in the sensor domain. The phase distribution obtained at the sensor plane by Fresnel propagation is combined with the ideal phase distribution. The process is iterated to obtain a phase-only CM. A – Amplitude; Φ – phase; FZP – Fresnel zone plate; LP – Linear phase; (b) Imaging process: The CM is used to record IPSF and IROI and the above intensity distributions are mapped to different regions of the image sensor. With an increase in the area, the axial correlation lengths decrease. OTF—Optical transfer function; n—number of iterations; ⊗—2D convolutional operator;

Figure 2.

Simulation results for design and analysis of CM: Phase images of (a) diffractive axicon, (b) FZP1, (c) FZP2. (d) Amplitude and (e) phase of CM. Phase images of CM designed by (f) random multiplexing and (g) TAP-GSA. Diffraction patterns obtained from (h) complex CM, (i) CM designed by random multiplexing and (j) CM designed by TAP-GSA.

Figure 2.

Simulation results for design and analysis of CM: Phase images of (a) diffractive axicon, (b) FZP1, (c) FZP2. (d) Amplitude and (e) phase of CM. Phase images of CM designed by (f) random multiplexing and (g) TAP-GSA. Diffraction patterns obtained from (h) complex CM, (i) CM designed by random multiplexing and (j) CM designed by TAP-GSA.

Figure 3.

Simulation results of axial correlation curves for different masks applied to the recorded IPSF and IROI. The grey region in Mask 2 has a ratio of 0.33 with the white region.

Figure 3.

Simulation results of axial correlation curves for different masks applied to the recorded IPSF and IROI. The grey region in Mask 2 has a ratio of 0.33 with the white region.

Figure 4.

(a) Test object 1, (b) Test object 2. Images of (c) IPSF (d) IROI (e) IR for Mask 1. Images of (f) IPSF (g) IROI (h) IR for Mask 2. Images of (i) IPSF (j) IROI (k) IR for Mask 4.

Figure 4.

(a) Test object 1, (b) Test object 2. Images of (c) IPSF (d) IROI (e) IR for Mask 1. Images of (f) IPSF (g) IROI (h) IR for Mask 2. Images of (i) IPSF (j) IROI (k) IR for Mask 4.

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic and (b) photograph of the experimental configuration. (1) LED, (2) iris, (3) refractive lens (f = 3.5 cm), (4) polarizer, (5) refractive lens (f = 5 cm), (6) object/pinhole, (7) refractive lens (f = 5 cm), (8) iris, (9) beam splitter, (10) spatial light modulator, (13) monochrome image sensor.

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic and (b) photograph of the experimental configuration. (1) LED, (2) iris, (3) refractive lens (f = 3.5 cm), (4) polarizer, (5) refractive lens (f = 5 cm), (6) object/pinhole, (7) refractive lens (f = 5 cm), (8) iris, (9) beam splitter, (10) spatial light modulator, (13) monochrome image sensor.

Figure 6.

Experimentally recorded (a) IPSF, (b) IROI. Images of (c) Mask1 and the (d) corresponding reconstruction. Images of (e) Mask 2 and the (f) corresponding reconstruction. (g) Phase image of the CM desiged by TAP-GSA with 75% degrees of freedom.

Figure 6.

Experimentally recorded (a) IPSF, (b) IROI. Images of (c) Mask1 and the (d) corresponding reconstruction. Images of (e) Mask 2 and the (f) corresponding reconstruction. (g) Phase image of the CM desiged by TAP-GSA with 75% degrees of freedom.

Figure 7.

Simulation results of spectral correlation curves for different masks applied to the recorded IPSF and IROI. The grey region in Mask 2 has a ratio of 0.33 with the white region.

Figure 7.

Simulation results of spectral correlation curves for different masks applied to the recorded IPSF and IROI. The grey region in Mask 2 has a ratio of 0.33 with the white region.