Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals of CAP

2.1. Definition and Properties of CAP

- Temperature Disparity:

- Ionization and Reactive Species:

- Low Power Requirement:

- Operation Under Ambient Conditions

- Surface Interaction and Modification

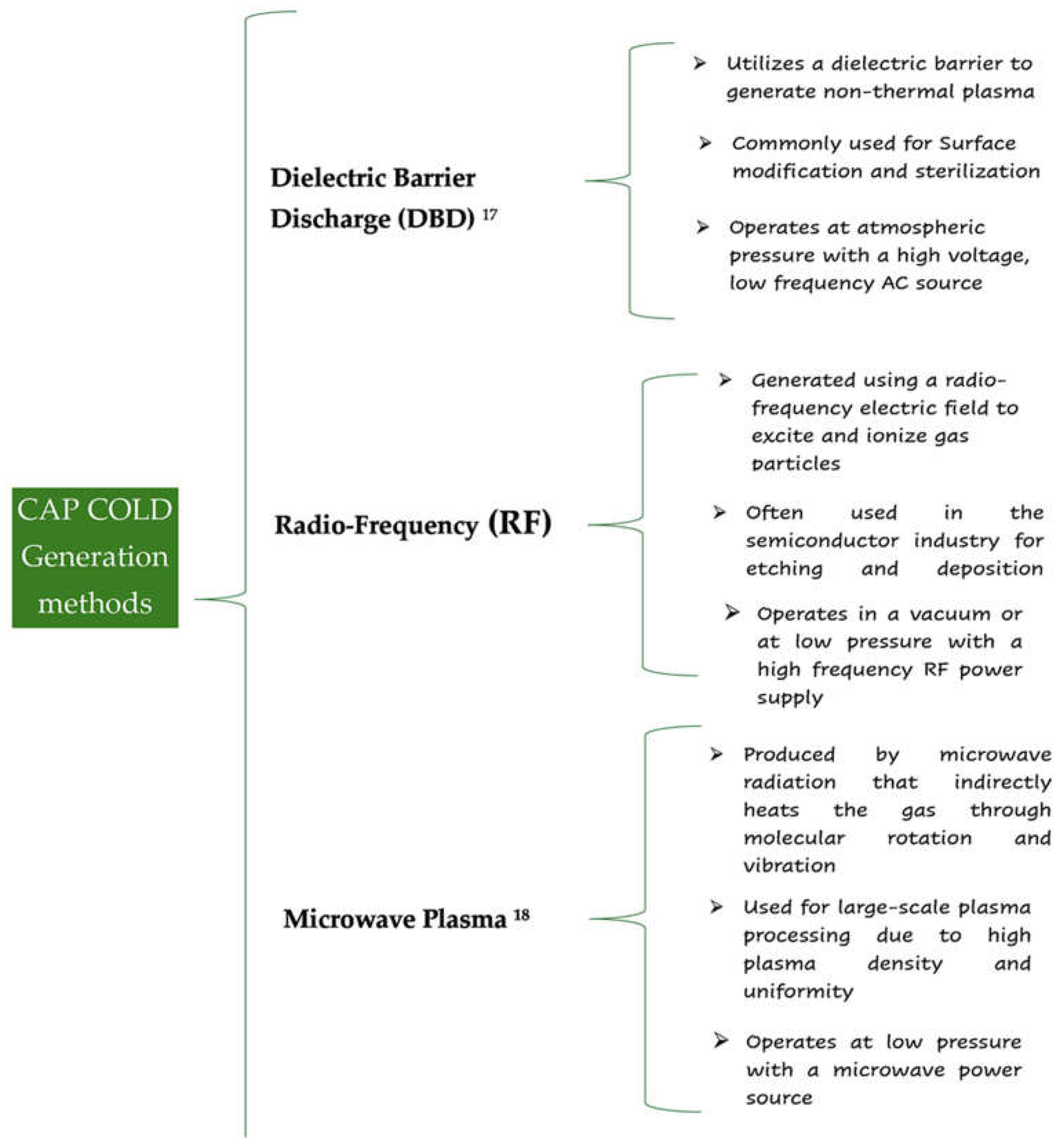

2.2. CAP Generation and Technology

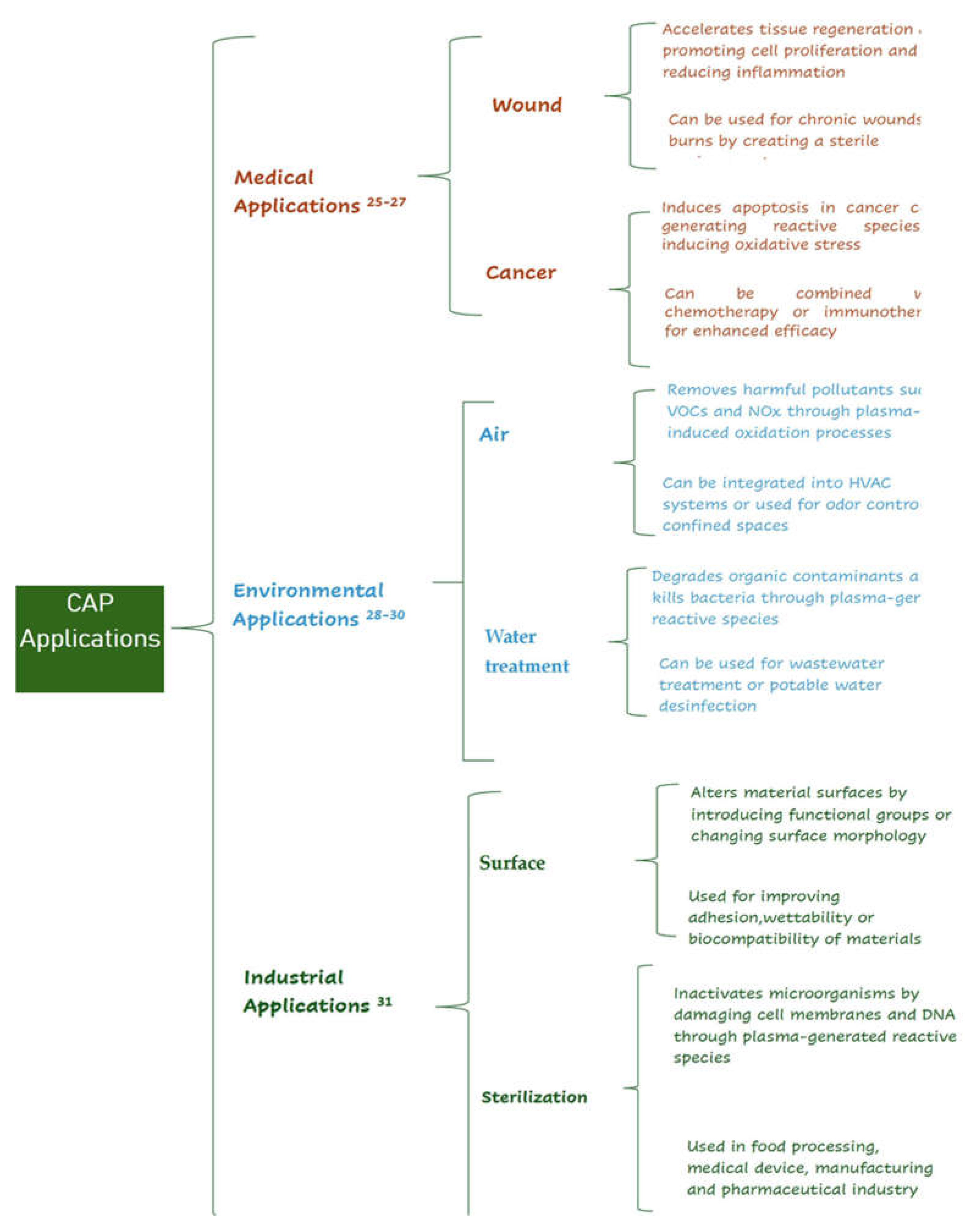

2.3. CAP Applications

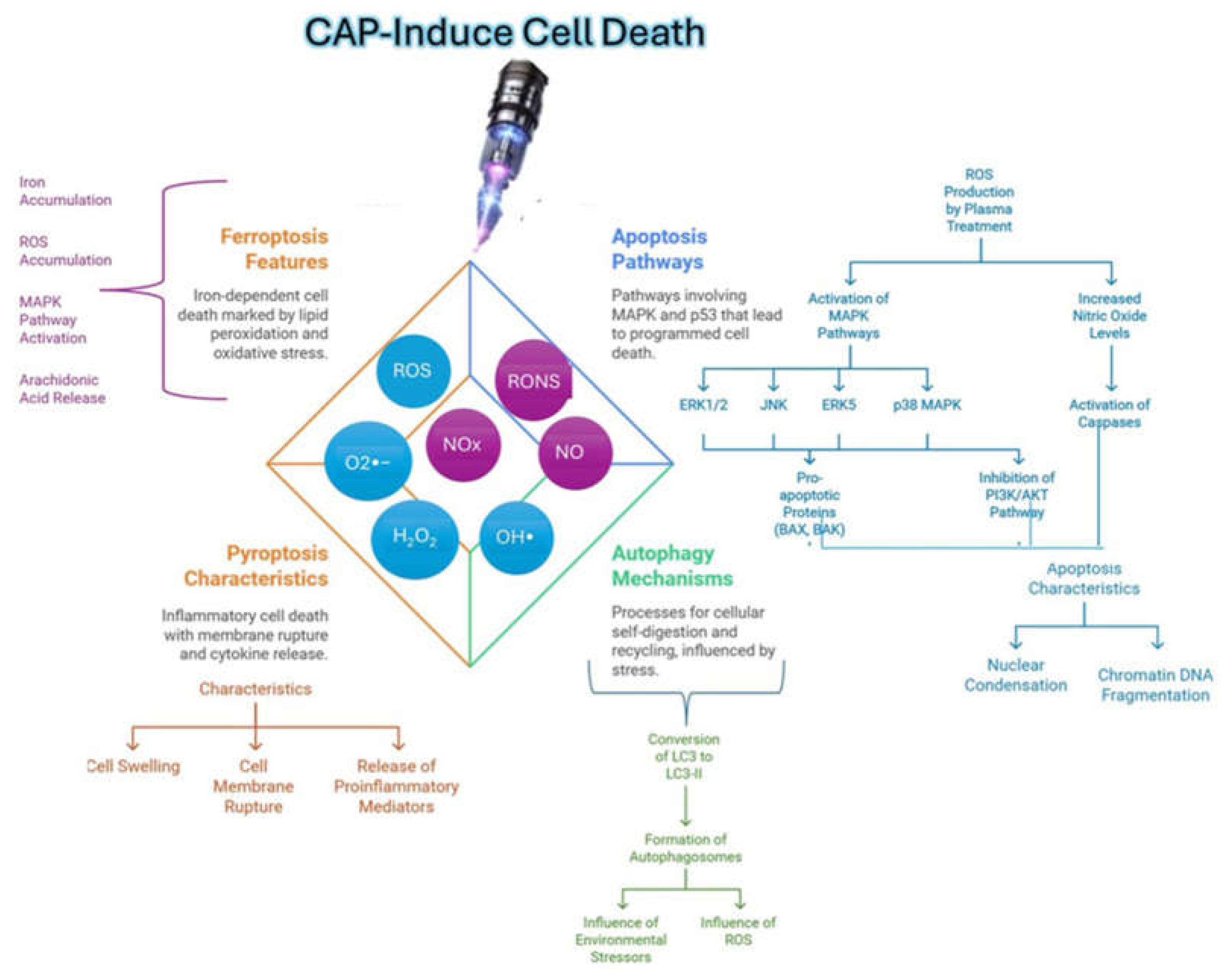

3. Mechanisms of Action of Cold Plasma in Cancer Cells

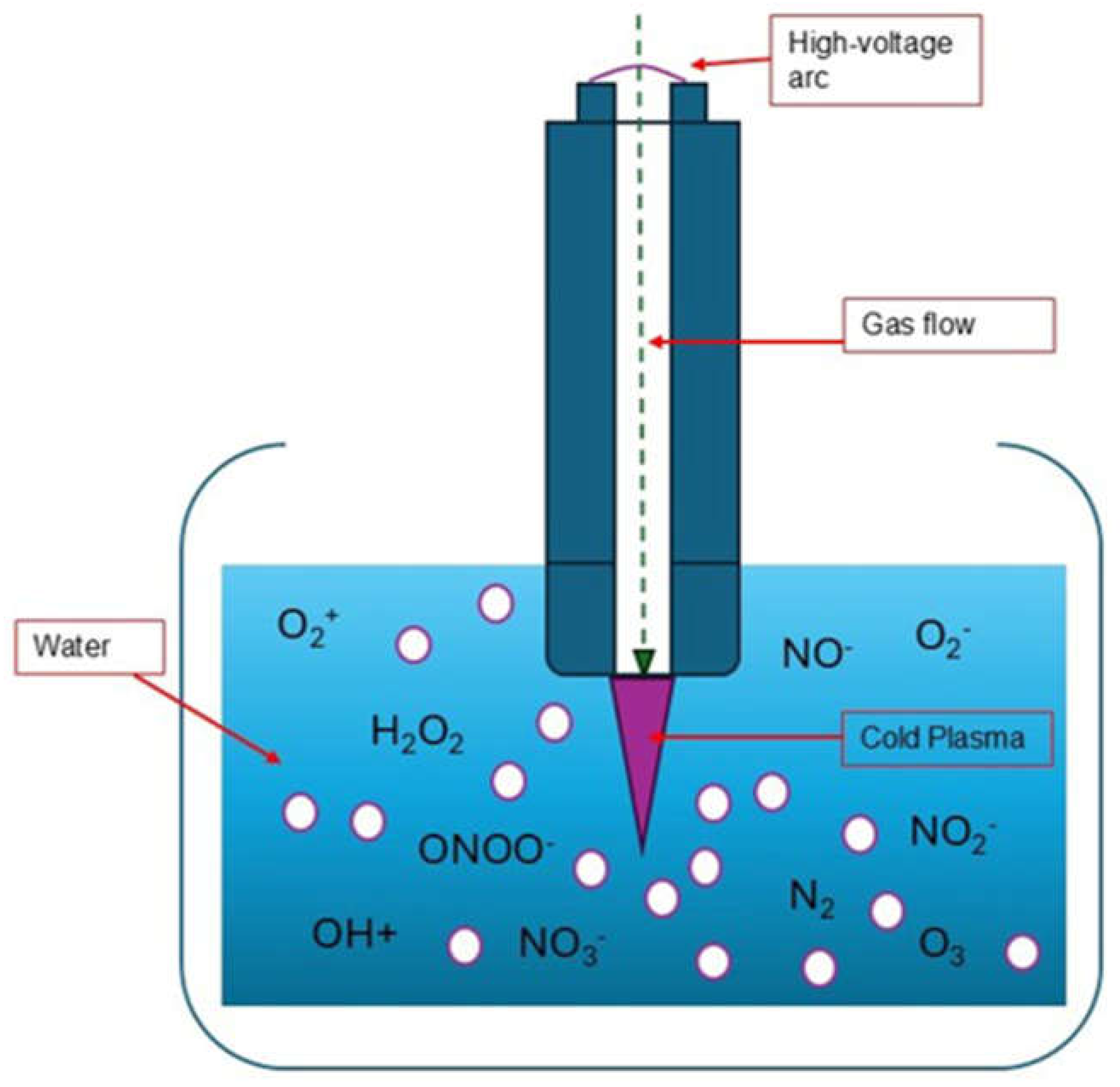

3.1. Generation of RONS

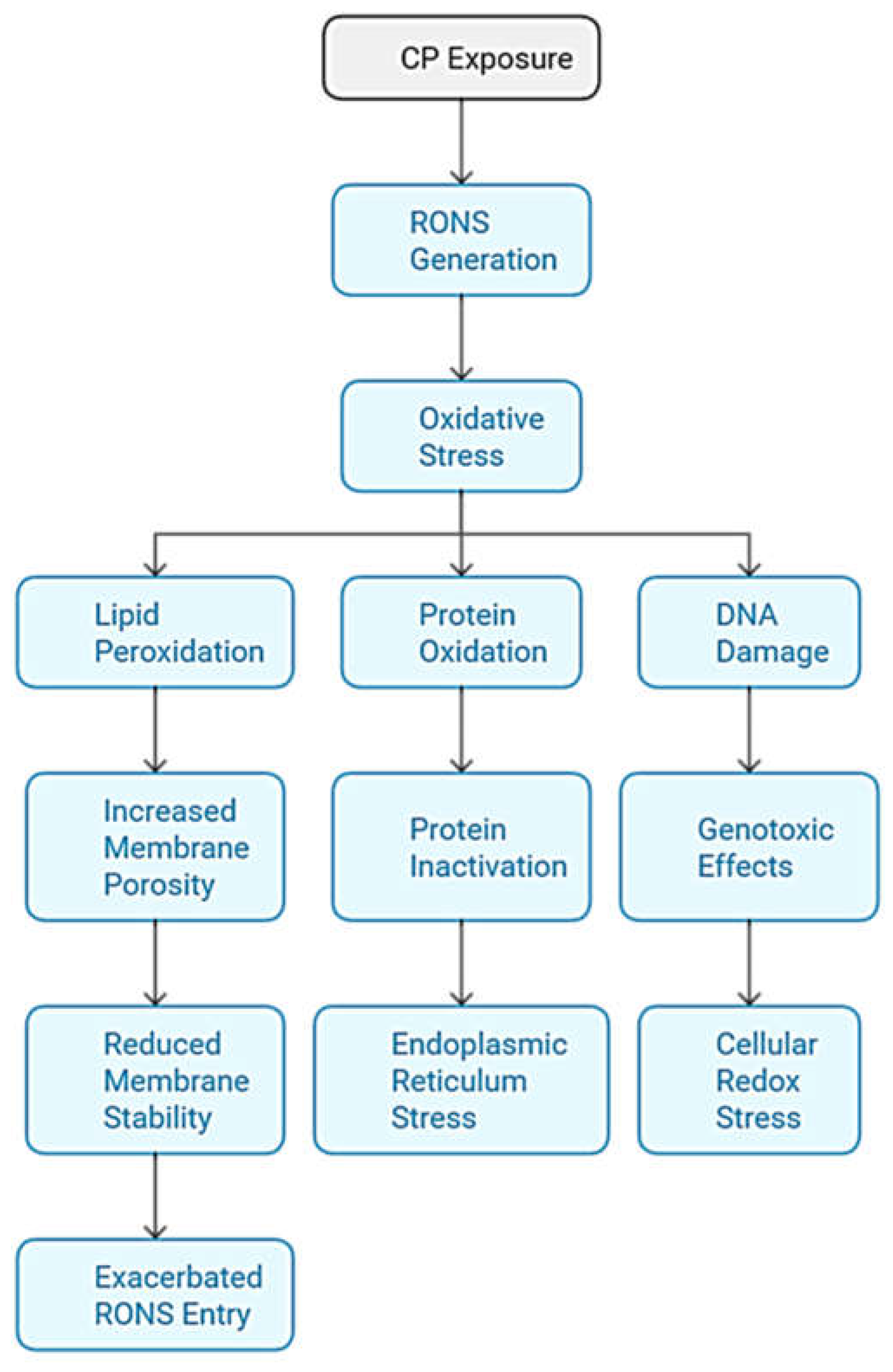

- Lipid Peroxidation: The generation of RONS triggers the peroxidation of cell membrane lipids, especially polyunsaturated fatty acids. This process increases the porosity of the membrane and compromises its structural stability, facilitating a cycle of continuous oxidative damage by allowing an exacerbated entry of more RONS into the cell. This sustained damage to the membrane not only destabilizes its function but can also lead to cell death [35].

- Protein Oxidation: RONS attack intracellular proteins, altering their structure and functionality, which leads to their inactivation. This protein damage causes stress in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which attempts to manage misfolded or damaged proteins through the misfolded protein response (UPR). If the damage is irreparable, ER stress affects cellular homeostasis and can activate signaling pathways that promote apoptosis, thus contributing to programmed cell death.

- DNA damage: RONS cause genotoxic damage to DNA, causing mutations through direct modifications in nitrogenous bases, such as the formation of 8-oxoguanine. This damage activates DNA repair mechanisms in an attempt to maintain genetic integrity, but if the damage is extensive, these mechanisms may be insufficient. The accumulation of mutations and redox imbalance can drive the cell towards apoptosis or, in the case of normal cells, potentially contribute to carcinogenesis.

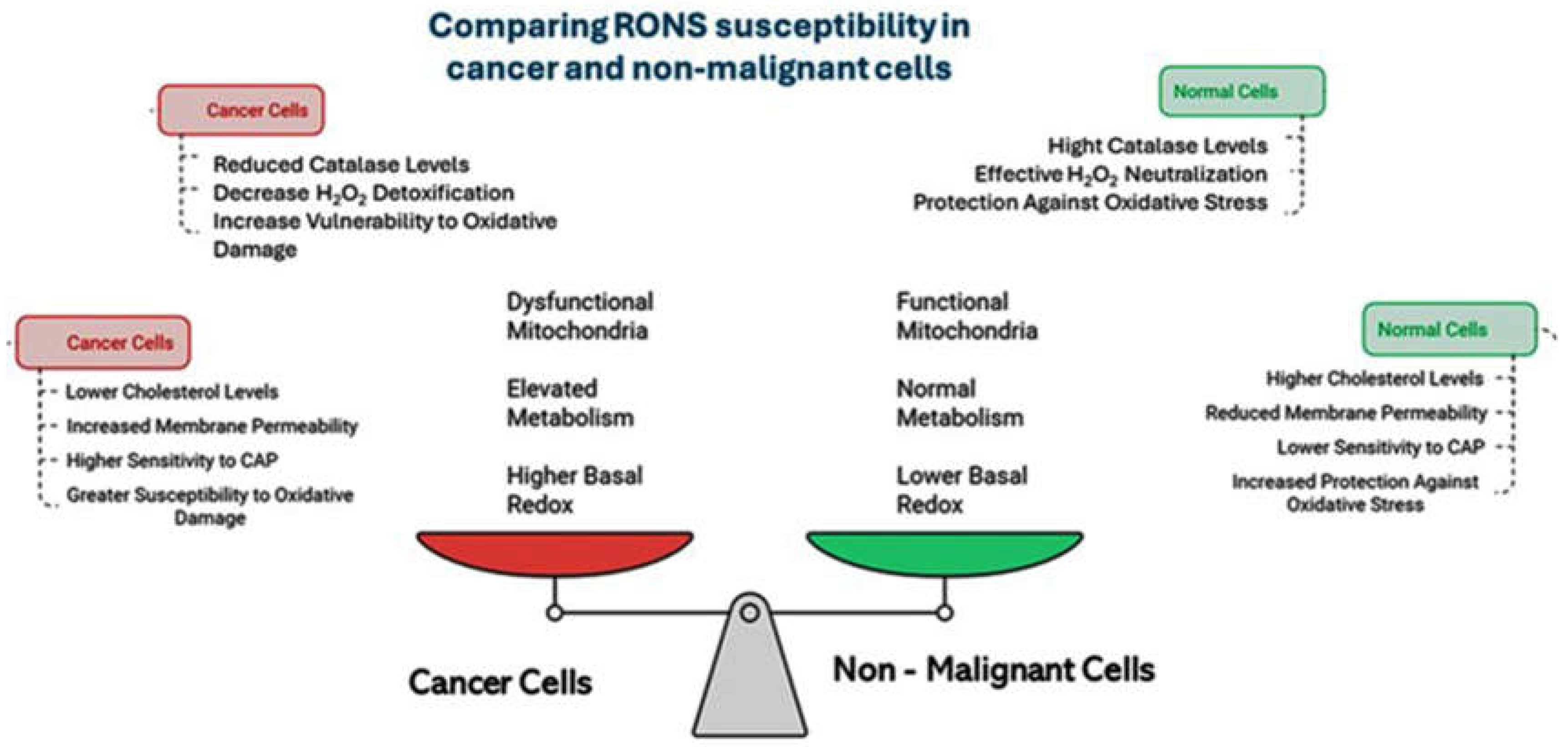

3.2. Selective Induction of Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cells

3.3. Modulation of Apoptotic Pathways

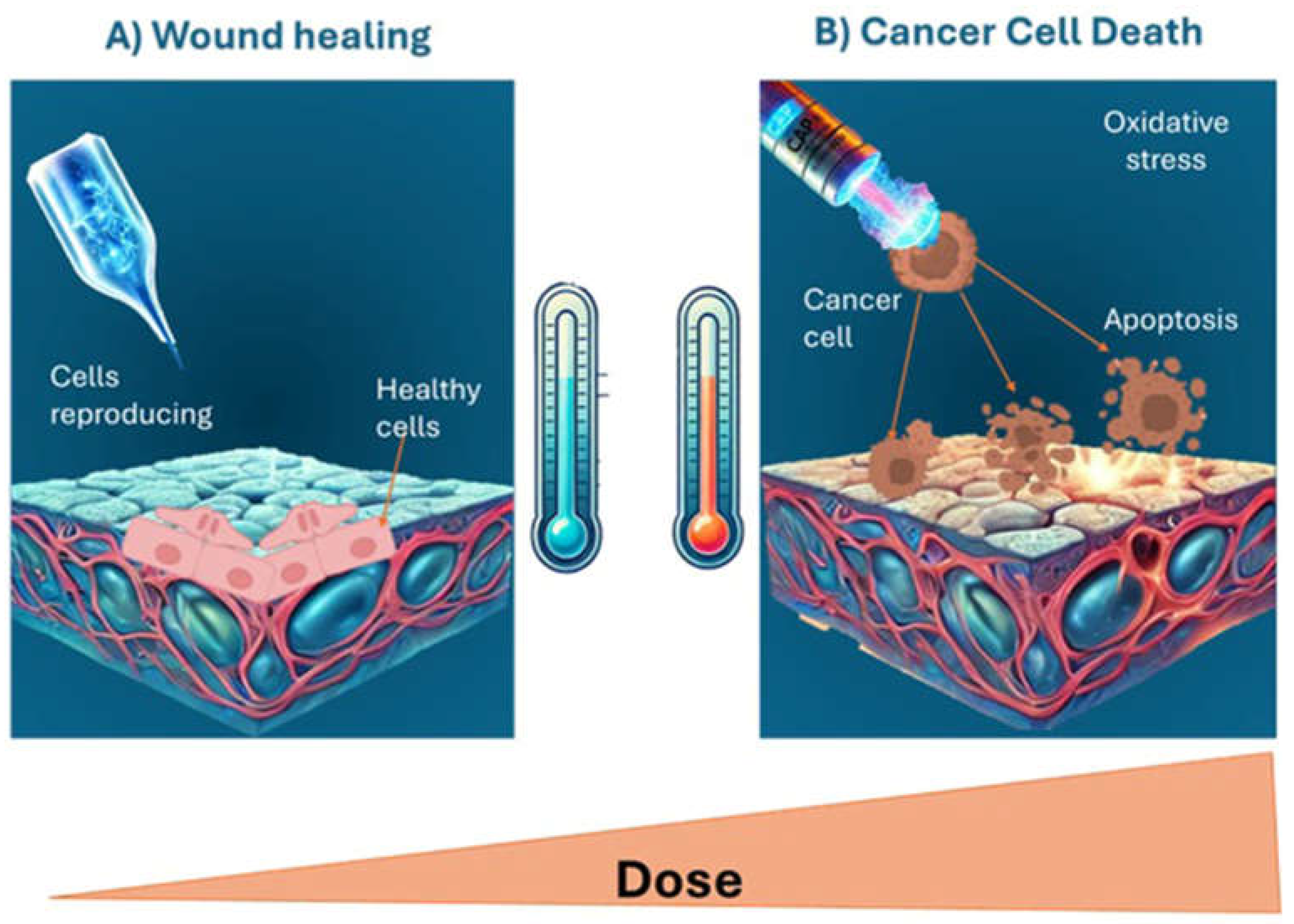

4. Dual Applications of CAP: From Tissue Regeneration to Apoptosis Induction in Cancer Cells

5. Preclinical Evidence of CAP in Cancer Treatment

5.1. In Vitro Studies on the Anti-Cancer Effects of CAP

5.2. In Vivo Studies on the Anti-Cancer Effects of CAP

6. Future Perspectives of CAP Use in Oncology

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou Z, Li M. Targeted therapies for cancer. BMC Med. 2022;20:90. [CrossRef]

- Santhosh S, Kumar P, Ramprasad V, Chaudhuri A. Evolution of targeted therapies in cancer: opportunities and challenges in the clinic. Future Oncol. 2015;11(2):279-293. [CrossRef]

- Ward RA, Fawell S, Floc’h N, Flemington V, McKerrecher D, Smith PD. Challenges and Opportunities in Cancer Drug Resistance. Chem Rev. 2021;121:3297-3351. [CrossRef]

- Murillo D, Huergo C, Gallego B, Rodríguez R, Tornín J. Exploring the Use of Cold Atmospheric Plasma to Overcome Drug Resistance in Cancer. Biomedicines. 2023;11:208. [CrossRef]

- Dubuc A, Monsarrat P, Virard F, et al. Use of Cold-Atmospheric Plasma in Oncology: A Concise Systematic Review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918786475. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Zhou H, Tan L, et al. Exploring treatment options in cancer: tumor treatment strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:175. [CrossRef]

- Metelmann HR, Seebauer C, Miller V, et al. Clinical experience with cold plasma in the treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Clin Plasma Med. 2018;9:6-13. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Xu D, Liu D, et al. Production of simplex RNS and ROS by nanosecond pulse N2/O2 plasma jets with homogeneous shielding gas for inducing myeloma cell apoptosis. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2017;50(19):195204. [CrossRef]

- Gusti-Ngurah-Putu EP, Huang L, Hsu YC. Effective combined photodynamic therapy with lipid platinum chloride nanoparticles therapies of oral squamous carcinoma tumor inhibition. J Clin Med. 2019;8(12):2112. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary K, Imam AM, Rizvi SZH, Ali J. Kinetic Theory. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech; 2018:107-127. [CrossRef]

- von Woedtke T, Laroussi M, Gherardi M. Foundations of plasmas for medical applications. Plasma Sources Sci Technol. 2022;31:39. [CrossRef]

- Tabares FL, Junkar I. Cold Plasma Systems and their Application in Surface Treatments for Medicine. Molecules. 2021;26(7):1903. [CrossRef]

- Braný D, Dvorská D, Halašová E, Škovierová H. Cold Atmospheric Plasma: A Powerful Tool for Modern Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(8):2932. [CrossRef]

- Von Woedtke T, Schmidt A, Bekeschus S, Wende K, Weltmann KD. Plasma Medicine: A Field of Applied Redox Biology. In Vivo. 2019;33:1011-1026. [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu T, Uehara K, Sasaki Y, et al. Investigation of Reactive Species Using Various Gas Plasmas. RSC Adv. 2014;4:39901-39905. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi A, Nicol MJ, Bilén SG, Kirimanjeswara GS, Knecht SD. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Medicine: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities for Predictive Control. Plasma. 2024;7:233-257. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Chen G, Obenchain R, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma delivery for biomedical applications. Materials Today. 2022;54:153-188. [CrossRef]

- Puligundla P, Mok C. Microwave- and radio-frequency-powered cold plasma applications for food safety and preservation. Bermudez-Aguirre D, editor. Advances in Cold Plasma Applications for Food Safety and Preservation. Academic Press; 2020:309-329. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Chen Z, Liu Z, et al. The bactericidal effects of plasma-activated saline prepared by the combination of surface discharge plasma and plasma jet. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2021;54(38):385202. [CrossRef]

- Sajib SA, Billah M, Mahmud S, et al. Plasma activated water: The next generation eco-friendly stimulant for enhancing plant seed germination, vigor and increased enzyme activity, a study on black gram (Vigna mungo L.). Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2020;40(1):119-143. [CrossRef]

- Shen J, Tian Y, Li Y, et al. Bactericidal effects against S. aureus and physicochemical properties of plasma activated water stored at different temperatures. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28505. [CrossRef]

- Zhao YM, Patange A, Sun DW, Tiwari B. Plasma-activated water: Physicochemical properties, microbial inactivation mechanisms, factors influencing antimicrobial effectiveness, and applications in the food industry. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19(6):3951-3979. [CrossRef]

- Khlyustova A, Labay C, Machala Z, Ginebra MP, Canal C. Important parameters in plasma jets for the production of RONS in liquids for plasma medicine: A brief review. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2019;13(2):238–252. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Chen R, Tian E, et al. Plasma-activated water treatment of fresh beef: Bacterial inactivation and effects on quality attributes. IEEE Trans Radiat Plasma Med Sci.2020; 254:201–207. [CrossRef]

- Laroussi M. Cold Plasma in Medicine and Healthcare: The New Frontier in Low Temperature Plasma Applications. Front Phys. 2020;8. [CrossRef]

- Heinlin J, et al. Plasma Applications in Medicine with a Special Focus on Dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2011;25(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Dijksteel GS, Ulrich MMW, Vlig M, Sobota A, Middelkoop E, Boekema BKHL. Safety and bactericidal efficacy of cold atmospheric plasma generated by a flexible surface Dielectric Barrier Discharge device against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in vivo. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19(1):37. [CrossRef]

- Sainz-García E, Alba-Elías F. Advances in the Application of Cold Plasma Technology in Foods. Foods. 2023;12(7):1388. [CrossRef]

- Scholtz V, et al. Nonthermal Plasma - A Tool for Decontamination and Disinfection. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33(6):1108-1119. [CrossRef]

- Domonkos M, Tichá P, Trejbal J, Demo P. Applications of Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Technology in Medicine, Agriculture and Food Industry. Appl Sci. 2021;11(11):4809. [CrossRef]

- Gururani, P., Bhatnagar, P., Bisht, B., et al. 2021. Cold plasma technology: advanced and sustainable approach for wastewater treatment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28, 65062–65082. [CrossRef]

- Zhou R, Zhou R, Wang P, Xian Y, Mai-Prochnow A, Lu X, Cullen PJ, Ostrikov K, Bazaka K. Plasma-activated water: Generation, origin of reactive species and biological applications. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2020;53:303001. [CrossRef]

- Khlyustova A, Labay C, Machala Z, Ginebra M-P, Canal C. Important parameters in plasma jets for the production of RONS in liquids for plasma medicine: A brief review. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2019;13:238-252. [CrossRef]

- Abdo AI, Kopecki Z. Comparing redox and intracellular signalling responses to cold plasma in wound healing and cancer. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46(5):4885-4923. [CrossRef]

- Su LJ, Zhang JH, Gomez H, et al. Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Lipid Peroxidation in Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:5080843. [CrossRef]

- Dharini M, Jaspin S, Mahendran R. Cold plasma reactive species: Generation, properties, and interaction with food biomolecules. Food Chem. 2023;405(Part A):134746. [CrossRef]

- Maheux S, Frache G, Thomann JS, Clément F, Penny C, Belmonte T, Duday D. Small unilamellar liposomes as a membrane model for cell inactivation by cold atmospheric plasma treatment. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2016;49:344001. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki S, Honda R, Hokari Y, Takashima K, Kanzaki M, Kaneko T. Characterization of plasma-induced cell membrane permeabilization: Focus on OH radical distribution. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2016;49:334002. [CrossRef]

- Van der Paal J, Neyts EC, Verlackt CCW, Bogaerts A. Effect of lipid peroxidation on membrane permeability of cancer and normal cells subjected to oxidative stress. Chem Sci. 2016;7:489-498. [CrossRef]

- Yusupov M, Yan D, Cordeiro RM, Bogaerts A. Atomic scale simulation of H2O2 permeation through aquaporin: Toward the understanding of plasma cancer treatment. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2018;51:125401. [CrossRef]

- Bienert GP, Chaumont F. Aquaporin-facilitated transmembrane diffusion of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:1596-1604. [CrossRef]

- Reis A, Spickett CM. Chemistry of phospholipid oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:2374–2387. [CrossRef]

- Van der Paal J, Verheyen C, Neyts EC, Bogaerts A. Hampering effect of cholesterol on the permeation of reactive oxygen species through phospholipid bilayer: Possible explanation for plasma cancer selectivity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39526. [CrossRef]

- Oberley LW, Buettner GR. Role of superoxide dismutase in cancer: A review. Cancer Res. 1979;39:1141–1149.

- Zhu SJ, Wang KJ, Gan SW, Xu J, Xu SY, Sun SQ. Expression of aquaporin 8 in human astrocytomas: Correlation with pathologic grade. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;440(1):168-172. [CrossRef]

- Glorieux C, Dejeans N, Sid B, Beck R, Calderon PB, Verrax J. Catalase overexpression in mammary cancer cells leads to a less aggressive phenotype and an altered response to chemotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82(10):1384-1390.. [CrossRef]

- Semmler ML, Bekeschus S, Schäfer M, Bernhardt T, Fischer T, Witzke K, Seebauer C, Rebl H, Grambow E, Vollmar B, et al. Molecular mechanisms of the efficacy of cold atmospheric pressure plasma (CAP) in cancer treatment. Cancers. 2020;12:269. [CrossRef]

- Lignitto L, LeBoeuf SE, Homer H, Jiang S, Askenazi M, Karakousi TR, Pass HI, Bhutkar AJ, Tsirigos A, Ueberheide B, et al. Nrf2 activation promotes lung cancer metastasis by inhibiting the degradation of Bach1. Cell. 2019;178:316–329.e318. [CrossRef]

- Li MH, Cha YN, Surh YJ. Peroxynitrite induces HO-1 expression via PI3K/Akt-dependent activation of NF-E2-related factor 2 in PC12 cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:1079–1091. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Yu KN, Bao L, Shen J, Cheng C, Han W. Non-thermal plasma inhibits human cervical cancer HeLa cells invasiveness by suppressing the MAPK pathway and decreasing matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19720. [CrossRef]

- Shi L, Yu L, Zou F, Hu H, Liu K, Lin Z. Gene expression profiling and functional analysis reveals that p53 pathway-related gene expression is highly activated in cancer cells treated by cold atmospheric plasma-activated medium. PeerJ. 2017; 25:5:e3751. [CrossRef]

- Cheng X, Sherman J, Murphy W, Ratovitski E, Canady J, Keidar M. The effect of tuning cold plasma composition on glioblastoma cell viability. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e98652. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Jiang T, Wang H, Tao S, Lau A, Fang D, Zhang DD. Does Nrf2 contribute to p53-mediated control of cell survival and death? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:1670–1675. [CrossRef]

- Dubey SK, Parab S, Alexander A, Agrawal M, Achalla VPK, Pal UN, Pandey MM, Kesharwani P. Cold atmospheric plasma therapy in wound healing. Process Biochem. 2022;112:112–123. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Xu D, Liu D, Cui Q, Cai H, Li Q, Chen H, Kong MG. Production of simplex RNS and ROS by nanosecond pulse N2/O2 plasma jets with homogeneous shielding gas for inducing myeloma cell apoptosis. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2017;50:195204. [CrossRef]

- Privat-Maldonado A, Schmidt A, Lin A, Weltmann KD, Wende K, Bogaerts A, Bekeschus S. ROS from physical plasmas: Redox chemistry for biomedical therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:9062098. [CrossRef]

- KogaIto CY et al. Cold atmospheric plasma as a therapeutic tool in medicine and dentistry. Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2023;44:1393-1429. [CrossRef]

- Li J et al. A novel method for estimating the dosage of cold atmospheric plasmas in plasma medical applications. Appl Sci. 2021;11(23):11135. [CrossRef]

- Ermakov AM, Ermakova ON, Afanasyeva VA, Popov AL. Dose-Dependent Effects of Cold Atmospheric Argon Plasma on the Mesenchymal Stem and Osteosarcoma Cells In Vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(13):6797. Published 2021 Jun 24. [CrossRef]

- Koritzer J, Boxhammer V, Schafer A, Shimizu T, Klampfl TG, Li YF, Welz C, Schwenk-Zieger S, Morfill GE, Zimmermann JL, Schlegel J. Restoration of sensitivity in chemo-resistant glioma cells by cold atmospheric plasma. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64498. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka H, Mizuno M, Ishikawa K, Nakamura K, Kajiyama H, Kano H, Kikkawa F, Hori M. Plasma-activated medium selectively kills glioblastoma brain tumor cells by down-regulating a survival signaling molecule AKT kinase. Plasma Med. 2011;1(265-277). [CrossRef]

- Conway GE, He Z, Hutanu AL, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma induces accumulation of lysosomes and caspase-independent cell death in U373MG glioblastoma multiforme cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):12891. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Mang X, Li X, Cai Z, Tan F. Cold atmospheric plasma induces apoptosis in human colon and lung cancer cells through modulating mitochondrial pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:915785. [CrossRef]

- Muttiah B, Mohd Nasir N, Mariappan V, Vadivelu J, Vellasamy KM, Yap SL. Targeting colon cancer and normal cells with cold plasma-activated water: Exploring cytotoxic effects and cellular responses. Phys Plasmas. 2024;31(8):083516. [CrossRef]

- Ruwan Kumara MH, Piao MJ, Kang KA, et al. Non-thermal gas plasma-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress mediates apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2016;36(4):2268-2274. [CrossRef]

- Aggelopoulos CA, Christodoulou AM, Tachliabouri M, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma attenuates breast cancer cell growth through regulation of cell microenvironment effectors. Front Oncol. 2022;11:826865. [CrossRef]

- Adil BH, Al-Shammari AM, Murbat HH. Breast cancer treatment using cold atmospheric plasma generated by the FE-DBD scheme. Clin Plasma Med. 2020;19-20:100103. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Lee H, Jeong D, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma restores tamoxifen sensitivity in resistant MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;110:280-290. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Zhou R, Zhou R, et al. Epidermal growth factor potentiates EGFR(Y992/1173)-mediated therapeutic response of triple negative breast cancer cells to cold atmospheric plasma-activated medium. Redox Biol. 2024;69:102976. [CrossRef]

- Misra VC, Pai BG, Tiwari N, et al. Excitation frequency effect on breast cancer cell death by atmospheric pressure cold plasma. Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2023;43:467-490. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Mang X, Li X, Cai Z, Tan F. Cold atmospheric plasma induces apoptosis in human colon and lung cancer cells through modulating mitochondrial pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:915785;. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Liu H, Li X, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma enhances SLC7A11-mediated ferroptosis in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating PCAF mediated HOXB9 acetylation. Redox Biol. 2024;75:103299. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Chen G, Yu KN, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma induces GSDME-dependent pyroptotic signaling pathway via ROS generation in tumor cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:295. [CrossRef]

- Verloy R, Privat-Maldonado A, Smits E, Bogaerts A. Cold atmospheric plasma treatment for pancreatic cancer—the importance of pancreatic stellate cells. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(10):2782. [CrossRef]

- Liedtke KR, Bekeschus S, Kaeding A, et al. Non-thermal plasma-treated solution demonstrates antitumor activity against pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8319. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann T, Staebler S, Taudte RV, et al. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Triggers Apoptosis via the Unfolded Protein Response in Melanoma Cells. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(4):1064. [CrossRef]

- Soni V, Adhikari M, Simonyan H, et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Enhancement of Temozolomide Effect in Human Glioblastoma by Non-Invasive Application of Cold Atmospheric Plasma. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(17):4485. [CrossRef]

- Lin AG, Xiang B, Merlino DJ, et al. Non-thermal plasma induces immunogenic cell death in vivo in murine CT26 colorectal tumors. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(9):e1484978. [CrossRef]

- Jung J-M, Yoon H-K, Kim S-Y, et al. Anticancer Effect of Cold Atmospheric Plasma in Syngeneic Mouse Models of Melanoma and Colon Cancer. Molecules. 2023;28(10):4171. [CrossRef]

- Guo B, Pomicter AD, Li F, et al. Trident cold atmospheric plasma blocks three cancer survival pathways to overcome therapy resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(51):e2107220118. [CrossRef]

- Qi M, Zhao X, Fan R, et al. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Suppressed MM In Vivo Engraftment by Increasing ROS and Inhibiting the Notch Signaling Pathway. Molecules. 2022;27(18):5832. [CrossRef]

- Sato Y, Yamada S, Takeda S, et al. Effect of Plasma-Activated Lactated Ringer's Solution on Pancreatic Cancer Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(1):299-307. [CrossRef]

- Vaquero J, Judée F, Vallette M, et al. Cold-Atmospheric Plasma Induces Tumor Cell Death in Preclinical In Vivo and In Vitro Models of Human Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(5):1280. [CrossRef]

- Kang SU, Cho JH, Chang JW, et al. Nonthermal plasma induces head and neck cancer cell death: The potential involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(2):e1056. [CrossRef]

- Metelmann HR, Nedrelow DS, Seebauer C, et al. Head and neck cancer treatment and physical plasma. Clin Plasma Med. 2015;3:17-23. [CrossRef]

- Schuster M, Seebauer C, Rutkowski R, et al. Visible tumor surface response to physical plasma and apoptotic cell kill in head and neck cancer. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2016;44:1445-1452. [CrossRef]

- Canady J, Murthy SRK, Zhuang T, et al. The First Cold Atmospheric Plasma Phase I Clinical Trial for the Treatment of Advanced Solid Tumors: A Novel Treatment Arm for Cancer. Cancers. 2023;15(14):3688. [CrossRef]

- Metelmann HR, Seebauer C, Miller V, et al. Clinical experience with cold plasma in the treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Clin Plasma Med. 2018;9:6-13. [CrossRef]

- Marzi J, Stope MB, Henes M, et al. Noninvasive Physical Plasma as Innovative and Tissue-Preserving Therapy for Women Positive for Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Cancers. 2022;14:1933. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Yu KN, Ma J, et al. Non-thermal plasma induces mitochondria-mediated apoptotic signaling pathway via ROS generation in HeLa cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;633:68-77. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Zhou Y, Song W, et al. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Inhibits the Proliferation of CAL-62 Cells through the ROS-Mediated PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Sci Technol Nucl Install. 2022;3884695. [CrossRef]

- MA J.; Yu K.N.; Zhang H.; Nie L.; Cheng C.; Cui S.; Yang M.; Chen G.; Han W. Non-thermal plasma induces apoptosis accompanied by protective autophagy via activating JNK/Sestrin2 pathway.J Phys D Appl Phys.2020;53:465201. [CrossRef]

- Niu B., Liao K., Zhou Y., Wen T., Quan G., Pan X., et al. Application of glutathione depletion in cancer therapy: enhanced ROS-based therapy, ferroptosis, and chemotherapy. Biomaterials.2021;277:121110. [CrossRef]

| Type of Reactive Species | Name | Generation Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| ROS [33,34]. | Atomic Oxygen (O) | Generated by collisions between oxygen molecules and electrons in the plasma. |

| Hydroxyl Radicals (OH•) | Originates from the dissociation of water molecules, enhanced by UV radiation. | |

| Superoxide O2•− | Produced by collisions between electrons and oxygen molecules, and reactions between OH and ozone. | |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) | Results from the combination of OH radicals in the plasma. | |

| Ozone (O3) | Formed from collisions between atomic oxygen (O) and oxygen molecules (O2) in the plasma. | |

| RNS [33,34]. | Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) | Includes nitrite (NO2− ) and nitrate (NO3−), generated by reactions between dissociated nitrogen and oxygen. |

| Nitric Oxide (NO) | Formed by dissolution from the gas phase or through secondary reactions in the plasma. |

| Pathway | Normal Cells | Cancer Cells | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nrf2 | - Activation of the Nrf2 pathway, a master regulator of the antioxidant response. - Promotes cell survival and enhances the ability to manage oxidative stress. |

- Suppression of the Nrf2 pathway, compromising antioxidant capacity. - Increases sensitivity to oxidative stress, predisposing to DNA damage and apoptosis. |

[49]. |

| PI3K/Akt | - Transient activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway, favoring cell survival and proliferation. - CAP does not significantly impact normal cell survival signaling. |

- Inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway by cold plasma reduces AKT phosphorylation, promoting apoptosis and decreasing proliferation. - Synergistic effects with chemotherapy enhance drug-induced apoptosis. |

[50]. |

| MAPK | - Less pronounced or transient activation of MAPK pathways, minimizing detrimental effects. | - Activation of stress-related kinases (e.g., JNK and p38) while inhibiting ERK1/2, leading to increased apoptosis and reduced proliferation. - CAP-induced activation of JNK promotes apoptotic cell death in cancer cells. |

[51]. |

| p53 Activation | - Typically unaltered in normal cells, maintaining regulatory functions of cell cycle and apoptosis. | - CAP treatment can restore p53 function, increasing expression and activation of apoptotic pathways. - Enhanced p53 activation leads to DNA damage response, promoting cell death. |

[52]. |

| Studie Type | Cancer Type | Study Description | Mechanism (ROS, Apoptosis, Others) | Specific Signaling Pathway | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro | Glioblastoma | CAP increased the cytotoxicity of temozolomide in glioblastoma cells, suggesting chemosensitization. | ROS, Apoptosis, Direct DNA damage | p53, PI3K/Akt | [61,62,63] |

| Colon cancer | Induction of cell death by oxidative stress via CAP; potential use as an adjuvant therapy. | ROS, Apoptosis, Stress on the endoplasmic reticulum |

Caspasa-9, caspasa-3, PARP y Bax/ Bcl-2 | [63,64] |

|

| Breast cancer | Antiproliferative and apoptosis-inducing effect; potential for chemotherapy sensitization. Sensitization by epidermal growth factor (EGF) enhances the response of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells to CAP cold |

Apoptosis, Signaling pathway alteration This activation increases the production of reactive ROS and apoptotic signaling, |

Increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and cleavage of PARP-1. EGFR(Y992/1173) |

[67,68,69] [70] |

|

| Lung cancer | Reduction of viable cells and anti-metastatic activity observed. Inhibition proliferation, reduced migration Cell death in tumor cells PC9 expressing high levels of Gasdermin E (GSDME) in a dose-dependent manner |

ROS, Apoptosis, Microenvironment modulation ROS, Ferroptosis, ROS, Pyroptosis |

p38 MAPK, PI3/Akt Downregulation of the HOXB9/SLC7A11K JNK/cytochrome c/caspase-9/caspase-3 |

[71] [72] [73] |

|

| Pancreatic cancer | Reduction of metabolic activity and cell migration; favorable modulation of inflammatory profile. | ROS, Inflammatory regulation | NF-κB, IL-6 | [74,75] |

|

| Melanoma | CAP combined with nanoparticles enhanced selective toxicity towards cancer cells without damaging normal cells. | ROS, Microenvironment modulation | UPR signalling, Notch, Wnt/β-catenin | [76] |

|

| Study Type | Cancer Type | Description | Mechanism of Action and Signaling Pathways | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo studies | Glioblastoma | CAP increased ROS production, sensitizing tumor cells to chemotherapy with temozolomide. | ROS, Apoptosis, p53, PI3K/Akt pathways; Significant reduction in tumor growth. | [77] |

| Colon cancer | CAP promoted danger signal release and stimulated adaptive immune response in mouse models. | ROS, Immune activation; Specific T cell response against GUCY2C. | [78,79] |

|

| Myeloid leukemia | CAP blocked three key cancer survival pathways: redox deregulation, glycolysis, and AKT/mTOR/HIF-1α signaling. | ROS, Apoptosis, AKT/mTOR, HIF-1α pathways; Reduced tumor growth and improved survival. | [80] |

|

| Multiple myeloma | CAP inhibited tumor implantation in mice, significantly prolonging survival time. | ROS, Apoptosis, Notch pathway inhibition; Reduced tumor cell proliferation. | [81] |

|

| Pancreatic cancer | A plasma-activated lactated Ringer's solution was developed to evaluate its antitumor effects. | ROS, Cytotoxic effects derived from activated lactic acid; Tumor volume reduction. | [82] |

|

| Cholangiocarcinoma | CAP induced DNA damage and apoptosis in subcutaneous xenografts of cancer cells. | ROS, DNA damage, Apoptosis; Activation of CHK1, p53, and 8-oxoguanine accumulation. | [83] |

|

| Head and neck cancer | CAP induced apoptosis and reduced cell viability in head and neck cancer models. | ROS, Apoptosis; Mitochondrial membrane potential modification and MAPK pathway activation. | [84] |

| CAP APPLICATION DEVICE | Study Description | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| kINPen | The study demonstrated that CAP treatment delivered using the kINPen MED device is safe, well tolerated, and effective in reducing tumor size in patients with head and neck cancer. CAP induced selective tumor cell death through oxidative stress without damaging surrounding healthy tissues. | Tumor size reduction in head and neck cancer. | [85] |

| Plasma jet, kINPen(®) MED (neoplas tools GmbH, Greifswald, Germany). | This study concluded that the use of a cold plasma device, specifically a dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) system, in patients with head and neck cancer showed visible responses on the tumor surface and significant apoptotic cell death. The treatment was well tolerated, with a favorable safety profile and no significant adverse effects. | Induction of apoptotic death in head and neck cancer. | [86] |

| Canady Helios Cold Plasma (CHCP) | The CHCP device was investigated in the first phase I clinical study, primarily to demonstrate safety. Preliminary findings were encouraging, showing that CHCP can control residual disease and improve patient survival. Ex vivo experiments on patient tissue samples confirmed CHCP-induced cancer cell death without harming normal cells, indicating its potential to control residual cancer cells at surgical margins. | Control of residual tumor cells in surgical margins in combination with surgery. | [87] |

| kINPen | This study concluded that CAP use in advanced head and neck cancer patients is safe and may induce positive clinical responses, such as pain reduction and improved quality of life. Two patients achieved partial remission, suggesting CAP's potential as an effective therapeutic option; however, further research is needed to fully understand its long-term mechanisms and efficacy. | Improving quality of life and reducing pain in patients with advanced head and neck cancer. | [88] |

| VIO3/APC3 (Erbe Elektromedizin) | This study concluded that noninvasive physical plasma (NIPP) is a safe and effective method for treating cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grades 1 and 2. Using the cold plasma device, VIO3/APC3, with precise application control, the treatment preserved tissue while inducing lesion regression, making it a promising alternative to current excisional and ablative treatments. | Conservative treatment of CIN in women. | [89] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).