Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Criteria for the Diagnosis of Celiac Disease: Historical Outline and Current Status

1.2. Aim of the Study

2. Material and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

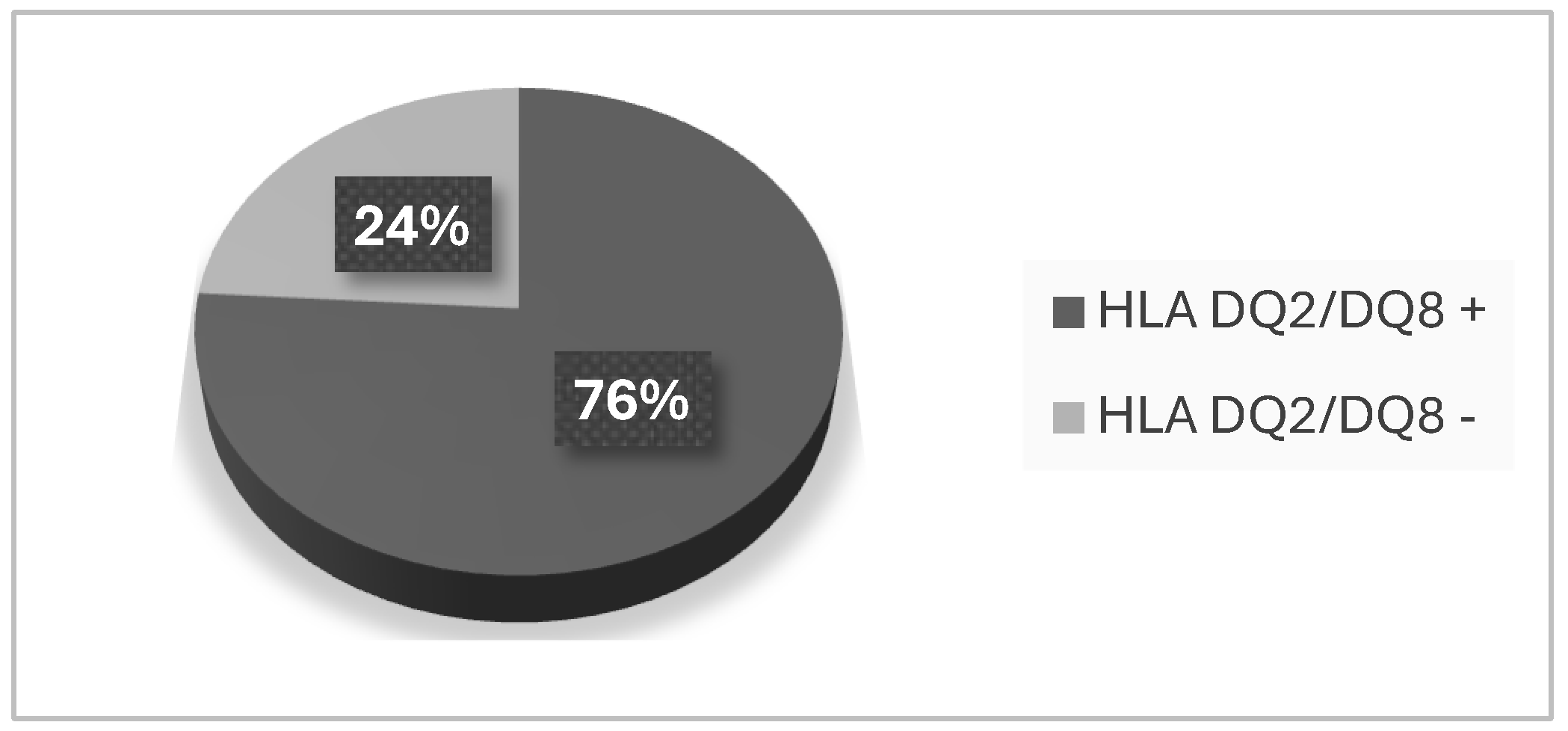

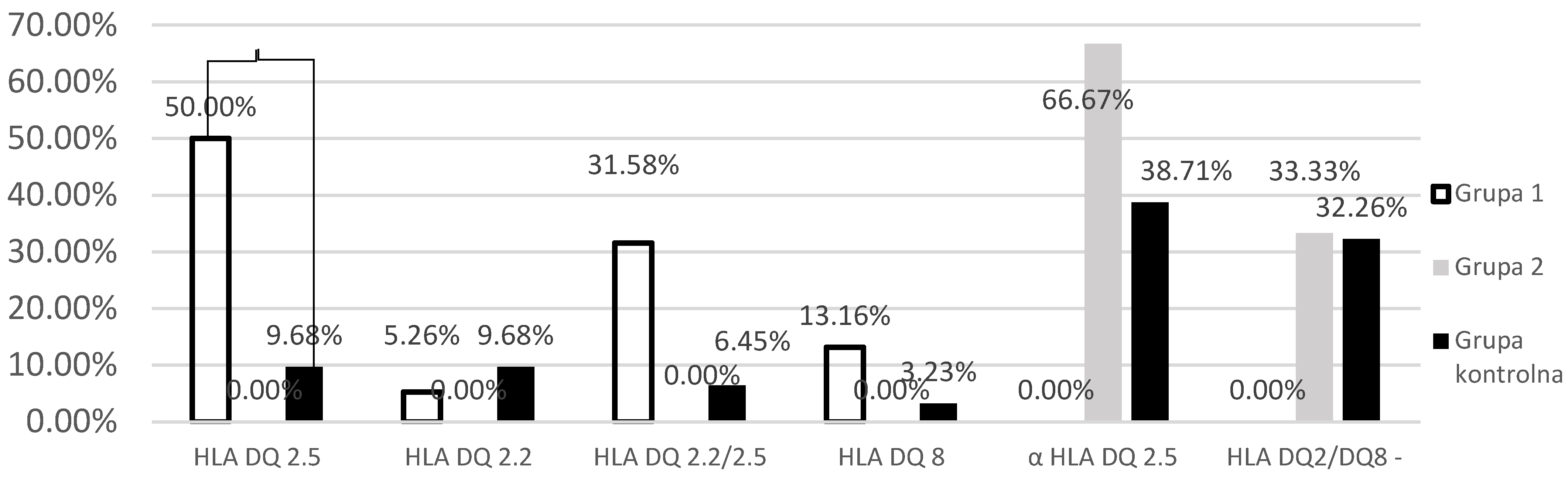

Investigation of the Prevalence of HLA-DQ 2 and HLA-DQ 8

4. Discussion

5. Summary

6. Conclusion

References

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; Mearin, M.L.; Phillips, A.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Giersiepen, K.; Branski, D.; Catassi, C.; et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 54, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.; Kurppa, K.; Mearin, M.L.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingley, P.J.; Norcross, A.J.; Lock, R.J.; Ness, A.R.; Jones, R.W. Undiagnosed coeliac disease at age seven: population based prospective birth cohort study. BMJ 2004, 328, 322–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäki, M.; Mustalahti, K.; Kokkonen, J.; Kulmala, P.; Haapalahti, M.; Karttunen, T.; Ilonen, J.; Laurila, K.; Dahlbom, I.; Hansson, T.; et al. Prevalence of Celiac Disease among Children in Finland. New Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2517–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laass, M.W.; Schmitz, R.; Uhlig, H.H.; Zimmer, K.-P.; Thamm, M.; Koletzko, S. The Prevalence of Celiac Disease in Children and Adolescents in Germany. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Online 2015, 112, 553–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P. , et al., Prevalence of Celiac disease in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015.

- Fasano, A. , et al., Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study, in Arch Intern Med. 2003: United States. p. 286-92.

- Singh, P.; Arora, S.; Lal, S.; Strand, T.A.; Makharia, G.K. Risk of Celiac Disease in the First- and Second-Degree Relatives of Patients With Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Y. and S. Mermer, Frequency of celiac disease and distribution of HLA-DQ2/DQ8 haplotypes among siblings of children with celiac disease. World J Clin Pediatr, 2022. 11(4): p. 351-359.

- GW., M. GW., M., Diagnostic criteria in celiac disease. 1970: Acta Paediatr Scand. p. 461–3.

- CC, B. Definition of adult coeliac disease. in Proceedings of the Second International Symposium. 1974. Noordwijkerhout, The Netherlands: H.E. Stenfert Kroese B.V., Leiden.

- McNeish AS, H.K. , Rey J, Shmerling DH, Walker-Smith JA., Re-evaluation of diagnostic criteria for celiac disease. 1979, Arch Dis Child. p. 783-6.

- Revised criteria for diagnosis of coeliac disease. Report of Working Group of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Arch Dis Child, 1990. 65(8): p. 909-11.

- Richey, R.; Howdle, P.; Shaw, E.; Stokes, T. ; on behalf of the Guideline Development Group Recognition and assessment of coeliac disease in children and adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2009, 338, b1684–b1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Card, T.R.; Ciacci, C.; Ciclitira, P.J.; Green, P.H.R.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Holdoway, A.; van Heel, D.A.; et al. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut 2014, 63, 1210–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karell, K.; Louka, A.S.; Moodie, S.J.; Ascher, H.; Clot, F.; Greco, L.; Ciclitira, P.J.; Sollid, L.M.; Partanen, J. Hla types in celiac disease patients not carrying the DQA1*05-DQB1*02 (DQ2) heterodimer: results from the european genetics cluster on celiac disease. Hum. Immunol. 2003, 64, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, N.; Cola, A.; Piscopo, C.; Capuano, M.; Galatola, M.; Greco, L.; Sacchetti, L. High Frequency of Haplotype HLA-DQ7 in Celiac Disease Patients from South Italy: Retrospective Evaluation of 5,535 Subjects at Risk of Celiac Disease. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0138324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, F.; Hermansen, M.N.; Pedersen, M.F.; Hillig, T.; Toft–Hansen, H.; Sölétormos, G. Mapping of HLA– DQ haplotypes in a group of Danish patients with celiac disease. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2015, 75, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakır, M.; Baran, M.; Uçar, F.; Akbulut, U.E.; Kaklıkkaya, N.; Ersöz. Accuracy of HLA-DQ genotyping in combination with IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase serology and a "scoring system" for the diagnosis of celiac disease in Turkish children. Turk J Pediatr 2014, 56, 347–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- zgenel Ş, M. , et al., HLA-DQ2/DQ8 frequency in adult patients with celiac disease, their first-degree relatives, and normal population in Turkey. Turk J Gastroenterol.

- Fernández-Bañares, F.; Arau, B.; Dieli-Crimi, R.; Rosinach, M.; Nuñez, C.; Esteve, M. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Show 3% of Patients With Celiac Disease in Spain to be Negative for HLA-DQ2.5 and HLA-DQ8. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 594–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami-Nejad, M. Allele and haplotype frequencies for HLA-DQ in Iranian celiac disease patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 6302–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapitány, A.; Tóth, L.; Tumpek, J.; Csípő, I.; Sipos, E.; Wooley, N.; Partanen, J.; Szegedi, G.; Oláh, É.; Sipka, S.; et al. Diagnostic significance of HLA-DQ typing in patients with previous coeliac disease diagnosis based on histology alone. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 24, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, E.G. , et al., Gluten tolerance in adult patients with celiac disease 20 years after diagnosis? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2008. 20(5): p. 423-9.

- Bergseng, E.; Dørum, S.; Arntzen, M. .; Nielsen, M.; Nygård, S.; Buus, S.; de Souza, G.A.; Sollid, L.M. Different binding motifs of the celiac disease-associated HLA molecules DQ2.5, DQ2.2, and DQ7.5 revealed by relative quantitative proteomics of endogenous peptide repertoires. Immunogenetics 2015, 67, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Marin, D.L.; Linden, J.; Frank, E.; Pena, R.; Silvester, J.A.; Therrien, A. HLA-DQ7 haplotype among individuals with suspected celiac disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 1414–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkstetter, K.J.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; Popp, A.; Villanacci, V.; Salemme, M.; Heilig, G.; Lillevang, S.T.; Mearin, M.L.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Thomas, A.; et al. Accuracy in Diagnosis of Celiac Disease Without Biopsies in Clinical Practice. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Petroff, D.; Richter, T.; Auth, M.K.; Uhlig, H.H.; Laass, M.W.; Lauenstein, P.; Krahl, A.; Händel, N.; de Laffolie, J.; et al. Validation of Antibody-Based Strategies for Diagnosis of Pediatric Celiac Disease Without Biopsy. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 410–419.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurppa, K.; Salminiemi, J.; Ukkola, A.; Saavalainen, P.; Löytynoja, K.; Laurila, K.; Collin, P.; Mäki, M.; Kaukinen, K. Utility of the New ESPGHAN Criteria for the Diagnosis of Celiac Disease in At-risk Groups. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 54, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, O.; Rosén, A.; Lagerqvist, C.; Carlsson, A.; Hernell, O.; Högberg, L.; Ivarsson, A. Transglutaminase IgA Antibodies in a Celiac Disease Mass Screening and the Role of HLA-DQ Genotyping and Endomysial Antibodies in Sequential Testing. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 57, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouzeau-Girard, H. , et al., HLA-DQ genotyping combined with serological markers for the diagnosis of celiac disease: is intestinal biopsy still mandatory? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2011. 52(6): p. 729-33.

- Alarida, K.; Harown, J.; Di Pierro, M.R.; Drago, S.; Catassi, C. HLA-DQ2 and -DQ8 genotypes in celiac and healthy Libyan children. Dig. Liver Dis. 2010, 42, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, K.; Uqaili, A.A.; Rafiq, M.; Bhutto, M.A. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ2 and -DQ8 haplotypes in celiac, celiac with type 1 diabetic, and celiac suspected pediatric cases. Medicine 2021, 100, e24954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispo, A.; Guarino, A.D.; Siniscalchi, M.; Imperatore, N.; Santonicola, A.; Ricciolino, S.; de Sire, R.; Toro, B.; Cantisani, N.M.; Ciacci, C. “The crackers challenge”: A reassuring low-dose gluten challenge in adults on gluten-free diet without proper diagnosis of coeliac disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 1517–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiepatti, A.; Rej, A.; Maimaris, S.; Cross, S.S.; Porta, P.; Aziz, I.; Key, T.; Goodwin, J.; Therrien, A.; Yoosuf, S.; et al. Clinical classification and long-term outcomes of seronegative coeliac disease: a 20-year multicentre follow-up study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54, 1278–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, M.; Oyarzun, A.; Lucero, Y.; Espinosa, N.; Pérez-Bravo, F. DQ2, DQ7 and DQ8 Distribution and Clinical Manifestations in Celiac Cases and Their First-Degree Relatives. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4955–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Antunes, M.M. , et al., Frequency distribution of HLA DQ2 and DQ8 in celiac patients and first-degree relatives in Recife, northeastern Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 2011. 66(2): p. 227-31.

- Alam, M. , et al., HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 Alleles in Celiac Disease Patients and Healthy Controls. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak, 2022. 32(2): p. 157-160.

- Bodd, M.; Kim, C.; Lundin, K.E.; Sollid, L.M. T-Cell Response to Gluten in Patients With HLA-DQ2.2 Reveals Requirement of Peptide-MHC Stability in Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, A.K.; van de Wal, Y.; Routsias, J.; Kooy, Y.M.C.; van Veelen, P.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Koning, F.; Papadopoulos, G.K. Structure of celiac disease-associated HLA-DQ8 and non-associated HLA-DQ9 alleles in complex with two disease-specific epitopes. Int. Immunol. 2000, 12, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallang, L.-E.; Bergseng, E.; Hotta, K.; Berg-Larsen, A.; Kim, C.-Y.; Sollid, L.M. Differences in the risk of celiac disease associated with HLA-DQ2.5 or HLA-DQ2.2 are related to sustained gluten antigen presentation. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, D.; Anand, A.; De'Ath, A.; Lee, H.; Rees, M.T. UK NEQAS and BSHI guideline: Laboratory testing and clinical interpretation of HLA genotyping results supporting the diagnosis of coeliac disease. Int. J. Immunogenetics 2024, 51 Suppl 1, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).